Submitted:

27 April 2023

Posted:

27 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- The use of antioxidants to minimize oxidative stress

- Active agents for the removal of harmful metabolic products

- Preconditioning methods (ischemic, hypoxic, pharmacological, and remote ischemic preconditioning) to prepare cells for a better response to the upcoming IRI.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Extraction for Pharmacologic Methods for the Prevention of Kidney IRI

2.2. Bibliometric Search Strategy

2.2.1. Analysis of the Most Frequent MeSH Keywords

2.2.2. Analysis of the Most Involved Authors in the Field of Examining the Studies in Which Various Operative Methods for Preventing Kidney Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury Are Studied

2.2.3. Analysis of the Average Publication Year of Authors

2.2.4. Analysis of Authors That Have the Most Tendency to Collaborate with Other Researcher and Have the Widest Range of Activity in Related Field

2.3. Molecular Interaction

2.4. Visualization of Inter-Molecular Interaction

2.5. Data Collection and Extraction for Intraoperative Methods for the Prevention of Kidney IRI

3. Results

3.1. Pharmacologic Methods for the Prevention of Kidney IRI: Bibliometric Search Strategy

3.1.1. The Most Frequent MeSH Keywords in Studies in Which Various Operative Methods for Preventing Kidney Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury Are Studied

3.1.2. Brito, Marcus Vinicius Henriques Is the Most Involved Authors in the Field of Examining the Studies in Which Various Operative Methods for Preventing Kidney Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury Are Studied

3.1.3. Authors That Are Interested in the Field of Examining the Studies in Which Various Operative Methods for Preventing Kidney Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury Are Studied

3.1.4. Brito, Marcus Vinicius Henriques Has the Most Tendency to Collaborate with Other Researcher and Has the Widest Range of Activity in Related Field

3.1.5. Brand New Compounds, Protein and Receptors That Have Been Undergone Studies in Which Their Role in IRI Has Been Studied

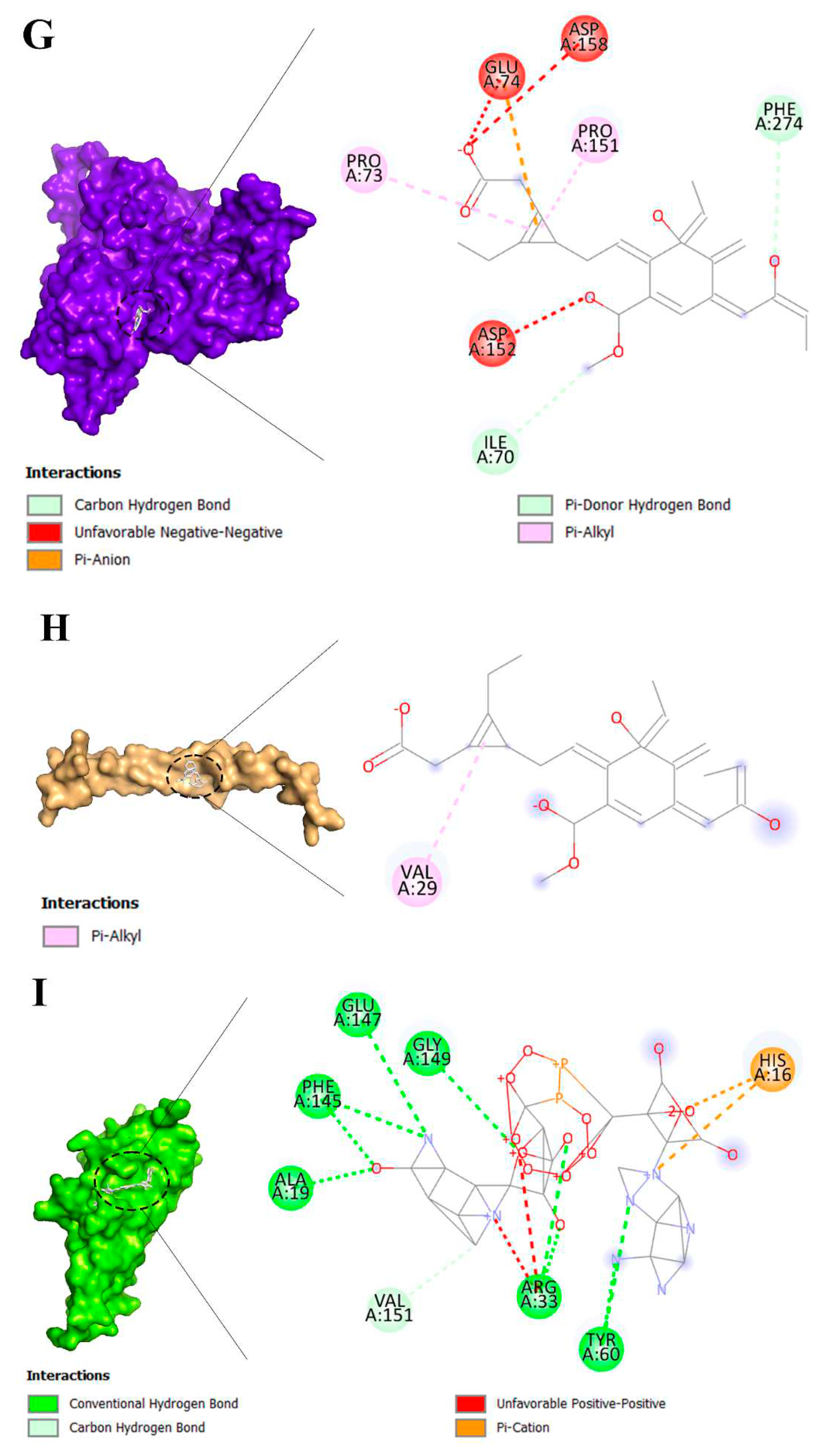

3.2. Molecular Docking Analysis of Brand-New Ligands and Receptors That Have Been Undergone Studies in Which Their Role I IRI Has Been Studied

3.3. Intraoperative Methods for the Prevention of Kidney IRI

4. Discussion

4.1. Treatment Outcome, Creatinine and Ischemia Were the Most Frequent MeSH Keywords in Related Studies

4.2. Brand New Compounds, Protein and Receptors in Recent Studies in Related Field

4.2.1. Eplerenone Affinities

4.2.2. Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide

4.3. Local Cooling of the Kidney

4.4. Renal Perfusion

4.5. Renal Capsulotomy

4.6. Ischemic Preconditioning

4.7. Tissue Engineering

4.8. Venous Blood Reperfusion

4.9. Pros and Cons of Innovative Approaches to Prevent Kidney IRI

4.10. Scoring of Prevention Methods of Kidney IRI

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Labus, A.; Niemczyk, M.; Czyzewski, L.; Fliszkiewicz, M.; Kulesza, A.; Mucha, K.; Paczek, L. Costs of Long-Term Post-Transplantation Care in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Ann Transplant 2019, 24, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, D.A.; Schnitzler, M.A.; Xiao, H.; Irish, W.; Tuttle-Newhall, E.; Chang, S.H.; Kasiske, B.L.; Alhamad, T.; Lentine, K.L. An economic assessment of contemporary kidney transplant practice. Am J Transplant 2018, 18, 1168–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, C.E.; Sorensen, P.; Petersen, K.D. In Denmark kidney transplantation is more cost-effective than dialysis. Danish Medical Journal 2014, 61, A4796. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Qiu, L.; Zhang, Z.J. Therapeutic Strategies of Kidney Transplant Ischemia Reperfusion Injury: Insight From Mouse Models. Biomed J Sci Tech Res 2019, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Eleftheriadis, T.; Pissas, G.; Filippidis, G.; Liakopoulos, V.; Stefanidis, I. Reoxygenation induces reactive oxygen species production and ferroptosis in renal tubular epithelial cells by activating aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Mol Med Rep 2021, 23, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatazin, A.; Nesterenko, I.; Zulkarnaev, A.; Shakhov, N. Pathogenetic mechanisms of the development of ischemic and reperfusion damage the kidneys as a promising target specific therapy. Russian Journal of Transplantology and Artificial Organs 2015, 17, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menke, J.; Sollinger, D.; Schamberger, B.; Heemann, U.; Lutz, J. The effect of ischemia/reperfusion on the kidney graft. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 2014, 19, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, J.P.; Vucic, D. Targeting cell death pathways for therapeutic intervention in kidney diseases. In Proceedings of the Seminars in Nephrology; 2016; pp. 153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Salvadori, M.; Rosso, G.; Bertoni, E. Update on ischemia-reperfusion injury in kidney transplantation: Pathogenesis and treatment. World J Transplant 2015, 5, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, D.M.; Watson, C.J.; Pettigrew, G.J.; Johnson, R.J.; Collett, D.; Neuberger, J.M.; Bradley, J.A. Kidney donation after circulatory death (DCD): state of the art. Kidney Int 2015, 88, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinal, H.; Dieude, M.; Hebert, M.J. Endothelial Dysfunction in Kidney Transplantation. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Alam, A.; Soo, A.P.; George, A.J.T.; Ma, D. Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury Reduces Long Term Renal Graft Survival: Mechanism and Beyond. EBioMedicine 2018, 28, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, F.; Lin, M.Z.; Zhou, H.L.; Li, H.; Sun, Q.P.; Huang, Z.Y.; Hong, L.Q.; Wang, G.; Cai, R.M.; Sun, Q.Q. Delayed graft function is correlated with graft loss in recipients of expanded-criteria rather than standard-criteria donor kidneys: a retrospective, multicenter, observation cohort study. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020, 133, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarlagadda, S.G.; Coca, S.G.; Formica, R.N., Jr.; Poggio, E.D.; Parikh, C.R. Association between delayed graft function and allograft and patient survival: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009, 24, 1039–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barba, J.; Zudaire, J.J.; Robles, J.; Tienza, A.; Rosell, D.; Berián, J.; Pascual, I. Existe un intervalo de tiempo de isquemia fría seguro para el injerto renal? Actas Urológicas Españolas 2011, 35, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schopp, I.; Reissberg, E.; Luer, B.; Efferz, P.; Minor, T. Controlled Rewarming after Hypothermia: Adding a New Principle to Renal Preservation. Clin Transl Sci 2015, 8, 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hameed, A.; Yuen, L.; Pang, T.; Rogers, N.; Hawthorne, W.; Pleass, H. Techniques to ameliorate the impact of second warm ischemic time on kidney transplantation outcomes. In Proceedings of the Transplantation Proceedings; 2018; pp. 3144–3151. [Google Scholar]

- Tennankore, K.K.; Kim, S.J.; Alwayn, I.P.; Kiberd, B.A. Prolonged warm ischemia time is associated with graft failure and mortality after kidney transplantation. Kidney Int 2016, 89, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heylen, L.; Pirenne, J.; Samuel, U.; Tieken, I.; Naesens, M.; Sprangers, B.; Jochmans, I. The Impact of Anastomosis Time During Kidney Transplantation on Graft Loss: A Eurotransplant Cohort Study. Am J Transplant 2017, 17, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.R.; Eggener, S.E. Warm ischemia less than 30 minutes is not necessarily safe during partial nephrectomy: every minute matters. In Proceedings of the Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations; 2011; pp. 826–828. [Google Scholar]

- Tasoulis, M.K.; Douzinas, E.E. Hypoxemic reperfusion of ischemic states: an alternative approach for the attenuation of oxidative stress mediated reperfusion injury. J Biomed Sci 2016, 23, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminska, D.; Koscielska-Kasprzak, K.; Chudoba, P.; Halon, A.; Mazanowska, O.; Gomolkiewicz, A.; Dziegiel, P.; Drulis-Fajdasz, D.; Myszka, M.; Lepiesza, A.; et al. The influence of warm ischemia elimination on kidney injury during transplantation - clinical and molecular study. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 36118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. VOSviewer: Visualizing scientific landscapes. Leiden University in the Netherlands 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chen, J.; Cheng, T.; Gindulyte, A.; He, J.; He, S.; Li, Q.; Shoemaker, B.A.; Thiessen, P.A.; Yu, B.; et al. PubChem 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, D1373–D1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BIOVIA, D.S. Software product name. Software version], San Diego: Dassault Systèmes,[Year]. Please note that all current BIOVIA software products start with the company name, and should be referenced as such. All products can be found at https://3ds. com/products-services/biovia/products 2019.

- Wang, Y.; Wen, J.; Almoiliqy, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yang, X.; Lu, X.; Meng, Q.; Peng, J.; Lin, Y.; et al. Sesamin Protects against and Ameliorates Rat Intestinal Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury with Involvement of Activating Nrf2/HO-1/NQO1 Signaling Pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021, 2021, 5147069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barati, A.; Rahbar Saadat, Y.; Meybodi, S.M.; Nouraei, S.; Moradi, K.; Kamrani Moghaddam, F.; Malekinejad, Z.; Hosseiniyan Khatibi, S.M.; Zununi Vahed, S.; Bagheri, Y. Eplerenone reduces renal ischaemia/reperfusion injury by modulating Klotho, NF-kappaB and SIRT1/SIRT3/PGC-1alpha signalling pathways. J Pharm Pharmacol 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azari, O.; Kheirandish, R.; Azizi, S.; Farajli Abbasi, M.; Ghahramani Gareh Chaman, S.; Bidi, M. Protective Effects of Hydrocortisone, Vitamin C and E Alone or in Combination against Renal Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Rat. Iran J Pathol 2015, 10, 272–280. [Google Scholar]

- Papi, S.; Ahmadvand, H.; Sotoodehnejadnematalahi, F.; Yaghmaei, P. The Protective Effects of Indole-Acetic Acid on the Renal Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury via Antioxidant and Antiapoptotic Properties in A Rat Model. Iran J Kidney Dis 2022, 16, 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, L.; Vafaee, M.S.; Mahmoudi, J.; Badalzadeh, R. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide emerges as a therapeutic target in aging and ischemic conditions. Biogerontology 2019, 20, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontecha-Barriuso, M.; Lopez-Diaz, A.M.; Carriazo, S.; Ortiz, A.; Sanz, A.B. Nicotinamide and acute kidney injury. 2021, 14, 2453–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panisello-Rosello, A.; Lopez, A.; Folch-Puy, E.; Carbonell, T.; Rolo, A.; Palmeira, C.; Adam, R.; Net, M.; Rosello-Catafau, J. Role of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 in ischemia reperfusion injury: An update. World J Gastroenterol 2018, 24, 2984–2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Vilet, J.M.; Ramírez, V.; Cruz, C.; Uribe, N.; Gamba, G.; Bobadilla, N.A. Renal ischemia-reperfusion injury is prevented by the mineralocorticoid receptor blocker spironolactone. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology 2007, 293, F78–F86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnahoo, K.K.; Shames, B.D.; Harken, A.H.; Meldrum, D.R. Review article: the role of tumor necrosis factor in renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Urol 1999, 162, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.Y.; Chen, S.; Du, Y. Estrogen and estrogen receptors in kidney diseases. Ren Fail 2021, 43, 619–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Chen, G.; Wyburn, K.R.; Yin, J.; Bertolino, P.; Eris, J.M.; Alexander, S.I.; Sharland, A.F.; Chadban, S.J. TLR4 activation mediates kidney ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest 2007, 117, 2847–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Ding, C.; Ding, X.; Fan, P.; Zheng, J.; Xiang, H.; Li, X.; Qiao, Y.; Xue, W.; Li, Y. Inhibition of myeloid differentiation protein 2 attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion-induced oxidative stress and inflammation via suppressing TLR4/TRAF6/NF-kB pathway. Life Sci 2020, 256, 117864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panesso, M.C.; Shi, M.J.; Cho, H.J.; Paek, J.; Ye, J.F.; Moe, O.W.; Hu, M.C. Klotho has dual protective effects on cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Kidney International 2014, 85, 855–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.C.; Moe, O.W. Klotho as a potential biomarker and therapy for acute kidney injury. Nature Reviews Nephrology 2012, 8, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khader, A.; Yang, W.L.; Kuncewitch, M.; Jacob, A.; Prince, J.M.; Asirvatham, J.R.; Nicastro, J.; Coppa, G.F.; Wang, P. Sirtuin 1 activation stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis and attenuates renal injury after ischemia-reperfusion. Transplantation 2014, 98, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, M.; Abaza, R.; Sood, A.; Ahlawat, R.; Ghani, K.R.; Jeong, W.; Kher, V.; Kumar, R.K.; Bhandari, M. Robotic kidney transplantation with regional hypothermia: evolution of a novel procedure utilizing the IDEAL guidelines (IDEAL phase 0 and 1). Eur Urol 2014, 65, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Han, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, X.; Li, T.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, G.; Han, L.; Zhang, R. A controllable double-cycle cryogenic device inducing hypothermia for laparoscopic orthotopic kidney transplantation in swine. Transl Androl Urol 2021, 10, 3046–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Han, X.; Dagvadorj, B.U.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, X.; Li, T.; Zhang, P.; Chen, Y.; Li, G.; et al. An Effective Cooling Device for Minimal-Incision Kidney Transplantation. Ann Transplant 2020, 25, e928773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longchamp, A.; Meier, R.P.H.; Colucci, N.; Balaphas, A.; Orci, L.A.; Nastasi, A.; Longchamp, G.; Moll, S.; Klauser, A.; Pascual, M.; et al. Impact of an intra-abdominal cooling device during open kidney transplantation in pigs. Swiss Med Wkly 2019, 149, w20143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, R.P.H.; Piller, V.; Hagen, M.E.; Joliat, C.; Buchs, J.B.; Nastasi, A.; Ruttimann, R.; Buchs, N.C.; Moll, S.; Vallee, J.P.; et al. Intra-Abdominal Cooling System Limits Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury During Robot-Assisted Renal Transplantation. Am J Transplant 2018, 18, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Territo, A.; Piana, A.; Fontana, M.; Diana, P.; Gallioli, A.; Gaya, J.M.; Huguet, J.; Gavrilov, P.; Rodriguez-Faba, O.; Facundo, C.; et al. Step-by-step Development of a Cold Ischemia Device for Open and Robotic-assisted Renal Transplantation. Eur Urol 2021, 80, 738–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, T.; Kwarcinski, J.; Pang, T.; Hameed, A.; Boughton, P.; O’Grady, G.; Hawthorne, W.J.; Rogers, N.M.; Wong, G.; Pleass, H.C. Protection from the second warm ischemic injury in kidney transplantation using an ex vivo porcine model and thermally insulating jackets. In Proceedings of the Transplantation Proceedings; 2021; pp. 750–754. [Google Scholar]

- Karipineni, F.; Campos, S.; Parsikia, A.; Durinka, J.B.; Chang, P.-N.; Khanmoradi, K.; Zaki, R.; Ortiz, J. Elimination of warm ischemia using the Ice Bag Technique does not decrease delayed graft function. International journal of surgery 2014, 12, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Yuan, H.; Li, X.; Ma, X.; Wang, M. Application of Hypothermic Perfusion via a Renal Artery Balloon Catheter During Robot-assisted Partial Nephrectomy and Effect on Renal Function. Acad Radiol 2019, 26, e196–e201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colli, J.L.; Dorsey, P.; Grossman, L.; Lee, B.R. Retrograde renal cooling to minimize ischemia. Int Braz J Urol 2013, 39, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saitz, T.R.; Dorsey, P.J.; Colli, J.; Lee, B.R. Induction of cold ischemia in patients with solitary kidney using retrograde intrarenal cooling: 2-year functional outcomes. Int Urol Nephrol 2013, 45, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collett, J.A.; Corridon, P.R.; Mehrotra, P.; Kolb, A.L.; Rhodes, G.J.; Miller, C.A.; Molitoris, B.A.; Pennington, J.G.; Sandoval, R.M.; Atkinson, S.J.; et al. Hydrodynamic Isotonic Fluid Delivery Ameliorates Moderate-to-Severe Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Rat Kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017, 28, 2081–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Smaalen, T.C.; Mestrom, M.G.; Kox, J.J.; Winkens, B.; van Heurn, L.W. Capsulotomy of Ischemically Damaged Donor Kidneys: A Pig Study. Eur Surg Res 2016, 57, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrler, T.; Tischer, A.; Meyer, A.; Feiler, S.; Guba, M.; Nowak, S.; Rentsch, M.; Bartenstein, P.; Hacker, M.; Jauch, K.W. The intrinsic renal compartment syndrome: new perspectives in kidney transplantation. Transplantation 2010, 89, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrler, T.; Wang, H.; Tischer, A.; Schupp, N.; Lehner, S.; Meyer, A.; Wallmichrath, J.; Habicht, A.; Mfarrej, B.; Anders, H.J.; et al. Decompression of inflammatory edema along with endothelial cell therapy expedites regeneration after renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cell Transplant 2013, 22, 2091–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinoshita, K.; Yamanaga, S.; Kaba, A.; Tanaka, K.; Ogata, M.; Fujii, M.; Hidaka, Y.; Kawabata, C.; Toyoda, M.; Uekihara, S. Optimizing Intraoperative Blood Pressure to Improve Outcomes in Living Donor Renal Transplantation. In Proceedings of the Transplantation Proceedings; 2020; pp. 1687–1694. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Qiu, T.; Liu, X.H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.S.; Zhou, J.Q. Renal ischemia-reperfusion injury attenuated by splenic ischemic preconditioning. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2018, 22, 2134–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, F.L.; Teixeira, R.K.; Yamaki, V.N.; Valente, A.L.; Silva, A.M.; Brito, M.V.; Percario, S. Remote ischemic conditioning temporarily improves antioxidant defense. J Surg Res 2016, 200, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, C.E.; Capcha, J.M.; de Braganca, A.C.; Sanches, T.R.; Gouveia, P.Q.; de Oliveira, P.A.; Malheiros, D.M.; Volpini, R.A.; Santinho, M.A.; Santana, B.A.; et al. Human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stromal cells protect against premature renal senescence resulting from oxidative stress in rats with acute kidney injury. Stem Cell Res Ther 2017, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, Y.; Nakashima, A.; Doi, S.; Ishiuchi, N.; Kanai, R.; Miyasako, K.; Masaki, T. Localization and Maintenance of Engrafted Mesenchymal Stem Cells Administered via Renal Artery in Kidneys with Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 4178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cetin, N.; Suleyman, H.; Sener, E.; Demirci, E.; Gundogdu, C.; Akcay, F. The prevention of ischemia/reperfusion induced oxidative damage by venous blood in rabbit kidneys monitored with biochemical, histopatological and immunohistochemical analysis. J Physiol Pharmacol 2014, 65, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Lan, J.; Li, J.; Lv, L. Therapeutic effect of berberine on renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats and its effect on Bax and Bcl-2. Exp Ther Med 2018, 16, 2008–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiva, N.; Sharma, N.; Kulkarni, Y.A.; Mulay, S.R.; Gaikwad, A.B. Renal ischemia/reperfusion injury: An insight on in vitro and in vivo models. Life Sci 2020, 256, 117860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ma, N.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, P.; Su, X.; Xing, Y.; An, N.; Yang, F.; Zhang, G.; et al. Targeting Ferroptosis: Pathological Mechanism and Treatment of Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021, 2021, 1587922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; Sazawa, A.; Harabayashi, T.; Shinohara, N.; Maruyama, S.; Morita, K.; Matsumoto, R.; Aoyagi, T.; Nonomura, K. Renal hypothermia with ice slush in laparoscopic partial nephrectomy: the outcome of renal function. J Endourol 2012, 26, 1483–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, D.; Caputo, P.A.; Krishnan, J.; Zargar, H.; Kaouk, J.H. Robot-assisted partial nephrectomy with intracorporeal renal hypothermia using ice slush: step-by-step technique and matched comparison with warm ischaemia. BJU Int 2016, 117, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hruby, S.; Lusuardi, L.; Jeschke, S.; Janetschek, G. Cooling mechanisms in laparoscopic partial nephrectomy: are really necessary? Arch Esp Urol 2013, 66, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arai, Y.; Kaiho, Y.; Saito, H.; Yamada, S.; Mitsuzuka, K.; Miyazato, M.; Nakagawa, H.; Ishidoya, S.; Ito, A. Renal hypothermia using ice-cold saline for retroperitoneal laparoscopic partial nephrectomy: evaluation of split renal function with technetium-99m-dimercaptosuccinic acid renal scintigraphy. Urology 2011, 77, 814–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plotnikov, E.Y. Ischemic Preconditioning of the Kidney. Bull Exp Biol Med 2021, 171, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veighey, K.V.; Nicholas, J.M.; Clayton, T.; Knight, R.; Robertson, S.; Dalton, N.; Harber, M.; Watson, C.J.E.; De Fijter, J.W.; Loukogeorgakis, S.; et al. Early remote ischaemic preconditioning leads to sustained improvement in allograft function after live donor kidney transplantation: long-term outcomes in the REnal Protection Against Ischaemia-Reperfusion in transplantation (REPAIR) randomised trial. Br J Anaesth 2019, 123, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menting, T.P.; Wever, K.E.; Ozdemir-van Brunschot, D.M.; Van der Vliet, D.J.; Rovers, M.M.; Warle, M.C. Ischaemic preconditioning for the reduction of renal ischaemia reperfusion injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017, 3, CD010777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmoghtadaei, M.; Khaboushan, A.S.; Mohammadi, B.; Sadr, M.; Farmand, H.; Hassannejad, Z.; Kajbafzadeh, A.M. Kidney tissue engineering in preclinical models of renal failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Regen Med 2022, 17, 941–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamorano, M.; Castillo, R.L.; Beltran, J.F.; Herrera, L.; Farias, J.A.; Antileo, C.; Aguilar-Gallardo, C.; Pessoa, A.; Calle, Y.; Farias, J.G. Tackling Ischemic Reperfusion Injury With the Aid of Stem Cells and Tissue Engineering. Front Physiol 2021, 12, 705256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouchakian, M.R.; Baghban, N.; Moniri, S.F.; Baghban, M.; Bakhshalizadeh, S.; Najafzadeh, V.; Safaei, Z.; Izanlou, S.; Khoradmehr, A.; Nabipour, I.; et al. The Clinical Trials of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Therapy. Stem Cells Int 2021, 2021, 1634782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshvari, M.A.; Afshar, A.; Daneshi, S.; Khoradmehr, A.; Baghban, M.; Muhaddesi, M.; Behrouzi, P.; Miri, M.R.; Azari, H.; Nabipour, I.; et al. Decellularization of kidney tissue: comparison of sodium lauryl ether sulfate and sodium dodecyl sulfate for allotransplantation in rat. Cell Tissue Res 2021, 386, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bombelli, S.; Meregalli, C.; Scalia, C.; Bovo, G.; Torsello, B.; De Marco, S.; Cadamuro, M.; Vigano, P.; Strada, G.; Cattoretti, G.; et al. Nephrosphere-Derived Cells Are Induced to Multilineage Differentiation when Cultured on Human Decellularized Kidney Scaffolds. Am J Pathol 2018, 188, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rysmakhanov, M.; Smagulov, A.; Mussin, N.; Kaliyev, A.; Zhakiyev, B.; Sultangereyev, Y.; Kuttymuratov, G. Retrograde reperfusion of renal grafts to reduce ischemic-reperfusion injury. Korean J Transplant 2022, 36, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| NO | Keyword | Occurrences | Total link strength | NO | Keyword | Occurrences | Total link strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Treatment outcome | 44 | 255 | 11 | Immunohistochemistry | 21 | 120 |

| 2 | Creatinine | 43 | 247 | 12 | Liver | 20 | 105 |

| 3 | Ischemia | 36 | 194 | 13 | Malondialdehyde | 20 | 109 |

| 4 | Time factors | 36 | 206 | 14 | Superoxide dismutase | 20 | 105 |

| 5 | Double-blind method | 35 | 204 | 15 | Protective agents | 19 | 100 |

| 6 | Biomarkers | 34 | 209 | 16 | Blood urea nitrogen | 18 | 89 |

| 7 | Apoptosis | 29 | 157 | 17 | Antioxidants | 17 | 84 |

| 8 | Oxidative stress | 29 | 187 | 18 | Lung | 17 | 80 |

| 9 | Ischemic preconditioning | 28 | 150 | 19 | Kidney diseases | 15 | 57 |

| 10 | Nephrectomy | 23 | 119 | 20 | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha | 15 | 84 |

| NO | Author | Documents | Total link strength | Average publication year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brito, Marcus Vinicius Henriques | 5 | 35 | 2016 |

| 2 | Barakat, Nashwa | 3 | 8 | 2011 |

| 3 | Corso, Carlos Otávio | 3 | 21 | 2015 |

| 4 | Costa, Felipe Lobato Da Silva | 3 | 19 | 2016 |

| 5 | Gomes, Regina De Paula Xavier | 3 | 13 | 2015 |

| 6 | Guven, Ahmet | 3 | 21 | 2008 |

| 7 | Hausenloy, Derek J | 3 | 31 | 2014 |

| 8 | Hussein, Abdel-Aziz M | 3 | 8 | 2011 |

| 9 | Korkmaz, Ahmet | 3 | 21 | 2008 |

| 10 | Santos, Emanuel Burck Dos | 3 | 21 | 2015 |

| NO | Author | Link | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brito, Marcus Vinicius Henriques | 22 | 35 |

| 2 | Hausenloy, Derek J | 27 | 31 |

| 3 | Ariti, Cono | 19 | 23 |

| 4 | Candilio, Luciano | 19 | 23 |

| 5 | Kolvekar, Shyam | 19 | 23 |

| 6 | Yellon, Derek M | 19 | 23 |

| 7 | Van Leeuwen, Paul A M | 14 | 22 |

| 8 | Van Norren, Klaske | 14 | 22 |

| 9 | Gaber, A Osama | 21 | 22 |

| 10 | Hemmerich, Stefan | 21 | 22 |

| Keyword | Occurrences | Total link strength | Average publication year | Their role in IRI | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligands | |||||

| Benzodioxole | 1 | 4 | 2018 | Amelioration | [28] |

| Eplerenone | 1 | 8 | 2018 | Amelioration | [29] |

| Hydrocortisone | 1 | 9 | 2018 | Amelioration | [30] |

| Indoles | 1 | 5 | 2019 | Amelioration | [31] |

| Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide | 1 | 13 | 2021 | Amelioration | [32] |

| Niacinamide | 1 | 13 | 2021 | Amelioration | [33] |

| Receptors | |||||

| Aldehyde dehydrogenase, mitochondrial | 1 | 4 | 2018 | Amelioration | [34] |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists | 1 | 8 | 2018 | Amplification | [35] |

| TNF receptor-associated factor 6 | 1 | 5 | 2018 | Amplification | [36] |

| Estrogen receptor alpha | 1 | 5 | 2018 | Amelioration | [37] |

| Toll-like receptor 4 | 1 | 5 | 2018 | Amplification | [38] |

| Myeloid differentiation factor 88 | 1 | 5 | 2018 | Amplification | [39] |

| Glucuronidase | 2 | 26 | 2020 | Amelioration | [40] |

| Klotho proteins | 2 | 26 | 2020 | Amelioration | [41] |

| Sirtuin 1 | 1 | 13 | 2021 | Amelioration | [42] |

| Ligands | Receptors | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD* | ER | Glucuronidase | Klotho protein | MR | MDF | Sirtuin 1 | TLR4 | TNFR | |

| Benzodioxole | -5.5 | -5.7 | -6.2 | -6.2 | -6.2 | -5.4 | -6.2 | -3.9 | -5.4 |

| Eplerenone | -13.4 | -12.9 | -11.3 | -11.7 | -12.6 | -9.2 | -11.7 | -8.8 | -9.0 |

| Hydrocortisone | -12.3 | -11.6 | -11.5 | -10.5 | -11.5 | -8.6 | -11.6 | -8.4 | -8.6 |

| Indole-3-acetic acid | -6.6 | -7.0 | -8.1 | -7.8 | -7.3 | -6.1 | -7.1 | -5.4 | -5.3 |

| Nicotinamide | -5.9 | -5.6 | -6.3 | -5.8 | -5.7 | -4.8 | -5.7 | -4.0 | -5.3 |

| NAD | -12.5 | -11.6 | -12.1 | -11.5 | -10.4 | -10.6 | -10.8 | -7.3 | -11.0 |

| Method | Patients/Model | Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local cooling of the kidney graft using a plastic bag filled with ice. | 23 patients | Long-term maintenance of optimally low temperature during kidney vascular anastomoses to reduce the negative effects of WIT, such as a low frequency of DGF and acute rejection, and optimal GFR after surgery. | [22] |

| Local cooling of the pelvis using ice slush during robotic kidney transplantation. | 7 patients | Local cooling during vascular anastomoses to reduce the negative effects of WIT. | [43] |

| A controllable double-cycle cryogenic device with a circulating cooling system (cold saline solution: 0-4°C) and warming system (warm sterile water: 30-35°C). | 20 pigs | Local cooling of the renal graft during vascular anastomoses to reduce the negative effects of WIT with simultaneous warming of the peritoneum and lumbar muscles. | [44] |

| Net-restrictive plastic jacket with a circulating cooling system that uses saline solution at a temperature of 0-4°C. | 9 patients | Local cooling of the renal graft during vascular anastomoses to reduce the negative effects of WIT. | [45] |

| Intra-abdominal cooling device with double silicone sheaths for continuous circulation of 4°C ethanol and methylene blue during open kidney transplantation. | 13 pigs | Local cooling of the renal graft during vascular anastomoses by continuously circulating 4°C ethanol and methylene blue to reduce the negative effects of WIT. | [46] |

| Intra-abdominal cooling device with double silicone sheaths for continuous circulation of 4°C ethanol and methylene blue during robotic kidney transplantation. | 23 pigs | Local cooling of the renal graft during vascular anastomoses by continuously circulating 4°C ethanol and methylene blue to reduce the negative effects of WIT. | [47] |

| A cooling device for the kidney graft made of thermal insulation materials with a cold saline circulation system. | 6 pigs 5 patients |

Long-term maintenance of optimal temperature (10-15°C) during vascular anastomoses to reduce the negative effects of WIT. | [48] |

| A thermally insulating jacket for the kidney. | 5 pigs | Long-term maintenance of optimal temperature (0-15°C) during vascular anastomoses to reduce the negative effects of WIT. | [49] |

| An ice bag for placing the kidney transplant during implantation. | 66 patients | Local cooling of the renal graft during vascular anastomoses to reduce the negative effects of WIT. | [50] |

| Kidney cooling with Ringer's solution through the renal artery with drainage through an incision in the renal vein during robotic laparoscopic resection. | 37 patients | Local intraparenchymal cooling of the kidney during its resection to reduce the negative effects of WIT. | [51] |

| Continuous retrograde cooling of the kidney with irrigated cold saline solution (1.0-1.3°C) through the ureter during ischemia. | 6 pigs | Renal pelvis continuous local cooling during clamping of the renal artery to reduce the negative effects of WIT. | [52] |

| Continuous retrograde cooling of the kidney during resection with irrigated cold saline solution through a catheterized ureter. | 10 patients | Renal pelvis local cooling of the kidney during ischemia to reduce the negative effects of WIT. | [53] |

| Gradual controlled increase in kidney temperature by machine perfusion (from 4°C to 20°C) after cold ischemia and before reperfusion. | 12 pigs | A gradual increase of the renal temperature before reperfusion reduces mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis after kidney reperfusion by half. | [16] |

| Hydrodynamic fluid injection into the renal vein (retrograde) after ischemia and reperfusion. | 5 rats | Retrograde fluid injection improves microcirculation after ischemia and reperfusion, reduces inflammatory cell infiltration of parenchyma, and leads to a rapid recovery of renal function. | [54] |

| Capsulotomy of the kidney after cold and warm ischemia. | 8 pigs | Reduction of intraparenchymal pressure and elimination of compartment syndrome after reperfusion to improve the structural and functional condition of the transplanted kidney. | [55] |

| Microcapsulotomy after ischemia and reperfusion. | 13 mice | Reducing the severity of compartment syndrome of the transplanted kidney to improve its structural and functional condition. | [56] |

| Microcapsulotomy in combination with the introduction of endothelial stem cells. | 29 mice | Combination therapy reduces morphological damage to the kidneys (tubules), infiltration of macrophages, and increases the index of proliferation and regeneration. | [57] |

| Intraoperative increase of blood pressure in the kidney. | 106 patients | Maintenance of arterial blood pressure ≥150 mmHg before and during reperfusion improves microcirculation of the kidney and is associated with early stabilization of its function. | [58] |

| Intraoperative splenic ischemic preconditioning before kidney implantation. | 18 rats | Reduction of the release of inflammatory mediators and effective reduction of serum creatinine levels. | [59] |

| Remote ischemic preconditioning of the lower limb before organ ischemia. | 18 rats | Activation of antioxidant protection of liver and kidney cells during ischemia. | [60] |

| Intraabdominal administration of MSCs after ischemia and reperfusion of both kidneys. | 18 rats | Improvement of kidney function after ischemia-reperfusion injury by reducing inflammatory and oxidative reactions. | [61] |

| Introduction of MSCs into the renal artery and renal vein after ischemia and reperfusion of the kidney. | 10 rats | Improvement of kidney function in ischemia-reperfusion injury, reduction of renal tissue fibrosis, and induced IRI. | [62] |

| Introduction of own venous blood (1 ml) into the renal artery before kidney reperfusion. | 30 rabbits | Venous blood reduces the production of reactive oxygen species and has an antioxidant effect on renal tissue after ischemia and reperfusion. | [63] |

| Type | Method | Pros | Cons | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local kidney cooling by a closed system | Local cooling of the kidney graft with a plastic bag with ice (23 patients) |

|

|

[22] |

| Local cooling of the pelvis with ice slush during robotic kidney transplantation (7 patients) |

|

|

[43] | |

| A controllable double-cycle cryogenic device with circulating cooling (cold saline solution: 0-4°C) and warming (warm sterile water: 30-35°C) system (20 pigs) |

|

|

[44] | |

| Net-restrictive plastic jacket with circulating cooling system by saline solution at a temperature of 0-4°C (9 patients) |

|

|

[45] | |

| Intra-abdominal cooling device with double silicone sheaths for continuously circulating of 4°C ethanol and methylene blue in open kidney transplantation (13 pigs) |

|

|

[46] | |

| Intra-abdominal cooling device with double silicone sheaths for continuously circulating of 4°C ethanol and methylene blue in robotic kidney transplantation (23 pigs) |

|

|

[47] | |

| Cooling device for kidney graft made of thermal insulation materials with cold saline circulation system (6 pigs – phase #0; 5 patients – phase #1) |

|

|

[48] | |

| Thermally insulating jacket for kidney (5 pigs) |

|

|

[49] | |

| An ice bag for placing a kidney transplant during implantation (66 patients) |

|

|

[50] | |

| Local cooling of the kidney with cold solution irrigation or ice slush during its laparoscopic resection (Review) |

|

|

[69] | |

| Continuous retrograde cooling of the kidney with irrigated cold saline solution (1.0-1.3°C) through the ureter during ischemia (Pig model) |

|

|

[52] | |

| Continuous retrograde cooling of the kidney during its resection with irrigated cold saline solution through a catheterized ureter (10 patients) |

|

|

[53] | |

| Renal perfusion | Cooling of the kidney with Ringer's solution through the renal artery with evacuation through an incision in the renal vein during its robotic laparoscopic resection (37 patients) |

|

|

[51] |

| Gradual controlled increase of kidney temperature by machine perfusion (from 4°C to 20°C) after cold ischemia and before reperfusion (12 pigs) |

|

|

[16] | |

| Intraoperative increase of blood pressure in the kidney (106 patients) |

|

|

[58] | |

| Hydrodynamic fluid injection into the renal vein (retrograde) after ischemia and reperfusion (5 rats) |

|

|

[54] | |

| Renal capsulotomy | Capsulotomy of the kidney after cold and warm ischemia (8 pigs) |

|

|

[55] |

| Microcapsulotomy after ischemia and reperfusion (13 mice) |

|

|

[57] | |

| Microcapsulotomy in combination with the introduction of endothelial stem cells (29 mice) |

|

|

Herrler T et al.40 | |

| Ischemic preconditioning | Intraoperative splenic ischemic preconditioning before kidney implantation (18 rats) |

|

|

[59] |

| Remote ischemic preconditioning of the lower limb before organs ischemia (18 rats) |

|

|

[60] | |

| Using the MSC | Intraabdominal administration of MSC after ischemia and reperfusion of both kidneys (18 rats) |

|

|

[61] |

| Introduction of MSC into the renal artery and renal vein after ischemia and reperfusion of the kidney (10 rats) |

|

|

[62] | |

| Venous blood reperfusion | Introduction of own venous blood (1 ml) into the renal artery before kidney reperfusion (30 rabbits) |

|

|

[63] |

| Retrograde venous kidney reperfusion before conventional arterial reperfusion (15 patients) |

|

|

[79] |

| Therapeutic approach | Clinical research (0-3) | In vivo research (0-3) | In vitro research (0-3) | Total score (0-9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ischemic preconditioning | 3 | 3 | 3 | 9 |

| Renal perfusion | 3 | 3 | 2 | 8 |

| Tissue engineering | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| Local cooling of the kidney | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Renal capsulotomy | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Venous blood reperfusion | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Therapeutic Approach | Clinical Approval | Difficulty of Test | Cost of Operation | Equipment Needed | Availability | Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Engineering | 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 17 |

| Local Cooling | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 15 |

| Renal Perfusion | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 14 |

| Ischemic Preconditioning | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 14 |

| Venous Blood Reperfusion | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 14 |

| Renal Capsulotomy | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).