Submitted:

04 May 2023

Posted:

05 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

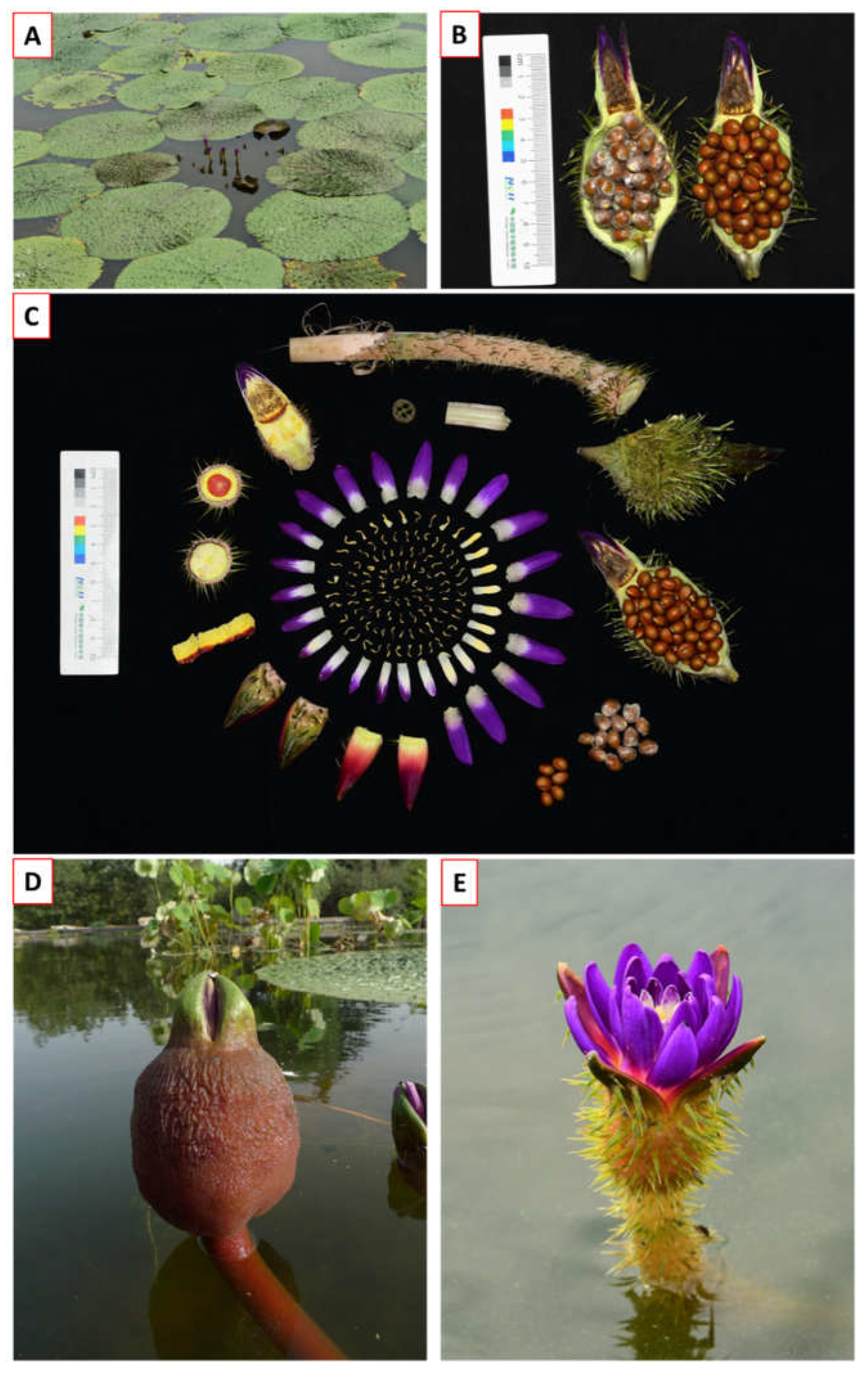

3. Botanical Studies of E. ferox

4. Traditional Medicinal Uses of E. ferox

5. Phytochemistry

5.1. Polysaccharides

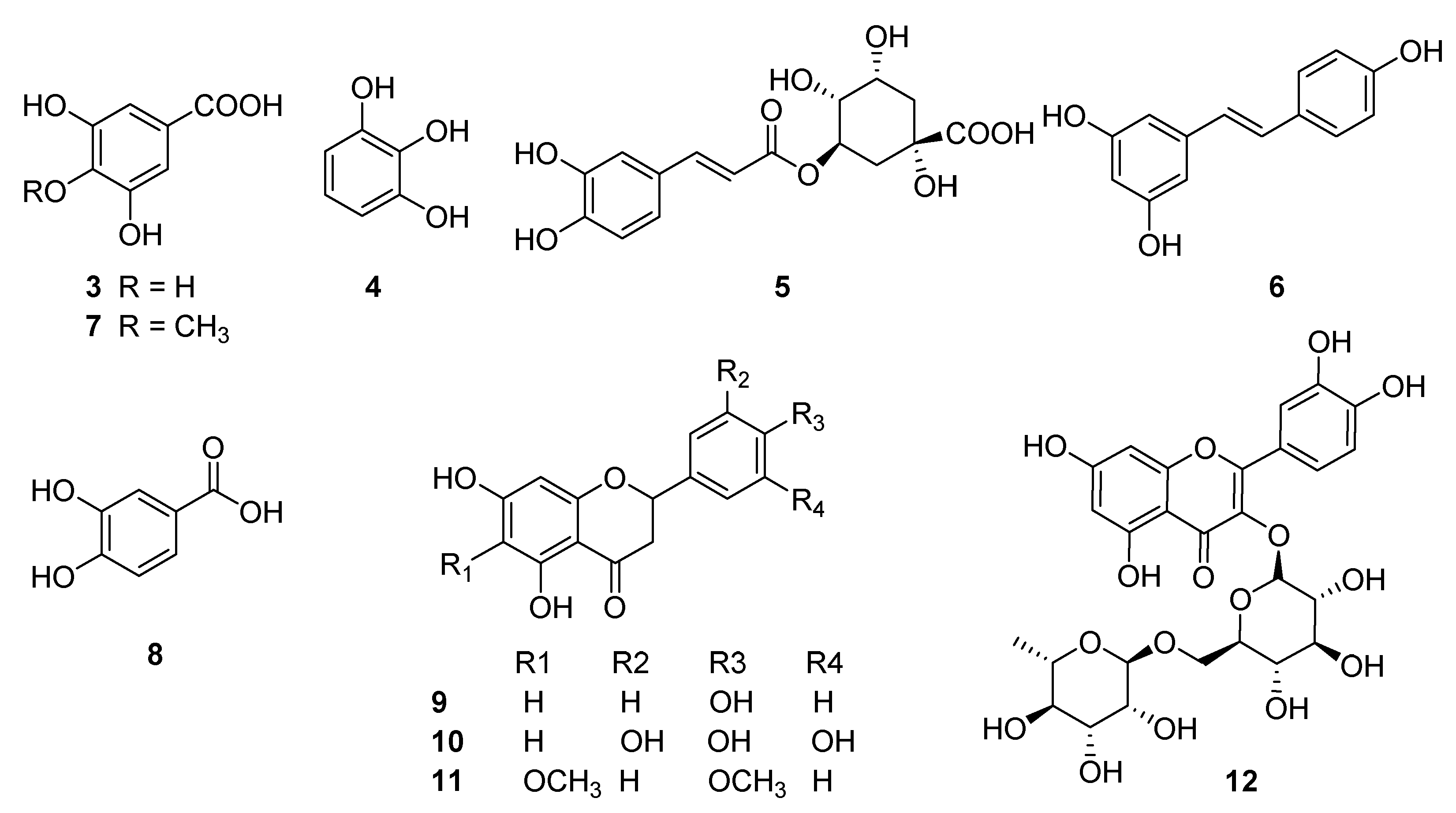

5.2. Polyphenols and Flavonoids

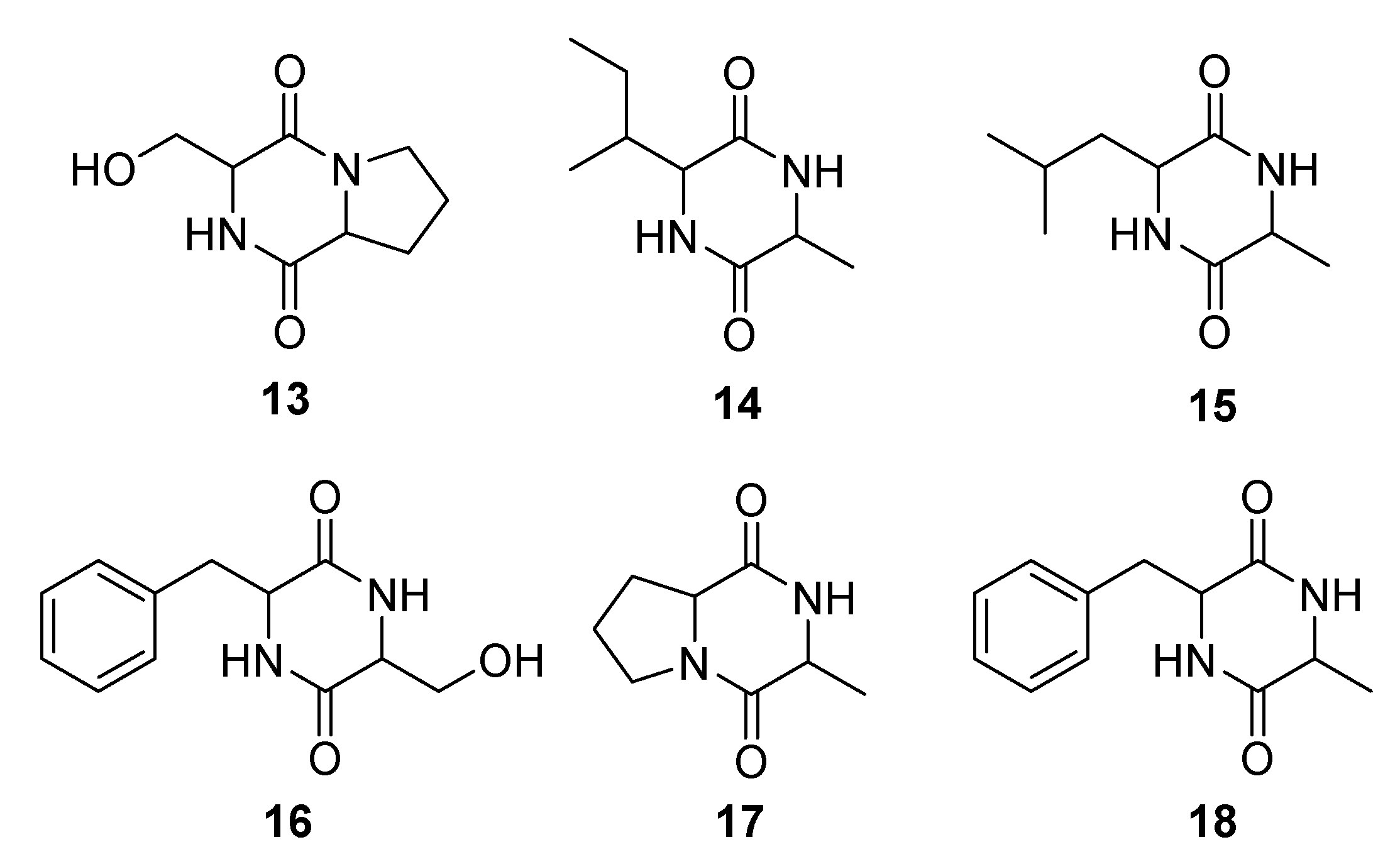

5.3. Cyclic Peptides

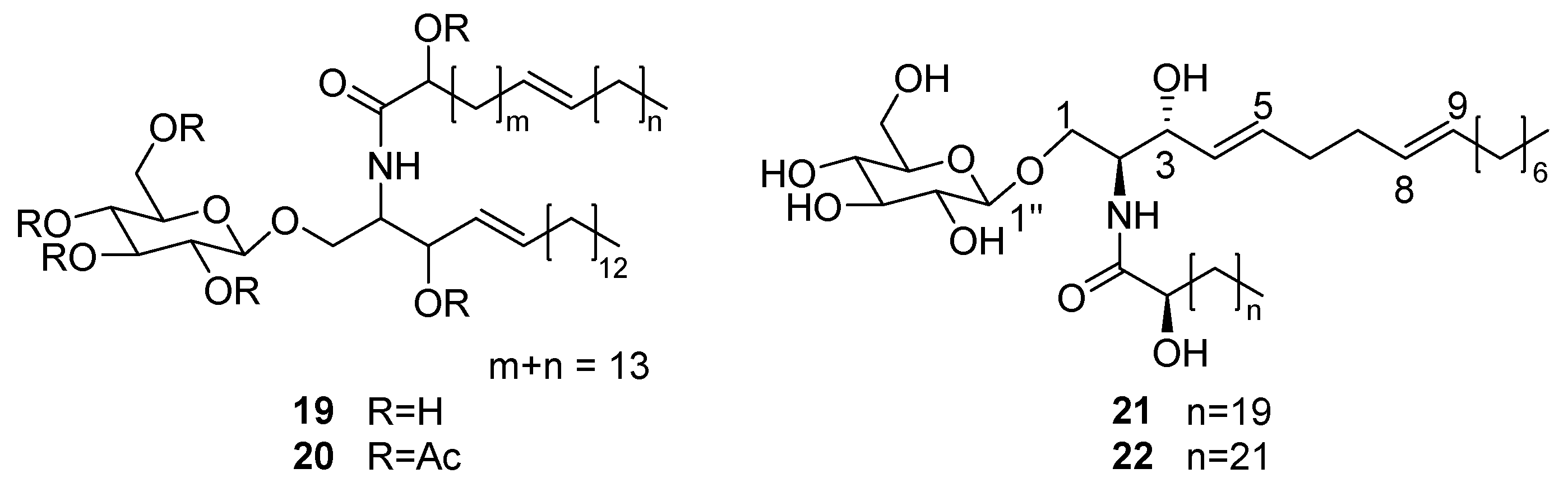

5.4. Cerebrosides

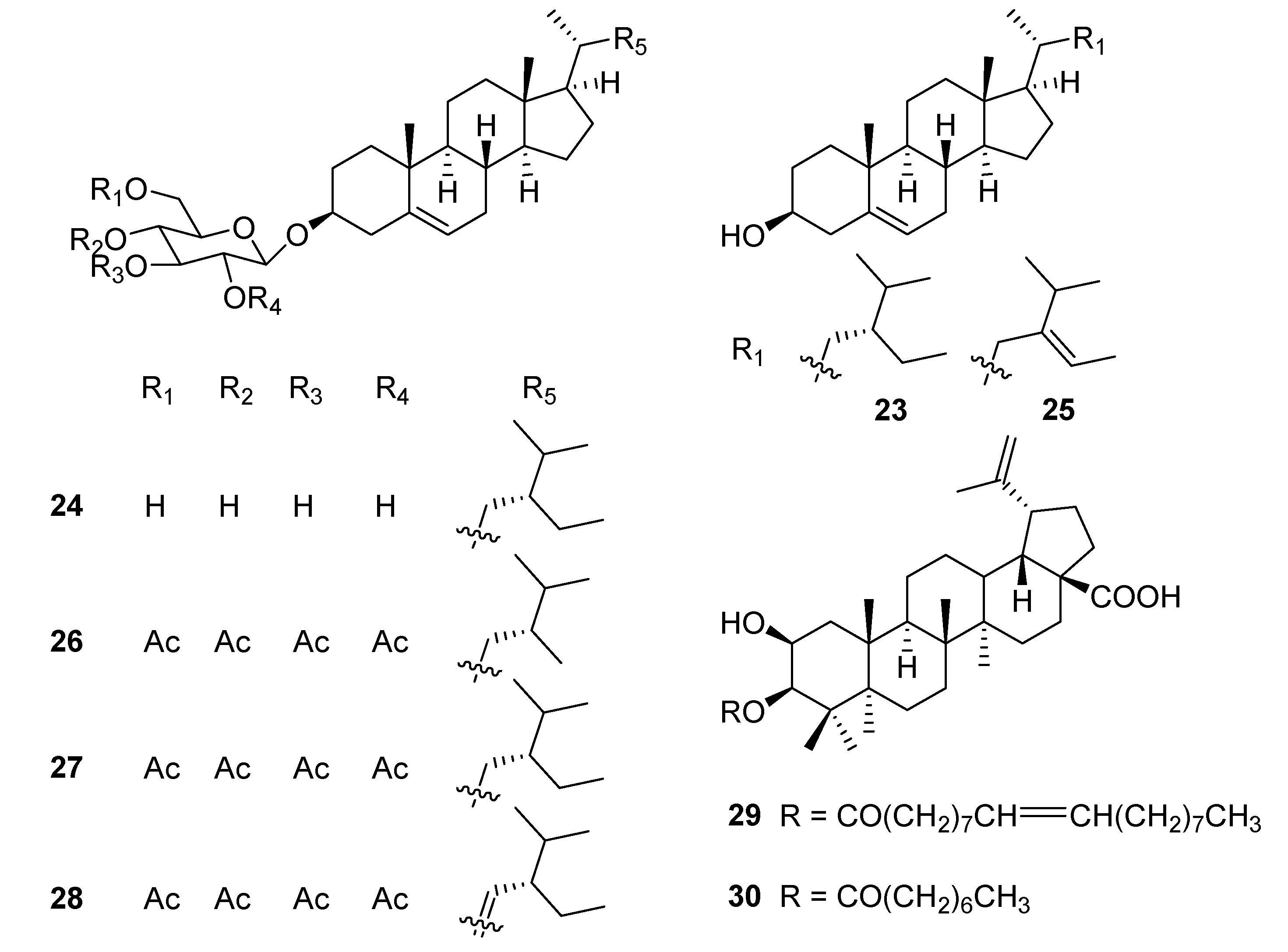

5.5. Steroids and Pentacyclic Triterpenes

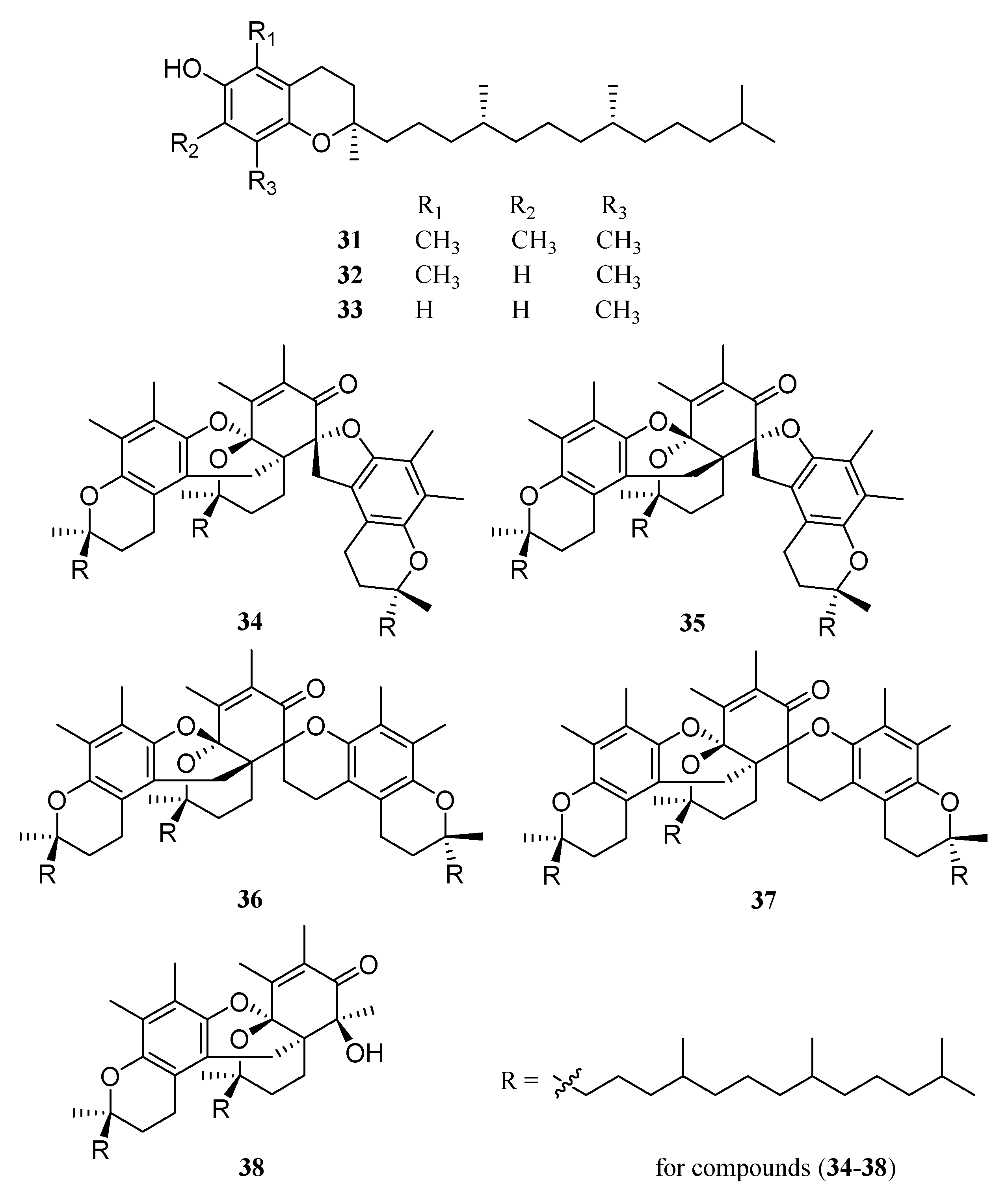

5.6. Tocopherol

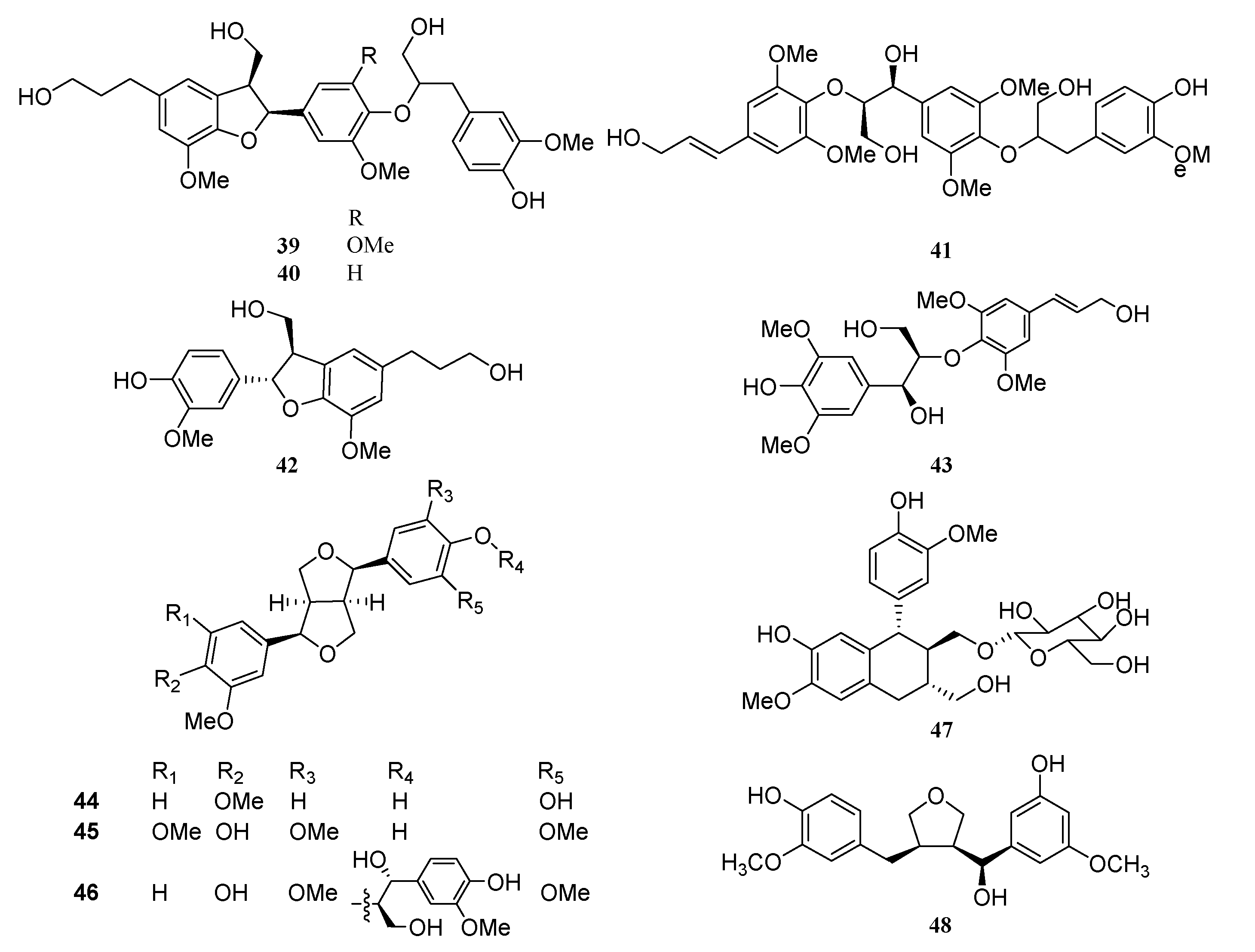

5.7. Lignans

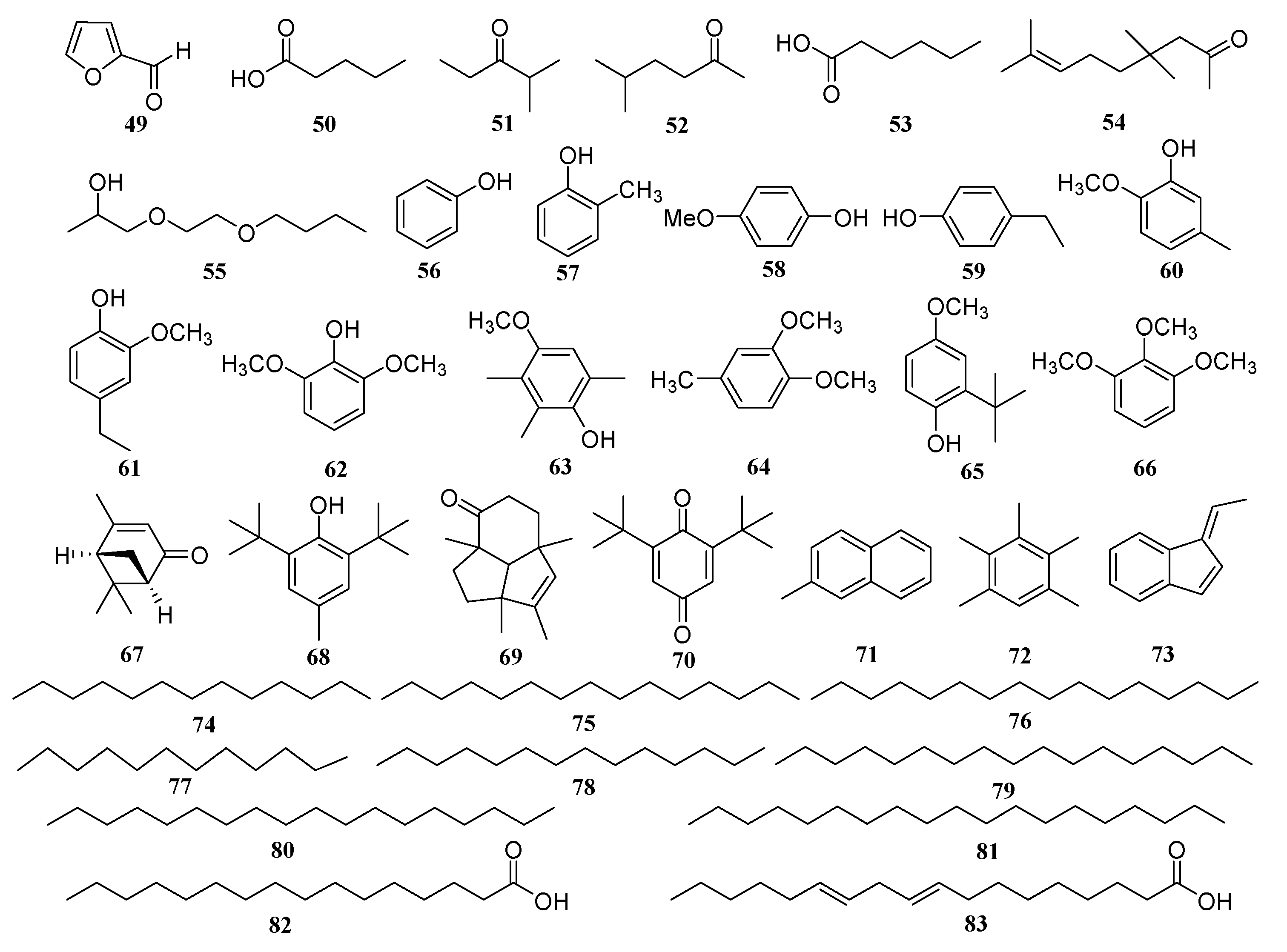

5.8. Essential Oil

5.9. Others

6. Pharmacological Activities

6.1. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activity

6.2. Antidiabetic and Hypoglycemic Activity

6.3. Hepatoprotective and Cardioprotective Activity

6.4. Cytotoxic and Anticancer Activity

6.5. Antifatigue Activity

6.6. Anti-Depressant Activity

7. Toxicity

8. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, M.H.; Liang, Z.T.; Ge, L.; Lan, W. Study on history of development and laws of herbalproperty about homology of medicine and food. Chin. J. Ethnomed. Ethnopharm. 2022, 31, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Xiao, W.; Qin, Z.X.; Xiao, P.G. Annotation of drug and food are the same origin and its realistic significance. Modern Chinese Medicine 2015, 17, 1250–1252+1279. [Google Scholar]

- Semwal, D.P.; Pandey, A.; Gore, P.G.; Ahlawat, S.P.; Yadav, S.K.; Kumar, A. Habitat prediction mapping using BioClim model for prioritizing germplasm collection and conservation of an aquatic cash crop ‘Makhana’ (Euryale ferox Salisb.) in India. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2021, 68, 3445–3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imanishi, A.; Imanishi, J. Seed dormancy and germination traits of an endangered aquatic plant species, Euryale ferox Salisb. (Nymphaeaceae). Aquat. Bot. 2014, 119, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. Euryale ferox 芡实 (Qianshi, Gordon Euryale Seed). In: Liu, Y., Wang, Z., Zhang, J. (eds) Dietary Chinese Herbs. Springer, Vienna, 2015.

- Yamada, T.; Imaichi, R.; Kato, M. Developmental morphology of ovules and seeds of Nymphaeales. Am. J. Bot. 2001, 88, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khadatkar, A.; Mehta, C.R.; Gite, L.P. Makhana (Euryle Ferox Salisb.): A high-valued aquatic food crop with emphasis on its agronomic management – A review. Scientia Horticulturae 2020, 261, 108995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, V.; Shalini, R.; Kumari, A.; Jha, P.; Sah, N.K. Aquacultural, nutritional and therapeutic biology of delicious seeds of Euryale ferox Salisb: A Minireview. CPB 2018, 19, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China. China Medical Science, 2020.

- Kapoor, S.; Kaur, A.; Kaur, R.; Kumar, V.; Choudhary, M. Euryale ferox, a prominent superfood: nutritional, pharmaceutical, and its economical importance. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, R.; Sharma, S.; Mittal, A. A critical review on ethnobotanical and pharmacological aspects of Euryale ferox Salisb. Pharmacognosy Journal 2020, 12, 1444–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.L.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Xie, X.Y.; Che, Y.Y. Studies on chemical constituents from seeds of Euryale ferox. Journal of Chinese medicinal materials 2014, 37, 2019–2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jian, T.; Yu, C.; Ding, X.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Zuo, Y.; Ren, B.; Lv, H.; Li, W. Hepatoprotective effect of seed coat of Euryale ferox extract in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease induced by high-fat diet in mice by increasing IRs-1 and inhibiting CYP2E1. J. Oleo Sci. 2019, 68, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Der, P.; Raychaudhuri, U.; Maulik, N.; Das, D.K. The effect of Euryale ferox (Makhana), an herb of aquatic origin, on myocardial ischemic reperfusion injury. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2006, 289, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, D.; Kumar, V.; Verma, A.; Shukla, G.S.; Sharma, M. Antidiabetic, antioxidant, antihyperlipidemic effect of extract of Euryale ferox Salisb. with enhanced histopathology of pancreas, liver and kidney in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. SpringerPlus 2015, 4, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, G.-H.; Jo, K.-J.; Park, Y.-S.; Kawk, H.W.; Kim, S.-Y.; Kim, Y.-M. In vitro and in vivo induction of P53-dependent apoptosis by extract of Euryale ferox Salisb in A549 human caucasian lung carcinoma cancer cells is mediated through Akt signaling pathway. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Luo, T.; Yi, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, L. The effect and mechanism of corilagin from Euryale ferox Salisb shell on LPS-induced inflammation in Raw264.7 cells. Foods 2023, 12, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Chen, R.; Wang, X.; Shen, B.; Yue, W.; Wu, Q. Antioxidant and anti-fatigue activities of phenolic extract from the seed coat of Euryale ferox Salisb. and identification of three phenolic compounds by LC-ESI-MS/MS. Molecules 2013, 18, 11003–11021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.-S. Anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory activities of seven medicinal herbs including Tetrapanax papyriferus and Piper longum Linne. Korean J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 41, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Ju, E.M.; Kim, J.H. Antioxidant activity of extracts from Euryale ferox Seed. Exp. Mol. Med. 2002, 34, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; You, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, D.; Zhao, D.; Li, M.; Wang, C. Enhancing bioactive components of Euryale ferox with Lactobacillus curvatus to reduce H2O2-induced oxidative stress in human skin fibroblasts. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Huang, X.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, R.; Sun, G.; Xu, Y.; Wu, Q. Extract of Euryale ferox Salisb exerts antidepressant effects and regulates autophagy through the adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase-UNC-51-like kinase 1 pathway. IUBMB Life 2018, 70, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.-H.; Nam, I.-J.; Kwak, H.; Kim, K.-C.; Lee, S.-H. Cellular anti-melanogenic effects of a Euryale ferox seed extract ethyl acetate fraction via the lysosomal degradation machinery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 9217–9235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, Y.Y.; Zhan, Y.; Fan, B.D.; Wei, Q.; Xu, D.H.; Liu, T.H. Research progress in chemical components, pharmacological action and clinical application of Semen Euryales. CJTCMP 2015, 30, 477–479. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, J.; Zang, J.; Liang, Q.; Tang, D.; Wang, Z.; Yin, Z. Digestive and physicochemical properties of small granular starch from Euryale ferox seeds growing in Yugan of China. Food Biophysics 2022, 17, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-Y.; Wang, H.; Fan, X.-H.; Yue, W.; Wu, Q.-N. Waste Euryale ferox Salisb. leaves as a potential source of anthocyanins: extraction optimization, identification and antioxidant activities evaluation. Waste Biomass Valor. 2020, 11, 4327–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehal, N. , Mann, S., Gupta, R. K. Two promising under-utilized grains: A review. Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge 2015, 14, 416–422. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S.B.; Jin, T. Nutrtive and health care function and development of Euryale ferox salisb. Food Engineering 2008, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Wu, Q.N. Research on materia medica of Euryale ferox salisb. Chin. Med. J. Res. Prac. 2010, 24, 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.L.; Wang, Y.H.; Wang, T. Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, P.; Li, L. J. Comparative metabolomic profiling of secondary metabolites in different tissues of Euryale ferox and functional characterization of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase. Ind. Crop Prod. 2023, 195, 116450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Xue, M.; Chen, W.; Wu, Q.N. Evaluation of the physicochemical properties and antioxidant activities of polysaccharides from Semen Euryales. J. Chinese Pharm. Sci. 2014, 23, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.-N.; Su, R.-N.; Gong, L.-L.; Yang, W.-W.; Chen, J.; Yang, R.; Wang, Y.; Pan, W.-J.; Lu, Y.-M.; Chen, Y. Structural characterization and in vitro hypoglycemic activity of a Glucan from Euryale ferox Salisb. seeds. Carbohydrate Polymers 2019, 209, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Yu, A.; Tong, S.; Gu, Z. Study on structural characterization, physicochemical properties and digestive properties of Euryale ferox resistant starch. Food Chem. 2021, 359, 129924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, P.; Das, M.; Boral, S.; Mukherjee, G.; Chaudhury, K.; Banerjee, R. Enzyme mediated resistant starch production from Indian fox nut (Euryale ferox) and studies on digestibility and functional properties. Carbohyd. Polym. 2020, 237, 116158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Liu, A.; Li, L. Metabolomics and transcriptome analysis of the biosynthesis mechanism of flavonoids in the seeds of Euryale ferox Salisb at different developmental stages. Mol. Genet. Genomics 2021, 296, 953–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wei, S.; Liao, M. Optimization of ultrasonic extraction of phenolic compounds from Euryale ferox seed shells using response surface methodology. Ind. Crop Prod. 2013, 49, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, S.J.; Kim, Y.H.; Ryoo, I.J.; Xu, G.H.; Yoo, I.D. Application as a cosmeceutical ingredient of Euryale ferox seed extract. Journal of the Society of Cosmetic Scientists of Korea 2009, 35, 309–315. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M. H.; Yang, X.Q.; Wan, Z.J.; Yang, Y.B.; Li, P.; Ding, Z.T. Chemical constituents of the seeds of Euryale ferox. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2007, 5, 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Song, C.-W.; Wang, S.-M.; Zhou, L.-L.; Hou, F.-F.; Wang, K.-J.; Han, Q.-B.; Li, N.; Cheng, Y.-X. Isolation and identification of compounds responsible for antioxidant capacity of Euryale ferox seeds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 1199–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M. H.; Li, P.; Tai, Z.G.; Yang, Y.B.; Ding, Z.T. Three cyclic dipeptides from the seeds of Euryale ferox Salisb. Journal of Kunming University 2009, 31, 39–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Zhao, S.; Guillaume, D.; Sun, C. New cerebrosides from Euryale ferox. J. Nat. Prod. 1994, 57, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Row, L.-C.; Ho, J.-C.; Chen, C.-M. Cerebrosides and tocopherol trimers from the seeds of Euryale Ferox. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 1214–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.R.; Zhao, S.X.; Sun, C.Q.; Guillaume, D. Glucosylsterols in extracts of Euryale ferox identified by high resolution NMR and mass spectrometry. J. Lipid Res. 1989, 30, 1633–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, D.; Sharma, M.; Kumar, V.; Bajaj, H.K.; Verma, A. 2β-Hydroxybetulinic acid 3β-caprylate: An active principle from Euryale ferox Salisb. seeds with antidiabetic, antioxidant, pancreas & hepatoprotective potential in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 5427–5441. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, D.; Khan, Mohd. I.; Sharma, M.; Khan, Mohd.F. Novel pentacyclic triterpene isolated from seeds of Euryale Ferox Salisb. ameliorates diabetes in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Interdisciplinary Toxicology 2018, 11, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, S.; Li, X.; Wei, D.; Zhang, M.; Qin, J. Chemical components and biological activities of the essential oil from traditional medicinal food, Euryale ferox Salisb., seeds. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Pl. 2019, 22, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, X.; Liao, J.; Yang, J.; Hu, X. Comparison of natural and synthetic α-tocopherol in rat plasma by HPLC and Euryale ferox seed as a source of natural α-tocopherol. Asian J. Chem. 2014, 26, 5279–5282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Luo, J.; Kong, L.-Y. Two new tocopherol polymers from the seeds of Euryale ferox. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2012, 14, 743–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wu, Q.; Wu, C.; Jiang, Z. Simultaneous determination of 16 nucleosides and nucleobases in Euryale ferox Salisb. by liquid chromatography coupled with electro spray ionization tandem triple quadrupole mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI-TQ-MS/MS) in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2015, 53, 1386–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorzi, A.; Deyle, K.; Heinis, C. Cyclic peptide therapeutics: past, present and future. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2017, 38, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Feng, X.; Zhou, L.; He, C.; Li, H.; Xia, J.; Ge, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Song, C.; Chen, L.; Yang, Z. Heterophyllin B, a cyclopeptide from Pseudostellaria heterophylla, improves memory via immunomodulation and neurite regeneration in i.c.v.Aβ-induced mice. Food Res. Int. 2022, 158, 111576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Li, X.; Ma, Z.; Ge, Y.; Qian, Z.; Song, C. Heterophyllin B, a cyclopeptide from Pseudostellaria heterophylla, enhances cognitive function via neurite outgrowth and synaptic plasticity. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 5318–5329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Gong, Z.; Meng, S.; He, G. Hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effects of a triterpenoid-rich extract from Euryale shell on streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Pharmazie 2013, 68, 227–231. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C. In vitro antioxidant properties of Euryale ferox seed shell extracts and their preservation effects on pork sausages. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2015, 39, 1172–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Shen, B.; He, X.; Gu, W.; Wu, Q. Extraction optimization, isolation, preliminary structural characterization and antioxidant activities of the cell wall polysaccharides in the petioles and pedicels of Chinese herbal medicine Qian (Euryale ferox Salisb.). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 64, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yuan, H.; Wang, Y. Treatment of diabetes nephropathy in mice by germinating seeds of Euryale ferox through improving oxidative stress. Foods 2023, 12, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devi, M.B.; Chakraborty, S.; Nickhil, C.; Deka, S.C. Effect of Euryale ferox seed shell extract addition on the in vitro starch digestibility and predicted glycemic index of wheat-based bread. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 226, 1066–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, H.; Meng, S.; Wang, G.; Gong, Z.; Sun, W.; He, G. Hypoglycemic effect of triterpenoid-rich extracts from Euryale ferox shell on normal and streptozotocin-diabetic mice. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 27, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Yang, K.; Guo, Y.; Cao, L.; Cheng, F.; Zhang, N. Material basis and action mechanism of Euryale ferox Salisb in preventing and treating diabetic kidney disease. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.Y.; Wang, H.; He, X.X.; Wu, D.W.; Yue, W.; Wu, Q.N. The hypoglycemic and antioxidant effects of polysaccharides from the petioles and pedicels of Euryale ferox Salisb. on alloxan-induced hyperglycemic mice. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 3803–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Xue, M.; Yang, G.; Huang, Y.; Yi, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, L. The alcoholic extract of Euryale ferox seed shell inhibits the proliferation of human gastric cancer SGC7901 cells and human hepatoma HepG2 cells and promotes their apoptosis. Modern Food Science and Technology 2022, 38, 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.-R.; Kim, J.-H.; Son, E.-S.; Park, H.-R. Protective effect of extracts from Euryale ferox against glutamate-induced cytotoxicity in neuronal cells. Natural Product Sciences 2009, 15, 162–166. [Google Scholar]

| Parts | Herbal Records | Dynasty/Country | Effects | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seeds | Shen Nong’s Classic of the Materia Medica (Shén Nóng Bĕn Căo Jīng, 神农本草经) | Eastern Han Dynasty, AD 25-220, China | Eliminating dampness, easing backache and knees pain, tonifying and removing malignant diseases, benefiting the essence, strengthening the will, and making the ears and eyes wise. | [5] |

| The Compendium of Materia Medica (Bĕn Căo Gāng Mù, 本草纲目) | Ming Dynasty, AD 1578, China | Quenching thirst and benefiting the kidney, treating urinary incontinence, spermatorrhea, and leucorrhea. | [28] | |

| The Song of Medicinal Properties and four hundred flavours (Yào Xìng Gē Kuò Sì Bǎi Wèi Bái Huà Jiě, 药性歌括四百味) | Ming Dynasty, AD 1581, China | Benefitting the essence, relieving soreness of the waist and knees, arresting seminal emission. | [29] | |

| Leigong Concocted Medicinal Annotation (Léi Gōng Páo Zhì Yào Xìng Jiě,雷公炮制药性解) | Ming Dynasty, AD 1622, China | Tonifying the spleen and stomach, benefitting the essence, improving visual and auditory acuity, and amnesia. | [29] | |

| Essentials of Chinese Materia Medica (Běn Cǎo Bèi Yào, 本草备要) | Kangxi XXXIII, AD 1694, China | Strengthening the kidney and benefiting the essence, tonifying the spleen and eliminating dampness. Treating diarrhea with turbidity and spermatorrhea. | [29] | |

| Chinese Pharmacopoeia | AD 2020, China | Benefiting the kidney and consolidating sperm, tonifying the spleen and inhibiting diarrhoea, eliminating dampness and arresting leucorrhea, improving spermatorrhea, enuresis and frequent urination, splenoasthenic diarrhea, and leucorrhea. | [9] | |

| Traditional Medical & Pharmaceutical Database | Japan | Improving metabolic arthritis, urinary incontinence, and leucorrhea, easing waist pain. | - | |

| Ayurveda and Unani system | India | Improving rheumatic and bile disorders, against dysmenorrhea and exerting spermatogenic properties. | [27] | |

| Stems | The Compendium of Materia Medica (Bĕn Căo Gāng Mù, 本草纲目) | Ming Dynasty, AD 1578, China | Quenching irritability and thirst, eliminating asthenia-heat syndrome. | [28] |

| Leaves | The Compendium of Materia Medica (Bĕn Căo Gāng Mù, 本草纲目) | Ming Dynasty, AD 1578, China | Treating retained placenta and haematemesis. | [28] |

| Roots | The Compendium of Materia Medica (Bĕn Căo Gāng Mù, 本草纲目) | Ming Dynasty, AD 1578, China | Improving swollen testicles, abdominal pain due to stagnation of vital energy. | [28] |

| No. | Compounds | Molecular Formula | Type | Plant Part | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | EPJ | - | Polysaccharide | Seeds | [31] |

| 2 | EFSP-1 | - | Polysaccharide | Seeds | [32] |

| 3 | Gallic acid | C7H6O5 | Polyphenol | Seed shells, Seeds | [12,16,36] |

| 4 | Pyrogallol | C6H6O3 | Polyphenol | Seed shells | [36] |

| 5 | Chlorogenic acid | C16H18O9 | Polyphenol | Seed shells | [36] |

| 6 | Resveratrol | C14H12O3 | Polyphenol | Seeds | [16] |

| 7 | 4-O-methyl gallic acid | C8H8O5 | Polyphenol | Seeds | [37] |

| 8 | Protocatechuic acid | C7H6O4 | Polyphenol | Seeds | [12] |

| 9 | Naringenin | C15H12O5 | Flavonoid | Seed shells, Seeds | [18,38,39] |

| 10 | Dihydrotricetin | C15H12O7 | Flavonoid | Seed shells | [18] |

| 11 | Pectolinarigenin | C17H16O6 | Flavonoid | Seeds | [12] |

| 12 | Rutin | C27H30O16 | Flavonoid | Seed shells | [36] |

| 13 | Cyclo(Pro-Ser) | C8H12O3N2 | Cyclodipeptide | Seeds | [38] |

| 14 | Cyclo(Ile-Ala) | C9H16O2N2 | Cyclodipeptide | Seeds | [38] |

| 15 | Cyclo(Leu-Ala) | C9H16O2N2 | Cyclodipeptide | Seeds | [38] |

| 16 | Cyclo(Phe-Ser) | C12H14O3N2 | Cyclodipeptide | Seeds | [40] |

| 17 | Cyclo(Ala-Pro) | C8H12O2N2 | Cyclodipeptide | Seeds | [40] |

| 18 | Cyclo(Phe-Ala) | C12H14O2N2 | Cyclodipeptide | Seeds | [40] |

| 19 | N-α-hydroxy-cis-octadecaenoyl-l-O-β-glucopyranosylsphingosine | C42H79O9N | Cerebroside | Rhizomes with adventitious root | [41] |

| 20 | Peracetylated cerebroside | C54H91O15N | Cerebroside | Rhizomes with adventitious root | [41] |

| 21 | (2S,3R,4E,8E,2′R)-1-O-(β-glucopyranosyl)-N-(2′-hydroxydocosanoyl)-4,8-sphingadienine | C44H83O9N | Cerebroside | Seeds | [42] |

| 22 | (2S,3R,4E,8E,2′R)-1-O-(β-glucopyranosyl)-N-(2′-hydroxytetracosanoyl)-4,8-sphingadienine | C46H87O9N | Cerebroside | Seeds | [42] |

| 23 | β-sitosterol | C29H50O | Steroid | Seeds | [12] |

| 24 | Daucosterol | C35H60O6 | Steroid | Seeds | [12] |

| 25 | Fucosterol | C29H48O | Steroid | Seeds | [37] |

| 26 | 24-methylcholest-5-enyl-3β-O-pyranoglucoside | C43H49O10 | Steroid | Rhizomes with adventitious root | [43] |

| 27 | 24-ethylcholest-5-enyl-3β-O-pyranoglucoside | C44H51O10 | Steroid | Rhizomes with adventitious root | [43] |

| 28 | 24-ethylcholesta-5,22E-dienyl-3β-O-pyranoglucoside | C44H49O10 | Steroid | Rhizomes with adventitious root | [43] |

| 29 | 2β-hydroxybetulinic acid 3β-caprylate | C38H62O5 | Pentacyclic triterpene | Seeds | [44] |

| 30 | 2β-hydroxybetulinic acid 3β-oleiate | C48H80O5 | Pentacyclic triterpene | Seeds | [45] |

| 31 | α-tocopherol | C29H50O2 | Tocopherol | Seeds | [38,46,47] |

| 32 | β-tocopherol | C28H48O2 | Tocopherol | Seeds | [38] |

| 33 | δ-tocopherol | C27H46O2 | Tocopherol | Seeds | [38] |

| 34 | Ferotocotrimer C/E | C86H142O6 | Tocopherol | Seeds | [42,48] |

| 35 | Ferotocotrimer D | C86H142O6 | Tocopherol | Seeds | [42] |

| 36 | Tocopherol trimer IVa | C87H144O6 | Tocopherol | Seeds | [42] |

| 37 | Tocopherol trimer IVb | C87H144O6 | Tocopherol | Seeds | [42] |

| 38 | Ferotocodimer A | C58H98O5 | Tocopherol | Seeds | [48] |

| 39 | Euryalin A | C31H38O10 | Lignan | Seeds | [39] |

| 40 | Euryalin B | C30H36O9 | Lignan | Seeds | [39] |

| 41 | Euryalin C | C32H40O12 | Lignan | Seeds | [39] |

| 42 | rel-(2R,3β)-7-O-methylcedrusin | C20H24O6 | Lignan | Seeds | [39] |

| 43 | syringylglycerol-8-O-4-(sinapyl alcohol) ether | C23H30O9 | Lignan | Seeds | [39] |

| 44 | (1R,2R,5R,6S)2-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-6-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-3,7-dioxabicyclo[3.3.0]octane | C20H22O6 | Lignan | Seeds | [39] |

| 45 | (+)-syringaresinol | C22H26O8 | Lignan | Seeds | [39] |

| 46 | Buddlenol E | C31H36O11 | Lignan | Seeds | [18,39] |

| 47 | (+)-Isolariciresinol 9'-O-glucoside | C26H34O11 | Lignan | Seeds | [38] |

| 48 | 3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzyl)-4-[(7'R),5'-dihydroxy-3'-methoxybenzyl] tetrahydrofuran | C20H24O6 | Lignan | Seeds | [37] |

| 49 | Furfural | C5H4O2 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 50 | Pentanoic acid | C5H10O2 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 51 | 2-methyl-3-pentanone | C6H12O | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 52 | 5-methyl-2-furancarboxaldehyde | C7H14O | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 53 | Hexanoic acid | C6H12O2 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 54 | 4, 4, 8-trimethyl-non-7-en-2-one | C12H22O | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 55 | 1-(2-butoxyethoxy)- 2-propanol | C9H20O3 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 56 | Phenol | C6H6O | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 57 | 2-methylphenol | C7H8O | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 58 | 4-methylphenol | C7H8O2 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 59 | 4-ethylphenol | C8H10O | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 60 | Isocreosol | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] | |

| 61 | 4-ethylguaiacol | C9H12O2 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 62 | 2, 6-dimethoxyphenol | C8H10O3 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 63 | 4-methoxy-2, 3, 6-trimethylphenol | C10H14O2 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 64 | 3, 4-dimethoxytoluene | C9H12O2 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 65 | 3-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyanisole | C11H16O2 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 66 | 1, 2, 3-trimethoxybenzene | C9H12O3 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 67 | [3.1.1] hept-3-en-2-one, 4, 6, 6-trimethyl-bicyclo | C10H14O | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 68 | Butylated hydroxytoluene | C15H24O | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 69 | 1S, 4R, 7R, 11R-1, 3, 4, 7-tetramethyltricyclo [5.3.1.0(4, 11)] undec-2-en-8-one | C15H22O | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 70 | 2, 6-bis (1, 1-dimethylethyl)-2, 5-cyclohexadiene-1, 4-dione | C14H20O2 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 71 | 2-methylnaphthalene | C₁₁H₁₀ | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 72 | Pentamethyl benzene | C11H16 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 73 | 1-ethylidene-1H-indene | C11H10 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 74 | Tridecane | C13H28 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 75 | Pentadecane | C15H32 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 76 | Hexadecane | C16H34 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 77 | Dodecane | C12H26 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 78 | Tetradecane | C14H30 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 79 | Heptadecane | C17H36 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 80 | Octadecane | C18H38 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 81 | Nonadecane | C19H40 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 82 | Palmitic acid | C16H32O2 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

| 83 | Linoleic acid | C18H32O2 | Essential oil | Seeds | [46] |

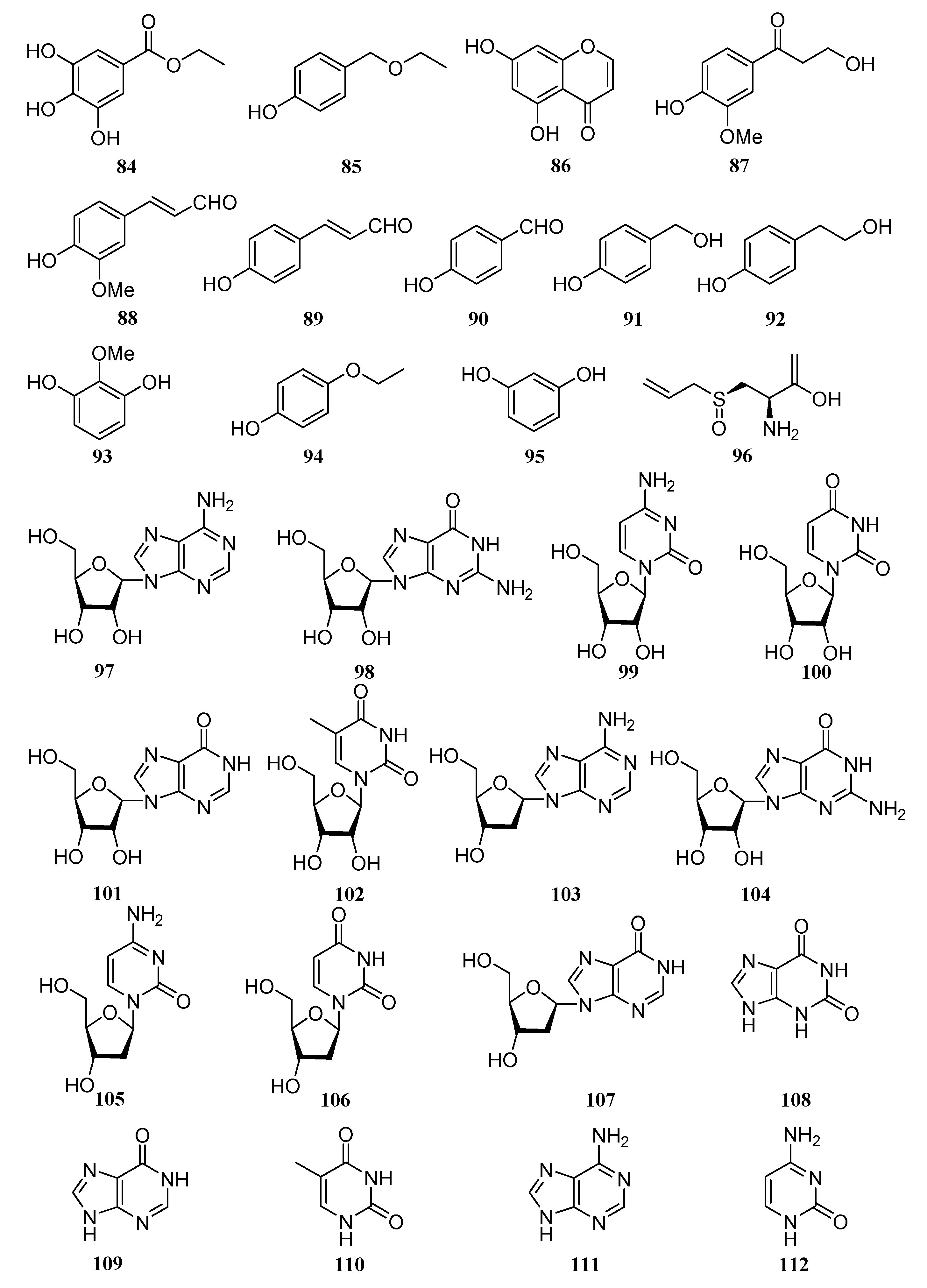

| 84 | Ethyl gallate | C9 H10O5 | Ester | Seeds | [12] |

| 85 | 4-hydroxybenzylethyl ether | C8H10O2 | Ether | Seeds | [39] |

| 86 | 5,7-dihydroxychromone | C9H6O4 | Ketone | Seeds | [12] |

| 87 | ω-hydroxypropioguaiacone | C10H12O4 | Ketone | Seeds | [39] |

| 88 | Coniferyl aldehyde | C10H10O3 | Aldehyde | Seeds | [39] |

| 89 | Trans-p-hydroxycinnamaldehyde | C9H8O2 | Aldehyde | Seeds | [39] |

| 90 | p-hydroxybenzaldehyde | C7H6O2 | Aldehyde | Seeds | [39] |

| 91 | p-hydroxybenzyl alcohol | C7H8O2 | Alcohol | Seeds | [39] |

| 92 | p-hydroxyphenethyl alcohol | C8H10O2 | Alcohol | Seeds | [39] |

| 93 | 2-methoxybenzene-1,3-diol | C7H8O3 | Phenyl alcohol | Seeds | [39] |

| 94 | 4-ethoxyphenol | C8H10O2 | Phenol | Seeds | [39] |

| 95 | Resorcinol | C6H6O2 | Phenol | Seeds | [37] |

| 96 | Alliin | C6H11NO3S | Sulfoxide | Seeds | [16] |

| 97 | Adenosine | C10H13N5O4 | Nucleoside | Seeds | [49] |

| 98 | Guanosine | C10H13N5O5 | Nucleoside | Seeds | [49] |

| 99 | Cytidine | C9H13N3O5 | Nucleoside | Seeds | [49] |

| 100 | Uridine | C9H12N2O6 | Nucleoside | Seeds | [49] |

| 101 | Inosine | C10H12N4O5 | Nucleoside | Seeds | [49] |

| 102 | Thymidine | C10H14N2O5 | Nucleoside | Seeds | [49] |

| 103 | 2’-deoxyadenosine | C10H13N5O3 | Nucleoside | Seeds | [49] |

| 104 | 2’-deoxyguanosine | C10H13N5O4 | Nucleoside | Seeds | [49] |

| 105 | 2’-deoxycytidine | C9H13N3O4 | Nucleoside | Seeds | [49] |

| 106 | 2’-deoxyuridine | C9H12N2O5 | Nucleoside | Seeds | [49] |

| 107 | 2’-deoxyinosine | C10H12N4O4 | Nucleoside | Seeds | [49] |

| 108 | Xanthine | C5H4N4O2 | Nucleobase | Seeds | [49] |

| 109 | Hypoxanthine | C5H4N4O | Nucleobase | Seeds | [49] |

| 110 | Thymine | C5H6N2O2 | Nucleobase | Seeds | [49] |

| 111 | Adenine | C5H5N5 | Nucleobase | Seeds | [49] |

| 112 | Cytosine | C4H5N3O | Nucleobase | Seeds | [49] |

| Activity | Compound/Extract | Plant Part | Animals/Cell Lines | Doses | Effects | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antioxidation and anti-inflammation | Methanol extract | Seeds | DPPH scavenging assays V79-4 cell line RAW 264.7 cell line |

For antioxidation, 0.8-100 μg/ml For antiinflammation, 100-400 μg/ml |

DPPH radical scavenging activity (IC50 22.95±0.25 μg/ml or 5.6 μg/ml); iNOS, Cox-2, NO inhibition (300-400 μg/ml); Inhibition of lipid peroxidation (IC50 20.5 μg/ml) | [19,20] |

| Ethanol extract Compounds 40, 42-46 |

Seeds | DPPH scavenging assays ROS model: glucose treated mesangial cells |

For DPPH: 2-1000 μg/mL For ROS: 1, 10 μM |

DPPH (SC50) of ethanol extract, compounds 40-43, 45 were 103.1 μg/ml, 6.8, 10.4, 10.2, and 12.9 μM, respectively; Compounds 40, 42, 44-46 showed ROS inhibition at 10 μM | [39] | |

| Aqueous extracts | Seeds | DPPH and ABTS scavenging activity H2O2-induced human skin fibroblast oxidative stress |

/ | DPPH and ABTS scavenging; Increased expression of SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px | [21] | |

| Phenolic extracts | Seed shells | DPPH scavenging assays | 0.1-1.0 mg/mL | DPPH scavenging activity is similar to vitamin C and Trolox at 1 mg/mL | [36] | |

| Phenolic extracts | Seed shells | DPPH and Hydroxyl scavenging assays D-galactose-induced aging Kunming mice |

In vitro: 0.01-2 mg/mL In vivo: 100, 200, 400 mg/kg p.o. once daily for 32 days |

Strong DPPH and Hydroxyl scavenging activity; Increases the SOD, CAT, GSH-Px activities and decreases MDA content in the liver and kidneys | [18] | |

| Anthocyanins extraction | Leaves | DPPH and ABTS scavenging activity | / | DPPH and ABTS scavenging IC50 were 74.00±3.63 μg/mL and 5.77±0.28 μg/mL, respectively | [26] | |

| Ethyl acetate, ethanol, or 50% ethanol extract | Seed shells | DPPH scavenging assays Lipid peroxidation |

5-200 μg/mL | DPPH radical scavenging activity (IC50 29.4±1.34, 28.3±1.21, 27.60±1.02 μg/mL, respectively); Inhibition of lipid peroxidation (IC50 43.86±1.32, 30.44±1.15, 36.42±1.43, respectively) | [54] | |

| Cell wall polysaccharides | Petioles and pedicels | DPPH and ABTS scavenging activity H2O2-induced injury on HUVEC and VSMC |

For DPPH and ABTS: up to 6.5 mg/mL For cell model: 60 and 200 μg/mL |

Around 80% DPPH scavenging activity at 3.25 mg/mL, and 100% ABTS scavenging activity at 1.625 mg/mL; Reduced MDA levels, and increased T-AOC, SOD and CAT activities in H2O2-injuryed VSMC and HUVEC cells. |

[55] | |

| Essential Oil | Seeds | DPPH and ABTS scavenging activity | 0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 8 μg/mL | DPPH and ABTS scavenging IC50 were 6.27 ± 0.31 and 2.19 ± 0.61 μg/ml, respectively | [46] | |

| Antidiabetic and hypoglycemic effects | 70% ethanol extract | Seeds | Streptozotocin-induced diabetic Wistar rats | 100, 200, 300, 400 mg/kg, p.o. for 45 days | Significantly decreased the blood glucose level, increased plasma insulin level, restored hepatic gluconeogenic enzymes activities; increased activities of SOD, CAT, GPx, and GSH | [15] |

| 70% methanol extract | Germinated seeds | Streptozotocin-induced diabetic ICR mice | 100, 200, 400 mg/kg, p.o. for 4 weeks | Improved hyperglycemia, abnormal lipid metabolism, and renal tissue lesions; Decreased kidney microalbuminuria, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, MDA and GSH; Increased activity of CAT, SOD, serum total antioxidant capacity; Regulating the Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1 and AMPK/mTOR pathways. | [56] | |

| Polysaccharide (EFSP-1) | Seeds | Dexamethasone-induced HepG2 and 3T3-L1 preadipocyte cells | Incubation with 25, 100, 400 μg/mL EFSP-1 for 24 h | Increasing glucose consumption by up-regulating the expression of GLUT-4 via activating PI3K/Akt signal pathway in insulin resistance cells | [32] | |

| 2β-hydroxybetulinic acid 3β-caprylate (HBAC) | Seeds | Streptozotocin-induced diabetic Wistar rats | 20, 40, 60 mg/kg, p.o. for 45 days | Exhibited free radical scavenging property, pancreas and hepatoprotective effect; Stimulating insulin release; Improved the glycemic control and lipid profile | [44] | |

| 2β-hydroxybetulinic acid 3β-oleiate (HBAO) | Seeds | Streptozotocin-induced diabetic Wistar rats | 20, 40, 60 mg/kg, p.o. for 45 days | Alleviating glycemic homeostasis and oxidative stress, normalized plasma glucose, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), hepatic gluconeogenic enzymes, plasma insulin, ameliorating pancreatic β-cell, hepatic and renal histology and β-cell functions, improving dyslipidemia and antioxidant enzymes | [45] | |

| Ethanol extract | Seed shells | α-amylase and α-glucosidase | 20-100 μg/mL | The inhibitory effects of E. ferox seed shell extract (EFSSE) on α-amylase and α-glucosidase in terms of IC50 was 62.95 and 52.06 μg/mL, respectively. | [57] | |

| Triterpenoid-rich 75% ethanol extracts | Seed shells | Streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice | 200, 400, 600 mg/kg, p.o. for 4 weeks | Regulating glucose metabolism and body weight; Decreased cholesterol, LDL and triglycerides levels, and increased HDL | [53] | |

| Triterpenoid-rich 75% ethanol extracts | Seed shells | Streptozotocin-induced diabetic Kunming mice | 200, 300, 400, 500±2 mg/L in drinking water for 4 weeks | Restored glucose metabolism and body weight; Recovered Islet morphology; Reduced PTP1B protein and increased insulin receptor IRS-1 protein | [58] | |

| Network pharmacology method | / | The TCMSP, SymMap V2, CTD, DisGeNET, and GeneCards databases were searched for ES components, targets, and DKD targets | / | The main components are oleic acid and vitamin E, targeting the proteins PPARA, LPL, FABP1, MAPK1 to regulate TNF, apoptosis, and MAPK. | [59] | |

| Polysaccharides | Petioles and pedicels | Alloxan-induced hyperglycemic ICR mice | 100, 200, 400 mg/kg, p.o. for 28 days | High dose of EFPP reverse alloxan-induced body weight loss, reduce blood glucose level, enhance serum insulin level, improve oral glucose tolerance, increase hepatic glycogen content and GCK activity; increase SOD, CAT and GSH-Px activities and decrease MDA contents in liver and kidney | [60] | |

| Hepatoprotective and cardioprotective activities | Ethanol extract | Seed shells | High fat diet induced ICR mice | 15 and 30 mg/kg, p.o. for 28 days | Reduced body weight, lipids deposition in the liver and blood lipids, decreased MDA content and increased SOD activity; IRs-1 activation and CYP2E1 inhibition | [13] |

| Ethanol extract | Seeds | Ischemia and reperfusion in vitro model; Chronic ischemic reperfusion injury in vivo model |

25, 125 or 250 μg/ml for in vitro; 50 and 500 mg/kg, p.o. for 21 days | Improved post-ischemic ventricular function and reduced myocardial infarct size; increased expression of TRP32 and thioredoxin proteins; ROS scavenging activities | [14] | |

| Anticancer | Ethanol extract | Seeds | In vitro: A549 Human Caucasian Lung Carcinoma cancer cells In vivo: Balb/c nu/nu mice |

In vitro: 50-150μg/mL In vivo: 100 mg/kg/day for 28 days |

In vitro: promoting A549 apoptosis via inhibition of the Akt protein and activation of the p53 protein; In vivo: activating p53 and suppressing the tumor growth |

[16] |

| Ethanol extract | Seed shells | Human Gastric Cancer SGC7901 cells and Human Hepatoma HepG2 cells | 50-800 μg/mL | Inhibitory effect on the proliferation of SGC7901 cells and HepG2 cells were 92.63% and 72.40%, respectively | [61] | |

| Ethyl acetate fraction | Seeds | Melan-a cells | 3-30 μg/mL | Inhibition of cellular tyrosinase and melanin synthesis | [23] | |

| Resorcinol | Seeds | B16F10 melanoma cells | / | Inhibition of melanin synthesis in B16F10 melanoma cells with an IC50 492.8 µM | [37] | |

| Cytotoxicity | Ferocerebrosides A and B | Seeds | Brine shrimp lethality bioassay | 62.5, 125, 250, 500, and 1000 μg/mL for 24 h | Ferocerebrosides A and B showed marginal toxicity against brine shrimp with LC50 values of 0.17 and 0.20 mM, respectively | [42] |

| Polysaccharide fraction (EFSP-1) | Seeds | 3T3-L1 preadipocyte cells and HepG2 cells | 25, 50, 100, 200, 400 μg/mL for 48 h | No obvious influence to cells at 100–400 μg/mL | [32] | |

| Hexane, diethyl ether, ethyl aetate extract | Seeds | Glutamate-induced cytotoxicity in hybridoma N18RE-105 cells | 10 μg/mL for 24 h | Dose-dependent protection against neuronal cell death induced by 20 mM glutamate | [62] | |

| Anti-fatigue | Phenolics extract | Seed shells | Exhaustive swimming test | 100, 200, 400 mg/kg p.o. once daily for 32 days | The average exhaustive swimming time was obviously prolonged in all three doses | [18] |

| Anti-depressant | Petroleum ether fraction | Seeds | Chronically unpredictable mild stress (CUMS) mouse model | 0.1, 0.15 g/kg p.o. once daily for 14 days | Upregulation of AMPK and ULK1, attenuated depressive behavior via AMPK-ULK1 pathway mediated autophagy | [22] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).