Submitted:

27 April 2023

Posted:

28 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Technological Treatment

2.2.1. Juice Preparation

2.2.2. Juice Fermentation Process

2.3. Analytical Method

2.3.1. Solid Soluble Content and Density of the Juices

2.3.3. Total Acidity

2.3.4. Color Parameters

2.3.5. Indication of the Number of Lactic Acid Bacteria

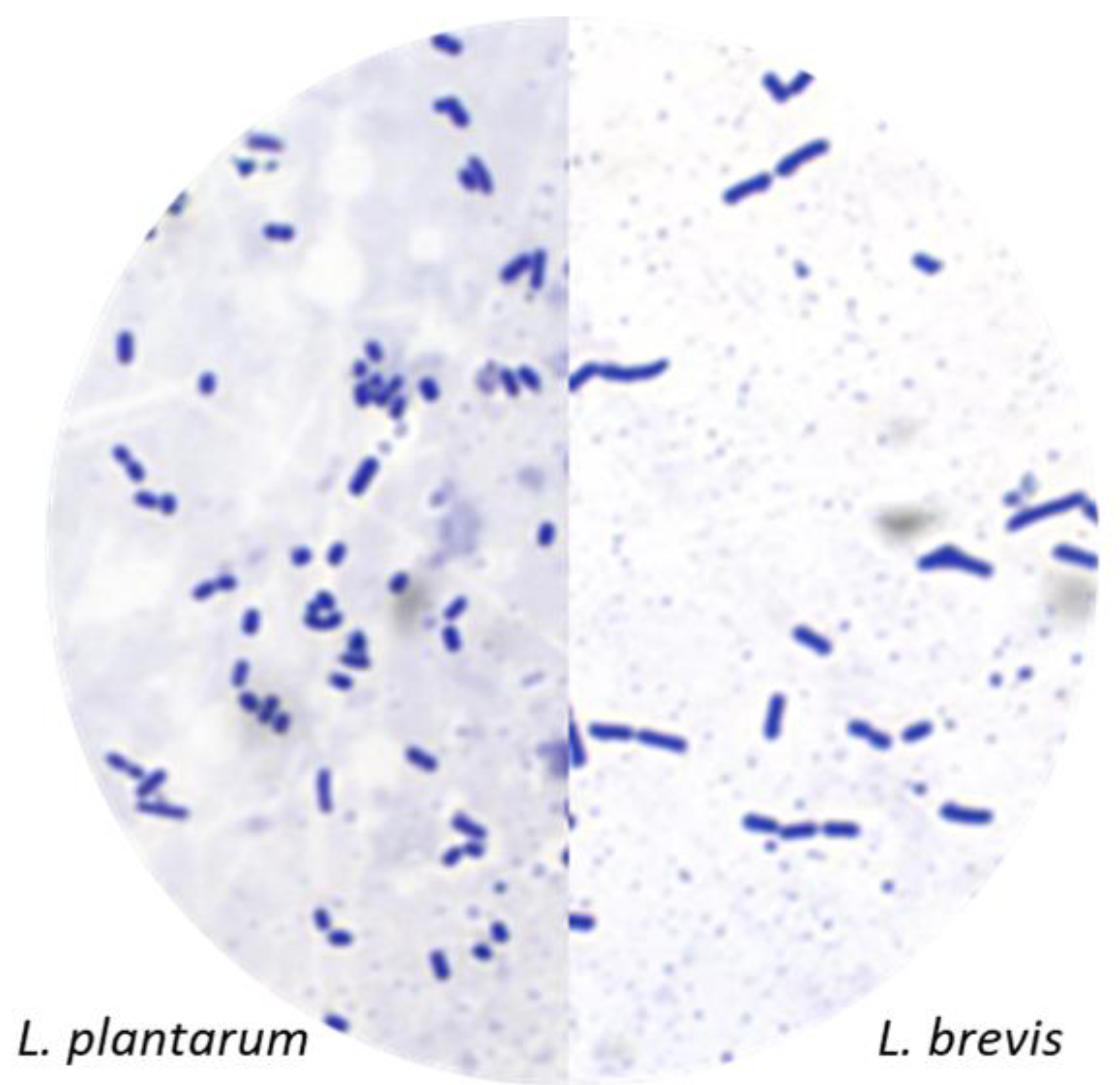

2.3.6. Bacteria Morphology

2.3.7. Pigment Content

- Betalains

- 2.

- Carotenoids analysis

2.3.8. Pigment Identification

2.4. Statistical Treatment

3. Results

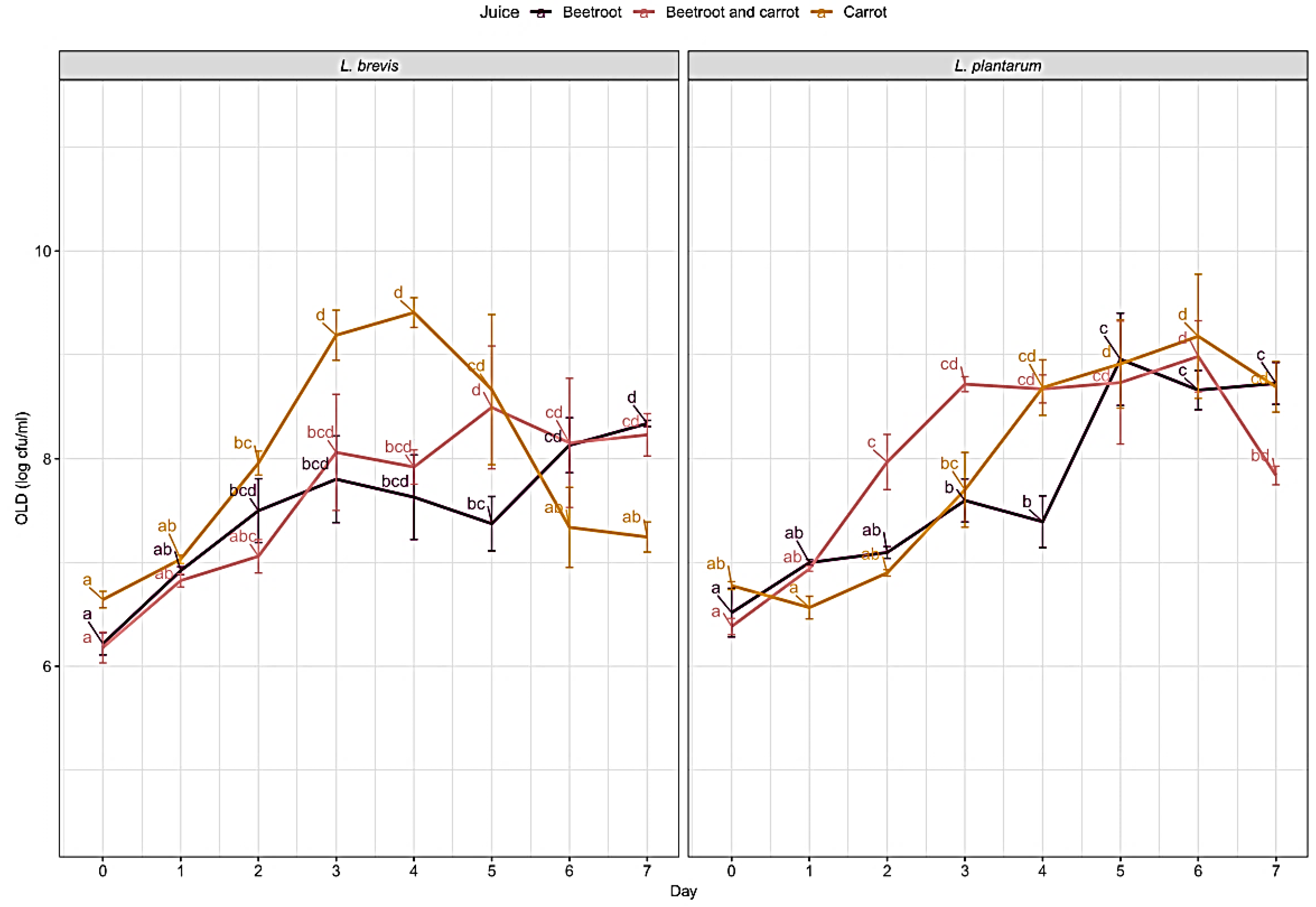

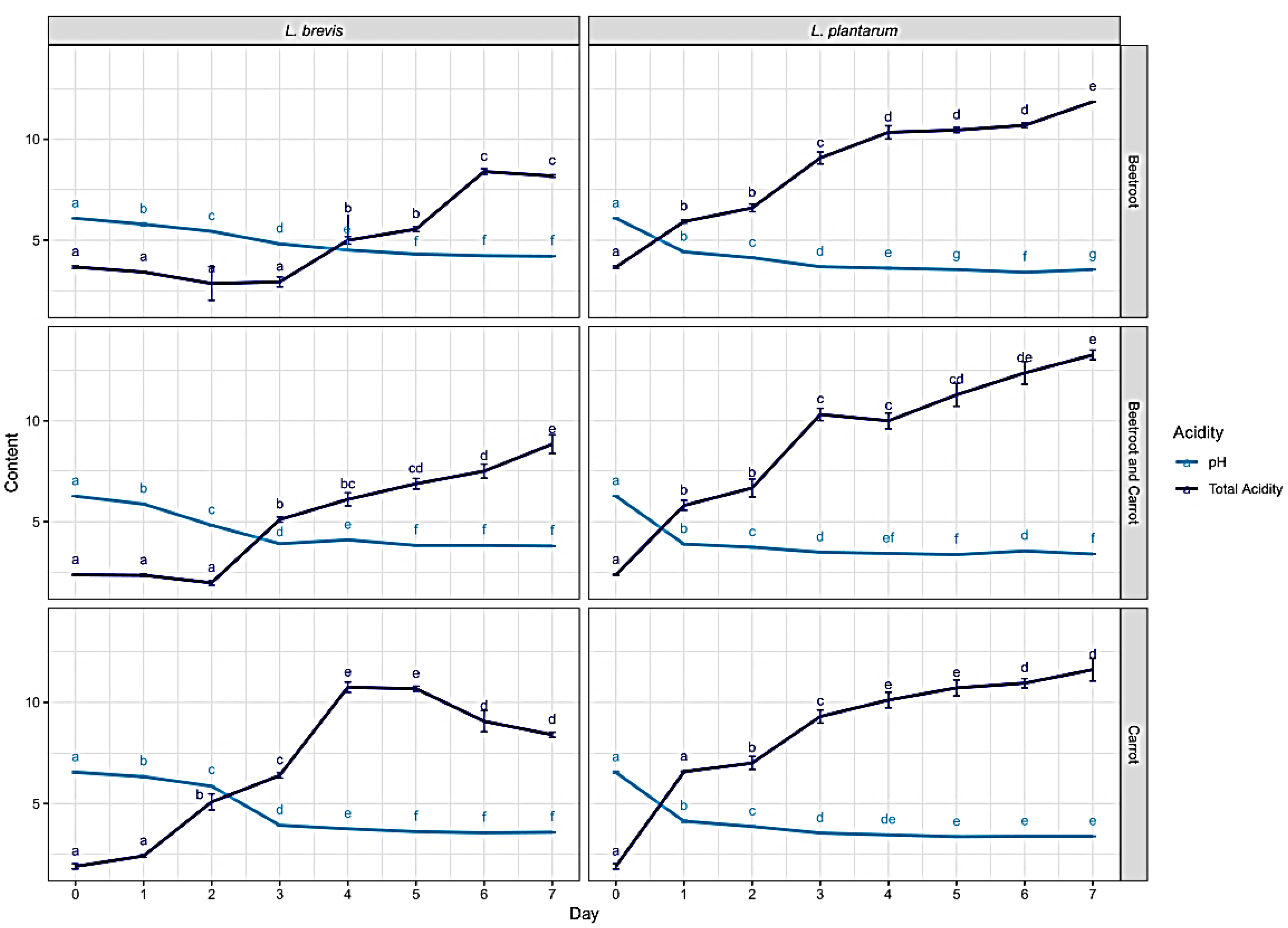

Fermentation

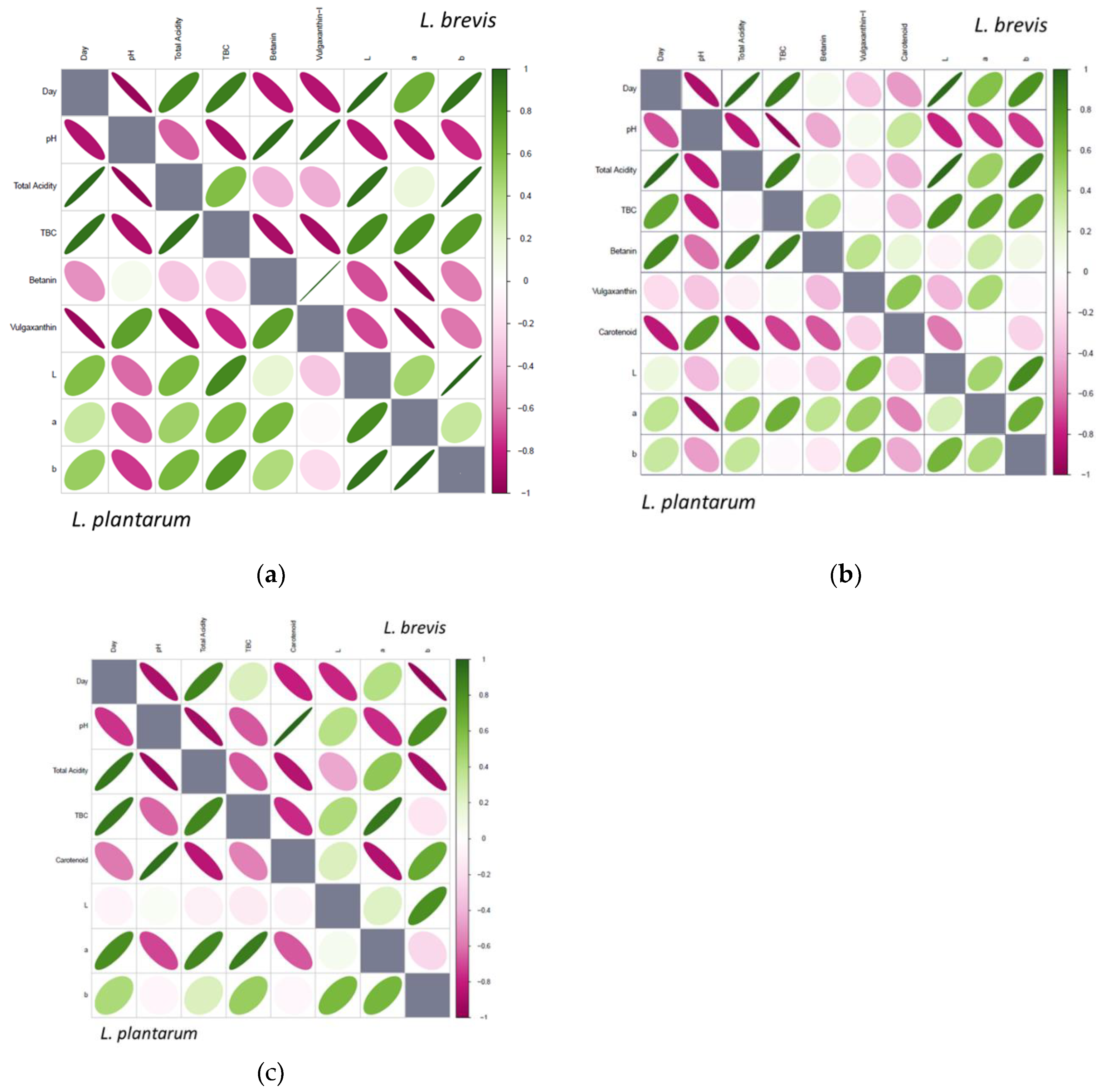

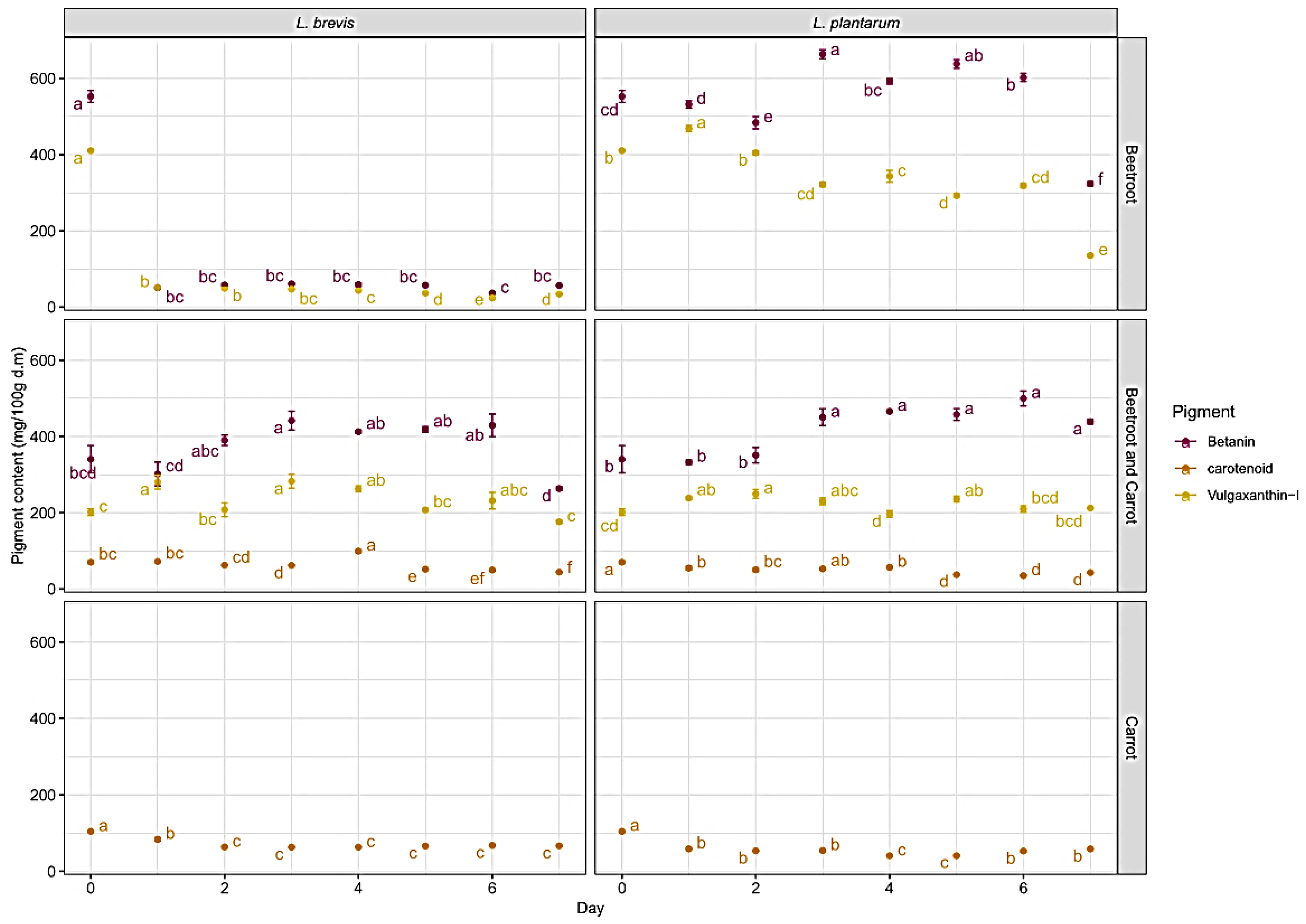

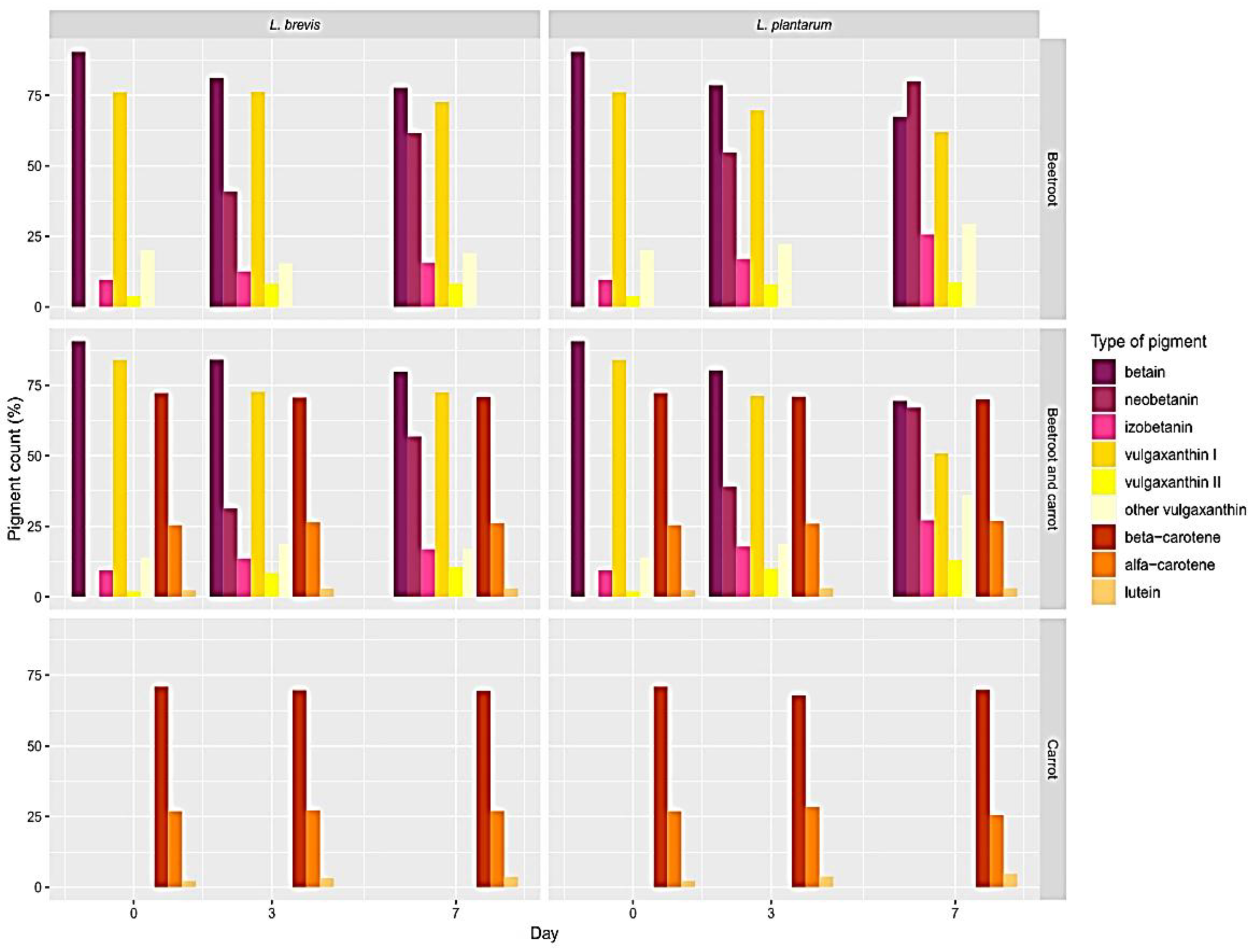

Pigment Behavior during Fermentation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khubber, S.; Marti-Quijal, F.J.; Tomasevic, I.; Remize, F.; Barba, F.J. Lactic acid fermentation as a useful strategy to recover antimicrobial and antioxidant compounds from food and by-products. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 43, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Remize, F. Lactic acid fermentation of fruit and vegetable juices and smoothies: Innovation and health aspects. In Lactic Acid Bacteria in Food Biotechnology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Güney, D.; Güngörmüşler, M. Development and comparative evaluation of a novel fermented juice mixture with probiotic strains of lactic acid bacteria and Bifidobacteria. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2021, 13, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, R.S. Chapter 7 - Fermentation. In Wine Science, 5th Ed.; Jackson, R.S., Ed.; Academic Press: Warsaw, Poland, 2020; pp. 461–572. [Google Scholar]

- Papadimitriou, K.; Alegría, Á.; Bron, P.A.; Angelis, M.d.; Gobbetti, M.; Kleerebezem, M.; Lemos, J.A.; Linares, D.M.; Ross, P.; Stanton, C.; et al. Stress Physiology of Lactic Acid Bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2016, 80, 837–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agriopoulou, S.; Stamatelopoulou, E.; Sachadyn-Król, M.; Varzakas, T. Lactic acid bacteria as antibacterial agents to extend the shelf life of fresh and minimally processed fruits and vegetables: Quality and safety aspects. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García Méndez, M.G.; Morales Martínez, T.K.; Ascacio Valdés, J.A.; Chávez González, M.L.; Flores Gallegos, A.C.; Sepúlveda, L. Application of Lactic Acid Bacteria in Fermentation Processes to Obtain Tannases Using Agro-Industrial Wastes. Fermentation 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiler, E.A.; Klaenhammer, T.R. The genomics of lactic acid bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2007, 15, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, M.; Ariff, A.B.; Rios-Solis, L.; Halim, M. Extractive fermentation of lactic acid in lactic acid bacteria cultivation: A review. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landete, J.M.; Rodríguez, H.; Curiel, J.A.; de las Rivas, B.; de Felipe, F.L.; Muñoz, R. Degradation of phenolic compounds found in olive products by Lactobacillus plantarum strains. In Olives and Olive Oil in Health and Disease Prevention; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 133–144. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Wang, M.; Zheng, Y.; Miao, K.; Qu, X. The Carbohydrate Metabolism of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wittouck, S.; Salvetti, E.; Franz, C.; Harris, H.M.B.; Mattarelli, P.; O'Toole, P.W.; Pot, B.; Vandamme, P.; Walter, J.; et al. A taxonomic note on the genus Lactobacillus: Description of 23 novel genera, emended description of the genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, and union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 2782–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyereisen, M.; Mahony, J.; Lugli, G.A.; Ventura, M.; Neve, H.; Franz, C.M.; Noben, J.-P.; O’Sullivan, T.; van Sinderen, D. Isolation and Characterization of Lactobacillus brevis Phages. Viruses 2019, 11, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Guan, N.; Sun, W.; Sun, T.; Niu, L.; Li, J.; Ge, J. Protective Effect of Levilactobacillus brevis Against Yersinia enterocolitica Infection in Mouse Model via Regulating MAPK and NF-κB Pathway. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gernet, M.; Gribkova, I.; Kobelev, K.; Nurmukhanbetova, D.; Assembayeva, E. Biotechnological aspects of fermented drinks production on vegetable raw materials. Известия Нациoнальнoй академии наук Республики Казахстан. Серия геoлoгии и технических наук 2019, 1, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.C.; Rodrigues, F.; Antónia Nunes, M.; Vinha, A.F.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. State of the art in coffee processing by-products. In Handbook of Coffee Processing By-Products; 2017; pp. 1–26.

- Lavefve, L.; Marasini, D.; Carbonero, F. Microbial ecology of fermented vegetables and non-alcoholic drinks and current knowledge on their impact on human health. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2019, 87, 147–185. [Google Scholar]

- Sionek, B. Ocena możliwości produkcji fermentowanego soku z buraka ćwikłowego z dodatkiem szczepów bakterii probiotycznych i potencjalnie probiotycznych rodzaju Lactobacillus®. Postępy Tech. Przetwórstwa Spożywczego 2020, 1, 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Klewicka, E.; Motyl, I.; Libudzisz, Z. Fermentation of beet juice by bacteria of genus Lactobacillus sp. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2004, 218, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gościnna, K.; Walkowiak-Tomczak, D.; Czapski, J. Wpływ warunków ogrzewania roztworów koncentratu soku z buraka ćwikłowego na parametry barwy i zawartość barwników betalainowych. Apar. Badaw. I Dydakt. 2014, 19, 183–189. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Andrés, M.; Aguilera-Torre, B.; García-Serna, J. Biorefinery of discarded carrot juice to produce carotenoids and fermentation products. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.-J.; Xu, M.-M.; Gilbert, R.G.; Yin, J.-Y.; Huang, X.-J.; Xiong, T.; Xie, M.-Y. Colloid chemistry approach to understand the storage stability of fermented carrot juice. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 89, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gientka, I.; Chlebowska-Śmigiel, A.; Sawikowska, K. Zmiany jakości mikrobiologicznej soków marchwiowych podczas próby przechowalniczej. Bromatol. I Chem. Toksykol. 2012, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Michalczyk, M.; Macura, R.; Fiutak, G. Wpływ warunków przechowywania na zawartość składników bioaktywnych w nieutrwalonych termicznie sokach owocowych i warzywnych. Żywność Nauka Technol. Jakość 2017, 24, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszewska-Turak, E.; Rybak, K.; Grzybowska, E.; Konopka, E.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D. The Influence of Different Pretreatment Methods on Color and Pigment Change in Beetroot Products. Molecules 2021, 26, 3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszewska-Turak, E.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D. The influence of carrot pretreatment, type of carrier and disc speed on the physical and chemical properties of spray-dried carrot juice microcapsules. Dry. Technol. 2021, 39, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak, K.; Wiktor, A.; Pobiega, K.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D.; Nowacka, M. Impact of pulsed light treatment on the quality properties and microbiological aspects of red bell pepper fresh-cuts. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszewska-Turak, E.; Walczak, M.; Rybak, K.; Pobiega, K.; Gniewosz, M.; Woźniak, Ł.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D. Influence of Fermentation Beetroot Juice Process on the Physico-Chemical Properties of Spray Dried Powder. Molecules 2022, 27, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszewska-Turak, E.; Tracz, K.; Bielińska, P.; Rybak, K.; Pobiega, K.; Gniewosz, M.; Woźniak, Ł.; Gramza-Michałowska, A. The Impact of the Fermentation Method on the Pigment Content in Pickled Beetroot and Red Bell Pepper Juices and Freeze-Dried Powders. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Guerin, M.; Souidi, K.; Remize, F. Lactic Fermented Fruit or Vegetable Juices: Past, Present and Future. Beverages 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabłowska, B.; Piasecka-Jóźwiak, K.; Rozmierska, J.; Szkudzińska-Rzeszowiak, E. Initiated lactic acid fermentation of cucumbers from organic farm by application of selected starter cultures of lactic acid bacteria. J. Res. Appl. Agric. Eng. 2012, 57, 31. [Google Scholar]

- USDA1. Beet raw, FDC ID: 169145 Available online:. Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/169145/nutrients (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- USDA3. Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/170393/nutrients (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Niakousari, M.; Razmjooei, M.; Nejadmansouri, M.; Barba, F.J.; Marszałek, K.; Koubaa, M. Current Developments in Industrial Fermentation Processes. In Fermentation Processes: Emerging and Conventional Technologies; Koubaa, M., Barba, F.J., Roohinejad, S., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 23–96. [Google Scholar]

- Koubaa, M. Introduction to Conventional Fermentation Processes. In Fermentation Processes: Emerging and Conventional Technologies; Koubaa, M., Barba, F.J., Roohinejad, S., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sajjad, N.; Rasool, A.; Fazili, A.B.A.; Eijaz Ahmed Bhat, E. Fermentation of fruits and vegetables. Plant Arch. 2020, 20, 1338–1342. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo, C.; Wilches-Pérez, D.; Hallmann, E.; Kazimierczak, R.; Rembiałkowska, E. Organic versus conventional beetroot. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant properties. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, E.; Marszałek, K.; Lipowski, J.; Jasińska, U.; Kazimierczak, R.; Średnicka-Tober, D.; Rembiałkowska, E. Polyphenols and carotenoids in pickled bell pepper from organic and conventional production. Food Chem. 2019, 278, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazimierczak, R.; Siłakiewicz, A.; Hallmann, E.; Srednicka-Tober, D.; Rembiałkowska, E. Chemical composition of selected beetroot juices in relation to beetroot production system and processing technology. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2016, 44, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazimierczak, R.; Hallmann, E.; Lipowski, J.; Drela, N.; Kowalik, A.; Pussa, T.; Matt, D.; Luik, A.; Gozdowski, D.; Rembialkowska, E. Beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) and naturally fermented beetroot juices from organic and conventional production: Metabolomics, antioxidant levels and anticancer activity. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 94, 2618–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakin, M.; Baras, J.; Vukašinović-Sekulić, M.; Maksimović, M. The examination of parameters for lactic acid fermentation and nutritive value of fermented juice of beetroot, carrot and brewer’s yeast autolysate. J. Serbian Chem. Soc. 2004, 69, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Hlaing, M.M.; Glagovskaia, O.; Augustin, M.A.; Terefe, N.S. Fermentation by Probiotic Lactobacillus gasseri Strains Enhances the Carotenoid and Fibre Contents of Carrot Juice. Foods 2020, 9, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verce, M.; De Vuyst, L.; Weckx, S. Comparative genomics of Lactobacillus fermentum suggests a free-living lifestyle of this lactic acid bacterial species. Food Microbiol. 2020, 89, 103448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marszałek, K.; Krzyżanowska, J.; Woźniak, Ł.; Skąpska, S. Kinetic modelling of polyphenol oxidase, peroxidase, pectin esterase, polygalacturonase, degradation of the main pigments and polyphenols in beetroot juice during high pressure carbon dioxide treatment. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 85, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanguler, H.; Cankaya, A.; Agcam, E.; Uslu, H. Effect of temperature and production method on some quality parameters of fermented carrot juice (Shalgam). Food Biosci. 2021, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumbas Šaponjac, V.; Čanadanović-Brunet, J.; Ćetković, G.; Jakišić, M.; Vulić, J.; Stajčić, S.; Šeregelj, V. Optimisation of Beetroot Juice Encapsulation by Freeze-Drying. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2020, 70, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, T.C.; Klososki, S.J.; Rosset, M.; Barão, C.E.; Marcolino, V.A. 14 - Fruit Juices as Probiotic Foods. In Sports and Energy Drinks; Grumezescu, A.M., Holban, A.M., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: 2019; pp. 483–513.

- Marszałek, K.; Woźniak, Ł.; Wiktor, A.; Szczepańska, J.; Skąpska, S.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D.; Saraiva, J.A.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J. Emerging Technologies and Their Mechanism of Action on Fermentation. In Fermentation Processes: Emerging and Conventional Technologies; Koubaa, M., Barba, F.J., Roohinejad, S., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 117–144. [Google Scholar]

- Czyżowska, A.; Klewicka, E.; Libudzisz, Z. The influence of lactic acid fermentation process of red beet juice on the stability of biologically active colorants. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2006, 223, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, T.; Wiczkowski, W. The effects of boiling and fermentation on betalain profiles and antioxidant capacities of red beetroot products. Food Chem. 2018, 259, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyżowska, A.; Siemianowska, K.; Śniadowska, M.; Nowak, A. Bioactive Compounds and Microbial Quality of Stored Fermented Red Beetroots and Red Beetroot Juice. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2020, 70, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stintzing, F.C.; Conrad, J.; Klaiber, I.; Beifuss, U.; Carle, R. Structural investigations on betacyanin pigments by LC NMR and 2D NMR spectroscopy. Phytochemistry 2004, 65, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Day | Beetroot juice | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | ||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| Extract (°Brix) | 10.4±0.2a | 10.9±0.1b | 10.9±0.1b | 10.9±0.1b | 10.8±0.1b | 11.0±0.1b | 10.6±0.1a | 10.7±0.2a | |

| Density (kg/m3) | 1041±0a | 1041±1a | 1040±1a | 1045±0cd | 1043±1b | 1046±0d | 1045±0bc | 1044±0bcd | |

| Color | L* | 2.5±0.1a | 2.4±0.1a | 2.8±0.1b | 2.8±0.1b | 3.1±0.1c | 4.1±0.1d | 3.1±0.1c | 3.1±0.0c |

| a* | 7.8±0.2a | 7.6±0.4a | 9.7±0.2c | 10.6±0.3d | 10.2±0.2cd | 12.5±0.2e | 10.4±0.2d | 8.6±0.2b | |

| b* | 1.4±0.1a | 1.6±0.3ab | 1.8±0.1b | 1.9±0.1b | 1.6±0.2ab | 2.4±0.1c | 1.9±0.1b | 1.7±0.1b | |

| Day | A mix of beetroot and carrot juice | ||||||||

| Fresh | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | ||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| Extract (°Brix) | 10.0±0.2a | 10.5±0.1bc | 10.6±0.2bc | 10.6±0.1bc | 10.5±0.3bc | 10.3±0.2b | 10.2±0.1c | 10.4±0.1b | |

| Density (kg/m3) | 1033±1b | 1030±2a | 1030±0a | 1036±0de | 1043±0f | 1035±0cd | 1037±0e | 1034±0c | |

| Color | L* | 8.1±0.0ab | 8.8±0.3c | 8.8±0.1cd | 8.2±0.1b | 8.4±0.1b | 9.1±0.1d | 7.9±0.1a | 8.9±0.1cd |

| a* | 15.5±0.0a | 24.6±0.1f | 24.5±0.2ef | 24.9±0.2f | 24.1±0.3de | 23.0±0.1c | 23.8±0.1d | 22.3±0.2b | |

| b* | 6.3±0.0a | 7.4±0.0d | 7.2±0.1d | 7.0±0.3d | 6.3±0.1ba | 7.0±0.1cd | 6.7±0.1bc | 7.8±0.2e | |

| Day | Carrot juice | ||||||||

| Fresh | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | ||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| Extract (°Brix) | 9.7±0.1a | 10.5±0.0b | 10.6±0.1bc | 10.8±0.0c | 10.6±0.3bc | 10.5±0.3b | 10.4±0.1b | 10.9±0.1c | |

| Density (kg/m3) | 1033±1bc | 1033±1bc | 1031±2a | 1031±0ab | 1030±1a | 1036±0d | 1035±1cd | 1032±1ab | |

| Color | L* | 33.7±0.0cd | 34.1±0.5de | 34.6±0.1e | 32.5±0.2a | 32.8±0.2ab | 35.3±0.1f | 33.2±0.1bc | 33.6±0.1c |

| a* | 23.0±0.0a | 23.5±0.1b | 23.5±0.0b | 25.3±0.3c | 25.1±0.3c | 27.1±0.1e | 26.0±0.3d | 25.4±0.2c | |

| b* | 36.5±0.2b | 35.5±0.1a | 35.6±0.0a | 35.4±0.5a | 35.2±0.3a | 38.4±0.1c | 36.8±0.3b | 36.6±0.2b | |

| Day | Beetroot juice | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh | Levilactobacillus brevis | ||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| Extract (°Brix) | 10.4±0.2c | 10.9±0.3a | 10.9±0.2ab | 10.8±0.2ab | 10.8±0.3ab | 10.6±0.1bc | 10.3±0.1cd | 10.1±0.1d | |

| Density (kg/m3) | 1041±0a | 1040±1a | 1040±3a | 1041±1a | 1043±0a | 1041±1a | 1053±0b | 1041±0a | |

| Color | L* | 2.5±0.1a | 2.5±0.1a | 2.8±0.2b | 3.7±0.1c | 5.3±0.0d | 5.1±0.1e | 4.0±0.0f | 7.5±0.1g |

| a* | 7.8±0.2b | 7.9±0.3a | 7.4±0.3a | 10.5±0.2d | 12.9±0.e | 10.1±0.0c | 10.9±0.2d | 9.7±0.0c | |

| b* | 1.4±0.1a | 1.5±0.2a | 1.0±0.1a | 1.8±0.1b | 3.6±0.1d | 3.3±0.1d | 2.5±0.1c | 5.7±0.1e | |

| Day | A mix of beetroot and carrot juice | ||||||||

| Fresh | Levilactobacillus brevis | ||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| Extract (°Brix) | 10.0±0.2a | 10.2±0.1b | 10.5±0.1a | 10.7±0.0c | 10.7±0.1c | 10.7±0.2c | 10.6±0.1c | 10.4±0.1abc | |

| Density (kg/m3) | 1033±1ab | 1033±2abc | 1031±0a | 1035±0c | 1034±0bc | 1032±0ab | 1033±1ab | 1045±0d | |

| Color | L* | 8.1±0.0a | 8.2±0.1a | 8.2±0.1a | 8.6±0.4ab | 8.6±0.5ab | 8.9±0.3bc | 9.3±0.4cd | 9.6±0.1d |

| a* | 15.5±0.0a | 19.6±0.2c | 19.8±0.2c | 22.4±0.3f | 21.5±0.1e | 18.8±0.1b | 21.1±0.2d | 21.0±0.1d | |

| b* | 6.3±0.0a | 6.0±0.2c | 6.0±0.2c | 8.2±0.5f | 8.0±0.6e | 6.6±0.2b | 8.9±0.3d | 9.0±0.1d | |

| Day | Carrot juice | ||||||||

| Fresh | Levilactobacillus brevis | ||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| Extract (°Brix) | 9.7±0.1a | 10.8±0.2cd | 10.7±0.1bc | 11.0±0.1d | 10.8±0.1cd | 10.4±0.1bc | 10.5±0.0bc | 10.3±0.1b | |

| Density (kg/m3) | 1033±1e | 1029±0d | 1022±0b | 1025±1c | 1022±0b | 1028±0d | 1035±1f | 1018±1a | |

| Color | L* | 33.7±0.0c | 37.3±0.1g | 35.7±0.2f | 34.1±0.2d | 31.7±0.2a | 33.2±0.0b | 34.6±0.0e | 32.0±0.2a |

| a* | 23.0±0.0a | 23.5±0.2a | 25.0±0.3b | 25.9±0.3c | 22.8±0.5a | 24.6±0.1b | 27.7±0.1d | 24.4±0.5b | |

| b* | 36.5±0.2d | 35.3±0.3c | 37.9±0.3e | 35.5±0.3c | 30.1±0.6a | 33.0±0.2b | 37.4±0.1e | 32.5±0.5b | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).