Submitted:

25 April 2023

Posted:

02 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

1. Study population

2. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing and Screening Confirmation for ESBL

3. Genomic DNA Extraction

4. Conventional singleplex-Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

5. Conventional Multiplex-Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

6. Agarose electrophoresis gel and visualization

7. Data management and analysis

3. Results

3.1. Population characteristics

3.1.1. Pathogen recovery

3.1.2. Prevalence of ESBL-E. coli

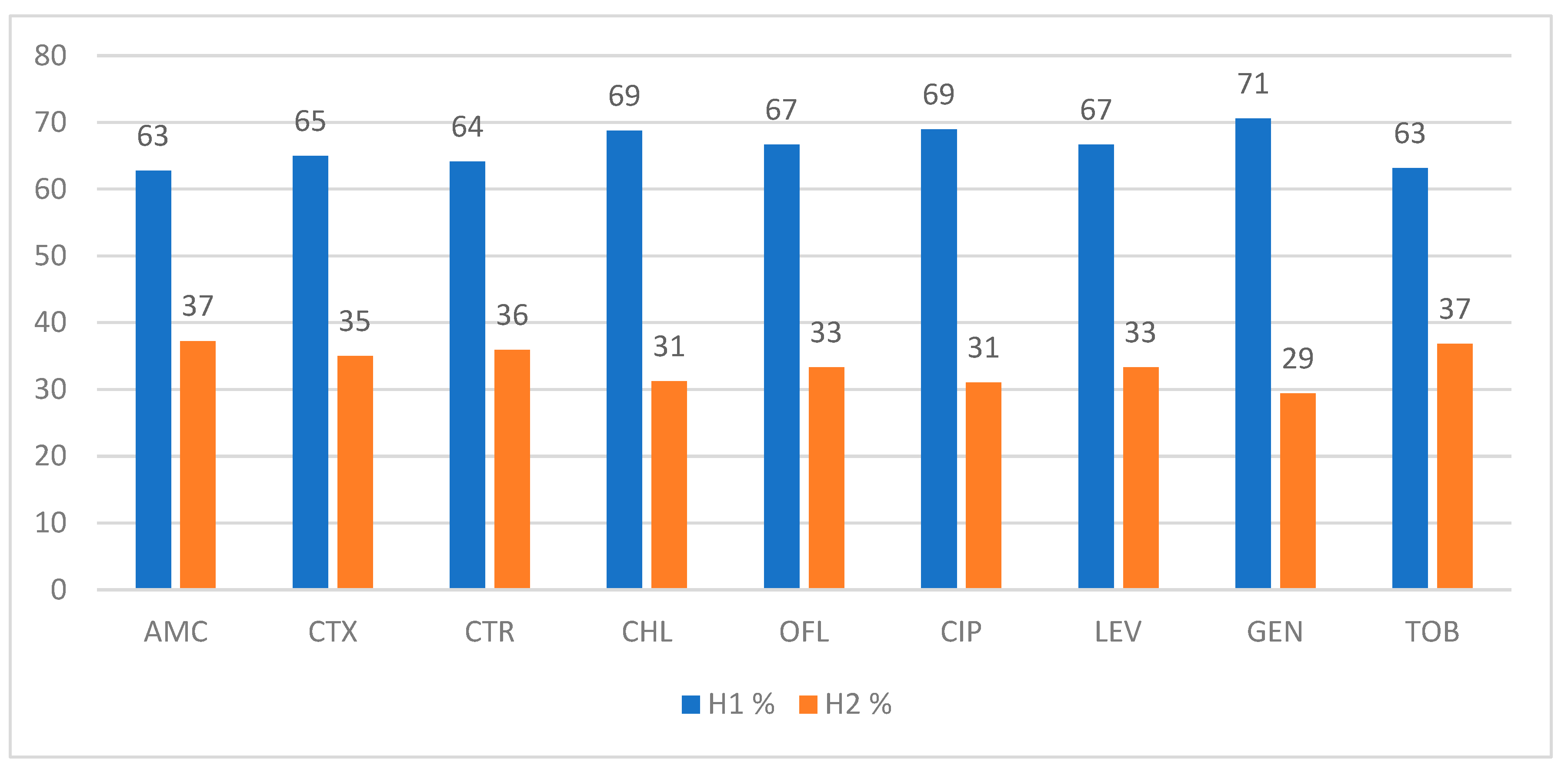

3.2. Antibiotic resistance profile of ESBL- E. coli

3.1.3. Multi-drug resistance and resistance patterns of ESBL-E. coli isolated from stool samples

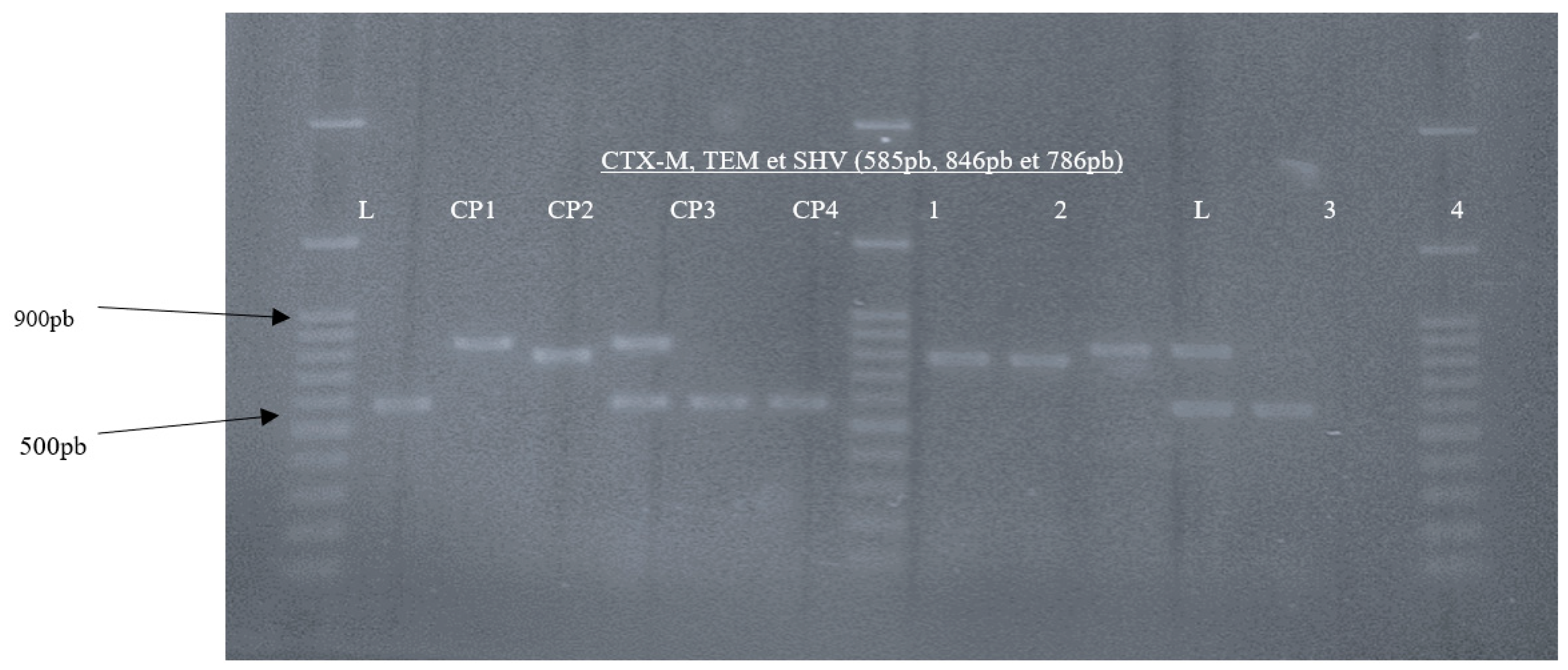

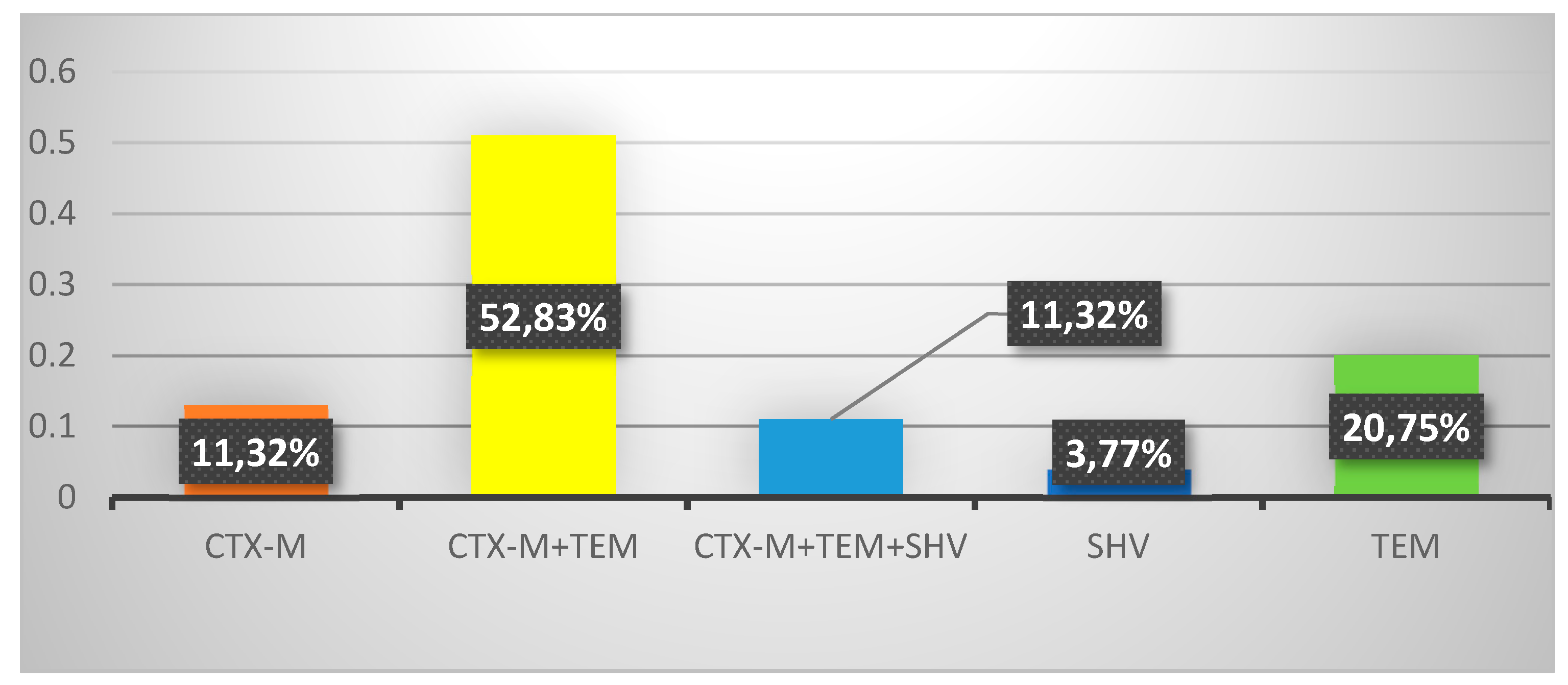

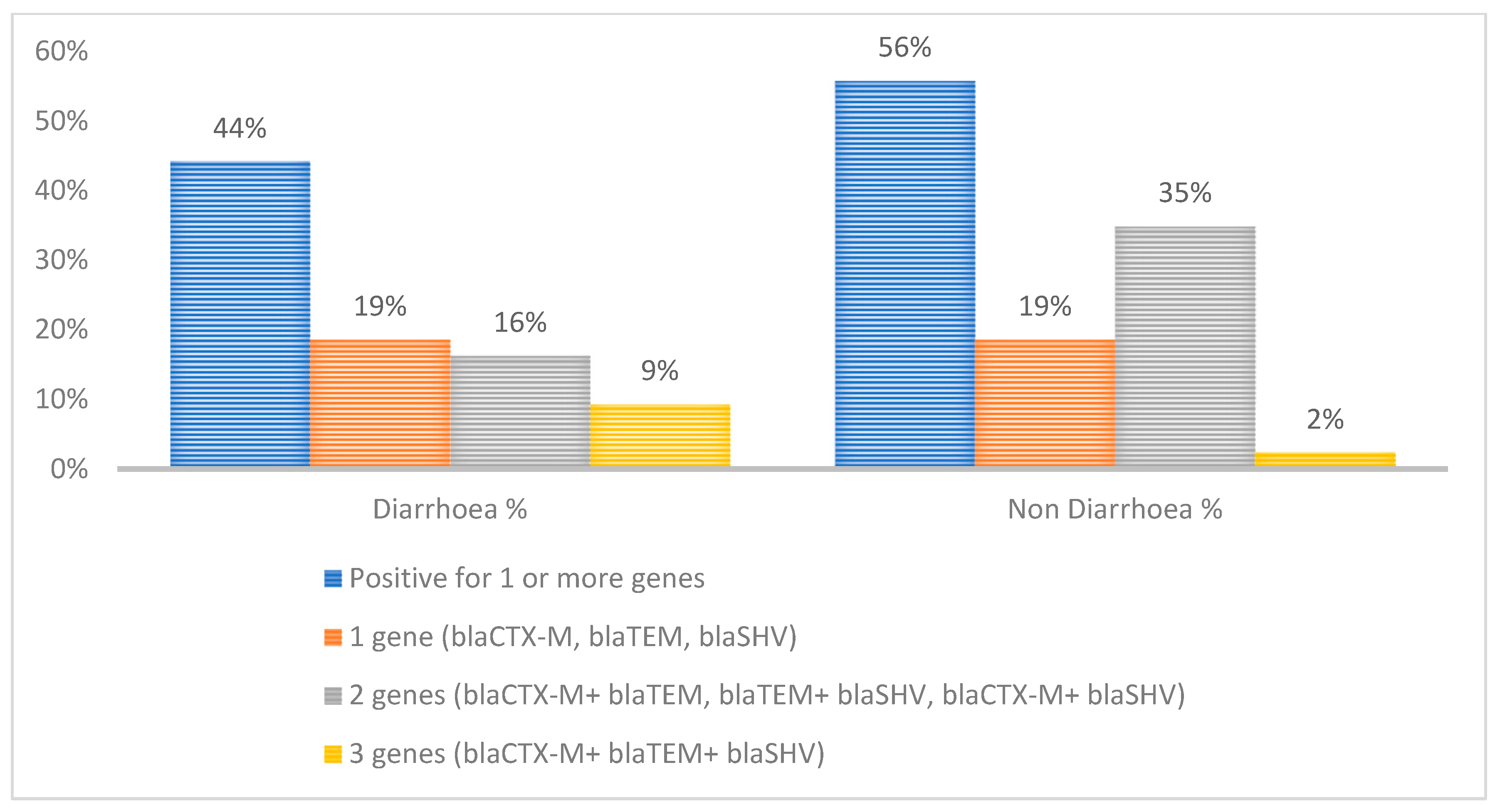

3.3. Genotypic resistance profiles

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bonkoungou, I.J.; Haukka, K.; Österblad, M.; Hakanen, A.J.; Traoré, A.S.; Barro, N.; et al. Bacterial and viral etiology of childhood diarrhea in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. BMC Pediatr. 2013, 13, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dembele, R.; Konate, A.; Traore, O.; Kabore, W.A.D.; Soulama, I.; Kagambega, A.; et al. Extended spectrum beta-lactamase and fluoroquinolone resistance genes among Escherichia coli and Salmonella isolates from children with diarrhea, Burkina Faso. BMC Pediatr. 2020, 20, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. The Top 10 Causes of Death. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death.

- Devleesschauwer, B.; Haagsma, A.; Mangen, J.; Lake, J.; Havelaar, H. The Global Burden of Foodborne Disease. Chapter 7; 2018; pp. 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Khoshvaght, H.; Haghi, F.; Zeighami, H. Extended spectrum betalactamase producing Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli from young children in Iran. GHFBB. 2014, 7, 131–136. [Google Scholar]

- Tawfick, M.M.; Elshamy, A.A.; Mohamed, K.T.; El Menofy, N.G. Gut Commensal Escherichia coli, a High-Risk Reservoir of Transferable Plasmid-Mediated Antimicrobial Resistance Traits. Infect Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 1077–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, M.A.; Yin, X.; Lepp, D.; Laing, C.; Ziebell, K.; Talbot, G.; et al. Genomic Analysis of Third Generation Cephalosporin Resistant Escherichia coli from Dairy Cow Manure. Vet Sci. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koirala, S.; Khadka, S.; Sapkota, S.; Sharma, S.; Khanal, S.; Thapa, A.; et al. Prevalence of CTX-M β-Lactamases Producing Multidrug Resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae among Patients Attending Bir Hospital, Nepal. BioMed Res Inter. 2021, 2021, 9958294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, H.M.; Alnaiemi, N.; Reuland, E.A.; Wintermans, B.B.; Koek, A.; Abdelwahab, A.M.; et al. Fecal carriage of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase- and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Egyptian patients with community-onset gastrointestinal complaints: a hospital -based cross-sectional study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2017, 6, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arhoune, B.; Oumokhtar, B.; Hmami, F.; Barguigua, A.; Timinouni, M.; El Fakir, S.; et al. Rectal carriage of extended-spectrum β-lactamase- and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae among hospitalised neonates in a neonatal intensive care unit in Fez, Morocco. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2017, 8, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikoumba, A.C.; Onanga, R.; Boundenga, L.; Bignoumba, M.; Ngoungou, E.B.; Godreuil, S. Prevalence and Characterization of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in Major Hospitals in Gabon. Microbial Drug Resist. 2021, 27, 1525–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tola, M.A.; Abera, N.A.; Gebeyehu, Y.M.; Dinku, S.F.; Tullu, K.D. High prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae fecal carriage among children under five years in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PloSone. 2021, 16, e0258117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magoué, C.L.; Melin, P.; Gangoué-Piéboji, J.; Okomo Assoumou, M.C.; Boreux, R.; De Mol, P. Prevalence and spread of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Ngaoundere, Cameroon. CMI. 2013, 19, E416–E20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Société Française de Microbiologie, C.E. Société Française de Microbiologie Ed: Paris, France, 2021; pp. 1–188.

- Zemtsa, R.J.; Noubom, M.; Founou, L.L.; Dimani, B.D.; Koudoum, P.L.; Mbossi, A.D.; et al. Multidrug-Resistant and Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase (ESBL) - Producing Enterobacterales Isolated from Carriage Samples among HIV Infected Women in Yaoundé, Cameroon. Pathogens. 2022, 11, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauß, L.M.; Dahms, C.; Becker, K.; Kramer, A.; Kaase, M.; Mellmann, A. Development and evaluation of a novel universal β-lactamase gene subtyping assay for blaSHV, blaTEM and blaCTX-M using clinical and livestock-associated E. coli. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014, 70, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batchelor, M.; Hopkins, K.; Threlfall, E.; Clifton-Hadley, F.; Stallwood, A.; Davies, R.; et al. blaCTX-M genes in clinical Salmonella isolates recovered from humans in England and Wales from 1992 to 2003. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 1319–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saka, H.K.; García-Soto, S.; Dabo, N.T.; Lopez-Chavarrias, V.; Muhammad, B.; Ugarte-Ruiz, M.; et al. Molecular detection of extended spectrum β-lactamase genes in Escherichia coli clinical isolates from diarrhoeic children in Kano, Nigeria. PloS one. 2020, 15, e0243130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghighatpanah, M.; Mozaffari Nejad, A.S.; Mojtahedi, A.; Amirmozafari, N.; Zeighami, H. Detection of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) and plasmid-borne blaCTX-M and blaTEM genes among clinical strains of Escherichia coli isolated from patients in the north of Iran. J Glob antimicrob Resist. 2016, 7, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbamyah, E.E.L.; Toukam, M.; Assoumou, M.-C.O.; Smith, A.M.; Nkenfou, C.; Gonsu, H.K.; et al. Genotypic Diversity and Characterization of Quinolone Resistant Determinants from Enterobacteriaceae in Yaounde, Cameroon. OJMM. 2020, 10, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaumburg, F.; Alabi, A.; Kokou, C.; Grobusch, M.P.; Köck, R.; Kaba, H.; et al. High burden of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Gabon. JAC. 2013, 68, 2140–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wencewicz, T.A. Crossroads of Antibiotic Resistance and Biosynthesis. J Molecular Biol. 2019, 431, 3370–3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, H.M.; Alnaiemi, N.; Reuland, E.A.; Wintermans, B.B.; Koek, A.; Abdelwahab, A.M.; et al. Fecal carriage of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase- and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Egyptian patients with community-onset gastrointestinal complaints: a hospital -based cross-sectional study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2017, 6, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanheira, M.; Simner, P.J.; Bradford, P.A. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases: an update on their characteristics, epidemiology and detection. JAC-Antimicrob Resist. 2021, 3, dlab092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shitta, G.; Makanjuola, O.; Adefioye, O.; Olowe, O.A. Extended Spectrum Beta Lactamase, blaTEM,blaSHV and blaCTX-M, Resistance Genes in Community and Healthcare Associated Gram Negative Bacteria from Osun State, Nigeria. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2021, 21, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oli, A.N.; Akabueze, V.B.; Ezeudu, C.E.; Eleje, G.U.; Ejiofor, O.S.; Ezebialu, I.U.; et al. Bacteriology and Antibiogram of Urinary Tract Infection Among Female Patients in a Tertiary Health Facility in South Eastern Nigeria. J Open Microbiol. 2017, 11, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Targeted gene | Primer Name | Sequence (5’-3’) | Amplicon Size (bp) | Annealing Temperatures |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEM | TEM-F TEM-R |

CATTTCCGTGTCGCCCTTATTC CCAATGCTTAATCAGTGAGGC |

846 pb | 46.9°C | (16) (p. 712) |

| CTX-M | CTX-MU F CTX-MU R |

CGATGTGCAGTACCAGTAA TTAGTGACCAGAATCAGCGG |

585 pb | 46.9°C | (17) (p. 1319) |

| SHV | SHV-F SHV-R |

AGCCGCTTGAGCAAATTAAAC GTTGCCAGTGCTCGATCAGC |

786 pb | 46.9°C | (16) (p. 29) |

| Variables | Total n (%) | Positive E. coli n (%) |

Negative E. coli n (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 125 (100) | 84(67.2) | 41 (32.8) | ||

| Gender | Male | 63 (50.4) | 45 (57.53) | 18 (43.9) | 0.15 |

| Female | 62 (49.6) | 39 (46.43) | 23 (56.1) | ||

| Age | ˂ 1 year | 50 (40) | 28 (33.33) | 22 (53.66) | 0.09 |

| 1 – 3 years | 53 (42.4) | 40 (47.62) | 13 (31.71) | ||

| 3 -5 years | 22 (17.6) | 16 (19.05) | 6 (14.63) | ||

| Residence | Rural area | 54 (43.20) | 36 (42.86) | 18 (43.9) | 0.45 |

| Urban area | 71 (56.80) | 48 (57.14) | 23 (56.1) | ||

| Child's education level | Kindergarten | 18 (13.6) | 13 (15.48) | 5 (12.2) |

0.77 |

| Pre-nursery | 6 (4.8) | 3 (3.57) | 3 (7.32) | ||

| Nursery | 18 (14.4) | 13 (15.48) | 5 (9.76) | ||

| Primary | 7 (5.6) | 5 (5.95) | 2 (4.88) | ||

| Not applicable* | 77 (61.6) | 50 (59.52) | 27 (65.85) | ||

| Monthly income of parents (XAF) | ˂ 38500 | 69 (55.2) | 42 (50) | 27 (65.85) | 0.38 |

| 38500-100.000 | 31 ((24.8) | 23 (27.38) | 8 (19.51) | ||

| 100.000- 250.000 | 19 (15.2) | 14 (16.67) | 5 (12.2) | ||

| ˃250.000 | 6 (4.8) | 5 (5.95) | 1 (2.44) | ||

| Marital status of parents | Single | 30 (24) | 19 (22.62) | 11 (26.83) |

0.3 |

| Married | 95 (76) | 65 (77.38) | 30 (73.17) | ||

| Hospital | H1 | 85 (68) | 48 (57.14) | 37 (90.24) |

0.00005 |

| H2 | 40 (32) | 36 (42.86) | 4 (9.76) | ||

| Food consumptionhabits | |||||

| Yogourt | Yes | 83 (66.4) | 56 (66.67) | 27 (65.85) |

0.46 |

| No | 42 (33.6) | 28 (33.33) | 14 (34.15) | ||

| Eggs | Yes | 93 (74.4) | 65 (77.38) | 28 (68.29) |

0.14 |

| No | 32 (25.6) | 19 (22.62) | 13 (31.71) | ||

| Porridge | Yes | 89 (71.2) | 57 (67.86) | 32 (78.05) |

0.12 |

| No | 36 (28.8) | 27 (32.14) | 9 (21.95) | ||

| Natural Fruit Juice | Yes | 100 (80) | 66 (78.57) | 34 (82.93) |

0.29 |

| No | 25 (20) | 18 (21.43) | 7 (17.07) | ||

| Artificial juice | Yes | 59 (47.2) | 41 (48.81) | 18 (43.9) |

0.3 |

| No | 66 (52.8) | 43 (51.19) | 23 (56.1) | ||

| Breast milk | Yes | 53 (42.4) | 34 (40.48) | 19 (46.34) |

0.26 |

| No | 72 (57.6) | 50 (59.52) | 22 (54.66) | ||

| Artificial milk | Yes | 79 (63.2) | 55 (65.48) | 24 (58.54) |

0.22 |

| No | 46 (36.8) | 29 (34.52) | 17 (41.46) | ||

| Hygienic measures | |||||

| Disposable nappies | Yes | 86 (68.8) | 56 (66.67) | 30 (73.17) | 0.23 |

| No | 39 (31.2) | 28 (33.33) | 11 (26.83) | ||

| Hand washing of parents | Yes | 93 (74.4) | 64 (76.19) | 29 (70.73) | 0.25 |

| No | 32 (25.6) | 20 (23.81) | 12 (29.27) | ||

| Type of consumed water | Mineral | 70 (56) | 45 (53.57) | 25 (60.98) | 0.25 |

| Tap | 15 (12) | 11 (13.1) | 4 (9.76) | ||

| Drilling | 28 (22.4) | 21 (25) | 7 (17.07) | ||

| Source | 12 (9.6) | 7 (8.33) | 5 (12.2) | ||

| Cut finger nail (parents) | Yes | 93 (74.4) | 63 (75) | 30 (73.17) | 0.41 |

| No | 32 (25.6) | 21 (25) | 11 (26.83) | ||

| Clinical status | |||||

| Diarrhoea | Yes | 70 (56) | 39 (46.43) | 31 (75.61) |

0.001 |

| No | 55 (44) | 45 (53.57) | 10 (24.39) | ||

| Symptoms | Diarrhoea with others | 65 (52) | 36 (42.86) | 29 (70.73) |

0.006 |

| Only diarrhoea | 5 (4) | 3 (3.57) | 2 (4.88) | ||

| Other clinical signs without diarrhoea |

55 (44) |

45 (53.57) |

10 (24.39) |

||

| Antibiotic | Yes | 76 (60.8) | 51 (60.71) | 25 (60.98) |

0.49 |

| No | 49 (39.2) | 33 (39.29) | 16 (39.02) | ||

| Variables | Total n (%) | ESBL-Ec positive n (%) |

EBSL-Ec negative n (%) |

p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 84 (100) | 48 (57.14) | 36 (42.85) | 0.00 | ||

| Gender | Male | 45 (53.57) | 21 (43.75) | 24 (66.67) | 0.02 | |

| Female | 39 (46.43) | 27 (56.25) | 12 (33.33) | |||

| Age | ˂ 1 year | 28 (33.33) | 14 (29.17) | 14 (38.89) | 0.63 | |

| 1 – 3 years | 40 (47.62) | 24 (50) | 16 (44.44) | |||

| 3 -5 years | 16 (19.05) | 10 (20.83) | 6 (16.67) | |||

| Residence | Rural area | 36 (42.85) | 22 (45.83) | 14 (38.89) | 0.26 | |

| Urban area | 48 (57.14) | 26 (54.17) | 22 (61.11) | |||

| Child's education level | Kindergarten | 13 (15.48) | 7 (15.4) | 6 (16.67) | 0.98 | |

| Pre-nursery | 3 (3.57) | 3 (3.57) | 1 (2.78) | |||

| Nursery | 13 (15.48) | 13 (15.48) | 5 (13.89) | |||

| Primary | 5 (5.95) | 5 (5.95) | 2 (5.56) | |||

| Not applicable* | 50 (59.52) | 50 (59.52) | 22 (61.11) | |||

| Monthly income of parents (XAF) | ˂ 38500 | 42 (50) | 19 (39.58) | 23 (63.89) | 0.10 | |

| 38500-100.000 | 23 (27.38) | 17 (35.42) | 6 (16.67) | |||

| 100.000- 250.000 | 14 (16.67) | 8 (16.67) | 6 (16.67) | |||

| ˃250.000 | 5 (5.95) | 4 (8.33) | 1 (2.78) | |||

| Marital status of parents | Single | 19 (22.62) | 9 (18.75) | 10 (27.78) |

0.17 |

|

| Married | 65 (77.38) | 39 (81.25) | 26 (72.22) | |||

| Hospital | H1 | 48 (57.14) | 29 (60.42) | 19 (52.78) |

0.24 |

|

| H2 | 36 (42.86) | 19 (39.58) | 17 (47.22) | |||

| Food consumption habits | ||||||

| Yogourt | Yes | 56 (66.67) | 32 (66.67) | 24 (66.67) |

0.49 |

|

| No | 28 (33.33) | 16 (33.33) | 12 (33.33) | |||

| Porridge | Yes | 57 (67.86) | 34 (70.83) | 23 (63.89) |

0.25 |

|

| No | 27 (32.14) | 14 (29.17) | 13 (36.11) | |||

| Eggs | Yes | 65 (77.38) | 38 (79.17) | 27 (75) |

0.32 |

|

| No | 19 (22.62) | 10 (20.83) | 9 (25) | |||

| Natural Fruit Juice | Yes | 66 (78.57) | 39 (81.25) | 27 (75) |

0.25 |

|

| No | 18 (21.53) | 9 (9.75) | 9 (25) | |||

| Artificial juice | Yes | 41 (48.81) | 22 (45.83) | 19 (52.78) |

0.26 |

|

| No | 43 (51.19) | 26 (54.17) | 17 (47.22) | |||

| Breast milk | Yes | 34 (40.48) | 21 (56.25) | 13 (36.11) |

0.24 |

|

| No | 50 (59.52) | 27 (43.75) | 23 (63.89) | |||

| Artificial milk | Yes | 55 (65.48) | 29 (60.42) | 26 (72.22) |

0.13 |

|

| No | 29 (34.52) | 19 (39.58) | 10 (27.78) | |||

| Hygienic measures | ||||||

| Disposable nappies | Yes | 56 (66.67) | 35 (72.92) | 21 (58.33) | 0.08 | |

| No | 28 (33.33) | 13 (27.08) | 15 (41.67) | |||

| Hand washing | Yes | 64 (76.19) | 35 (72.92) | 29 (80.56) | 0.21 | |

| No | 20 (23.81) | 13 (27.08) | 7 (19.44) | |||

| Type of consumed water | Mineral | 39 (46.43) | 21 (43.75) | 18 (50) | 0.72 | |

| Tap | 11 (13.10) | 7 (14.58) | 4 (11.11) | |||

| Drilling | 27 (32.14) | 15 (31.25) | 12 (33.33) | |||

| Source | 7 (8.33) | 5 (10.42) | 2 (5.56) | |||

| Clinical status | ||||||

| Diarrhoea | Yes | 39 (46.43) | 20 (41.67) | 19 (52.78) |

0.16 |

|

| No | 45 (53.57) | 28 (58.33) | 17 (47.22) | |||

| Symptoms | Diarrhoea with others | 36 (42.86) | 18 (37.5) | 18 (50) |

0.51 |

|

| Only diarrhoea | 3 (3.57) | 2 (4.17) | 1 (2.78) | |||

| Other clinical signs without diarrhoea | 45 (53.57) | 28 (58.33) | 17 (47.22) | |||

| Antibiotic | Yes | 51 (60.71) | 34 (70.83) | 17 (47.22) |

0.01 |

|

| No | 33 (39.29) | 14 (29.17) | 19 (52.78) | |||

|

Antimicrobial Agents |

Overall N=90, n(%) |

Resistance, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESBL-Ec (n=53) |

Non-ESBL-Ec (n=37) |

||

| Amoxicillin/Clavulanic Acid | 87 (96.66) | 51 (96.22) | 36 (97.29) |

| Cefotaxime | 47 (52.22) | 40 (75.47) | 7 (18.91) |

| Ceftriaxone | 47 (52.22) | 39 (73.58) | 8 (21.62) |

| Chloramphenicol | 30 (34.48) | 16 (30.18) | 14 (37.83) |

| Ofloxacin | 53 (58.88) | 36 (67.92) | 17 (45.94) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 36 (40) | 29 (54.71) | 7 (18.91) |

| Levofloxacin | 40 (44.44) | 30 (56.6) | 10 (33.33) |

| Gentamicin | 27 (30) | 17 (32.07) | 10 (33.33) |

| Tobramycin | 34 (37.77) | 19 (35.84) | 15 (40.54) |

| Resistance patterns | Number of Antibiotics | Number of family of Antibiotics |

Number of Isolates (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMC-CHL-OFL | 3 |

3 |

1 (4.16) |

| AMC-OFL-CIP-GEN-TOB | 5 | 1 (4.16) | |

| AMC-CTX-CTR-CHL-OFL-LEV | 6 |

2 (8.33) | |

| AMC-CTX-CTR-OFL-GEN-TOB | 1 (4.16) | ||

| AMC-CTX-CTR-OFL-CIP-LEV-GEN |

7 |

1 (4.16) | |

| AMC-CTX-CTR-CHL-CIP-OFL-LEV | 2 (8.33) | ||

| AMC-CTX-CTR-OFL-CIP-LEV-TOB | 3 (12.5) | ||

| AMC-CTX-CTR-OFL-CIP-LEV-GEN-TOB | 8 | 4 (16.66) | |

| AMC-CHL-OFL-GEN | 4 |

4 |

1 (4.16) |

| AMC-CTX-CHL-CIP-OFL-LEV-TOB | 7 | 2 (8.33) | |

| AMC-CTX-CTR-CHL-OFL-GEN-TOB | 1 (4.16) | ||

| AMC-CTX-CTR-CHL-OFL-LEV-GEN->TOB |

8 |

1 (4.16) | |

| AMC-CTX-CTR-CHL-OFL-CIP-LEV-TOB | 2 (8.33) | ||

| AMC-CTX-CTR-CHL-OFL-CIP-LEV-GEN | 1 (4.16) | ||

| AMC-CTX-CTR-CHL-OFL-CIP-LEV-GEN-TOB | 9 | 2 (8.33) | |

| TOTAL | 25 (100) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).