Submitted:

17 April 2023

Posted:

17 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Motivation and Contribution

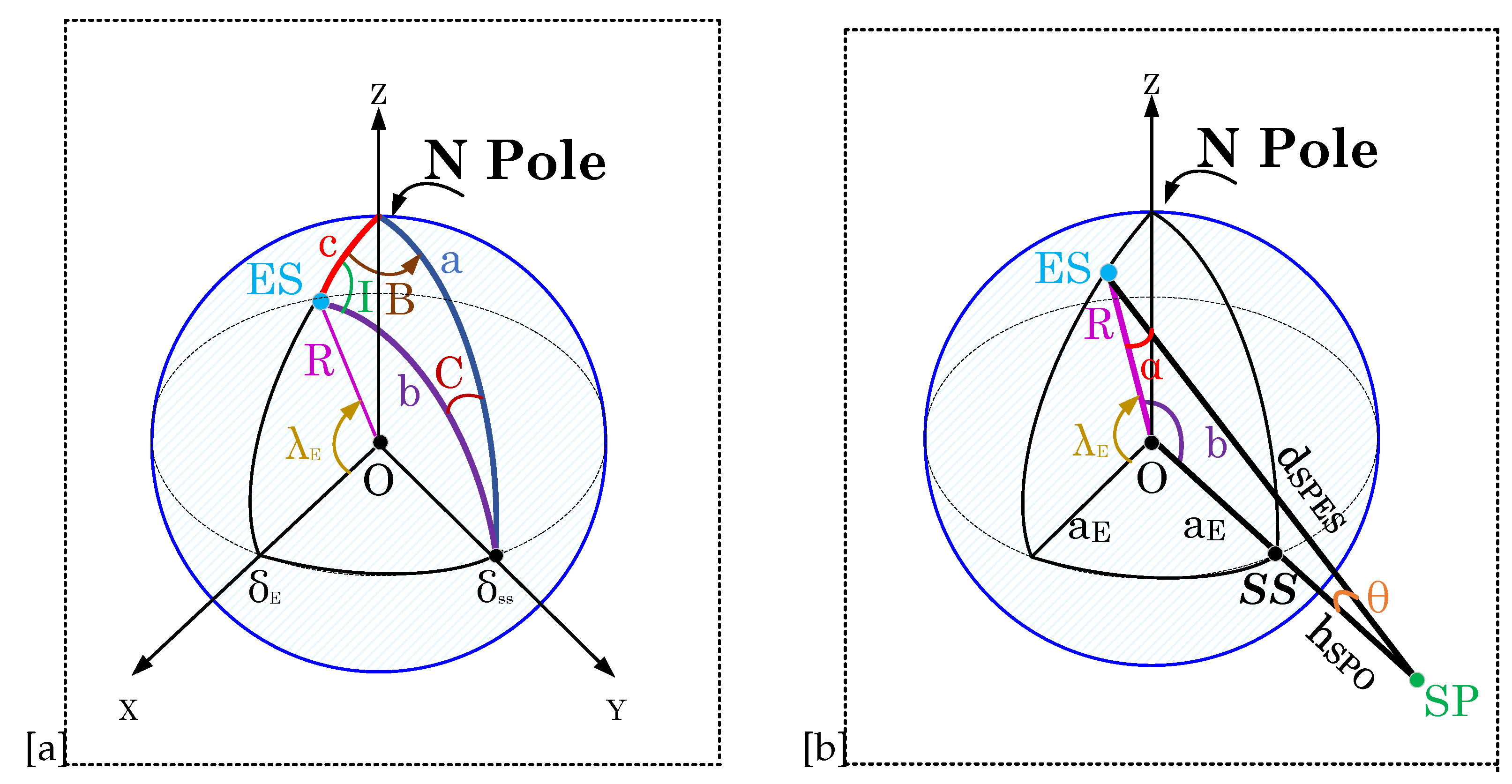

3. Satellite Geometries

3.1. Uplink satellite Geometry for DoA Estimation.

3.2. Downlink satellite geometry for DoA Estimation

4. Signal Models

4.1. Uplink Signal Model for different satellite systems

4.2. Downlink Signal Model for satellites

4.2.1. Spatial Correlation Model for downlink situation in different satellite systems

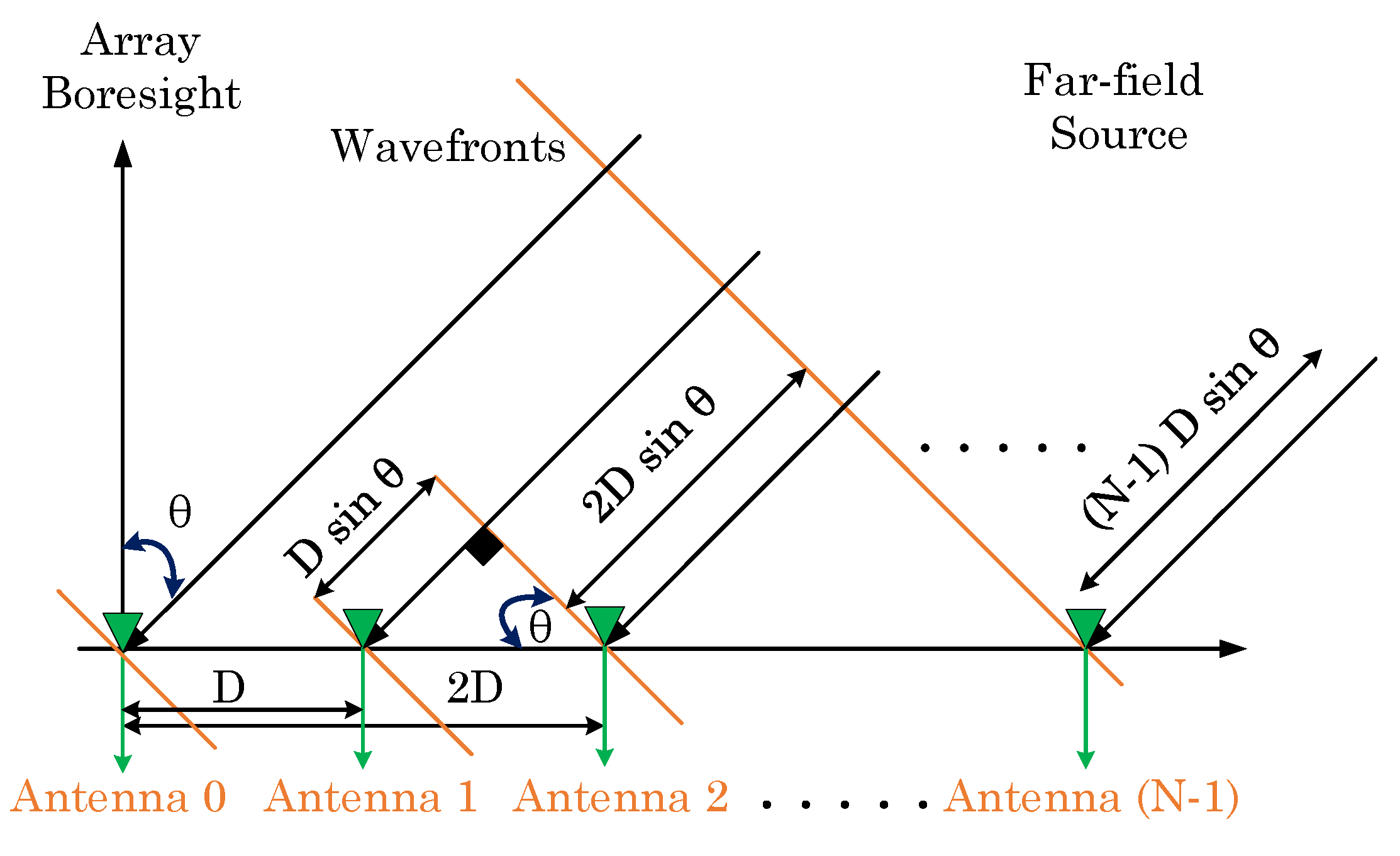

5. DoA Estimation Techniques

5.1. Delay and Sum (DAS) Technique

5.2. Multiple Signal Classification (MUSIC) Algorithm

6. Cramer-Rao Lower Bound (CRLB)

7. Analysis and Discussion using numerical methods

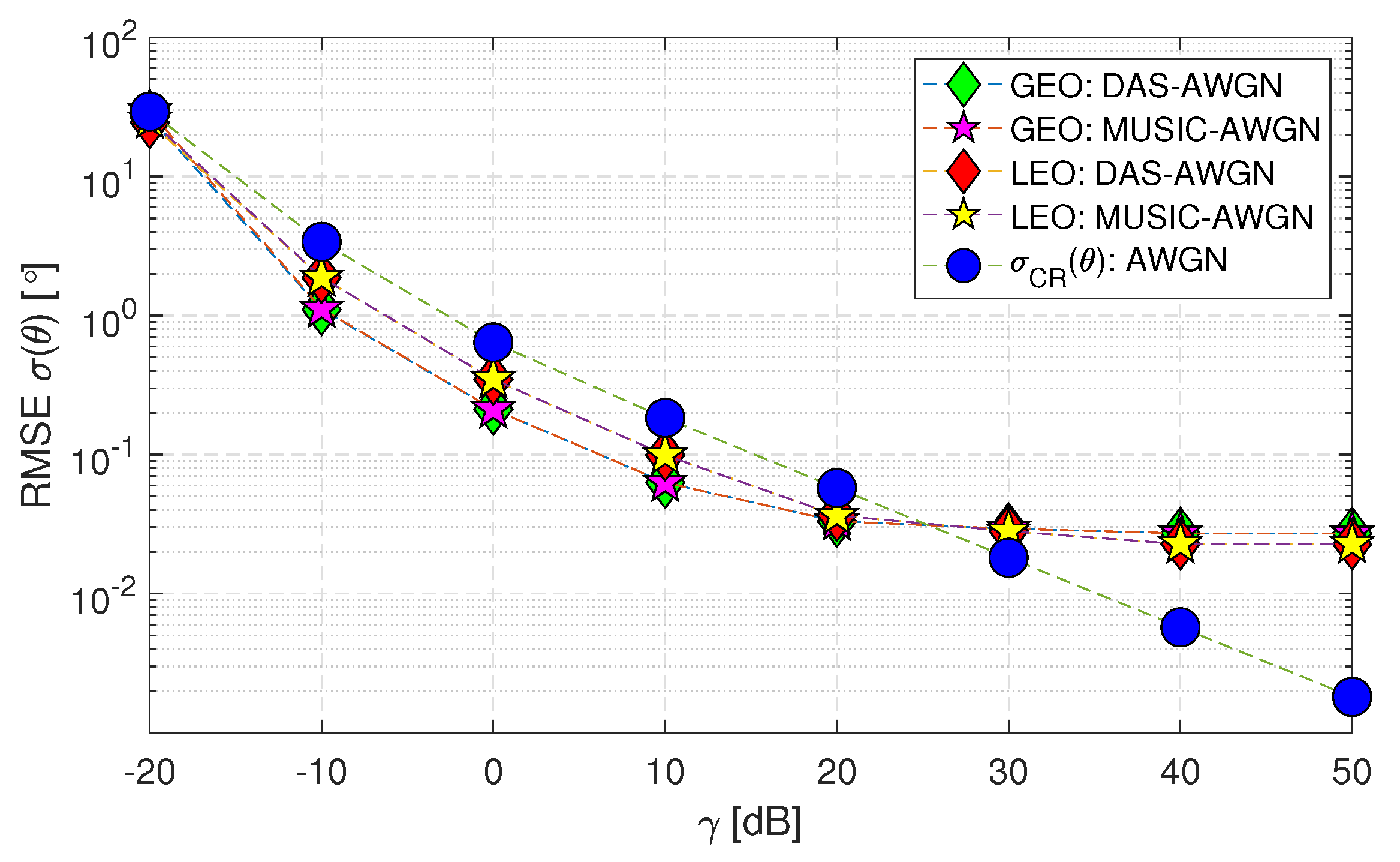

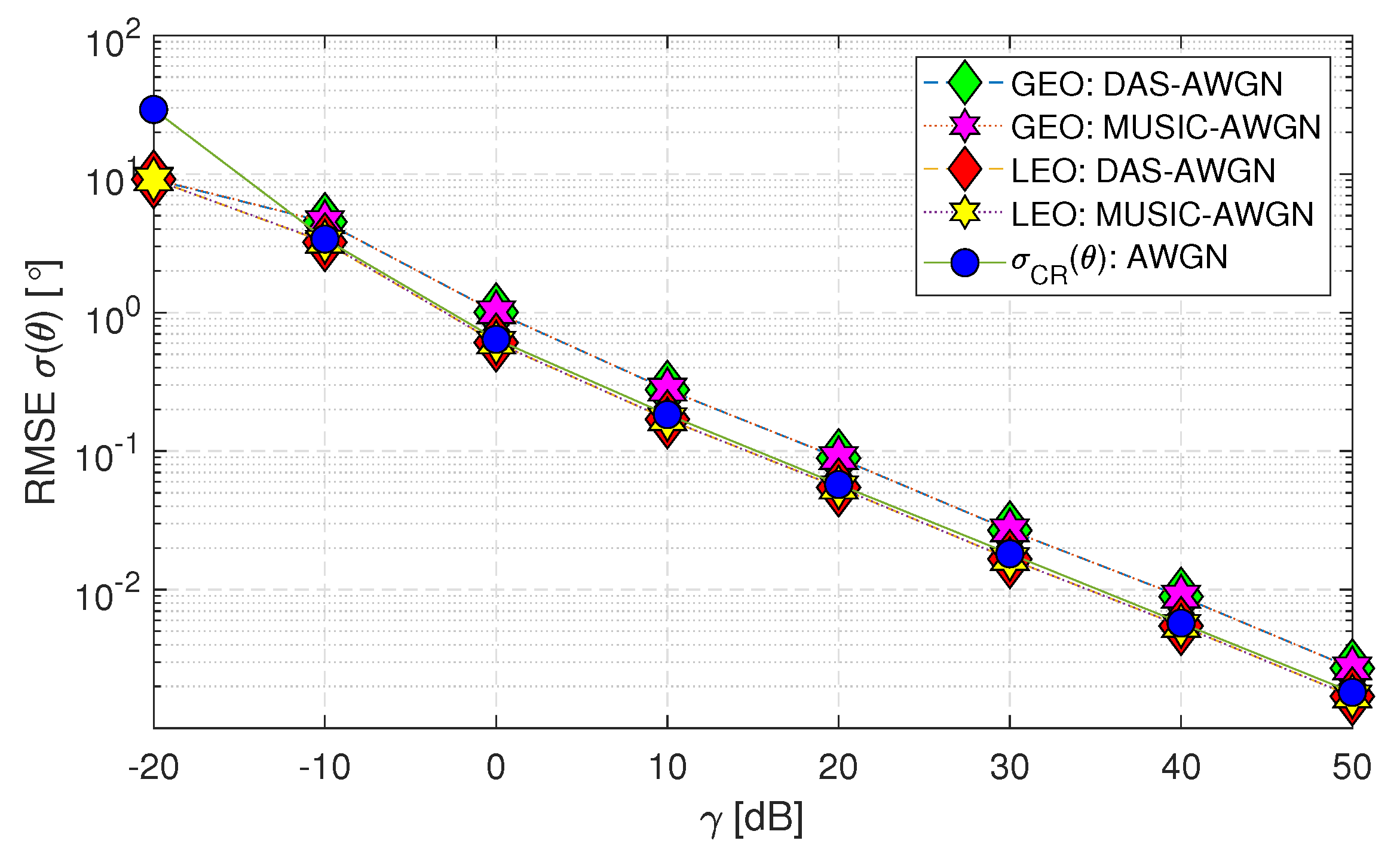

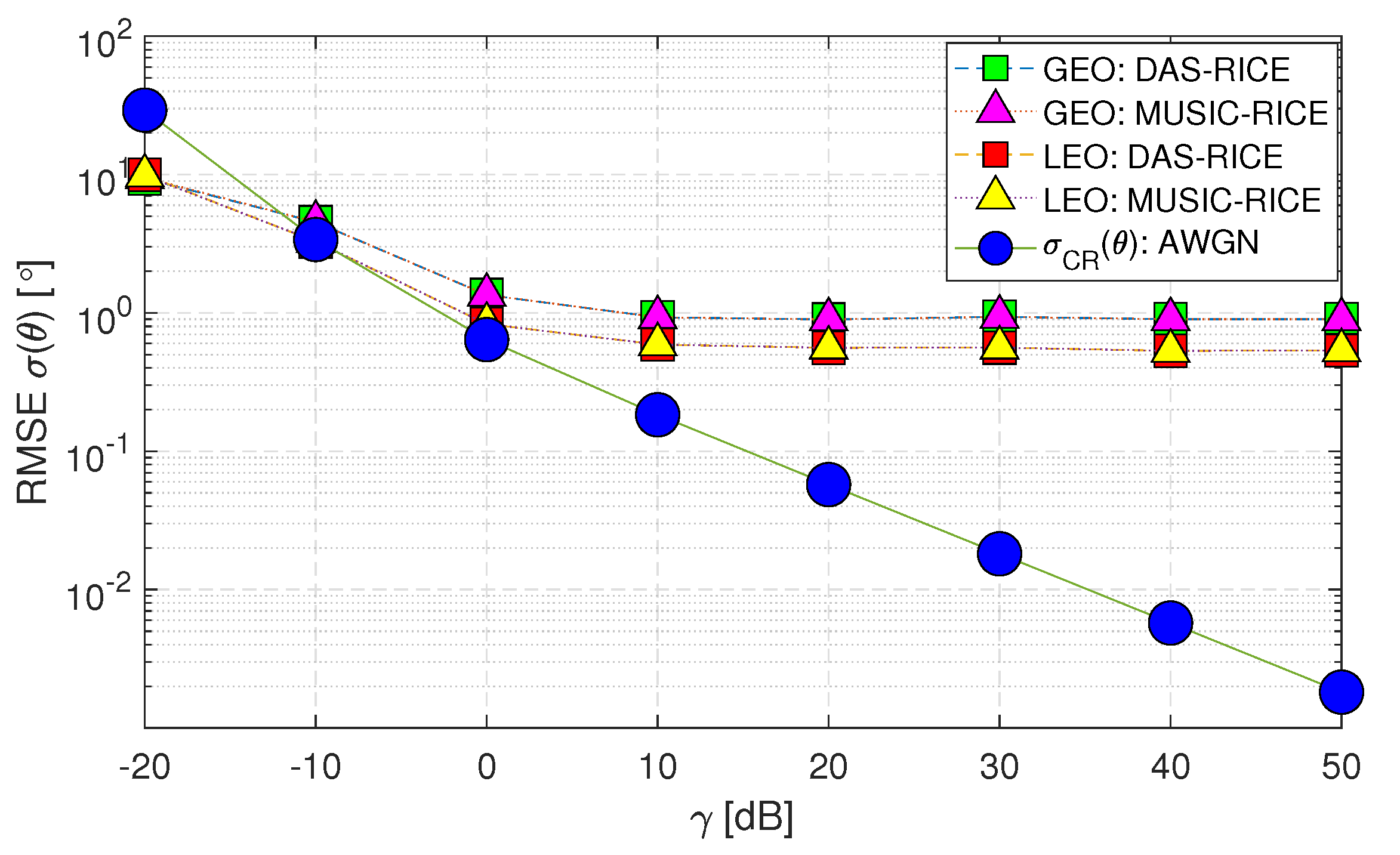

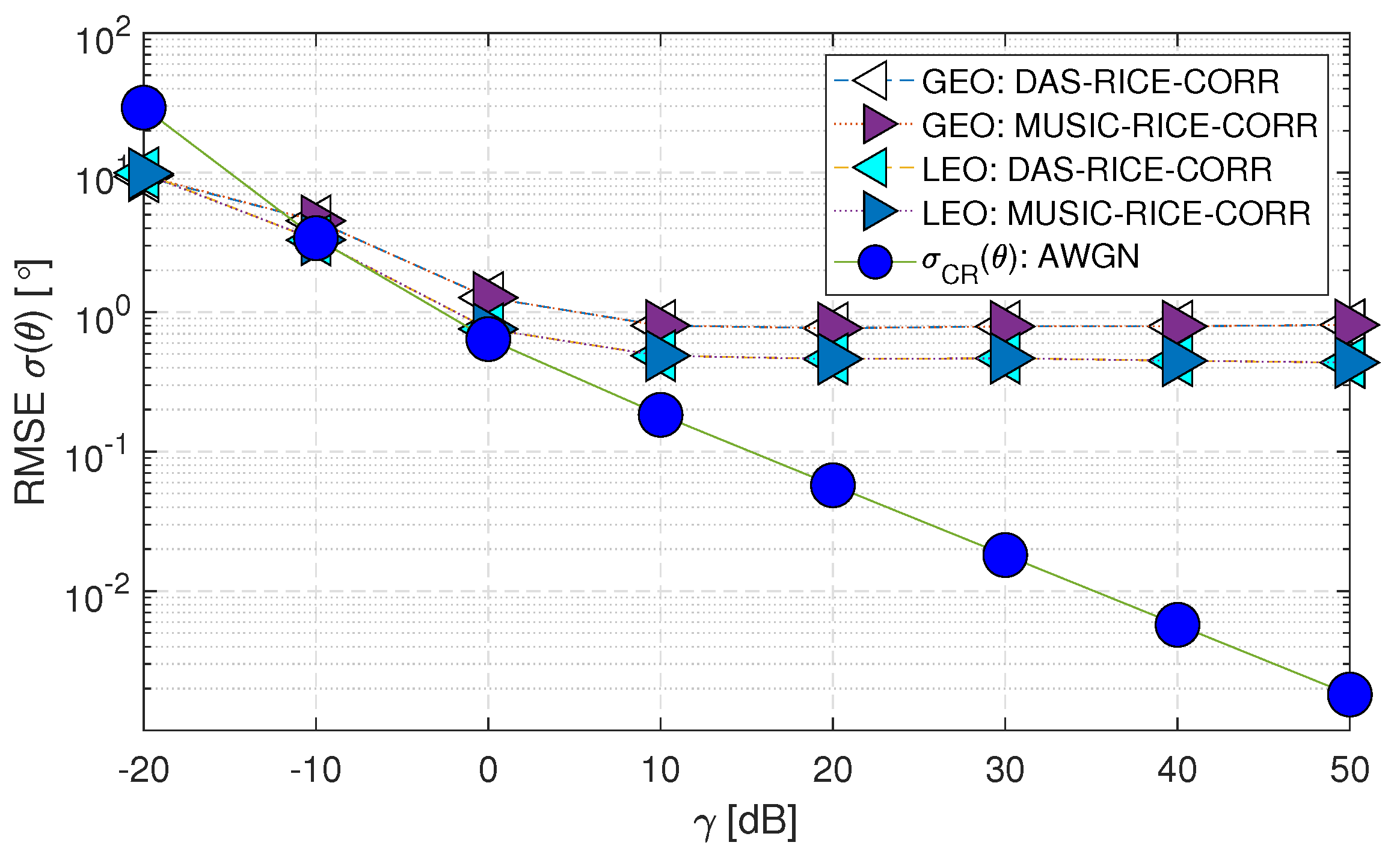

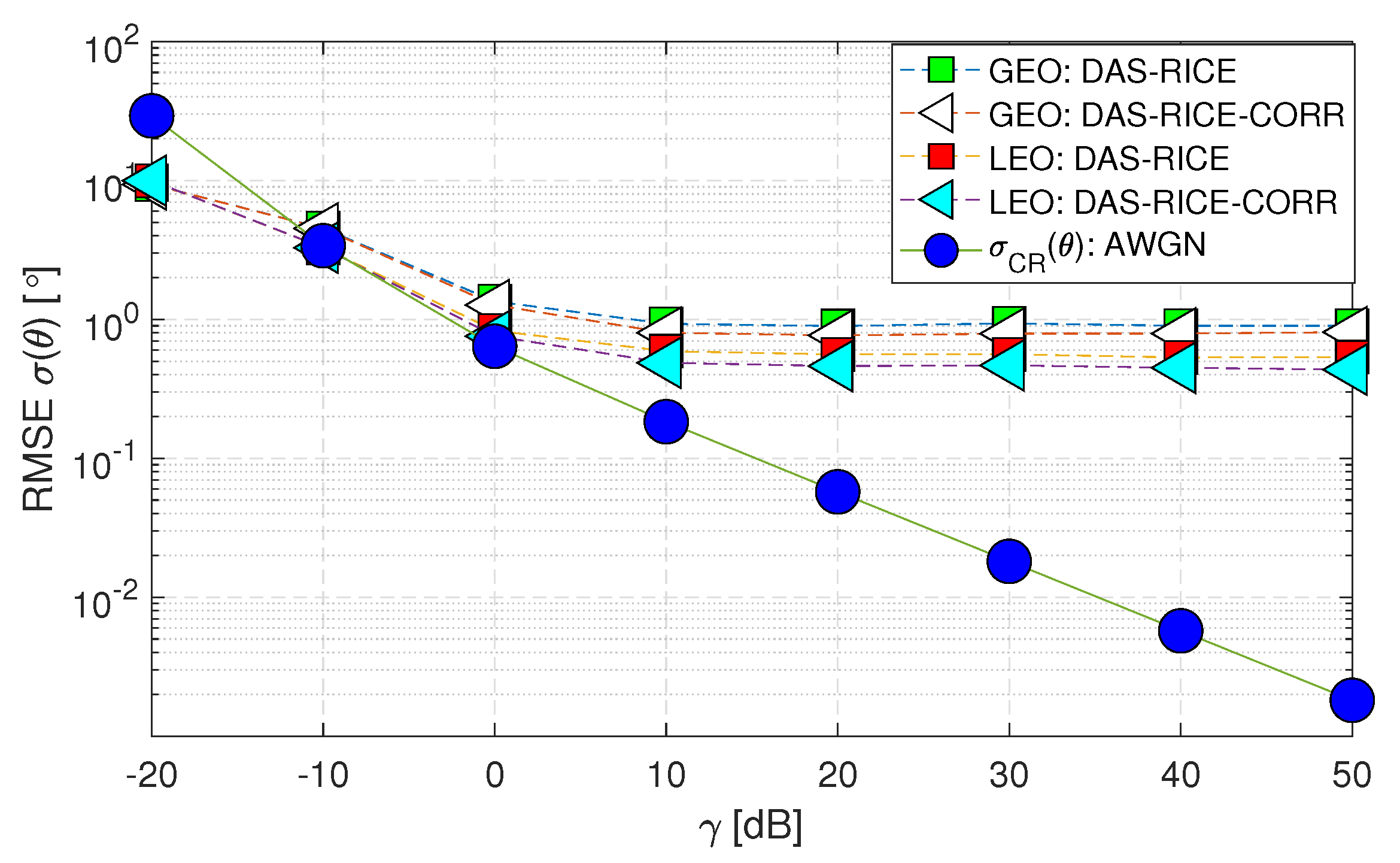

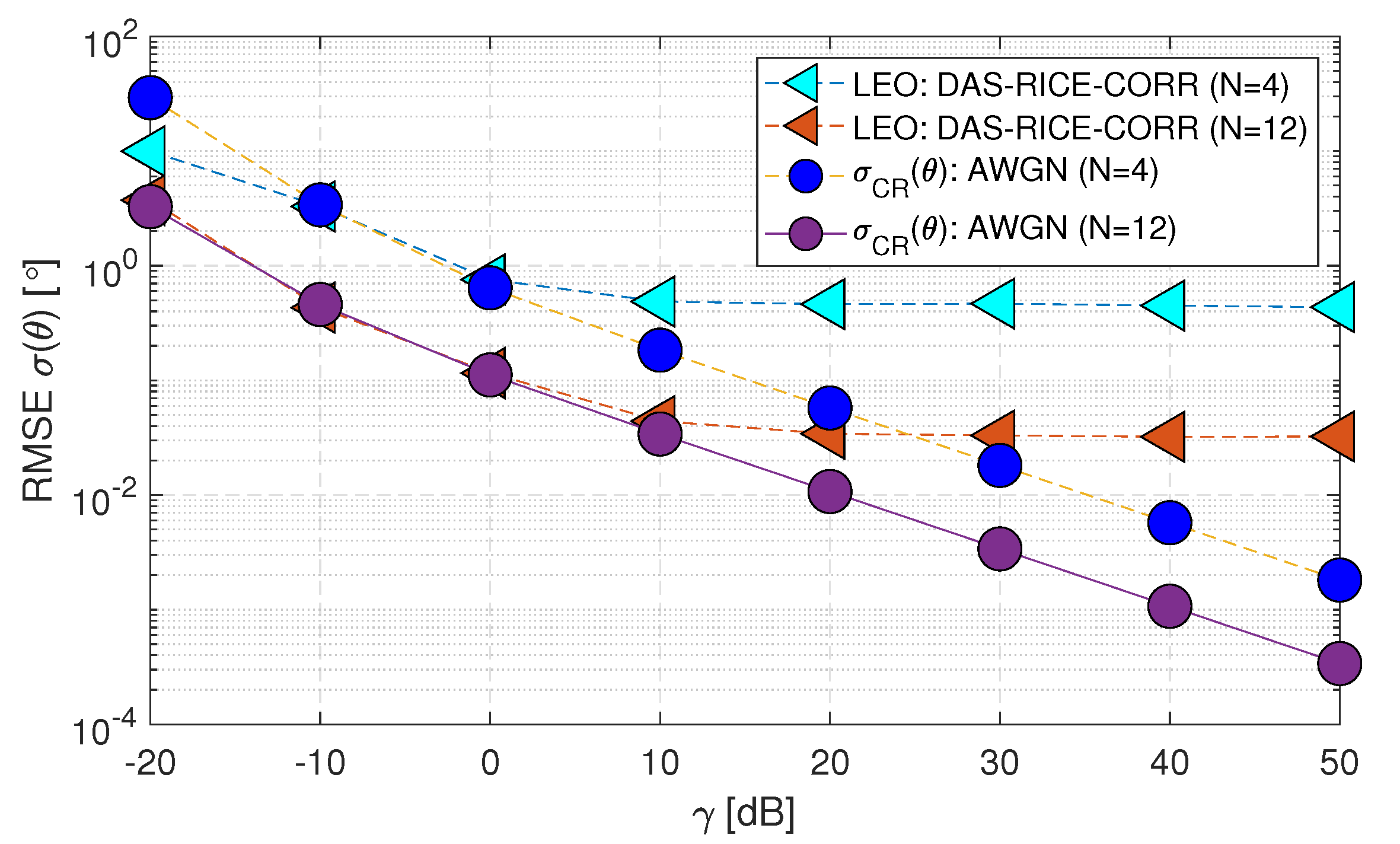

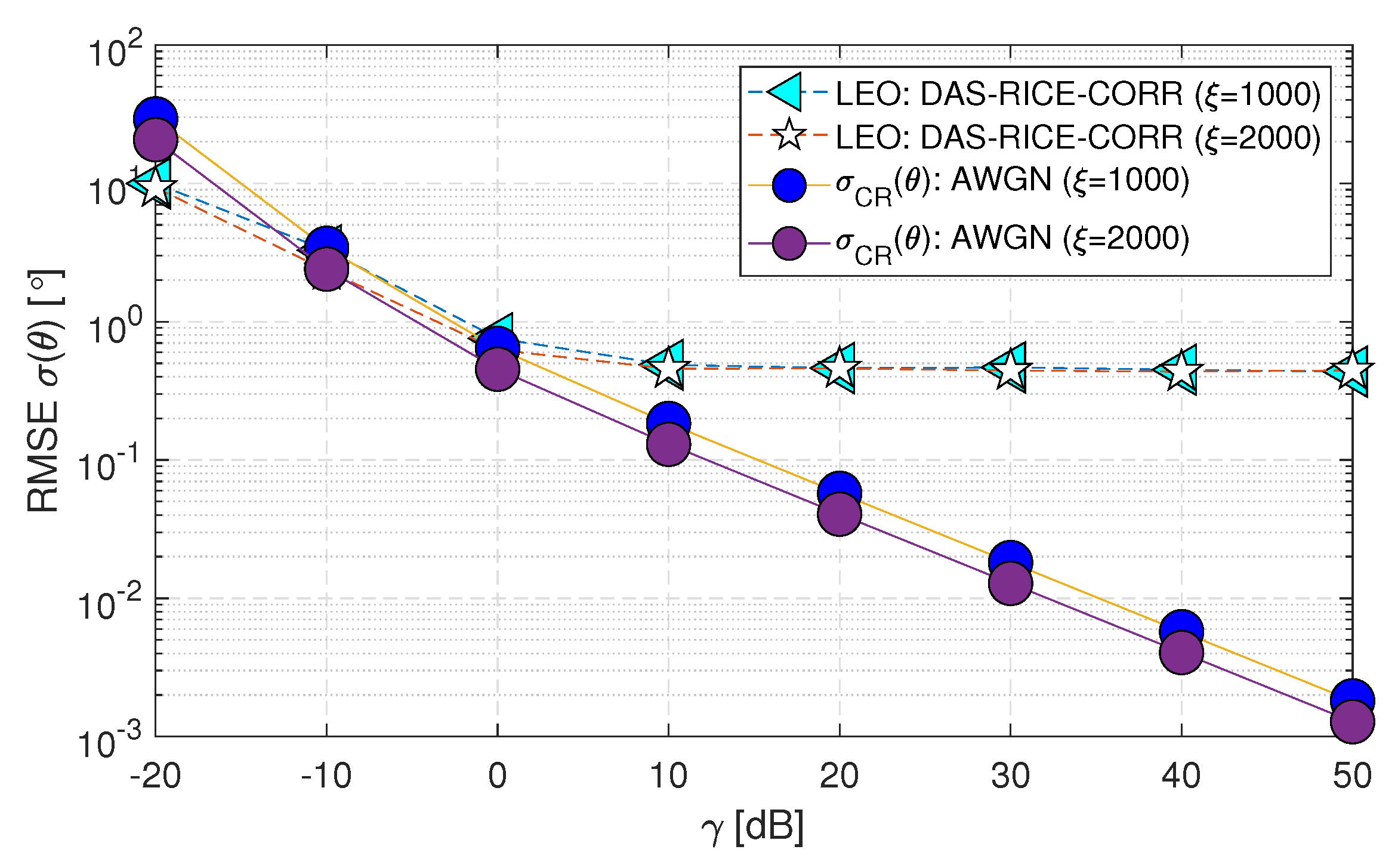

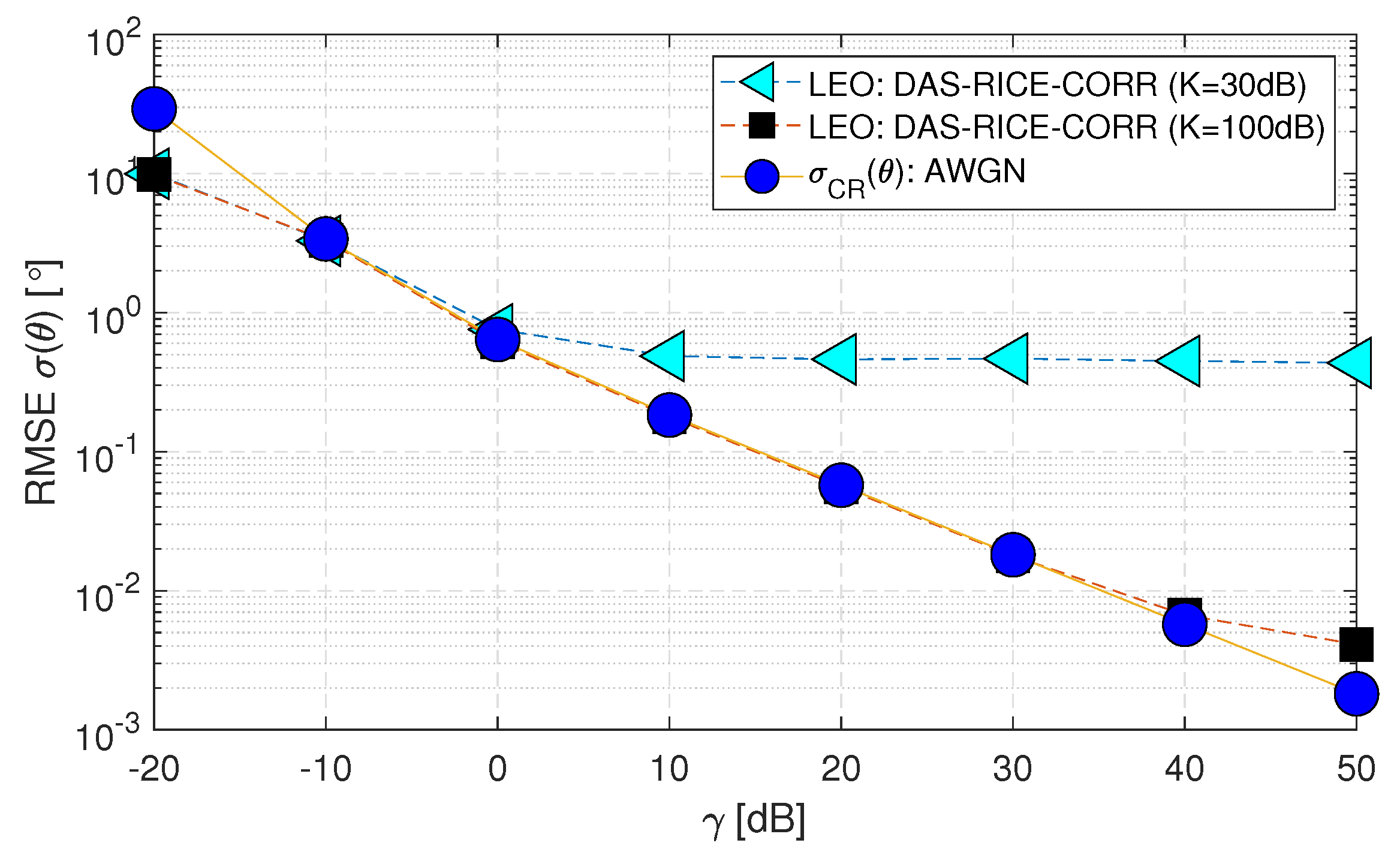

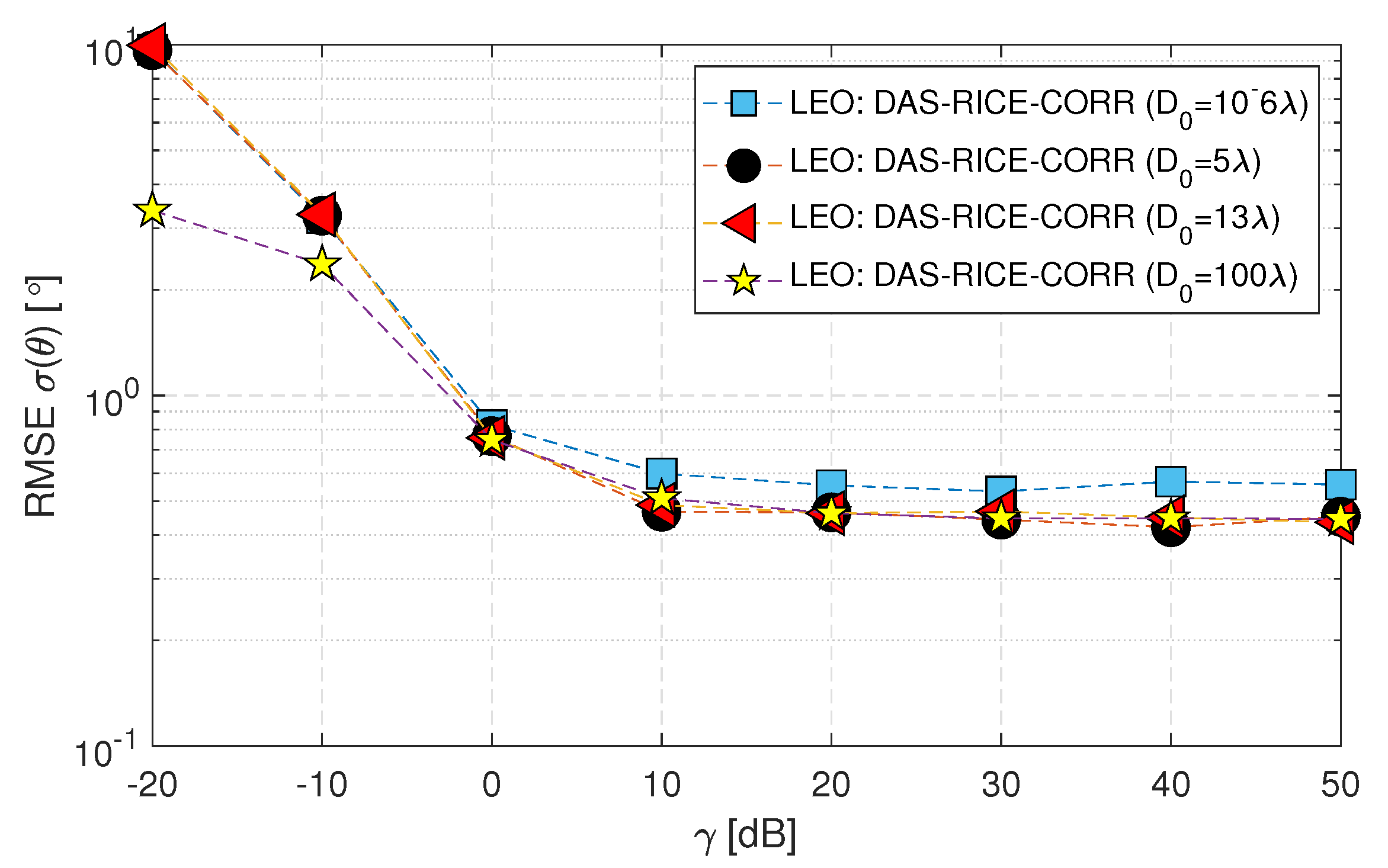

7.1. Performance Evaluation of DoA Estimation Techniques in Diverse Scenarios

- The DAS and MUSIC methods are considered optimal when assuming AWGN (i.e., Matched Filtering provides the best results for a predefined noise distribution).

- The RMSE performance of both DAS and MUSIC methods for the LEO satellite matches the within the range of (-10 to 50) [dB]. However, for the GEO satellite, the performance is close to .

- When the range of decreases below -10 [dB], the DAS and MUSIC curves deviate beyond the Cramer-Rao Lower Bound () for both GEO and LEO satellites. This deviation occurs because the estimation of the channel-phase random variable is limited to a range of . Consequently, the standard deviation of the analysis is constrained to this range and remains constant when the value drops to -20 [dB]. In contrast, the applies to all values and can take any real numbers.

8. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xie, W.; Wen, F.; Liu, J.; Wan, Q. Source association, doa, and fading coefficients estimation for multipath signals. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2017, 65, 2773–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roddy, D. Satellite communications. McGraw-Hill Education, 2006. CrossRef.

- Cakaj, S.; Kamo, B.; Kolic¸i, V.; Shurdi, O. The range and horizon plane simulation for ground stations of low earth orbiting (LEO) satellites. Int. J. Commun. Netw. Syst. Sci. 2011, 4, 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad Hashim, I. S.; Al-Hourani, A. Satellite-based localization of iot devices using joint doppler and angle-of-arrival estimation, 2022. CrossRef.

- Gentilho, E.; Scalassara, P. R.; Abrao, T. Direction-of-arrival estimation methods: A performance-complexity tradeoff perspective. Journal of Signal Processing Systems 2020, 92, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; He, F.; Jin, J.; Xiong, H.; Xu, G. Doa estimation for attitude determination on communication satellites. Chinese Journal of Aeronautics 2014, 27, 670–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartzell, S.; Burchett, L.; Martin, R.; Taylor, C.; Terzuoli, A. Geolocation of fast-moving objects from satellite-based angle-of-arrival measurements. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2015, 8, 3396–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D.; Zhang, Q.; Cui, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, X.; Liu, J. Orbit determination algorithm and performance analysis of high-orbit spacecraft based on gnss. IET Communications 2019, 13, 3377–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Ni, W.; Su, T.; Liu, R. P.; Guo, Y. J. Fast and accurate estimation of angle-of-arrival for satellite-borne wideband communication system. IEEE Journal on selected areas in communications 2018, 36, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzi, Y.; Kashani, E. S.; Ajorloo, A. Angle of arrival-based target localisation with low earth orbit satellite observer. IET Radar, Sonar & Navigation 2016, 10, 1186–1190. [Google Scholar]

- Crisan, A. M.; Martian, A.; Cacoveanu, R.; Coltuc, D. Angle-of-arrival estimation in formation flying satellites: Concept and demonstration. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 114116–114130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Yao, Z.; Cui, X.; Lu, M. Angle-of-arrival assisted gnss collaborative positioning. Sensors 2016, 16, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viswanathan, M. Wireless Communication Systems in Matlab. Independent, 2020. CrossRef.

- Hasib, M.; Kandeepan, S.; Rowe, W. S. T.; Al-Hourani, A. Direction of arrival (DoA) Estimation Performance in a Multipath Environment with Envelope Fading and Spatial Correlation. In 13th International Conference on ICT Convergence (ICTC); October, 2022.

- Van Trees, H. L. Optimum array processing: Part IV of detection, estimation, and modulation theory. John Wiley and Sons, 2004.

- Kandeepan, S.; Evans, R. J. Bias-free phase tracking with linear and nonlinear systems. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2010, 9, 3779–3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, A. S.; Phan, K. T.; Hong, Y. Spatially correlated mimo-otfs for leo satellite communication systems. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on Communications Workshops (ICC Workshops); IEEE, 2022; pp. 723–728.

- Shiu, D.-S.; Foschini, G. J.; Gans, M. J.; Kahn, J. M. Fading correlation and its effect on the capacity of multielement antenna systems. IEEE Transactions on Communications 2000, 48, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; et al. Spatial correlation characteristics analysis of multibeam channels of mobile satellite system. International Journal of Communications, Network and System Sciences 2017, 10, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasawa, Y.; Iwai, H. Formulation of spatial correlation statistics in nakagami-rice fading environments. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2000, 48, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arapoglou, P.-D.; Liolis, K.; Bertinelli, M.; Panagopoulos, A.; Cottis, P.; De Gaudenzi, R. MIMO over satellite: A review. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2010, 13, 27–51. [Google Scholar]

- Soler, T.; Eisemann, D. W. Determination of look angles to geostationary communication satellites. Journal of Surveying Engineering 1994, 120, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, F.; Andro, M. The effect of Doppler frequency shift, frequency offset of the local oscillators, and phase noise on the performance of coherent OFDM receivers. Technical Report, 2001.

- Yu, K.; Ottersten, B. Models for MIMO propagation channels: A review. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing 2002, 2, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foutz, J.; Spanias, A.; Banavar, M. K. Narrowband direction of arrival estimation for antenna arrays. Synthesis Lectures on Antennas 2008, 3, 1–76. [Google Scholar]

| Symbol | Parameter | Units |

| Frequency | 28 [GHz] | |

| Speed of light | 3 [m/s] | |

| N | Antenna values | 4 |

| Signal-to-noise-ratio | (-20 to 50) [dB] | |

| Number of Samples | 1000 | |

| K | Rice factor Value | 30 [dB] |

| De-correlation Distance | 13 at BS | |

| Latitude of Earth Station (Uplink) | - | |

| Longitude of Earth Station (Uplink) | - | |

| Elevation angle of satellites (Uplink) | 10 | |

| Altitude of satellites (Uplink) | 35,786 (GEO) and 1500 (LEO) in [km] | |

| Velocity of satellites | 0 (GEO) and 7.11 (LEO) [km/s] | |

| Velocity Vector’s angle of satellites | 0 (GEO) and 0 (LEO) in | |

| Doppler Shift of satellites | 0 and 663.600 in [kHz] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).