Submitted:

06 April 2023

Posted:

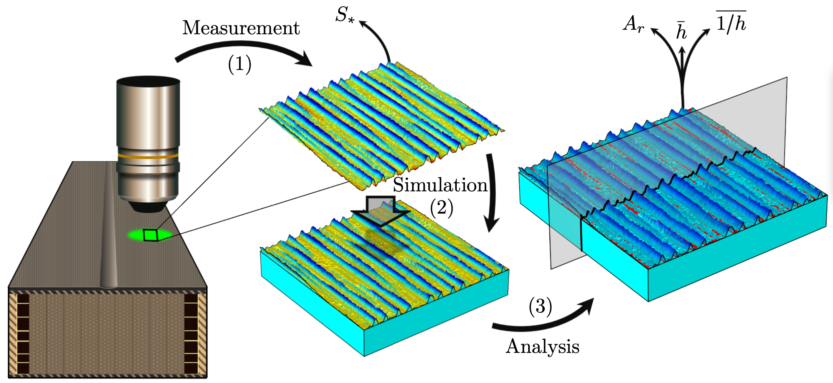

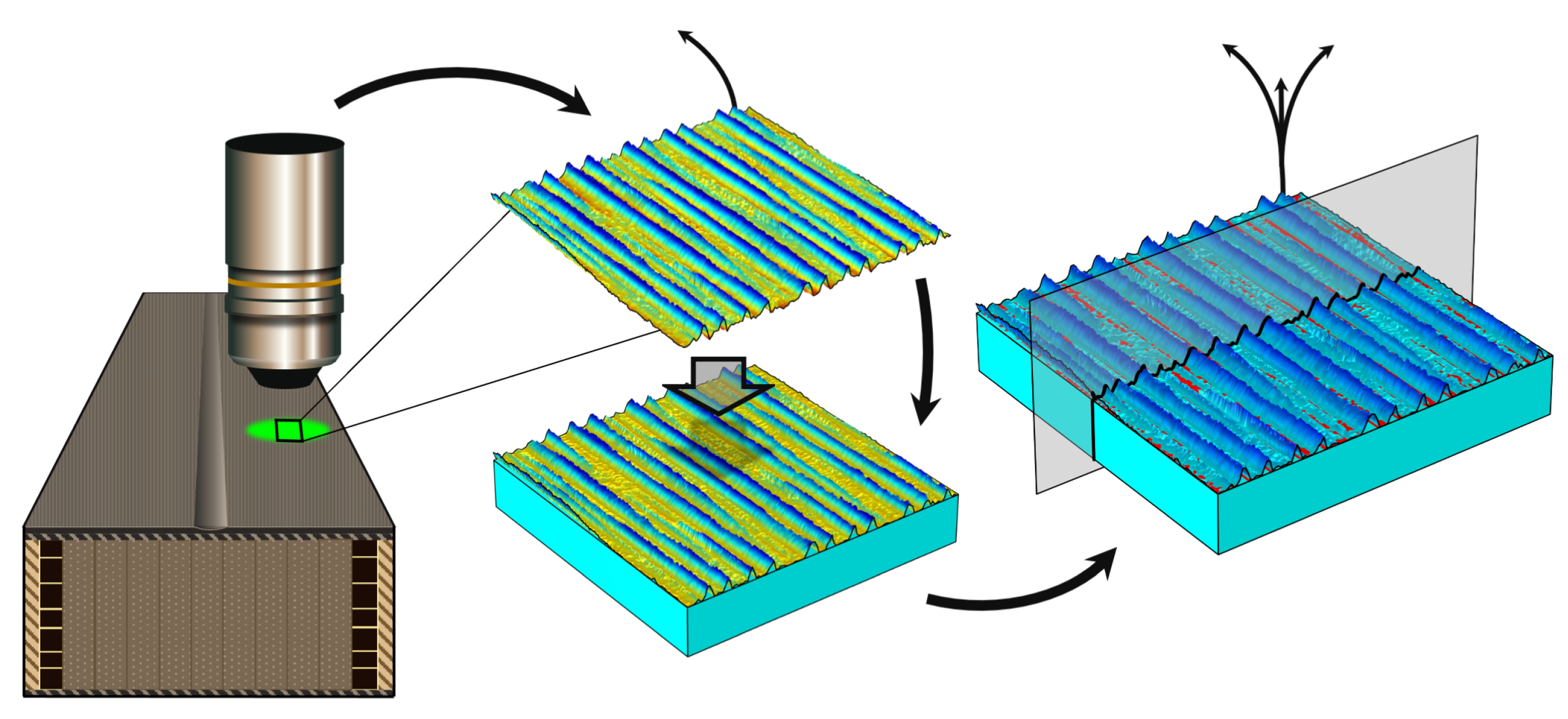

06 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theory

3. Method

| Textures | (m) | (m) | (-) | (-) | (m/mm) | (m) | (m) | (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear 1 | 1.767 | 2.159 | -0.16 | 2.58 | 65.79 | 1.444 | 6.009 | 1.920 |

| Linear 2 | 2.437 | 3.011 | -0.49 | 2.89 | 72.70 | 1.571 | 7.837 | 3.546 |

| Linear 3 | 8.768 | 9.622 | -0.43 | 1.63 | 185.77 | 2.161 | 11.651 | 20.019 |

| Brand A | 4.999 | 6.305 | -1.13 | 3.49 | 168.46 | 1.917 | 9.416 | 13.196 |

| Brand B | 4.881 | 5.803 | -0.58 | 2.38 | 112.82 | 1.217 | 12.695 | 7.965 |

| Steel | 1.693 | 2.126 | -0.09 | 3.34 | 94.25 | 1.925 | 5.499 | 2.149 |

4. Results

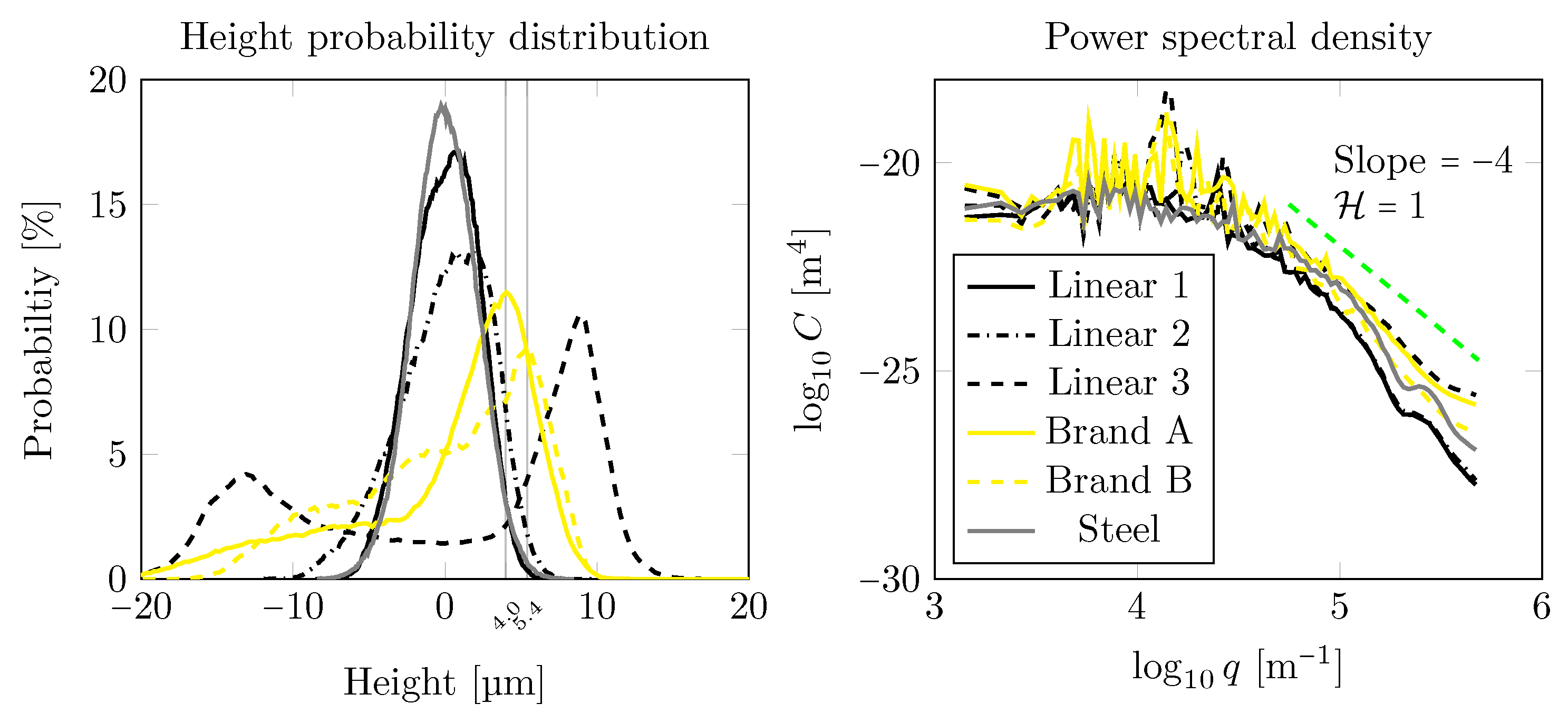

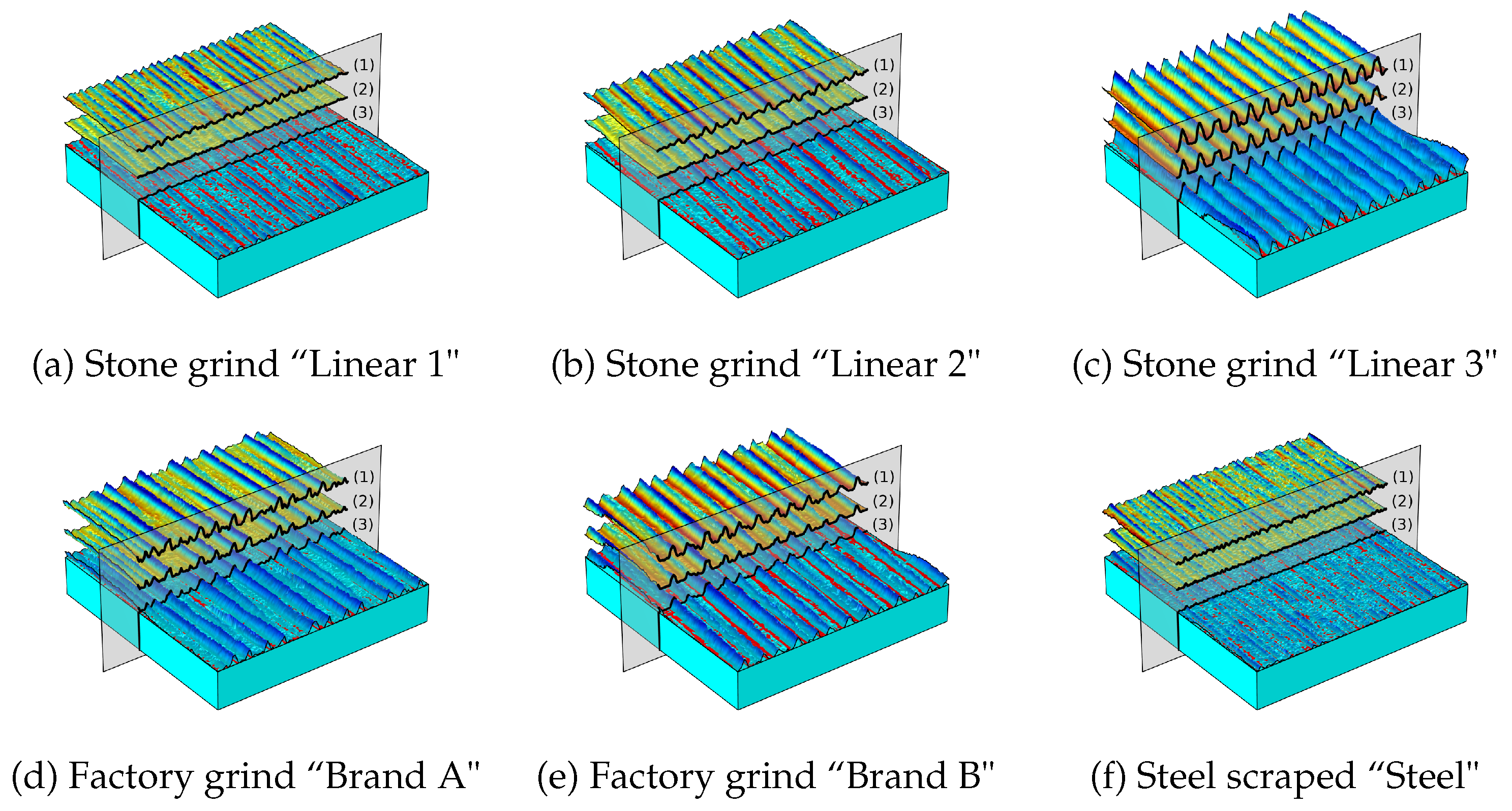

4.1. Standardised Surface Roughness Parameters

4.2. Functional Parameters

4.3. Comparison with Previous Results

4.3.1. Rohm et al. [18]

4.3.2. Scherge et al. [16]

| Textures | (m) | (-) | (-) | (m/mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 linear/fine | 1.86 | 0.41 | 1.68 | 135 |

| S2 linear/medium | 1.63 | 0.54 | 2.83 | 107 |

| S3 linear/coarse | 2.84 | 0.18 | 0.33 | 137 |

| S4 linear/mutliple | 2.45 | 0.29 | 0.70 | 175 |

| S5 cross-hatched | 1.81 | 0.67 | 2.22 | 126 |

| Linear 1 | 1.77 | -0.16 | 2.58 | 66 |

| Linear 2 | 2.44 | -0.49 | 2.89 | 73 |

| Linear 3 | 8.77 | -0.43 | 1.63 | 186 |

| Brand A | 5.00 | -1.13 | 3.49 | 168 |

| Brand B | 4.88 | -0.58 | 2.38 | 113 |

| Steel | 1.69 | -0.09 | 3.34 | 94 |

5. Conclusions

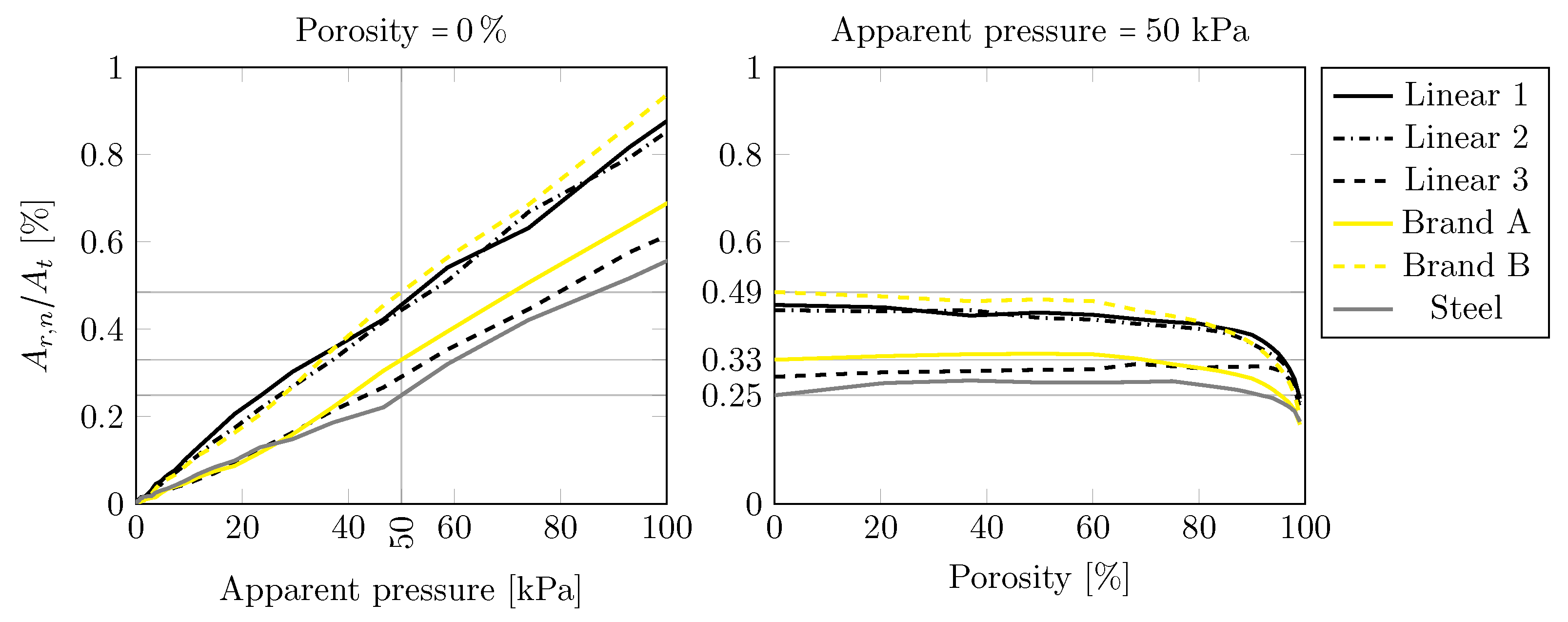

- Surfaces with higher -values have lower contact area, but solely the cannot be used to precisely predict the contact area.

- It was found that an increase in the porosity decreased the real area of contact, and ski-base textures with a larger real area of contact at exhibited a higher variability.

- The surfaces were grouped by their -values and the group with the lower -value showed a higher rate of increase in contact area with increasing apparent pressure.

- The relative differences between the real area of contact for the Linear 3 (“roughest”) and the Steel-scraped surface (“smoothest”), and between the Linear 1 (second “smoothest”) and the Steel-scraped surface at an apparent pressure of 50kPa, were found to be ≈32% and ≈84%, respectively, indicating that the -value is not correlated with the real area of contact.

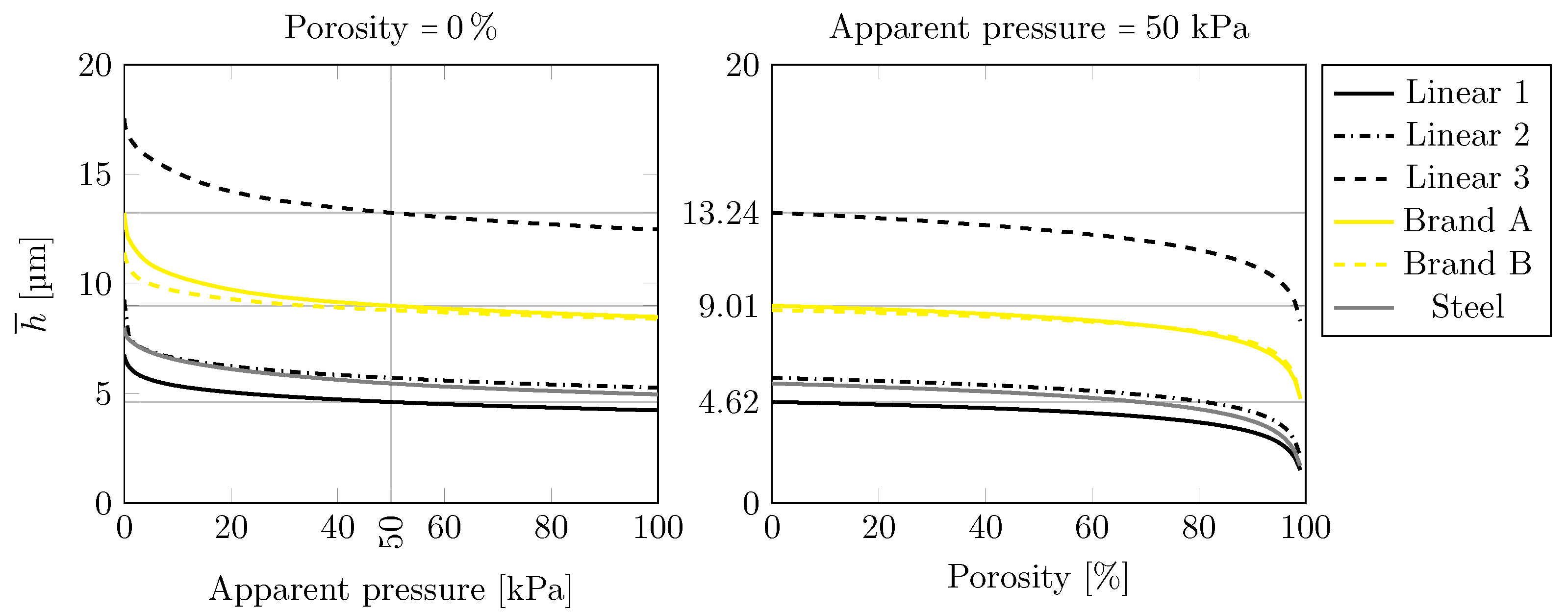

- The differences between the average interfacial separation for the Steel scraped (“smoothest”) and the Linear 3 surfaces (“roughest”), and the Steel scraped (“smoothest”) and the Linear 1 surfaces (second “smoothest”), at a 50kPa apparent pressure, were found to be ≈300% and ≈17%, respectively.

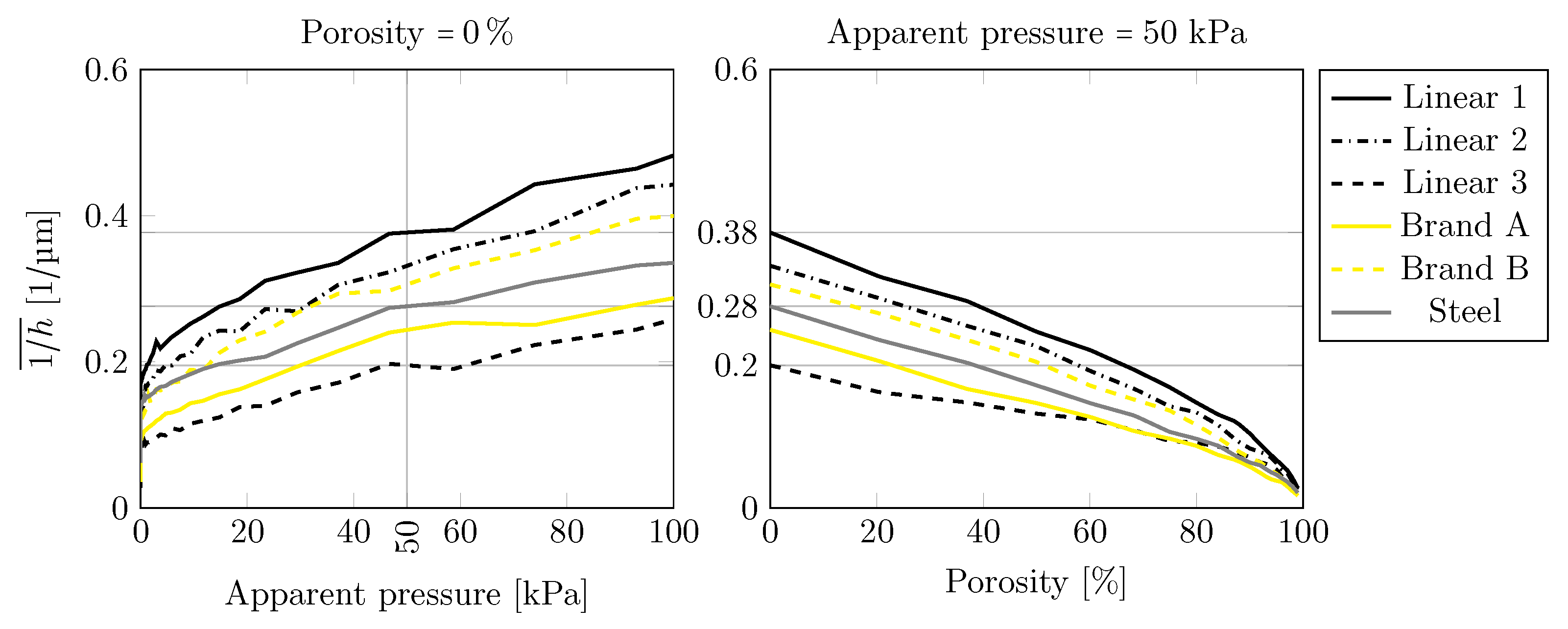

- The reciprocal average interfacial separation, hence the viscous part of the friction, is expected to be ≈50% higher for the Linear 1 than for the Linear 3 texture at a 50kPa apparent pressure.

- The viscous friction is linearly dependent on the velocity and the reciprocal average interfacial separation (), and is larger for the Linear 1 texture than for all the other five surfaces considered here.

- The reciprocal average interfacial separation can be used to compare textures and possibly help to discern whether a texture performs well under warm conditions or not.

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| Nomenclature | ||

| Elastic modulus of ice =9GPa | Pa | |

| Elastic modulus of the ski base =0.9GPa | Pa | |

| Unconfined compressive strength | Pa | |

| Poisson ratio | - | |

| Pore surface area | m2 | |

| Total surface area | m2 | |

| Real area of contact for a non-porous surface | m2 | |

| Real area of contact for a porous surface | m2 | |

| Computational domain | - | |

| The part of the domain where there is contact | - | |

| The part of the domain where there is a gap (not contact) | - | |

| U | Sliding velocity | ms−1 |

| n | Surface porosity | - |

| p | Nominal load | Pa |

| Apparent pressure | Pa | |

| P | Load | N |

| Rigid body displacement | m | |

| h | Interfacial separation | m |

| Average interfacial separation | m | |

| Average reciprocal interfacial separation | m−1 | |

| Surface roughenss parameters | ||

| Root mean square deviation | ||

| Skewness | ||

| Kurtosis | ||

| Root mean square slope | ||

| Reduced peak height | ||

| Core roughness depth | ||

| Reduced valley height | ||

References

- Andreas Almqvist, Barbara Pellegrini, Nina Lintzén, Nazanin Emami, H-C Holmberg, and Roland Larsson. A Scientific Perspective on Reducing Ski-Snow Friction to Improve Performance in Olympic Cross-Country Skiing, the Biathlon and Nordic Combined. Front. Sport. Act. Living 2022, 4, 844883.

- Glenn M. Street and Robert W. Gregory. Relationship between Glide Speed and Olympic Cross-Country Ski Performance. J. Appl. Biomech. 1994, 10, 393–399. ZSCC: 0000022.

- F.P Bowden and T.P. Hughes. The mechanism of sliding on ice and snow. Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1939, 172, 280–298.

- R. Eriksson. Friction of runners on snow and ice. 1949. Document Type: Journal Article.

- F. P. Bowden. Some Recent Experiments in Friction: Friction on Snow and Ice and the Development of some Fast-Running Skis. Nature 1955, 176, 946–947.

- James H. Lever, Emily Asenath-Smith, Susan Taylor, and Austin P. Lines. Assessing the Mechanisms Thought to Govern Ice and Snow Friction and Their Interplay With Substrate Brittle Behavior. Front. Mech. Eng. 2021, 7, 690425.

- B. Glenne. Sliding Friction and Boundary Lubrication of Snow. J. Tribol. 1987, 109, 614–617.

- Lasse Makkonen. Application of a new friction theory to ice and snow. Ann. Glaciol. 1994, 19, 155–157.

- Ramin Aghababaei, Emily E. Brodsky, Jean-François Molinari, and Srinivasan Chandrasekar. How roughness emerges on natural and engineered surfaces. MRS Bulletin, January 2023.

- Arto Lehtovaara. Kinetic friction between ski and snow. January 1989.

- A. Bejan. The Fundamentals of Sliding Contact Melting and Friction. J. Heat Transf. 1989, 111, 13–20.

- Adrian Bejan. Contact Melting Heat Transfer and Lubrication. In Advances in Heat Transfer, volume 24, pages 1–38. Elsevier, 1994.

- Kalle Kalliorinne, Gustav Hindér, Joakim Sandberg, Roland Larsson, Hans-Christer Holmberg, and Andreas Almqvist. The impact of cross-country skiers’ tucking position on ski-camber profile, apparent contact area and load partitioning. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part P: Journal of Sports Engineering and Technology, page 175433712211417, January 2023.

- Kalle Kalliorinne, Joakim Sandberg, Gustav Hindér, Roland Larsson, Hans-Christer Holmberg, and Andreas Almqvist. Characterisation of the Contact between Cross-Country Skis and Snow: A Macro-Scale Investigation of the Apparent Contact. Lubricants 2022, 10, 279.

- James H. Lever, Susan Taylor, Garrett R. Hoch, and Charles Daghlian. Evidence that abrasion can govern snow kinetic friction. J. Glaciol. 2019, 65, 68–84.

- Matthias Scherge, Melissa Stoll, and Michael Moseler. On the influence of microtopography on the sliding performance of cross country skis. Front. Mech. Eng. 2021, 7, 659995.

- Jan L. Giesbrecht, Paul Smith, and Theo A. Tervoort. Polymers on snow: Toward skiing faster. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2010, 48, 1543–1551.

- Sebastian Rohm, Christoph Kno, Michael Hasler, Lukas Kaserer, Joost van Putten, Seraphin H Unterberger, and Roman Lackner. Effect of Different Bearing Ratios on the Friction between Ultrahigh Molecular Weight Polyethylene Ski Bases and Snow. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 6.

- B. N. J. Persson. Functional properties of rough surfaces from an analytical theory of mechanical contact. MRS Bulletin 2022, 47, 1211–1219.

- L. Bäurle, Th.U. Kaempfer, D. Szabó, and N.D. Spencer. Sliding friction of polyethylene on snow and ice: Contact area and modeling. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2007, 47, 276–289.

- T. Theile, D. Szabo, A. Luthi, H. Rhyner, and M. Schneebeli. Mechanics of the Ski–Snow Contact. Tribol. Lett. 2009, 36, 223–231.

- S. Rohm, S.H. Unterberger, M. Hasler, M. Gufler, J. van Putten, R. Lackner, and W. Nachbauer. Wear of ski waxes: Effect of temperature, molecule chain length and position on the ski base. Wear 2017, 384-385, 43–49.

- Martin Mössner, Michael Hasler, and Werner Nachbauer. Calculation of the contact area between snow grains and ski base. Tribol. Int. 2021, 163, 107183.

- S Jolivet, S Mezghani, and M El Mansori. Multiscale analysis of replication technique efficiency for 3D roughness characterization of manufactured surfaces. Surf. Topogr. Metrol. Prop. 2016, 4, 035002.

- A. Almqvist, F. Sahlin, R. Larsson, and S. Glavatskih. On the dry elasto-plastic contact of nominally flat surfaces. Tribology International 2007, 40, 574–579.

- F Sahlin, R Larsson, A Almqvist, P M Lugt, and P Marklund. A mixed lubrication model incorporating measured surface topography. Part 1: Theory of flow factors. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2010, 224, 335–351.

- A. Almqvist, C. Campana, N. Prodanov, and B. N. J. Persson. Interfacial separation between elastic solids with randomly rough surfaces: Comparison between theory and numerical techniques. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2011, 59, 2355–2369.

- A. Tiwari, A. Almqvist, and B. N. J. Persson. Plastic deformation of rough metallic surfaces. Tribol. Lett. 2020, 68.

- Francesc Pérez-Ràfols and Andreas Almqvist. On the stiffness of surfaces with non-Gaussian height distribution. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1863.

- Kalle Kalliorinne, Roland Larsson, Francesc Pérez-Ràfols, Marcus Liwicki, and Andreas Almqvist. Artificial Neural Network Architecture for Prediction of Contact Mechanical Response. Front. Mech. Eng. 2021, 6, 579825.

- E. J. Abbott and F. A. Firestone. Specifying surface quality: A method based on accurate measurement and comparison. J. Mech. Eng. 1933, 569–572.

- University of Michigan. College of Engineering. College of engineering: Announcement 1934–1935 and 1935–1936. 1934, 35.

- B. N. J. Persson. Contact mechanics for randomly rough surfaces. Surface Science Reports 2006, 61, 201–227, 2006.

- B. N. J. Persson. Relation between interfacial separation and load: A general theory of contact mechanics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 99, 125502.

- C Yang and B N J Persson. Contact mechanics: contact area and interfacial separation from small contact to full contact. J. Physics Condens. Matter 2008, 20, 215214.

- Toshi Tada, Satoshi Kawasaki, Ryouske Shimizu, and Bo N. J. Persson. Rubber-ice friction. Friction, 2023.

| 1 | The temperature of the ice cave where they performed measurements never rose above −3 °C |

| 2 | The stone that grinds the ski is textured by a dressing procedure, where a diamond tip is swept from one side of the rotating stone to the other. Hence, the texture will not be perfectly longitudinal. Instead, it will exhibit a small lay (compare with the thread in a screw), which will be reflected in the ski-base texture after grinding. |

| 3 | These factory-ground ski-base textures are meant to be “universal”, implying that they should provide satisfactory performance in many different conditions. |

| 4 | When steel scraping the ski base, a scraper made of steel with a sharp edge is repeatedly used to cut away a very thin layer of material from the ski base. |

| 5 | A stochastic variable with is said to have a leptokurtic distribution, and a randomly rough (gaussian) surface has a . |

| 6 | Notice that there will be two competing effects, i.e., the film thickness and the area covered by the meltwater. For rubber on a glass surface (e.g. wiper blades), the friction is maximal just before dry contact occurs due to water evaporation, see [36] for more about rubber friction. In the ski–snow interface the former will likely dominate, hence the strongest capillary effect is just when a meltwater film starts to appear |

| Textures | (m) | (m) | (m) | (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

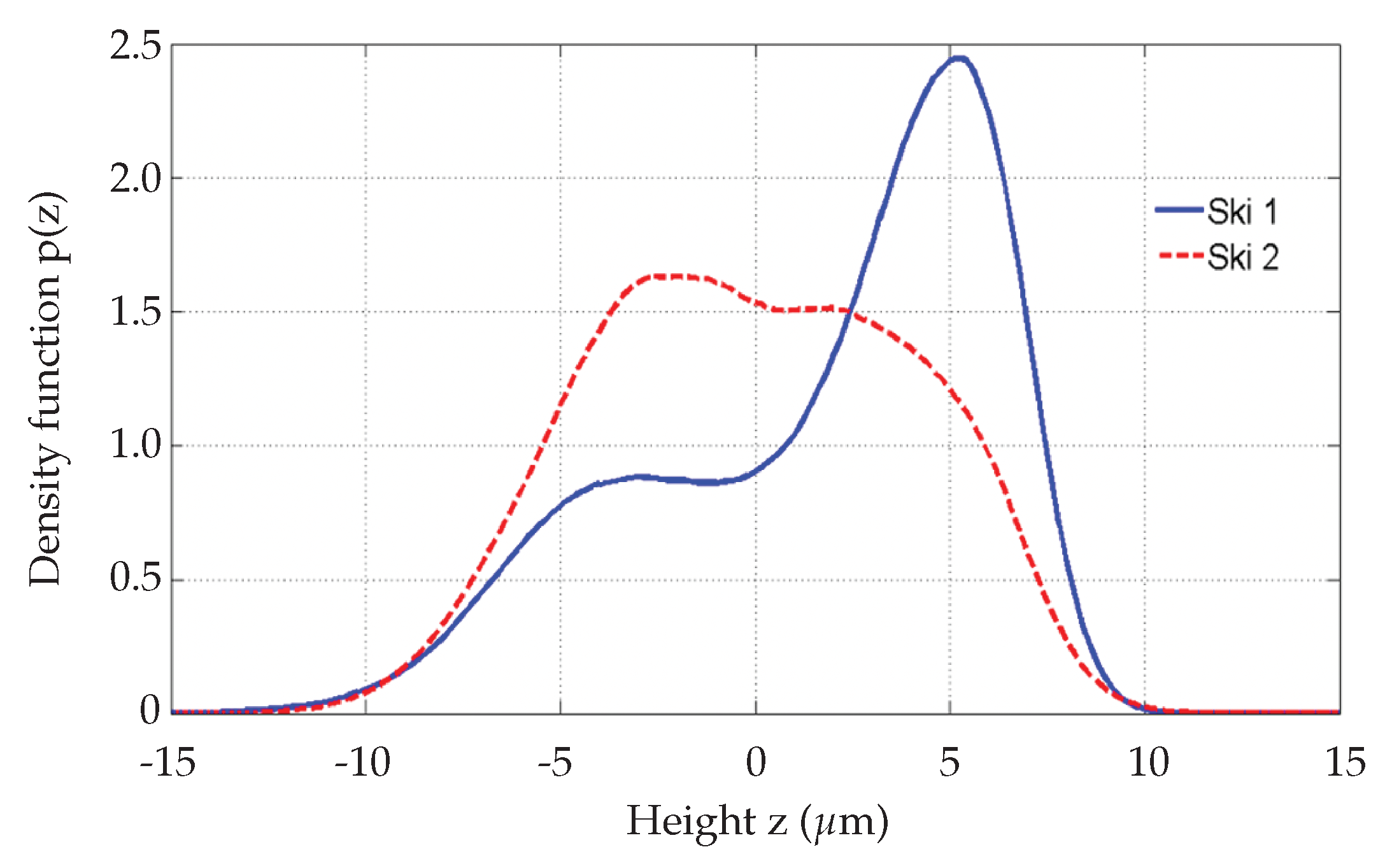

| Ski 1 | 3.60 | 1.40 | 9.00 | 6.55 |

| Ski 2 | 3.48 | 2.20 | 12.60 | 2.80 |

| Linear 1 | 1.77 | 1.44 | 6.01 | 1.92 |

| Linear 2 | 2.44 | 1.57 | 7.84 | 3.55 |

| Linear 3 | 8.77 | 2.16 | 11.65 | 20.02 |

| Brand A | 5.00 | 1.92 | 9.42 | 13.20 |

| Brand B | 4.88 | 1.22 | 12.70 | 7.97 |

| Steel | 1.69 | 1.93 | 5.50 | 2.15 |

| Textures | (m) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ski 1 | 8.3% | 53.1% | 38.6% | 72.8% | 16.95 |

| Ski 2 | 12.5% | 71.6% | 15.9% | 22.2% | 17.60 |

| % Linear 1 | 15.4% | 64.1% | 20.5% | 32.0% | 9.37 |

| Linear 2 | 12.1% | 60.5% | 27.4% | 45.2% | 12.95 |

| Linear 3 | 6.4% | 34.4% | 59.2% | 171.8% | 33.83 |

| Brand A | 7.8% | 38.4% | 53.8% | 140.1% | 24.53 |

| Brand B | 5.6% | 58.0% | 36.4% | 62.7% | 21.88 |

| Steel | 20.1% | 57.4% | 22.4% | 39.1% | 9.57 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).