Submitted:

30 April 2023

Posted:

01 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Lattice Boltzmann Method and its Parameters

2.2. Recalibration of Populations

2.2.1. Recalibration with

2.2.2. Recalibration with both and

2.2.3. Recalibration with a change in quadrature

2.2.4. Recalibration with the change of stencil

3. Grid Refinement Interface without Interpolation

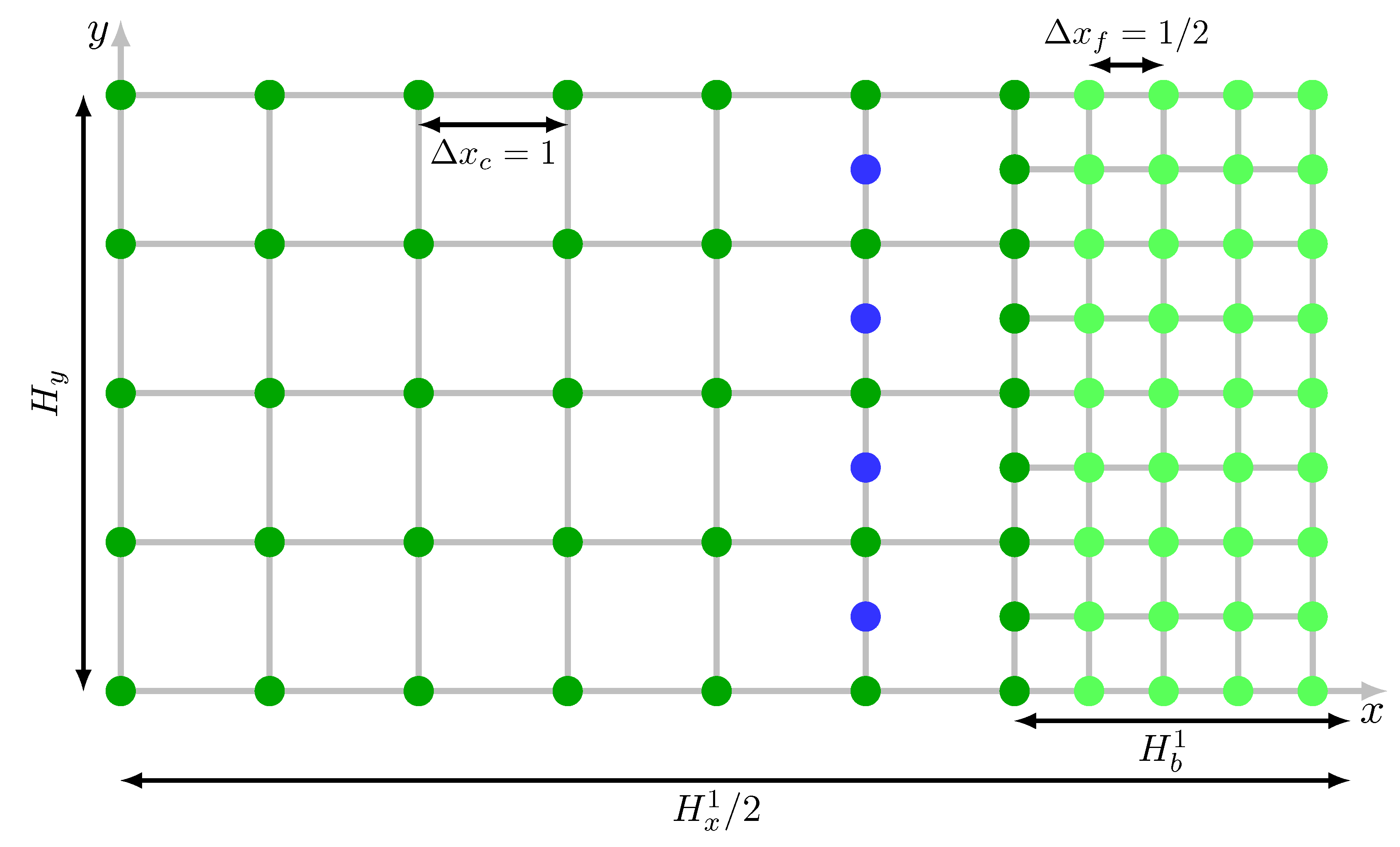

3.1. Grid Geometry

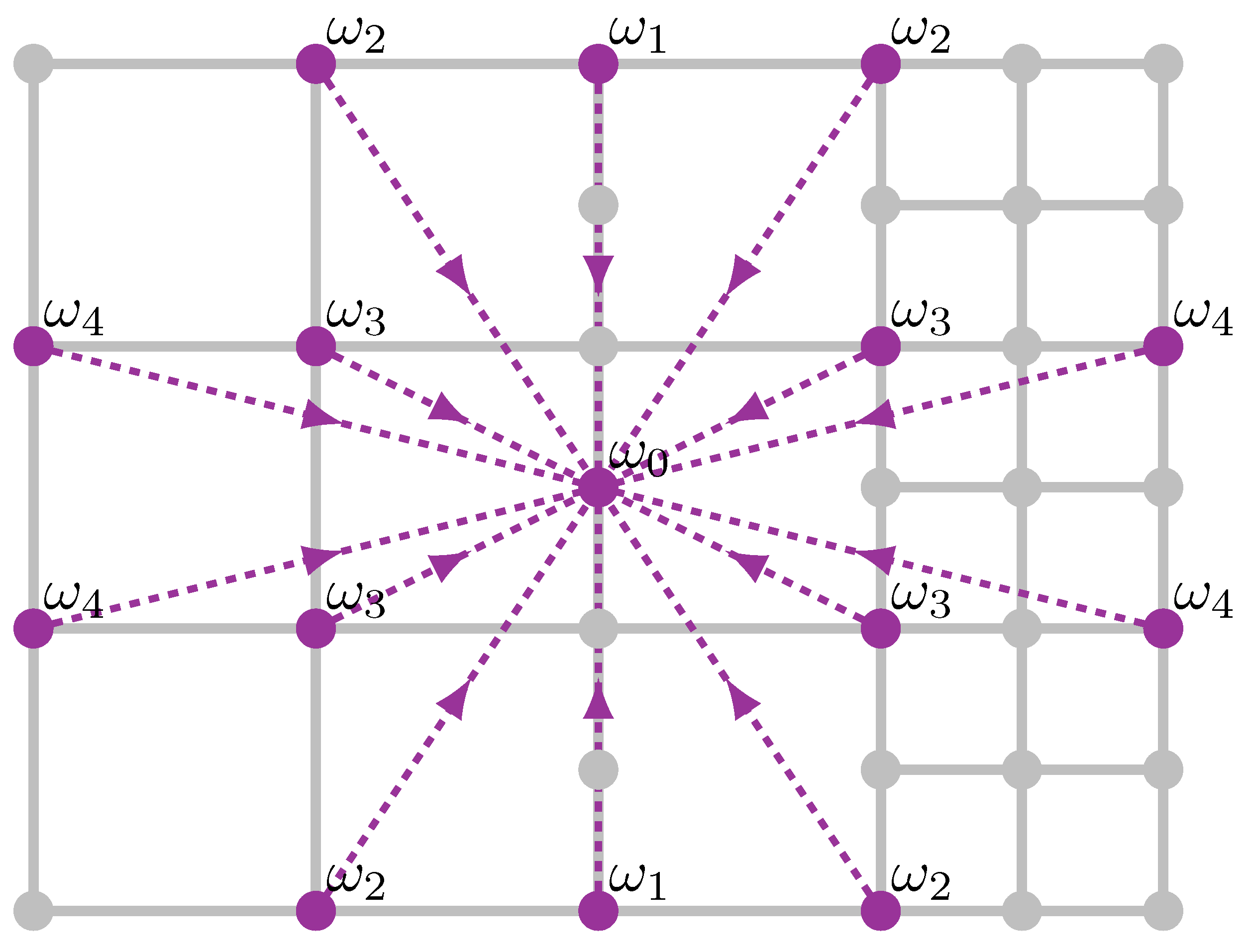

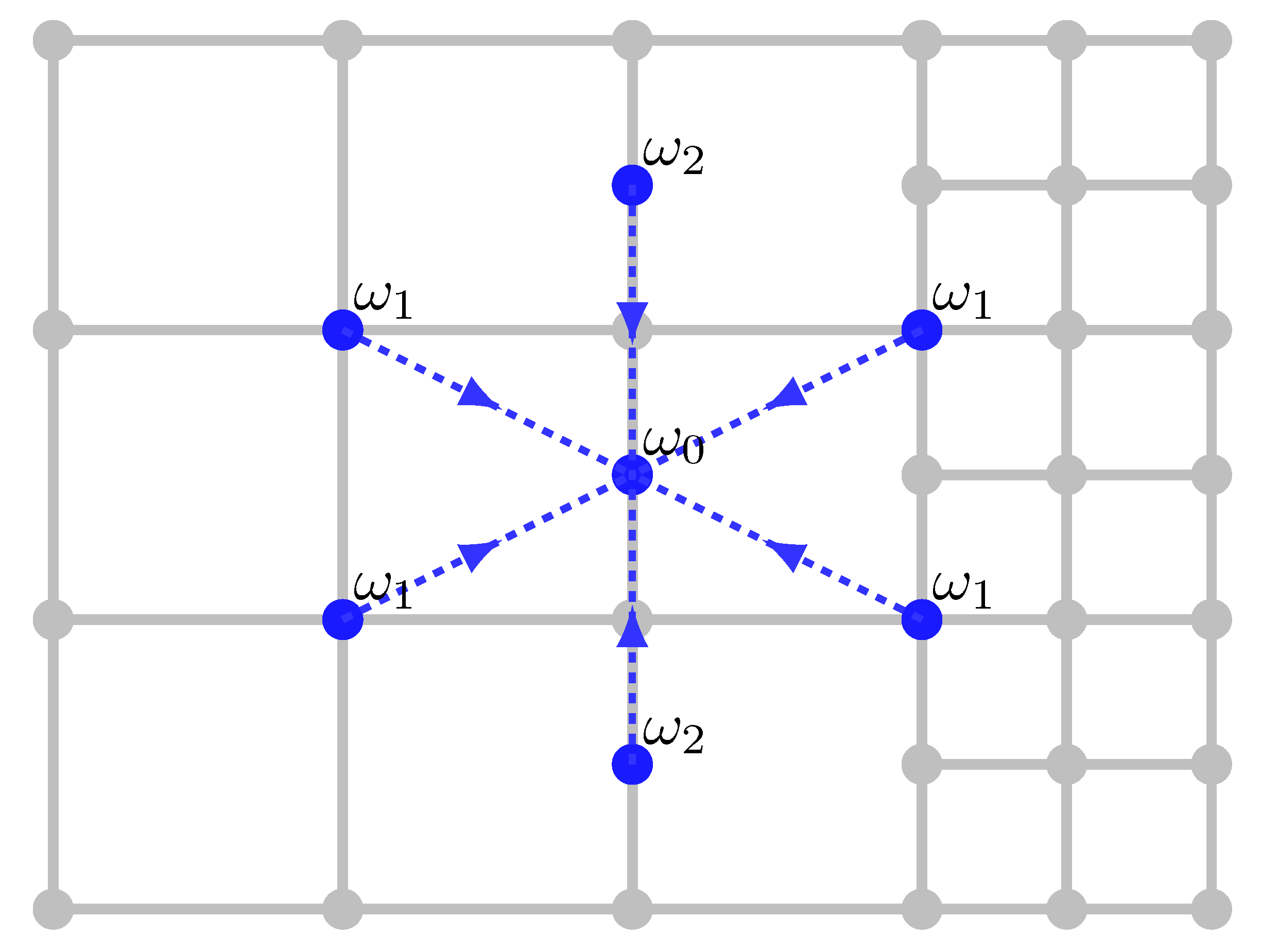

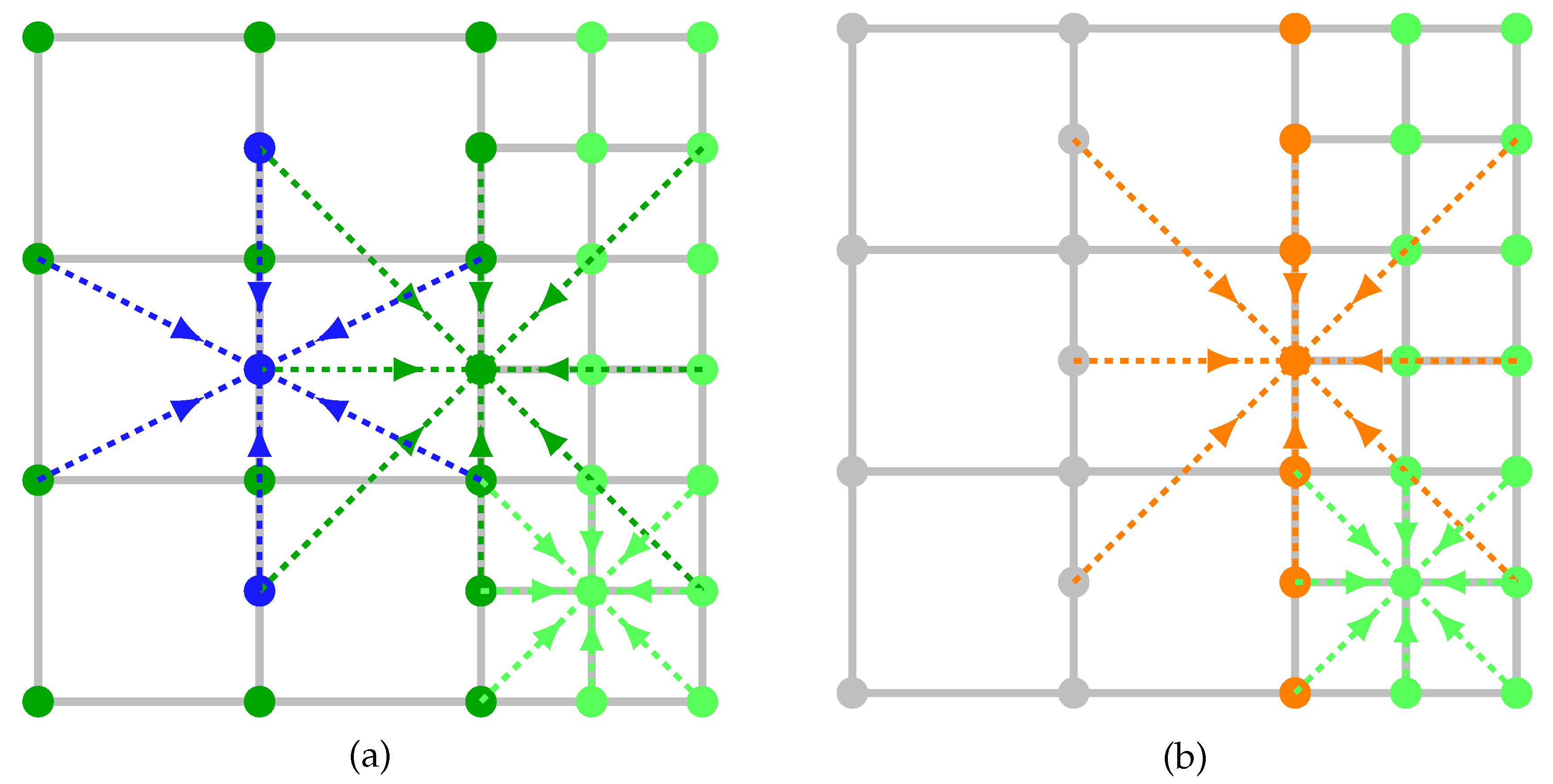

3.2. Stencils and Recalibration

3.3. Full Grid Transition Algorithm

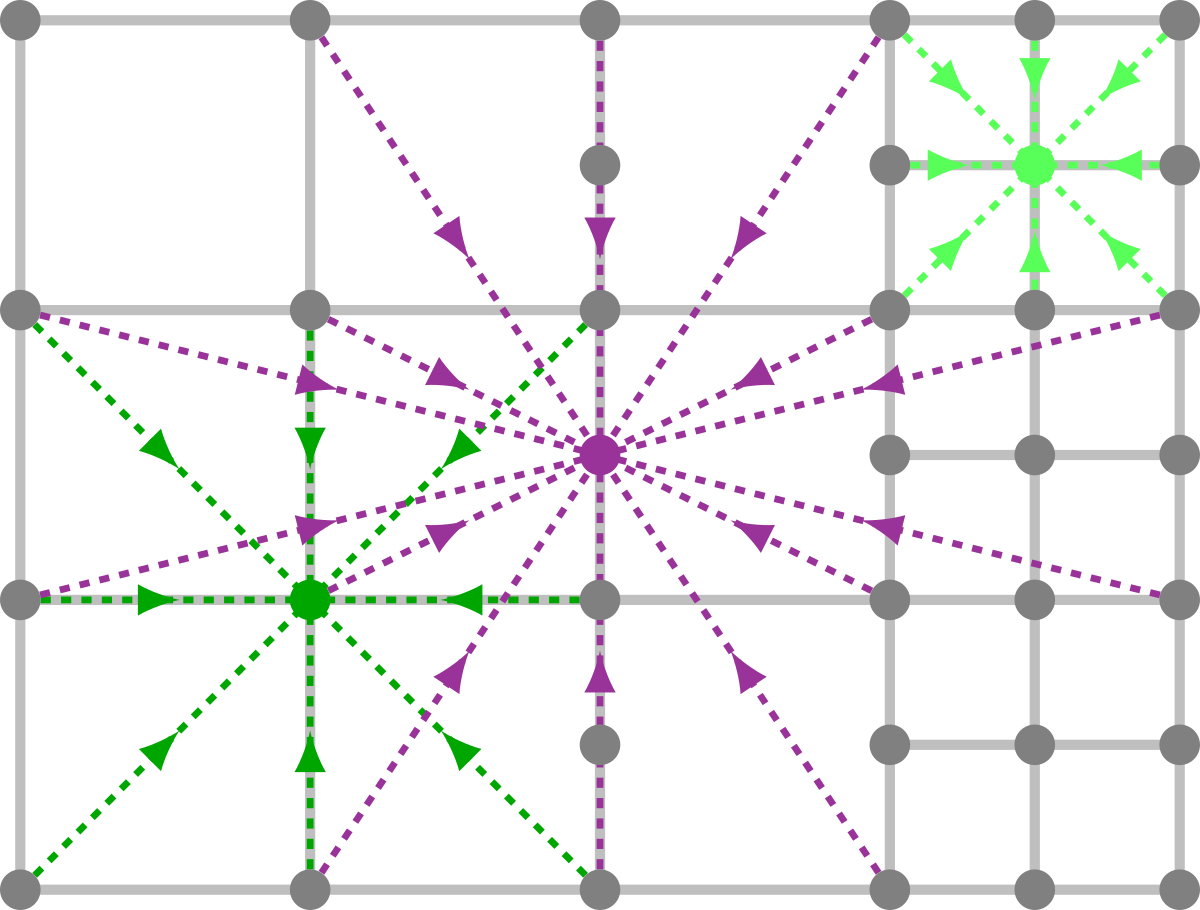

-

Perform streaming on the coarse grid with the use of the stencils

- (a)

- D2Q7(1, 1/4) (or D2Q15(1, 25/38)) for the blue nodes;

- (b)

- D2Q9(1, 1/3) for dark green nodes. Here the incoming populations at the nodes which are exactly on the boundary are saved in a separate temporary buffer to be used in step 5, since the pre-streaming populations are still needed in the next step.

-

Perform streaming on the fine grid (Fig Figure 1(b)) with the use of the stencils

- (a)

- D2Q9(1/2, 1/3) at the light-green nodes;

- (b)

- D2Q9(1/2, 4/3) at the orange nodes.

- Perform collision on the fine grid at the orange and light-green nodes (Fig Figure 1(b)).

- Perform second streaming to the light-green nodes of the fine grid (Fig Figure 1(a)).

- Restore the values of the boundary nodes from the buffer.

- Perform collision on all nodes according to the stencils in Fig Figure 1(a).

4. Benchmarks

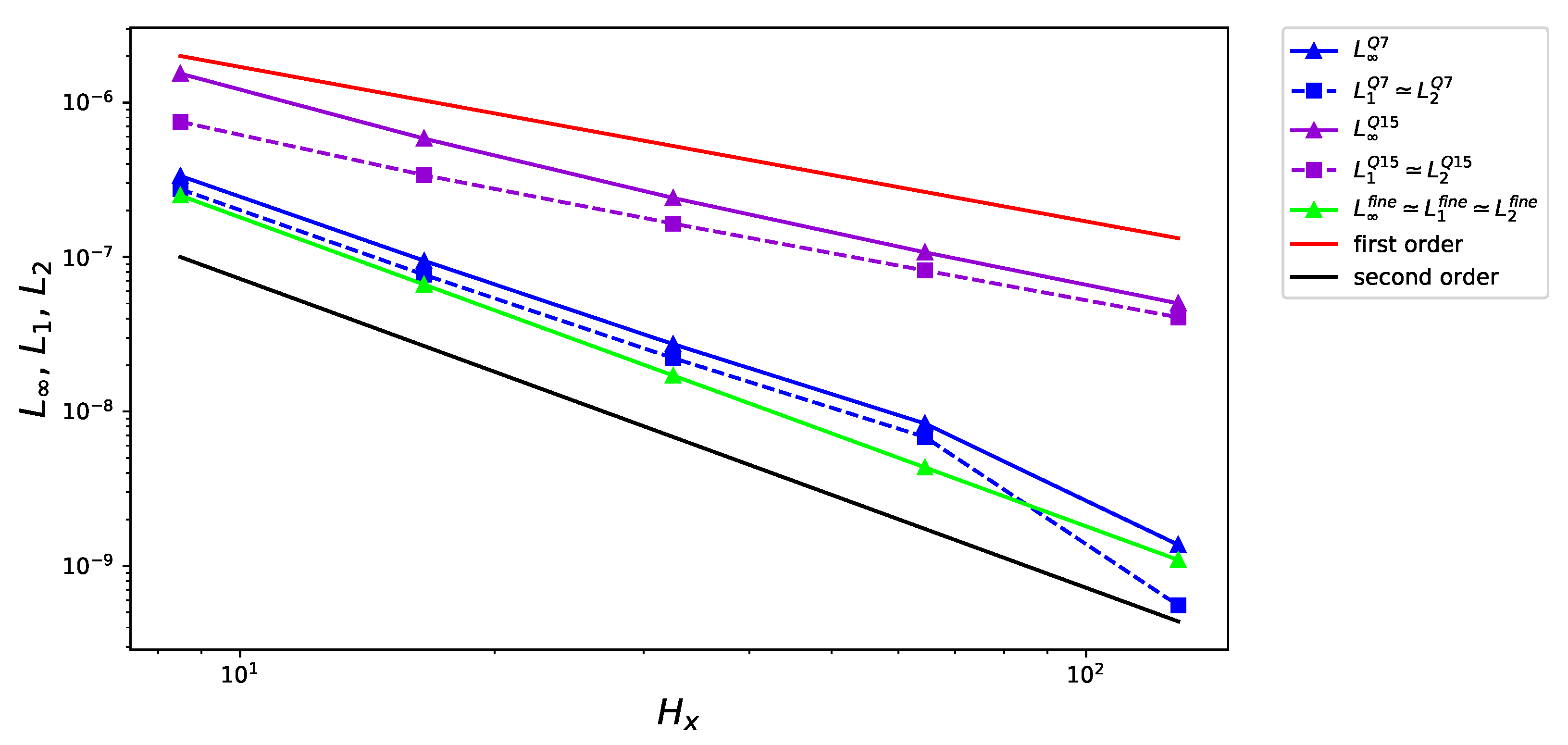

4.1. Poiseuille Flow

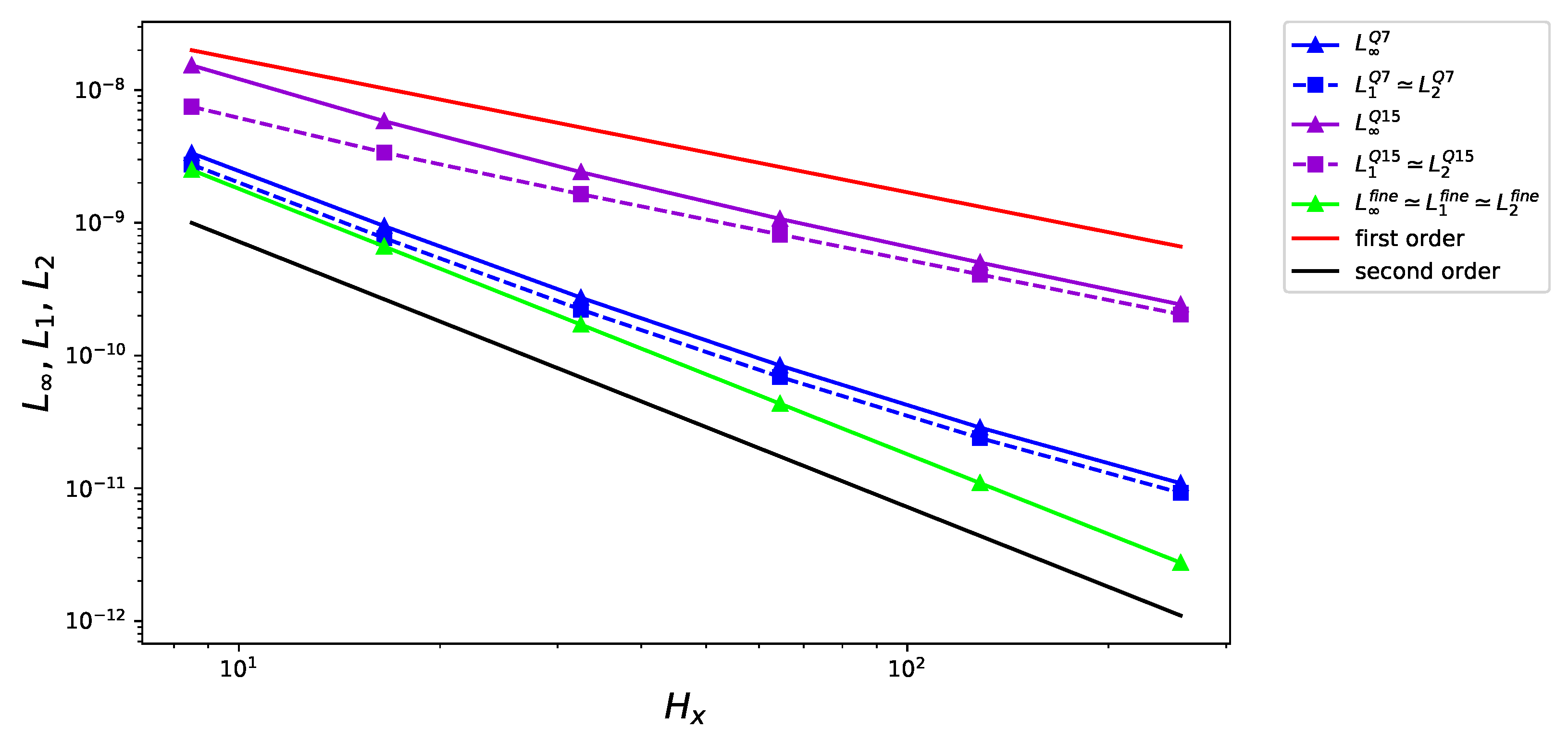

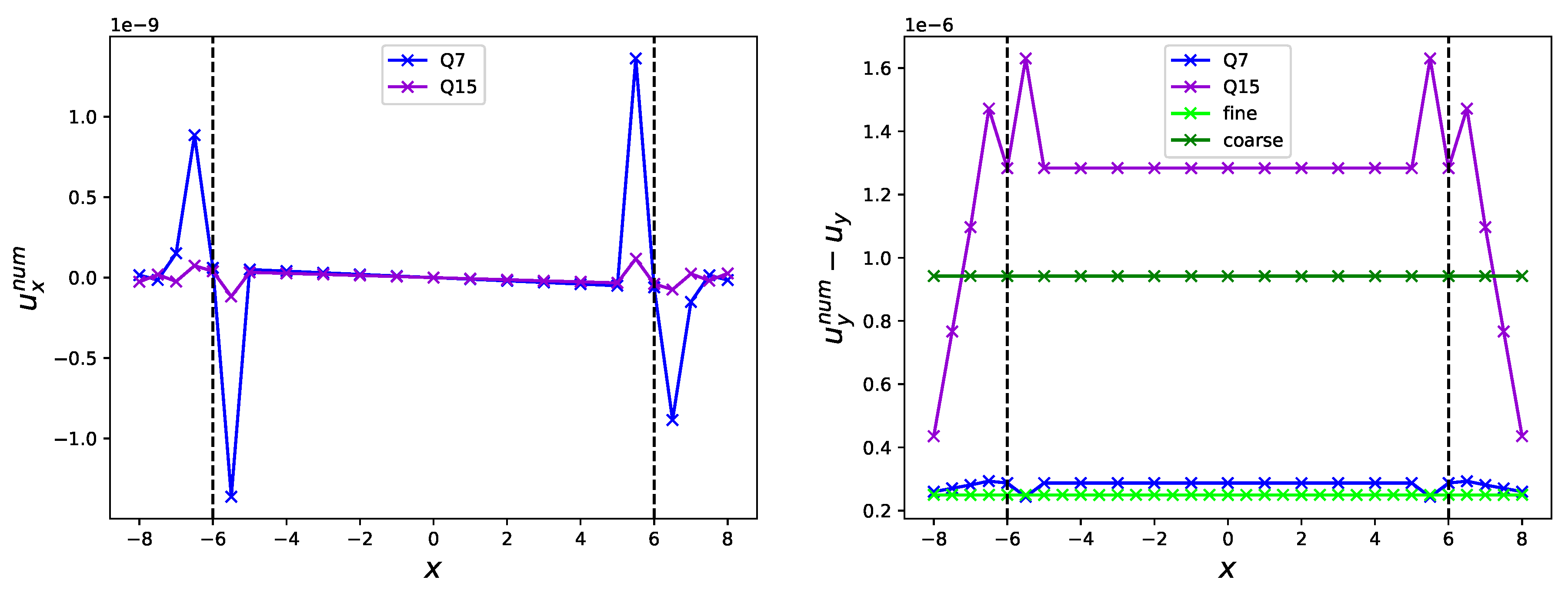

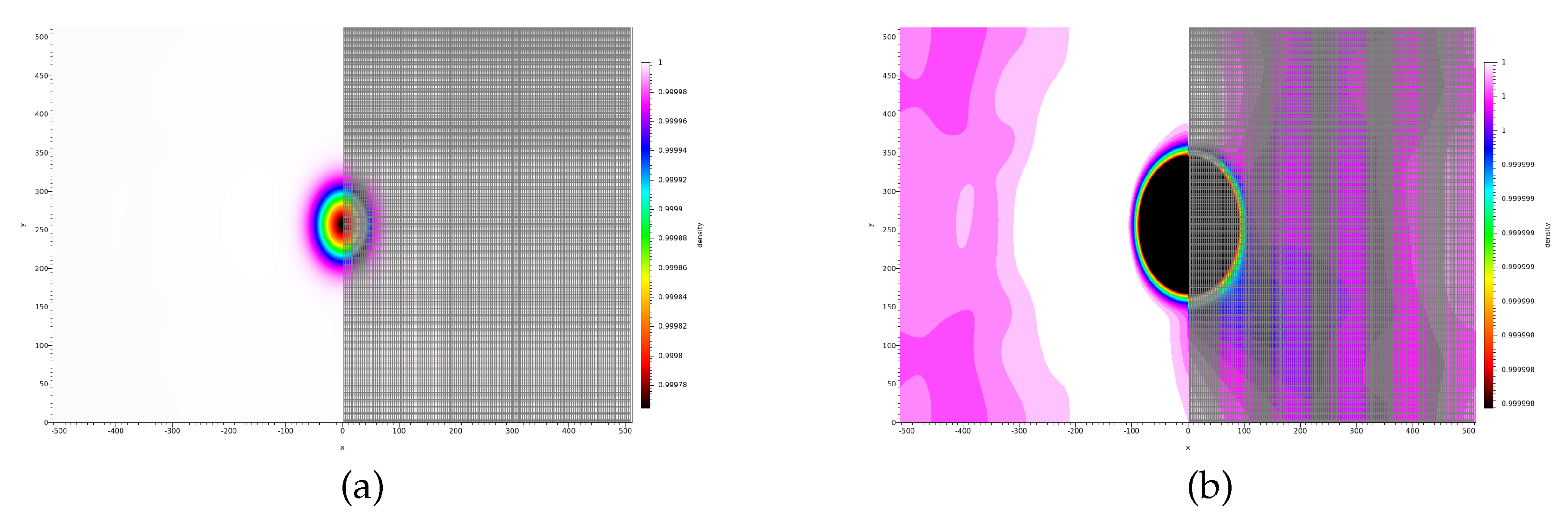

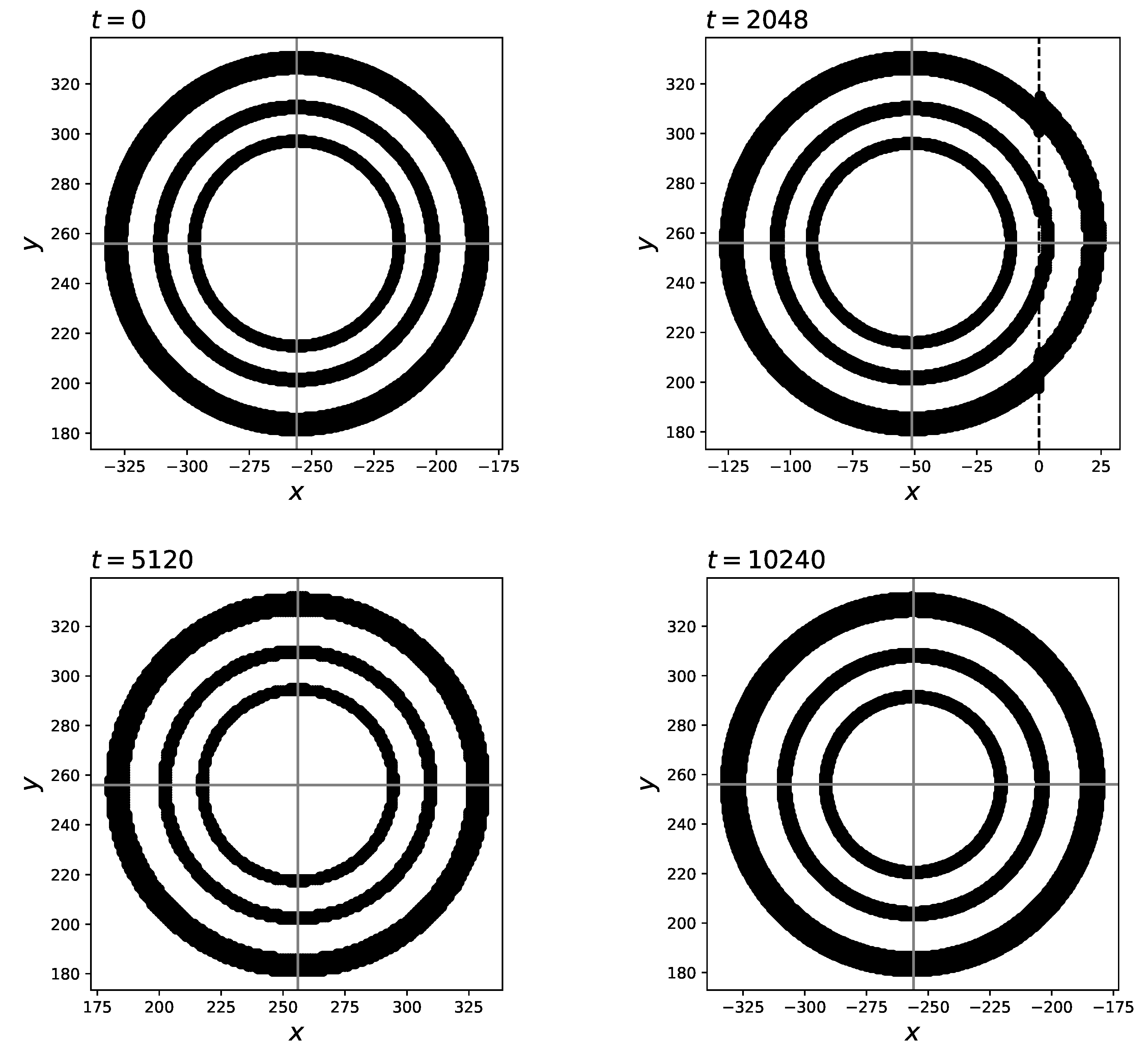

4.2. Athermal vortex

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LBM | Lattice Boltzmann Method |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| BGK | Bhatnagar-Gross-Krook |

| ZAMR | Zipped Data Structure for Adaptive Mesh Refinement |

| IVP | Initial-value problem |

| BVP | Boundary-value problem |

| HRR | Hybrid-recursive regularized |

Appendix A. Stencils for the grid transition

References

- Wolf-Gladrow, D.A. Lattice-gas cellular automata and lattice Boltzmann models: an introduction; Springer, 2004.

- Shan, X.; Yuan, X.F.; Chen, H. Kinetic theory representation of hydrodynamics: a way beyond the Navier–Stokes equation. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2006, 550, 413–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockburn, B.; Shu, C.W. Runge–Kutta discontinuous Galerkin methods for convection-dominated problems. Journal of scientific computing 2001, 16, 173–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmann, M.; Haag, V.; Zeiser, T.; Köstler, H.; Wellein, G. Lattice Boltzmann benchmark kernels as a testbed for performance analysis. Computers & Fluids 2018, 172, 582–592. [Google Scholar]

- Perepelkina, A.; others. Heterogeneous LBM Simulation Code with LRnLA Algorithms. Communications in Computational Physics 2023, 33, 214–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakirov, A.; Belousov, S.; Bogdanova, M.; Korneev, B.; Stepanov, A.; Perepelkina, A.; Levchenko, V.; Meshkov, A.; Potapkin, B. Predictive modeling of laser and electron beam powder bed fusion additive manufacturing of metals at the mesoscale. Additive Manufacturing 2020, 35, 101236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schukmann, A.; Schneider, A.; Haas, V.; Böhle, M. Analysis of Hierarchical Grid Refinement Techniques for the Lattice Boltzmann Method by Numerical Experiments. Fluids 2023, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, M.; Kandhai, D.; Derksen, J.; Van den Akker, H.E. A generic, mass conservative local grid refinement technique for lattice-Boltzmann schemes. International journal for numerical methods in fluids 2006, 51, 439–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippova, O.; Hänel, D. Grid refinement for lattice-BGK models. Journal of computational Physics 1998, 147, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippova, O.; Hänel, D. A novel lattice BGK approach for low Mach number combustion. Journal of Computational Physics 2000, 158, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorschner, B.; Frapolli, N.; Chikatamarla, S.S.; Karlin, I.V. Grid refinement for entropic lattice Boltzmann models. Physical Review E 2016, 94, 053311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagrava, D.; Malaspinas, O.; Latt, J.; Chopard, B. Advances in multi-domain lattice Boltzmann grid refinement. Journal of Computational Physics 2012, 231, 4808–4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tölke, J.; Krafczyk, M. Second order interpolation of the flow field in the lattice Boltzmann method. Computers & Mathematics with Applications 2009, 58, 898–902. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Filippova, O.; Hoch, J.; Molvig, K.; Shock, R.; Teixeira, C.; Zhang, R. Grid refinement in lattice Boltzmann methods based on volumetric formulation. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2006, 362, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Fan, L.S. An interaction potential based lattice Boltzmann method with adaptive mesh refinement (AMR) for two-phase flow simulation. Journal of Computational Physics 2009, 228, 6456–6478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.; Eibl, S.; Godenschwager, C.; Kohl, N.; Kuron, M.; Rettinger, C.; Schornbaum, F.; Schwarzmeier, C.; Thönnes, D.; Köstler, H.; et al. waLBerla: A block-structured high-performance framework for multiphysics simulations. Computers & Mathematics with Applications 2021, 81, 478–501, Development and Application of Open-source Software for Problems with Numerical PDEs. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhari, A.; Lee, T. Finite-difference lattice Boltzmann method with a block-structured adaptive-mesh-refinement technique. Physical Review E 2014, 89, 033310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, R.; Shyy, W. On the Finite Difference-Based Lattice Boltzmann Method in Curvilinear Coordinates. Journal of Computational Physics 1998, 143, 426–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhao, T.S. Explicit finite-difference lattice Boltzmann method for curvilinear coordinates. Phys. Rev. E 2003, 67, 066709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.; Xi, H.; Duncan, C.; Chou, S.H. Finite volume scheme for the lattice Boltzmann method on unstructured meshes. Physical Review E 1999, 59, 4675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, H.; Peng, G.; Chou, S.H. Finite-volume lattice Boltzmann schemes in two and three dimensions. Physical Review E 1999, 60, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; LeBoeuf, E.J.; Basu, P. Least-squares finite-element lattice Boltzmann method. Physical Review E 2004, 69, 065701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krämer, A.; Küllmer, K.; Reith, D.; Joppich, W.; Foysi, H. Semi-Lagrangian off-lattice Boltzmann method for weakly compressible flows. Phys. Rev. E 2017, 95, 023305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilde, D.; Krämer, A.; Reith, D.; Foysi, H. Semi-Lagrangian lattice Boltzmann method for compressible flows. Physical Review E 2020, 101, 053306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, Y.; Shu, C.; Niu, X. A new differential lattice Boltzmann equation and its application to simulate incompressible flows on non-uniform grids. Journal of Statistical Physics 2002, 107, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzik, S.; Gao, X.; Weisgraber, T.; Alder, B.; Colella, P. An adaptive mesh refinement strategy with conservative space-time coupling for the lattice-Boltzmann method. 51st AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting including the New Horizons Forum and Aerospace Exposition, 2013, p. 866.

- Liu, Z.; Li, S.; Ruan, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, L.; Huang, D.; Xu, J. A New Multi-Level Grid Multiple-Relaxation-Time Lattice Boltzmann Method with Spatial Interpolation. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Shan, X.; Chen, H. Galilean invariance of lattice Boltzmann models. Europhysics Letters 2008, 81, 34005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timm, K.; Kusumaatmaja, H.; Kuzmin, A.; Shardt, O.; Silva, G.; Viggen, E. The lattice Boltzmann method: principles and practice; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Saadat, M.H.; Dorschner, B.; Karlin, I. Extended Lattice Boltzmann Model. Entropy 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, F.J.; Chen, S.; Sterling, J. Lattice Boltzmann thermohydrodynamics. Physical Review E 1993, 47, R2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, A.; Chopard, B. Theory and applications of an alternative lattice Boltzmann grid refinement algorithm. Physical Review E 2003, 67, 066707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorschner, B.; Bösch, F.; Karlin, I.V. Particles on demand for kinetic theory. Physical review letters 2018, 121, 130602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakirov, A.; Korneev, B.; Levchenko, V.; Perepelkina, A. On the conservativity of the Particles-on-Demand method for solution of the Discrete Boltzmann Equation. Keldysh Institute Preprints 2019, pp. 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Zipunova, E.; Perepelkina, A.; Zakirov, A.; Khilkov, S. Regularization and the Particles-on-Demand method for the solution of the discrete Boltzmann equation. Journal of Computational Science 2021, 53, 101376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipunova, E.; Perepelkina, A. Development of Explicit and Conservative Schemes for Lattice Boltzmann Equations with Adaptive Streaming. Keldysh Institute Preprints 2022, pp. 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Kallikounis, N.; Dorschner, B.; Karlin, I. Particles on demand for flows with strong discontinuities. Physical Review E 2022, 106, 015301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallikounis, N.; Karlin, I. Particles on Demand method: theoretical analysis, simplification techniques and model extensions. arXiv preprint, 2023; arXiv:2302.00310. [Google Scholar]

- Sawant, N.; Dorschner, B.; Karlin, I.V. Detonation modeling with the particles on demand method. AIP Advances 2022, 12, 075107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shi, Y.; Shan, X. Temperature-scaled collision process for the high-order lattice Boltzmann model. Physical review E 2019, 100, 013301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatnagar, P.L.; Gross, E.P.; Krook, M. A model for collision processes in gases. I. Small amplitude processes in charged and neutral one-component systems. Physical review 1954, 94, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.H.; d’Humières, D.; Lallemand, P. Lattice BGK models for Navier-Stokes equation. EPL (Europhysics Letters) 1992, 17, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippi, P.C.; Hegele Jr, L.A.; Dos Santos, L.O.; Surmas, R. From the continuous to the lattice Boltzmann equation: The discretization problem and thermal models. Physical Review E 2006, 73, 056702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlin, I.; Asinari, P. Factorization symmetry in the lattice Boltzmann method. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2010, 389, 1530–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallikounis, N.G.; Dorschner, B.; Karlin, I.V. Multiscale semi-Lagrangian lattice Boltzmann method. Phys. Rev. E 2021, 103, 063305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiller, D.; Dünweg, B. Semiautomatic construction of lattice Boltzmann models. Physical Review E 2020, 101, 043310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.; Perepelkina, A. Zipped Data Structure for Adaptive Mesh Refinement. Parallel Computing Technologies: 16th International Conference, PaCT 2021, Kaliningrad, Russia, September 13 –18 2021, Proceedings 16. Springer, 2021, pp. 245–259.

- Ivanov, A.; Khilkov, S. Aiwlib library as the instrument for creating numerical modeling applications. Scientific Visualization 2018, 10, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukop, M. DT Thorne, Jr. Lattice Boltzmann Modeling Lattice Boltzmann Modeling; Springer, 2006.

- Ginzburg, I.; d’Humières, D. Multireflection boundary conditions for lattice Boltzmann models. Phys. Rev. E 2003, 68, 066614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissocq, G.; Boussuge, J.F.; Sagaut, P. Consistent vortex initialization for the athermal lattice Boltzmann method. Physical Review E 2020, 101, 043306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astoul, T.; Wissocq, G.; Boussuge, J.F.; Sengissen, A.; Sagaut, P. Analysis and reduction of spurious noise generated at grid refinement interfaces with the lattice Boltzmann method. Journal of Computational Physics 2020, 418, 109645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.; Bahlali, M.; Favier, J.; Sagaut, P. A hybrid recursive regularized lattice Boltzmann model with overset grids for rotating geometries. Physics of Fluids 2021, 33, 057113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coreixas, C.; Latt, J. Compressible lattice Boltzmann methods with adaptive velocity stencils: An interpolation-free formulation. Physics of Fluids 2020, 32, 116102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frapolli, N.; Chikatamarla, S.S.; Karlin, I.V. Lattice kinetic theory in a comoving Galilean reference frame. Physical review letters 2016, 117, 010604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).