1. Introduction

In light of the recent energy crisis, in the midst of the energy transition towards carbon free power systems, the advantages of renewable energy sources (RESs), such as photovoltaic (PV) generators whose growth has been exponential over the last twenty years [

1], position them in the center of related policies. However, they suffer from variability and stochasticity of the output power which is their main drawback [

2] and a challenge attracting the interest of research community. A promising approach towards a more flexible use of PV sources is their combination with battery energy storage systems (BESSs) to fully exploit the potential of PV units integrated into distribution networks (DNs) [

3].

In the last few years, a number of authors have addressed the issues of the optimal power dispatch in DNs with integrated BESSs. These studies have been focused on several main aspects such as: modeling BESSs, defining the BESS function in DNs, i.e. objective functions of the optimization problem, defining control variables, dependent variables and technical constraints, as well as the choice of solution methods.

The BESS is a combination of a voltage source converter and a battery pack, such that the active and reactive power can be controlled independently [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. In most research articles, BESS are modeled as a set of equations defining that the stored energy at any given time segment is a function of the stored energy, and charge/discharge power at the previous time segment. Internal losses of BESS are accounted for through the charge/discharge efficiency coefficients or functions. The limits of the reactive power output to be provided by the BESS are also defined in these models.

Depending on the function that the BESS performs in the DN, the objectives for the optimal power dispatch can be summarized in three groups: technical objectives, financial objectives, and multi-objectives. Financial objectives can be related to the maximization of revenues of a RES-BESS based hybrid power plant [

10], the reduction in the energy cost from the source grid [

11,

12], as well as the minimization of distributed generators dispatch costs [

13], power generation costs and load shedding costs [

5]. Technical objectives are the base objectives and include the static voltage stability improvement [

6], the transient voltage stability enhancement [

8], the energy loss minimization [

9], the voltage fluctuation mitigation [

14], and minimization of the voltage deviations at load buses [

15]. Researchers often adopt multi-objective functions with different combinations of financial and technical objectives, such as the simultaneous maximization of the total yield from the RES and minimization of the total costs of the energy loss in DNs [

4], the simultaneous minimization of the power exchange cost between the DN and transmission network and the penalty cost of the voltage deviation in the DN [

7].

In its most general mathematical formulation, the optimal power dispatch in DNs with integrated RES and BESS is a non-linear, non-convex, large-scale, dynamic optimization problem with constraints. There are two approaches to solving it, namely classical optimization methods and metaheuristic methods.

The non-linear optimization models are implemented in the GAMS environment and solved using CONOPT3 solver [

4], CPLEX solver [

5], and KNITRO solver [

11]. The big

M method is used in [

7] to transform the model into a mixed-integer linear programming problem and solved using a commercial software. The interior-point solver

fmincon in MATLAB [

9] and the simplex solver through

docplex python library [

10] are also suggested for the optimal power flow in DNs with the BESS, whereas Giuntoli et al. [

13] used the CaADdi framework for interfacing with the IPOPT solver for nonlinear programming. In recent research, some population-based methods, such as PSO, have been proposed to find the optimal power dispatch solution in the DN with the BESS [

6,

15].

This paper is an expanded and significantly modified version of [

12]. The focus of this study is unbalanced DNs with single-phase PV generation and BESS. The main contributions of this study are as follows:

A dynamic model of the optimal active power dispatch (OAPD) in unbalanced DNs with single-phase PV and BESS is proposed to minimize energy costs from the source network.

The optimal reactive power dispatch (ORPD) in unbalanced DNs with single-phase PV and BESS is considered. The objective functions are minimization of energy losses and voltage unbalance at three-phase load buses, and control variables are reactive powers of solar PV inverters and BESS.

A scenario based approach encompassing the MSC method and the simultaneous backward reduction technique is proposed for modeling the uncertainty of PV generation and load in the DN.

Application of a novel hybrid PSOS-CGSA algorithm to solve the optimal active-reactive power dispatch problems is presented.

Defining a modified IEEE 13-bus feeder for evaluating the solvability and applicability of the proposed approach is suggested.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, a scenario-based model is formulated for the optimal dispatching of active power in DN by operating mode control of BESSs. The problem of optimal reactive power dispatch in unbalanced DNs with single-phase PV and BESS inverters is elaborated in

Section 3. The solution method based on the hybrid PSOS-CGSA metaheuristic algorithm is briefly presented in

Section 4. The simulation results are discussed in

Section 5, whereas the main conclusions are listed in

Section 6.

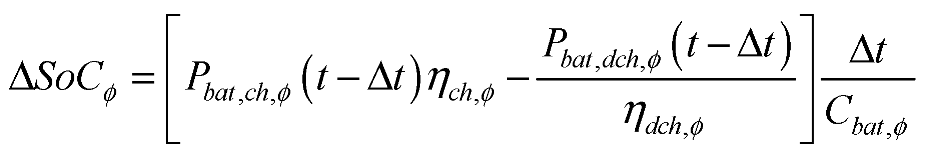

2. Active Power Dispatch by BESS

Battery operation mode is determined by two basic parameters. These are charge/discharge power and state of charge (

SoC). Since the battery capacity is limited, the

SoC of the battery must be viewed as a dynamic quantity, as follows [

10]:

where

is the total capacity of the battery;

and

are charging and discharging power of the battery, respectively;

and

are charging and discharging efficiency, respectively; Δ

t is the time segment (for example 1 h), and

ϕ denotes the phase,

ϕ(

a,b,c).

Battery power and

SoC must always be within defined limits, as follows:

where

and

are maximum charging and discharging powers of the battery, respectively;

and

are the predefined minimum and maximum charge levels, respectively;

T is a time horizon, e.g. 24 h.

Battery charge/discharge power (

) and

SoC are mutually dependent variables. Taking into account the variability of the electricity price, their relationship can be expressed as follows [

12]:

where

is the day-ahead electricity price from the source grid at time

t,

is the average electricity price during the day;

aϕ(

t) is a coefficient within the range [0, 1].

The coefficient

aϕ(

t), which defines the power of the BESS, can be determined in different ways. In [

12], the coefficient

aϕ(

t) is calculated based on the relation of the electricity price at the time

t and the mean electricity price during a day. A similar approach was adopted in [

16], where the coefficient

aϕ(

t) is calculated as a function of the difference in the electricity price from the predefined lower price limit for discharging and upper price limit for charging. However, the charging/discharging powers of the BESS determined in this way do not guarantee the optimal dispatch of the active power according to the adopted objective function. Therefore, in this paper, the coefficient

aϕ(

t) is considered as a control variable, whose value optimizes to ensure the minimization of a given objective function.

The basic equation of the active power dispatch problem is the power balance constraint (9), which must be satisfied at each time segment

t:

where

Pg,ϕ(

t) is the active power from/to the source grid at time

t in phase

ϕ;

PL,ϕ(

t) is the total active power of the load at time

t in phase

ϕ;

PPV,ϕ(

t) is the total active power generation of PV units at time

t in phase

ϕ;

Pbat,ϕ(

t) is the active power of the battery at time

t in phase

ϕ;

ϕ(

a,b,c).

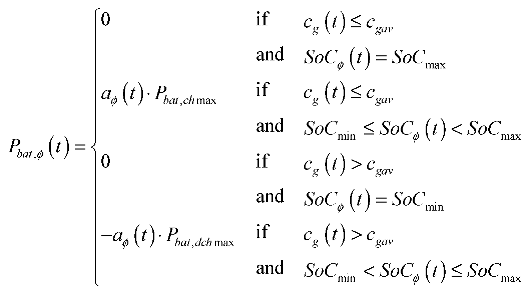

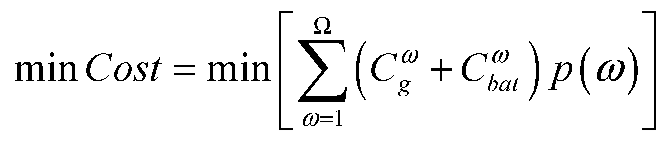

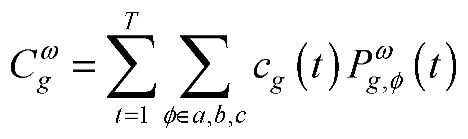

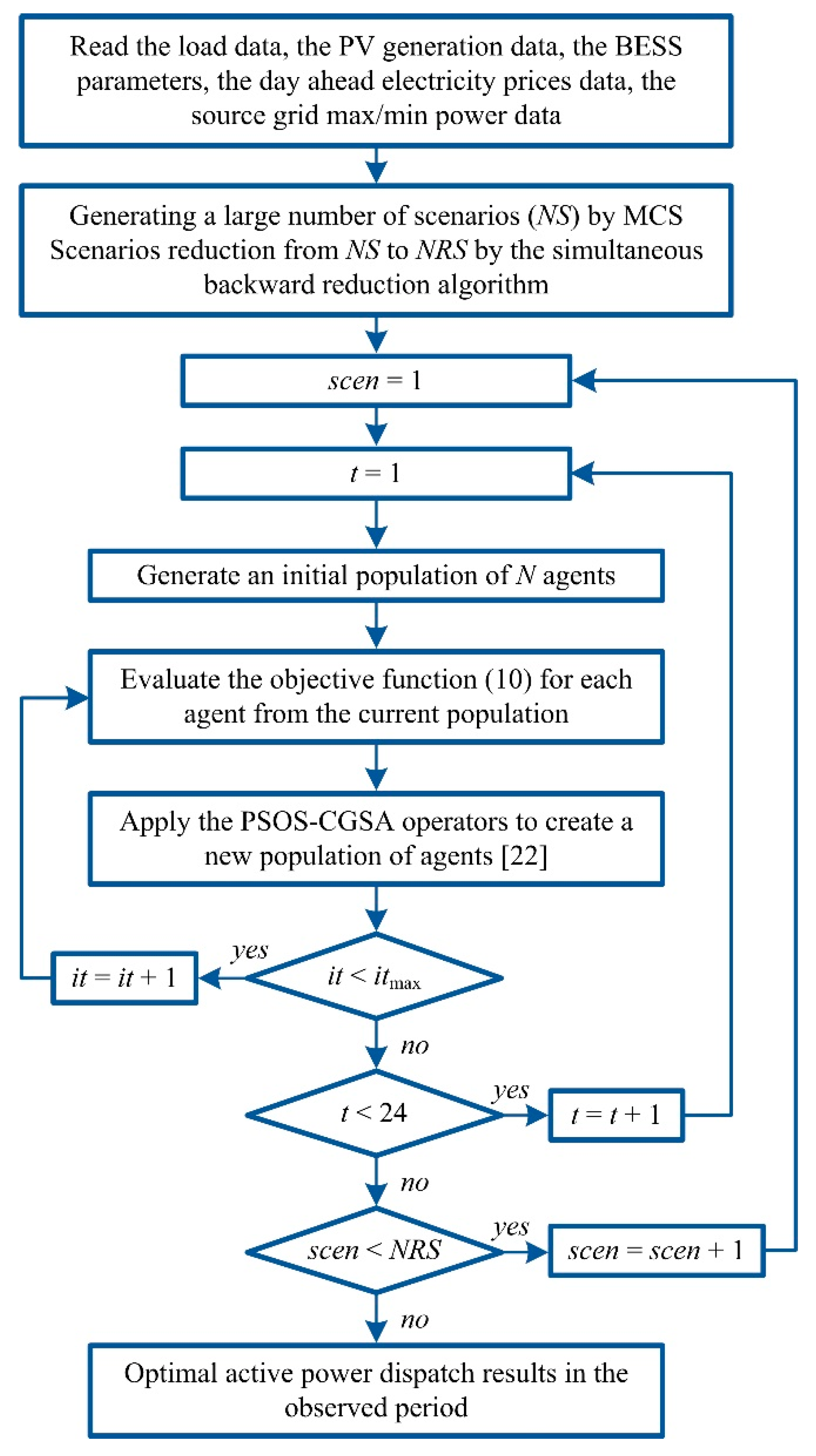

2.1. Objective Function for OAPD

By controlling the operating mode of the battery, i.e. the charging/discharging power and SoC, the active power flows in the distribution network can be significantly influenced. In this way, the exchange power with the source power grid is directly affected, as well as other parameters of the distribution networks, such as power losses, voltage profile, etc. The operating costs of the distribution network mostly depend on the value of the energy from/to the source grid. Considering various PV generation and load demand scenarios with their probabilities, the objective function for OAPD can be formulated as the minimization of the expected cost for electricity, as follows:

where ω and Ω are the current scenario and the total number of scenarios, respectively; p(ω) is the probability of scenario ω; and are the total cost for electricity from the source grid and operating cost of the battery in scenario ω, respectively; cg and are the electricity price from the source grid and the unit operating cost of the battery, and T is the considered period (i.e. 24 h).

Two assumptions should be kept in mind here, namely:

The retail electricity prices have the same daily profile as the wholesale electricity prices and fluctuate hourly.

The DN transacts with the wholesale markets through some energy agent such as an aggregator.

The power output of a PV source is determined by the solar irradiation at a given moment, and its value cannot be influenced. Therefore, the cost of the PV generation is not taken into account in the objective function (10), because it cannot be optimized with controlling the charge/discharge power of the battery.

For stable operation, constraints (3-7) and (9) must be satisfied. The output power of the PV generator is limited by the maximum output power, i.e. the nominal power. Also, Pg,ϕ(t) must be restricted by minimum and maximum values.

2.2. Modeling of Uncertainties

2.2.1. PV Generation Modeling

The power of the PV source as a function of solar irradiance can be expressed as follows [

16]:

where

Ppvn is the nominal power of the PV source;

S is the solar irradiance on the PV module surface;

Sstc is the solar irradiance under standard test conditions;

Rc is a certain irradiance point.

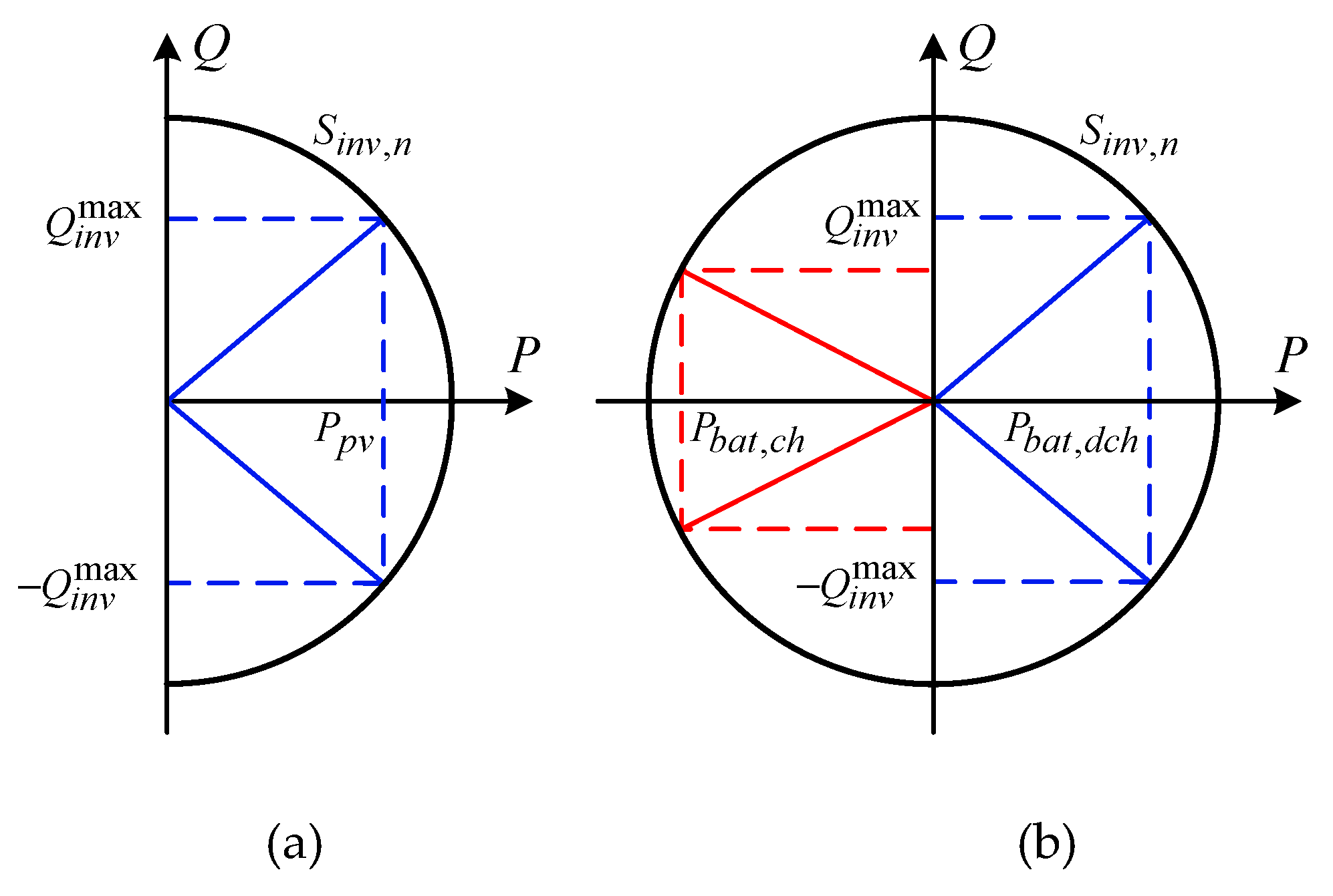

To model the stochastic nature of the solar irradiance, it is most convenient to use the Beta probability density function (PDF):

where

fb(

S) is the Beta function of the solar irradiance

S;

α, β are the shape parameters of the Beta distribution; and Γ is the Gamma function.

Based on the data of the long-term measurement of the solar irradiance in a given area, characteristic daily diagrams of the solar radiation can be estimated, with statistical indicators, i.e. mean value (

µS) and standard deviation of the solar irradiance (

σS) in a given time interval

t (e.g. an hour). Using mean value and standard deviation of the solar irradiance, the shape parameters of the Beta PDF can be calculated for a time interval

t, as follows:

2.2.2. Load Modeling

The normal (Gaussian) probability function is most commonly used to model load uncertainty in distribution systems. Generally, the load level is assumed to be a random variable (

L) following the same PDF within each hour of a given daily load diagram [

2].

where

μL and

σL are the mean value and standard deviation of

L, respectively;

r is a random number in [0, 1]; and erf(·) and erf

-1(·) are the error function and the inverse error function, respectively.

2.2.3. Scenario Generation

The Monte Carlo simulation (MCS) method is suitable to modeling the uncertainties of solar irradiance and load level. Starting from probability density functions for solar irradiance and load, whose parameters are determined based on historical data, eg previous years, the MSC method can generate a large number of scenarios for day-ahead profiles of solar irradiance and load levels. Although a larger number of scenarios (e.g. several thousand) provides a more faithful modeling of the uncertainty of the output power of the PV source and the load level, on the other hand, it means a higher computation burden. In distribution network operation control applications, such as optimal power flow, methods with high accuracy and low computational burden are needed.

As a compromise between a good approximation (modeling) of the uncertainty of stochastic input variables (solar irradiance and load) on the one hand, and a significant reduction in calculation time on the other hand, a scenario reduction strategy aggregating similar scenarios can be applied. In doing so, it must be ensured that the metric of probability distribution of the reduced set must be close enough to the original set of scenarios. There are several algorithms for reducing the number of scenarios, such as k-means clustering, backward reduction, and fast forward selection. In this work, the simultaneous backward reduction algorithm [

17,

18,

19] was employed to reduce a ternary scenario tree for the daily PV generations and load profiles.

5. Simulation Results

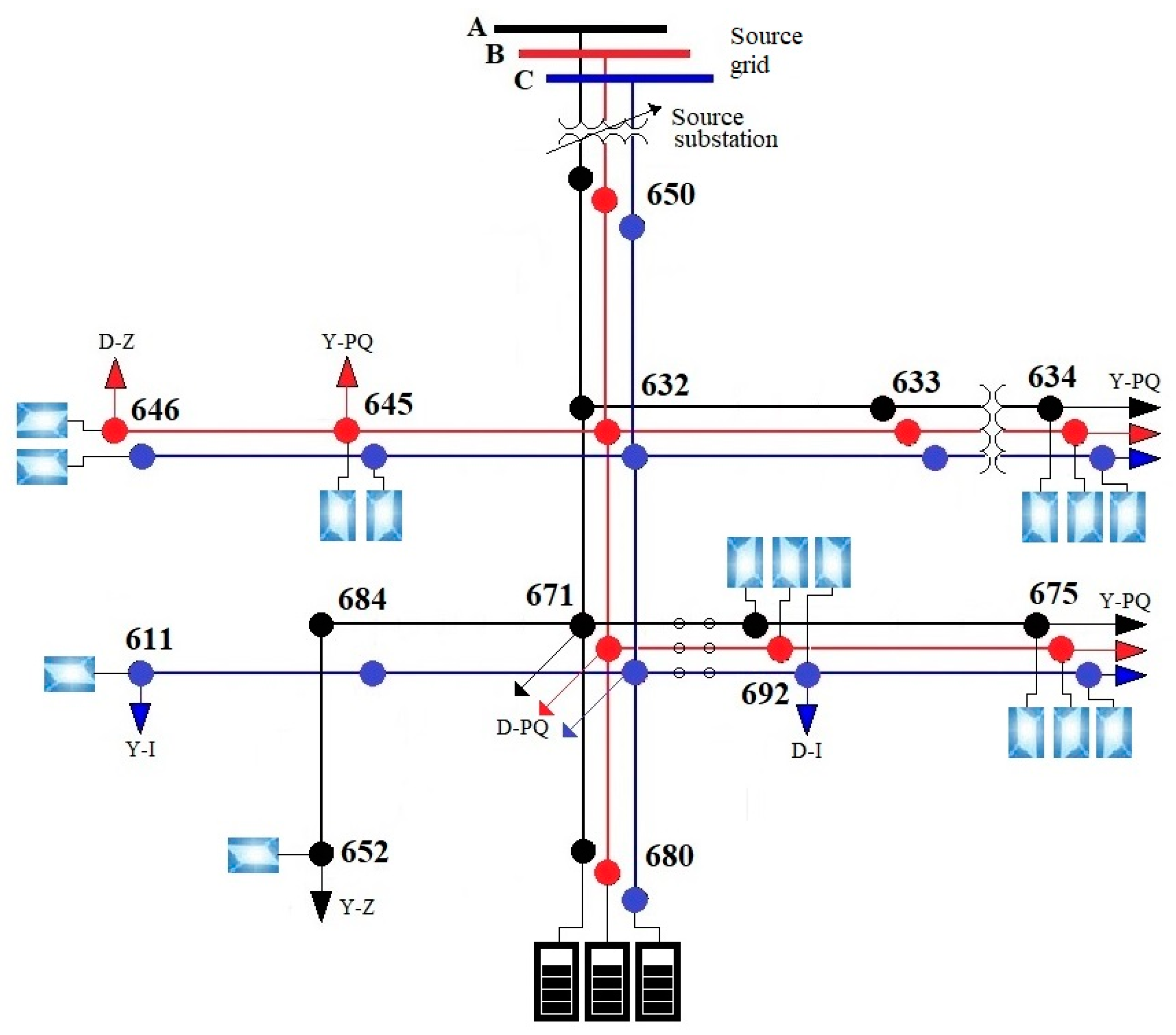

The proposed approach for the day-ahead optimal dispatching of active and reactive powers was simulated on a modified IEEE 13-bus feeder [

27]. In the modified IEEE 13-bus feeder, the single-phase PV sources are connected to buses 634, 645, 646, 611, 675, 692 and 652, as shown in

Figure 4. Single-phase PV sources, each with the same rated power of 250 kW, are connected to the grid via single-phase inverters. Single-phase BESSs, each with a rated power of 0.9 MW and a capacity of 3.6 MWh are connected at bus 680 in all three phases via single-phase converters rated apparent power 1.1 of the rated power of the batteries. Data on PV and BESS parameters are given in

Table 1 and

Table 2, respectively.

The daily load profile is assumed to be with the hourly mean values tabulated in

Table 3 with the same standard deviation of 10% of the corresponding mean values. The simulation was performed for the daily solar irradiance profile with the hourly mean value and standard deviation as given in

Table 4. The day-ahead electricity price (EP) data are adopted as in

Table 5. The maximum value is estimated according to the electricity price for Serbia on the spot market in January-February, 2023.

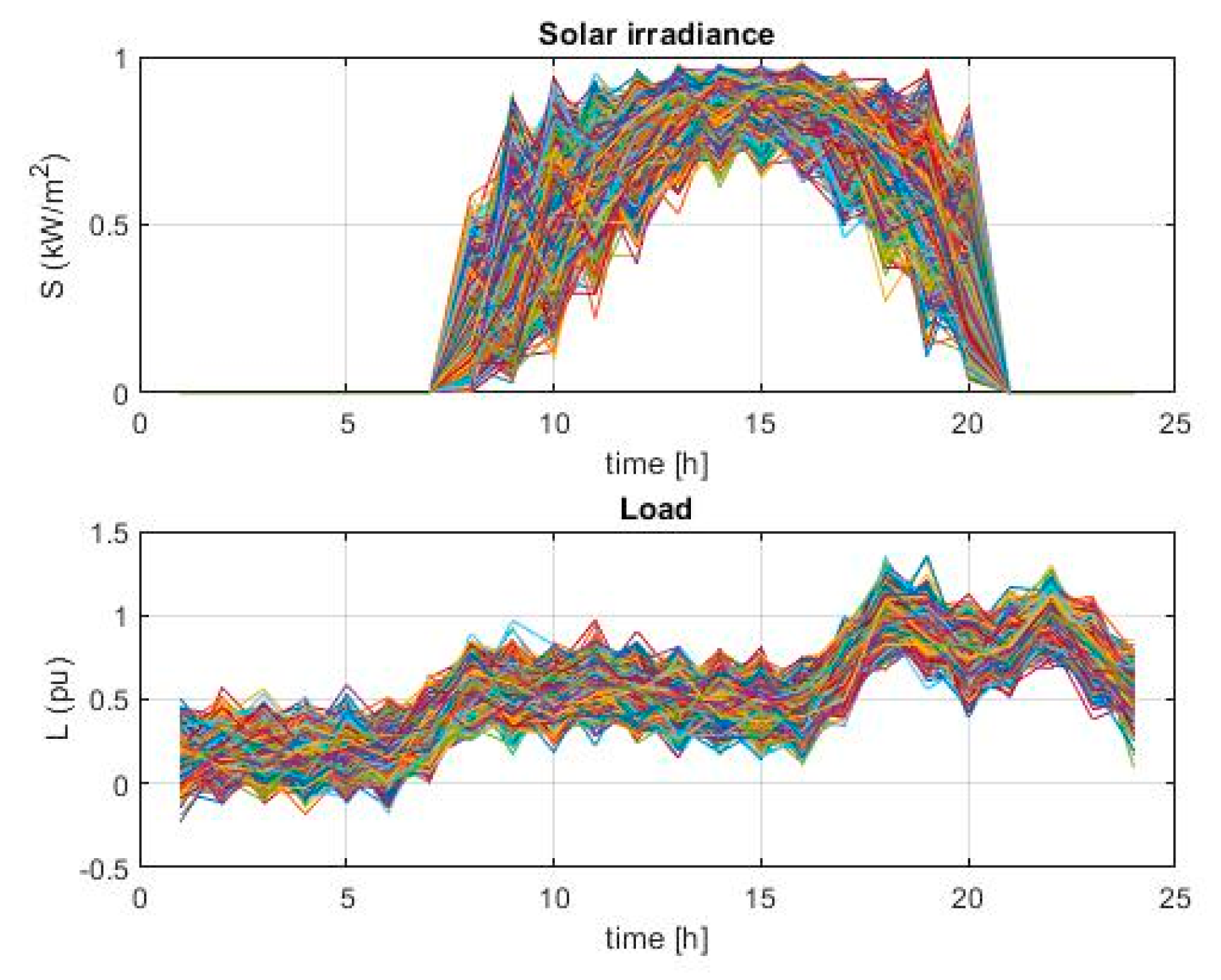

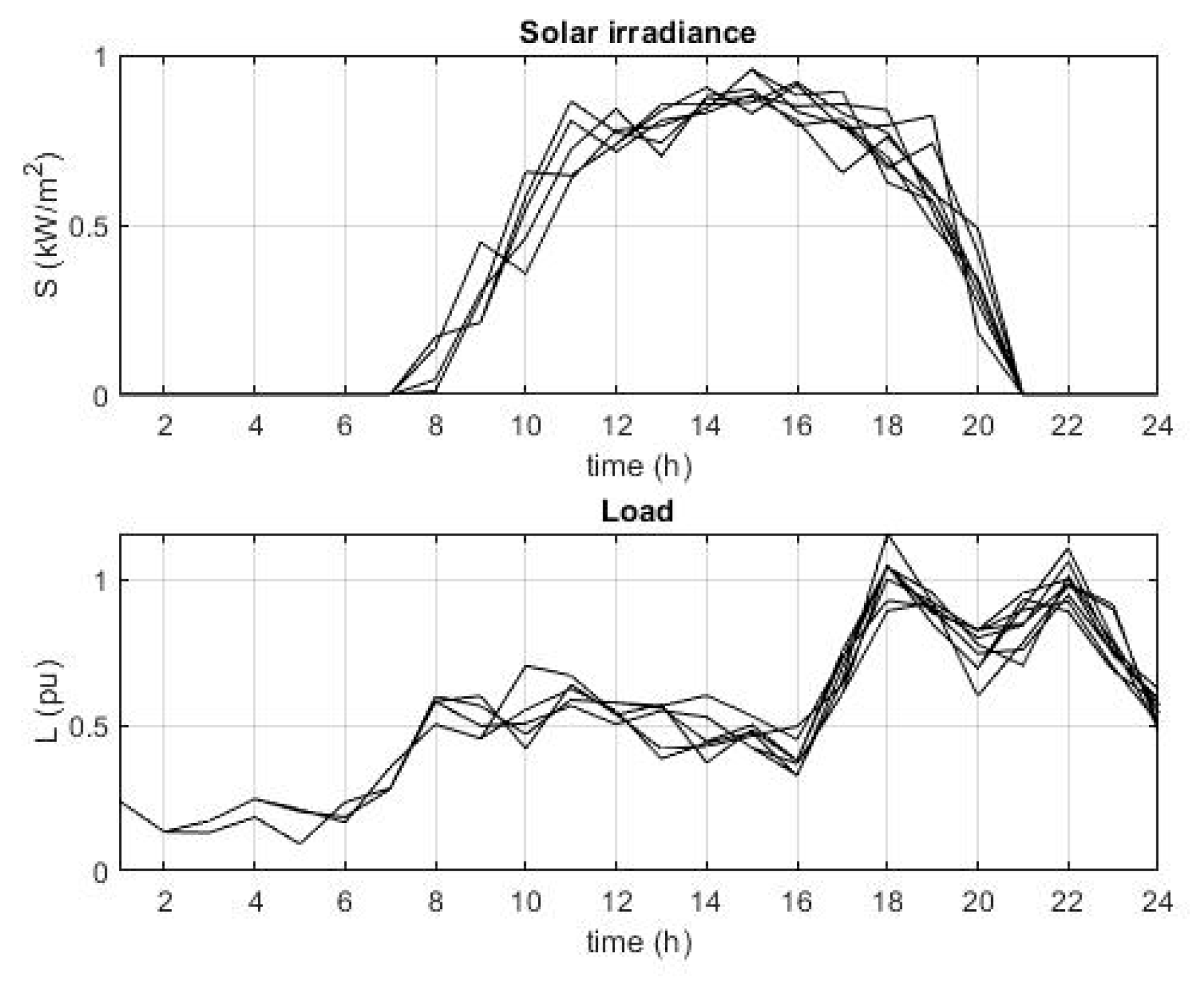

5.1. OAPD Results

As explained in

Section 2, using MCS, there are 2000 solar irradiace and load scenarios generated, as shown in

Figure 5. By applying the simultaneous backward reduction technique, these 2000 scenarios were reduced to 10 scenarios shown in

Figure 6.

By applying the proposed approach for the optimal active power dispatch, the expected total operating costs of each scenario were determined, and the results are shown in

Table 6.

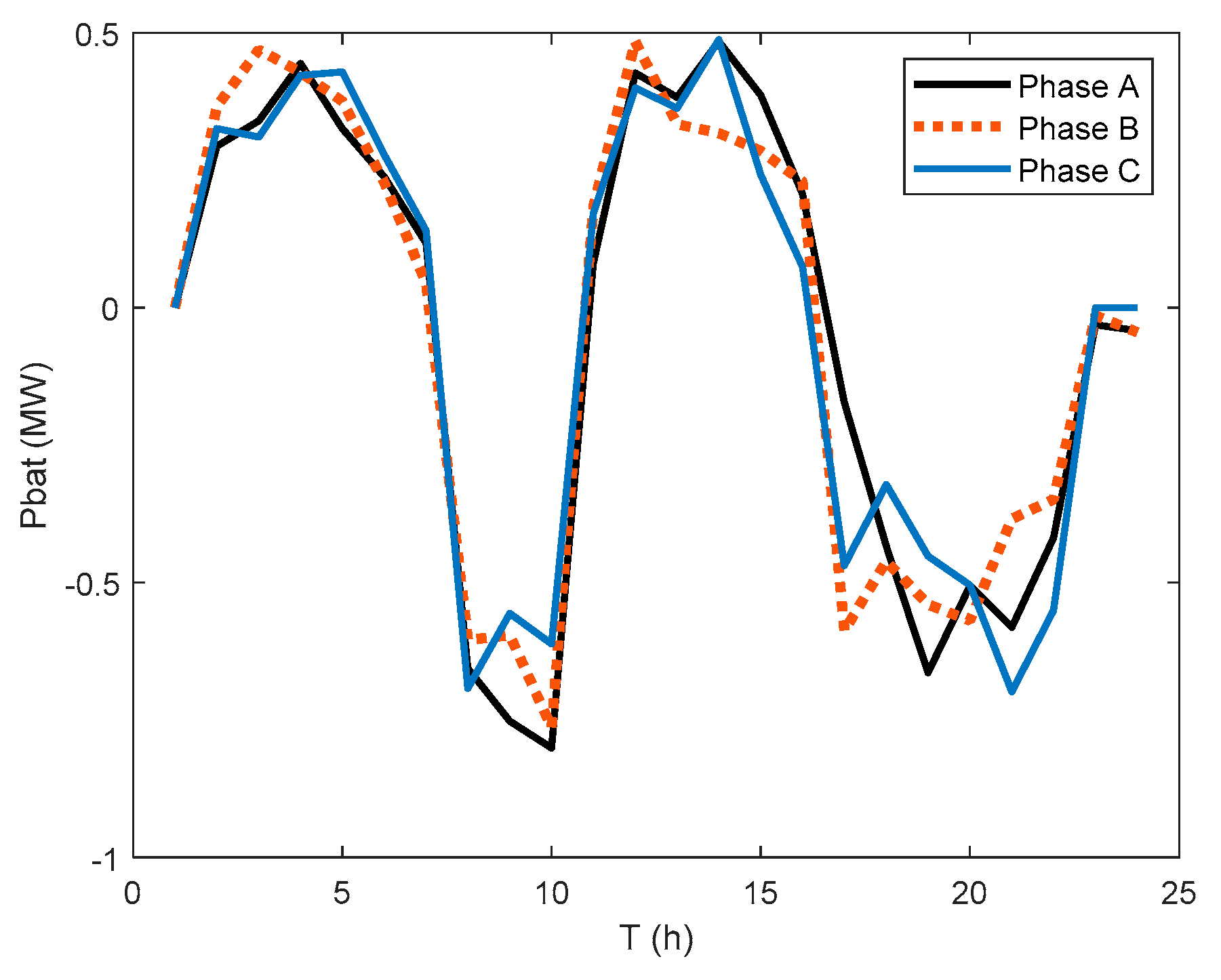

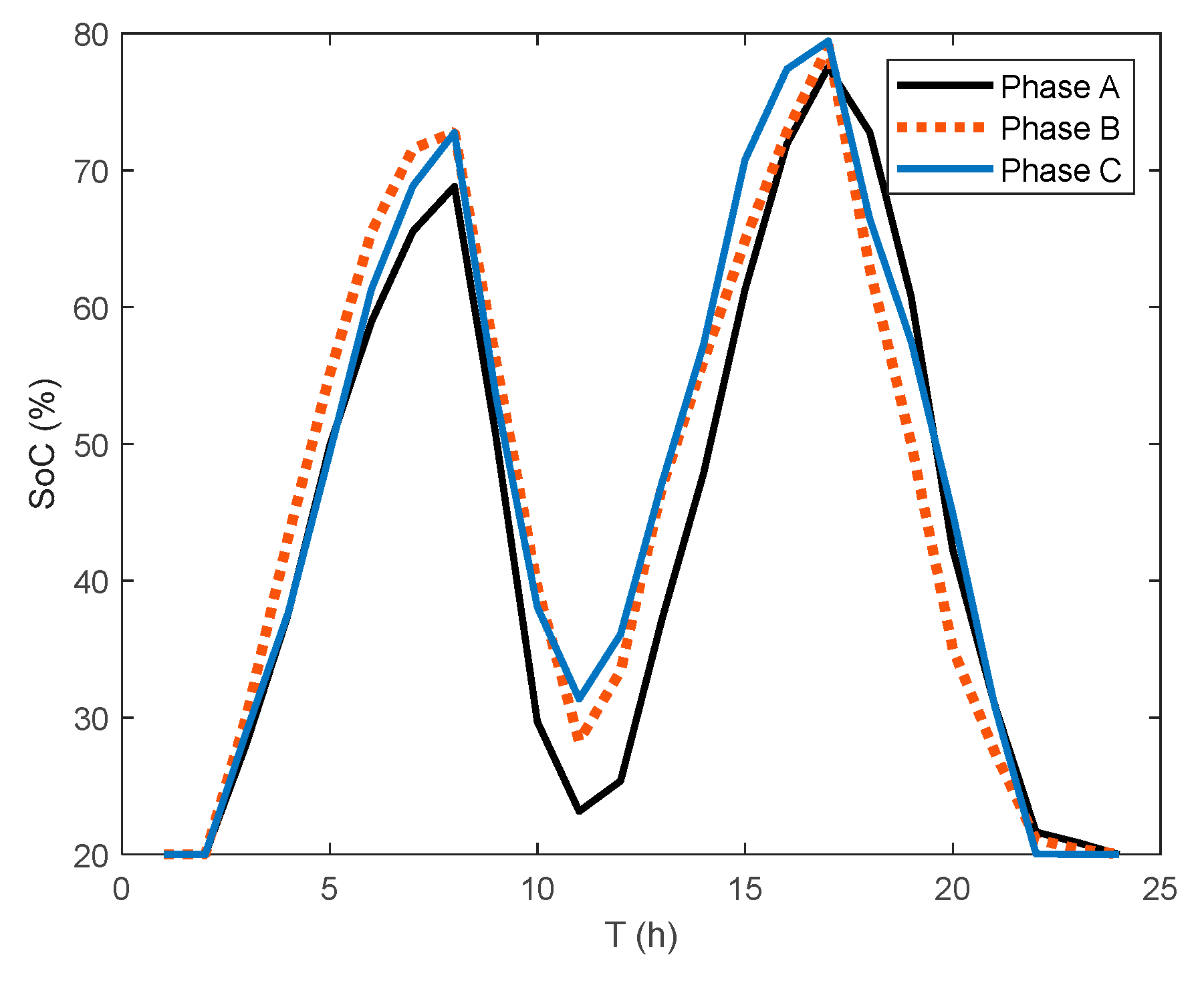

The optimal value of the expected daily cost for electricity is 453.16 (€). Acording to (10), this value is obtained as sum of the costs in each reduced scenario multiplied by the corresponding probability. In view of this, the expected day-ahead charging/discharging schedule of the BESS was obtained as shown in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

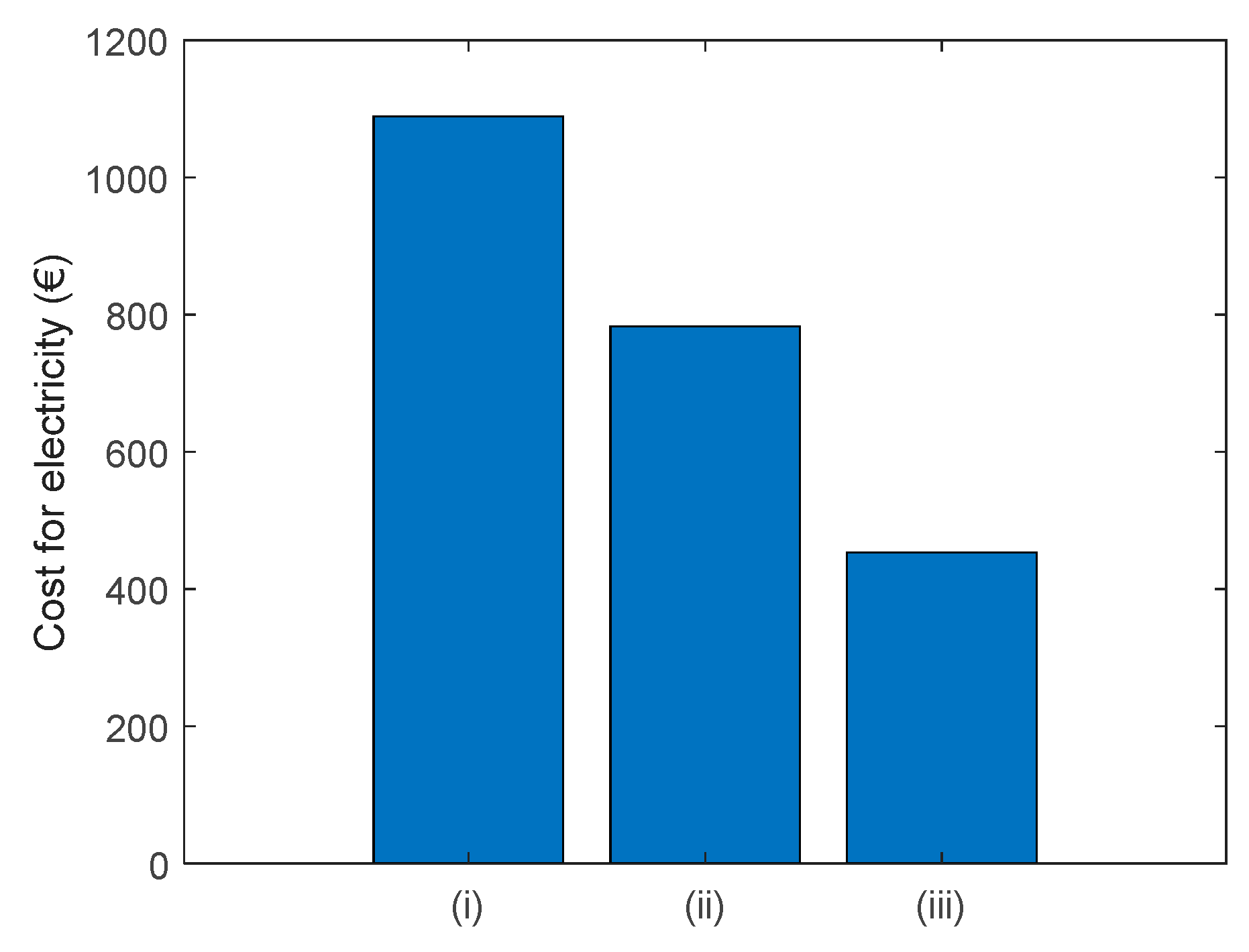

To fair comparison,

Figure 9 shows the daily costs for electricity in the following cases: (i) without the BESS integrated into the DN - base case, (ii) with the BESS in the DN applying the charge/discharge schedule approach presented in [

12], and (iii) with the BESS in the DN using the proposed OAPD algorithm. The results in

Figure 9 clearly indicate that the proposed PSOS-CGSA-based approach for OAPD leads to a large reduction in costs for electricity compared to the base case and the approach for OAPD in [

12].

5.2. ORPD Results

Here, the optimal values of 21 control variables should be determined, as follows:

The simulation studies performed for the following two test cases:

Case 1: Minimization of the active power losses (Fobj1)

Case 2: Minimization of the phase voltage unbalance rate (Fobj2)

The voltages at the load buses must be within [0.94 -1.06] (p.u.). The voltage of the root bus (V0) can be changed in the range [0.9 -1.1] (p.u.), while the limits of the reactive power of the converter are variable, according to (26).

The results are given in

Table 7 and

Table 8. In the base case, the PV sources and BESS operate with unity power factor, and the root bus voltage is equal to 1 p.u.

Table 7 and

Table 8, respectively, show the expected values of total active energy losses (W

loss) and maximum values of phase voltage unbalance rate (PVUR

max) for all ten reduced scenarios.

Applying the proposed procedure for ORPD achieves a reduction of expected energy losses by 22% compared to the base case, while the expected value of the maximum PVUR drops from 9.1% to 1.91%. There are significant energy savings, and it is ensured that the PVUR index level is below the maximum limit of 2% for all three-phase buses in the DN.

Based on the results shown in

Table 7 and

Table 8, it can be seen that in the case of the minimization of active energy losses (

Fobj1) the best scenario is 9, and in the case of the minimization of the voltage unbalance (

Fobj2) the best scenario is scenario 1.

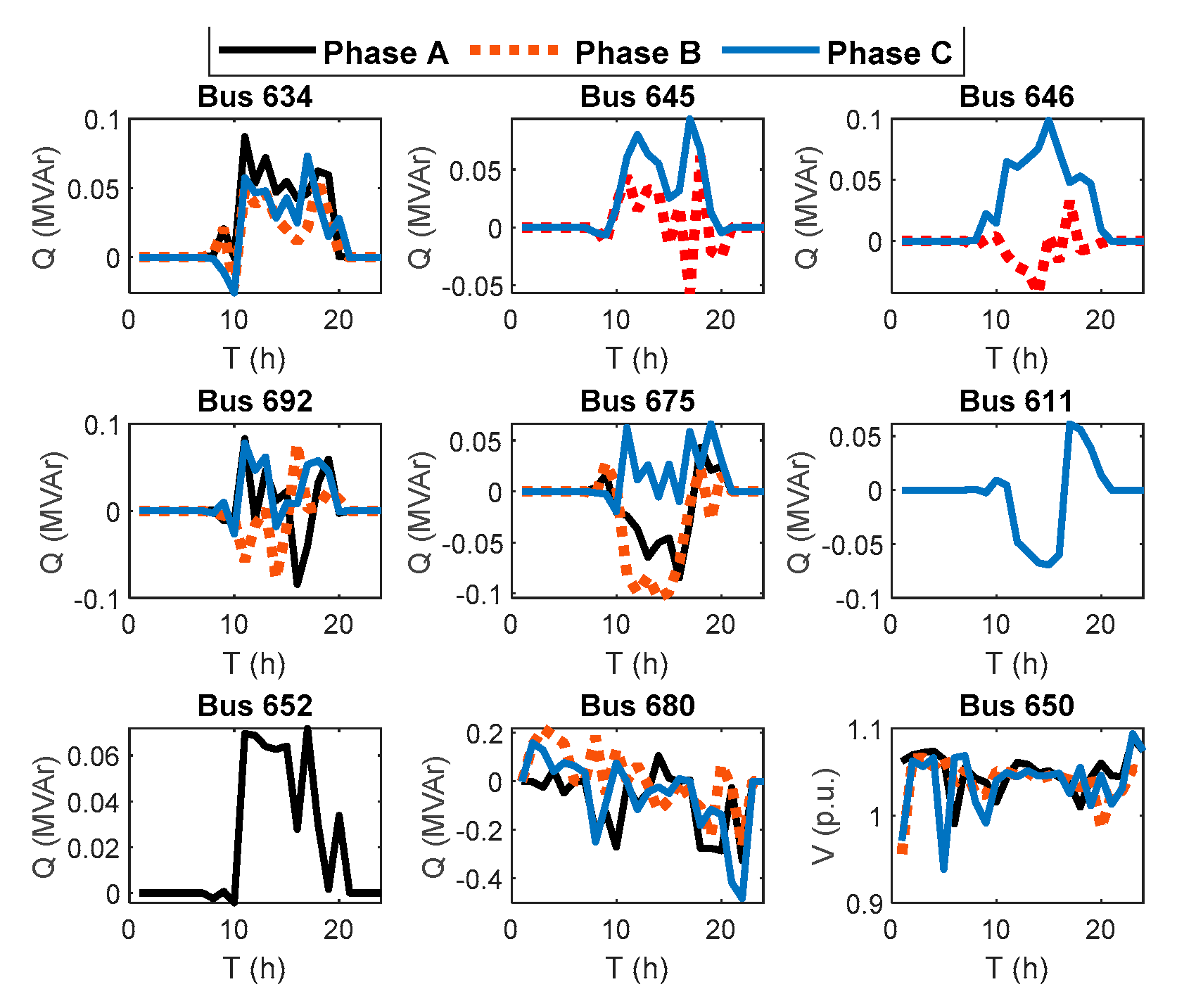

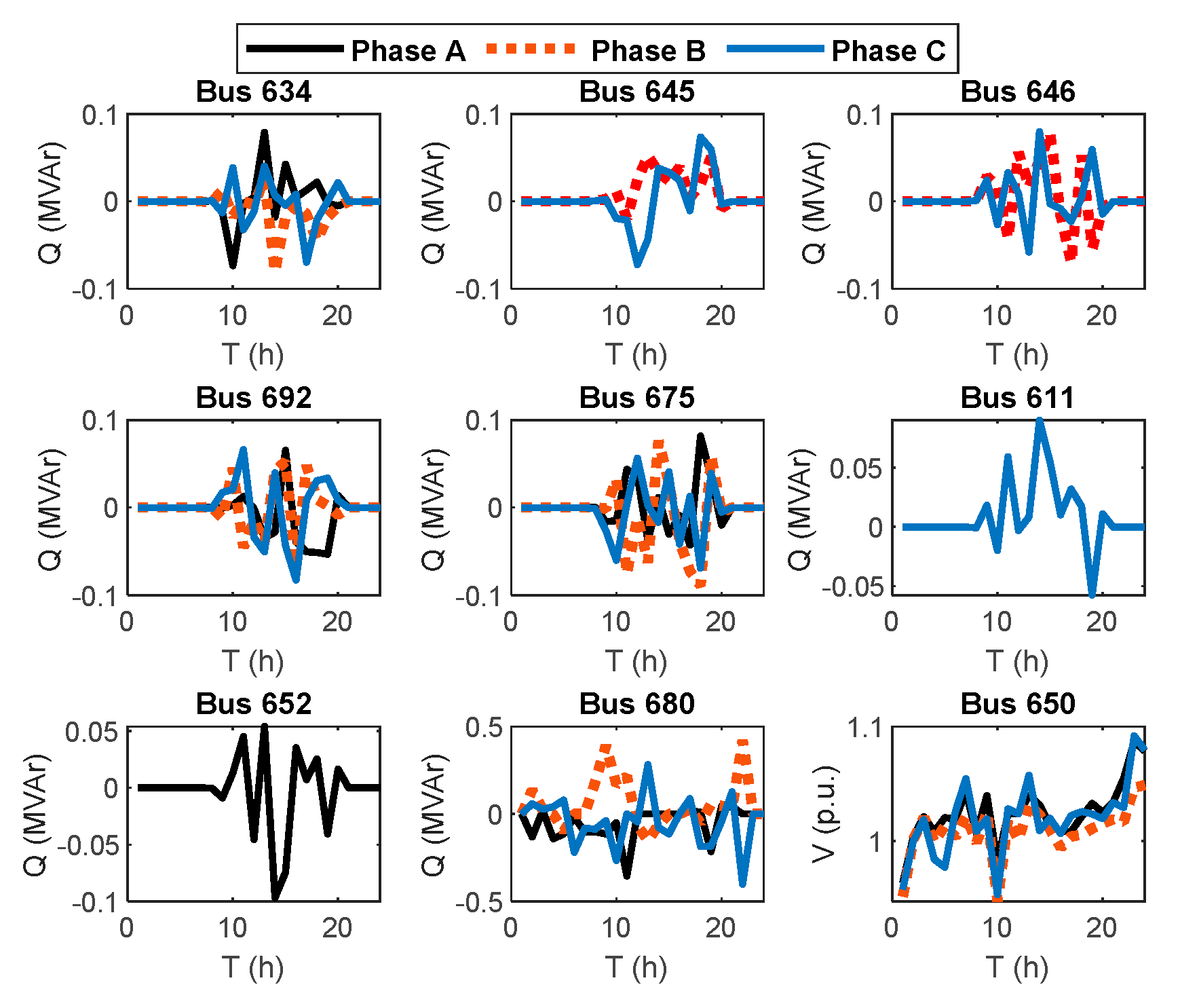

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 show the optimal values of the control variables for these best scenarios.

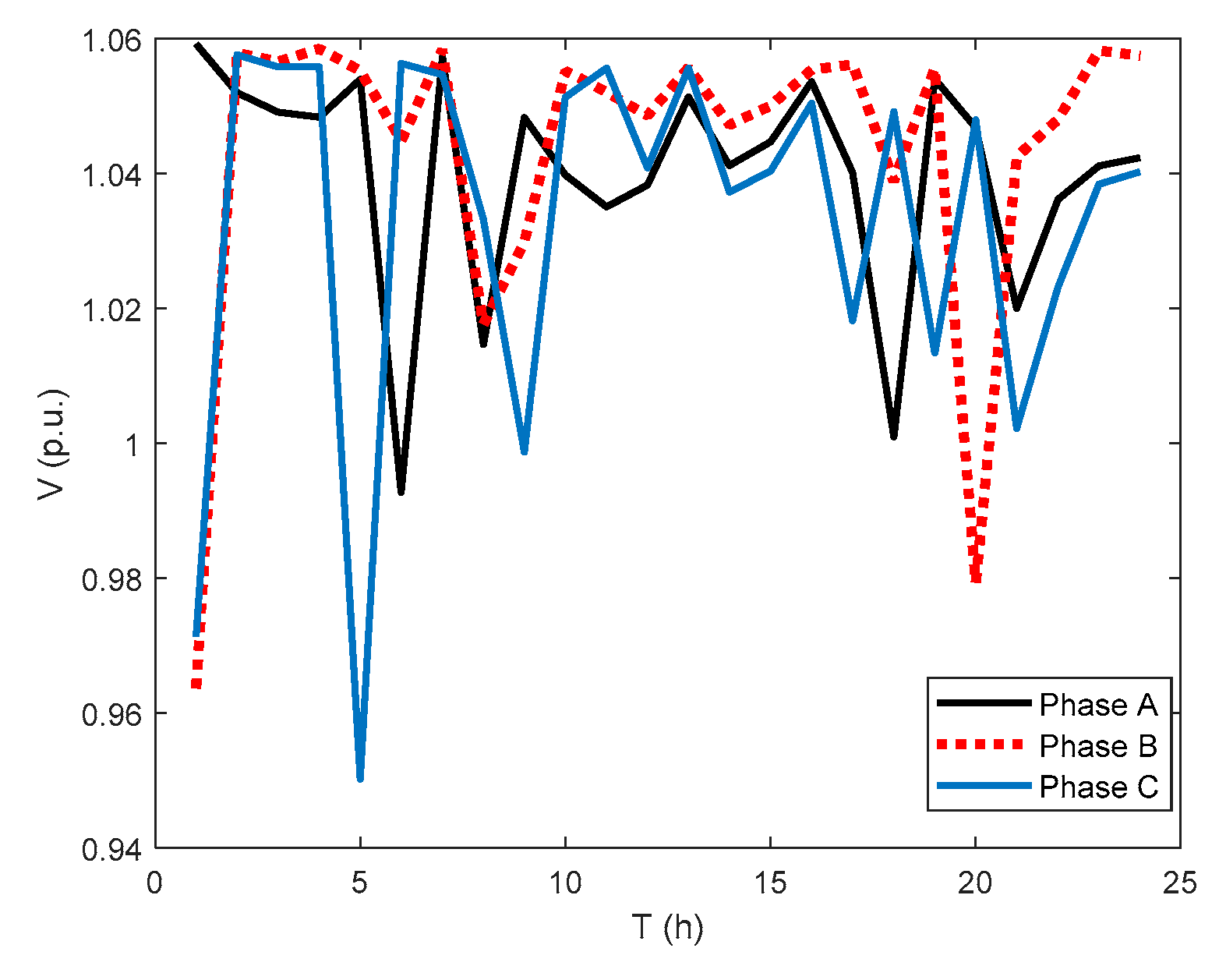

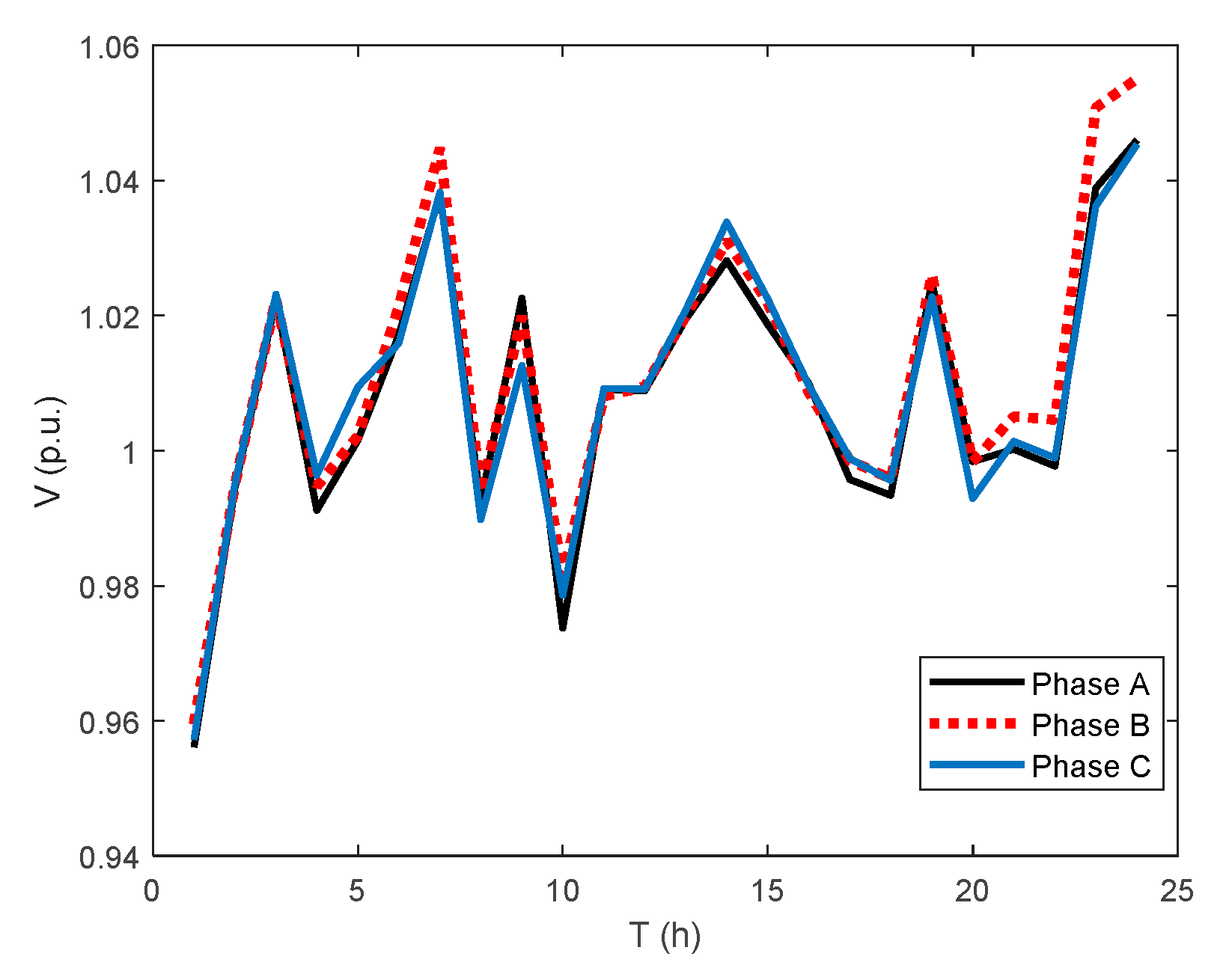

The voltage profiles at the bus 671 for the best scenario in Case 1 and the best scenario in Case 2 are shown in

Figure 12 and

Figure 13, respectively.

In Case 1, ORPD reduces the active energy losses compared to the base case, while the voltages are within the permissible limits, as shown in

Figure 12. The phase voltage magnitudes are much closer to each other in Case 2 (

Figure 13) than in Case 1 (

Figure 12). Clearly, this is as a consequence of the

PVUR minimization in Case 2.

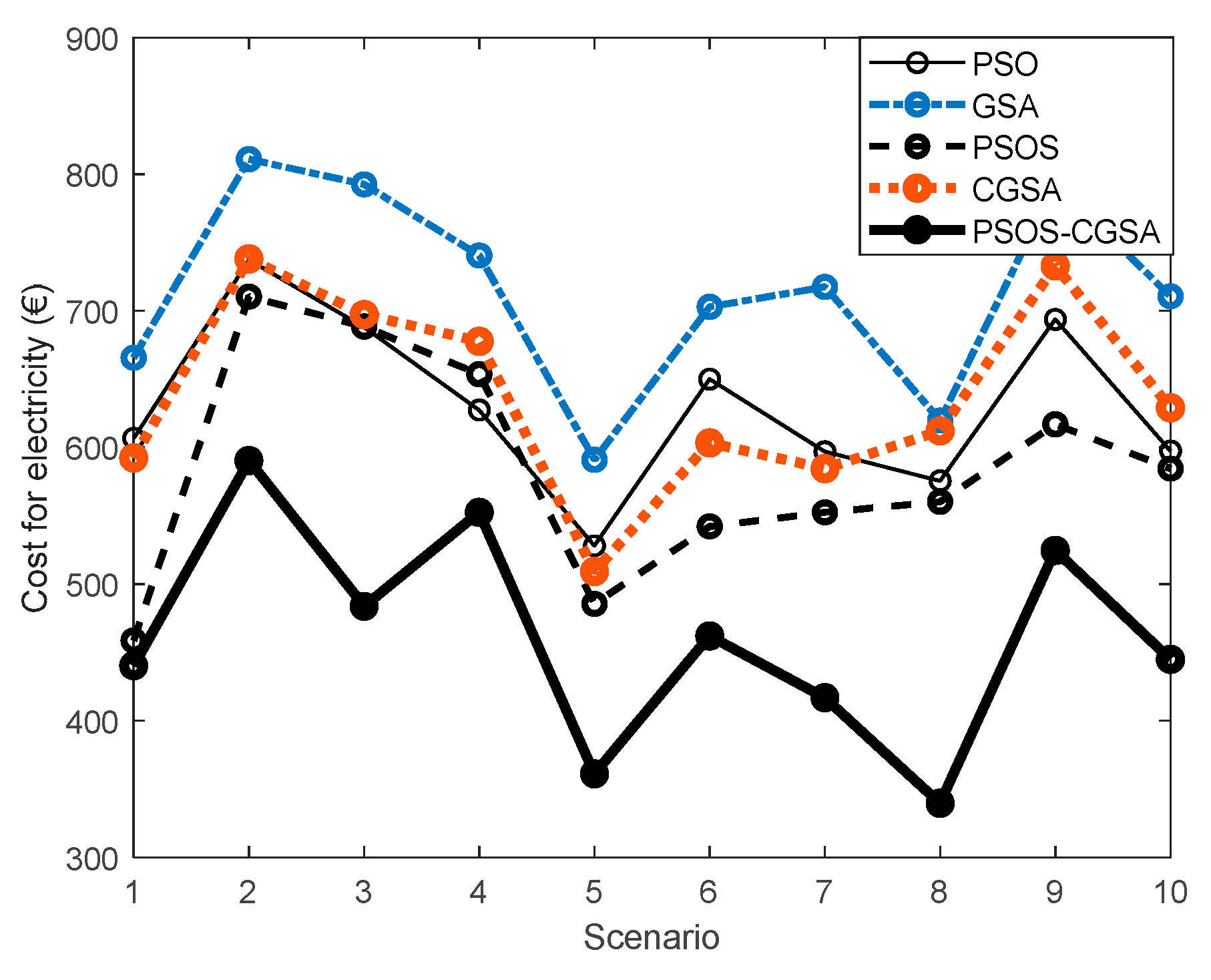

5.3. Evaluation of PSOS-CGSA

Тhe efficiency of the proposed solution algorithm (PSOS-CGSA) was confirmed by a comparison with well-established metaheuristic algorithms PSO, GSA and theirs recent improved versions PSOS [

24] and CGSA [

25]. Algorithm parameters displayed in Table IX, are adopted based on their default values in the cited references. The population size and maximum iteration number are set as:

N=50 and

itmax=200 for all case studies. All algorithms were employed to solve the problem of OAPD under the same terms and input data.

The daily costs for electricity obtained for all 10 reduced scenarios are shown in

Figure 14. It is clear that the proposed hybrid PSOS-CGSA method finds better solutions for the OAPD problem, i.e., provides lower costs in each of 10 scenarios compared to PSO, GSA, PSOS and CGSA algorithms.

Table 9.

Algorithms parameters.

Table 9.

Algorithms parameters.

| PSO |

C1=2; C2=2; wmax=0.9; wmin=0.4 |

| GSA |

G0=1; α=20; p=2; K0=1 |

| PSOS |

C1i=0.5; C1f=2.5; λ=0.0001; wmax=0.9; wmin=0.4 |

| CGSA |

G0=1; α=20; wmax=0.1; wmin=1e-10; Sinusoidal map |

| PSOS-CGSA |

C1i=0.5; C1f=2.5; λ=0.0001; G0=1; α=20; Sinusoidal map |

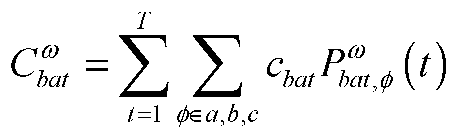

Figure 1.

Inverter capability curve. (a) Diagram of two-quadrant regulating capacity of a PV model, (b) Diagram of four-quadrant regulating capacity of a BESS model.

Figure 1.

Inverter capability curve. (a) Diagram of two-quadrant regulating capacity of a PV model, (b) Diagram of four-quadrant regulating capacity of a BESS model.

Figure 2.

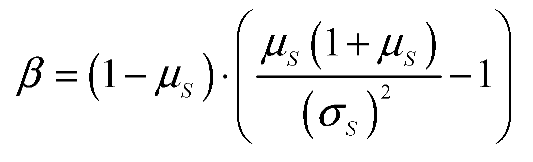

Flowchart for the active power dispatch using PSOS-CGSA.

Figure 2.

Flowchart for the active power dispatch using PSOS-CGSA.

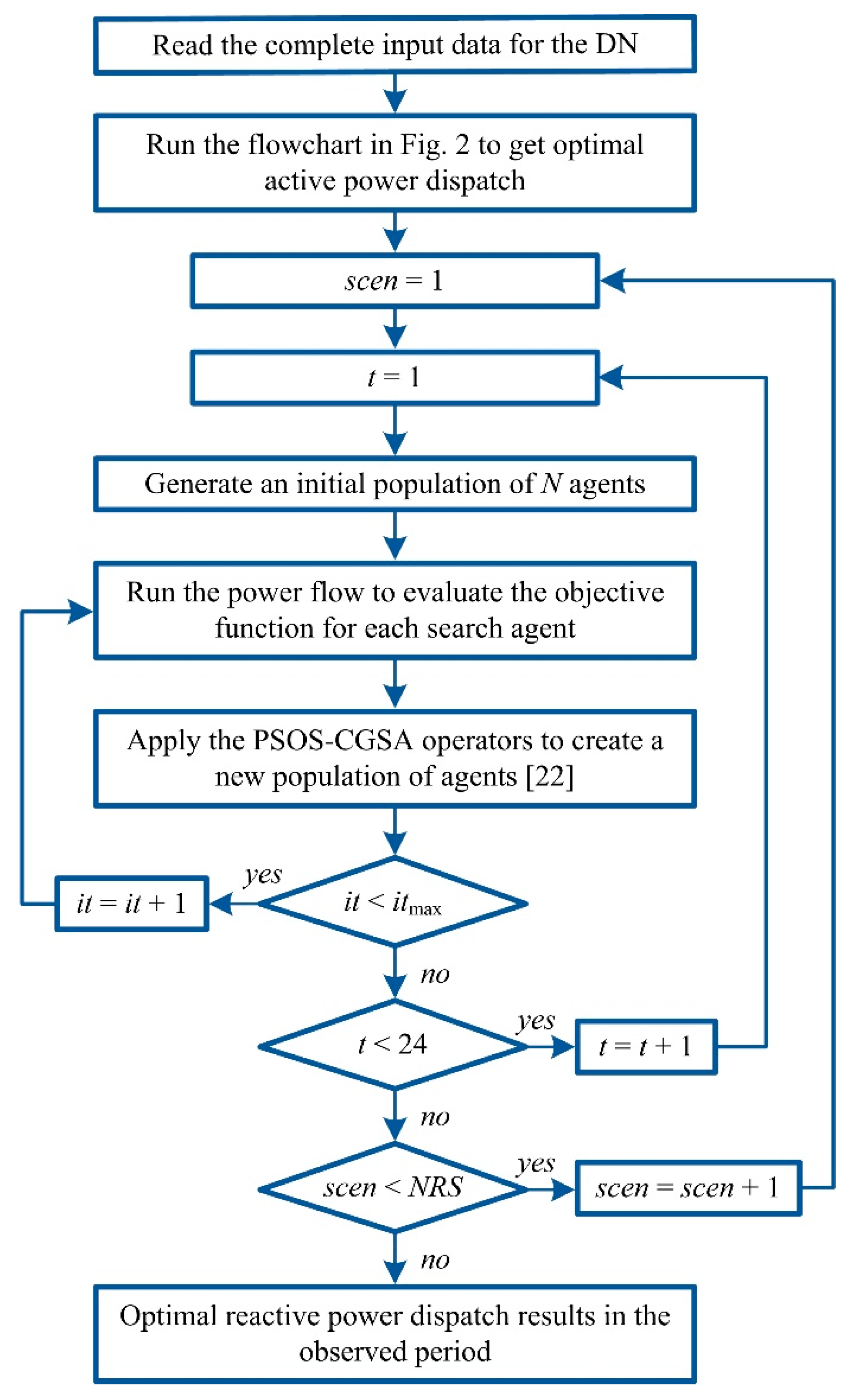

Figure 3.

Flowchart for the reactive power dispatch using PSOS-CGSA.

Figure 3.

Flowchart for the reactive power dispatch using PSOS-CGSA.

Figure 4.

Single-line diagram of the modified IEEE 13-bus test system.

Figure 4.

Single-line diagram of the modified IEEE 13-bus test system.

Figure 5.

Scenarios generated by MCS.

Figure 5.

Scenarios generated by MCS.

Figure 6.

Reduced scenarios of solar irradiance and load.

Figure 6.

Reduced scenarios of solar irradiance and load.

Figure 7.

Expected battery power during the day.

Figure 7.

Expected battery power during the day.

Figure 8.

Expected battery SoC during the day.

Figure 8.

Expected battery SoC during the day.

Figure 9.

Comparison of expected daily costs for electricity: (i) without BESS, (ii) with the BESS using approach in [

12], (iii) with the BESS using the proposed OAPD algorithm.

Figure 9.

Comparison of expected daily costs for electricity: (i) without BESS, (ii) with the BESS using approach in [

12], (iii) with the BESS using the proposed OAPD algorithm.

Figure 10.

Optimal values of control variables for the best scenario (9) in Case 1.

Figure 10.

Optimal values of control variables for the best scenario (9) in Case 1.

Figure 11.

Optimal values of control variables for the best scenario (1) in Case 2.

Figure 11.

Optimal values of control variables for the best scenario (1) in Case 2.

Figure 12.

Voltage profile at bus 671 in Case 1.

Figure 12.

Voltage profile at bus 671 in Case 1.

Figure 13.

Voltage profile at bus 671 in Case 2.

Figure 13.

Voltage profile at bus 671 in Case 2.

Figure 14.

Comparison of solution methods applied for OAPD.

Figure 14.

Comparison of solution methods applied for OAPD.

Table 1.

Parameters of PV units.

Table 1.

Parameters of PV units.

|

Ppvn (kW) |

Sstc (kW/m2) |

Rc (kW/m2) |

| 250 |

1 |

0.12 |

Table 2.

Parameters of BESS.

Table 2.

Parameters of BESS.

|

Pbat,chmax (MW) |

Pbat,dchmax (MW) |

SoCmax (%) |

SoCmin (%) |

ηch= ηdch

|

cbat (€/MWh) |

| 0.9 |

0.9 |

80 |

20 |

1 |

10 |

Table 3.

Load profile data.

Table 3.

Load profile data.

| Hour |

μL (p.u.) |

Hour |

μL (p.u.) |

Hour |

μL (p.u.) |

| 1 |

0.1591 |

9 |

0.5644 |

17 |

0.6715 |

| 2 |

0.2045 |

10 |

0.5372 |

18 |

1.0000 |

| 3 |

0.1948 |

11 |

0.6026 |

19 |

0.9310 |

| 4 |

0.1858 |

12 |

0.5496 |

20 |

0.7588 |

| 5 |

0.1963 |

13 |

0.4893 |

21 |

0.8244 |

| 6 |

0.1866 |

14 |

0.4847 |

22 |

0.9924 |

| 7 |

0.3154 |

15 |

0.4493 |

23 |

0.7869 |

| 8 |

0.5499 |

16 |

0.4390 |

24 |

0.5222 |

Table 4.

Solar irradiance data.

Table 4.

Solar irradiance data.

| Hour |

μS (W/m2) |

σS (W/m2) |

| 8 |

158 |

120 |

| 9 |

386 |

248 |

| 10 |

538 |

277 |

| 11 |

669 |

261 |

| 12 |

748 |

242 |

| 13 |

819 |

221 |

| 14 |

862 |

207 |

| 15 |

870 |

197 |

| 16 |

853 |

205 |

| 17 |

779 |

237 |

| 18 |

700 |

258 |

| 19 |

572 |

263 |

| 20 |

357 |

206 |

Table 5.

Electricity price data.

Table 5.

Electricity price data.

| Hour |

cg (€/MWh) |

Hour |

cg (€/MWh) |

Hour |

cg (€/MWh) |

| 1 |

67.59 |

9 |

83.53 |

17 |

82.02 |

| 2 |

65.31 |

10 |

81.26 |

18 |

82.77 |

| 3 |

52.40 |

11 |

72.14 |

19 |

85.05 |

| 4 |

45.56 |

12 |

68.35 |

20 |

88.85 |

| 5 |

50.12 |

13 |

65.31 |

21 |

101.00 |

| 6 |

59.23 |

14 |

65.00 |

22 |

91.13 |

| 7 |

71.38 |

15 |

68.04 |

23 |

80.50 |

| 8 |

82.02 |

16 |

72.90 |

24 |

73.66 |

Table 6.

Expected costs.

| Scenario |

Probability |

Cost (€) |

| 1 |

0.04 |

440.22 |

| 2 |

0.08 |

590.36 |

| 3 |

0.06 |

483.70 |

| 4 |

0.08 |

552.52 |

| 5 |

0.06 |

361.21 |

| 6 |

0.11 |

462.06 |

| 7 |

0.23 |

416.95 |

| 8 |

0.13 |

339.61 |

| 9 |

0.12 |

524.65 |

| 10 |

0.11 |

444.86 |

| Expected |

|

453.16 |

Table 7.

ORPD results for Wloss.

Table 7.

ORPD results for Wloss.

| Scenario |

Probability |

Wloss (kWh) |

| Base |

Case 1 |

Case 2 |

| 1 |

0.04 |

969.62 |

725.76 |

849.90 |

| 2 |

0.08 |

931.60 |

730.77 |

859.22 |

| 3 |

0.06 |

878.93 |

681.53 |

813.92 |

| 4 |

0.08 |

931.63 |

726.75 |

879.11 |

| 5 |

0.06 |

973.22 |

761.71 |

882.67 |

| 6 |

0.11 |

1016.80 |

805.72 |

951.66 |

| 7 |

0.23 |

937.08 |

724.04 |

873.22 |

| 8 |

0.13 |

990.97 |

776.68 |

919.96 |

| 9 |

0.12 |

804.23 |

616.91 |

759.31 |

| 10 |

0.11 |

977.61 |

772.15 |

905.42 |

| Expected |

|

940.44 |

732.62 |

873.16 |

Table 8.

ORPD results for PVURmax.

Table 8.

ORPD results for PVURmax.

| Scenario |

Probability |

PVURmax (%) |

| Base |

Case 1 |

Case 2 |

| 1 |

0.04 |

12.54 |

7.70 |

1.14 |

| 2 |

0.08 |

10.45 |

6.46 |

2.93 |

| 3 |

0.06 |

8.42 |

7.43 |

2.05 |

| 4 |

0.08 |

8.97 |

7.32 |

1.51 |

| 5 |

0.06 |

11.91 |

6.46 |

2.75 |

| 6 |

0.11 |

10.01 |

7.85 |

2.67 |

| 7 |

0.23 |

8.34 |

6.46 |

1.71 |

| 8 |

0.13 |

8.06 |

6.83 |

1.16 |

| 9 |

0.12 |

6.46 |

7.58 |

1.46 |

| 10 |

0.11 |

10.55 |

6.43 |

2.29 |

| Expected |

|

9.10 |

6.96 |

1.91 |