Submitted:

02 May 2023

Posted:

03 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

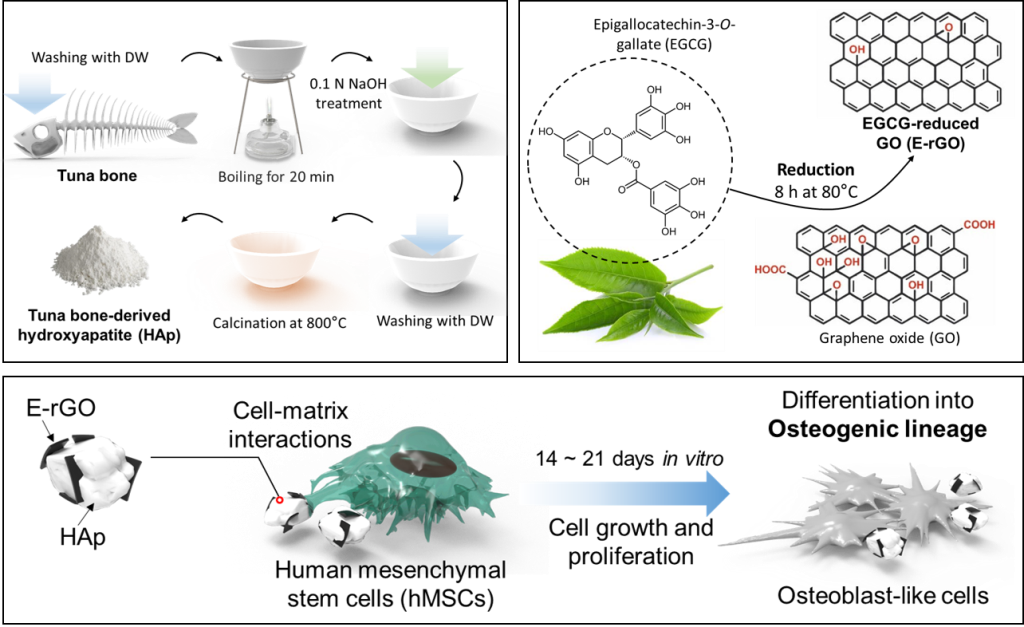

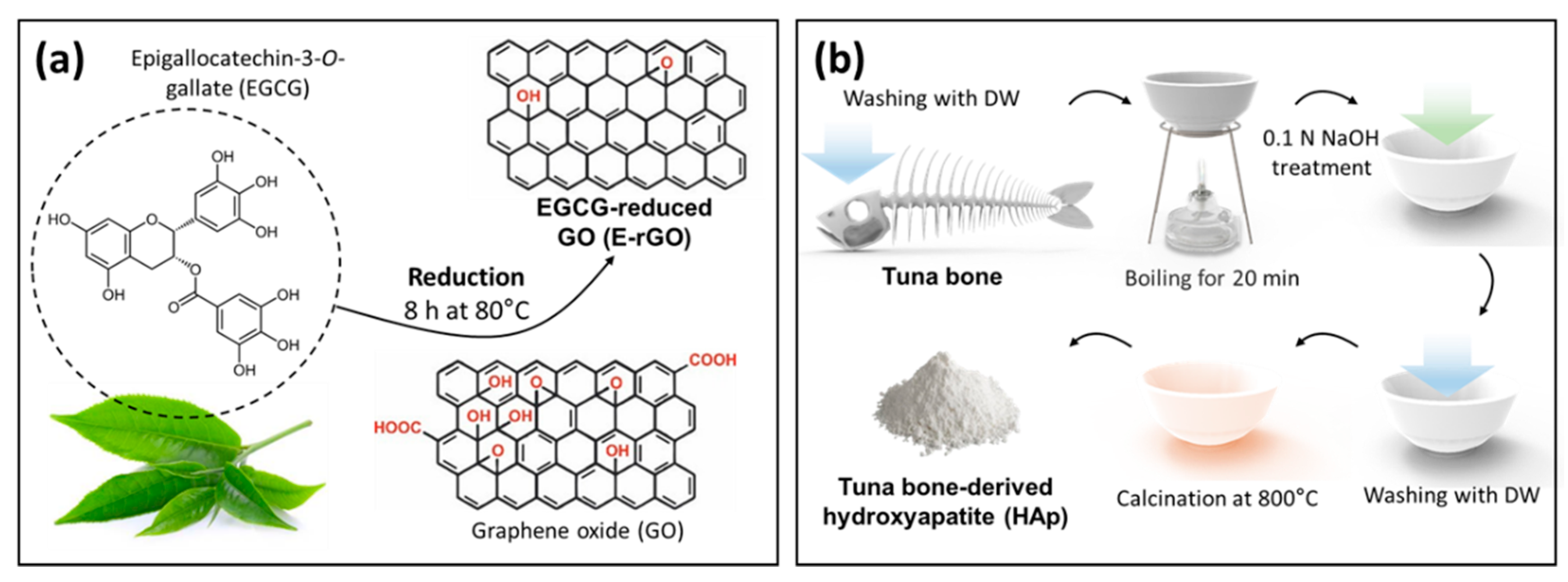

2.1. Preparation of E-rGO/HAp composites

2.1.1. Preparation of E-rGO and tuna bone-derived HAp

2.1.2. Synthesis of E-rGO/HAp composites

2.2. Physicochemical characterizations

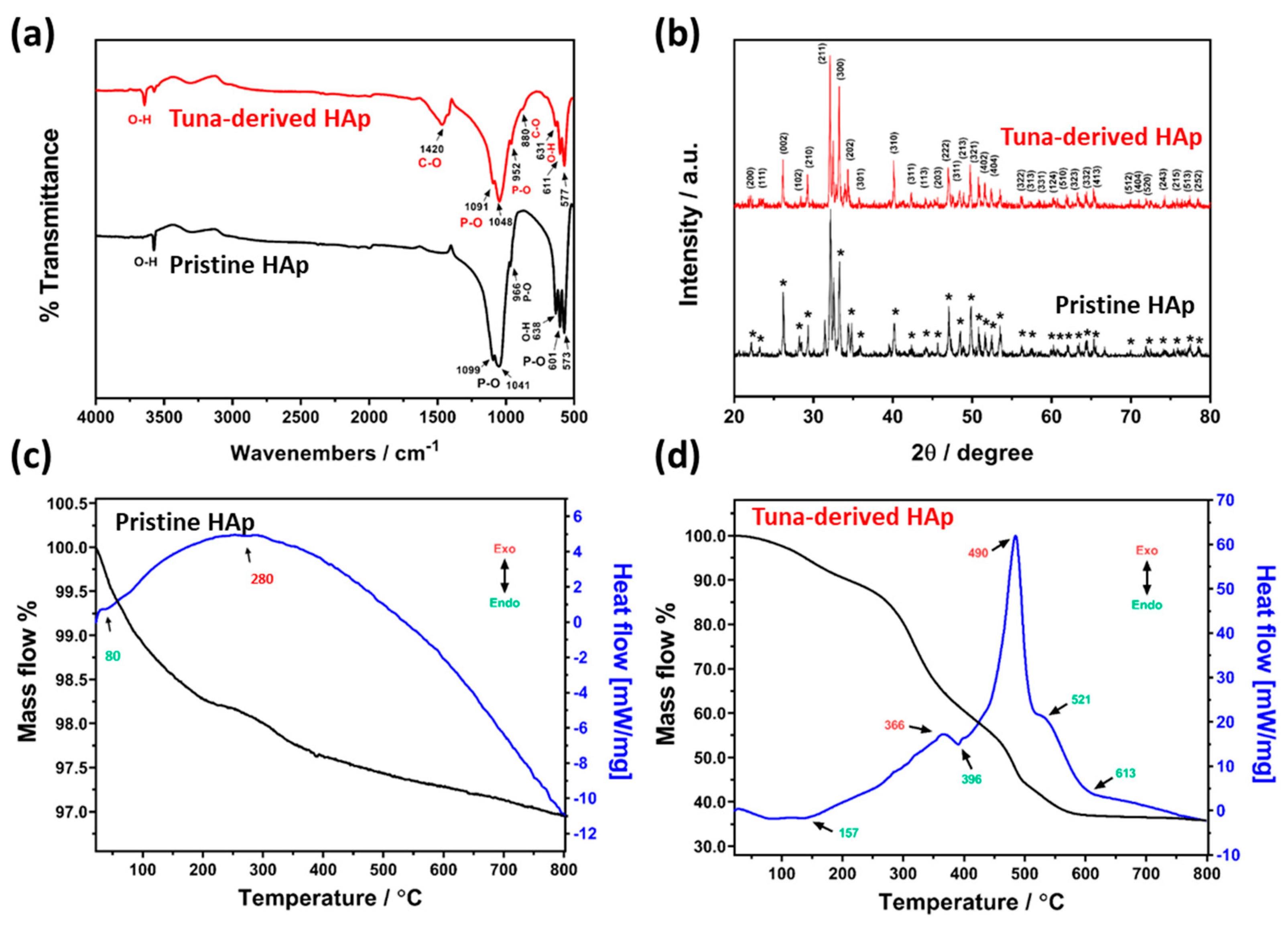

2.2.1. Physicochemical characterizations of tuna bone-derived HAp

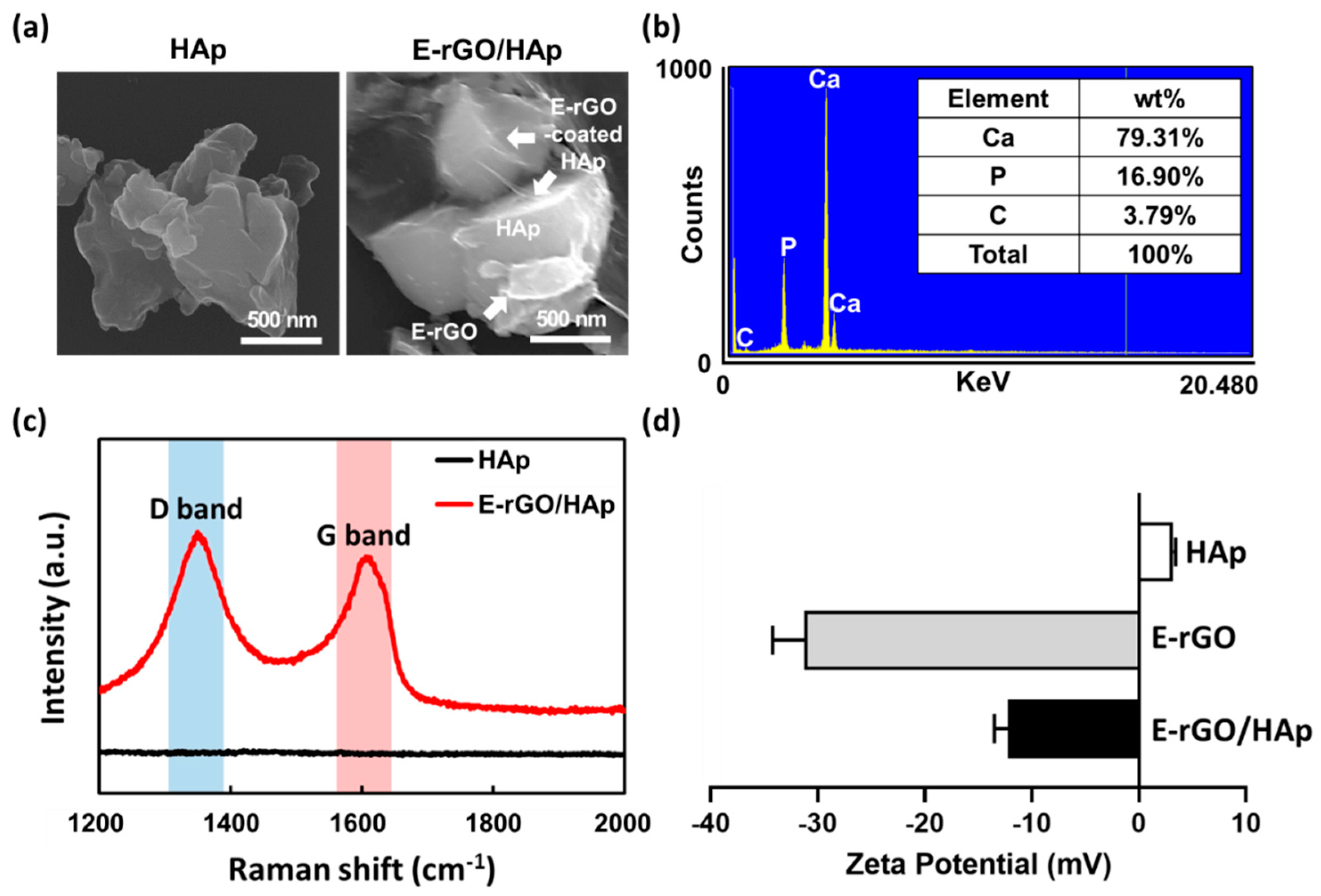

2.2.2. Physicochemical characterizations of E-rGO/HAp composites

2.3. Cell culture conditions

2.4. Cell proliferation assay

2.5. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity assay and alizarin red S (ARS) staining

2.6. Statistical analysis

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kang, M.S.; Jeong, S.J.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, B.; Hong, S.W.; Lee, J.H.; Han, D.-W. Reduced graphene oxide coating enhances osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells on Ti surfaces. Biomater. Res. 2021, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Li, M.; Su, H.; Chen, H.; Zhu, Y. Up-to-date progress in bioprinting of bone tissue. Int. J. Bioprinting 2022, 9, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.N.; Cammisa Jr, F.P.; Sandhu, H.S.; Diwan, A.D.; Girardi, F.P.; Lane, J.M. The biology of bone grafting. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2005, 13, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balhuc, S.; Campian, R.; Labunet, A.; Negucioiu, M.; Buduru, S.; Kui, A. Dental Applications of Systems Based on Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles—An Evidence-Based Update. Crystals 2021, 11, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, G.; Pandey, A. Biodegradable bone implants in orthopedic applications: a review. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 40, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C.-Y.; Lin, T.-L.; Lin, Y.-H.; Lee, A.K.-X.; Ng, S.Y.; Huang, T.-H.; Hsu, T.-T. Synergistic Effect of Static Magnetic Fields and 3D-Printed Iron-Oxide-Nanoparticle-Containing Calcium Silicate/Poly-ε-Caprolactone Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. Cells 2022, 11, 3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Gao, S.; Lu, R.; Wang, X.; Chen, S. In Vitro and In Vivo Studies of Hydrogenated Titanium Dioxide Nanotubes with Superhydrophilic Surfaces during Early Osseointegration. Cells 2022, 11, 3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghali, A. Craniofacial Bone Tissue Engineering: Current Approaches and Potential Therapy. Cells 2021, 10, 2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobasherpour, I.; Heshajin, M.S.; Kazemzadeh, A.; Zakeri, M. Synthesis of nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite by using precipitation method. J. Alloy. Compd. 2007, 430, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, S.; Nasri, C.S.S.M.; Bin Arshad, S.E. Hydrothermal synthesis of hydroxyapatite powders using Response Surface Methodology (RSM). PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0251009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, M.; Zahrani, E.M. Mechanical alloying synthesis and bioactivity evaluation of nanocrystalline fluoridated hydroxyapatite. J. Cryst. Growth 2009, 311, 1392–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeong, K.; Wang, J.; Ng, S. Mechanochemical synthesis of nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite from CaO and CaHPO4. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 2705–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, Y.-H.; Kuo, C.-S.; Li, Y.-Y.; Huang, C.-P. Polymer-assisted synthesis of hydroxyapatite nanoparticle. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2009, 29, 819–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, V.; Lazăr, D.; Turcu, R.; Mocuta, H.; Magyari, K.; Prinz, M.; Neumann, M.; Simon, S. Atomic environment in sol–gel derived nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2009, 165, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Gupta, K.C.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.; Kang, I.-K. Osteoblast behaviours on nanorod hydroxyapatite-grafted glass surfaces. Biomater. Res. 2019, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.; Lee, J.W.; Heo, J.H.; Park, C.; Kim, D.-H.; Yi, G.S.; Kang, H.C.; Jung, H.S.; Shin, H.; Lee, J.H. Natural bone-mimicking nanopore-incorporated hydroxyapatite scaffolds for enhanced bone tissue regeneration. Biomater. Res. 2022, 26, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Kim, J.H.; Shim, J.H.; Hwang, N.S.; Heo, C.Y. Bioactive calcium phosphate materials and applications in bone regeneration. Biomater. Res. 2019, 23, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akram, M.; Ahmed, R.; Shakir, I.; Ibrahim, W.A.W.; Hussain, R. Extracting hydroxyapatite and its precursors from natural resources. J. Mater. Sci. 2014, 49, 1461–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronan, K.; Kannan, M.B. Novel Sustainable Route for Synthesis of Hydroxyapatite Biomaterial from Biowastes. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 2237–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergely, G.; Wéber, F.; Lukács, I.; Tóth, A.L.; Horváth, Z.E.; Mihály, J.; Balázsi, C. Preparation and characterization of hydroxyapatite from eggshell. Ceram. Int. 2010, 36, 803–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, M.; Kumar, T.; Shantha, K.; Rao, K. Development of hydroxyapatite derived from Indian coral. Biomaterials 1996, 17, 1709–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondal, B.; Mondal, S.; Mondal, A.; Mandal, N. Fish scale derived hydroxyapatite scaffold for bone tissue engineering. Mater. Charact. 2016, 121, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, N.A.; Khil, M.S.; Omran, A.; Sheikh, F.A.; Kim, H.Y. Extraction of pure natural hydroxyapatite from the bovine bones bio waste by three different methods. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2009, 209, 3408–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Liu, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Z. Changes in physicochemical and biological properties of porcine bone derived hydroxyapatite induced by the incorporation of fluoride. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2017, 18, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jongjareonrak, A.; Benjakul, S.; Visessanguan, W.; Nagai, T.; Tanaka, M. Isolation and characterisation of acid and pepsin-solubilised collagens from the skin of Brownstripe red snapper (Lutjanus vitta). Food Chem. 2005, 93, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Pal, A.; Choudhury, A.R.; Bodhak, S.; Balla, V.K.; Sinha, A.; Das, M. Effect of trace elements on the sintering effect of fish scale derived hydroxyapatite and its bioactivity. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 15678–15684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culurgioni, J.; Mele, S.; Merella, P.; Addis, P.; Figus, V.; Cau, A.; Karakulak, F.S.; Garippa, G. Metazoan gill parasites of the Atlantic bluefin tuna Thunnus thynnus (Linnaeus) (Osteichthyes: Scombridae) from the Mediterranean and their possible use as biological tags. Folia Parasitol. 2014, 61, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, J.; Kim, S.K. Effect of Temperature on Isolation and Characterization of Hydroxyapatite from Tuna (Thunnus obesus) Bone. Materials 2010, 3, 4761–4772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Feng, C.; Cao, Q.; Wang, W.; Ma, Z.; Wu, Y.; He, T.; Jing, Y.; Tan, W.; Liao, T.; et al. Strategies of strengthening mechanical properties in the osteoinductive calcium phosphate bioceramics. Regen. Biomater. 2023, 10, rbad013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.-W.; Hong, S.W. Multifaceted Biomedical Applications of Graphene, 1st ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 1–264. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H.; Shin, Y.C.; Jin, O.S.; Kang, S.H.; Hwang, Y.-S.; Park, J.-C.; Hong, S.W.; Han, D.-W. Reduced graphene oxide-coated hydroxyapatite composites stimulate spontaneous osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 11642–11651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.C.; Bae, J.-H.; Lee, J.H.; Raja, I.S.; Kang, M.S.; Kim, B.; Hong, S.W.; Huh, J.-B.; Han, D.-W. Enhanced osseointegration of dental implants with reduced graphene oxide coating. Biomater. Res. 2022, 26, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.C.; Lee, J.H.; Jin, O.S.; Kang, S.H.; Hong, S.W.; Kim, B.; Park, J.-C.; Han, D.-W. Synergistic effects of reduced graphene oxide and hydroxyapatite on osteogenic differentiation of MC3T3-E1 preosteoblasts. Carbon 2015, 95, 1051–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, I.S.; Preeth, D.R.; Vedhanayagam, M.; Hyon, S.-H.; Lim, D.; Kim, B.; Rajalakshmi, S.; Han, D.-W. Polyphenols-loaded electrospun nanofibers in bone tissue engineering and regeneration. Biomater. Res. 2021, 25, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, L.; Song, H.; Zhan, Z.; Lv, Y. Multifunctional Reduced Graphene Oxide-Based Nanoplatform for Synergistic Targeted Chemo-Photothermal Therapy. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 5213–5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, Z.; Yin, J. Facile Synthesis of Soluble Graphene via a Green Reduction of Graphene Oxide in Tea Solution and Its Biocomposites. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 1127–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrasekar, A.; Sagadevan, S.; Dakshnamoorthy, A. Synthesis and characterization of nano-hydroxyapatite (n-HAP) using the wet chemical technique. Int J Phys Sci 2013, 8, 1639–1645. [Google Scholar]

- Mathirat, A.; Dalavi, P.A.; Prabhu, A.; G.V., Y.D.; Anil, S.; Senthilkumar, K.; Seong, G.H.; Sargod, S.S.; Bhat, S.S.; Venkatesan, J. Remineralizing Potential of Natural Nano-Hydroxyapatite Obtained from Epinephelus chlorostigma in Artificially Induced Early Enamel Lesion: An In Vitro Study. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouyer, E.; Gitzhofer, F.; Boulos, M.I. Morphological study of hydroxyapatite nanocrystal suspension. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2000, 11, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Egaña, A.; Díaz-Cuenca, A.; Boccaccini, A.R. Tuning of Cell–Biomaterial Anchorage for Tissue Regeneration. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 4049–4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, K.A.; Gross, V.; Berndt, C.C. Thermal Analysis of Amorphous Phases in Hydroxyapatite Coatings. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1998, 81, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.-J.; Lin, F.-H.; Chen, K.-S.; Sun, J.-S. Thermal decomposition and reconstitution of hydroxyapatite in air atmosphere. Biomaterials 1999, 20, 1807–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capanema, N.S.; Mansur, A.A.; Carvalho, S.M.; Silva, A.R.; Ciminelli, V.S.; Mansur, H.S. Niobium-doped hydroxyapatite bioceramics: synthesis, characterization and in vitro cytocompatibility. Materials 2015, 8, 4191–4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miculescu, F.; Antoniac, I.; Ciocan, L.T.; Miculescu, M.; Brânzei, M.; Ernuteanu, A.; Batalu, D.; Berbecaru, A. Complex analysis on heat treated human compact bones. UPB Sci Bull B 2011, 73, 203–211. [Google Scholar]

- Amirthalingam, N.; Deivarajan, T.; Paramasivam, M. Mechano chemical synthesis of hydroxyapatite using dolomite. Mater. Lett. 2019, 254, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lee, J.; Moursi, A.; Lannutti, J.J. Ca/P ratio effects on the degradation of hydroxyapatite in vitro. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2003, 67, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Yazici, H.; Ergun, C.; Webster, T.J.; Bermek, H. An in vitro evaluation of the Ca/P ratio for the cytocompatibility of nano-to-micron particulate calcium phosphates for bone regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2008, 4, 1472–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, M.C.; Kang, M.S.; Park, R.; Chae, S.Y.; Han, D.-W.; Hong, S.W. Differential cellular interactions and responses to ultrathin micropatterned graphene oxide arrays with or without ordered in turn RGD peptide films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 561, 150115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.O.; Lee, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Shin, Y.C.; Huh, J.B.; Bae, J.-H.; Kang, S.H.; Hong, S.W.; Kim, B.; Yang, D.J.; et al. Graphene oxide-coated guided bone regeneration membranes with enhanced osteogenesis: Spectroscopic analysis and animal study. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2016, 51, 540–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.S.; Kang, J.I.; Le Thi, P.; Park, K.M.; Hong, S.W.; Choi, Y.S.; Han, D.-W.; Park, K.D. Three-Dimensional Printable Gelatin Hydrogels Incorporating Graphene Oxide to Enable Spontaneous Myogenic Differentiation. ACS Macro Lett. 2021, 10, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Guoxin, H.; Gao, H. Raman Spectroscopic Characterization of Graphene. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2010, 45, 369–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-J.; Liu, C.-M.; Xie, Y.-B.; Cao, H.-B.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, Y. The evolution of surface charge on graphene oxide during the reduction and its application in electroanalysis. Carbon 2013, 66, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, D.H. Basic Principles of Colloid Science, 1st ed.; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2007; pp. 1–243. [Google Scholar]

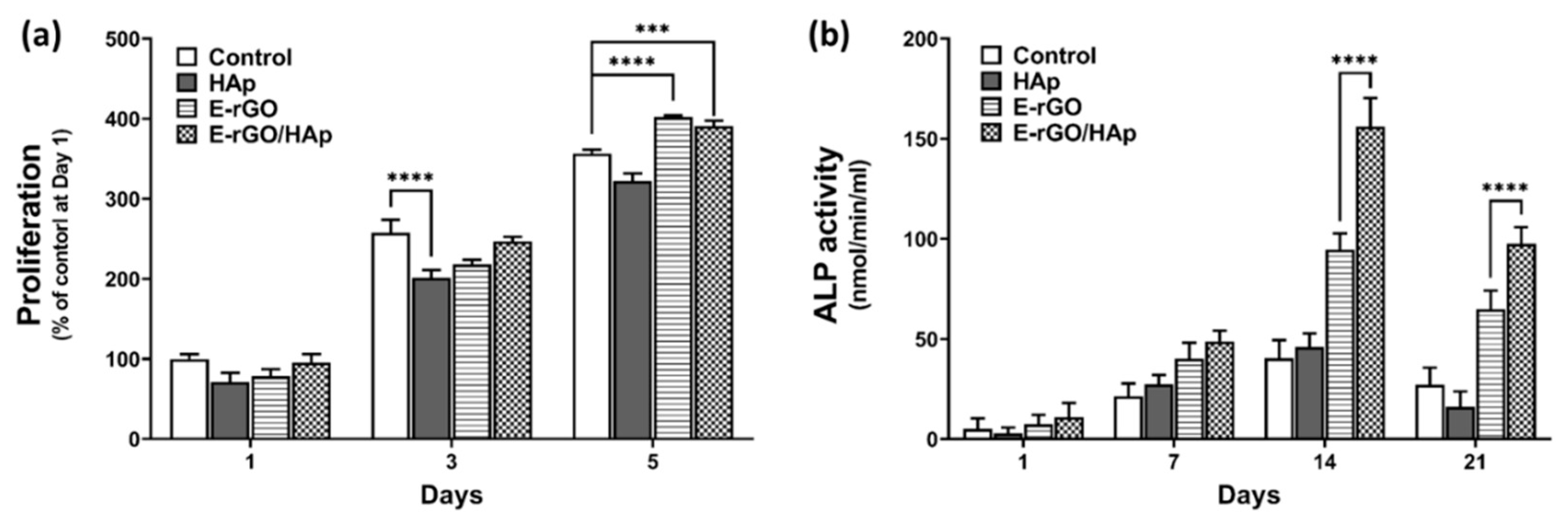

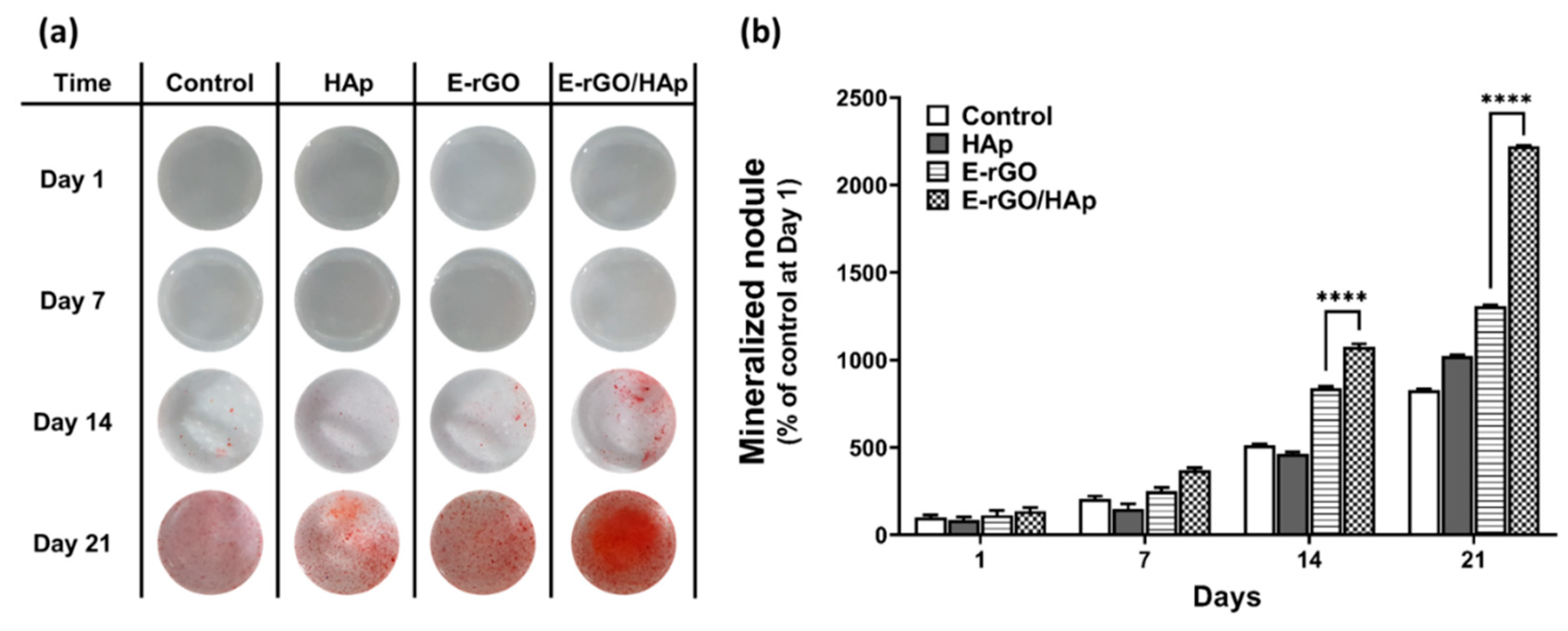

- Blair, H.C.; Larrouture, Q.C.; Li, Y.; Lin, H.; Beer-Stoltz, D.; Liu, L.; Tuan, R.S.; Robinson, L.J.; Schlesinger, P.H.; Nelson, D.J. Osteoblast differentiation and bone matrix formation in vivo and in vitro. Tissue Eng B 2017, 23, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrobel, E.; Leszczynska, J.; Brzoska, E. The Characteristics Of Human Bone-Derived Cells (HBDCS) during osteogenesis in vitro. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2016, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, R.; Feng, Q. In Vitro Uptake of Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles and Their Effect on Osteogenic Differentiation of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cells Int. 2018, 2018, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, H.; Ran, K.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, H.; Shangguan, J.; Tong, M.; Yang, J.; Yao, Q.; Xu, H. Porous hydroxyapatite scaffold orchestrated with bioactive coatings for rapid bone repair. Biomater. Adv. 2023, 144, 213202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Han, W.; He, W.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Feng, H.; Qian, Y. Surface topography of hydroxyapatite promotes osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 60, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Chow, K.L.; Leng, Y. Study of hydroxyapatite osteoinductivity with an osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2008, 89A, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Gao, X.; Li, X.; Zhu, G.; Li, N.; Shi, X.; Wang, Y. Calcium alendronate-coated composite scaffolds promote osteogenesis of ADSCs via integrin and FAK/ERK signalling pathways. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 6912–6924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Fierens, K.; Zhang, Z.; Vanparijs, N.; Schuijs, M.J.; Van Steendam, K.; Gracia, N.F.; De Rycke, R.; De Beer, T.; De Beuckelaer, A.; et al. Spontaneous Protein Adsorption on Graphene Oxide Nanosheets Allowing Efficient Intracellular Vaccine Protein Delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 1147–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Shin, Y.C.; Lee, S.-M.; Jin, O.S.; Kang, S.H.; Hong, S.W.; Jeong, C.-M.; Huh, J.B.; Han, D.-W. Enhanced Osteogenesis by Reduced Graphene Oxide/Hydroxyapatite Nanocomposites. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 18833–18833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Yu, P.; Shi, X.; Ling, T.; Zeng, W.; Chen, A.; Yang, W.; Zhou, Z. Hierarchically Porous Hydroxyapatite Hybrid Scaffold Incorporated with Reduced Graphene Oxide for Rapid Bone Ingrowth and Repair. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 9595–9606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).