Submitted:

19 April 2023

Posted:

20 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental work

Synthesis of MnPc films

Characterization of the films

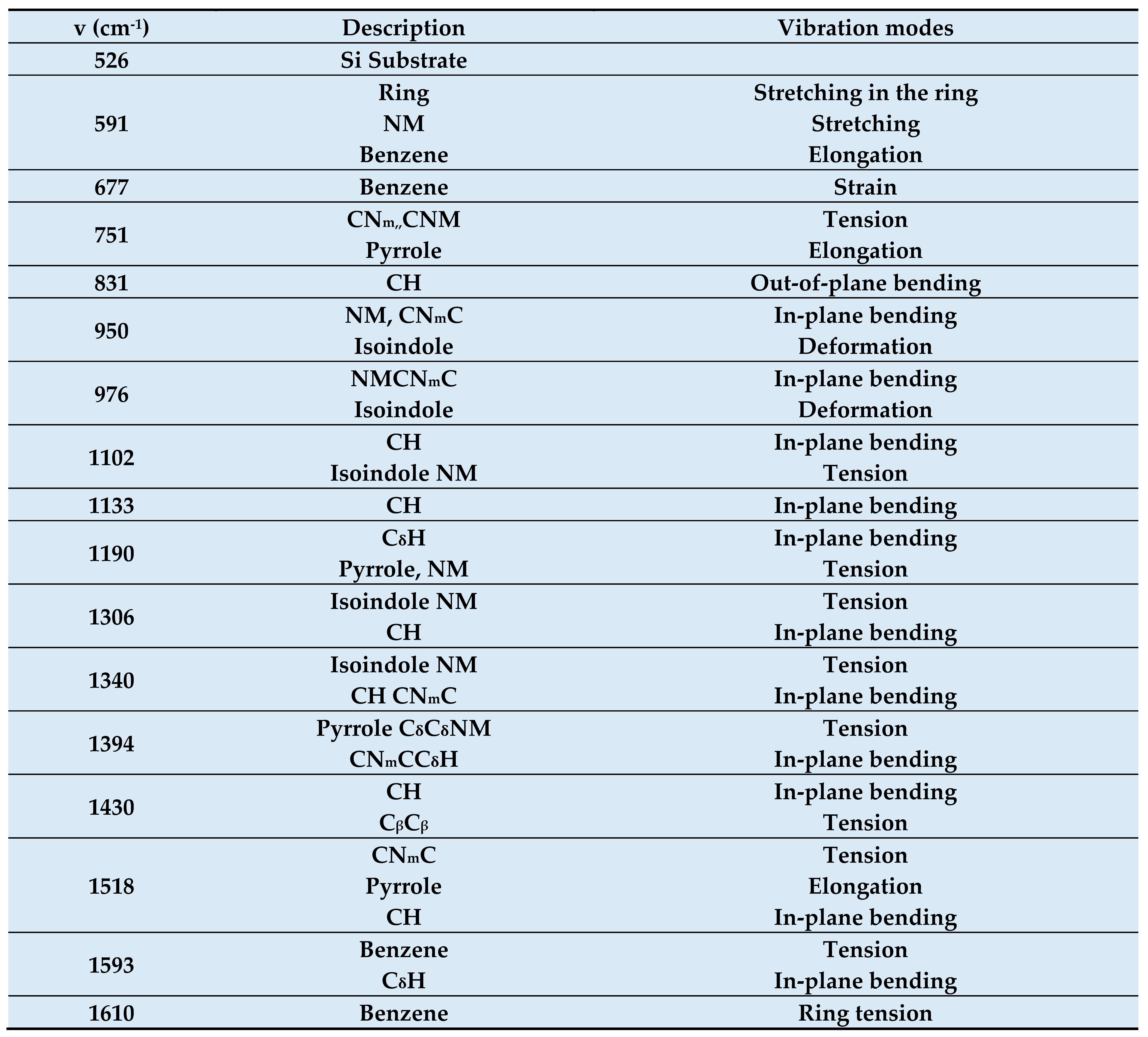

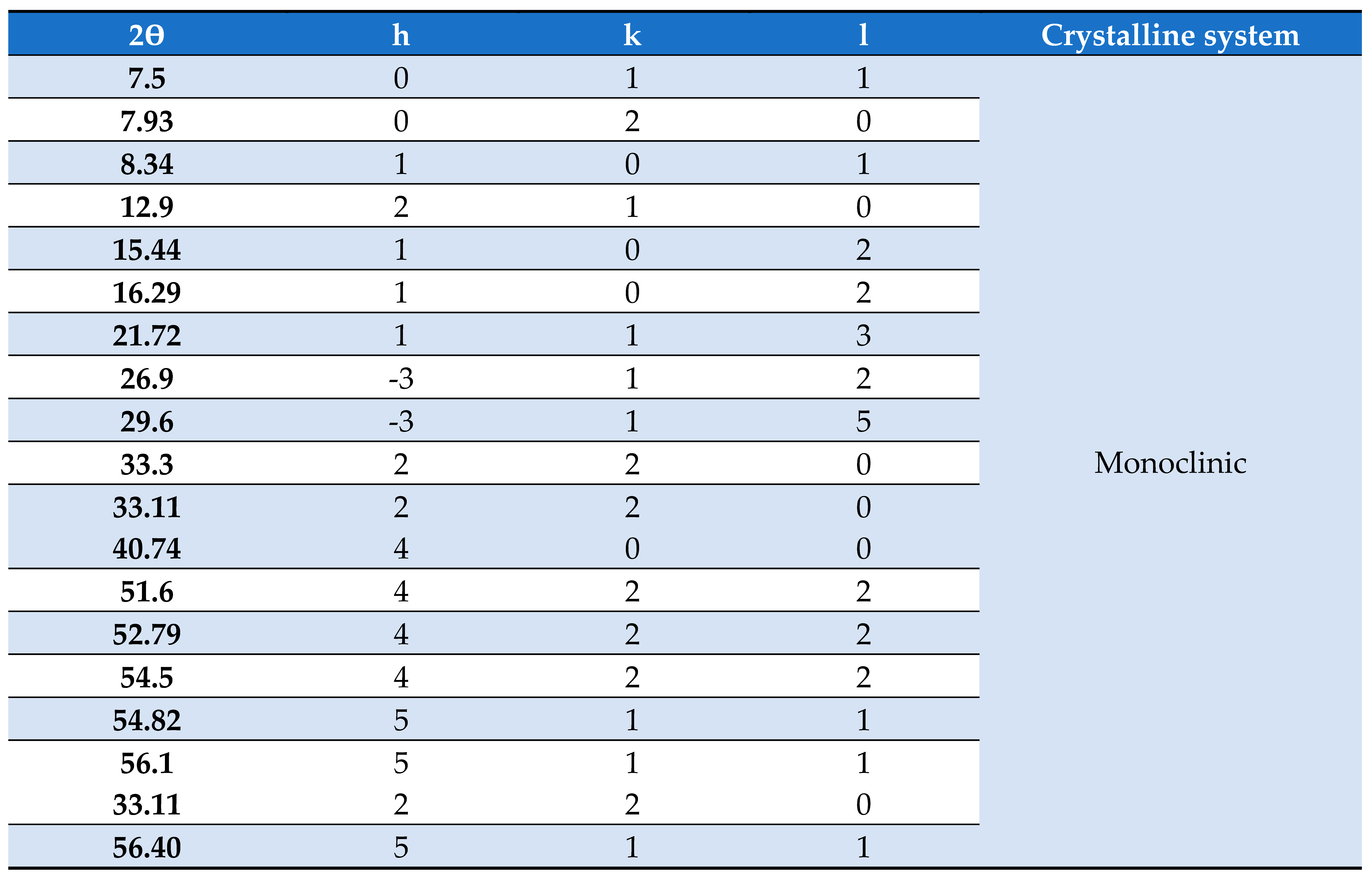

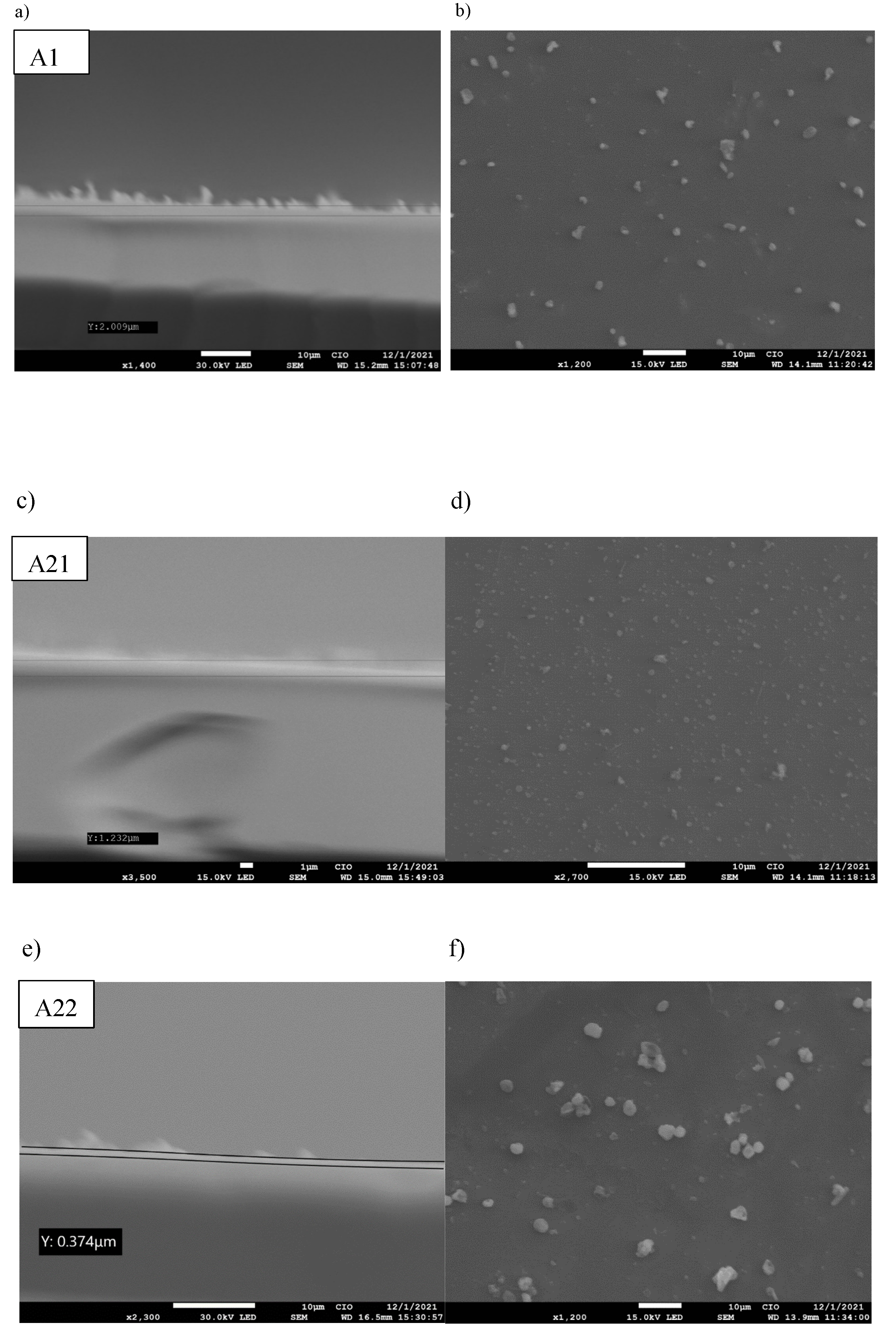

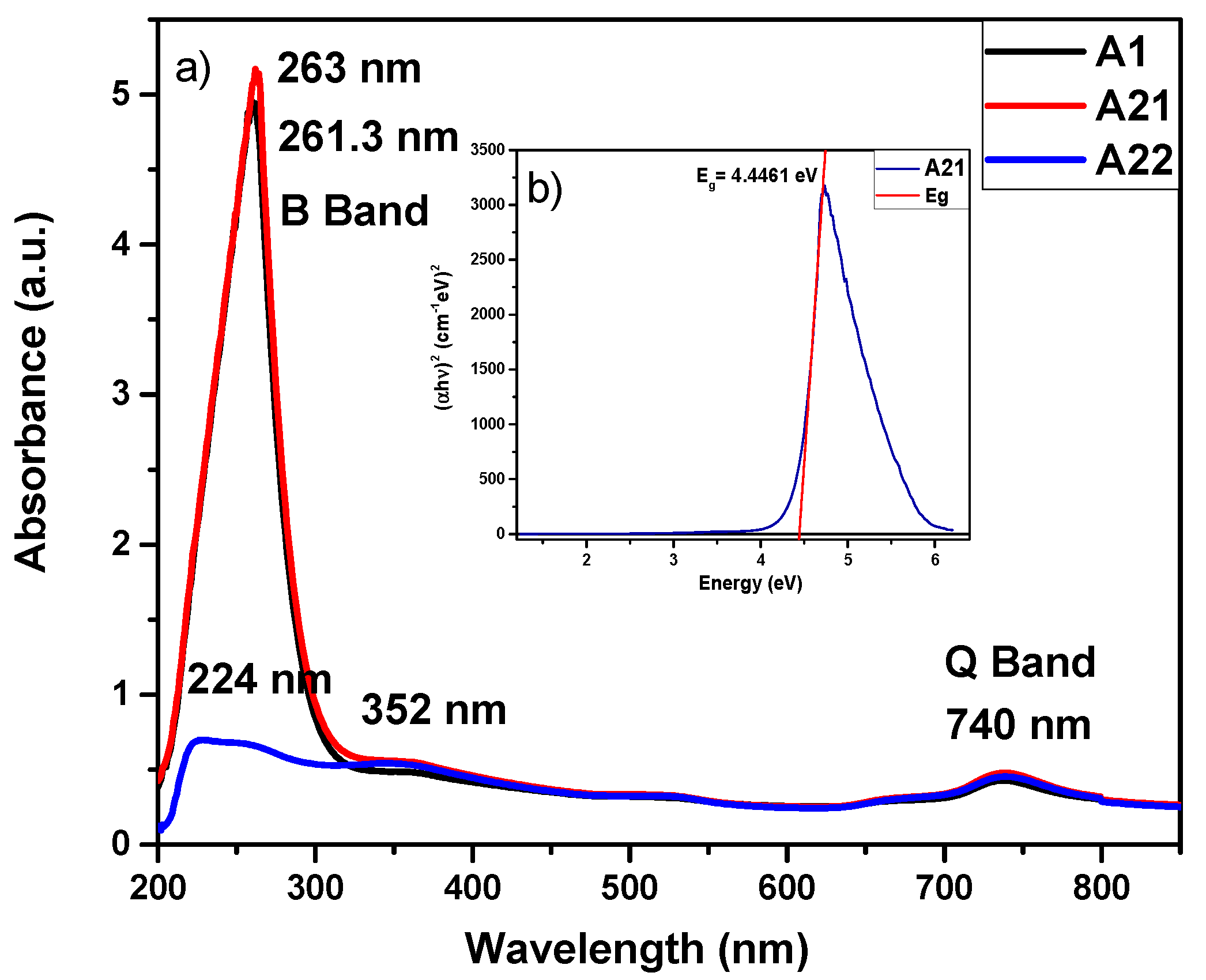

3. Results and discussion

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Mcmurry, J. Polímeros Sintéticos y Biodegradables: Propiedades Físicas; Vol 7a edición; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Autino, J.C.; Romanelli, G.P.; Ruiz, D.M. Introducción a La Química Orgánica. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.T.; Kwok, H.S.; Djurišić, A.B. The optical functions of metal phthalocyanines. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2004, 37, 678–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevim, A.M.; Yenilmez, H.Y.; Aydemir, M.; Koca, A.; Bayir, Z.A. Synthesis, electrochemical and spectroelectrochemical properties of novel phthalocyanine complexes of manganese, titanium and indium. Electrochimica Acta 2014, 137, 602–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayliss, S.M.; Heutz, S.; Rumbles, G.; Jones, T.S. Thin film properties and surface morphology of metal free phthalocyanine films grown by organic molecular beam deposition. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 1999, 1, 3673–3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziminov, A.V.; Ramsh, S.M.; Terukov, E.I.; Trapeznikova, I.N.; Shamanin, V.V.; Yurre, T.A. Correlation dependences in infrared spectra of metal phthalocyanines. Semiconductors 2006, 40, 1131–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbeck, S.; Mack, H. Experimental and Theoretical Investigations on the IR and Raman Spectra for CuPc and TiOPc. University of Tübingen, 2013; 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Shen, Y.; Gu, F.; Tao, J.; Zhang, J. Optical and photoelectric properties of manganese(II) phthalocyanine epoxy derivative. Mater. Lett. 2007, 61, 3086–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, J. Theoretical investigation of the molecular, electronic structures and vibrational spectra of a series of first transition metal phthalocyanines. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2007, 67, 1232–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamam, K.J.; Alomari, M.I. A study of the optical band gap of zinc phthalocyanine nanoparticles using UV–Vis spectroscopy and DFT function. Appl. Nanosci. 2017, 7, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, P.; Zeki Yildiz, S. Substituted manganese phthalocyanines as bleach catalysts: synthesis, characterization and the investigation of de-aggregation behavior with LiCl in solutions. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2019, 45, 687–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günsel, A.; Kandaz, M.; Yakuphanoglu, F.; Farooq, W.A. Extraction of electronic parameters of organic diode fabricated with NIR absorbing functional manganase phthalocyanine organic semiconductor. Synth. Met. 2011, 161, 1477–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, S. Técnicas de depósito y caracterización de películas delgadas. 2009, (Cvd). 6–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sobre, I.; Anuncio, E. Thin Films. Available online: https://nanocienciainforma.files.wordpress.com/2012.jpg.

- Nieto, K. Propiedades físicas de películas nanoestructuradas de semiconductores CdS, In2S3 y CdSe obtenidas por la técnica de baño químico. Cent Investig y Estud Av. 2018, 1, 100. [Google Scholar]

- Albella, J.M. Propiedades Y Aplicaciones.

- Günsel, A.; Kandaz, M.; Yakuphanoglu, F.; Farooq, W.A. Extraction of electronic parameters of organic diode fabricated with NIR absorbing functional manganase phthalocyanine organic semiconductor. Synth. Met. 2011, 161, 1477–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranston, R.R.; Lessard, B.H. Metal phthalocyanines: thin-film formation, microstructure, and physical properties. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 21716–21737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seoudi, R.; El-Bahy, G.S.; El Sayed, Z.A. Ultraviolet and visible spectroscopic studies of phthalocyanine and its complexes thin films. Opt. Mater. 2006, 29, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Wang, K.; Han, Y.; Yao, Y.; Gao, P.; Huang, C.; Zhang, W.; Xu, F. Synthesis, structure, and optical properties of manganese phthalocyanine thin films and nanostructures. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2017, 27, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günsel, A.; Kocabaş, S.; Bilgiçli, A.T.; Güney, S.; Kandaz, M. Synthesis, photophysical and electrochemical properties of water–soluble phthalocyanines bearing 8-hydroxyquinoline-5-sulfonicacid derivatives. J. Lumin. 2016, 176, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdoğmuş, A.; Akinbulu, I.A.; Nyokong, T. Synthesis and electrochemical properties of new cobalt and manganese phthalocyanine complexes tetra-substituted with 3,4-(methylendioxy)-phenoxy. Polyhedron 2010, 29, 2352–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshell, J. FT Raman spectrum and band assignments for metal–free phthalocyanine (H2Pc). Mater. Sci. Res. India 2010, 7, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neamtu, M.; Nadejde, C.; Brinza, L.; Dragos, O.; Gherghel, D.; Paul, A. Iron phthalocyanine-sensitized magnetic catalysts for BPA photodegradation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tackley, D.R.; Smith, W.E. Phthalocyanines: structure and vibrations. 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abood, M.A.; Ai-essa, I.M. The effect of conductive polymer on the Structural and Surface Morphology Analysis of NiPcTs:PEDOT:PSS Blend. 2017, 104, 45814–45817. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, M.T.; Aadim, K.A.; Hassan, E.K. Structural and Surface Morphology Analysis of Copper Phthalocyanine Thin Film Prepared by Pulsed Laser Deposition and Thermal Evaporation Techniques. Adv. Mater. Phys. Chem. 2016, 06, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touka, N.; Benelmadjat, H.; Boudine, B.; Halimi, O.; Sebais, M. Copper phthalocyanine nanocrystals embedded into polymer host: Preparation and structural characterization. J. Assoc. Arab. Univ. Basic Appl. Sci. 2013, 13, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Ding, X.; Chen, L.; Wu, Y.; Liu, L.; Addicoat, M.; Irle, S.; Dong, Y.; Jiang, D. Two-dimensional artificial light-harvesting antennae with predesigned high-order structure and robust photosensitising activity. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, J.; Ahmad, I.; Jung, M.; Seo, J.-M.; Yu, S.-Y.; Noh, H.-J.; Kim, Y.H.; Shin, H.-J.; Baek, J.-B. Two-dimensional amine and hydroxy functionalized fused aromatic covalent organic framework. Commun. Chem. 2020, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nahass, M.M.; Atta, A.A.; El-Sayed, H.E.A.; El-Zaidia, E.F.M. Structural and optical properties of thermal evaporated magnesium phthalocyanine (MgPc) thin films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2008, 254, 2458–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Liu, S.; Lu, Q.; Sun, H.; Xiu, Z. BiVO4/cobalt phthalocyanine (CoPc) nanofiber heterostructures: Synthesis, characterization and application in photodegradation of methylene blue. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 53402–53406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Zou, T.; Gong, H.; Wu, Q.; Qiao, Z.; Wu, W.; Wang, H. Cobalt phthalocyanine nanowires: Growth, crystal structure, and optical properties. Cryst. Res. Technol. 2016, 51, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).