1. Introduction

Hydrotalcite supergroup minerals [Mills et al., 2012] are natural representatives of industrially applied Layered Double Hydroxides (LDHs) [Rives, 2001]. LDHs form a class of inorganic lamellar compounds with crystal structures consisting of alternating positively charged metal-hydroxide layers (octahedral sheets) and negatively charged interlayers [Duan and Evans, 2009; Aminoff and Broome, 1931]. LDHs can be represented by the general formula [Bukhtiyarova et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2017; Kameliya et al., 2023] [M2+1-xM3+x(OH)2][An-]x/n∙mH2O, where M2+ = Mg2+, Ni2+, Fe2+, Mn2+, etc. and M3+ (e.g. Al3+, Fe3+, Cr3+ and other trivalent cations); x = 0.33 and 0.25 are the most common and correspond to the M2+:M3+ = 2:1 and 3:1 ratios, respectively, that are the most widespread among LDHs; An- is the anion of the n negative charge (the most common among mineral are CO32-, Cl-, SO42-, Sb(OH)6-); m is the number of interlayer H2O molecules. This general formula is further extended by minerals of (i) the wermlandite group [Rius and Allmann, 1984; Zhitova et al., 2021; Huminicki and Hawthorne, 2003; Cooper and Hawthorne, 1996] and their synthetic counterparts [Sotiles et al., 2019a,b; Sotiles and Wypych, 2020] that contain additional interlayera mono- or divalent cations (like Na, K, Ca etc.) and (ii) Li-Al (i.e. M+-M3+) LDHs, the structures of which are represented by gibbsite-like layers [Serna et al., 1982; Sissoko et al., 1985] with the general formula of such compounds given as [Al4Li2(OH)2][An-]x/n∙mH2O.

Magnesium-aluminum LDHs with carbonate interlayer are among the longest known in the LDH family and applied as catalytic materials [Karcz et al., 2020,2021] and considered efficient and inexpensive oxygen evolution reaction electrocatalysts [Yin et al., 2023]. Mg-Al LDHs are often used as model systems for the LDH family of different (rare) chemical compositions (for example, the substitution of cations while maintaining stoichiometry). The Mg-Al-CO3 LDHs are applied in pharmacology as a Talcid medicine. Recent pharmaceutical studies involving Mg-Al LDHs include hybrid materials with glibenclamide [Leao et al., 2019], nanocarriering material for antimicrobial chemotherapy [Francius et al., 2023] and porous nanocomposite of LDH with chitosan for cosmetic application [Kim et al., 2021]. LDHs, including Mg-Al varieties, are considered as sorbents of undesirable anions and cations; recent research include: methyl orange [Zaghloul et al., 2021; Gregoire et al., 2019], PbII [Zhao et al., 2011], CuII [Yang et al., 2021], Congo red dye [Nestroinaia et al., 2022] removal from aqueous solution; harmful anion (such as Cl-, Br-, I-, AsO43-, etc.) sorption from fertile soil [Guo et al., submitted]. The uptake of Cl- and CO32- anions by Mg-Al and Ca-Al LDHs from pore solutions was simulated for cementous materials [Ke et al., 2017]. The possibility of anion uptake by LDHs also makes them advanced materials for the CO2 capture [Sakai et al., 2022]. High industrial and material science interest towards LDHs requires detailed understanding of the internal structure of these materials. Highly crystalline and extremely stable prototypes of such materials are natural compounds [Zhitova et al., 2023] – hydrotalcite supergroup minerals [Mills et al., 2012].

Despite wide chemical variability of LDHs, their crystal structures show a certain structural commonality in which one structural type extends to compounds of different compositions. For example, quintinite is isotypic to Li-Al gibbsite-based mineral akopovaite, Al4Li2(OH)12CO3∙3H2O [Zhitova et al., 2019a], following the substitution scheme [Mg4Al2(OH)12]2+ → [Al4Li2(OH)12]2+. Both structures show cation (Mg/Al or Al/Li) ordering according to the × superstructures and identical scheme of interlayer species arrangement despite rather principal chemical variability. The same applies to their Cl-analogues: chlormagaluminite, Mg4Al2(OH)2Cl2∙3H2O, [Zhitova et al., 2019b], and dritsite, Al4Li2(OH)12Cl2∙3H2O [Zhitova et al., 2019c]. Comparison of the crystal structures of minerals shows that they are isotypic to their synthetic analogues, which is well shown by Li-Al LDHs [Britto et al., 2008; 2009 and 2011]. Therefore, the crystal structures obtained on minerals through single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis (the technique that makes it possible to obtain models of crystal structures with greater accuracy) can be extended to industrially applied synthetic LDH materials.

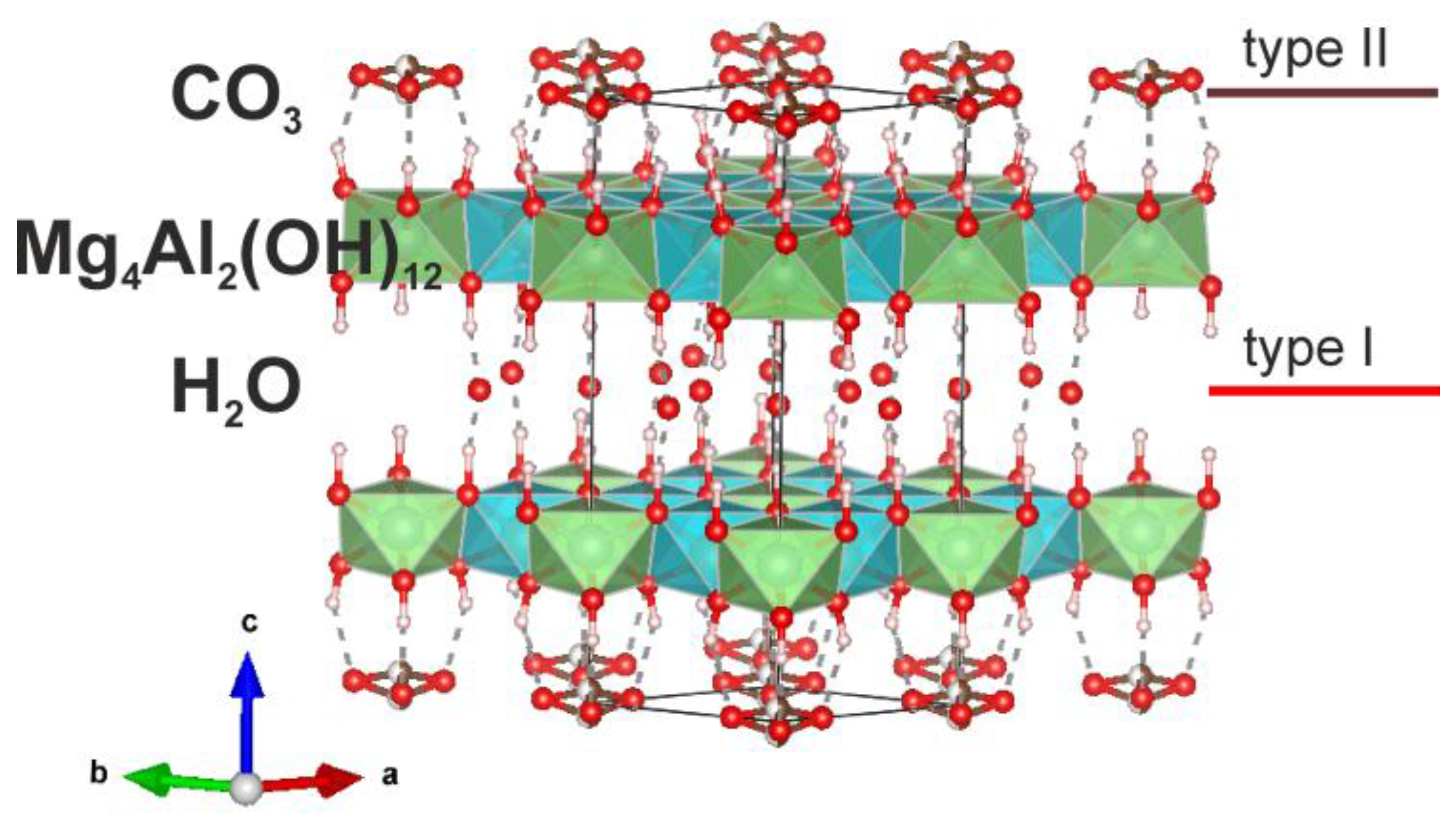

In this study we provide crystal chemical characterization of quintinite from Jacupiranga (São Paulo, Brazil). Previously the crystal structure of quintinite from that locality has been described as stratified with two types of interlayers (see details below), which contradicts the more recent studies of quintinite from the Kovdor complex [Krivovichev et al., 2010a,b,2012; Zhitova et al., 2010,2018]. The goal of the present study is to resolve this contradiction, i.e. to check whether quintinites from different localities are isotypic to each other or not. In addition, we provide data that should be helpful for the identification of cation-ordered polytypes with hexagonal stacking sequences by powder X-ray diffraction method.

Previous crystal structure studies of quintinite

The first crystal structure study of quintinite (at that time – “manasseite” i.e. hydrotalcite) has been carried out on the sample from Jacupiranga [Arakcheeva et al., 1996]. The study demonstrated the presence of the Mg and Al ordering according to the

×

superstructure in the metal-hydroxide layer (or octahedral sheet); hexagonal layer stacking sequence and stratified interlayer that consisted of two types: (i) (H

2O) molecules and (ii) (CO

3)

2- that alternated along

z direction [Arakcheeva et al., 1996] (

Figure 1).

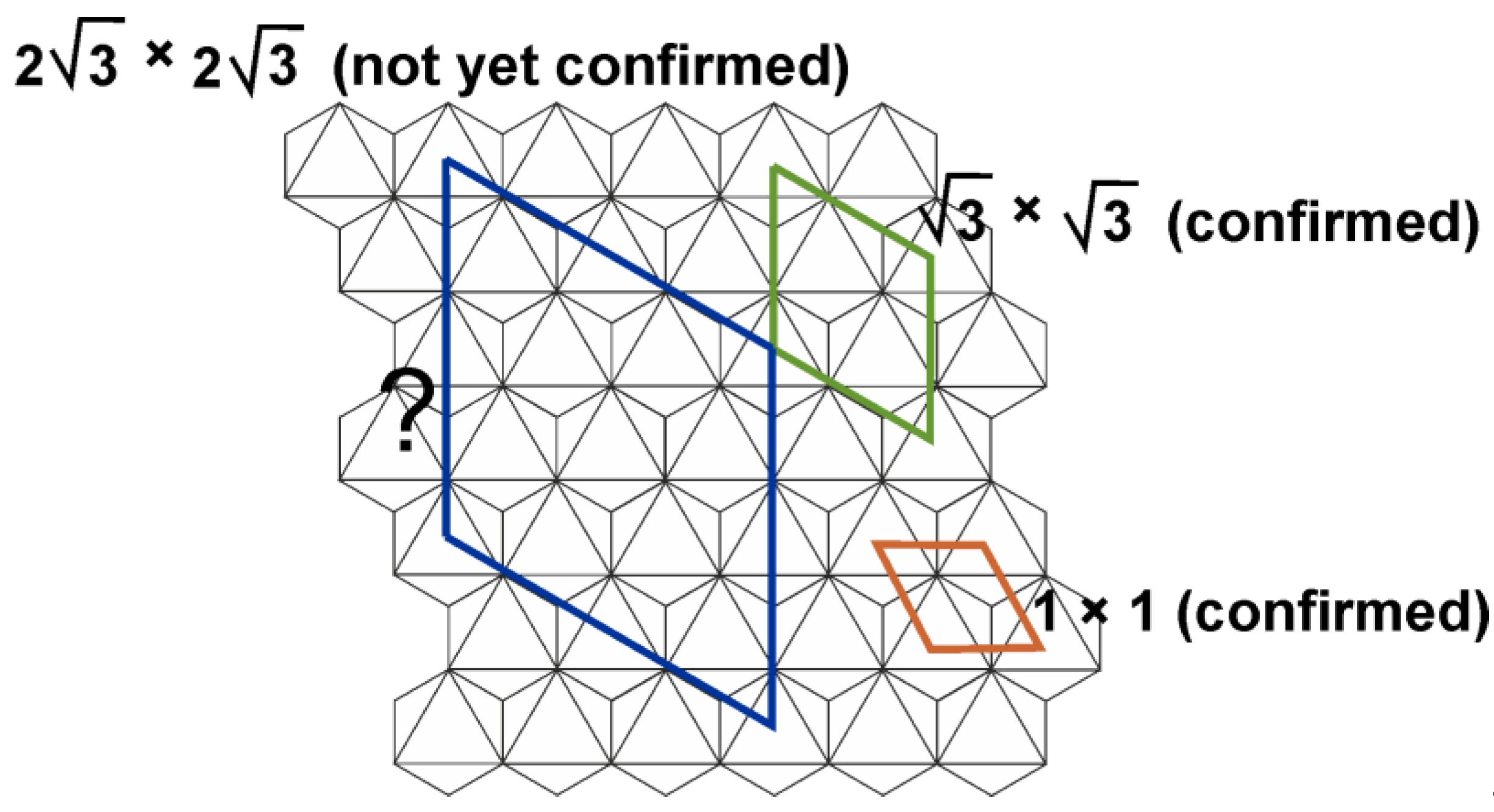

Almost simultaneously, quintinite has been approved as a separate (from hydrotalcite/manaseite) mineral species on the samples from alkaline complex of Mont Saint-Hilaire, Quebec [Chao and Gault, 1997]. The crystal structure has not been refined, but unit-cell parameters determined indicative of polytypes with the hexagonal and rhombohedral layer stacking sequences with doubled in comparison to previous data [Arakcheeva et al., 1996] lattice parameter

a according to the 2

× 2

superstructure (which, however, has not been identified elsewhere else) (

Figure 2).

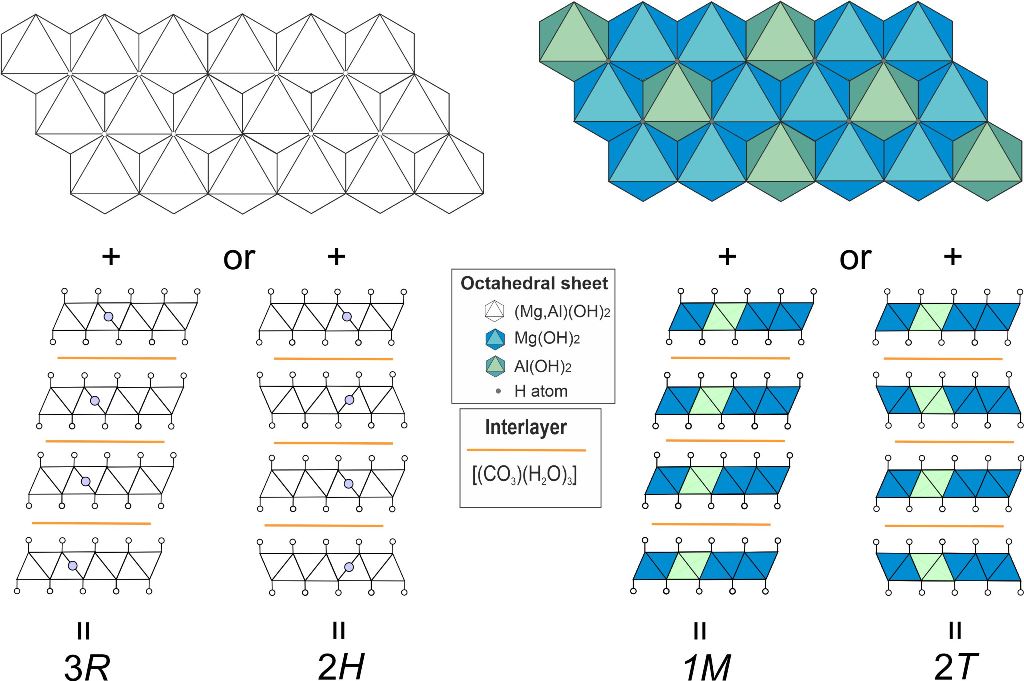

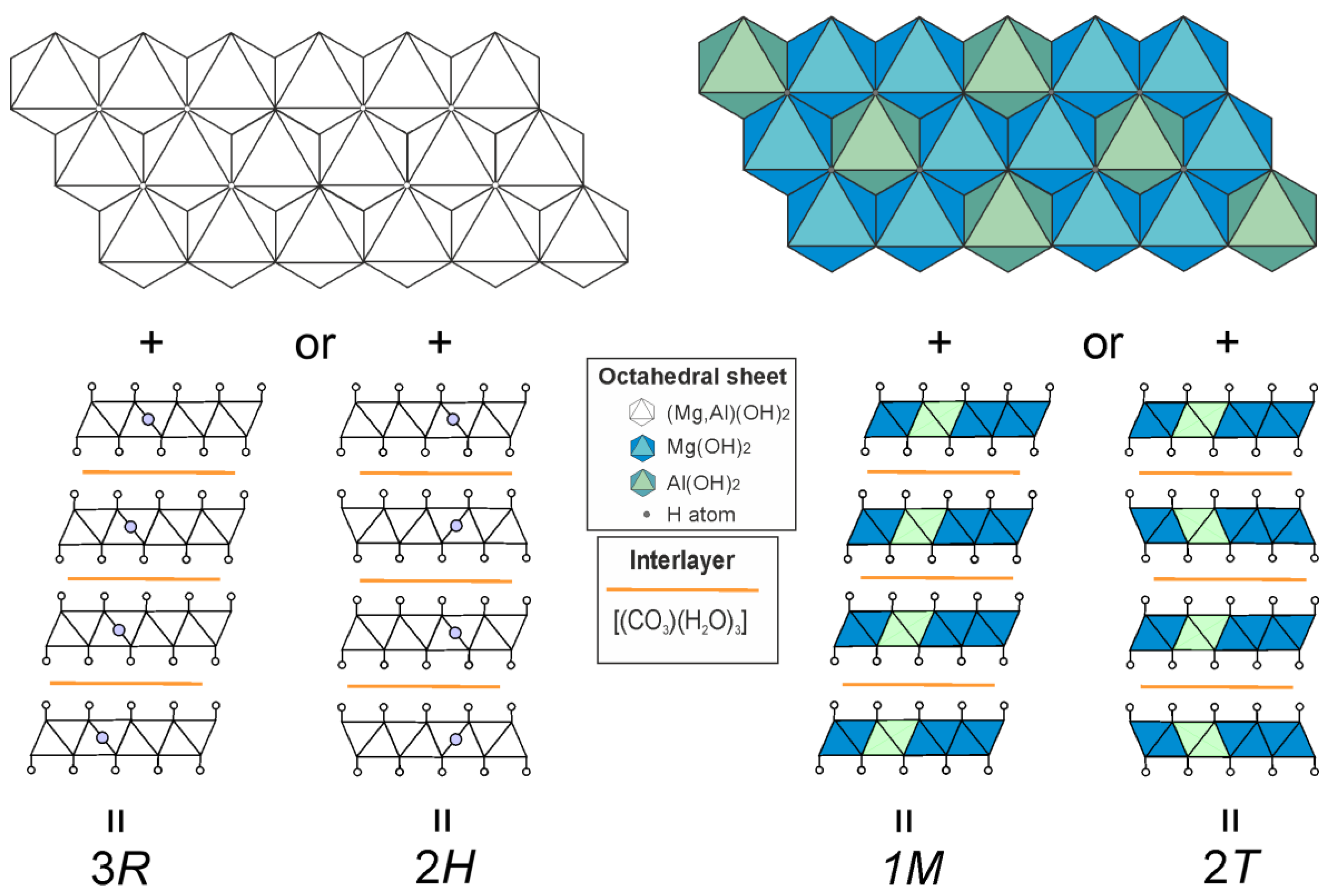

We have studied polytypism of quintinite from the Kovdor alkaline complex (Kola peninsula, Russia), where the polytype character depends upon the following factors: (i) disorder or order of cations within metal-hydroxide layer and (ii) type of layer stacking [Krivovichev et al., 2010a,b; Zhitova et al., 2010; Krivovichev et al., 2012a; Zhitova et al., 2018a]. In total, five polytypes of quintinite have been described in Kovdor, among them, 2

H, 2

T, 3

R and 1

M polytypes appear commonly (

Figure 3). In addition, it was shown that the sequence of polytype formation can be described as 2

H → 2

T → 1

M. The polytype 2

T-3

c (or 2

H-3

c in the original version) can be characterized as a cell of 2

T polytype shifted along

z direction producing tripling of the number of layers within the unit cell; this polytype has been observed in one sample only. Later the study of “hydrotalcite” from two localities in Ural Mountains (Russia), Ural emerald mines (Malyshevskoe or former Mariinskoe deposit) [Zhitova et al., 2018b] and Bazhenovskoe Chrysotile–Asbestos deposit [Krivovichev et al., 2012b], demonstrated that Ural samples are in fact quintinite-1

M (previously identified as hydrotalcite) isotypic to the Kovdor quintinite-1

M. Recently quintinite-1

M has been described from the Mount Mather Creek, British Columbia together with the 3

T(?) polytype that possess some residual reflections [Piillonen et al., 2022].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Two samples from the Jacupiranga alkaline complex (Cajati, São Paulo, Brazil) labelled as “manasseite” have been investigated from the following sources: (a) the systematic collection of the Fersman Mineralogical Museum of the Russian Academy of Science (Moscow, Russia) stored under catalog number 91,002 and (b) from the collection of Smithsonian Institution (National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., USA) stored under catalog number C7029.

Originally quintinite has been described in Jacupiranga as “manasseite” (hexagonal form of hydrotalcite that is currently discredited) [Menezes and Martins, 1984]. Quintinite and manasseite/hydrotalcite have a confusing history {see hydrotalcite vs. quintinite description in Snarum (Norway) by [Mills et al., 2016; Raade, 2013; Zhitova et al., 2019a] of their description because both are Mg-Al-CO3 minerals with the different Mg:Al ratios: 2:1 (quintinite) and 3:1 (hydrotalcite and formerly “manasseite”). Then the crystal structure of quintinite from the Jacupiranga mine was studied [Arakcheeva et al., 1996], it was stated that the mineral is a potentially new mineral species from the ‘hydrotalcite-manasseite group’ that has previously been described as “manasseite”. Paying attention to the synchronism of this work on structure refinement (1996) [Arakcheeva et al., 1996] with the description of a new mineral – quintinite (1997) [Chao and Gault, 1997] and the subsequent citation of this structural work in the first description of quintinite, it is clear that the mineral studied by Arakcheeva et al. [1996] was in fact quintinite. At the time of the crystal structure description, the name of the quintinite has not yet been approved by the Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification therefore not mentioned in the text. In the most recent study of the Jacupiranga minerals [Oliveira and Sant`Agostino, 2020], this mineral is described as quintinite. In Jacupiranga, quintinite was found in carbonatite rocks [Menezes and Martins, 1984] and considered as late-stage hydrothermal mineral.

2.2. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis was carried out for the quintinite samples 91,002 and C7029 using a Bruker Smart Apex diffractometer (X-ray diffraction Resource Center, St. Petersburg State University), Mo

Kα radiation, operated at 50 kV and 40 mA, equipped with a CCD area detector, more details on data collection are given in

Table 1. The unit-cell parameters were refined by least-squares methods. The data were processed using the

P-3

c1 space group. During data process we first successfully processed single-crystal X-ray diffraction data and refined crystal structure in the

P6

3/

mcm space group as the most probable option suggested by CrysAlis Software [Rigaku Oxford Diffraction, 2015] (this space group was used for the refinement of chlormagaluminite structure [Zhitova et al., 2019]). However, this led to a large number of unaccounted for reflections, as a result of which we decided to use the P-3c1 space group previously used for quintinite [Zhitova et al., 2018].

The structure was solved and refined using the ShelX program package [Sheldrick, 2015] incorporated into the Olex2 software shell [Dolomanov et al., 2009], to R1 = 0.053/0.066 for 320/424 independent reflections with I ≥ 2σ(I) for samples 91,002 and C7029.

The positions of Mg, Al and oxygen of the metal-hydroxide layer were located by direct methods and refined anisotropically (

Table S2). The interlayer species (O and C) and hydrogen atoms of metal-hydroxide layer were located from the inspection of difference-Fourier maps and refined isotropically. Site occupancies of the Mg, Al and O sites of the metal-hydroxide layer were found close to 100 % and fixed. Site occupancies of the interlayer atoms were refined for O atoms and fixed for C atoms. The main crystallographic characteristics and structure refinement parameters are listed in

Table 1.

2.3. Powder X-ray diffraction

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) data were collected for sample 91,002 by means of a Rigaku R-Axis Rapid II single-crystal diffractometer using Debye-Scherrer geometry (d = 127.4 mm). The diffractometer is equipped with a rotating anode (CoKα, λ = 1.79026, voltage = 40 kV and current = 15 mA), microfocus optics and a cylindrical image plate detector. The data were converted using osc2xrd program [Britvin et al., 2017].

The unit-cell parameters were refined by the Pawley method using Topas 4.2 [Bruker, 2009], with the hexagonal structure model, space group P-3c1, with the starting unit-cell parameters of the sample 91,002 reported herein. The refinement was based on the reflections in the 2θ region 10–60º. The indexing of the pattern and refinement of the unit-cell parameters were done with the fixed atom coordinates, site scattering and isotropic displacement parameters. Neutral scattering factors were used for all atoms. The background was modelled using a Chebyshev polynomial approximation of the 14th order. The peak profile was described using the fundamental parameters approach. Refinement of preferred orientation parameters confirmed the presence of significant preferred orientation along the [001] direction.

3. Results

3.1. Crystal structure solution and refinement

The collected singe-crystal X-ray diffraction data were processed in the

P-3

c1 space group,

a = 5.246/5.298 Å,

c = 15.110/15.199 Å for the samples 91002/C7029. Eight atomic positions were located from the structure solution and refinement for each sample (sites labelled): Mg, Al, O1 and H1 are part of metal-hydroxide layer (or octahedral sheet) and fully occupied (

Table 2).

The Mg and Al sites are ordered according to the

×

superstructure; each of the metal sites is coordinated by six protonated oxygen atoms with the average <Mg–O> and <Al–O> bond distances being in the ranges 2.022–2.053 Å and 1.974–1.978 Å, respectively (

Table 3). The other four sites C1, C2, O2 and O3 are at the interlayer level and correspond to the low-occupied sites of statistically disordered (CO

3)

2- groups and (H

2O)

0 molecules. All interlayers are identical and consist of both (CO

3)

2- groups and (H

2O)

0 molecules in one layer.

The O1–H1 bond is nearly perpendicular to the plane of the octahedral sheet; the bond distance is 0.82/0.91 Å for the samples 91002/C7029 (

Table 4). The O1 atom acts as a donor (

D), while the interlayer O2 and O3 atoms are acceptors (

A) of hydrogen bonding. The H

…A bond distance is almost two times longer than the

D–H distance (

Table 4).

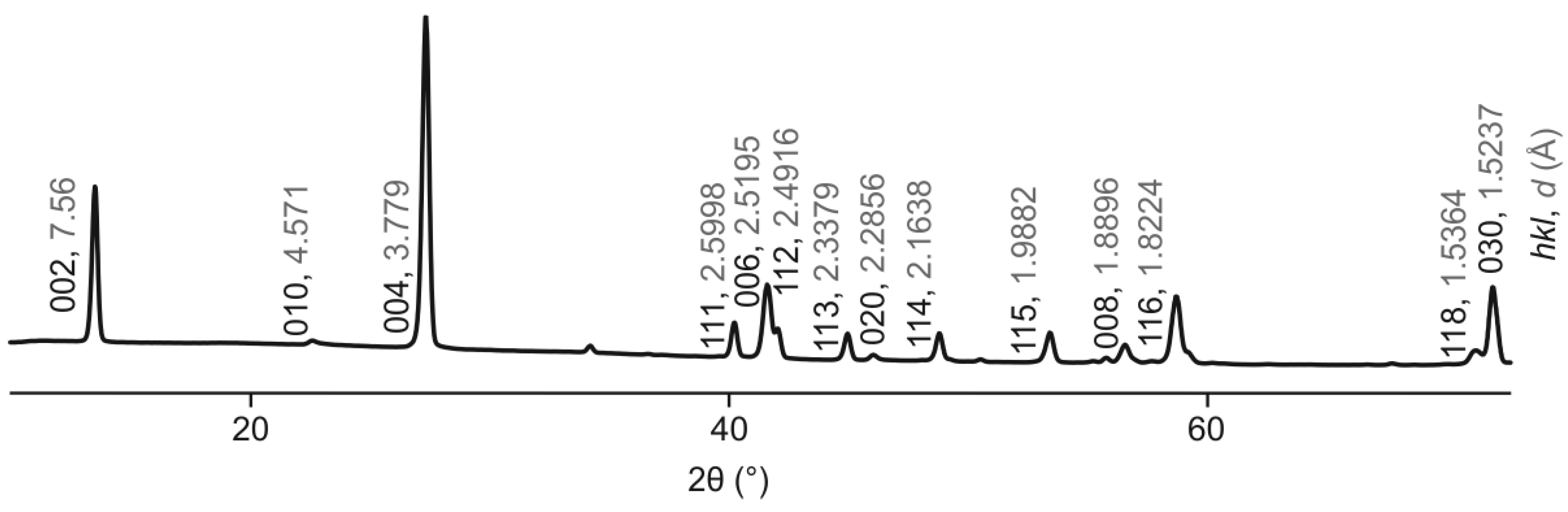

3.2. Powder X-ray diffraction

The main set of reflections of the powder X-ray diffraction pattern (

Figure 1) corresponds to the classic (for LDHs) 2

H polytype (

Table S1). The low-intensity superstructure reflection indicative of the Mg and Al ordering according to the

×

superstructure is observed at

d = 4.57 Å and indexed (

hkl) as 010. Another characteristic feature of quintinite powder X-ray diffraction pattern is the

d-value of 7.56 Å that agrees well with the previous crystal chemical studies of quintinite [Zhitova et al., 2016].

Figure 4.

Indexed powder X-ray diffraction pattern of quintinite from Jacupiranga, sample 91,002 {space group P-3c1; lattice parameters from powder X-ray diffraction data: a = 5.2783(3) Å, c = 15.1171(16) Å, V = 364.74(6) Å3}.

Figure 4.

Indexed powder X-ray diffraction pattern of quintinite from Jacupiranga, sample 91,002 {space group P-3c1; lattice parameters from powder X-ray diffraction data: a = 5.2783(3) Å, c = 15.1171(16) Å, V = 364.74(6) Å3}.

4. Discussion

In this work, using X-ray diffraction analysis, it is shown that quintinite from Jacupiranga is characterized by a hexagonal type of layer stacking, a superstructure according to the Mg and Al ordering by × pattern, and identical interlayers composed of disordered (H2O)0 molecules and (CO3)2- groups at the same level in one gallery. This polytype is designated as 2T according to the Ramsdell notation [Guinier et al., 1984]. Topologically, quintinite-2T from Jacupiranga is identical to quintinite-2T from Kovdor alkaline complex [Zhitova et al., 2018] and is the second confirmed finding of quintinite-2T in the world. It should be noted that, due to the high degree of disorder of the interlayer components, the positions of localized interlayer C and O atoms may differ from sample to sample, but the electron density distribution maps at the interlayer level are identical. The same refer to the space group selection, i.e. potential polytypes with structures refined in space groups P-3c1 or P63/mcm with identical crystal chemical features should not be taken as separate polytypes (see details in section 2.2).

Previously, we assumed [Zhitova et al., 2018] that the structure obtained for quintinite from the Jacupiranga [Arakcheeva et al., 1996] with stratified interlayer is not entirely correct from the crystal-chemical point of view, since, probably, the "carbonate" and "water" interlayers should have had different heights of the interlayer gallery, which was not observed. It should also be noted here that such a division into two types of interlayers in the previous work was most likely due to the fact that not all electron density peaks at the interlayer level were detected, since their intensity can be very low, on the order of 1

ē. A similar problem is typical for earlier refinements of many LDH minerals, and is a consequence of the (apparently) insufficient accuracy of the equipment of that time. Although we had no opportunity to examine the same quintinite crystal as earlier researchers [Arakcheeva et al., 1996], we suggest that quintinite does not form structures with stratified interlayers. We also suggest that quintinite is characterized by four main polytypes (

Figure 3), one of which is 2

T that is described in this work. We believe that this is a rather important assumption, since experimentally obtained crystal structures often become the basis for the Rietveld refinements or computer simulation. Unfortunately, sometimes in the literature it is possible to observe crystal structures that are unrealistic from a crystal chemical point of view, in which, for example, H

2O molecules and carbonate groups are located in the same interlayer gallery at different levels.

The presence of M2+ and M3+ cation ordering within metal-hydroxide layers that form a × superstructure is manifested in the powder X-ray diffraction pattern by the presence of the superstructure reflection with d ~ 4.57 Å (indexed as 010 in case of 2T polytype). The same superstructure reflection was observed for chlormagaluminite [Zhitova et al., 2019b]. The powder X-ray diffraction patterns for both quintinite and chlormagaluminite were recorded using Gandolfi technique reducing the effect of the sample preferred orientation along (001). The presence of such a reflection is indicative of the M2+ and M3+ cation ordering that should further be combined with the layer stacking sequence. However, the absence of this reflection, especially taking into account its low intensity (i.e. difficulty of detection), should not been taken as an indication of the absence of cation ordering.

An indirect criterion for the topological identity of quintinites from different natural environments and places can be the value of the interlayer distance (

d-value) of quintinite, which is ~ 7.56 Å (

Table 5) (or slightly above if the Mg:Al ratio is higher than the ideal of 2:1 [Zhitova et al., 2016]). Quintinite findings from different localities around the globe and different genetic types are characterized by the steady

d00n-value, despite some obvious difference in physicochemical and thermodynamic conditions of their formation (

Table 5). Thus, we believe that the internal structure of natural samples indicates certain principles for the construction of metal-hydroxyl layers and interlayers, as well as their interactions of the crystal structure, and which can be transferred to artificially obtained compounds. In particular, we emphasize that, under room conditions, we do not observe fundamental changes in the content of interlayer H

2O molecules and related structural transformations of quintinite.

Finally, we would like to emphasize that, according to the available structural data, for quintinites from different findings and differing in geological position, that is, the conditions of formation, the crystal structures are built in the same way: (i) the structure of the interlayers is the same, (ii) the structure of the octahedral sheet differs only in the registered ordering of Mg and Al or without registered ordering, i.e. "disordered" (although the disorder may be apparent due to the incorporation of impurities) and (iii) different types of stacking of layers.

5. Conclusions

In this work, we have refined the crystal structure of Jacupiranga quintinite and have shown that, from a structural point of view, it is identical to the 2T polytype of Kovdor quintinite and consists of metal hydroxide layers [Mg4Al2(OH)12]2+ and the [(CO3)(H2O)3]2- interlayers. The Mg and Al ordering according to the × superstructure is detected by single-crystal X-ray diffraction and powder X-ray diffraction by the appearance of additional (to 2H pattern) low-intensity superstructure reflections, including the reflection with d010 ~ 4.57 Å in the powder pattern. Combining our data and literature data, as well as the information on the d00n-values of quintinites (d00n ~ 7.56 Å) of various genetic types and localities, we conclude that the structure of quintinite obeys certain crystal chemical principles and is sustained in the light of layer-interlayer interactions and construction of octahedral sheets and interlayers. We consider it highly probable that quintinite polytypes already known from the Kovdor alkaline complex can be found in other localities, as shown in the example of quintinite from the Jacupiranga alkaline complex. In addition, we also hope that a more detailed history of the description of quintinite from Jacupiranga will lead to the correct definition of this mineral, which will help streamline the literature data on the description of hydrotalcite and quintinite.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Powder X-ray diffraction data for quintinite sample 91002; Table S2: Anisotropic displacement parameters (Å2) for quintinite samples 91002 and C7029.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, ESZ and SVK; methodology, ESZ, AAZ and SVK; software, ESZ, RMS, AAZ, SVK; validation, ESZ, RMS, AAZ, SVK; formal analysis, ESZ, RMS; investigation, ESZ, RMS, AAZ, SVK; resources, SVK; data curation, ESZ, AAZ; writing—original draft preparation, ESZ, RMS, SVK; writing—review and editing, ESZ, RMS, AAZ, SVK; visualization, ESZ; project administration, ESZ; funding acquisition, ESZ. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Russian Science Foundation, grant number 22-77-10036. The APC was funded by co-authors ESZ and AAZ.

Data Availability Statement

The crystallographic information files (cif) has been deposited via the joint Cambridge Crystal Data Centre CCDC/FIZ Karlsruhe deposition service, the deposition numbers are CSD 2260275 for sample 91002 and CSD 2260276 for sample C7029.

Acknowledgments

The technical support of St. Petersburg State University Resource Centers “XRD” is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Fersman Mineralogical Museum (Dmitry Belakovsky) and Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (Jeffrey Post) for providing the samples for research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mills, S.J.; Christy, A.G.; Génin, J.M.; Kameda, T.; Colombo, F. Nomenclature of the hydrotalcite supergroup: natural layered double hydroxides. Mineral. Mag. 2012, 76(5), 1289-1336. [CrossRef]

- Rives, V. Layered double hydroxides: present and future. Nova Science Publishers: New York, USA, 2001; pp. 1–439.

- Duan, X.; Evans, D. G. Layered double hydroxides. Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2006; pp. 1–87. [CrossRef]

- Aminoff, G.; Broome, B. Contributions to the mineralogy of Långban. III. Contributions to the knowledge of the mineral pyroaurite. K. Sven. vetensk. akad. handl. 1931, 9, 23–48.

- Bukhtiyarova, M. V. A review on effect of synthesis conditions on the formation of layered double hydroxides. J. Solid State Chem. 2019, 269, 494-506. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J., Wang, Q., O'Hare, D.; Sun, L. Preparation of two dimensional layered double hydroxide nanosheets and their applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46(19), 5950-5974. [CrossRef]

- Kameliya, J.; Verma, A.; Dutta, P.; Arora, C.; Vyas, S.; Varma, R.S. Layered Double Hydroxide Materials: A Review on Their Preparation, Characterization, and Applications. Inorganics 2023, 11, 121. [CrossRef]

- Rius, J.; Allmann, R. The superstructure of the double layer mineral wermlandite [Mg7(Al0.57,Fe3+0.43)2(OH)18]2+[(Ca0.6,Mg0.4)(SO4)2(H2O)12]2-. Z. fur Krist. 1984, 168, 133-144. [CrossRef]

- Zhitova, E.S.; Chukanov, N.V.; Jonsson, E.; Pekov, I.V.; Belakovskiy, D.I.; Vigasina, M.F.; Zubkova, N.V.; Van K.V.; Britvin, S. N. Erssonite, CaMg7Fe3+2(OH)18(SO4)2⋅12H2O, a new hydrotalcite-supergroup mineral from Långban, Sweden. Mineral. Mag. 2021, 85(5), 817-826. [CrossRef]

- Huminicki, D.M.C.; Hawthorne, F.C. The crystal structure of nikischerite, NaFe62+Al3(SO4)2(OH)18(H2O)12, a mineral of the shigaite group. Can. Mineral. 2003, 41, 79–82. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.A.; Hawthorne, F.C. The crystal structure of shigaite, [AlMn22+(OH)6]3(SO4)2Na(H2O)6(H2O)6, a hydrotalcite group mineral. Can. Mineral. 1996, 34, 91-97.

- Sotiles, A.R.; Gomez, N.A.G.; Santos, M.P.; Grassi, M.T.; Wypych, F. Synthesis, characterization, thermal behavior and exchange reactions of new phases of layered double hydroxides with the chemical composition [M+26Al3(OH)18(SO4)2]. (A(H2O)6).6H2O (M+2 = Co, Ni; A = Li+, Na+, K+). Appl. Clay Sci. 2019, 181, 105217. [CrossRef]

- Sotiles, A.R.; Baika, L.M.; Grassi, M.T.; Wypych, F. Cation exchange reactions in layered double hydroxides intercalated with sulfate and alkali cations (A(H2O)6)[M+26Al3(OH)18(SO4)2].6H2O (M+2 = Mn, Mg, Zn, A+ = Li, Na, K). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141(1), 531–540. [CrossRef]

- Sotiles, A.R.; Wypych, F. Synthesis and topotactic exchange reactions of new layered double hydroxides intercalated with ammonium/sulfate. Solid State Sci. 2020, 106, 106304. [CrossRef]

- Serna, C.J.; Rendon, J.L.; Iglesias, J.E. Crystal-chemical study of layered [Al2Li(OH)6]+X-·nH2O. Clay Clay Miner. 1982, 30(3), 180–184. [CrossRef]

- Sissoko, I.; Iyagba, E.T.; Sahai, I.; Biloen, P. Anion intercalation and exchange in Al(OH)3– derived compounds. J. Solid State Chem. 1985, 60, 283–288. [CrossRef]

- Karcz, R.; Napruszewska, B.D.; Walczyk, A.; Kryściak-Czerwenka, J.; Duraczyńska, D.; Płaziński, W.; Serwicka, E.M. Comparative Physicochemical and Catalytic Study of Nanocrystalline Mg-Al Hydrotalcites Precipitated with Inorganic and Organic Bases. Nanomaterials, 2022, 12(16), 2775.

- Karcz, R.; Napruszewska, B.D.; Michalik, A.; Kryściak-Czerwenka, J.; Duraczyńska, D.; Serwicka, E.M. Fine Crystalline Mg-Al Hydrotalcites as Catalysts for Baeyer-Villiger Oxidation of Cyclohexanone with H2O2. Catalysts, 2021, 11(12), 1493.

- Yin, X.; Hua, Y.; Gao, Z. Two-Dimensional Materials for High-Performance Oxygen Evolution Reaction: Fundamentals, Recent Progress, and Improving Strategies. Renewables, 2023, 1-37. [CrossRef]

- Leão, A.D.; Oliveira, V.V.; Marinho, F.A.; Wanderley, A.G.; Aguiar, J.S.; Silva, T.G.; Soare, M.F.R.; Soares-Sobrinho, J.L. Hybrid systems of glibenclamide and layered double hydroxides for solubility enhancement for the treatment of diabetes mellitus II. Appl. Clay Sci. 2019, 181, 105218. [CrossRef]

- Francius, G.; André, E.; Soulé, S.; Merlin, C.; Carteret, C. Layered Double Hydroxides (LDH) as nanocarriers for antimicrobial chemotherapy: From formulation to targeted applications. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 293, 126965. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, T.H.; Lee, J.H.; Park, Y.A.; Kang, Y. J.; Ji, H. G. Porous nanocomposite of layered double hydroxide nanosheet and chitosan biopolymer for cosmetic carrier application. Appl. Clay Sci. 2021, 205, 106067. [CrossRef]

- Zaghloul, A.; Benhiti, R.; Ichou, A.A.; Carja, G.; Soudani, A.; Zerbet, M.; Sinan, F.; Chiban, M. Characterization and application of MgAl layered double hydroxide for methyl orange removal from aqueous solution. Mater. Today 2021, 37, 3793-3797. [CrossRef]

- Grégoire, B.; Bantignies, J.L.; Le-Parc, R.; Prélot, B.; Zajac, J.; Layrac, G.; Tichit D.; Martin-Gassin, G. Multiscale mechanistic study of the adsorption of methyl orange on the external surface of layered double hydroxide. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123(36), 22212-22220. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Sheng, G.; Hu, J.; Chen, C.; Wang, X. The adsorption of Pb (II) on Mg2Al layered double hydroxide. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 171(1), 167-174. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Kameda, T.; Saito, Y.; Kumagai, S.; Yoshioka, T. Investigation of the mechanism of Cu (II) removal using Mg-Al layered double hydroxide intercalated with carbonate: Equilibrium and pH studies and solid-state analyses. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2021, 132, 108839. [CrossRef]

- Nestroinaia, O.V.; Ryltsova, I.G.; Yaprintsev, M.N.; Nakisko, E.Y.; Seliverstov, E.S.; Lebedeva, O.E. Sorption of Congo Red anionic dye on natural hydrotalcite and stichtite: kinetics and equilibrium. Clay Miner., 2022, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, X.J.; Jie, Y.; Song, H.T.; Xu, X.Y.; Lu H.; Yan, H. Theoretical Study on the Mechanism of Removing Harmful Anions from Soil Via Mg2al Layered Double Hydroxide as Stabilizer. Available at SSRN 4263653. [CrossRef]

- Ke, X.; Bernal, S. A.; Provis, J. L. Uptake of chloride and carbonate by Mg-Al and Ca-Al layered double hydroxides in simulated pore solutions of alkali-activated slag cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 2017, 100, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Sakai, M.; Imagawa, H.; Baba, N. Layered-double-hydroxide-based Ni catalyst for CO2 capture and methanation. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 2022, 647, 118904. [CrossRef]

- Zhitova, E.S.; Sheveleva, R.M.; Kasatkin, A.V.; Zolotarev, A.A.; Bocharov, V.N.; Kupchinenko, A.N.; Belakovsky, D.I. Crystal structure of hydrotalcite group mineral – desautelsite, Mg6MnIII2(OH)16(CO3)·4H2O, and relationship between cation size and in-plane unit cell parameter. Symmetry 2023. Accepted for publication. [CrossRef]

- Zhitova, E.S.; Krivovichev, S.V.; Pekov, I.V.; Greenwell, H.C. Crystal chemistry of natural layered double hydroxides. 5. Single-crystal structure refinement of hydrotalcite, [Mg6Al2(OH)16](CO3)(H2O)4. Mineral. Mag. 2019, 83(2), 269-280. [CrossRef]

- Zhitova, E.S.; Krivovichev, S.V.; Pekov, I.V.; Yapaskurt, V.O. Crystal chemistry of chlormagaluminite, Mg4Al2(OH)12Cl2(H2O)2, a natural layered double hydroxide. Minerals 2019, 9(4), 221. [CrossRef]

- Zhitova, E.S.; Pekov, I.V.; Chaikovskiy, I.I.; Chirkova, E.P.; Yapaskurt, V.O.; Bychkova, Y.V., Belakovsky, D.I.; Chukanov, N.V.; Zubkova, N.V.; Krivovichev, S.V.; Bocharov, V. N. Dritsite, Li2Al4(OH)12Cl2·3H2O, a new gibbsite-based hydrotalcite supergroup mineral. Minerals 2019, 9(8), 492. [CrossRef]

- Britto, S.; Thomas, G.S.; Kamath, P.V.; Kannan, S. Polymorphism and structural disorder in the carbonate containing layered double hydroxide of Li with Al. J. Phys. Chem. 2008, 112, 9510–9515. [CrossRef]

- Britto, S.; Kamath, P.V. Structure of Bayerite-Based Lithium–Aluminum Layered Double Hydroxides (LDHs): Observation of Monoclinic Symmetry. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 11646–11654. [CrossRef]

- Britto, S.; Kamath, P.V. Polytypism in the lithium–aluminum layered double hydroxides: the [LiAl2(OH)6]+ layer as a structural synthon. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 5619–5627.

- Krivovichev, S.V.; Yakovenchuk, V.N.; Zhitova, E.S.; Zolotarev, A.A.; Pakhomovsky, Y.A.; Ivanyuk, G.Y. Crystal chemistry of natural layered double hydroxides. I. Quintinite-2H-3 c from the Kovdor alkaline massif, Kola peninsula, Russia. Mineral. Mag. 2010, 74(5), 821-832. [CrossRef]

- Krivovichev, S.V.; Yakovenchuk, V.N.; Zhitova, E.S.; Zolotarev, A.A.; Pakhomovsky, Y.A.; Ivanyuk, G.Y. Crystal chemistry of natural layered double hydroxides. 2. Quintinite-1M: First evidence of a monoclinic polytype in M2+-M3+ layered double hydroxides. Mineral. Mag. 2010, 74(5), 833-840.

- Krivovichev, S.V.; Yakovenchuk, V.N.; Zhitova, E.S. Natural double layered hydroxides: structure, chemistry, and information storage capacity. In Minerals as advanced materials II; Krivovichev S.V., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 87–102. [CrossRef]

- Zhitova, E.S.; Yakovenchuk, V.N.; Krivovichev, S.V.; Zolotarev, A.A.; Pakhomovsky, Y.A.; Ivanyuk, G.Y. Crystal chemistry of natural layered double hydroxides. 3. The crystal structure of Mg, Al-disordered quintinite-2H. Mineral. Mag. 2010, 74(5), 841-848. [CrossRef]

- Zhitova, E.S.; Krivovichev, S.V.; Yakovenchuk, V.N.; Ivanyuk, G.Y.; Pakhomovsky, Y.A., Mikhailova, J.A. Crystal chemistry of natural layered double hydroxides: 4. Crystal structures and evolution of structural complexity of quintinite polytypes from the Kovdor alkaline-ultrabasic massif, Kola peninsula, Russia. Mineral. Mag. 2018, 82(2), 329-346. [CrossRef]

- Arakcheeva, A.V.; Pushcharovskii, D.Y.; Rastsvetaeva, R.K.; Atencio, D.; Lubman, G.U. Crystal structure and comparative crystal chemistry of Al2Mg4(OH)12(CO3)·3H2O, a new mineral from the hydrotalcite-manasseite group. Crystallogr. Rep. 1996, 41(6), 972-981.

- Chao, G.Y.; Gault, R.A. Quintinite-2H, quintinite-3T, charmarite-2H, charmarite-3T and caresite-3T, a new group of carbonate minerals related to the hydrotalcite-manasseite group. Can. Mineral. 1997, 35(6), 1541-1549.

- Zhitova, E.S.; Popov, M.P.; Krivovichev, S.V.; Zaitsev, A.N.; Vlasenko, N.S. Quintinite-1M from the Mariinsky Deposit, Ural Emerald Mines, Central Urals, Russia. Geol. Ore Depos. 2018, 59(8), 745–751. [CrossRef]

- Krivovichev, S.V.; Antonov, A.A.; Zhitova, E.S.; Zolotarev, A.A.; Krivovichev, V.G.; Yakovenchuk, V.N. Quintinite-1M from Bazhenovskoe deposit (Middle Ural, Russia): crystal structure and properties. Vestnik Saint Petersburg Univ. Earth Sci. 2012, 7, 3–9 (in Russian).

- Piilonen, P.; Poirier, G.; Rowe, R.; Mitchell, R.; Robak, C. Mount Mather Creek, British Columbia – a new sodalite-bearing carbohydrothermal breccia deposit including a new Canadian occurrence for the rare minerals edingtonite and quintinite. Mineral. Mag. 2022, 86(2), 282-306. [CrossRef]

- Menezes, L.A.D.; Martins, J.M. The Jacupiranga mine Sao-Paulo, Brazil. Mineral. Rec. 1984, 15(5), 261-270.

- Alker, A.; Golob, P.; Postl, W.; Waltinger, H. Hydrotalkit, Nordstrandit und Motukoreait vom Stradner Kogel, südlich Gleichenberg, Steiermark. Mitt.-Bl. Abt. Mineral. Landesmuseum Joanneum 1981, 49, 1-13.

- Mills, S.J.; Christy, A.G.; Schmitt, R. The creation of neotypes for hydrotalcite. Mineral. Mag. 2016, 80, 1023-1029. [CrossRef]

- Raade, G. Hydrotalcite and quintinite from Dypingdal, snarum, Buskerud, Norway. Norsk Bergverksmuseum Skrifter 2013, 50, 55-57.

- Oliveira, S.B.D.; Sant'Agostino, L.M. Lithogeochemistry and 3D geological modeling of the apatite-bearing Mesquita Sampaio beforsite, Jacupiranga alkaline complex, Brazil. Brazil. J. Geol. 2020, 50(2), e20190071.

- CrysAlisPro Software System, version 1.171.38.46; Rigaku Oxford Diffraction: Oxford, UK, 2015.

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. A 2015, 71, 3–8. [CrossRef]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42(2), 339-341.

- Britvin, S.N.; Dolivo-Dobrovolsky, D.V.; Krzhizhanovskaya, M.G. Software for processing of X-ray powder diffraction data obtained from the curved image plate detector of Rigaku RAXIS Rapid II diffractometer. Zapiski RMO, 2017, 146(3), 104–107 (in Russian).

-

TOPAS V4.2: General Profile and Structure Analysis Software for Powder Diffraction Data. Bruker-AXS: Karlsruhe, Germany, 2009.

- Guinier, A.; Bokij, G.B.; Boll-Dornberger, K.; Cowley, J.M.; Ďurovič, S.; Jagodzinski, H.; Krishna, P.; de Woff, P.M.; Zvyagin, B.B; Cox, D.E.; Goodman, P.; Hahn, Th.; Kuchitsu, K.; Abrahams, S.C. Nomenclature of polytype structures. Report of the International Union of Crystallography Ad hoc Committee on the nomenclature of disordered, modulated and polytype structures. Acta Crystallogr. A 1984, 40(4), 399-404.

- Zhitova, E.S.; Krivovichev, S.V.; Pekov, I.V.; Yakovenchuk, V.N.; Pakhomovsky, Y.A. Correlation between the d-value and the M2+: M3+ cation ratio in Mg–Al–CO3 layered double hydroxides. Appl. Clay Sci. 2016, 130, 2-11. [CrossRef]

- Černý, P. Hydrotalcite z Véžná na zapadni Morave. Acta Musei Moraviae 1963, XLVII, 23-30.

- Allmann, R; Jespen H.P. Die struktur des hydrotalkits. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Monatshefte 1969, 544-551.

- Drits, V.A.; Sokolova, T.N.; Sokolova, G.V.; Cherkashin, V.I. New members of the hydrotalcite - manasseite group. Clays Clay Miner. 1987, 35, 401-417.

- Lisitsina, V.A.; Drits, V.A.; Sokolova, T.N. New complex of secondary minerals-products of low temperature transformations of rocks, covering basalts of Atlantic Ocean underwater mountains. Lithol. Miner. Resour. 1985, 6, 20-39.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).