1. Introduction

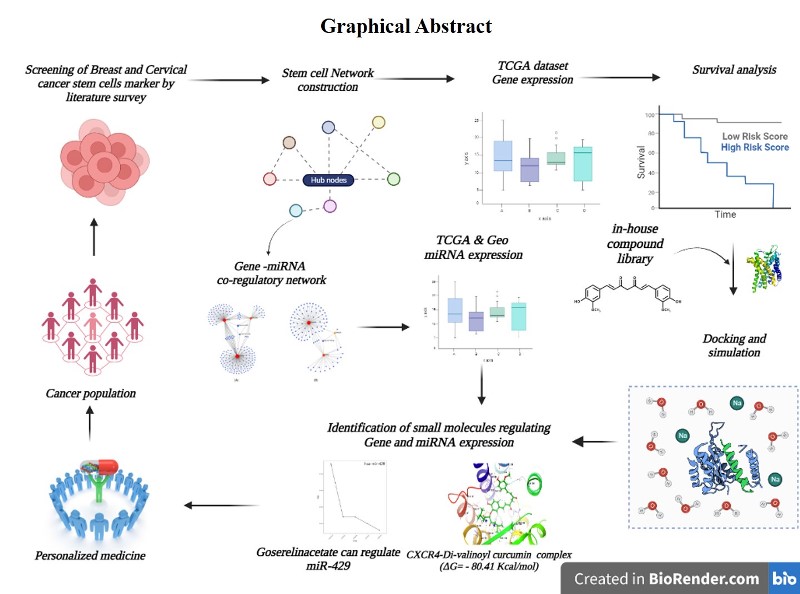

Gynaecological cancers are significant causes of morbidity and mortality among women worldwide 1. Even though a lot of advancements in therapies has been happening continuously, cancer is still one of the deadliest diseases. Drug resistance is one of the major problems in treatment of cancer. Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are majorly responsible for drug resistance 2. Self-renewal is an unique properties of stem cells that makes them immortal and certain transcription factors help stem cells to maintain their stemness like ALDH1,CD24,CD133,CD49f and CK17. Cancer stem cells lead to uncontrolled proliferation of cells3 and also admit quiescence 4 that can invade beyond normal tissue boundaries, metastasize to distant organs, and increases the rate of relapse5. Cancer stem cells, identified in most types of cancer, contribute to tumor resistance, expansion, metastasis, and recurrence after treatment2. CSCs are sub-population tumor cells creating a progeny of cells constituting the bulk of tumors. Because CSCs are difficult to identify, there is a need to identify stem cell markers. In this study, we selected the two most common types of gynecological cancers affecting women worldwide; breast cancer, and cervical cancer to analyze the stem cell markers, and target the most significant stem cell marker by novel plant-based metabolites and their derivatives like hydroxyl-piperloungumines, Coumaperine, annomontine, curcumin derivatives and 6,6'-Dihydroxythiobinupharidine (DTBN)6–10.

Cancer of the uterine cervix is ranked 4th among cancer in women in the world, with estimated 604,000 newly registered cases and 342,000 deaths in the year 202011. India disproportionately shares more than a quarter of the global cervical cancer burden. The etiology of cervical cancer stems from already existing non-invasive, pre-malignant lesions, also referred as, squamous intraepithelial lesions (SILs), or cervical intraepithelial lesions (CINs). Persistent infections linked to high risk subtypes of Human Papillomaviruses (HPVs) are the causative agents for cervical cancer12. However, HPV infection itself is not sufficient to induce malignant changes and there are so many other factors which play a crucial role in cervical cancer development. Studies revealed that there is a latent period between infection and invasive cancer, and this phenomenon provides a crucial window for cancer control. Therefore, it is necessary to screen out specific biomarker(s) which can track the progression of disease. Though HPV vaccines are currently available, but their limitation is that they do not protect against all subtypes of HPVs13,14. Early detection as well as attenuation of cervical cancer progression therefore requires additional highly specific biomarkers besides HPV and HPV vaccines. In cervical cancer, cancer stem cells are known to play crucial role in chemoresistance and is considered to be a better therapeutic target. Promising therapeutic strategies targeting on different cancer stem cells markers eg, ALDH1, CD24, CD133, CD49f, CK17 and signaling pathways are needed to be developed.

The most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide is breast cancer in females with around 2.3 million new cancer cases (11.7%) and deaths around 6.9%1,11,13. Incidence and mortality of breast cancer is increasing globally. Conventional approach for breast cancer is surgery followed by radiotherapy and chemotherapy which is continuously improving. Despite all this, treatment fails in 30-40% of the cases. Relapse and metastasis of the disease is because of breast cancer stem cells (BCSCs)15. BCSCs are a small population that is resilient to standard therapies and treatments. They re-enter the proliferation phase which leads to recurrence and metastasis of the disease16.

In this study, we analyzed the topmost markers of CSCs and BSCs & identified its associated microRNAs and pathway analysis of topmost hub genes, SOX2 in the case of cervical cancer and CXCR4 in the case of breast cancer by bioinformatic analysis and their potential targeting using natural compound derivates.

A thorogh understanding of the stemness markers of CSCs and BCSCs will provide new concepts for treatment of cervical and breast cancer and will also provide targets for therapeutic drugs. Combination of therapeutic drugs (to target stem cell markers) and chemotherapy drugs might be helpful in eliminating cervical and breast cancer, also reducing recurrence, and metastasis of the disease thereby improving the overall survival of the patients.

2. Results

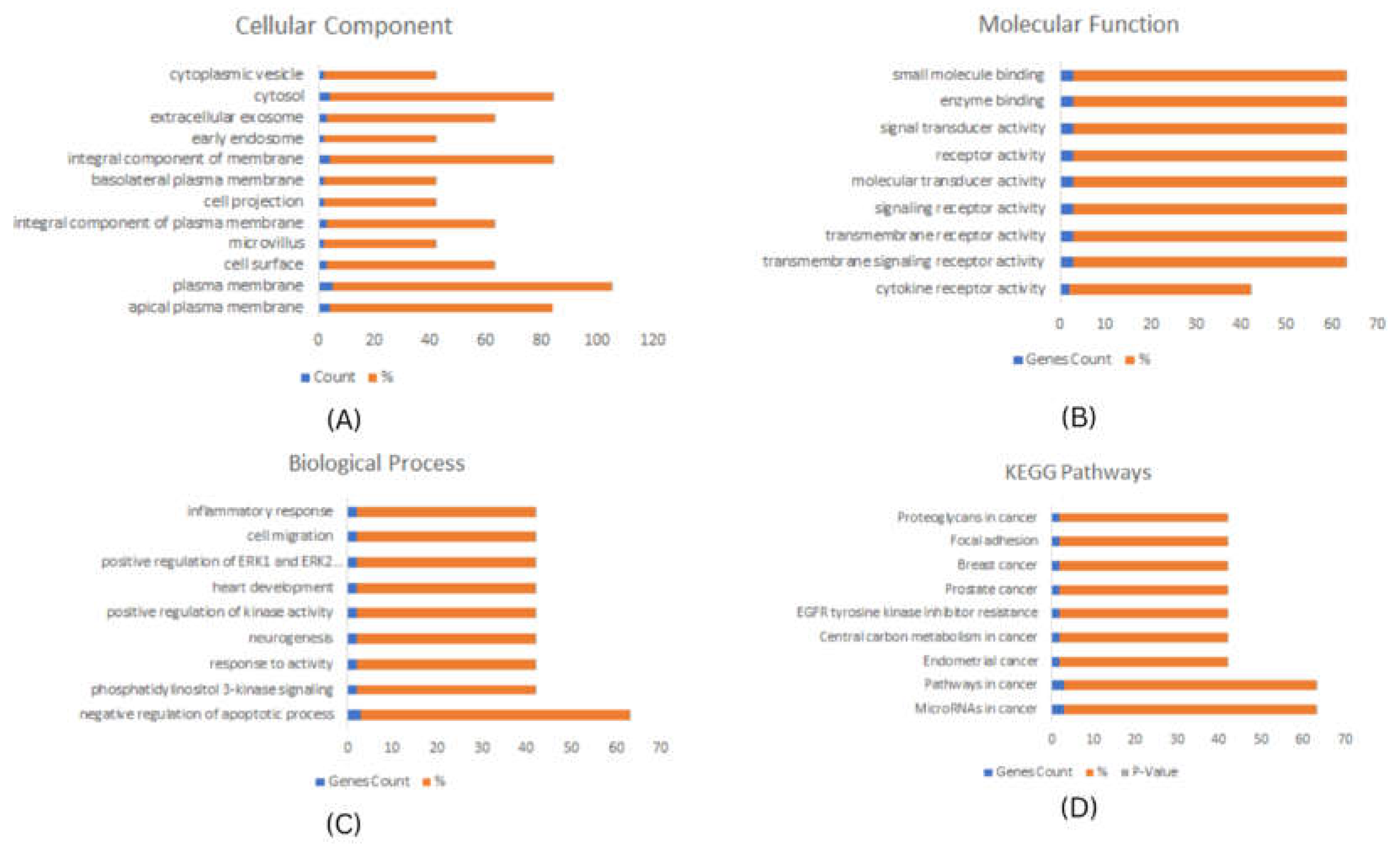

Enrichment Analysis using DAVID and KEGG

To investigate the potential function of the predicted hub genes, DAVID tool was used to perform Gene Ontology and encrichment analysis18. The top significantly enriched biological items for cellular component (CC), biological process (BP), and molecular functions (MF) were identified and plotted. A p-value < 0.01 was considered statistically significant.

KEGG

19 pathway analysis revealed that the identified stem cell markers were significantly enriched in proteoglycans in cancer, signaling pathways regulating pluripotency of stem cells, pathways in breast cancer, and prostate cancer, microRNA in cancer, pathways in cancer, and mTOR signaling pathways, these pathways are well established to play a role in various cancer associated functions such as cellular proliferation, apoptosis and invasion. (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

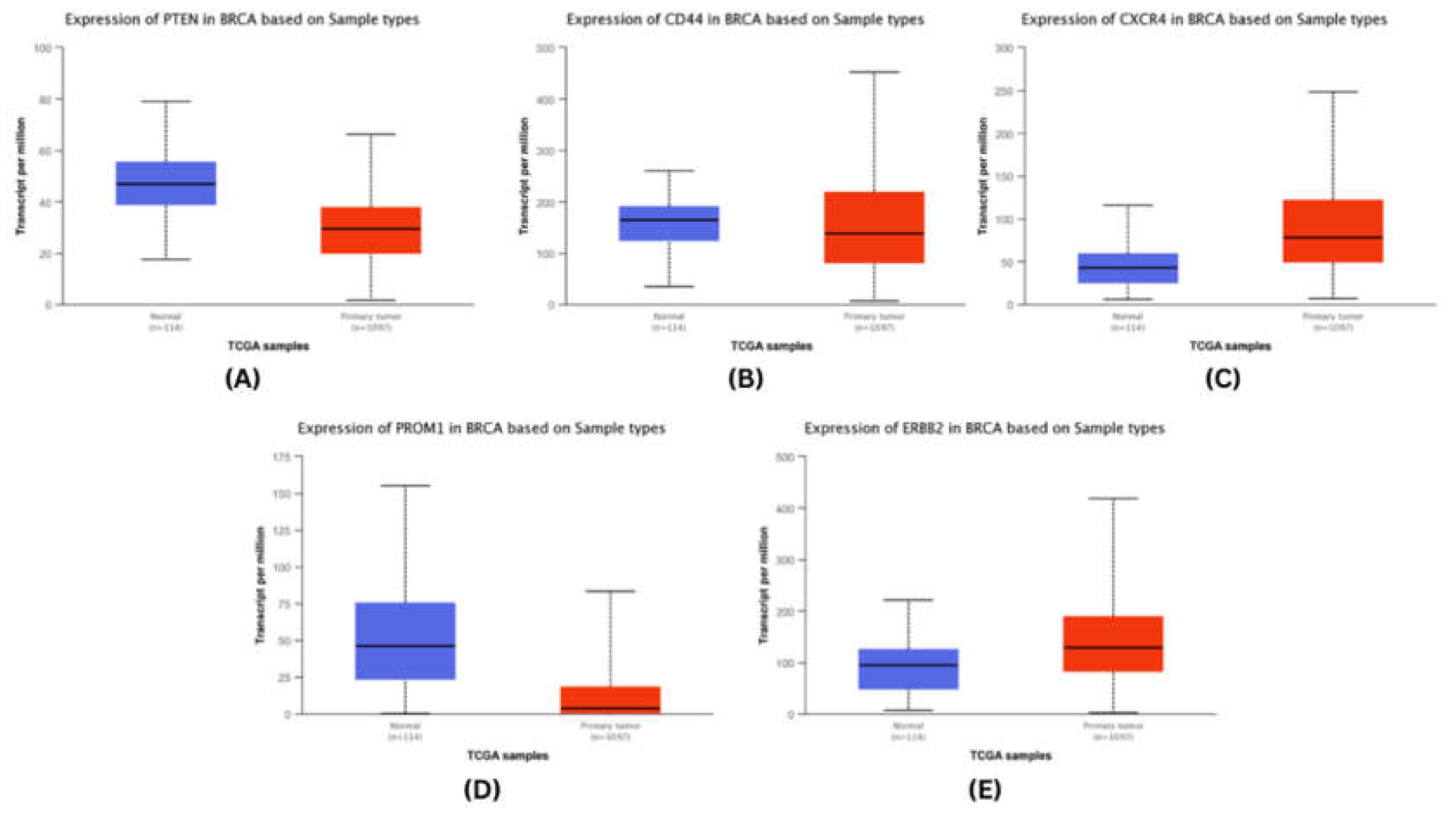

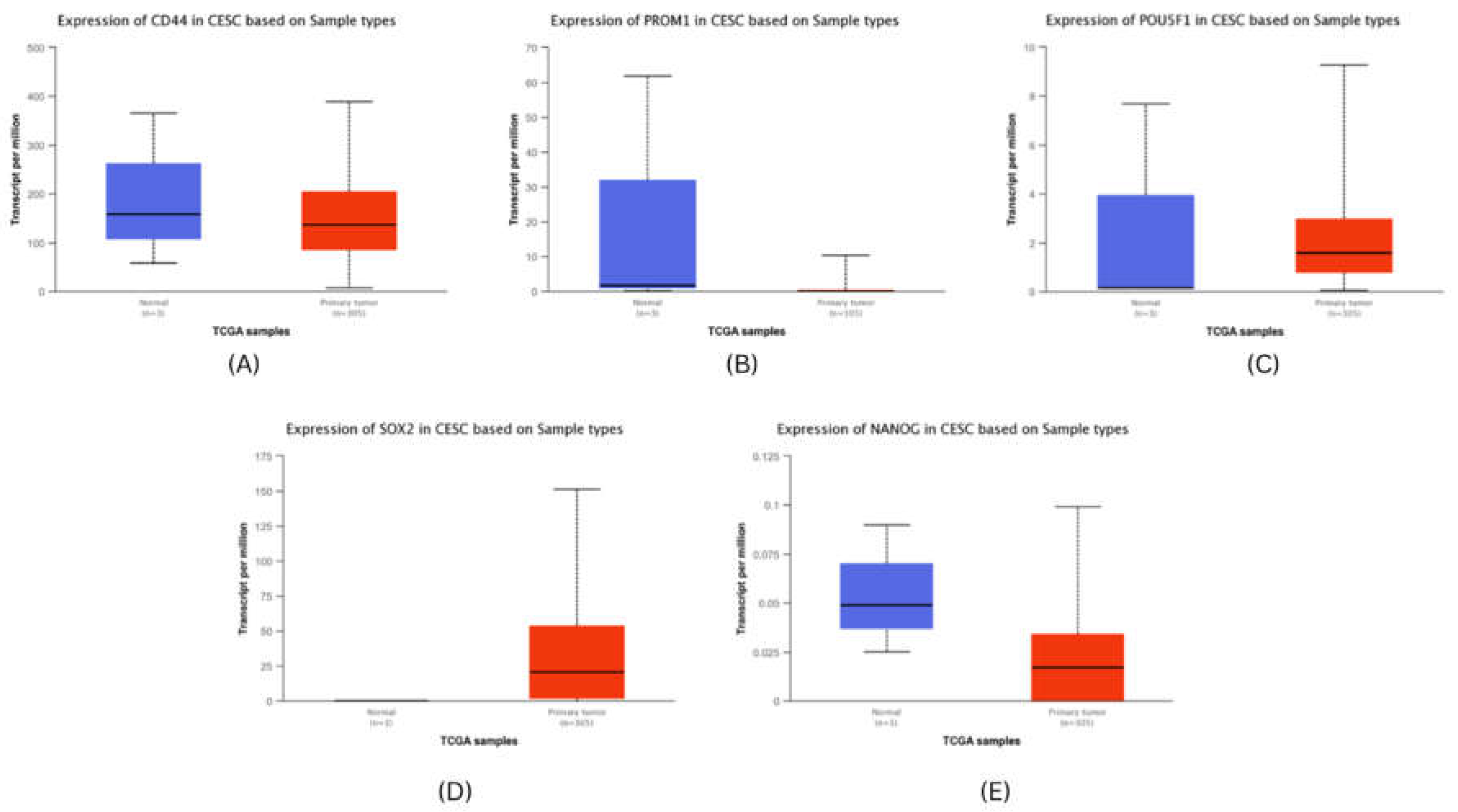

Differential expression of top 5 hub genes as stemness markers in cervical and breast cancer

We analysed the mRNA expression of each identified stem cell marker in breast and cervical cancer patients’ sample in the TCGA-BRCA and TCGA-CACX cohort using the UALCAN20.

We observed that amongst the top five hub genes in breast cancers, CXCR4 and ERBB2 were up-regulated significantly in breast cancer tissues, while the expression of PTEN, CD44, and PROM1 were downregulated significantly (

Figure 4), whereas in cervical cancer, only SOX2 was found to be significantly upregulated (

Figure 5).

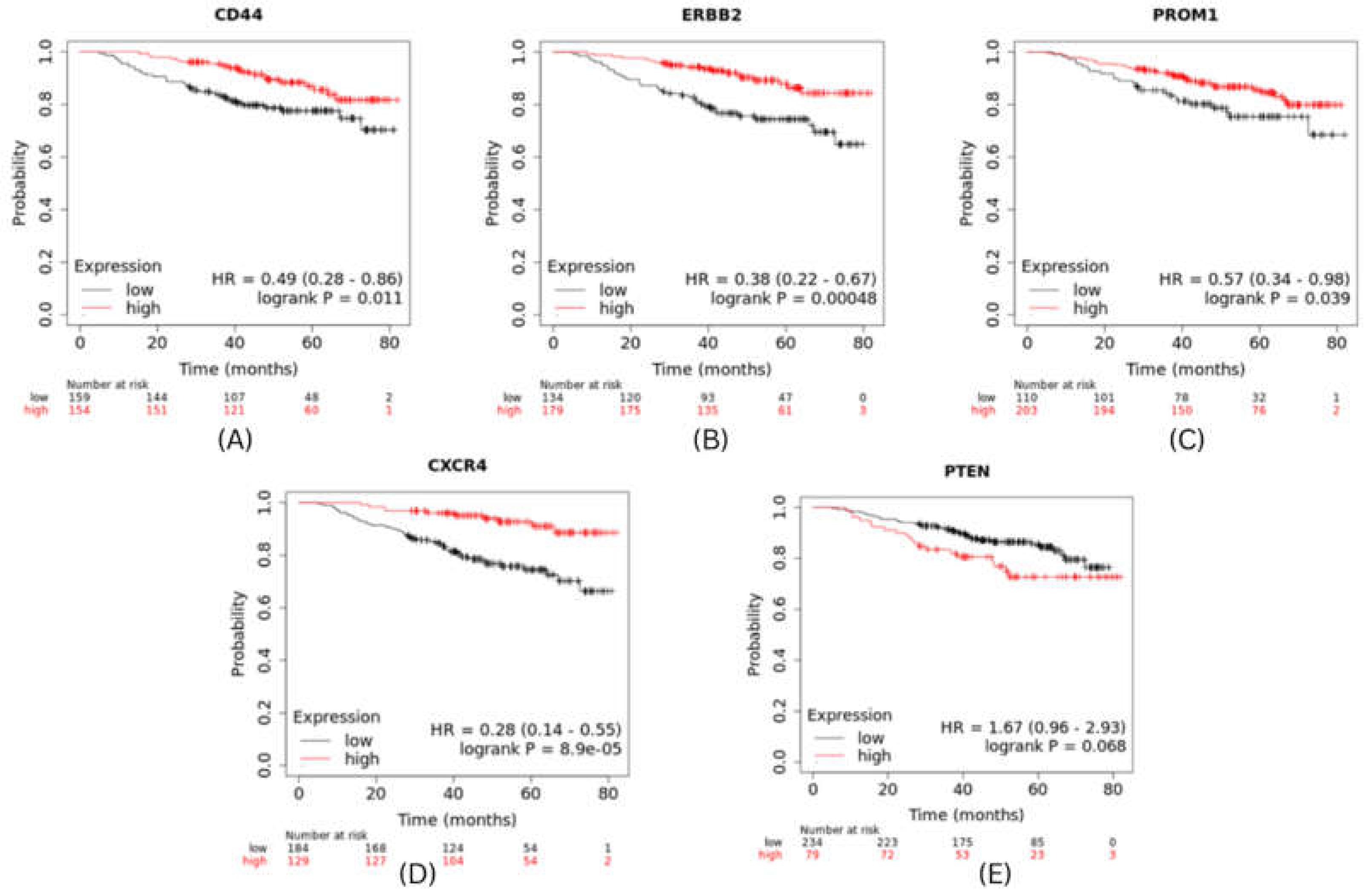

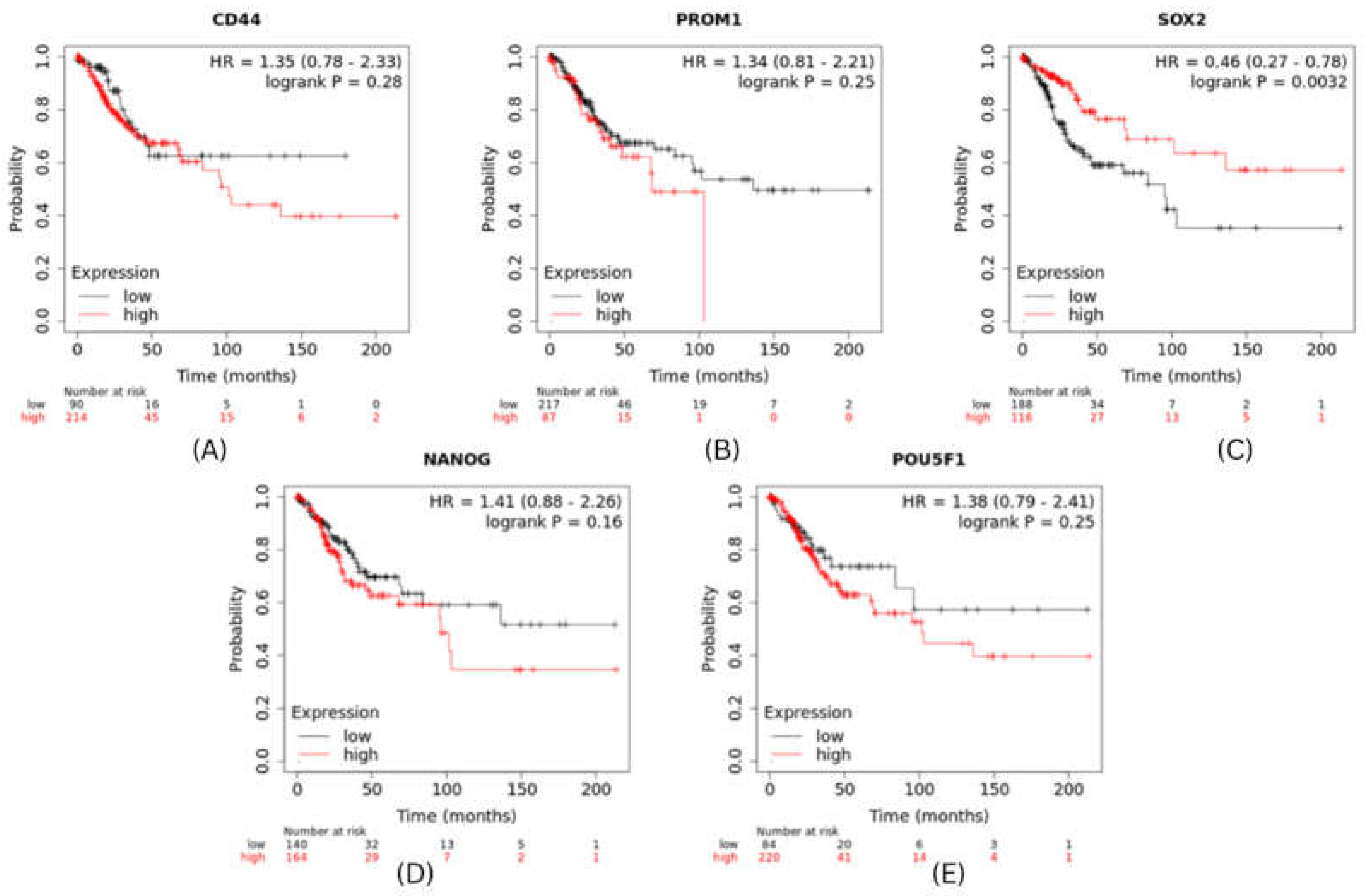

Prognosis value of hub genes in cervical and breast cancer

The expression level of top 5 hub genes (stemness markers) of cervical and breast cancer associated with metastasis risk were validated using survival analysis performed by using Kaplan-Meier method with Log-rank statistical test. We used information on survival from KM Plotter database for performing survival analysis for 5 hub genes. The results revealed that patients in high risk group have significantly worse OS than patients in low risk group (P<0.001). CXCR4 had shown highest significant value and PTEN showed hazard ratio (HR) greater than 1 (

Figure 6). Whereas in cervical cancer SOX2 were found to show significant role in survival (

Figure 7).

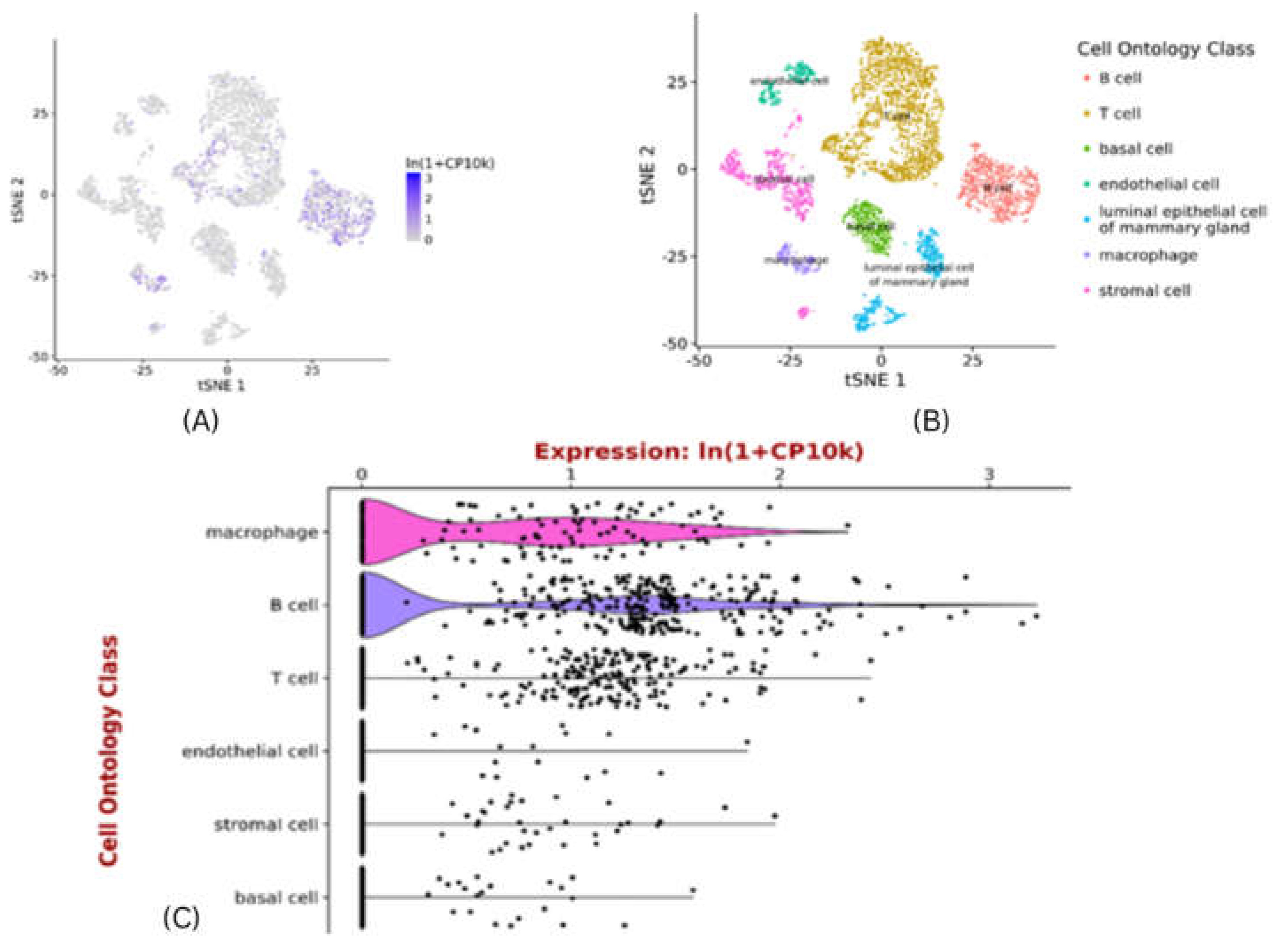

Exploring pattern of CXCR4 expression using scRNAseq data

Tabula muris is an ideal platform to exploring CXCR4 expression pattern in the mammary gland []. Expression of CXCR4 is specific to cell type, which displays high expression in the macrophages & B-cells and then in T-cells . Its expression is very low in luminal epithelial cells of mammary glands and basal cells (Figure 8). Macrophages are immune cells that play a crucial role in tumour microenvironment. Tumour associated macrophages (TAMs) promote survival of breast cancer stem cells (both directly & indirectly) and infiltrating T-cells to act as a catalyst, for immune selection of BCSCs21. The presence of TAMs and T-cells may be essential for self-renewal of BCSCs, and maintenance through growth,soluble and secreted factors. The effect of B-cells, and other immune cells has to be carefully balanced to immune selection of BCSCs which are capable to tolerate conventional therapies for breast cancer22,23. In future, the development of new agents and approaches targeting the stem cell markers in combination with components of immuniche may provide more efficacious stem cell oriented therapies for the patients of breast cancer.

Figure 8.

Single-cell RNAseq of CXCR4 expression of gene for all cell types – in mammary gland .A) tSNE plot showing single cell CXCR4 expression of gene in mus musculus super-imposed on predefined cell-clusters. B) tSNE plot showing cell-ontology of cell-clusters in a. C) Violin plot of CXCR4 expression of gene in individual cells in the clusters shown in B. Gene expression normalised to 10000 counts per-cell. Plots generated at

https://tabula-muris.ds.czbiohub.org.

Figure 8.

Single-cell RNAseq of CXCR4 expression of gene for all cell types – in mammary gland .A) tSNE plot showing single cell CXCR4 expression of gene in mus musculus super-imposed on predefined cell-clusters. B) tSNE plot showing cell-ontology of cell-clusters in a. C) Violin plot of CXCR4 expression of gene in individual cells in the clusters shown in B. Gene expression normalised to 10000 counts per-cell. Plots generated at

https://tabula-muris.ds.czbiohub.org.

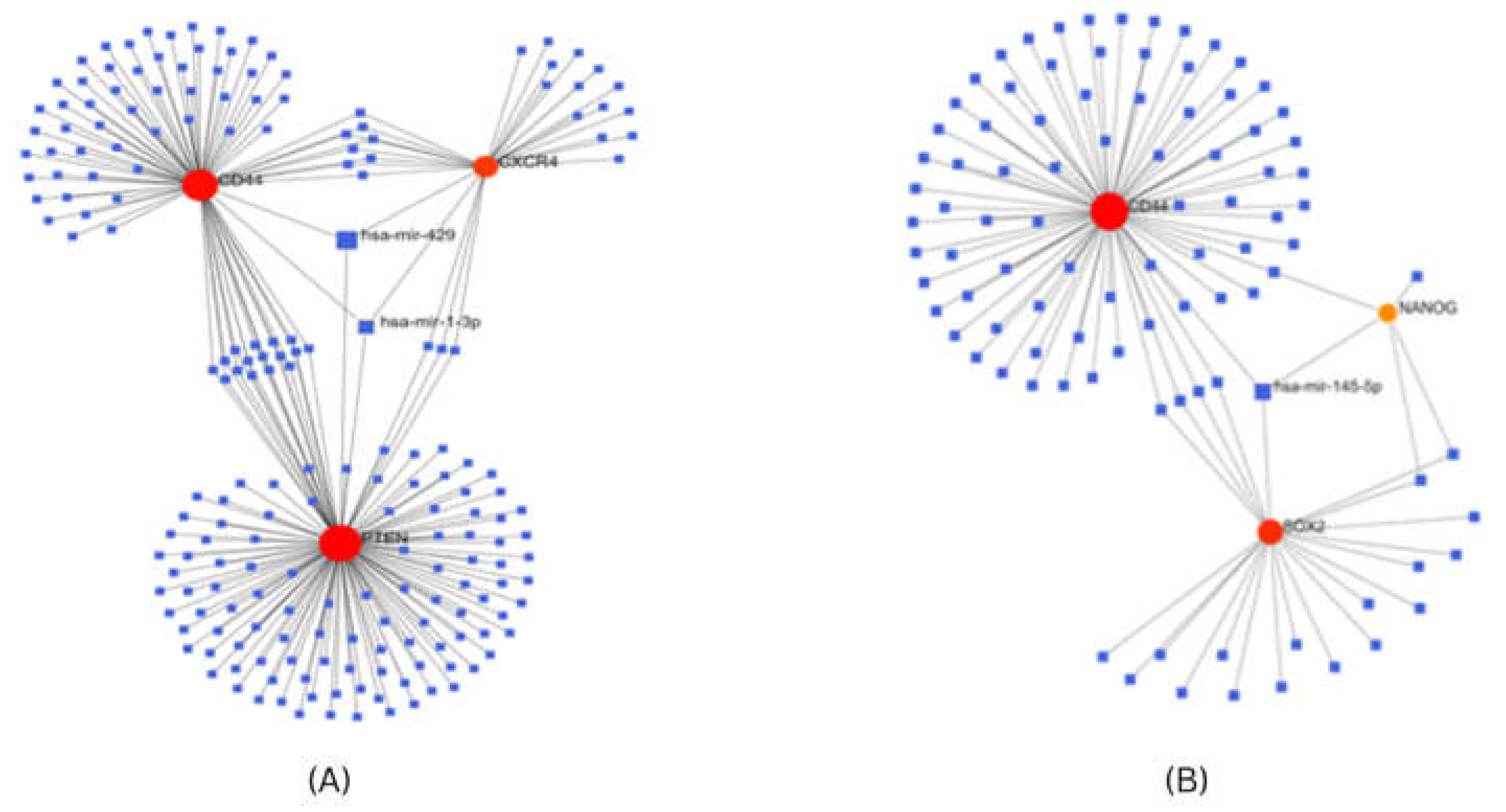

Construction of Gene-miRNA interaction network

For investigating the interaction between screened hub genes as stem cell markers, and miRNA, we used the Network analyst tool24 which contains gene-miRNA interaction data collected from TarBase v7.024, determined the miRNAs that were predicted or validated to target the stem cell markers obtained after transcriptome analysis. In breast cancer, PTEN, CD44, and CXCR4 genes co-regulate expression of common miRNA, miR-1-3p, and miR-429. In cervical cancer CD44, SOX2 and NANOG genes co-regulate the expression of a common miRNA, miR-145-5p (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Gene miRNA co-regulatory network for (A) Stem cell markers for breast cancer (B) Stem cell markers for cervical cancer.

Figure 8.

Gene miRNA co-regulatory network for (A) Stem cell markers for breast cancer (B) Stem cell markers for cervical cancer.

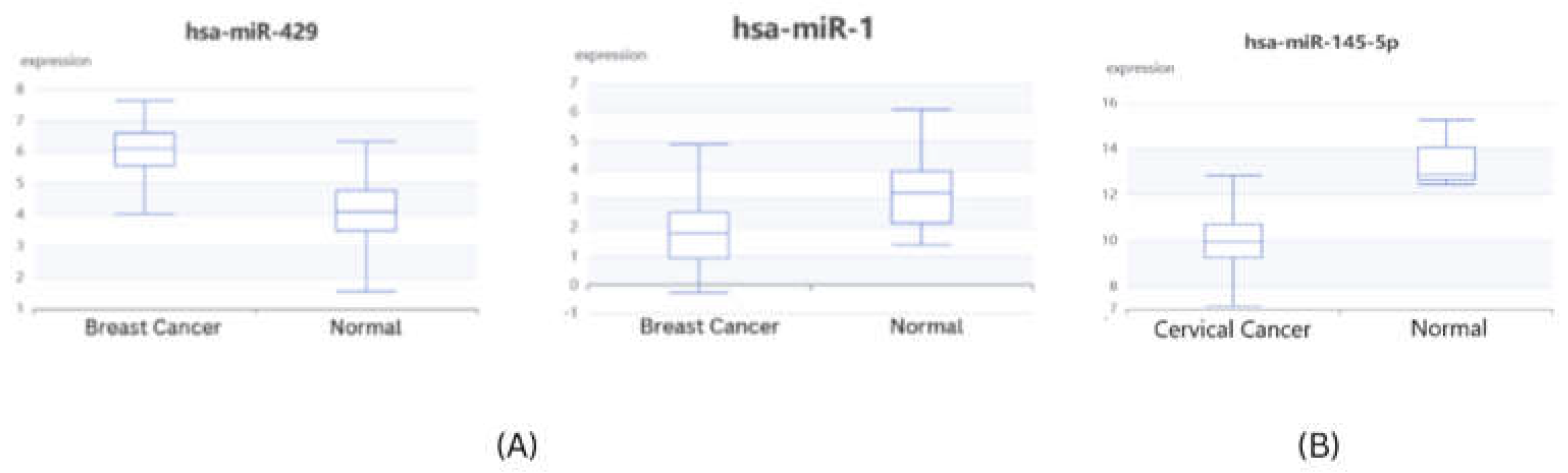

Validation of microRNA expression

The expression validation of identified microRNAs from gene-miRNA co-regulatory network was performed using dBDEMC database using GEO omnibus datasets and TCGA datasets. All three microRNAs were found to be significantly differentially expressed in patient samples. hsa-mir-1 in breast cancer and hsa-mir-145-5p in cervical cancer patients were found to be significantly downregulated (p<0.01) while has-mir-429 in breast cancer was found to be significantly upregulated (p<0.01) (

Figure 9)

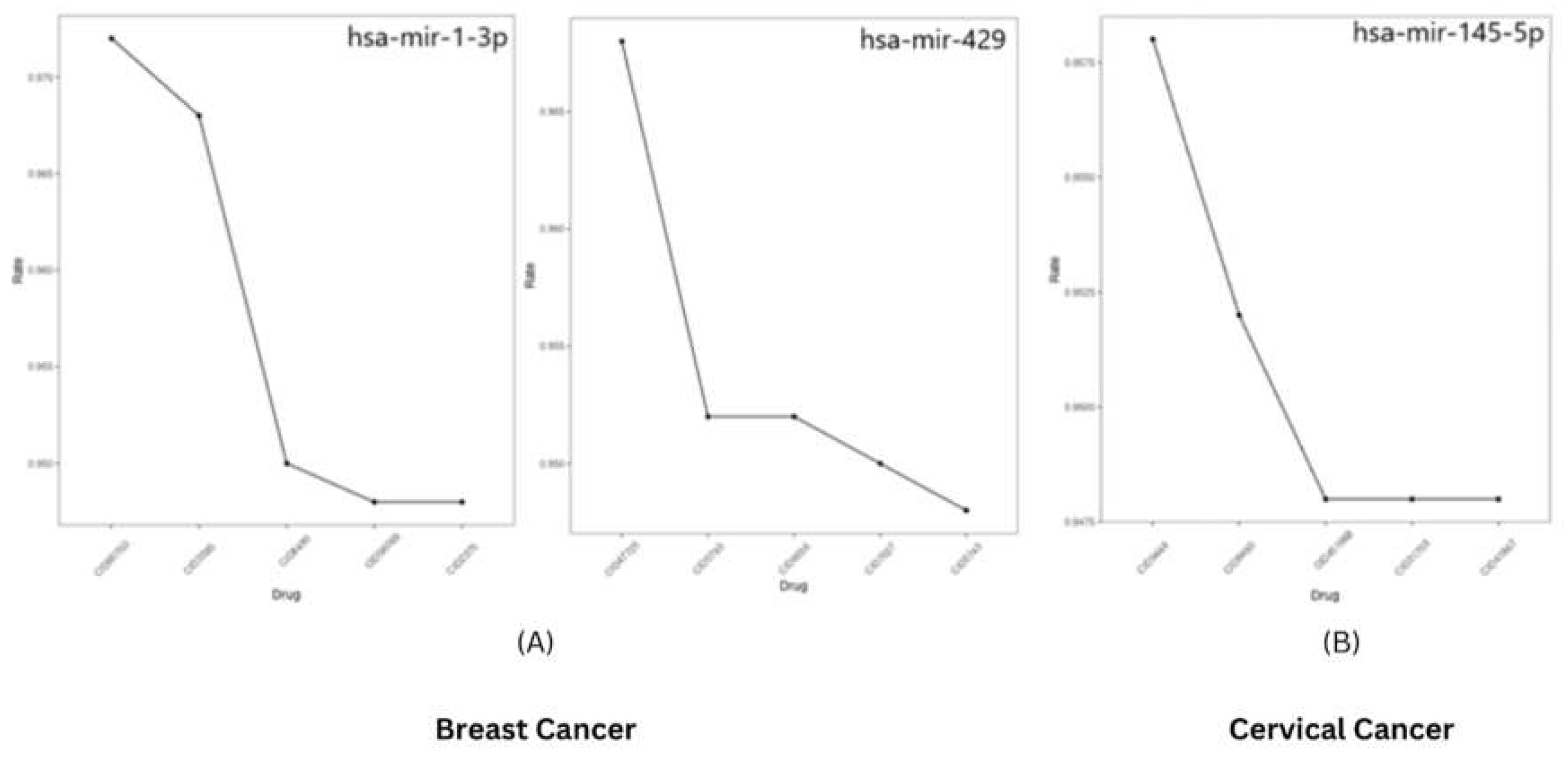

Identification of Small Molecule regulating microRNAs

To identify the small molecules regulating the expression of microRNAs using PSRR: Prediction of SM-miRNA Regulation pairs by random forest. It was found that hsa-mir-429 may be downregulated using the small molecule Goserelinacetate, while has-mir-1-3p may be upregulated using Gemcitabine. Similarly, Azacitidine may regulate hsa-mir-145-5p. The suggestion rate for all the predictions was found to be >0.9 (

Figure 10).

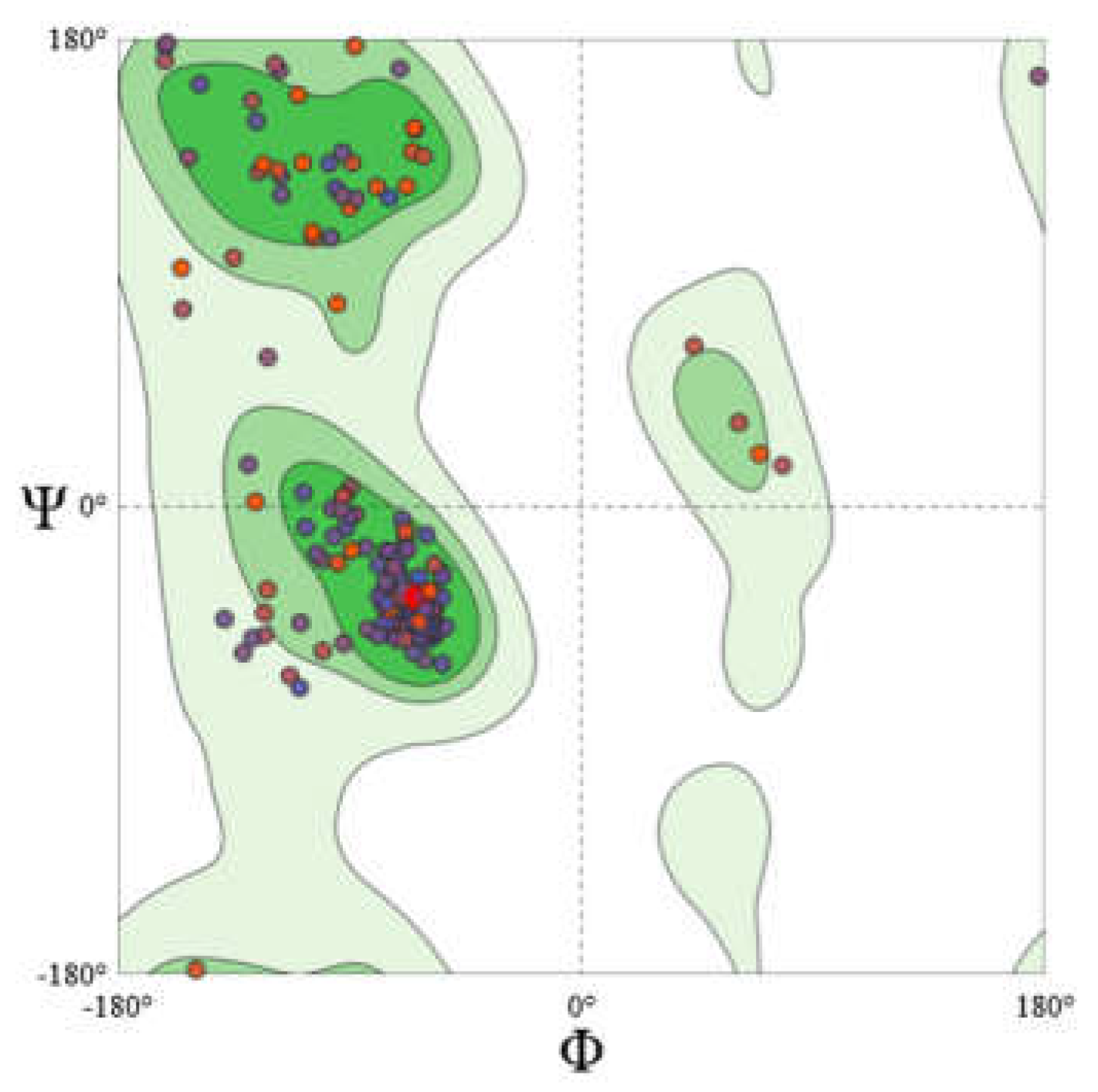

Homology Modeling of CXCR4

The CXCR4 structure was modeled by employing homology modeling approach. The model generated was further validated with the help of Expasy Structure assessment. Using a MolProbity Score of 1.86 indicated that the generated model is of good quality. Further generated model assessed using Ramachandran Plot shows that 96.2% of the core residues are within the favored region with 0% of residues found in the outliner region. Also ERRAT score of 95.9 corroborated with the quality of the model

25 (

Figure 11).

Molecular Docking and MM-GBSA refinement

Molecular docking was conducted on CXCR4 and SOX2 protein against plant secondary metabolite Annomontine, Curcumin, Coumaperine, Piperlougumines , 6,6'-Dihydroxythiobinupharidine (DTBN) and their derivates making library of 115 compounds. After docking docked pose were optimized using MM-GBSA refinement and binding free energies were calculated.

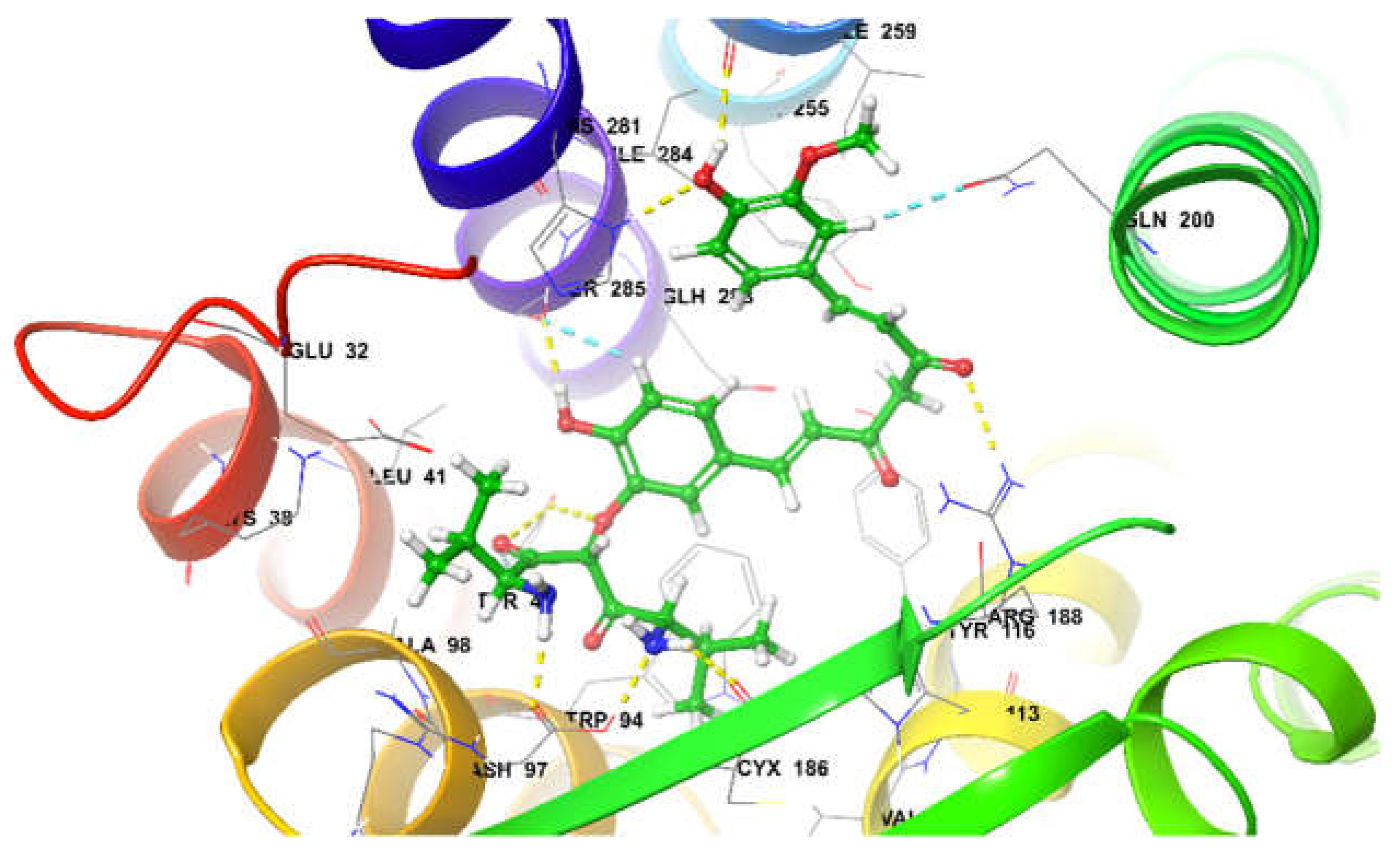

Molecular Docking of CXCR4

CXCR4 structure consists of 7 α-helices. Extracellular interface of CXCR4 is made up of 34 N-terminal residues, whereas ECL1 (100-104) (extracellular loop-I) links α-helices II & III while ECL2 (174-192) links links α-helices IV & V and ECL3 (267-273) links α-helices VI & VII. Two disulphide bonds on extracellular side of CXCR4 are reported to be crucial for ligand binding and play a role in ECL2 constraining and N-terminal segment of CRCX4 that shapes its ligand binding pocket

26,27. At the active site it was observed that Curcumin derivates; di-valinoyl curcumin, mono-methacryloyl-curcumin, and curcumin diglucoside were among the top 3 docked poses with binding free energy of -80.41 Kcal/mol, -80.20 Kcal/mol, and -74.05 Kcal/mol, respectively. Di-valinoyl curcumin at the active site of CXCR4 (-80.41 Kcal/mol) was found to be stabilized by 8 H-bond interactions and 2 aromatic H-bonds. Hydrogen Bond interactions were found with Tyr45, Asn97, Arg188, Asp262, His281 and Ser285. Whereas 2 aromatic bonds were formed with Gln200, and Ser285 respectively (

Figure 12)

Similarly, mono-methacryloyl-curcumin at the active site was stabilized by three H-bonds and two aromatic H-bond (-80.20 Kcal/mol). Futher single parallel π…. π stacking interaction was observed. Interaction of Hydrogen bond was observed with amino acid residue Tyr45, Asn97, and Arg188. The aromatic H-bonds were formed with Tyr188 and Gln288. Whereas Trp94 pf CXCR4 formed parallel π…. π stacking interaction. Curcumin diglucoside (-74.05 Kcal/mol) at the active site was stabilized by four Hydrogen bonds and two aromatic bonds. The H-bond interactions were formed between Gln32, Asn97, Tyr190, and Pro191, whereas aromatic H-bond Try116 and cys186.

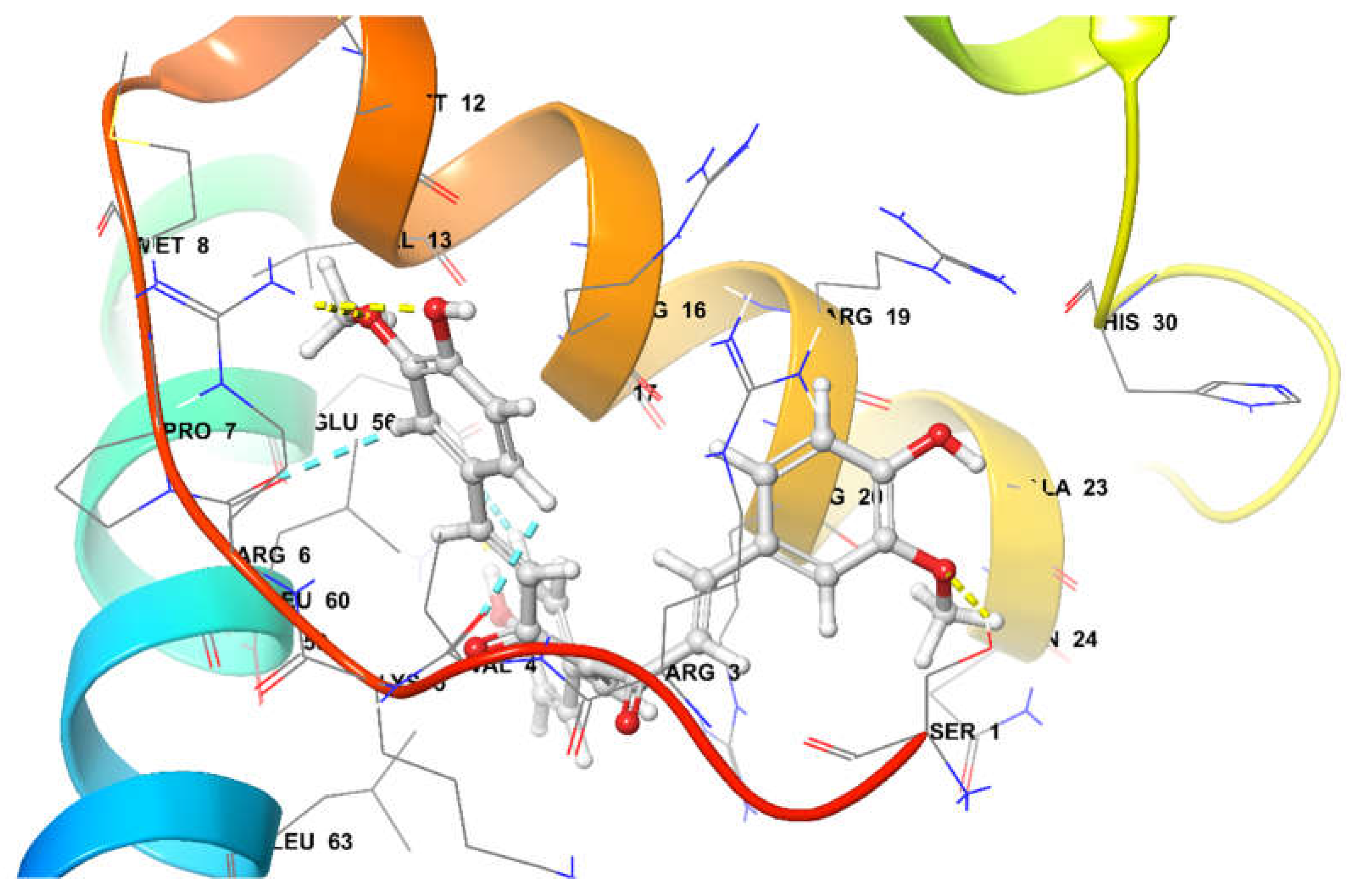

Molecular Docking of SOX-2

The crystal structure of SOX-2 consists of 3 α-helices connected via loops. Due to non-availabilty of binding site literature, active site predictions were made using SiteMap module of schrodinger. The predicted active site was found to be located between the helics I (10-24) and Helics-III (residue 50 – 66) covered by the loop (residue1-8) with sitescore and Druggability score of 0.816 and 0.80. The predicted site was used for docking of ligand library. It was observed that 4-(4-hydroxybenzylidene) curcumin, curcumin diglucoside, and N-phenylpyrazole curcumin were among the top 3 docked poses with binding free energy of -92.22 Kcal/mol, -76.80 Kcal/mol, and -75.92 Kcal/mol, respectively.

4-(4-hydroxybenzylidene) curcumin (-92.22 Kcal/mol) at the active site was found to be stabilized by Four Hydrogen bonds and three aromatic hydrogen bonds. Interactins of Hydrogen bond were observed with amino-acid Ser1, Arg6, and Glu56. Additionally, aromatic Hydrogen bond interactions were observed with amino acid with Val4, Arg6, and Glu56 (

Figure 13).

Similarly, curcumin di-glucoside was stabilized by four hydrogen bonds and a single aromatic hydrogen bond. Hydrogen bond interactions were observed with amino acid residues Arg6, Glu56, and Arg59. While an aromatic hydrogen bond was observed with Arg6.

N-phenylpyrazole curcumin (-75.92 Kcal/mol) at the active site was observed to be stabilized by a single Hydrogen-Bond and four aromatic Hydrogen bonds. The Hydrogen bond interaction was found with Arg6, whereas aromatic h-bonds were observed with amino acid residues Ser1, Val4, Arg6, and Arg16. In addition, π-cation interaction was also observed with Arg20.

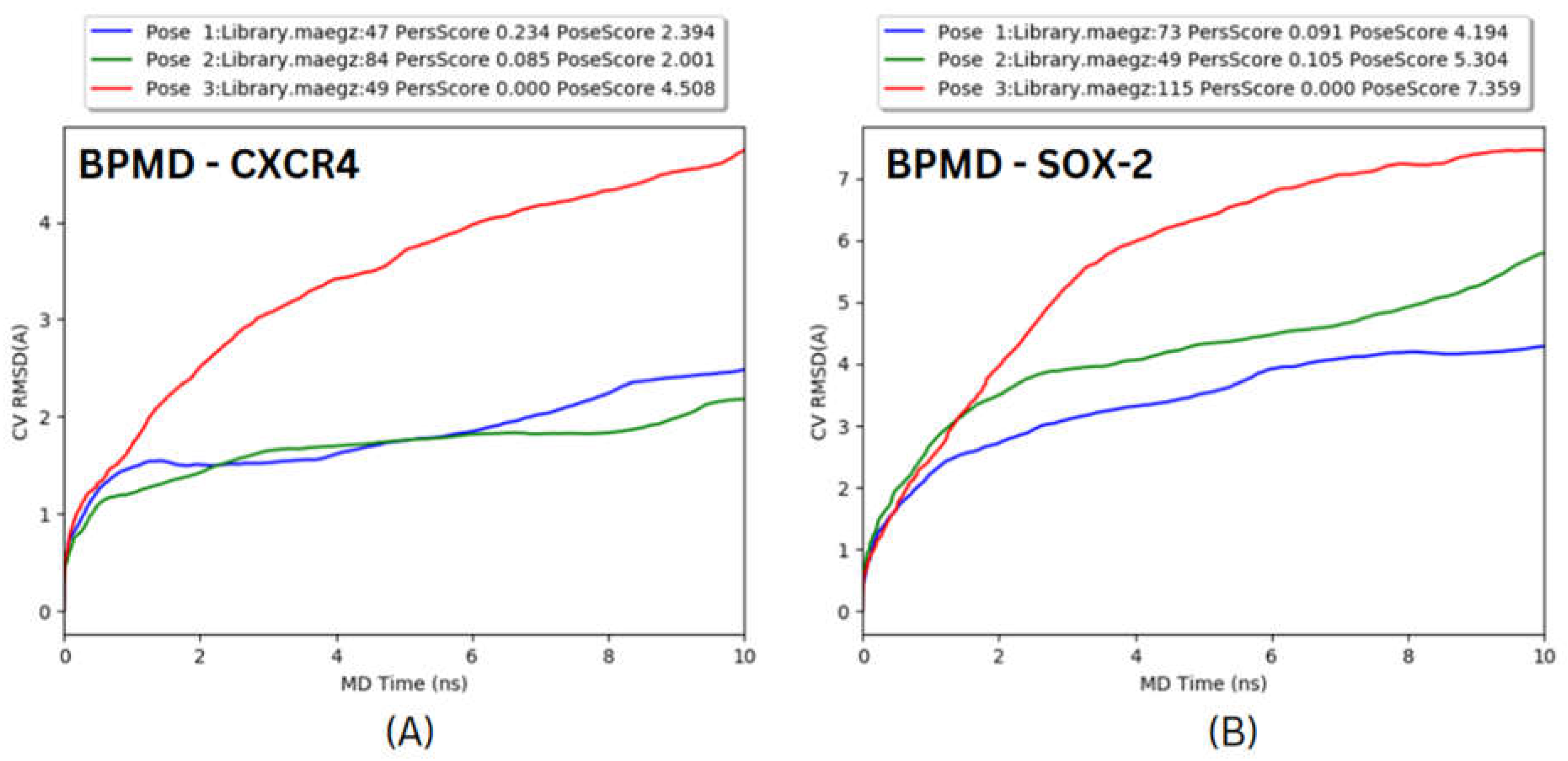

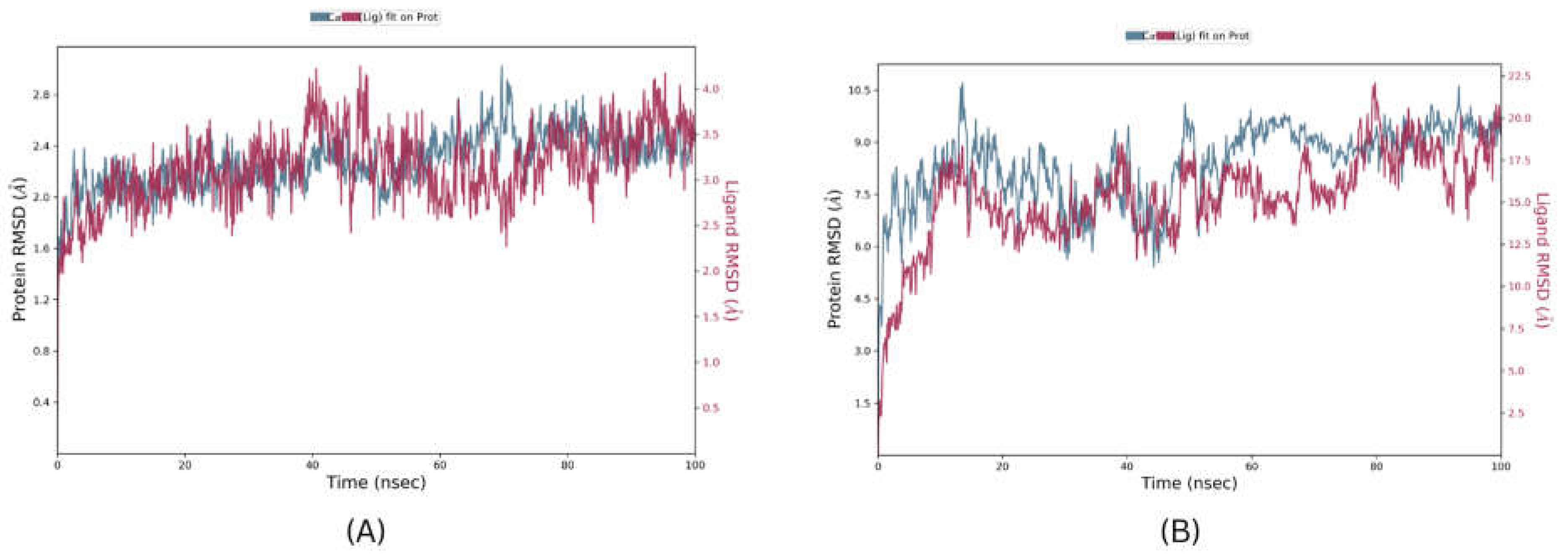

Molecular Dynamics Studies

Molecular Dynamics is a crucial step for the development of Computer Assisted Drugs and their designing, providing validation of docked complexes and their stability. The Top pose of CXCR4 and SOX-2 from BPMD analysis were further validated using 100ns unbiased molecular dynamic studies. The results of simulations were analysed by using RMSD, RMSF, and the number, and type of interactions. The protein RMSD values for CXCR4 complex and SOX-2 complex were found to be 2.1 Angstrom and 8.3 Angstrom, respectively and Ligand RMSD values for the CXCR4 complex and SOX-2 complex were found to be 3.1 Angstrom and 15.2 Angstroms, respectively (

Figure 15) suggesting that the SOX-2 complex is highly unstable under the molecular dynamic system. In terms of RMSF, only regions from residue 8 to 23 in SOX-2 were found to be within the fluctuation range of 3.5 Angstrom rest of each residue had RMSF value >3.5 Angstrom. In CXCR4, only few residues Asp181, His228, Ser229, and Lys230 were found to have RMSF values higher than 3.5 angstroms. In terms of RMSD values, results suggest that the SOX-2 complex is highly unstable and unlikely to interact efficiently with its bound ligand. The Ligand protein contacts reveal that Di-valinoyl curcumin was able to interact with CXCR4 by forming 3 Hydrogen bonds of strength > 50% with amino acid residues Asp262, Tyr255, His113 throughout the simulation. Further, 2 water bridge interactions were formed between Trp94 and Asp171 with a bond strength of 32% and 40%, respectively. Additionally, Di-valinoyl curcumin was stabilized by π-cation interaction with Arg188 with a strength of 68%. In contrast to CXCR4, SOX-2 being highly unstable resulted in only single Hydrogen bond interaction with Glu56 with bond strength of 38%.

3. Discussion

Tumors consist of multiple clones of different tumor cells population that differ in morphology, function, and molecular structure due to molecular alteration during the course of development and growth. Moreover, tumor cells that are similar at the genetic level have different modes of epigenetic regulation29. Small populations of tumor cells are capable of self-renewal and due to their capability of initiating tumor growth, they have been named as cancer stem cells (CSCs). CSCs play a crucial role in the recurrence of disease after treatment and they are important to develop targeted therapies. They are identified by stemness-related biomarkers30.

BCSCs are responsible for breast cancer development, tumor recurrence, metastasis, and drug resistance. It is difficult to identify the population of BCSCs and understand their molecular mechanism for developing therapeutic targets31. In this study, we try to find out the top hub genes and associated microRNas as stemness biomarkers in breast and cervical cancer stem cells and potential natural compound derivates for their targeting.

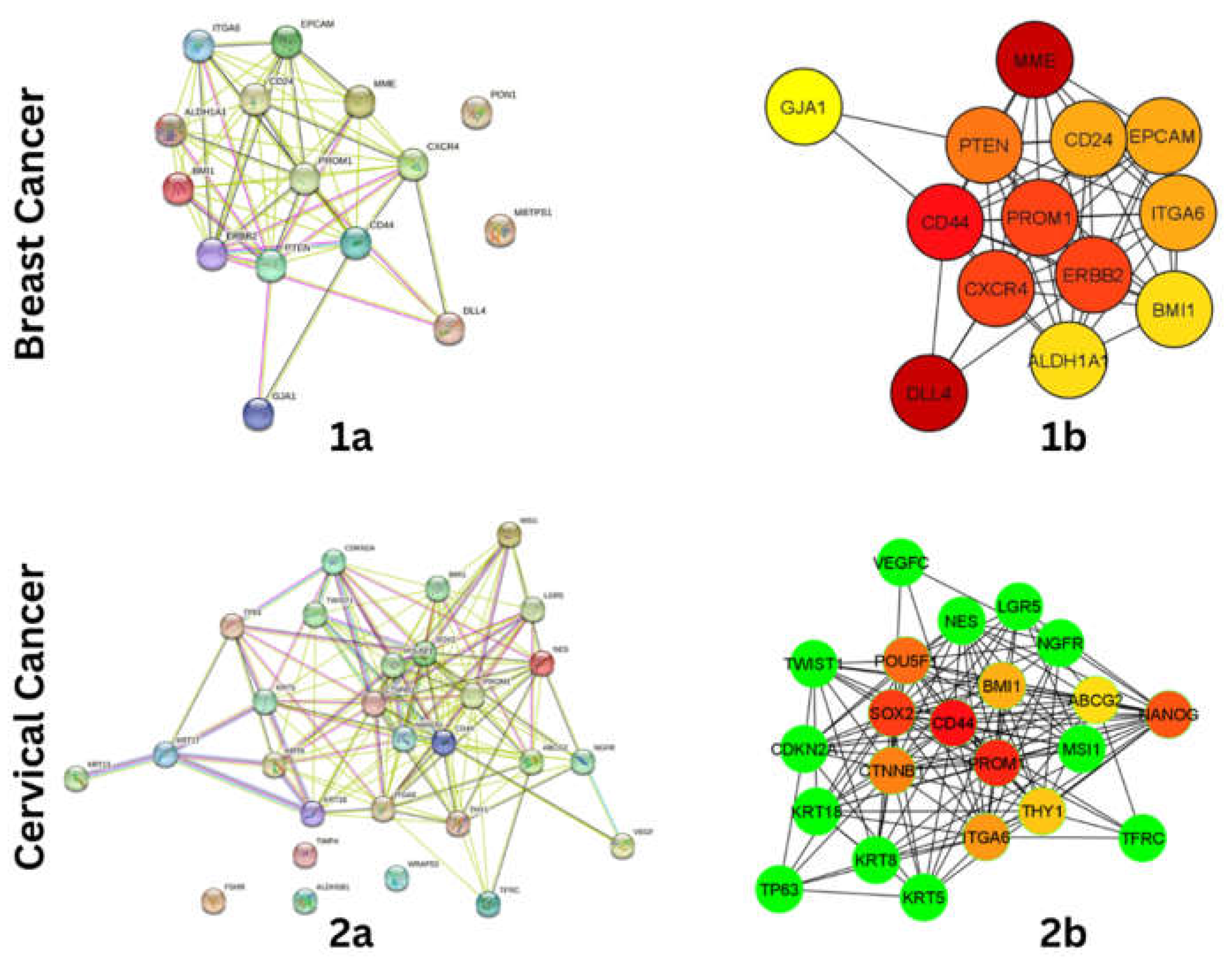

Among the top stem cell markers of breast cancer cells, CXCR4 had shown highly significant expression as compared to normal and the overall survival in the high-risk group is low as compared to normal. Recent studies revealed that CXCR4 plays a crucial role in breast cancer metastasis. The upregulation of CXCR4 expression has prognostic significance due to the increased number of receptors and their signals. Hence, it is essential to find out the mechanism which plays a crucial role in the upregulation of CXCR4 expression. The promoter region of CXCR4 contains nuclear receptor-1 (NRF-1) and Ying Yang-1 (YY-1) was found to be responsible for the upregulation, and downregulation of CXCR4 in breast cancer stem cells []. CXCR4 is present in various cell types including macrophages, T-cells and breast cancer cells and cancer associated fibroblasts (CAF) effectively attract monocytes through the CXCR4 pathway and promote formation of cancer stem cells. Therefore, our findings have the potential to lead to novel therapy for breast cancer cells to target CXCR4 mediated tumor associated microenvironment (TAM).

In the case of cervical cancer, SOX2 is the most significant among top stem cell markers. SOX2 is a transcription factor which are known to play an important role in embryonic development and it is expressed in undifferentiated embryonic stem cells. SOX2 is detected in several tumors, indicating its role in tumor development. Several studies reported increased expression of nuclear SOX2 as compared to normal in cervical cancer32. These remarkable expressions of SOX2 indicate that it may play an pivitol role in the pluripotency of cells in differentiation, and self-renewal.

In the present study, functional enrichment analysis of CSCs markers in breast, and cervical cancer indicated the enrichment of pathways in cancer, mi-RNAs in cancer, and signaling pathways in regulating the pluripotency of stem cells.

Correlation analysis was conducted to understand the relationship between the miRNAs, and CSCs marker of breast, and cervical cancer33. The miR-145-5p is the common target of SOX2, NANOG, and CD44 (CCSCs markers) and it has been reported as a tumor suppressor34. Although in the case of breast cancer, miR- 429 is the common target of CD44, CXCR4, and PTEN, (BCSCs markers) and they have been reported as oncogene while miR-1 also have similar targets and it is downregulated hence it is reported as a tumor suppressor.

The Molecular docking, Binding Pose Metadynamics, and Molecular Dynamics analysis found that Di-valinoyl curcumin is most suitable among the in-house library to target CXCR4. It was also found that targeting SOX-2 remains a challenge, due largely to its “undruggable” nature35. The undruggable nature can be explained through the large extent of fluctuation and deviation observed during the course of simulation resulting in the pushing out of the ligand from its binding pocket (supplementary video 1), suggesting the exploration of non-reversible drugs targeting SOX-2.

Results from the present studies suggest that CXCR4 and SOX2, while miRNAs miR-429, miR-1, and miR-145 may be used as important stem cell markers in the diagnosis of breast, and cervical cancer; and also act as potential therapeutic target molecules for our novel therapeutic drugs. Further, Di-valinoyl curcumin targeted against CXCR4 needs to be validated in an in-vitro setup.

4. Computational Methodology

Identification of stem cell markers

Stem cell markers of breast cancer and cervical cancer were retrieved from the literature database using the search Keywords “ Breast Cancer” or “ Cervical Cancer” AND “ Stem Cell Markers, shortlisted Stem Cell markers were further analyzed.

Protein-Protein Interaction and Hub-Gene Identification

To understand the interaction among the stem cell markers, ppi network was constructed using STRING Database (

https://string-db.org/), with interaction score of 0.700 (high confidence). The interaction includes both direct (physical) and indirect (functional) associations. The constructed network was exported to Cytoscape 3.8 for Hub-Gene identification in cytoHubba using the MCC scoring method.

Identification of Hub-Gene- co regulated MicroRNAs

Hub-Gene-regulated microRNAs for Breast and Cervical stem cell marker related were identified using network analyst (

https://www.networkanalyst.ca/) using the TarBase v7.0 database.

mi-RNA expression validation

microRNA expression of Breast Cancer and Cervical Cancer stem cell associated hub-genes was done using the dbDMEC database (

https://www.biosino.org/dbDEMC/search) using Geo dataset GSE38167 for Breast Cancer and TCGA Dataset for Cervical Cancer.

TCGA Expression Validation of Hub-Genes

mRNA expression of identified hub genes was validated in breast cancer, and cervical cancer patients’ samples in the TCGA-BRCA and TCGA-CACX cohort with the help of UALCAN (

http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/).

Survival Analysis

The assessment of prognostic value was conducted by employing Kaplan-Meier curve and Long-rank method for each differentially expressed stem cell marker by employing KM Plotter (

https://kmplot.com)

Molecular Docking and MM-GBSA Refinement

Docking studies on SOX-2 (PDB Id: 2LE4) and Homology Modelled CXCR4 was performed . The generated model was validated using Swiss-Model structure assessment. The plant secondary metabolite Annomontine, Curcumin, Coumaperine, Piperlougumines , 6,6'-Dihydroxythiobinupharidine (DTBN) and their derivates were used to generate secondary plant metabolite library of 115 molecules. Molecular docking was performed using Schrodinger (Schrödinger LLC, New York, NY, USA).

Molecular Dynamic Simulation

Molecular dynamics simulations for 100ns of best docked pose complexes was conducted by employing DESMOND module of Schrodinger (Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, USA). The complexes were fully immersed inside an ortho-rhombic box of SPC solvent model. The

System was neutralized prior to simulation by introduction of counter ions , and NaCl of 0.15M concentration at 300 K temperature and 1.013 bar atmospheric pressure

5. Conclusion

Evidence from earlier studies suggest that cancer cells grow and metastasize due to the dysregulation of multiple pathways. Cancer cells have small population of stem cells (CSCs) which are responsible for recurrence, and resistance of the disease. Hence, compounds would be required that block the pathways of CSCs self-renewal and resistance. Two most common gynaecological cancers; breast, and cervical cancer stem cells self renewal, and resistance pathways can be modulated by novel plant-based metabolites like hydroxypiperloungumines, Coumaperine, annomontine, curcumin derivatives and 6,6'-Dihydroxythiobinupharidine (DTBN). CXCR4 and SOX2, while miRNAs miR-429, miR-1, and miR-145 may be used as important stem cell markers in the diagnosis of breast, and cervical cancer; and may act as potential therapeutic target molecules for novel therapeutic drugs. Further validation is necessary to validate Di-valinoyl curcumin targeted against CXCR4.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.W, M.A, D.S Methodology, K.W, M.A, Software, K.W, M.A., Validation, K.W, M.A, D.S, Formal analysis, K.W, M.A, Investigation, K.W, M.A., Writing – original draft preparation, , K.W, M.A, D.S., Writing – review, and editing., K.W, M.A, D.S, S.H visualisation., K.W, M.A, D.S, S.H Supervision, S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the manuscript version.

Data Availability Statement

All the data generated have been published in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

KW acknowledges ICMR for SRF fellowship vide fellowship No. 45/18/2022-DDI/BMS. MA acknowledges ICMR for RA fellowship vide fellowship No. 3/2/3/73/2022-NCD-III.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(1):7-33. [CrossRef]

- Keysar SB, Jimeno A. More than markers: Biological significance of cancer stem cell-defining molecules. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9(9):2450-2457. [CrossRef]

- Cancer Stem Cell Markers Research Areas: R&D Systems. Available online: https://www.rndsystems.com/research-area/cancer-stem-cell-markers (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Chen W, Dong J, Haiech J, Kilhoffer MC, Zeniou M. Cancer Stem Cell Quiescence and Plasticity as Major Challenges in Cancer Therapy. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016. [CrossRef]

- Gulaia V, Kumeiko V, Shved N, et al. Molecular mechanisms governing the stem cell’s fate in brain cancer: Factors of stemness and quiescence. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:388. [CrossRef]

- Waidha K, Anto NP, Jayaram DR, et al. 6,6′-Dihydroxythiobinupharidine (DTBN) Purified from Nuphar lutea Leaves Is an Inhibitor of Protein Kinase C Catalytic Activity. Mol 2021, Vol 26, Page 2785. 2021;26(9):2785. [CrossRef]

- Waidha K, Saxena A, Kumar P, Sharma S, Ray D, Saha B. Design and identification of novel annomontine analogues against SARS-CoV-2: An in-silico approach. Heliyon. 2021;7(4). [CrossRef]

- Muthuraman S, Sinha S, Vasavi CS, et al. Design, synthesis and identification of novel coumaperine derivatives for inhibition of human 5-LOX: Antioxidant, pseudoperoxidase and docking studies. Bioorg Med Chem. 2019;27(4):604-619. [CrossRef]

- Subramani M, Ramamoorthy G, Hemaiswarya S, et al. Hydroxy Piperlongumines: Synthesis, Antioxidant, Cytotoxic Effect on Human Cancer Cell Lines, Inhibitory Action and ADMET Studies. ChemistrySelect. 2020;5(38):11778-11786. [CrossRef]

- Waidha K, Zurgil U, Ben-zeev E, Gopas J, Rajendran S, Golan-goldhirsh A. Inhibition of Cysteine Proteases by 6,6′-Dihydroxythiobinupharidine (DTBN) from Nuphar lutea. Mol 2021, Vol 26, Page 4743. 2021;26(16):4743. 4743. [CrossRef]

- Deo SVS, Sharma J, Kumar S. GLOBOCAN 2020 Report on Global Cancer Burden: Challenges and Opportunities for Surgical Oncologists. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29(11):6497-6500. [CrossRef]

- Burd EM. Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16(1):1. [CrossRef]

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209-249. [CrossRef]

- Lei J, Ploner A, Elfström KM, et al. HPV Vaccination and the Risk of Invasive Cervical Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(14):1340-1348. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Powell K, Li L. Breast Cancer Stem Cells: Biomarkers, Identification and Isolation Methods, Regulating Mechanisms, Cellular Origin, and Beyond. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(12):1-28. [CrossRef]

- Sin WC, Lim CL. Breast cancer stem cells — From origins to targeted therapy. Stem Cell Investig. 2017;4(11). [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, et al. STRING v11: Protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D607-D613. [CrossRef]

- DAVID Functional Annotation Bioinformatics Microarray Analysis. Available online: https://david.ncifcrf.gov/ (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- KEGG PATHWAY Database. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Chandrashekar DS, Bashel B, Balasubramanya SAH, et al. UALCAN: A Portal for Facilitating Tumor Subgroup Gene Expression and Survival Analyses. Neoplasia. 2017;19(8):649-658. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Song Y, Du W, Gong L, Chang H, Zou Z. Tumor-associated macrophages: an accomplice in solid tumor progression. J Biomed Sci 2019 261. 2019;26(1):1-13. [CrossRef]

- Ostuni R, Kratochvill F, Murray PJ, Natoli G. Macrophages and cancer: from mechanisms to therapeutic implications. Trends Immunol. 2015;36(4):229-239. [CrossRef]

- Dehne N, Mora J, Namgaladze D, Weigert A, Brüne B. Cancer cell and macrophage cross-talk in the tumor microenvironment. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2017;35:12-19. [CrossRef]

- Zhou G, Soufan O, Ewald J, Hancock REW, Basu N, Xia J. NetworkAnalyst 3.0: A visual analytics platform for comprehensive gene expression profiling and meta-analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W234-W241. [CrossRef]

- Colovos C, Yeates TO. Verification of protein structures: patterns of nonbonded atomic interactions. Protein Sci. 1993;2(9):1511-1519. [CrossRef]

- Wu B, Chien EYT, Mol CD, et al. Structures of the CXCR4 chemokine GPCR with small-molecule and cyclic peptide antagonists. Science (80- ). 2010;330(6007):1066-107. [CrossRef]

- Zhou H, Tai HH. Expression and Functional Characterization of Mutant Human CXCR4 in Insect Cells: Role of Cysteinyl and Negatively Charged Residues in Ligand Binding. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;373(1):211-217. [CrossRef]

- Allegra M, Tutone M, Tesoriere L, Attanzio A, Culletta G, Almerico AM. Evaluation of the IKKβ Binding of Indicaxanthin by Induced-Fit Docking, Binding Pose Metadynamics, and Molecular Dynamics. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:2400. [CrossRef]

- Parsons BL. Multiclonal tumor origin: Evidence and implications. Mutat Res Mutat Res. 2018;777:1-18. [CrossRef]

- Yu Z, Pestell TG, Lisanti MP, Pestell RG. Cancer Stem Cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44(12):2144. [CrossRef]

- Saeg F, Anbalagan M. Breast cancer stem cells and the challenges of eradication: a review of novel therapies. Stem Cell Investig. 2018;5:39. [CrossRef]

- Bao Z, Zhan Y, He S, et al. Increased Expression Of SOX2 Predicts A Poor Prognosis And Promotes Malignant Phenotypes In Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:9095. [CrossRef]

- In silico analysis of the role of hsa-miR-155-5p in cervical cancer | Aftab | Chemical Biology Letters. Available online: http://pubs.iscience.in/journal/index.php/cbl/article/view/1278 (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Aftab M, Poojary SS, Seshan V, et al. Urine miRNA signature as a potential non-invasive diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in cervical cancer. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1). [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Xiong X, Sun Y. Functional characterization of SOX2 as an anticancer target. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2020 51. 2020;5(1):1-17. [CrossRef]

- Yu F, Li B, Sun J, et al. PSRR: A Web Server for Predicting the Regulation of miRNAs Expression by Small Molecules. Front Mol Biosci. 2022;9:48. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

(1a)Protein-Protein interaction of Breast Cancer Stem cell marker genes, (1b) Identified Hub-gene network of Breast Cancer Stem cell marker genes (2a) Protein-Protein interaction of Cervical Cancer Stem cell marker gene. (2b) Identified Hub-gene network of cervical cancer stem cell marker genes.

Figure 1.

(1a)Protein-Protein interaction of Breast Cancer Stem cell marker genes, (1b) Identified Hub-gene network of Breast Cancer Stem cell marker genes (2a) Protein-Protein interaction of Cervical Cancer Stem cell marker gene. (2b) Identified Hub-gene network of cervical cancer stem cell marker genes.

Figure 2.

Functional Enrichment analysis of Breast Cancer stem cell related Hub-genes. (A) Cellu-lar Component (B) Molecul-ar Function (C) Bio-logical Process, and (D) KEGG Bio-logical Path-ways. P-Value <0.001.

Figure 2.

Functional Enrichment analysis of Breast Cancer stem cell related Hub-genes. (A) Cellu-lar Component (B) Molecul-ar Function (C) Bio-logical Process, and (D) KEGG Bio-logical Path-ways. P-Value <0.001.

Figure 3.

Functional Enrichment analysis of Cervical Cancer stem cell related Hub-genes. (A) Cellu-lar Component (B) Molecu-lar Function (C) Bio-logical Process and, (D) KEGG Bio-logical Path-ways. P-Value <0.001.

Figure 3.

Functional Enrichment analysis of Cervical Cancer stem cell related Hub-genes. (A) Cellu-lar Component (B) Molecu-lar Function (C) Bio-logical Process and, (D) KEGG Bio-logical Path-ways. P-Value <0.001.

Figure 4.

mRNA expresssion validation of BRCA hubgenes (A) PTEN (B) CD44 (C) CXCR4 (D) PROM1 (E) ERBB2. The Blue colored bars denote Normal patient samples, Red colored bars denote patient samples.

Figure 4.

mRNA expresssion validation of BRCA hubgenes (A) PTEN (B) CD44 (C) CXCR4 (D) PROM1 (E) ERBB2. The Blue colored bars denote Normal patient samples, Red colored bars denote patient samples.

Figure 5.

mRNA expresssion validation of CESC hubgenes (A) CD44 (B) PROM1 (C) POU5F1 (D) SOX2 (E) NANOG. The Blue colored bars denote Normal patient samples, Red colored bars denote patient samples.

Figure 5.

mRNA expresssion validation of CESC hubgenes (A) CD44 (B) PROM1 (C) POU5F1 (D) SOX2 (E) NANOG. The Blue colored bars denote Normal patient samples, Red colored bars denote patient samples.

Figure 6.

Survival Analysis of BRCA hub genes.

Figure 6.

Survival Analysis of BRCA hub genes.

Figure 7.

Survival Analysis of CESC hub genes.

Figure 7.

Survival Analysis of CESC hub genes.

Figure 9.

microRNA expression validation using dBDEMC (A) Breast Cancer (B) Cervical Cancer.

Figure 9.

microRNA expression validation using dBDEMC (A) Breast Cancer (B) Cervical Cancer.

Figure 10.

Predicted small molecules regulating expression of microRNAs against (A) mir-1-3p and mir-429 in Breast Cancer and (B) mir-145-5p in Cervical Cancer.

Figure 10.

Predicted small molecules regulating expression of microRNAs against (A) mir-1-3p and mir-429 in Breast Cancer and (B) mir-145-5p in Cervical Cancer.

Figure 11.

Ramachandran Plot Assesment of Homology modelled CXCR4.

Figure 11.

Ramachandran Plot Assesment of Homology modelled CXCR4.

Figure 12.

Di-valinoyl curcumin at the active site of CXCR4.

Figure 12.

Di-valinoyl curcumin at the active site of CXCR4.

Figure 13.

4-(4-hydroxy benzylidene) curcumin at the active site of SOX-2.

Figure 13.

4-(4-hydroxy benzylidene) curcumin at the active site of SOX-2.

Figure 14.

Binding Pose metadynamic Simulation for top 3 docked poses of (A) CXCR4 and (B) SOX-2.

Figure 14.

Binding Pose metadynamic Simulation for top 3 docked poses of (A) CXCR4 and (B) SOX-2.

Figure 15.

Molecular Docking simulation RMSD results (A) CXCR4 complex and (B) SOX-2 Complex.

Figure 15.

Molecular Docking simulation RMSD results (A) CXCR4 complex and (B) SOX-2 Complex.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).