1. Introduction

Adolescence is a complex transitional phase within the life cycle characterized by physical, psychological, and emotional changes [

1]. During this critical period, the psychological dynamics underlying identity construction develop as a function of a constantly evolving context. Nowadays adolescents experience a complex digitalized environment, requiring rapid adaptation to the needs characterizing the digital revolution. As a consequence, social networks strongly affect the development and construction of self-identity: adolescents can create their personal profile, share their identity with their peers, and build networks for new or current relationships [

2].

On the other hand, such a digital context experienced by adolescents during their development brings about certain critical points. Excessive use of social networks can interfere with adolescents' ability to manage their own emotions and properly interact with peers’ emotions [

3], a psychological construct better known as emotional intelligence (EI). EI is defined as the ability to recognize and understand one's own emotions and the emotions of others, and to use this awareness to effectively manage their own behavior and relationships [

4]. Indeed, several evidence demonstrated the negative impact of social networks on the EI of adolescents. For instance, continued exposure to negative content, such as cyberbullying, can lead to a decrease in empathy and emotional sensitivity in adolescents [

5]. Furthermore, the extensive use of social networks can also negatively influence the perception and expression of adolescents’ emotions, who feel less secure in their ability to effectively communicate their emotions and interpret the emotions of others [

3]. An extensive use of technology and social networks leads to cognitive transformations in adolescents, including alteration of perception and expression of emotions, and a dysfunctional influence on relational styles [

6], probably related to the lack of physicality in the socialization processes [

7]. In this perspective, Riva [

6] introduces the concept of emotional illiteracy, describing this phenomenon as a lack of awareness and control over the emotions of others, leading to an inability to functionally interact with the emotions and related behaviors of their peers.

Furthermore, another critical aspect concerns the negative effects produced by social comparison in adolescents, which derive from the immediacy of access to digital content that represents potential aesthetic standards. A recent study conducted in Australia documented the dissatisfaction of women with their bodies when exposed to images of attractive celebrities on Instagram [

8], highlighting the negative effects that social networks often have on self-esteem. The digital era marks new challenges for adolescents during their development, implying a strong pressure for social comparison with the high and often unachievable standards that the virtual world brings during physical changes and identity construction.

Hence, it is doubtless of great importance to spot the social networks most utilized by adolescents to communicate, express their emotions, and share their identity. Consistent with this theoretical framework, the findings of Waterloo et al. [

9] revealed a higher incidence of WhatsApp use (90.2%), followed by Facebook (88.3%), Instagram (54.5%) and Twitter (34.6%). Interestingly, the authors concluded that the expression of positive emotions on social networks is more common than the expression of negative emotions, characterizing WhatsApp as the social network most used for this purpose.

The Global Digital report [

10] highlighted the highest usage of Facebook (2,121 billion) by the world population, followed by Instagram (895 million) and Twitter (251 million). Specifically, considering the apps investigated in this study, it is evident that Facebook is mostly used by the male population (57%), and Instagram is used equally (50%).

In line with this theoretical and operational framework, the current study aims to explore the relationship between EI and the use of social networks (WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram) in a sample of adolescents aged between 15 and 19. Previous research has suggested that individuals with high EI may be more successful in social interactions on-line [

11], but the relationship between EI and social network use has not been fully documented. This study aims to fill this gap in the literature by investigating the relationship between EI and various aspects of social network use, including frequency, motives of use, and the relationship between these variables and the characteristics of the sample (gender, age, sociodemographic variables of families).

1.1. Research Questions

Recent Italian studies [

12,

13], identified Whatsapp as the most used, followed by Instagram and Facebook.

Previous findings revealed that the most frequent reasons for using social networks are related to boredom, followed by the opportunity to communicate with peers, send messages, stay in touch with them, and look at photos of others [

12,

13].

We expected to find similar results on the average time spent on each social network and on the reasons for using them.

- 2.

Is there a difference in the typology of social usage time between males and females and is it related to the sociodemographic variables of the families?

Taking into account previous findings of Riva [

6] and Tremolada et al. [

13], girls are expected to spend more time on Instagram compared to their male counterpart.

- 3.

Is there a difference in the factors and scales of emotional intelligence according to gender?

Bar-on [

14] found that there are no significant differences between men and women in the total emotional intelligence score. However, based on the North American sample, females would have better interpersonal abilities compared to males, showing more empathy, awareness of their own emotions, and sense of social responsibility. On the contrary, males seem to have better adaptive and intrapersonal abilities [

14]. Therefore, it is conceivable that there is a gender difference in these EI subscales also in our sample.

- 4.

Is there an association between the hours spent on social networks and the scales of emotional intelligence?

A relationship between EI and the use of social networks is expected, as already suggested in the literature [

15] and, specifically, a relationship between the time spent on the three social networks and the EI scales.

- 5.

Is the social desirability of adolescents associated with their emotional intelligence?

The construct of social desirability is the response bias that affects interviewees and jeopardizes the truthfulness of the results [

16].

Evidence related to body image and internalization processes [

17] suggested that social comparison mediated by new types of communication could play an important role in emotional aspects such as self-esteem, personal satisfaction in adolescents, and mood that is easily influenced at this age. We will evaluate whether boys and girls respond to items on the various scales honestly or are guided by social desirability.

4. Discussion

The current study was conducted with the aim to understand the needs of today's adolescents and to suggest potential psychosocial and educational-school interventions according to their social networks use and preferences.

Considering the current digitalized reality that adolescents experience daily, it is evident that technology and social networks play a relevant and important role. Understanding the psychological consequences, advantages, motivations, and effects that the technological world offers and reserves for these generations is very compelling. The findings revealed by the current study offer new insights into the psychosocial development of adolescents, providing useful information to deeply understand the current reality experienced by adolescents.

In particular, we investigated the amount of time spent on Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp. Previous evidence highlighted a relevant growing trend in the use of social networks in adolescents, particularly among those who have access to mobile devices [

9]. Recent findings support Waterloo et al., [

9] findings, shedding light on the amount of time spent using social networks in Italy, where the daily average usage of social networks was estimated at one hour and 51 minutes a day [

9].

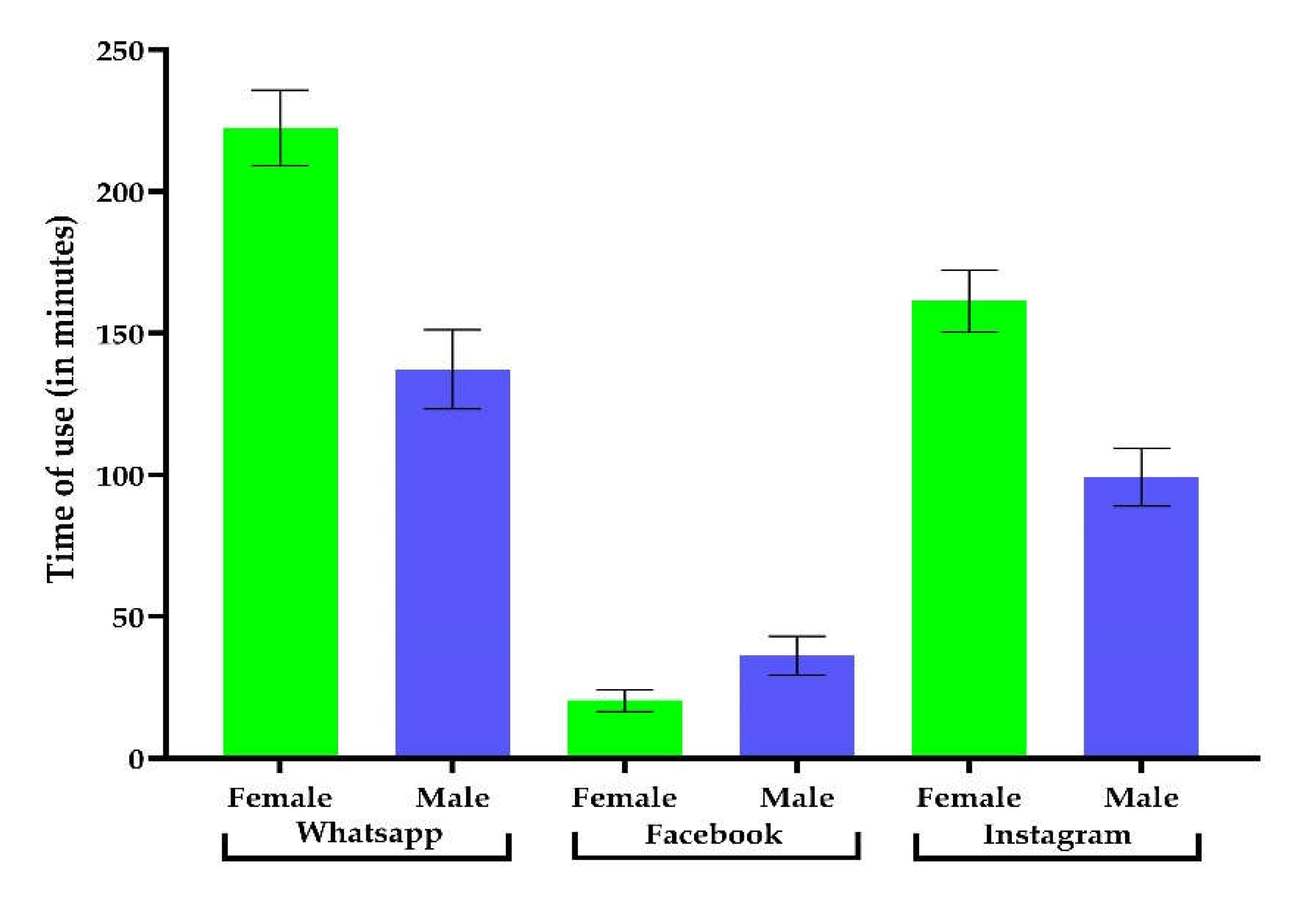

In the current study, participants declared to spend an average of more than 3 hours a day on WhatsApp and more than 2 hours a day on Instagram. Facebook usage resulted in 26.72 minutes per day. Data related to time spent on WhatsApp and Instagram were higher than those reported by the Global Digital report [

10], which also showed a higher use of Facebook compared to Instagram. Instead, our results, in accordance with more recent findings [

13], demonstrated that WhatsApp and Instagram are more used, compared to Facebook.

A possible explanation could refer to the differences of the participants in the studies: the study conducted by Waterloo et al. [

9] included subjects aged 15 to 25 years, considering a wider age group. The same was applied to the report by Global Digital [

10], which analyzed the entire Italian population and did not specify the percentages.

Furthermore, the main reasons for the use of social networks were investigated. The results revealed that the most frequent reason reported is linked to boredom followed by the social sphere. Indeed, participants declared that they use social networks to communicate with friends, stay in touch with them, manage to communicate with people who are difficult to reach, send messages to friends, look at other people's photos, as well as checking WhatsApp, Facebook, or their own Instagram profile. These findings confirm previous studies (i.e., [

13]), which highlight the strong impact of social networks on the construction of the adolescents’ identity. The concept of identity is deeply conditioned by the historical context and reference figures, including the peer group [

21]. Social comparison influences the construction of personal identity [

22]: in the adolescent phase, individuals begin to use the stream of information received from various sources, mainly social networks [

23], to build a sense of self and a personal identity [

21].

We also investigated whether the impact of social media changes as a function of gender. Consistent with our hypothesis, our results revealed a gender difference in the amount of time spent on social networks. The results showed that females use Whatsapp and Instagram almost an hour a day more than males’ peers, supporting the general trend documented by Tremolada and colleagues [

13] and Riva [

6]. However, our results showed that Facebook time was longer for boys compared to their female counterpart, also confirming the data from the 2019 Global Digital report (both data were collected in the same year). In addition, our results supported the idea that girls typically used social networks more when bored compared to their male counterparts, who instead preferred to use social media to send messages to friends, for fun and to find company.

Another important aspect of our study considered the relationship between the use of digital media by adolescents and the sociodemographic characteristics of their parents, investigating whether the number of hours spent by mothers and fathers at work and their years of education could correlate with the use of social media. We investigate such a potential relationship, focusing on parental sociodemographic characteristics, based on the idea that proactive participation of parents in the education of smartphone and social media use strongly impacts their identity construction, as it has been shown that social media use is problematic when it exceeds 1 or 2 hours a day [

24]. Our results suggested that the use of WhatsApp and Instagram was associated with the level of education of the father. A higher level of father’s education was associated with lower social media use and vice versa. However, our results did not provide any evidence on the influence of the sociodemographic characteristics of the mother and the hours of work of the fathers.

We aim to understand the relationship between emotional intelligence (EI), the use of social media by adolescents, and their sociodemographic and family characteristics. The concept of emotional intelligence, as explained by Bar-On [

14], is an important factor for individuals, as it determines their ability to succeed in life and directly influences their psychological well-being. Thus, understanding how social networks impact the level of emotional intelligence assumes a role of paramount importance in a digitalized reality dominated by an interconnected world and continuous technological advancements.

Hence, we first investigated the participants' average level of emotional intelligence. Analyzing EI factors, adolescents in the current study have been shown to report higher scores in the intrapersonal dimension, reflecting greater abilities related to the intimate and personal sphere. Similarly, participants reported high scores on the adaptability dimension, corresponding to the subjects' ability to adapt flexiblely to reality and new situations [

14]. Regarding gender differences, our findings underline that male adolescents reported slightly higher scores on both general scales, with respect to their female counterparts. To shed more light on EI gender differences, we analysed, separately, each subscale. Interestingly, our results showed that girls are more empathetic compared to male peers. On the contrary, these findings suggested that girls are more independent and capable of adapting flexibly to difficult situations or coping with psychological or environmental issues. Overall, our results suggested that females would experience a greater sense of social responsibility with respect to males. These findings seem to be consistent with previous evidence [

14], highlighting no significant differences between men and women when the total score of emotional intelligence is considered, even if gender differences emerge when considering factor scores and specific EI subscales. Furthermore, according to Bar-On [

14], our findings suggested that females reported higher scores in the interpersonal sphere, demonstrating greater empathy, social responsibility, and awareness of their emotions, while males reported a higher degree of adaptive and intrapersonal competencies.

Finally, we aimed to clarify the possible relationship between EI and social networks. Our results suggest that social media use is strongly associated with the emotional sphere of adolescents. Interestingly, our findings revealed that the time spent by adolescents (in particular, males) using social media in the order of WhatsApp, Facebook, and Instagram, is associated with the functional coping and stress management, and vice versa. In detail, our results highlighted that the time spent on the WhatsApp instant messaging application is positively associated with the ability of adolescents to be assertive and therefore capable of defending and expressing their thoughts, feelings, and beliefs, a competence that falls within the intrapersonal dimension proposed by Bar-On [

14]. At the same time, our results suggest that WhatsApp could be negatively associated with interpersonal relationships and self-awareness. These results should not be surprising, considering the basic functionality of the instant messaging application [

6].

Furthermore, our findings indicated that the time spent using Facebook is positively associated with EI, including aspects of self-realization and stress management. Similarly, time spent on Instagram is significantly positively associated with stress reduction abilities and increased optimism. These findings add new knowledge to previous findings [

9], demonstrating that expression and communication of positive emotions (e.g., joy, pride) typically occur through social media platforms such as Instagram, resulting in increased optimism derived from exposure to news and content filled with uplifting and mood-enhancing emotions.

It is note to worth that when adolescents self-assess their abilities in the domains of emotions, interpersonal relationships, and other domains of self-identity related to the social sphere, they are likely to fall into a social desirability bias, acting in a socially acceptable manner to avoid exclusion or any kind of judgment. [

18]. Indeed, such bias often occurs when adolescents respond directly to questions and statements concerning their self-identity, as is the case of the EI questionnaire administered to the sample of the current study. This phenomenon is also documented in online interviews [

25,

26]. To limit the effect of social desirability bias in assessing their emotional abilities, MC-SDS [

18] was administered to participants, in order to assess the level of social desirability experienced and thus evaluating the degree of influence on self-evaluation. Our findings confirm the impact of the social desirability bias in adolescents documented in previous evidence (see also [

17]), highlighting a relationship with the use of social media and problems of body image, and therefore subsequent poor mental health in adolescence. Furthermore, these results show how social desirability influences male adolescents when they reported self-evaluation with respect to adaptability, stress management, and general mood. In detail, regarding the adaptive dimension of EI, it could be inferred that male adolescents are more affected by social desirability compared to female peers, considering their ability to adapt to critical situations and their problem solving skills. Furthermore, our results suggested that social desirability is negatively associated with some intrapersonal aspects (e.g., self-regard, flexibility, impulse control, happiness, and optimism), reflecting the stronger influence exerted by social comparison and the negative feelings generated by content on social media.

Moreover, our objective was to identify the main reasons for using social networks in adolescents and how such reasons affect their EI levels, administering a survey capable of exploring EI aspects. Interestingly, the main reasons that drive adolescents to use social media concerns the possibility of looking at other people's photos, both in adolescents with an average and lower EI, with respect to the normative sample [

14]. This aspect could potentially negatively interfere with the functional development of EI in adolescents.

Overall, the current study shed some new light on the relationship between the impacts of social media on EI in adolescents. The findings outlined the relevant importance of sociotechnological changes in EI and the construction of identity in adolescents. Importantly, the current research was conducted during the period prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (2019); therefore, our results could provide an interesting point of comparison of psychological and emotional changes in adolescents deriving from the use of social networks during or after the COVID-19 pandemic period. The current digitalized world evolves rapidly, affecting the cognitive and emotional spheres, requiring adolescents to adapt their preferences and habits flexibly. For instance, differently from our results, it has been demonstrated that Facebook was the most used social media in the period ranging between 2020 and 2022. Furthermore, differently than in previous years, males prefer to use [

27,

28,

29], highlighting a rapid transition of the needs and habits of adolescents in this digitalized society during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

A noteworthy limitation of the current study is represented by the levels of social desirability assessed in adolescents in our sample. Since all the measures administered are self-reported, it could be possible that social bias could have masked some relevant information. Furthermore, the extensive administration time of the questionnaires could represent a further limitation, since it could have produced a state of boredom in the participants, conditioning their responses. Future studies could overcome this limit by validating more specific and faster tools to investigate EI and social media usage. Validating new potential measurement tools would also be convenient in limiting the constraints generated by the lack of an Italian normative sample, as in the case of the EQ-i Emotional Quotient Inventory [

14].

As a future perspective, the clarification of the relationship among technology, social networks, and the emotional aspects could provide useful and operational tools to support the functional development of adolescents' emotional intelligence to educators and parents, encouraging an education grounded on conscious use of social networks. This perspective includes support for time management and limits of use of social networks, as well as education about the risks and drawbacks associated with the use of social networks. Additionally, emotional education should be integrated into the development of teenagers to help them develop the ability to recognize and manage their emotions and those of others.