Submitted:

11 April 2023

Posted:

12 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

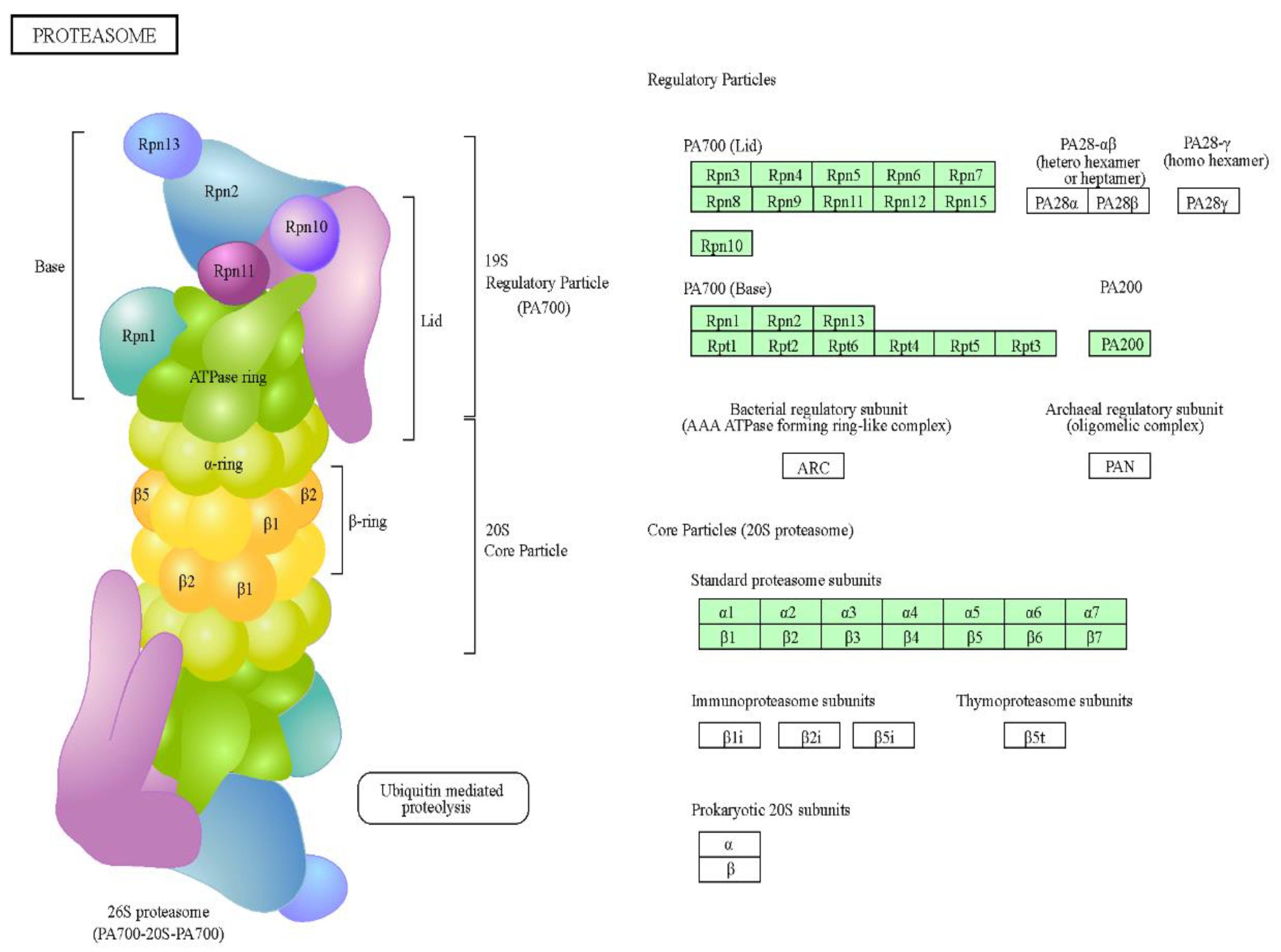

3.2. Genetic Information Processing

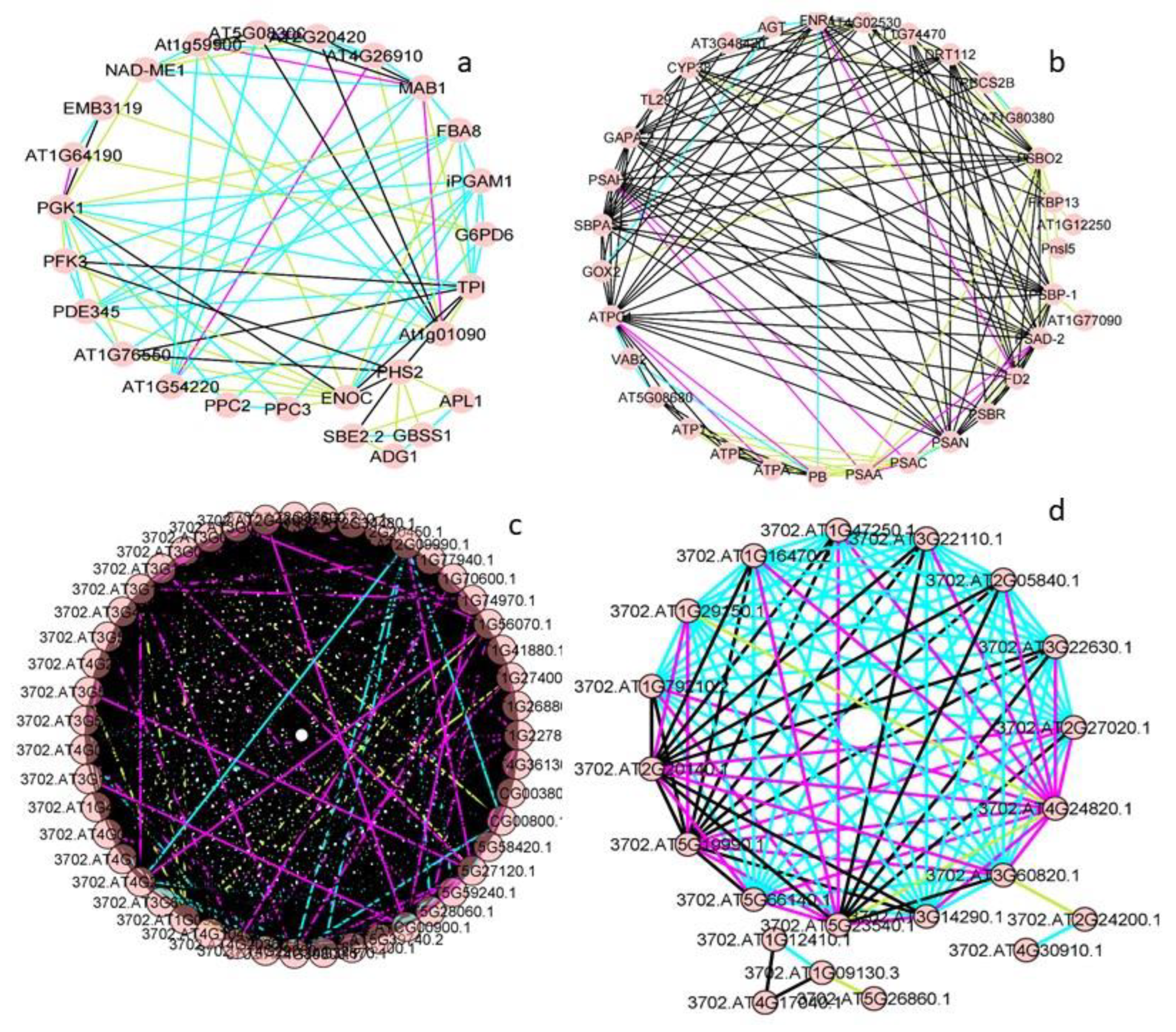

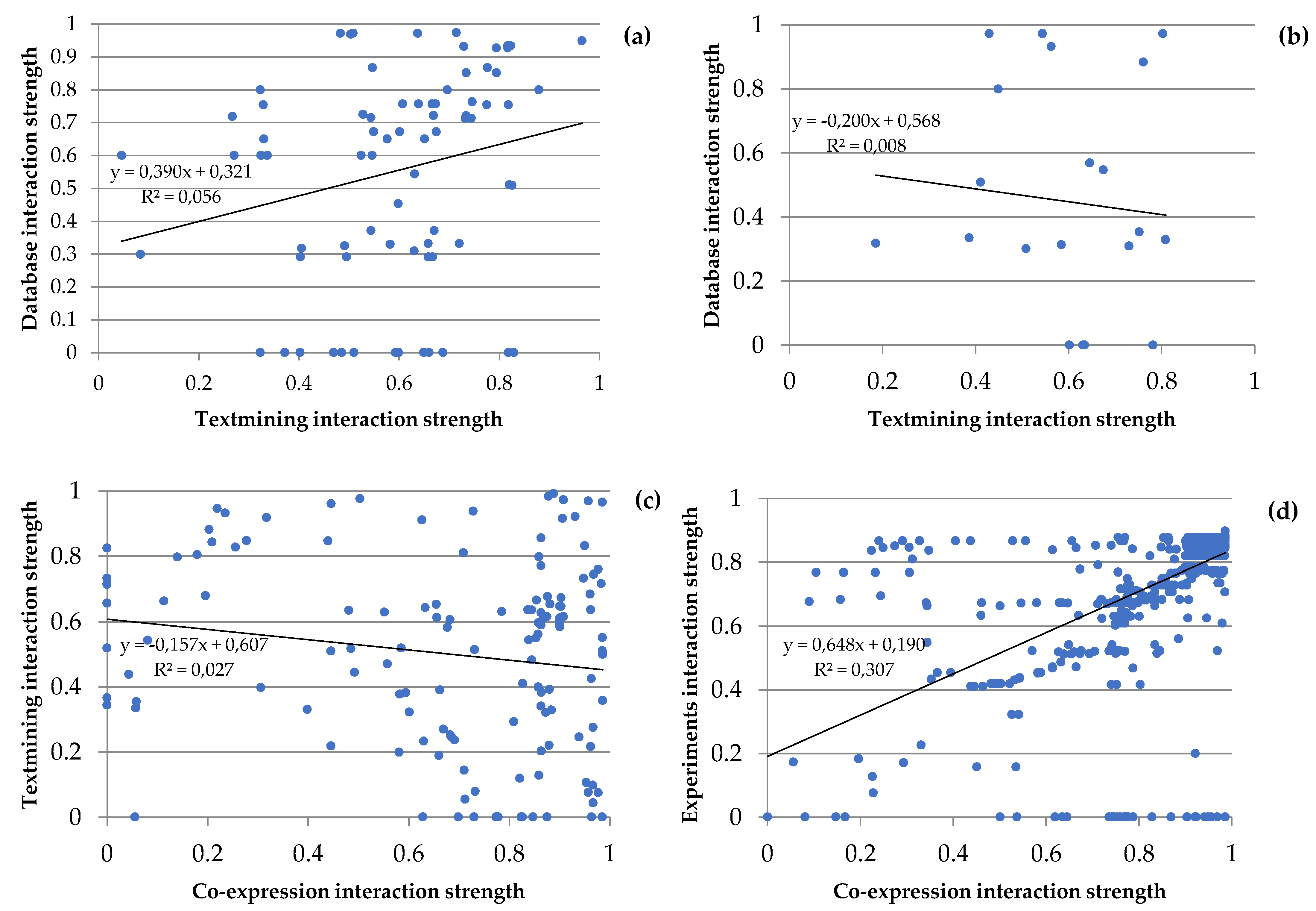

3.3. Protein-Protein Interactions

4. Materials and Methods

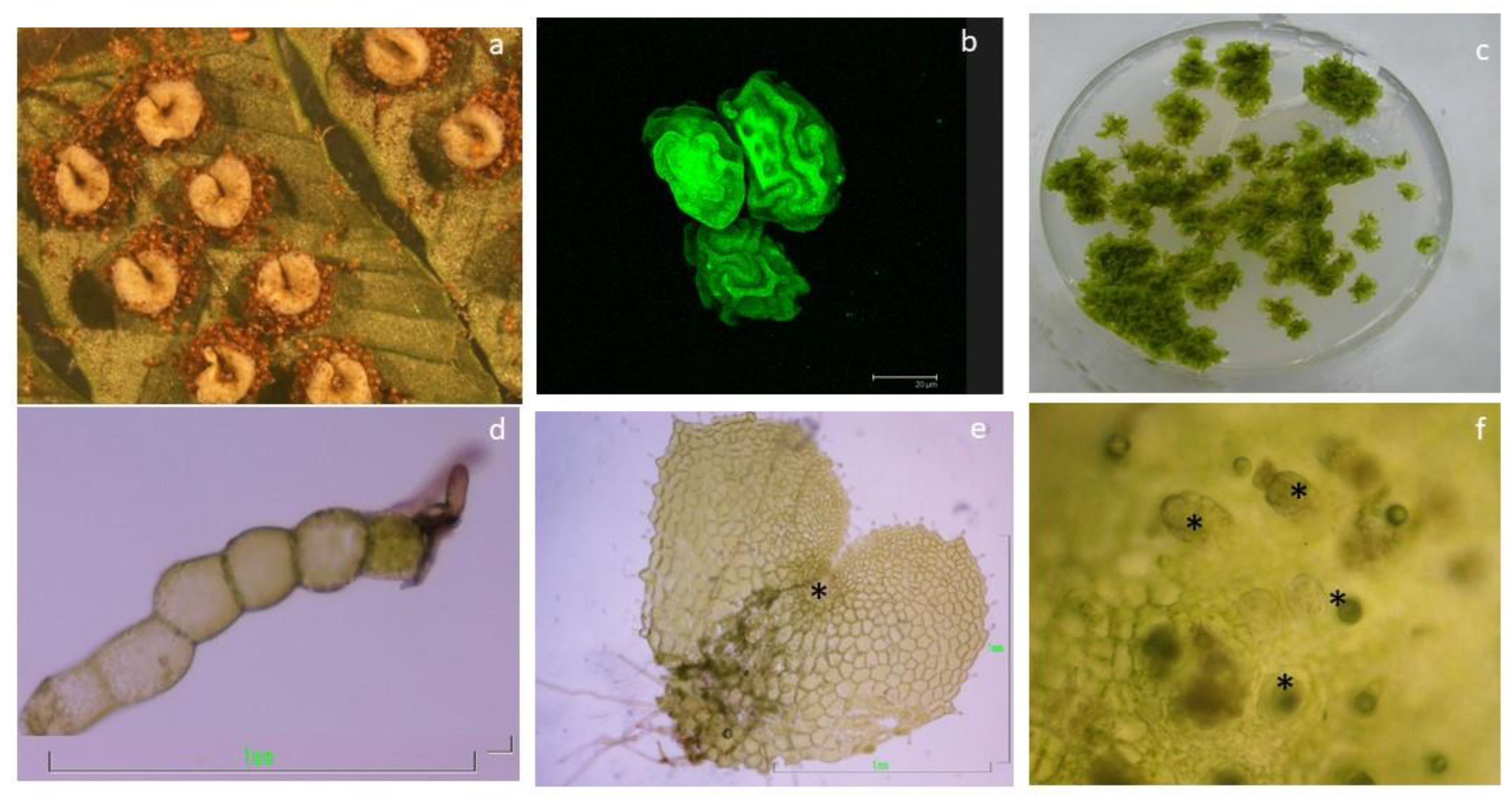

4.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

4.2. Protein Extraction, Separation, and In-Gel Digestion

4.3. Protein Identification, Verification, and Bioinformatic Downstream Analyses

4.4. Protein Analysis Using the STRINGPlatform

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aya, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Tanaka, J.; Ohyanagi, H.; Suzuki, T.; Yano, K.; Takano, T.; Yano, K.; Matsuoka, M. De novo transcriptome assembly of a fern, Lygodium japonicum, and a web resource database Ljtrans DB. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, e5. [CrossRef]

- Berrier, C.; Peyronnet, R.; Betton, J.M.; Ephritikhine, G.; Barbier-Brygoo, H.; Frachisse, J.M.; Ghazi, A. Channel characteristics of VDAC-3 from Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 459, 24–28. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Lee, L.Y.; Oltmanns, H.; Cao, H.; Veena; Cuperus, J.; Gelvin, S.B. IMPa-4, an Arabidopsis importin α isoform, is preferentially involved in agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Plant Cell. 2008, 20, 2661–2680. [CrossRef]

- Boldt, R.; Edner, C.; Kolukisaoglu, Ü.; Hagemann, M.; Weckwerth, W.; Wienkoop, S.; Morgenthal, K.; Bauwe, H. D-glycerate 3-kinase, the last unknown enzyme in the photorespiratory cycle in Arabidopsis, belongs to a novel kinase family. Plant Cell. 2005, 17, 2413–2420. [CrossRef]

- Bracher, A.; Sharma, A.; Starling-Windhof, A.; Hartl, F.U.; Hayer-Hartl, M. Degradation of potent rubisco inhibitor by selective sugar phosphatase. Nat. Plants. 2014, 112015, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A. J.; Heazlewood, J. L.; Ito, J.; Millar, A. H. Analysis of the Arabidopsis cytosolic ribosome proteome provides detailed insights into its components and their post-translational modification. Mol.Cell Proteomics. 2008, 7, 347–369. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Chiu, F.-Y.; Lin, Y.; Huang, W.-J.; Hsieh, P.-S.; Hsu, F.-L. Chemical constituents analysis and antidiabetic activity validation of four fern species from Taiwan. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 2497–2516. [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, F. C.; Davin, L. B.; Lewis, N. G. The Arabidopsis phenylalanine ammonia lyasegene family: kinetic characterization of the four PAL isoforms. Phytochemistry. 2004, 65, 1557–1564. [CrossRef]

- Condori-Apfata, J. A.; Batista-Silva, W.; Medeiros, D. B.; Vargas, J. R.; Valente, L. M. L.; Pérez-Díaz, J. L.; Fernie, A. Condori-Apfata, J. A.; Batista-Silva, W.; Medeiros, D. B.; Vargas, J. R.; Valente, L. M. L.; Pérez-Díaz, J. L.; Fernie, A. R,; Araújo, W. L.; Nunes-Nesi, A. Downregulation of the E2 subunit of 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase modulates plant growth by impacting carbon-nitrogen metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 2021, 62, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Cordle, A.; Irish, E.; Cheng, C.L. Gene expression associated with apogamy commitment in Ceratopteris richardii. Sex. Plant Reprod. 2012, 25, 293–304. [CrossRef]

- Crosara, K.T.B.; Moffa, E.B.; Xiao, Y.; Siqueira, W.L. Merging in-silico and in vitrosalivary protein complex partners using the STRING database: a tutorial. J. Proteomics. 2018, 171, 87–94. [CrossRef]

- Der, J.P.; Barker, M.S.; Wickett, N.J.; dePamphilis, C.W.; Wolf, P.G. De novo characterization of the gametophyte transcriptome in bracken fern, Pteridium aquilinum. BMC Genomics. 2011, 12, 99. [CrossRef]

- Dhir, B. Role of ferns in environmental cleanup. In: Current Advances in Fern Research; Fernández, H., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 517–531.

- Dixon, D.P.; Edwards, R. Roles for stress-inducible lambda glutathione transferases in flavonoid metabolism in plants as identified by ligand fishing. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 36322–36329. [CrossRef]

- Eeckhout, S.; Leroux, O.; Willats, W. G.; Popper, Z. A.; Viane, R. L. Comparative glycan profiling of Ceratopteris richardii 'C-fern' gametophytes and sporophytes links cell-wall composition to functional specialization. Ann Bot. 2014, 114, 1295–1307. [CrossRef]

- Ehlting, J.; Büttner, D.; Wang, Q.; Douglas, C.J.; Somssich, I.E.; Kombrink, E. Three 4-coumarate:coenzyme A ligases in Arabidopsis thaliana represent two evolutionarily divergent classes in angiosperms. Plant J. 1999, 19, 9–20. [CrossRef]

- Eudes, A.; Pollet, B.; Sibout, R.; Do, C.T.; Séguin, A.; Lapierre, C.; Jouanin, L. Evidence for a role of AtCAD 1 in lignification of elongating stems of Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2006,225, 23–39. [CrossRef]

- Fatland, B.L.; Ke; Anderson, J.; Mentzen, M.D.; Cui, W.I.; Wei; Allred, L.; Christy; Johnston, C.; Nikolau, J.L.; Wurtele, B.J.; Syrkin; LWC, E.; Biology; Physiol, M. Fatland, B.L.; Ke, J.; Anderson, M.D.; Mentzen, W.I.; Wei Cui, L.; Christy Allred, C.; Johnston, J.L.; Nikolau, B.J.; Syrkin Wurtele, E.; Biology LWC, M. Molecular characterization of a heteromeric ATP-citrate lyase that generates cytosolic acetyl-coenzyme A in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatland, B.L.; Nikolau, B.J.; Wurtele, E. S. Reverse genetic characterization of cytosolic acetyl-CoA generation by ATP-citrate lyase in Arabidopsis. PlantCell. 2005, 17, 182–203. [CrossRef]

- Femi-Adepoju, A.G.; Dada, A.O.; Otun, K.O.; Adepoju, A.O.; Fatoba, O. P. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using terrestrial fern (Gleichenia pectinata (Willd.) C. Presl.): characterization and antimicrobial studies. Heliyon. 2019, 5, e01543. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, H.; Grossmann, J.; Gagliardini, V.; Feito, I.; Rivera, A.; Rodríguez, L.; Quintanilla, L.G.; Quesada, V.; Cañal, M.J.; Grossniklaus, U. Sexual and apogamous species of woodferns show different protein and phytohormone profiles. Front. PlantSci. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, H.; Revilla, M.A. Fernández, H.; Revilla, M.A. In vitroculture of ornamental ferns. Plant Cell. Tissue Organ Cult. 2003, 73, 1–13.

- Ferrario-Méry, S.; Meyer, C.; Hodges, M. Chloroplast nitrite uptake is enhanced in Arabidopsis PII mutants. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 1061–1066. [CrossRef]

- Gargano, D.; Maple-Grødem, J.; Møller, S.G. In vivophosphorylation of FtsZ2 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochem. J. 2012, 446, 517–521. [CrossRef]

- Gaudet, P.; Livstone, M.S.; Lewis, S.E.; Thomas, P.D. Phylogenetic-based propagation of functional annotations within the gene ontology consortium. Brief. Bioinform. 2011, 12, 449–462. [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, J.; Fernández, H.; Chaubey, P. M.; Valdés, A. E.; Gagliardini, V.; Cañal, M. J.; Russo, G.; Grossniklaus, U. Proteogenomic analysis greatly expands the identification of proteins related to reproduction in the apogamous fern Dryopterisaffinis ssp. affinis. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 336. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Xiong, L.; Ishitani, M.; Zhu, J.K. An Arabidopsis mutation in translation elongation factor 2 causes superinduction of CBF/DREB1 transcription factor genes but blocks the induction of their downstream targets under low temperatures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002, 99, 7786–7791. [CrossRef]

- Haferkamp, I.; Hackstein, J.H.P.; Voncken, F.G.J.; Schmit, G.; Tjaden, J. Functional integration of mitochondrial and hydrogenosomal ADP/ATP carriers in the Escherichia coli membrane reveals different biochemical characteristics for plants, mammals and anaerobic chytrids. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002, 269, 3172–3181. [CrossRef]

- Haizel, T.; Merkle, T.; Pay, A.; Fejes, E.; Nagy, F. Characterization of proteins that interact with the GTP-bound form of the regulatory GTPase Ran in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 1997, 11, 93–103. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhou, Y.; Mawhinney, T. P.; Chen, B.; Kang, B. H.; Hauser, B. A.; Chen, S. Functionalcharacterization of Arabidopsis thaliana isopropylmalate dehydrogenases reveals their important roles in gametophyte development. New Phytol. 2011, 189, 160–175. [CrossRef]

- Howles, P.A.; Birch, R.J.; Collings, D.A.; Gebbie, L.K.; Hurley, U.A.; Hocart, C.H.; Arioli, T.; Williamson, R. E. A mutation in an Arabidopsis ribose 5-phosphate isomerase reduces cellulose synthesis and is rescued by exogenous uridine. Plant J. 2006, 48, 606–618. [CrossRef]

- Ishizaki, T.; Ohsumi, C.; Totsuka, K.; Igarashi, D. Analysis of glutamate homeostasis by overexpression of Fd-GOGAT gene in Arabidopsis thaliana. Amin. Acids. 2009,38, 943–950. [CrossRef]

- Ito, J.; Batth, T. S.; Petzold, C. J.; Redding-Johanson, A. M.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Verboom, R.; Meyer, E. H.; Millar, A. H.; Heazlewood, J. L. Analysis of the Arabidopsis cytosolic proteome highlights subcellular partitioning of central plant metabolism. J. Proteome Res. 2011, 10, 1571–1582. [CrossRef]

- Kieselbach, T.; Bystedt, M.; Hynds, P.; Robinson, C.; Schröder, W.P. A peroxidase homologue and novel plastocyanin located by proteomics to the Arabidopsis chloroplast thylakoid lumen. FEBS Lett. 2000, 480, 271–276. [CrossRef]

- Klee, H.J.; Muskopf, Y.M.; Gasser, C.S. Cloning of an Arabidopsis thalianagene encoding 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase: sequence analysis and manipulation to obtain glyphosate-tolerant plants. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1987,210, 437–442. [CrossRef]

- Knill, T.; Reichelt, M.; Paetz, C.; Gershenzon, J.; Binder, S. Arabidopsis thaliana encodes a bacterial-type heterodimeric isopropylmalate isomerase involved in both Leu biosynthesis and the Met chain elongation pathway of glucosinolate formation. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009, 71, 227–239. [CrossRef]

- Kraker, J. W. de; Luck, K.; Textor, S.; Tokuhisa, J. G.; Gershenzon, J. Two Arabidopsis genes (IPMS1 andIPMS2) encode isopropylmalate synthase, the branchpoint step in the biosynthesis of leucine. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143, 970–986. [CrossRef]

- Küchler, M.; Decker, S.; Hörmann, F.; Soll, J.; Heins, L. Protein import into chloroplasts involves redox-regulated proteins. EMBOJ. 2002, 21, 6136–6145. [CrossRef]

- Lambermon, M.H.L.; Fu, Y.; Kirk, D.A.W.; Dupasquier, M.; Filipowicz, W.; Lorković, Z.J. UBA1 and UBA2, two proteins that interact with UBP1, a multifunctional effector of pre-mRNA maturation in plants. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 4346–4357. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Chung, G.C.; Jang, J.Y.; Ahn, S.J.; Zwiazek, J.J. Overexpression of PIP2;5 aquaporin alleviates effects of low root temperature on cell hydraulic conductivity and growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2012, 159, 479–488. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, X.; Gong, P.; Xu, Q.; Yu, Q. B.; Guan, Y. Pooled CRISPR/Cas9 reveals redundant roles of plastidial phosphoglycerate kinases in carbon fixation and metabolism. Plant J. 2019,98, 1078-1089. [CrossRef]

- Lindén, P.; Keech, O.; Stenlund, H.; Gardeström, P.; Moritz, T. Reduced mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase activity has a strong effect on photorespiratory metabolism as revealed by 13C labelling. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 3123–3135. [CrossRef]

- Lintala, M.; Allahverdiyeva, Y.; Kidron, H.; Piippo, M.; Battchikova, N.; Suorsa, M.; Rintamäki, E.; Salminen, T.A.; Aro, E. M.; Mulo, P. Structural and functional characterization of ferredoxin-NADP+-oxidoreductase using knock-out mutants of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2007, 49, 1041–1052. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Last, R.L. A chloroplast thylakoid lumen protein is required for proper photosynthetic acclimation of plants under fluctuating light environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 114. [CrossRef]

- Lundin, B.; Hansson, M.; Schoefs, B.; Vener, A. V.; Spetea, C. The Arabidopsis PsbO2 protein regulates dephosphorylation and turnover of the photosystem II reaction centre D1 protein. Plant J. 2007, 49, 528–539. [CrossRef]

- Marasinghe, G.P.K.; Sander, I.M.; Bennett, B.; Periyannan, G.; Yang, K. W.; Makaroff, C.A.; Crowder, M. W. Structural studies on a mitochondrial glyoxalase II. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 40668–40675. [CrossRef]

- Mou, Z.; He, Y.; Dai, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, J. Deficiency in fatty acid synthase leads to premature cell death and dramatic alterations in plant morphology. Plant Cell. 2000, 12, 405–417. [CrossRef]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Plant Physiol. 1962, 473–497.

- Ojosnegros, S.; Alvarez, J. M.; Grossmann, J.; Gagliardini, V.; Quintanilla, L. G.; Grossniklaus, U.; Fernández, H. The shared proteome of the apomictic fern Dryopteris affinisssp. affinisand its sexual relativeDryopteris oreades. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14027. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, M.; Li, X.; Zhao, S.; Pu, H.; Shen, J.; Adam, Z.; Clausen, T.; Zhang, L. The crystal structure of Deg9 reveals a novel octameric-type HtrA protease. Nat. Plants. 2017, 3, 973–982. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, L.N.; Marineo, S.; Mandalà, S.; Davids, F.; Sewell, B.T.; Ingle, R.A. The missing link in plant histidine biosynthesis: Arabidopsis myoinositol monophosphatase-like2 encodes a functional histidinol-phosphate phosphatase. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152, 1186–1196. [CrossRef]

- Pracharoenwattana, I.; Cornah, J.E.; Smith, S.M. Arabidopsis peroxisomal citrate synthase is required for fatty acid respiration and seed germination. Plant Cell. 2005, 17, 2037–2048. [CrossRef]

- Rathinasabapathi, B. Ferns represent an untapped biodiversity for improving crops for environmental stress tolerance. New Phytol. 2006, 172, 385–390. [CrossRef]

- Rautengarten, C.; Ebert, B.; Herter, T.; Petzold, C.J.; Ishii, T.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Usadel, B.; Scheller, H.V. The interconversion of UDP-arabinopyranose and UDP-arabinofuranose is indispensable for plant development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2011, 23, 1373–1390. [CrossRef]

- Rivera, A.; Cañal, M. J.; Grossniklaus, U.; Fernández, H. The gametophyte of fern: born to reproduce. In: Current Advances in Fern Research. Fernández, H., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: New York, 2018, pp. 3–19.

- Rosenquist, M.; Alsterfjord, M.; Larsson, C.; Sommarin, M. Data mining the Arabidopsis genome reveals fifteen 14-3-3 genes. expression is demonstrated for two out of five novel genes. Plant Physiol. 2001, 127, 142–149. [CrossRef]

- Salmi, M. L.; Bushart, T. J. Cellular, molecular, and genetic changes during the development of Ceratopteris richardii gametophytes. In: Working with ferns. Issues and applications; Fernández, H., Kumar, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: New York, 2010; pp. 11–24.

- Salmi, M.L.; Bushart, T.; Stout, S.; Roux, S. Profile and analysis of gene expression changes during early development in germinating spores of Ceratopteris richardii. Plant Physiol. 2005, 138, 1734–1745. [CrossRef]

- Salmi, M.L.; Morris, K.E.; Roux, S.J.; Porterfield, D.M. Nitric oxide and CGMP signaling in calcium-dependent development of cell polarity in Ceratopteris richardii. Plant Physiol. 2007, 144, 94–104. [CrossRef]

- Sanda, S.; Leustek, T.; Theisen, M.J.; Garavito, R.M.; Benning, C. Recombinant Arabidopsis SQD1 converts UDP-glucose and sulfite to the sulfolipid head group precursor UDP-sulfoquinovose in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 3941–3946. [CrossRef]

- Scranton, M.A.; Yee, A.; Park, S.Y.; Walling, L. L. Plant leucine aminopeptidases moonlight as molecular chaperones to alleviate stress-induced damage. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 18408–18417. [CrossRef]

- Seung, D.; Soyk, S.; Coiro, M.; Maier, B.A.; Eicke, S.; Zeeman, S. C. PROTEIN TARGETING TO STARCH is required for localising GRANULE-BOUND STARCH SYNTHASE to starch granules and for normal amylose synthesis in Arabidopsis. PLOS Biol. 2015, 13, e1002080. [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Li, C.; Tarczynski, M.C. Shen, B.; Li, C.; Tarczynski, M.C. High free-methionine and decreased lignin content result from a mutation in the Arabidopsis S-adenosyl-L-methionine synthetase 3 gene. Plant J. 2002, 29, 371–380.

- Shi, X.; Hanson, M.R.; Bentolila, S. Two RNA recognition motif-containing proteins are plant mitochondrial editing factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 3814–3825. [CrossRef]

- Shirley, B.W.; Hanley, S.; Goodman, H. M. Effects of ionizing radiation on a plant genome: analysis of two Arabidopsis transparent testa mutations. Plant Cell. 1992, 4, 333–347. [CrossRef]

- Skalitzky, C.A.; Martin, J.R.; Harwood, J.H.; Beirne, J.J.; Adamczyk, B.J.; Heck, G.R.; Cline, K.; Fernandez, D. E. Plastids contain a second Sec translocase system with essential functions. Plant Physiol. 2011, 155, 354–369. [CrossRef]

- Ståhl, A.; Moberg, P.; Ytterberg, J.; Panfilov, O.; Von Löwenhielm, H. B.; Nilsson, F.; Glaser, E. Isolation and identification of a novel mitochondrial metalloprotease (PreP) that degrades targeting presequences in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 41931–41939. [CrossRef]

- Stanislas, T.; Hüser, A.; Barbosa, I.C.R.; Kiefer, C.S.; Brackmann, K.; Pietra, S.; Gustavsson, A.; Zourelidou, M.; Schwechheimer, C.; Grebe, M. Arabidopsis D6PK is a lipid domain-dependent mediator of root epidermal planar polarity. Nat. Plants. 2015,1, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Suo, J.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, S.; Cao, J.; Liu, G.; Wei, X.; Wang, T.; Yang, C.; Dai, S. Cytological and proteomic analyses of Osmunda cinnamomea germinating spores reveal characteristics of fern spore germination and rhizoid tip growth. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2015, 14, 2510–2534. [CrossRef]

- Takagi, D.; Amako, K.; Hashiguchi, M.; Fukaki, H.; Ishizaki, K.; Goh, T.; Fukao, Y.; Sano, R.; Kurata, T.; Demura, T.; Sawa, S.; Miyake, C. Chloroplastic ATP synthase builds up a proton motive force preventing production of reactive oxygen species in photosystem I. Plant J. 2017, 91, 306–324. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Sasaki, Y.; Ida, S.; Morikawa, H. Nitrite reductase gene enrichment improves assimilation of NO(2) in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001, 126, 731–741. [CrossRef]

- Tomaz, T.; Bagard, M.; Pracharoenwattana, I.; Lindén, P.; Lee, C.P.; Carroll, A.J.; Ströher, E.; Smith, S.M.; Gardeström, P.; Millar, A.H. Mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase lowers leaf respiration and alters photorespiration and plant growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154, 1143–1157. [CrossRef]

- Tronconi, M.A.; Fahnenstich, H.; Gerrard Weehler, M.C.; Andreo, C. S.; Flügge, U.I.; Drincovich, M.F.; Maurino, V.G. Arabidopsis NAD-malic enzyme functions as a homodimer and heterodimer and has a major impact on nocturnal metabolism. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 1540. [CrossRef]

- Valledor, L.; Menéndez, V.; Canal, M.J.; Revilla, A.; Fernández, H. Proteomic approaches to sexual development mediated by antheridiogen in the fern Blechnum spicant L. Proteomics 2014, 14. [CrossRef]

- Varotto, C.; Pesaresi, P.; Meurer, J.; Oelmüller, R.; Steiner-Lange, S.; Salamini, F.; Leister, D. Disruptionof the Arabidopsis photosystem I gene psaE1 affects photosynthesis and impairs growth. Plant J. 2000, 22, 115–124. [CrossRef]

- Wada, M. The fern as a model system to study photomorphogenesis. J. Plant Res. 2007, 120, 3–16. [CrossRef]

- Wakao, S.; Benning, C. Genome-wide analysis of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenases in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2005, 41, 243–256. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Yang, L.; Han, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, L.; Xiang, B.; Zhu, Y.; Bai, Y.; Wang, Y. Overexpression of AtAGT1 promoted root growth and development during seedling establishment. Plant Cell Rep. 2019, 38, 1165–1180. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Zhang, H.; Shi, L.; Cao, F.; Guo, L.; Xie, Y.; Wang, T.; Yan, X.; Dai, S. Desiccation tolerance mechanism in resurrection fern-ally Selaginella tamariscina revealed by physiological and proteomic analysis. J. Proteome Res. 2010, 9, 6561–6577. [CrossRef]

- Wyder, S.; Rivera, A.; Valdés, A.E.; Cañal, M. J.; Gagliardini, V.; Fernández, H.; Grossniklaus, U. Plant physiology and biochemistry differential gene expression profiling of one- and two-dimensional apogamous gametophytes of the fern Dryopteris affinis ssp. affinis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 148, 302–311. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zang, X.; Yuan, S.; Bat-Erdene, U.; Nguyen, C.; Gan, J.; Zhou, J.; Jacobsen, S. E.; Tang, Y.Resistance-gene-directed discovery of a natural-product herbicide with a new mode of action. Nature. 2018, 559, 415–418. [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Abdel-Ghany, S. E.; Anderson, T. D.; Pilon-Smits, E. A.; Pilon, M. CpSufE activates the cysteine desulfurase CpNifS for chloroplastic Fe-S cluster formation. J Biol Chem. 2006, 281, 8958–8969. [CrossRef]

- Žárský, V.; Cvrčková, F.; Bischoff, F.; Palme, K. At-GDI1 from Arabidopsis thalianaencodes a Rab-specific GDP dissociation inhibitor that complements the Sec19 mutation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1997, 403, 303–308. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Xu, Y.; Li, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, D.; Mao, Z.; Guo, S.; Yang, C.; Weng, Y.; Chong, K. The cyclophilin CYP20-2 modulates the conformation of BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT1, which binds the promoter of FLOWERING LOCUS D to regulate flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013, 25, 2504–2521. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, K.; Sandoval, F. J.; Santiago, K.; Roje, S. One-carbon metabolism in plants: characterization of a plastid serine hydroxymethyltransferase. Biochem. J. 2010, 430, 97–105. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Swart, C.; Alseekh, S.; Scossa, F.; Jiang, L.; Obata, T.; Graf, A.; Fernie, A. R. The extra-pathway interactome of the TCA cycle: expected and unexpected metabolic interactions. Plant Physiol. 2018, 177, 966–979. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Assmann, S.M. The glycolytic enzyme, phosphoglycerate mutase, has critical roles in stomatal movement, vegetative growth, and pollen production in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 5179. [CrossRef]

| Category | Accession Number | UniProtKB/ Swiss-Prot |

Gene Name | Protein Name | MW (kDa) | Amino Acids |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrates | 58787-330_2_ORF2 | Q94AA4 | PFK3 | Phosphofructokinase 3 | 53 | 489 |

| Carbohydrates | 135690-210_1_ORF2 | Q9ZU52 | PDE345 | Pigment defective 345 | 42 | 391 |

| Carbohydrates | tr|A9NMQ0|A9NMQ0_PICSI | Q9LF98 | FBA8 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase 8 | 38 | 358 |

| Carbohydrates | 38153-411_5_ORF2 | Q38799 | MAB1 | Macci-bou | 39 | 363 |

| Carbohydrates | 83096-276_3_ORF2 | Q5GM68 | PPC2 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase 2 | 109 | 963 |

| Carbohydrates | 54280-344_1_ORF1 | Q84VW9 | PPC3 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase 3 | 110 | 968 |

| Carbohydrates | 113756-233_2_ORF1 | Q9SIU0 | NAD-ME1 | NAD-dependent malic enzyme 1 | 69 | 623 |

| Carbohydrates | 102811-246_6_ORF2 | O04499 | iPGAM1 | 2,3-biphosphoglycerate-independent phosphoglycerate mutase 1 | 60 | 557 |

| Carbohydrates | 70011-302_2_ORF1 | O82662 | AT2G20420 | - | 45 | 421 |

| Carbohydrates | 8279-816_3_ORF2 | P68209 | AT5G08300 | - | 36 | 347 |

| Carbohydrates | 222487-119_2_ORF2 | P93819 | c-NAD-MDH1 | Cytosolic-NAD-dependent malate dehydrogenase 1 | 35 | 332 |

| Carbohydrates | 156827-185_4_ORF1 | Q9SH69 | PGD1 | 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase 1 | 53 | 487 |

| Carbohydrates | 12493-682_6_ORF2 | Q9FJI5 | G6PD6 | Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase 6 | 59 | 515 |

| Carbohydrates | 20760-547_4_ORF1 | Q9LD57 | PGK1 | Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | 50 | 481 |

| Carbohydrates | 69882-302_6_ORF2 | Q9LZS3 | SBE2.2 | Starch branching enzyme 2.2 | 92 | 805 |

| Carbohydrates | tr|Q5PYJ7|Q5PYJ7_9MONI | Q9MAQ0 | GBSS1 | Granule bound starch synthase 1 | 66 | 610 |

| Carbohydrates | tr|A9SGH8|A9SGH8_PHYPA | P55228 | ADG1 | ADP glucose pyrophosphorylase 1 | 56 | 520 |

| Carbohydrates | 181563-155_3_ORF2 | P55229 | APL1 | ADP glucose pyrophosphorylase large subunit 1 | 57 | 522 |

| Carbohydrates | tr|D7MQA6|D7MQA6_ARALL | Q9LUE6 | RGP4 | Reversibly glycosylated polypeptide 4 | 41 | 364 |

| Carbohydrates | 162660-176_6_ORF1 | P83291 | AT5G20080 | - | 35 | 328 |

| Lipids | 20213-554_2_ORF1 | Q9SLA8 | MOD1 | Mosaic death 1 | 41 | 390 |

| Lipids | 387953-27_4_ORF1 | Q9SGY2 | ACLA-1 | ATP-citrate lyase A-1 | 49 | 443 |

| Category | Accession Number |

UniProtKB/ Swiss-Prot |

Gene Name | Protein Name | MW (kDa) |

Amino Acids |

| Lipids | 211149-128_1_ORF1 | Q9LXS6 | CSY2 | Citrate synthase 2 | 56 | 514 |

| Amino acids | 47558-369_4_ORF2 | P46643 | ASP1 | Aspartate aminotransferase 1 | 47 | 430 |

| Amino acids | 72506-296_4_ORF1 | Q94AR8 | IIL1 | Isopropyl malate isomerase large subunit 1 | 55 | 509 |

| Amino acids | 125905-219_3_ORF2 | Q9ZNZ7 | GLU1 | Glutamate synthase 1 | 179 | 1,648 |

| Amino acids | 393073-25_4_ORF2 | Q94JQ3 | SHM3 | Serine hydroxymethyltransferase 3 | 57 | 529 |

| Amino acids | tr|D8RLH8|D8RLH8_SELML | Q9C5U8 | HDH | Histidinol dehydrogenase | 50 | 466 |

| Amino acids | 294436-71_4_ORF2 | Q9LUT2 | MTO3 | Methionine over-accumulator 3 | 42 | 393 |

| Nucleotides | 2121-1366_3_ORF2 | Q9SF85 | ADK1 | Adenosine kinase 1 | 37 | 344 |

| Nucleotides | 59309-329_5_ORF1 | Q96529 | ADSS | Adenylosuccinate synthase | 52 | 490 |

| Nucleotides | 152024-193_3_ORF2 | Q9S726 | EMB3119 | Embryo defective 3119 | 29 | 276 |

| Energy | 164104-175_1_ORF1 | Q9FKW6 | FNR1 | Ferredoxin-NADP(+)-oxidoreductase 1 | 40 | 360 |

| Energy | sp|Q7SIB8|PLAS_DRYCA | P42699 | DRT112 | DNA-damage-repair/toleration protein 112 | 16 | 167 |

| Energy | 154679-189_1_ORF2 | Q9S841 | PSBO2 | Photosystem II subunit O-2 | 35 | 331 |

| Energy | 218625-122_1_ORF2 | O22773 | MPH2 | Maintenance of photosystem II under high light 2 | 23 | 216 |

| Energy | 6036-926_2_ORF1 | Q9ASS6 | Pnsl5 | Photosynthetic NDH subcomplex l 5 | 28 | 259 |

| Energy | 250817-99_2_ORF2 | Q94K71 | AT3G48420 | - | 34 | 319 |

| Energy | tr|A9RDI1|A9RDI1_PHYPA | Q944I4 | GLYK | Glycerate kinase | 51 | 456 |

| Energy | 297118-70_2_ORF2 | Q56YA5 | AGT | Alanine:glyoxylate aminotransferase | 44 | 401 |

| Energy | 33137-439_6_ORF2 | O48917 | SQD1 | Sulfoquinovosyldiacylglycerol 1 | 53 | 477 |

| Energy | 227095-115_1_ORF2 | Q84W65 | CPSUFE | Chloroplast sulfur E | 40 | 371 |

| Energy | 311596-62_2_ORF2 | Q9ZST4 | GLB1 | GLNB1 homolog | 21 | 196 |

| Energy | 318906-58_1_ORF1 | Q39161 | NIR1 | Nitrite reductase 1 | 65 | 586 |

| Secondary compounds | 156331-186_3_ORF2 | P41088 | TT5 | Transparent testa 5 | 26 | 246 |

| Secondary compounds | 230420-113_2_ORF2 | P34802 | GGPS1 | Geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase 1 | 40 | 371 |

| Secondary compounds | 85783-271_1_ORF2 | Q9T030 | PCBER1 | Phenylcoumaran benzylic ether reductase 1 | 34 | 308 |

| Category | Accession Number |

UniProtKB/ Swiss-Prot |

Gene Name | Protein Name | MW (kDa) |

Amino Acids |

| Secondary compounds | 153413-190_1_ORF2 | P42734 | CAD9 | Cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase 9 | 38 | 360 |

| Secondary compounds | 156554-185_2_ORF1 | Q9S777 | 4CL3 | 4-coumarate:coA ligase 3 | 61 | 561 |

| Secondary compounds | 223603-118_1_ORF1 | P05466 | AT2G45300 | - | 55 | 520 |

| Oxido -reduction |

133847-212_2_ORF2 | Q9SID3 | GLX2-5 | Glyoxalase 2-5 | 35 | 324 |

| Oxido -reduction |

tr|E1ZRS4|E1ZRS4_CHLVA | Q9ZP06 | mMDH1 | Mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase 1 | 35 | 341 |

| Oxido -reduction |

34437-432_2_ORF1 | Q9M2W2 | GSTL2 | Glutathione transferase lambda 2 | 33 | 292 |

| Oxido -reduction |

115571-230_4_ORF1 | Q9LZ06 | GSTL3 | Glutathione transferase L3 | 27 | 235 |

| Transcription | tr|A2X6N1|A2X6N1_ORYSI | Q96300 | GRF7 | General regulatory factor 7 | 29 | 265 |

| Transcription | 287872-75_1_ORF1 | Q9C5W6 | GRF12 | General regulatory factor 12 | 30 | 268 |

| Translation | 209284-130_2_ORF2 | Q9FNR1 | RBGA7 | MA-binding glycine-rich protein A7 | 29 | 309 |

| Translation | 293356-72_1_ORF1 | Q9LR72 | AT1G03510 | - | 47 | 429 |

| Translation | 26795-487_6_ORF2 | Q0WW84 | RBP47B | MA-binding protein 47B | 48 | 435 |

| Translation | 20230-554_5_ORF2 | Q9LES2 | UBA2A | UBP1-associated protein 2A | 51 | 478 |

| Translation | 174433-162_1_ORF1 | Q9ASR1 | LOS1 | Low expression of osmotically responsive genes 1 | 93 | 843 |

| Folding | 26640-489_1_ORF2 | Q9M1C2 | GROES | - | 15 | 138 |

| Folding | 189606-147_1_ORF2 | Q9SR70 | AT3G10060 | - | 24 | 230 |

| Folding | 149253-199_6_ORF2 | O22870 | AT2G43560 | - | 23 | 223 |

| Folding | 2524-1285_6_ORF2 | Q9SKQ0 | AT2G21130 | - | 18 | 174 |

| Transport | 19573-562_5_ORF2 | Q9SYI0 | AGY1 | Albino or glassy yellow 1 | 117 | 1,042 |

| Transport | 248569-101_3_ORF1 | P92985 | RANBP1 | RAN binding protein 1 | 24 | 219 |

| Transport | 146969-201_2_ORF1 | F4JL11 | IMPA-2 | Importin alpha isoform 2 | 58 | 535 |

| Transport | 151836-193_1_ORF2 | P40941 | AAC2 | ADP/ATP carrier 2 | 41 | 385 |

| Category | Accession Number |

UniProtKB/ Swiss-Prot |

Gene Name | Protein Name | MW (kDa) |

Amino Acids |

| Transport | 161087-178_2_ORF2 | Q8H0U5 | Tic62 | Translocon at the inner envelope membrane of chloroplasts 62 | 68 | 641 |

| Transport | 82340-277_1_ORF2 | Q39196 | PIP1;4 | Plasma membrane intrinsic protein 1;4 | 30 | 287 |

| Transport | 154825-188_3_ORF2 | Q9SMX3 | VDAC3 | Voltage dependent anion channel 3 | 29 | 274 |

| Transport | 272341-85_2_ORF2 | Q94A40 | alpha1-COP | Alpha1 coat protein | 136 | 1,216 |

| Transport | 29489-466_3_ORF1 | Q0WW26 | gamma2-COP | Gamma2 coat protein | 98 | 886 |

| Transport | 38639-409_2_ORF3 | Q93Y22 | AT5G05010 | - | 57 | 527 |

| Transport | 43675-385_1_ORF2 | Q67YI9 | EPS2 | Epsin2 | 95 | 895 |

| Transport | 68824-304_5_ORF2 | Q9LQ55 | DL3 | Dynamin-like 3 | 100 | 920 |

| Transport | - | F4J3Q8 | GET3B | Guided entry of tail-anchored proteins 3B | 47 | 433 |

| Transport | 3434-1154_1_ORF2 | Q96254 | GDI1 | Guanosine nucleotide diphosphate dissociation inhibitor 1 | 49 | 445 |

| Degradation | 141778-205_4_ORF2 | Q8L770 | AT1G09130 | - | 40 | 370 |

| Degradation | 172993-163_5_ORF1 | Q9XJ36 | CLP2 | CLP protease proteolytic subunit 2 | 31 | 279 |

| Degradation | 72587-296_2_ORF2 | Q8LB10 | CLPR4 | CLP protease R subunit 4 | 33 | 305 |

| Degradation | 17420-593_1_ORF2 | P93655 | LON1 | LON protease 1 | 109 | 985 |

| Degradation | tr|A9SF86|A9SF86_PHYPA | Q9LJL3 | PREP1 | Presequence protease 1 | 121 | 1,080 |

| Degradation | 186732-150_2_ORF2 | Q9FL12 | DEG9 | Degradation of periplasmic proteins 9 | 65 | 592 |

| Degradation | 170504-166_2_ORF2 | P30184 | LAP1 | Leucyl aminopeptidase 1 | 54 | 520 |

| Degradation | 170504-166_2_ORF2 | Q944P7 | LAP3 | Leucyl aminopeptidase 3 | 61 | 581 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).