Submitted:

04 May 2023

Posted:

05 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

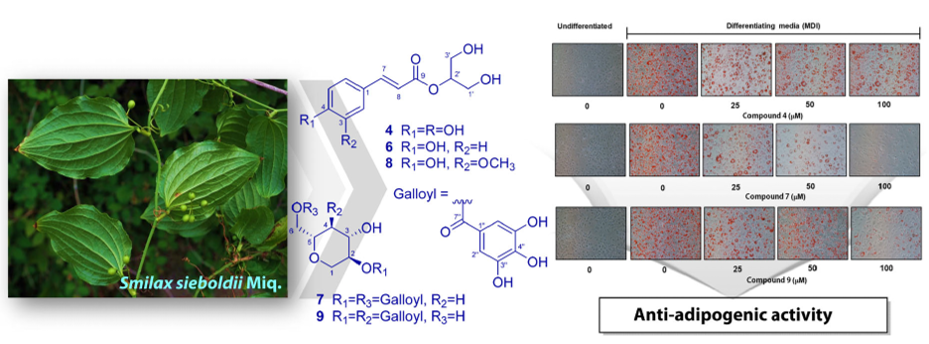

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

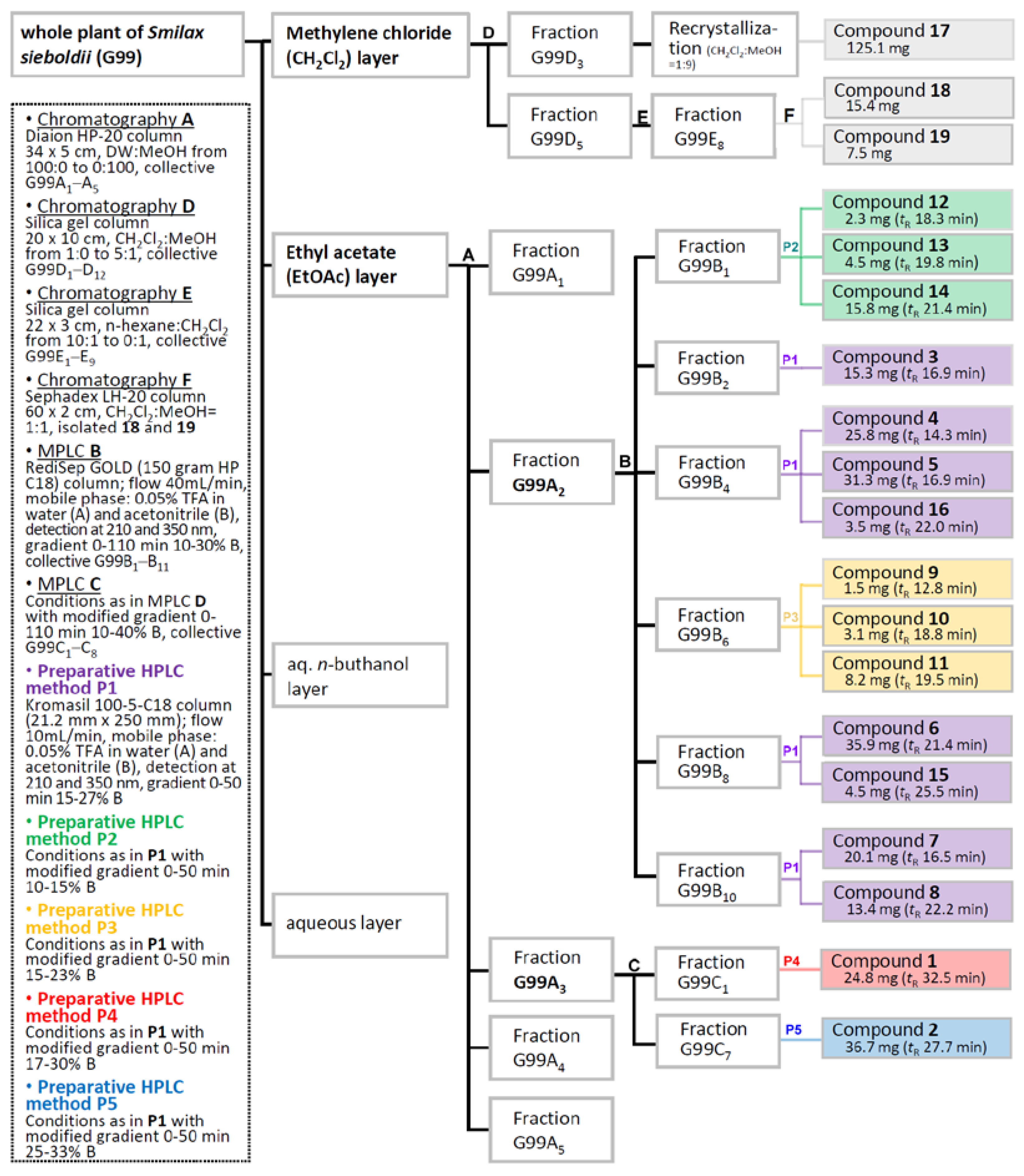

2.1. Isolation and Purification of Compounds 1–19

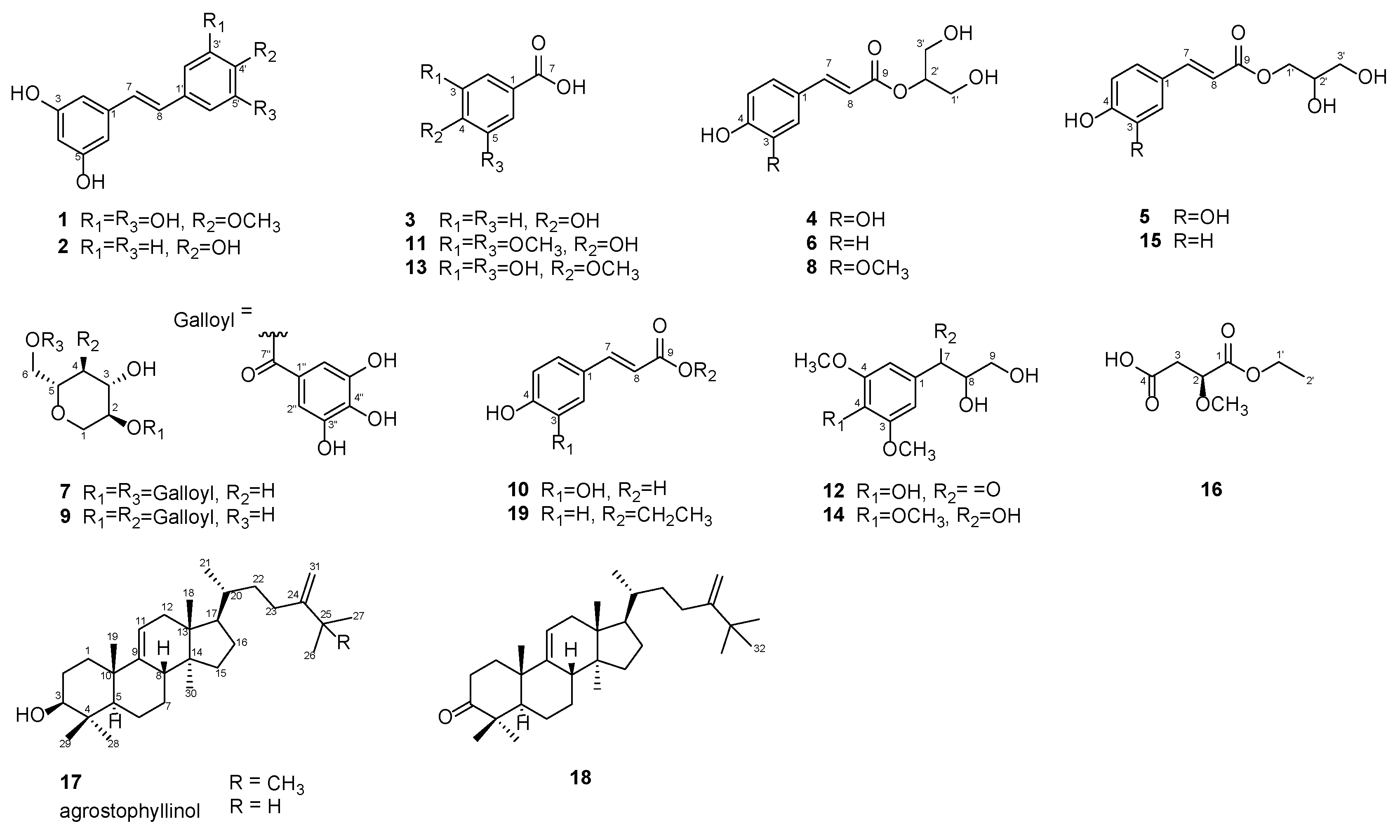

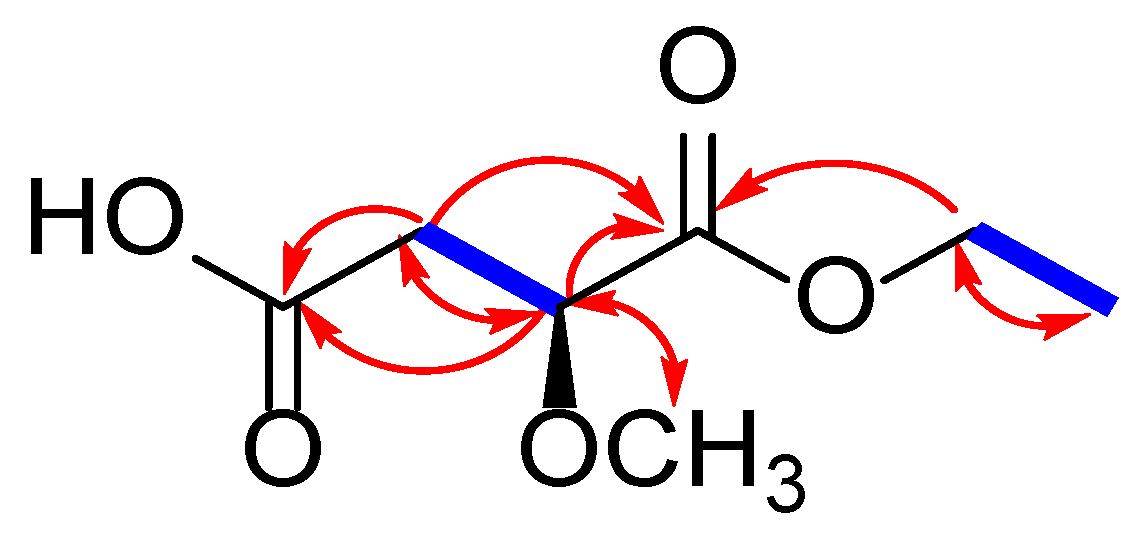

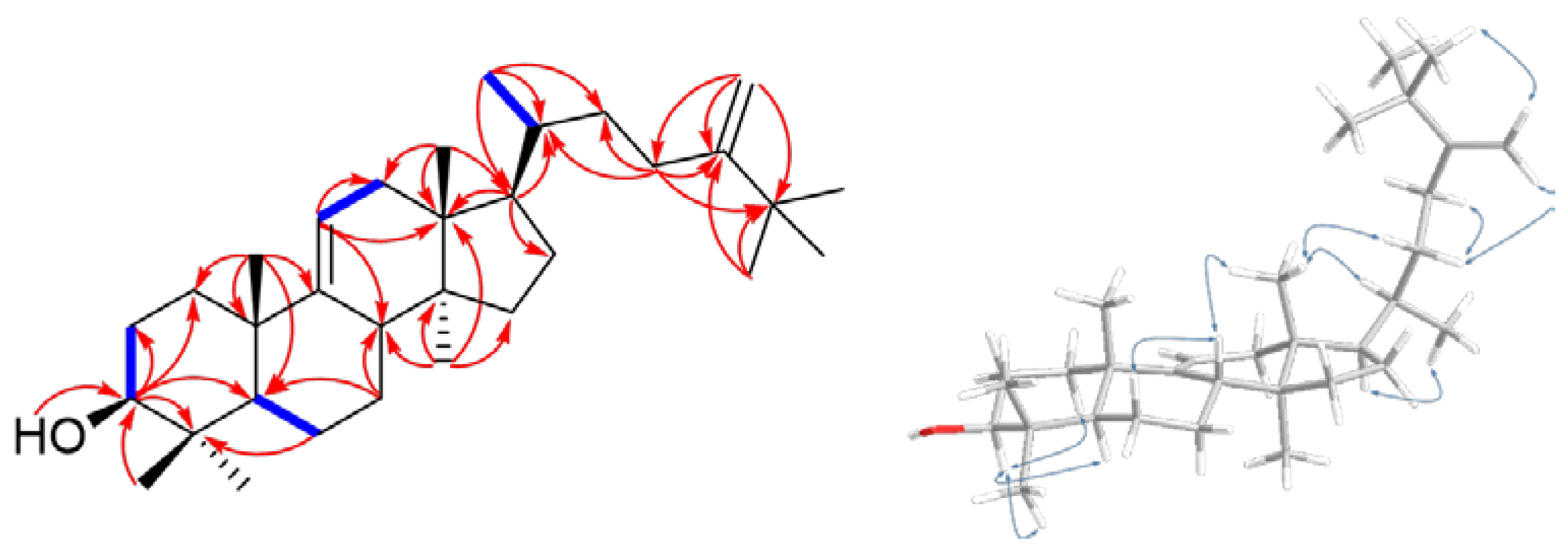

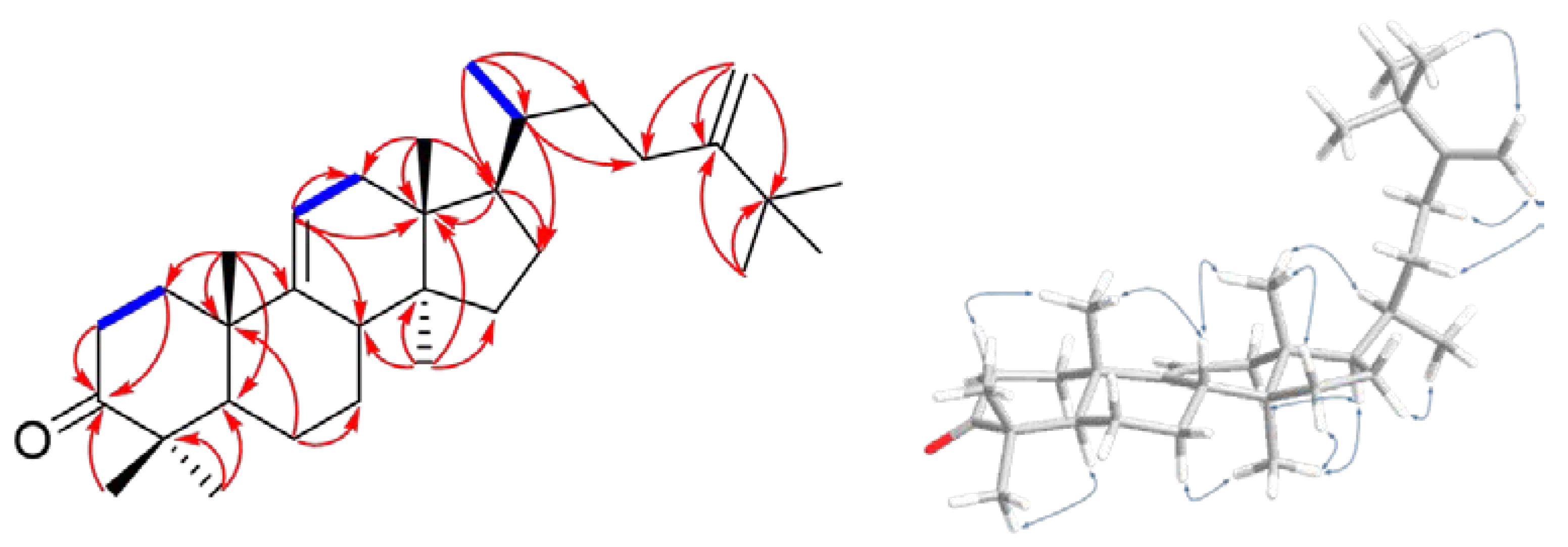

2.2. Chemical Identification of Compounds 1–19

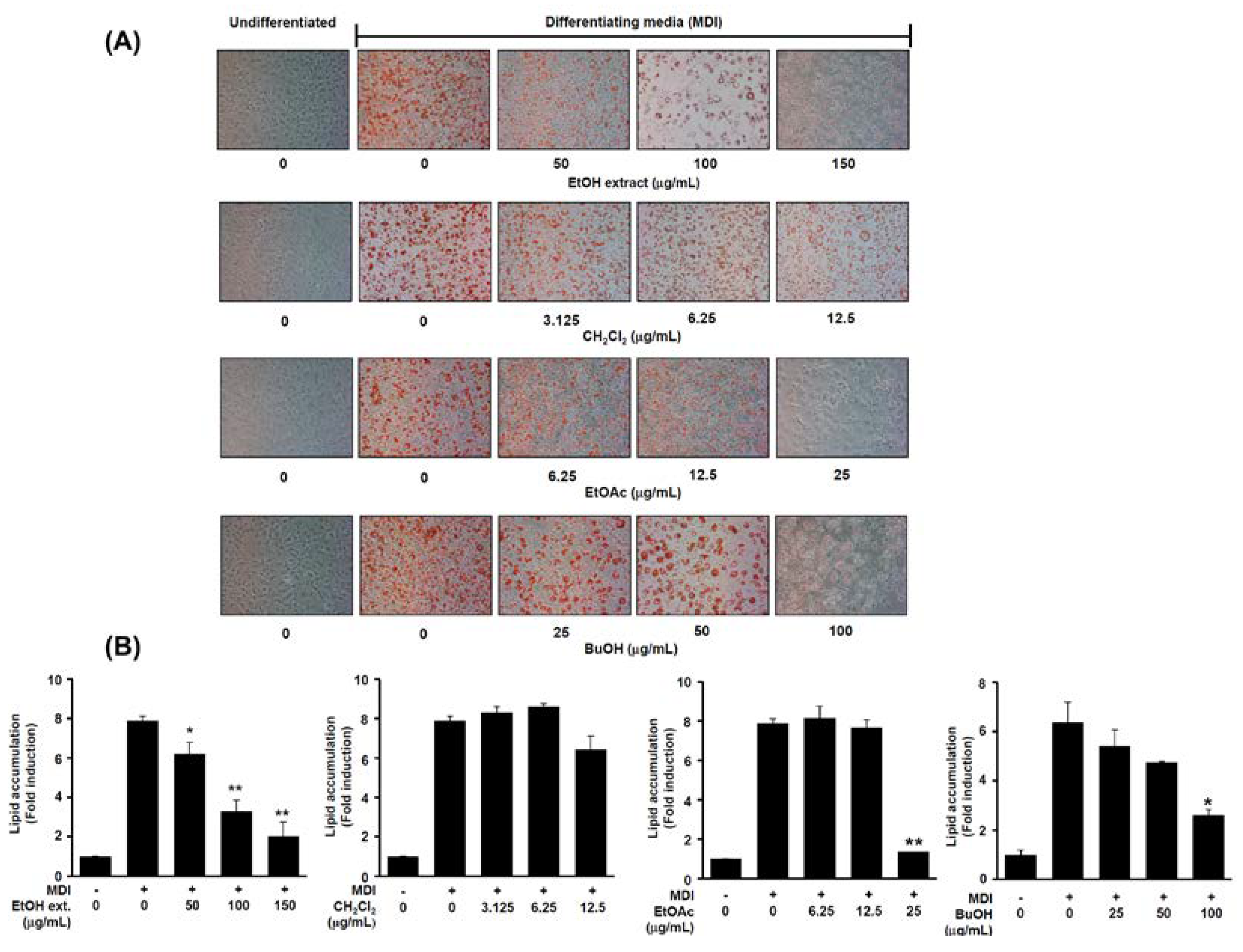

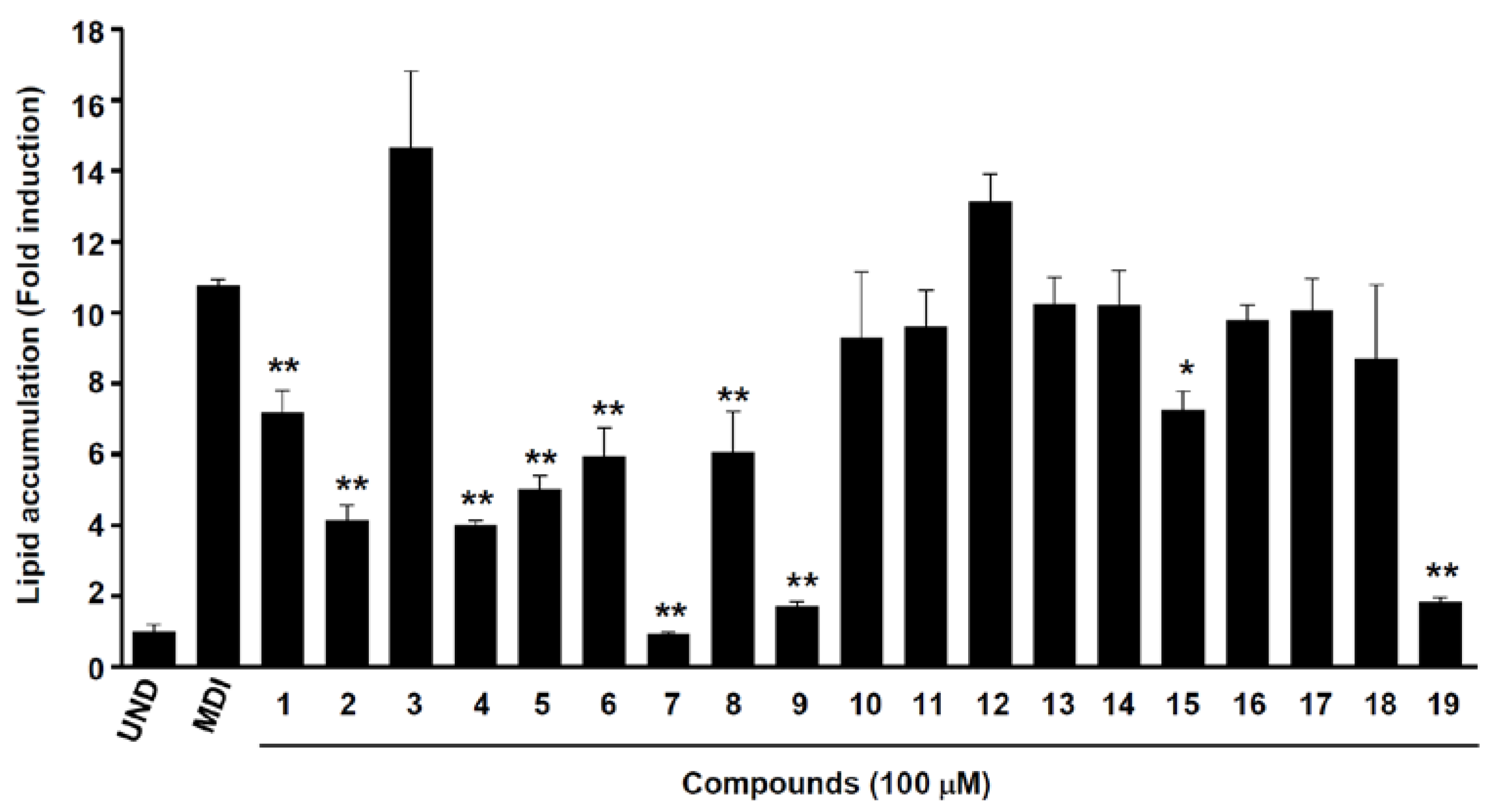

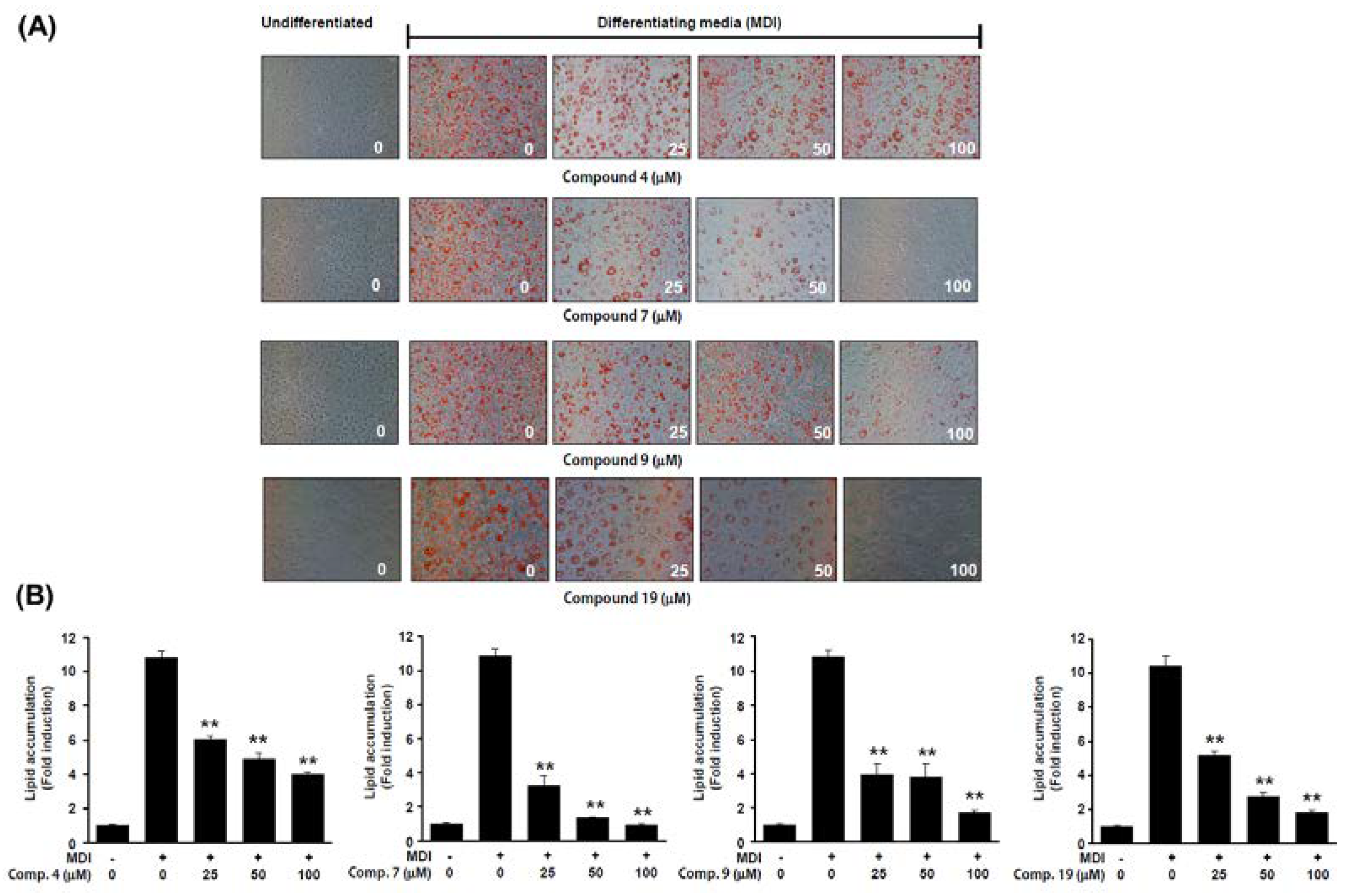

2.3. Anti-Adipogenic Effects of Isolated Compounds on 3T3-L1 Cells

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Experimental Procedure

3.2. Source of Plant Material

3.3. Extraction and Separation/Compound Isolation

3.4. Spectroscopic Data Analysis

3.5. Cell Culture and Adipocyte Ddifferentiation

3.6. Oil Red O Staining of Adipocytes Lipid Droplets

3.7. Cell Viability Assay

3.8. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization, 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on June 2021).

- Lin, X.; Li, H. Obesity: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and therapeutics. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 706978–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fruh, S.M. Obesity: Risk factors, complications, and strategies for sustainable long-term weight management. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2017, 29, S3–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermaak, I.; Viljoen, A.M.; Hamman, J.H. Natural products in anti-obesity therapy. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011, 28, 1493–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakab, J.; Miškić, B.; Mikšić, Š.; Juranić, B.; Ćosić, V.; Schwarz, D.; Včev, A. Adipogenesis as a potential anti-obesity target: A review of pharmacological treatment and natural products. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2021, 14, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, J.; Gavrilova, O.; Pack, S.; Jou, W.; Mullen, S.; Sumner, A.E.; Cushman, S.W.; Periwal, V. Hypertrophy and/or hyperplasia: Dynamics of adipose tissue growth. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009, 5, e1000324–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muir, L.A.; Neeley, C.K.; Meyer, K.A.; Baker, N.A.; Brosius, A.M.; Washabaugh, A.R.; Varban, O.A.; Finks, J.F.; Zamarron, B.F.; Flesher, C.G.; Chang, J.S.; DelProposto, J.B.; Geletka, L.; Martinez-Santibanez, G.; Kaciroti, N.; Lumeng, C.N.; O'Rourke, R.W. Adipose tissue fibrosis, hypertrophy, and hyperplasia: Correlations with diabetes in human obesity. Obesity 2016, 24, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Zhou, A.; Qi, W. The Potential to fight obesity with adipogenesis modulating compounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2299–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufau, J.; Shen, J.X.; Couchet, M.; Barbosa, T.C.; Mejhert, N.; Massier, L.; Griseti, E.; Mouisel, E.; Amri, E.Z.; Lauschke, V.M.; Rydén, M.; Langin, D. In vitro and ex vivo models of adipocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2021, 320, C822–C841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.T.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.M.; Qian, Q.; He, W.; Wang, T. Inhibitory effects of flavonoids from Abelmoschus manihot flowers on triglyceride accumulation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Fitoterapia 2011, 82, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahagi, T.; Daikonya, A.; Kitanaka, S. Flavonol acylglycosides from flower of Albizia julibrissin and their inhibitory effects on lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 cells. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2012, 60, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.S.; Choi, C.W.; Lee, J.E.; Jung, Y.W.; Lee, J.A.; Jeong, W.; Choi, Y.H.; Cha, H.; Ahn, E.K.; Oh, J.S. Bioassay-guided isolation and identification of anti-obesity phytochemicals from fruits of Amomum tsao-ko. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2021, 64, 2–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.C.; Ding, Y.; Kim, E.A.; Choi, Y.K.; De Araujo, T.; Heo, S.J.; Lee, S.H. Indole derivatives isolated from brown alga Sargassum thunbergii inhibit adipogenesis through AMPK activation in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 119–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.G.; Kim, H.S.; Je, J.G.; Hwang, J.; Sanjeewa, K.K.A.; Lee, D.S.; Song, K.M.; Choi, Y.S.; Kang, M.C.; Jeon, Y.J. Lipid inhibitory effect of (‒)-loliolide isolated from Sargassum horneri in 3T3-L1 adipocytes: inhibitory mechanism of adipose-specific proteins. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 96–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Villarreal, D.; Camacho, A.; Castro, H.; Ortiz-Lopez, R.; de la Garza, A.L. Anti-obesity effects of kaempferol by inhibiting adipogenesis and increasing lipolysis in 3T3-L1 cells. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 75, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, D.E.; Park, E.C.; Ra, M.J.; Jung, S.M.; Yu, J.N.; Um, S.H.; Kim, K.H. Anti-adipogenic effects of salicortin from the twigs of weeping willow (Salix pseudolasiogyne) in 3T3-L1 Cells. Molecules 2022, 27, 6954–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phadtare, I.; Vaidya, H.; Hawboldt, K.; Cheema, S.K. Shrimp oil extracted from shrimp processing by-product is a rich source of omega-3 fatty acids and astaxanthin-esters, and reveals potential anti-adipogenic effects in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 259–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, L.W.; Zhang, Z.; Long, H.L.; Zhang, Y.J. Steroidal saponins from the genus Smilax and their biological activities. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2017, 7, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challinor, V.L.; Parsons, P.G.; Chap, S.; White, E.F.; Blanchfield, J.T.; Lehmann, R.P.; De Voss, J.J. Steroidal saponins from the roots of Smilax sp.: Structure and bioactivity. Steroids 2012, 77, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, M.H.; Do, J.C.; Son, K.H. Five new spirostanol glycosides from the subterranean parts of Smilax sieboldii. J. Nat. Prod. 1992, 55, 1129–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.Y.; Woo, M.H.; Oh, I.S. Studies on the general constituents of the leaf and the subterranean part of, and the antihyperlipidemic effect of the subterranean part of Smilax sieboldii Miq. The Journal of The Applied Science Research Institute 1991, 1, 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Kubo, S.; Mimaki, Y.; Sashida, Y.; Nikaido, T.; Ohmoto, T. Steroidal saponins from the rhizomes of Smilax sieboldii. Phytochemistry 1992, 31, 2445–2450. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ivanova, A.; Mikhova, B.; Batsalova, T.; Dzhambazov, B.; Kostova, I. New furostanol saponins from Smilax aspera L. and their in vitro cytotoxicity. Fitoterapia 2011, 82, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, B.; Guo, H.; Cui, Y.; Ye, M.; Han, J.; Guo, D. Steroidal saponins from Smilax china and their anti-inflammatory activities. Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, R.; Kan, S.; Sugita, Y.; Shirataki, Y. ρ-Coumaroyl malate derivatives of the Pandanus amaryllifolius leaf and their isomerization. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2017, 65, 1191–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, Y.H.; Chang, C.I. Six new compounds from the heartwood of Diospyros maritima. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2000, 48, 1211–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.R.; Cheng, C.W.; Pan, M.H.; Liao, Y.W.; Tzeng, C.Y.; Chang, C.I. Lanostane-type triterpenoids from Diospyros discolor. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 55, 908–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majumder, P.L.; Majumder, S.; Sen, S. Triterpenoids from the orchids Agrostophyllum brevipes and Agrostophyllum callosum. Phytochemistry 2003, 62, 591–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.Y.; Wang, N.L.; Yao, X.S.; Miyata, S.; Kitanaka, S. Euphane and tirucallane triterpenes from the roots of Euphorbia kansui and their in vitro effects on the cell division of Xenopus. J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 630–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleszek, W.; Sitek, M.; Stochmal, A.; Piacente, S.; Pizza, C.; Cheeke, P. Resveratrol and other phenolics from the bark of Yucca schidigera Roezl. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuyen, P.N.K.; Nga, V.T.; Phuong, T.V.; Phuong, Q.N.D.; Duong, N.T.T.; Quang, T.T.; Nguyen, K.P.P. Phytochemical constituents and determination of resveratrol from the roots of Arachis hypogea L. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 2351–2358. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, C.H.; Kim, N.S.; Yang, J.H.; Lee, H.; Yang, S.; Park, S.; So, U.K.; Bae, J.B.; Eun, J.S.; Jeon, H.; Lim, J.P.; Kwon, J.; Kim, Y.S.; Shin, T.Y.; Kim, D.K. Effects of isolated compounds from Catalpa ovata on the T cell-mediated immune responses and proliferation of leukemic cells. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2010, 33, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenz, R.; Ernst, L.; Galensa, R. Phenolic acids and their glycerides in maize grits. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. 1992, 194, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, Y.Y.; Lee, S.; Nguyen, P.H.; Lee, W.; Woo, M.H.; Min, B.S.; Lee, J.H. Caffeoylglycolic acid methyl ester, a major constituent of sorghum, exhibits anti-inflammatory activity via the Nrf2/heme oxygenase-1 pathway. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 17786–17796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Shang, M.Y.; Liu, G.X.; Xu, F.; Wang, X.; Shou, C.C.; Cai, S.Q. Chemical constituents from the rhizomes of Smilax glabra and their antimicrobial activity. Molecules 2013, 18, 5265–5287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honma, A.; Koyama, T.; Yazawa, K. Anti-hyperglycemic effects of sugar maple Acer saccharum and its constituent acertannin. Food Chem. 2010, 123, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.K.; Kang, H.R.; Kim, K.H. A new feruloyl glyceride from the roots of Asian rice (Oryza sativa). Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2018, 28, 421–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Yuan, T.; Li, L.; Kandhi, V.; Cech, N.B.; Xie, M.; Seeram, N.P. Maplexins, new α-glucosidase inhibitors from red maple (Acer rubrum) stems. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 597–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, C.H.; Jeong, H.R.; Choi, G.N.; Kim, D.O.; Lee, U.; Heo, H.J. Neuroprotective and anti-oxidant effects of caffeic acid isolated from Erigeron annuus leaf. Chin. Med. 2011, 6, 25–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Yang, S.; Ma, H.; Han, Z.; Zhang, Y. Bioassay-guided separation and identification of anticancer compounds in Tagetes erecta L. flowers. Anal. Methods 2016, 8, 3255–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Kuo, Y.C.; Wang, G.J.; Kuo, Y.H.; Chang, C.I.; Lu, C.K.; Lee, C.K. Five new phenolics from the roots of Ficus beecheyana. J. Nat. Prod. 2002, 65, 1497–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, C.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Yang, L.P.; Zhai, Y.Y.; Li, S.N.; Hao, S.Y.; Chen, X.Y.; Wang, J.H.; Wang, Z.H. Chemical Constituents of Curculigo orchioides. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2020, 56, 957–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, J.; Liang, F.; Liang, J.; Liang, Y.; Li, F.; Shao, F.; Liu, R.; Huang, H. Phenylpropanoids and neolignans from Smilax trinervula. Fitoterapia 2015, 104, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, W.; Han, T.; Wang, Y.; Xin, W.B.; Zheng, C.J.; Qin, L.P. Chemical constituents of the aerial part of Atractylodes macrocephala. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2011, 46, 959–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Kim, H.; Noratto, G.; Sun, Y.; Talcott, S.T.; Mertens-Talcott, S.U. Gallotannin derivatives from mango (Mangifera indica L.) suppress adipogenesis and increase thermogenesis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes in part through the AMPK pathway. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 46, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongioi, L.M.; La Vignera, S.; Cannarella, R.; Cimino, L.; Compagnone, M.; Condorelli, R.A.; Calogero, A.E. The role of resveratrol administration in human obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, P.; Zhao, L.; Chen, J. Physiologically achievable doses of resveratrol enhance 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 54, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Posovszky, P.; Kukulus, V.; Tews, D.; Unterkircher, T.; Debatin, K.M.; Fulda, S.; Wabitsch, M. Resveratrol regulates human adipocyte number and function in a Sirt1-dependent manner. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, X.; Xu, B.; Zeng, G.; Tan, J.; He, X.; Hu, C.; Zhou, Y. Chemical constituents of Morus alba L. and their inhibitory effect on 3T3-L1 preadipocyte proliferation and differentiation. Fitoterapia 2014, 98, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Lu, S.; Li, D.; Lu, J.; Zhou, L.; Qiu, M. Cycloartane triterpene glycosides from rhizomes of Cimicifuga foetida L. with lipid-lowering activity on 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Fitoterapia 2020, 145, 104635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Position | 16 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| δH (J in Hz) | δC (mult.) | |||

| 1 | 173.5 s | |||

| 2 | 4.16 dd (8.4, 4.2) | 78.6 d | ||

| 3 | 2.71 dd (16.1, 4.2); 2.60 dd (16.1, 8.4) | 39.4 t | ||

| 4 | 174.7 s | |||

| 1' | 4.22 dd (7.0, 2.8); 4.20 dd (7.0, 3.5) | 62.4 t | ||

| 2' | 1.28 t (7.0) | 14.6 q | ||

| OCH3 | 3.41 s | 59.0 q | ||

| aAssignments confirmed by 1H-1H COSY, HSQC, and HMBC experiments. | ||||

| position | 17 | 18 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δH (J in Hz) | δC (mult.) | δH (J in Hz) | δC (mult.) | ||

| 1α | 1.42 m | 36.3 t | 2.10 m | 36.7 t | |

| 1β | 1.77 td (13.3, 3.5) | 1.81 dt (13.3, 4.9) | |||

| 2α | 1.74 m | 28.0 t | 2.40 m | 34.9 t | |

| 2β | 1.60 m | 2.72 m | |||

| 3α | 3.20 dd (11.2, 4.2) | 79.1 d | 217.2 s | ||

| 4 | 39.3 s | 47.7 s | |||

| 5α | 0.86 m | 52.7 d | 1.37 m | 53.4 d | |

| 6α | 1.68 m | 21.6 t | 1.64 m | 22.6 t | |

| 6β | 1.45 dd (13.3, 3.5) | ||||

| 7α | 1.28 m | 28.3 t | 1.36 m | 27.7 t | |

| 7β | 1.65 m | 1.70 m | |||

| 8β | 2.16 m | 42.0 d | 2.22 m | 41.9 d | |

| 9 | 148.7 s | 147.1 s | |||

| 10 | 39.6 s | 39.1 s | |||

| 11 | 5.21 d (5.6) | 115.2 d | 5.29 d (6.3) | 116.3 d | |

| 12α | 2.06 m | 37.4 t | 2.09 m | 37.2 t | |

| 12β | 1.88 m | 1.93 m | |||

| 13 | 44.5 s | 44.3 s | |||

| 14 | 47.2 s | 47.0 s | |||

| 15α | 1.30 m | 34.1 t | 1.33 m | 33.9 t | |

| 15β | 1.37 m | 1.40 m | |||

| 16α | 1.90 m | 28.2 t | 1.95 m | 28.0 t | |

| 16β | 1.27 m | 1.31 m | |||

| 17α | 1.61 m | 51.2 d | 1.65 m | 50.9 d | |

| 18 | 0.64 s | 14.6 q | 0.68 s | 14.4 q | |

| 19 | 1.03 s | 22.5 q | 1.23 s | 21.8 q | |

| 20β | 1.39 m | 36.71 d | 1.43 m | 36.5 d | |

| 21 | 0.90 d (6.3) | 18.73 q | 0.93 d (6.3) | 18.5 q | |

| 22α | 1.14 m | 36.69 t | 1.17 m | 36.4 t | |

| 22β | 1.56 m | 1.59 m | |||

| 23α | 2.13 m | 28.4 t | 2.15 m | 28.2 t | |

| 23β | 1.85 m | 1.89 m | |||

| 24 | 159.2 s | 159.0 s | |||

| 25 | 36.5 s | 36.3 s | |||

| 26 | 1.04 s | 29.6 q | 1.06 s | 29.3 q | |

| 27 | 1.04 s | 29.6 q | 1.06 s | 29.3 q | |

| 28 | 0.97 s | 28.5 q | 1.08 s | 25.6 q | |

| 29 | 0.80 s | 15.9 q | 1.07 s | 22.0 q | |

| 30 | 0.73 s | 18.71 q | 0.75 s | 18.4 q | |

| 31 | 4.82 s, 4.65 s | 105.9 t | 4.84 s, 4.67 s | 105.8 t | |

| 32 | 1.04 s | 29.6 q | 1.06 s | 29.3 q | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).