Submitted:

17 April 2023

Posted:

18 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. What is spatial capital?

3. Accessibility, availability and adequacy, and the relationship between them

R: You don't have anything here. No baker, no butcher. You have to say: nothing, nothing, nothing. Really sad.I: It used to be ?R: There was a shop, yes. A butcher in the past, a baker. But now, nothing, nothing. But you just get it though. (...) It is a sad village. I say it: there is nothing here, nothing, nothing.(Owner, Westhoek, v, 80 years)

I:What do you miss most about the village?R:I miss that there is nothing of shop. A butcher and baker, yes. But that there is nothing to get a shrill ham or cheese ...(Owner, Westhoek, v, approx. 70 years)

I: And to the store? Do you also do that on foot?R: Yes, but that's more difficult. Here you have... I'll say, no cheap warehouses... near. You do have a [small shop] here, but that is expensive there. There on the Zwijnaardesteenweg in Nieuw-Gent, you also have a [small shop], also such an Express. And yet they charge for the same thing here, another ten cents more than there. While that is also expensive there. Of course, if you go to the Aldi or the Lidl once, you are much cheaper and you have also eaten well.I: And where do you go to the Lidl?R: That's too far for me... I can't drag that far huh. And that's the problem.(Private tenant, city, m, 62 years)

That's a real drama. When I walk here in Drongen, I always go to the side so that I see the cars coming. Because there are so-called footpaths, you see that here too. Those are footpaths, but you can't step on them. Certainly not when you are older. There are those roots of those trees. There are stones there, with that one person it is pits and mountains because nobody does anything about it. (...) Or there are cars on it, which also happens very often. (Owner, outskirts of town, v, 84 years)

I: Do you have any neighbors?R: No. Well, yes, there that farm, at the beginning of the street. And there. But yes. It's a little further. That might be... for later... a minus. If anything... that you don't... yes, you can call of course. But you can't go outside and shout or raise your hand, you can't. That is perhaps a minus, that I do not have close neighbors.(Owner, Westhoek, v, 60-65 years)

Rv: But there are a lot of houses for sale and I think that's why... Roesbrugge is a bit out of the question. (...) Because it's far from work. (...)Rm: Of my class, only four have continued to live in Roesbrugge. They're all gone huh. Ghent, Antwerp, Brussels. The work is there. All those who have learned and with a nice job.Rv: And the youth too huh. There is no work here. Here five kilometers further there is a factory. Eurofreez, potato processing they do. There are still a lot of people working there. But yes, they are all... you don't have to have studied to work there.(Owner, Westhoek, f&m, 62 years)

4. Conclusions

References

- Alter, L. (2021). The issue for boomers won’t be ‘aging in place’. Available online: https://liveplayworkdotnet.wordpress.com/2021/07/25/ the-issue-for-boomers-wont-be-aging-in-place/.

- Beke, W. (2019). Beleidsnota 2019-2024. Welzijn, volksgezondheid, gezien en armoedebestrijding. Brussel: Vlaamse Regering.

- Beke, W. (2021). Zorgzame buurten. Inspiratiekader bij projectoproep. Available online: https:// www.zorgenvoormorgen.be/sites/default/files/media/20210610_inspiratiekader_FINAAL.pdf.

- Blaauboer, M., Mulder, C.H. & Zorlu, A. (2011). Distances between Couples and the Man’s and Woman’s Parents. Population, Space and Place 17(5): 597-610.

- Bourdieu, P. & J.-C. Passeron (1970). La reproduction. Éléments pour une théorie du système d’enseignement. Paris: Éditions de Minuit.

- Brandt, M., Haberkern, K. &M. Szydlik (2009). Intergenerational help and care in Europe. European Sociological Review, 25(5): 585–601.

- Bronselaer, J., Demeyer, B., Vandezande, V. & Vanden Boer, L. (2018). Wat weten we (niet) over informele zorg in Vlaanderen? Voorstel voor het dichten van de cijfer- en kennislacunes. Brussel: Departement Welzijn, Volksgezondheid en Gezin.

- Cant, J. (2019). Food inaccessibility in Flanders: Identifying spatial mismatches between retail and residential patterns (PhD Dissertation). Antwerpen: Universiteit Antwerpen.

- De Decker, P. (2013). Eigen woning: geldmachine of pensioensparen? Antwerpen: Garant.

- De Decker, P., Vandekerckhove, B., Volckaert, E., Wellens, C. & E. Schillebeeckx (2017) : Thuisverpleging rijdt 15 keer per dag de wereld rond, Knack.be, 7 nov.

- De Decker, P., Vandekerckhove, B., Volckaert, E., Wellens, C. & E. Schillebeeckx (2018). Ouder worden op het Vlaamse platteland. Over zorg, wonen en ruimtelijk ordenen in dun bevolkte gebieden. Antwerpen: Garant.

- De Decker, P. & E. Volckaert (2020). Oud, arm en huurder. Een verkenning van de woon- en zorgperspectieven van kwetsbare stedelijke ouderen. Oud-Turnhout/’s-Hertogenbosch: Gompel&Svacina.

- Degadt, P. (2017). Of we dragen meer bij, of we aanvaarden dat ouderen in onze samenleving worden verwaarloosd. Interview door Peuteman, A. & S. Demeulemeester. Opgehaald van. Available online: https://www.knack.be/nieuws/gezondheid/of-we-dragen-meer-bij-of-we-aanvaarden-dat- ouderen-in-onze-samenleving-worden-verwaarloosd/.

- De Labra, C., Guimaraes-Pinheiro, C., Maseda, A., Lorenzo, T. & Millán-Calenti, J. (2015). Effects of physical exercise interventions in frail older adults: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials Physical functioning, physical health and activity. BMC Geriatrics, 15-1: 154.

- Dreesen, S. & Vastmans, F. (2020). Jongvolwassenen op de woningmarkt. Timing en locatie. Leuven: Steunpunt Wonen.

- Falck, R., Davis, J., Best, J., Crockett, R. & Liu-Ambrose, T. (2019). Impact of exercise training on physical and cognitive function among older adults: A systematic review and meta- analysis. Neurobiology of Aging, 79: 119-130.

- Federaal Planbureau en Statbel [Algemene Directie Statistiek] (2018). Demografische vooruitzichten 2017-2070. Brussel: Federaal Planbureau & Algemene Directie Statistiek.

- Federaal Planbureau en Statbel [Algemene Directie Statistiek] (2021). Demografische vooruitzichten 2020-2070. Brussel: Federaal Planbureau & Algemene Directie Statistiek.

- Geelen, K. (2003). Informele zorg voor psychische problemen en verslavingen. Utrecht: Trimbos-instituut.

- Golant, S.M. (2015). Aging in the right place. Baltimore: Health Professions Press.

- Golant, S. (2022). How a resilient older population is better able to age in the right places. Opgehaald van. Available online: https://boomingencore.com/en/article/how-resilient-older-population-better-able-age-right-places.

- Hartt, M., DeVereteuil, G. & R. Potts (2022). Age-unfriendly by design. Built environment and social infrastructure deficits in Greater Melbourne. Journal of the American Planning Association. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2022.2035247 (accessed on 5 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Jambon, J. (2019). Regeerakkoord Vlaamse regering 2019-2024. Brussel: Departement Kanselarij en Bestuur.

- Koelen, M. & M Eriksson (2022). Older people, sense of coherence and community, in Mittelmark, et al. (eds). The handbook of salutogensis. Open access: Springer. Available online: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/978-3-319-04600-6.pdf.

- Kohl, H.W. et al. (2012). The pandemic of physical inactivity: global action for public health. The Lancet 380 (21 July): 294-305.

- Krout, J.A. & K.M. Hash (2015). What is rural? Introduction to aging in rural areas. In Hash, K.M., Jurkowski, E.T. & J.A. Krout (eds.). Aging in rural areas. Policies, Progams, and Professional Practice. New York: Springer: 3-22.

- Kullberg, J. (2010). Gepaste afstand. Over ruimtelijke nabijheid van ouders en kinderen. In: van den Broek, A., Bronneman-Helmers, R. & Veldheer& V. (red.). Wisseling van de wacht: generaties in Nederland. Den Haag: Sociaal en cultureel rapport 2010: 181-202.

- Lawton, M.P. & L. Nahemow (1973). Ecology and the aging process. In: Eisdorfer, C. & M.P. Lawton (eds.). Psychology of adult development and aging. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association: 619–674.

- Lévy, J. (1994). L’espace légitime. Paris: Presses de la Fondation nationale des sciences politiques.

- Menec, V.H. et al. (2011). Conceptualizing age-friendly communities. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue Canadienne du vieillissement 30 (3): 479-493.

- Nelissenn M. (2017). Eindelijk oud. Tielt: Lannoo.

- Nussbaum, M. (2011). Creating Capabilities. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Pisman, A., Vanacker, S., Bieseman, H., Vanongeval, L., Van Steertegem, M., Poelmans, L. & K. Van Dyck (2021). Ruimterapport 2021. Brussel: Departement Omgeving.

- Renard, P., Coppens, T. & G. Vloebergh (2022). Met voorbedachten rade. De sluipmoord op de open ruimte. Tielt: Kritak.

- Rérat, P. (2018). Spatial capital and planetary gentrification: residential location, mobility and social inequalities. In Lees, L. & M. Philipps (eds). Handbook of gentrification studies. Edward Elgar Publishing. Available online: https://www.e-elgar.com/shop/gbp/handbook-of-gentrification-studies-9781839100499.html.

- Sillis, M. (2022). Zelfdoding bij ouderen: ‘Het is toch niet normaal dat mensen uit het leven stappen’. Sociaal.net, 22 april. Available online: https://sociaal.net/achtergrond/zelfdoding-bij-ouderen/.

- Spitzer, M. (2019). Eenzaamheid. De impact van sociaal isolement. Amsterdam: Altas Contact.

- Stones, D. & J. Gullifer (2016). ‘At home it’s just so much easier to be yourself’: older adult’ perception of ageing in place. Ageing & Society 36(3): 449-482.

- Thissen F. & Vanderstraeten L. (2015) Stad of platteland, de verschillen voor ouderen in Vlaanderen en Nederland. Geron, 17(3): 12-16.

- Vandekerckhove, B., De Luyck, N., Volckaert, E., De Witte, N., & P. De Decker (2015): Ook de aangespoelden blijven. Woon- en zorgperspectieven van 80-plussers aan de Kust. Antwerpen: Garant.

- Vandeurzen, J. (2014). Beleidsnota Welzijn, Volksgezondheid en Gezin. 2014-2019. Brussel: Vlaamse Regering.

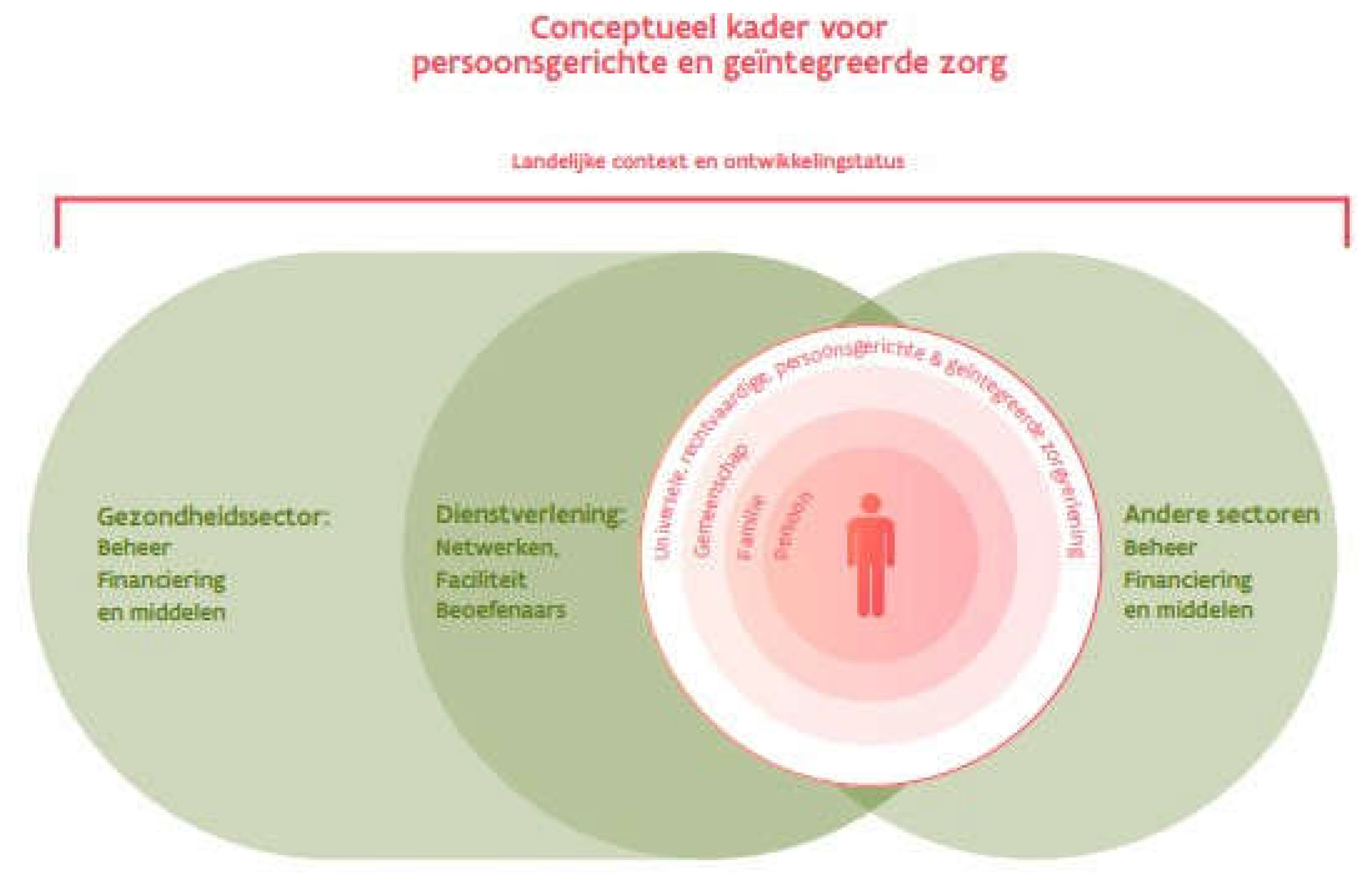

- andeurzen, J. (2016). Conceptnota Vlaams welzijns- en zorgbeleid voor ouderen. Dichtbij en integraal. Visie en veranderagenda. Brussel: Vlaams Parlement.

- Vandeurzen, J. (2018). Zorgzame buurten, Inspiratienota. Brussel: Vlaamse Overheid.

- Vandeurzen, J. (2019). Zorg voor elkaar. Kalmthout: Polis.

- Vaneeckhout, L. (2022). Vergeten land. Een roadtrip door Vlaanderen. Kalmthout: Peckmans.

- Van Vliet, J., van der Plas, S. & J. Gussekloo (2019). Burenhulp, een kans op hulp vlakbij. Geron 21(1): 1-4.

- Verté, E., De Witte, N. & Verté, D. (2018). Ouderenbehoefteonderzoek Gent 2018. Een historische analyse en vergelijkende studie met andere centrumsteden en Vlaanderen. Brussel/Gent: Vrije Universiteit Brussel & Hogeschool Gent.

- Vlaamse Milieumaatschappij (2014). Megatrends: ingrijpend, maar ook ongrijpbaar? MIRA Toekomstverkenning. Brussel: Vlaamse Milieumaatschappij.

- Volckaert, E. (2022). Oud vasthouden. Over wonen, vergrijzing en beleid. Turnhout/’s-Hertogenbosch: Gompel&Svacina.

- Winters, S., Ceulemans, W., Heylen, K., Pannecoucke, I., Vanderstraeten, L., Van den Broeck, K., De Decker, P., Ryckewaert, M. & G. Verbeeck, G. (2015). Wonen in Vlaanderen anno 2013. De bevindingen uit het Grote Woononderzoek 2013 gebundeld. Leuven: Steunpunt Wonen.

- Available online: www.hln.be/koksijde/gemeente-legt-busje-in-naar-geldautomaat~af62cb26/.

- Available online: www.standaard.be/cnt/dmf20190123_04126732.

| 1 | Spatial capital evokes the connotation with Bourdieu's capital concepts. Where the concepts of economic, social and cultural capital (source) are individual characteristics about which a pressowhether or not, or to an unequal extent, the concept of spatial capital refers to the environments in which individual capital may or may not be used. |

| 2 | For example Vandeurzen (2014): "A high-quality living and living environment consists of an accessible, life-course-proof space and neighborhoods with nearby, accessible and available basic facilities, realized in flexible, multi-purpose buildings and framed in a socially acceptable policy of urban and village renewal. By filling in the available space in a high-quality way, we can increase the participation of people in need of care in society, ensure the proximity and accessibility of the services, and initiate and promote social cohesion and a healthy lifestyle.". |

| 3 | The investigations were commissioned by, respectively, the Provincie West Flanders (coast), the Flemish Land Agency (Westhoek and Kempen) and the Policy Research Centre for Housing (urban tenants) and city outskirts). See: Vandekerckhove and Others (2015), De Decker and Others (2018), De Decker & Vockaert (2020) and Volckaert (2022). |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

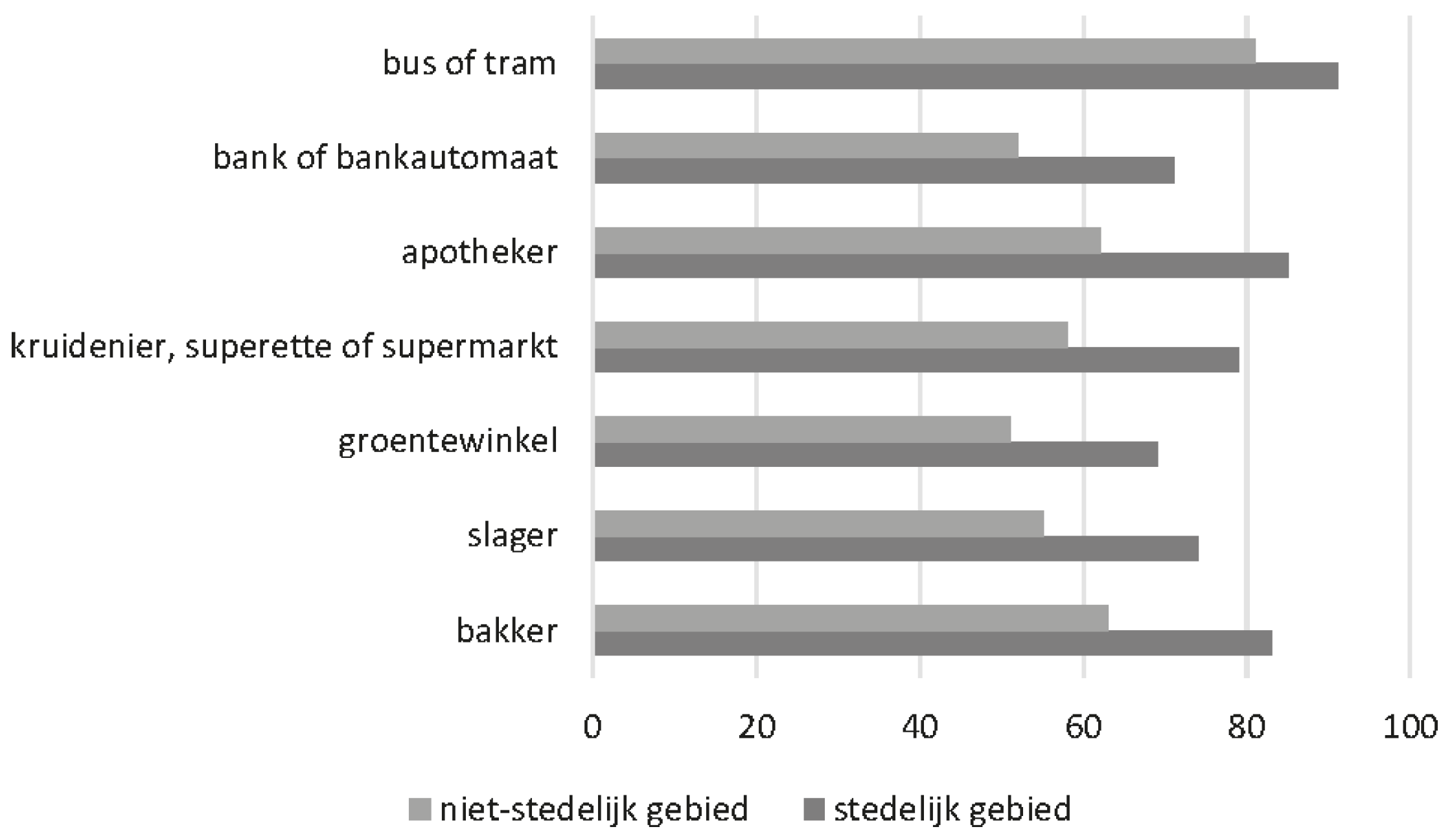

| 6 | Source: Woonsurvey 2018 – calculations K. Heylen (HIVA-KU Leuven). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).