1. Introduction

Migraine adversely affects individuals and society as the second leading cause of years lived with disability worldwide [

1]. Migraine is characterized by recurrent headache attacks that are preceded by transient neurological symptoms referred to as aura in some cases [

2]. Migraine aura emerges as visual scintillations and scotoma in most cases and, less often, as hemisensory symptoms or dysphasia. In typical cases, these neurological symptoms last 5–60 min, and headache ensues. This temporal sequence of migraine attacks has been attracting much interest of headache researchers. Migraine aura is caused by cortical spreading depolarization (CSD), a concentrically propagating wave of abrupt and sustained near-complete breakdown of transmembrane ion gradient and mass depolarization in the brain tissue [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. CSD has been shown to activate the trigeminal system [

11,

12,

13], indicating that CSD may be responsible for migraine headache as well as migraine aura. The putative mechanisms whereby CSD induces the trigeminal system include meningeal neurogenic inflammation, parenchymal neuroinflammation, and cortical metabolic changes [

14]. CSD is widely used to produce a migraine model in animal studies [

15]. It is known that CSD causes sustained electrical activation of rat trigeminal ganglion (TG) neurons on the ipsilateral side [

11]. This finding was reinforced by the subsequent observation that neuronal activation was initiated after CSD in laminae I-II of the trigeminal nucleus caudalis [

12]. Traditionally, CSD has been induced mainly by application KCl application or pinprick stimulation on the cortical surface, which necessitates invasive surgical procedures including craniotomy. Consequently, there is a concern that such invasiveness may render the interpretation of data difficult especially in pain/headache-related studies.

Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) is expressed in TG neurons that provide meningeal sensory innervation, especially in the perivascular area [

16,

17]. Peripheral action of CGRP is likely to play a pivotal role in the generation of migraine headache, because CGRP-targeted monoclonal antibodies, which do not readily cross the blood–brain barrier, confer potent migraine prevention [

18]. Trigeminal activation is known to induce CGRP release from the meningeal trigeminal fibers [

19,

20,

21]. Several lines of evidence indicate that CGRP induces the sensitization of nociceptors [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. The sensitization of trigeminal nociceptors renders normally innocuous mechanical stimulation from vascular pulsation noxious stimuli, which is ultimately perceived as pulsating headache in the brain [

17]. For the assessment of trigeminal activation relevant to migraine pathophysiology, it is crucial to investigate the status of de novo CGRP synthesis in TG neurons.

In the present study, we explore the effects of CSD on CGRP mRNA expression in TG neurons employing in situ hybridization (ISH) of TG tissue and a relatively noninvasive CSD induction method that requires neither craniotomy nor electrode installation into the brain parenchyma.

2. Results

2.1. CSD Induction

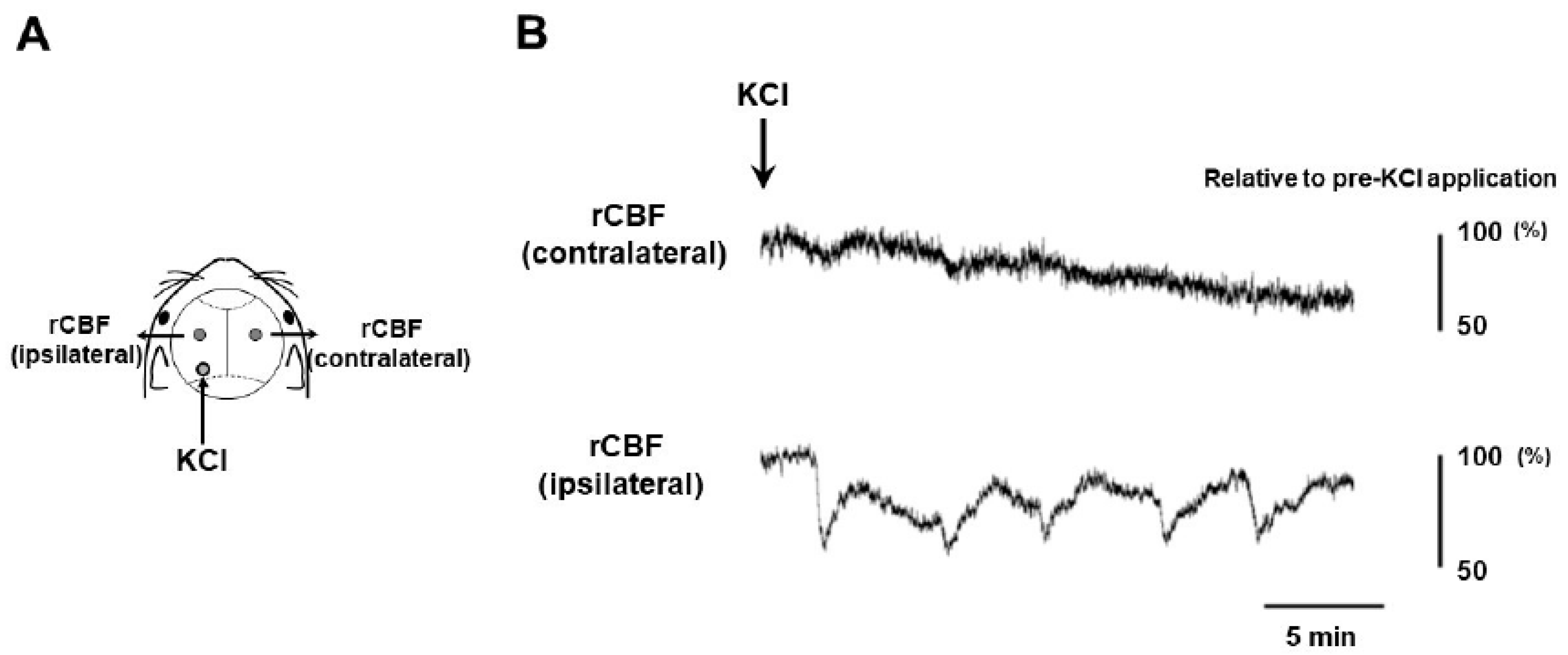

Our experimental setting for CSD induction and recording is depicted in

Figure 1A. The occurrence of five CSD episodes in the left cerebral hemisphere was confirmed by observing regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) changes detectable by Laser Doppler flowmetry (

Figure 1B). The left TG tissue was successfully sampled from CSD-subjected mice at 6, 24, 48, and 72 h after CSD induction (N = 3 at each timepoint). In addition, we used untreated mice as controls (N = 2). Hence, there were the following experimental groups in the present study; the control, 6 h post-CSD, 24 h post-CSD, 48 h post-CSD, and 72 h post-CSD groups.

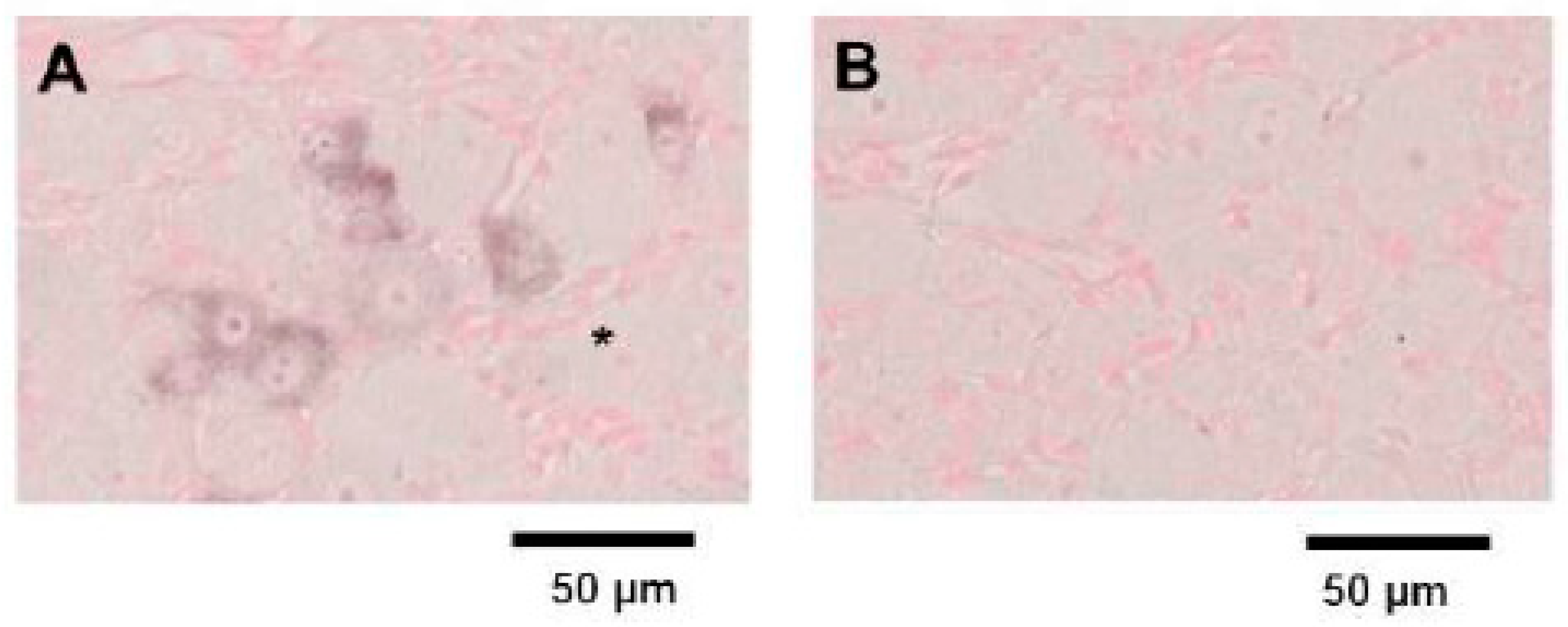

2.2. ISH for Mouse CGRP mRNA in TG Tissue

We initially designed four different ISH probes (Calca-1, Calca-2, Calca-3, and Calca-4) for mouse

CGRP mRNA. In preliminary experiments, we visualized

CGRP mRNA expression in mouse embryonic day 18.5 thyroid tissue using these probes, which revealed that the Calca-4 probe achieved the greatest staining performance (data not shown). The ISH of mouse TG tissue using the Calca-4 anti-sense probe identified

CGRP mRNA expression mainly in small to medium-sized neurons (

Figure 2A). On the other hand, there was no significant staining in ISH analysis using the Calca-4 sense probe (

Figure 2B). From these results, we used the Calca-4 probe for further ISH studies.

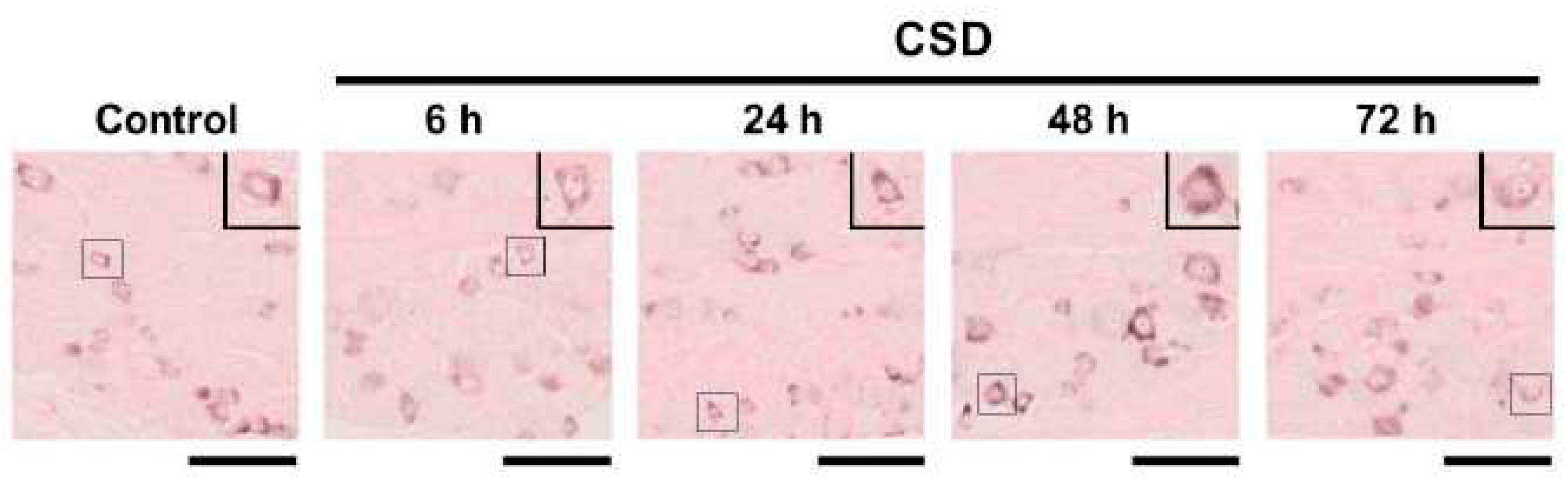

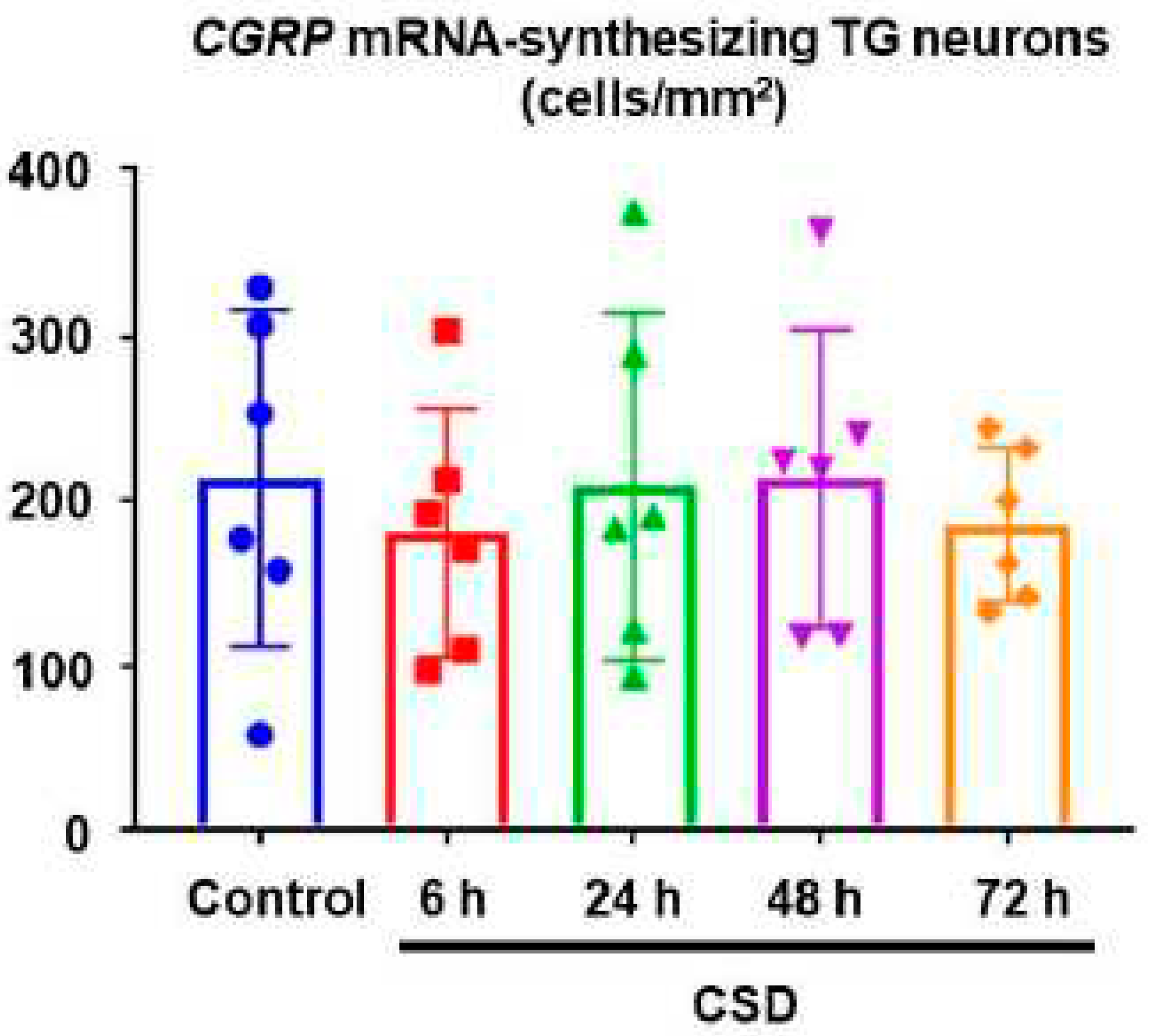

2.3. Density of CGRP mRNA-Synthesizing TG Neurons after CSD

We examined the density of

CGRP mRNA-synthesizing TG neurons in the control and CSD-subjected mice. Six tissue sections were studied in each experimental group. Representative TG tissue photographs of ISH for

CGRP mRNA are shown in

Figure 3. The density of

CGRP mRNA-synthesizing TG neurons in control mice was 214.4 ± 102.4 (mean ± SD) cells/mm

2, which served as the reference value. CSD did not exert any significant effect on the density of

CGRP mRNA-synthesizing TG neurons (181.4 ± 75.4 cells/mm

2 at 6 h post-CSD, 209.3 ± 75.4 cells/mm

2 at 24 h post-CSD, 214.4 ± 90.6 cells/mm

2 at 48 h post-CSD, and 186.3 47.0 cells/mm

2 at 72 h post-CSD; P = 0.9373, Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test,

Figure 4).

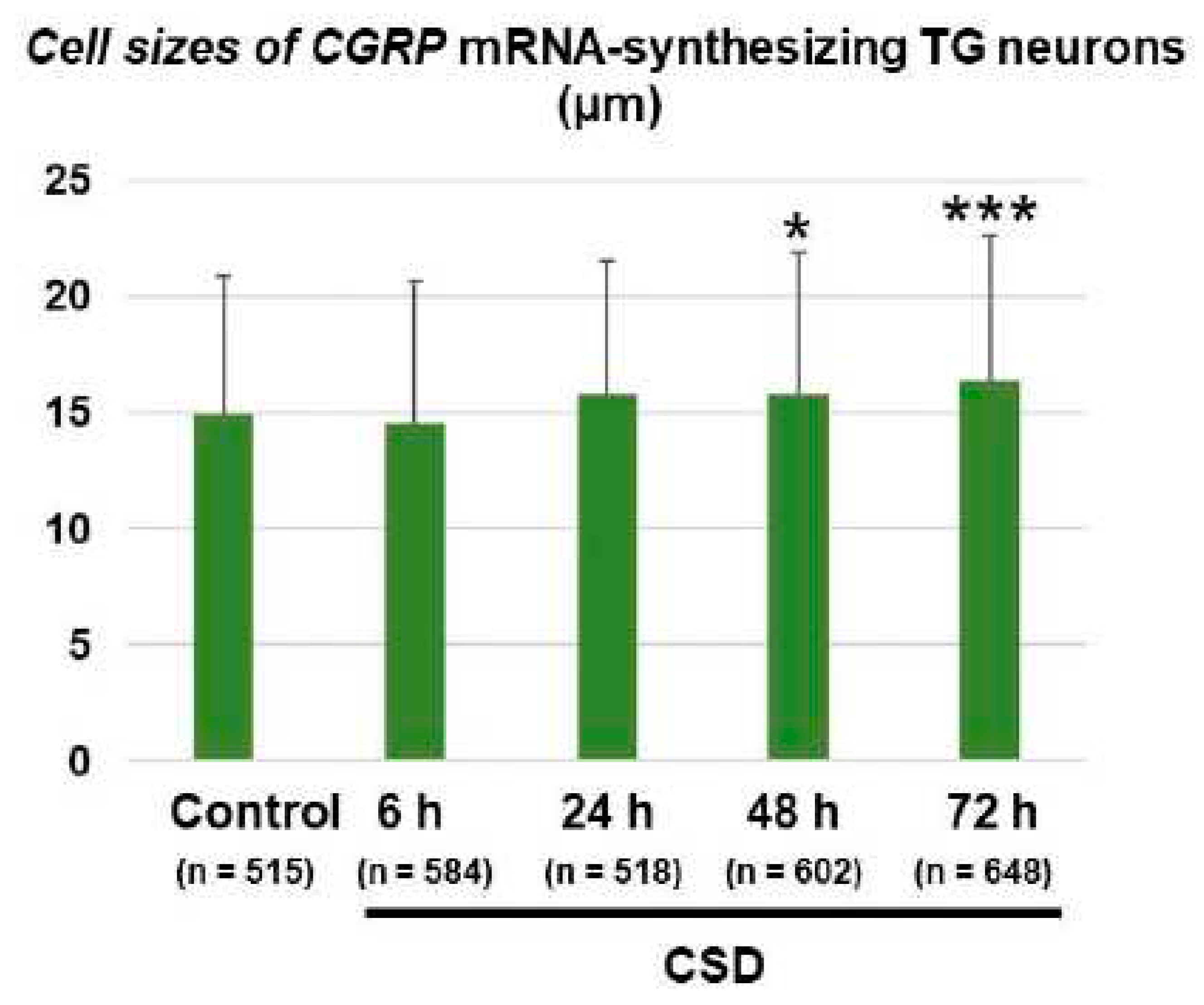

2.4. Cell Size Changes of CGRP mRNA-Synthesizing TG Neurons after CSD

The cell size of

CGRP mRNA-synthesizing TG neurons in the control mice was 14.9 ± 6.0 (mean ± SD) μm (n = 515). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) detected a significant effect of CSD on the cell size of

CGRP mRNA-synthesizing TG neurons (F

(4, 2862) = 8.838, P < 0.0001). As shown in

Figure 5, the cell sizes of

CGRP mRNA-synthesizing TG neurons in the 48 h post-CSD and 72 h post-CSD groups were significantly greater as compared to the control group (mean differences: 0.89 [95% CI: 0.00–1.77] μm, 48 h post-CSD group [n = 602] vs. control group [n = 515], P = 0.0492; 1.48 [95% CI: 0.61–2.35] μm, 72 h post-CSD group [n = 648] vs. control group [n = 515], P = 0.0001; Dunnett’s multiple comparison test). In comparison, there were no significant differences in the cell sizes of

β-actin mRNA-synthesizing TG neurons between the control and 72 h post-CSD groups (19.29 ± 5.14 [mean ± SD] μm in the control group vs. 19.59 ± 5.40 [mean ± SD] μm in the 72 h post-CSD group, P = 0.5699, unpaired Student’s t-test, n = 200 in each group). In the control group,

CGRP mRNA-synthesizing TG neurons were significantly smaller than

β-actin mRNA-synthesizing TG neurons (mean difference: -4.37 [95% CI: -5.32 to -3.43] µm, P = 0.0105, unpaired Student’s t-test).

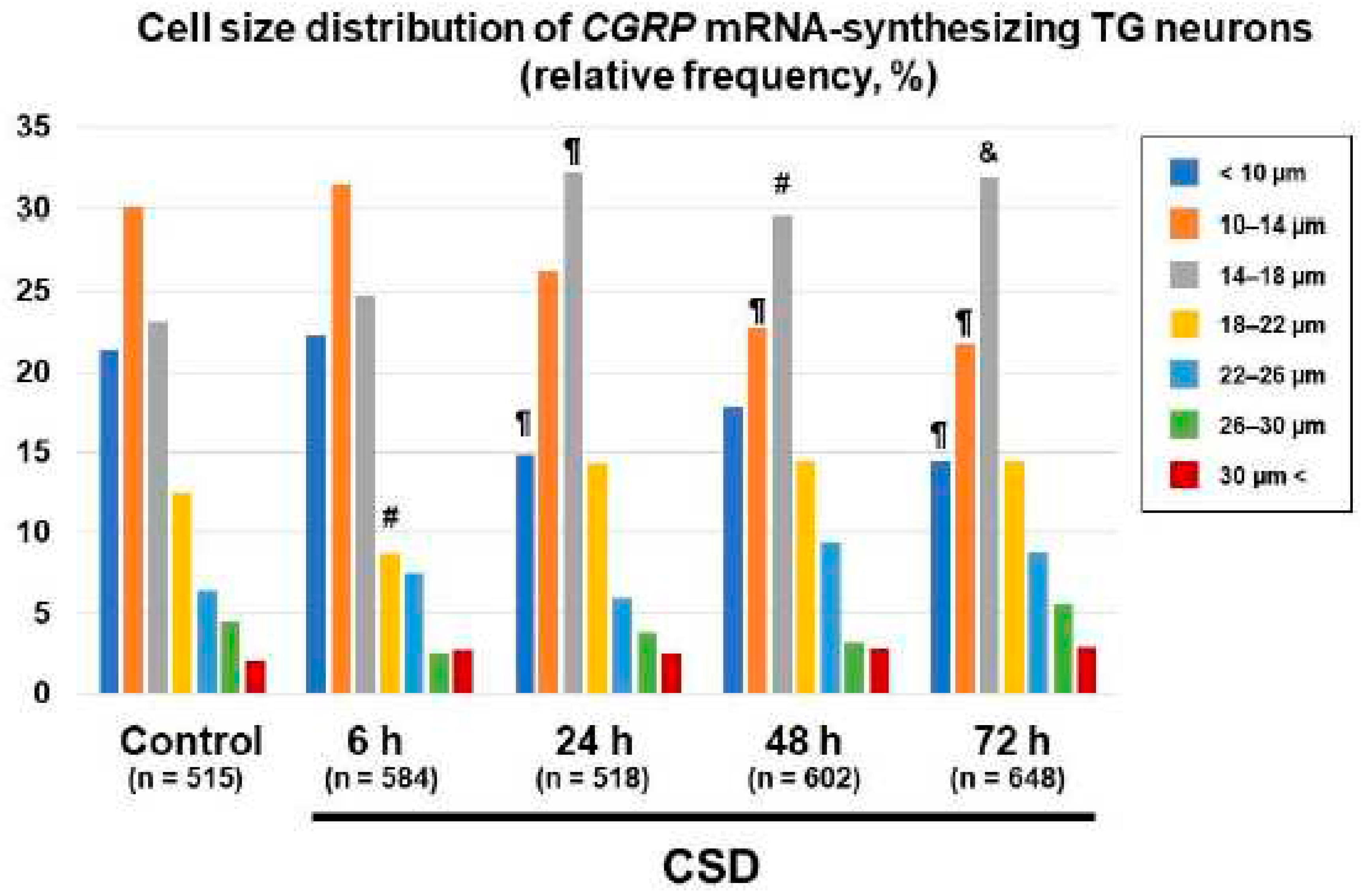

2.5. Changes in Cell Size Distributions of CGRP mRNA-Synthesizing TG Neurons after CSD

We next explored the effect of CSD on the cell size distribution of

CGRP mRNA-synthesizing TG neurons. The proportions of

CGRP mRNA-synthesizing TG neurons bearing cell diameters less than 10 μm were significantly reduced in the 24 h post-CSD and 72 h post-CSD groups as compared to the control group (P = 0.0067, 24 h post-CSD group vs. control group; P = 0.0023, 72 h post-CSD group vs. control group, chi-square test,

Figure 6). The proportions of

CGRP mRNA-synthesizing TG neurons bearing cell diameters 10–14 μm were significantly less in the 48 h post-CSD and 72 h post-CSD groups than in the control group (P = 0.0054 in the 24 h post-CSD group and P = 0.0012 in the 72 h post-CSD group, chi-square test,

Figure 6). On the other hand, we found significantly greater proportions of

CGRP mRNA-synthesizing TG neurons bearing cell diameters 14–18 μm in the 24 h post-CSD, 48 h post-CSD, and 72 h post-CSD groups than in the control group (P = 0.001 in the 24 h post-CSD group, P = 0.0148 in the 48 h post-CSD group, and P = 0.0009 in the 72 h post-CSD group, chi-square test,

Figure 6). The proportion of

CGRP mRNA-synthesizing TG neurons bearing cell diameters 18–22 μm was significantly less in the 6 h post-CSD group than in the control group (P = 0.0459, chi-square test,

Figure 6).

3. Discussion

The present study showed that CSD induced in the left cerebral hemisphere did not cause any significant change in the cell density of CGRP mRNA-synthesizing TG neurons on the ipsilateral side for up to 72 h. However, CGRP mRNA-synthesizing TG neurons in the 48 h and 72 h post-CSD groups were significantly larger than those in the control group. This phenomenon was not attributable to cell swelling, because we did not find any change in the cell size of β-actin mRNA-synthesizing TG neurons in the sections prepared from the same TG tissue. Of note, our cell size distribution analysis revealed that CSD induced a shift of the TG neurons with the greatest CGRP mRNA production toward a larger population. Plus, it merits a mention that we adopted a relatively noninvasive CSD induction method in the present study.

Although CGRP is a

bona fide therapeutic target for migraine, it remains largely unknown whether CSD may change the expression status of this neuropeptide in the nervous system. In rat CSD experiments, RT-PCR assays demonstrated increased

CGRP mRNA expression in the ipsilateral cerebral cortex [

28] and the amygdala [

29,

30]. Moreover, CSD was found to increase the amount of CGRP at the peptide level in the ipsilateral cerebral cortex [

28]. Intriguingly, the CGRP receptor antagonist, olcegepant, reduced the occurrence of CSD [

31], which suggests that a vicious cycle can be formed between CSD and CGRP release. Much less is known about the effect of CSD on CGRP production and release in TG tissue. Recurrent CSD over 90 min led to an increase in CGRP-immunoreactive neurons in TG tissue ipsilateral to CSD induction [

32]. In accord, Yisarakun et al. [

33] reported that the induction of CSD significantly increased the average percentage of total CGRP-immunoreactive neurons as compared to the control groups in TG tissue ipsilateral to CSD induction at 2 h in the absence of

CGRP mRNA upregulation. However, the information about the effect of CSD on CGRP expression in TG tissue during the post-CSD period up to 72 h, which is considered as the headache phase in migraine attacks, has never been reported so far. Our study has provided this missing information by focusing on the critical period of migraine attacks. From the technical viewpoint, it is difficult to judge whether increased signals in immunostaining reflect increased production or intracellular accumulation due to impaired release. Although RT-PCR is a gold standard method for quantifying mRNA expression levels, it cannot clarify the cell types responsible for the mRNA synthesis. Importantly, our ISH data have elucidated the populations of TG neurons engaged in de novo

CGRP mRNA synthesis. In TG tissue, CGRP is known to be expressed predominantly in small diameter neurons with very thin unmyelinated nerve fibers [

34,

35,

36,

37], which is consistent with our finding. Meanwhile. the CGRP receptor components, CLR and RAMP1, are expressed mainly in the larger neurons [

36,

37]. Consequently, under the normal circumstance, there is little coexpression of CGRP with the CGRP receptor with a paracrine action of CGRP operative [

38]. We found that CSD induced an upward shift of

CGRP mRNA-synthesizing TG neuron size. This finding raises the possibility that CSD may increase the occurrence of autocrine CGRP action, thus leading to higher exposure of the CGRP receptor to its ligand. Although the clinical implications of this novel finding remain elusive, we speculate that such conversion to the autocrine mechanism may contribute to migraine prolongation/recurrence and/or blunt the effectiveness of CGRP-targeted therapy.

There are several limitations to the present study. First, we used a CSD-based model, which is suitable for studying the disease state associated with migraine with aura. Hence, our findings may not be extrapolated to patients with migraine without aura. Second, we used only male mice to circumvent the potential effects of the menstrual cycle on the elicitability of CSD [

39]. Because migraine is three times more common in women than in men [

40], our data may not be applicable to female patients with migraine. Third, we analyzed TG neurons universally in our ISH experiment, because it was hard for us to identify the exact trigeminal territory to which each of the examined TG neurons belonged. The innervation of trigeminal fibers to the cerebral vasculature is known to vary among the trigeminal subdivisions, with the ophthalmic division being responsible for the greatest vascular innervation [

41]. Hence, if we had examined TG neurons in each subdivision individually, we could have obtained more significant data. Lastly, unlike RT-PCR, our ISH experiments were not able to provide information about the total production of

CGRP mRNA. Besides, because this is purely an in situ hybridization study, no data were available on the amount of CGRP at the peptide level or CGRP release for reference.

Despite these limitations, the present study provides an important novel insight into the effect of CSD on the status of de novo CGRP mRNA synthesis in TG neurons. In particular, the CSD-induced shift of TG neuronal populations engaging in CGRP mRNA synthesis is a novel finding that may have relevance to disease activity and therapeutic response especially in cases of migraine with aura.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

The present study was approved by the Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee of Keio University (No. 14084). All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the institution-approved protocols and EC Directive 86/609/EEC for animal experiments. Male C57BL/6 mice aged 8–10 weeks were purchased from CLEA Japan Inc. (Fujinomiya, Japan). A total of 15 mice (body weight: 25.1 ± 0.8 [mean ± SD]) were used for the present study. We failed in extracting TG tissue after perfusion fixation in one animal. Hence, 14 out of the 15 mice were analyzed for the study. They were housed in an ambient specific-pathogen-free condition with a 12-h light/dark cycle and given food and water ad libitum.

4.2. CSD Induction

Under isoflurane anesthesia (1–2%), the mouse head was fixed in a stereotaxic apparatus. Systemic anesthesia was maintained using an anesthesia unit (model 410; Univentor Ltd., Zejtun, Malta). Rectal temperature was maintained at approximately 37 °C using a thermocontroller-regulated heating-pad (BWT-100; Bioresearch Center Co., Ltd., Nagoya, Japan).

CSD was induced as described elsewhere [

42]. Briefly, after a midline incision, the scalp was carefully reflected for skull exposure. Part of the exposed skull was thinned (0.5 mm in diameter) using a dental drill at the position 2 mm lateral and 4 mm posterior to bregma on the left side (

Figure 1A). CSD was induced in the left hemisphere by placing a cotton ball soaked with 1 M KCl solution over the thinned skull at 2 mm lateral and 4 mm posterior to bregma. In all cases, CSD could be induced five times over 20–30 min (Figure. 1B). After the occurrence of five CSD episodes was confirmed using a laser Doppler flowmeter (ALF 21, Advance Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) set at 2 mm lateral and 2 mm posterior to bregma on each side, the KCl-soaked cotton ball was removed and the site washed with isotonic NaCl. CSD was considered to be induced when a characteristic deflection appeared only on the side ipsilateral to KCl application in the laser Doppler flowmeter recording (

Figure 1B). Continuous recordings of rCBF were stored on a multi-channel recorder (PowerLab 8/30; ADInstruments, Ltd., Sydney, Australia.), and LabChart software (ADInstruments, Ltd.) was used for off-line analysis. We confirmed that intraoperative hemodynamic parameters (heart rate [bpm] and systolic blood pressure [mmHg]) were within physiological ranges (data not shown).

4.3. TG Tissue Excision

At the timepoints described in

Figure 2, mice were euthanized with excess isoflurane. Thereafter, they were subjected to transcardial perfusion with saline followed by a fixative specially designed for in situ hybridization (ISH) (G-fix, Nippon Genetics Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). TG tissue ipsilateral to CSD induction was carefully excised from the skull, and stored in the same fixative at 4°C. TG tissue obtained from untreated mice served as control samples. The fixed tissue samples were embedded in paraffin on CT-Pro20 (Genostaff Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) using G-Nox (Genostaff Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) as a less toxic organic solvent for xylene, and processed as 6 µm-thick sections.

4.4. Mouse TG ISH

ISH was performed with an ISH Reagent Kit (Genostaff Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Tissue sections were deparaffined with G-Nox (Genostaff Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), and rehydrate through ethanol series and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The sections were fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF) for 30 min at 37°C and washed in distilled water, placed in 0.2% HCl for 10 min at 37°C, washed in PBS, treated with 4 µg/ml Proteinase K (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Co., Osaka, Japan) in PBS for 10 min at 37°C and washed in PBS, then placed within a coplin jar containing 1x G-Wash (Genostaff Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), equal to 1x SSC (3M NaCl, 0.3M sodium citrate). The targeted sequence for designing the mouse CGRP mRNA ISH probe was as follows;

CGRP:5’-gaaaggctgatgaaagacacatatatttgcatccttcttagtattgaaaaacccttctccctttgacaggagctaaagctaagtgcagaataagttgcctattgtgcatcgtgttgtatgtgactctgtatccaataaacatgacagcatggttctggcttatctggtagcaaatatggtccccataaaccatcctgttgatgttgatgactctgctaaacctcaaggggatatgaaacactgcctcttgctcttctggggacacatggtaa-3’.

ISH for mouse β-actin mRNA was performed using MP-A-002(Genostaff Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). Hybridization was carried out with the probes (250ng/ml) in G-Hybo-L (Genostaff Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) for 16 h at 60°C. After the hybridization, the sections were washed 3 times with 50% formamide in 2x G-Wash for 30min at 50°C, and 5 times in TBST (0.1% Tween20 in TBS) at room temperature. After treatment with 1x G-Block (Genostaff Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) for 15 min at room temperature, the sections were incubated with anti-DIG AP conjugate (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) diluted 1:2000 with G-Block (diluted 1/50) in TBST for 1hr at room temperature. The sections were washed twice in TBST and then incubated in 100 mM NaCl, 50mM MgCl2, 0.1% Tween20, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 9.5. Visualization of mRNA detection was performed with NBT/BCIP Solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The sections were counterstained with Kernechtrot Stain Solution (Muto Pure Chemicals, Tokyo, Japan), and mounted with G-Mount (Genostaff Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), then Malinol (Muto Pure Chemicals, Tokyo, Japan). Randomly-selected TG sections obtained from each animal (N = 2 in control mice and N = 3 from CSD-subjected mice) were examined with a light microscope, and the numbers and cell diameters of TG neurons positive for CGRP mRNA were analyzed using the NDP.view2 software (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan) and Adobe Photoshop 2023 (San Jose, CA, USA) by an examiner blind to the identity of tissue sections. In the analysis of neuronal diameters, we measured the longest diameters of neurons whose nuclei were visible on the section.

4.5. Statistical Analyses

All numerical data are expressed as means with SD or 95% confidence intervals (CI). The normality of numerical data distributions was assessed by the D'Agostino and Pearson normality test. Between-group comparisons for CGRP mRNA-synthesizing TG neuronal density was performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test. Between-group comparisons for cell diameters of CGRP mRNA-synthesizing TG neurons were conducted using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Variance equality was evaluated by Bartlett’s test. In multiple comparisons, P values were adjusted for multiplicity. Between-group comparisons for cell diameters of β-actin mRNA-synthesizing TG neurons were conducted using Student’s t-test. Proportions of neuronal diameter distribution were evaluated using the chi-square test. P<0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Data were analysed using GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.; investigation, M.S., S.K., M.U., and T.T.; data analyses, M.S., M.U. and T.T.; writing, M.S.; visualization, M.S.; manuscript edition, M.S., M.U., T.T,, and J.N.; supervision, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant number 19K07849, to M.S.), a grant from the Takeda Science Foundation to M.S., and research grants from Pfizer Inc. (WS1878886), Nippon Zoki Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Kao Corporation to our research group. The APC of this paper was covered by a research grant from the Japanese Headache Society.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee of Keio University (No. 14084). All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the university-approved protocols and EC Directive 86/609/EEC for animal experiments.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Relevant data generated and/or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Steiner, T. J.; Stovner, L. J.; Jensen, R.; Uluduz, D.; Katsarava, Z.; Lifting The Burden: the Global Campaign against, H., Migraine remains second among the world's causes of disability, and first among young women: findings from GBD2019. J Headache Pain 2020, 21, (1), 137.

- Ashina, M., Migraine. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, (19), 1866-1876.

- Dreier, J. P.; Fabricius, M.; Ayata, C.; Sakowitz, O. W.; Shuttleworth, C. W.; Dohmen, C.; Graf, R.; Vajkoczy, P.; Helbok, R.; Suzuki, M.; Schiefecker, A. J.; Major, S.; Winkler, M. K.; Kang, E. J.; Milakara, D.; Oliveira-Ferreira, A. I.; Reiffurth, C.; Revankar, G. S.; Sugimoto, K.; Dengler, N. F.; Hecht, N.; Foreman, B.; Feyen, B.; Kondziella, D.; Friberg, C. K.; Piilgaard, H.; Rosenthal, E. S.; Westover, M. B.; Maslarova, A.; Santos, E.; Hertle, D.; Sanchez-Porras, R.; Jewell, S. L.; Balanca, B.; Platz, J.; Hinzman, J. M.; Luckl, J.; Schoknecht, K.; Scholl, M.; Drenckhahn, C.; Feuerstein, D.; Eriksen, N.; Horst, V.; Bretz, J. S.; Jahnke, P.; Scheel, M.; Bohner, G.; Rostrup, E.; Pakkenberg, B.; Heinemann, U.; Claassen, J.; Carlson, A. P.; Kowoll, C. M.; Lublinsky, S.; Chassidim, Y.; Shelef, I.; Friedman, A.; Brinker, G.; Reiner, M.; Kirov, S. A.; Andrew, R. D.; Farkas, E.; Guresir, E.; Vatter, H.; Chung, L. S.; Brennan, K. C.; Lieutaud, T.; Marinesco, S.; Maas, A. I.; Sahuquillo, J.; Dahlem, M. A.; Richter, F.; Herreras, O.; Boutelle, M. G.; Okonkwo, D. O.; Bullock, M. R.; Witte, O. W.; Martus, P.; van den Maagdenberg, A. M.; Ferrari, M. D.; Dijkhuizen, R. M.; Shutter, L. A.; Andaluz, N.; Schulte, A. P.; MacVicar, B.; Watanabe, T.; Woitzik, J.; Lauritzen, M.; Strong, A. J.; Hartings, J. A., Recording, analysis, and interpretation of spreading depolarizations in neurointensive care: Review and recommendations of the COSBID research group. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2017, 37, (5), 1595-1625. [CrossRef]

- Lauritzen, M.; Jorgensen, M. B.; Diemer, N. H.; Gjedde, A.; Hansen, A. J., Persistent oligemia of rat cerebral cortex in the wake of spreading depression. Ann Neurol 1982, 12, (5), 469-74.

- Olesen, J.; Friberg, L.; Olsen, T. S.; Iversen, H. K.; Lassen, N. A.; Andersen, A. R.; Karle, A., Timing and topography of cerebral blood flow, aura, and headache during migraine attacks. Ann Neurol 1990, 28, (6), 791-8. [CrossRef]

- Olesen, J.; Larsen, B.; Lauritzen, M., Focal hyperemia followed by spreading oligemia and impaired activation of rCBF in classic migraine. Ann Neurol 1981, 9, (4), 344-52. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Welch, K. M.; Aurora, S.; Vikingstad, E. M., Functional MRI-BOLD of visually triggered headache in patients with migraine. Arch Neurol 1999, 56, (5), 548-54. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, A. R.; Friberg, L.; Olsen, T. S.; Olesen, J., Delayed hyperemia following hypoperfusion in classic migraine. Single photon emission computed tomographic demonstration. Arch Neurol 1988, 45, (2), 154-9. [CrossRef]

- Bowyer, S. M.; Aurora, K. S.; Moran, J. E.; Tepley, N.; Welch, K. M., Magnetoencephalographic fields from patients with spontaneous and induced migraine aura. Ann Neurol 2001, 50, (5), 582-7. [CrossRef]

- Hadjikhani, N.; Sanchez Del Rio, M.; Wu, O.; Schwartz, D.; Bakker, D.; Fischl, B.; Kwong, K. K.; Cutrer, F. M.; Rosen, B. R.; Tootell, R. B.; Sorensen, A. G.; Moskowitz, M. A., Mechanisms of migraine aura revealed by functional MRI in human visual cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001, 98, (8), 4687-92. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Levy, D.; Noseda, R.; Kainz, V.; Jakubowski, M.; Burstein, R., Activation of meningeal nociceptors by cortical spreading depression: implications for migraine with aura. J Neurosci 2010, 30, (26), 8807-14. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Levy, D.; Kainz, V.; Noseda, R.; Jakubowski, M.; Burstein, R., Activation of central trigeminovascular neurons by cortical spreading depression. Ann Neurol 2011, 69, (5), 855-65. [CrossRef]

- Karatas, H.; Erdener, S. E.; Gursoy-Ozdemir, Y.; Lule, S.; Eren-Kocak, E.; Sen, Z. D.; Dalkara, T., Spreading depression triggers headache by activating neuronal Panx1 channels. Science 2013, 339, (6123), 1092-5. [CrossRef]

- Carneiro-Nascimento, S.; Levy, D., Cortical spreading depression and meningeal nociception. Neurobiol Pain 2022, 11, 100091. [CrossRef]

- Ayata, C., Pearls and pitfalls in experimental models of spreading depression. Cephalalgia 2013, 33, (8), 604-13. [CrossRef]

- Mayberg, M.; Langer, R. S.; Zervas, N. T.; Moskowitz, M. A., Perivascular meningeal projections from cat trigeminal ganglia: possible pathway for vascular headaches in man. Science 1981, 213, (4504), 228-30. [CrossRef]

- Ashina, M.; Hansen, J. M.; Do, T. P.; Melo-Carrillo, A.; Burstein, R.; Moskowitz, M. A., Migraine and the trigeminovascular system-40 years and counting. Lancet Neurol 2019, 18, (8), 795-804. [CrossRef]

- Edvinsson, L.; Haanes, K. A.; Warfvinge, K.; Krause, D. N., CGRP as the target of new migraine therapies - successful translation from bench to clinic. Nat Rev Neurol 2018, 14, (6), 338-350. [CrossRef]

- Buzzi, M. G.; Carter, W. B.; Shimizu, T.; Heath, H., 3rd; Moskowitz, M. A., Dihydroergotamine and sumatriptan attenuate levels of CGRP in plasma in rat superior sagittal sinus during electrical stimulation of the trigeminal ganglion. Neuropharmacology 1991, 30, (11), 1193-200.

- Messlinger, K.; Hanesch, U.; Kurosawa, M.; Pawlak, M.; Schmidt, R. F., Calcitonin gene related peptide released from dural nerve fibers mediates increase of meningeal blood flow in the rat. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 1995, 73, (7), 1020-4. [CrossRef]

- Eltorp, C. T.; Jansen-Olesen, I.; Hansen, A. J., Release of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) from guinea pig dura mater in vitro is inhibited by sumatriptan but unaffected by nitric oxide. Cephalalgia 2000, 20, (9), 838-44. [CrossRef]

- Bullock, C. M.; Wookey, P.; Bennett, A.; Mobasheri, A.; Dickerson, I.; Kelly, S., Peripheral calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor activation and mechanical sensitization of the joint in rat models of osteoarthritis pain. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014, 66, (8), 2188-200. [CrossRef]

- Chatchaisak, D.; Connor, M.; Srikiatkhachorn, A.; Chetsawang, B., The potentiating effect of calcitonin gene-related peptide on transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 activity and the electrophysiological responses of rat trigeminal neurons to nociceptive stimuli. J Physiol Sci 2018, 68, (3), 261-268. [CrossRef]

- Cornelison, L. E.; Hawkins, J. L.; Durham, P. L., Elevated levels of calcitonin gene-related peptide in upper spinal cord promotes sensitization of primary trigeminal nociceptive neurons. Neuroscience 2016, 339, 491-501. [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S.; Johnson, K. W.; Ossipov, M. H.; Aurora, S. K., CGRP and the Trigeminal System in Migraine. Headache 2019, 59, (5), 659-681. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Ren, Y.; Xu, X.; Zou, X.; Fang, L.; Lin, Q., Sensitization of primary afferent nociceptors induced by intradermal capsaicin involves the peripheral release of calcitonin gene-related Peptide driven by dorsal root reflexes. J Pain 2008, 9, (12), 1155-68. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hoff, A. O.; Wimalawansa, S. J.; Cote, G. J.; Gagel, R. F.; Westlund, K. N., Arthritic calcitonin/alpha calcitonin gene-related peptide knockout mice have reduced nociceptive hypersensitivity. Pain 2001, 89, (2-3), 265-73. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tye, A. E.; Zhao, J.; Ma, D.; Raddant, A. C.; Bu, F.; Spector, B. L.; Winslow, N. K.; Wang, M.; Russo, A. F., Induction of calcitonin gene-related peptide expression in rats by cortical spreading depression. Cephalalgia 2019, 39, (3), 333-341. [CrossRef]

- Bu, F.; Yuan, M.; Ma, D.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, M., Inhibition of NR2A reduces calcitonin gene-related peptide gene expression induced by cortical spreading depression in rat amygdala. Neuropeptides 2020, 84, 102097. [CrossRef]

- Volobueva, M. N.; Suleymanova, E. M.; Smirnova, M. P.; Bolshakov, A. P.; Vinogradova, L. V., A Single Episode of Cortical Spreading Depolarization Increases mRNA Levels of Proinflammatory Cytokines, Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide and Pannexin-1 Channels in the Cerebral Cortex. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 24, (1). [CrossRef]

- Tozzi, A.; de Iure, A.; Di Filippo, M.; Costa, C.; Caproni, S.; Pisani, A.; Bonsi, P.; Picconi, B.; Cupini, L. M.; Materazzi, S.; Geppetti, P.; Sarchielli, P.; Calabresi, P., Critical role of calcitonin gene-related peptide receptors in cortical spreading depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, (46), 18985-90. [CrossRef]

- Won, L.; Kraig, R. P., Insulin-like growth factor-1 inhibits spreading depression-induced trigeminal calcitonin gene related peptide, oxidative stress & neuronal activation in rat. Brain Res 2020, 1732, 146673. [CrossRef]

- Yisarakun, W.; Chantong, C.; Supornsilpchai, W.; Thongtan, T.; Srikiatkhachorn, A.; Reuangwechvorachai, P.; Maneesri-le Grand, S., Up-regulation of calcitonin gene-related peptide in trigeminal ganglion following chronic exposure to paracetamol in a CSD migraine animal model. Neuropeptides 2015, 51, 9-16. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S. H.; Tew, J. M.; McLean, J. H.; Shipley, M. T., Cerebral arterial innervation by nerve fibers containing calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP): I. Distribution and origin of CGRP perivascular innervation in the rat. J Comp Neurol 1988, 271, (3), 435-44. [CrossRef]

- Nozaki, K.; Uemura, Y.; Okamoto, S.; Kikuchi, H.; Mizuno, N., Origins and distribution of cerebrovascular nerve fibers showing calcitonin gene-related peptide-like immunoreactivity in the major cerebral artery of the dog. J Comp Neurol 1990, 297, (2), 219-26. [CrossRef]

- Eftekhari, S.; Warfvinge, K.; Blixt, F. W.; Edvinsson, L., Differentiation of nerve fibers storing CGRP and CGRP receptors in the peripheral trigeminovascular system. J Pain 2013, 14, (11), 1289-303.

- Eftekhari, S.; Salvatore, C. A.; Johansson, S.; Chen, T. B.; Zeng, Z.; Edvinsson, L., Localization of CGRP, CGRP receptor, PACAP and glutamate in trigeminal ganglion. Relation to the blood-brain barrier. Brain Res 2015, 1600, 93-109. [CrossRef]

- Melo-Carrillo, A.; Strassman, A. M.; Nir, R. R.; Schain, A. J.; Noseda, R.; Stratton, J.; Burstein, R., Fremanezumab-A Humanized Monoclonal Anti-CGRP Antibody-Inhibits Thinly Myelinated (Adelta) But Not Unmyelinated (C) Meningeal Nociceptors. J Neurosci 2017, 37, (44), 10587-10596.

- Ebine, T.; Toriumi, H.; Shimizu, T.; Unekawa, M.; Takizawa, T.; Kayama, Y.; Shibata, M.; Suzuki, N., Alterations in the threshold of the potassium concentration to evoke cortical spreading depression during the natural estrous cycle in mice. Neurosci Res 2016, 112, 57-62. [CrossRef]

- van Casteren, D. S.; Kurth, T.; Danser, A. H. J.; Terwindt, G. M.; MaassenVanDenBrink, A., Sex Differences in Response to Triptans: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Neurology 2021, 96, (4), 162-170.

- White, T. G.; Powell, K.; Shah, K. A.; Woo, H. H.; Narayan, R. K.; Li, C., Trigeminal Nerve Control of Cerebral Blood Flow: A Brief Review. Front Neurosci 2021, 15, 649910. [CrossRef]

- Takizawa, T.; Qin, T.; Lopes de Morais, A.; Sugimoto, K.; Chung, J. Y.; Morsett, L.; Mulder, I.; Fischer, P.; Suzuki, T.; Anzabi, M.; Bohm, M.; Qu, W. S.; Yanagisawa, T.; Hickman, S.; Khoury, J. E.; Whalen, M. J.; Harriott, A. M.; Chung, D. Y.; Ayata, C., Non-invasively triggered spreading depolarizations induce a rapid pro-inflammatory response in cerebral cortex. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2020, 40, (5), 1117-1131. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).