1. Introduction

Medical entities exchange wide numbers of various data between different systems. The interoperability is generally guaranteed inside of the same medical entities but in fact, interoperability problems between medical entities are regularly observed. These incompatibility problems result in multiple repeat examinations for the same patient, an overload of healthcare facilities, and costs related to the examinations that had to be repeated.

On the other hand, the increase in the world population leads inexorably to a progressive saturation of healthcare capacities. It has become crucial to increase the availability of these structures and their operating costs by avoiding unnecessary examinations. At the same time, the development of telemedicine means that patients no longer need to be systematically transferred to healthcare facilities. For savings and efficiency improvements to be made, improvements must be made to the interoperability of systems and data exchange standards to make them efficient.

The comparison and study of system interoperability standards and data standards is a prerequisite for understanding the sticking points and proposing solutions.

Our goal is to emerge insights to build our data interoperability proposal and address issues of actual interoperability models.

Our contributions to this paper are:

The summary of main data standards used in medical context

The study of the different interoperability models highlights these model’s pros and cons.

The highlight of required features of a medical interoperability reference model

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: In section 2, we explain the principal data standards used to characterize medical data. Each standard is described, and its field of application is given. Afterward, in section 3, we highlight standards implemented to ensure the interoperability of medical data identified in the previous section. In section 4, we propose a state-of-the-art focusing on the implementation of the standards identified in section 3. Then, we propose, in section 5, a comparative study of data interoperability models in the medical context. Afterward, We discuss and highlight features of the ideal interoperability model and draw limits of our work, in section 6. Finally, we conclude our work with lessons learned from our analysis and we consider the perspectives of our work.

2. Main health system interoperability standards

In this section, we present the main interoperability standards: HL7 and its derived, FHIR, DICOM, and JSON. Each standard is analyzed and its main features are emphasized. At the end of this section, a table summarizes whole these features.

2.1. Health Level Seven (HL7) Standards

The HL7 format is used to exchange health data electronically between the IT systems of different organizations. It allows the transmission of data such as prescriptions, test results, electronic medical records, etc.

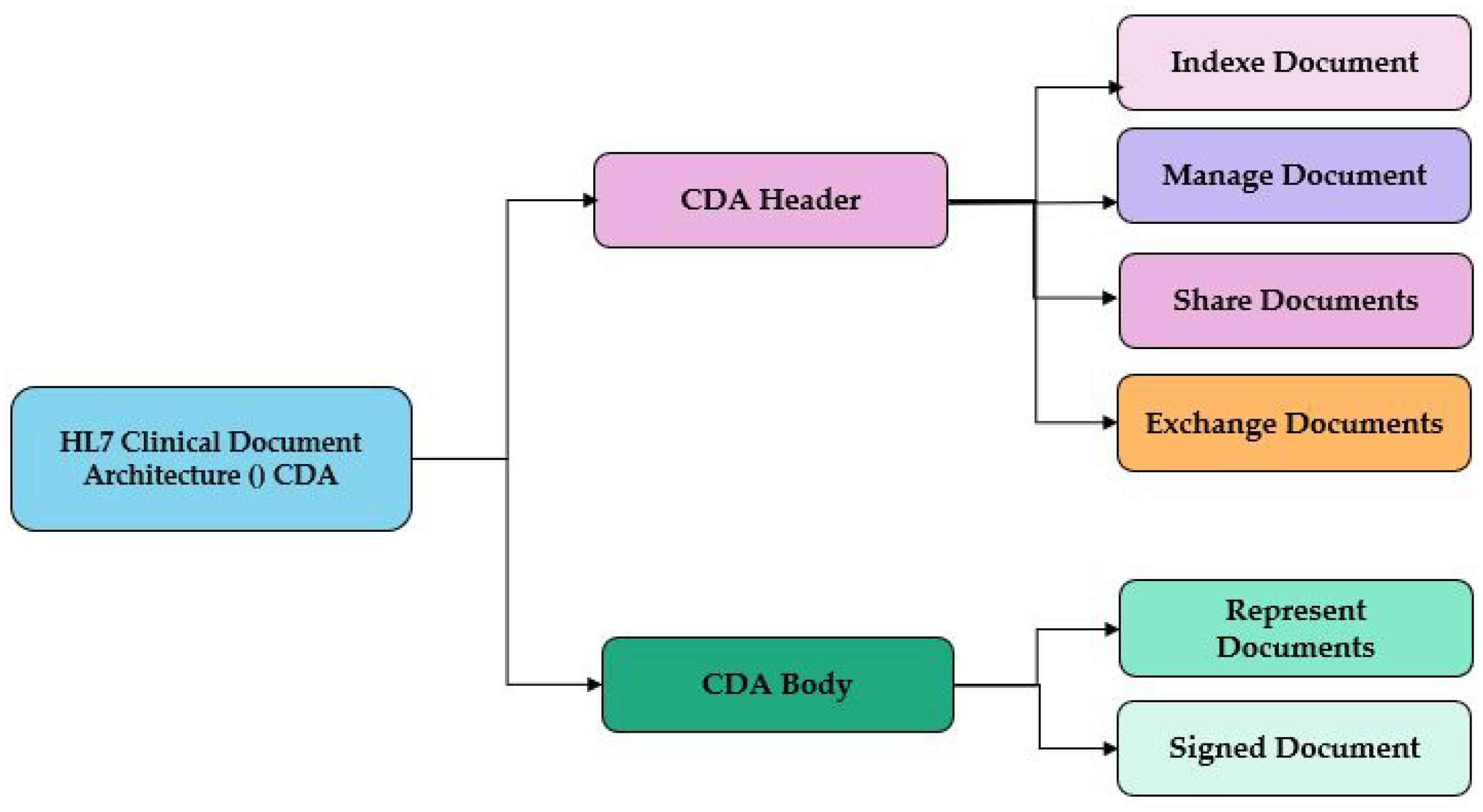

2.2. HL7 Clinical Document Architecture (CDA)

This standard developed by HL7. is a markup standard based on XML and HL7 RIM (V3), it is used to represent and facilitate the exchange and share of electronic medical records and clinical documents. It allows health data to be stored in a structured format that can be read and interpreted by computer systems, as summarized in

Figure 1.

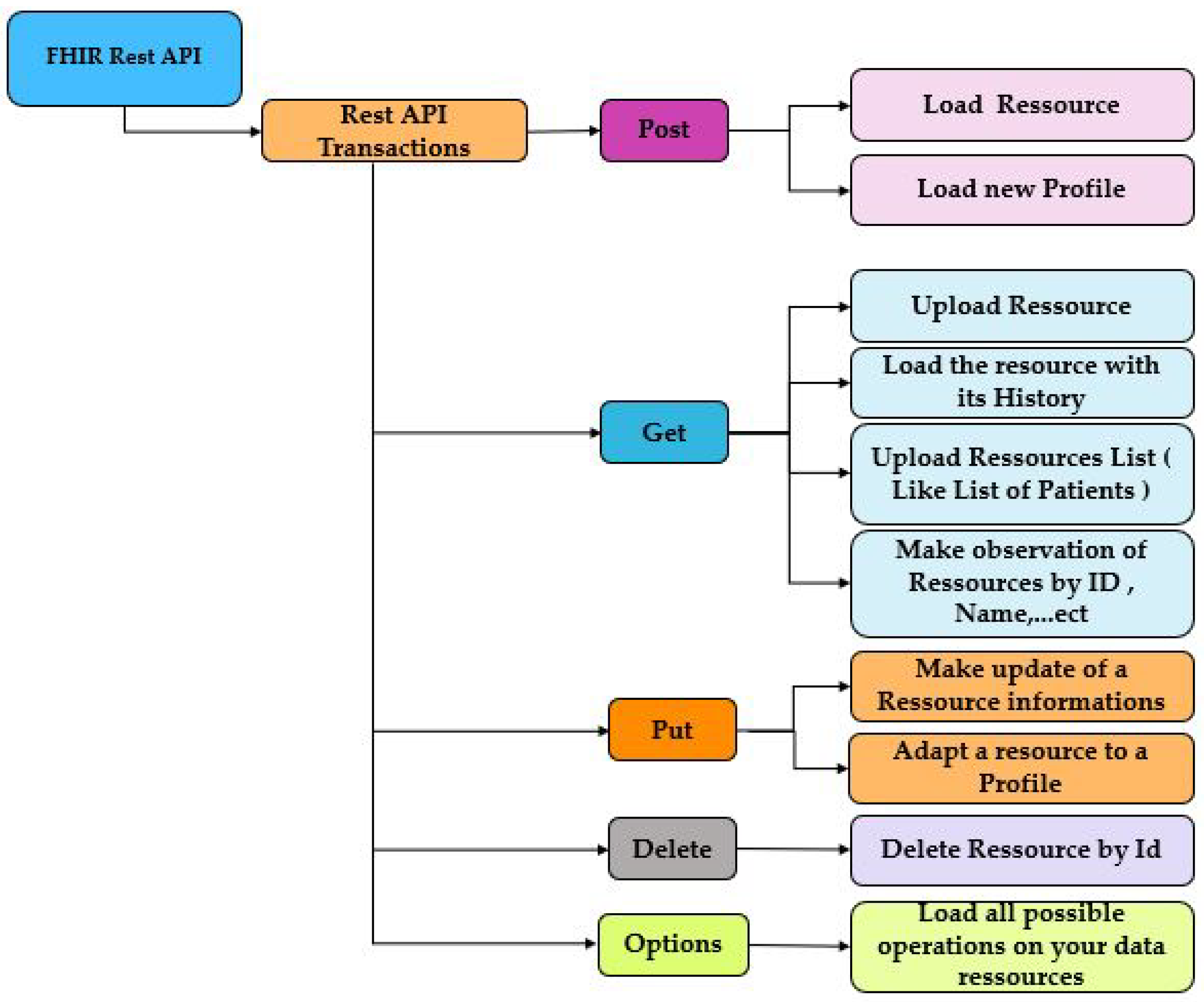

2.3. Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources Standard (FHIR)

FHIR is a standard developed by HL7 (Health Level Seven) International which is a non-profit organization, this standard allows the exchange of medical data in JSON format in the form of different forms and elements called resources. These can be manipulated using an API Rest, something that helps the implementation of this standard easily and network different health systems medical entities to share and exchange health data between them in real-time. Using the Rest API for example “INSOMNIA”, we can either create a new resource or a list of FHIR resources in JSON or XML format using the POST method which will subsequently generate an ID for each resource, and then we can search for them from the Rest server, this time with the GET method, specifying in the search criteria in the URL the type of the "Patient" example resource, and with the same transaction we can make the observation of resources loaded into the Rest server either by ID, name, etc. We can also modify, for example, the information of a patient using the PUT transaction, passing through the "observation" value for the element "

ResourceType" and we specify for example the type of the resource in which we work example, Patient, in the URL in front of the PUT transaction of our resource, and we can return to the GET transactions to display if you want all the history of I The resource you created includes all the versions in which we have made changes. The additional advantage of using the FHIR standard is that we can adapt the list of resources that we have already loaded in the Rest API or that we will create them using the Profile resource, then we can just create a profile with the same type as the group of resources that we have already put in an FHIR server, example "

Hapi FHIR" which will generate a URL of the profile, specifying the structure that will be required for each resource, well said the elements that must exist in each as well as a set of constraints that must be supported in the form of cardinality of each element, and to apply it to a resource, simply copy the URL that corresponds to the profile that we created, we go back to the Rest API and paste it in the URL element without forgetting to modify the value of the "

resourcetype" element to "

structuredefinition" as the value all using the transactions post, we will conclude by following that our resource is well adapted to the new structure that we have already specified in profile FHIR all its in order to unify the structure of all the resources of the same type, and of course, we can with the same Rest API visualize all the possible operations on resources using the “options” transaction, as summarized in

Figure 2.

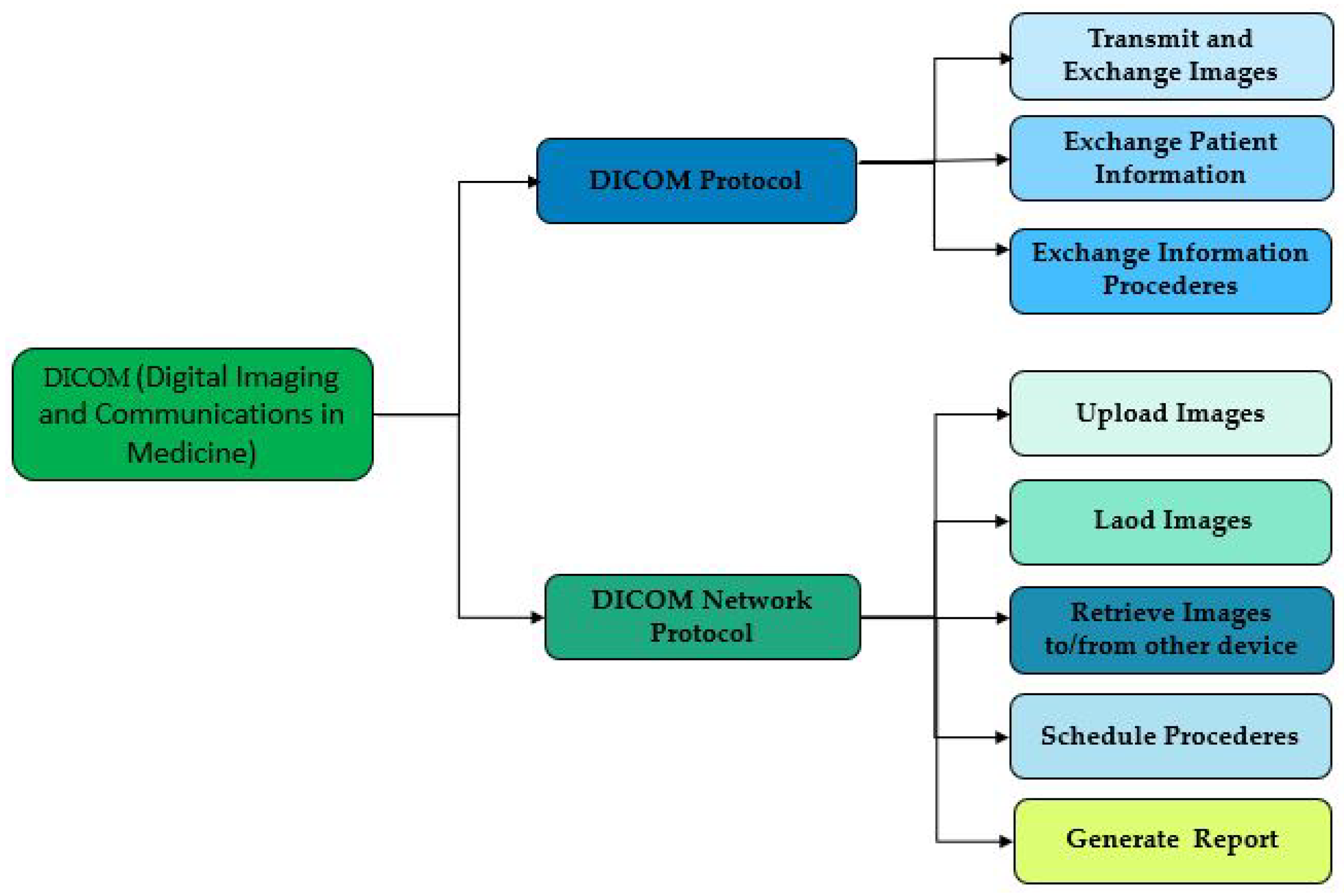

2.4. Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM)

DICOM is a standard developed by National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA). This standard is used to store, transmit and display digital medical images, such as x-rays, MRIs, and ultrasound images. It is subdivided into two main components the file format which is used to transmit and exchange images, and the DICOM network protocol which allows digital medical images to be displayed and stored in IOD formats, such as X-rays, MRIs, and ultrasound images, these two elements work together so that the images are in a standard format and the exchange of images is also standardized.

Figure 3 shows that it is with the help of a DICOM server for example "MiPacs Storage Server" which is an electronic database for data related to medical and dental imaging. While using the standard DICOM v3.0 protocol, we can store and manage a large amount of data as well as provide ways to access transferred images and exchange data in relation to patients as well as procedures. This makes DICOM NETWORK Protocol allows to program of these procedures, as well as generating reports and retrieving images for and from objects and information systems. The DICOM v3.0 standard provides a means to communicate with various DICOM v3.0 compatible devices, including scanners and workstations. MiPACS Storage Server functions primarily as a DICOM provider, but other stations are also capable of exchanging DICOM files/images with it. The communication protocol employed employs TCP/IP as the transport layer, as demonstrated in

Figure 3.

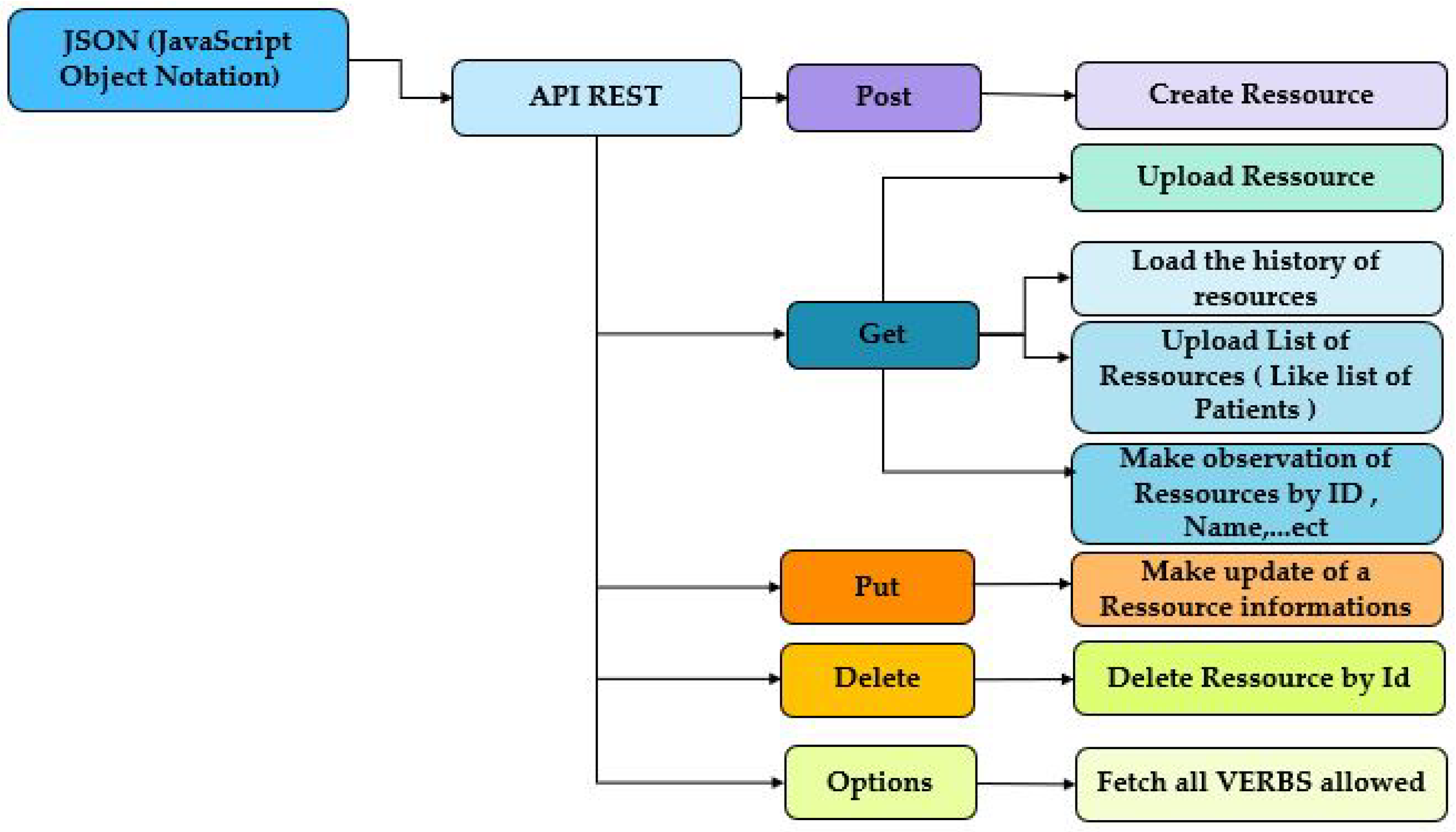

2.5. JavaScript Object Notation (JSON)

JSON is used to store and transmit health data in a structured data format. It is often used for data transmission via APIs. So you can take advantage of a Rest API to manipulate health data, so you can add a resource and load it into the server using the POST transaction, put changes on the resource with the PUT transaction and delete with the DELETE transaction and even retrieve the list of resource histories or observe the list of all resources by using the POST transaction, but neither the types of resources nor their structures nor defined by the REST standard, as summarized in the

Figure 4.

3. Data interoperability standards

In this section, we present a comparative study of the data interoperability standards studied in the previous section in tabular format. In order to compare these different standards, we have based on the following criteria; the first one is the organization criteria that have developed the standard, the second one is the name of standard or it’s version, then the description of the essential task that will be guaranteed by the standard and finally type of data supported that means the of data generated after the implementation of this model.

Table 1.

Main data interoperability standards used in the medical field.

Table 1.

Main data interoperability standards used in the medical field.

| Organization |

Standard |

Description |

Type of data supported |

| HL71

|

HL7 V2.8 |

Exchange health data electronically between the IT systems |

Electronic data |

| HL7 V3 (RIM2) 2.36 |

Specifications based on HL7’s RIM |

Create reusable clinical data standards |

| HL7 CDA3

|

Stored health data in a structured format |

Manage EHR12 and clinical documents |

| HL7 FHIR4 (R4) |

Specification for online health data exchange. |

Medical data in JSON6 or XML10 format |

| NEMA11

|

DICOM5

|

This format is used to store, transmit and display images |

Digital Medical Imaging |

| Douglas Crockford, in 2002 |

JSON6

|

Store and transmit health data in structured data format |

Bills & Medical Reports |

| FCAT8

|

TA7

|

Anatomy terms in English and Latin |

Text |

| ISO9

|

21090:2011 |

Harmonized data types for information exchange |

Text |

| 13606 |

High-level description of clinical information |

JSON6

|

| DIEEE 11073 |

Personal Health data standards |

HL71 format |

| ISO 23903 |

Representation of concepts on a semantic level |

ICT-supported systems, EHDS13

|

We summarize after this synthetic study that the HL7 Version 2 (V2) standard is used to exchange health data electronically between the computer systems of different organizations. It allows the transmission of data such as prescriptions, test results, and electronic medical records. While DICOM presents a format for exchanging, storing, transmitting, and displaying digital medical files and images in DICOM format, such as x-rays, MRIs, and ultrasound images. The CDA format is used to represent electronic medical records and clinical, It allows health data to be stored in a structured format that can be read and interpreted by computer systems documents While HL7 Version 3 (V3) RIM for Reference Information Model makes it possible to define a suite of specifications based on HL7 aims to create a reusable clinical data standard but this standard is difficult to implement, which has led to the proposal of a new standard called First Healthcare interoperability Resources (FHIR) based on HL7 version 3 RIM with a proposal of data structures for each resource (Patient, Practitioner, person, group, Observation, Medication, etc.) This format is a specification for online health data exchange. It allows the networking of different health systems to share health data between them in JSON or XML format. On the other side, it is easy to set up something that does not have been present in the JSON standard.

4. State of the art

In this paragraph, we present the implementation of the standards mentioned in the previous section within different architectures.

In 2019, Mavrogiorgou et al [

1], have developed a platform that initially addresses the collection of data that comes from different heterogeneous IoMTs devices to serve different application scenarios and deliver their data at different frequencies between them using the technologies 5G, in this article the authors proposed an approach divided into several stages; Data Acquisition this part is responsible for the collection of all the specifications, APIs, the network specifications in order to recover their data, Devices Information Collection, which makes it possible to identify the specifications of the connected object, step of Specifications Similarity which makes it possible to identify syntactical similarities between detected objects, Specifications Classification this part aims to classify specifications is to classify the specifications of each unknown device based on the K-Nearest Neighbors (

KNN) algorithm[

2], in order to group all unknown connected devices with existing known devices according to their specifications, PIs Mapping & Data Collection this part allows you to specify the device types detected and their API methods. The Slicing Management component utilizes the collected data to facilitate further analysis of the slicing management mechanism, as per the network specifications of the connected devices. The proposed mechanism is based on the 5G Network Slicing concept, which enables 5G Core (

5GC) operators to allocate specific parts of their networks to support various medical scenarios. The Data Interoperability aspect of the mechanism involves constructing health ontologies from the acquired datasets and identifying the commonalities between these ontologies and those representing the HL7 FHIR resources. Subsequently, the datasets are translated into the HL7 FHIR standard. The Data Interoperability mechanism is implemented as a Chained Network Service in the 5GC, with each of the three different medical scenarios being allocated to its respective network slice. While the mechanism operates similarly for each network slice, the execution speed varies based on the computational requirements of the particular medical scenario. The Data Interoperability mechanism consists of four steps, including the ontology building system, syntactic similarity identifier, semantic similarity, and overall ontology mapper.

Verma et al in 2018 [

3] described a cloud-centric IoT-based framework to monitor disease diagnosis and automatically predict potential diseases and their severity levels without the involvement of healthcare professionals. Moreover, these platforms not only offer physicians technologies that simplify the healthcare process but also provide them with tools to aid clinical decision-making. This has widely promoted the use of IoMT to improve healthcare and is now considered a pillar of new ubiquitous healthcare services [

4].

Azariael al in 2016 [

5] proposed a solution to tackle the problem of medical data security by utilizing smart contracts on the Ethereum blockchain. Their Smart Contract comprises three sub-contracts, including a Registrar Contract that links the user’s identity to their Summary Contract on Ethereum. The Summary Contract is utilized by patients to monitor their medical records and the Patient-Provider Relationship (

PPR) Contract. The PPR Contract is responsible for managing the patient-provider relationship and defining pointers to query and retrieve patient data from the provider’s database. To share data with third parties, the patient node retrieves the PPR containing the desired data query and updates the third party’s PPR with the query and a hash code for the requested data. The third-party node then accesses the provider’s database, with the assistance of a gatekeeper that authenticates the signature of the original provider by analyzing the hash code, to recover the data.

Boutros-Saikali et al in 2018 [

6], presented an implementation of the FHIR standard by proposing an IoMT platform that allows monitoring of patient biometric data by doing a weekly monitoring of Body mass index (

BMI) status and referral data to patients when needed, or monitoring the patient activities daily by the platform in order to compare the statistics of the differences presented between the objectives of each patient and their real activity and send to them à set of recommendations if needed, the control of the blood pressure of the patients will be monitored daily in relation to the minimum and maximum thresholds to indicate to them the critical values if they are detected, as well as the daily follow-up of Blood glucose identified from different IoTs systems, this platform takes advantage of the artificial intelligence algorithm and the standardization of data formats. data that comes from the IoMTs network to provide practitioners with a virtual patient assistant, something that will help them identify abnormal situations by tracking data over time and then predict potential short or long-term dysfunction in order to ignite red light and advice them to act quickly.

The Pulmonary Vascular Research Institute, which comprises healthcare professionals and researchers focused on pulmonary hypertension (PH), is collaborating to establish an international registry/data repository for PH.

Sony et al in 2021 [

7] proposed a semantic interoperability model related to medical health with the use of Healthcare Sign Description Framework (

HSDF), based on the sign science "Semiotics" in order to ensure a good level of semantic interoperability of the data exchanged between several medical entities to avoid all problems of disambiguation of the meaning of the notes and to improve in term of accuracy and similarity while using UMLs unified modeling language System).

Jabbar et al in 2017, [

8] proposed an IoT-SIM model for achieving semantic interoperability among heterogeneous IoT devices in healthcare. The aim of the model was to enable physicians to remotely monitor their patients using various IoT devices, regardless of the vendor, by leveraging semantically annotated data. To this end, RDF was utilized to represent patients’ raw data in a meaningful manner. The model involved using IoT devices to diagnose diseases and semantically annotate the resulting information using RDF. A lightweight model was also proposed for semantically annotating data from heterogeneous IoT devices, which included descriptions of communication among these devices. The SWE framework was employed to enable sensors and devices to communicate with each other and provide web services. To ensure interoperability, the collected data was mapped to an RDF graph database, analyzed, and annotated for semantics. After the collected data was annotated, it was transmitted to the Intelligent Health Cloud for matching with the pharmaceutical companies’ prescribed medicines. The resulting information was then transmitted to the patient’s IoT devices, along with details about the prescribed medicine. The RDF graph database was used to represent the patients’ diseases database in triples, allowing it to be queried semantically using SPARQL.

Jaleel et al in 2020 [

9] introduced MeDIC, a framework designed to enhance medical data interoperability among healthcare devices. MeDIC leverages translation resources at the network edge through its probing and translating agents, improving upon existing cloud-based IoMT approaches. MeDIC’s probing agents maintain a list of local MeDIC devices and facilitate data conversion requests between devices when a device lacks the capability for such conversion. The receiving device’s translating agent then converts the data into the required format and returns it to the requesting device. These innovative agents enable IoMT devices to share computing resources and minimize reliance on cloud access for data translations.

Fischer et al in 2020 [

10] proposed a medical data interoperability model based on the HL7/FHIR standard and ETL aims to ensure the research and analysis of patient medical data which is in formats heterogeneous and to interrogate them above all in this register and adapt them to a common data model called Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (

OMOP), to achieve this model a set of domain knowledge experts have defined a group of common parameters, which have been mapped to standardized terminologies such as LIONIC or SNOMEDCT, then this data was extracted in FHIR format via Extract Transform Load (

ETL) and transformed using XSLT in OMOP format in a reasonable time, the additional advantage of this model is that it allows practitioners to connect several heterogeneous databases. However, in adopting this platform, a complete ETL process must be implemented for each source separately, which will generate significant processing time in the event of massive data.

Zong et al in 2020 [

11], proposed to design, develop and evaluate a computational system based on the FHIR standard that enables the automation of the filling of Case Report Forms (

CRFs) for cancer clinical trials using Electronic Health Records (

EHRs) real to represent the CRFs and their data population, they leveraged an existing FHIR-based cancer profile to represent colorectal cancer patient EHR data, and then used FHIR Questionnaire and Questionnaire Response resources to represent CRFs and their data population as well as they used synoptic reports of 287 Mayo Clinic patients with colorectal cancer from 2013 to 2019 with standard measures of precision, recall, and F1 score to test the accuracy and overall quality of the pipeline. Hong et al in 2017 [

12], have proposed an interactive platform developed using shiny framework and R packages for the generation of statistics and analyzes of patient clinical data in FHIR format.

The proposed solution by Ullah et al in 2017 [

13] entitled SIMB-IoT model, is dedicated to presenting a new model of semantic interoperability to guarantee interoperability between several connected medical objects which prevent from different manufacturers and which generates a very important content of data related to the field of health care, in order to make available to patients and practitioners, a drug recommendation system for the different symptoms collected from these connected objects, which then makes it possible to avoid the side effects of drugs according to the history of each patient.

5. Comparative study of data Interoperability models

This section is composed of two parts. The first one identifies the different possible modes of interoperability with the data. The second one proposes a synthetic study and an analyze of data interoperability models.

5.1. Data Interoperability

Interoperability can be defined as the ability to store, transfer and retrieve data from different sources in a fast and efficient way. It is subdivided into several types, technical interoperability; signified the physical connectivity established between the object to exchange bits and bytes, it is possible to exchange data but also contexts and information, focusing on the understanding of information as an integration object without using it, in this interoperability level the use of Electronic Health Records (EHR) is recommended in order to exchange Infrastructure and governance (persons/citizens, public health /research institutions, national digital health bodies, data protection authorities, health professionals and generates and patient associations), Semantic interoperability; where the Use of international standard reference systems and ontologies European Interoperability Framework (EIF) are recommended in order to describe the unambiguous representation of clinical concepts and also the use of the ISO 23903 standard is highly recommended t.and could be considered a useful guide in terms of establishing semantic interoperability in the European Health Data Space (EHDS), Dynamic interoperability; information, its use, and applicability, i.e. knowledge can be exchanged, focusing on contextual changes events as integration objects. The most prominent exchange format for health data is Health Level Seven (HL7) Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) in order to exchange medical data resources in different formats, Syntactic interoperability; data can be exchanged in standardized formats, with the same protocols and formats supported, which is achieved when health data is kept in standardized data formats thanks to the use of XML or Rest format European Interoperability Framework (EIF); Service interoperability: exchange of services between two software, Communication interoperability; focus on data information as an integration object without context, ability to exchange data and use information as an integration object, i.e. data format and syntax and the last and the main level is the organizational level in which interoperability will be achieved when processes, user roles, and access rights are harmonized and clearly defined.

5.2. Comparative study between data Interoperability models

Table 2 describes the pros and cons of the various health data interoperability models by describing the type of interoperability addressed by the data type.

6. Discussion and work limitations

In 2019, Mavrogiorgou et al [

1] proposed a solution for FHIR data acquisition and transformation via 5G network slicing. The platform they proposed can effectively manage healthcare data, leveraging the latest data acquisition, 5G network slicing, and data interoperability techniques. this platform solves the problem of heterogeneity of medical data by transforming data via 5G from medical objects into FHIR resources, but this solution remains limited to meeting research and high processing requirements on the FHIR data. Verma et al in 2018 [

3] proposed a three-phase conceptual framework for an IoT-based m-Health Monitoring system. In the first phase, users’ health data is collected from medical devices and sensors and sent to a cloud subsystem using a gateway or Local Processing Unit (

LPU). In phase 2, the medical measurements are used by a medical diagnosis system to make a cognitive decision regarding the individual’s health. In phase 3, alerts are generated for caregivers or parents regarding the person’s health status. In case of an emergency, alerts are also sent to nearby hospitals to handle the medical emergency. However, their solution did not address the interoperability of medical data and did not implement any standard, such as the FHIR standard, for data interoperability. While Azaria et al in 2016 [

5], proposed a solution that will be used by patients to track their medical records and the Patient by analyzing the hash code originally generated by the originating Provider and Provide Relationship (PPR) Contract, which ensures semantic interoperability and security of medical data but the problem with this solution is that it does not present a centralized data architecture which patients can use for storing and retrieving their medical data in the desired format. Boutros-Saikali et al in 2018 [

6], proposed an IoMT platform as well as a virtual doctor and monitoring application which aims to provide a solution to ensure the interoperability of monitoring applications and their security as a proof of concept, to the use of the interoperability standard of FHIR medical data, and the REST API, but this solution has the same limitations related to demanding research and high processing requests on medical data with the FHIR standard as the platform proposed by Verma et al in 2018 [

3]. Sony et al in 2021 [

7] described a centralized semantic interoperability model which ensures the interoperability of data by means of UMLS ontology and HDFS which presents an improved model in terms of accuracy and similarity of healthcare signs, vital signs, medication signs or symptom signs, while these data must be exchanged between several medical entities in a unified format hence the need for a standard to ensure organizational interoperability in order to ensure the storage and retrieval of these signs which are on different forms with a standardized form. Jaleel et al in 2020 [

9], This article presents the MeDIC

7 platform, a framework for the interoperability of medical data through the collaboration of health devices. MeDIC which integrates both polling agents orchestrates translation requests according to the capacity of each of the Medic devices and by the translation resources which then allow the data to be converted into the required format to another which allows users of IoMs to minimize access to the cloud. While Fischer et al in 2020 [

10] have proposed a model based on ETL in order to extract, transform and load medical data from different databases in FHIR form but the implementation of this solution is heavy and does not respond to a complicated request for medical data, the same limit is for the model proposed by Zong et al in 2020 [

11]. The performance of the framework Shiny FHIR proposed by Hong et al in 2017 [

12] does not ensure research in a larger mass of medical data which limits access to the records and does not provide a framework for the generation of data in a specific format equivalent or not to the data format of the source as well as other technical issues related to interoperability with new versions of the FHIR standard. While Ullah et al in 2017 [

13] proposed a SIMB-IOT model as a semantic interoperability model for heterogeneous IoMT devices by the use of an RDF database constricted based on two different databases, the first one is a database of diseases including drugs details and the second database contain medicines with an overview of their side effects presented in a graphical form, that can be easy views and supervised by patients and doctors simultaneously by the use of SPARQL, but this model does not cover the transformation of medical data formats into the format desired by patients and practitioners but sends them recommendations. Finally, we must mention the limitations of our work. Only the main interoperability standards have been considered, our inventory is not exhaustive. State-of-the-art was not achieved following a systematic review methodology. The comparison of standards has been achieved on the basis of the literature but not on the concrete implementation of them.

We have argued the potential use of the FHIR standard which can be used to develop patient monitoring and diagnostic applications and help practitioners and medical entities achieve a high level of data interoperability.

7. Conclusions and perspectives

In this paper, we focused on the main standards used to describe and characterize data in the medical field. We continued by the identification of standards allowing data compatibility and ensuring their interoperability. Afterward, a state-of-the-art allowed us to analyze concrete implementation on real use cases and highlight the pros and the cons of all these approaches. This analysis enabled us to identify and discuss ideal features of the data interoperability model for the medical field.

The analysis of the literature has shown that each of the models that we have studied in the state of the art presents different limits on the technical side or on the standardization side of medical data, To alleviate these limitations, we identify features of the ideal reference model. This model is characterized by the capacity to identify medical data in any type by a medical entity and store them in a centralized database in a unified format and extract it from this database by another entity in the desired format while drawing advantage of the technologies used in the previously proposed models that we have studied as an example UMLS that can help us to ensure the study of similarities with an ontological medical data identified from different medical databases, the cloud that can be used for medical data storage, and the ETL that can help us for the extraction, transformation and construction of a structured database.

In our future works, based on the state-of-the-art analysis and the conclusion of this paper, we will develop our own reference model of interoperability systems and then build our own interoperability architecture.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A.A. and O.D.; methodology, R.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.A.A. and O.D.; writing—review and editing, R.A.A. and O.D.; supervision, S.M. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by ARES, and Infortech and Numediart research institutes. The APC was funded by MDPI Information.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to express their gratitude to ARES, Infortech and Numediart institute for the research funding and MDPI Information for the APC funding. This research was conducted as part of the first author’s postdoctoral fellowship.

Conflicts of Interest

The second author is the guest editor of the special issue.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 5GC |

5G Core |

| 5G OSM-MANO |

Framework: 5G, Open Source Management and Orchestration Framework |

| ACP |

Australian Colorectal Cancer Profile |

| API |

Application Programming Interface |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| CDA |

Clinical Document Architecture |

| CDM |

Clinical Document Management |

| CIOT |

Cloud-centric IoT based disease diagnosis healthcare framework |

| CRF |

Case Report Form |

| CSV |

Comma-separated values |

| DICOM |

Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine |

| EDC |

Electronic Data Capture |

| EHDS |

European Health Data Space |

| EHR |

Electronic Health Records |

| EIF |

European Interoperability Framework |

| ETL |

Extract, transform, load |

| FCAT |

Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminology |

| FHIR |

Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources Standard |

| HSDF |

Healthcare Sign Description Framework |

| HL7 |

Health Level Seven |

| HSDF |

Healthcare Sign Description Framework |

| IA |

Artificial Intelligence |

| IoMT |

Internet of Medical Things |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| IoTMD |

Input-Data coming from any IoT device |

| IoT-SIM |

IoT-based Semantic Interoperability Model |

| ISO |

International Organization for Standardization |

| JSON |

JavaScript Object Notation |

| KNN |

K-Nearest Neighbors |

| LPU |

Local Processing Unit |

| MeDic |

Medical Data Interoperability through Collaboration of healthcare devices Framework |

| Medra |

Repository: Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities |

| MedRec |

Decentralized Medical record management system to handle EMRs, nusing blockchain technology |

| NEMA |

National Electrical Manufacturers Association |

| NLP |

Natural Language Processing |

| OmH |

Open Medical Health |

| OMOP |

Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership |

| PPR |

Patient-Provider Relationship |

| RDF |

Resource Description Framework |

| RIM |

Reference Information Model |

| Shiny FHIR |

Integrated framework leveraging Shiny R and HL7 FHIR |

| SIMB-IoT |

Semantic Interoperability Model for Big-data in IoT |

| SIM-HIOT |

Semantic Interoperability Model in Healthcare Internet of Things Using Healthcare Sign Description Framework |

| SPARQL |

SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language |

| SWE |

Sensor Web Enablement |

| TA |

Terminologia Anatomica |

| UDR |

User Diagnosis Result |

| UML |

Unified Modeling Language |

| UMLs |

Unified Medical Language System |

| VD |

Virtual Doctor |

| XML |

Extensible Markup Language |

| XPath |

XML Path Language |

| XSLT |

Extensible Stylesheet Language Transformations |

References

- Mavrogiorgou, A.; Kiourtis, A.; Touloupou, M.; Kapassa, E.; Kyriazis, D. Internet of medical things (IoMT): acquiring and transforming data into HL7 FHIR through 5G network slicing. Emerg. Sci. J 2019, 3, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Cheng, D.; Deng, Z.; Zong, M.; Deng, X. A novel kNN algorithm with data-driven k parameter computation. Pattern Recognition Letters 2018, 109, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Sood, S.K. Cloud-centric IoT based disease diagnosis healthcare framework. Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing 2018, 116, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarda, T.; Augusto, M.F.; Barrionuevo, O.; Pinto, F.M. Internet of Things in pervasive healthcare systems. In Next-Generation Mobile and Pervasive Healthcare Solutions; IGI Global, 2018; pp. 22–31.

- Azaria, A.; Ekblaw, A.; Vieira, T.; Lippman, A. Using blockchain for medical data access and permission management’. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Open and Big Data (OBD).(Vienna, 2016), 2016, pp. 1–2.

- Nicole Boutros-Saikali, N.; Saikali, K.; Abou Naoum, R. An IoMT platform to simplify the development of healthcare monitoring applications. In Proceedings of the 2018 Third International Conference on Electrical and Biomedical Engineering, Clean Energy and Green Computing (EBECEGC). IEEE, 2018, pp. 6–11.

- Sony, P.; Nagarajan, S. Semantic Interoperability Model in Healthcare Internet of Things Using Healthcare Sign Description Framework. IAJIT 2022, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Jabbar, S.; Ullah, F.; Khalid, S.; Khan, M.; Han, K. Semantic interoperability in heterogeneous IoT infrastructure for healthcare. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaleel, A.; Mahmood, T.; Hassan, M.A.; Bano, G.; Khurshid, S.K. Towards medical data interoperability through collaboration of healthcare devices. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 132302–132319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, P.; Stöhr, M.R.; Gall, H.; Michel-Backofen, A.; Majeed, R.W. Data integration into OMOP CDM for heterogeneous clinical data collections via HL7 FHIR bundles and XSLT. In Digital Personalized Health and Medicine; IOS Press, 2020; pp. 138–142.

- Zong, N.; Wen, A.; Stone, D.J.; Sharma, D.K.; Wang, C.; Yu, Y.; Liu, H.; Shi, Q.; Jiang, G. Developing an FHIR-based computational pipeline for automatic population of case report forms for colorectal cancer clinical trials using electronic health records. JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics 2020, 4, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, N.; Prodduturi, N.; Wang, C.; Jiang, G. Shiny FHIR: an integrated framework leveraging Shiny R and HL7 FHIR to empower standards-based clinical data applications. Studies in health technology and informatics 2017, 245, 868. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ullah, F.; Habib, M.A.; Farhan, M.; Khalid, S.; Durrani, M.Y.; Jabbar, S. Semantic interoperability for big-data in heterogeneous IoT infrastructure for healthcare. Sustainable cities and society 2017, 34, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).