Submitted:

24 April 2023

Posted:

25 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

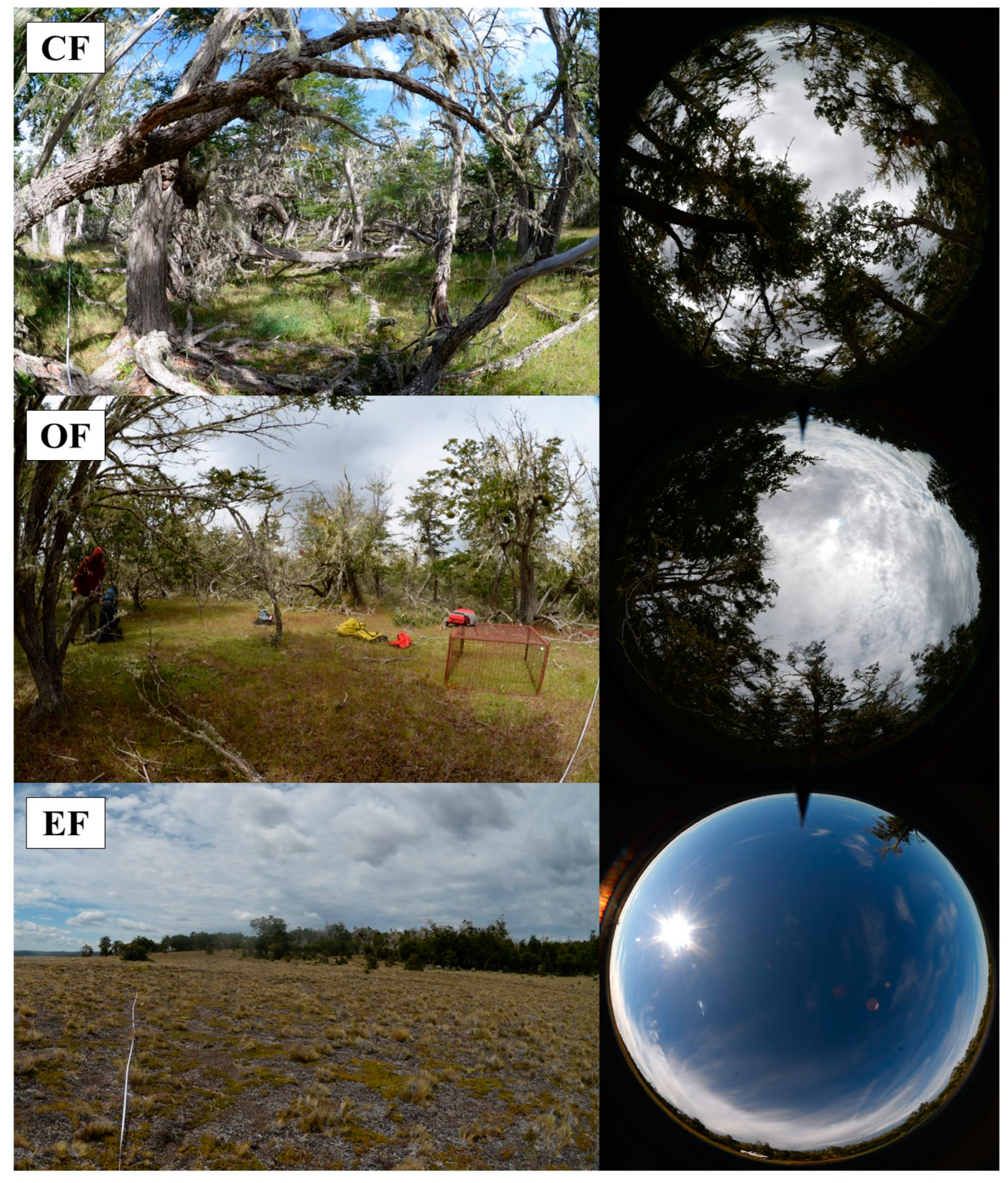

2.1. Study area characterization

2.2. Radial growth of the regeneration and microclimate characterization

2.3. Statistical analyses

3. Results

3.1. Changes among the forest attributes of the studied environments

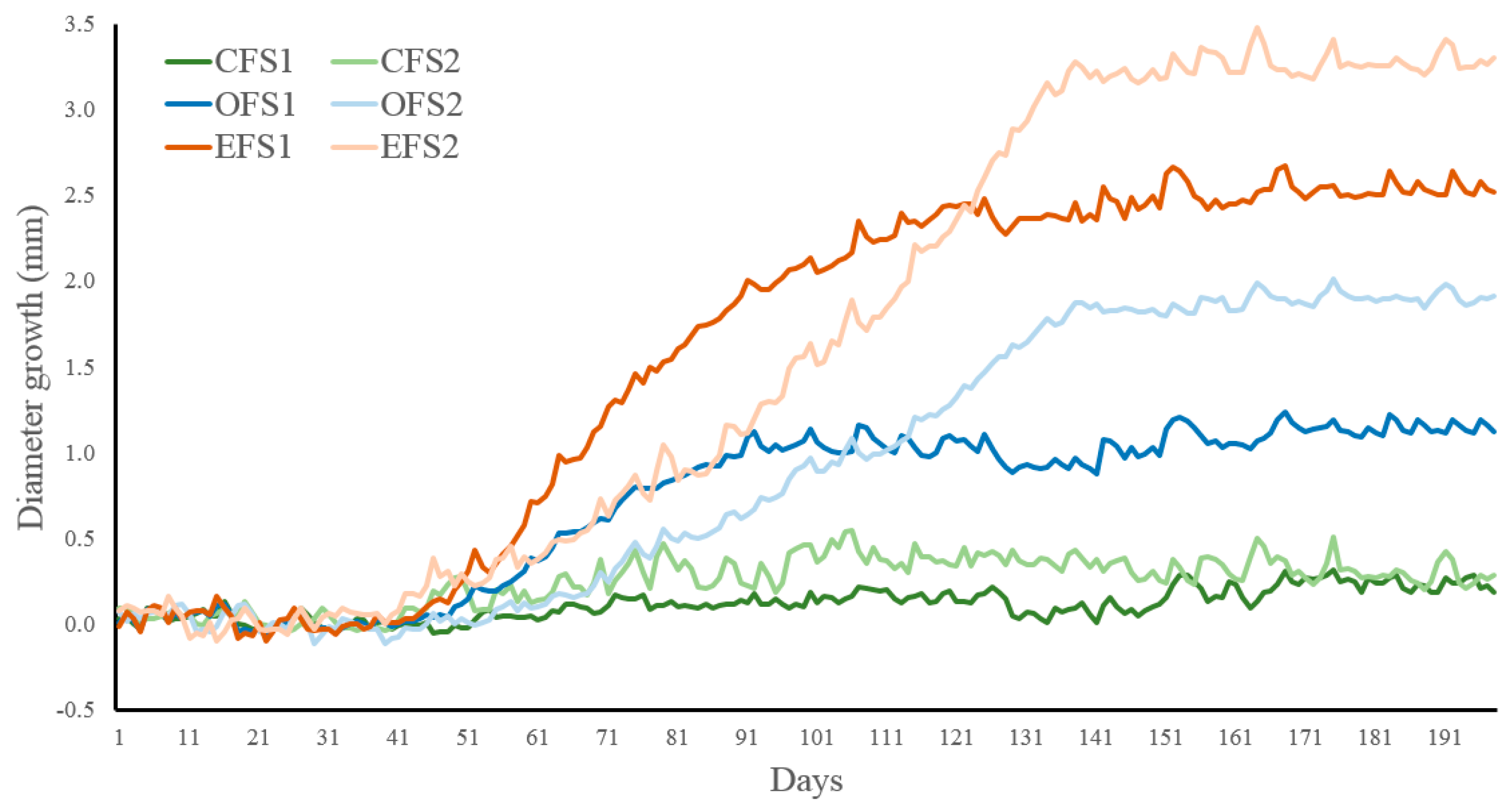

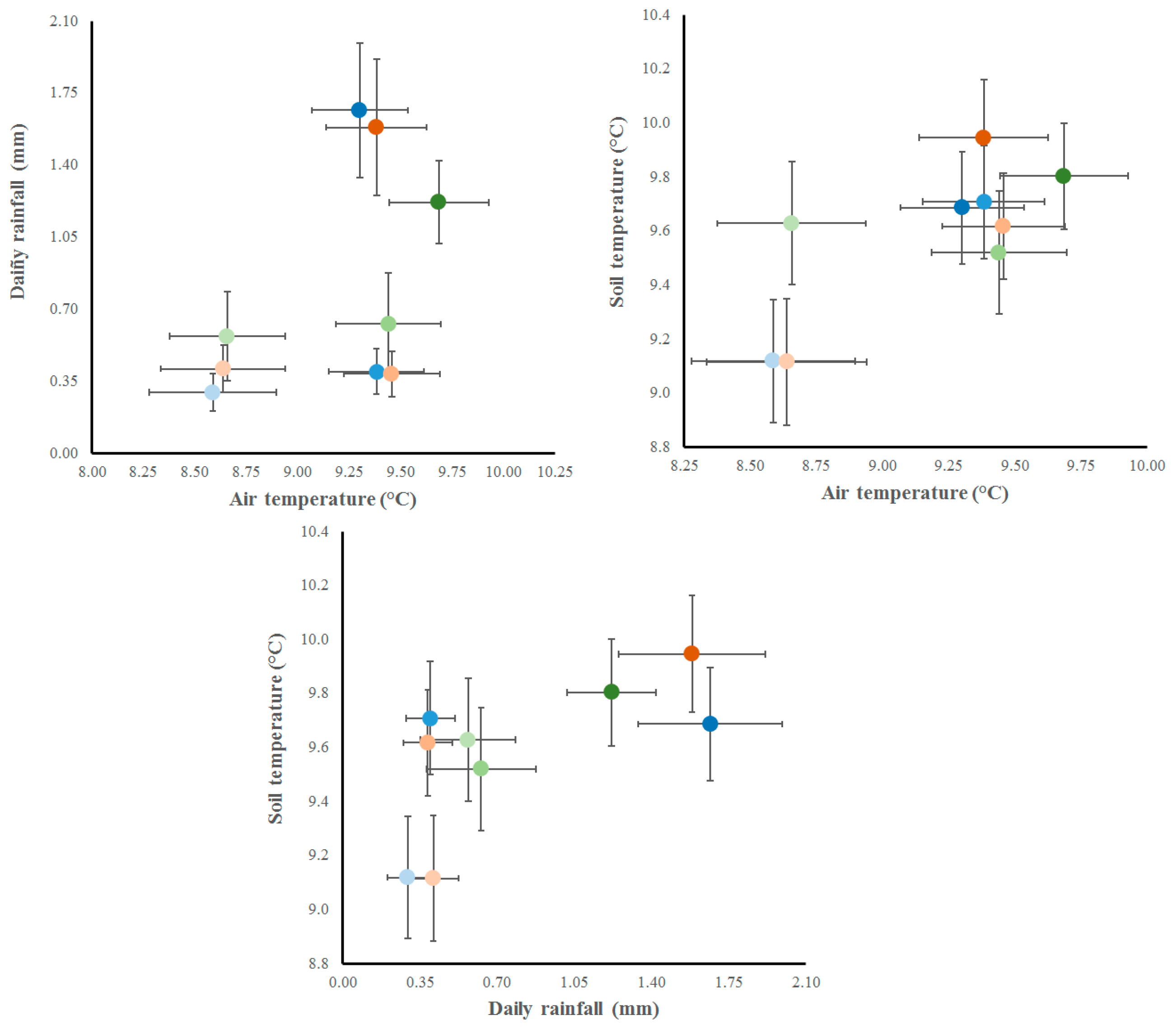

3.2. Daily growth increments of regeneration growing at different forest environments

4. Discussion

4.1. The influence of overstory cover and management over forest attributes

4.2. Regeneration growing at different forest environments

4.3. Management implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Season | Month | RAIN | AT | ST |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018-2019 | OCT | 32.8 | 5.2 | 4.6 |

| NOV | 16.4 | 8.5 | 8.2 | |

| DEC | 27.6 | 10.7 | 10.6 | |

| JAN | 20.4 | 9.9 | 10.8 | |

| FEB | 20.2 | 9.4 | 10.7 | |

| MAR | 33.8 | 8.5 | 9.1 | |

| APR | 40.4 | 4.8 | 5.8 | |

| 2019-2020 | OCT | 12.6 | 5.5 | 5.3 |

| NOV | 31.0 | 7.7 | 7.9 | |

| DEC | 45.6 | 10.3 | 10.5 | |

| JAN | 52.0 | 10.8 | 11.4 | |

| FEB | 14.0 | 10.8 | 11.7 | |

| MAR | 20.8 | 8.4 | 9.5 | |

| APR | 3.1 | 4.6 | 5.5 |

| Rainfall | 0.0 | 0.0-0.2 | 0.2-1.0 | >1.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCT | 64.5% | 16.1% | 9.7% | 9.7% |

| NOV | 60.0% | 10.0% | 11.7% | 18.3% |

| DEC | 66.1% | 9.7% | 12.9% | 11.3% |

| JAN | 50.0% | 16.1% | 14.5% | 19.4% |

| FEB | 51.3% | 25.6% | 12.8% | 10.3% |

| MAR | 51.6% | 12.9% | 12.9% | 22.6% |

| APR | 33.3% | 33.3% | 13.3% | 20.0% |

| SEASON | 56.1% | 16.2% | 12.4% | 15.3% |

| Air temperature | <8.0 | 8.0-10.0 | >10.0 | |

| OCT | 88.7% | 4.8% | 6.5% | |

| NOV | 46.7% | 33.3% | 20.0% | |

| DEC | 12.9% | 19.4% | 67.7% | |

| JAN | 12.9% | 32.3% | 54.8% | |

| FEB | 33.3% | 17.9% | 48.7% | |

| MAR | 41.9% | 25.8% | 32.3% | |

| APR | 90.0% | 10.0% | 0.0% | |

| SEASON | 43.9% | 21.1% | 35.0% | |

| Soil temperature | <8.0 | >8.0 | ||

| OCT | 100.0% | 0.0% | ||

| NOV | 40.0% | 60.0% | ||

| DEC | 0.0% | 100.0% | ||

| JAN | 0.0% | 100.0% | ||

| FEB | 0.0% | 100.0% | ||

| MAR | 6.5% | 93.5% | ||

| APR | 86.7% | 13.3% | ||

| SEASON | 32.9% | 67.1% |

References

- Hakkenberg, C.R.; Song, C.; Peet, R.K.; White, P.S. Forest structure as a predictor of tree species diversity in the North Carolina Piedmont. J. Veg. Sci. 2016, 27, 1151–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peri, P.L.; Hansen, N.E.; Bahamonde, H.A.; Lencinas, M.V.; von Müller, A.R.; Ormaechea, S.; Gargaglione, V.; Soler, R.M.; Tejera, L.; Lloyd, C.E.; Martínez Pastur, G. Silvopastoral systems under native forest in Patagonia, Argentina. In Silvopastoral systems in southern South America; Peri, P.L., Dube, F., Varella, A., Eds.; Springer, Series; Advances in Agroforestry 11: Bern, Switzerland, 2016; chapter 6, pp 117-168. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Pastur, G.; Rosas, Y.M.; Chaves, J.; Cellini, J.M.; Barrera, M.D.; Favoretti, S.; Lencinas, M.V.; Peri, P.L. Changes in forest structure values along the natural cycle and different management strategies in Nothofagus antarctica forests. For. Ecol. Manage. 2021, 486, e118973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Pastur, G.; Soler, R.M.; Lencinas, M.V.; Cellini, J.M.; Peri, P.L. Long-term monitoring of thinning for silvopastoral purposes in Nothofagus antarctica forests of Tierra del Fuego, Argentina. For. Syst. 2018, 27, e–01S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamonde, H.A.; Peri, P.L.; Álvarez, R.; Barneix, A. Producción y calidad de gramíneas en un gradiente de calidades de sitio y coberturas en bosques de Nothofagus antarctica (G. Forster) Oerst. en Patagonia. Ecología Austral 2012, 22, 62–73. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, M.F.; Wentzel, H.; Schmidt, A.; Balocchi, O. Plant community shifts along tree canopy cover gradients in grazed Patagonian Nothofagus antarctica forests and grasslands. Agrofor. Syst. 2020, 94, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormaechea, S.; Peri, P.L. Landscape heterogeneity influences on sheep habits under extensive grazing management in Southern Patagonia. Liv. Res. Rural Dev. 2015, 27, e105. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Pastur, G.; Cellini, J.M.; Chaves, J.; Rodriguez-Souilla, J.; Benítez, J.; Rosas, Y.M.; Soler, R.M.; Lencinas, M.V.; Peri, P.L. Changes in forest structure modify understory and livestock occurrence along the natural cycle and different management strategies in Nothofagus antarctica forests. Agrofor. Syst. 2022, 96, 1039–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Pastur, G.; Rosas, Y.M.; Cellini, J.M.; Barrera, M.D.; Toro Manríquez, M.; Huertas Herrera, A.; Favoretti, S.; Lencinas, M.V.; Peri, P.L. Conservation values of understory vascular plants in even- and uneven-aged Nothofagus antarctica forests. Biodiv. Conserv. 2020, 29, 3783–3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peri, P.L.; López, D.; Rusch, V.; Rusch, G.; Rosas, Y.M.; Martínez Pastur, G. State and transition model approach in native forests of Southern Patagonia (Argentina): Linking ecosystemic services, thresholds and resilience. Int. J. Biodiv. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manage. 2017, 13, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, R.M.; Martínez Pastur, G.; Peri, P.L.; Lencinas, M.V.; Pulido, F. Are silvopastoral systems compatible with forest regeneration? An integrative approach in southern Patagonia. Agrofor. Syst. 2013, 87, 1213–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamonde, H.A.; Lencinas, M.V.; Martínez Pastur, G.; Monelos, L.H.; Soler, R.M.; Peri, P.L. Ten years of seed production and establishment of regeneration measurements in Nothofagus antarctica forests under different crown cover and quality sites, in Southern Patagonia. Agrofor. Syst. 2018, 92, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Pastur, G.; Soler, R.M.; Ivancich, H.; Lencinas, M.V.; Bahamonde, H.A.; Peri, P.L. Effectiveness of fencing and hunting to control Lama guanicoe browsing damage: Implications for Nothofagus pumilio regeneration in harvested forests. J. Environ. Manage. 2016, 168, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Pastur, G.; Peri, P.L.; Cellini, J.M.; Lencinas, M.V.; Barrera, M.D.; Ivancich, H. Canopy structure analysis for estimating forest regeneration dynamics and growth in Nothofagus pumilio forests. Ann. For. Sci. 2011, 68, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.D.; Cellini, J.M.; Lencinas, M.V.; Barrera, M.D.; Soler, R.M.; Díaz-Delgado, R.; Martínez Pastur, G. Seed production and recruitment in primary and harvested Nothofagus pumilio forests: Influence of regional climate and years after cuttings. For. Syst. 2015, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalba, R.; Luckman, B.; Boninsegna, J.; D'arrigo, R.; Lara, A.; Villanueva-Diaz, J.; Masiokas, M.; Argollo, J.; Soliz, C.; Lequesne, C.; Stahle, D.; Roig, F.A.; Aravena, J.; Wiles, G.; Hartsough, P.; Wilson, R.; Watson, E.; Cook, E.; Cerano-Paredes, J.; Therrell, M.; Cleaveland, M.; Morales, M.; Moya, J.; Pacajes, J.; Massaccesi, G.; Biondi, F.; Urrutia, R.; Martínez Pastur, G. Dendroclimatology from regional to continental scales: Understanding regional processes to reconstruct large-scale climatic variations across the Western Americas. In Dendroclimatology: Progress and prospects; Hughes, M., Swetnam, T., Díaz, H., Eds.; Springer, Developments in Paleoenvironmental Research 11: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2010; chapter 7, pp 175-227. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Liang, E.; Liu, R.; Babst, F.; Camarero, J.; Fu, Y.; Piao, S.; Rossi, S.; Shen, M.; Wang, T.; Peñuelas, J. An earlier start of the thermal growing season enhances tree growth in cold humid areas but not in dry areas. Nature Ecol. Evol. 2022, 6, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Sancho, E.; Treydte, K.; Lehmann, M.; Rigling, A.; Fonti, P. Drought impacts on tree carbon sequestration and water use-evidence from intra-annual tree-ring characteristics. New Phytol. 2022, 236, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez Pastur, G.; Soler, R.M.; Pulido, F.; Lencinas, M.V. Variable retention harvesting influences biotic and abiotic drivers of regeneration in Nothofagus pumilio southern Patagonian forests. For. Ecol. Manage. 2013, 289, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Frenne, P.; Lenoir, J.; Luoto, M.; Scheffers, B.; Zellweger, F.; Aalto, J.; Ashcroft, M.; Christiansen, D.; Decocq, G.; De Pauw, K.; Govaert, S.; Greiser, C.; Gril, E.; Hampe, A.; Jucker, T.; Klinges, D.; Koelemeijer, I.; Lembrechts, J.; Marrec, R.; Meeussen, C.; Ogée, J.; Tyystjärvi, V.; Vangansbeke, P.; Hylander, K. Forest microclimates and climate change, Importance; drivers and future research agenda. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2021, 27, 2279–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Pastur, G.; Lencinas, M.V.; Cellini, J.M.; Mundo, I. Diameter growth: Can live trees decrease? Forestry 2007, 80, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniderhan, A.E.; Mamet, S.D.; Baltzer, J.L. Non-uniform growth dynamics of a dominant boreal tree species (Picea mariana) in the face of rapid climate change. Can. J. For. Res. 2021, 51, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matskovsky, V.; Roig, F.A.; Martínez Pastur, G. Removal of non-climatically induced seven-year cycle from Nothofagus pumilio tree-ring width chronologies from Tierra del Fuego; Argentina for their use in climate reconstructions. Dendrochronologia 2019, 57, e125610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matskovsky, V.; Roig, F.A.; Fuentes, M.; Korneva, I.; Araneo, D.; Linderholm, H.; Aravena, J.C. Summer temperature changes in Tierra del Fuego since AD 1765: Atmospheric drivers and tree-ring reconstruction from the southernmost forests of the world. Clim. Dyn. 2023, 60, 1635–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, P.; Srur, A.; Bianchi, L. Climate-growth relationships of deciduous and evergreen Nothofagus species in Southern Patagonia, Argentina. Dendrochronologia 2019, 58, e125646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Cooper, D.; Li, Z.; Song, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, B.; Han, S.; Wang, X. Differences in tree and shrub growth responses to climate change in a boreal forest in China. Dendrochronologia 2020, 63, e125744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Shishov, V.V.; Tychkov, I.; Zhou, P.; Jiang, S.; Ilyin, V.A.; Ding, X.; Huang, J.G. Response of model-based cambium phenology and climatic factors to tree growth in the Altai Mountains, Central Asia. Ecol. Ind. 2022, 143, e109393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peri, P.L.; Lencinas, M.V.; Bousson, J.; Lasagno, R.; Soler, R.M.; Bahamonde, H.A.; Martínez Pastur, G. Biodiversity and ecological long-term plots in Southern Patagonia to support sustainable land management: The case of PEBANPA network. J. Nat. Conserv. 2016, 34, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitterlich, W. The relascope idea: Relative measurements in forestry; CAB: London, England, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Ivancich, H. Relaciones entre la estructura forestal y el crecimiento del bosque de Nothofagus antarctica en gradientes de edad y calidad de sitio. Dissertation of doctoral thesis, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata, Argentina, 2013.

- Bray, R.H.; Kurtz, L.T. Determination of total, organic, and available forms of phosphorus in soils. Soil Sci. 1945, 59, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamonde, H.A.; Gargaglione, V.; Peri, P.L. Sheep faeces decomposition and nutrient release across an environmental gradient in Southern Patagonia. Ecología Austral 2017, 27, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peri, P.L.; Rosas, Y.M.; López, D.; Lencinas, M.V.; Cavallero, L.; Martínez Pastur, G. Management strategies for silvopastoral system in native forests. Ecología Austral 2022, 32, 749–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, R.M.; Martínez Pastur, G.; Lencinas, M.V.; Borrelli, L. Differential forage use between native and domestic herbivores in southern Patagonian Nothofagus forests. Agrofor. Syst. 2012, 85, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinteros, P.; Hansen, N.; Kutschker, A. Composición y diversidad del sotobosque de ñire (Nothofagus antarctica) en función de la estructura del bosque. Ecología Austral 2010, 20, 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Quinteros, P.; López Bernal, P.M.; Gobbi, M.E.; Bava, J. Distance to flood meadows as a predictor of use of Nothofagus pumilio forest by livestock and resulting impact, in Patagonia, Argentina. Agrofor. Syst. 2012, 84, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, M.V.; Garibaldi, L.; Kitzberger, T.; Chaneton, E. Impact of introduced herbivores on understory vegetation along a regional moisture gradient in Patagonian beech forests. For. Ecol. Manage. 2016, 366, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollmann, W.; Veblen, T.T. Nothofagus regeneration dynamics in south-central Chile, A test of a general model. Ecol. Monograp. 2004, 74, 615–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Galen, L.; Lord, J.; Orlovich, D.; Larcombe, M. Restoration of southern hemisphere beech (Nothofagaceae) forests: A meta-analysis. Rest. Ecol. 2020, 29, e13333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Pastur, G.; Cellini, J.M.; Lencinas, M.V.; Barrera, M.D.; Peri, P.L. Environmental variables influencing regeneration of Nothofagus pumilio in a system with combined aggregated and dispersed retention. For. Ecol. Manage. 2011, 261, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, D.; Donoso, P.; Zamorano Elgueta, C.; Ríos, A.; Promis, A. Precipitation declines influence the understory patterns in Nothofagus pumilio old-growth forests in northwestern Patagonia. For. Ecol. Manage. 2021, 491, e119169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro-Manríquez, M.; Soler, R.M.; Lencinas, M.V.; Promis, A. Canopy composition and site are indicative of mineral soil conditions in Patagonian mixed Nothofagus forests. Ann. For. Sci. 2019, 76, e117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, J.M.; Navarro Cerrillo, R.; Guzman Alvarez, J.R. Regeneration of Nothofagus pumilio (Poepp. et Endl.) Krasser forests after five years of seed tree cutting. J. Environ. Manage. 2006, 78, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T.; Jordan, G.; Steel, A.; Fountain-Jones, N.; Wardlaw, T.; Baker, S. Microclimate through space and time, Microclimatic variation at the edge of regeneration forests over daily, yearly and decadal time scales. For. Ecol. Manage. 2014, 334, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, M.L.; Kitzberger, T. Recruitment patterns following a severe drought: Long-term compositional shifts in Patagonian forests. Can. J. For. Res. 2008, 38, 3002–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, S.A.; Gyenge, J.E.; Fernández, M.E.; Schlichter, T. Seedling drought stress susceptibility in two deciduous Nothofagus species of NW Patagonia. Trees 2010, 24, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoroso, M.; Suarez, M.L.; Daniels, L. Nothofagus dombeyi regeneration in declining Austrocedrus chilensis forests: Effects of overstory mortality and climatic events. Dendrochronologia 2012, 30, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just, M.; Frank, S.D. Evaluation of an easy-to-install; low-cost dendrometer band for citizen-science tree research. J. For. 2019, 117, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivar, J.; Rais, A.; Pretzsch, H.; Bravo, F. The impact of climate and adaptive forest management on the intra-annual growth of Pinus halepensis based on long-term dendrometer recordings. Forests 2022, 13, e935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Maaten, E.; Pape, J.; van der Maaten-Theunissen, M.; Scharnweber, T.; Smiljanić, M.; Cruz-García, R.; Wilmking, M. Distinct growth phenology but similar daily stem dynamics in three co-occurring broadleaved tree species. Tree Physiol. 2018, 38, 1820–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paredes, D.; Cellini, J.M.; Lencinas, M.V.; Parodi, M.; Quiroz, D.; Ojeda, J.; Farina, S.; Rosas, Y.M.; Martínez Pastur, G. Influencia del paisaje en las cortas de protección en bosques de Nothofagus pumilio: Cambios en la estructura forestal y respuesta de la regeneración. Bosque 2020, 41, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellomäki, S.; Väisänen, H. Modelling the dynamics of the forest ecosystem for climate change studies in the boreal conditions. Ecol. Model. 1997, 97, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Girón, J.C.; Álvarez-Álvarez, P.; Díaz-Varela, E.; Mendes Lopes, D. Influence of climate variations on primary production indicators and on the resilience of forest ecosystems in a future scenario of climate change: Application to sweet chestnut agroforestry systems in the Iberian Peninsula. Ecol. Ind. 2020, 113, e106199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groffman, P.M.; Driscoll, C.T.; Fahey, T.J.; Hardy, J.; Fitzhugh, R.; Tierney, G. Colder soils in a warmer world, A snow manipulation study in a northern hardwood forest ecosystem. Biogeochem. 2001, 56, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpeläinen, J.; Domisch, T.; Lehto, T.; Piirainen, S.; Silvennoinen, R.; Repo, T. Separating the effects of air and soil temperature on silver birch. Part I. Does soil temperature or resource competition determine the timing of root growth? Tree Physiol. 2022, 42, 2480–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, B.; Moura, M.; Pelacani, C.; Angelotti, F.; Taura, T.; Oliveira, G.; Bispo, J.; Matias, J.; Silva, F.; Pritchard, H.; Seal, C. Rainfall, not soil temperature, will limit the seed germination of dry forest species with climate change. Oecologia 2020, 192, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belyazid, S.; Akselsson, C.; Zanchi, G. Water limitation in forest soils regulates the increase in weathering rates under climate change. Forests 2022, 13, e310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmgren, M.; Scheffer, M.; Ezcurra, E.; Gutiérrez, J.; Mohren, G. El Niño effects on the dynamics of terrestrial ecosystems. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2001, 16, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maza-Villalobos, S.; Poorter, L.; Martínez-Ramos, M. Effects of ENSO and temporal rainfall variation on the dynamics of successional communities in old-field succession of a tropical dry forest. PLOS One 2013, 8, e82040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.H.; Jucker, T.; Riutta, T.; Svátek, M.; Kvasnica, J.; Rejžek, M.; Matula, R.; Majalap, N.; Ewers, R.; Swinfield, T.; Valbuena, R.; Vaughn, N.; Asner, G.; Coomes, D. Recovery of logged forest fragments in a human-modified tropical landscape during the 2015-16 El Niño. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, e1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, B.; Zegre, N.; Warner, T.; Fernandez, R.; He, Y.; Merriam, E. Climate, forest growing season, and evapotranspiration changes in the central Appalachian Mountains, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 1371–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prislan, P.; Gričar, J.; Čufar, K.; de Luis, M.; Merela, M.; Rossi, S. Growing season and radial growth predicted for Fagus sylvatica under climate change. Clim. Change 2019, 153, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, J. Tree recruitment at the Nothofagus pumilio alpine timberline in Tierra del Fuego, Chile. J. Ecol. 2000, 88, 840–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamonde, H.A.; Peri, P.L.; Monelos, L.H.; Martínez Pastur, G. Aspectos ecológicos de la regeneración por semillas en bosques nativos de Nothofagus antarctica en Patagonia Sur, Argentina. Bosque 2011, 32, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, F.; Fajardo, A.; Cavieres, L. Simulated warming does not impair seedling survival and growth of Nothofagus pumilio in the southern Andes. Perspec. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2013, 15, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, D.; Knapp, B.; Battaglia, M.; Deal, R.; Hart, J.; O’Hara, K.; Schweitzer, C.; Schuler, T. Barriers to natural regeneration in temperate forests across the USA. New Forests 2019, 50, 11–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chillo, V.; Ladio, A.; Salinas Sanhueza, J.; Soler, R.M.; Arpigiani, D.; Rezzano, C.; Cardozo, A.; Peri, P.L.; Amoroso, M. Silvopastoral systems in northern Argentine-Chilean Andean Patagonia: Ecosystem services provision in a complex territory. In Ecosystem services in Patagonia: A multi-criteria approach for an integrated assessment; Peri, P.L., Martínez Pastur, G., Nahuelhual, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2021; pp 115-138. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt, J.A.; Florez Yepes, G.; Hernández García, D. Innovation in agricultural systems facing climate change. J. Southwest Jiaotong Univ. 2022, 57, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | BA | TD | TOBV | OC | TR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CF | 34.5c | 1789b | 172.4c | 73.1c | 37.2a |

| OF | 22.5b | 599ab | 117.3b | 53.7b | 61.9b |

| EF | <0.1a | <1a | <0.1a | 7.1a | 91.3c |

| F(p) | 42.15(<0.001) | 4.31(0.048) | 44.03(<0.001) | 63.42(<0.001) | 21.41(0.001) |

| SD | SC | SN | SP | LD | |

| CF | 0.712a | 14.96 | 0.684 | 0.422a | 1.06a |

| OF | 0.976b | 14.31 | 0.738 | 0.549b | 4.36b |

| EF | 0.802a | 13.94 | 0.691 | 0.419a | 1.02a |

| F(p) | 17.48(0.001) | 0.51(0.615) | 0.47(0.641) | 6.46(0.018) | 4.89(0.036) |

| RIC | UB | UC | DC | BS | |

| CF | 37.75b | 497.3a | 166.5b | 6.50b | 6.0 |

| OF | 36.75b | 714.1a | 149.0ab | 0.50a | 7.5 |

| EF | 28.25s | 3932.8b | 116.4a | 0.25a | 21.5 |

| F(p) | 6.53(0.018) | 5.77(0.024) | 6.60(0.017) | 7.61(0.012) | 4.46(0.045) |

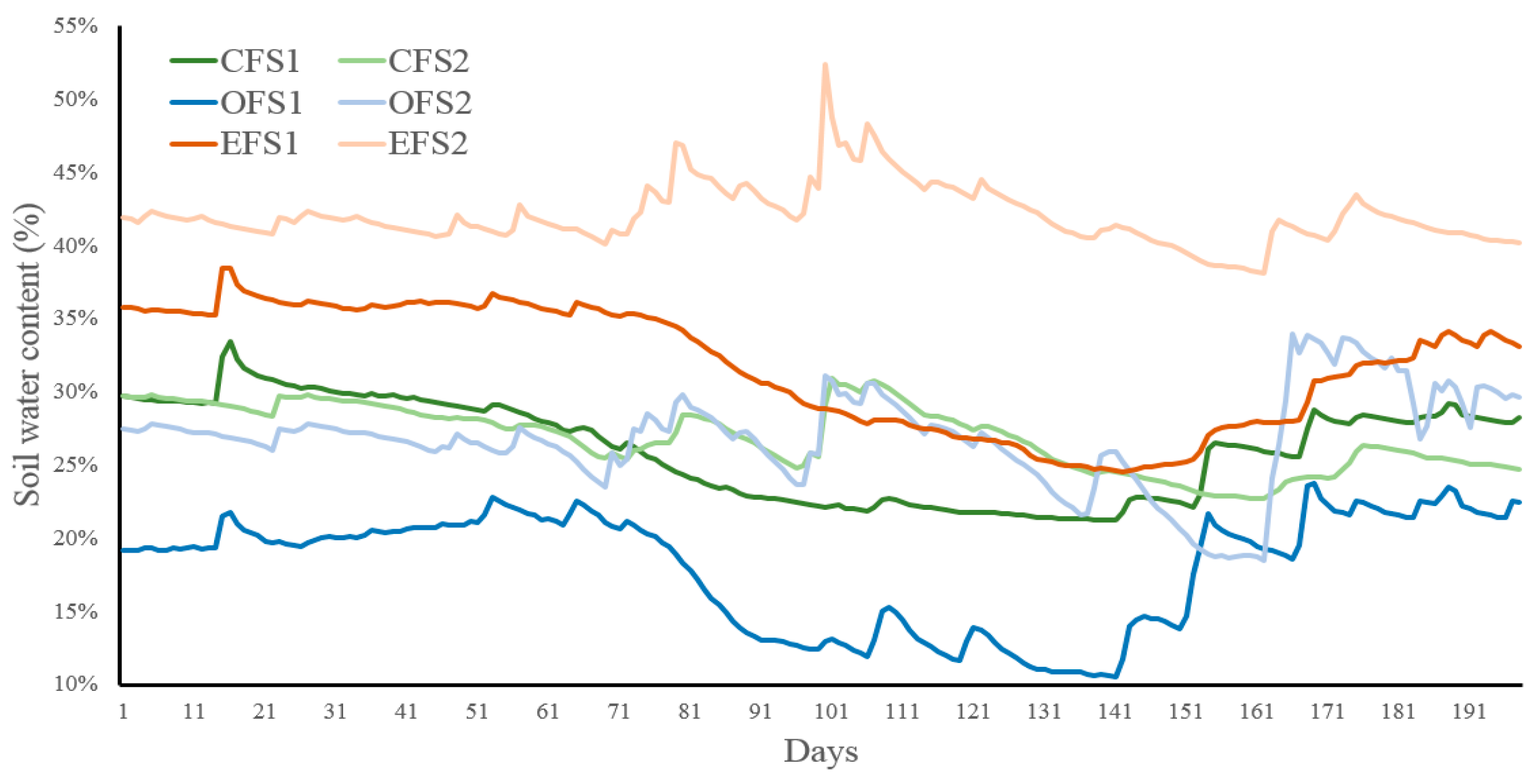

| Treatment | Level | SWC | GI |

|---|---|---|---|

| A: Treatment | CF | 26.7b | 0.0024 |

| OP | 22.4a | 0.0064 | |

| EP | 36.9c | 0.0134 | |

| F(p) | 2296.47(<0.001) | 2.97(0.052) | |

| B: Phase | Early | 30.5c | 0.0048a |

| Medium | 28.5b | 0.0176b | |

| Late | 27.1a | -0.0001a | |

| F(p) | 105.5(<0.001) | 11.89(<0.001) | |

| C: Season | 1 | 25.6a | 0.0052 |

| 2 | 31.8b | 0.0097 | |

| F(p) | 1190.99(<0.001) | 1.48(0.224) | |

| Interactions | A x B | 22.44(<0.001) | 2.97(0.019) |

| A x C | 282.05(<0.001) | 0.03(0.968) | |

| B x C | 44.29(<0.001) | 0.60(0.548) |

| Treatment | Level | CF | OF | EF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: Phase | Early | 0.0154 | 0.0124ab | 0.0133ab |

| Medium | 0.0058 | 0.0225b | 0.0406ab | |

| Late | 0.0087 | 0.0087a | 0.0091a | |

| F(p) | 0.33(0.719) | 3.01(0.049) | 6.89(0.001) | |

| B: Rainfall | 0.0 | -0.0082a | -0.0051a | 0.0024a |

| 0.0-0.2 | -0.0008ab | 0.0059a | 0.0113a | |

| 0.2-1.0 | 0.0195ab | 0.0161ab | 0.0245ab | |

| >1.0 | 0.0293b | 0.0412b | 0.0459b | |

| F(p) | 6.93(<0.001) | 21.03(<0.001) | 7.53(<0.001) | |

| C: Season | 1 | 0.0065 | 0.0132 | 0.0171 |

| 2 | 0.0134 | 0.0158 | 0.0249 | |

| F(p) | 0.61(0.435) | 0.23(0.633) | 0.76(0.385) | |

| Interactions | A x B | 1.82(0.095) | 1.25(0.279) | 0.78(0.586) |

| A x C | 0.06(0.944) | 0.53(0.589) | <0.01(0.997) | |

| B x C | 0.61(0.612) | 3.46(0.017) | 1.02(0.385) |

| Treatment | Level | CF | OF | EF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: Phase | Early | 0.0028 | -0.0011a | 0.0001ab |

| Medium | -0.0011 | 0.0159b | 0.0271b | |

| Late | -0.0013 | 0.0002ab | -0.0003a | |

| F(p) | 0.07(0.934) | 4.64(0.010) | 6.47(0.002) | |

| B: Air temperature | <8.0 | -0.0039 | 0.0044 | 0.0091 |

| 8.0-10.0 | 0.0015 | 0.0086 | 0.0104 | |

| >10.0 | 0.0028 | 0.0021 | 0.0072 | |

| F(p) | 0.24(0.787) | 0.34(0.709) | 0.03(0.966) | |

| C: Season | 1 | -0.0005 | 0.0035 | 0.0058 |

| 2 | 0.0007 | 0.0066 | 0.0121 | |

| F(p) | 0.02(0.888) | 0.37(0.543) | 0.67(0.413) | |

| Interactions | A x B | 0.66(0.618) | 0.35(0.846) | 0.86(0.490) |

| A x C | 0.53(0.590) | 0.34(0.713) | 0.72(0.488) | |

| B x C | 0.41(0.662) | 0.13(0.874) | 0.52(0.594) |

| Treatment | Level | CF | OF | EF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: Phase | Early | -0.0007 | 0.0029 | 0.0074 |

| Medium | 0.0109 | 0.0012 | -0.0158 | |

| Late | -0.0043 | -0.0019 | -0.0039 | |

| F(p) | 0.21(0.809) | 0.12(0.180) | 0.64(0.527) | |

| B: Soil Temperature | <8.0 | 0.0062 | -0.0073 | -0.0234a |

| >8.0 | -0.0022 | 0.0088 | 0.0152b | |

| F(p) | 0.24(0.626) | 1.8(0.180) | 4.87(0.028) | |

| C: Season | 1 | 0.0011 | 0.0001 | -0.0056 |

| 2 | 0.0028 | 0.0013 | -0.0026 | |

| F(p) | 0.02(0.894) | 0.04(0.849) | 0.10(0.748) | |

| Interactions | A x B | 0.49(0.615) | 0.28(0.754) | 1.58(0.207) |

| A x C | 0.96(0.328) | 0.16(0.689) | 0.06(0.799) | |

| B x C | 0.85(0.428) | 0.16(0.852) | 0.11(0.899) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).