1. Introduction

Kawasaki disease is an acute form of systemic vasculitis and the most common cause of pediatric acquired heart disease in developed countries.1 In Japan, the Kobayashi score is used to predict intravenous immunoglobulin resistance and subsequent complications, including coronary artery abnormalities, in children with Kawasaki disease. This is calculated as follows: 2 points for aspartate aminotransferase of >100 IU/L, sodium of <133 mmol/L, fever lasting <4 days, and a neutrophil count of >80%, and 1 point for C-reactive protein levels of >10 mg/dL, age of <1 year, and a platelet count of <30 × 104/μL.2 According to the Randomized Controlled Trial to Assess Immunoglobulin plus Steroid Efficacy for Kawasaki disease, a score of 5 or more indicates the need to administer steroids from the initial treatment of the disease.3 We report a patient who developed coronary artery aneurysm after relapse following acute treatment for Kawasaki disease, despite the absence of an inflammatory reaction or Kawasaki disease symptoms.

2. Case

The patient was delivered vaginally at 39 weeks 2 days, weighing 2784 g. He was admitted to our neonatal intensive care unit for respiratory distress syndrome. There was no family history of Kawasaki disease and no indications of its presence. At 4 months old, the patient developed a fever the night before admission and was referred to our hospital. He was admitted to the hospital with the chief complaints of fever and poor feeding on the second day of his illness. The patient had a height of 61.5 cm (±1.2 standard deviations), a weight of 6700 g (±0.5 standard deviations), a body temperature of 39.0°C, blood pressure of 104/64 mmHg, a heart rate of 170 beats/min, and oxygen saturation of 100% (in-room air). He showed poor activity, with a pale face and cold extremities. A scattered rash was observed on his trunk. At that time, there were none of other symptoms of Kawasaki disease, i.e., redness of the conjunctiva, redness of the lips, strawberry tongue, cervical lymphadenopathy, or hard edema of hands and feet. The patient’s abdomen was flat and soft, his respiratory sounds were normal, his heart sounds were clear, and no murmur was detected. Laboratory findings comprised a leukocyte count of 25300/μL, a neutrophil count of 75.0%, C-reactive protein levels of 6.98 mg/dL, a platelet count of 52 × 10

4/μL, a sodium level of 135 mmol/L, and an aspartate aminotransferase level of 41 IU/L Treatment with cefotaxime was initiated as a bacterial infection was suspected. On the third day of the illness, the high fever persisted, and ocular conjunctival hyperemia, cervical lymphadenopathy, indeterminate erythematous rash, and indurative edema appeared. As five of the six major symptoms of Kawasaki disease were observed, Kawasaki disease was diagnosed. The patient was started on intravenous immunoglobulin at 2 g/kg and aspirin at 30 mg/kg/day on the third day. His Kobayashi score was 7 points in total. This consisted of 2 point for hyponatremia (129 mmol/L), 2 points for fever lasting 3days (=<4 days), 2 points for elevated aspartate aminotransferase (114 IU/L), and 1 point for his age. In accordance with the Randomized Controlled Trial to Assess Immunoglobulin plus Steroid Efficacy study, intravenous prednisolone at 2 mg/kg/day was administered from the initial treatment. Echocardiography revealed a diameter of 1.5 mm (z score 0.6 [least mean squares method]) for the right coronary artery, a diameter of 1.7 mm (z score 0.4) for the left main coronary artery trunk, a diameter of 1.3 mm (z score 0.0) for the left anterior descending branch, and a diameter of 0.9 mm (z score −1.3) for the left circumflex branch. There were no coronary artery wall irregularities and no obvious increase in luminosity. Left ventricular wall motion was good, and no pericardial effusion or valve regurgitation was observed. The fever resolved on the fourth day of the illness, but on the fifth day, the fever returned (38.6°C). On the same day, a second dose of intravenous immunoglobulin 2 g/kg was administered. The fever resolved on the sixth day of illness, and the patient was afebrile thereafter, with no recurrence of the main symptoms of Kawasaki disease. Around the ninth day, linear erythema of the nail tips, which differed from the previous rigid edema, appeared (

Figure 1).

Echocardiography on the ninth day showed no significant coronary artery abnormalities. On the tenth day of the illness, a blood test showed a C-reactive protein level of 0.35mg/dL, which was normal, and the treatment course was good. On the fourteenth day, the patient’s temperature was 37.1°C, with no fever and no Kawasaki disease symptoms. However, his blood test showed a re-elevation of C-reactive protein to 5.20 mg/dL. The patient was considered to have a relapse of Kawasaki disease and was transferred to a tertiary care hospital for further treatment.

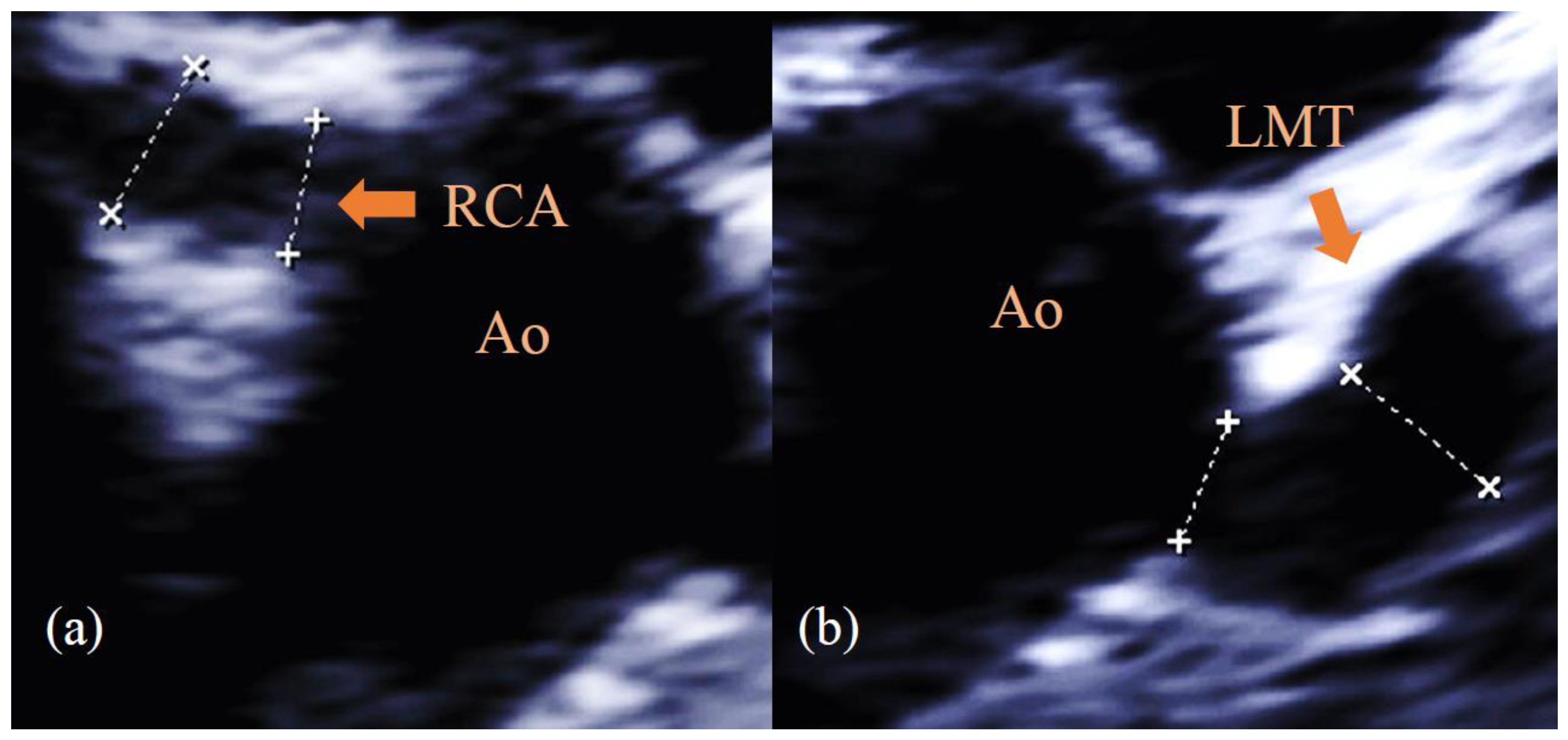

After the patient was transferred, echocardiography showed enlargement of the right coronary artery to 5.0 mm (z score 9.1) and the left main coronary artery trunk to 4.8 mm (z score 8.8) (

Figure 2).

The inflammation from Kawasaki disease was considered to persist, so a third dose of intravenous immunoglobulin 2 g/kg was administered on the fourteenth day of illness, and cyclosporine was given at a dose of 5 mg/kg/day for 6 days. Steroids had been continued at a dose of 2 mg/kg/day, which was halved on the fifteenth day of onset and discontinued on seventeenth day. Thereafter, the coronary aneurysms showed no further enlargement and gradually regressed to normal size. Blood tests on the twentieth day of illness confirmed that C-reactive protein was normal at 0.32 mg/dl. The platelet count was highest at 135.9 x 104/μL on the seventeenth day of the disease and then peaked out. Echocardiographic evaluation on the twenty-eighth day showed residual small-to-medium coronary artery aneurysms, with the right coronary artery having a diameter of 2.7 mm (z score 3.9) and the left main coronary artery trunk, 3.5 mm (z score 5.8). Two antiplatelet agents, aspirin and clopidogrel, were prescribed, and the patient was discharged from the hospital on the thirtieth day. The patient is currently under outpatient follow-up care, and his coronary artery aneurysm has gradually regressed, with no cardiovascular events.

3. Discussions

We have described a case of Kawasaki disease, in which the patient had no symptoms of Kawasaki disease, disappearance of fever, and very low C-reactive protein levels after treatment with two doses of intravenous immunoglobulin and steroid. However, the patient subsequently had a relapse and developed coronary artery abnormalities.

C-reactive protein is an important biomarker of inflammation in Kawasaki disease and is used in the Kobayashi scoring system to evaluate the severity of the disease.2 The prescribed treatment for this patient is based on the Randomized Controlled Trial to Assess Immunoglobulin plus Steroid Efficacy study. High Kobayashi scores indicate the need for steroid use from the early stages of the disease.3 It is known that the inflammatory response, as indicated by C-reactive protein levels, is reduced by steroids in Kawasaki disease.3 Even with low C-reactive protein levels, there is still a risk of coronary artery aneurysms in the acute phase of Kawasaki disease.4 In the present case, it is possible that steroids only partially suppressed inflammation and decreased C-reactive protein, and then inflammation flared up again, resulting in coronary artery aneurysms. When steroids are used during the acute phase of Kawasaki disease, the inflammatory markers themselves may not be an indicator of disease activity. This is a very important observation, well known to those who care for many Kawasaki disease patients, but it may be less well understood by caregivers who do not see so many of these patients.

In this case, coronary artery aneurysms developed despite the complete resolution of the fever. There have been previous reports of cases in which coronary artery aneurysms developed despite the absence of fever.5 In the acute treatment of Kawasaki disease, fever resolution can be achieved earlier with the administration of steroids, infliximab, or cyclosporine in addition to intravenous immunoglobulin.3,6,7 In the present case, systemic administration of steroids might result in early fever reduction. However, although no systemic symptoms were observed, coronary artery inflammation persisted, leading to coronary artery abnormalities. We suspect this may have occurred because it is possible that the timing of the 3 rd line treatment was late. It should be kept in mind that fever may be masked by anti-inflammatory therapies. And too early IVIG may increase the possibility of IVIG resistance, and steroid dose may increase the occurrence of coronary aneurysms.8

The patient in this case report was an infant and it is known that infants generally exhibit less consistent Kawasaki disease symptoms and are prone to greater disease severity.9,10 In this case, the major symptoms of Kawasaki disease were present prior to the start of treatment but, thereafter, Kawasaki disease symptoms were not apparent. It was possible that the age of the patient contributed to the absence of Kawasaki disease symptoms at the time of relapse. In addition, specific findings were observed in finger and toe nails of this patient. Nail changes in Kawasaki disease have been previously reported.11 The nail changes in our case were seen in the subacute phase of the disease and might suggest a persistent inflammatory response.

4. Conclusions

We have described a case of coronary artery aneurysms formation after acute treatment for Kawasaki disease with a lack of inflammatory response markers or Kawasaki disease symptoms. When anti-inflammatory drugs, including steroids, are used in acute Kawasaki disease patients, blood laboratory findings and clinical symptoms may be masked, so echocardiography should be utilized appropriately. In high-risk patients, including infants < 6 months of age and those with enlargement in baseline coronary arterial diameters, close echocardiographic surveillance is warranted until coronary arterial diameters stabilize.

Author Contributions

Yumiko Asai wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Takanori Suzuki, and Midori Yamada conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical guidelines for biomedical research on human participants, 2006, India, and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013, and has been approved by the relevant institutional committees.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to contracts with the hospitals providing data to the database.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Burns JC. Kawasaki disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 67: 1738-1149.

- Kobayashi T, Inoue Y, Takeuchi K, Okada Y, et al. Prediction of intravenous immunoglobulin unresponsiveness in patients with Kawasaki disease. Circulation 2006; 113: 2606-2612. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi T, Saji T, Otani T, et al. Efficacy of immunoglobulin plus prednisolone for prevention of coronary artery abnormalities in severe Kawasaki disease (RAISE study): a randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoints trial. Lancet 2012; 379: 1613-1620. [CrossRef]

- Minami T, Hiroyuki S, Takashi T. A case of a boy with Kawasaki disease who developed a coronary artery aneurysm after a low C-reactive protein level in the acute phase of the disease. Prog Med 2003; 23: 1737-1740.

- Yoshino A, Tanaka R, Takano T, Oishi T. Afebrile Kawasaki disease with coronary artery dilatation. Pediatr Int 2017; 59: 375-377. [CrossRef]

- Hamada H, Suzuki H, Onouchi Y, et al. Efficacy of primary treatment with immunoglobulin plus ciclosporin for prevention of coronary artery abnormalities in patients with Kawasaki disease predicted to be at increased risk of non-response to intravenous immunoglobulin (KAICA): a randomised controlled, open-label, blinded-endpoints, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019; 393: 1128-1137. [CrossRef]

- Tremoulet AH, Jain S, Jaggi P, Jimenez-Fernandez S, Pancheri JM, Sun X, et al. Infliximab for intensification of primary therapy for Kawasaki disease: a phase 3 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2014 May;383(9930):1731–8. [CrossRef]

- Kato H, Koike S, Yokoyama T. Kawasaki disease: effect of treatment on coronary artery involvement. Pediatrics. 1979 Feb;63(2):175–9. [CrossRef]

- Genizi J, Miron D, Spiegel R, Fink D, Horowitz Y. Kawasaki disease in very young infants: high prevalence of atypical presentation and coronary arteritis. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2003 Apr;42(3):263–7. [CrossRef]

- 3. Salgado AP, Ashouri N, Berry EK, Sun X, Jain S, Burns JC, et al. High Risk of Coronary Artery Aneurysms in Infants Younger than 6 Months of Age with Kawasaki Disease. J Pediatr. 2017 Jun;185:112-116.e1. [CrossRef]

- 4. Mitsuishi T, Miyata K, Ando A, Sano K, Takanashi J, Hamada H. Characteristic nail lesions in Kawasaki disease: Case series and literature review. The Journal of Dermatology. 2022 Feb;49(2):232–8.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).