3.1.2. Fuzzy Numbers

A real FN

A is described as any fuzzy subset of the real line

R with a membership function

that possesses the following properties [

58].

is a continuous mapping from

R to [0,1],

.

is strictly increasing on the left membership function

and is strictly decreasing on the right membership function

.

and

, where a, b, c, and d are real numbers.

We may let , or a=b, or b=c, or c=d, or d=. Unless elsewhere defined, A is assumed to be convex, normalized, and bounded, i.e., , . A can be indicated as , . Let represent and represent the left and the right membership function of A, respectively, and

In this research, TFNs will be used. The FN

A is a TFN if its membership function

is given as follows [72].

where

a,

b and

c are real numbers.

3.1.3. α-Cuts

The α-cuts of FN

A can be determined as

, where

is a non-empty bounded closed interval is contained in

R and can be denoted by

, where

are lower bounds and

are upper bounds [

62].

3.1.6. Relative Maximizing and Minimizing Sets

Chu and Nguyen [

61] suggested a technique to improve Chen’s [

49] maximizing and minimizing set to rank FNs. In their study, numerical comparisons and example were conducted to demonstrate that the RMMS can consistently and logically rank fuzzy values of alternatives. The RMMS [

61] technique is introduced as follows.

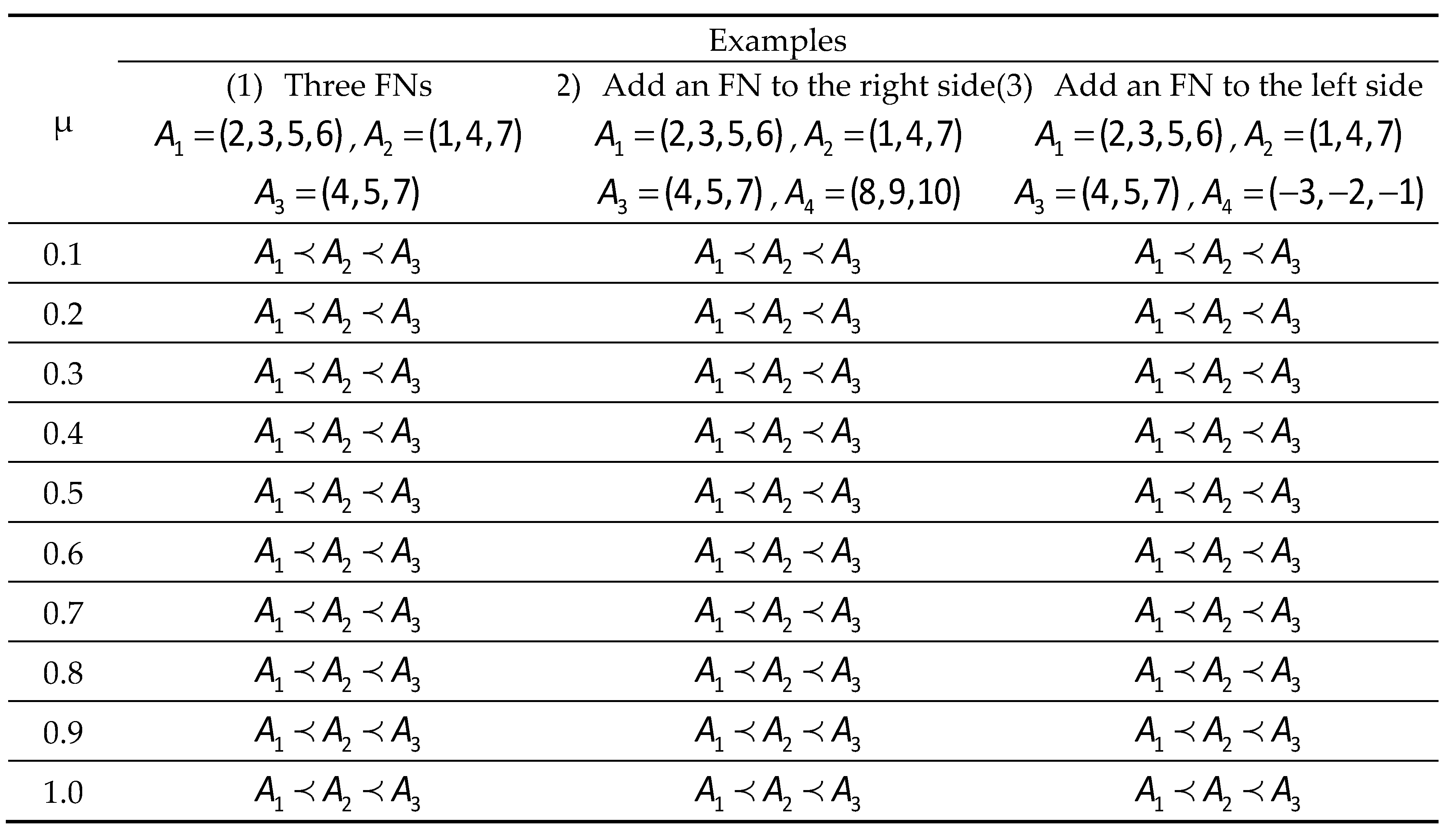

Assume there are n FNs,. , FNs and are added to the right and left sides of the above n FNs , respectively. Assume , , and . Let and , where , , , . The new supremum element is defined as and the new infimum element is defined as , where .

The relative maximizing set

and the relative minimizing set

are determined as:

Herein,

k is set to 1. The value of

k can be varied to suit the application. The total relative utility of each

Ai is denoted as in Eq. (8).

where the first right relative utility

, the first left relative utility

, the second left relative utility

and the second right relative utility

.

3.1.7. Spread area-based RMMS

In 2011, Nejad and Mashinchi [

57] pointed out the shortcomings of Wang et al.’s [

52] deviation degree method that when the values of the left area, the right area, the transfer coefficient

or

is zero, the ranking result is inaccurate. Hence, to prevent these problems from occurring, expanding

and

is needed when ranking. Chu and Nguyen [

61] also found out that when adding a new FN,

and

must be modified by adding equal values to consider both sides of membership functions. Consequently, four utilities need to be accounted for to reduce the inconsistency of Chen’s [

49] maximizing and minimizing set. However, if a set of FNs with

, then a new FN

is added, there is no extended value applicable in this situation. Therefore, this work suggests to integrate confidence level in ranking FNs to solve the mentioned problems.

Yeh and Kuo [

64] in their research on evaluating passenger service quality of Asia-Pacific international airports, suggested incorporating a DM’s confidence level α and a preference index λ to obtain an overall service performance index. In the evaluation procedure, DMs give the value α, based on the concept of an α-cut, with respect to the criteria’s weights and alternative performance ratings.

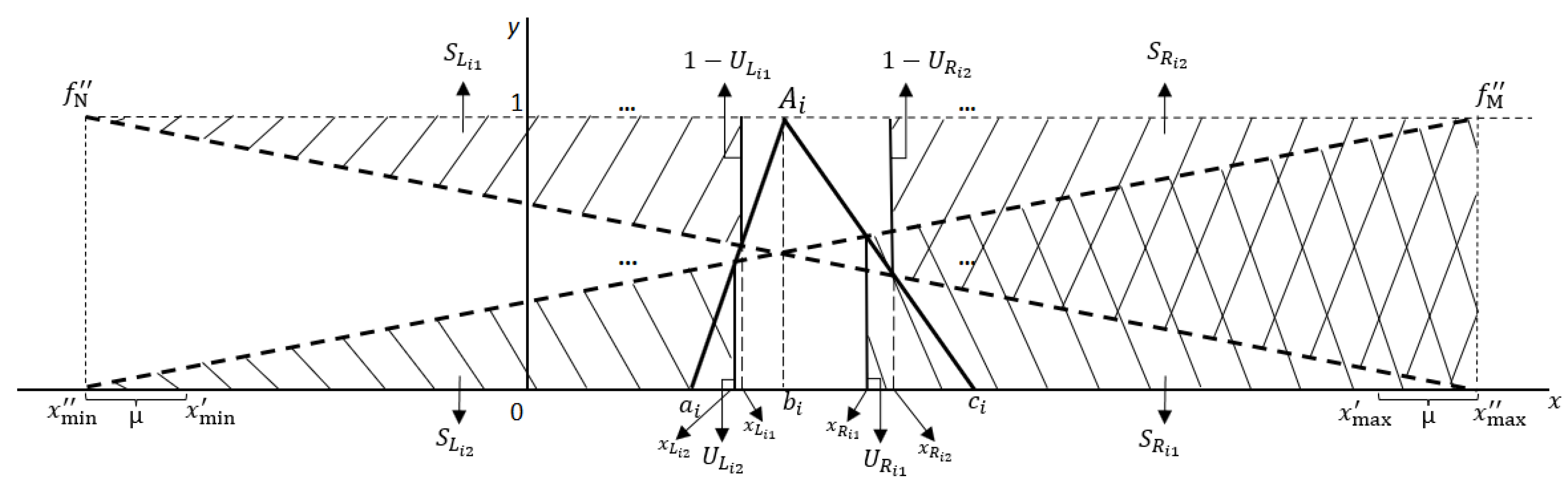

This work proposes to use confidence level in a new perspective, which is confidence level, symbolized as

μ, will be integrated into measuring areas spreading based on the RMMS model to assist the ranking FNs procedure, as shown in

Figure 1. First,

h experts in the group of DMs,

are asked to specify their confidence

, representing their confidence for alternatives to obtain

. The greater the

μ, the more assured is the decision-maker on the alternative.

Since DMs’ confidence in an alternative will influence their confidence level in other alternatives, the confidence level μ, calculated by the average of all DMs’ evaluation, should be engaged simultaneously to the immensity of the RMMS concept. Accordingly, value μ is integrated by shifting the RMMS’s infimum element to the left, provided that the new infimum element is obtained as . Similarly, the average value of μ will be integrated by shifting the RMMS’s infimum element to the right, provided that the new supremum element is obtained as .

The coordinates of the intersect of the

with the relative maximizing set

and the relative minimizing set

can be seen in

Figure 1 and are determined as the following equations.

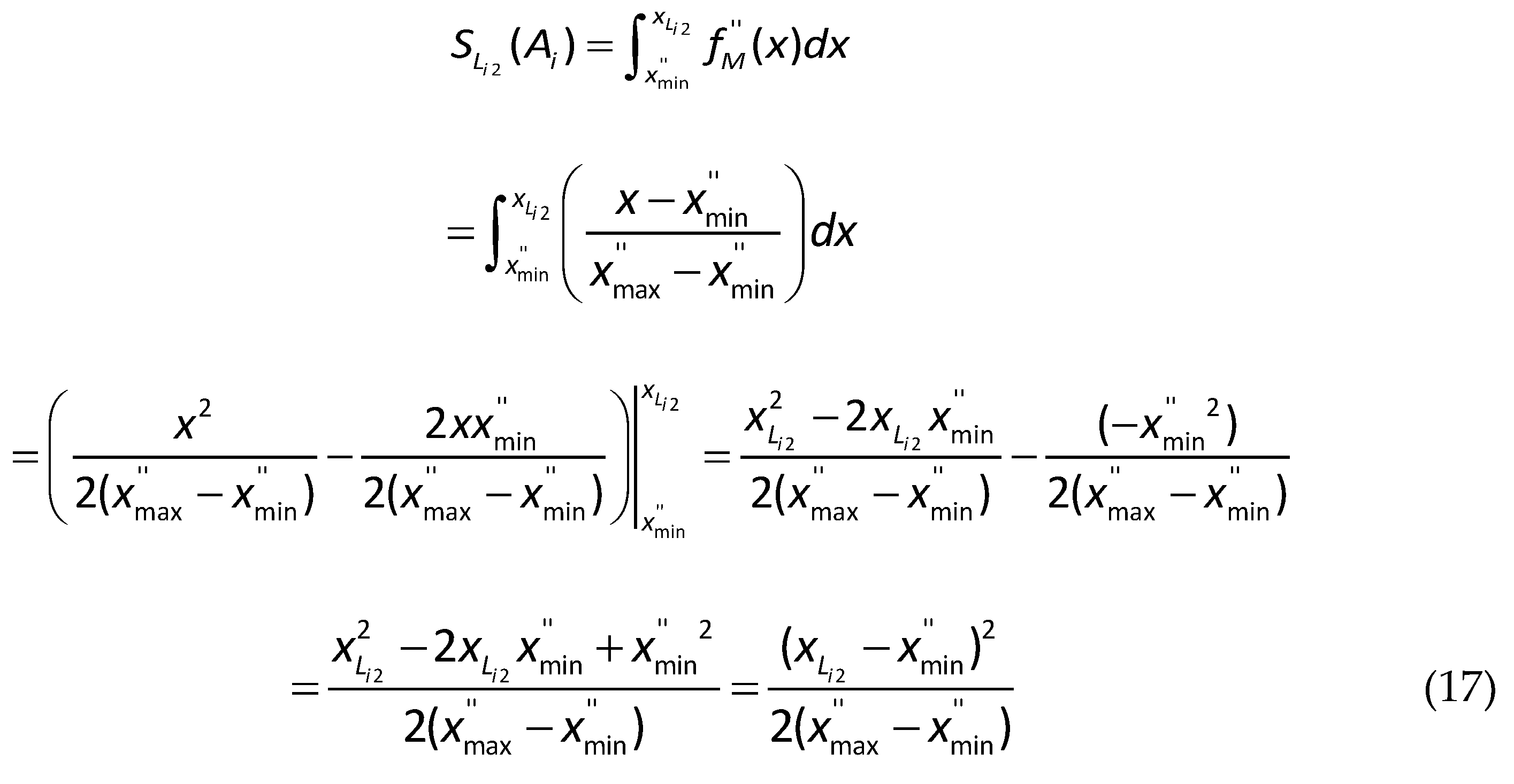

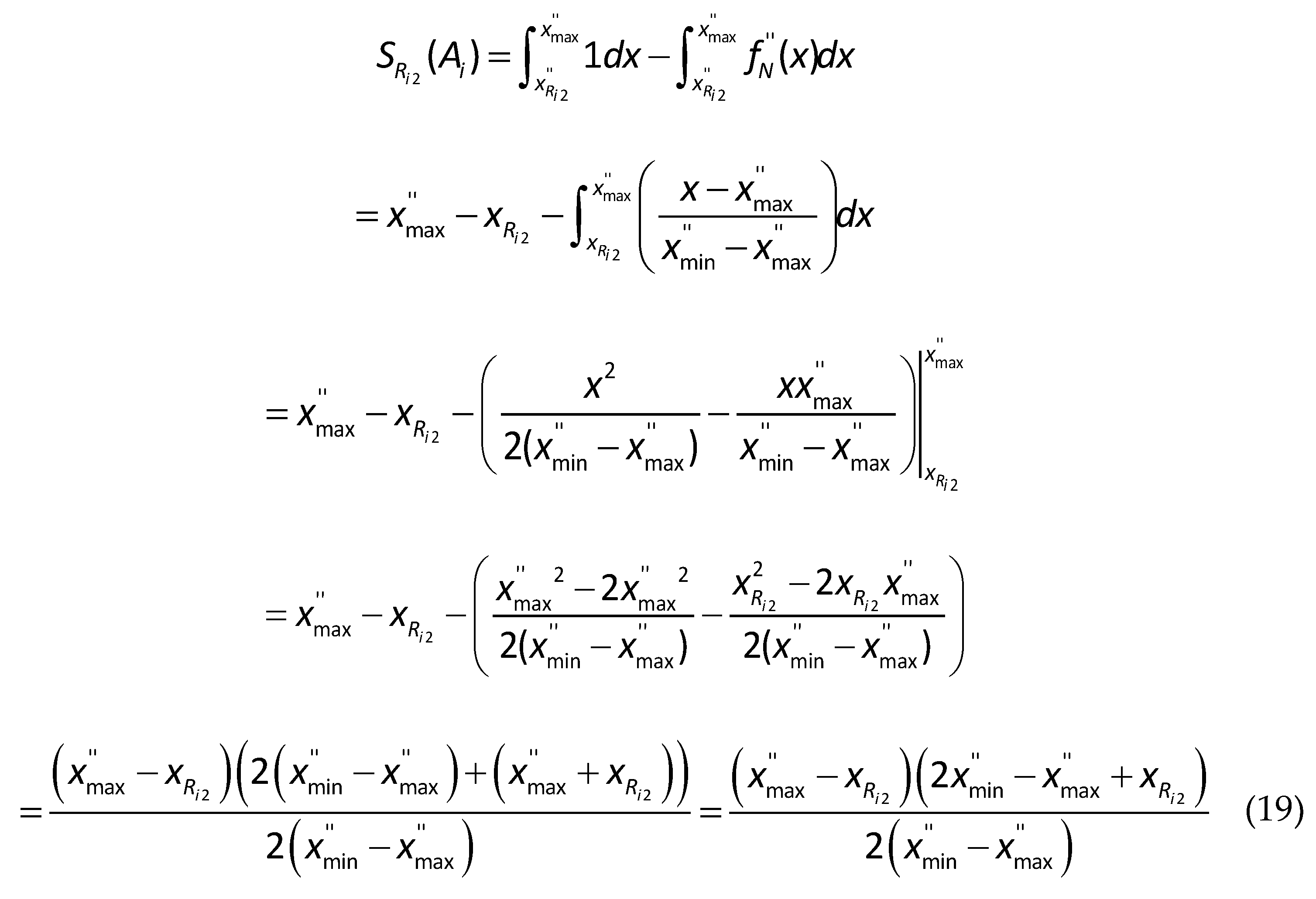

The first left spread area

is defined as follows.

Clearly, if the first left spread area

is larger, fuzzy number

is larger. The second left spread area

is defined as Eq. (14); and if

is larger, fuzzy number

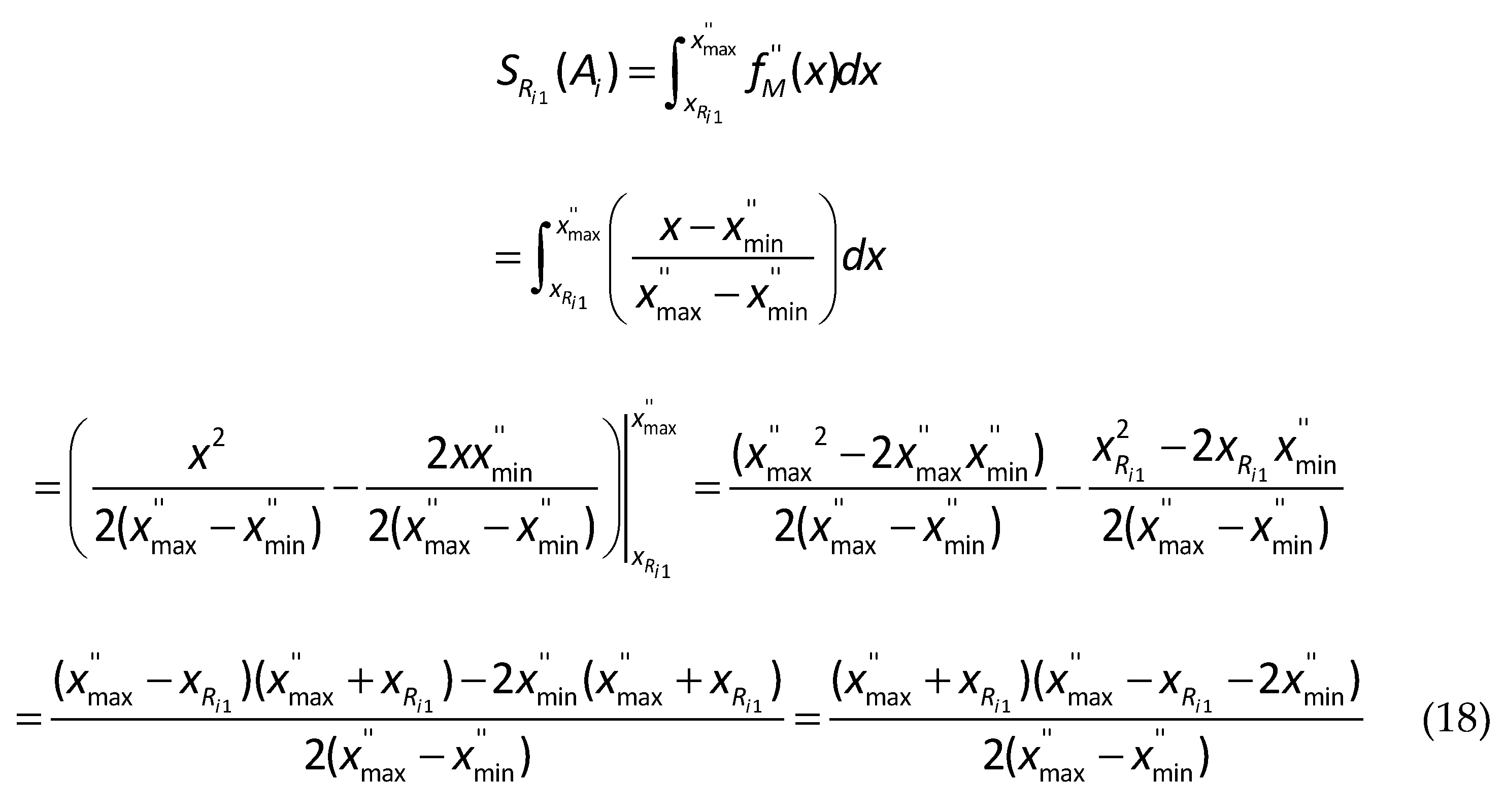

is also larger. The first right spread area

is defined as Eq. (15); but if

is lager, fuzzy number

is smaller. Finally, the second right spread area

is defined as Eq. (16); and if

is larger, fuzzy number

is also smaller. Therefore, the above four areas must be considered when ranking FNs. The detailed derivation for Eqs. (14)-(16) is placed in

Appendix I.

Finally, the ranking value of each

is determined as Eq. (17) to classify FNs. An FN is more prominent if its value is larger.

3.1.8. The hybrid DEMATEL-ANP based fuzzy PROMETHEE II model

DEMATEL

The DEMATEL method is first used to demonstrate the interrelationships between criteria and produce the influential network relationship map. The constructing equations of the classical DEMATEL model can be summarized as follows [

65].

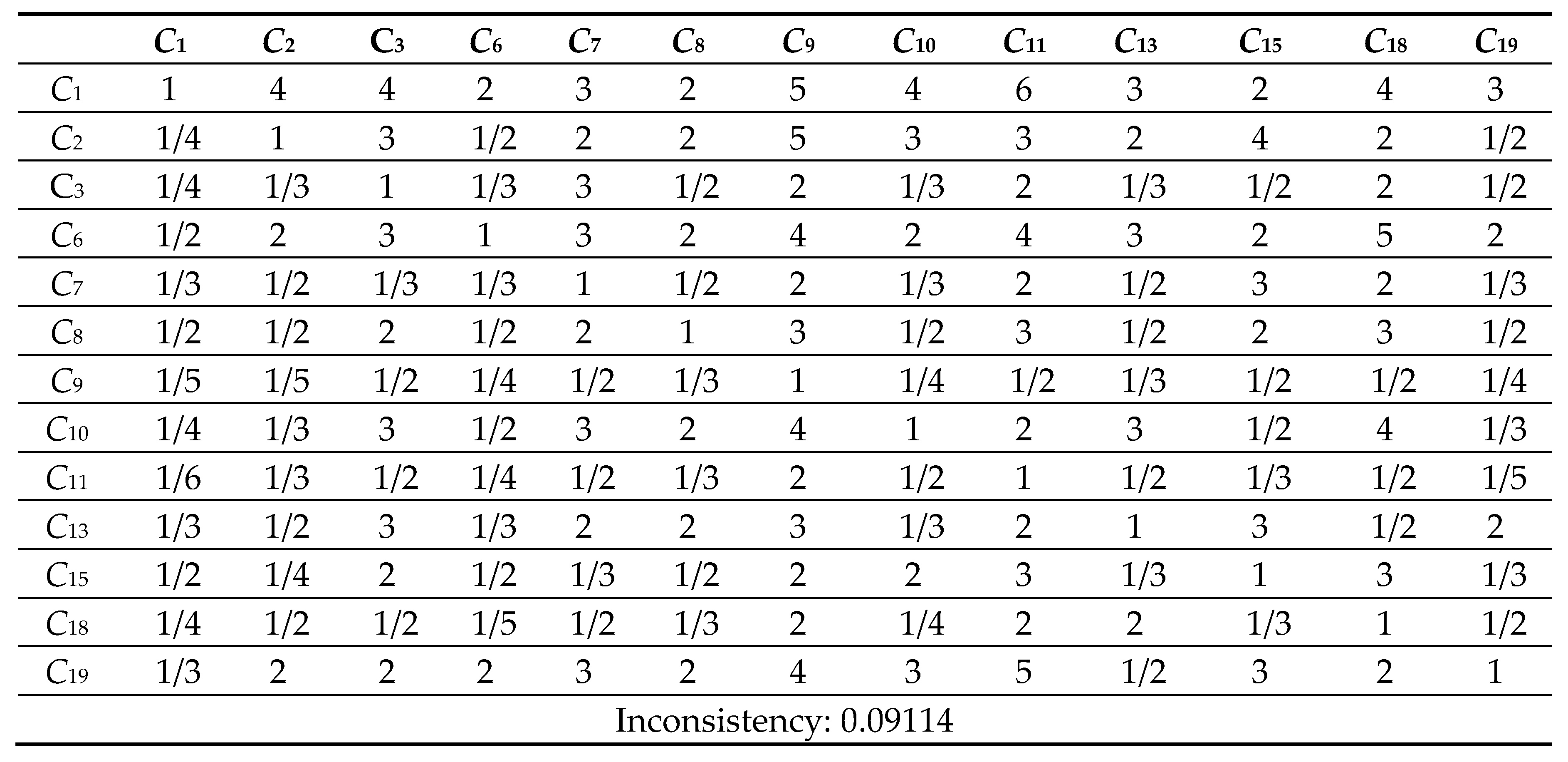

Assume that h experts in a decision groupare asked to indicate the direct effect of factor (criterion) Ci has on factor (criterion) Cj in a system with m factors (criteria)using an integer scale of No Effect (0), Low Effect (1), Medium Low Effect (2), Medium Effect (3), Medium High Effect (4), High Effect (5) and Extremely Strong Effect (6). Next, the individual direct-influence matrix provided by the eth expert can be constructed, where all main diagonal components are equal to zero and represent the respondent’s evaluation of DM on the degree to which criterion Ci affects Cj.

Step 1. Generating the group direct-influence matrix. By aggregating

h DMs’ judgments, the group direct-influence matrix

can be constructed by)

Step 2. Acquiring the normalized direct-influence matrix. At this step, the normalized direct influence matrix by the eth expert is .

The following equations calculate the average matrix X

Step 3. Computing the total-influence matrix T. The total-influence matrix is computed the summation of the direct impacts and all of the indirect impacts by Eq. (21)

(21)

when in identity matrix, named as I.

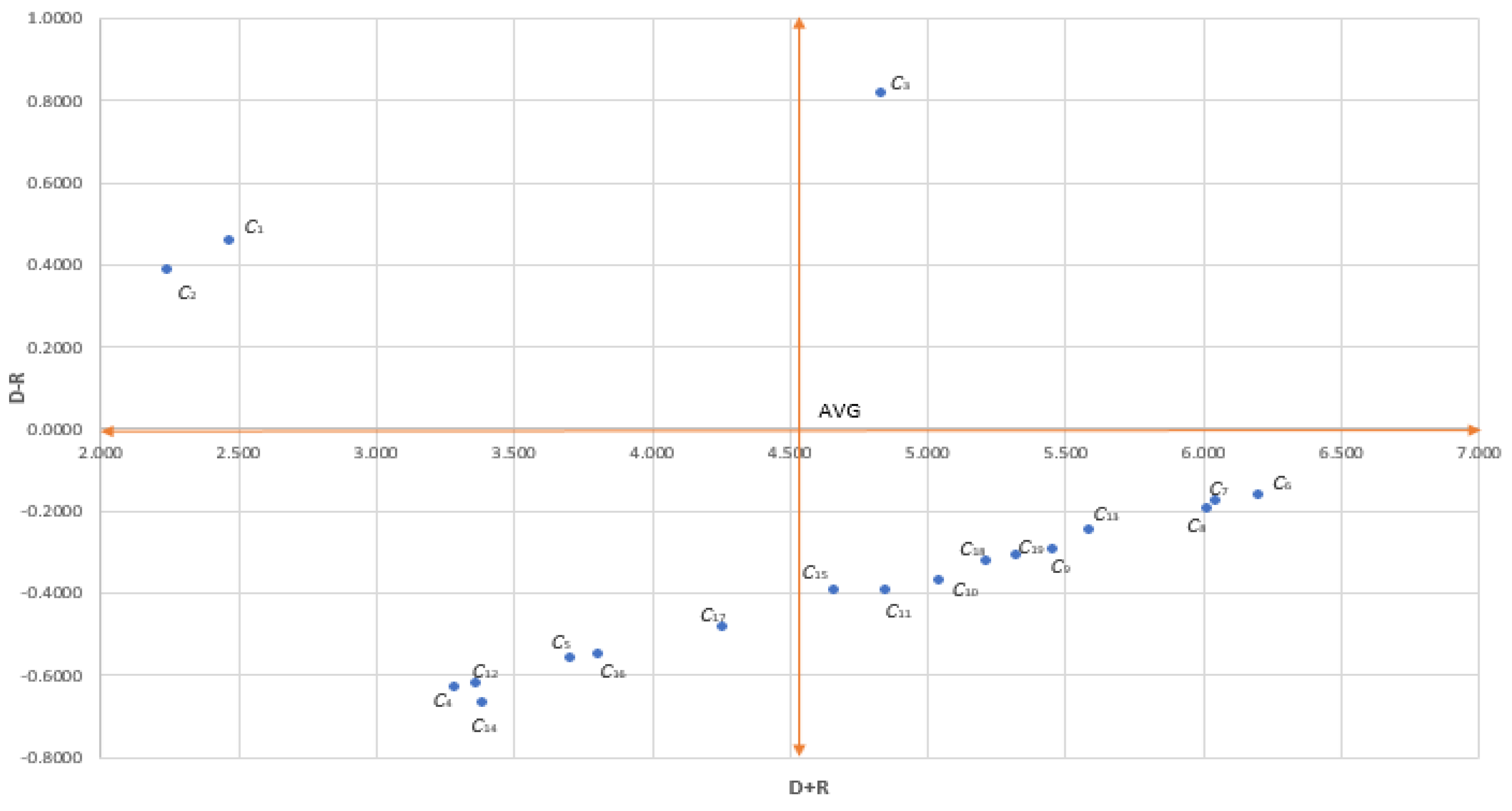

Step 4. Setting up a threshold value and producing the causal diagram.

The sum of columns and the sum of rows are symbolized as

R and

D, respectively, within the total-relation matrix

by the following formulas

The horizontal axis vector (

D +

R) called “Prominence” demonstrates the power of influence degree that is given and received by the criteria. The vertical axis vector (

D -

R) named “Relation” shows the system’s criteria effect. If (

D –

R) is positive, the criterion

Cj influences other criteria and can be grouped into a causal group; if (

D +

R) is negative, the criterion

Cj is being influenced by the other criteria and can be grouped into an effect group. A causal diagram can be produced by mapping the (D + R, D - R) dataset, yielding valuable assessment perception. A threshold value can be defined to screen out the negligible factors [

66,

67]. In this work, factors that have a value higher than the average value of the “Prominence” (

D +

R) and/or (

D –

R) is positive are selected to use in the next step.

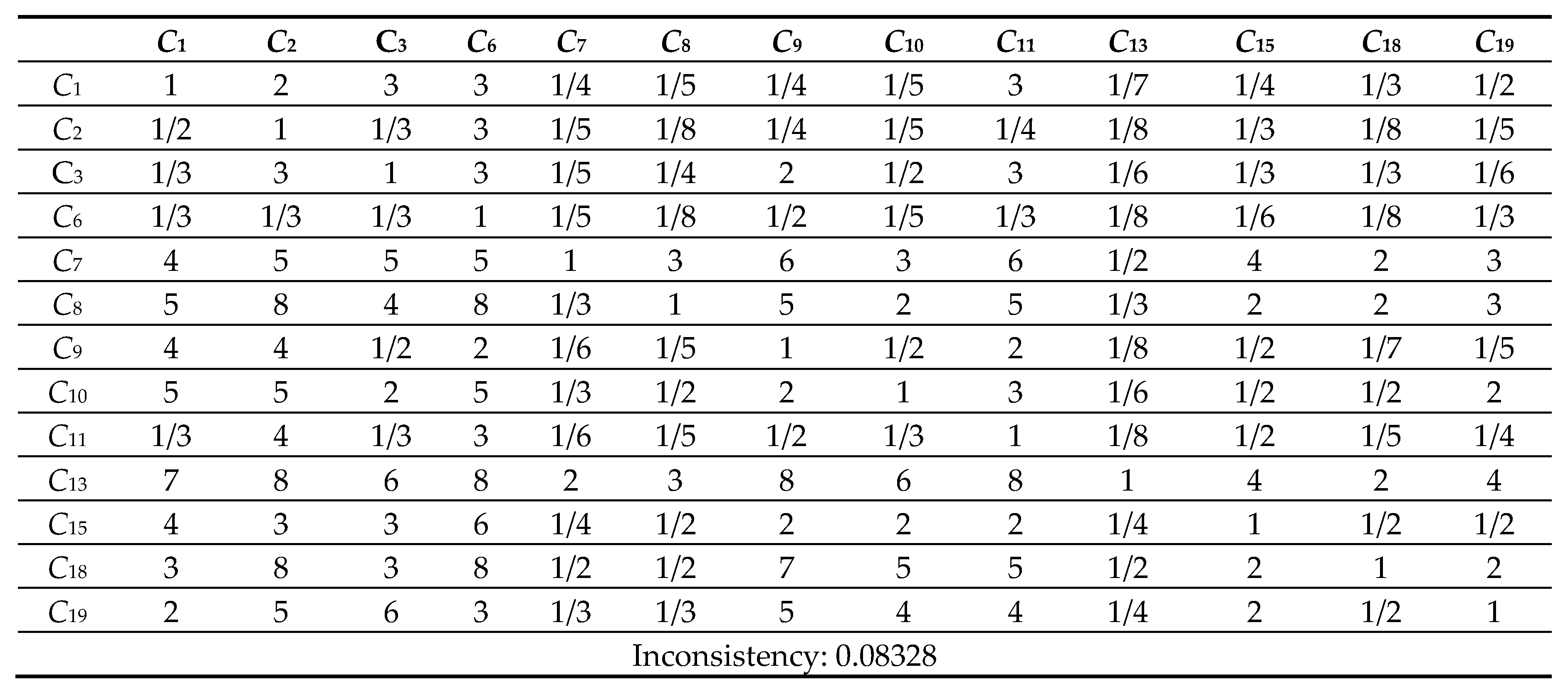

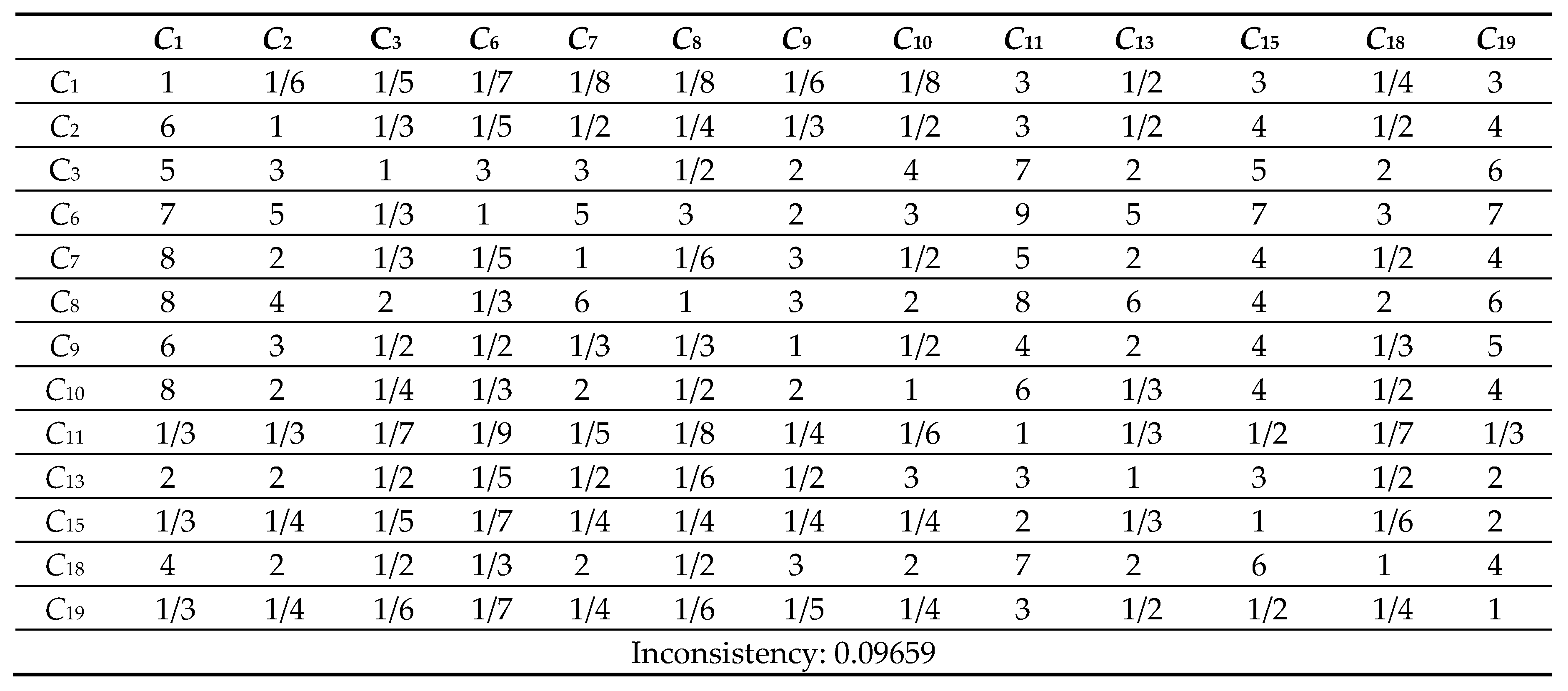

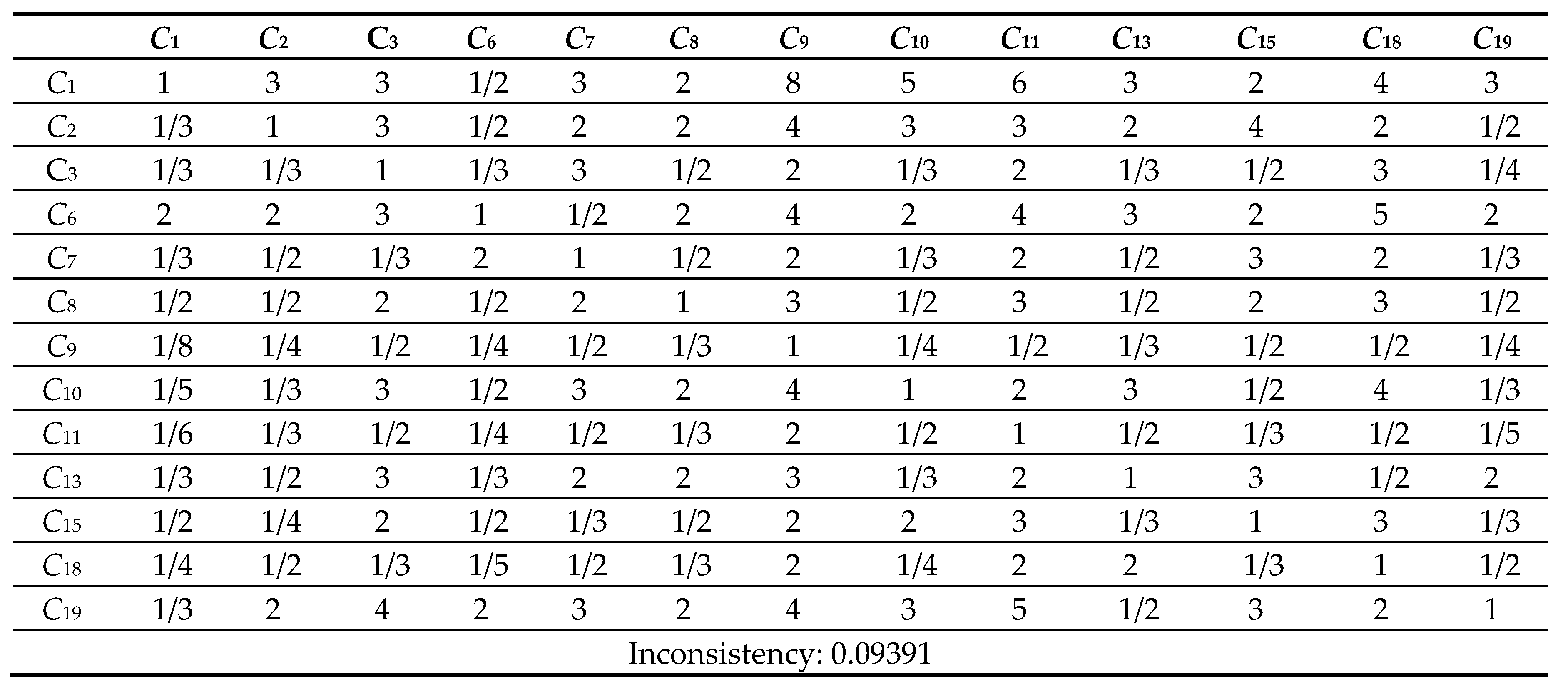

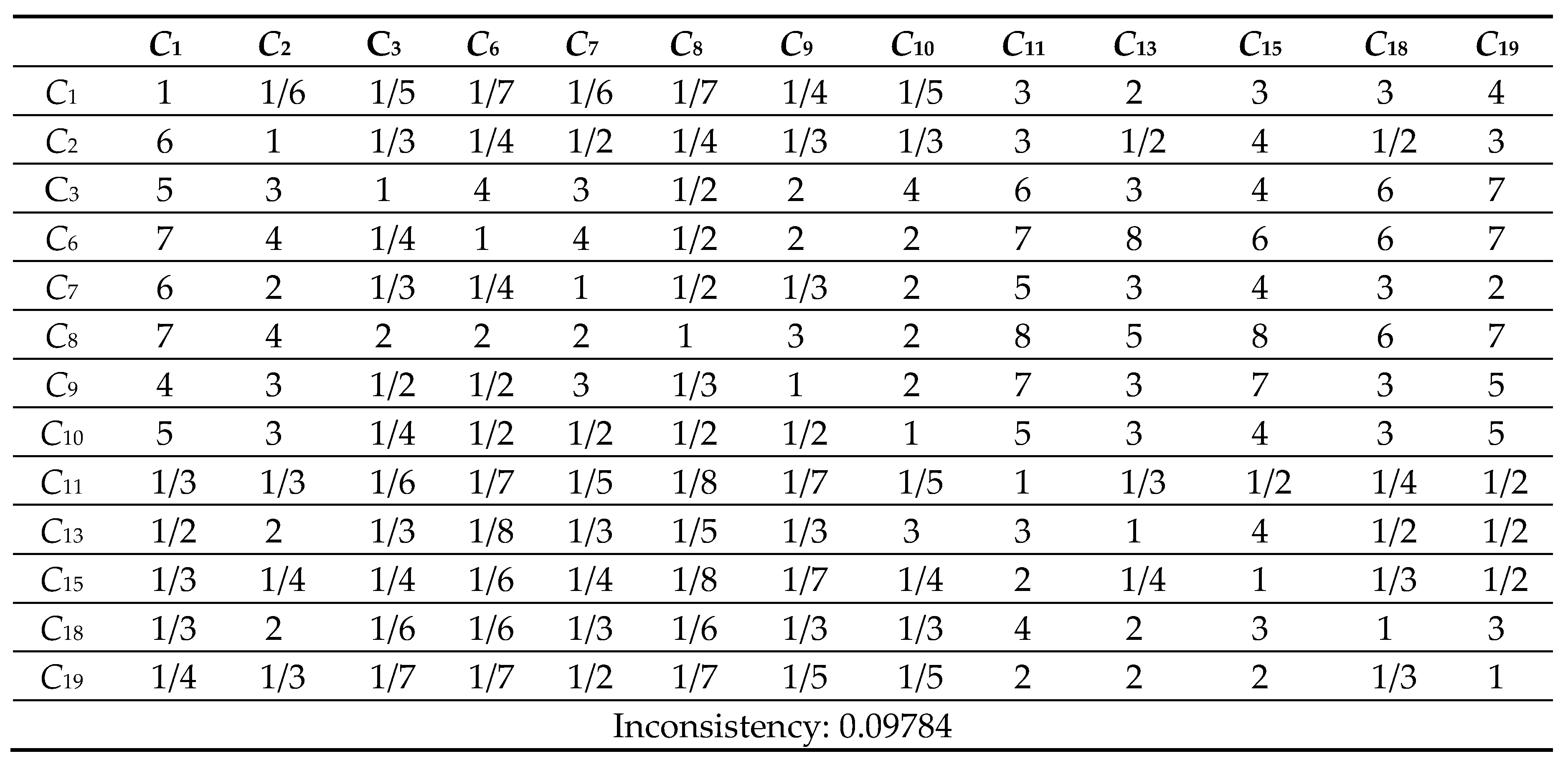

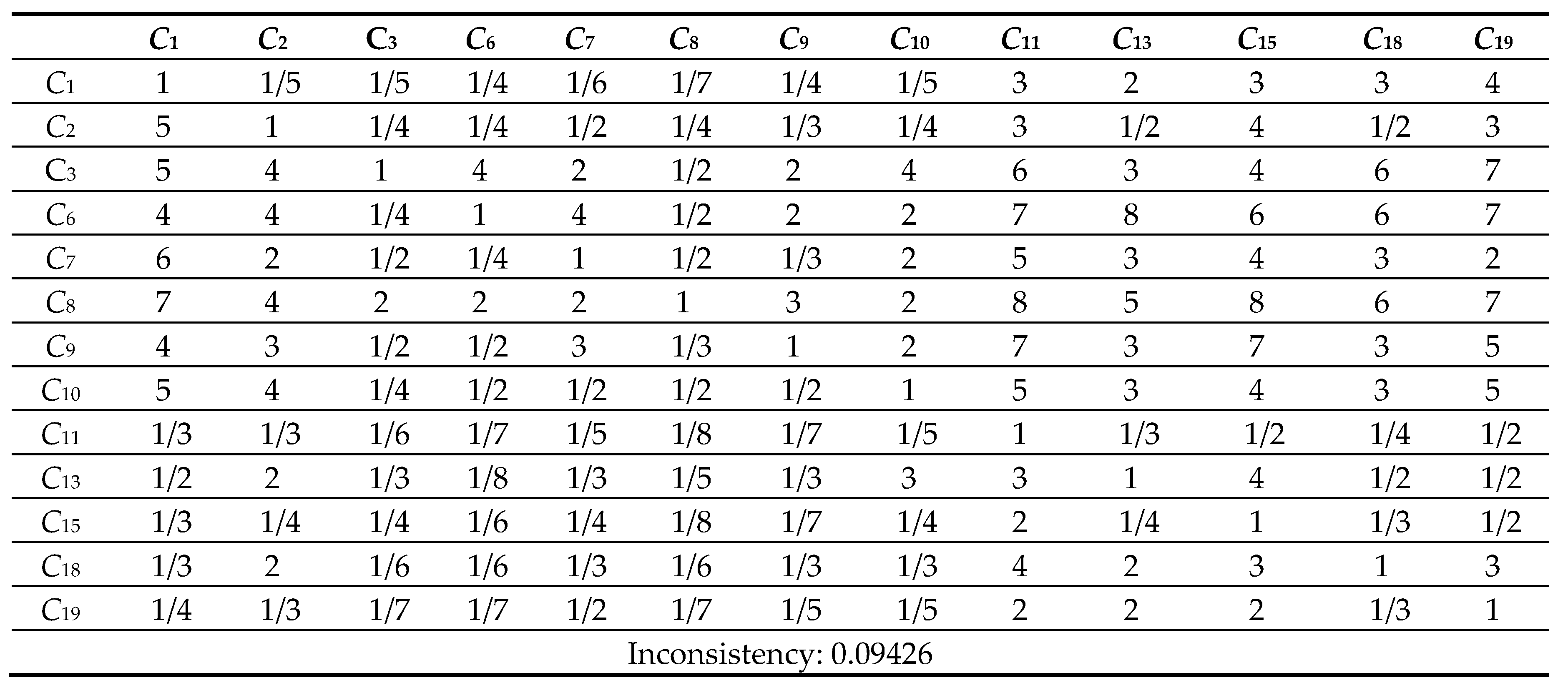

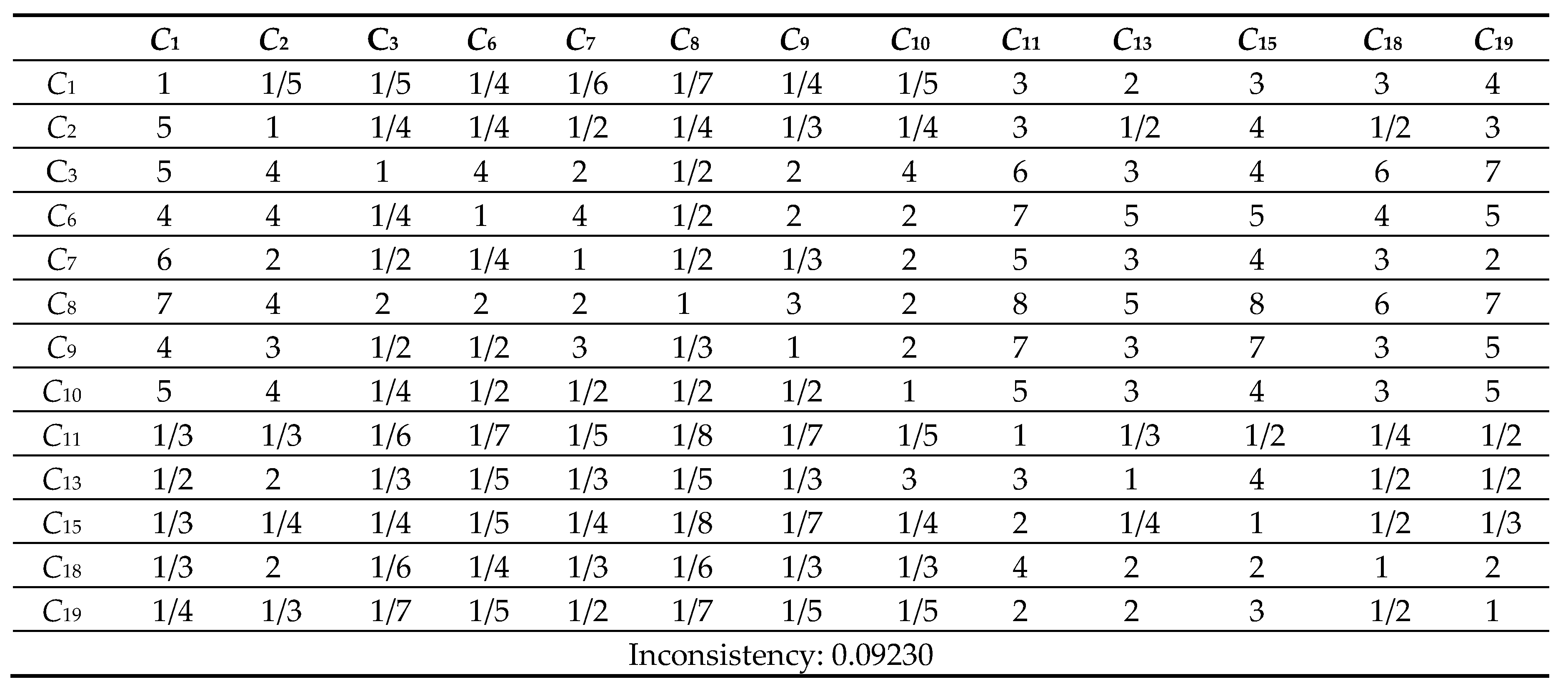

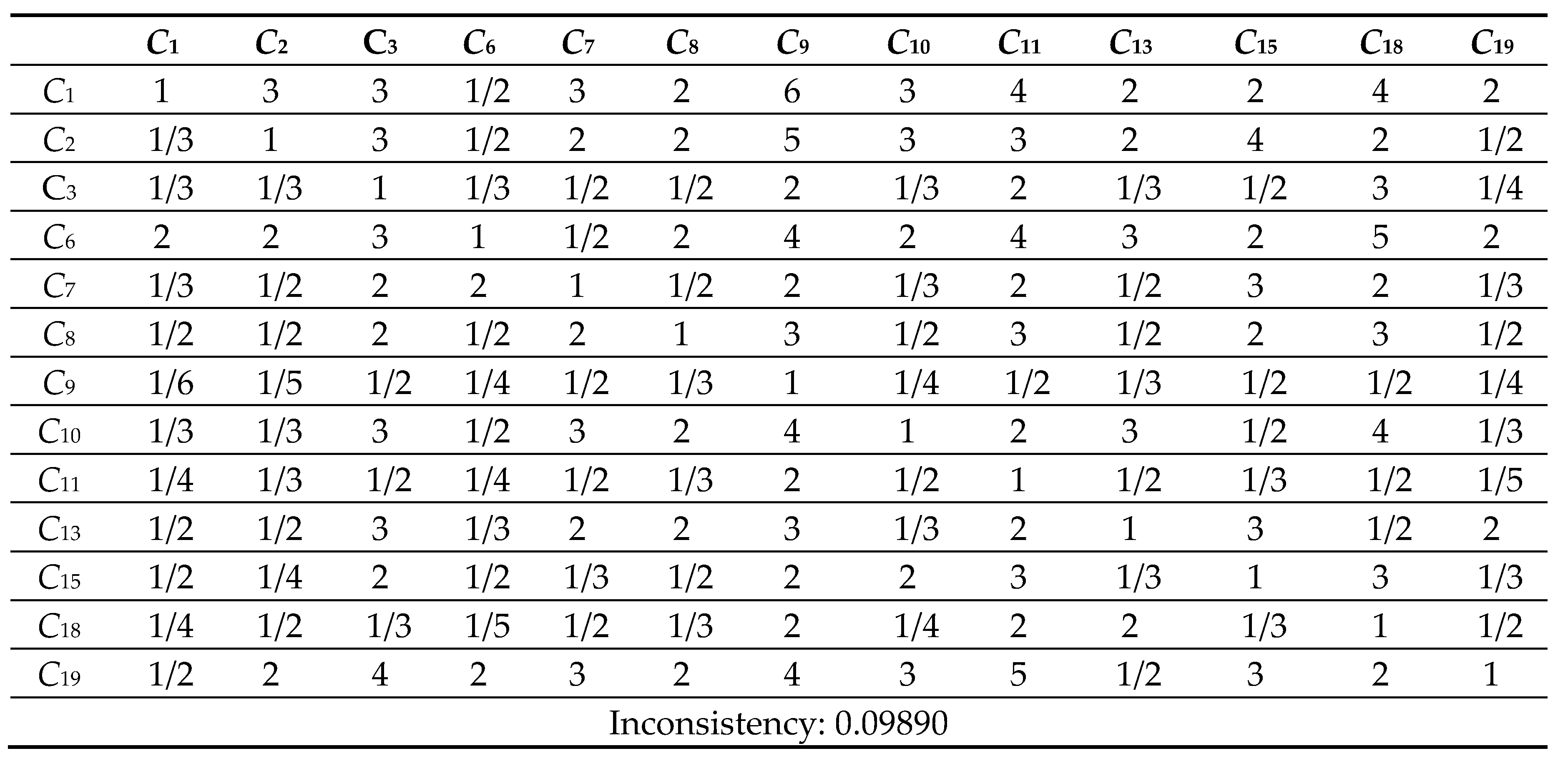

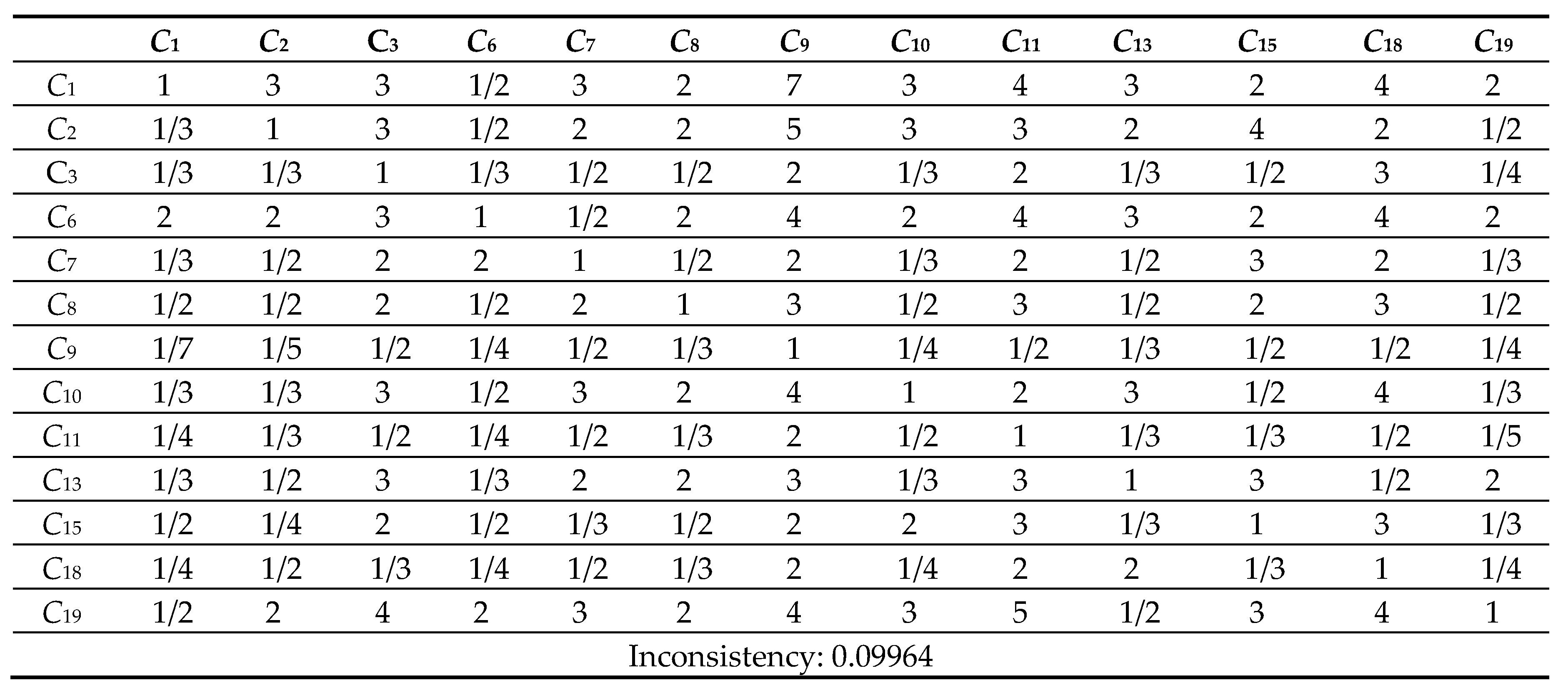

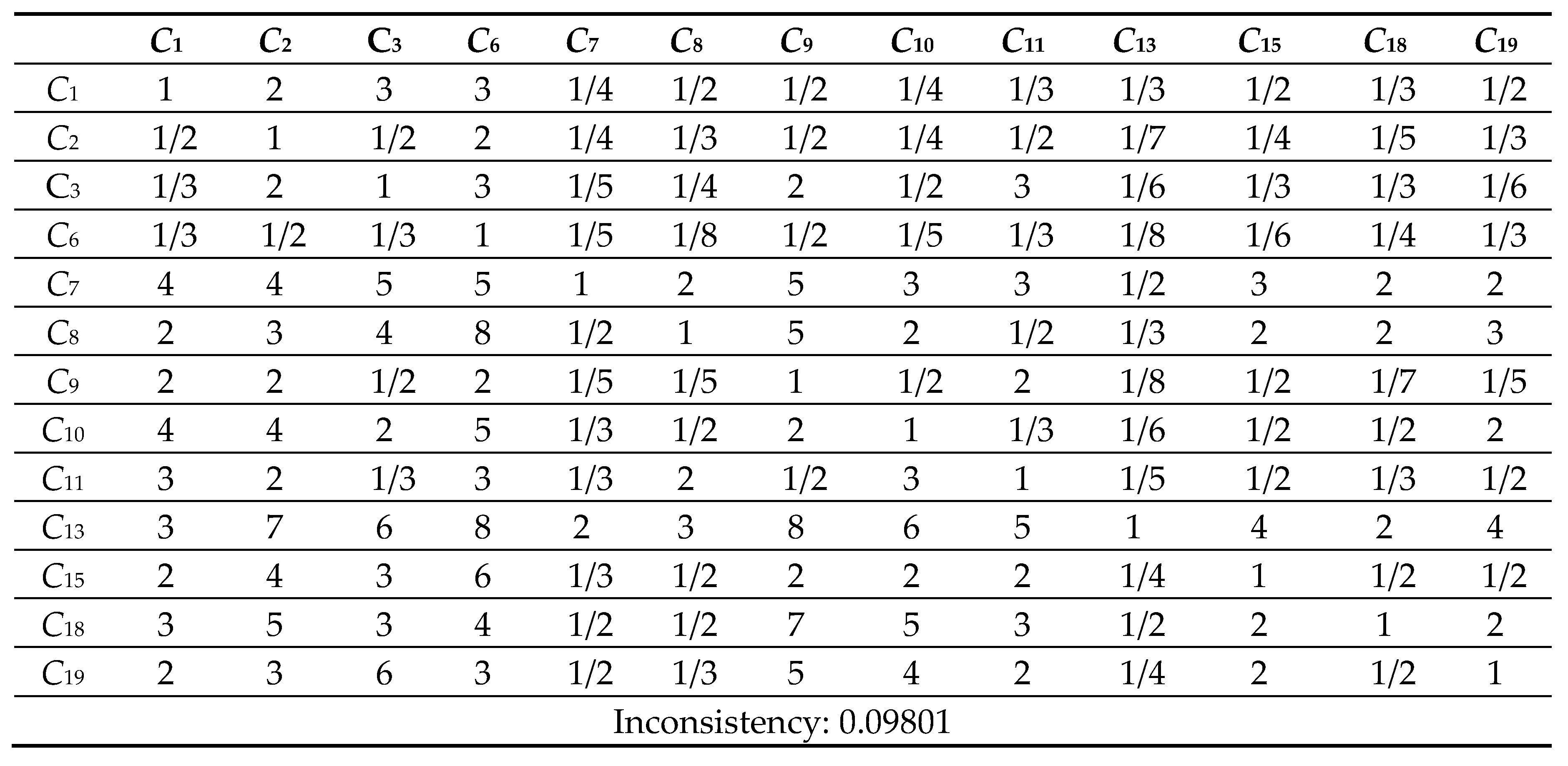

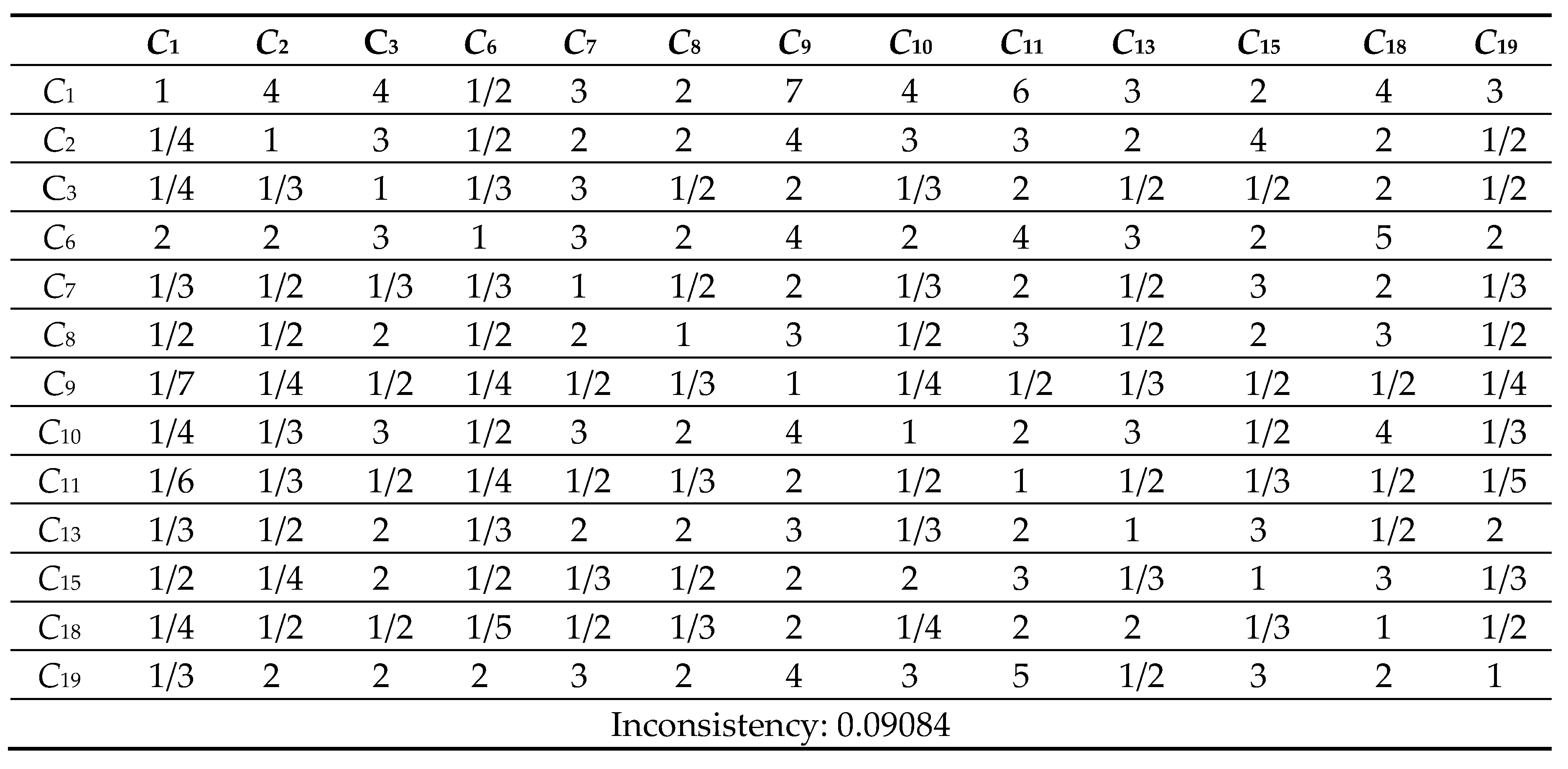

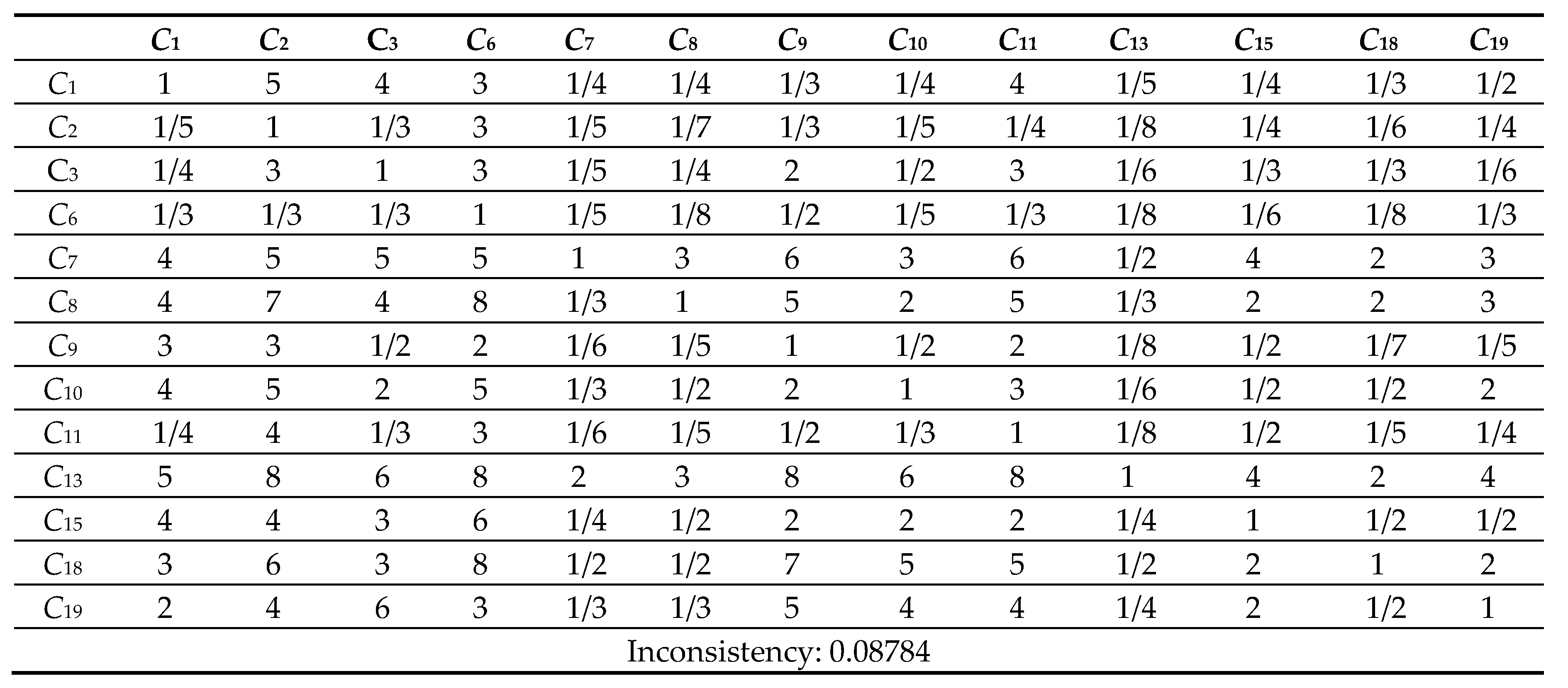

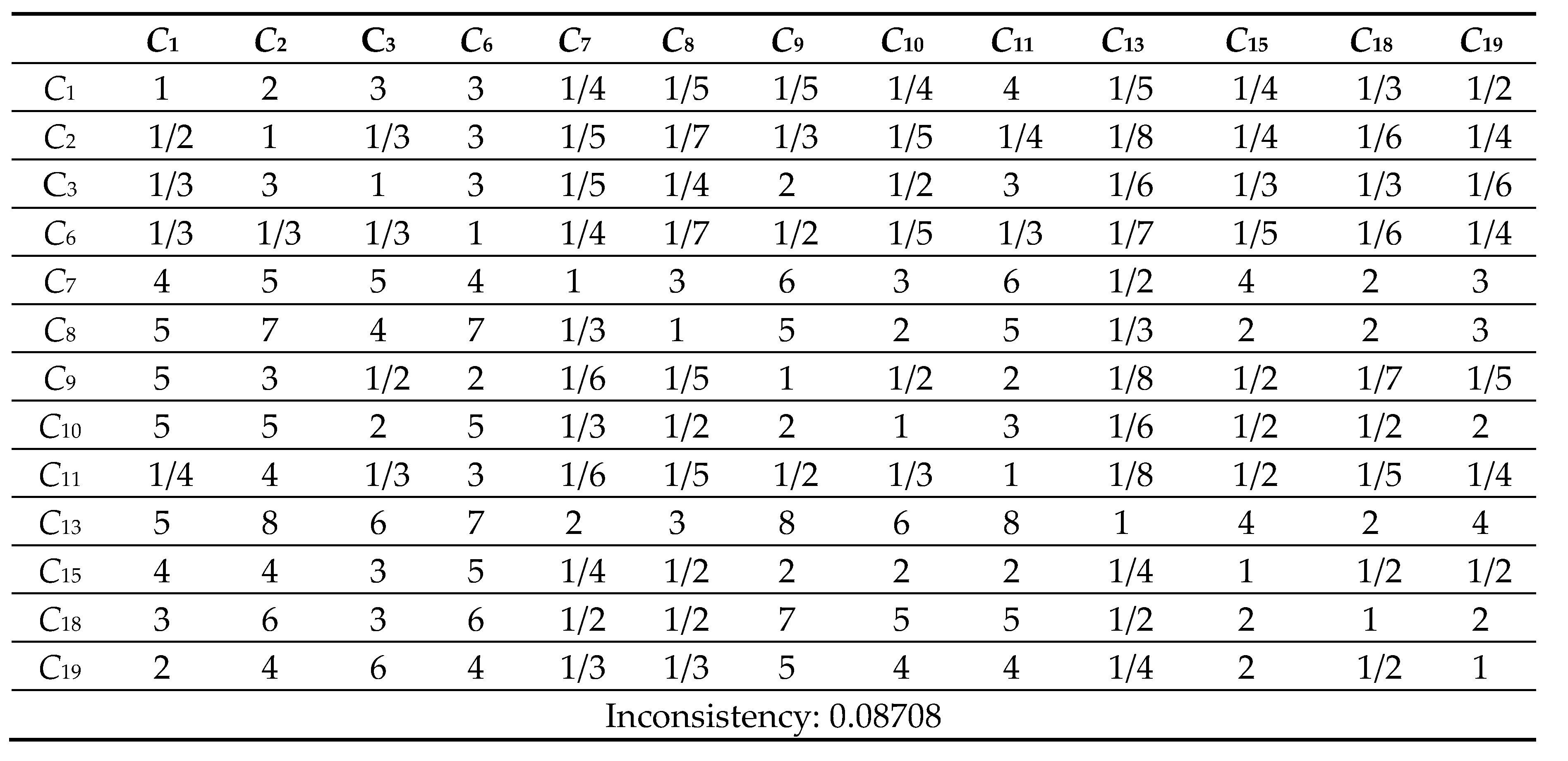

ANP

Next, the present work applied the ANP method to produce the weights of the criteria. The generalized ANP process from previous studies is summarized as follows [27,68,69]. In this work, a set of importance scales [

13] is adopted to weight each criterion using linguistic values, including 1 –

Identically Important (II), 3 –

Moderately Important (MI), 5 –

Highly Important (HI), 7 –

Very Highly Importance (VHI), 9 – Extremely Important (EI), and 2, 4, 6, 8 are the median values. Reciprocal values are used for inverse comparison.

Step 1. Obtaining Pairwise Comparison Matrix (PCM). Assume that

h experts in a decision group

are responsible for evaluating criteria

that are screened through the previous step. The PCM is generated by comparing the

ith row with the

jth column. The weights of components are formed as shown in matrix

A. The diagonal components having identical importance are illustrated by 1.

As there are several DMs, the pairwise comparison values from different DMs may vary. Experts can decide together or each assessment can be integrated into a PCM by the geometric mean

GM as in Eq. (24).

Step 2. Computing eigenvectors and unweighted supermatrix. In this step, eigenvector

Ei is obtained through Eq. (25), which is computed by each row’s average.

Then, the eigenvectors of each matrix are consolidated to form the unweighted matrix.

Step 3. Examining the consistency. In order to guarantee consistency among the judgments of the DMs, it is necessary to test the consistency by three metrics, including Consistency Measure (CM), Consistency Index (CI), and Consistency Ratio (CR).

The general form for

CM values is obtained through Eq. (26).

where aj is the corresponding row of the comparison matrix, E is Eigenvector and Ej represents the corresponding component in E.

Then,

λmax is obtained by the average of the

CM vector. The

CI is calculated as shown in Eq. (27).

Next, a random index, as listed in

Table 1 [

13], is computed following the order of the PCM. Consequently, the consistency ratio

CR is obtained by Eq. (28).

The value of CR ≤ 0.1 is in the satisfactory range; otherwise, the pairwise comparison is required to be revised.

Step 4. Obtain the weighted supermatrix. A weighted supermatrix is obtained to evaluate the relation between criteria. Then, the unweighted matrix is converted into a weighted supermatrix to make the sum of each column be 1, called column stochastic.

Step 5. Determining stable weights by obtaining limit supermatrix. The values produced from the previous step are elevated to the power of 2k until the values are firmly established, where k is an arbitrarily large number. The final priorities can be determined by using the normalization function on each block of the limit matrix. The most significant value represents the most critical criterion among other criteria. The stable weights w constructed from this step are utilized in the following steps.

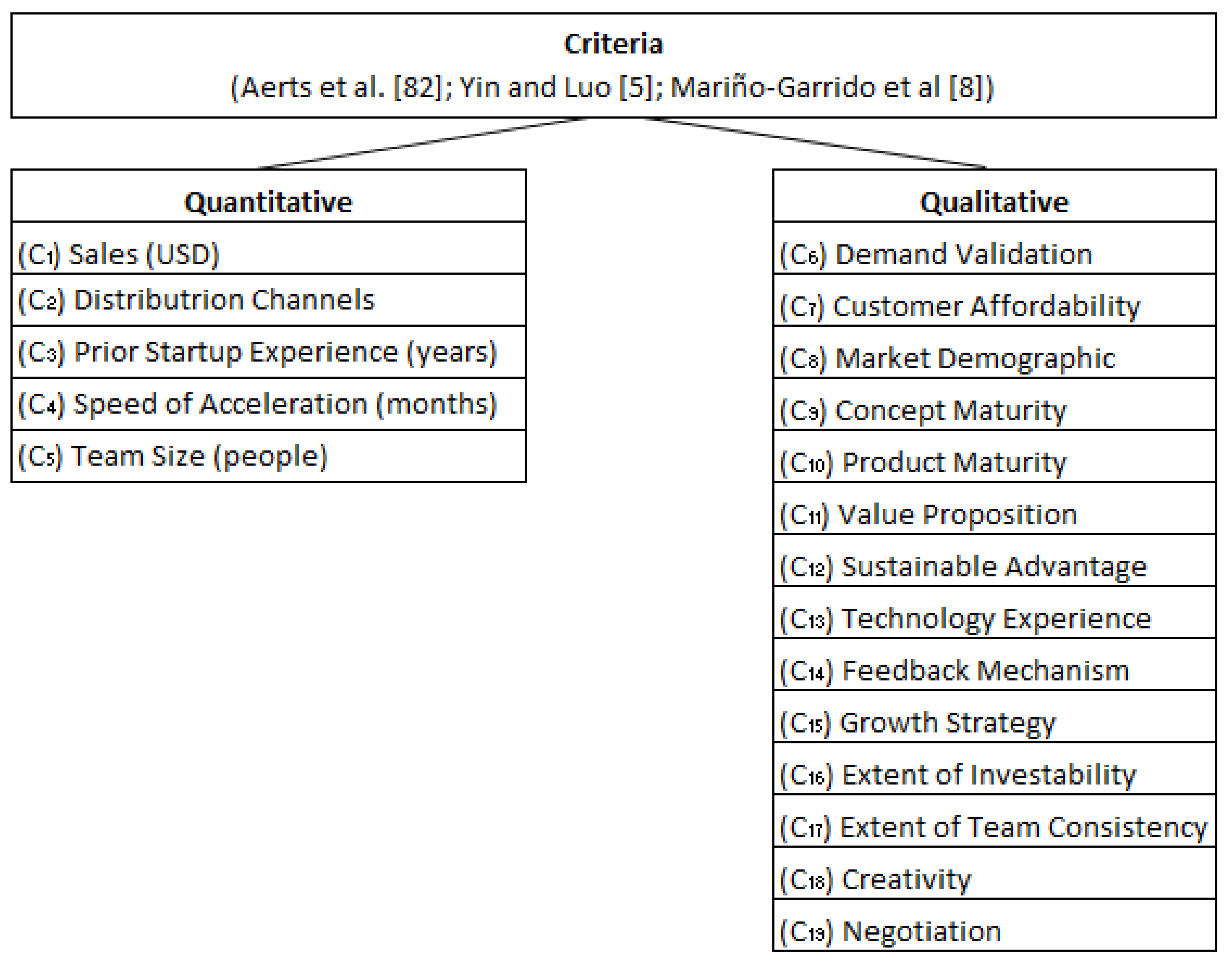

Fuzzy PROMETHEE-based ranking method

The same group of

h experts

will assess

n alternatives

under

m criteria

that are screened through the previous steps. Let

be the rating assigned to an alternative

under the criterion

by a decision-maker

. Criteria chosen from the earlier steps are first categorized into the cost-benefit framework as qualitative benefit criteria,

quantitative benefit criteria,

cost qualitative criteria,

and cost quantitative criteria

The fuzzy PROMETHEE II process is summarized as follows [

70,

71].

Step 1. Constructing the fuzzy decision matrix. Aggregated rating

is:

where

,

,

.

Step 2. Computing the normalized matrix. The normalization is completed using the Chu and Nguyen [

61] approach. The ranges of normalized TFNs belong to [0,1]. Suppose

is the value of an alternative

versus a benefit (B) criterion or a cost (C) criterion. The normalized value

lij can be as

where

.

Step 3. Calculating the evaluative differences. Pairwise comparison is made by calculating the evaluative differences of

ith alternative with respect to other alternatives. The intensity of the fuzzy preference

of an alternative

Ai over

Ai’ is obtained by Eqs. (32)-(33), based on Eq. (3)

where

Pj is the fuzzy preference function for the

jth criterion and

Cj(

Ai) is the evaluation of alternative A

icorresponding to criterion

Cj.

Step 4. Determining the preference function. To avoid the complexity and be more in a practicable form, the simplified fuzzy preference function is applied in this study as in Eqs. (34) - (35).

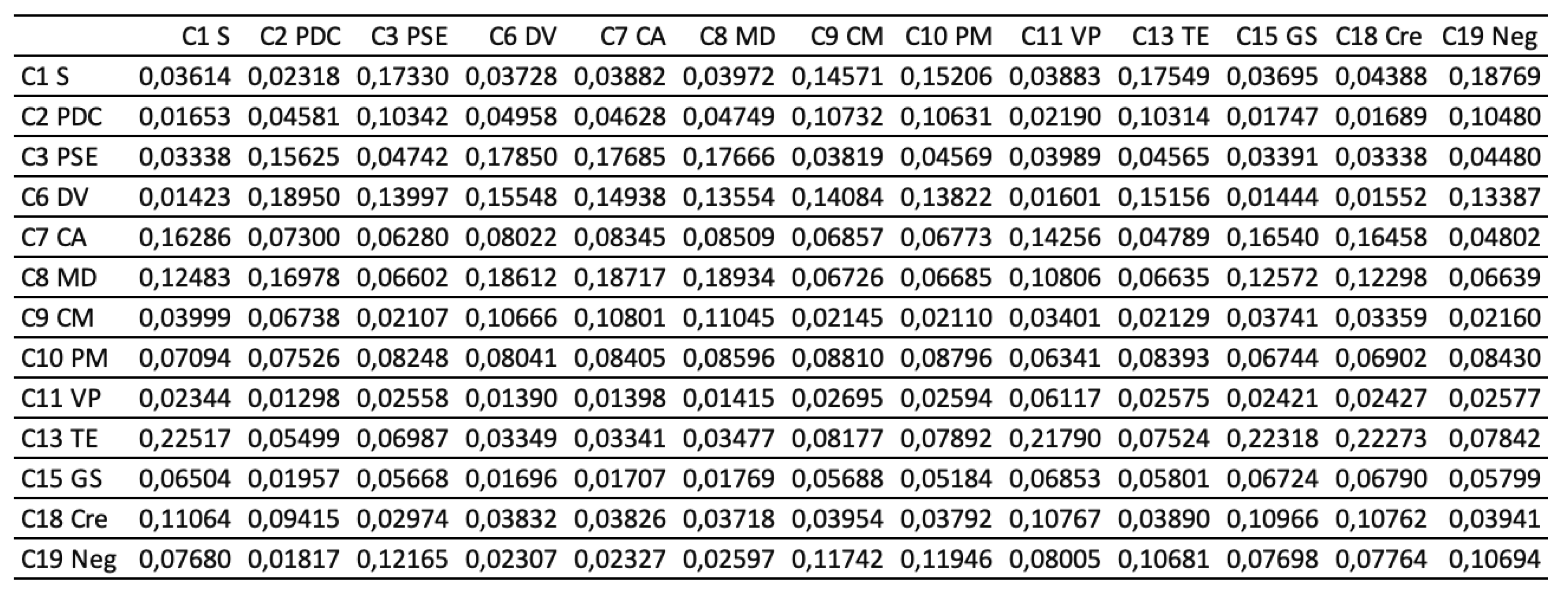

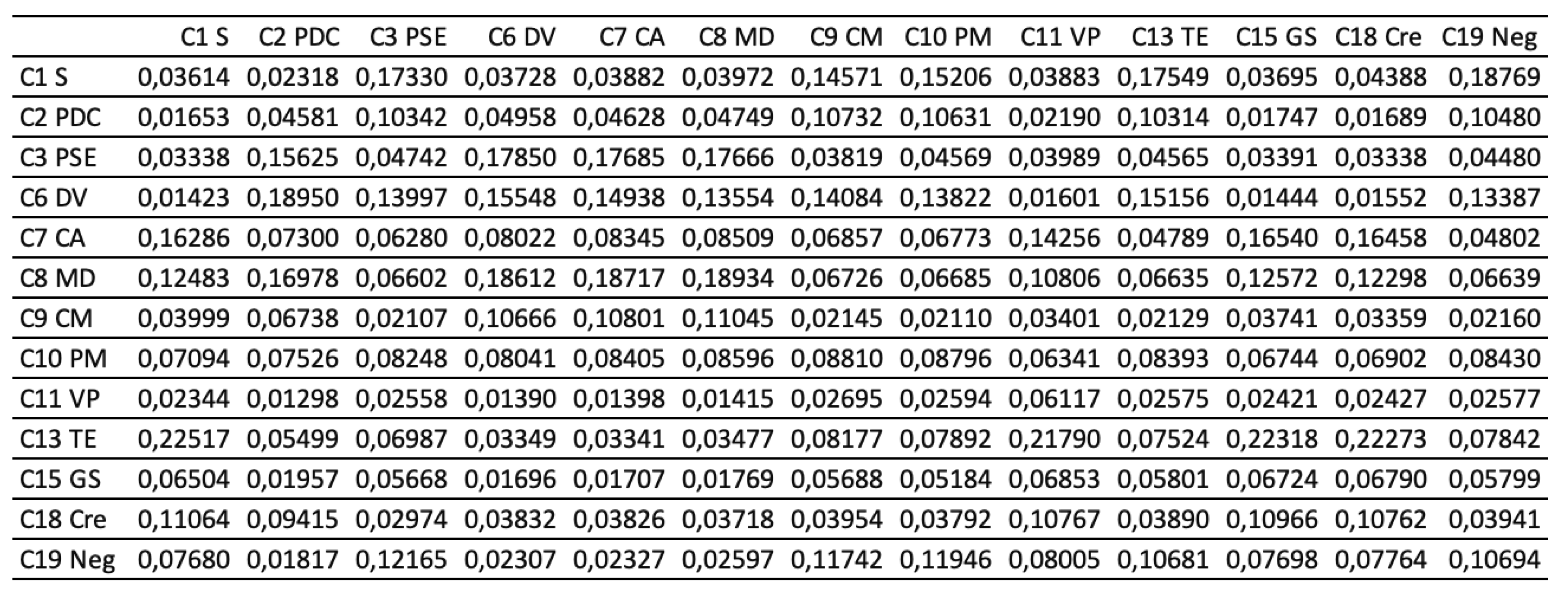

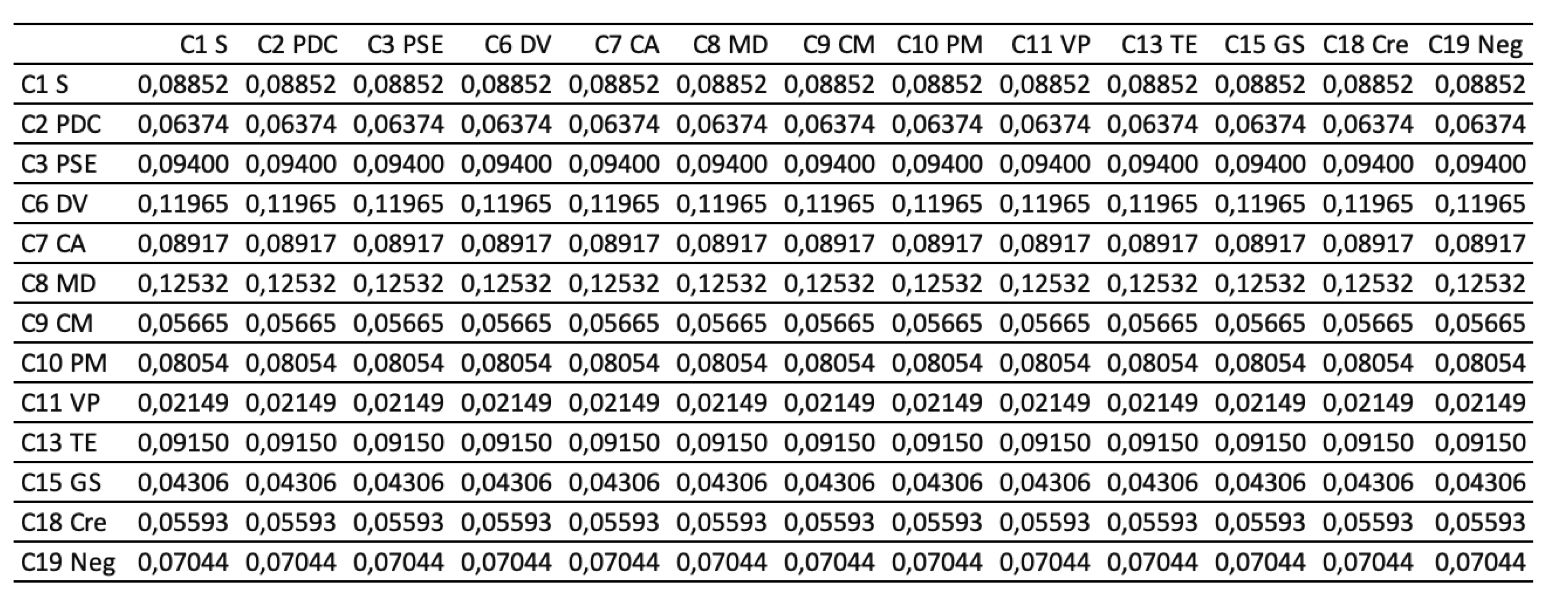

Step 5. Reckoning the aggregated fuzzy preference function. Calculate the aggregated fuzzy preference function considering the criteria weights computed from the ANP method.

The higheris, the stronger preference for the ith alternative will be.

Step 6. Determining the fuzzy leaving flowand the fuzzy entering flow

The fuzzy leaving flow of

Ai is determined as

The fuzzy entering flow of

Ai is determined as

Step 7. Calculating the fuzzy net outranking flow for each alternative

Step 8. Defuzzifying the fuzzy net outranking flow value and obtaining the ranking of alternatives. In this step, the spread area-based RMMS model is proposed to apply to assist defuzzification and obtain the final ranking using Eqs. (12)-(20). An FN is more prominent if its value is more significant.

under

13 criteria that are screened during the previous steps. The ratings of the

alternatives over qualitative criteria and quantitative criteria are shown in

Table 15 and Table 17

(see

Appendix V

II and

Appendix V

III, respectively,

for details). Subsequently, the mean ratings are calculated using Eq. (29), as

shown in

Table 16

, and the alternatives’ normalized gradings versus quantitative criteria

are produced using Eqs. (30) and (31), as shown in

Table 18

. The confidence

level ratings on alternatives are also collected to produce µ value, as

shown in

Table 19

.

under

13 criteria that are screened during the previous steps. The ratings of the

alternatives over qualitative criteria and quantitative criteria are shown in

Table 15 and Table 17

(see

Appendix V

II and

Appendix V

III, respectively,

for details). Subsequently, the mean ratings are calculated using Eq. (29), as

shown in

Table 16

, and the alternatives’ normalized gradings versus quantitative criteria

are produced using Eqs. (30) and (31), as shown in

Table 18

. The confidence

level ratings on alternatives are also collected to produce µ value, as

shown in

Table 19

.