Submitted:

18 April 2023

Posted:

19 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

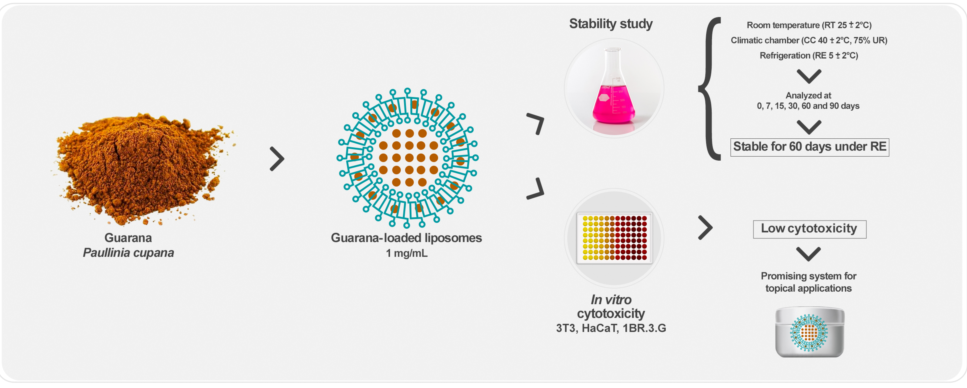

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation and characterization of guarana-loaded liposomes

2.3. Physicochemical stability study of guarana-loaded liposomes

2.4. Culture of 3T3, HaCaT and 1BR.3.G Cell Lines

2.5. Analysis of liposome interference with cell viability assays

2.6. Cytotoxicity Assays

2.7. Statistical analysis

3. Results and discussion

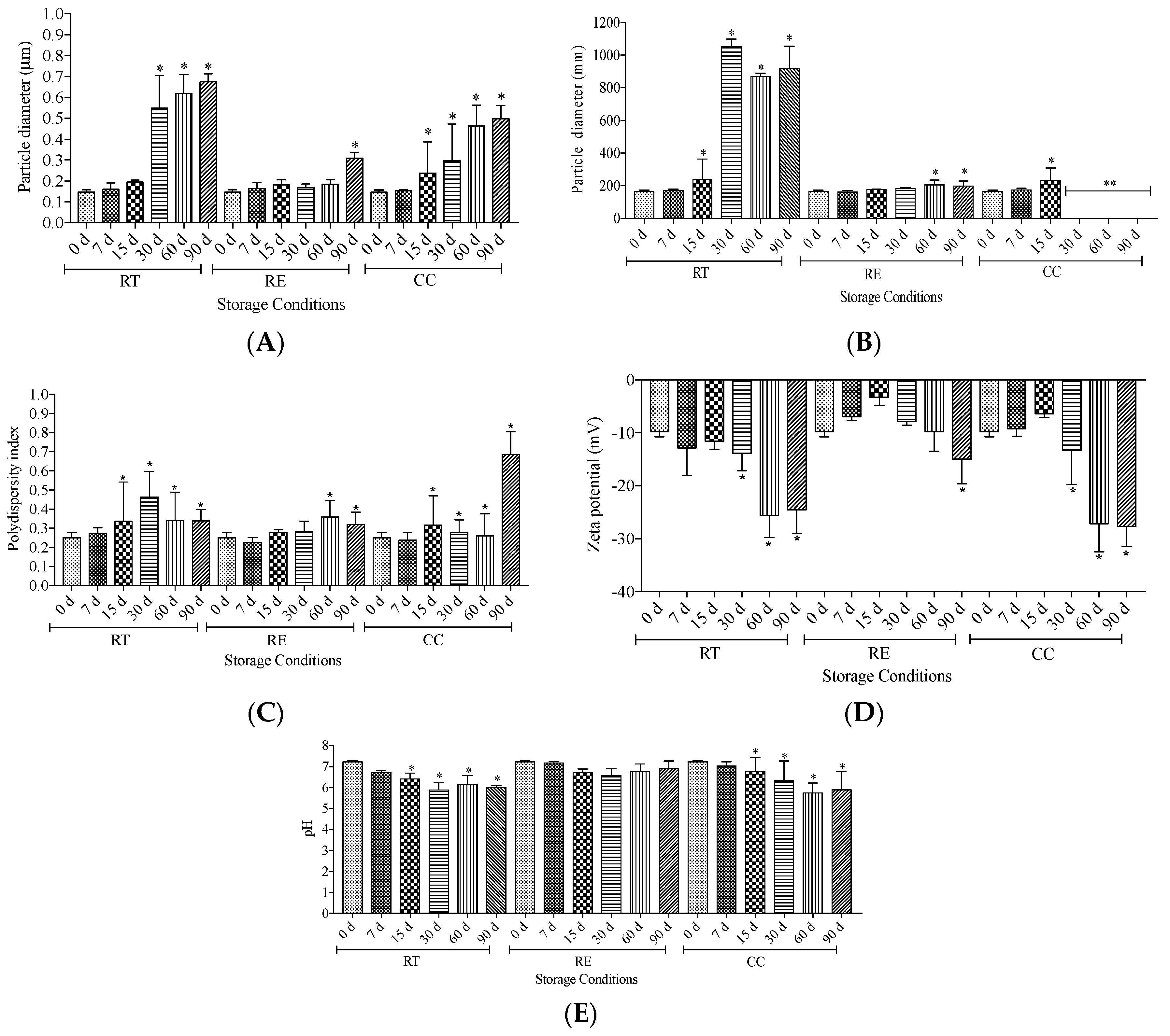

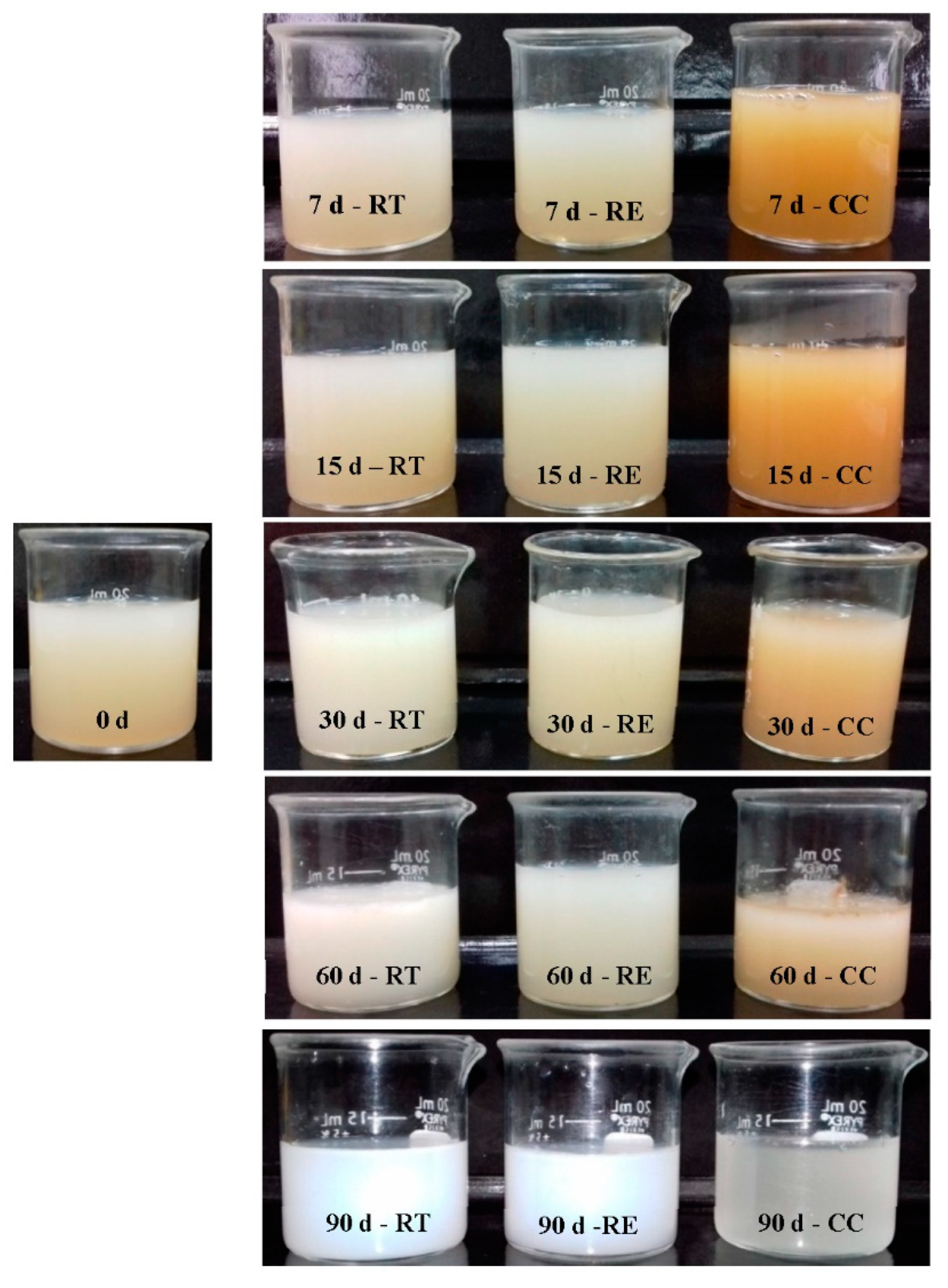

3.1. Stability study of guarana-loaded liposomes

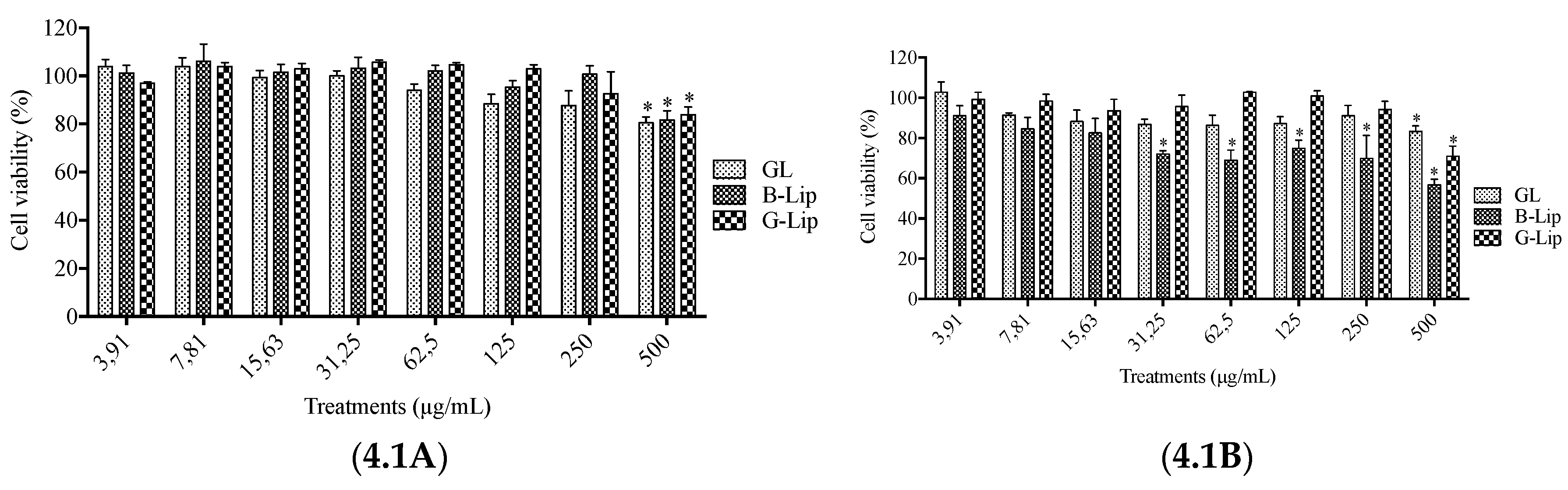

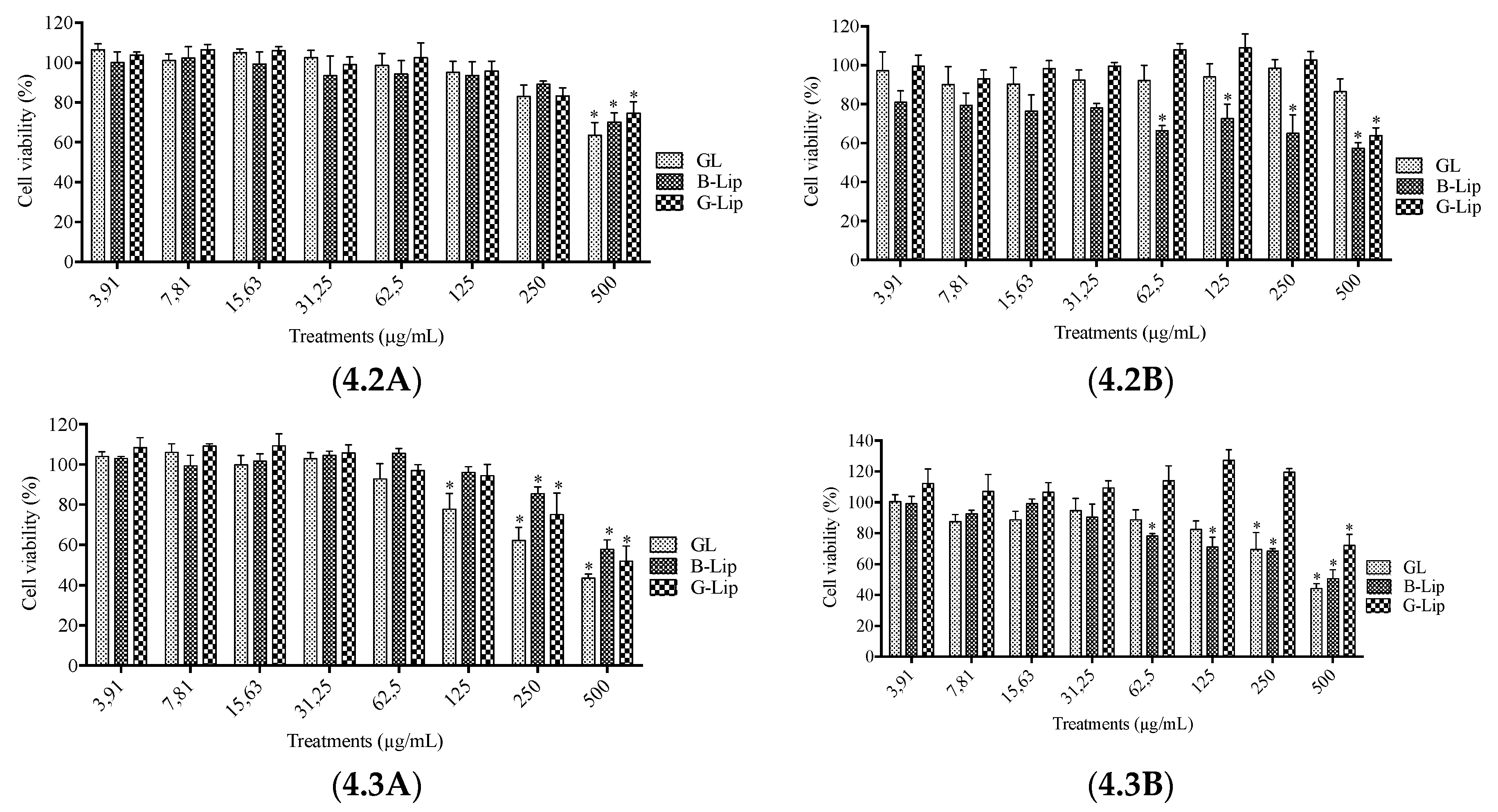

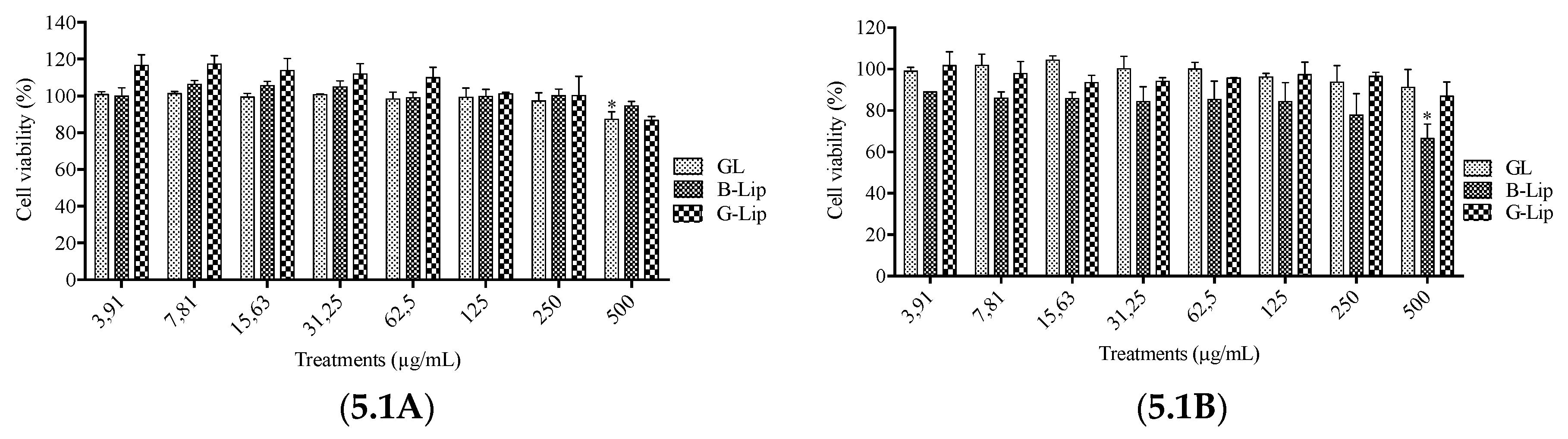

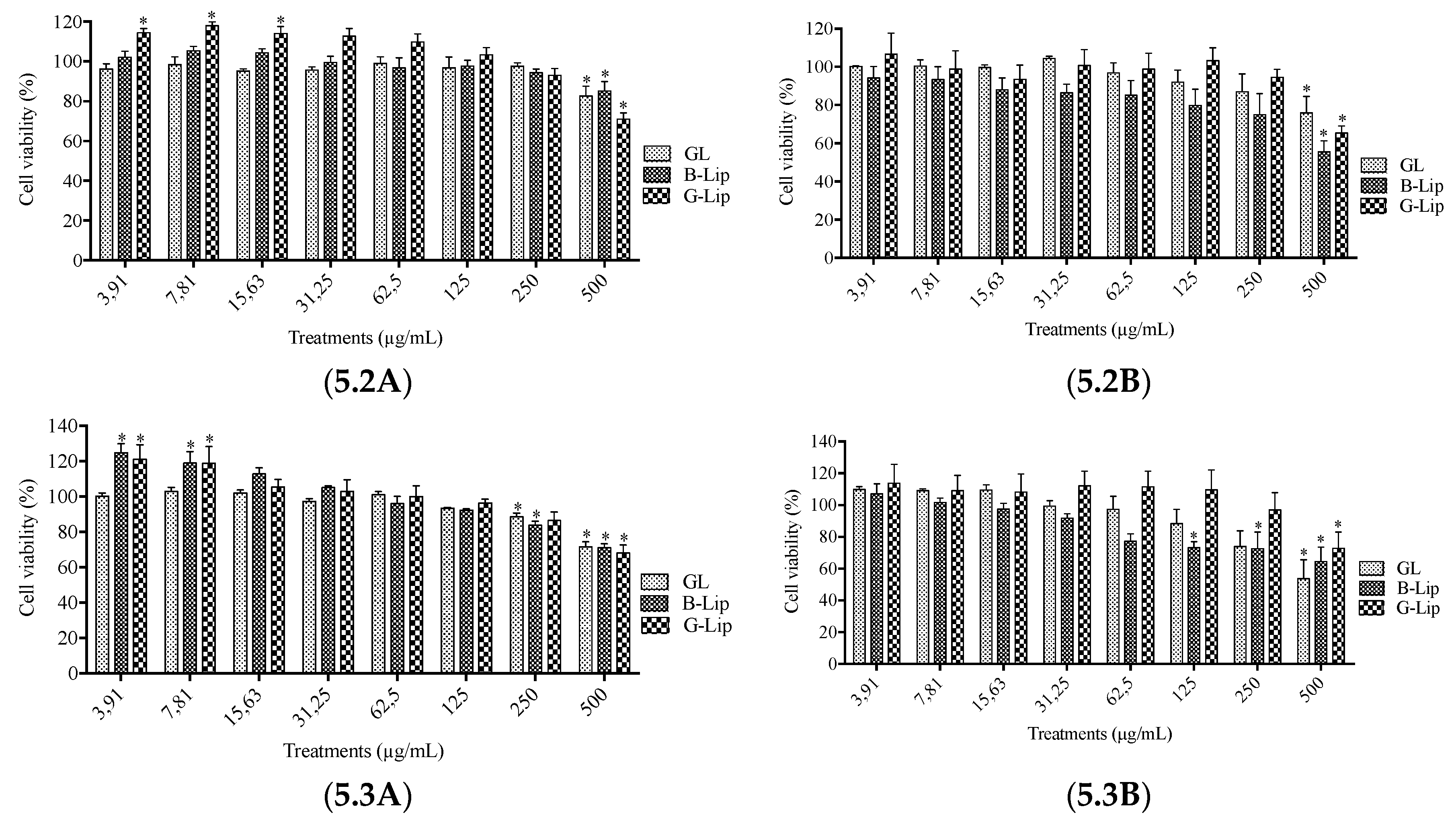

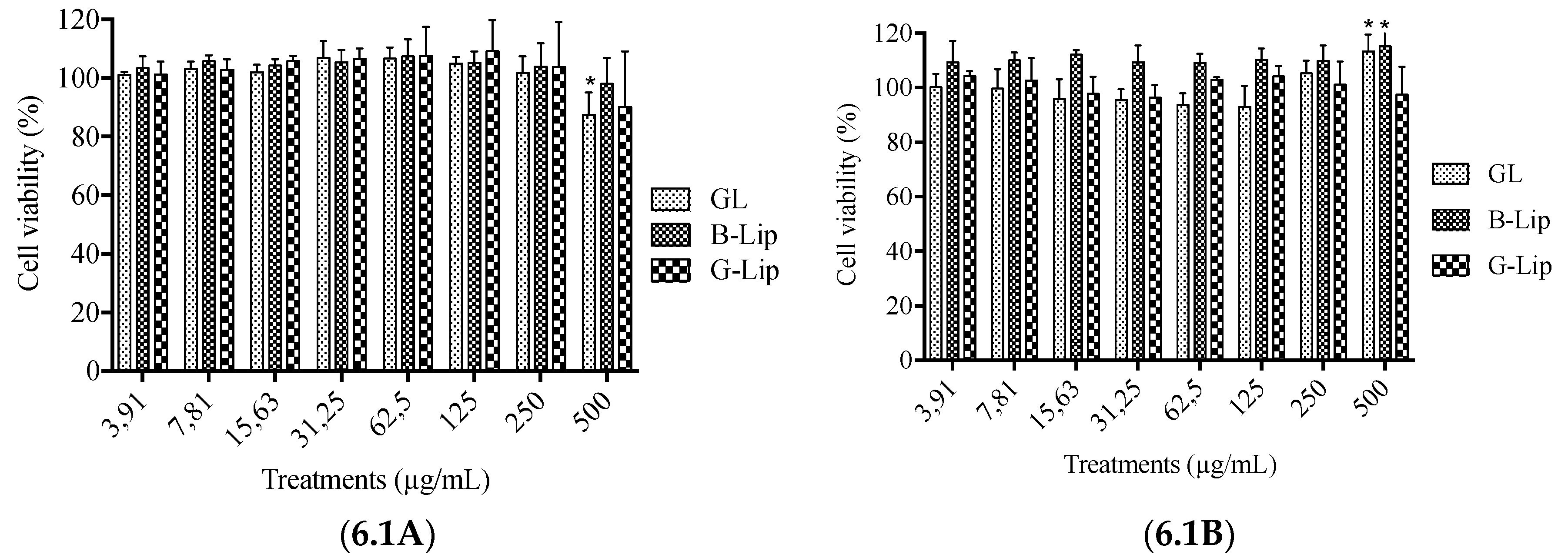

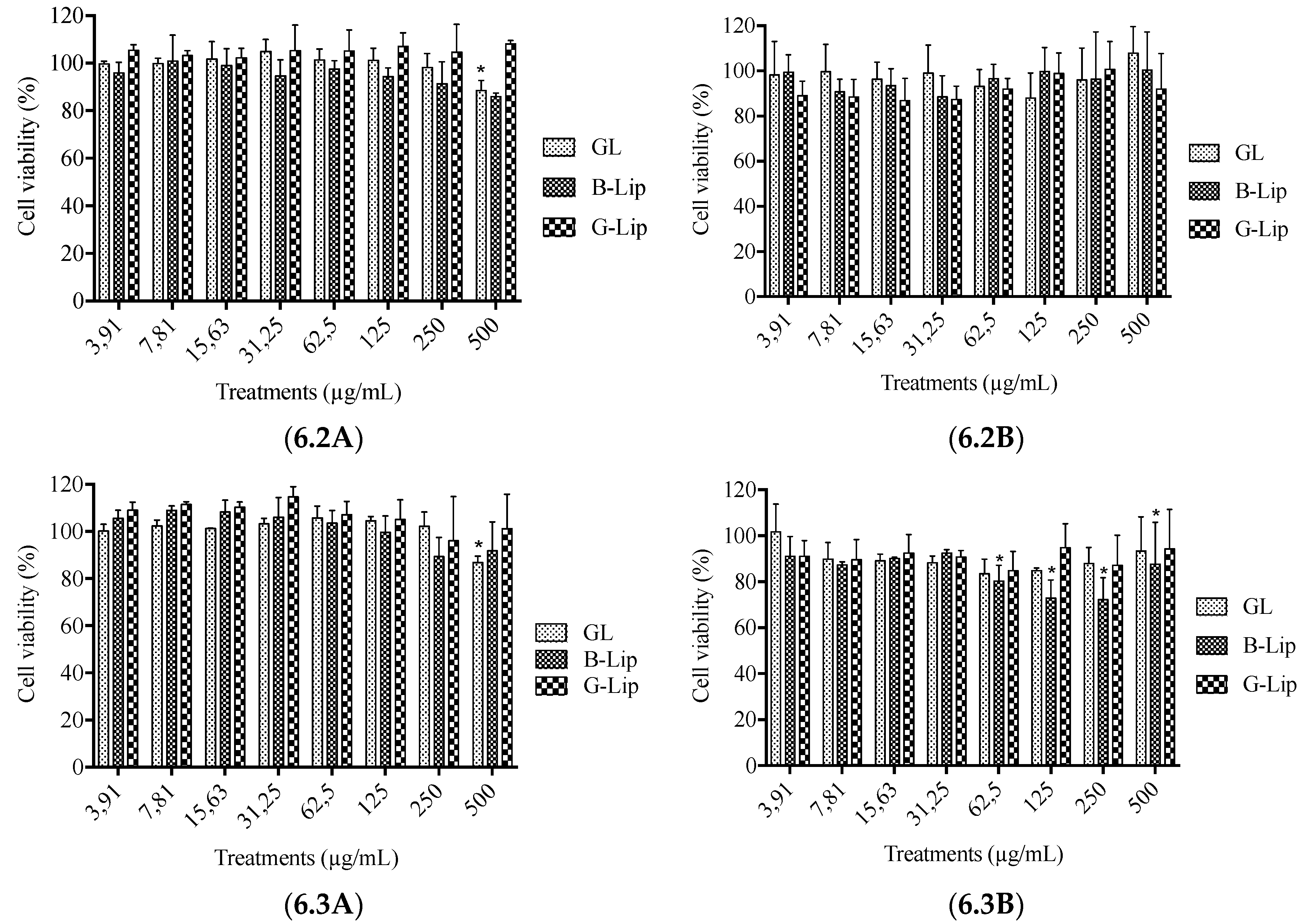

3.2. Cytotoxicity studies

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest statement

Disclosure statement

References

- Watkins, R., Wu, L., Zhang, C., Davis, R.M., Xu, B. 2015. Natural product-based nanomedicine: recent advances and issues, Int J Nanomedicine. 10, 6055-6074. [CrossRef]

- Calixto, J.B. 2019. The role of natural products in modern drug discovery, An Acad Bras Cienc. 91, e20190105. [CrossRef]

- Fidan, O., Ren, J., Zhan, J. 2022. Engineered production of bioactive natural products from medicinal plants, World J Tradit Chin Med. 8, 59-76. [CrossRef]

- Daudt, R.M., Emanuelli, J., Külkamp-Guerreiro, I.C., Pohlmann, A.R., Guterres, S.S. 2013. A nanotecnologia como estratégia para o desenvolvimento de cosméticos, Cienc. Cult. 65(3), 28-31. [CrossRef]

- Marques, L.L.M., Ferreira, E.D.F., De Paula, M.N., Klein, T., Palazzo de Mello, J.C. 2019. Paullinia cupana: a multipurpose plant – a review, Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 29, 77–110. [CrossRef]

- Bonifácio, B.V., Silva, P.B., Ramos, M.A., Negri, K.M., Bauadb, T.M. Chorillii, M. 2014. Nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems and herbal medicines: a review, Int J Nanomedicine. 9, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Zorzi, G., Carvalho, E., Poser, G.V., Teixeira, H.F. 2015. On the use of nanotechnology-based strategies for association of complexes matrices from plant extracts, Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 25(4), 426-436. [CrossRef]

- Vanti, G. 2021. Recent strategies in nanodelivery systems for natural products: a review, Environ. Chem. Lett. 19, 4311-4326. [CrossRef]

- Kaul, S., Gulati., N., Verma., D., Mukherjee, S., Nagaich, U. 2018. Role of Nanotechnology in Cosmeceuticals: A Review of Recent Advances. Journal of Pharmaceutics. 19, Article ID 3420204. [CrossRef]

- Khezri, K., Saeedi, M., Dizaj, S.M. 2018. Application of nanoparticles in percutaneous delivery of active ingredients in cosmetic preparations, Biomed Pharmacother. 106, 1499-1505. [CrossRef]

- Aziz, Z.A.A., Mohd-Nasir, H., Ahmad, A., Setapar, S.H.M., Peng, W.L., Chuo, S.C., Khatoon, A., Umar, K., Yaqoob, A.A., Ibrahin, M.N.M. 2019. Role of Nanotechnology for Design and Development of Cosmeceutical: Application in Makeup and Skin Care, Front. Chem. 7. [CrossRef]

- Ferraris, C., Rimicci, C., Garelli, S., Ugazio, E., Battaglia, L. 2021. Nanosystems in Cosmetic Products: A Brief Overview of Functional, Market, Regulatory and Safety Concerns, Pharmaceutics 13, 1408. [CrossRef]

- Dimer, F.A., Friedrich, R.B., Beck, R.C.R., Guterres, S.S. 2013. Impactos na nanotecnologia na saúde: Produção de medicamentos, Quim. Nova. 36(10), 1520-1526. [CrossRef]

- Mali, A.D., Bathe, R.S. 2015. Updated review on nanoparticles as drug delivery systems, IJAPBS. 4, 18-34.

- Ahmadi, A.H.R., Bishe, P.L.N., Nilforoushzadeh, M.A., Zare, S. 2016. Liposomes in Cosmetics, J Skin Stem Cell. 3(3), e65815. [CrossRef]

- Nsairat, H., Khater, D., Sayed, U., Odeh, F., Bawab, A.A., Alshaer, W. 2022. Liposomes: structure, composition, types, and clinical applications, Heliyon, 8(5), e09394. [CrossRef]

- Raj, S., Jose, S., Sumod, U.S., Sabitha, M. 2012. Nanotechnology in cosmetics: Opportunities and challenges. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 4, 186-193. [CrossRef]

- Soni, V., Chandel, S., Jain, P., Asati, S. 2016. Role of liposomal drug- delivery system in cosmetics, in Nanobiomaterials in Galenic Formulations and Cosmetics, ed A. M. Grumezescu (William Andrew Publishing), 93–120. [CrossRef]

- Shokri, J. 2017. Nanocosmetics: benefits and risks. Bioimpacts. 7(4), 207-208. [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Reyes, E.D., Perea-Flores, M.J., Davila-Ortiz, G., Lee,Y., De Mejia, E.G.2020. Development, Characterization and Use of Liposomes as Amphipathic Transporters of Bioactive Compounds for Melanoma Treatment and Reduction of Skin Inflammation: A Review, Int J Nanomedicine.15, 7627-7660.

- SCCS (Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety) (2012). Guidance on the Safety Assessment of Nanomaterials in Cosmetics. Available on: SCCS/1484/12: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/scientific_committees/consumer_safety/ docs/sccs_s_005.pdf.

- SCENIHR (Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks) Risk Assessment of Products of Nanotechnologies, 2009 [Last accessed on 2019]. Available on: http://www.ec.europa.eu/health/ph_risk/committees/04_scenihr/docs/scenihr_o_023.pdf.

- UE, 2010: EP and Council of the EU, 2010. Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. O.J.L 276/33.

- Pietrzykowski, T. 2021. Ethical Review of Animal Research and the Standards of Procedural Justice: A European Perspective, Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, 18, 525-534. [CrossRef]

- Burden, N., Creton, S., Weltje, L., Maynard, S.K., Wheeler, J.R. 2014. Reducing the number of fish in bioconcentration studies with general chemicals by reducing the number of test concentrations, Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 70(2), 442-445. [CrossRef]

- Piersma, A.H., Ezendam, J. Luijten, M., Muller, J.J., Rorije, E., Van Der Ven, L.T., Van Benthem, J. 2014. A critical appraisal of the process of regulatory implementation of novel in vivo and in vitro methods for chemical hazard and risk assessment, Crit Rev Toxicol. 44(10), 876-894. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, R. Beken, S., Da Chlebus, M., Ellis, G., Griesinger, C., De Jonghe, S., Manou, I., Mehling, A., Reisinger, K., Rossi, L.H., Benthem, J.V., Laan, J.W.V.D., Weissenhorn, R., Sauer, U.G. 2015. Knowledge sharing to facilitate regulatory decision-making in regard to alternatives to animal testing: Report of an EPAA workshop, Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 73(1), 210-26. [CrossRef]

- Rouquié, D., Heneweer, M., Botham, J., Ketelslegers, H., Markell, L., Pfister, T., Steiling, W., Strauss, V., Hennes, C. 2015. Contribution of new technologies to characterization and prediction of adverse effects, Crit Rev Toxicol. 45(2), 172-183. [CrossRef]

- Russell, W. M. S., & Burch, R. L. (1959). The principles of humane experimental technique. Methuen.

- Morales, M.M. 2008. Métodos alternativos à utilização de animais em pesquisa científica: mito ou realidade? Cienc. Cult. On-line version ISSN 2317-6660, 60(2), 33-36.

- Tannenbaum, J., Bennett, T.B. 2015. Russell and Burch’s 3Rs Then and Now: The Need for Clarity in Definition and Purpose, J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 54 (2), 120–132. PMCID:PMC4382615.

- Atroch, A.L., Filho, F.J.N. 2018. Guarana—Paullinia cupana Kunth var. sorbilis (Mart.) Ducke. Exotic Fruts, 225-236. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.V., Metzner, B.S. 2010. Paullinia cupana: revisão da matéria médica, Rev. homeopatia. 73, 1-17.

- Antonelli-Ushirobira, T.M., Kameshima, E.N., Gabriel, M., Audi, E.A., Marques, L.C., Mello, J.C.P. 2010. Acute and subchronic toxicological evaluation of the semipurified extract of seeds of guaraná (Paullinia cupana) in rodents, Food Chem Toxicol. 48, 1817-1820. [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt, L.S., Machado, D.C., Machado, M.M., Dos Santos, G.F.F., Algarve, T.D., Marinowic, D.R., Ribeiro, E.E., Soares, F.A.A., Barbisan, F., Athayde, M.L., Cruz, I.B.M. 2013. The protective effects of guaraná extract (Paullinia cupana) on fibroblast NIH-3T3 cells exposed to sodium nitroprussid. Food Chem Toxicol. 53, 119-125. [CrossRef]

- Yonekura, L., Martins, C.A., Sampaio, G.R., Monteiro, P.M., César, L.A.M., Mioto, B.M., Mori, C.S., Mendes, T.M.N., Ribeiro, M.L., Arçari, D.P., Torres, E.A.F.D. 2016. Bioavailability of catechins from guaraná (Paullinia cupana) and its effect on antioxidant enzymes and other oxidative stress markers in healthy human subjects, Food Funct. 13(7), 2970-2978. [CrossRef]

- Torres, E.A.F.S., Pinaffi-Langley, A.C.C., Figueira, M.S., Cordeiro, K.S., Negrão, L.D., Soares, M.J., Da Silva, C.P., Alfino, M.C.Z., Sampaio, G.R., De Camargo, A.C. 2021. Effects of the consumption of guarana n human heath: A narrative review, Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 21, 272-295. [CrossRef]

- .

- Basile, A., Ferrara, L., Pezzo, M.D., Mele, G., Sorbo, S., Bassi, P., Montesano, D. 2005. Antibacterial and antioxidant activities of ethanol extract from Paullinia cupana. Mart, J. Ethnopharmacol. 102, 32–36. [CrossRef]

- Majhenic, L., Kerget, M.S., Knez, E.Z. 2007. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of guarana seed extracts, Food Chem. 104, 1258-1268. [CrossRef]

- Portella, R.L., Barcelos, R.P., Da Rosa, E.J.F., Ribeiro, E.E., Cruz, I.B.M., Suleiman, L., Soares, F.A.A. 2013. Guaraná (Paullinia cupana Kunth) effects on LDL oxidation in elderly people: an in vitro and in vivo study, Lipids Health Dis. 12, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, E., Godoy, J.S.R., Bonfim-Mendonça, P.S., De Mello, J.C.P., Svidzinski, T.I.E. Gasparetto, A., Maciel, S.M. 2015. In vitro effect of Paullinia cupana (guaraná) on hydrophobicity, biofilm formation, and adhesion of Candida albicans to polystyrene, composites, and buccal epithelial cells, Arch Oral Bio. 60, 471–478. [CrossRef]

- Klein, T., Longhini, R., Bruschi, M.L., De Mello, J.C.P. 2015. Microparticles containing guaraná extract obtained by spray-drying technique: development and characterization, Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 25, 292–300. [CrossRef]

- Arantes, L.P, Machado M.L, Zamberlan D.C, Silveira T.L, Silva T.C, Cruz B.M, et al. Mechanisms involved in anti-aging effects of guarana (Paullinia cupana) in Caenorhabditis elegans. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2018; 51(9). PubMed PMID: 29972429.

- Boasquívis, P. F., Silva, G. M. M., Paiva, F. A., Cavalcanti, R. M., Nunez, C. V., & de Paula Oliveira, R. (2018). Guarana (Paullinia cupana) Extract Protects Caenorhabditis elegans Models for Alzheimer Disease and Huntington Disease through Activation of Antioxidant and Protein Degradation Pathways. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2018, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Roggia, I., Dalcin, A.J.F., Ourique, A.F., Da Cruz, I.B.M., Ribeiro, E.E., Mitjans, M., Vinardell, M.P., Gomes, P. 2020. Protective effect of guarana-loaded liposomes on hemolytic activity, Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 187:110636. [CrossRef]

- Aldhahrani A. Protective effects of guarana (Paullinia cupana) against methotrexate-induced intestinal damage in mice. Food Sci Nutr. 2021 May; 9(7). PubMed PMID: 34262701.

- Machado, K.N., Barbosa, A.De P., De Freitas, A.A., Alvarenga, L.F., De Pádua, R.M., Faraco, A.A.G., Braga, F.C., Viana-Soares, C.D., Castilho, R.O. TNF-α inhibition, antioxidant effects and chemical analysis of extracts and fraction from Brazilian guaraná seed poder. Food Chemistry. v.355, p. 129563, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Reigada, I.; Kapp, K.; Maynard, C; Weinkove, D.; Valero, M.S.; Langa, E.; Hanski, L.; Gómez-Rincón, C. Alterations in Bacterial Metabolism Contribute to the Lifespan Extension Exerted by Guarana in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1986. [CrossRef]

- Marques, L.L.M., Ribeiro, F.M., Nakamura, C.V., Simianato, A.S., Andrade, G., Ziwlinski, A.A.F., Carollo, C.A., Da Silva, D.B., De Oliveira, A.G., De Mello, J.C.P. Metabolomic profiling and correlations of supercritical extracts of guarana, Natural Product Research, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Peirano, R.I., Achterberg, V., Dusing, H.J., Akhiani, M., Koop, U., Jaspers, S., Kruger, A., Schwengler, H., Hamann, T., Wenck, H., Stab, F., Gallinat, S.B.T. 2011. Dermal penetration of creatine from a face-care formulation containing creatine, guarana and glycerol is linked to effective antiwrinkle and antisagging efficacy in male subjects, J Cosmet Dermatol. 10(4), 273-81. [CrossRef]

- Marchei, E., Orsi, D., Guarino, C., Donato, S., Pacifici, R., Pichini, S. 2013. Measurement of iodide and caffeine content in cellulite reduction cosmetic products sold in the European Market, Anal. Methods. 5, 376-383. [CrossRef]

- Silva, W.G. Rovellini, P., Fusari, P., Venturini, S. 2015. Guaraná - Paullinia cupana, (H.B.K): Estudo da oxidação das formas em pó e em bastões defumados Guaraná, Revista de Ciências Agroveterinárias. (edição on-line) Lages, 14(2), 235-241.

- Mertins, O., Sebben, M., Pohlmann, A., Da Silveira, N. 2005. Production of soybean phosphatidylcholine chitosan nanovesicles by reverse phase evaporation: a step by step study, Chem Phys Lipids. 138, 29-37. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.B., Rigo, L.A., Rosa, L.D., Gressler, L.T., Zimmermann, C.E.P., Ourique, A.F., Silva, A.S., Miletti, L.C., Beck, R.C.R., Monteiro, S.G. 2014. Liposomes produced by reverse phase evaporation: in vitro and in vivo efficacy of diminazene aceturate against Trypanosoma evansi, Parasitology. 141, 761-769. [CrossRef]

- Roggia, I., Dalcin, A.J.F., De Souza, D., Machado, A.K., De Souza, D.V., Da Cruz, I.B.M., Ribeiro, E.E., Ourique, A.F., Gomes, P. Guarana: Stability-Indicating RP-HPLC method and safety profile using microglial cells. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. V.94, p. 103629, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Klein, T., Longhini, R., Palazzo De Mello, J.C. 2012. Development of an analytical method using reversed-phase HPLC-PDA for a semipurified extract of Paullinia cupana var. sorbilis (guaraná), Talanta, 88, 502-506. [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, D.R., Morán, C.M., Mitjans, M., Martínez, V., Pérez, L., Vinardel, M.P. 2013. New cationic nanovesicular systems containing lysine-based surfactants for topical administration: Toxicity assessment using representative skin cell lines, Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 83, 33–43. [CrossRef]

- Mosmann, T. 1983. Rapid colorimetric assay to cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays, J. Immunol. Methods. 65, 55-63. [CrossRef]

- Borenfreund, E., Puerner, J. 1985. Toxicity determined in vitro by morphological alterations and neutral red absorption, Toxicol. Lett. 24, 119-124. [CrossRef]

- Laouini, A., Jaafar-Maalej, C., Limayem-Blouza, I., Sfar, S., Charcosset, C., Fessi, H. 2012. Preparation, Characterization and Applications of Liposomes: State of the Art, J. Colloid Sci. Biotechnol. 1, 147–168. [CrossRef]

- Bozzuto, G., Molinari, A. 2015. Liposomes as nanomedical devices, Int J Nanomedicine. 10, 975–999. [CrossRef]

- Alavi, M., Karimi, N., Safaei, M. 2017. Application of Various Types of Liposomes in Drug Delivery Systems, Adv Pharm Bull. 7(1), 3-9. [CrossRef]

- Neves, M.T., Dos Santos, F.R., Gonçalves, D.J.R., Fernandes, J.G., Justino, H.F.M., Júnior, B.R.C.L., Vieira, E.N.R. 2021. Use of liposome technology in the encapsulation of bioactive compounds – Review, J. Eng. Exact Sci. 07(04), 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Heurtault, B., Saulnier, P., Pech, B., Proust, J.E., Benoit, J.P. 2003 Physico-chemical stability of colloidal lipid particles, Biomaterials, 24, 4283–4300. [CrossRef]

- Karn, P.R., Parkl, H.J., Hwangl, S.J. 2013. Characterization and stability studies of a novel liposomal cyclosporin A prepared using the supercritical fluid method: comparison with the modified conventional, Int J Nanomedicine. 8, 365–377. [CrossRef]

- Batista, C.M., De Carvalho, C.M.B., Magalhães, N.S.S. 2007. Lipossomas e suas aplicações terapêuticas: Estado da arte, Rev. Bras. Cienc. Farm. 43(2), 167-179. [CrossRef]

- Roy, A., Saha, D., Mandal, P.S., Mukherjee, A., Talukdar, P. 2016. pH-Gated Chloride Transport by a Triazine-Based Tripodal Semicage, Chem. Eur. 23(6), 1241-1247. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.V., Murthy, M.S., Shete, A.S., Sfurti, S. 2011. Stability Aspects of Liposomes, Ind J Pharm Edu Res. 45(4), 402-413.

- Yo, J.Y., Chuesiang, p., Shin, G.H., Park, H.J. 2021. Post-Processing Techniques for the Improvement of Liposome Stability, Pharmaceutics. 13(7), 1023. [CrossRef]

- Kyi, T.M., Daud, W.R.W., Mohammad, A.B., Samsudin, M.W., Kadhum, A.A.H., Talib, M.Z.M. 2005. The kinetics of polyphenol degradation during the drying of Malaysian cocoa beans, Institute of Food Science & Technology 40, 323-331. [CrossRef]

- Alean, J., Chejne, F., Rojano, B. 2016. Degradation of polyphenols during the cocoa drying process, J. Food Eng. 189, 99-105. [CrossRef]

- Wan Yong, F. 2006. Metabolism of Green Tea Catechins: An Overview, Curr Drug Metab. 7(7), 755-809. doi. 10.2174/138920006778520552.

- Lu, Q., Li, D.C., Jiang, J.G. 2011. Preparation of a Tea Polyphenol Nanoliposome System and Its Physicochemical Properties, J. Agric. Food Chem. 59, 13004–13011. [CrossRef]

- Akbarzadeh, A., Rezaei-Sadabady, R., Davaran, S., Joo, S.W., Zarghami, N., Hanifehpour, Y., Samiei, M., Kouhi, M., Nejati-Koshki, K. 2013. Liposome: classification, preparation, and applications, Nanoscale Res Lett. 8(1), 102. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.K., Couchoud, A., Singh, H. 2009. Comparison of hydrophobic and hydrophilic encapsulation using liposomes prepared from milk fat globule-derived phospholipids and soya phospholipids, Dairy Sci Technol. 89(1), 99-113. [CrossRef]

- Papaccio, F., D’Arino, A., Caputo, S., Bellei, B. 2022. Focus on the Contribution of Oxidative Stress in Skin Aging, Antioxidants. 11(6), 1121. [CrossRef]

- Balboa, E.M., Soto, M.L., Nogueira, D.R., González-López, N., Enma Conde, E., Moure, A., Vinardell, M.P., Mitjans, M., Domínguez, H. 2014. Potential of antioxidant extracts produced by aqueous processing of renewable resources for the formulation of cosmetics, Ind Crop Prod. 58, 104–110. [CrossRef]

- Yamagguti-Sasaki, E., Ito, L.A., Canteli, V.C.D., Ushirobira, T.M.A., Ueda-Nakamura, T., Dias Filho, B.P., Nakamura, C.V., Mello, J.C.P. 2007. Antioxidant Capacity and In Vitro Prevention of Dental Plaque Formation by Extracts and Condensed Tannins of Paullinia cupana, Molecules. 12, 1950-1963. [CrossRef]

- Schimpl, F.C., Da Silva, J.F., Gonçalves, J.F.C., Mazzafera, P. 2013. Guarana: Revisiting a higtly caffeinated plant from the Amazon, J. Ethnopharmacol. 150, 14-31. [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt, L.S., Bortolin, R.C., Kolling, E.A., Schnorr, C.E., Zanotto-Filho, A., Gelain, D.P., Moreira, J.C.F. 2016. Antioxidant Profile Characterization of a Commercial Paullinia cupana (Guarana) Extracts, J. Nat. Prod. Resour. 2(1), 47–52.

- Stone, V., Johnston, H., Schins, R.P. 2009. Development of in vitro systems for nanotoxicology: methodological considerations, Crit Rev Toxicol. 39, 613-626. [CrossRef]

- Kroll, A., Pillukat, M.H., Hahn, D., Schnekenburger, J. 2012. Interference of engineered nanoparticles with in vitro toxicity assays, Arch Toxicol. 86, 1123-1136. [CrossRef]

- Guadagnini, R., Kenzaoui, B.H., Cartwright, L., Pojana, G., Magdolenova, Z., Bilanicova, D., Saunders, M., Juillerat, L., Marcomini, A., Huk, A., Dusinska, M., Fjellsbo, L.M., Marano, F., Boland, S. 2015. Toxicity screenings of nanomaterials: challenges due to interference with assay processes and components of classic in vitro tests, Nanotoxicology. 9, 13-24. [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, D.R., Mitjans, M., Infante, M.R., Vinardell, M.P. 2011. Comparative sensitivity of tumor and non-tumor cell lines as a reliable approach for in vitro cytotoxicity screening of lysine-based surfactants with potential pharmaceutical applications, Int J Pharm. 420, 51– 58. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.P. Análise in vitro da citotoxicidade e proliferação celular em equivalentes de pele humana [In vitro analysis of cytotoxicity and cell proliferation in human skin equivalents] MS thesis. Porto Alegre (RS): Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. 2009.

| Reverse phase evaporation | ||

| Active | Initial (%)* | 90 d (%)** |

| TEOB | Not determined | Not determined |

| TEOF | Not determined | Not determined |

| CAF | 17.02 ± 0.60 | 30.13 ± 0.23 |

| CAT | 74.34 ± 1.93 | 51.65 ± 0.77 |

| EPICAT | 87.53 ± 0.94 | 70.88 ± 2.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).