1. Introduction

It is without no doubt that one of the main drivers of the next-generation smart grid will be the huge amount of information made possible by new and legacy measurement infrastructures [

1]. This necessitates that the corresponding energy management system (EMS) and control system needs guaranteed reliability and accuracy of salient information about the operating state of the grid [

2]. Moreover, this information can be acquired in different ways, and they potentially contain different types of data. As far as the smart grid is concerned, the amount of information that emanates from the grid is huge due to the deployment of several measurement devices at various levels and nodes in the power system. This implies that the conventional transmission system state estimation (TSSE) and the emerging distribution system state estimation (DSSE) need to be adapted to the changing information exchange within and outside the smart distribution network [

3].

Using data to predict or estimate the operating conditions of the grid across different operating levels require accurate state estimation algorithms (SE) [

4]. The idea of state estimation in a power system is the recovery of the underlying state of the power system from noisy measurements. In other words, it is a data processing procedure to transform redundant meter readings taken from virtually all the parts of the power system of interest with other relevant information to ascertain the voltage profile of the network [

5]. These state estimation algorithms are originally conceived for transmission system networks and there have considerable research efforts done in this area to further development [

6]. The TSSE proceeds with the assumption of balanced positive sequence mesh operation, online tap changer position, breakers’ state, and a host of analogue measurements that include line flows, bus injections, voltage, and phasor measurements as potential measurements to be fed to the algorithms and the bus voltages and phasors are considered as the state variables to the extracted for further decision-making processes [

7].

Like the TSSE, distribution system state estimation programs can be used to ascertain the state and health of the power distribution networks. However, the wide use of state estimation in distribution is not fully adopted, unlike the TSSE. The obvious reasons are the dissimilarities between the two electricity value chains in terms of metering infrastructure investment, structure, operation, and modelling [

8]. Moreover, the present real-time measurement by the distribution automation systems (DAS) positioned at the substation and some feeders can be used for estimation, however, the estimation process becomes challenging due paucity of real-time measurements which in turn results in low observability of the network [

9,

10]. Also, distribution system networks are multiphase feeders that are mostly radial or sometimes weakly meshed. The loads connected are mostly single and V-shape rather than a uniform three-phase load which makes the system highly unbalanced and challenging for state estimation. In addition, due to short connecting lines and low voltage levels, the R/X ratio of the distribution system is higher than that of the transmission network. This high R/X negatively impact the convergence of SE algorithms like the Newton-Raphson approach [

11]. Furthermore, real-valued measurement and phasor measurements from the DAS can make the estimation measurement functions complex or linear depending on its composition. The former consists of real and reactive power line flow and bus voltage magnitudes. These measurements as seen in the transmission network are non-linear functions of the state variable vectors [

12]. As for the latter i.e. DSSE, the complex bus voltages and line currents measurements from PMU or D-PMU can be represented as a linear function of the state variables [

13,

14]. Another issue with DSSE is the assumption that the line parameters and network topology remain constant and known accurately. Although, this is not always the case and the DSSE model has large uncertainty in the estimation results.

Since one of the major bottlenecks of the DSSE is the lack of sufficient measurements needed for required observability, it is customary to include pseudo-measurements. These measurements are estimated using historical data on energy consumption and renewable energy resources like wind and solar to forecast demand and generations at respective points in the network. However, these pseudo-measurements are less accurate than real-time measurements and they usually have a large covariance. Hence, robust state estimations are usually employed to account for this significant noise in the estimated pseudo-measurements [

15,

16].

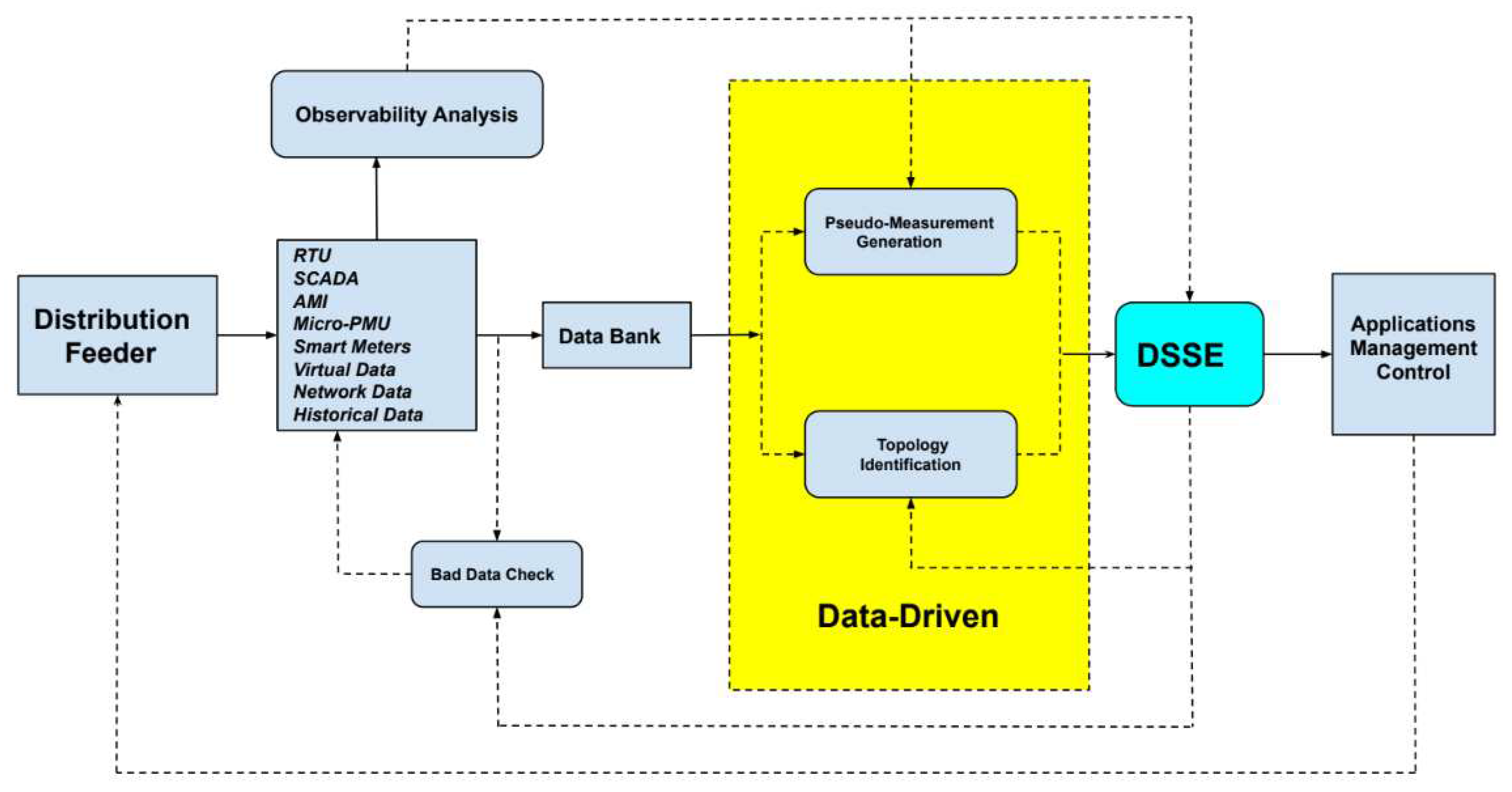

This article is partitioned based on the flow in Figure 1.

Section 2 gives a detailed description of the block diagram in Figure 1 showing how different DSSE modules are related and interconnected. Furthermore,

Section 3 analyses the fundamental nonlinear power flow that characterizes a distribution feeder and the associated load model. Also,

Section 4 enumerates different types of measurements in the distribution network and a brief emphasis on pseudo-measurement generation methods. In

Section 5, DSSE algorithms were discussed based on robustness, approximations, and sparsity.

Section 6 and

Section 7 talk about topology identification and data-driven DSSE methods based on machine and deep learning approaches respectively. Furthermore, future research direction and conclusions are provided in

Section 8 and

Section 9.

2. State estimation

It is with no doubt that state estimation (SE) forms the backbone of the energy management systems (EMS) in the distribution system. The information gathered from the SE is crucial to some critical power system operation tasks such as optimal power flow, voltage control, contingency analysis, congestion management, fault management etc [

17]. However, the quality and accuracy of the SE results are affected by measurement unavailability and uncertainties. These two issues could manifest as bad or stealthy data attacks, communication failures or telemetry errors. Therefore, the SE process must be equipped with ad-hoc pre-processing and post-processing functional tools that clear erroneous data, deal with measurement unavailability, and filters out any deliberate or random errors that the system is exposed to for security and quality purpose [

18].

Figure 1 depicts a typical state estimation process applicable to both TSSE and DSSE. The whole arrangement ensures that the whole process is robust and reliable before being deployed to the EMS. It basically starts by gathering all information related to the network and processes the topology of the current system with information from network data and virtual measurements like the breakers and switches. After this is achieved, another pre-processing stage is activated; observability analysis. This state gathers all available real-time measurements and assesses the observability of the entire network to check redundancy or deficiency. If the network is unobservable, pseudo-measurements can be generated by classical or machine learning approach from historical data available to the operator in the data bank. This approach can also be referred to as forecast-aided state estimation (FASE) in dynamic state estimation (DSE) [

19,

20]. Next is the state estimation algorithm which is the core of the DSSE. It harnesses the information in the data bank to provide the state of the system. The issue of bad data detection and identification can be incorporated into the SE algorithm or implemented as a preprocessing or post-processing process. This process rejects off-the-mark measurements or attacks while implementing the SE or before running it [

21,

22]. Lastly, the SE results are further cross-checked to analyze possible errors in the assumed network topology. These processes go on and keep readjusting and refining until a satisfied forward pass is suitable for deployment. The results are then further utilized by the DSM to make informed decisions and operations on the network.

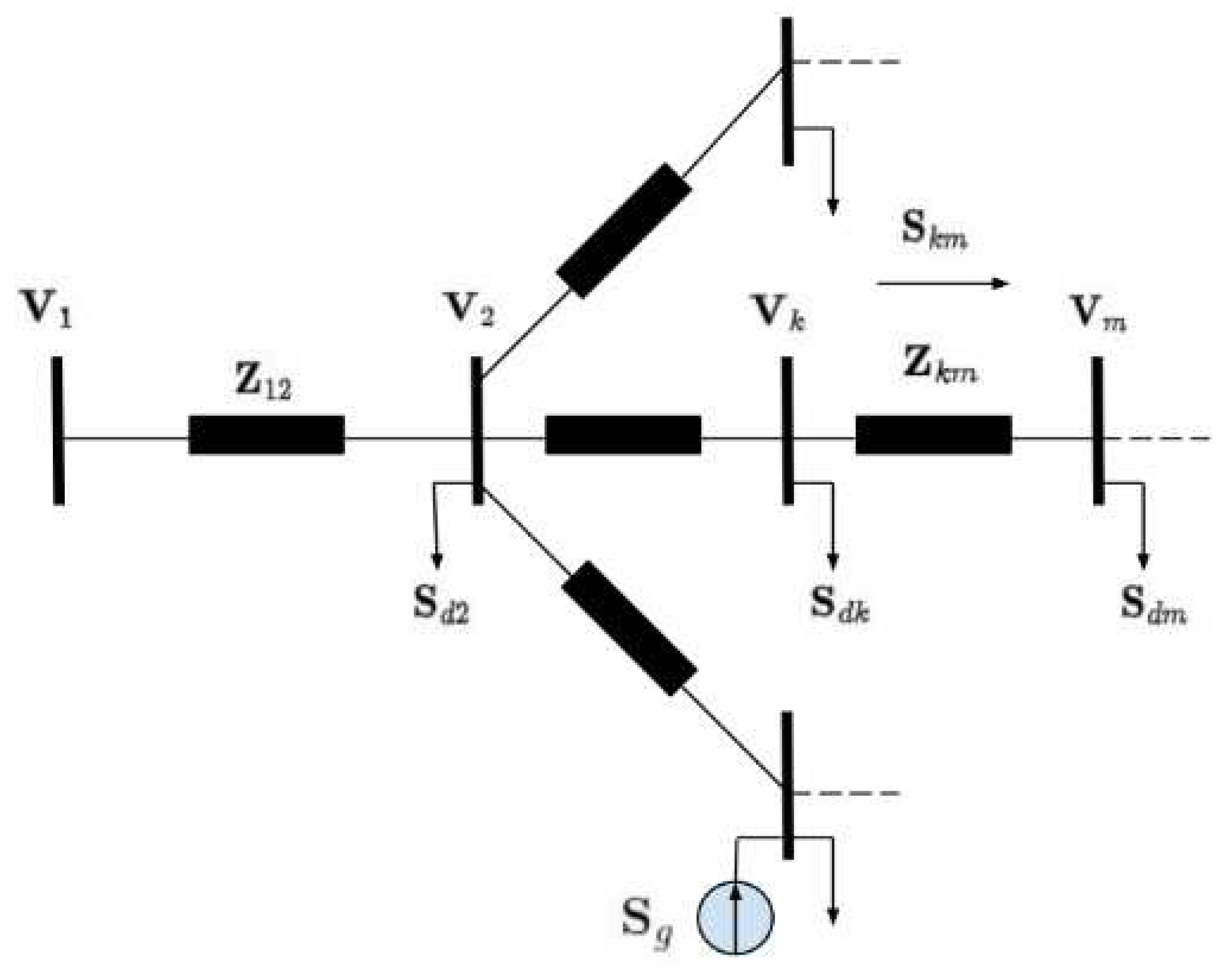

3. Fundamental power flow equation

Figure 2 shows a simplified model of a feeder arm of an arbitrary distribution system which can be used to represent both low voltage (LV) and medium voltage (MV) feeders. These feeder arms can be single, double, or three-phase lines with a neutral line in the case of LV. Also, the loads can be connected in the same fashion which in most cases leads to unbalanced loads in the lines [

23]. A more detailed model will include transformers, regulators and other essential components of the distribution network. However, extremely detailed models render all other operational computations on the distribution system impractical for real-time analyses. Also, the line parameters, that is the impedance are in a 3X3 matrix which includes self and mutual impedances or reduced form in the case of a three-phase four-wire system [

24].

Table 1 gives a quick overview of the main differences between transmission and distribution system networks.

Before any analysis of the network, it is important to get the encoding of the whole network into a single matrix called the incidence matrix (

A). Since most of the power networks can be easily represented as graph networks in terms of nodes (

N) and edges (

E), the incidence matrix is an encoding of the connections between nodes and branches which is necessary to quickly get the admittance matrix (

) from the line impedance value. The fundamental non-linear equations that characterize the active and reactive power flow in an AC network are expressed below

where

and

are the line active and reactive power flows from node

i to node

j. Also, the voltage magnitude and angle at each bus are denoted by

and

respectively while

and

are line parameters that be extracted from the bus admittance matrix.

3.1. Load model

The nature of loads in the distribution system is quite different from that of the transmission. In transmission system load flow, demands are usually represented as a constant power load. However, at the distribution level, the load model usually has the constant impedance, current, and power (ZIP) model. Therefore, it is imperative to model the load according to the type of demand specified at the nodes to capture the power scenario [

25]. The net power injection at a node with both generation and load can be expressed in the complex domain as

The relationship between the injection currents and the voltages for all nodes except the slack node can be represented in the following ZIP model from the specified complex power as

4. Measurements in DSSE

In the traditional distribution system, the only available real-time measurements are the nodal voltage at the substations, power supplied to the feeders downstream, and information about switch status in some designated locations [

26]. These limited number of measurements initially make DSSE unattractive and impractical in power systems operations due to little or no redundancy like the transmission network. With the concept of a smart grid being more disruptive in the distribution system, different measurement devices are being deployed at different levels and locations to gather information needed for the smart operation of the system. Summarily, the types of measurements available for the DSSE utilization can be categorized into three main types: real-time measurements, pseudo-measurements, and virtual measurements [

27]. These measurements are necessary to bypass the problem of observability in the DSSE algorithm.

4.1. Real-time data for DSSE

Real-time measurements as briefly described above can be synchronous or asynchronous measurements. The synchronous measurements are usually the phasor measurement units (PMU). They simultaneously sample current and voltage waveforms at different points in the power system using the same synchronizing signal via the global positioning system (GPS) [

28]. The non-synchronized measurements are the legacy measurements used by SCADA and other measurements gathered by smart meters and they require a dedicated synchronization operator to synchronize them to the current time reference [

29].

4.1.1. PMU in DSSE

Phasor measurement units (PMUs) are gradually becoming a choice for power system estimation and monitoring. Their deployment and applications in the transmission system network are well studied. A power system with only PMUs makes the estimation less computationally intensive and reflective of the real-time dynamics of the system. However, due to cost and other design issues, PMUs have not been fully deployed for power system estimation. Instead, the measurements needed for the estimation are usually a hybrid mixture of PMUs and other non-synchronized measurement devices and mediums like SCADA and RTU [

30]. With the constraints placed on the number of PMUs that can be placed in the transmission network, it is often required that the PMUs are strategically placed at locations that will ensure system observability, accuracy in state estimation results and optimal utilization of resources [

31,

32]. Since present distribution systems are gradually evolving to the active distribution network, the need for devices suitable and tailored for distribution system monitoring has become imperative. So, the deployment of the conventional PMU device at various nodes is not well suited for various applications in the distribution system. Therefore, D-PMU or micro-PMUs with other devices like smart meters are usually employed for these tasks [

33].

4.1.2. Smart meters

Smart meters are a form of demand response strategy that enables the utility to provide comprehensive details of the user’s energy usage and at the same time give them the liberty to manage their energy consumption. That is there exists a two-way communication between the utility and the consumers. They are essential components in the smart grid framework in the distribution system [

34]. Some of the basic information provided by smart meters include cumulative energy (kWh) usage, peak demand active (kW) and reactive (kVar) power. Comprehensive information and applications of smart meters in relation to DSSE are well documented in [

35].

4.1.3. Pseudo meaurements

The paucity of sufficient real-time measurements in the distribution network necessitates the inclusion of pseudo measurements to fulfil the observability criteria needed by the DSSE. That is, the value of a node injection must be determined without it. If the lack of measurement at a particular node is a result of telemetry failure, the operator could easily infer the injection at that node due to knowledge of the system. This is often modelled as Gaussian distribution with mean based on transformer ratings or typical customer load profiles and estimated standard deviation [

36]. However, the assumption of measurement distribution to Gaussian does not always hold [

37].

Aside from the basic method of generating pseudo measurements as mentioned above, other methodical and insightful approaches have been reported in a number of literature. Since injections at nodes in different locations in the network have different probability density functions not necessarily normal, a Gaussian mixture model (GMM) was proposed to encompass these distributions to generate the measurements needed for the DSSE algorithm [

38]. Similarly, an artificial neural network (ANN) capable of generating pseudo measurements with error statistics is used in conjunction with GMM for decomposition is also proposed in [

39]. Instead of GMM decomposition, ANN with Fourier decomposition was introduced in [

40]. Aside from using ANN for the pseudo measurement production,a robust machine learning approach, gradient boosting tree (GBT), is also possible [

41]. Also, a computationally efficient game-theory approach for a pseudo-measurement generator was proposed in [

42].

4.1.4. Virtual measurements

Virtual measurements are information the DMS have about the system with full certainty. They include knowledge about closed and opened switching devices and node locations with no demand and generation. Technically, this includes zero voltage drop, zero power flow, zero bus injections, and even voltage information about the neutral line in a multi-phase network [

43]. They are very essential data that help in augmenting the available information for the DSSE. However, they pose the problem of ill-conditioning in the weighted least square (WLS) algorithm if they are not treated separately in the optimization algorithm [

44]. A brief discussion of how virtual measurements can be inculcated in the conventional DSSE algorithm is discussed in the next section.

Table 2.

Different types DSSE measurement sources.

Table 2.

Different types DSSE measurement sources.

| Measurement Type |

Measurment Variable |

Reference |

| Non-synschronized |

• Node voltage magnitude

• Branch current magnitude

• Complex power flow measurements |

[45] |

| Smart meters |

• Active power injections at the nodes

• Reactive power injections at the nodes |

[46] |

|

PMU or D-PMU |

• Voltage phasors at the nodes

• Branch current phasors |

[47] |

| Pseudo measurements |

Buses with no measurement devices but

active and reactive power estimated from

statistical assumptions and historical data |

[48] |

| Virtual measurements |

Buses with high certainty of no active and

reactive power |

[49] |

5. State estimation algorithm

The process of distribution system state estimation is quite like transmission system state estimation. It involves the estimation of the state of the grid in terms of nodal voltages from measurements at various point in the network. The measurements collected are vulnerable to device errors, communication error, and deliberate attack by intruders. Therefore, it is expedient that the estimation be robust and immune to internal and external disturbances. The measurement model, which shows the connection between measured variables and state variables can be generically expressed as

where

and

are the measurements and state vector respectively. The function

maps the state vector space to the measurement space. Considering the complexity of the network, it is usually a nonlinear relationship. However, it could be reduced to a linear affine transformation if linearization is done within the region of the solution space. The errors in the measurements are denoted as

with the assumption that they have zero means and are uncorrelated which is not absolutely true in some scenarios. Mathematically, this assumption can be expressed below in (

6) and (

7) as

where

M is the number of measurements available for the estimation. The corresponding covariance matrix is then ultimately reduced to a diagonal matrix as

where

is the standard deviation of the measurement variable whose value gives insight into the accuracy of the measurement. Hence, the state estimation algorithm aims to determine the set of state variables that uniquely minimizes the deviation between the measurements and the hypothesized measurement models. The following subsections highlight the requirements and common methods used for the state estimation problem applicable to the distribution system.

5.1. DSSE Requirements

DSSE have many applications in the operations of power systems. Each application has different specifications and requirements the DSSE must fulfil. The basic requirements are time frame, computational efficiency, accuracy, and robustness [

50].

5.1.1. Time frame

This requirement is about the validity of the estimated states in a specified time window. In other words, how often do we need to update the estimated states? This can be further classified as offline and online. In the offline case, the monitoring process and the state estimation process do not need to run in tandem with real-time operations [

51]. This process is sometimes referred to as static state estimation. As for the online case, the state estimates are updated dynamically as measurements are received synchronously or asynchronously [

52]. Another issue to consider is the difference in reporting rates and latency of measurement devices in the field for estimation. For instance, the number of measurements collected from traditional measurement devices per second is much less than that of phasor measurement units (PMU). Since there are different time windows, so the DSSE must be designed in such a way that it takes account of these hybrid measurement sampling rates for accurate estimation [

53].

5.1.2. Accuracy and computational efficiency

Many of the power system operations dependent on state estimations require that the output of the estimator be significantly accurate and close to the real states of the system. The accuracy of the estimator can inherently be compromised in the algorithm, measurements, and network topology [

54]. Accuracy is used to quantify how confident we are about the result of the estimator based on some evaluation metrics. It could be point estimates with less information about the confidence level of the result or probabilistic estimates where the information of the confidence interval of the estimate can be inferred from the probability distribution of the result [

55]. Another source of uncertainty that impacts the DSSE is the assumption of fixed accuracy for the measurement devices and other unavailable indirect measurements like pseudo-measurements. Moreover, the assumption that measurements are uncorrelated is not absolutely true and in instances where we have correlated measurements from different devices, the accuracy of the SE will be affected [

56]. Moreso, the DSSE should take into consideration the uncertainties in network parameters and sudden change in network topology as they are very crucial in the estimation process [

57,

58]. Moreover, each of the power system operations have different time of operations. Therefore, the DSSE must be fast and efficient computationally in relation to its further application in the power system.

5.1.3. Robustness

The robustness requirement is needed to guarantee quality estimator result in the situation of deliberate or accidental measurement data degradation. This decrease in the quality of the estimation could be due to faulty measurement devices, stealthy attack, imperfect modelling or network uncertainties in terms of parameters and topologies. Therefore, DSSE like the TSSE, are usually complemented with external modules with the purpose of detecting bad data and topology processing [

21,

59].

5.2. Model-based state estimation

5.2.1. Weighted Least Square (WLS)

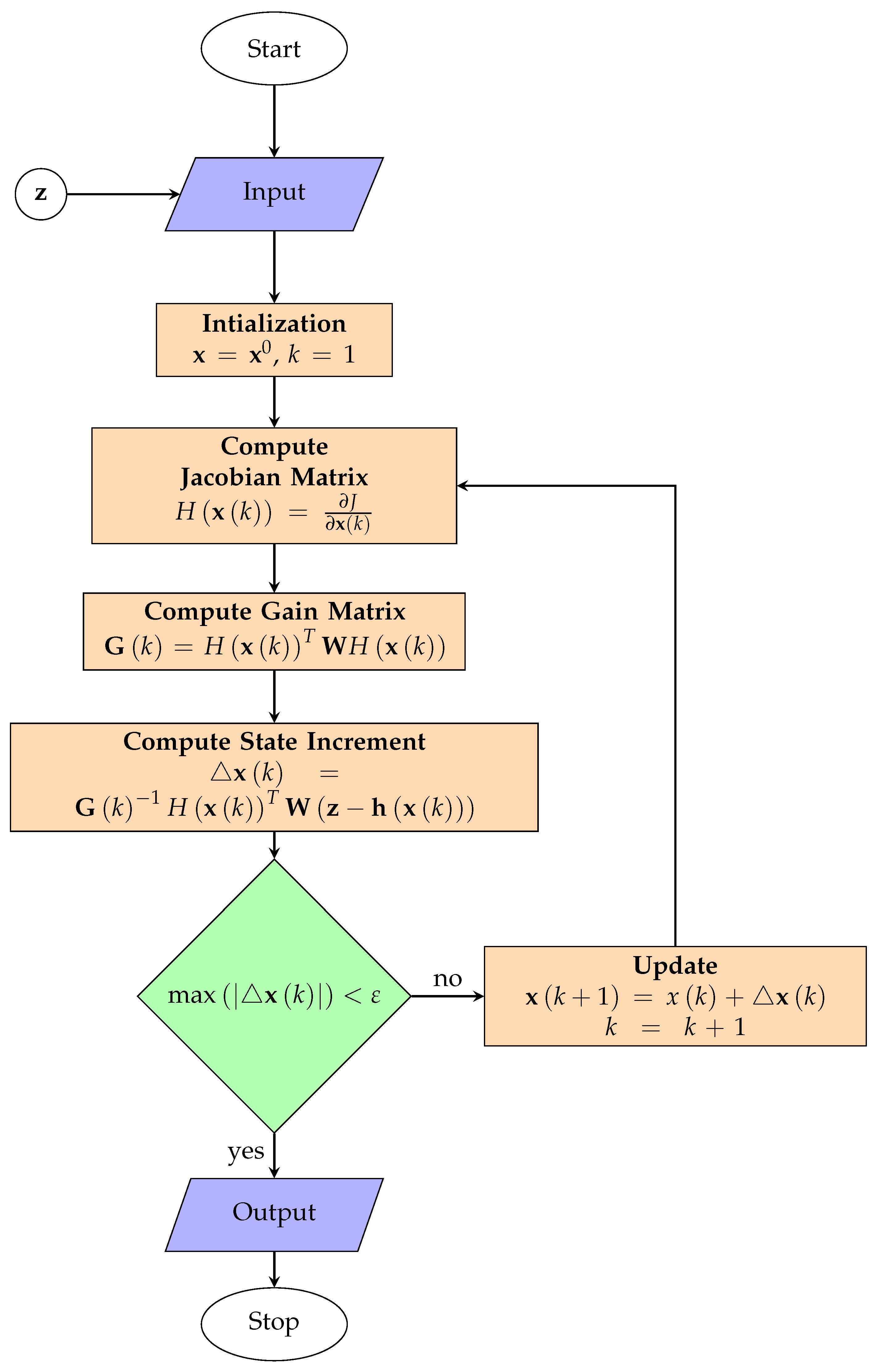

The idea of using the weighted least square (WLS) approach was initially applied to the TSSE problem. Moreover, the same approach can be applied to the DSSE problem with the same issues inherent in this approach. The equation that characterize the WLS approach is

where

is the inverse covariance matrix defined in (

8). The objective function in (

9) is nonlinear and does not have a closed-form solution [

60]. To solve this problem with the obvious nonlinearity, the Gauss-Newton iterative approach is used to solve the optimization problem. The solution algorithm to solve this problem is detailed explicitly in [

61] and depicted pictorially in

Figure 3.

5.2.2. Equality-constrained WLS

One of the issues associated with the WLS approach both for the Gauss-Newton iterative method and the linearized counterpart is the problem of accuracy associated with the zero injection buses. The measurements at these buses are referred to as virtual measurements and are allotted very high accuracy weights in the

W matrix and pose an ill-conditioning problem in the iterative Gauss-Newton method. A way around this ill-conditioning issue is to set aside these virtual measurements as equality constraints alongside (

9) as follow

where

is the measurement function related to the zero-injection buses. Then (

9) and (

10) can then be solved using the Lagrangian multiplier method [

62,

63].

5.2.3. Augmented Matrix WLS

Another approach to subdue the numerical ill-conditioning problem associated with the iterative Gauss-Newton is to use the augmented matrix approach. Similar to the equality-constrained WLS, the improvement is to adopt the measurement residual as an additional variable [

64]. This will eventually lead to additional equality constraints which can also be included in the Lagrangian multiplier approach. The equality constraints can be expressed in (

11) below as

where

r is the measurement residual vector.

5.3. State vector selection

The choice of state variables plays an important role in the complexity of the SE algorithm which is usually determined by the type of network of interest. In the TSSE, due to its highly meshed topology and low R/X ratio, the voltage magnitudes and angles form a natural state vector in the SE [

65]. They have fast convergence, and linear formulation possibility, and are computationally efficient when using branch currents as measurements instead of power flow due to the constant Jacobian matrix. In the case of DSSE, some of its demerits are restricted to only radial topology, state and impedance-dependent Jacobian matrix, and the linear formulation is based on small angle differences. Subsequently, some of the disadvantages of using the polar coordinate formulation can be avoided by using the voltage-based rectangular coordinate formulation. As for the current-based rectangular coordinate formulations, they are the most popular due to their efficiency in computation and ease of adaptability with radial topology. A review of the benefits and demerits of different types of choice of state variables are well documented in [

66].

5.4. Model-based robust DSSE methodologies

The aforementioned model-based WLS algorithm and its variant do not come with the additional benefit of robustness. Therefore, aside from the external module that performs the function of bad data detection and recognition, it is possible to have model-based algorithms that are inherently robust to bad data. A DSSE is statistically robust if the compromised set of redundant measurements does not have an appreciable effect on the estimation results. One of the popular model-based robust techniques is the least absolute value (LAV) method. These robust estimators are robust to outliers in measurement data, however, they generally have the drawback of high computational cost [

67,

68]. The drawback will be more pronounced in DSSE in terms of accuracy and compute cost due to a high number of nodes and leverage measurements. Another robust approach proposed for TSSE, however, has not yet been applied to the DSSE to ascertain its universal robustness is the least-trimmed absolute value estimator (LTAV) which was reported to have low computational cost compared to the LAV [

69]. In order to mitigate the high computational cost of LAV, a robust approach using weighted LAV as the objective function and second-order cone constraints were proposed in [

70]. Other robust estimators are described in

Table 3 in terms of their residual objective functions for comparative analysis.

5.5. Approximated DSSE

As stated earlier, the traditional state estimation problem for DSSE are nonlinear and nonconvex due. This nonlinearity usually emanates from the choice of state variables and the type of measurement devices that dictates the measurement functions. To get around the nonlinearity using the Gauss-Newton approach, many methods other methods have been proposed based on simplicity and computational efficiency.

5.5.1. Linearized DSSE

Some applications that include DSSE in their framework can be made effective and efficient by modelling the DSSE in a linearized form to avoid the Gauss-Newton iteration approach. A very good example of the application of linearized DSSE is the problem of PMU placement in the distribution network [

76]. The approximation procedure has been used for TSSE with the assumption that all the measurements are synchronized phasor measurements. However, the possibility of homogenous measurements from PMUs alone is still not feasible yet due to the high cost of PMUs. With PMU, the measurement function can be broken and separated into real and imaginary parts and the state variables in the nonlinear terms can be further assumed to be constrained within a minimal range to relax the nonlinearity . Another source of nonlinearity is the power and current injections at the nodes or pseudo-measurements. These measurements for model-based algorithms are needed for observability criteria. A popular way to resolve this issue to use complex linearization via Taylor’s approximation of the nonlinear terms to eventually transform the model to a non-iterative procedure [

77,

78]. For a linearized measurement function, the closed-form solution from Linear Algebra is usually expressed below as

where

H is the linear transformation from the state variable space to the measurement space. The closed-form solution in (

13) can be different depending on whether the

H matrix is full rank or not. Another popular approach that yields a linear measurement model is to assume a small angle deviation while minimizing the residual objective function. With this assumption, the whole formulation renders itself to linear manipulation. Moreover, the main merits of these linear approximation approaches are that they require less computing effort, are applicable to meshed topologies, and overcome the problem of ill-conditioning peculiar to the iterative approaches [

79]. Furthermore, an implicit linearization approach to the power flow problem in the distribution system that represents the power flow as a function of the nodal voltages and the node power injections was proposed in [

80]. This linear representation is sparse, efficient computationally, and retains the power flow problem structure. This linear representation has been applied to real-time DSSE application as proposed in [

52].

5.5.2. Convexified DSSE

A more insightful approximation approach to solve the nonlinear state estimation problem is to adopt the convex optimization approach. The power flow equations and optimal flow are nonlinear and a lot of work has been done to convexify these NP-hard problems [

81,

82]. Similarly, this approach has also been extended to the nonconvex state estimation problem especially in the transmission system network [

83]. One approach to the convex optimization is the second-order cone approximation. This involves transforming the nonlinear state estimation problem to a second-order cone program, that is, a linear objective or regularizers with conic and linear constraints. These approach have been proven to be better than the conventional WLS DSSE problem in terms convergence and efficiency [

84]. Another method of convex optimization is the semi-definite program (SDP) relaxation [

85]. It involves formulating the DSSE as SDP having a rank-contrained positive semi-definite matrix as a decision variable. The main drawback of this approach is that the constrained matrix should have be rank-one for optimality to be reached. In order to achieve the rank-one contraint, [

86] proposed a two-step approach involving rank-reduction alongside convex iteration. A scalable approach to the previously mentioned is also proposed in [

87].

5.6. Probabilistic DSSE

The idea of probabilistic DSSE was to avoid the main problems associated with model-based WLS algorithms which are not usually valid in distribution system networks: convergence issues, Gaussian error assumptions, and pseudo-measurements usage [

88]. Moreover, the WLS approach is a specific form of the maximum likelihood estimator (MLE) where the measurement distributions are drawn from a Gaussian probability density function. The MLE can be succinctly expressed in (

14) below as

where

is the pdf of the

measurement in the set of all the possible

M measurements including real and pseudo-measurements. The MLE can then be solved with an appropriate pdf that captures the reality of both the real and pseudo-measurements. There is no best non-gaussian distribution for this particular task. However, there are some non-gaussian pdfs that have been successfully employed for this task and have proven to be more accurate than the traditional WLS with Gaussian distributions. However, the price to pay is the higher computational effort. Nevertheless, these methods still have reasonable computational time acceptable for practical implementation. Some of these distributions are beta, polynomial, GMM, Gaussian equivalent (GE), and Gaussian approximation (GA) as comprehensively reported and demonstrated in [

89].

5.7. Compressive sensing DSSE

The unobservable property associated with the distribution network has motivated the search for applicable novel methods outside the domain of the power system. One such method is the idea of compressive sensing (CS) in the area of signal processing [

90,

91]. The idea of CS is the effort of finding the sparsest solution to the set of under-determined linear equations [

92]. Since this goal is similar to the problem of unobservable DSSE, CS fits in naturally among the possible solution to the DSSE. It uses the correlation between states and measurements to form a sparsified relationship which can then be further exploited to estimate the states. The particular CS method to be employed depends on whether the correlation is temporal or spatiotemporal. The spatial approaches, 1-D and Matrix completion (MC) perform the DSSE at a given time instant [

93,

94]. As for the spatial-temporal methods, 2D-CS and Tensor completion (TC) are exploited both in time and space [

95,

96]. Comparatively, the spatial domain, the 1-D CS performs better than the MC while in the spatial-temporal domain, the TC approach performs better in accuracy and complexity as detailed in [

97].

6. Topology and parameter estimation

DSSE can be guaranteed to be accurate for some provided the information about the topology and the network parameters are accurate and do not change significantly with time. This assumption about the immutability of the topology and parameters could have adverse effect on the state estimation result if eventually the topology and parameters are changed due to some unavoidable reasons. These errors in the topology and parameters can affect other important distribution system operations that depends on the accuracy of the DSSE and sometimes correct measurements could be identified as bad data [

4]. Many researchers are expending effort to address the issue of topological change and network parameter errors in DSSE. In [

98], without information of voltage angles from PMUs, a data-driven regression approach in a two-step procedure: a preliminary topology and line parameter estimation and a correction step to recover the voltage angle and the correct topology. Conversely, exploiting available measurements from smart meters, a multiple regression data driven-approach was used to estimate the topology and line parameters of the distribution network of interest [

99]. Addressing the issue of ignoring measurement error state change in historical measurements, [

100] proposed a joint topology and line parameter estimation using the expectation maximization (EM) algorithm for hidden states in measurement recovery. Similarly, an online learning approach based on recursive identification algorithm was proposed to estimate topology and line parameters as captured by the estimated network admittance matrix [

101].

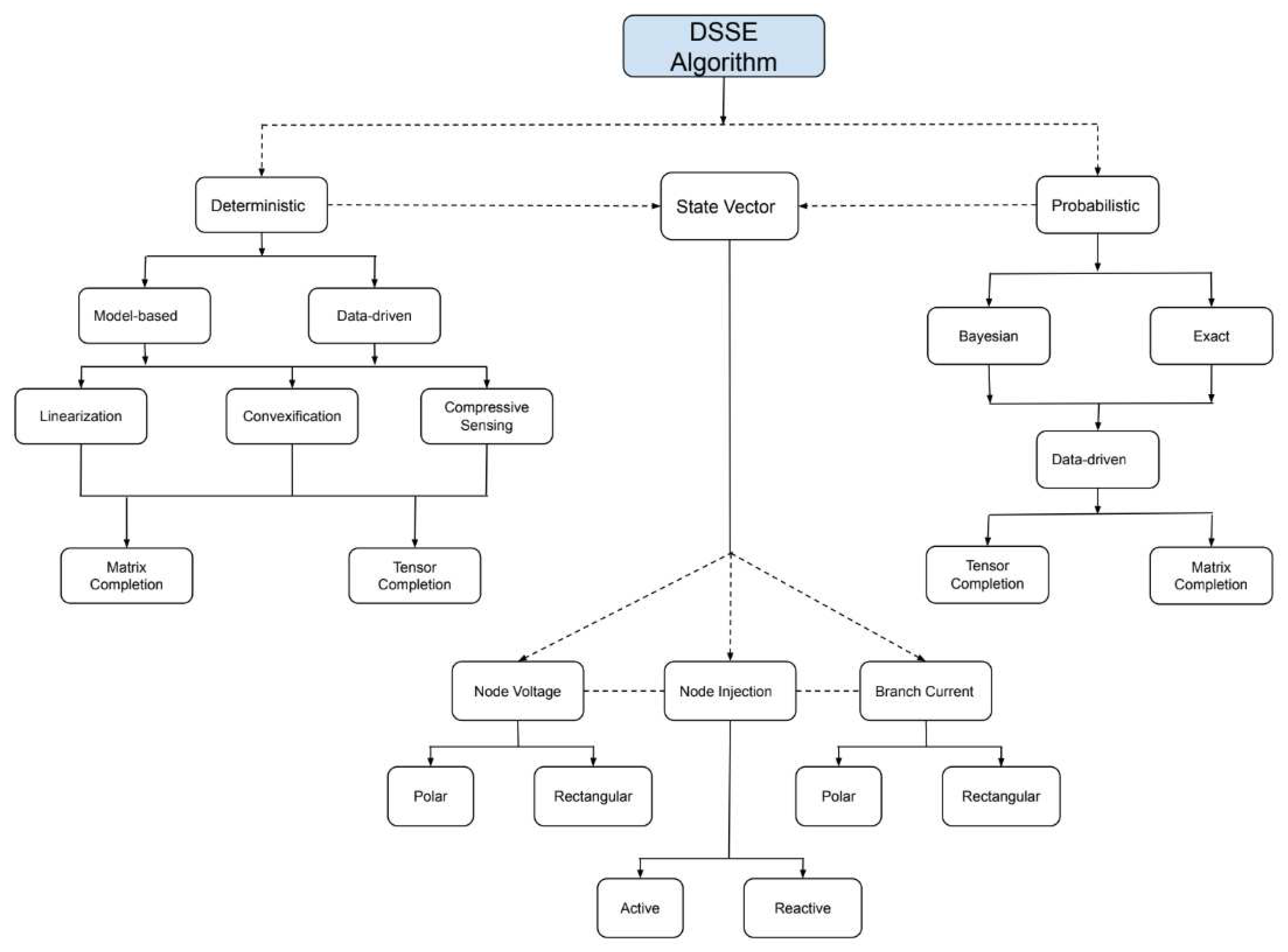

7. Data-driven state estimation

The peculiarities and structure of the distribution system network make distribution state estimation difficult. With many node points of, under-determinate nature due to very low measurements, line parameter uncertainties, and load imbalance the DSSE becomes computationally intensive. However, with the advent of potential distribution system measurements devices like PMU, AMI, and smart meters, researchers are leveraging on a huge amount of data from these variant devices to overcome the issues associated with DSSE using innovative machine and deep learning techniques [

102].

To overcome some of the aforementioned problems with DSSE, [

103] proposed a data-driven DSSE capable of real-time monitoring, and distributed computing based on artificial neural network (ANN) and measurement sparsity to provide an accurate estimate even with the presence of non-Gaussian noise. To address the issue of convergence due to the non-convex nature of the DSSE optimization formulation, a hybrid machine learning and conventional optimization approach was used to address the issue initialization of the state variables which is very crucial to the accuracy of the algorithm [

104,

105]. Apart from the data-driven approach to DSSE, physics-aware deep learning networks are now being applied with data-driven model to learn complex functions associated with the structure of the network [

106]. In [

107], a recurrent neural network (RNN) and prox-linear net-based estimator was proposed for real-time state estimation base on pseudo-measurements. Focusing on the observability issue in distribution systems, a Bayesian deep neural network DSSE capable of bad data detection and noise filtering was proposed in [

15] for an unobservable distribution system network. Similarly, a Bayesian approach to DSSE that takes into account the possible non-Gaussian nature and uncertainties of pseudo-measurements was proposed in [

55]. A fully data-driven approach using generative adversarial networks (GAN) that addresses the issue of missing data without dependency on PMU observability and network topologies was introduced in [

108] with the merit of low computational complexity. A diagrammatic illustration of how data-driven methods fit in the concept of DSSE is depicted in

Figure 4.

8. Recommendtion and future work

With the rising penetration of distributed energy resources, state estimation has become an integral and essential tool in the monitoring and control operations of distribution systems. Moreover, the deployment of different heterogeneous measurement devices in the field has further accentuated the focus and innovative improvement in the DSSE. However, conventional state estimation methods have difficulty fulfilling the observability conditions often associated with distribution systems because of a lack of sufficient metering devices. To address these DSSE limitations, researchers are now developing DSSE methods that are based on a data-driven matrix and tensor completion supplemented with power flow constraints to determine the operating states of the whole system. These techniques are well suited to distribution systems that exhibit unobservability and where standard weighted least-squares-based methods fail to operate and can easily accommodate any network variables measured across the network. Additionally, these approaches can be deterministic or probabilistic as the case may be [

109,

110]. While implementing these methods, the issue of accuracy, time complexity, and robustness must be satisfied to be adopted for practical purposes.

Grid conditions vary both spatially and temporally due to the variability of renewable generation. To address the issue of high penetrations of renewables especially in the distribution network, state forecasting is essential for grid operators and utilities to dispatch controllable energy resources, prepare for changing network conditions, and ultimately minimize operating costs. Another interesting area of research in this regard is to develop machine and deep learning-based techniques capable of short-term forecasting of system states by using decision tree-based approaches, ensemble learning, and specialized neural networks. The grid operators can use the forecasted states for control coordination and prioritization. Therefore, the resilience, reliability, and economic efficiency of the grid can be improved and enhanced.

9. Conclusions

In this work, we have explored the overview of the critical aspects of DSSE ranging from the conventional model-based approaches to the data-driven methods. We highlighted the main requirement any DSSE algorithm must have in terms of time, accuracy, and robustness. Due to the lack of sufficient measurements to guarantee observability in the DSSE, the model-based DSSE usually have their accuracy compromised except complemented with pseudo-measurements extracted from historical records. Another point of interest is how these pseudo-measurements are generated which is still an area of active research. Furthermore, the complexity of the DSSE models in terms of non-linearity can be relaxed in various ways: using phasor measurements, choice of the state vector, linearization, and convexification. Another area gaining traction is the application of compressive sensing to DSSE. This naturally has the advantage of working with sparse measurements which is typical of distribution systems. Finally, with low observability and few measurements, the area of matrix and tensor completion is being employed as a data-driven model-based approach to look into the challenges of DSSE. Finally, since the distribution system states are envisaged to be changing dynamically due to the presence of renewable energy resources, the idea of data-driven state forecasting based on machine and deep learning methods is being explored for quick decision-making for critical operations in the distribution system.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this article would like to acknowledge the King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals’ support in conducting this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmad, T.; Madonski, R.; Zhang, D.; Huang, C.; Mujeeb, A. Data-driven probabilistic machine learning in sustainable smart energy/smart energy systems: Key developments, challenges, and future research opportunities in the context of smart grid paradigm. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 160, 112128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, Y.; Ishii, H.; Hayashi, Y. Designing sustainable smart cities: cooperative energy management systems and applications. IEEJ Transactions on Electrical and Electronic Engineering 2020, 15, 1256–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Táczi, I.; Sinkovics, B.; Vokony, I.; Hartmann, B. The challenges of low voltage distribution system state estimation—an application oriented review. Energies 2021, 14, 5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abur, A.; Exposito, A.G. Power system state estimation: theory and implementation; CRC press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kotha, S.K.; Rajpathak, B. Power system state estimation using non-iterative weighted least square method based on wide area measurements with maximum redundancy. Electric power systems research 2022, 206, 107794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garces, A. Mathematical programming for power systems operation: From theory to applications in python; John Wiley & Sons, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ashok, A.; Govindarasu, M.; Ajjarapu, V. MODEL-BASED ANOMALY DETECTION FOR POWER SYSTEM STATE ESTIMATION. Advances in Electric Power and Energy: Static State Estimation 2020, 99–121. [Google Scholar]

- Padmanaban, S.; Khan, B.; Mahela, O.P.; Alhelou, H.H.; Rajkumar, S. Active Electrical Distribution Network: Issues, Solution Techniques, and Applications Academic Press. 2022.

- Brinkmann, B.; Negnevitsky, M. A probabilistic approach to observability of distribution networks. IEEE Transactions on power systems 2016, 32, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, Y.; Venkataramanan, V.; Annaswamy, A.M.; Dubey, A.; Srivastava, A.K. Improved Observability in Distribution Grids Using Correlational Measurements. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 27320–27329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, C.; Huang, J.; Chen, L. Gradient-based multi-area distribution system state estimation. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2020, 11, 5325–5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, R.; Abur, A. Three-phase Linear State Estimation Based on SCADA and PMU Measurements. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Europe (ISGT Europe). IEEE; 2021; pp. 01–05. [Google Scholar]

- Muscas, C.; Sulis, S.; Angioni, A.; Ponci, F.; Monti, A. Impact of different uncertainty sources on a three-phase state estimator for distribution networks. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2014, 63, 2200–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira-De Jesus, P.M.; Rodriguez, N.A.; Celeita, D.F.; Ramos, G.A. PMU-based system state estimation for multigrounded distribution systems. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2020, 36, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestav, K.R.; Luengo-Rozas, J.; Tong, L. Bayesian state estimation for unobservable distribution systems via deep learning. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2019, 34, 4910–4920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Yin, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, D. Real-time robust forecasting-aided state estimation of power system based on data-driven models. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2021, 125, 106412. [Google Scholar]

- Della Giustina, D.; Pau, M.; Pegoraro, P.A.; Ponci, F.; Sulis, S. Electrical distribution system state estimation: measurement issues and challenges. IEEE Instrumentation & Measurement Magazine 2014, 17, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, D.; Han, Q.L.; Ge, X.; Wang, J. Secure state estimation and control of cyber-physical systems: A survey. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems 2020, 51, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaman, S.; Mazumder, M.R.R.; Ahmed, M.I.; Rahman, A.A.M. Forecasting-Aided state estimation for power distribution system application: Case study. In Proceedings of the 2019 5th International Conference on Advances in Electrical Engineering (ICAEE). IEEE; 2019; pp. 473–478. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, R.; Geetha, S.J.; Chakrabarti, S.; Sharma, A. An L-1 Regularized Forecasting-Aided State Estimator for Active Distribution Networks. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2021, 13, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, B.C.; Melo, I.D.; Souza, M.A. Bad data detection, identification and correction in distribution system state estimation based on PMUs. Electrical Engineering 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhoush, S.; Vannoy, T.; Liyanage, K.; Whitaker, B.M.; Nehrir, H. Distribution System State Estimation and False Data Injection Attack Detection with a Multi-Output Deep Neural Network. Energies 2023, 16, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gers, J.M.; et al. Distribution system analysis and automation. Technical report, IET, 2013.

- Ahmad, F.; Rasool, A.; Ozsoy, E.; Sekar, R.; Sabanovic, A.; Elitaş, M. Distribution system state estimation-A step towards smart grid. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 81, 2659–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K.P.; Fuller, J.C.; Chassin, D.P. Multi-state load models for distribution system analysis. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2011, 26, 2425–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artale, G.; Caravello, G.; Cataliotti, A.; Cosentino, V.; Di Cara, D.; Guaiana, S.; Nguyen Quang, N.; Palmeri, M.; Panzavecchia, N.; Tinè, G. A virtual tool for load flow analysis in a micro-grid. Energies 2020, 13, 3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primadianto, A.; Lu, C.N. A review on distribution system state estimation. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2016, 32, 3875–3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasy, N.H.; Ismail, H.M. A unified approach for the optimal PMU location for power system state estimation. IEEE Transactions on power systems 2009, 24, 806–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, P.; Sezi, T.; Maun, J.C. Distribution system state estimation using unsynchronized phasor measurements. In Proceedings of the 2012 3rd IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Europe (ISGT Europe). IEEE; 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado, A.R.; Esquivel, C.R.F.; Guizar, J.G.C. SCADA and PMU measurements for improving power system state estimation. IEEE Latin America Transactions 2015, 13, 2245–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manousakis, N.M.; Korres, G.N. Optimal PMU placement for numerical observability considering fixed channel capacity—A semidefinite programming approach. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2015, 31, 3328–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaei, J.; Baharvandi, A.; Rabiee, A.; Akbari, M.A. Probabilistic PMU placement in electric power networks: An MILP-based multiobjective model. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2015, 11, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, L.; Li, J. D-PMU based applications for emerging active distribution systems: A review. Electric Power Systems Research 2020, 179, 106063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi-Sarvestani, S.; Jooshaki, M.; Fotuhi-Firuzabad, M.; Lehtonen, M. Incorporating direct load control demand response into active distribution system planning. Applied Energy 2023, 339, 120897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efkarpidis, N.; Geidl, M.; Wache, H.; Peter, M.; Adam, M. Smart Metering Applications: Main Concepts and Business Models; Vol. 88; Springer Nature, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Schlösser, T.; Angioni, A.; Ponci, F.; Monti, A. Impact of pseudo-measurements from new load profiles on state estimation in distribution grids. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference (I2MTC) Proceedings. IEEE; 2014; pp. 625–630. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Hu, C.; Sun, Y.; Lin, G. Probabilistic state estimation approach for AC/MTDC distribution system using deep belief network with non-Gaussian uncertainties. IEEE Sensors Journal 2019, 19, 9422–9430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Pal, B.; Jabr, R. Distribution system state estimation through Gaussian mixture model of the load as pseudo-measurement. IET generation, transmission & distribution 2010, 4, 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Manitsas, E.; Singh, R.; Pal, B.C.; Strbac, G. Distribution system state estimation using an artificial neural network approach for pseudo measurement modeling. IEEE Transactions on power systems 2012, 27, 1888–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adinolfi, F.; D’Agostino, F.; Morini, A.; Saviozzi, M.; Silvestro, F. Pseudo-measurements modeling using neural network and Fourier decomposition for distribution state estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies, Europe. IEEE; 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chu, C.C.; Gadh, R. Robust pseudo-measurement modeling for three-phase distribution systems state estimation. Electric Power Systems Research 2020, 180, 106138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghanpour, K.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Bu, F. A game-theoretic data-driven approach for pseudo-measurement generation in distribution system state estimation. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2019, 10, 5942–5951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsonias, A.; Asprou, M.; Hadjidemetriou, L.; Kyriakides, E. State estimation for distribution grids with a single-point grounded neutral conductor. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2020, 69, 8167–8177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Quiles, C.; Romero-Ramos, E.; de la Villa-Jaén, A.; Gómez-Expósito, A. Compensated Load Flow Solutions for Distribution System State Estimation. Energies 2020, 13, 3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Dehghanpour, K.; Wang, Z. Mitigating smart meter asynchrony error via multi-objective low rank matrix recovery. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2021, 12, 4308–4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, L. State estimation of three-phase four-conductor distribution systems with real-time data from selective smart meters. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2019, 34, 2632–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, L.; Avilés, J.; Guillen, D.; Mayo-Maldonado, J.; Valdez-Resendiz, J.; Ponce, P. Optimal micro-PMU placement and virtualization for distribution network changing topologies. Sustainable Energy, Grids and Networks 2021, 27, 100510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zufferey, T.; Hug, G. Impact of data availability and pseudo-measurement synthesis on distribution system state estimation. IET Smart Grid 2021, 4, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantin, C.d.A.; Castillo, M.; de Carvalho, B.; London, J. Using pseudo and virtual measurements in distribution system state estimation. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE PES Transmission & Distribution Conference and Exposition-Latin America (PES T&D-LA); IEEE. 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Angioni, A.; Shang, J.; Ponci, F.; Monti, A. Real-time monitoring of distribution system based on state estimation. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2016, 65, 2234–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimardani, A.; Therrien, F.; Atanackovic, D.; Jatskevich, J.; Vaahedi, E. Distribution system state estimation based on nonsynchronized smart meters. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2015, 6, 2919–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavraro, G.; Comden, J.; Dall’Anese, E.; Bernstein, A. Real-Time Distribution System State Estimation with Asynchronous Measurements. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2022, 13, 3813–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chakhchoukh, Y.; Vittal, V.; Heydt, G.T.; Logic, N.; Sturgill, S. Impact of PMU measurement buffer length on state estimation and its optimization. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2012, 28, 1657–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Majeed, A.; Tenbohlen, S.; Rudion, K. Effects of state estimation accuracy on the voltage control of low voltage grids. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Symposium on Smart Electric Distribution Systems and Technologies (EDST). IEEE; 2015; pp. 526–530. [Google Scholar]

- Pegoraro, P.A.; Angioni, A.; Pau, M.; Monti, A.; Muscas, C.; Ponci, F.; Sulis, S. Bayesian approach for distribution system state estimation with non-Gaussian uncertainty models. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2017, 66, 2957–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscas, C.; Pau, M.; Pegoraro, P.A.; Sulis, S. Effects of measurements and pseudomeasurements correlation in distribution system state estimation. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2014, 63, 2813–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppanen, J.; Reno, M.J.; Thakkar, M.; Grijalva, S.; Harley, R.G. Leveraging AMI data for distribution system model calibration and situational awareness. IEEE transactions on smart grid 2015, 6, 2050–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimian, B.; Biswas, R.S.; Moshtagh, S.; Pal, A.; Tong, L.; Dasarathy, G. State and topology estimation for unobservable distribution systems using deep neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2022, 71, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, Z.; Ma, S.; Khorsand, M.; Vittal, V. Simultaneous robust state estimation, topology error processing, and outage detection for unbalanced distribution systems. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdoub, M.; Boukherouaa, J.; Cheddadi, B.; Belfqih, A.; Sabri, O.; Haidi, T. A review on distribution system state estimation techniques. In Proceedings of the 2018 6th International Renewable and Sustainable Energy Conference (IRSEC). IEEE; 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, A.J.; Wollenberg, B.F.; Sheblé, G.B. Power generation, operation, and control; John Wiley & Sons, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rossoni, A.; Braunstein, S.H.; Trevizan, R.D.; Bretas, A.S.; Bretas, N.G. Contribution to distribution systems technical and nontechnical losses estimation using WLS state estimator. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Power &, Energy Society General Meeting. IEEE; 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Manousakis, N.M.; Korres, G.N. Application of State Estimation in Distribution Systems with Embedded Microgrids. Energies 2021, 14, 7933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therrien, F.; Kocar, I.; Jatskevich, J. A unified distribution system state estimator using the concept of augmented matrices. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2013, 28, 3390–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langner, A.L.; Abur, A. Formulation of three-phase state estimation problem using a virtual reference. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2020, 36, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghanpour, K.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Yuan, Y.; Bu, F. A survey on state estimation techniques and challenges in smart distribution systems. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2018, 10, 2312–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göl, M.; Abur, A. LAV based robust state estimation for systems measured by PMUs. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2014, 5, 1808–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Chen, Y.; Yong, C.; Ma, X.; Kong, J. Stepwise robust distribution system state estimation considering PMU measurement. Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy 2019, 11, 025506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habiballah, I.O.; Xia, Y. LEAST-TRIMMED-ABSOLUTE-VALUE STATE ESTIMATOR. Advances in Electric Power and Energy: Static State Estimation 2020, 255–294. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Li, P.; Wang, C.; Yu, H.; Ji, H.; Xi, W.; Wu, J. Robust State Estimation of Active Distribution Networks with Multi-Source Measurements. Journal of Modern Power Systems and Clean Energy 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, M.S.; Habiballah, I.O. Hybridization of WLS and LMR: a Robust Solution for Power System State Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Sustainable Power and Energy Conference (iSPEC). IEEE; 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Fotopoulou, M.; Petridis, S.; Karachalios, I.; Rakopoulos, D. A Review on Distribution System State Estimation Algorithms. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 11073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mount, D.M.; Netanyahu, N.S.; Piatko, C.D.; Silverman, R.; Wu, A.Y. On the least trimmed squares estimator. Algorithmica 2014, 69, 148–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekatos, V.; Wang, G.; Zhu, H.; Giannakis, G.B. PSSE redux: convex relaxation, decentralized, robust, and dynamic solvers. Advances in Electric Power and Energy: Static State Estimation 2020, 171–208. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Yuan, P.; Du, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, J. Robust distributed state estimation of active distribution networks considering communication failures. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2020, 118, 105732. [Google Scholar]

- Damavandi, M.G.; Krishnamurthy, V.; Martí, J.R. Robust meter placement for state estimation in active distribution systems. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2015, 6, 1972–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garces, A. A linear three-phase load flow for power distribution systems. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2015, 31, 827–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farajollahi, M.; Shahsavari, A.; Mohsenian-Rad, H. Linear distribution system state estimation using synchrophasor data and pseudo-measurement. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Smart Grid Synchronized Measurements and Analytics (SGSMA). IEEE; 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Haughton, D.A.; Heydt, G.T. A linear state estimation formulation for smart distribution systems. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2012, 28, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolognani, S.; Dörfler, F. Fast power system analysis via implicit linearization of the power flow manifold. In Proceedings of the 2015 53rd Annual Allerton Conference on Communication, Control, and Computing (Allerton); IEEE. 2015; pp. 402–409. [Google Scholar]

- Zohrizadeh, F.; Josz, C.; Jin, M.; Madani, R.; Lavaei, J.; Sojoudi, S. A survey on conic relaxations of optimal power flow problem. European journal of operational research 2020, 287, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Turitsyn, K.; Molzahn, D.K.; Roald, L.A. Robust AC optimal power flow with robust convex restriction. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2021, 36, 4953–4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, R.; Lavaei, J.; Baldick, R. Convexification of power flow equations in the presence of noisy measurements. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 2019, 64, 3101–3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Madani, R.; Lavaei, J. Conic relaxations for power system state estimation with line measurements. IEEE Transactions on Control of Network Systems 2017, 5, 1193–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Giannakis, G.B.; Chen, J.; Sun, J. Distribution system state estimation: An overview of recent developments. Frontiers of Information Technology & Electronic Engineering 2019, 20, 4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhao, D.; Li, Z. Distribution system state estimation: A semidefinite programming approach. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2018, 10, 4369–4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Flueck, A. A Scalable Method for Semidefinite Programming Based Distribution System State Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/PES Transmission and Distribution Conference and Exposition (T&D); IEEE. 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Lubkeman, D.L.; Downey, M.J.; Jones, R.H. Distribution circuit state estimation using a probabilistic approach. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 1997, 12, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanin, M.; Van Acker, T.; D’hulst, R.; Van Hertem, D. Exact Modeling of Non-Gaussian Measurement Uncertainty in Distribution System State Estimation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.03029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majidi, M.; Etezadi-Amoli, M.; Livani, H. Distribution system state estimation using compressive sensing. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2017, 88, 175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Babakmehr, M.; Majidi, M.; Simoes, M.G. Compressive sensing for power system data analysis. In Big Data Application in Power Systems; Elsevier, 2018; pp. 159–178. [Google Scholar]

- Majidi, M.; Etezadi-Amoli, M.; Livani, H.; Fadali, M. Distribution systems state estimation using sparsified voltage profile. Electric Power Systems Research 2016, 136, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.S.; Natarajan, B.; Pahwa, A. Distribution grid state estimation from compressed measurements. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2014, 5, 1631–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donti, P.L.; Liu, Y.; Schmitt, A.J.; Bernstein, A.; Yang, R.; Zhang, Y. Matrix completion for low-observability voltage estimation. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2019, 11, 2520–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madbhavi, R.; Karimi, H.S.; Natarajan, B.; Srinivasan, B. Tensor completion based state estimation in distribution systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Power & Energy Society Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference (ISGT); IEEE. 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Madbhavi, R.; Natarajan, B.; Srinivasan, B. Enhanced tensor completion based approaches for state estimation in distribution systems. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2020, 17, 5938–5947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahale, S.; Karimi, H.S.; Lai, K.; Natarajan, B. Sparsity based approaches for distribution grid state estimation-a comparative study. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 198317–198327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Weng, Y.; Zhang, N. Topology identification and line parameter estimation for non-PMU distribution network: A numerical method. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2020, 11, 4440–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, V.C.; Freitas, W.; Trindade, F.C.; Santoso, S. Automated determination of topology and line parameters in low voltage systems using smart meters measurements. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2020, 11, 5028–5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Weng, Y.; Rajagopal, R. PaToPaEM: A data-driven parameter and topology joint estimation framework for time-varying system in distribution grids. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2018, 34, 1682–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbiani, E.; Nahata, P.; De Nicolao, G.; Ferrari-Trecate, G. Identification of ac distribution networks with recursive least squares and optimal design of experiment. IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology 2021, 30, 1750–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Negi, R.; Faloutsos, C.; Ilić, M.D. Robust data-driven state estimation for smart grid. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2016, 8, 1956–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargar, B.; Angioni, A.; Ponci, F.; Monti, A. Multiarea parallel data-driven three-phase distribution system state estimation using synchrophasor measurements. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2020, 69, 6186–6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamzam, A.S.; Fu, X.; Sidiropoulos, N.D. Data-driven learning-based optimization for distribution system state estimation. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2019, 34, 4796–4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, G.; Giannakis, G.B. Real-time power system state estimation and forecasting via deep unrolled neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2019, 67, 4069–4077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamzam, A.S.; Sidiropoulos, N.D. Physics-aware neural networks for distribution system state estimation. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2020, 35, 4347–4356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, G.; Giannakis, G.B. Distribution system state estimation via data-driven and physics-aware deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Data Science Workshop (DSW). IEEE; 2019; pp. 258–262. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, C.; Xu, Y. A fully data-driven method based on generative adversarial networks for power system dynamic security assessment with missing data. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2019, 34, 5044–5052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagan, A.; Liu, Y.; Bernstein, A. Decentralized low-rank state estimation for power distribution systems. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2021, 12, 3097–3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahale, S.; Natarajan, B. Bayesian Framework for Multi-Timescale State Estimation in Low-Observable Distribution Systems. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2022, 37, 4340–4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).