1. Introduction

The nasopharyngeal closure function is known to be crucially involved in articulatory disorders that occur after palatoplasty in patients with cleft palate, and may be involved in both the morphology and movement of articulatory organs, including the palate and tongue [

1]. However, no method has been devised to assess in detail the association between articulatory disorders and the morphology and movement of articulatory organs; therefore, the pathogenesis remains unclear.

The recent development of acoustic wave-based techniques such as the finite element, finite difference, and boundary element methods, has made it possible to visualize and conduct a detailed analysis of the relationship between the morphology of, and sound produced by, a three-dimensional (3D) shape obtained for a 3D model of the vocal tract [

2,

3,

4,

5].

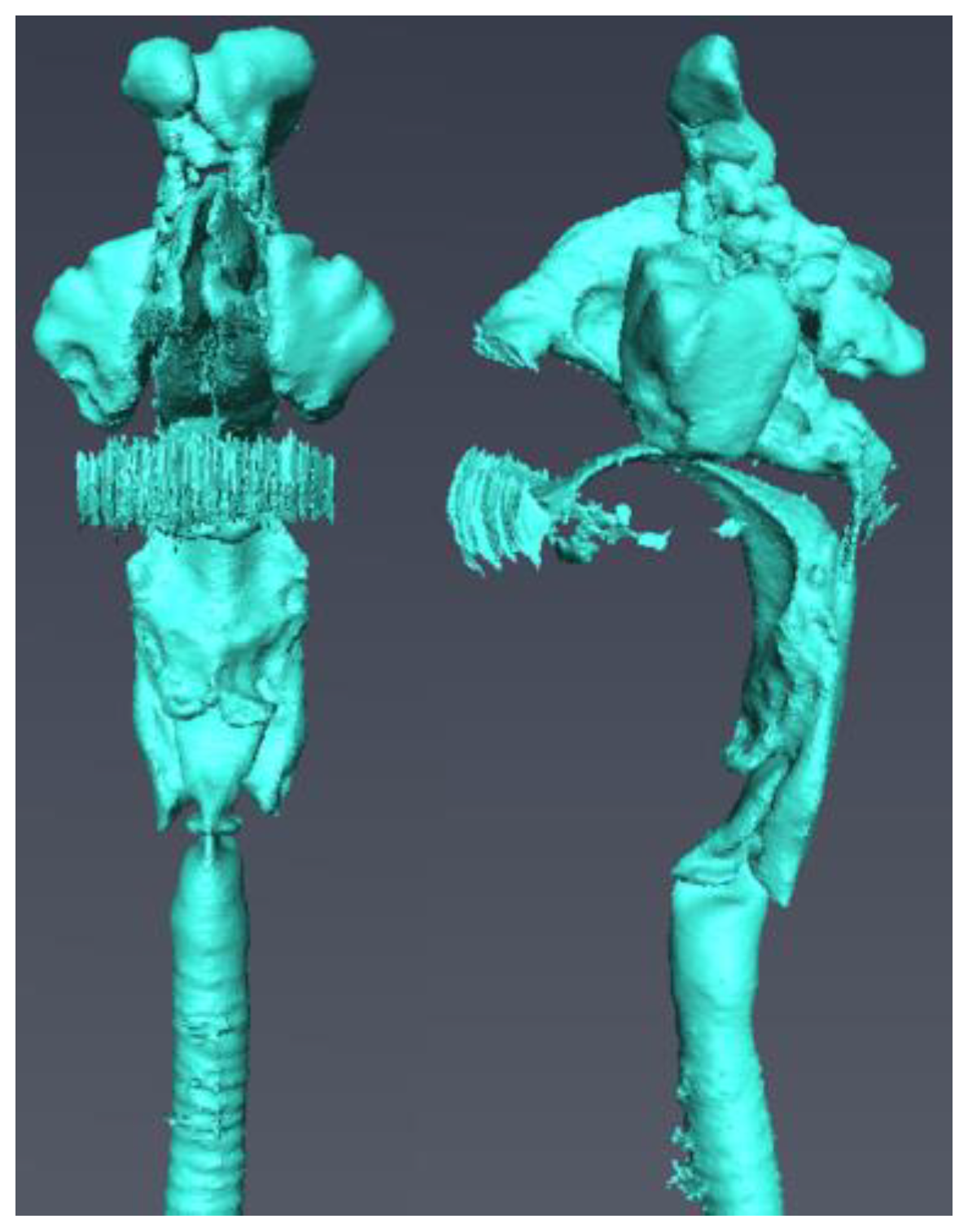

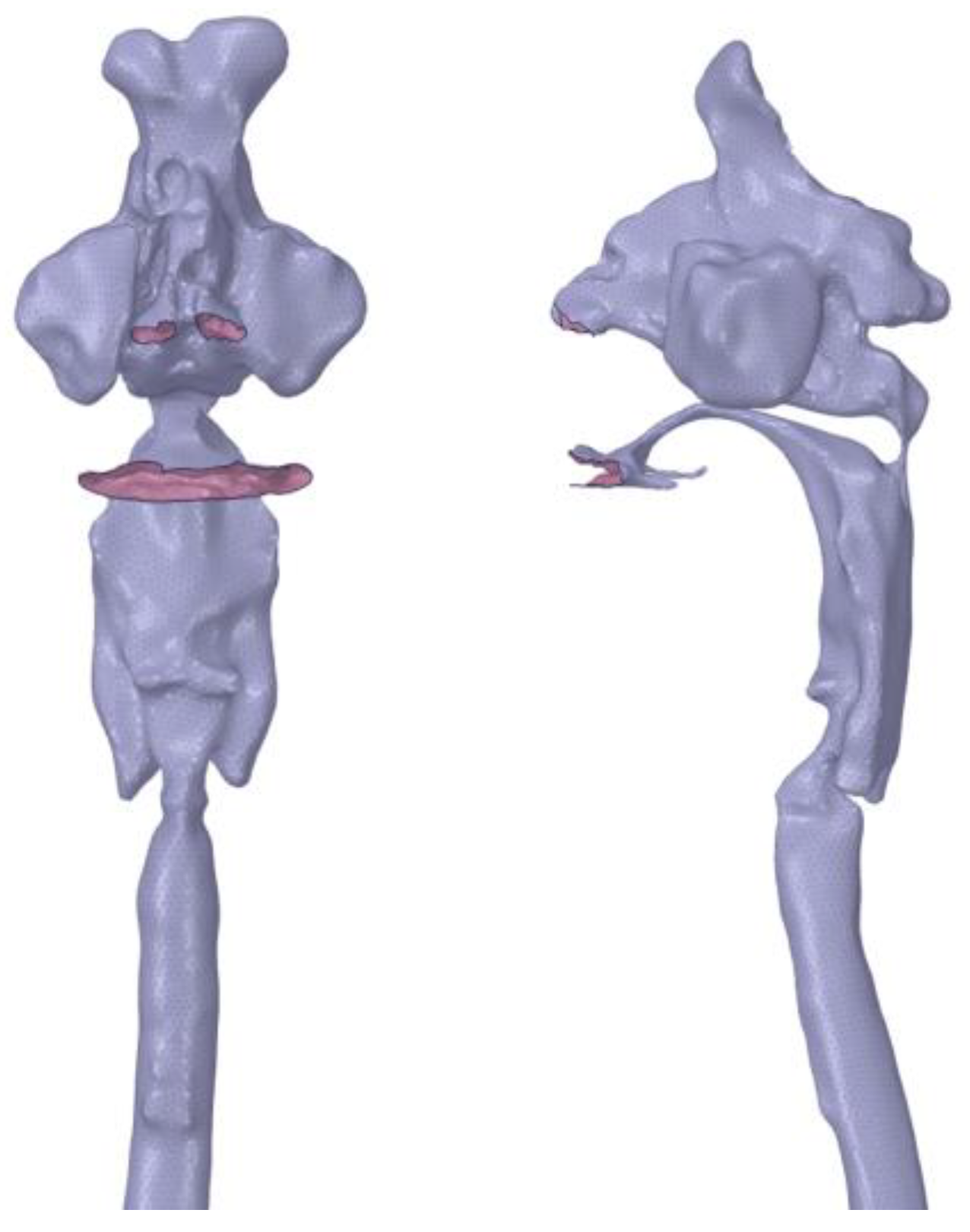

We established a simulation method using computed tomography (CT) data during phonation of /a/ in order to clarify the relationship between the morphology of the articulatory organs and the sounds produced by applying the boundary element method. In a previous study, we verified the accuracy of the simulation method for the Japanese vowel /a/ by applying the boundary element method for a vocal tract model including ranges from the frontal sinus to the trachea. Our results demonstrated that high-precision simulation is possible [

6].

Consequently, the present study was conducted to establish a simulation method for the other vowels. Since /a/ is an open vowel, we aimed to establish a simulation for narrow vowels. Furthermore, the present study investigated the possibility of simulating the front narrow vowel /i/ and the rear narrow vowel /u/, and verified the accuracy of the simulations.

3. Results

Table 1 and

Table 2 show the results of the acoustic simulation of the vocal tract model created from six participants. In all participants, the formant frequencies obtained from the simulation were within the ranges of the frequencies of F1 and F2 for the Japanese vowels /i/ and /u/ reported in the past [

11]. The relative discrimination thresholds of the vowel formant frequencies for /i/ and /u/ against actual voice ranged from 1.1% to 10.2% and from 0.4% to 9.3% for F1, and from 3.9% to 7.5% and from 5.0% to 12.5% for F2, respectively. Several thresholds exceeded 9%, but the relative discrimination thresholds became 9% or less by shortening the virtual cylindrical trachea. Specifically, the relative discrimination thresholds became 7.8% for F1 of /i/ in subject No. 6, 0.6% for F2 of /u/ in subject No. 3 by shortening by 1 cm, and 2.4% for F2 of /u/ in subject No. 2 by shortening by 2 cm.

The acoustic simulation results for various extension lengths of the virtual trachea are shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4. As the length of the virtual trachea shortened, the formant frequencies increased, except for F1 of /i/ in subject No. 1. The standard deviations of F1 and F2 obtained by the acoustic simulation were 2.9–22.1 cm and 43.7–135.2 cm for /i/, and 4.7–31.0 cm and 20.2–101.3 cm for /u/, respectively, when the lengths of the virtual trachea were changed to 10 cm, 11 cm, and 12 cm. The standard deviations with the changes in extension lengths varied considerably.

Three of the six participants had a connection to the nasal cavity at the nasopharynx (i.e., nasal coupling), whereas the remaining three did not (

Table 5). The minimum cross-sectional areas at the nasal coupling for the three participants with nasal coupling are shown in

Table 5. The average cross-sectional areas of /i/ and /u/ were 1.57 and 8.01 mm

2, respectively.

The typical frequency response curves obtained by the acoustic simulation are shown in

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. A peak around 500 Hz was observed for /i/ in subject No. 4 and /u/ in subject No. 1, both of whom had nasal coupling (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Conversely, no peaks around 500 Hz were observed for both /i/ and /u/ in the curves obtained for the models without nasal coupling and with nasal coupling but with the nasal cavity and sinuses removed (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). Therefore, the peak around 500 Hz was considered to be the pole–zero pair because of the nasal coupling (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Pole–zero pairs around 500 Hz caused by nasal coupling were observed between F1 and F2 for both /i/ and /u/ (

Table 6). A further peak was observed at 1000 Hz for /i/ for all participants (

Table 6). The peaks around 1000 Hz were observed in the curves obtained for both models of /i/ without nasal coupling and with nasal coupling but with the nasal cavity and sinuses removed (

Figure 3 and

Figure 5).

Comparing the frequency response curves obtained for the models with nasal coupling and those with the nasal cavity and sinuses removed, the frequencies of F1 for /i/ shifted to the low frequency side, whereas those for /u/ shifted to the high frequency side (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

Table 1.

Formant frequencies simulated from the vocal tract model and calculated from the actual voice of /i/.

Table 1.

Formant frequencies simulated from the vocal tract model and calculated from the actual voice of /i/.

| |

|

|

F1 |

F2 |

| Sex |

Subject No. |

Number of elements |

Simulation value (Hz) |

Actual voice (Hz) |

Discrimination threshold (%) |

Simulation value (Hz) |

Actual voice (Hz) |

Discrimination threshold (%) |

| M |

1 |

28,509 |

356 |

351 |

1.4 |

2196 |

2031 |

7.5 |

| 2 |

11,864 |

365 |

342 |

6.3 |

2204 |

2356 |

6.9 |

| 3 |

11,492 |

317 |

336 |

6.0 |

2347 |

2180 |

7.1 |

| F |

4 |

21,192 |

374 |

370 |

1.1 |

2510 |

2649 |

5.5 |

| 5 |

8361 |

368 |

358 |

2.7 |

2451 |

2579 |

5.2 |

| 6 |

22,419 |

401 |

442 |

10.2 |

2775 |

2882 |

3.9 |

Table 2.

Formant frequencies simulated from the vocal tract model and calculated from the actual voice of /u/.

Table 2.

Formant frequencies simulated from the vocal tract model and calculated from the actual voice of /u/.

| |

|

|

F1 |

F2 |

| Sex |

Subject No. |

Number of elements |

Simulation value (Hz) |

Actual voice (Hz) |

Discrimination threshold (%) |

Simulation value (Hz) |

Actual voice (Hz) |

Discrimination threshold (%) |

| M |

1 |

28,982 |

371 |

364 |

1.9 |

1127 |

1198 |

6.3 |

| 2 |

9905 |

445 |

436 |

2.0 |

1102 |

1222 |

11.0 |

| 3 |

9728 |

381 |

375 |

1.6 |

1121 |

1261 |

12.5 |

| F |

4 |

20,644 |

449 |

447 |

0.4 |

1403 |

1333 |

5.0 |

| 5 |

8653 |

495 |

464 |

6.3 |

1220 |

1292 |

6.0 |

| 6 |

22,151 |

432 |

472 |

9.3 |

2072 |

1906 |

8.0 |

Table 3.

Formant frequencies simulated for /i/ by various extension lengths of the virtual trachea (Hz).

Table 3.

Formant frequencies simulated for /i/ by various extension lengths of the virtual trachea (Hz).

| |

|

F1 |

F2 |

| Sex |

Subject No. |

Length of the virtual trachea |

Length of the virtual trachea |

| 11 cm |

10 cm |

0 cm |

11 cm |

10 cm |

0 cm |

| M |

1 |

387 |

410 |

390 |

2279 |

2364 |

2432 |

| 2 |

369 |

379 |

501 |

2298 |

2342 |

2369 |

| 3 |

317 |

324 |

393 |

2520 |

2663 |

2679 |

| F |

4 |

416 |

420 |

451 |

2663 |

2840 |

3317 |

| 5 |

370 |

375 |

580 |

2608 |

2782 |

3070 |

| 6 |

410 |

429 |

633 |

2860 |

2874 |

3350 |

Table 4.

Formant frequencies simulated for /u/ by various extension lengths of the virtual trachea (Hz).

Table 4.

Formant frequencies simulated for /u/ by various extension lengths of the virtual trachea (Hz).

| |

|

F1 |

F2 |

| Sex |

Subject No. |

Length of the virtual trachea |

Length of the virtual trachea |

| 11 cm |

10 cm |

0 cm |

11 cm |

10 cm |

0 cm |

| M |

1 |

380 |

391 |

404 |

1195 |

1230 |

1749 |

| 2 |

483 |

521 |

597 |

1110 |

1193 |

1960 |

| 3 |

399 |

410 |

519 |

1253 |

1369 |

2451 |

| F |

4 |

439 |

449 |

1061 |

1339 |

1399 |

2041 |

| 5 |

508 |

523 |

725 |

1265 |

1295 |

1850 |

| 6 |

438 |

446 |

753 |

2106 |

2120 |

2160 |

Table 5.

Minimum cross-sectional area at the nasal coupling for /i/ and /u/ (mm2).

Table 5.

Minimum cross-sectional area at the nasal coupling for /i/ and /u/ (mm2).

| Sex |

Subject No. |

/i/ |

/u/ |

| M |

1 |

2.82 |

7.91 |

| F |

4 |

0.45 |

12.01 |

| 6 |

1.44 |

4.12 |

Table 6.

Pole–zero pairs for /i/ and /u/.

Table 6.

Pole–zero pairs for /i/ and /u/.

| |

/i/ |

/u/ |

| Sex |

Subject No. |

Pole–zero 1 (Hz) |

Pole–zero 2 (Hz) |

Pole–zero (Hz) |

| M |

1 |

411 ; 534 |

1037 ; 1209 |

462 ; 492 |

| 2 |

- |

944 ; 1175 |

- |

| 3 |

- |

936 ; 1011 |

- |

| F |

4 |

406 ; 486 |

1206 ; 1240 |

613 ; 654 |

| 5 |

- |

1100 ; 1251 |

- |

| 6 |

449 ; 518 |

1143 ; 1213 |

531 ; 587 |

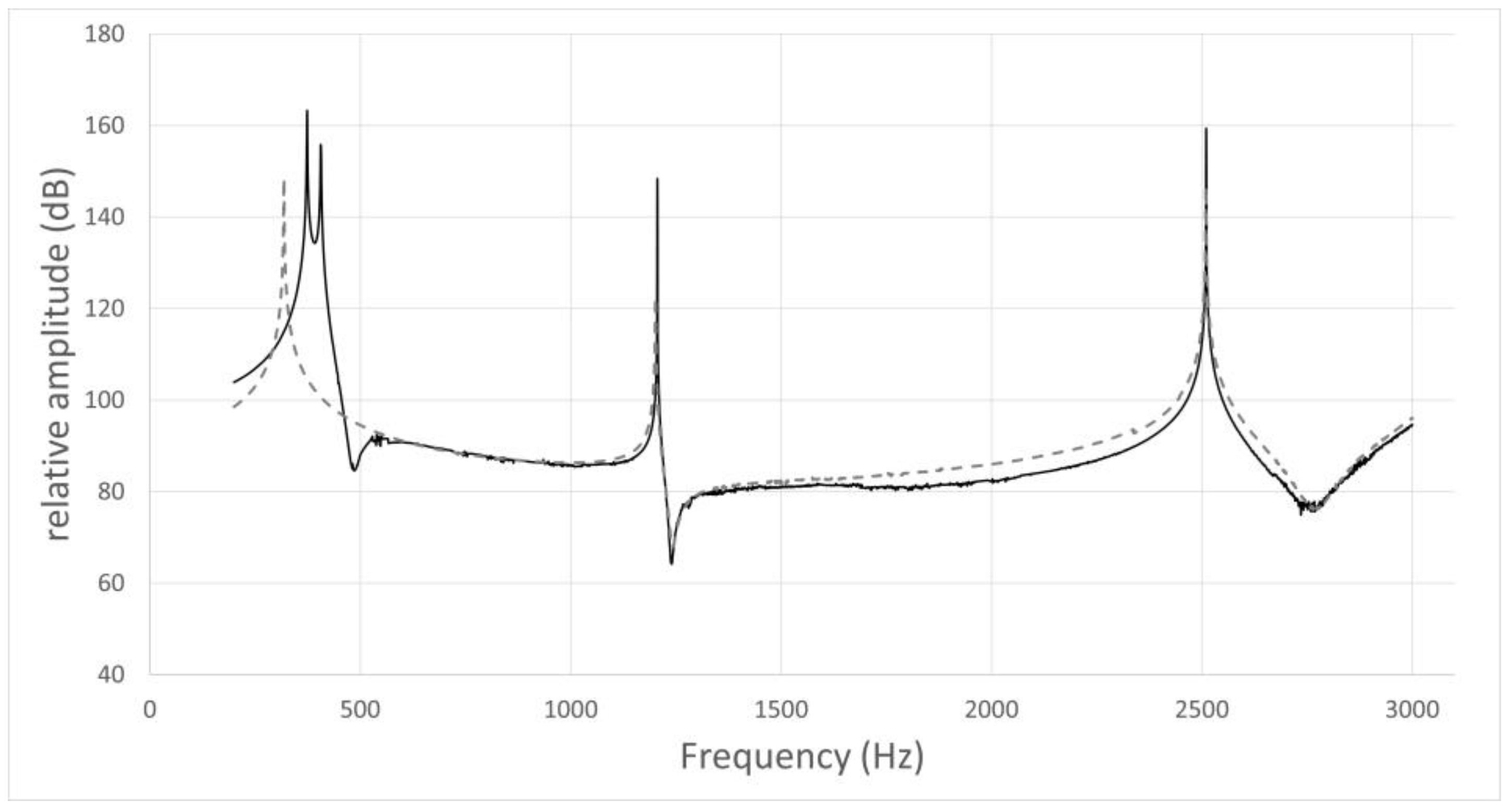

Figure 3.

Frequency response curve for /i/ in subject No. 4.

Figure 3.

Frequency response curve for /i/ in subject No. 4.

The simulation result of the model including the nasal cavity and sinuses is indicated by the solid line, and that of the model excluding the nasal cavity and sinuses by the dotted line. In the former curve, the first peak is F1 (374 Hz), the second is due to nasal coupling for a pole–zero pair (pole: 406 Hz; zero: 486 Hz), the third is a pole–zero pair (pole: 1206 Hz; zero: 1240 Hz), and the fourth is F2 (2510 Hz). In the latter curve, the first peak is F1 (319 Hz), the second is not due to nasal coupling for a pole–zero pair (pole: 1202 Hz; zero: 1242 Hz), and the third is F2 (2509 Hz).

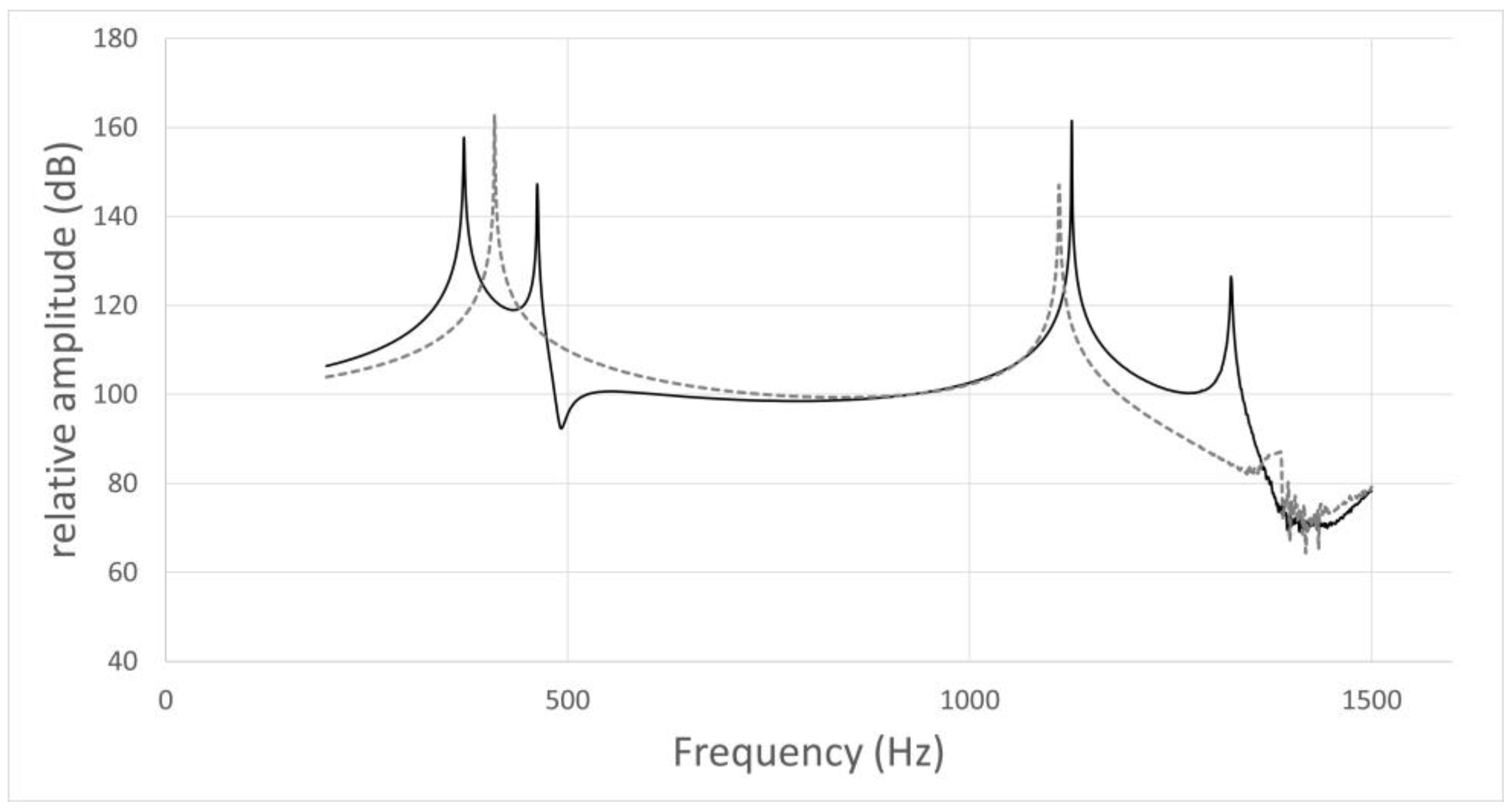

Figure 4.

Frequency response curve for /u/ in subject No. 1.

Figure 4.

Frequency response curve for /u/ in subject No. 1.

The simulation result of the model including the nasal cavity and sinuses is indicated by the solid line, and that of the model not including the nasal cavity and sinuses by the dotted line. In the former curve, the first peak is F1 (371 Hz), the second is due to nasal coupling for a pole–zero pair (pole: 462 Hz; zero: 492 Hz), and the third is F2 (1127 Hz). In the latter curve, the first peak is F1 (409 Hz) and the second is F2 (1111 Hz).

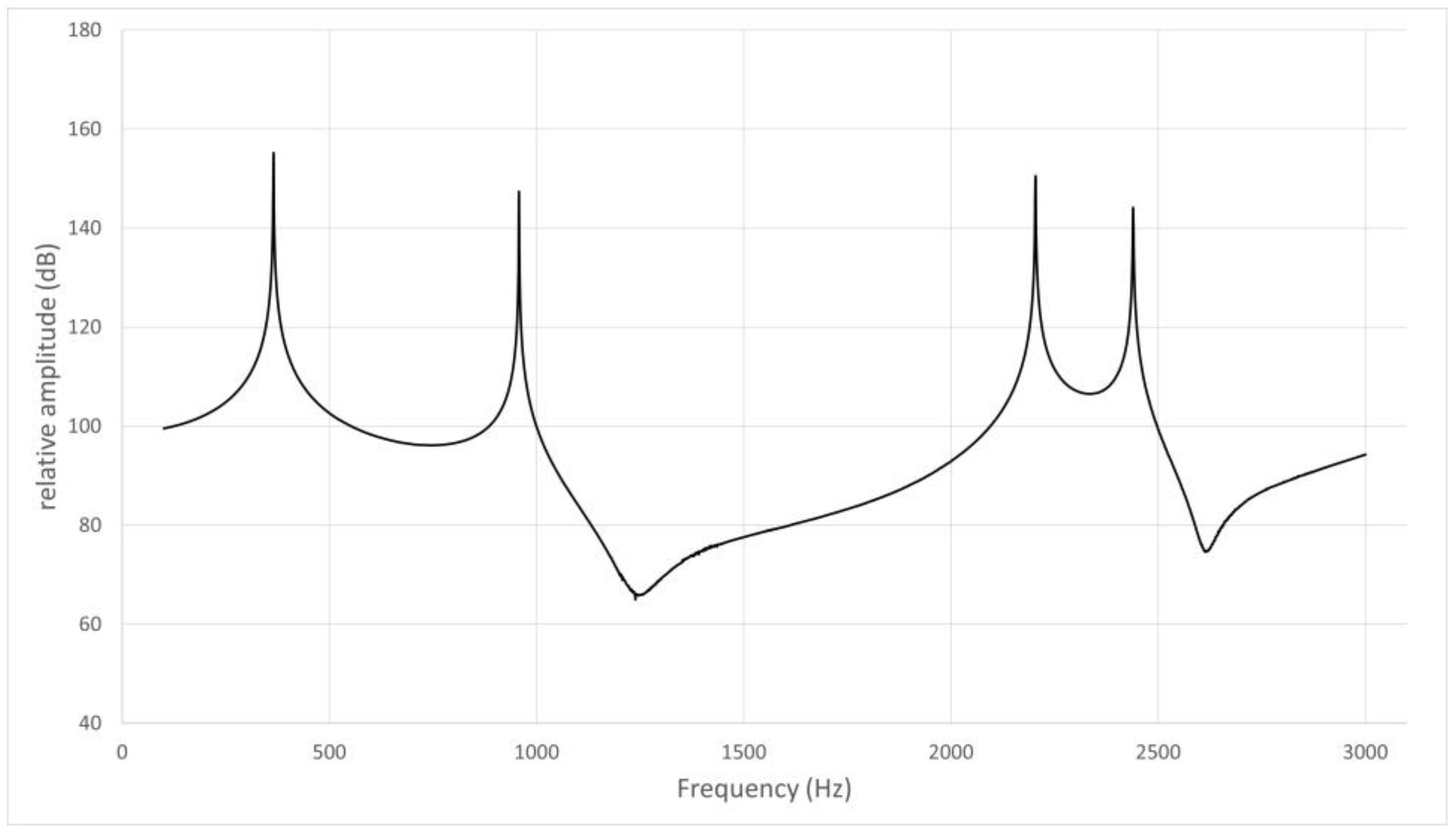

Figure 5.

Frequency response curve for /i/ in subject No. 2.

Figure 5.

Frequency response curve for /i/ in subject No. 2.

The frequency response curve obtained from the simulation of the models without the nasal cavity and sinuses is shown. The first peak is F1 (365 Hz), the second is a pole–zero pair (pole: 944 Hz, zero: 1175 Hz) not due to nasal coupling, and the third is F2 (2204 Hz).

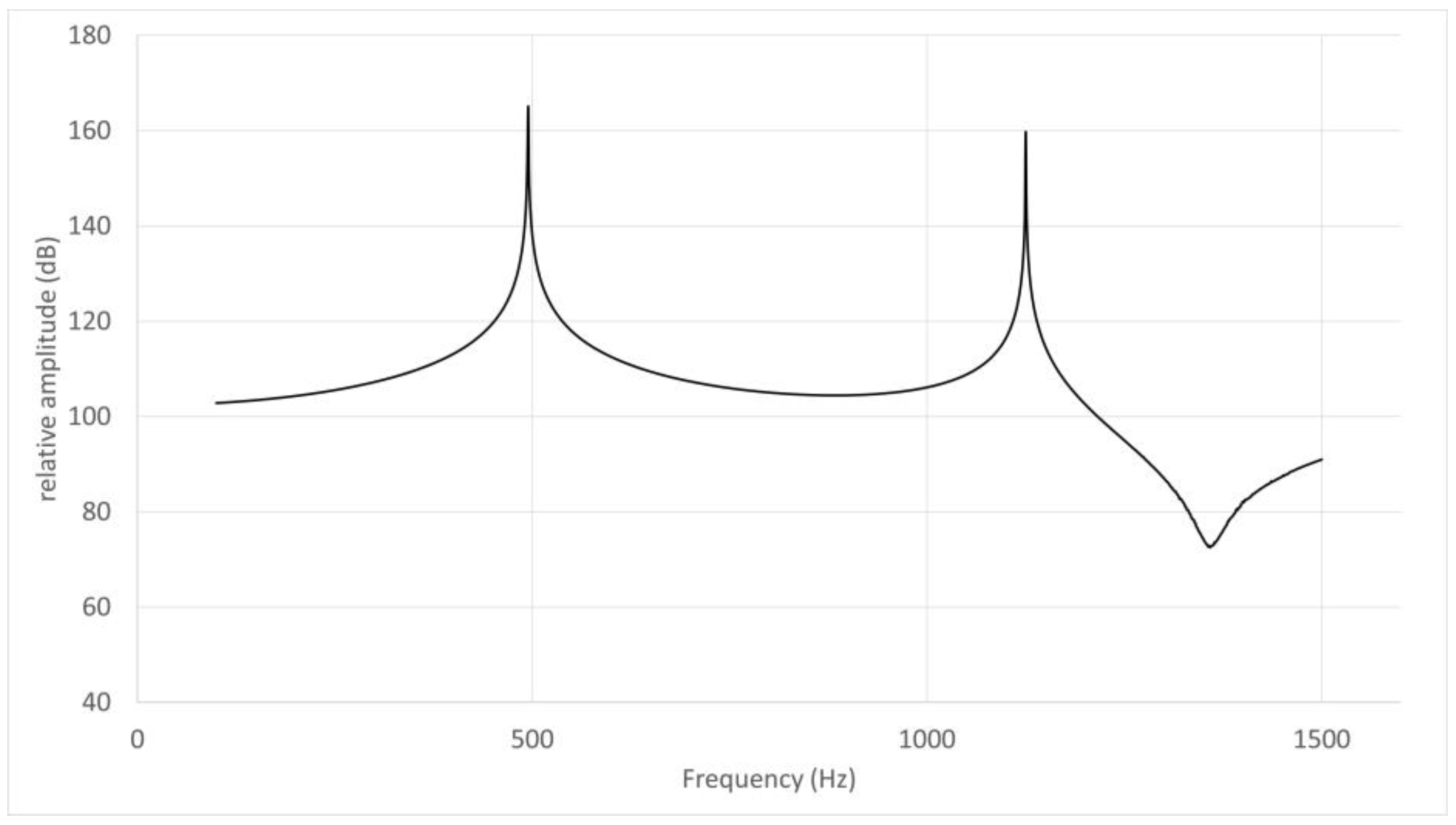

Figure 6.

Frequency response curve for /u/ in subject No. 5.

Figure 6.

Frequency response curve for /u/ in subject No. 5.

The frequency response curve obtained from the simulation of the models without the nasal cavity and sinuses is shown. The first peak is F1 (495 Hz) and the second is F2 (1220 Hz).

4. Discussion

By using the boundary element method in the same way as for the Japanese vowel /a/ and applying the same parameter settings [

6], an acoustic simulation could be stably performed for the Japanese vowels /i/ and /u/. In a previous study [

11], F1 and F2 of /i/ ranged from 250 to 500 Hz and from 2000 to 3000 Hz, respectively, and those of /u/ ranged from 300 to 500 Hz and from 1000 to 2000 Hz, respectively; the formant frequencies obtained from the present simulation were almost within these ranges.

Regarding the sound analysis of the Japanese vowel /a/ in a previous study [

6], the sound source was set as a point in a place corresponding to the vocal cords, the sound was modified by reflection, absorption, and interference on the wall of the vocal tract, and the boundary element method was used to analyze the sound radiated to the outside space from the mouth and nostrils. In the present study, we considered that the Japanese vowels /i/ and /u/ could be simulated by using the same boundary element method with the same parameter settings, that is, the wall of the vocal tract and the bottom end of the virtual trachea were regarded as rigid and very soft walls, respectively, and the sound velocity and density were set at 37 °C.

In the verification using actual voice, the relative discrimination thresholds were within 9%, except for one of the six cases for F1 of /i/ and two of six cases for F2 of /u/. No significant difference was found between the numbers of participants in whom the relative discrimination thresholds were 9% or less in the present simulations of /i/ and /u/ or the previous simulation of /a/ [

6]. Similar to the previous simulation of /a/, the relative discrimination thresholds became less than 9% by adjusting the length of the virtual cylindrical extension of the lower part of the glottis. In the present study, as the length of the virtual trachea shortened, the formant frequency increased, except for F1 of /i/ in subject No. 1. However, discussing the appropriate length of the virtual trachea exceeds the scope of the present study.

Peaks other than the formant frequencies were observed in the frequency response curves obtained by the present acoustic simulation using the boundary element method. Chen [

12] reported that peaks arising from nasalization are often observed at a position lower than F1 or between F1 and F2 in narrow vowels with a high tongue position. In the present study, peaks were observed between F1 and F2 for /i/ and /u/ (

Table 6). Because the Japanese vowels /i/ and /u/ are narrow vowels, our results were consistent with those reported by Chen [

12]. Peaks around 500 Hz have been observed for vowels [

13]. Because a peak around 500 Hz is not observed in vocal tract models without a nasal cavity, the peak, i.e., the pole–zero pair, is considered to arise from the nasal coupling of vowels [

13].

It is also known that a pole–zero pair appears around 500 Hz because of nasal coupling, and that the presence of a pole–zero pair changes the position where the peak of F1 appears in the frequency response curves [

13]. In the present study, among three participants with nasal coupling, the obtained peaks of F1 shifted to the low frequency side in two participants for /i/ and to the high frequency side in three for /u/ in the simulated vocal tract models in which the nasal cavity and sinuses had been removed.

Pole–zero pairs not due to nasal coupling have been reported to be generated by the resonance of the paranasal cavities, thereby causing the frequency response curves to become complicated [

14]. In the present simulation of the Japanese vowel /i/, two peaks appearing at around 500 and 1000 Hz were observed between F1 and F2. The peak at around 500 Hz was considered to be the pole–zero pair due to nasal coupling. The other peak at a higher frequency occurred at around 1000 Hz in /i/ for all participants. No gender difference in the occurrence of the peaks was observed. Because a peak was observed at 1000 Hz regardless of the presence of the nasal cavity, the peaks were considered to have been generated on either site of the vocal tract, excluding the nasal coupling. However, further discussion exceeds the limitations of the present study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.M.; Methodology, K.M.; Software, M.T. and M.M; Validation, M.S. and, H.U.; Formal Analysis, M.S., M.T. and M.M.; Investigation, M.S., M.T., M.M. and, H.U. ; Resources, M.T. and M.M; Data Curation, M.S.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, M.S. and K.M.; Writing – Review & Editing, M.S. and K.M.; Visualization, M.S. and K.M.; Supervision, K.M.; Project Administration, K.M.; Funding Acquisition, K.M.