1. Introduction

ORF7b-like folds have a protein family membership “Non-structural proteins 7b, SARS-like” (IPR021532) (also known as accessory proteins 7b, NS7B, ORF7b, and 7b) from human coronaviruses [

1,

2]. Coronaviruses conserve this sequence, suggesting functional conservation, but it shows no significant homology to human or unrelated proteins [

3,

4]. The only significant similarity detected is a seven-amino acid sequence (IIFWFSL26-32) like a part of the human olfactory receptor 7D4151-157, suggesting a role in viral-induced smell loss. However, the conservation of ORF7b among coronaviruses suggests an important role in the virus’s biology [

5]. No one has yet experimentally defined a well-established 3D model of the ORF7b fold, nor studied its chemical-physical characteristics. A search on RCSB PDB, including Computed Structure Models from AlphaFold DB and ModelArchive, yielded negative results. This means that there are still no reliable models that fully reflect the functional characteristics of these proteins. ORF7b is also an accessory protein for SARS-CoV-2 [UniProtKB Accession: P0DTD8-1]. It comprises 43 amino acid residues [

1], one less than the orthologous SARS-CoV protein [

Table 1]. Both proteins (described here as ORF7b1 and ORF7b2, from SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2), share 85.4% identity and 97.2% sequence similarity, but show a different composition of charged amino acids [

2,

6,

7]. Researchers consider accessory proteins not essential for viral replication but involved in pathogenesis. However, major structural proteins, such as the spike protein, overshadow coronavirus accessory proteins, like ORF7b.

ORF7b2 interacts with very numerous proteins in the human proteome. Indeed, the BioGRID curated project on physical protein interactions between SARS-CoV-2 and the human proteome (BioGRID COVID-19 Coronavirus Curation Project (

https://thebiogrid.org/search.php?search=SARS-CoV-2*&organism=2697049, accessed on June 20, 2025) collects for ORF7b2 1,765 unique interactors that interact experimentally in vivo through 2,986 raw interactions. However, a rough consideration tells us that ORF7b2 might interact with a smaller number of proteins in the human proteome. In fact, not all interactions have the same statistical significance because of the various extraction technologies used by the various laboratories in their cellular models. However, even if the actual interacting proteins were less than half, this would imply that the protein must have a mechanism to reach and interact with these proteins in multiple cellular compartments. An AP-MS analysis (Affinity-Purification-Mass-spectrometry) identified 332 high-confidence protein interactions between SARS-CoV-2 proteins and human proteins [

41]. This article was one of the first to understand that each viral protein could interact with many human different proteins, on average eleven. But, to get an effective physical interaction in a crowded environment such as that of the cell, it is necessary that the interacting molecules have not only an optimal affinity and good quantitative ratios but also similar spatio-temporal characteristics, because they must meet in a certain place at a specific time. This is still a limitation of today’s research.

We recently studied the functional activities of ORF7b2 by interactomic techniques, using only significant and experimentally validated interactions [

9]. The protein is functionally involved in 5,057 functional terms of 15 categories [

9] with biological functions spread in many and different intracellular locations, both membrane and cytosol related. It is involved [

9] in signaling, immunological processes, in the nervous system, in membrane trafficking, in hemostasis, in insulin signaling, on the cell surface, in platelet-related processes, in cell-cell communication, in viral m-RNA translation, in a vast number of human tissues, even very far from the main sites of infection, such as the central nervous system and the male and female reproductive system [

9]. We also discovered multiple interactions between ORF7b2 and other viral and human proteins [

10] (see Excel file S3 in Supplements of [

10] check). The limited spatiotemporal information, however, prevents a precise description of the molecular mechanisms behind these multi-to-one attacks [

11]. One of ORF7b2 peculiarities is that of interacting also in a one-to-one manner with 9 specific human proteins during SARS-CoV-2 liver infection [

12] (see Excel file S3 in Supplements of [

12] check). Each of these nine proteins (ERBB4, GRB2, ITGA7, KCNMB4, LPAR1, ORAI1, RPS4Y2, RSRC1, and VTI1A) shows specific cellular locations and functions. For example, LPAR1 is a G-coupled receptor, located both on the cell surface and in the cytoplasm, but also in the endosome, and RPS4Y2 is a ribosomal protein of the small cytosolic subunit. This highlights the protein’s ability to populate diverse cellular locations with varying chemical-physical properties and interact with structurally distinct proteins. We found ERBB4 and GRB2 among the liver proteins involved in hepatitis B and hepatocellular carcinoma by SARS-CoV-2 infection [

13], from which we inferred ORF7b2 might be involved also in these pathological processes. However, these considerations require further investigation.

The biological success of the virus is based on its exceptional ability to neutralize the host organism’s defenses through its set of proteins. Many of them counteract cellular defensive responses, such as interferon production or immune suppression. The author of an atlas on SARS-CoV-2 proteins [

14] suggested that 21 viral proteins concur in blocking the interferon immune response and among them inserts ORF7b2. Selective interaction of ORF7b2 with the mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) inhibits the RLR signaling pathway, providing a mechanism for suppressing innate immunity and facilitating infection and viral production [

15]. Toft-Bertelsen et al. [

16] identified ORF7b2 as a novel viroporin. This observation suggested that ORF7b2 could act as an ion channel.

In vitro studies on cell-model systems produced many functional hypotheses for ORF7b2, often by invoking a structural similarity with ORF7b1 [

7,

17,

18]. A recent study localized ORF7b2 in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) region [

18]; while older studies located ORF7b1 check in the Golgi compartment [

19,

20,

21] and identified a leucine zipper sequence within its trans-membrane segment [

19]. On this basis, a report has hypothesized that ORF7b2 too is a transmembrane protein localized in the Golgi apparatus [

22] where these two proteins should functionally operate. This suggested a behavioral similarity. However, ORF7b2’s extensive studies reveal a very broad multifunctional activity with many implications for the pathogenesis of infection across many metabolic compartments. Researchers have often compared ORF7b2 to ORF7b1 because of their homologous properties and functions. But, even if ORF7b1 is a protein localized in the Golgi, only indirect evidence links ORF7b2 to this environment. All this suggests we should not consider its activity as confined to Golgi or ER membranes, also considering that its structure must possess peculiar characteristics to allow it to physically interact in vivo with 1,765 different proteins of the human proteome.

The numerous functions of ORF7b2 underscore a multifaceted role in SARS-CoV-2 biology and the pathogenesis of infection. All these features highlighted the need to know the structural organization of this protein. The lack of its three-dimensional structure has led researchers to perform many simulations, often focusing only on the central helical segment. However, because we do not know the complete structural organization of ORF7b1 and ORF7b2, many important structural details are still missing. Focusing only on the central helical segment, while ignoring the structural and functional roles of the long terminal segments, is problematic. These details are important for understanding the correct behavior of this protein in the various environments where it must interact to express a function. It is common in research activities, when faced with a poorly understood protein system, to integrate one’s data with those from homologous proteins. This approach has often prompted to compare ORF7b2 to ORF7b1 [

18,

23,

24,

25] assuming similar localizations and similar cell environments to perform corresponding functions. This approach is guiding the study of these two proteins until today.

However, there have also been recent studies to model the protein structure. According to some authors, ab initio modeling (Robetta) identifies three distinct top-scoring monomer structures for ORF7b2: a) a structure with a central 9-29 helical segment and two mobile and disordered tails; b) a slightly bent central helix with two very flexible tails; c) a structure almost entirely helical and rigid [

26]. These same authors also conducted multiscale molecular dynamics simulations to provide detailed molecular insights into the helix-helix association as homodimers in the POPC bilayer. Their simulations showed the two best homodimer models can have both parallel and antiparallel orientations, even if with some distortions. However, the authors conclude that the functional organization of ORF7b is unclear regarding its orientation (parallel vs. antiparallel).

Other authors have shown that reconstituted ORF7b2 generates a dimer-tetramer equilibrium, but a monomer–dimer–tetramer equilibrium in the presence of reducing agents [

27]. This suggests that the protein may have a tendency to form disulfide bonds, even in vivo. Biophysical measurements, such as NMR, electrophoresis, ultracentrifugation, and infrared spectroscopy have been used to promote their models in media mimicking the membrane environment [

27]. However, the article fails to take into account that the widespread use of deuterated water in the solutions under study compacts and distorts the protein structure. Forgeon et al. hypothesized that ORF7b2 might interfere with those cellular processes that involve a leucine-zipper, forming multimers [

28,

29]. These same authors [

29] have also used the transmembrane helices of PLN (phospholamban) as a static reference model for the structure, showing that an arrangement of the leucine zipper is sterically possible. Because their local AlphaFold software calculated a model showing a distorted leucine-zipper motif, they hypothesized two different ORF7b2 multimeric models. They also showed that their hypotheses were possible in vitro by mimicking a lipid environment. However, the real problem is not so much defining rigid organizational parameters of the structure to find behavioral analogies with similar proteins, but understanding what overall chemical-physical characteristics the protein possesses that, reflecting on its structural organization, allow it to operate in such different environments.

Currently, the most accepted model is the helical one where the central segment (residues 9-29) should favor a trans-membrane insertion (see Figure1S). Therefore, scientists classify ORF7b2 as a trans-membrane protein of the Golgi apparatus, probably at the endoplasmic level. This localization is consistent with its functional role in the immune system and modulation of cellular response. Although ORF7b does not have sites for post-translational modifications (PTMs), nor does it show the signal peptide to enter the Golgi, this does not exclude its function in the Golgi apparatus. It may act as a modulator or regulator of other modified proteins, rather than as a protein that requires chemical modifications to perform its function.

However, ORF7b2 appears to be a traveling protein, not a sedentary protein. A different picture emerges when considering its numerous functions and subcellular locations. The discovery of ORF7b2 functions in different cellular substructures or fluids (Golgi, mitochondria, plasma membrane, seminal liquid) suggests that the protein must have a dynamic role, having to adapt to different cellular needs. This mobility allows the protein to interact with different cellular structures and to perform multiple functions in various contexts. Although existing data do not yet allow us to unravel its complex structure-function paradigms, it is precisely its apparent mobility and its different locations that push towards more detailed studies. Viral proteins interact with host cellular machinery; however, they frequently occupy multiple compartments [

30]. Their ability to interact and influence various organelles is strategic for the virus to manipulate cellular processes in its favor. All of this implies that viral proteins must have mechanisms to reach and interact with these compartments, and ORF7b2 is a viral protein.

The structural properties of mini-proteins such as ORF7b2 and ORF7b1 are frequently elusive [

31,

32]. Thus, we should also consider the set of their physicochemical properties to explain their structural and functional behaviors. This is based on the principle that it is the structural fluctuation that mediates the structure/function paradigm [

33,

34,

35]. The structural fluctuations of proteins are closely linked to their physicochemical properties through the movements of their atoms, side chains, and structural domains. Therefore, whatever the cellular location where an ORF7b-like fold performs its activity, it must possess all those specific physical-chemical characteristics that allow it to function. ORF7b2 should also be subject to this rule.

This study aims to understand the functions of ORF7b2 by analyzing its sequence, physicochemical and electrostatic properties, stability, residue interactions, low-frequency normal modes, and molecular dynamics, using a complete 3D-model and comparing it to ORF7b1 where applicable. ORF7b2 should possess all those physicochemical properties necessary to satisfy its multiple functional activities.

2. Materials and Methods

Electrostatic properties - The charge distribution of the proteins was evaluated in agreement with Das and Pappu [

36,

37,

38,

39]. Particularly, we calculated the fraction of charged residues, as FCR = |f+ + f−|, and the net charge per residue, as NCPR = |f+ - f−|. In this context, f+ and f− represent the fraction of positive and negative charges, respectively. These calculated values allow one to classify the protein sequences into distinct regions of the Diagram of States for IDPs: [

38] (i) weak polyampholytes and polyelectrolytes named as Region 1 with values of FCR<0.25 and NCPR<0.25 and propensity for ensembles of Globule and Tadpole; (ii) a boundary region or Region 2 between 1 and 3 characterized by 0.25 ≤ FCR ≤ 0.35 and NCPR ≤ 0.35 values; (iii) strong polyampholytes (Region 3) with FCR > 0.35 and NCPR ≤ 0.35, and propensity for ensembles of Coils, Hairpins, and Chimeras; and (iv) strong polyelectrolytes (Region 4) where FCR > 0.35 and NCPR > 0.35, with a propensity for ensembles of Swollen Coils. Finally, we have calculated the parameter k to distinguish between different sequence variants based on the linear sequence distributions of oppositely charged residues [

36,

37,

38]. We calculated the overall charge asymmetry as σ = (f+ - f−)2/(f+ + f−). For each sequence variant, we calculated k by partitioning the sequence into Nblob overlapping segments of size g. For each g residue segment, we calculated σί = (f+ - f−)2ί/(f+ + f−)ί , which is the charge asymmetry for the sequence of interest. We quantified the squared deviation from σ as:

We used g = 5 and hypothesized different sequence variants, evaluating different values of δ for each. Hence, the maximal value δmax for an amino acid composition was used to define k = (δ/δmax).

Net Charge Calculation - The net charges of proteins at a given pH are based on the formula below:

Z = ∑i Ni [10pKai/(10pH + 10pKai)] - ∑j Nj [10pH/(10pH + 10pKaj)]

Where Z is the Net charge of the peptide sequence. Ni: Number of arginine, lysine, and histidine residues and the N-terminus; pKai, pKa values of the N-terminus and the arginine, lysine, and histidine residues; Nj, the Number of aspartic-acid, glutamic acid, cysteine, and tyrosine residues. C-terminus pKa, as well as the pKa values for aspartic acid, glutamic acid, cysteine, and tyrosine residues, and pH values are all described. The pKa values used for: cysteine (pKa = 8.33), aspartic acid (pKa = 3.86), glutamic acid (pKa = 4.25), histidine (pKa = 6.0), lysine (pKa = 10.53), arginine (pKa = 12.48), tyrosine (pKa = 10.07), the N-terminal (pKa = 9.69) and C-terminal (pKa = 2.34). The isoelectric point is the pH at which the peptide Z shows zero value. Biochemistry textbooks provide formulas and pKa values.

Dipole moment - The dipole moment, in Debyes, is the magnitude of the dipole vector D = 4.803×Σriqi, as a sum over all atoms ‘i ‘, where 4.803 converts from Angstrom-electron-charge units to Debyes. The mass moment vector of the protein is calculated as Rx =Σxi2, Ry=Σyi2, and Rz=Σzi2, and the associated mean radius RM = [(Rx + Ry + Rz)/3]1/2 is a measure of the overall protein size. We also used the Protein Dipole Moment Server [

40] at the following address for the calculations:

http://bip.weizmann.ac.il/dipol.

CIDER (Classification of Intrinsically Disordered Ensemble Regions) is a web-server developed by the Pappu lab [

38], at Washington University in St. Louis. CIDER allows for the calculation of numerous parameters associated with any protein sequences. It is very specific for small proteins. The server is at the address,

http://pappulab.wustl.edu/CIDER/analysis/. The calculation of the average hydrophilicity of a peptide is based on the data from Hopp&Woods [

41].

Phase Diagram. We created the diagrams on the FINCHES web server (

https://www.finches-online.com/), a Python package at Washington University (St Louis, USA). It predicts IDR-mediated intermolecular interactions using only sequences. Calculations were performed according to Ginell, G. et al. [

42], and Garrett, M. et al. [

43]. The platform presents a bottom-up approach that uses chemical physics extracted from coarse-grained force fields to predict IDR-mediated interactions. This approach assumes that the amino acid sequence alone (considering local sequence context) captures the chemical specificity of IDRs, and that local attractive and repulsive interactions can be predicted and used to identify subregions within an IDR which can potentially facilitate attractive or repulsive interactions. This allows for quick and verifiable predictions of which protein regions and residues are likely to interact with a binding partner. By adopting this approach, we predicted phase diagrams, which offer qualitative predictions on how sequence changes should alter the diagrams. One application of this approach is in the prediction of phase diagrams between two homologous proteins directly from their sequences. The predictions made here are based on parameters got from coarse-grained molecular mechanics force fields. We used the Mpipi-GG-based (V1) force field to predict these diagrams [

44,

45]. These predictions (at least qualitatively) show how sequence chemistry affects phase behavior and explain how sequence changes affect intermolecular interactions during the IDR-mediated phase separation. We construct the predicted phase diagrams by first calculating the overall mean-field homotypic intermolecular interaction parameter, converting it into a Flory-Chi parameter, and solving the phase diagram using the analytical approach developed by Qian, Michaels, and Knowles [

46]. Comparing two sequences differing by mutations is the most helpful way to assess how mutations affect phase behavior. We should note that these phase diagrams provide a qualitative, not quantitative, description of phase behavior and phase boundary predictions. There are several important considerations when considering the meaning of these phase diagrams. This report presents phase diagram temperatures vs, volume fraction vs., where temperature is a reduced temperature. This reduced temperature is a normalized temperature at the critical temperature of the ORF7b2 sequence. Because of this, the absolute value of the reduced temperature is meaningless other than comparing ORF7b1 sequence to ORF7b2 sequence. Knowing a sequence’s phase behavior lets us predict whether another sequence will behave similarly or differently. But this comparison is only relative to one another, because we have no elements to quantify these behaviors in absolute terms. To evaluate disorder across the two sequences, we used Metapredict version 3, a deep-learning based consensus predictor of intrinsic disorder and predicted structure [

47,

48]. It generates a high-resolution, interactive, plot of the per-residue disorder and the predicted AlphaFold2 structural confidence score.

PHYRE2, Protein Homology/analogY Recognition Engine V 2.0, is a web portal for protein modeling, prediction, and analysis [

49,

50] at Structural Bioinformatics Group, Imperial College, London, UK. (

http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/~phyre2/html/page.cgi?id=index). Phyre can detect remote homology to known structures significantly beyond the range of the popular PSI-Blast. Advanced profile-profile matching techniques, loop modeling, and side-chain placement algorithms enable the building of accurate full-atom models based on homology to known protein structures with sequence identities <15%.

PEP-FOLD3 is a de novo approach aimed at predicting peptide structures from amino acid sequences through a series of 100 simulations [

51,

52,

53]. Each simulation explores a different region of the conformational space (they limit prediction to amino acid sequences between 5 and 50 residues in FASTA format). It returns an archive of all the models generated by the detail of the clusters and the best conformation of the 5 best clusters. Once complete, a Monte Carlo procedure refines the peptide structure. (

https://bioserv.rpbs.univ-paris-diderot.fr/services/PEP-FOLD3/)

MEMEMBED 1.15 (Bioinformatics Group–University College London) Membrane Protein Orientation Predictor (

https://mybiosoftware.com/memembed-1-15-membrane-protein-orientation-predictor.html) accurately orientates and refines both alpha-helical and beta-barrel membrane proteins within the lipid bilayer using a genetic algorithm and knowledge-based statistical potential [

54]. The Workbench provides a range of protein structure prediction methods. The site can be used interactively via a web browser or programmatically via our REST API.

HINGEProt (

http://bioinfo3d.cs.tau.ac.il/HingeProt/hingeprot.html) is a web server for Protein Hinge Prediction Using Elastic Network Models [

55]. HingeProt makes use of both the Gaussian Network Model (GNM) [

56,

57] and Anisotropic Network models (ANM) [

58]. GNM decomposes the fluctuations of N residues of a structure into a series of N-1 nonzero modes, given the Cartesian coordinates of Ca atoms. It extracts the eigenvectors corresponding to the slowest first and second modes. The square of these vectors describes the mean-square fluctuations (the autocorrelations) of residues from equilibrium positions along the principal coordinates (first and second modes here). Minima of mean square fluctuations at a mode describe the flexible joints of the structure, i.e., the hinge regions, which connect the rigid units and mobile loops. The hinge regions are the mechanistically informative regions of the structure and are of importance in mediating cooperative motions that have functional importance. GNM calculates the mean-square fluctuations and the correlation between the fluctuations of residues in the most dominant (slowest two) modes, which were shown to overlap with known protein motions. These suggest hinge regions and the cooperation between them. ANM characterizes the direction of the fluctuations in the corresponding modes, because the GNM fluctuations are isotropic. It predicts the fluctuations of N residues in the x, y, and z directions from the average structure (X-ray or NMR) in 3N-6 ANM nonzero modes [

58]. ANM analysis yielded the fluctuation directions of residues in GNM’s two slowest modes after mapping ANM modes to GNM modes based on a comparison of squared fluctuations. Since the equilibrium positions show symmetrical fluctuations, ANM-predicted deformed structures can be obtained by adding to or subtracting from each residue’s equilibrium position its fluctuations.

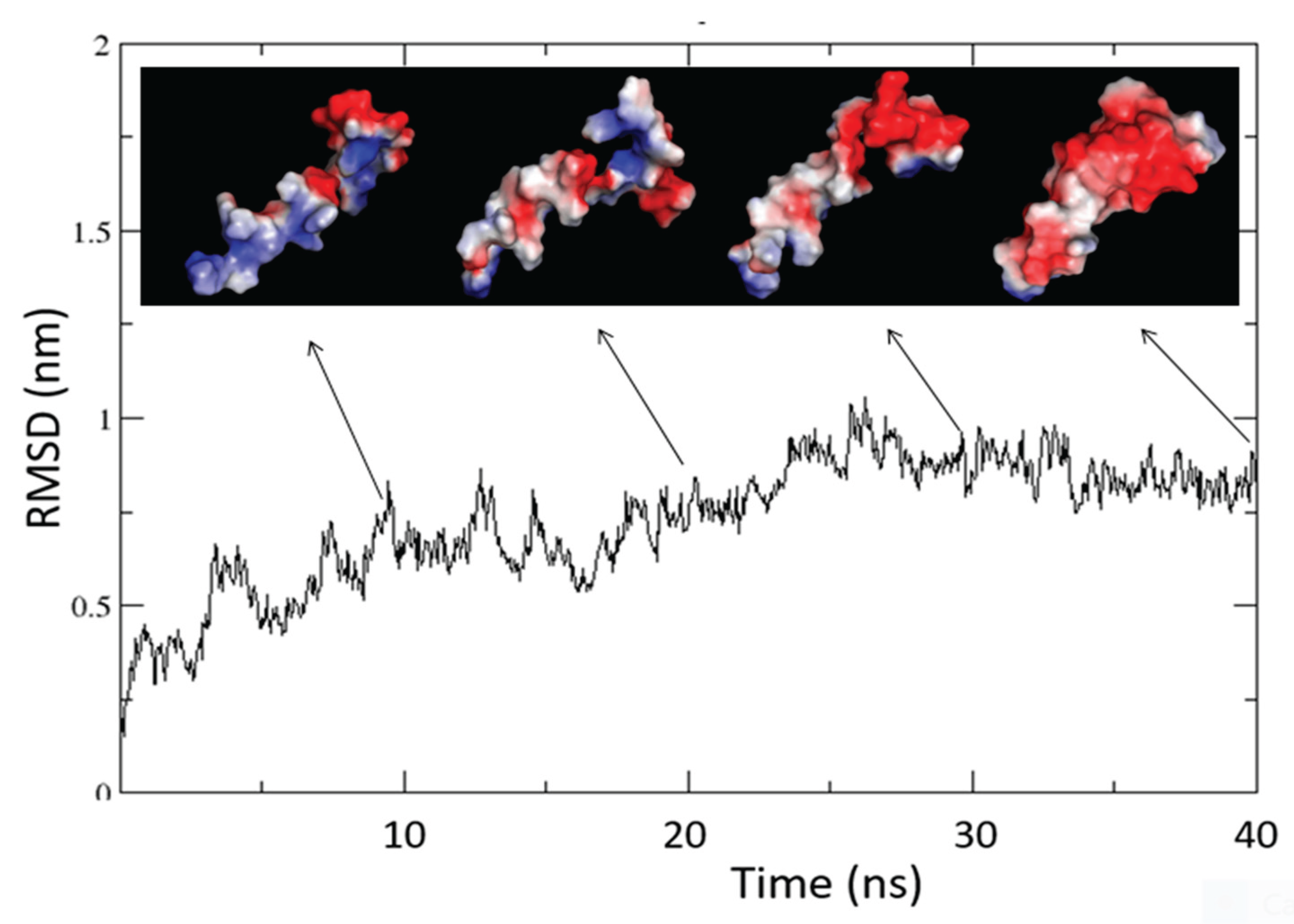

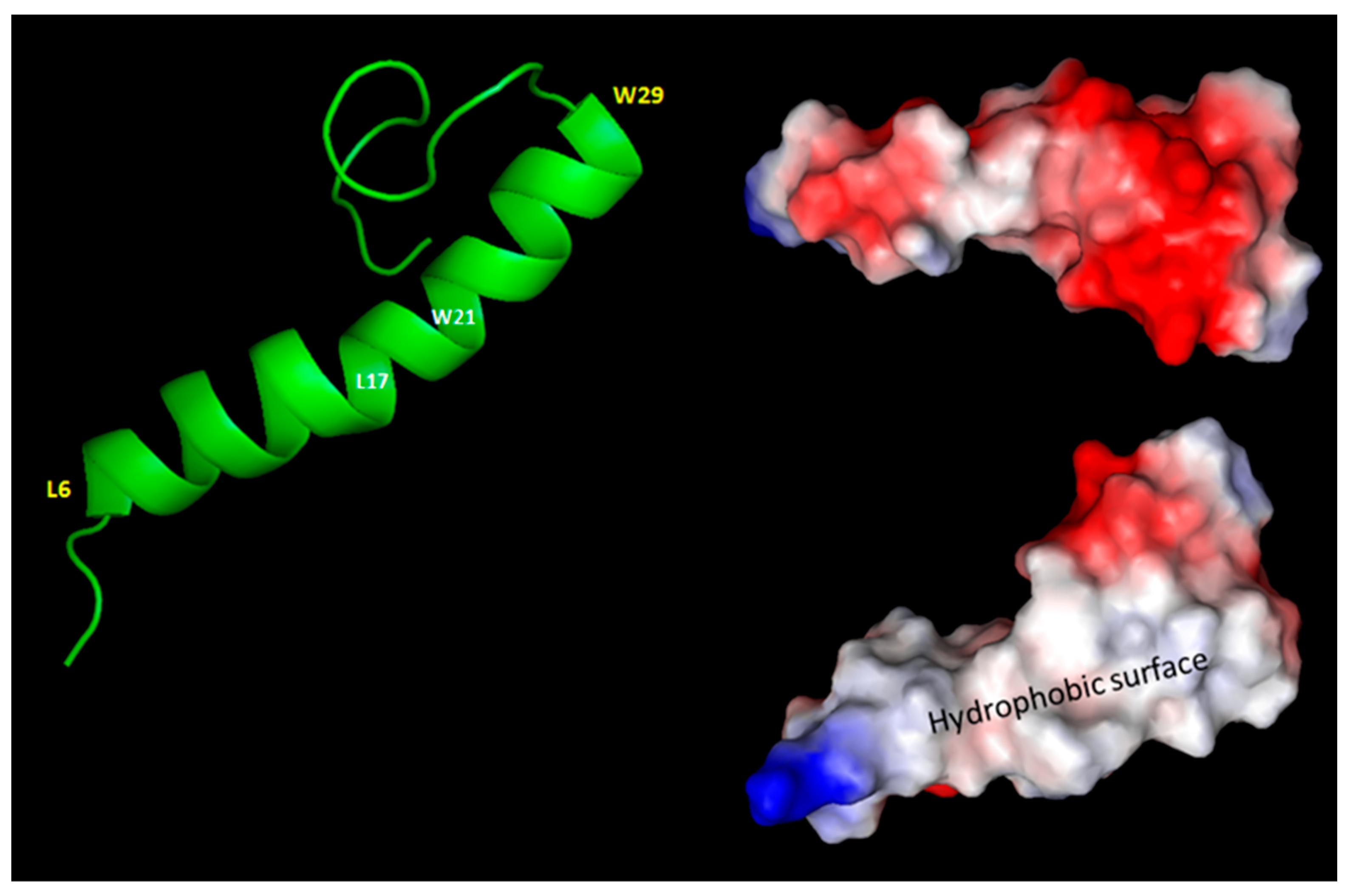

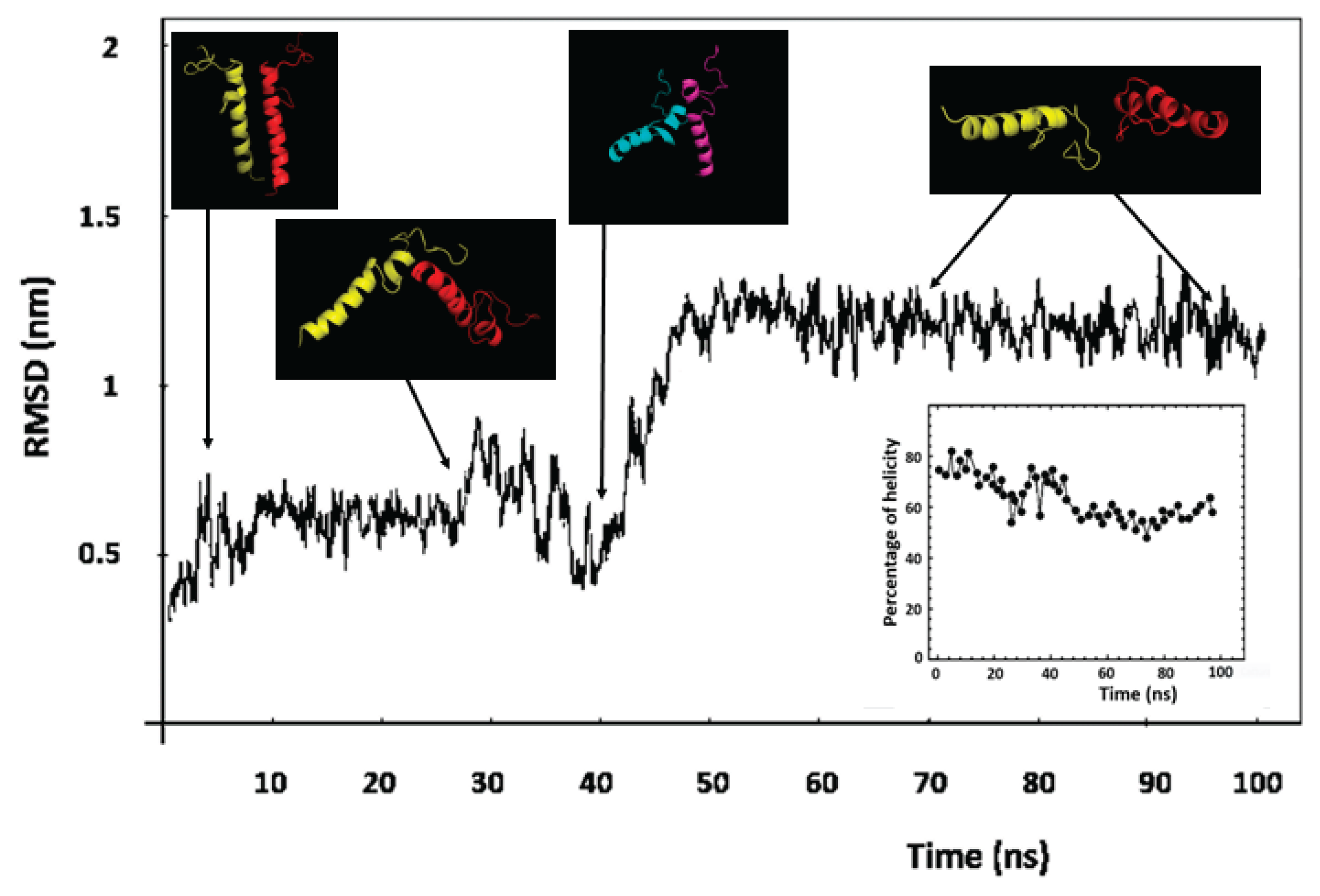

Molecular Dynamics - The GROMACS software (v4.5.6) performed molecular dynamics (MD) simulations [

59,

60] on the best model of ORF7b2 using the GROMOS43a1 all-atom force field at neutral pH. In a previous paper of ours [

61], we evaluated this force field as one of the most suitable for simulating the folding of short peptides. We placed the model into a cubic box with 86.2 Å sides, solvating it with 21329 SPC216 water molecules. Initially, we performed 2000 steps of energy minimization and 25000 steps of position restraints to equilibrate the protein and balance the surrounding water molecules. We subjected the complete 3D structure of ORF7b2 to MD simulations for 40 ns in explicit water, setting the time step at 2 fs, the temperature at 300 K, the time constant at 0.1 ps, and pH 7.0. We performed a second set of experiments in a solvated lipid bilayer under similar experimental conditions with a dimeric 3D structure of ORF7b2 present. HDOCK modeled the structure. To achieve this, we integrated a pre-oriented (OPM database;

http://opm.phar.umich.edu) dimeric ORF7b2 model into a 130-POPC lipid bilayer, built with VMD’s membrane builder, considering its residue hydrophobicity. This approach rigorously calculates, based on energetic and thermodynamic considerations, how the helix embeds in the membrane. The OPM model is shown in

Supplements (Figure12S????). After inserting the correctly oriented helix into the membrane, we solvated the entire system in a box containing 10985 water molecules. Subsequently, we used VMD to ionize the system and processed it through three steps: (i) equilibration and melting of lipid tails, (ii) minimization and equilibration with the protein constrained, and (iii) equilibration with the protein released. After these three steps, we subjected the entire system to MD simulation for 100 ns, at 300 K and neutral pH.

Molecular Dynamics Analysis - We analyzed the trajectories, which contain information about the time evolution of all the atoms’ coordinates, using various GROMACS routine utilities. These utilities include root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), gyration radius (Rg), root-mean-square fluctuations (RMSF), helicity, total solvent accessible area (ASA), and others. Principal Components Analysis (PCA) calculated the relevant functional motions. We calculated the number of H-bonds and interactions with their closest atoms (IAC) using the Protein Interactions Calculator (PIC), HBPLUS, and COCOMAPS tools.

(ORF7b2-ORF7b2) Docking - HDOCK server (

http://hdock.phys.hust.edu.cn/), a web server for protein-protein docking based on a hybrid strategy [

62], was used to model ORF7b2 dimerization in silico. The information entered for receptor and ligand molecules was the best ORF7b2 Phyre2-model. The server automatically predicts their interaction through a hybrid algorithm of template-based and template-free docking. Data input that accepts both sequence and structure is the first step of the process. The second step of the workflow is a sequence similarity search. The workflow uses the input sequences, or those converted from structures, to conduct a sequence similarity search against the PDB sequence database. This search identifies homologous sequences for both receptors and ligand molecules. In the third step, we compare PDB codes and select a common template for both receptors and ligand. If the two sets of homologous templates show no overlap, we will select the best template for the receptor protein and/or the ligand protein from each set. If multiple templates are available, we select the one with the highest sequence coverage, highest sequence similarity, and highest resolution. Using the selected templates, MODELLER builds models; ClustalW conducts the sequence alignment. The last step is traditional global docking. Here, HDOCKlite, a hierarchical FFT-based docking program, is used to sampling putative binding orientations. A web page interactively displays the top 10 docking models.

Orientations of Proteins in Membranes (OPM) database - OPM provides spatial arrangements of membrane proteins regarding the core of the lipid bilayer [

63]. OPM provides preliminary results of a computational analysis of transmembrane α-helix binding in experimental structures for dimeric proteins. The PPM3 server positions proteins in a bilayer of adjustable thickness and curvature to minimize their transfer energy from water to the membrane. The server treats each protein as a rigid body floating in a hydrophobic slab of adjustable thickness. In our experiment, we settled a membrane with a Golgi-like composition, 29.4 ± 2.7 Å thick. Orientation of the proteins was determined by minimizing its overall transfer energy to –28.8 kcal/mole regarding variables in a coordinate system whose axis Z coincides with the bilayer normal. The calculation of the longitudinal axes of TM proteins used vector averages of TM segment vectors. The resulting tilt angles were 13 ± 2°, and 15 ± 2.5° for the two monomers. To pre-orient probable transmembrane proteins in a lipid sheet system, we use the OPM server. This method reduces equilibration times in membrane molecular dynamics simulations. We show the orientation results in Figure 12S.

Charge distributions and electrostatic potential calculations. DelPhi calculated charge distributions and electrostatic potentials [

64] with a finite-difference solution of the Poisson-Boltzmann equation. DelPhi is an electrostatics simulation program that can investigate electrostatic fields in a variety of molecular systems, including proteins. It is possible for DelPhi to take as input a coordinate file. DelPhi includes solutions to the nonlinear form of the Poisson-Boltzmann equation, which provides more accurate solutions for highly charged proteic systems. Many other features enhance the speed and versatility of DelPhi to handle complicated systems and finite difference lattices of extremely high dimension. We ran the DelPhi executable on a server with Fortran and C compilers. The program can be downloaded at the following address

https://honiglab.c2b2.columbia.edu/software/cgi-bin/software.pl?input=DelPhi at the Columbia University. The input pdb file should be in PQR format, which includes atomic radii and atomic charges. We used PDB2PQR [

65], a Python software package, for this purpose. This package automates many common tasks in preparing structures for continuum electrostatics calculations and provides a platform-independent utility for converting PDB format protein files to PQR format. For the result, analysis is required to read out and display the potentials. The program offered the option to output a potential map, readable and contourable in PyMOL (or even Biosym). A utility facilitates this.

Effect of pH on Protein Stability - We used Protein-Sol, a web server running at the University of Manchester, UK, (

https://protein-sol.manchester.ac.uk/) devoted to the calculation of both the scaled solubility value and several stability parameters (heat maps) of proteins [

66]. The server uses both the sequence and 3D models for its calculations. The Protein-Sol sequence algorithm calculates 35 sequence features related to the protein solubility, among which folding propensity [

67], disorder propensity [

68], beta strand propensities [

69], Kyte-Doolittle hydropathy [

70], pI, sequence entropy, absolute charge at pH 7. But also, the Solvent accessible surface area (SASA) for each atom (an atom was defined as buried for SASA <5Å2, and surface accessible otherwise), the ratio of non-polar to polar (NPP ratio) values at interface, from which the predicted sign of the net charge per residue is calculated. This information is used to calculate heat maps for the pH and ionic strength dependence of protein stability in the folded state, using the Debye-Hückel (DH) method for interactions between ionizable groups and pKa calculations. The heat maps show the predicted net charge (in electrostatic units per amino acid) and the predicted pH-dependent contribution to stability (in Joule per amino acid). Further information and details are available in the article [

66].

Residue Interaction Network Generator (RING 4.0:

https://ring.biocomputingup.it/) is a platform online to calculate graphs (interactomes) of residue-residue interactions of single proteins by a web server called “Residue Interaction Network Generator 4.” It analyzes how different parts of molecules (especially proteins) interact with each other [

71]. Node representation - Closest (default): The system considers all atoms of the residue (or group) when measuring the distance. This option is convenient for PDBs with a resolution for which is safe to consider side-chain coordinates. The program always processes ligand or hetero groups with all atoms.

Edge representation (cardinality): The RING algorithm identifies all interactions that connect chemical components. The Chemical Component Dictionary (PDB HET dictionary), an external reference file describing all residue and small molecule components found in PDB entries, establishes them. The hydrogen bond’s maximum donor-acceptor distance was 3–9 Å, with an angle ε > 90° [

72], while the H-acceptor distance was 2.5 Å for h-bonds, 6.5 Å between aromatic ring centers for π-π interactions [

73], and 0.01 Å for the intersection between two atoms’ van der Waals radii (0.0–1.0). RING can estimate the vdW interactions. Unless otherwise specified, we calculate the distance between a pair of atoms using their centers (i.e., the 3D coordinates that are present in the PDB file).

Centrality analysis -The graphs are downloadable in Json format for input into Cytoscape. Cytoscape performs the Centrality analysis. It identifies the most central, most important, or most significant nodes in a network. A single index does not define centrality, but by several indices in correspondence to the different structural aspects of the interactions that a researcher may intend to focus on. Residues crucial for 3D-fold or function are high centrality nodes [

74]. Edge betweenness is an important edge centrality and shows the topological importance of edges in the network Specifically, it is linked to interactions, those between two parts of a structure, i.e., domain boundaries and interface in multimeric proteins and protein complexes enabling inter-domain and protein–protein interactions. RING3 is a tool that can analyze how interactions within a molecule change when that molecule changes its shape. It does this by taking structural data from PDB files, even when those files represent multiple versions of the molecule.

Closeness centrality–Closeness Centrality is a network measure of nodal importance, quantifying how prominent a node is relative to others [

75]. Closeness centrality (Ci) measures the proximity of a node i to all others within the network. Statistically significant central residues are evaluated using the z-score values of the residue closeness centrality which is defined by Zk = Ck−C¯/σ where Ck is the closeness centrality of residue k, C is the mean closeness centrality value, and σ is the corresponding standard deviation [

75]. Protein core and peripheral residues of membrane proteins are identifiable via residue centrality [

76].

3. Results

3.1. Sequence

The 3D structure of ORF7b2 has not yet been determined experimentally. As a result, we still poorly correlate structure-function relationships because of the limited knowledge of how the protein structure behaves in the biological environments where it functions. Our goal is to understand which structure-function relationships are attributable to ORF7b2, by comparing the properties of ORF7b2 and ORF7b1, when necessary. The

Table 1 and

Table 2 compare some basic chemical properties of the two viral proteins.

Comparing the two proteins is useful to understand how similar they are and how similar their functional behavior may be. Figure 1S shows the distribution of hydrophilicity along the two proteins. We can observe that the central 21-residue segment (9-30) is hydrophobic and similar in both proteins; all tails, however, are strongly hydrophilic and rich in charged residues. In

Table 1, we note the lack of positively charged residues and proline in ORF7b2, while ORF7b1 possesses both one proline and a positive charge. In

Table 2, we find ORF7b2 residues with high propensity for disorder [

78], such as T, A, D, H, Q, S, and E in the C-term and E, S, D in the N-term, where D is also a known helix disruption residue [

79]. However, disorder is common both in globular proteins and in transmembrane proteins [

80]. While ORF7b1 has the proline at position 40 of its C-terminal end, and proline is another helix-disrupting residue. This observation is significant because the tails’ properties affect both the structure’s chemical-physical properties and its stability behavior. The sequences lead us to think that the C-terminal segments should fluctuate because of a reduced or missing local helical organization. Another feature that emerges from the sequence is that both proteins do not possess the characteristic signals to enter the endoplasmic reticulum. This calls into question various conclusions found in the literature.

3.2. Electrostatic Properties

3.2.1. Analysis According to Pappu

Before any three-dimensional consideration, it is important to evaluate the physical-chemical properties of both proteins, among which the electrostatic effects are of particular interest when hypothesizing interactions with membranes. Rohit Pappu has developed [

36,

37] an analysis for small peptides and proteins that provides a series of parameters to help evaluate the conformational shapes that molecules can adopt in solution, although with a basic approximation. Among the calculated parameters, we also have evaluated the electrostatic properties [

38].

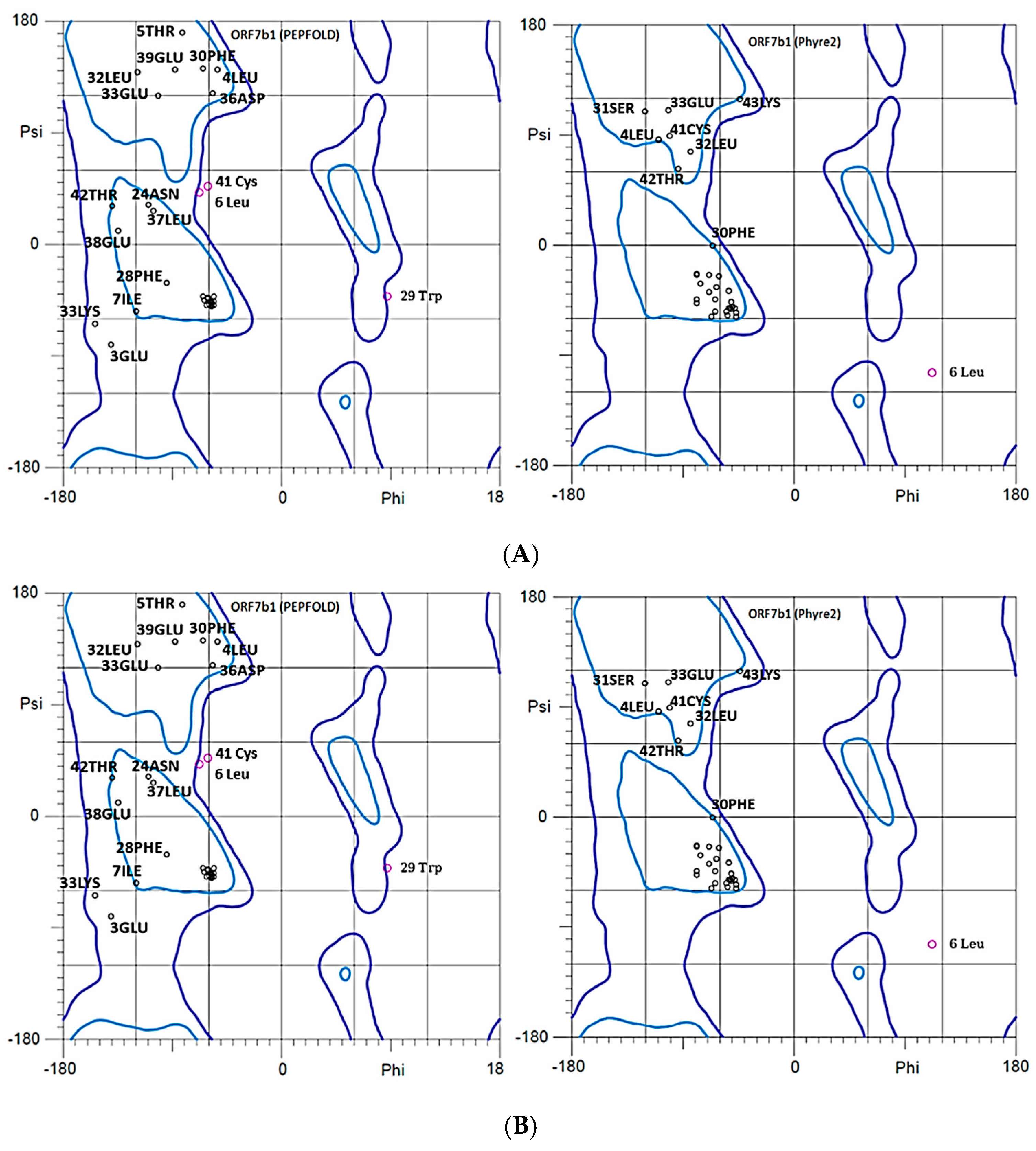

The analysis of the charge distribution of the two proteins (

Table 3,

Figure 1 and 2) shows rather similar negative values of the net-charge distribution per residue (NCPR), but different values of the charged residue fractions (FCR) with a more asymmetrical distribution for ORF7b1. These values allow to characterize the organizational tendency of a polypeptide in solution by classifying it in one region of the State Diagram. The state diagram (

Figure 1) shows that both proteins are in region 1, characterized by globular extended structural organizations (globule/tadpole conformation), thus in solution, they behave as globule-like.

According to the model used in this analysis [

36,

37], electrostatic attractions between oppositely charged residues favor a globule-like organization, while the hydration free-energies of similarly charged residues, which repel each other, favor an extended structure. A low net charge per residue with high fractions of positively and negatively charged residues characterizes polyampholytes [

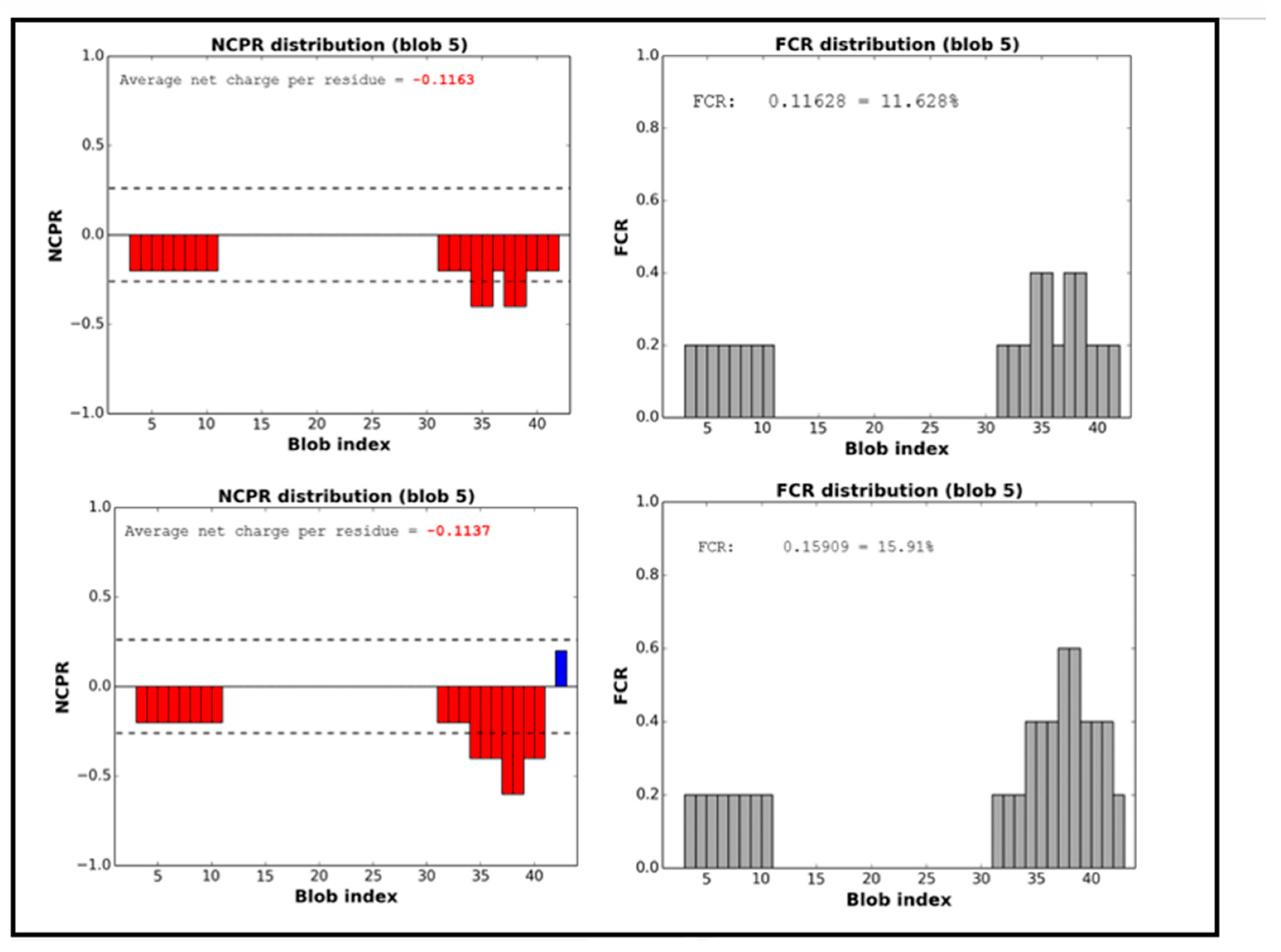

38]. Therefore, the behavior of ORF7b2 in solution should be that of a negative weak polyampholyte (FCR <0.3) and should behave as extended-like protein-systems with negative charges asymmetrically arranged in both terminal segments (

Figure 2). The entire protein also possesses a distributed negative charge, averaging −0.1163 net charge per residue; in solution, it displays an overall negative net charge (

Figure 3) dependent on pH, between 4.3 and 10. Even ORF7b1 behaves like a weak polyampholyte with a more asymmetrical charge distribution than ORF7b2 (

Table 3) but a similar mean value of NCPR. This characteristic drives the dependence of the net charge on the pH like that of ORF7b2. Their small size and limited total surface area characterize the proteins. This implies a considerable intensity of the surface charge distribution because of the strong net negative charge, even considering the asymmetry.

Analysis of these results causes careful consideration of ORF7b2’s transmembrane localization, because of the negative charge present on both leaflets of the phospholipid bilayer at physiological pH [

82,

83,

84]. Here, a total negative charge of -4 and negatively charged terminal regions unusually flank the central helical segment, a common transmembrane structure. The high energy required to solvate negative charges (aspartic or glutamic acid) in the nonpolar environment of the membrane core strongly disfavors them. Notably, studies of ORF7b2 and ORF7b1 have largely neglected to emphasize the basic electrostatic properties that instead appear to be crucial. They limited the discussion to the protein’s central transmembrane helix. This approach might have compromised a comprehensive structure-function analysis of the proteins in question.

3.2.2. Dependence of Net Charge on pH

To understand the electrostatic behavior of both proteins in solution, we also calculated the pH dependence of the net charge (see methods for details). The net charge of the two proteins is not constant, it changes with pH, influencing stability and solubility. In fact, pH, by modifying the ionization of groups and chemical interactions, influences the shape and function. The change in shape also involves changes in the relative solvent accessibility of amino acid residues, which perturb both surface charge and solubility.

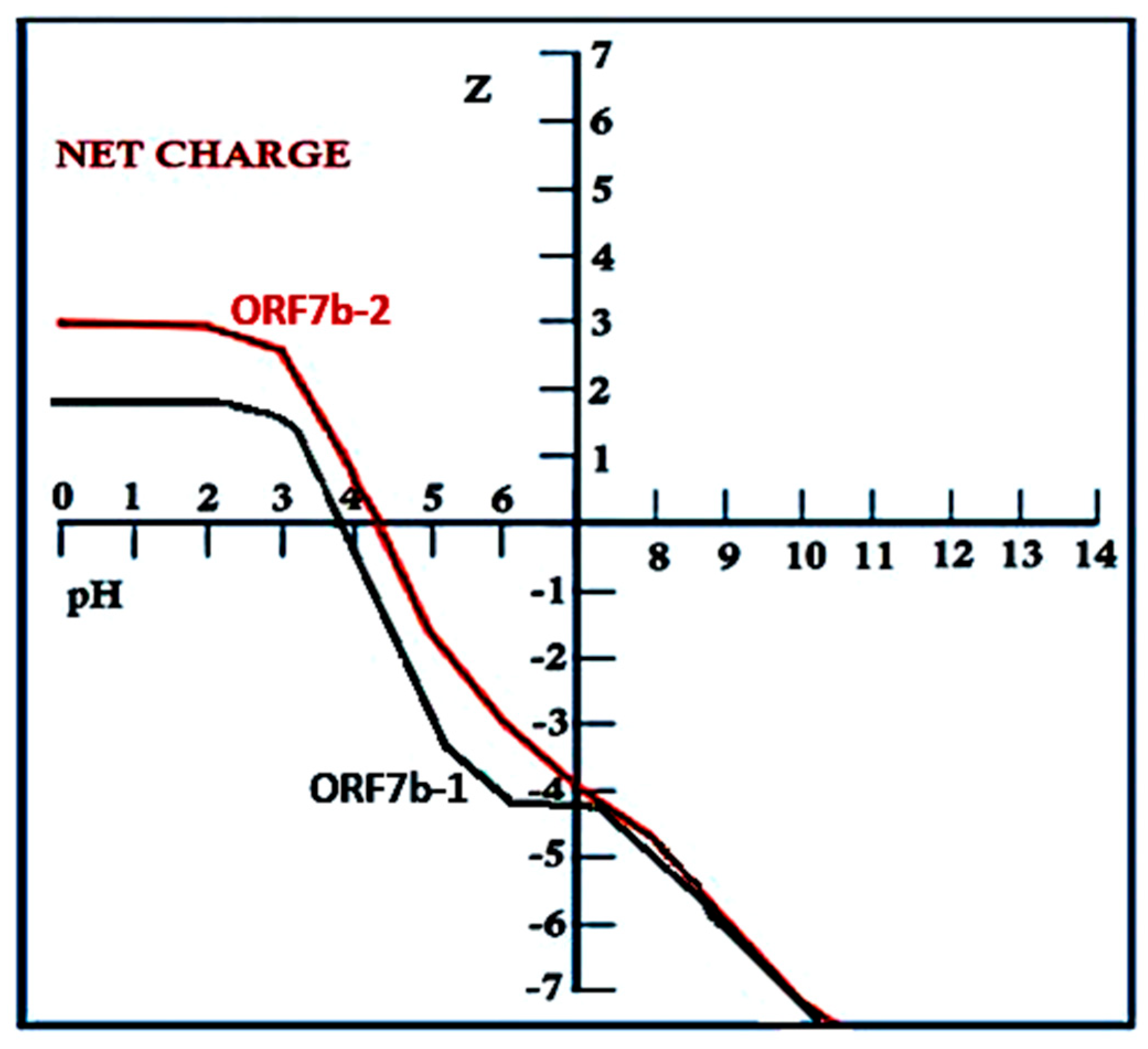

Figure 3 shows the pH dependence of the net charge (Z) of the two proteins.

The figure shows that the curve of ORF7b2 has a strong negative slope starting from pH 4.3 (= isoelectric point). Even ORF7b1 shows a strong negative slope, but with a pronounced shoulder centered at pH 6. The slope begins at pH 4.3, which is also the isoelectric point. Pappu’s calculations agree with the electrostatic values got graphically. Although their trends are similar, the two curves show different intensities in the positive area and a pronounced shoulder in the negative area. The steep slopes give the two proteins an acute sensitivity to the pH of the medium.

These observations suggest that ORF7b2 and ORF7b1 possess electrostatic characteristics that make their structures sensitive even to minimal changes in pH to adapt them to different environments. The steep slope of the curve, even in the physiological range, changes the net charge and its distribution on the surface. Between pH 3 and pH 10, the net charge varies from about +3 to -7, making structures sensitive to pH changes. These changes exert an enormous influence on the electrostatic interactions that the two proteins can have with other proteins or with membranes. This favors a widespread cellular activity. That ORF7b2 has 1,765 physical interactors implies it must have a mechanism to reach and interact with these proteins in multiple cellular compartments. Its ability to modulate net charge expands the number of interactions and explains why ORF7b2 is involved in such diverse metabolic activities in various cellular districts. Although the two proteins exhibit similar electrostatic behaviors, unfortunately, we lack functional information from interactomic studies for ORF7b1 that could have characterized its functional activities and likely cellular locations.

However, to gain more insight into the causes of differences in the curves, we compared the net charge versus pH trends for the central segment and for both tails of the individual molecules. The Figure 2S shows that the central and N-terminal parts of both proteins remain flat around neutrality, but still influence the positive and negative sides of the curve at the extreme values. The distorting effects on the curve and the higher charge intensities arise from the C-terminal tails. In particular, the shoulder of the ORF7b1 curve derives from the contribution of its C-terminal segment. So, the terminal segments affect the general electrostatic properties of the two proteins. But what is most interesting is that the central segment maintains a net charge of zero between pH 6.5 and 3.5. Outside this range, towards more alkaline pH, its charge becomes negative, while towards acidic pH, becomes positive. Both proteins have N-termini with similar charge characteristics. They are neutral between pH 5.5 and 8.0 and become oppositely charged outside the range. The behavior of the C-terminal segments is different. They have a net charge of zero only at pH 6 (ORF7b2) and pH 4.5 (ORF7b1). In the physiological neutrality range, from pH 6 onwards, both show a net charge that rapidly becomes negative. These observations suggest that both the central segments and the C-terminal tails are involved in determining the overall electrostatic behavior of proteins with an evolution towards negative changes in net charge already in the physiological pH range, starting from pH 6. Under these conditions, both the central helix and the C-terminal segment of the two proteins show a remarkable susceptibility to changes in pH. Considering that these responses can induce very rapid structural changes, we find two proteins capable of frequenting different environments with different functional responses. In fact, the broad and diverse functional response found in very different cellular environments for ORF7b2 is the best evidence of how these proteins are driven by their chemical-physical characteristics and by the interaction with the environment.

3.2.3. Stability Maps

An alternative method for evaluating the effect of pH on proteins is to connect it to their stability. By analyzing the average surface electrostatic charge per residue, along with the average surface energy contribution per residue measured in Joules, we can estimate the relationship between pH and protein stability. The University of Manchester (UK) web server [

66,

85] (

https://protein-sol.manchester.ac.uk/) facilitates these evaluations by utilizing 3D protein models as a starting point. This system generates maps that illustrate how a protein’s folding stability is influenced by pH and ionic strength. Additionally, it employs ionizable group interactions and pKa calculations using the Debye-Hückel (DH) method, directly linking pH-dependent stability to electrical charge [

86,

87,

88].

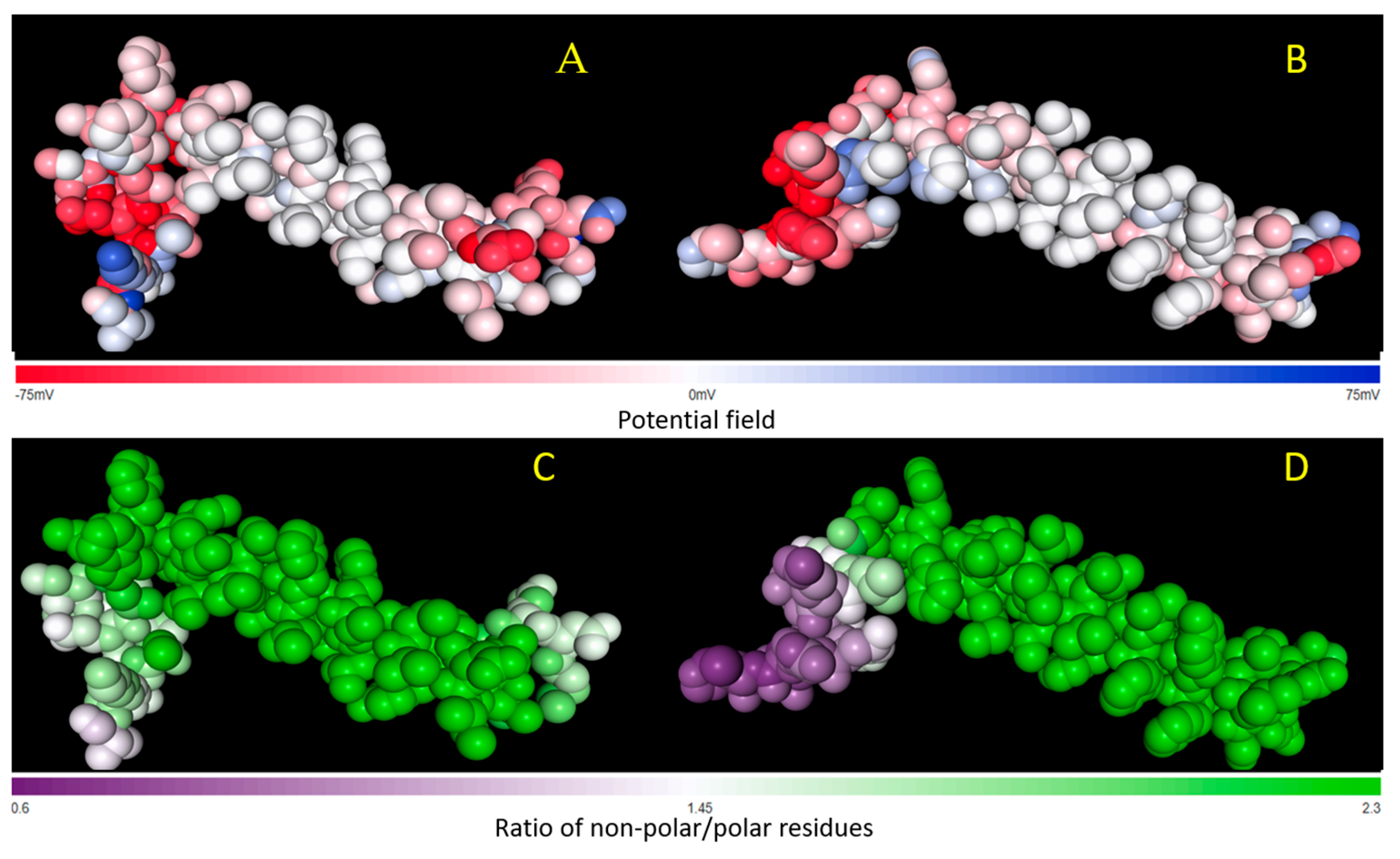

The system rebuilds the 3D structures of three-dimensional models and assigns a single structural categorization to each atom. A color scale displays the value of each categorization. These structural categorisations are based on solvent accessible surface area (SASA) calculated for each atom. They also calculate the ratio of non-polar to polar (non-polar to polar, NPP) of SASA and the charge values, assigned to each constituent atom of the surface. Although acidification tends toward a more positive protein and increased ionic strength reduces electrostatic interactions, the net result is a delicate balance of the constituent parts. But polar, non-polar, pH-dependent and ionic strength properties also influence the stability of proteins in solution. From the categorisations we can assemble two types of maps, also called “Heatmaps”. One shows the expected charge in electrostatic units per residue, and the other shows the energy contribution in Joules per residue. Together, they describe the stability of each protein as pH and ionic strength change. This allows a direct comparison of the two proteins, considering that they vary by only one residue.

Figure 4 (top) shows the comparison between the electrostatic surface potentials for atom of ORF7B1 (A) and ORF7b2 (B) plotted alongside the potential color-code. The two molecules show a fairly similar surface charge distribution with only small local differences. The nonpolar/polar ratio per atom significantly alters the distribution of the two molecules (see

Figure 4, bottom).

A higher NPP ratio reflects more apolar parts, while a lower NPP ratio refers to more polar parts. The central region of ORF7b1 is apolar, while its tails, although more polar than the core, remain sufficiently hydrophobic. While ORF7b2, while showing a predominantly apolar central segment, has a decidedly polar C-terminal tail. These differences show that the two proteins have significant differences in the distribution of surface charges. The

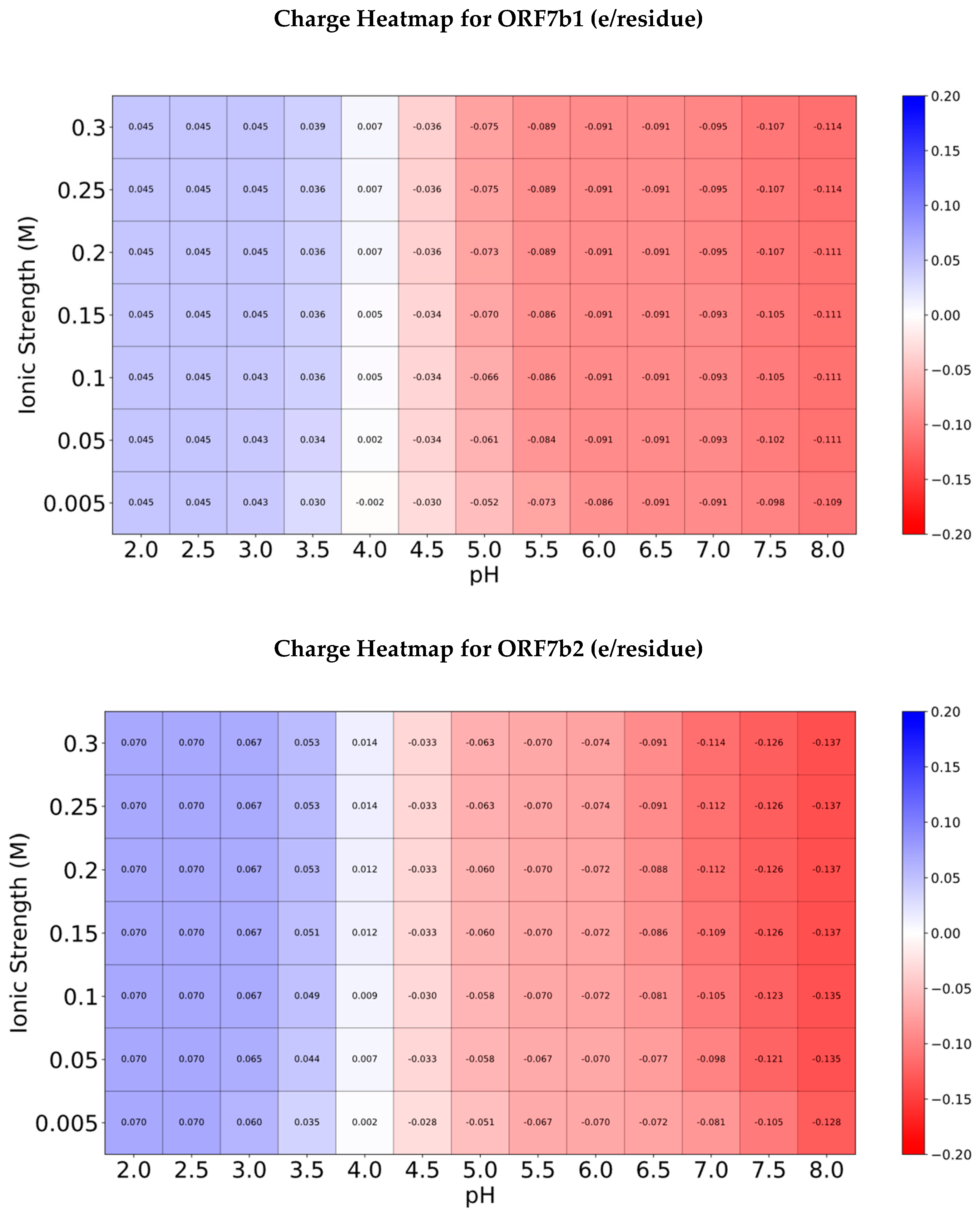

Figure 5 shows the charge heatmaps for both proteins.

The two maps show a fairly similar distribution of charges per residue between the two proteins (

Figure 5, top and bottom), with average absolute values either much more negative or much more positive for ORF7b2. Extreme acidification (pH 2.0 - 3.5), even when varying the ionic strength, leads only to positive residues, with values very similar to each other for both proteins. Starting from pH 4, where the average charge of the residues approaches zero, increasing the pH leads to more negative average values, although smaller for ORF7b2. Increasing the ionic strength at each pH has similar effects in increasing the negative absolute value of the residues. These results closely reflect the trend of the titration curves depicted in

Figure 3.

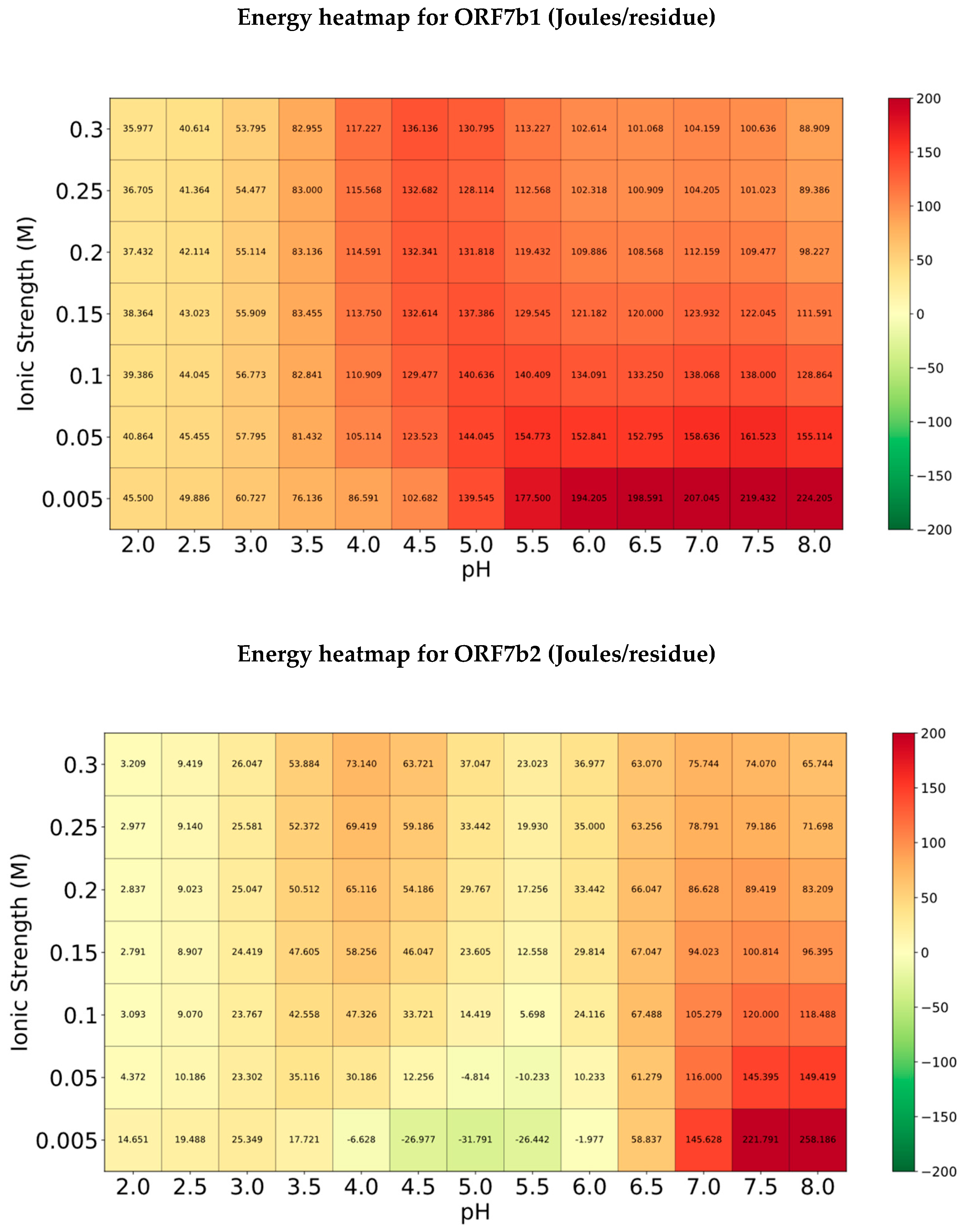

Comparison of the two energy heatmaps reveals a different stability as the pH and ionic strength change. The energy values of the various ORF7b1 distributions (figure 6, top) are all positive, with the highest values at alkaline pH and low ionic strength. These data tell us that this protein should be soluble and stable in apolar environments. Solubility refers to interactions thermodynamically stable between the protein and hydrophobic molecules in apolar environments. Overall, these data support a behavior as an intrinsic membrane protein for ORF7b1.

The distribution of ORF7b2 (

Figure 6, bottom) is quite different. Many of the absolute values of the energy distribution between 4.0 and 6.5 are quite low compared to those of ORF7b1 and close to zero. In particular, they are negative at low ionic strengths between pH 4.0 and 6.0. This suggests that the protein on average does not have the characteristics of an intrinsic membrane protein and that under specific conditions it is also stable in polar environments and probably it is also soluble in aqueous systems under those specific circumstances. The condition that favors its stability in apolar environments is those of alkaline pH above 7 and at low ionic strength. The peculiarity of this distribution is that it shows a window of stability to polar environments under particular conditions of low ionic strength, with a maximum at pH 5. This result, compared to the trend of the net charge pH dependence curve, covers the range of maximum slope of the curve, supporting a highly sensitive behavior to minimal pH changes between 4 and 6 in polar or aqueous environments.

3.3. 3D Models

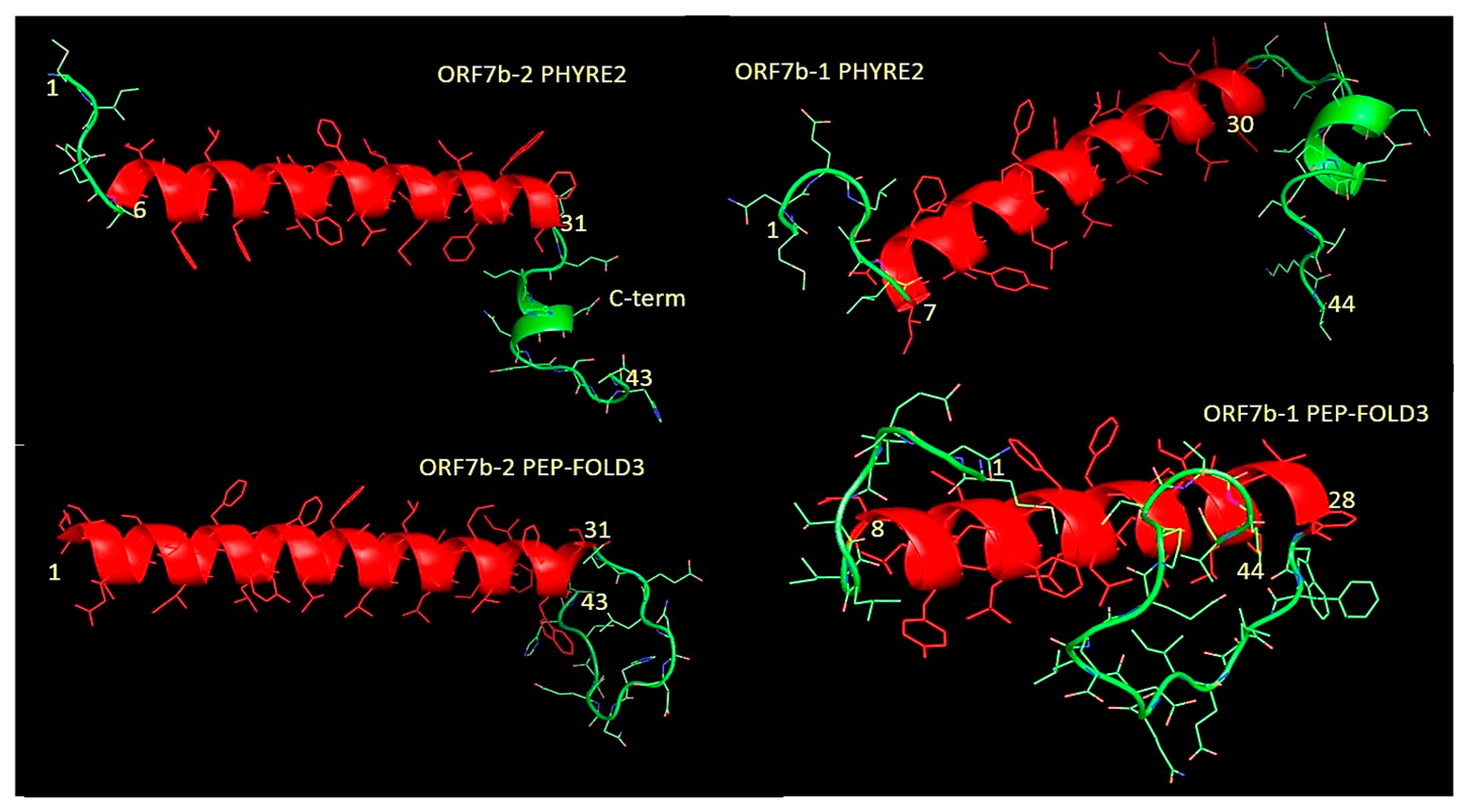

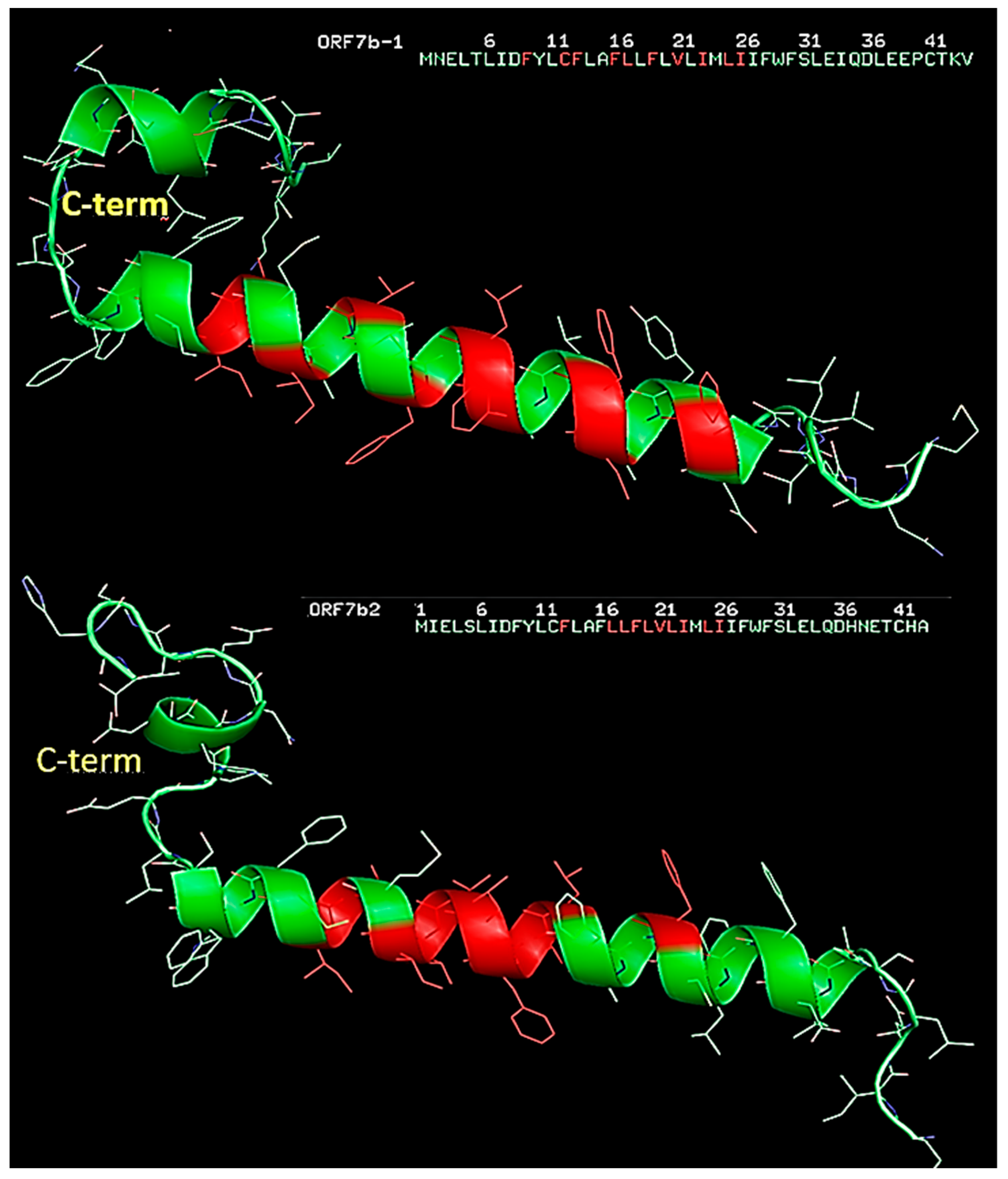

As mentioned above, only models of the structure of these proteins exist. One of the most accredited models of ORF7b2 is that from ModBase (University of California San Francisco–UCSF) (Figure 3S). This model, like various others, shows only the 3D structure of the region between Leu4 and His37, predicted as a helix, but all terminal residues are missing. The first step to acquiring a correct understanding of the structure/function relationships of a protein is to obtain a complete structural model. In

Figure 7, we can see the complete models of the two proteins got through two different modeling platforms, PHYRE2 [

50] and PEP-FOLD3 [

51,

52,

53], with fairly similar results.

Each platform produced several dozen models, where the overall reliability of the best models is 88% for both proteins. They modeled the central helical residues using specific templates (Table 1S and 2S), while they modeled the outer, C- and N-terminal segments (in green) using ab initio techniques. The charge distribution analysis (Figure2) demonstrated an asymmetric distribution of the negative electric charge on proteins and three-dimensional models reflect these effects. Both proteins show terminal segments with a three-dimensional organization detached from the compact one of the central helices. In particular, the C-terminal extremes have many more differently organized residues than the N-terminal extremes. The C-terminals are lengthy, around 12-14 residues. The intrinsic algorithms of the two modeling platforms treat the results differently, although they reach similar overall conclusions. For example, ORF7b2’s C-terminal residues show differing organization predictions between those of PHYRE2 and PEP-FOLD3. For the same protein, while PHYRE2 predicts 6 non-helical residues in the N-terminus, PEP-FOLD3 predicts that all these residues are helical. Concerning ORF7b1 models, PHYRE2’s model closely resembled that of ORF7b2’s, and PEP-FOLD3 predicted non-helical residues in both tails. We should note, however, that PHYRE2 produced quite similar structures for both proteins.

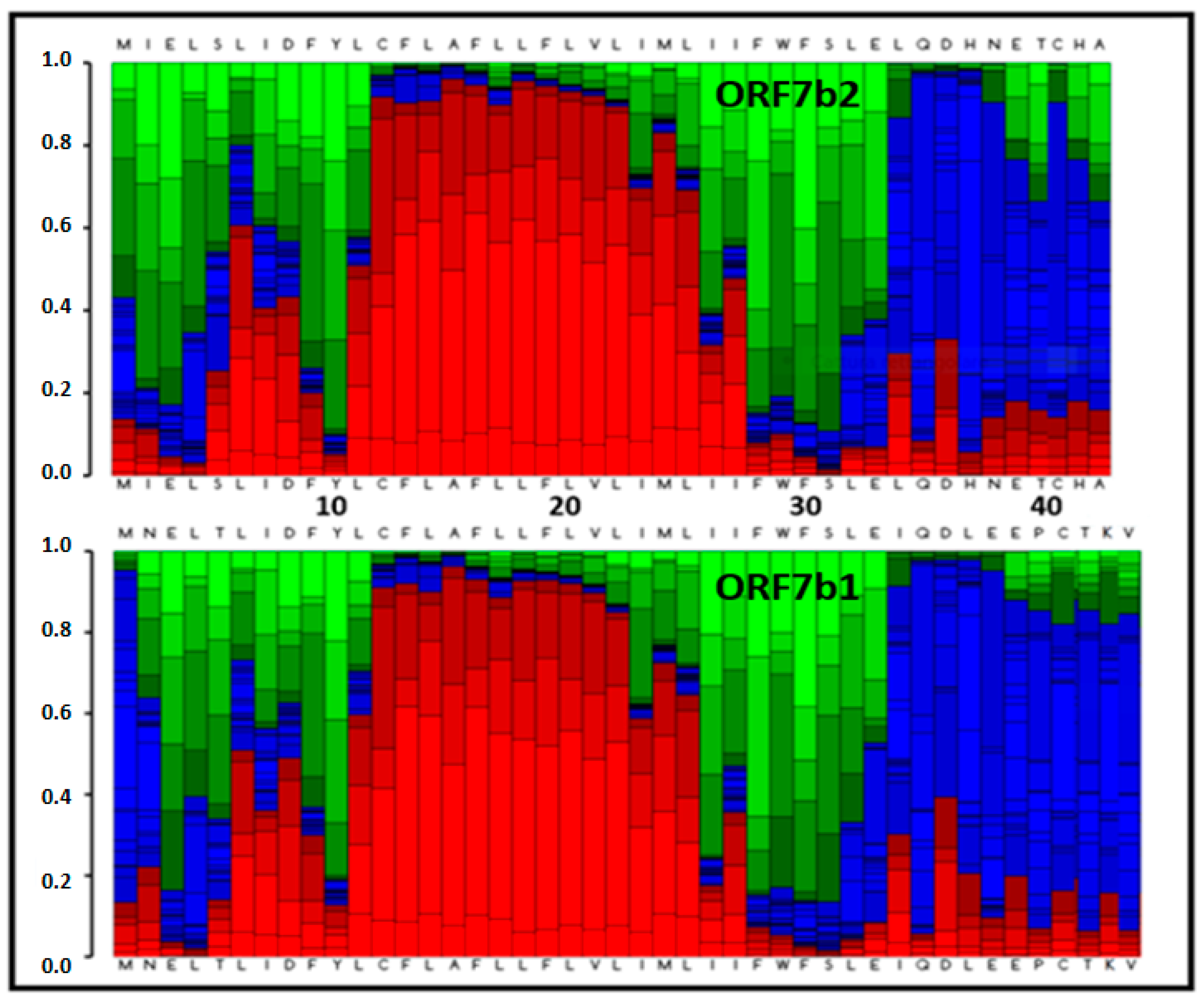

We can get some more explanation by analyzing the weight of the conformational probabilities of each residue in the two proteins. This analysis, performed by PEP-FOLD3, is based on the concept of structural alphabet [

89] and determines the mean weight of each elemental conformation that each residue uses in determining the conformation of the protein. The

Figure 8 shows the weighted distribution of all conformations for residue [

52,

89], for both proteins. From the conformational point of view, the two proteins have a compact helical core of 11 - 12 residues, not suitable for the structural needs of a transmembrane helix, which is of about twenty residues [

90,

91].

A last, but no less interesting observation, derives from the set of conformations per residue that characterizes the terminal segments of the two helices. We can observe the weighted composition of the conformations for both N-terminus. The elongated and spiral conformations (green and blue in the figure) together have a considerable percentage weight, with the greatest weight for the extended one. Also, the two C-terminals show a similar condition, but with a different conformational incidence of the coil and of the extended structure. From the residue 26 to 33, we have a preponderance of extended conformation (green), and from 33 to the end coil (blue). Both tails degrade into a less organized and flexible segment, with a probable coil ⇋ extended dynamic interconversion. The N-terminal segment seems also flexible but with a greater propensity for extended organization. In fact, the terminal segments experience non-helical organizations, where the residues are likely to undergo continuous conformational changes.

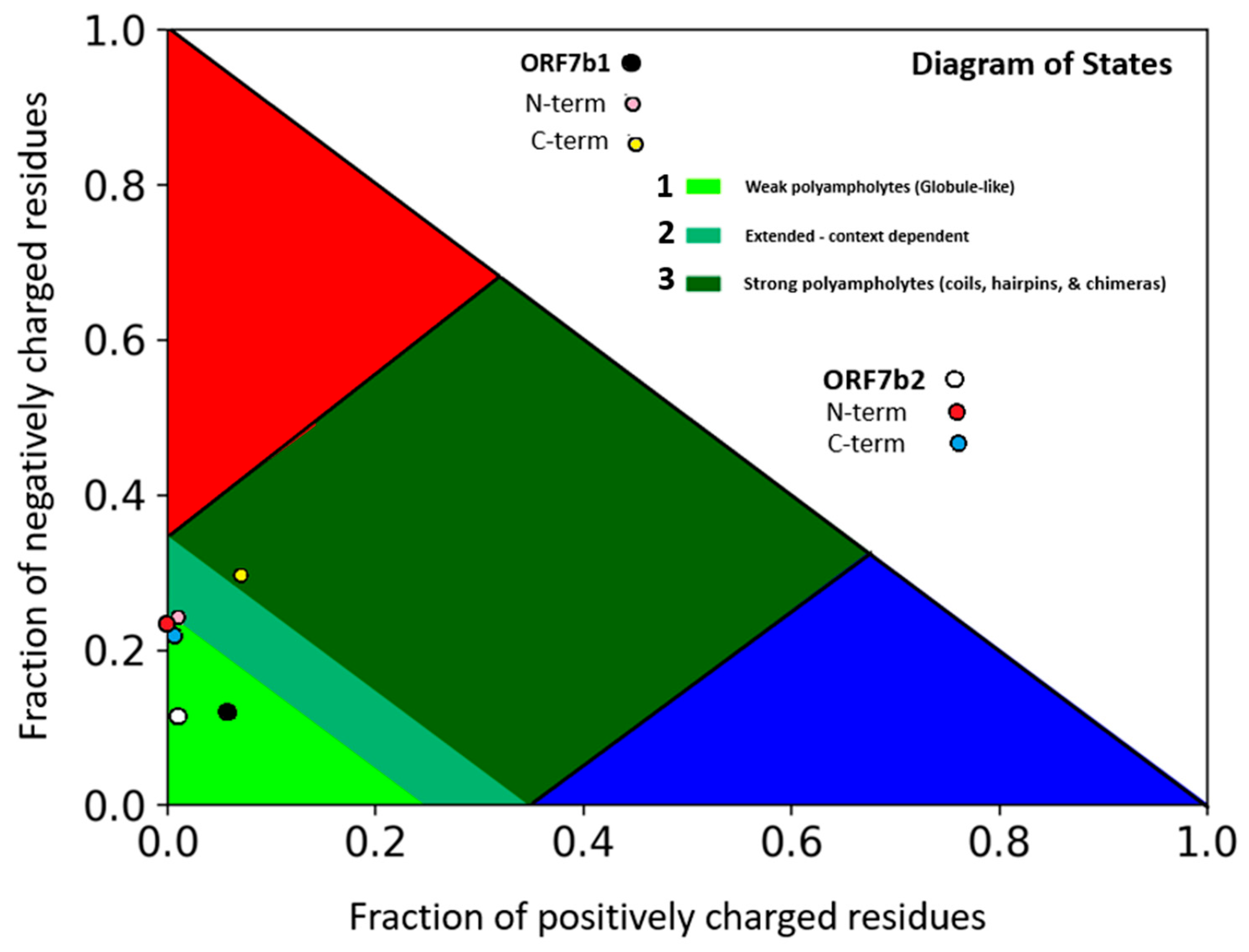

Ramachandran plots of ORF7b2 and ORF7b1 for both their models illustrate in more detail some points already discussed. The plot displays the combinations of psi and phi dihedral angles of amino acid residues within a polypeptide structure and thus identifies all conformations [

92]. They show which dihedral angles are best suited for a α-helix and possible steric conflicts. All models show many terminal residues with angles Φ and Ψ not suited for an alpha helix. Figures 9A and 9B show these residues in areas not characteristic of alpha helical organizations, extended and beta-sheet, where we can recognize that many of them are involved in the terminal segments of both proteins.

Figure 9.

A–Ramachandran plots of the two 3D models of ORF7b2. The various residues with anomalous angles in the “extended” zone are all in the terminal sequences. Both modeling systems produced similar results. Correct alpha-helical residues are concentrated in the alpha zone [Φ -60° and Ψ -50°]. 3 Glu (top) and 20 Leu (low) are outlier residues. B–Ramachandran plots of the two 3D models of ORF7b1. We can see residues with anomalous angles are quite spread out, and many are in the terminal sequences. Residues in red are outliers.

Figure 9.

A–Ramachandran plots of the two 3D models of ORF7b2. The various residues with anomalous angles in the “extended” zone are all in the terminal sequences. Both modeling systems produced similar results. Correct alpha-helical residues are concentrated in the alpha zone [Φ -60° and Ψ -50°]. 3 Glu (top) and 20 Leu (low) are outlier residues. B–Ramachandran plots of the two 3D models of ORF7b1. We can see residues with anomalous angles are quite spread out, and many are in the terminal sequences. Residues in red are outliers.

This justifies the non-helical organization of the tails. If instead we focus on which residues are present in the characteristic region of the alpha helix (around Phi - 50 and Psi - 50) we find ORF7b1 more represented with a group of residues (9Phe, 12Cys, 13Phe, 16Phe, 17Leu, 19Phe, 21Val, 23Ile, 25Leu, 26Leu, 28Phe) with characteristic helical angles. While ORF7b2 is less represented by helical residues (13Phe, 17Leu, 18Leu, 21Val, 22Leu, 25Leu) suggesting a shorter segment or interruptions.

The analysis of the charge distribution suggested that the tails of both proteins were neither helical nor immersed in the membrane. The modeling systems also confirmed the non-helical organization, likely mobile and free-floating. While supporting the general view, the distribution of the helical residues in the Ramachandran plots differs.

Emerging from the picture is that ORF7b2 shows many structural aspects exceeding those of a transmembrane protein, irrespective of ORF7b1’s characteristics. Although we cannot exclude its involvement in membranes, ORF7b2 possesses chemical-physical and structural characteristics that suggest its involvement in other locations of the cell, or a different way of relating to the membrane. This perplexity increases when one considers both terminal segments are disorganized, charged, and suggested rather mobile.

3.4. The Representation of Non-Covalent Interactions by Graph Theory

What appears so far is that the classical representation as a transmembrane protein does not explain the notable success of ORF7b2 in interactions with proteins of the human proteome in diverse functional environments. Therefore, it is necessary to resort to deeper analyses at the residue level.

A protein is a collection of residues (or groups of residues) with some pattern of contacts between them. Let us think for a moment about the diffusion of structural information through a structure like the one of the ORF7b type. At first glance, we think that all interactions between residues in the network must occur at the same level. But the actual situation is often different. The actual relationships between parts of the structure occur within groups (clusters) or between different groups, and therefore we cannot understand them unless we consider we are studying a network model that reflects a clustered structure. This type of structural organization is necessary to ensure segmental dynamics of the molecule and, therefore, the functional flexibility. When a residue needs to diffuse its structural information to its neighbors, the structural information will select the structural cluster (or subgroup) of residues that is interested in that content of the information needed to minimize the energy and stabilize the structure. Representing the protein as a single network of similar interactions will thus result in faulty conclusions and predictions of the system’s real dynamics. This is also consistent with the energetics associated with the geometry and topology of hydrogen bonds in helices, which, although appearing like each other, have different energetic stability coefficients for each bond [

93].

The most correct way to proceed is to identify the residue groups by tracing the inter-group interactions and then manage the process of diffusion of the interactions through a multilayer approach (i.e., between clusters). In this way, we can also classify the importance of individual residues, or groups of residues, in the protein through topological analyses, for example, betweenness centrality. As we will see below, ORF7b1 and ORF7b2, two apparently similar viral proteins, have instead a different structural organization.

Residue Interaction Network (RIN) Analysis

Representing a protein as an interactome (a graph), or better as a Residue Interaction Network (RIN), allows us to unravel its properties at the atomic or residue level [

94,

95]. Each node in the graph represents a residue of the protein, and the edges represent the non-covalent interactions that stabilize the three-dimensional structure of the protein. Calculations of network and topological parameters can identify the building blocks of a protein’s architecture. Experimental evidence has shown that protein residues communicate through non-covalent interactions [

96] or through changes in their local atomic fluctuations [

97]. The RIN analysis identifies the physico-chemical representation of non-covalent interactions at an atomic level in protein structures [

98]. Proteins, as biomolecular systems, show structure-encoded dynamic properties that cause their biological functions [

99]. These properties depend on the topology of the native contacts, which have several degrees of freedom in equilibrium conditions. The range of degrees of freedom extends from small fluctuations in atomic position to the collective motions of entire domains, subunits, and molecules [

100]. In a single helical structure, intramolecular interactions, which depend on the features of the 3D structure of the molecule, dominate the motions and are structure-encoded [

101]. Therefore, the native contact topology plays a dominant role in defining local collective movements and lends itself very well to analytical treatments to define the collective modalities of specific architectures [

102]. RIN analysis processes “conformational states” of proteins starting from pdb files, also including molecular dynamics simulations and collecting structural ensembles. The system generates probabilistic networks through conformation-dependent contact maps. We have used RING4.0 (Residue Interaction Network Generator4.0:

https://ring.biocomputingup.it/), a platform which can handle data that represents the interactions between residues, considering the possible conformational changes or multiple forms of the molecule [

71,

103]. This implies that RING4.0 processes multi-state structures, through molecular dynamics and structural ensembles. It identifies non-covalent interactions at the atomic level and treats the dynamic of each individual interaction within the dynamic characteristics of the entire structure, identifying interactions at the atomic level. The results show synchronized and interactive side-by-side view of the networks and structures. RING4.0 employs a probabilistic graph structure: protein residues are nodes, their weighted edges representing contact frequency, thus offering a novel approach to structural data analysis. Here, we show RIN representations of intra-chain contacts between residues of the best PHYRE-2 pdb models of ORF7b1 and ORF7b2. Contacts are based on a distance cut-off, from 0.5 Å for Van der Waals up to 6.5 Å for π-π stacking.

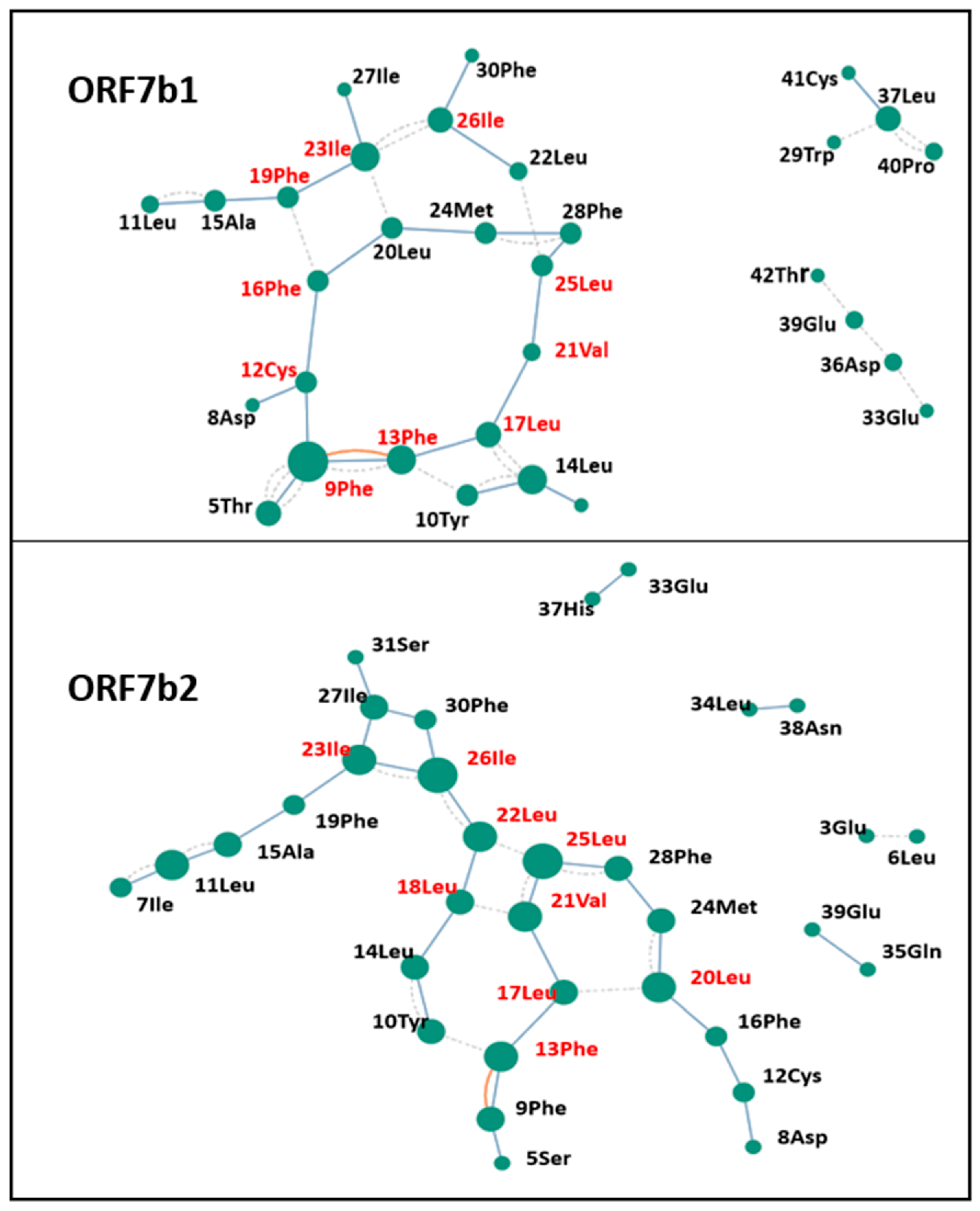

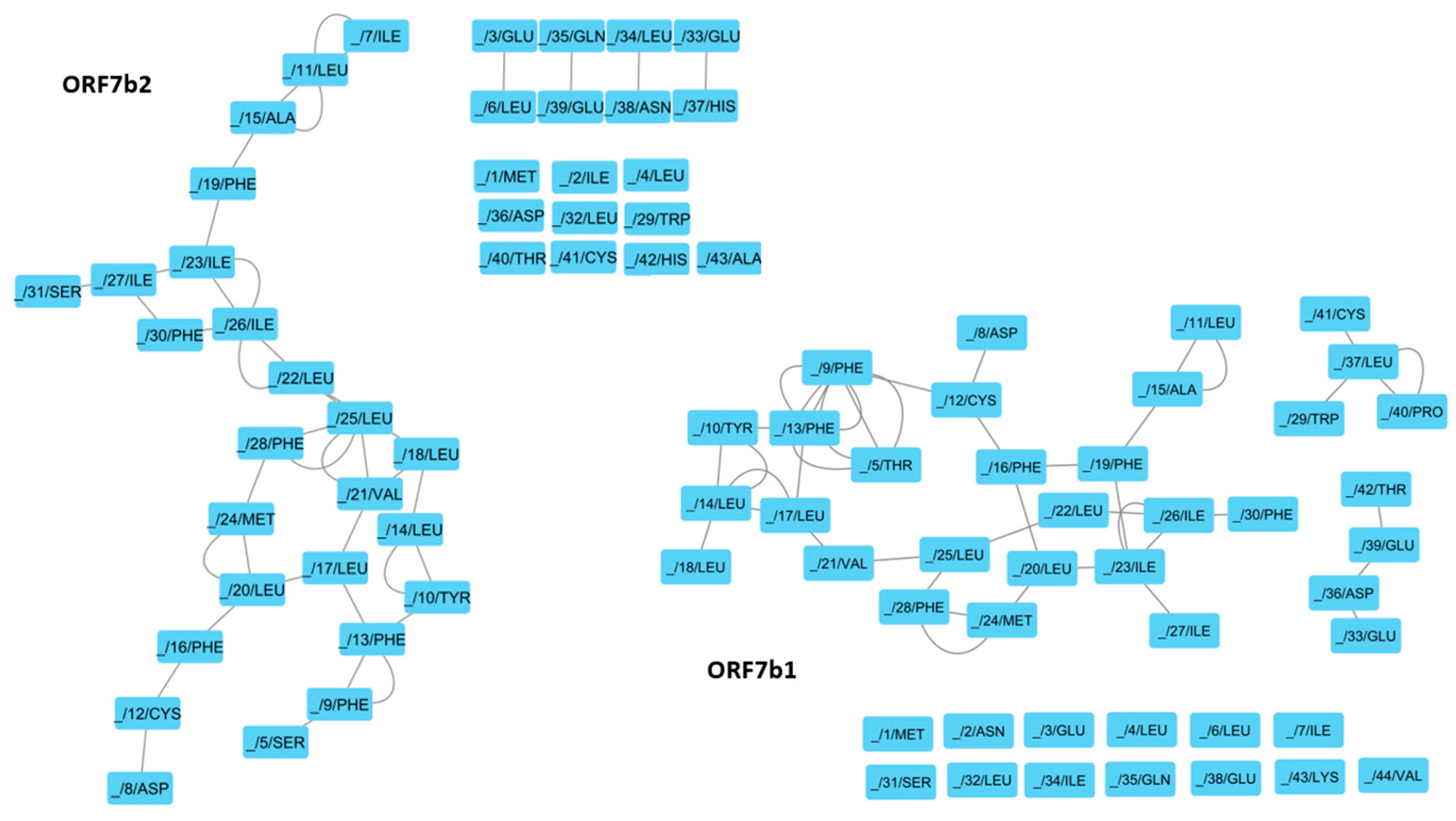

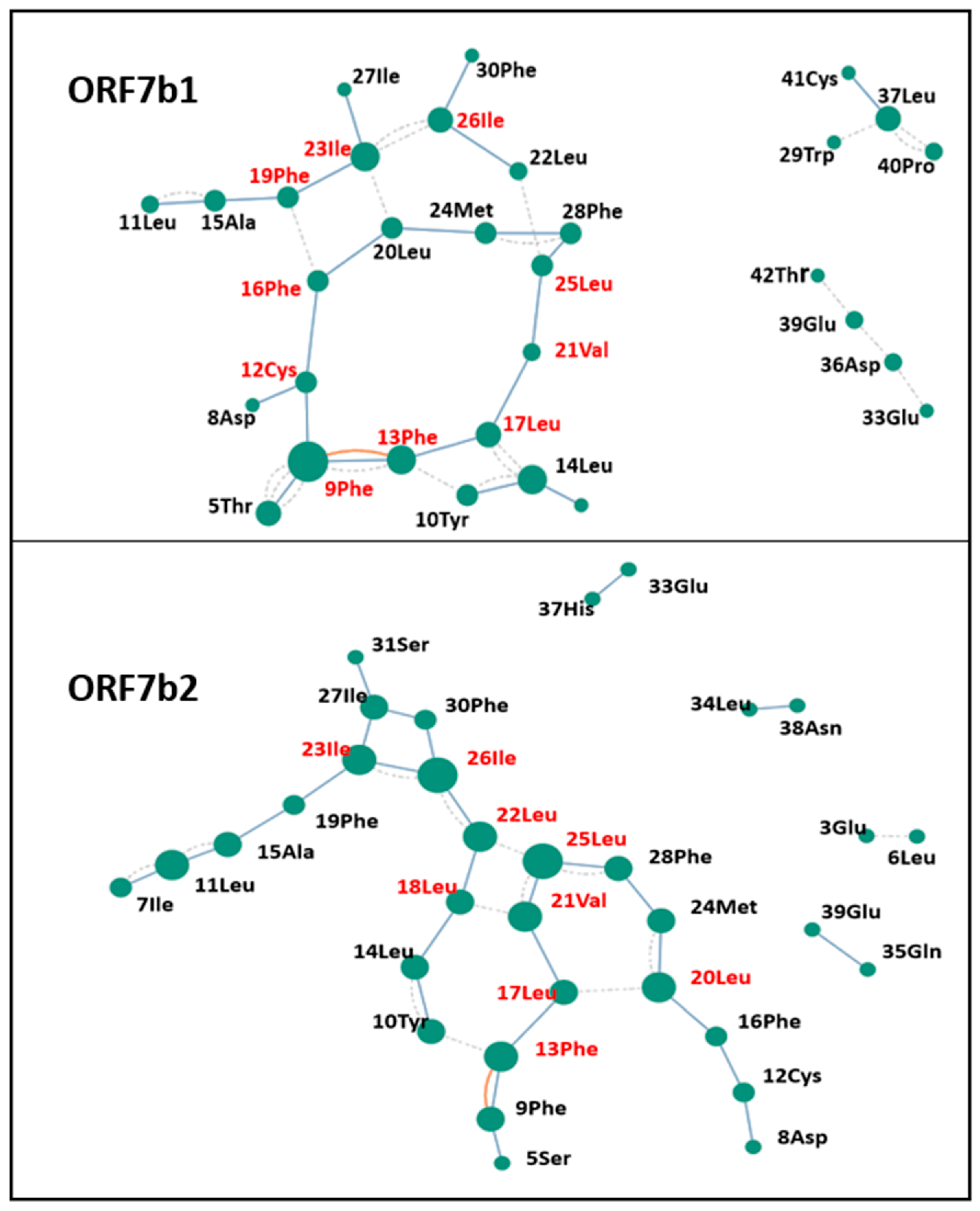

Figure 10 shows the RIN models, which illustrate through a probabilistic graph mapping the molecular contacts of each protein residue. RING analysis provides an effective tool for exploring protein flexibility through the study of weak molecular interactions between residues (H-bond and van der Waals). By monitoring the density of interactions and the centrality of nodes, it is possible to get information on the structural dynamics of proteins. From each network, we identified residues with high connectivity, crucial for the stability of the regions of high structural complexity (

Table 4) of the two molecules, and compared them. We also calculated with Cytoscape the betweenness centrality, a topological property of the nodes of a network. The control that the nodes with higher centrality exert on passaging information between the other nodes gives its influence within a network. Therefore, the organization of these important nodes reflects the properties and architecture of the protein of which they are part (see

Table 5).

While peripheral residuals, with fewer connections, represent mobile and flexible regions. Therefore, a high interconnectivity of these interactions may show a rigid and stable region of the protein. Conversely, areas with few interactions or disconnected residues can suggest more flexibility. Regions with weaker or fewer interactions are often outside the structure and more flexible. Therefore, calculating topological metrics, such as betweenness centrality (

Table 5), is important to identify key residues crucial for the protein stability, because significant high-betweenness residues showed a high correlation with experimentally proven interaction hotspots [

105]. These residues exhibit a high degree, shorter paths between protein chain nodes, and a widespread distribution throughout the protein (see

Table 4). ORF7b1 shows a structural organization formed by three sub-graphs that reflect the organization of the molecule. We can appreciate three contiguous regions formed by residues (19Phe-23Ile-26Leu-22Leu-25Leu-28Phe-24Met-20Leu-16Phe), (28Phe-25Leu-21Val-17Leu-13Phe-9-Phe-12Cys-16Phe-20Leu-24Met) and (17Leu-14Leu-10Tyr-13Phe) with two sides in common, (16Phe-20Leu-24Met-28Phe-25Leu) and (13Phe-17Leu). They contain all the Hub residues critical for the management of stable structural areas (

Table 2). Therefore, the set of these residues describes which residues are involved in keeping the ORF7b1 structure compact (

Table 5). The graph also shows two unconnected sub-graphs of four residues each; their mobility results from a lack of molecular interactions that constrain the residues to the rigid central area. While the ORF7b2 graph shows two contiguous regions formed by residues (19Phe-23Ile-26Ile-22Leu-25Leu-28Phe-25Leu-24Met-20Leu-16-Phe) and (28Phe-25Leu-21Val-17Leu-14Leu-10Tyr-13Phe-9Phe-12Cys-16Phe-20Leu-24Met) with only a side in common (16Phe-20Leu-24Met-28Phe-25Leu). Even in this case, they contain all the crucial residues critical for the management of the stable structural areas and the interactions involved in keeping structural elements of the ORF7b2 structure compact (

Table 4 and 5). In ORF7b1, we also found three pairs of disconnected residues. The lack of molecular constraints with the rigid central group makes them more mobile.

It is interesting to note that all the alpha helical residues found in the Ramachandran plots are present among the crucial residues of the two proteins. This supports the importance of the central helical segment for the stability of both proteins. The graph in

Figure 11 shows the many unconnected residues and visualizes the organization of the compact structure containing the critical residues according to Cytoscape. The lack of weak molecular interactions in about half of the residues of both molecules suggests that the less stable and more flexible regions are quite extensive.

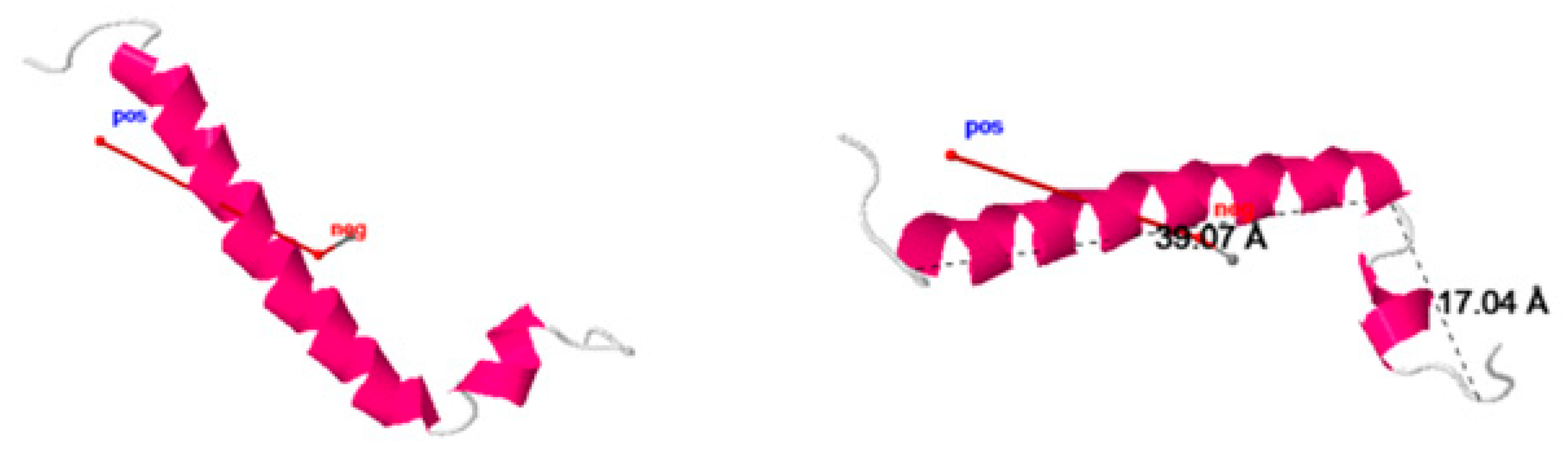

To explain the roles of key residues, we plotted their positions on the three-dimensional structures of the two proteins (

Figure 12). Distributing residues with high centrality show two different structural organizations for the two proteins. ORF7b1 has a well-organized distribution that covers the central helical segment, creating a compact network that goes from residue 9 to residue 26. The presence of H-bonds and van der Waals forces stabilizes and rigidifies the helical segment, supporting its functional role as a transmembrane helix [

106]. The two tails lack residues with high centrality and many weak molecular interactions are missing, thus rendering them less constrained and mobile. ORF7b2 has a very different distribution. The major segment containing the centralized residues is shorter. It stabilizes and stiffens the structure from 17 to 26. In the central helix we have two breakpoints, 14-16 and from residue 27 onwards, where there is a lack of stabilizing molecular interactions. While the phenylalanine 13, which appears to be isolated, forms a π-π stacking with phenylalanine 9. The stacking should somewhat stabilize the relative positions of these two residues. Small clusters, disconnected from the rest of the molecule and, therefore, with independent local flexibility, organized into independent sub-graphs, or clusters. They are in the C-terminal segment. Overall, ORF7b2 is a protein with a rather small central rigid segment, which should allow various types of movements to the structure, which is therefore much more mobile than the previous one if we also consider in this case the high mobility of the two ends. The native contact topology plays a dominant role in defining these local collective movements and lends itself very well to analytical treatments to define the collective modalities of particular architectures [

102]. In conclusion, these results show that the two proteins have quite different structural organizations and mobility characteristics, and both have about half of the residues disconnected from the more rigid and stable part. These subsets of residues form independent subgraphs or clusters. They represent small clusters disconnected from the rest of the molecule and, therefore, with independent local flexibility. In structural terms, these residues are part of the total covalent structure but do not exchange weak bonds with other residues and are independent and not constrained. Therefore, they do not participate in the structural stabilization of the central part of the molecules, nor in their conformational dynamics.

These results support the considerations regarding the ends of both 3D models, with few structural constraints and with residues endowed with greater mobility. Yet, they offer two proteins structured differently at their core. ORF7b1 has a rigid and stable central helical segment, while ORF7b2 shows a compact but shorter helical segment. This should allow the protein a greater range of local and segmental motion. There remains, therefore, a need to better define the segmental characteristics of ORF7b2.

3.5. Phase Diagrams

An interesting aspect of these proteins is a propensity for liquid-liquid phase changes. Studies show ORF7b2’s involvement in activities with viral proteins known for droplet formation [

107,

108,

109,

110]. Disordered residues, of which they contain a substantial amount (See Section 2.1), drive phase transitions in proteins [

111,

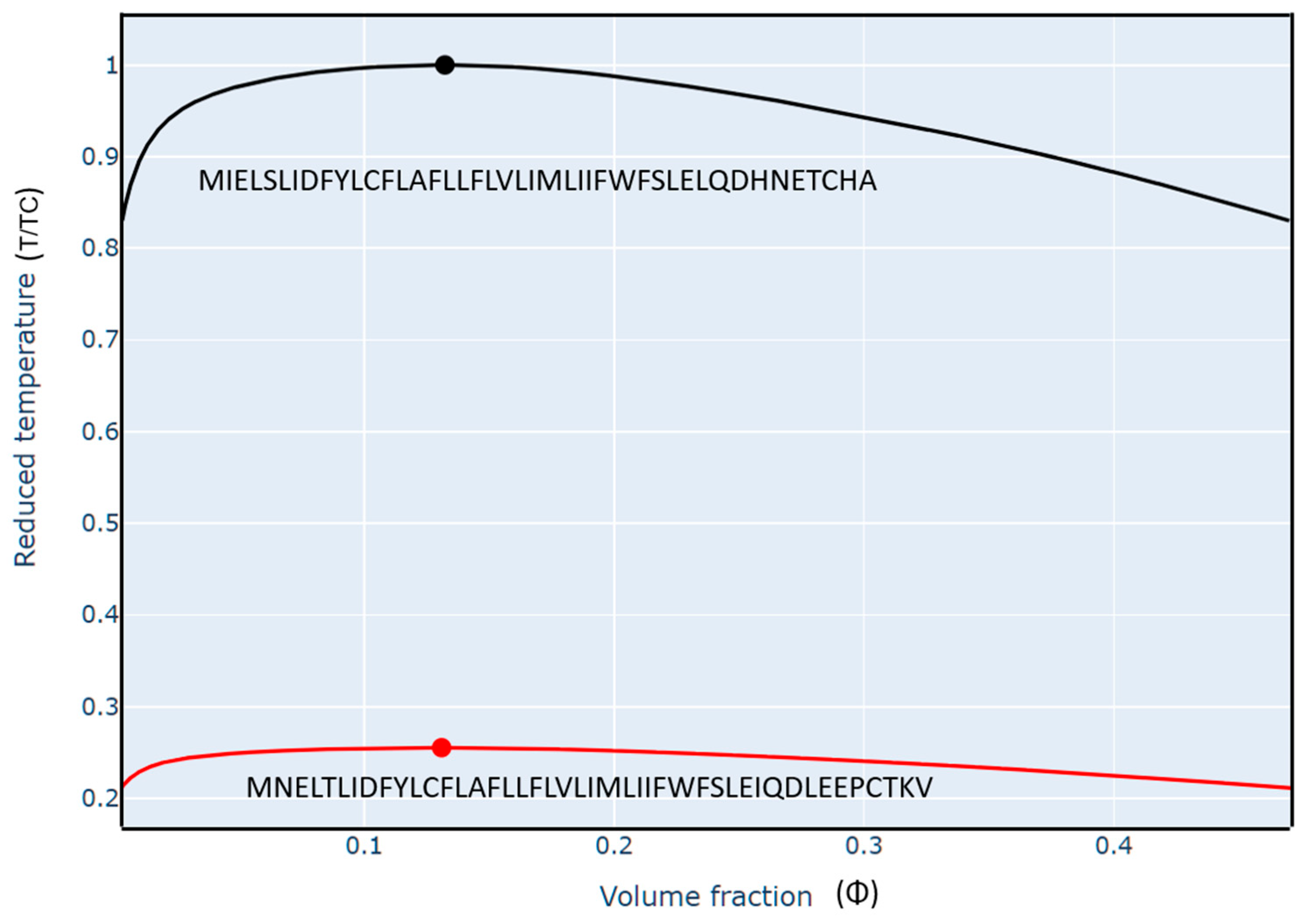

112]. We performed our analyses on the FINCHES web server at Washington University (St. Louis, USA) which was developed to predict IDR-mediated intermolecular interactions using sequences. This approach enables the direct prediction of phase diagrams, and a route to develop and test mechanistic hypotheses regarding protein functions in molecular recognition. The liquid-liquid phase diagram helps to understand the range of optimal stability and functional conditions of intermolecular interactions. It describes the temperature, concentration, and pH ranges, at which the protein maintains its structural and functional stability as a droplet. If the protein is outside its optimal phase range, it may change shape, losing its ability to perform its role. Therefore, evaluating the phase diagram of proteins is crucial for understanding protein-environment interactions and their function regulation. However, using this approach, we can only qualitatively predict how sequence differences will alter the relative diagrams when compared to each other. The diagrams in

Figure 13 report temperature normalized by the critical temperature of ORF7b2 as a reference sequence (T/TC) and concentration as volume fraction (Φ).

To construct the predicted phase diagrams, algorithms first calculate the overall mean-field homotypic intermolecular interaction parameter, which illustrates the different physical phases of a single protein under varying conditions of temperature and volume fraction (concentration). Diagrams visually illustrate how the protein’s state changes as these conditions are altered. The reduced temperature is a normalized temperature and, because of this, the absolute value of the reduced temperature is meaningless other than comparing sequence 1 to sequence 2. However, if we know the phase behavior of sequence 1, we can use this to assess whether we should expect sequence 2 to behave similarly or differently. The diagram is a useful tool for understanding and predicting the behavior of protein organization under different circumstances. Here we are comparing two sequences that differ in terms of mutations. Thus, we can assess if and how mutations are expected to affect phase behavior. It is important to understand that these phase diagrams describe the phase behavior qualitatively, not predict the phase boundaries quantitatively. Knowing the phase diagram of ORF7b1 and 2 helps to understand how and when these two proteins respond to changes in variables. This allows us to understand both the differences between proteins when they act in specific environmental conditions and to highlight their predictable behaviors. In addition, the phase diagram could provide information about the concentration, temperature, and pH conditions (in cells also the crowding) under which these proteins participate in liquid-liquid phase changes [

114,

115]. The diagrams show that the surface area under the curve of ORF7b2 is much larger than that of ORF7b1. This surface area represents the thermodynamic conditions under which molecules can form droplets. Outside the curves, molecules are free in solution. At defined concentrations near the boundaries, inside the curves of both proteins, the first enriched liquid droplets appear, which intensify in the center, in the area below the critical temp. At even higher concentrations, as typically found inside cells (>300 mg mL−1 macromolecules), additional phases such as lamellae or others may appear. Above the upper critical temperature (the top of the “parabolas” in Figure13), everything is well mixed, a single liquid phase, regardless of concentration.

These equilibria lead to the formation of membrane-free organelles, also known as condensates. Scientists increasingly recognize these separation phenomena as crucial mechanisms for subcellular organization and the functioning of different cellular functions [

116]. These droplets can function as membrane-free organelles, concentrating specific proteins and other molecules to facilitate biochemical reactions or signaling processes. From the comparison of the phase diagrams, ORF7b2 shows a greater tendency to concentrate as droplets than ORF7b1. In fact, we do not have real parametric evidence, i.e., specific and direct quantitative conditions of variables that tell us exactly under which physiological conditions, or to what extent, the two proteins participate in the formation of cellular droplets through liquid-liquid phase separation in the real cell. We only have qualitative and comparative indications of the differences between the two proteins. Thus, we must be cautious in attributing specific roles. The predictive behavior of a protein does not directly translate into in vivo behavior because of the complexity of the cellular environment (presence of other molecules, competitive interactions, post-translational modifications, macromolecular crowding). However, we can consider that in vivo ORF7b2 interacts physically with the N (see in BioGRID). Our recent article [

9] demonstrated via interactomic analysis that ORF7b2 functionally interacts with the nucleoprotein N, which is very well known as a droplet inductor [

117,

118]. But N physically interacts also with NSP3 protein [

119,

120] and with many other viral proteins (

https://thebiogrid.org/4383847/summary/severe-acute-respiratory-syndrome-coronavirus-2/n.html). The formation of droplets has only been observed in RNA viruses [

117] and the proteins’ multivalency is indispensable during liquid-liquid phase separation, facilitating the formation of membraneless droplets [

121,

122]. This ability appears to be important for viral replication, virus assembly, and regulation of the immune response. Some studies show that the N protein through condensates organizes the genetic material of the virus, increasing the efficiency of its replication [

123]. In addition, its interaction with viral RNA and cellular proteins suggests a role in modulating the intracellular environment in favor of infection [

121,

122]. Other proteins, among the non-structural proteins, such as NSP3 and NSP12, can interact with viral RNA contributing to the formation of biomolecular condensates [

124]. A study suggests that protein ORF6, also affects cell compartmentalization and droplet formation [

125]. According to another article [

10], multiple groups of viral proteins, including N, NSP3, ORF6, ORF8, ORF9b, and ORF7b2, interact with single human proteins. The continuity and multiplicity of these reciprocal interactions between ORF7b2 and viral proteins directly involved in the formation of droplets in human cell, suggest a role also for ORF7b2 in the formation of biomolecular droplets, through liquid-liquid phase separation. It is also possible that other molecules start phase separation, with ORF7b2 acting as a modulator, influencing droplet properties.

3.6. Dynamic Properties of ORF7b2

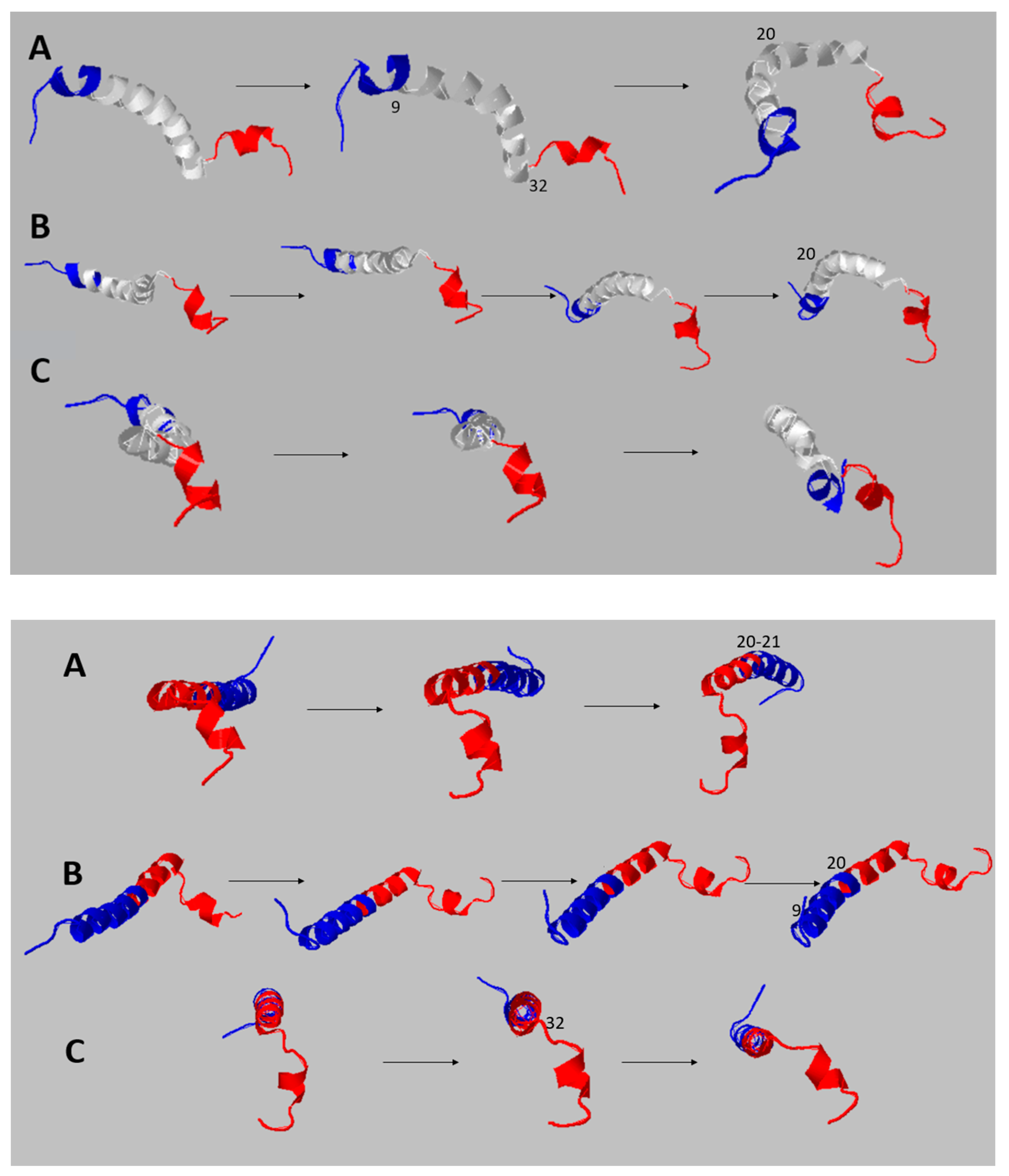

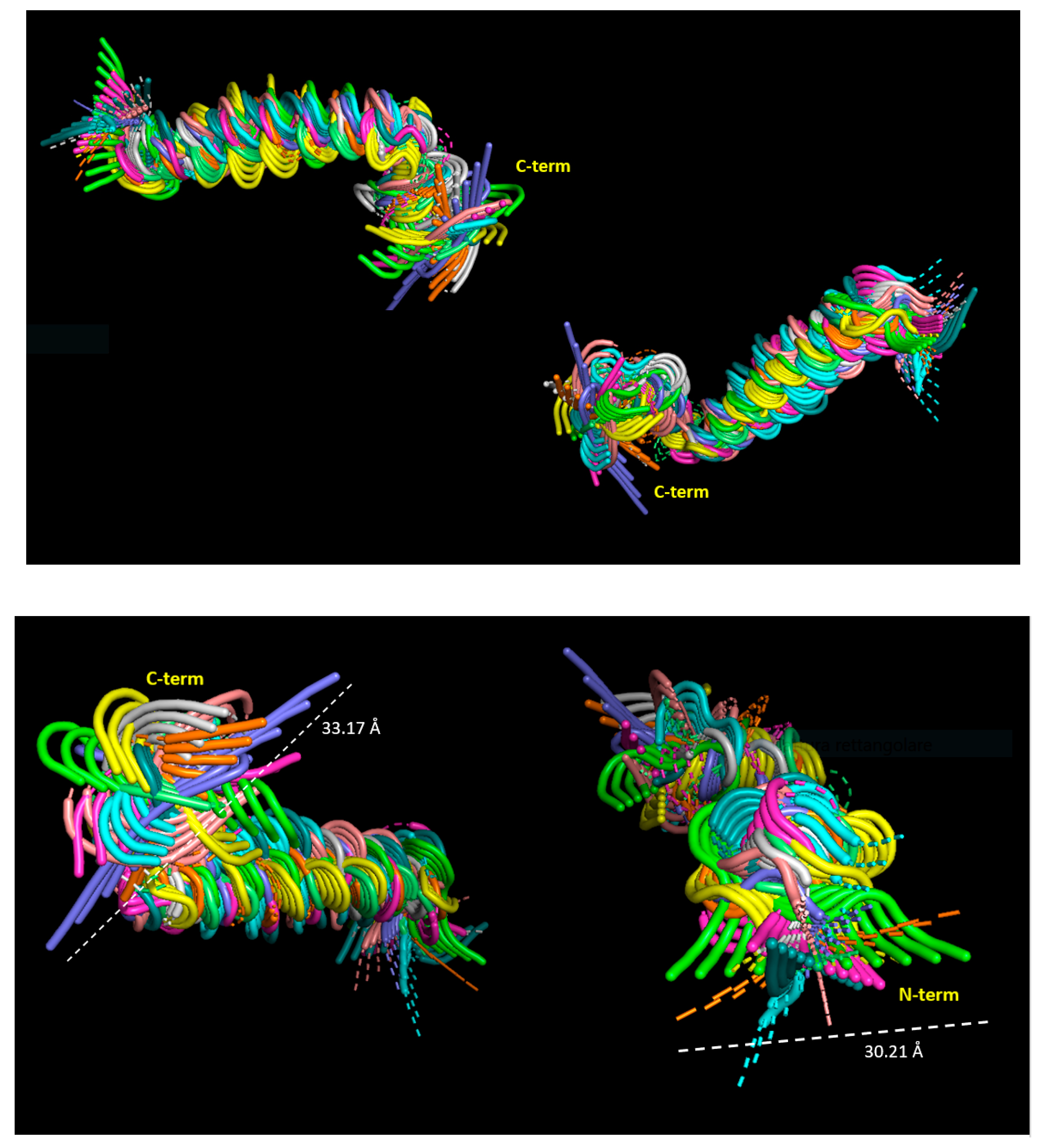

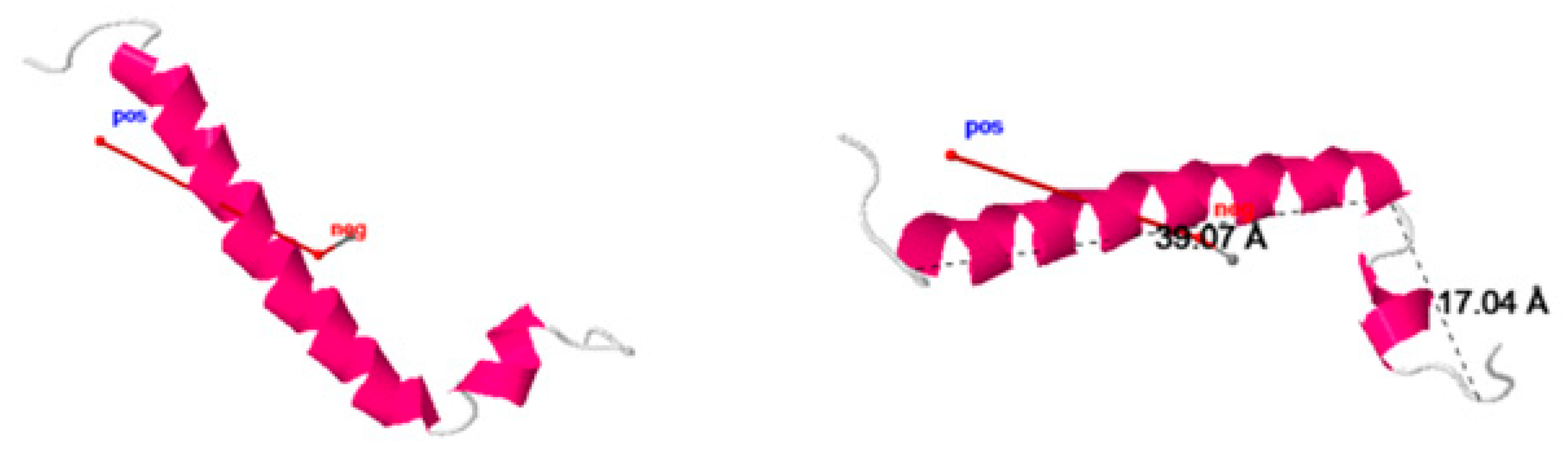

Most of the functional activities of a protein reflect a wide temporal scale of movements, from the very rapid ones (from sub-picoseconds to microseconds), such as conformational changes, segmental flexibility, and rapid folding/unfolding, until the low-frequency movements characterized by collective atomic fluctuations along structural hinges [