1. Introduction

The Cu-Cr series high-strength and high conductivity alloys are typical precipitation strengthened alloys with high strength and excellent electrical conductivity, which have been widely applied in rail transit, electrical engineering, electronic packaging and some other fields [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. The strengthen of the Cu-Cr alloy mainly due to the Cr-rich precipitates, and properties of the alloy can be further improved through adding more alloy elements such as Zr, Ti, Mg, Ag and rare earth elements [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Among them, the Cu-Cr-Zr alloy is the most widely used, while the Zr element can be easily burned during the smelting process and therefore vacuum smelting is required [

12], resulting in high cost, which limits further wide application of the Cu-Cr-Zr alloy.

Earlier investigations reveal that adding an appropriate amount of Sn into the Cu-Cr alloy can enhance the solid solution strengthening effect and improve the tensile strength of the alloy [

13]. Meanwhile, the Sn is relatively cheap and not easy to be burned. Therefore, the Cu-Cr-Sn alloy does not need vacuum melting, and the manufacturing costs will be much lower. Meanwhile, its raw material cost is also lower. Whereas, thus far research reports on the Cu-Cr-Sn alloys is still quite lacked compared with that on the other Cu-Cr series alloys.

For the reasons above, in this study a Cu-Cr-Sn alloy was designed and prepared, and then subjected to cold-rolling, solid solution and aging treatment under different conditions. The evolutions in grain structure, precipitates, mechanical and electrical properties during the deformation and heat treatment processes were comprehensively characterized. The effects of rolling deformation and aging on microstructure as the well as properties of the alloy were analyzed, and the relationship between the electrical properties, grain structure and precipitates were discussed. It is hoped that this study can provide some basis for optimizing the manufacturing process of the Cu-Cr-Sn alloy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimens Preparation

Composition of the designed alloy is Cu-0.20Cr-0.25Sn (wt%), and was smelted with pure Cu (≥99.99%), pure Sn (≥99.95%) and Cu-10Cr (wt%) intermediate alloy in muffle furnace under Ar protection. The metals were heated to 1250 ºC, kept for 50 min and then casted in a graphite mold. Homogenization annealing of the alloy ingot was conducted in an Ar protected furnace at 960 ºC for 6 h, and cooled to room temperature with the furnace. An inductively coupled plasma emission spectrometer (ICP-OES, SPECTRO ARCOS II) was used to analyze the composition at different positions of the ingot, and the results showed that the average Cr content in the alloy was 0.201 wt%, and the Sn content was 0.246 wt%, which is close to the design composition, indicating that accurate control of the alloy composition was achieved under simple Ar shielded melting condition.

As the grains of the alloy after the homogenization annealing are coarse, the homogenization annealed ingot was pre rolled from 10 mm to 2 mm, and then annealed at 960 ºC for 1 h. Then, the alloy plate was further rolled to the thickness of 1.6 mm, 1 mm and 0.4 mm, and the corresponding rolling ratio is 20%, 50%, and 80%, respectively. The sample (2 mm) after annealing was named to be CR0, and the 20%, 50% and 80% cold rolled samples are named to be CR1, CR2 and CR3. The specimens were aged at 400 ºC and 450 ºC for different time and then the mechanical properties and electrical conductivity of these specimens were characterized.

2.2. Microstructure Characterization

The samples for microstructure characterization were first polished and then etched with FeCl3 hydrochloric acid ethanol solution (ethanol 100 ml + FeCl3 5 g + HCl 10 ml) for 25 s. The microstructure and phase of the alloy were characterized by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM, Sirion 200, FEI) and Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS).

2.3. Microhardness and Conductivity Tests

To measure the electrical conductivity and microhardness, the samples were firstly polished, and then the conductivity was measured using a Sigma 2008A digital conductivity meter. The microhardness was measured using a Vickers hardness tester (HV-1000) under a load of 200 g and a holding time of 10 s.

2.4. Tensile Test and Fracture Surface Observation

According to the effect of aging conditions on properties of the cold-rolled Cu-0.2Cr-0.25Sn alloy, the Cu-Cr-Sn alloy with different cold rolling deformation were aged under their peak aging parameters: CR1 (400 ºC, 2 h), CR2 (400 ºC, 2 h) and CR3 (400 ºC, 1.5 h). The aged specimens were named to be CR1-P, CR2-P, and CR3-P, respectively. The tensile and fracture behaviors of the specimens in peak aging states were studied. Besides, the peak aging parameter of the CR0 specimen was determined to be 450 ºC, 2 h. The CR0 specimen after peak aging was cold rolled from 2 mm to 0.4 mm, and named to be CR0-P. The effect of cold rolling and aging sequence on properties of the alloy was studied through comparing the CR3-P and CR0-P specimens. The processing sequences of all the specimens are presented in

Table 1.

For the tensile test, the cold-rolled plates were wire cut into bone shaped tensile specimens, with a total length of 80 mm, a gauge distance of 30 mm, and a transition arc radius of 5 mm. The tensile test was conducted on a universal testing machine (Zwick/Roell Z030) at a tensile speed of 2 mm/min, and the fracture surface was observed using the SEM.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microstructure and Properties of the Cold-Rolled CuCrSn Alloy

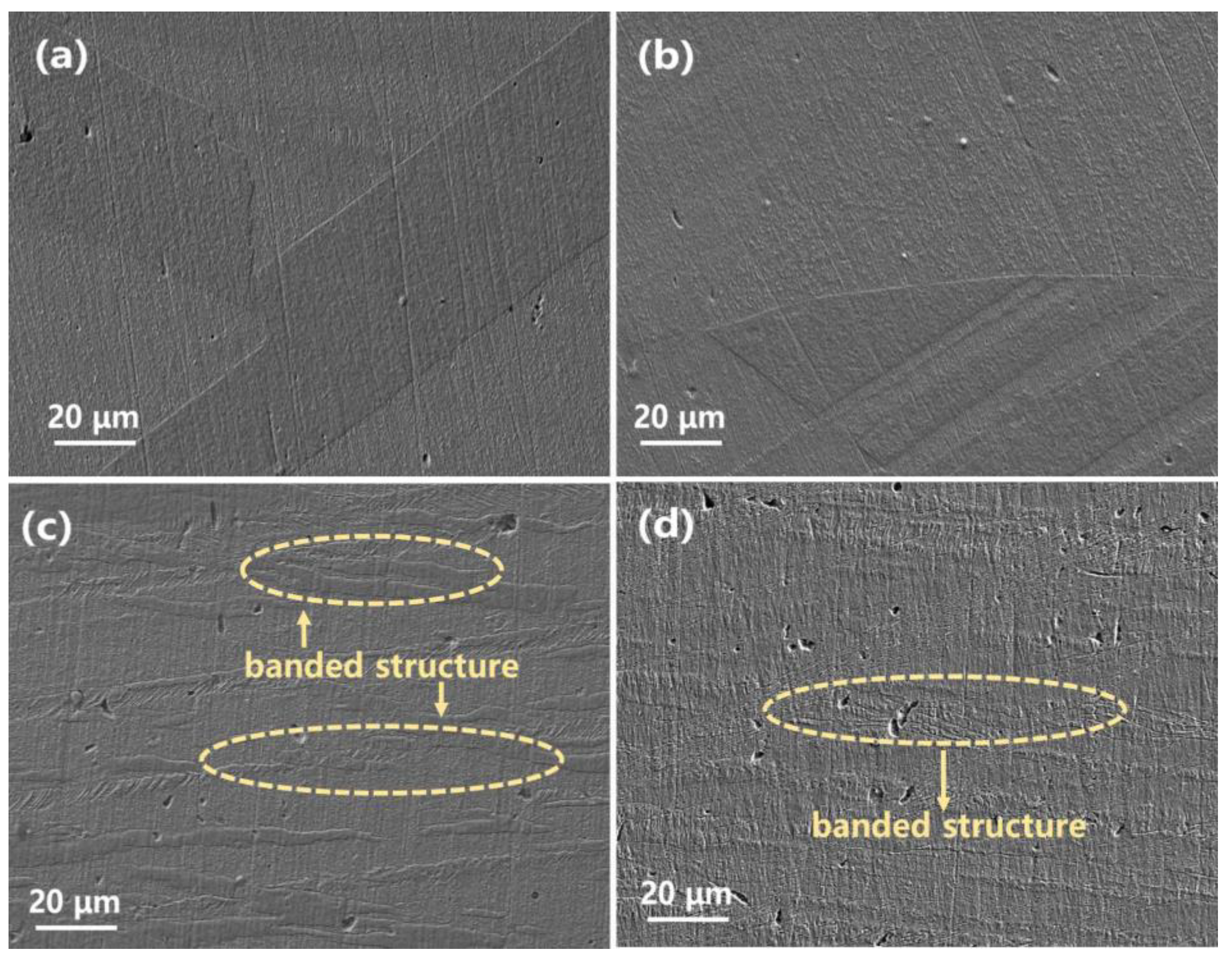

Microstructures of the Cu-0.2Cr-0.25Sn alloy plates annealed (solid solution) at 960 ºC for different time and then cold-rolled to different thicknesses are shown in

Figure 1. As can be seen in

Figure 1a, the texture formed during the pre-rolling process disappears after the solid solution treatment, and the annealing twin structure appears. Meanwhile, there are no obvious precipitation particles in the matrix, indicating that the alloy elements have been fully dissolved. From

Figure 1b–d, it can be seen that microstructure of the alloy changes with increasing rolling ratio. Due to the low rolling ratio, the CR1 alloy almost retains the high temperature annealing recrystallization structure (see

Figure 1b). As the rolling ratio increases, obvious strip-liked texture appear, and that in CR3 is more obvious and the grain boundary density is higher compared with CR2. Besides, the etched surface is coarser at higher rolling ratio, because the dislocations can promote the corrosion reaction [

14,

15].

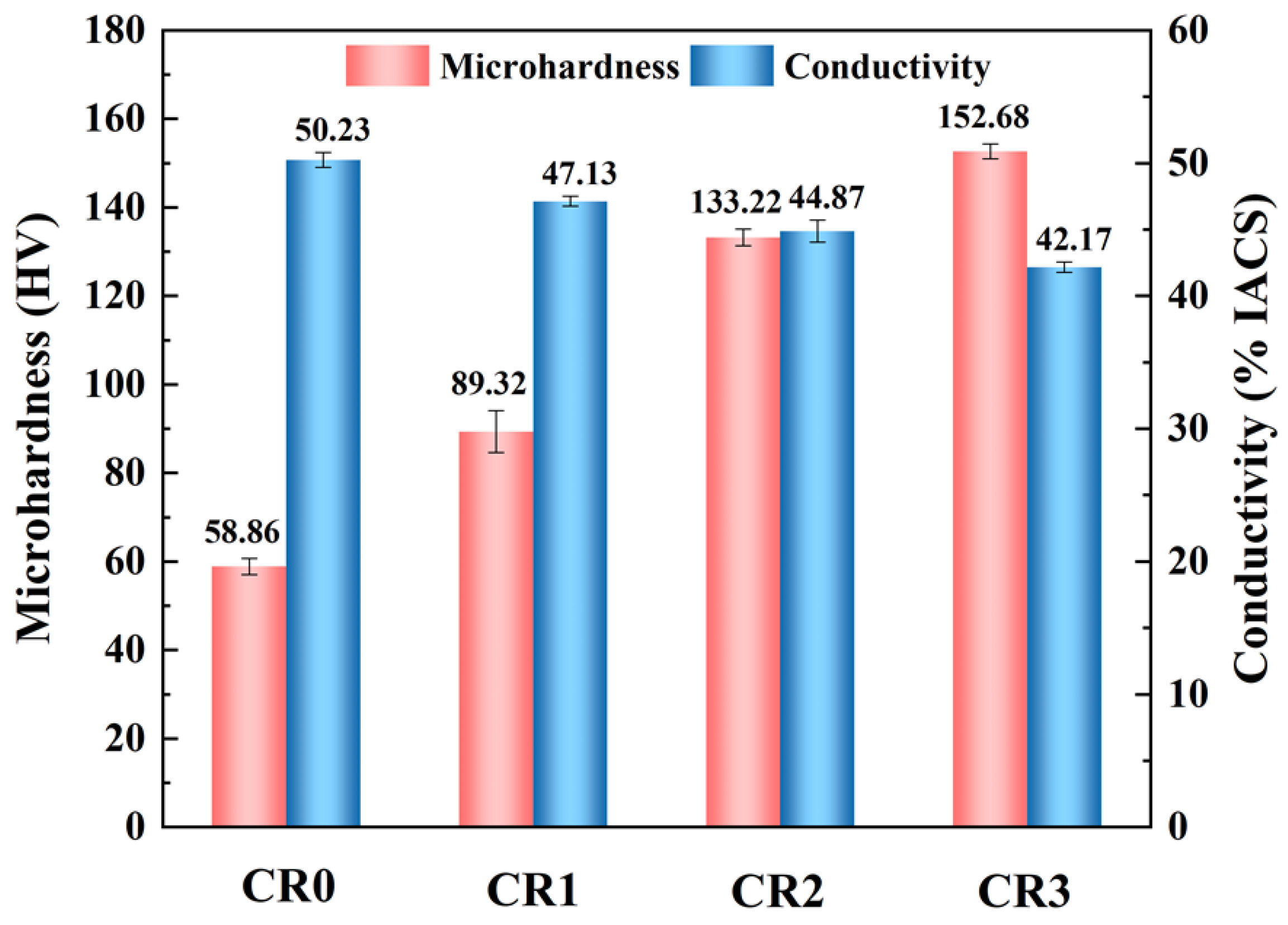

The microhardness and conductivity of the CR0, CR1, CR2 and CR3 specimens are shown in

Figure 2. Microhardness of the CR0 alloy is very low, because there is no deformation strengthening and precipitation strengthening in this specimen. With increasing rolling ratio, the microhardness increases continuously. In contrast, conductivity of CR0 is relatively high and deceases during the rolling process, because the defect density in the recrystallized Cu alloy is low, while the cold rolling introduces defects such as dislocations. The dislocations are intertwined with each other, forming a cutting order and resulting in a significant dislocation strengthening effect [

16,

17]. Besides, the dislocations have a certain degree of scattering effect on free electrons in the Cu matrix and thus decrease the conductivity.

3.2. Properties of the Cold-Rolled CuCrSn Alloy after Different Aging

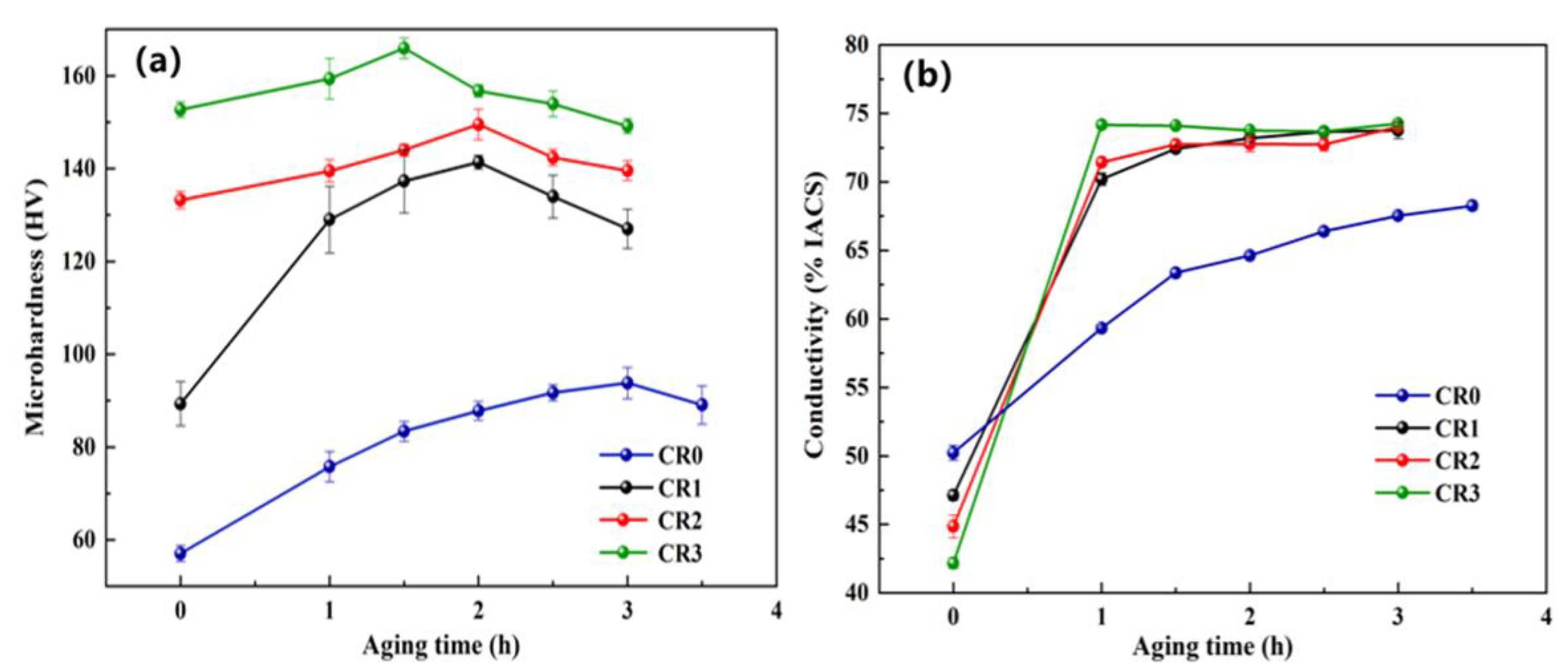

The evolutions in microhardness and conductivity of the CuCrSn alloy during the aging at 400 ºC are shown in

Figure 3. According to

Figure 3a, for all the specimens, the microhardness increases firstly and then decreases with increasing aging time. For the CR0 alloy, it can be found that the increase rates of microhardness and conductivity is much lower than the other three specimens, and the highest values of microhardness and conductivity are also much lower. One reason for that is the CR0 alloy has not undergone a cold rolling and lacks the deformation to promote precipitation, and the other reason is that precipitation power is insufficient at the aging temperature of 400 ºC. As a result, the CR0 alloy is in an underaged state at 400 ºC.

For the cold rolled specimens, the time for the alloy to reach the peak aging state decreases as the cold rolling ratio increases. Microhardness of the CR3 alloy reaches its peak after aging for 1.5 h, indicating that the cold deformation before aging can accelerate or promote the precipitation. With further prolongation of the aging time, the precipitates gradually grow and the alloy becomes overaged. i.e. the precipitation strengthening effect is weakened and the microhardness decreases. The conductivity firstly increases rapidly and then remains stable with increasing aging time, as presented in

Figure 3b. At the early stage of aging, the conductivity increases rapidly due to the rapid precipitation of alloy elements dissolved in the matrix. The larger the cold rolling ratio before aging, the higher increase rate of conductivity, which indicates that the cold rolling can promote the precipitation, because the internal defects in the grains can accelerate the diffusion and promote the nucleation of the second phase [

18,

19]. After that, only a little alloy element will be further precipitated, so the conductivity tends to stable. The stable conductivity of the CR1, CR2 and CR3 alloys are all around 74% IACS.

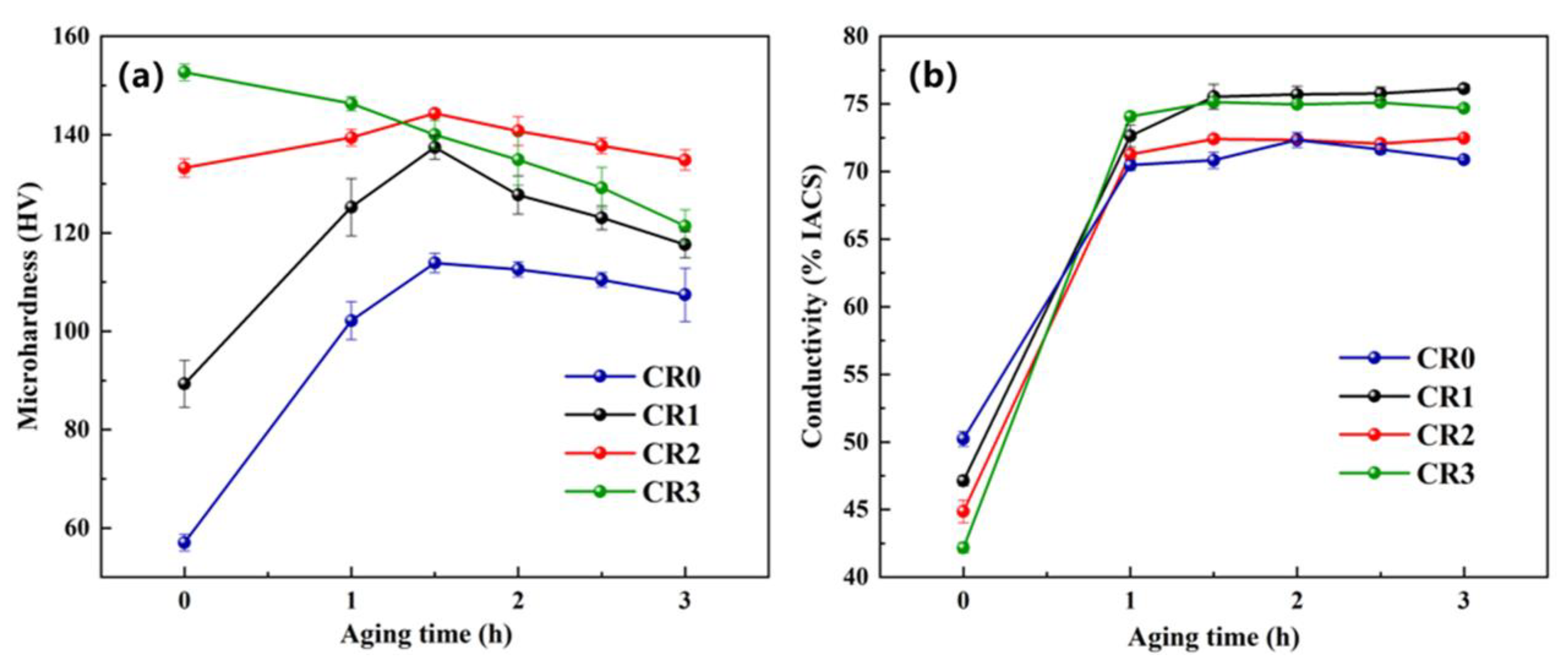

Figure 4 shows the evolutions in properties of the CuCrSn alloy during the aging at 450 ºC. From

Figure 4a, it can be seen that the increase rate for microhardness of the CR0 alloy increases significantly compared with that aged at 400 ºC, because the higher aging temperature increases the precipitation power of the second phase and promotes the precipitation. The time for the 4 specimens to reach the peak aging is shortened compared with that in

Figure 3, especially the CR3 alloy, for which the microhardness decreases monotonically with increasing aging time. As the cold rolling ratio of the CR3 is high, its initial microhardness was also high due to the severe strain hardening. During the aging process, the strain hardening decreases sharply, the precipitation hardening increases firstly and then decrease. Once the precipitation hardening can not make up the decrease of strain hardening, monotonic decrease in microhardness occurs. Besides, the peak hardness of the specimens aged at 450 ºC are lower than that aged at 400 ºC, indicating that 400 ºC is more suitable for the cold-rolled specimens. The variation in the conductivity shown in

Figure 4b is consistent with

Figure 4a, in which the conductivity of the CR0 alloy increases significantly. The higher aging temperature increases the precipitation driving force of the alloy and accelerates the precipitation rate. The conductivity of all the 4 specimens are higher than 70% IACS, some are about 75% IACS.

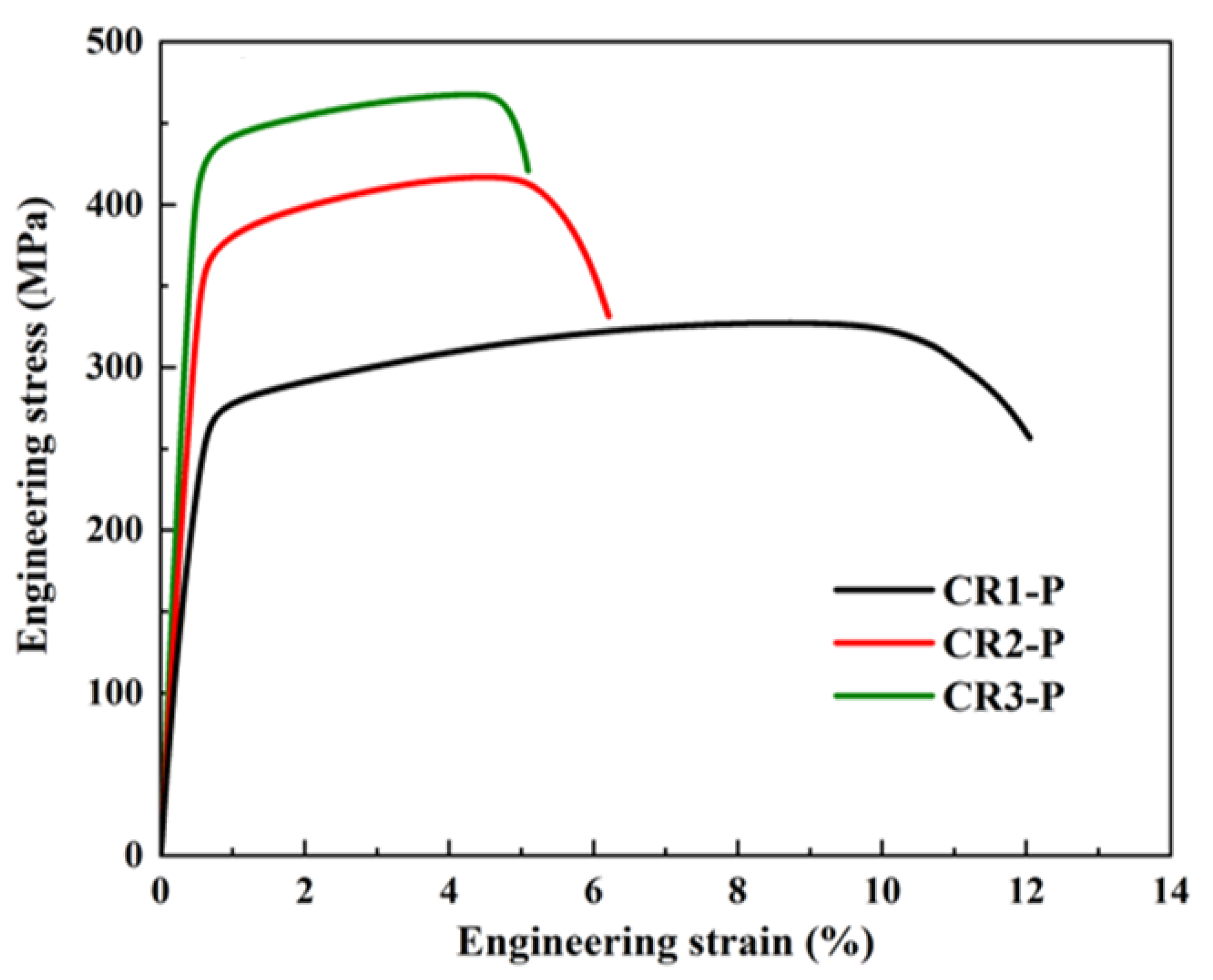

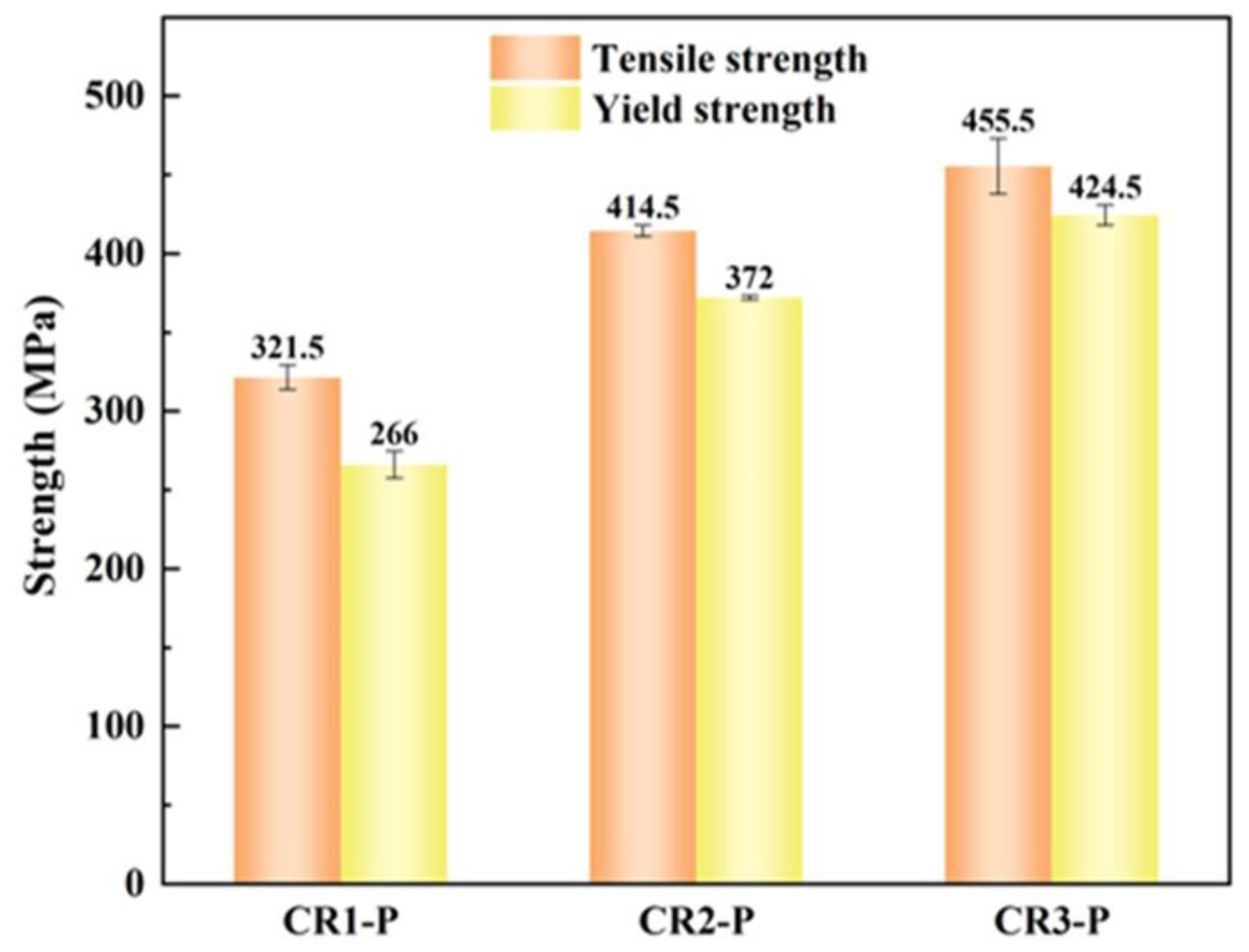

3.3. Tensile Behavior of the Peak-Aged CuCrSn Alloy

The Cu-Cr-Sn alloy specimens with different cold rolling ratios were aged under their peak aging parameters: CR1 (400 ºC, 2 h), CR2 (400 ºC, 2 h) and CR3 (400 ºC, 1.5 h), and the aged specimens were named to be CR1-P, CR2-P, and CR3-P, respectively. Tensile stress-strain curves of the CR1-P, CR2-P and CR3-P specimens are shown in

Figure 5, and their strength are presented in

Figure 6. It can be found that with increasing cold rolling ratio before aging, the yield strength and tensile strength increase obviously. One reason for that is the dislocations in the cold rolled specimens can promote the nucleation of the precipitates, and then higher density and finer precipitation particles can be formed thus the CR3-P specimen has much higher strength. Part of the deformation strengthening might be maintained, but should be not significant at the aging temperature of 400 ºC [

20,

21]. As the elongation decreases with increasing strength, it can be predicated that the increase in strength mainly attributes to the precipitation strengthening rather than fine grain strengthening.

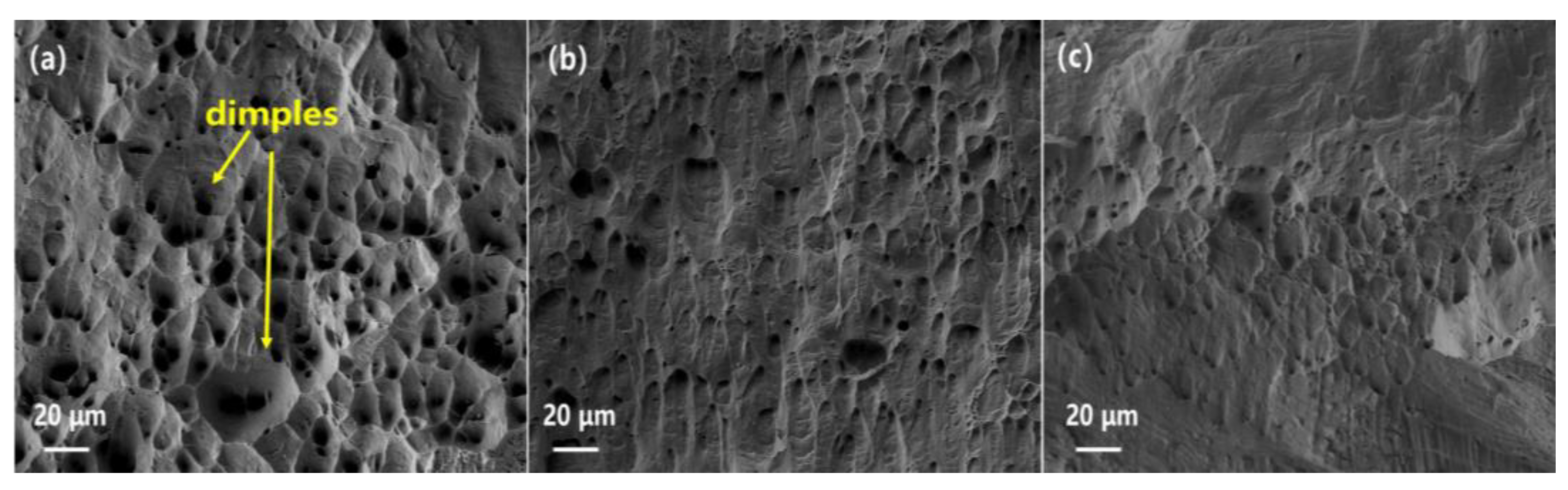

The microscopic fracture surfaces of the peak aged specimens are shown in

Figure 7. For all the three specimens, dimples were formed on the fracture surface, demonstrating that the specimens fracture in a ductile mode. For the CR1-P specimen, the dimple is relative large in size and deep, indicating a better plasticity. With higher cold rolling deformation before the aging, the dimples become smaller and shallower, corresponding to higher strength and lower elongation. The fracture surfaces fit well with the tensile curves and the strength.

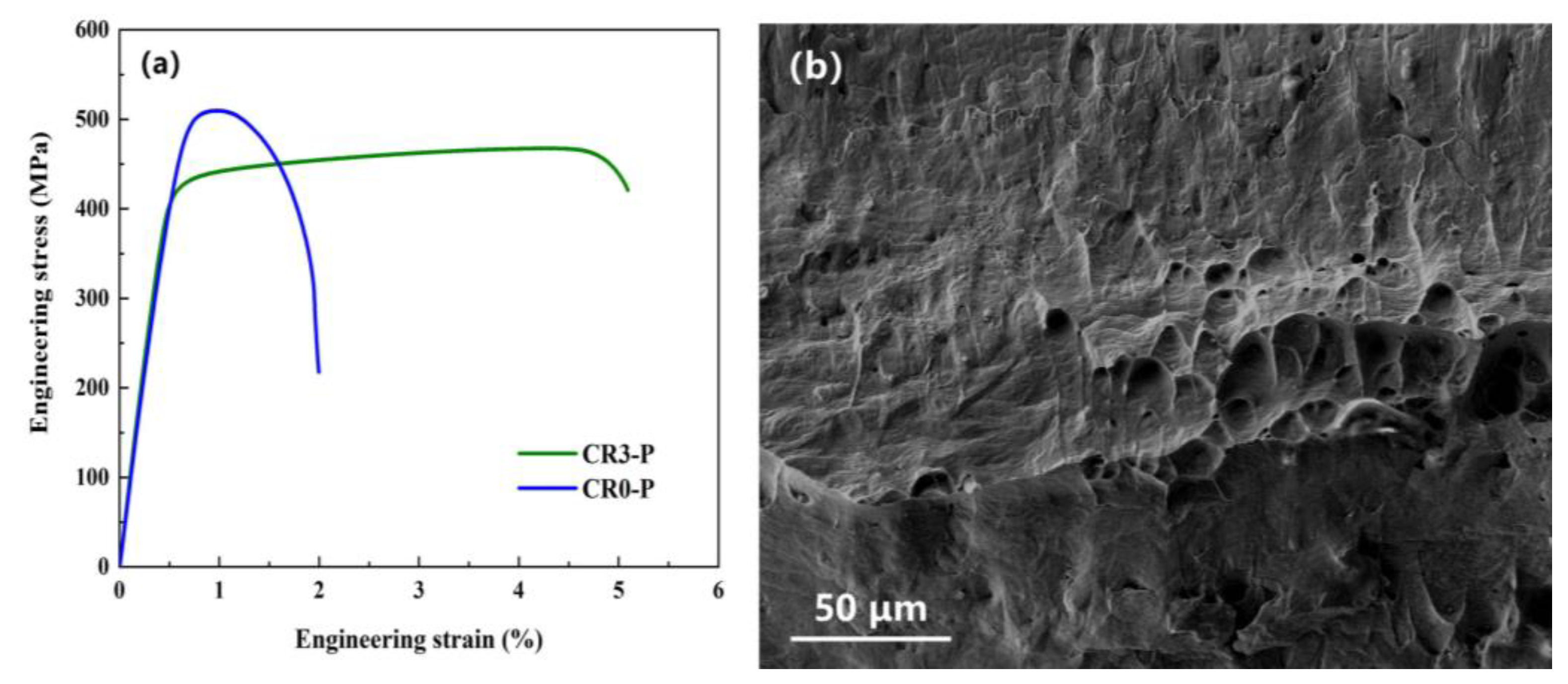

3.4. Properties of the CuCrSn Alloy Cold-Rolled after Aging

The deformation-aging processing has significant influence on the microstructure and properties of the Cu alloys. As the tensile strength of the CR3-P is only 455.5 MPa, the “solid solution-peak aging-cold rolling” was used to further improve the strength of the Cu-Cr-Sn alloy. The CR0-P specimen was pre-rolled from 10 mm to 2 mm, solid solution treated at 960 ºC for 1 h, aged at 450 ºC for 2 h and then cold-rolled to 0.4 mm. Then tensile curves of the CR0-P and CR3-P specimen are shown in

Figure 8a, from which one can found that the tensile strength of the CR0-P specimen is over 500 MPa, even much higher than that of the CR3-P, but its elongation decreases sharply. The fracture surface of the CR0-P also reveal that the decrease in ductility. As shown in

Figure 8b, the fracture surface is flat, only a few shallow dimples can be observed, while there is still little cleavage on the fracture surface.

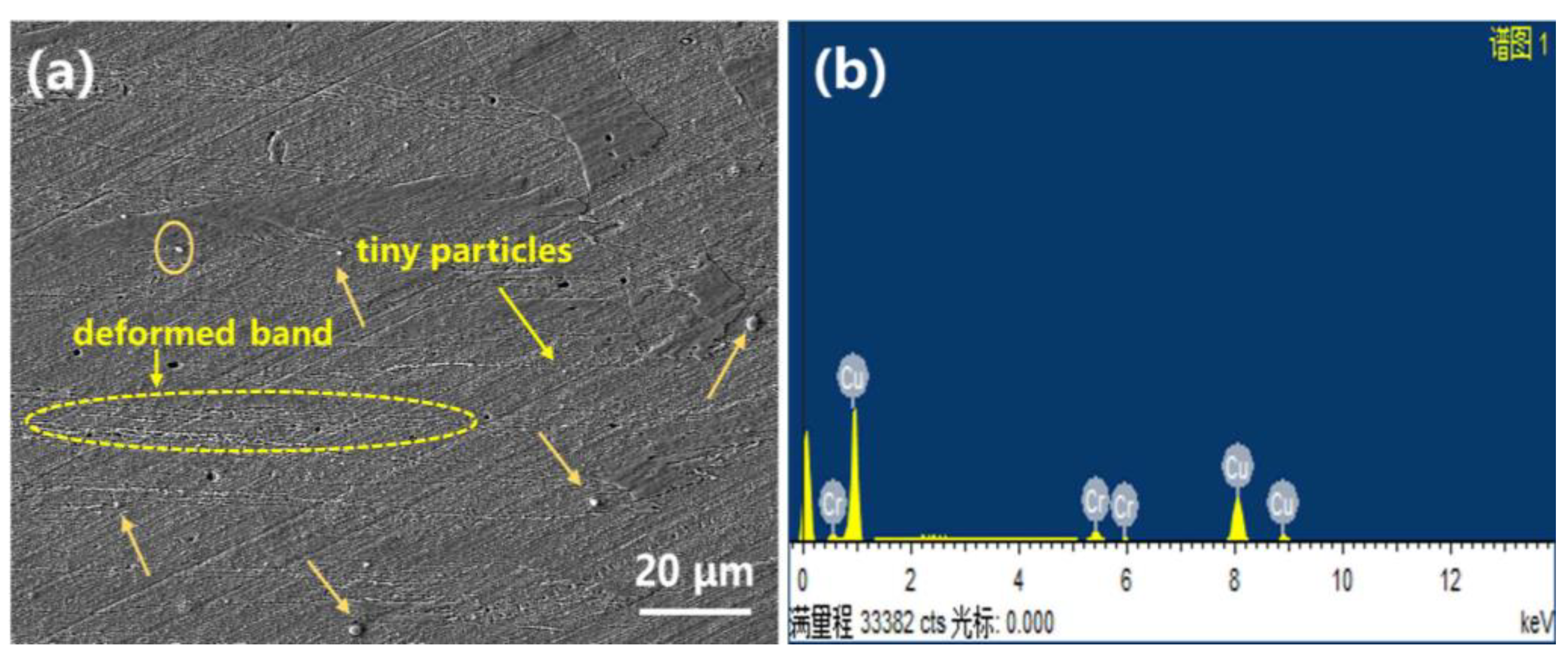

The microstructure of the CR0-P specimen and EDS analysis result on particles in this specimen are shown in

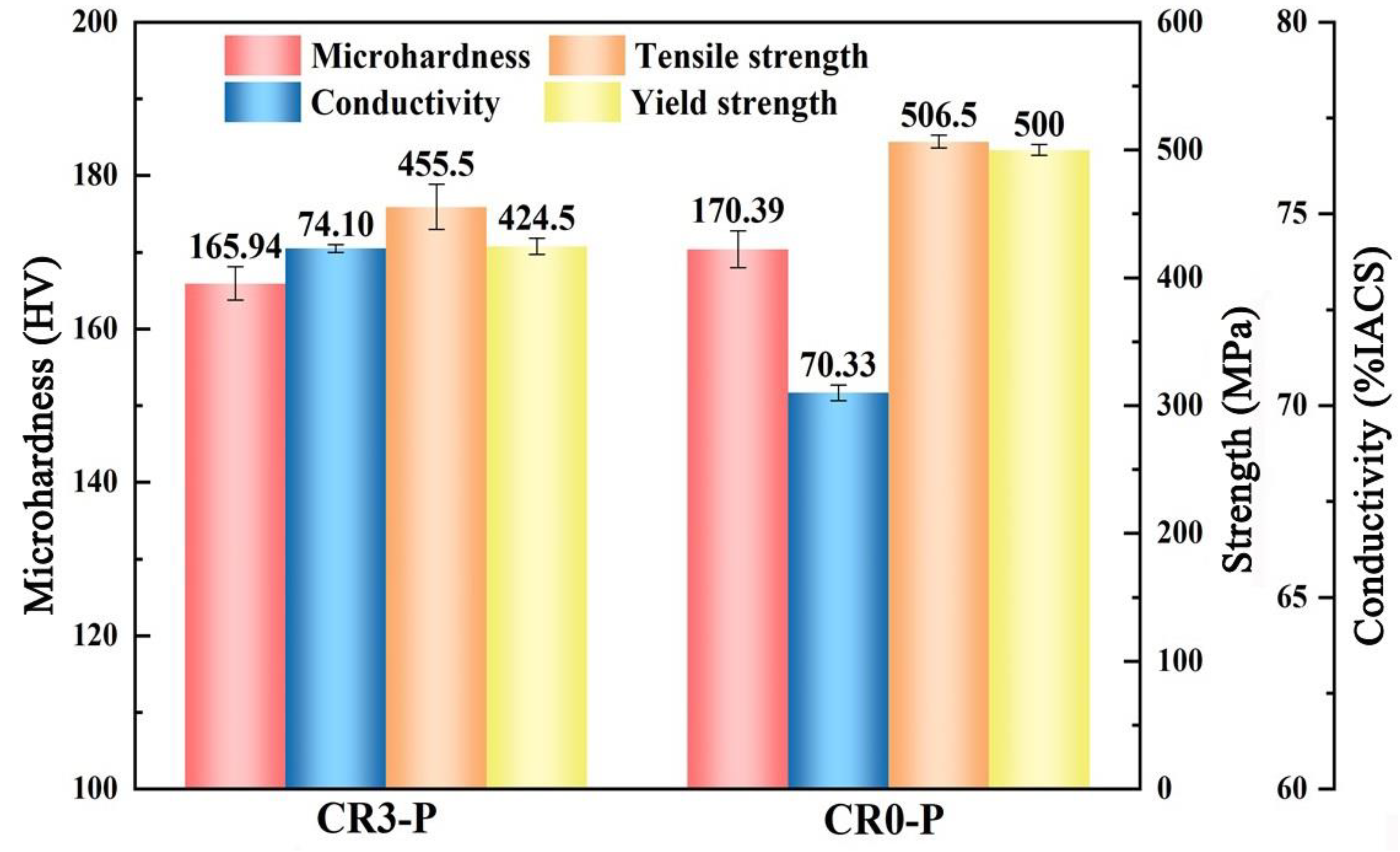

Figure 9. In the microstructure image, rolling deformation bands can be observed, and dispersed fine white particles exist in the Cu matrix, as indicated by the arrows. The EDS analysis result reveal that these precipitates are Cr-rich particles, which are formed during the aging process and act as strengthening phase, while the cold rolling after the aging further improves the strength. The properties of the the CR0-P and CR3-P specimens are summarized in

Figure 10, in which it is obvious that the yield strength, tensile strength and microhardness of the CR0-P specimen are higher, only the conductivity is a little lower, but still higher than 70%.

According to the results above, microhardness of the solid solution treated Cu-0.2Cr-0.25Sn specimen increases by 54 HV after the peak aging, from 59 HV to 113 HV. After a further 80% cold rolling, the microhardness increases to 170 HV (CR0-P). For this specimen, the strengthen attributes to combined effects of precipitation strengthening and deformation strengthening. With another processing method, microhardness of the Cu-Cr-Sn specimen increases from 59 HV of the solid solution state to 152 HV of the 80% cold-rolled state before aging. Then, the microhardness increases to 165 HV after the peak aging, which indicates that under the “solid solution-cold rolling-aging” process, the contribution of deformation strengthening is not significant, because the aging will eliminate the dislocations introduced during the cold rolling process [

21,

22]. Although the cold rolling decreases the conductivity of the CR0-P specimen by a few percentages of IACS, it is still higher than 70% IACS. Through comparing the properties of the CR3-P and CR0-P specimens, it can be concluded that adjusting the sequence of cold rolling and aging can improve the strength of the Cu-Cr-Sn alloy and meanwhile maintain a superior conductivity.

4. Conclusions

The influences of cold rolling ratio and aging parameters on microstructure and property of Cu-0.2Cr-0.25Sn alloy were investigated in this study. Based on the results and discussions, the following conclusions can be drawn:

(1) The cold rolling can change the coarse recrystallization structure of the alloy and forms deformation texture and bands with severe plastic deformation. High density of dislocations was introduced during the cold rolling process, which significantly increase the microhardness but will decrease the conductivity.

(2) The microhardness increases firstly and then decreases during the aging process, while the conductivity increase rapidly at the early aging stage and then becomes stable. The cold rolling before the aging can accelerate the precipitation process, and the peak microhardness is also higher for the specimen with higher cold rolling ratio before aging. The most suitable aging temperature is related with the cold rolling ratio before aging. Improving the aging temperature shortens the time of peak aging.

(3) Through aging firstly and then conduct a cold rolling, the strength of the Cu-0.2Cr-0.25Sn alloy can be further improved, because the precipitation strengthening and deformation strengthening are both significant in this condition, and the conductivity can still maintain a relative high level. A tensile strength of 506.5 MPa and a conductivity of 70.33% IACS were obtained for the specimen with the processing of annealed at 960 ºC for 1 h, aged at 450 °C for 2 h and then a 80% cold rolling.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.Z. and F.L.; methodology, Q.Z. and T.C.; investigation, T.C.; resources, T.C. and X.F.; writing-original draft preparation, T.C.; writing-review and editing, Q.Z. and C.X.; supervision, Z.S.; funding acquisition, F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the “Scientific and Technological Innovation 2025” Major Special Project of Ningbo City, grant number 2020Z039.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Y.R. Yao, W.S. Luo, C.T. Wang and R.R. Jiang for microstructure observation, microhardness, conductivity and tensile tests.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Cheng, J.Y.; Shen, B.; Yu, F.X. Precipitation in a Cu-Cr-Zr-Mg alloy during aging. Materials Characterization 2013, 81, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.D.; Xu, S.; Li, W.; Xie, J.X.; Zhao, H.B.; Pan, Z.J. Effect of rolling and aging processes on microstructure and properties of Cu-Cr-Zr alloy. Materials Science and Engineering A 2017, 700, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.L.; Liu, P.; Chen, X.H.; Zhou, H.L.; Ma, F.C.; Li, W.; Zhang, K. Effect of aging process on the microstructure and properties of Cu-Cr-Ti alloy. Materials Science and Engineering A 2021, 802, 140598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.Y.; Luo, F.X.; Xie, W.B.; Chen, H.M.; Wang, H.; Yang, B. The Effect of Precipitation Characteristics on Hardening Behavior in Cu-Cr-Sn Alloy with Sn Variation. Powder Metallurgy and Metal Ceramics 2020, 58, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.C.; Xie, W.B.; Chen, H.M.; Wang, H.; Yang, B. Effect of micro-alloying element Ti on mechanical properties of Cu-Cr alloy. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2021, 852, 157004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.S.; Wang, J.F.; Xiao, X.P.; Wang, H.; Chen, H.M.; Yang, B. Contribution of Zr to strength and grain refinement in Cu-Cr-Zr alloy. Materials Science and Engineering A 2019, 756, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.Z.; Li, Z.; Xiao, Z.; Zhu, H.R.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, F.Y. Microstructure and properties of a novel Cu-Cr-Yb alloy with high strength, high electrical conductivity and good softening resistance. Materials Science and Engineering A 2020, 795, 140001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Fu, H.D.; Wang, Y.T.; Xie, J.X. Effect of Ag addition on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Cu-Cr alloy. Materials Science and Engineering A 2018, 726, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Z.; Bu, K.; Song, K.X.; Zhou, Y.J.; Huang, T.; Niu, L.Y.; Guo, H.W.; Du, Y.B. ; Kang. J.W. Influence of low-temperature annealing temperature on the evolution of the microstructure and mechanical properties of Cu-Cr-Ti-Si alloy strips. Materials Science and Engineering A 2020, 798, 140120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.Q.; Peng, L.J.; Huang, G.J.; Xie, H.F.; Mi, X.J.; Liu, X.H. Effects of Mg addition on the microstructure and softening resistance of Cu-Cr alloys. Materials Science and Engineering A 2020, 776, 139009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.M.; Zhu, D.G.; Tang, L.T.; Jiang, X.S.; Chen, S.; Peng, X.; Hu, C.F. Microstructure and properties of powder metallurgy Cu-1%Cr-0.65%Zr alloy prepared by hot pressing. Vacuum 2016, 131, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.Q.; Xu, C.; Yang, L.J.; Zhang, H.H.; Song, Z.L. Recent Advances in the Research of High-strength and High-conductivity CuCrZr alloy (in Chinese). Materials Reports 2018, 32, 453–460. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.T.; Hu, M.J.; Liu, W.Y.; Zhang, J.B. Study on Aging Kinetics of Cu-0.37Cr-0.046Sn Alloy Prepared by Antivacuum Melting. Hot Working Technology 2016, 45, 189–192. [Google Scholar]

- Sprouster, D.J.; Cunningham, W.S.; Halada, G.P.; Yan, H.F.; Pattammattel, A.; Huang, X.L.; Olds, D.; Tilton, M.; Chu, Y.S.; Dooryhee, E.; Manogharan, G.P.; Trelewicz. J.R. Dislocation microstructure and its influence on corrosion behavior in laser additively manufactured 316L stainless steel. Additive Manufacturing 2021, 47, 102263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.N.; Ma, A.L.; Zhang, L.M.; Zheng, Y.G. Crystallographic anisotropy of corrosion rate and surface faceting of polycrystalline 90Cu-10Ni in acidic NaCl solution. Materials & Design 2022, 215, 110429. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Gao, B.; Yang, Y.; Xu, M.N.; Li, X.F.; Li, C.; Pan, H.J.; Yang, J.R.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, X.K. ; Zhu. Y.T. Strain hardening behavior and microstructure evolution of gradient-structured Cu-Al alloys with low stack fault energy. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2022, 19, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, B.; Ma, D.; Allard, L.; Clarke, A.; Shyam, A. Crystallographic orientation-dependent strain hardening in a precipitation-strengthened Al-Cu alloy. Acta Materialia 2021, 205, 116577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Q.H.; Liu, J.; Wu, F.; Chen, H.M.; Xie, W.B.; Wang, H.; Yang, B. Precipitation behavior and strengthening effects of the Cu-0.42Cr-0.16Co alloy during aging treatment. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2023, 936, 168269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Yang, S.F.; Zhao, P.; Xie, G.L.; Wang, A.R.; Li, J.S. ; Liu. W. Solidification characteristics and precipitation behavior of the Cu-Cr-Nb alloys. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2023, 23, 882–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Peng, L.J.; Mi, X.J.; Zhao, G.; Huang, G.J.; Xie, H.F.; Zhang, W.J. Relationship between microstructure and properties of high-strength Cu-Ti-Cr alloys during aging. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2023, 942, 168865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.L.; Pang, Y.; Yi, J.; Lei, Q.; Li, Z.; Xiao, Z. Effects of pre-aging on microstructure and properties of Cu-Ni-Si alloys. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2023, 942, 169033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.X.; Hu, J.H.; Xin, Z.; Qin, L.X.; Jia, Y.L.; Jiang, Y.B. Microstructure and properties of Cu-Zn-Cr-Zr alloy treated by multistage thermo-mechanical treatment. Materials Science & Engineering A 2023, 870, 144679. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).