1. Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM) is a major type of primary brain tumors, which has the characteristics of strong necrosis, endothelial cell proliferation, strong invasion and rapid angiogenesis. GBM has reached the highest level (Level 4) in the classification of brain tumors by the World Health Organization (WHO) [

1,

2,

3]. Surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy are classic therapeutic methods for GBM patients. However, they could only improve the survival duration and survival rate of patients to some extent [

4]. Poor prognosis and significant neurologic morbidity of GBM causes high social and medical burden [

5]. Temozolomide (TMZ), lomustine and carmustine are commonly adopted chemotherapeutic drugs but mostly followed with the modest benefits recurrence [

6]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to identify new effective therapeutic options for glioblastoma.

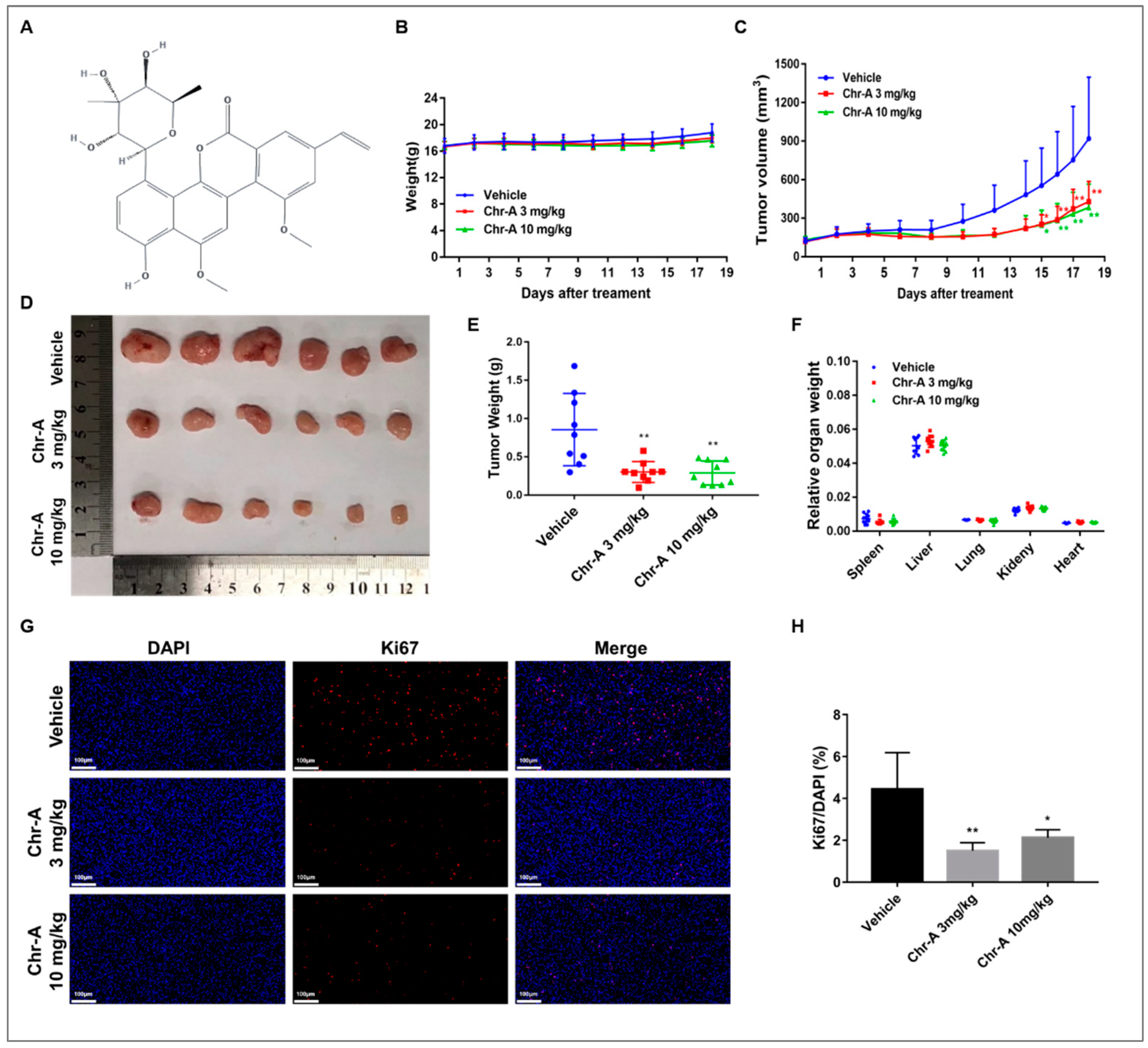

Chrysomycin A (Chr-A,

Figure 1A), a kind of glycoside with benzonaphthopyranone, was first discovered in 1955 [

7,

8]. In recent years, progress has been made in production conditions and preparation of Chr-A, which has contributed to its future new drug development process [

9,

10]. It has been reported that Chr-A has antibiotic, anti-tumor, anti-tuberculosis, and anti-neuroinflammation properties [

11,

12,

13]. Previously, the inhibitory effect and possible mechanisms of Chr-A on proliferation, migration and invasion towards U251 and U87 glioblastoma cells has been investigated [

14]. However, there is few reports on the mechanism of Chr-A exerting anti-glioblastoma effect in vivo.

Apoptosis, a programmed cell death initiated under physiological and pathological conditions, serves as a key entry point for many therapeutic strategies of cancer [

15,

16]. In tumor cells, apoptosis is usually inhibited, allowing indefinite proliferation of malignant tumor cells. Among the complex mechanisms regulating apoptosis, Bcl-2 family members, P53 and caspases are novel targets therapies towards multiple cancers [

17]. Herein, we investigated the regulation and possible mechanisms of Chr-A on apoptosis of human glioblastoma cells both in vivo and in vitro.

2. Results

2.1. Chr-A suppressed the tumorigenicity in human glioma U87 xenografts nude mice

To evaluate the antitumor potential of Chr-A in vivo, we established a xenograft model by inoculating nude mice with U87-MG cells and 3 or 10 mg/kg Chr-A were given by intraperitoneal injection per day for 18 days. During Chr-A treatment, no obvious weight loss or abnormal behavior was observed (

Figure 1B). Whereas, the tumor weight and tumor volume of were significantly decreased with administration of Chr-A (

Figure 1C-E). Furthermore, no mortality or significant changes in the colors and textures of vital organs, including the liver, kidney, heart, lung and spleen, and no significant differences in the relative organ weights were observed in the Chr-A treatment groups compared to vehicle group (

Figure 1F). In addition, to determine the inhibitory effect of Chr-A on proliferation of glioblastoma cells in nude mice, Ki67 immunofluorescence staining was performed. The number of Ki67 positive cells (red fluorescent) of Chr-A treatment groups, which indicated the marker of cell proliferation, decreased significantly compared with vehicle group (

Figure 1G,H). Thus, Chr-A showed an inhibitory role for viability and proliferation in human glioblastoma cells leading to tumor regression of nude mice xenografts.

2.2. Chr-A regulates Akt/GSK-3β signaling pathway of glioblastoma cells in human glioma U87 xenografts nude mice

To figure out the underlying mechanisms of Chr-A against GBM, RNA-seq analysis of tumor tissues of BALB/c Nude mice was performed first, and there were 992 differential expression genes (DEGs) regulated by Chr-A (

Supplementary Table S1). In addition, a total of 5299 genes were obtained by searching the GeneCard, DrugBank Online and Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) (

Supplementary Table S2). Further analysis showed there were 383 overlapped genes of Chr-A-related targets and glioblastoma-related targets, which were regarded as potential therapeutic targets of Chr-A against glioblastoma in the present study (

Figure 2A,

Supplementary Table S3). Subsequently, the underlying pharmacological mechanisms of Chr-A against glioblastoma could be enlightened by GO and KEGG enrichment analysis. The top 20 significant GO terms including biological process (BP), cellular component (CC) and molecular function (MF) were shown in

Figure 2B. The significant signaling pathways of KEGG enrichment analysis were mainly involved in the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, Wnt signaling pathway, Apoptosis and so on (

Figure 2C). Abnormal regulation of PI3K-Akt and Wnt signaling pathway which could work together by the communication between Akt and GSK-3β facilitates GBM progression. Our results showed that Chr-A significantly downregulated Akt, p-Akt, p-GSK-3β of glioblastoma cells in nude mice and influenced the expression of GSK-3β with no significant difference (

Figure 2D,E). Besides, Chr-A remarkably reduced the expression of slug and MMP2, the downstream of Wnt signaling pathway resulted from Akt/GSK-3β signal modulation (

Figure 2F,G). Thus, Chr-A may exert anti-glioblastoma activity in vivo via Akt/GSK-3β signaling pathway.

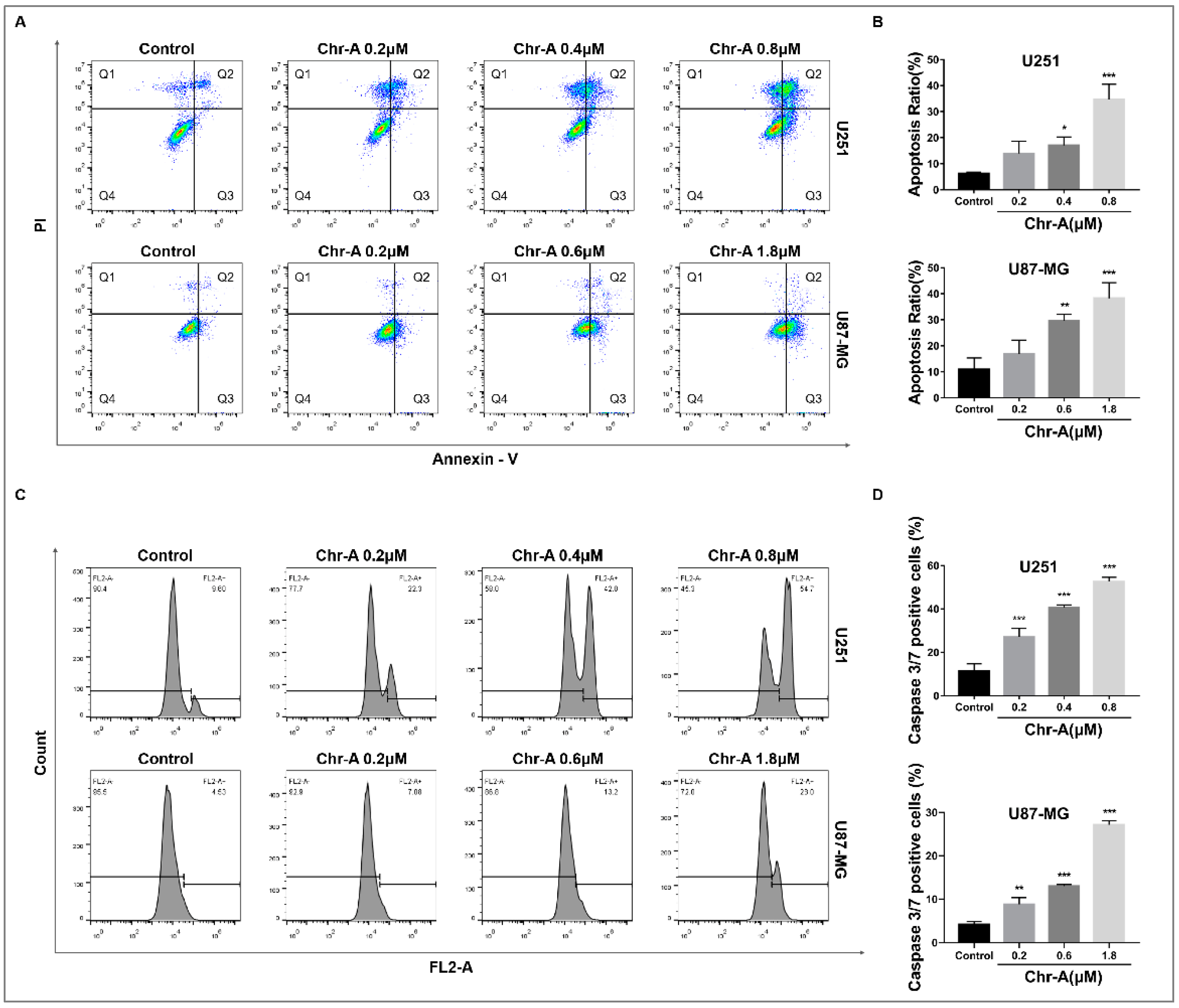

2.3. Chr-A induces apoptosis of U251 and U87-MG cells

Annexin Ⅴ/PI staining was used to detect the percent of living cells (Q4), early apoptotic cells (Q3) and late apoptotic cells (Q2), and necrotic cells (Q1) of glioblastoma cells after 48h of Chr-A treatment. Compared with the control group, the apoptosis rate (Q3+Q2) of U251 and U87-MG cells remarkably increased in Chr-A groups as the concentration increasing (

Figure 3A,B). Caspase 3 and Caspase 7 are important executive factors for cell apoptosis, whose activity reflects the occurrence ofcell apoptosis to a certain extent. The results showed that Chr-A significantly increased caspase 3/7 activity in U251 and U87-MG cells with different concentrations of Chr-A compared with control group (

Figure 3C,D).

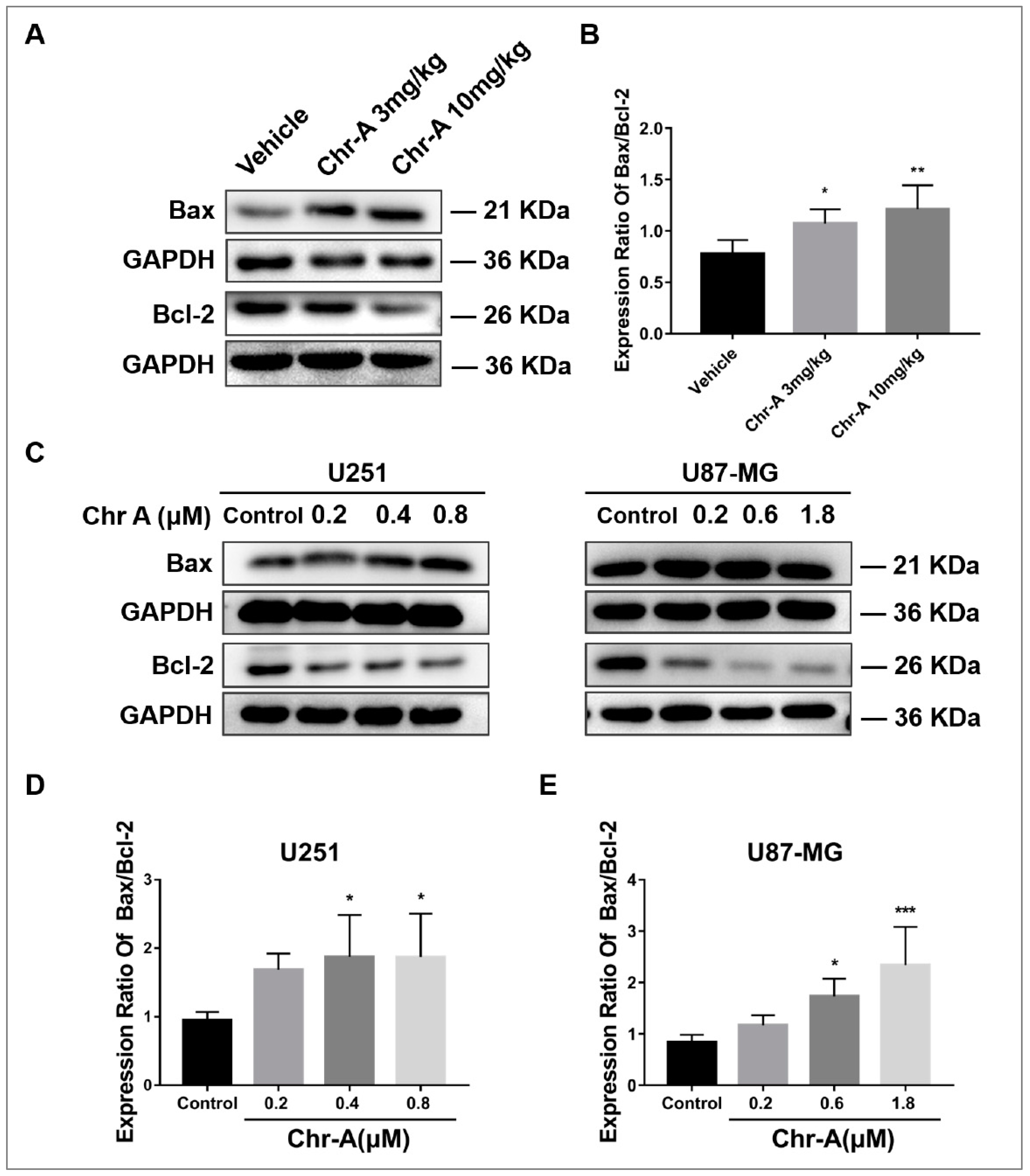

2.4. Chr-A increases ratio of Bax to Bcl-2 of glioblastoma cells in vivo and in vitro

Members of Bcl-2 family proteins are indispensable for apoptosis, among which Bax functions as a pro-apoptotic protein, Bcl-2 serves as anti-apoptotic proteins. To maintain physiological homeostasis, Bax and Bcl-2 keep a balance regulating cell metabolism. Western blotting showed that Chr-A treatment caused remarkable elevated ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 of neuroglioma cells in xenografts nude mice (

Figure 4A,B). Meanwhile, compared with control group, Chr-A treatment for 48h significantly heightened ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 in U251 cells and U87-MG cells (

Figure 4C,D,E). Together, these results indicated that Chr-A regulates the balance between Bax and Bcl-2 inducing apoptosis of glioblastoma cells in vivo and in vitro.

2.5. Chr-A activates caspase cascade reaction of glioblastoma cells in vivo and in vitro

Apoptosis is mainly regulated by two pathways: mitochondrial apoptosis pathway and death receptor apoptosis pathway, both of which couldn’t come into play without the activation of caspase cascade reaction including caspase 3 and caspase 7. The results showed that Chr-A treatment caused remarkable elevated ratio of caspase 9/caspase 9, as well as the expression ratio of cleaved caspase 3/caspase 3, cleaved caspase 7/caspase 7 of glioblastoma cells in tumor tissues, which are executives in downstream of apoptotic process (

Figure 5A,B). Also, the same regulation was detected on U251 and U87-MG cells with Chr-A treatment for 48h in vitro (

Figure 5C,D,E). In summary, our data suggested that the inhibition of glioblastoma by Chr-A is due to activation of caspase leading to apoptosis.

3. Discussion

Glioblastoma, characterized with great aggressiveness, poor prognosis and short-term survival, is the most primary and lethal tumor of the central nervous system. Surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy were widely adopted therapeutic approaches to glioblastoma but the survivals of patients were not improved ideally [

2,

6]. TMZ was an oral chemotherapy commonly used for patients with glioblastoma containing nonnegligible adverse effects [

20], and among the patients, 55% of which showed resistance to TMZ [

21]. Thus, it’s of great significance to develop effective therapeutics for glioblastoma.

Chr-A has a group of benzonaphthopyranone glycosides, suggested to possess antitumor activity [

8]. And it did show inhibitory effect to human U251 and U87-MG glioblastoma cells in vitro [

14]. In the current study, we verified the antitumor activity of Chr-A in vivo using human U87-MG cells xenograft glioblastoma model, from which we found that intraperitoneal administration of both 3 and 10 mg/kg Chr-A suppressed the tumorigenicity. Importantly, there is no obvious change in weight, behavior and organs of mice during administration, thus indicating Chr-A has effect against GBM with low toxicity to mouse as the published reports have concluded [

8]. Besides, Chr-A has no influence on the lysis of red blood cells [

22]. To explore the in-depth molecular characterization of signaling pathway, we conducted RNA-seq analysis of tumor tissue obtained from xenograft glioblastoma in nude mice. 383 intersection genes between differentially expressed genes screened from RNA-seq analysis and glioblastoma-related targets collected from various forms database were regarded as the core genes for Chr-A against glioblastoma in the study. According to the KEGG enrichment analysis, we finally focused on apoptosis, PI3K-AKT and Wnt signaling pathways to explore the mechanism that Chr-A against glioblastoma.

Apoptosis is an ordered physiological process taking places in cells under pathological conditions. Targeting apoptosis-related proteins plays an important role in medicines exerting certain therapeutic effect on glioblastoma [

23,

24]. It is the altered expression ratio of multiple pro-and anti-apoptotic proteins rather than the absolute quantity of those modulates cell death. Bcl-2 family proteins are indispensable in apoptotic process. Bax, a member of Bcl-2 family, could accelerate cytochromes to release into the cytoplasm resulting in activating Caspase-3 during apoptosis promotion. Bcl-2, anti-apoptosis protein, favors intracellular Ca2+ release as it encodes mitochondrial outer membrane proteins [

25,

26]. Mitochondrial membrane permeability gets impaired when Bax/Bcl-2 ratio becomes unbalanced, followed by Cyt C and AIF release and caspase-9 activation, further caspase-3/7 activation [

27]. As shown in our results, Chr-A treatment stimulated apoptosis heightening ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 and activating caspases involving caspase 3, caspase 7 and caspase 9 of glioblastoma cells in vivo and in vitro, and thus confirming the enrichment analysis that Chr-A leads to tumor regression by apoptosis-promoting.

Abnormal activation of the PI3K-Akt and Wnt signaling pathway was closely related to cytoskeletal rearrangement, metabolism, apoptosis, and angiogenesis in GBM [

28,

29]. Interestingly, the interaction between Akt and GSK-3β builds a bridge between PI3K-Akt and Wnt signaling pathway to make it possible to regulate oncogenesis synergistically: Akt could not only recognize the accumulation of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3) provoked by PI3K to stimulate downstream of classic PI3K-Akt signal [

30], but phosphorylate GSK-3β at Ser9 site [

31], further regulating β-catenin localization in Wnt signal followed with affecting downstream including slug and MMP2 to influence tumor growth [

32,

33]. In our study, remarkable downregulation of p-Akt and p-GSK-3β in Chr-A group was observed with Chr-A treatment, and their downstream, slug and MMP2, were also showed a significant decrease. Taken our previous work in vitro [

14] together, Chr-A may function against glioblastoma via apoptosis regulation by Akt/GSK -3β signaling pathway confirming the KEGG enrichment analysis above.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

Chr-A was provided by Prof. Hua-Wei Zhang (Zhejiang University of Technology). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) and fetal bovine serum (FBS, Cat# 164210-50) for cell culture were purchased from Gibco BRL (Grand Island, NY, USA) and Procell (Wuhan, China) respectively. Anti-Bax antibody (50599-2-Ig) and anti-Bcl-2 antibody (12789-1-AP) were purchased from Proteintech (Manchester, United Kingdom). Anti-Caspase 3 antibody (9662), anti-Cleaved Caspase 3 antibody (9664), anti-Caspase 7 antibody (12827), anti-Cleaved Caspase 7 antibody (8438), anti-Caspase 9 antibody (9508), anti-Cleaved Caspase 9 antibody (20750), anti-Akt antibody (9272), anti-p-Akt antibody (9271), anti-GSK-3β antibody (9315), anti-p-GSK-3β antibody (9323), anti-slug antibody (9585), anti-MMP2 antibody (87809) and anti-GAPDH antibody (5174) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverley, CA, USA).

4.2. Antitumor activity in mouse xenograft tumor model

Female BALB/c Nude mice (6-7 week) were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China; Animal certification number was SCXK(Jing) 2021–0006), weighing 14-17 g. All animal care and experimental procedures regarding the animals were approved by the ethic committees of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College. The ethical number was 00005431. Briefly, U87-MG glioblastoma cells in logarithmic phase (1×107 cells per mouse) were subcutaneously implanted into the right flanks of the mice. When the tumor volume was approximately at 100-150 mm3, the mice were randomly divided into three groups (n=9) and then injected intraperitoneally with vehicle (normal saline with 0.1% Tween 80) or with Chr-A (3 or 10 mg/kg) once per day for another 18 days. The dosage of Chr-A was based on our previous study. The tumor volume was measured by Vernier caliper and calculated using the following formula: tumor volume (mm3) = 0.5 × (length) × (width)2. At the end of the experiment, all the mice sacrificed by cervical dislocation for obtaining the tumor tissues and the tumor weights and organ weights were recorded.

4.3. Ki67 staining by immunofluorescence

The expression of Ki67 in tumor tissues was assayed by immunofluorescence, which was detected by Wuhan Servicebio technology. Briefly, tumor tissues were fixed in 4% PFA overnight at 4 °C and embedded in paraffin. Then, tumor tissues sections were incubated with anti-Ki67 primary antibody (1: 200) at 4 °C overnight after blocking and permeabilization. After washing with PBS, the sections were incubated with Cy3 labeled secondary antibody at room temperature for 2 h. Nuclei were stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 10 min at room temperature. All images were acquired using fluorescence microscope and fluorescence intensity was analyzed using the image processing package Image J/Fiji.

4.4. Chr-A-related target identification by RNA-seq

RNA-seq was detected by Shanghai Kangcheng biology. The brief methods are as follows: the total RNA of U87-MG xenografts in the nude mice was extracted and sequenced by Illumina NovaSeq 6000 Sequencer. The image processing and base classification were carried out by Solexa pipeline version 1.8 (off line base caller software, version 1.8) software, and the differential genes regulated by Chr-A were further analyzed and screened [

18,

19].

4.5. Glioblastoma-related target collection and analysis

GeneCard (

https://www.genecards.org/, accessed on 23 November 2021), DrugBank Online (

https://go.drugbank.com/, accessed on 23 November 2021) and the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (

https://omim.org/, accessed on 23 November 2021) were used to obtain glioblastoma-related targets by searching “glioblastoma” on the platform. After discarding the duplicate targets, the glioblastoma-related genes were described. The Metascape database (

https://metascape.org/, accessed on 23 November 2021) was used for GO and KEGG enrichment analysis. Metascape is an online tool for gene annotation and analysis resources. It is often used to process enrichment analysis of Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways.

4.6. Glioblastoma cells culture

U251 and U87-MG cells were gained from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Beijing, China). Cells were cultured with DMEM containing 10% FBS in an incubation at 37℃ constantly maintaining a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

4.7. Apoptosis assay

TransDetect® Annexin V-EGFP/PI Cell Apoptosis Detection Kit (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China) was used to determine the percent of viable cells, early and late apoptotic cells as well as necrotic cells by flow cytometry (BD FACSVerse, San Diego, CA, USA). 1.5 × 105 cells were seeded in each well of 6-well plates for 24 h before replacing the culture media to serum-free DMEM. And 0, 0.2, 0.4, and 0.8 μM Chr-A were added to U251 cells; 0, 0.2, 0.6, and 1.8 μM Chr-A were added to U87-MG cells for 48 h. Then, cells were harvested and processed according to instruction manual of detection kit. Detections were carried out via flowcytometry and the data was analyzed through Flow Jo software (Tristar, CA, USA).

4.8. Caspase 3/7 activity detection

Caspase-3/7 Live-cell Fluorescence Real-time Detection Kit (KeyGenBioTECH, Nanjing, China) was used to assess caspase-3/7 activity. Cells were seeded in 6-well plates for 24 h before replacing the culture media to serum-free DMEM. And 0, 0.2, 0.4, and 0.8 μM Chr-A were added to U251 cells; 0, 0.2, 0.6, and 1.8 μM Chr-A were added to U87-MG cells for 48 h. Then, cells were harvested, washed with PBS, and the Caspase 3/7 activity was determined according to instruction manual of detection reagent. Detections were carried out by flow cytometry (BD Accuri C6, San Diego, CA, USA).

4.9. Western blotting

The total proteins of glioblastoma cells and tissues were extracted with RIPA lysis buffer (ApplyGen, Beijing, China) in an ice water bath. After centrifugation at 12000rpm for 15min, quantification with BCA Protein Assay Kit (Applygen, Beijing, China) was performed. After that, the proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE gel and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Then membranes were blocked by 5% skim milk in TBST for 2 h at room temperature followed by an incubation with primary antibodies at 4℃ overnight. Sequently, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Then ECL hypersensitive luminescence solution was used to visualize the proteins bands. The grayscale value of the bands on the images were analyzed by Image J software.

4.10. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the GraphPad prism7. The results were expressed as mean ± SD. The differences in the groups were analyzed by Ordinary one-way ANOVA Multiple comparisons. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

5. Conclusions

After the research it was apparent that Chr-A has the potential to suppress onco-genesis of glioblastoma, inducing apoptosis through Akt/GSK -3β signaling pathway. However, there are still more aspects needed to be explored and verified as implied by the enrichment analysis, such as cell cycle arrest of the glioblastoma cells and other underlying mechanisms. For the next, we may further study the therapeutic mechanism of Chr-A on glioblastoma and hope to identified some specific targets of Chr-A for the treatment of glioblastoma.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Dong-Ni Liu and Man Liu: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, and Writing original draft. Shan-Shan Zhang, Yu-Fu Shang, and Wen-Fang Zhang: Methodology and Investigation. Fu-Hang Song and Hua-Wei Zhang: Methodology and Resources. Guan-Hua Du: Conceptualization and review & editing. Yue-Hua Wang: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Project administration, and review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was surpported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFC2804205, 2018YFC0311005), CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS, NO. 2021-I2M-1-069), and Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7232299).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the ethic committees of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College (No. 110324201101902783, approved on 11 August 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wirsching, H.G.; Galanis, E.; Weller, M. Glioblastoma. Handb Clin Neurol 2016, 134, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kyriakou, I.; Yarandi, N.; Polycarpou, E. Efficacy of cannabinoids against glioblastoma multiforme: A systematic review. Phytomedicine 2021, 88, 153533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, J.; He, X.; Yu, W.; Chen, Y.; Long, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhu, S.; Liu, Q. p53-targeted lncRNA ST7-AS1 acts as a tumour suppressor by interacting with PTBP1 to suppress the Wnt/beta-catenin signalling pathway in glioma. Cancer Lett 2021, 503, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balca-Silva, J.; Matias, D.; do Carmo, A.; Girao, H.; Moura-Neto, V.; Sarmento-Ribeiro, A.B.; Lopes, M.C. Tamoxifen in combination with temozolomide induce a synergistic inhibition of PKC-pan in GBM cell lines. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015, 1850, 722–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, J.Y.; de Groot, J.F. Treatment of Glioblastoma. J Oncol Pract 2017, 13, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.C.; Ashley, D.M.; Lopez, G.Y.; Malinzak, M.; Friedman, H.S.; Khasraw, M. Management of glioblastoma: State of the art and future directions. CA Cancer J Clin 2020, 70, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Q.; Huang, X.S.; Ishida, K.; Maier, A.; Kelter, G.; Jiang, Y.; Peschel, G.; Menzel, K.D.; Li, M.G.; Wen, M.L.; Xu, L.H.; Grabley, S.; Fiebig, H.H.; Jiang, C.L.; Hertweck, C.; Sattler, I. Plasticity in gilvocarcin-type C-glycoside pathways: discovery and antitumoral evaluation of polycarcin V from Streptomyces polyformus. Org Biomol Chem 2008, 6, 3601–3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, S.I.; Sawa, R.; Iwanami, F.; Nagayoshi, M.; Kubota, Y.; Iijima, K.; Hayashi, C.; Shibuya, Y.; Hatano, M.; Igarashi, M.; Kawada, M. Structures and biological activities of novel 4’-acetylated analogs of chrysomycins A and B. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2017, 70, 1078–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zheng, S.; Gao, X.; Hong, Y.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Xiang, J.; Xie, D.; Song, F.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Sun, X. Mechanochemical preparation of chrysomycin A self-micelle solid dispersion with improved solubility and enhanced oral bioavailability. J Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, H.J.; Lv, S.Y.; Sheng, Y.T.; Wang, H.; Chu, X.H.; Zhang, H.W. Optimization of fermentation conditions and medium compositions for the production of chrysomycin a by a marine-derived strain Streptomyces sp. 891. Prep Biochem Biotechnol 2021, 51, 998–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.T.; Byrne, K.M.; Warnick-Pickle, D.; Greenstein, M. Studies on the mechanism of actin of gilvocarcin V and chrysomycin A. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1982, 35, 545–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, U.; Yoshihira, K.; Highet, R.J.; White, R.J.; Wei, T.T. The chemistry of the antibiotics chrysomycin A and B. Antitumor activity of chrysomycin A. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1982, 35, 1194–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, S.S.; Liu, D.N.; Yang, Y.L.; Wang, Y.H.; Du, G.H. Chrysomycin A Attenuates Neuroinflammation by Down-Regulating NLRP3/Cleaved Caspase-1 Signaling Pathway in LPS-Stimulated Mice and BV2 Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.N.; Liu, M.; Zhang, S.S.; Shang, Y.F.; Song, F.H.; Zhang, H.W.; Du, G.H.; Wang, Y.H. Chrysomycin A Inhibits the Proliferation, Migration and Invasion of U251 and U87-MG Glioblastoma Cells to Exert Its Anti-Cancer Effects. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeyamohan, S.; Moorthy, R.K.; Kannan, M.K.; Arockiam, A.J. Parthenolide induces apoptosis and autophagy through the suppression of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in cervical cancer. Biotechnol Lett 2016, 38, 1251–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.S. Apoptosis in cancer: from pathogenesis to treatment. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2011, 30, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldar, S.; Khaniani, M.S.; Derakhshan, S.M.; Baradaran, B. Molecular mechanisms of apoptosis and roles in cancer development and treatment. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2015, 16, 2129–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazee, A.C.; Pertea, G.; Jaffe, A.E.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L.; Leek, J.T. Ballgown bridges the gap between transcriptome assembly and expression analysis. Nat Biotechnol 2015, 33, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Kim, D.; Pertea, G.M.; Leek, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat Protoc 2016, 11, 1650–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, A.; Marinelli, O.; Morelli, M.B.; Iannarelli, R.; Amantini, C.; Russotti, D.; Santoni, G.; Maggi, F.; Nabissi, M. Isofuranodiene synergizes with temozolomide in inducing glioma cells death. Phytomedicine 2019, 52, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karachi, A.; Dastmalchi, F.; Mitchell, D.A.; Rahman, M. Temozolomide for immunomodulation in the treatment of glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol 2018, 20, 1566–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaji, M.; Mohan, D.V.; S. , V.J.; Vellekkatt, J.; Ranjit, R.; Sabu, T.; G., D.S.; Santhosh, K.K.; Shankar, L.R.; Ajay, K.R. Anti-microbial activity of chrysomycin A produced by Streptomyces sp. against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. RSC Advances 2017, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlowska, E.; Szczepanska, J.; Szatkowska, M.; Blasiak, J. An Interplay between Senescence, Apoptosis and Autophagy in Glioblastoma Multiforme-Role in Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Perspective. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trejo-Solis, C.; Serrano-Garcia, N.; Escamilla-Ramirez, A.; Castillo-Rodriguez, R.A.; Jimenez-Farfan, D.; Palencia, G.; Calvillo, M.; Alvarez-Lemus, M.A.; Flores-Najera, A.; Cruz-Salgado, A.; Sotelo, J. Autophagic and Apoptotic Pathways as Targets for Chemotherapy in Glioblastoma. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, J.Y.; Park, J.H.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, W.J.; Ha, K.T.; Choi, B.T.; Lee, S.Y.; Shin, H.K. Isolinderalactone regulates the BCL-2/caspase-3/PARP pathway and suppresses tumor growth in a human glioblastoma multiforme xenograft mouse model. Cancer Lett 2019, 443, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, G.; Zhou, X.; Hu, Y.; Shi, S.; Yang, G. Rev-erbalpha Inhibits Proliferation and Promotes Apoptosis of Preadipocytes through the Agonist GSK4112. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, H.; Liu, Y.; Lei, X.; He, P.; Dong, W. Thymoquinone inhibits the proliferation and invasion of esophageal cancer cells by disrupting the AKT/GSK-3beta/Wnt signaling pathway via PTEN upregulation. Phytother Res 2020, 34, 3388–3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhao, P.; Zhao, H.; Gao, W.; Wang, L. Celastrol Suppresses Glioma Vasculogenic Mimicry Formation and Angiogenesis by Blocking the PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Li, W.; Xu, H.; Liu, J.; Ren, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, J.; Ji, T.; Du, G. Sinomenine ester derivative inhibits glioblastoma by inducing mitochondria-dependent apoptosis and autophagy by PI3K/AKT/mTOR and AMPK/mTOR pathway. Acta Pharm Sin B 2021, 11, 3465–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahcheraghi, S.H.; Tchokonte-Nana, V.; Lotfi, M.; Lotfi, M.; Ghorbani, A.; Sadeghnia, H.R. Wnt/beta-catenin and PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathways in Glioblastoma: Two Main Targets for Drug Design: A Review. Curr Pharm Des 2020, 26, 1729–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, S.; Jin, R.; Xu, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, G. Pyrvinium pamoate regulates MGMT expression through suppressing the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway to enhance the glioblastoma sensitivity to temozolomide. Cell Death Discov 2021, 7, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Yang, J.; Lei, S.; Wang, W. SKA3 promotes glioblastoma proliferation and invasion by enhancing the activation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling via modulation of the Akt/GSK-3beta axis. Brain Res 2021, 1765, 147500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Liu, D.; Sun, X.; Yang, K.; Yao, J.; Cheng, C.; Wang, C.; Zheng, J. CDX2 inhibits the proliferation and tumor formation of colon cancer cells by suppressing Wnt/beta-catenin signaling via transactivation of GSK-3beta and Axin2 expression. Cell Death Dis 2019, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Chr-A promotes tumor regression and suppresses proliferation of glioblastoma cells in nude mice xenografts. (A) Molecular formula of Chr-A, (B) Changes in body weight during Chr-A administration period, (C) Changes in tumor volumes during Chr-A administration period, (D) Image of xenograft tumors, (E) Tumor weights at the end of the experiment, (F) Relative organ weights at the end of the experiment, n=9; (G) Representative fluorescent micrographs of immunofluorescent staining with Ki67 antibody, (H) Statistical analysis of the percentage of Ki67 positive cells, white scale bars represent 100 μm, n=3. The data were presented as mean ± SD, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. vehicle group.

Figure 1.

Chr-A promotes tumor regression and suppresses proliferation of glioblastoma cells in nude mice xenografts. (A) Molecular formula of Chr-A, (B) Changes in body weight during Chr-A administration period, (C) Changes in tumor volumes during Chr-A administration period, (D) Image of xenograft tumors, (E) Tumor weights at the end of the experiment, (F) Relative organ weights at the end of the experiment, n=9; (G) Representative fluorescent micrographs of immunofluorescent staining with Ki67 antibody, (H) Statistical analysis of the percentage of Ki67 positive cells, white scale bars represent 100 μm, n=3. The data were presented as mean ± SD, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. vehicle group.

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Analysis of potential targets and validation of possible mechanism for Chr-A against glioblastoma. (A) Venn diagram of targets; (B) Top 20 significant GO terms, including BP, CC, and MF; (C) Top 20 significant KEGG pathways, (D and E) Chr-A decreased expression of GSK-3β, p-GSK-3β, Akt, p-Akt of glioblastoma cells in tumor tissues, (F and G) Chr-A downregulated slug and MMP2 of glioblastoma cells in tumor tissues. The data were presented as mean ± SD (n=5-6), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. vehicle group.

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Analysis of potential targets and validation of possible mechanism for Chr-A against glioblastoma. (A) Venn diagram of targets; (B) Top 20 significant GO terms, including BP, CC, and MF; (C) Top 20 significant KEGG pathways, (D and E) Chr-A decreased expression of GSK-3β, p-GSK-3β, Akt, p-Akt of glioblastoma cells in tumor tissues, (F and G) Chr-A downregulated slug and MMP2 of glioblastoma cells in tumor tissues. The data were presented as mean ± SD (n=5-6), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. vehicle group.

Figure 3.

Figure 3. Chr-A increases apoptosis rate and caspase 3/7 activity in U251 and U87-MG cells. (A and B) Chr-A increased apoptosis rate of U251 and U87-MG cells, (C and D) Chr-A activated caspase 3/7 activity of U251 and U87-MG cells. The data were presented as mean ± SD (n=3), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. vehicle group.

Figure 3.

Figure 3. Chr-A increases apoptosis rate and caspase 3/7 activity in U251 and U87-MG cells. (A and B) Chr-A increased apoptosis rate of U251 and U87-MG cells, (C and D) Chr-A activated caspase 3/7 activity of U251 and U87-MG cells. The data were presented as mean ± SD (n=3), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. vehicle group.

Figure 4.

Figure 4. Chr-A increases the expression ratio of Bax to Bcl-2 to regulate apoptosis in vivo and in vitro. (A and B) Chr-A increases expression ratio of Bax to Bcl-2 of glioblastoma cells in tumor tissues, n=6, (C, D and E) Chr-A increases expression ratio of Bax to Bcl-2 in U251 and U87-MG cells, n=4. The data were presented as mean ± SD, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. vehicle group or control group.

Figure 4.

Figure 4. Chr-A increases the expression ratio of Bax to Bcl-2 to regulate apoptosis in vivo and in vitro. (A and B) Chr-A increases expression ratio of Bax to Bcl-2 of glioblastoma cells in tumor tissues, n=6, (C, D and E) Chr-A increases expression ratio of Bax to Bcl-2 in U251 and U87-MG cells, n=4. The data were presented as mean ± SD, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. vehicle group or control group.

Figure 5.

Chr-A activates caspase 3/ 7/ 9 to mediate apoptosis of glioblastoma cells in vivo and in vitro. (A and B) Chr-A increases the expression ratio of cleaved caspase3/ caspase3, cleaved caspase7/ caspase7, cleaved caspase9/ caspase9 of glioblastoma cells in tumor tissues, n=6, (C, D and E) Chr-A increases the expression ratio of cleaved caspase3/ caspase3, cleaved caspase7/ caspase7, cleaved caspase9/ caspase9 in U251 and U87-MG cells, n=3-4.The data were presented as mean ± SD, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. vehicle group or control group.

Figure 5.

Chr-A activates caspase 3/ 7/ 9 to mediate apoptosis of glioblastoma cells in vivo and in vitro. (A and B) Chr-A increases the expression ratio of cleaved caspase3/ caspase3, cleaved caspase7/ caspase7, cleaved caspase9/ caspase9 of glioblastoma cells in tumor tissues, n=6, (C, D and E) Chr-A increases the expression ratio of cleaved caspase3/ caspase3, cleaved caspase7/ caspase7, cleaved caspase9/ caspase9 in U251 and U87-MG cells, n=3-4.The data were presented as mean ± SD, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. vehicle group or control group.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).