1. Introduction

Coronary heart disease (CHD, also known as ischaemic heart disease) is a widespread condition that is the leading cause of death and disability in the adult population [

1]. The development of surgical and pharmacological treatments for CHD has led to an increase in patient survival, but there remains a high risk of post-infarction complications and deterioration in the quality of life in people who have had a myocardial infarction [

2]. Therefore, the development and implementation of new methods to restore blood flow in myocardial ischaemic areas has been an urgent problem in cardiac surgery for many years [

3]. The development of alternative methods of myocardial revascularisation, including the use of tissue engineering and cellular technology, is receiving much attention in the treatment of CHD.

There are two main approaches in the development of cell therapy methods for the treatment of CHD: the first approach is cell transplantation to replace the lost myocardial contractile elements; the second approach is cell transplantation to paracrine stimulation of regenerative processes and restoration of blood supply in ischaemically affected tissues [

3,

4]. Transplantation of iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes can be used to restore of lost myocardial tissue in cell replacement therapy [

5,

6]. Such differentiated cardiomyocytes are contractile, excitable, and respond to the autonomic nervous system signals [

7]. However, they are functionally immature and have a fetal phenotype [

5]. Therefore, it is necessary to study the dynamics of action potential formation and calcium currents during the maturation of cardiomyocytes from iPSCs, as well as to assess the functional status of cardiomyocytes after transplantation when developing approaches in cell replacement therapy for CHD. The formation of contractile apparatus and sarcoplasmic reticulum structures, stabilization of intracellular calcium ion oscillation, production of mature isoforms of ion channels and connexins, increasing the number of mitochondria, metabolic changes occur during cardiomyocyte maturation. To accelerate these processes, technologies of cell layer formation, cultivation under electric current stimulation, mechanical stretching and

in vivo persistence are used [

5,

6,

8,

9,

10,

11].

The aim of this work was to develop a technique for the formation of functional layers of human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes capable to generate rhythmic and synchronous contractions and to study the possibility of accelerating cardiomyocyte maturation after subcapsular renal transplantation into the SCID mice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Generation of Cardiomyocytes

A human iPSC (iMA-1L cell line, ICG SB RAS, Novosibirsk, Russia) was applied for directional differentiation into cardiomyocytes [

12]. iPSC was cultured on an LDEV-Free Matrigel™ hESC-qualified matrix (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) in Essential-8 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Differentiation was carried out in accordance with a previously published protocols based on the activation of the WNT pathway using CHIR99021 (StemRD, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 48 h and subsequent inhibition with IWP2 (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) in RPMI-1640 (Lonza, Köln, Germany) with B27-supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) without insulin [

13,

14]. On days 14–18 of differentiation, the cells were dissociated using TrypLE Express (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and transferred into 6-well plates coated with Matrigel™ (Corning, USA) in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 20% embryonic bovine serum (Autogene Bioclear, Calne, UK) and 10 µM Y-27632 supplement (StemRD, USA). Two days after the transfer and within one week, metabolic cell selection was carried out to purify the population of cardiomyocytes [

15]. Composition of the metabolic selection medium: RPMI-1640 without D-glucose (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), 213 μg/mL L-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA), 500 µg/mL recombinant human albumin expressed in

Oryza sativa (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and 5 mM DL-sodium lactate L4263 (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). To form cell layers, cardiomyocytes were seeded at a density of 250,000 cells per 1 cm

2 on temperature-sensitive Nunc UpCell plate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). When the temperature dropped to 20° C, the cardiomyocyte cell layers were detached from the plastic and used for transplantation.

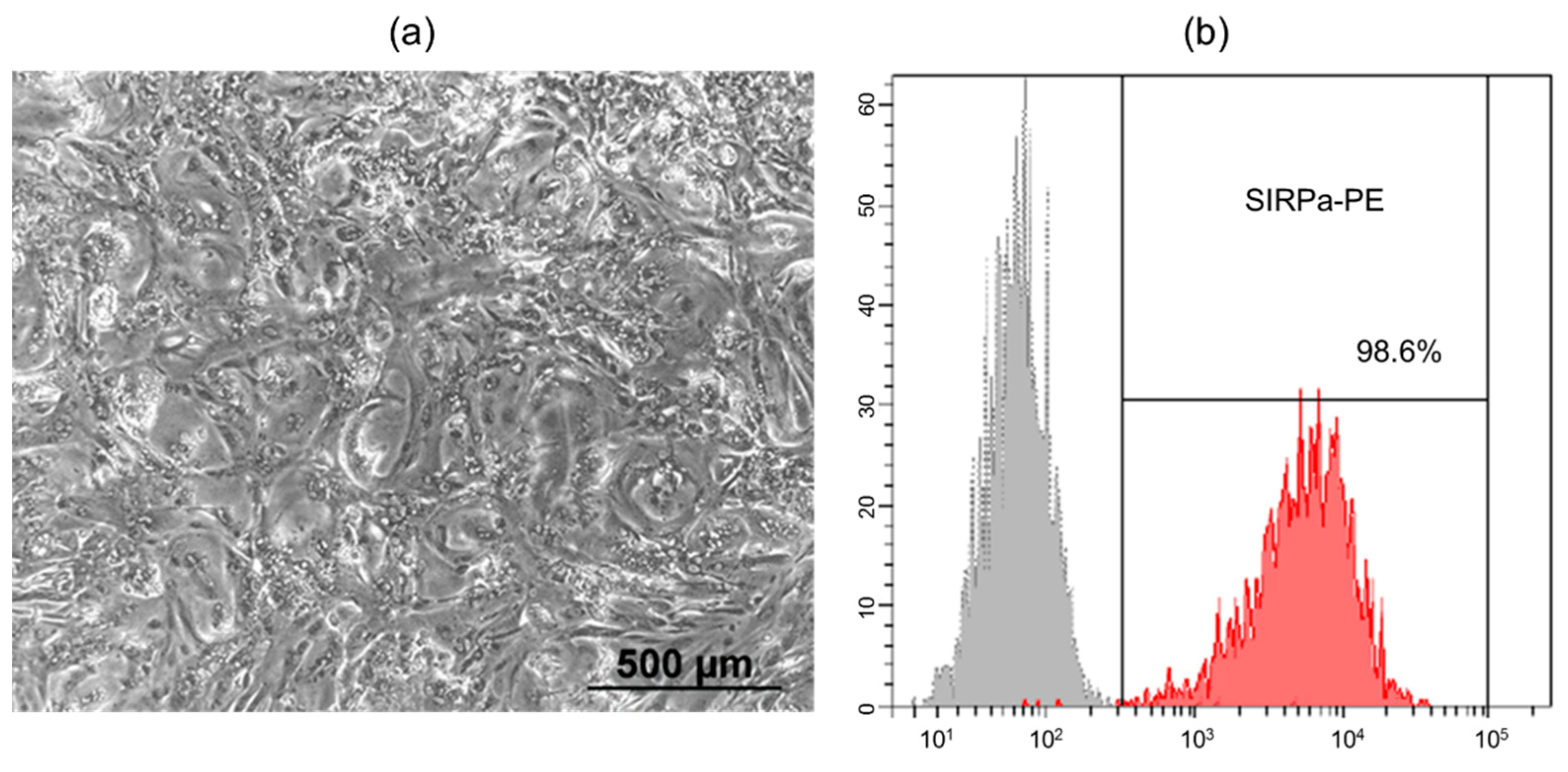

2.2. Flow Cytometry

Cell cultures were dissociated with Dispase (1 mg/ml) (Stemcell Technologies, Van-couver, Canada) and were labeled with SIRPa-PE (#323806, Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA) antibodies at recommended concentrations. The stained cells were analyzed on FACS Canto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) using FACS Diva software.

2.3. Renal Subcapsular Transplantation

The animal tests conducted in an SPF vivarium (ICG SB RAS, Novosibirsk, Russia). Experiments were performed in compliance with the protocols and recommendations for the proper use and care of laboratory animals (ECC Directive 86/609/EEC). Experimental protocol were approved by the Institute of Cytology and Genetics ethical board (permit No. 22.4 by 30.05.2014).

Male SCID mice (n=10) aged 6-8 weeks and weighing 26-30 g were used. Mice were housed in sibling groups (2-5 animals) in OptiMice IVC cages (Animal Care Systems, Centennial, CO, USA) at the Center for Genetic Resources of Laboratory Animals at the Institute of Cytology and Genetics (RFMEFI62119X0023). Water and granulated forage (Sniff, Soest, Germany) were given ad libitum. Animals were kept in a 14 h light (2 a.m. to 4 p.m.) and 10 h dark (4 p.m. to 2 a.m.) cycle, temperature (22–24 °C), and relative humidity (40–50%) controlled environment with unlimited access to water and food (Mucedola, Settimo Milanese, Italy).

Mice were anesthetized with Zoletil-100 (30 mg/kg) (Virbac Sante Animale, Carros, France) and Domitor (0.25 mg/kg) (Orionpharma, Espoo, Finland). The obtained cardiomyocyte layers were transplanted under the left renal fibrous capsule. The kidney was accessed through the left lateral subcostal incision followed by manual eventration. Using a 200 µl tip (Axigen, Corning Inc., USA), the integrity of the fibrous capsule was broken and the cardiomyocyte implant was injected using an automatic pipette. After 42 days, the animals were euthanized by continued exposure to CO2. The implants were extracted and divided into 2 parts, for microscopic studies and functional tests. Formed cardiomyocyte cell layers, which were cultured in Matrigel™ layer (Corning, USA) at 37° C and 5% CO2 atmosphere throughout the experiment, were used as a control.

2.4. Calcium Flux Assay

Formed cardiomyocyte cell layers were incubated for 30 min in a cultural medium at 37° C with the 4 μg/ml green fluorescent calcium binding dye Fluo-8 AM (Abcam, Cam-bridge, UK). Then the dye solution was exchanged with a Tyrode’s solution (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), and the oscillation of calcium fluxes in cells was documented using an Eclipse Ti-E fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) with a DS Qi1Mc camera and the NIS software package (Nikon, Japan). Video with fixed camera parameters (130 fps) was processed using ImageJ software (U. S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) and signal intensity vs. time was plotted.

2.5. Preparation of Cryosections and Immunofluorescent Staining

Cardiomyocyte cell layers were frozen in Tissue-Tek OCT medium (Sakura Finetek, Tokyo, Japan) to -22° C. Ten-micrometers sections were made using a Microm HM-550 cryostat (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and attached to SuperFrost Plus slides (Menzel-Gläser, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Cryosections on slides were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 10 min, washed three times for 5 min with PBS, permeabilized with 0.05% Triton X-100 in PBS (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 10 min, washed three times for 5 min with PBS, and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 30 min. The slides were stained with primary antibodies in a humidified chamber overnight at 4° C, washed three times for 10 min with PBS, incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h in the dark at room temperature and washed three times for 10 min with PBS. Nuclei were stained with Vectashield Antifade Mounting Medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Newark, CA, USA). The stained samples were analyzed with an Eclipse Ti-E fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) with the NIS software package (Nikon, Japan) and THUNDER Imager Live Cell & 3D Cell Culture & 3D Assay (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) at the Common Facilities of Microscopic Analysis of Biological Objects (ICG SB RAS, Novosibirsk, Russia).

The following primary antibodies were used (dilution 1:100 with 1% BSA in PBS): anti-human Sarcomeric Alpha Actinin antibody (#ab9465, Abcam, UK), anti-human Nkx-2.5 antibody (#sc-14033, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-mouse CD31 antibody (#102502, Biolegend, USA). The following secondary antibodies were used (dilution 1:400 in 1% BSA in PBS): Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG H + L (#A11008, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rat IgG H + L (#A11006, Life Technologies, USA), Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-mouse IgG1 (#A21124, Life Technologies, USA).

2.6. Transmission Electron Microscopy

Fragments of cardiomyocyte cell layers were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in Hanks' medium, postfixed in 1% OsO4 solution in PBS pH 7.4 for 1 h, dehydrated in an ethanol series, and then embedded in Epon ribbon (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Semi-thin sections of 1 µm thickness were obtained on a Leica EM UC7 ultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems, Germany), stained with toluidine blue and preexaminated by using a Leica DME light microscope (Leica Microsystems, Germany). Ultra-thin sections 70-100 nm thick were cut using ultramicrotome Leica EM UC7 (Leica Microsystems, Germany), contrasted with saturated aqueous solution of uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Digital photographs were taken with a JEM 1400 electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) at the Common Facilities of Microscopic Analysis of Biological Objects (ICG SB RAS, Novosibirsk, Russia).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical processing of the results was carried out using the STATISTICA 8.0 software (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). Normality of data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Student's two-sample t-test was used to identify the differences between the groups. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD).

3. Results and Discussion

Human induced pluripotent stem cell line (iMA-1L) was generated from embryonic fibroblasts of MAN1 line in the laboratory of epigenetics of development of ICG SB RAS [

12]. Differentiation protocol based on the activation of the WNT signaling pathway to form mesodermal precursors and terminal differentiation into cardiomyocytes with subsequent inhibition of WNT pathway [

13,

14]. The appearance of spontaneously contracting areas was observed on days 8–10 of differentiation, subsequently the number of contracting areas and the intensity of contractions increased. Then metabolic selection was performed in medium containing lactate instead of glucose in order to remove undifferentiated cells from the resulting culture. Lactate is metabolised only by cardiomyocytes - other cells are eliminated in the absence of glucose. After metabolic selection, the number of cardiomyocytes in the differentiated cell population was 98.6% by flow cytometry analysis with antibodies to SIRPa (CD172a) - a marker of iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes [

16] (

Figure 1).

Next, spontaneously contracting iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes were seeded at a density of 250,000 cells per 1 cm

2 onto heat-sensitive plastic. The formed functional cell layers were detached from the plastic at room temperature and injected under the SCID mouse kidney capsule. SCID mice have a severe combined immunodeficiency syndrome as a result of a mutation in the RAG genes responsible for the rearrangement of immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor genes. Due to the reduced rejection reaction of xenografts from SCID mice, they have traditionally been used as one of the model objects for the transplantation of tissue samples from other species, including humans [

17,

18]. The kidney is especially suited for the transplantation of cells and tissues as it is easily accessible and transplanted tissues are well contained under the renal capsule in a highly vascularized site. [

19,

20,

21].

Mice recovery was unproblematic, and no signs of discomfort or infection were noted. At 42 days after surgery when the animals were euthanized, all transplants were readily identifiable and highly localized under the renal capsule. Then transplants were dissected away from the fibrous capsule and kidney body (

Figure 2).

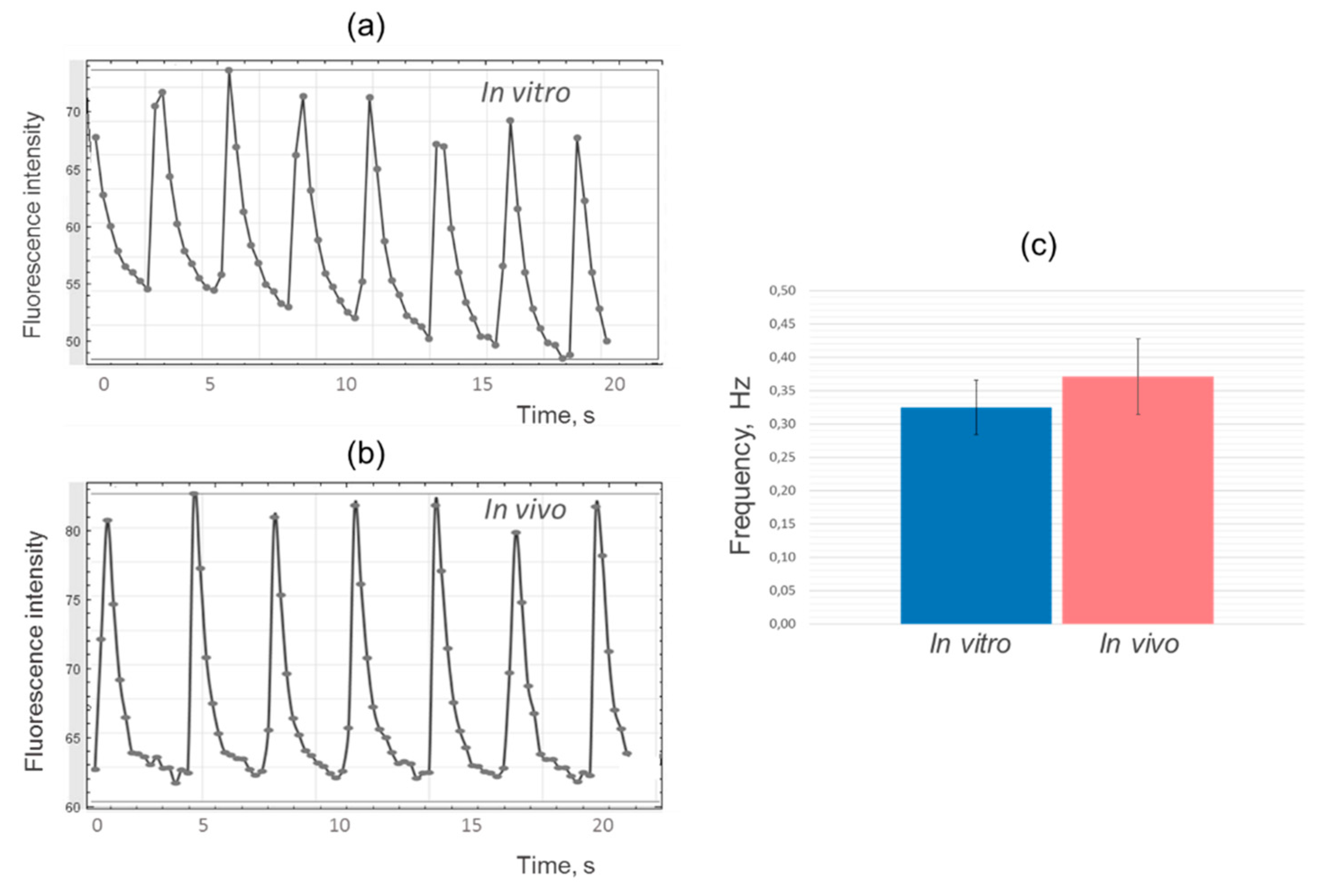

When calcium ion fluxes were analysed, a spontaneous regular change in Fluo-8 luminescence was detected in every sample of

in vivo cultured cardiomyocyte cell layers (

Figure 3).

During an action potential, cardiomyocytes contract by membrane depolarization caused by the rapid influx of calcium into the cell through voltage-gated calcium channels. To visualize calcium currents, we used Fluo-8 dye, widely applied to measure action potentials and contraction rate of cardiomyocytes [

22,

23]. As calcium enters the cell, it binds to intracellular Fluo-8, causing the fluorescence of the calcium indicator to increase. Similarly, as calcium is pumped out of the cell during the repolarisation phase of the action potential, the fluorescence of the indicator is reduced as the intracellular calcium concentration decreases [

24,

25].

After processing the results in ImageJ program, diagrams of fluorescence intensity changes were plotted for experimental and control samples. The analysis showed similarity in the shape and frequency of the peaks, which indicates comparable dynamics of calcium ions fluxes in iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes during cultivation of cell layers

in vitro and

in vivo (

Figure 4).

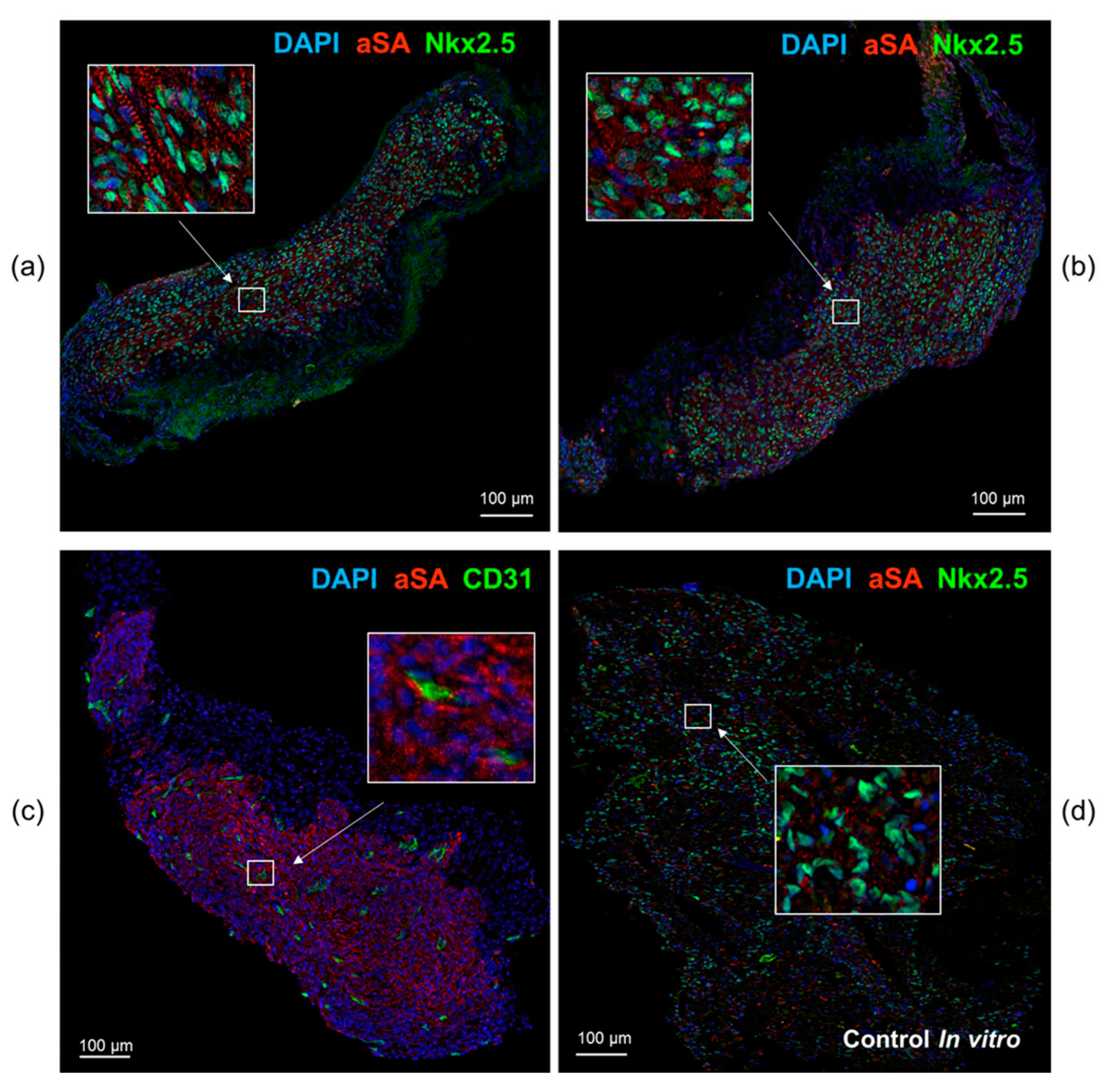

Immunofluorescence staining of cardiomyocyte layers with antibodies to the sarco-meric actinin and cardiomyocyte transcription factor Nkx2.5 indicates that tissue is formed by human cardiomyocytes that persist in SCID mice throughout the experiment and permeated with CD31+ capillaries of mouse origin. The cells from the extracted transplants had an elongated shape and an ordered sarcomeric organization resembling the structure of cardiac myocyte within the myocardium, unlike the cells in the control samples (

Figure 5).

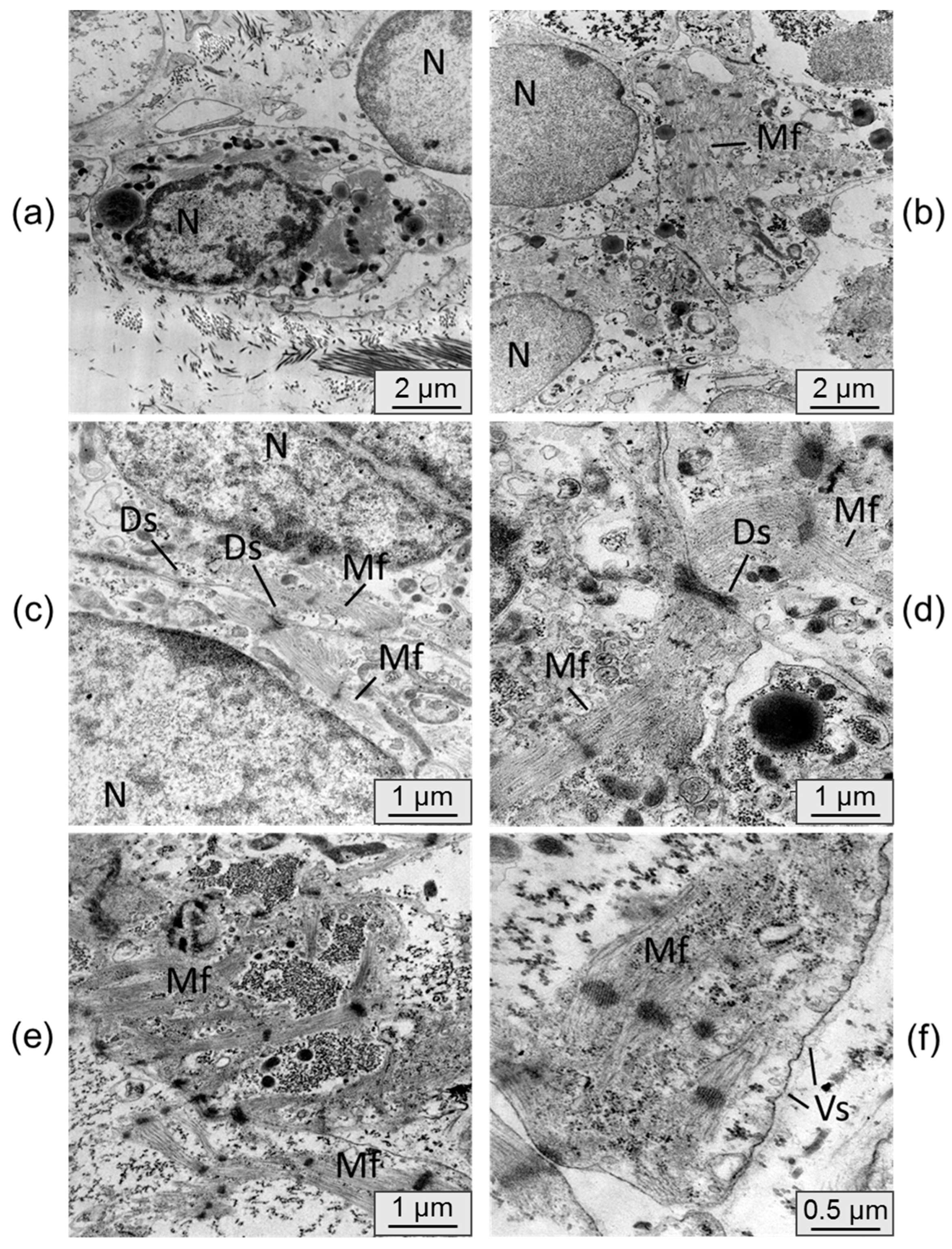

To assess changes in cardiomyocyte ultrastructure after persistence in an immunodeficient mouse, samples were examined by transmission electron microscopy. Electronograms of control samples of cardiomyocyte cell layers cultured

in vitro are presented in

Figure 6.

Electronograms of cardiomyocyte cell layers samples cultured

in vivo under the kidney capsule are presented in

Figure 7.

In most cases cardiomyocytes from control samples were cells without pronounced phenotypic features of a mature cardiomyocyte. The cells were, as a rule, round in shape and had a nucleus with uncondensed chromatin. The formation of sarcomeric myofibrils was observed in isolated cases, but the packing of fibers in them remained loose. The cardiomyocytes were located isolated from each other and did not form functional contacts.

The ultrastructure of the cardiomyocytes in the cell layers, extracted from under the kidney capsule, differed appreciably. The cells were more densely arranged, mutual in-vaginations of individual cardiomyocyte membranes were connected by desmosomes. Cell nuclei had denser chromatin condensation. Cells showed a significantly higher number of transversely striated myofibrils having a sarcomeric structure with ordered myofilaments. In some samples there was a tendency for parallel alignment of myofibrils within the cell. Active formation of cytoplasmic vesicles was also noted in the cells cultured

in vivo, whereas they were almost absent in the control samples. These signs indicate the process of cell maturation and the beginning of the transition from the fetal phenotype to the phenotype of a mature cardiomyocyte [

5].

Previously, we showed that human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes survive well after subcutaneous administration of Matrigel-based cell suspension to SCID mice, however, only some cells retain the ability to spontaneously oscillate calcium ions [

26]. In this work it has been shown that when cardiomyocytes are transplanted as part of a functional cell layer under SCID mouse kidney fibrous capsule, the capacity for coordinated contraction is maintained for at least 6 weeks. It was also shown that during persistence

in vivo, human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes acquire a more organised sarcomeric structure of the contractile apparatus compared to control samples cultured

in vitro.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we have shown that the formation of functional layers of iPSCs-derived cardiomyocytes promotes accelerated cell maturation and retention of the ability to rhythmic contractions after transplantation. However, at this stage of the study we cannot say whether the action potential generation in the transplanted cells is due to stochastic processes in immature contractile cardiomyocytes or to the activity of emerging pacemaker cells, due to a membrane mechanism. Additional research and longer follow-up periods are needed to draw definitive conclusions about the benefits of cardiomyocyte transplantation as part of the formed cell layer. For a clearer understanding of the processes taking place in grafts surrounded by tissues of a living organism, we plan to conduct in vivo visualization of the processes of formation and distribution of calcium currents, as well as to study the response of transplanted cells to the systemic action of neurotransmitters of the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, SP; Data curation, EC and SP; Formal analysis, EC, SP, NB, AV, GK and DS; Funding acquisition, DS; Investigation, EC, SP, NB, AV and GK; Methodology, EС and SP; Project administration, EC and SP; Resources, EC, SP, NB and DS; Validation, SP; Visualization, EC, SP and NB; Writing – original draft, EC; Writing – review & editing, SP, NB and DS.

Funding

This work was carried out within the state assignment of Ministry of Health of Russian Federation (theme # 121031300224-1).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the protocols and recommendations for the proper use and care of laboratory animals (ECC Directive 86/609/EEC) and approved by Local Ethics Committee of the Institute of Cytology and Genetics (approval date 30 May 2014, protocol 22.4).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank Common Facilities Centre “SPF-vivarium of the ICG SB RAS” (

https://ckp.icgen.ru/spf/) for help in organizing the animal tests (supported by the State project of the Institute of Cytology and Genetics (FWNR-2022-2023)).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Benjamin, E.J.; Virani, S.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Chang, A.R.; Cheng, S.; Chiuve, S.E.; Cushman, M.; Delling, F.N.; Deo, R.; et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018, 137, e67–e492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosamond, W.D.; Chambless, L.E.; Heiss, G.; Mosley, T.H.; Coresh, J.; Whitsel, E.; Wagenknecht, L.; Ni, H.; Folsom, A.R. Twenty-two–year trends in incidence of myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease mortality, and case fatality in 4 US communities, 1987–2008. Circulation 2012, 125, 1848–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michler, R.E. The current status of stem cell therapy in ischemic heart disease. J. Card. Surg. 2018, 33, 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Murry, C.E. Function Follows Form―A Review of Cardiac Cell Therapy. Circ. J. 2019, 83, 2399–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funakoshi, S.; Miki, K.; Takaki, T.; Okubo, C.; Hatani, T.; Chonabayashi, K.; Nishikawa, M.; Takei, I.; Oishi, A.; Narita, M.; et al. Enhanced engraftment, proliferation and therapeutic potential in heart using optimized human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolanowski, T.J.; Antos, C.L.; Guan, K. Making human cardiomyocytes up to date: Derivation, maturation state and perspectives. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 241, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, S.V.; Kensah, G.; Rotaermel, A.; Baraki, H.; Kutschka, I.; Zweigerdt, R.; Martin, U.; Haverich, A.; Gruh, I.; Martens, A. Transplantation of purified iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes in myocardial infarction. PloS One 2017, 12, e0173222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, T.; Masumoto, H.; Tajima, S.; Ikuno, T.; Katayama, S.; Minakata, K.; Ikeda, T.; Yamamizu, K.; Tabata, Y.; Sakata, R.; et al. Efficient long-term survival of cell grafts after myocardial infarction with thick viable cardiac tissue entirely from pluripotent stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegler, J.; Tiburcy, M.; Ebert, A.; Tzatzalos, E.; Raaz, U.; Abilez, O.J.; Shen, Q.; Kooreman, N.G.; Neofytou, E.; Chen, V.C.; et al. Human engineered heart muscles engraft and survive long term in a rodent myocardial infarction model. Circ. Res. 2015, 117, 720–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, S.; Shimizu, T. Three-dimensional cardiac tissue fabrication based on cell sheet technology. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 96, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadrin, I.Y.; Allen, B.W.; Qian, Y.; Jackman, C.P.; Carlson, A.L.; Juhas, M.E.; Bursac, N. Cardiopatch platform enables maturation and scale-up of human pluripotent stem cell-derived engineered heart tissues. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigor’eva, E.; Malankhanova, T.; Surumbayeva, A.; Minina, J.; Kizilova, E.; Lebedev, I.; Zakian, S. Generation and characterization of iPSCs from human embryonic dermal fibroblasts of a healthy donor from Siberian population. BioRxiv 2018, 455535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, X.; Zhang, J.; Azarin, S.; Zhu, K.; Hazeltine, L. Directed cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells by modulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling under fully defined conditions. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burridge, P.; Matsa, E.; Shukla, P.; Lin, Z.; Churko, J. Chemically defined generation of human cardiomyocytes. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergeevichev, D.; Balashov, V.; Kozyreva, V.; Pavlova, S.; Vasiliyeva, M.; Romanov, A.; Chepeleva, E. Do Human iPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes Cultured on PLA Scaffolds Induce Expression of CD28/CTLA-4 by T Lymphocytes? J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, N.C.; Craft, A.M.; Sharma, P.; Elliott, D.A.; Stanley, E.G.; Elefanty, A.G.; Gramolini, A.; Keller, G. SIRPA is a specific cell-surface marker for isolating cardiomyocytes derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renz, J.F.; Lin, Z.; de Roos, M.; Dalal, A.A.; Ascher, N.L. SCID mouse as a model for transplantation studies. J. Surg. Res. 1996, 65, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, S.; Vaeteewoottacharn, K.; Kariya, R. Application of highly immunocompromised mice for the establishment of patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models. Cells 2019, 8, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merani, S.; Toso, C.; Emamaullee, J.; Shapiro, A.M.J. Optimal implantation site for pancreatic islet transplantation. Br. J. Surg. 2008, 95, 1449–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Windt, D.J.; Echeverri, G.J.; Ijzermans, J.N.; Cooper, D.K. The choice of anatomical site for islet transplantation. Cell transplant. 2008, 17, 1005–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shultz, L.D.; Goodwin, N.; Ishikawa, F.; Hosur, V.; Lyons, B.L.; Greiner, D.L. Subcapsular transplantation of tissue in the kidney. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2014, 7, 737–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guatimosim, S.; Guatimosim, C.; Song, L.S. Imaging calcium sparks in cardiac myocytes. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 689, 205–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahola, A.; Pölönen, R.P. , Aalto-Setälä, K.; Hyttinen, J. Simultaneous Measurement of Contraction and Calcium Transients in Stem Cell Derived Cardiomyocytes. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 46, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itzhaki, I.; Rapoport, S.; Huber, I.; Mizrahi, I.; Zwi-Dantsis, L.; Arbel, G.; Schiller, J.; Gepstein, L. Calcium handling in human induced pluripotent stem cell derived cardiomyocytes. PLoS One. 2011, 6, e18037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, G.; Lee, B.W.; Protas, L.; Gagliardi, M.; Brown, K.; Kass, R.S.; Keller, G.; Robinson, R.B.; Vunjak-Novakovic, G. Autonomous beating rate adaptation in human stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Nat. Commun. 2016, 19, 10312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, S.V.; Chepeleva, E.V.; Dementyeva, E.V.; Grigor'eva, E.V.; Sorokoumov, E.D.; Slotvitsky, M.M.; Ponomarenko, A.V.; Dokuchaeva, A.A.; Malakhova, A.A.; Sergeevichev, D.S.; et al. Survival and functional activity examination of cardiomyocytes differentiated from human iPSCs, when transplanting in SCID mice. Genes Cells 2018, 13, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).