Submitted:

25 April 2023

Posted:

26 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background of the Research

1.2. Problem Statement of the Research Study

1.3. Research Questiins of the Study

1.4. Research Objectives of the Study

1.5. Significance and Novelty of the Study

2. Review of Previous Literature and Hypotheses Formulation

2.1. The Theory Underpinning–Theory of Intellectual Capital (IC)

2.2. Business Ethics

2.3. Business Ethics and Organizational Performance

2.4. Dimensions of Business Ethics

2.4.1. Human Resource Management Ethic–HRE

2.4.2. Ethics in Corporate Governance

2.4.3. Ethics in Sales & Marketing

2.5. Mediation–Dimensions of Intellectual Capital

2.5.1. Human Capital–HC

2.5.2. Structural Capital–SC

2.5.3. Relational Capital–RC

2.5.4. Mediation and Multiple Serial Mediations of Variables

2.5.5. Mediation of Business Ethics

2.5.6. Multiple serial Mediation of Business ethics and Human capital

2.6. Technological Change as A Moderator

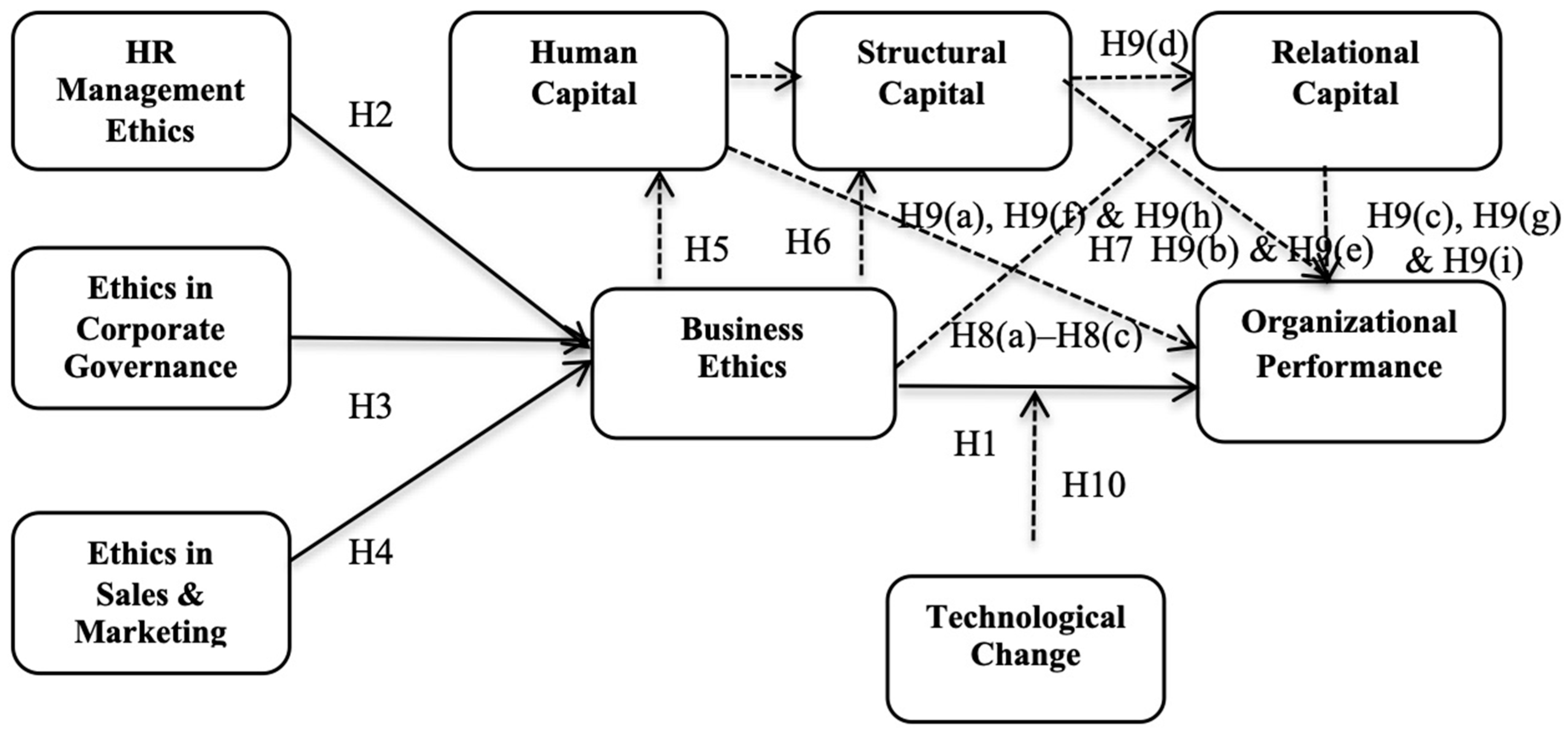

2.7. Conceptual Framework of the Study

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design of the Study

3.2. Data Collection Method and Sampling Strategy

3.3. Measurement Scaling

3.4. Estimation Techniques

3.5. Demographic Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

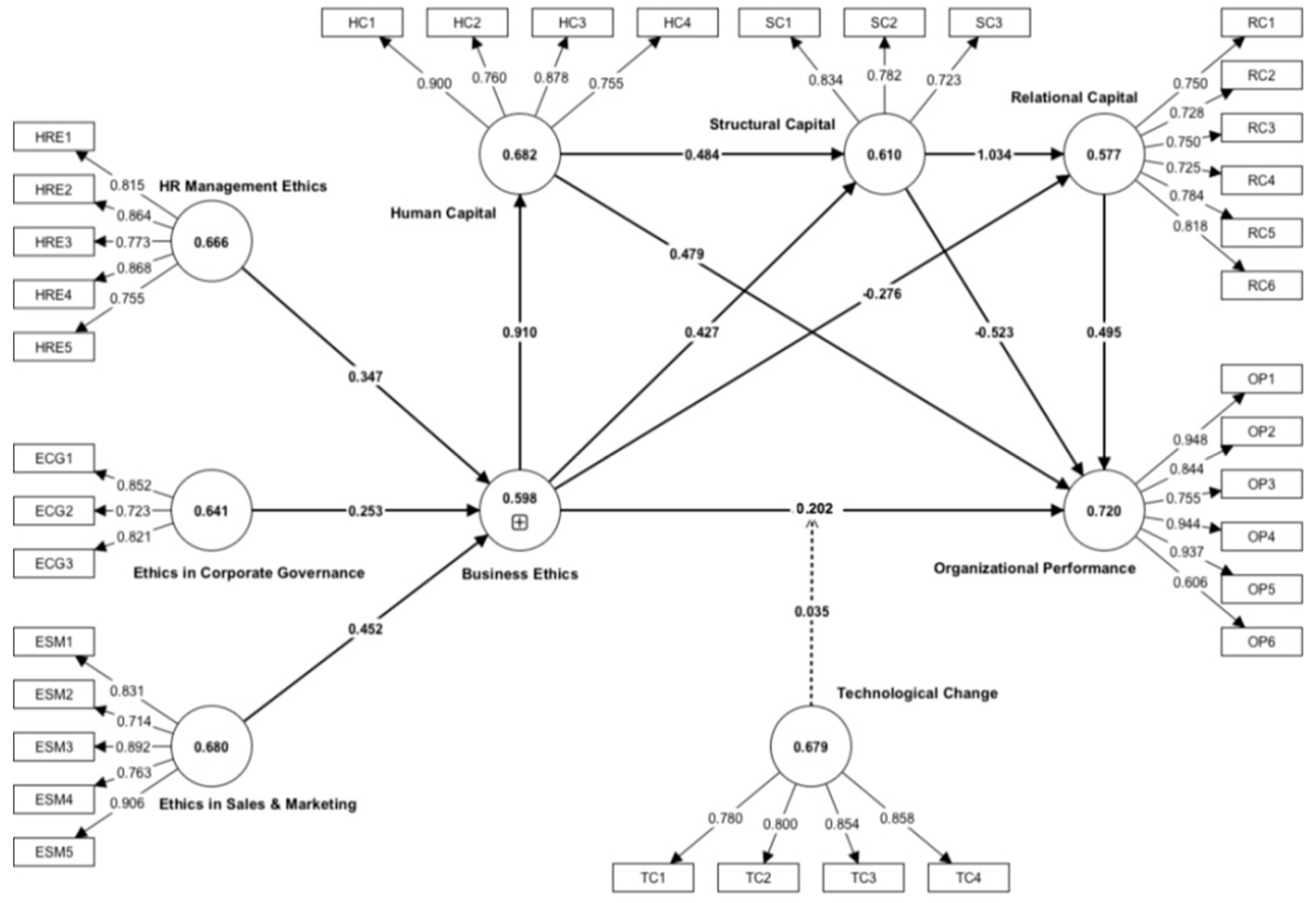

4.1.1. Outer Loading and Convergent Validity

4.1.2. Construct Reliability and Validity

4.1.3. HTMT Matrix-Discriminant Validity

4.1.4. The Fornell-Larcker Criterion

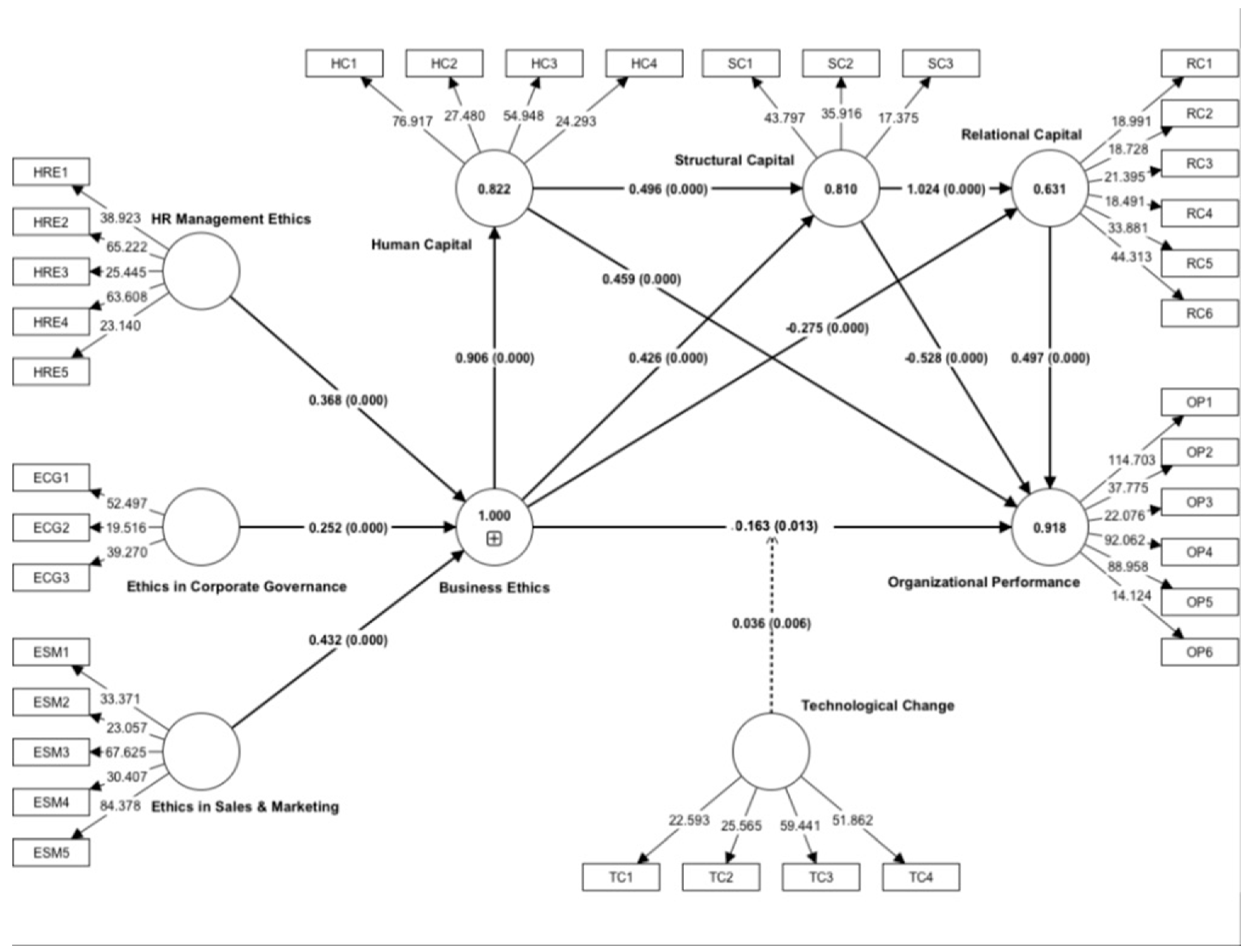

4.2. Structural Model

4.2.1. Coefficient of Variation (R2)

4.2.2. F-Square (Effect Size) Statistics

4.2.3. The Hypothesized Direct Relationship

4.2.4. The Hypothesized Multiple Serial Mediations

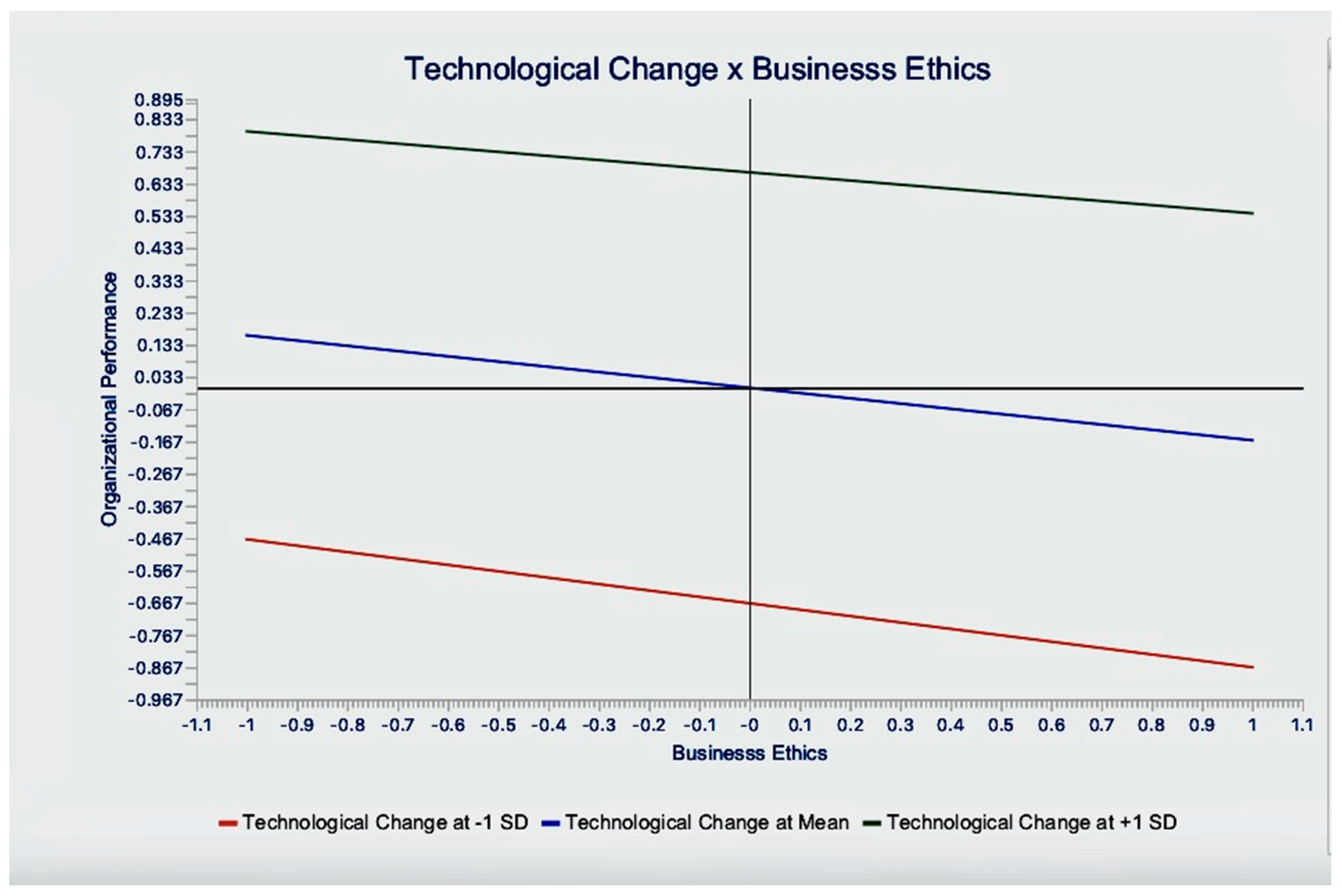

4.2.5. Moderation of Technological Change

4.2.6. Graphical Representation of Moderation of Technological Change

4.2.7. Blindfolding and Predictive Relevance (Q2)

4.2.8. Model Fitness

5. Discussions

6. Conclusion and Implications

7. Constraints of the Study and Future Directions to the Researchers

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, N.Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, J.Q.; Tang, T.L.P. Behavioral economics—Who are the investors with the most sustainable stock happiness, and why? Low aspiration, external control, and country domicile may save your lives—Monetary wisdom. Asian J. Bus. Ethics 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, M.D.K. Environmental ethical commitment (EEC): Factors that affect Malaysian business corporations. J. ASIAN Behav. Stud. 2017, 2, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.Y.; Park, S.; Barry, B. Incentive effects on ethics. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2022, 16, 297–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabana, G.C.; Kaptein, M. Team Ethical Cultures within an Organization: A Differentiation Perspective on their Existence and Relevance. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassin, Y. Business ethics research at the world's leading universities and business schools. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2022, 31, 474–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puranik, H.; Koopman, J.; Vough, H.C.; Gamache, D.L. They want what I've got (I think): The causes and consequences of attributing coworker behavior to envy. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2019, 44, 424–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamunomiebi, M.D. The Moderating Role of Organizational Culture on the Relationship between Ethical Managerial Practices and Organizational Resilience in Tertiary Health Institutions in Bayelsa State, Nigeria. J. Bus. Afr. Econ. 2018, 4, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gino, F.; Pierce, L. The abundance effect: Unethical behavior in the presence of wealth. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2009, 109, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kish-Gephart, J.J.; Harrison, D.A.; Treviño, L.K. Bad apples, bad cases, and bad barrels: Meta-analytic evidence about sources of unethical decisions at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. The changing Chinese culture and business behavior: The perspective of intertwinement between guanxi and corruption. Int. Bus. Rev. 2008, 17, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McShane, S.L.; Von Glinow, M.A. Organizational behavior (9th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Irwin: 2021.

- Sardžoska, E.G.; Tang, T.L.P. Monetary intelligence: Money attitudes—Unethical intentions, intrinsic and extrinsic job satisfaction, and coping strategies across public and private sectors in Macedonia. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Cheng, J.; Chen, Q. Socially responsible human resource management and employee ethical voice: Roles of employee ethical self-efficacy and organizational identification. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 820–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerci, M.; Radaelli, G.; Siletti, E.; Cirella, S.; Shani, A.B.R. The Impact of Human Resource Management Practices and Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Ethical Climates: An Employee Perspective. J Bus Ethics 2015, 126, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Halbusi, H.; Tang, T.L.P.; Williams, K.A.; Ramayah, T. Do ethical leaders enhance employee ethical behavior? Organizational justice and ethical climate as dual mediators and leader moral attentiveness as a moderator—Evidence from Iraq's emerging market. Asian J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 11, 105–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisman, R.; Miguel, E. Corruptions, norms, and legal enforcement: Evidence from diplomatic parking tickets. J. Political Econ. 2007, 115, 1020–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, B.; Walker, K.; Caza, A. Antecedents of sustainable organizing: A look at the relationship between organizational culture and the triple bottom line. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 1235–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Burritt, R. Business cases and corporate engagement with sustainability: Differentiating ethical motivations. Journal of Business Ethics 2018, 147, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravik, H.; Amri, H.; Febrianti, R. The Marketing Ethics of Islamic Banks: A Theoretical Study. Islam. Bank. : J. Pemikir. Dan Pengemb. Perbank. Syariah 2022, 7, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.R.; Vitorino, T.F.; Dias, Á.L.; Martinho, D.; Sousa, B.B. Developing a Commercial Ethics Framework for Analysing Marketing Campaigns. Int. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. Eng. Technol. 2022, 2022. 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirino, N.; Ferraris, A.; Miglietta, N.; Invernizzi, A.C. Intellectual capital: The missing link in the corporate social responsibility–financial performance relationship. J. Intellect. Cap. 2022, 23, 420–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalique, M.; Bontis, N.; Shaari, A.N.J.; Isa, H.M.A. Intellectual capital in small and medium enterprises in Pakistan. J. Intellect. Cap. 2015, 16, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.R.; Soomro, F.A.; Channar, Z.A.; Hashem, E.A.R.; Soomro, H.A.; Pahi, M.H.; Salleh, N.Z.M. Relationship between different Dimensions of Workplace Spirituality and Psychological Well-being: Measuring Mediation Analysis through Conditional Process Modeling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrita, M.D.R.; Bontis, N. Intellectual capital and business performance in the Portuguese banking industry. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2008, 43, 212–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.; Grang, I.; Jain, M.; Yadav, A. Improving the performance/competency of small and medium enterprises through intellectual capital. J. Intellect. Cap. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra Cisneros, M.A.; Hernandez-Perlines, F. Intellectual capital and organization performance in the manufacturing sector of Mexico. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 1818–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardini, G.H.; Lahyani, F.E. Impact of firm performance and corporate governance mechanisms on intellectual capital disclosures in CEO statements. J. Intellect. Cap. 2022, 23, 290–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Mazagatos, V.; de Quevedo-Puente, E.; Delgado-García, J.B. Human resource practices and organizational human capital in the family firm: The effect of generational stage. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 84, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofti, A.; Salehi, M.; Dashtbayaz, M.L. The effect of intellectual capital on fraud in financial statements. TQM J. 2022, 34, 651–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisyah, R.A.; Sukoco, B.M.; Anshori, M. The effect of relational capital on performance: knowledge sharing as mediation variables in supplier and buyer relation. Int. J. Logist. Syst. Manag. 2019, 34, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Vyas, V.; Roy, A. Exploring the mediating role of intellectual capital and competitive advantage on the relation between CSR and financial performance in SMEs. Soc. Responsib. J. 2017, 13, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Wang, Z.; Mohsin, M.; Jiang, W.; Abbas, H. Multidimensional perspective of green financial innovation between green intellectual capital on sustainable business: The case of Pakistan. Env. Sci. Pollut. Res 2022, 29, 5552–5568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paoloni, P.; Modaffari, G.; Paoloni, N.; Ricci, F. The strategic role of intellectual capital components in agri-food firms. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 1430–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, M.; Irshad, M.; Majeed, M.; Rizvi, S.T.H. Examining Impact of Islamic Work Ethic on Task Performance: Mediating Effect of Psychological Capital and a Moderating Role of Ethical Leadership. J Bus Ethics 2022, 180, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Puah, C.-H.; Ali, A.; Raza, S.A.; Ayob, N. Green intellectual capital, green HRM and green social identity toward sustainable environment: A new integrated framework for Islamic banks. Int. J. Manpow. 2022, 43, 614–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, A.M. Green intellectual capital and social innovation: The nexus. J. Intellect. Cap. 2022, 23, 1199–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro-Navarrete, S.; Saura, J.R.; Palacios-Marqués, D. Towards a new era of mass data collection: Assessing pandemic surveillance technologies to preserve user privacy. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 167, 120681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, J.R.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D.; Saldaña, P.Z. Exploring the challenges of remote work on Twitter users' sentiments: From digital technology development to a post-pandemic era. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokyr, J.; Vickers, C.; Ziebarth, N. The history of technological anxiety and the future of economic growth: Is this time different? J. Econ. Perspect. 2015, 29, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Cruz, P.; Du, S.; Noronha, E.; Parboteeah, K.P.; Trittin-Ulbrich, H.; Whelan, G. ; Technology, Megatrends and Work: Thoughts on the Future of Business Ethics. J Bus Ethics 2022, 180, 879–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, C. , Osborne, M. The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 114, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Restrepo, P. Automation and new tasks: How technology displaces and reinstates labor. J. Econ. Perspect. 2019, 33, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.W.; Scheller-Wolf, A. Technological unemployment, meaning in life, purpose of business, and the future of stakeholders. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 160, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häußermann, J.J.; Lütge, C. Community-in-the-loop: Towards pluralistic value creation in AI, or—Why AI needs business ethics. AI Ethics 2022, 2, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.U.; Aslam, E.; Iqbal, A. Intellectual capital efficiency and bank performance: Evidence from Islamic banks. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2022, 22, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, E. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. (2nd ed.), Oxford: Basil Blackwell: 1980.

- Edvinsson, L.; Malone, M.S. Intellectual Capital: Realizing Your Company’s True Value by Finding Its Hidden Brainpower. New York: Harper Business Press: 1997.

- Harris, L. A Theory of Intellectual Capital. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2000, 2, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kengatharan, N. A knowledge-based theory of the firm: Nexus of intellectual capital, productivity and firms’ performance. Int. J. Manpow. 2019, 40, 1056–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariff, A.H.M.; Islam, A.; van Zijl, T. Intellectual Capital and Market Performance: The Case of Multinational R&D Firms in the US. J. Dev. Areas 2016, 50, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanja, N. Intellectual Capital Theory of Entrepreneurship. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 2, 161–180. [Google Scholar]

- Nerdrum, L.; Erikson, T. Intellectual capital: A human capital perspective. J. Intellect. Cap. 2001, 2, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naixiao, Z. The intellectual capital theory and its practice in China. Int. J. Learn. Intellect. Cap. 2009, 6, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balozian, P. , Leidner, D., & Xue, B. Toward an intellectual capital cyber security theory: Insights from Lebanon. J. Intellect. Cap. 2022, 23, 1328–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrena-Martínez, J.; Livio Cricelli, L.; Esther Ferrándiz, E.; Marco Greco, M.; Grimaldi, M. Joint forces: Towards an integration of intellectual capital theory and the open innovation paradigm. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnatterly, K.; Gangloff, K.A.; Tuschke, A. CEO wrongdoing: A review of pressure, opportunity, and rationalization. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 2405–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanetsunthorn, N. Corruption and social trust: The role of corporate social responsibility. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2022, 31, 49–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Xu, S. Do bad apples do good deeds? The role of morality. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2022, 31, 562–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabiu, M.S.; Mei, T.S.; Joarder, M.H.R. Moderating role of ethical climates on HRM practices and organizational performance: A proposed conceptual model. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 7, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhadra, E.A.; Khawaldeh, S.; Aldehayyat, J. Relationship of ethical leadership, organizational culture, corporate social responsibility and organizational performance: A test of two mediation models. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaarj, S.; Abidin, Z.; Bustamam, U. Mediating role of trust on the effects of knowledge management capabilities on organizational performance. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 235, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilwan, Y.; Dirhamsyah, Pratama, I. The Impact of The Human Resource Practices on The Organizational Performance: Does Ethical Climate Matter? J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Della Torre, E. Collective voice mechanisms, HRM practices and organizational performance in Italian manufacturing firms. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-C. , Lin, C.Y.-Y. Does intellectual capital mediate the relationship between HRM and organizational performance? Perspective of a healthcare industry in Taiwan. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 20, 1965–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeboah, V.E.; Quansah, C.; Mensah, R.O. Exploring the Determinants of Workplace Ethics and Organizational Performance in the Health Sector: A Case Study of Vednan Medical Center in Kumasi, Ghana. J. Int. Coop. Dev. 2022, 5, 36–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, R. Exploring the sustainability performances of firms using environmental, social, and governance scores. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, A.; Zhang, Q. Effect of CSR and Ethical Practices on Sustainable Competitive Performance: A Case of Emerging Markets from Stakeholder Theory Perspective. J Bus Ethics 2022, 175, 837–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T. How humane entrepreneurship fosters sustainable supply chain management for a circular economy moving towards sustainable corporate performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suandi, E.; Herri, H.; Yulihasri, Y.; Syafrizal, S. An empirical investigation of Islamic marketing ethics and convergence marketing as key factors in the improvement of Islamic banks performance. J. Islam. Mark. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, S.K.; Othma, M. The impact of green human resource management practices on sustainable performance in healthcare organisations: A conceptual framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.H.; Kim, W.; Song, JH. The impact of ethical leadership on employees' in-role performance: The mediating effect of employees’ psychological ownership. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2015, 26, 385–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerónimo, H.M.; Henriques, P.L.; de Lacerda, T.C.; da Silva, F.P.; Vieira, P.R. Going green and sustainable: The influence of green HR practices on the organizational rationale for sustainability. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerci, M.; Radaelli, G. The impact of human resource management practices and corporate sustainability on organizational ethical climates: An employee perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 126, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.M. Human resource management: An applied approach. Chicago: Chicago Business Press: 2022.

- Chen, S.; Liu, W.; Zhang, G.; Wang, H.-J. Ethical human resource management mitigates the positive association between illegitimate tasks and employee unethical behavior. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2022, 31, 524–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, N.; Mahmood, N.H.N.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Ramayah, T.; Faezah, J.N.; Khalid, W. Green Human Resource Management for organisational citizenship behaviour towards the environment and environmental performance on a university campus. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, T.L.; Yean, T.F.; Leow, H.-W. ; Ability, Motivation, Opportunity-Enhancing HRM Practices and Corporate Environmental Citizenship: Revisiting the Moderating Role of Organisational Learning Capability in Malaysian Construction Companies. Int. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 24, 100–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowan, M. Fundamentals of human resource management: For competitive advantage. Chicago: Chicago Business Press: 2022.

- Chen, S.; Liu, W.; Zhang, G.; Wang, H-J. Ethical human resource management mitigates the positive association between illegitimate tasks and employee unethical behaviour. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2021, 31, 524–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyadi, L.; Cahyadi, W.; Cen, C.C.; Candrasa, L.; Pratama, I. HR practices and Corporate environmental citizenship: Mediating role of organizational ethical climate. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 6, 3083–3100. [Google Scholar]

- Omidi, A. ; Zotto, CD Socially Responsible Human Resource Management: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stajkovic, A.D.; Greenwald, J.M.; Sergent, K.S. The money priming debate revisited: A review, meta-analysis, and extension to organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 2022, 43, 1078–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essien, E.E.; Kostopoulos, I.; Lodorfos, G. Do ethical work climates influence supplier selection decisions in public organizations? The moderating roles of party politics and personal values. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, A.; Sundell, A. Money matters: The role of public sector wages in corruption prevention. Public Adm. 2020, 98, 244–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo-Cazurra, A.; Dieleman, M.; Hirsch, P.; Rodrigues, S.B.; Zyglidopoulos, S. Multinationals' misbehavior. J. World Bus. 2021, 56, 101244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelles, D. The man who broke capitalism: How Jack Welch gutted the heartland and crushed the soul of corporate America—And how do undo his legacy. New York: Simon & Schuster: 2022.

- Gbadamosi, G.; Joubert, P. Money ethic, moral conduct and work-related attitudes: Field study from the public sector in Swaziland. J. Manag. Dev. 2005, 24, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentina, E.; Tang, T.L.P. Does adolescent popularity mediate relationships between both theory of mind and love of money and consumer ethics? Appl. Psychol. : Int. Rev. 2018, 67, 723–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkundabanyanga, S.K.; Omagor, C.; Mpamizo, B.; Ntayi, J.M. The love of money, pressure to perform and unethical marketing behavior in the cosmetic industry in Uganda. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2011, 3, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Nisar, Q.A.; Mahmood, M.A.H.; Chenini, A.; Zubair, A. The role of Islamic marketing ethics towards customer satisfaction. J. Islam. Mark. 2019, 11, 1001–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escadas, M.; Jalali, M.S.; Farhangmehr, M. Why bad feelings predict good behaviours: The role of positive and negative anticipated emotions on consumer ethical decision making. Bus. Ethics: A Eur. Rev. 2019, 28, 529–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nashmi, M.M.; Almamary, A.A. The relationship between Islamic marketing ethics and brand credibility: A case of pharmaceutical industry in Yemen. J. Islam. Mark. 2017, 8, 261–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentina, E.; Daniel, C.; Tang, T.L.P. Mindfulness reduces avaricious monetary attitudes and enhances ethical consumer beliefs: Mindfulness training, timing, and practicing matter. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 173, 301–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.D. , Kieu, T.A. Ethically minded consumer behaviour in Vietnam. Asian Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 31, 609–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Wu, Q. ; Khattak, MS Intellectual capital, corporate social responsibility and sustainable competitive performance of small and medium-sized enterprises: Mediating effects of organizational innovation. Kybernetes 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S. , Kaimenakis, N. Intellectual capital and corporate performance in knowledge-intensive SMEs. Learn. Organ. 2007, 14, 241–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z.; Asghar, M.M.; Malik, M.N.; Nawaz, K. Moving towards a sustainable environment: The dynamic linkage between natural resources, human capital, urbanization, economic growth, and ecological footprint in China. Res Policy 2020, 67, 101677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez Blanco, J.M.; Montes-Botella, J. Exploring nurtured company resilience through human capital and human resource development. Int. J. Manpow 2017, 38, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldorai, K.; Kim, W.G.; Garcia, R.L.F. Top management green commitment and green intellectual capital as enablers of hotel environmental performance: The mediating role of green human resource management. Tour. Manag. 2022, 88, 104431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.; Shilton, K.; Smith, J. Business and the ethical implications of technology: Introduction to the symposium. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 160, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cremer, D.; Kasparov, G. The ethics of technology innovation: A double-edged sword? AI Ethics 2022, 2, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, D.A. Automation and Well-Being: Bridging the Gap between Economics and Business Ethics. J Bus Ethics 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesämaa, O.; Zwikael, O.; Hair Jr, J.; Huemann, M. Publishing quantitative papers with rigor and transparency. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2021, 39, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). 3rd Edition. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Inc. :.

- Parmar, V.; Channar, Z.A.; Ahmed, R.R.; Štreimikienė, D.; Pahi, M.H.; Streimikis, J. Assessing the organizational commitment, subjective vitality and burnout effects on turnover intention in private universities. Oeconomia Copernic. 2022, 13, 251–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish. New York: Guilford Publications: 2015.

- Gobo, G. Re-conceptualizing generalization: Old issues in a new frame. In Pertti Alasuutari et al. (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Social Research Methods (pp. 193–213). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications: 2008.

- Sharma, S.K.; Mudgal, S.; Thakur, K.; Gaur, R. How to Calculate Sample Size for Observational and Experimental Nursing Research Studies? Natl. J. Physiol. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, D.S. Probability and non-probability sampling-an entry point for undergraduate researchers. Int. J. Quant. Qual. Res. Methods 2021, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Hanson, W.E.; Clark Plano, V.L.; Morales, A. Qualitative research designs: Selection and implementation. Couns. Psychol. 2016, 35, 236–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage: 2018. [CrossRef]

- Zikmund, W.G.; Babin, B.J.; Carr, J.C.; Griffin, M. Business Research Methods. (8th ed.). Canada: South-Western Cengage Learning: 2010.

- Afifi, A.; May, S.; Donatello, R.; Clark, V.A. Practical Multivariate Analysis, (6th ed.). Chapman and Hall/CRC: 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.R.; Zaidi, E.Z.; Alam, S.H.; Štreimikienė, D.; Parmar, V. Effect of Social Media Marketing of Luxury Brands on Brand Equity, Customer equity and Customer Purchase Intention. Amfiteatru Econ. 2023, 25, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T.K.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Straub, D.W.; Ketchen, D.J.; Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Calantone, R.J. Common beliefs and reality about PLS: Comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 17, 182–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Thiele, K.O.; Gudergan, S.P. Estimation issues with PLS and CBSEM: Where the bias lies! J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3998–4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigdon, E.E.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. On Comparing Results from CB-SEM and PLS-SEM: Five Perspectives and Five Recommendations. Mark. ZFP 2017, 39, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Ahmed, R.R. ; Shamsi, AF Technology Confirmation is Associated to Improved Psychological Well-being: Evidence from an Experimental Design. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2021, No. 2, 177–196. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.G.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asim, J.; Ahmed, R.R.; Štreimikienė, D.; Rasheed, S.; Streimikis, J. Assessing design information quality in the construction industry: Evidence from building information modelling. Acta Montan. Slovaca 2021, 26, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. ; Rockwood, NJ Conditional process analysis: Concepts, computation, and advances in the modeling of the contingencies of mechanisms. Am. Behav. Sci. 2020, 64, 19–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štreimikienė, D.; Ahmed, R.R. The integration of corporate social responsibility and marketing concepts as a business strategy: Evidence from SEM-based multivariate and Toda-Yamamoto causality model. Oeconomia Copernic. 2021, 12, 125–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | ECG | ESM | HRE | HC | OP | RC | SC | TC |

| ECG1 | 0.852 | |||||||

| ECG2 | 0.723 | |||||||

| ECG3 | 0.821 | |||||||

| ESM1 | 0.831 | |||||||

| ESM2 | 0.714 | |||||||

| ESM3 | 0.892 | |||||||

| ESM4 | 0.763 | |||||||

| ESM5 | 0.906 | |||||||

| HRE1 | 0.815 | |||||||

| HRE2 | 0.864 | |||||||

| HRE3 | 0.773 | |||||||

| HRE4 | 0.680 | |||||||

| HRE5 | 0.755 | |||||||

| HC1 | 0.900 | |||||||

| HC2 | 0.760 | |||||||

| HC3 | 0.878 | |||||||

| HC4 | 0.755 | |||||||

| OP1 | 0.948 | |||||||

| OP2 | 0.844 | |||||||

| OP3 | 0.755 | |||||||

| OP4 | 0.944 | |||||||

| OP5 | 0.937 | |||||||

| OP6 | 0.606 | |||||||

| RC1 | 0.750 | |||||||

| RC2 | 0.728 | |||||||

| RC3 | 0.750 | |||||||

| RC4 | 0.725 | |||||||

| RC5 | 0.784 | |||||||

| RC6 | 0.818 | |||||||

| SC1 | 0.834 | |||||||

| SC2 | 0.782 | |||||||

| SC3 | 0.723 | |||||||

| TC1 | 0.780 | |||||||

| TC2 | 0.800 | |||||||

| TC3 | 0.854 | |||||||

| TC4 | 0.858 |

| Constructs | Cronbach's alpha | Composite reliability (rho_a) | Composite reliability (rho_c) | The average variance extracted (AVE) |

| Business Ethics | 0.943 | 0.949 | 0.950 | 0.598 |

| Ethics in Corporate Governance | 0.720 | 0.736 | 0.842 | 0.641 |

| Ethics in Sales & Marketing | 0.880 | 0.883 | 0.913 | 0.680 |

| HR Management Ethics | 0.875 | 0.883 | 0.909 | 0.666 |

| Human Capital | 0.841 | 0.843 | 0.895 | 0.682 |

| Organizational Performance | 0.917 | 0.940 | 0.938 | 0.720 |

| Relational Capital | 0.856 | 0.868 | 0.891 | 0.577 |

| Structural Capital | 0.679 | 0.687 | 0.824 | 0.610 |

| Technological Change | 0.849 | 0.883 | 0.894 | 0.679 |

| Constructs | BE | ECG | ESM | HRE | HC | OP | RC | SC | TC |

| Business Ethics | 1.000 | ||||||||

| Ethics in Corporate Governance | 0.779 | 1.000 | |||||||

| Ethics in Sales & Marketing | 0.806 | 0.790 | 1.000 | ||||||

| HR Management Ethics | 0.742 | 0.766 | 0.815 | 1.000 | |||||

| Human Capital | 0.802 | 0.838 | 0.757 | 0.783 | 1.000 | ||||

| Organizational Performance | 0.694 | 0.756 | 0.695 | 0.666 | 0.823 | 1.000 | |||

| Relational Capital | 0.665 | 0.717 | 0.693 | 0.614 | 0.812 | 0.817 | 1.000 | ||

| Structural Capital | 0.848 | 0.755 | 0.808 | 0.840 | 0.837 | 0.801 | 0.752 | 1.000 | |

| Technological Change | 0.839 | 0.825 | 0.802 | 0.840 | 0.809 | 0.764 | 0.781 | 0.785 | 1.000 |

| Constructs | BE | ECG | HRE | ESM | HC | OP | RC | SC | TC |

| Business Ethics | 0.773 | ||||||||

| Ethics in Corporate Governance | 0.772 | 0.801 | |||||||

| Ethics in HR | 0.637 | 0.719 | 0.816 | ||||||

| Ethics in Sales & Marketing | 0.750 | 0.787 | 0.792 | 0.825 | |||||

| Human Capital | 0.710 | 0.704 | 0.769 | 0.814 | 0.826 | ||||

| Organizational Performance | 0.646 | 0.616 | 0.598 | 0.624 | 0.765 | 0.848 | |||

| Rational Capital | 0.621 | 0.588 | 0.553 | 0.619 | 0.714 | 0.846 | 0.760 | ||

| Structural Capital | 0.668 | 0.738 | 0.749 | 0.773 | 0.673 | 0.665 | 0.795 | 0.781 | |

| Technological Change | 0.720 | 0.782 | 0.787 | 0.766 | 0.741 | 0.826 | 0.706 | 0.706 | 0.824 |

| Constructs | R-square | R-square adjusted |

| Business Ethics | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Human Capital | 0.828 | 0.828 |

| Organizational Performance | 0.918 | 0.917 |

| Rational Capital | 0.650 | 0.648 |

| Structural Capital | 0.793 | 0.792 |

| Constructs | BE | ECG | HRE | ESM | HC | OP | RC | SC | TC |

| Business Ethics | 4.828 | 0.055 | 0.054 | 0.151 | |||||

| Ethics in Corporate Governance | 22.283 | ||||||||

| HR Ethics | 73.131 | ||||||||

| Ethics in Sales & Marketing | 171.421 | ||||||||

| Human Capital | 0.358 | 0.194 | |||||||

| Organizational Performance | |||||||||

| Rational Capital | 0.633 | ||||||||

| Structural Capital | 0.432 | 0.757 | |||||||

| Technological Change | 0.978 |

| Direct Relationship | Standard deviation | T statistics | P values | |

| Business Ethics -> Organizational Performance | 0.163 | 0.066 | 2.484 | 0.013 |

| Ethics in Corporate Governance -> Business Ethics | 0.252 | 0.007 | 38.039 | 0.000 |

| Ethics in Sales & Marketing -> Business Ethics | 0.432 | 0.011 | 40.618 | 0.000 |

| HR Management Ethics -> Business Ethics | 0.368 | 0.009 | 39.666 | 0.000 |

| Human Capital -> Organizational Performance | 0.459 | 0.066 | 7.000 | 0.000 |

| Relational Capital -> Organizational Performance | 0.497 | 0.045 | 11.009 | 0.000 |

| Structural Capital -> Organizational Performance | -0.528 | 0.065 | 8.094 | 0.000 |

| Hypothesized Multiple Serial Mediation Relationship | Standard deviation | T statistics | P values | |

| ESM -> BE -> SC -> OP | -0.097 | 0.017 | 5.552 | 0.000 |

| HRE -> BE -> SC -> RC -> OP | 0.080 | 0.016 | 4.967 | 0.000 |

| ESM -> BE -> HC -> SC -> RC -> OP | 0.099 | 0.020 | 4.949 | 0.000 |

| ESM -> BE -> HC -> OP | 0.180 | 0.026 | 6.802 | 0.000 |

| BE -> HC -> SC -> RC -> OP | 0.229 | 0.046 | 5.005 | 0.000 |

| BE -> HC -> OP | 0.416 | 0.061 | 6.864 | 0.000 |

| ECG -> BE -> RC -> OP | -0.034 | 0.010 | 3.403 | 0.001 |

| HRE -> BE -> HC -> OP | 0.153 | 0.022 | 6.867 | 0.000 |

| HRE -> BE -> SC -> OP | -0.083 | 0.015 | 5.451 | 0.000 |

| ECG -> BE -> SC -> OP | -0.057 | 0.010 | 5.571 | 0.000 |

| ECG -> BE -> HC -> SC -> OP | -0.060 | 0.013 | 4.506 | 0.000 |

| HRE -> BE -> RC -> OP | -0.050 | 0.015 | 3.367 | 0.001 |

| ECG -> BE -> HC -> SC -> RC -> OP | 0.058 | 0.012 | 4.914 | 0.000 |

| BE -> HC -> SC -> OP | -0.238 | 0.052 | 4.597 | 0.000 |

| HRE -> BE -> HC -> SC -> RC -> OP | 0.084 | 0.017 | 5.030 | 0.000 |

| ESM -> BE -> OP | -0.070 | 0.028 | 2.485 | 0.013 |

| BE -> SC -> OP | -0.225 | 0.040 | 5.552 | 0.000 |

| ECG -> BE -> HC -> OP | 0.105 | 0.016 | 6.724 | 0.000 |

| ESM -> BE -> SC -> RC -> OP | 0.094 | 0.018 | 5.099 | 0.000 |

| BE -> RC -> OP | -0.137 | 0.040 | 3.391 | 0.001 |

| HRE -> BE -> OP | -0.060 | 0.024 | 2.481 | 0.013 |

| ESM -> BE -> RC -> OP | -0.059 | 0.018 | 3.371 | 0.001 |

| ECG -> BE -> SC -> RC -> OP | 0.054 | 0.011 | 5.131 | 0.000 |

| BE -> SC -> RC -> OP | 0.216 | 0.043 | 5.089 | 0.000 |

| HRE -> BE -> HC -> SC -> OP | -0.087 | 0.019 | 4.653 | 0.000 |

| ESM -> BE -> HC -> SC -> OP | -0.103 | 0.023 | 4.549 | 0.000 |

| ECG -> BE -> OP | -0.041 | 0.017 | 2.478 | 0.013 |

| Moderation of Technological change | Standard deviation | T statistics | P values | |

| Technological change x Business Ethics -> Organizational Performance | 0.036 | 0.013 | 2.754 | 0.006 |

| Factors | SSO | SSE | Q² (=1-SSE/SSO) |

| Business Ethics | 4511.000 | 2057.966 | 0.544 |

| Corporate Governance | 1041.000 | 734.908 | 0.294 |

| Ethics in Sales & Marketing | 1735.000 | 835.826 | 0.518 |

| HR Management Ethics | 1735.000 | 871.360 | 0.498 |

| Human Capital | 1388.000 | 741.411 | 0.466 |

| Organizational Performance | 2082.000 | 800.210 | 0.616 |

| Relational Capital | 2082.000 | 1232.689 | 0.408 |

| Structural Capital | 1041.000 | 790.969 | 0.240 |

| Technological Change | 1388.000 | 749.479 | 0.460 |

| Fitness Indicators | Saturated model | Estimated model |

| SRMR | 0.054 | 0.049 |

| d_ULS | 28.963 | 27.967 |

| d_G | n/a | n/a |

| Chi-square | Infinite | Infinite |

| NFI | 0.912 | 0.929 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).