Submitted:

21 April 2023

Posted:

23 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

30 years of the amyloid cascade hypothesis

Mutations are more likely to destroy function than improve it

The current “understanding” of fAD genetics

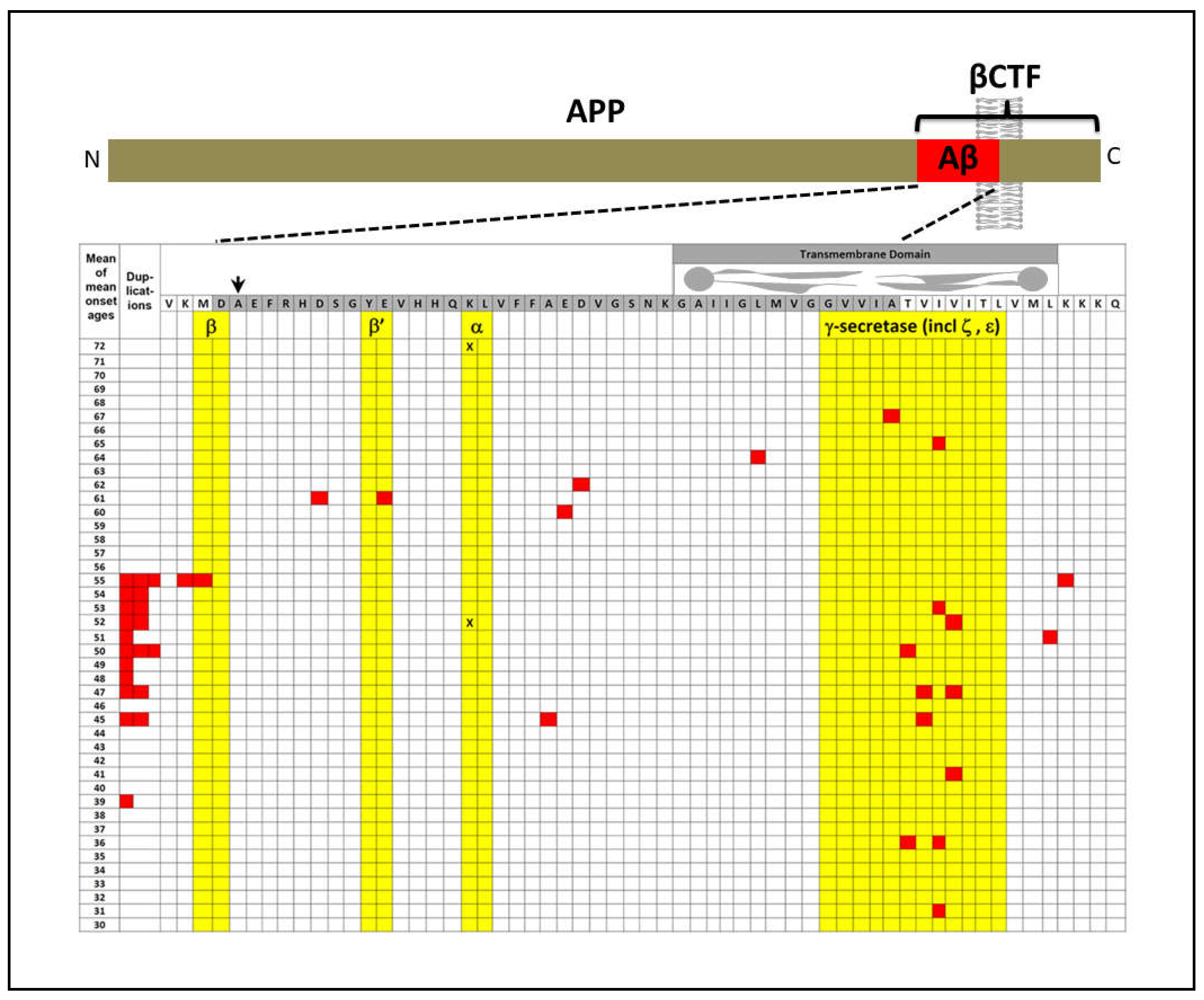

APP

The explanatory power of increased βCTF levels as the AD-causative effect of mutations in APP

The original amyloid cascade hypothesis included βCTF as a candidate pathogenic agent

“Our cascade hypothesis states that AβP itself, or APP cleavage products containing

AβP, are neurotoxic and lead to neurofibrillary tangle formation and cell death. Thus, two successive events are needed to produce Alzheimer's pathology. First, AβP must be generated as an intact entity, either by accumulation of AβP or as an AβP-containing fragment of APP. Second, this molecule must facilitate or cause neuronal death and neurofibrillary tangle formation. Neve and her colleagues have reported that the AβP-containing COOH-terminal fragment is toxic to cultured neurons(18)…

“… The evidence we have described supports the hypothesis that the AβP molecule initiates the pathological cascade of Alzheimer's disease. AβP-containing COOH-terminal derivatives of APP seem the most likely molecular candidates for initiation of the cascade, with the process presumably taking several decades to produce the full-blown pathology of the disease.”

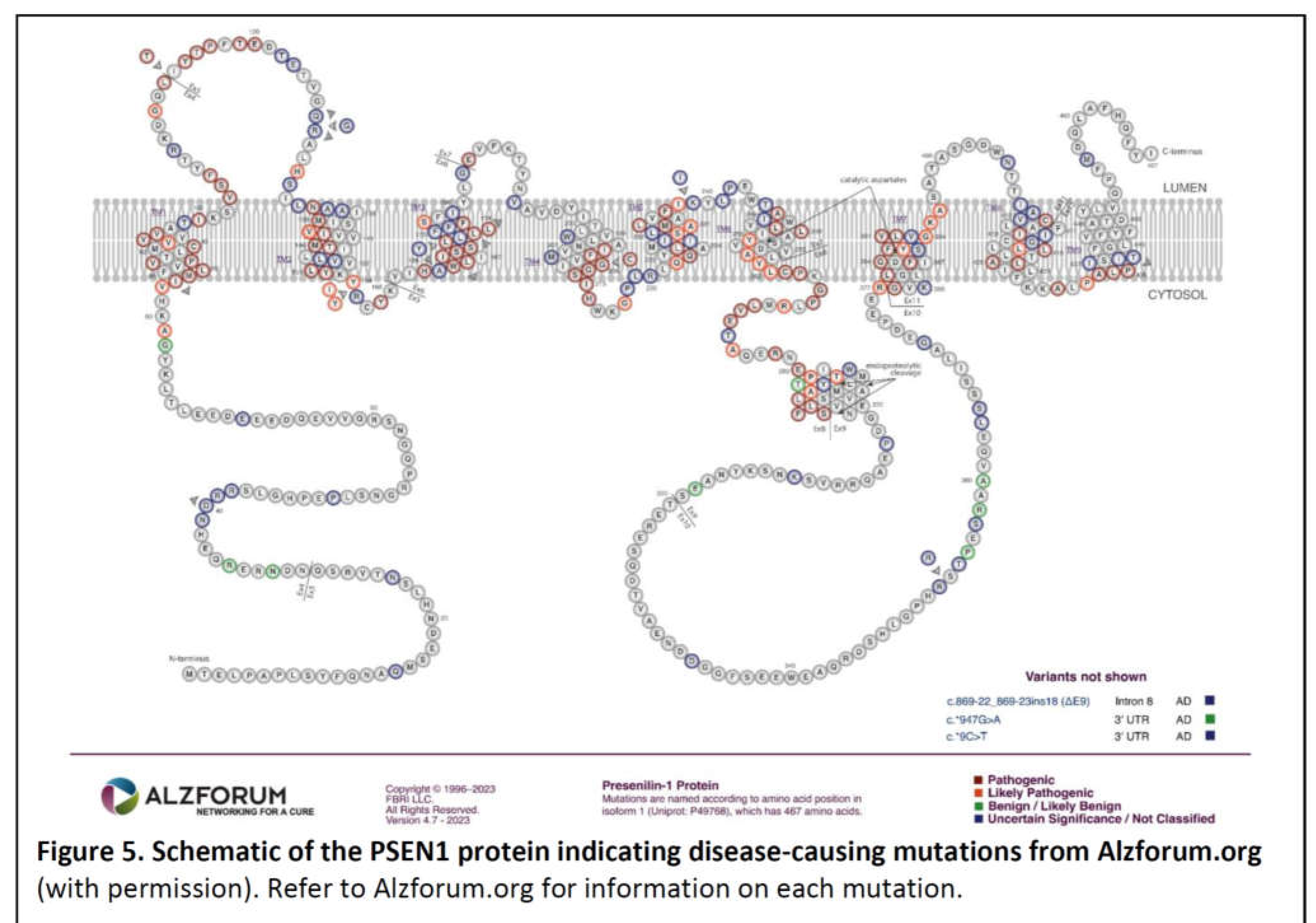

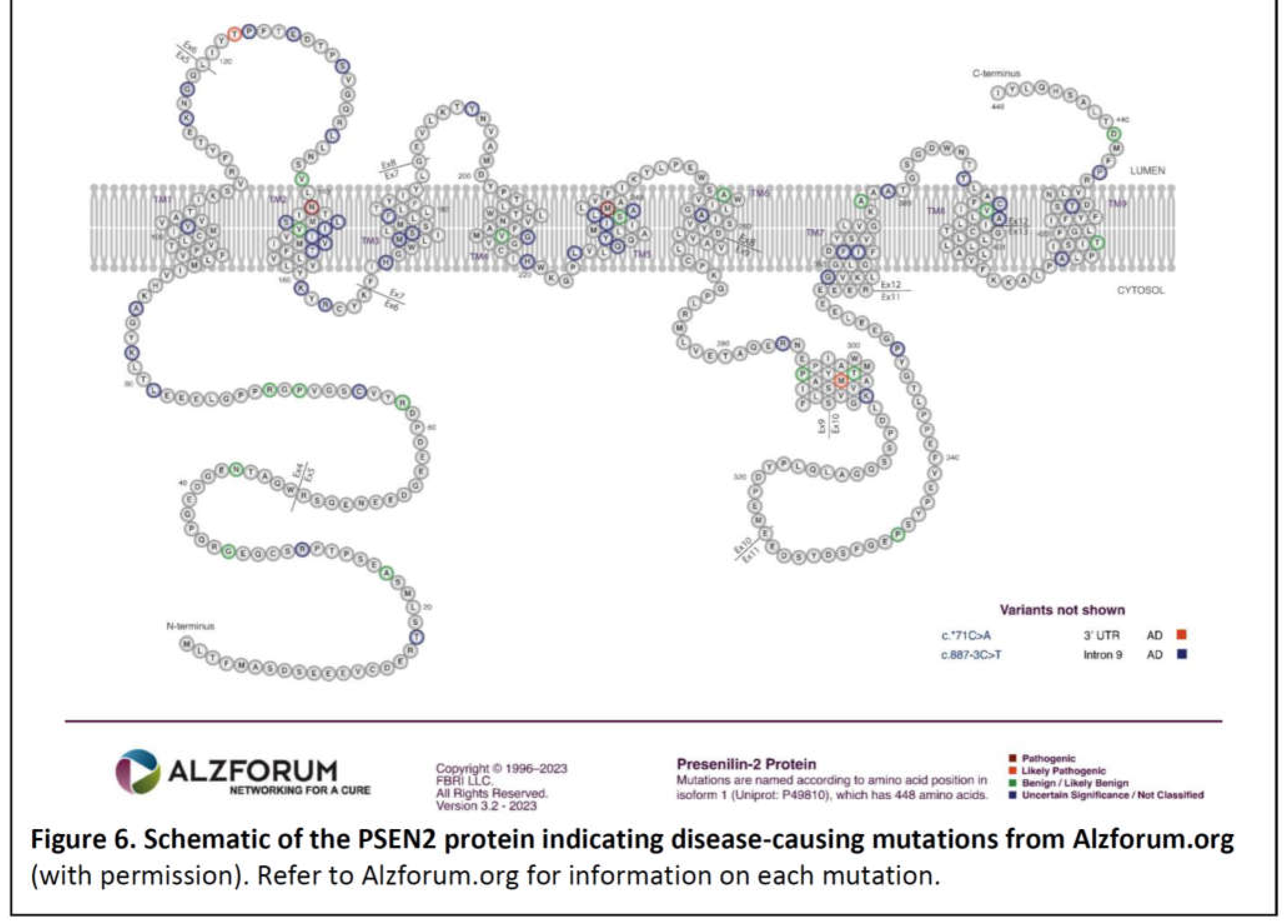

PSEN1 and PSEN2

- 1)

- The great majority of fAD mutations in PSEN1 and PSEN2 are missense mutations altering the protein coding sequence. Even those mutations causing changes in transcript splicing (e.g. PSEN1 L113_I114insT [90]) always produce at least one transcript form that preserves the open reading frame to code for a “full-length” protein. We addressed this issue in a previous review [16], describing it as the reading-frame preservation rule. Consistent with this (with the exception of one unique and important gain-of-function mutation discussed later [91]), no mutations or genetic variants affecting PSEN1 or PSEN2 transcript regulation (without changing protein-coding sequences) have been discovered that increase the risk of AD [92].

- 2)

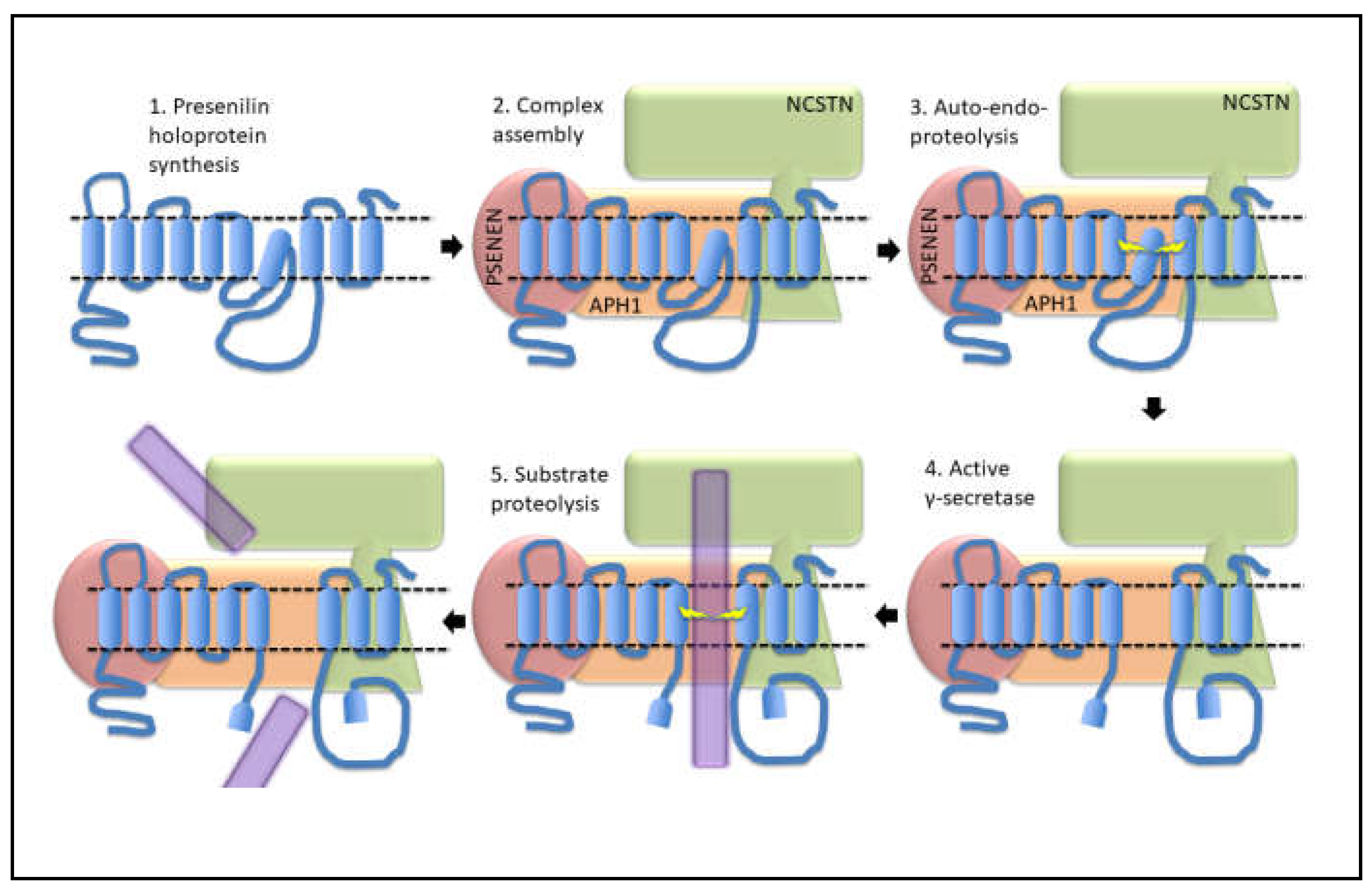

- Loss-of-function mutations that would be expected simply to reduce γ-secretase activity, without otherwise distorting it, do not cause fAD. This is dramatically illustrated by the existence of frameshift mutations in PSEN1 that truncate the open reading frame and do not cause fAD while causing a completely unrelated disease of the skin, Acne Inversa, familial 3, (ACNINV3, also known as hidradenitis suppurativa) [93,94,95]. Unlike fAD, familial Acne Inversa can also be caused by mutations in genes encoding two other components of the γ-secretase enzyme complex, NICASTRIN (NCSTN), and PRESENILIN ENHANCER, GAMMA-SECRETASE SUBUNIT (PSENEN, formerly known as PEN2) [93] (See also Figure 7). All these mutations affecting different components of the γ-secretase enzyme complex almost certainly act through reduction of cellular γ-secretase activity but mutations causing fAD only occur in PSEN1 and PSEN2 and not in genes encoding other γ-secretase complex components. Therefore, fAD cannot be due to a simple loss of γ-secretase activity. The reading frame preservation rule implies that a gain-of-function mechanism is involved.

Presenilin Holoproteins

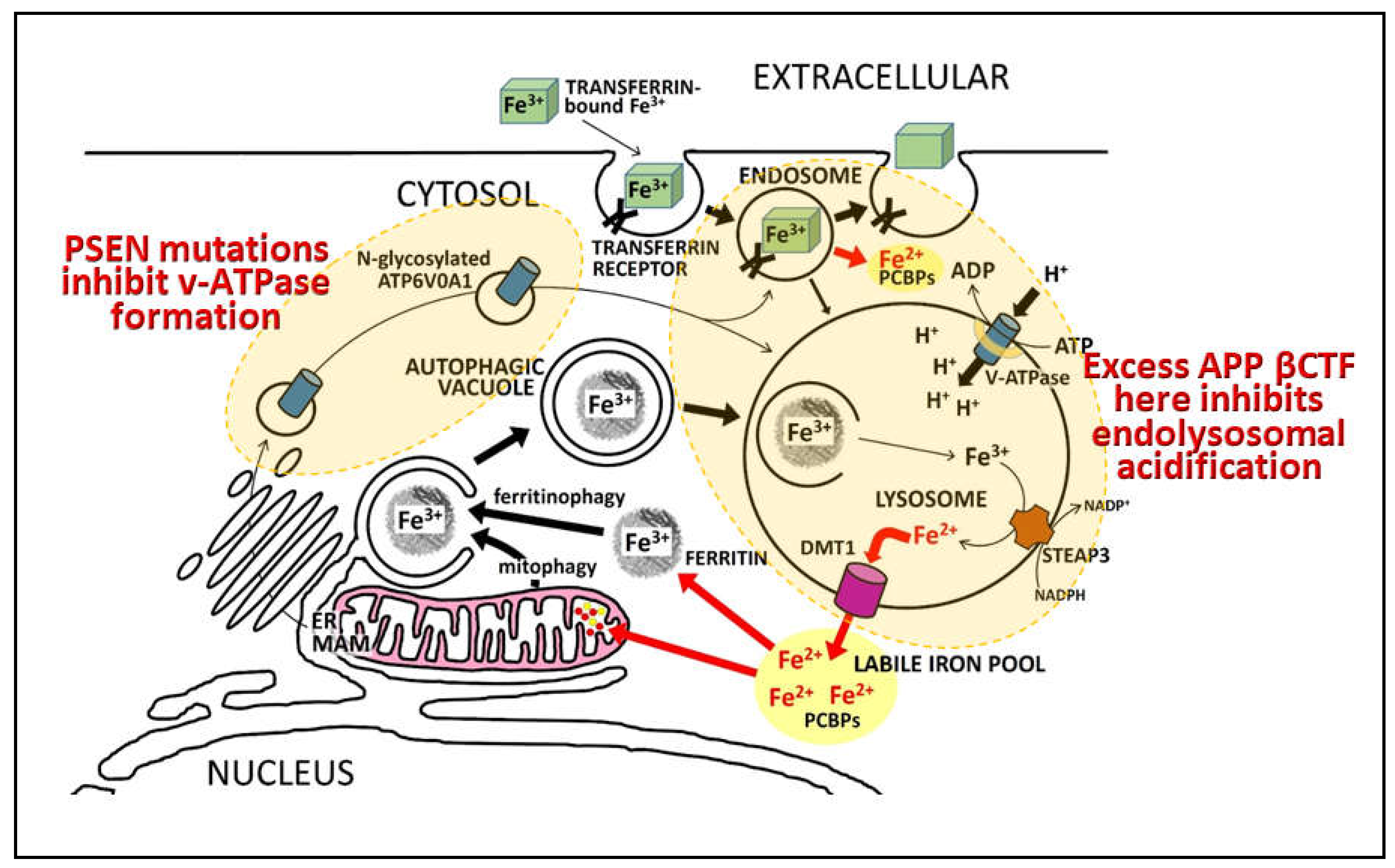

“…identified a direct physical interaction of lysosomal-associated APP-βCTF with the cytosol-exposed domain of the transmembrane V0a1 subunit of the vATPase. Competition by APP-βCTF with specific V1 subunits for binding to the V0a1 subunit impedes association of the V1 and V0 sectors of the complex….Impaired vATPase assembly … is rescued by specifically lowering APP-βCTF levels”

Presenilin holoproteins and/or γ-secretase complexes form multimers

“To gain a better understanding of the moderate dominant negative effect, the expression level of the WT and mutant PSEN1 alleles, as well as the oligomerization state of γ-secretases, should be carefully examined under in vivo circumstances, especially in patients’ brains.”

“We wish to stress that our experimental data provide no supporting evidence for a potential role of γ-secretase in the development of AD. In fact, a number of the γ-secretase variants with pathogenic PS1 mutations, exemplified by S365A, have WT-level proteolytic activity in terms of Aβ42 and Aβ40 production (18). The development of AD in the patients with these PS1 mutations cannot be explained by the WT-level proteolytic activity of these γ-secretase variants in vitro. Nonetheless, the dominant negative effect of these PS1 mutations in patients with AD still applies, suggesting such an effect may not be recapitulated by the catalytic function of PS1 in γ-secretase. We speculate that, for the vast majority of patients with AD, the dominant negative effect of PS1 is perhaps effected through other mechanisms that are independent of γ-secretase.”

A parsimonious model to account for superficially inconsistent/conflicting presenilin mutation data

Additional evidence consistent with increased γ-secretase activity due to fAD mutations

Notes on the importance of iron and hypoxia in fAD pathogenesis

What is APP’s role in iron homeostasis?

Predictions arising from these proposed mechanisms

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest Statement

References

- Lumsden, A.L.; Rogers, J.T.; Majd, S.; Newman, M.; Sutherland, G.T.; Verdile, G.; Lardelli, M. Dysregulation of Neuronal Iron Homeostasis as an Alternative Unifying Effect of Mutations Causing Familial Alzheimer's Disease. Frontiers in neuroscience 2018, 12, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petit, D.; Fernandez, S.G.; Zoltowska, K.M.; Enzlein, T.; Ryan, N.S.; O'Connor, A.; Szaruga, M.; Hill, E.; Vandenberghe, R.; Fox, N.C.; et al. Abeta profiles generated by Alzheimer's disease causing PSEN1 variants determine the pathogenicity of the mutation and predict age at disease onset. Molecular psychiatry 2022, 27, 2821–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gama Sosa, M.A.; Gasperi, R.D.; Rocher, A.B.; Wang, A.C.; Janssen, W.G.; Flores, T.; Perez, G.M.; Schmeidler, J.; Dickstein, D.L.; Hof, P.R.; et al. Age-related vascular pathology in transgenic mice expressing presenilin 1-associated familial Alzheimer's disease mutations. The American journal of pathology 2010, 176, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berchtold, N.C.; Sabbagh, M.N.; Beach, T.G.; Kim, R.C.; Cribbs, D.H.; Cotman, C.W. Brain gene expression patterns differentiate mild cognitive impairment from normal aged and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiology of aging 2014, 35, 1961–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donertas, H.M.; Izgi, H.; Kamacioglu, A.; He, Z.; Khaitovich, P.; Somel, M. Gene expression reversal toward pre-adult levels in the aging human brain and age-related loss of cellular identity. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 5894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, J.A.; Varma, V.R.; An, Y.; Varma, S.; Candia, J.; Fantoni, G.; Tiwari, V.; Anerillas, C.; Williamson, A.; Saito, A.; et al. A brain proteomic signature of incipient Alzheimer's disease in young APOE epsilon4 carriers identifies novel drug targets. Sci Adv 2021, 7, eabi8178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutphen, C.L.; McCue, L.; Herries, E.M.; Xiong, C.; Ladenson, J.H.; Holtzman, D.M.; Fagan, A.M.; Adni. Longitudinal decreases in multiple cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of neuronal injury in symptomatic late onset Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association 2018, 14, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, S.; Spampinato, S.F.; Sortino, M.A. Early compensatory responses against neuronal injury: A new therapeutic window of opportunity for Alzheimer's Disease? CNS neuroscience & therapeutics 2019, 25, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, J.A.; Higgins, G.A. Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science 1992, 256, 184–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, J.A.; Bainbridge, T.; Gustafson, A.; Zhang, S.; Kyauk, R.; Steiner, P.; van der Brug, M.; Liu, Y.; Ernst, J.A.; Watts, R.J.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of Alzheimer disease protection by the A673T allele of amyloid precursor protein. The Journal of biological chemistry 2014, 289, 30990–31000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.S.; Naj, A.C.; Graham, R.R.; Crane, P.K.; Kunkle, B.W.; Cruchaga, C.; Murcia, J.D.; Cannon-Albright, L.; Baldwin, C.T.; Zetterberg, H.; et al. Rarity of the Alzheimer disease-protective APP A673T variant in the United States. JAMA Neurol 2015, 72, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, S.K.; Chong, M.S.; Kandiah, N.; Hameed, S.; Tan, L.; Au, W.L.; Prakash, K.M.; Pavanni, R.; Lee, T.S.; Foo, J.N.; et al. Absence of A673T amyloid-beta precursor protein variant in Alzheimer's disease and other neurological diseases. Neurobiology of aging 2013, 34, 2441–e2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengel-From, J.; Jeune, B.; Pentti, T.; McGue, M.; Christensen, K.; Christiansen, L. The APP A673T frequency differs between Nordic countries. Neurobiology of aging 2015, 36, 2909–e2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kero, M.; Paetau, A.; Polvikoski, T.; Tanskanen, M.; Sulkava, R.; Jansson, L.; Myllykangas, L.; Tienari, P.J. Amyloid precursor protein (APP) A673T mutation in the elderly Finnish population. Neurobiology of aging 2013, 34, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamne, M.N.; Demirci, F.Y.; Berman, S.; Snitz, B.E.; Rosenthal, S.L.; Wang, X.; Lopez, O.L.; Kamboh, M.I. Investigation of an amyloid precursor protein protective mutation (A673T) in a North American case-control sample of late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiology of aging 2014, 35, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayne, T.; Newman, M.; Verdile, G.; Sutherland, G.; Munch, G.; Musgrave, I.; Moussavi Nik, S.H.; Lardelli, M. Evidence For and Against a Pathogenic Role of Reduced gamma-Secretase Activity in Familial Alzheimer's Disease. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD 2016, 52, 781–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pottier, C.; Hannequin, D.; Coutant, S.; Rovelet-Lecrux, A.; Wallon, D.; Rousseau, S.; Legallic, S.; Paquet, C.; Bombois, S.; Pariente, J.; et al. High frequency of potentially pathogenic SORL1 mutations in autosomal dominant early-onset Alzheimer disease. Molecular psychiatry 2012, 17, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheijen, J.; Van den Bossche, T.; van der Zee, J.; Engelborghs, S.; Sanchez-Valle, R.; Llado, A.; Graff, C.; Thonberg, H.; Pastor, P.; Ortega-Cubero, S.; et al. A comprehensive study of the genetic impact of rare variants in SORL1 in European early-onset Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol 2016, 132, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellenguez, C.; Charbonnier, C.; Grenier-Boley, B.; Quenez, O.; Le Guennec, K.; Nicolas, G.; Chauhan, G.; Wallon, D.; Rousseau, S.; Richard, A.C.; et al. Contribution to Alzheimer's disease risk of rare variants in TREM2, SORL1, and ABCA7 in 1779 cases and 1273 controls. Neurobiology of aging 2017, 59, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthelson, K.; Newman, M.; Lardelli, M. Sorting Out the Role of the Sortilin-Related Receptor 1 in Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis Rep 2020, 4, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortea, J.; Zaman, S.H.; Hartley, S.; Rafii, M.S.; Head, E.; Carmona-Iragui, M. Alzheimer's disease associated with Down syndrome: a genetic form of dementia. The Lancet. Neurology 2021, 20, 930–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rovelet-Lecrux, A.; Hannequin, D.; Raux, G.; Le Meur, N.; Laquerrière, A.; Vital, A.; Dumanchin, C.; Feuillette, S.; Brice, A.; Vercelletto, M.; et al. APP locus duplication causes autosomal dominant early-onset Alzheimer disease with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Nature genetics 2006, 38, 24–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, T.H.; Yan, Y.; Kang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Melcher, K.; Xu, H.E. Alzheimer's disease-associated mutations increase amyloid precursor protein resistance to gamma-secretase cleavage and the Abeta42/Abeta40 ratio. Cell Discov 2016, 2, 16026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haass, C.; Hung, A.Y.; Selkoe, D.J.; Teplow, D.B. Mutations associated with a locus for familial Alzheimer's disease result in alternative processing of amyloid beta-protein precursor. The Journal of biological chemistry 1994, 269, 17741–17748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Brouwers, N.; Benilova, I.; Vandersteen, A.; Mercken, M.; Van Laere, K.; Van Damme, P.; Demedts, D.; Van Leuven, F.; Sleegers, K.; et al. Amyloid precursor protein mutation E682K at the alternative beta-secretase cleavage beta'-site increases Abeta generation. EMBO Mol Med 2011, 3, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullan, M.; Crawford, F.; Axelman, K.; Houlden, H.; Lilius, L.; Winblad, B.; Lannfelt, L. A pathogenic mutation for probable Alzheimer's disease in the APP gene at the N-terminus of beta-amyloid. Nature genetics 1992, 1, 345–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, X.D.; Golde, T.E.; Younkin, S.G. Release of excess amyloid beta protein from a mutant amyloid beta protein precursor. Science 1993, 259, 514–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Sato, Y.; Im, E.; Berg, M.; Bordi, M.; Darji, S.; Kumar, A.; Mohan, P.S.; Bandyopadhyay, U.; Diaz, A.; et al. Lysosomal Dysfunction in Down Syndrome Is APP-Dependent and Mediated by APP-betaCTF (C99). The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2019, 39, 5255–5268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.T.; Hong, C.J.; Lin, Y.T.; Chang, W.H.; Huang, H.T.; Liao, J.Y.; Chang, Y.J.; Hsieh, Y.F.; Cheng, C.Y.; Liu, H.C.; et al. Amyloid-beta (Abeta) D7H mutation increases oligomeric Abeta42 and alters properties of Abeta-zinc/copper assemblies. PloS one 2012, 7, e35807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugiani, O.; Giaccone, G.; Rossi, G.; Mangieri, M.; Capobianco, R.; Morbin, M.; Mazzoleni, G.; Cupidi, C.; Marcon, G.; Giovagnoli, A.; et al. Hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis associated with the E693K mutation of APP. Archives of neurology 2010, 67, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliavini, J.; Williot, P.; Congiu, L.; Chicca, M.; Lanfredi, M.; Rossi, R.; Fontana, F. Molecular cytogenetic analysis of the karyotype of the European Atlantic sturgeon, Acipenser sturio. Heredity (Edinb) 1999, 83 ( Pt 5) Pt 5, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obici, L.; Demarchi, A.; de Rosa, G.; Bellotti, V.; Marciano, S.; Donadei, S.; Arbustini, E.; Palladini, G.; Diegoli, M.; Genovese, E.; et al. A novel AbetaPP mutation exclusively associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Annals of neurology 2005, 58, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haapasalo, A.; Kovacs, D.M. The many substrates of presenilin/gamma-secretase. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD 2011, 25, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guner, G.; Lichtenthaler, S.F. The substrate repertoire of gamma-secretase/presenilin. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2020, 105, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Xu, T.H.; Melcher, K.; Xu, H.E. Defining the minimum substrate and charge recognition model of gamma-secretase. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2017, 38, 1412–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takami, M.; Nagashima, Y.; Sano, Y.; Ishihara, S.; Morishima-Kawashima, M.; Funamoto, S.; Ihara, Y. gamma-Secretase: successive tripeptide and tetrapeptide release from the transmembrane domain of beta-carboxyl terminal fragment. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2009, 29, 13042–13052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi-Takahara, Y.; Morishima-Kawashima, M.; Tanimura, Y.; Dolios, G.; Hirotani, N.; Horikoshi, Y.; Kametani, F.; Maeda, M.; Saido, T.C.; Wang, R.; et al. Longer forms of amyloid beta protein: implications for the mechanism of intramembrane cleavage by gamma-secretase. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2005, 25, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Gutierrez, L.; Bammens, L.; Benilova, I.; Vandersteen, A.; Benurwar, M.; Borgers, M.; Lismont, S.; Zhou, L.; Van Cleynenbreugel, S.; Esselmann, H.; et al. The mechanism of gamma-Secretase dysfunction in familial Alzheimer disease. The EMBO journal 2012, 31, 2261–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Mao, G.; Cui, M.Z.; Kang, S.C.; Lamb, B.; Wong, B.S.; Sy, M.S.; Xu, X. Effects of gamma-secretase cleavage-region mutations on APP processing and Abeta formation: interpretation with sequential cleavage and alpha-helical model. Journal of neurochemistry 2008, 107, 722–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Calvet, M.; Belbin, O.; Pera, M.; Badiola, N.; Magrane, J.; Guardia-Laguarta, C.; Munoz, L.; Colom-Cadena, M.; Clarimon, J.; Lleo, A. Autosomal-dominant Alzheimer's disease mutations at the same codon of amyloid precursor protein differentially alter Abeta production. Journal of neurochemistry 2014, 128, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrett, J.T.; Lansbury, P.T., Jr. Seeding "one-dimensional crystallization" of amyloid: a pathogenic mechanism in Alzheimer's disease and scrapie? Cell 1993, 73, 1055–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamaoka, A.; Odaka, A.; Ishibashi, Y.; Usami, M.; Sahara, N.; Suzuki, N.; Nukina, N.; Mizusawa, H.; Shoji, S.; Kanazawa, I.; et al. APP717 missense mutation affects the ratio of amyloid beta protein species (A beta 1-42/43 and a beta 1-40) in familial Alzheimer's disease brain. The Journal of biological chemistry 1994, 269, 32721–32724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchelt, D.R.; Thinakaran, G.; Eckman, C.B.; Lee, M.K.; Davenport, F.; Ratovitsky, T.; Prada, C.M.; Kim, G.; Seekins, S.; Yager, D.; et al. Familial Alzheimer's disease-linked presenilin 1 variants elevate Abeta1-42/1-40 ratio in vitro and in vivo. Neuron 1996, 17, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenthaler, S.F.; Ida, N.; Multhaup, G.; Masters, C.L.; Beyreuther, K. Mutations in the transmembrane domain of APP altering gamma-secretase specificity. Biochemistry 1997, 36, 15396–15403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naslund, J.; Schierhorn, A.; Hellman, U.; Lannfelt, L.; Roses, A.D.; Tjernberg, L.O.; Silberring, J.; Gandy, S.E.; Winblad, B.; Greengard, P.; et al. Relative abundance of Alzheimer A beta amyloid peptide variants in Alzheimer disease and normal aging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1994, 91, 8378–8382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheuner, D.; Eckman, C.; Jensen, M.; Song, X.; Citron, M.; Suzuki, N.; Bird, T.D.; Hardy, J.; Hutton, M.; Kukull, W.; et al. Secreted amyloid beta-protein similar to that in the senile plaques of Alzheimer's disease is increased in vivo by the presenilin 1 and 2 and APP mutations linked to familial Alzheimer's disease. Nature medicine 1996, 2, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citron, M.; Westaway, D.; Xia, W.; Carlson, G.; Diehl, T.; Levesque, G.; Johnson-Wood, K.; Lee, M.; Seubert, P.; Davis, A.; et al. Mutant presenilins of Alzheimer's disease increase production of 42-residue amyloid beta-protein in both transfected cells and transgenic mice. Nature medicine 1997, 3, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayadev, S.; Leverenz, J.B.; Steinbart, E.; Stahl, J.; Klunk, W.; Yu, C.E.; Bird, T.D. Alzheimer's disease phenotypes and genotypes associated with mutations in presenilin 2. Brain : a journal of neurology 2010, 133, 1143–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimon, M.; Takeda, S.; Post, K.L.; Svirsky, S.; Hyman, B.T.; Berezovska, O. Oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation are upstream of amyloid pathology. Neurobiology of disease 2015, 84, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Raina, A.K.; Perry, G.; Smith, M.A. Alzheimer's disease: the two-hit hypothesis. The Lancet. Neurology 2004, 3, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.N.; Harper, C.G.; Stokes, G.B.; Masters, C.L. Increased cerebral glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity in Alzheimer's disease may reflect oxidative stress. Journal of neurochemistry 1986, 46, 1042–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, O.; Paturi, S.; Ye, W.; Wolfe, M.S.; Selkoe, D.J. Effects of membrane lipids on the activity and processivity of purified gamma-secretase. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 3565–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Mittendorf, K.F.; Lu, Z.; Sanders, C.R. Impact of bilayer lipid composition on the structure and topology of the transmembrane amyloid precursor C99 protein. J Am Chem Soc 2014, 136, 4093–4096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montesinos, J.; Pera, M.; Larrea, D.; Guardia-Laguarta, C.; Agrawal, R.R.; Velasco, K.R.; Yun, T.D.; Stavrovskaya, I.G.; Xu, Y.; Koo, S.Y.; et al. The Alzheimer's disease-associated C99 fragment of APP regulates cellular cholesterol trafficking. The EMBO journal 2020, 39, e103791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.Y.; Kwon, O.H.; Chung, S. Preferred Endocytosis of Amyloid Precursor Protein from Cholesterol-Enriched Lipid Raft Microdomains. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetrivel, K.S.; Cheng, H.; Lin, W.; Sakurai, T.; Li, T.; Nukina, N.; Wong, P.C.; Xu, H.; Thinakaran, G. Association of gamma-secretase with lipid rafts in post-Golgi and endosome membranes. The Journal of biological chemistry 2004, 279, 44945–44954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pera, M.; Larrea, D.; Guardia-Laguarta, C.; Montesinos, J.; Velasco, K.R.; Agrawal, R.R.; Xu, Y.; Chan, R.B.; Di Paolo, G.; Mehler, M.F.; et al. Increased localization of APP-C99 in mitochondria-associated ER membranes causes mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer disease. The EMBO journal 2017, 36, 3356–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.G.; Fraser, P.E.; St George-Hyslop, P.; Westaway, D.; Lukiw, W.J. Potential roles for presenilin-1 in oxygen sensing and in glial-specific gene expression. Neuroreport 2004, 15, 2025–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussavi Nik, S.H.; Wilson, L.; Newman, M.; Croft, K.; Mori, T.A.; Musgrave, I.; Lardelli, M. The BACE1-PSEN-AbetaPP regulatory axis has an ancient role in response to low oxygen/oxidative stress. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD 2012, 28, 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussavi Nik, S.H.; Newman, M.; Wilson, L.; Ebrahimie, E.; Wells, S.; Musgrave, I.; Verdile, G.; Martins, R.N.; Lardelli, M. Alzheimer's disease-related peptide PS2V plays ancient, conserved roles in suppression of the unfolded protein response under hypoxia and stimulation of gamma-secretase activity. Human molecular genetics 2015, 24, 3662–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. Oxidative stress in cell culture: an under-appreciated problem? FEBS Lett 2003, 540, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggert, S.; Gonzalez, A.C.; Thomas, C.; Schilling, S.; Schwarz, S.M.; Tischer, C.; Adam, V.; Strecker, P.; Schmidt, V.; Willnow, T.E.; et al. Dimerization leads to changes in APP (amyloid precursor protein) trafficking mediated by LRP1 and SorLA. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS 2018, 75, 301–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.I.; Premraj, S.; Cruz, P.E.; Ladd, T.B.; Kwak, Y.; Koo, E.H.; Felsenstein, K.M.; Golde, T.E.; Ran, Y. Independent Relationship between Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP) Dimerization and γ-Secretase Processivity. PloS one 2014, 9, e111553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuermann, S.; Hambsch, B.; Hesse, L.; Stumm, J.; Schmidt, C.; Beher, D.; Bayer, T.A.; Beyreuther, K.; Multhaup, G. Homodimerization of amyloid precursor protein and its implication in the amyloidogenic pathway of Alzheimer's disease. The Journal of biological chemistry 2001, 276, 33923–33929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwart, D.; Gregg, A.; Scheckel, C.; Murphy, E.A.; Paquet, D.; Duffield, M.; Fak, J.; Olsen, O.; Darnell, R.B.; Tessier-Lavigne, M. A Large Panel of Isogenic APP and PSEN1 Mutant Human iPSC Neurons Reveals Shared Endosomal Abnormalities Mediated by APP beta-CTFs, Not Abeta. Neuron 2019, 104, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laird, J. The Law of Parsimony. The Monist 1919, 29, 321–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.P.; Clark, I.A.; Vissel, B. Questions concerning the role of amyloid-beta in the definition, aetiology and diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol 2018, 136, 663–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, R.J.; Lee, H.G.; Siedlak, S.L.; Nunomura, A.; Hayashi, T.; Nakamura, M.; Zhu, X.; Perry, G.; Smith, M.A. Reexamining Alzheimer's disease: evidence for a protective role for amyloid-beta protein precursor and amyloid-beta. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD 2009, 18, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, R.J.; Smith, M.A. Compounding artefacts with uncertainty, and an amyloid cascade hypothesis that is 'too big to fail'. The Journal of pathology 2011, 224, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondragon-Rodriguez, S.; Basurto-Islas, G.; Lee, H.G.; Perry, G.; Zhu, X.; Castellani, R.J.; Smith, M.A. Causes versus effects: the increasing complexities of Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. Expert Rev Neurother 2010, 10, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepp, K.P. Alzheimer's disease due to loss of function: A new synthesis of the available data. Progress in neurobiology 2016, 143, 36–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perneczky, R.; Jessen, F.; Grimmer, T.; Levin, J.; Floel, A.; Peters, O.; Froelich, L. Anti-amyloid antibody therapies in Alzheimer's disease. Brain : a journal of neurology, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, R.I.; Robertson, S.A.; O'Keefe, L.V.; Fornarino, D.; Scott, A.; Lardelli, M.; Baune, B.T. The Enemy within: Innate Surveillance-Mediated Cell Death, the Common Mechanism of Neurodegenerative Disease. Frontiers in neuroscience 2016, 10, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ihnatovych, I.; Birkaya, B.; Notari, E.; Szigeti, K. iPSC-Derived Microglia for Modeling Human-Specific DAMP and PAMP Responses in the Context of Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolata, G. An Alzheimer’s Treatment Fails: ‘We Don’t Have Anything Now’. The New York Times 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama, M.; Kobayashi, H.; Tatsumi, L.; Tomita, T. Mouse Models of Alzheimer's Disease. Front Mol Neurosci 2022, 15, 912995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulina, M.V.; Hopkins, M.; Haroutunian, V.; Greengard, P.; Bustos, V. C99 selectively accumulates in vulnerable neurons in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association 2020, 16, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaillant-Beuchot, L.; Mary, A.; Pardossi-Piquard, R.; Bourgeois, A.; Lauritzen, I.; Eysert, F.; Kinoshita, P.F.; Cazareth, J.; Badot, C.; Fragaki, K.; et al. Accumulation of amyloid precursor protein C-terminal fragments triggers mitochondrial structure, function, and mitophagy defects in Alzheimer's disease models and human brains. Acta Neuropathol 2021, 141, 39–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, S.S.; Horre, K.; Nicolai, L.; Papadopoulou, A.S.; Mandemakers, W.; Silahtaroglu, A.N.; Kauppinen, S.; Delacourte, A.; De Strooper, B. Loss of microRNA cluster miR-29a/b-1 in sporadic Alzheimer's disease correlates with increased BACE1/beta-secretase expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2008, 105, 6415–6420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checler, F.; Afram, E.; Pardossi-Piquard, R.; Lauritzen, I. Is gamma-secretase a beneficial inactivating enzyme of the toxic APP C-terminal fragment C99? The Journal of biological chemistry 2021, 296, 100489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Casey, A.E.; Sargeant, T.J.; Mäkinen, V.P. Genetic variation within endolysosomal system is associated with late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Brain : a journal of neurology 2018, 141, 2711–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, M.P.; Mishra, S.; Knupp, A.; Young, J.E. The role of Alzheimer's disease risk genes in endolysosomal pathways. Neurobiology of disease 2022, 162, 105576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, H.; Rao, R. Amyloid clearance defect in ApoE4 astrocytes is reversed by epigenetic correction of endosomal pH. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2018, 115, E6640–E6649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Yu, W.H.; Kumar, A.; Lee, S.; Mohan, P.S.; Peterhoff, C.M.; Wolfe, D.M.; Martinez-Vicente, M.; Massey, A.C.; Sovak, G.; et al. Lysosomal proteolysis and autophagy require presenilin 1 and are disrupted by Alzheimer-related PS1 mutations. Cell 2010, 141, 1146–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csordas, G.; Hajnoczky, G. SR/ER-mitochondrial local communication: calcium and ROS. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2009, 1787, 1352–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Area-Gomez, E.; Del Carmen Lara Castillo, M.; Tambini, M.D.; Guardia-Laguarta, C.; de Groof, A.J.; Madra, M.; Ikenouchi, J.; Umeda, M.; Bird, T.D.; Sturley, S.L.; et al. Upregulated function of mitochondria-associated ER membranes in Alzheimer disease. The EMBO journal 2012, 31, 4106–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Area-Gomez, E.; de Groof, A.J.C.; Boldogh, I.; Bird, T.D.; Gibson, G.E.; Koehler, C.M.; Yu, W.H.; Duff, K.E.; Yaffe, M.P.; Pon, L.A.; et al. Presenilins Are Enriched in Endoplasmic Reticulum Membranes Associated with Mitochondria. The American journal of pathology 2009, 175, 1810–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanoiselee, H.M.; Nicolas, G.; Wallon, D.; Rovelet-Lecrux, A.; Lacour, M.; Rousseau, S.; Richard, A.C.; Pasquier, F.; Rollin-Sillaire, A.; Martinaud, O.; et al. APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 mutations in early-onset Alzheimer disease: A genetic screening study of familial and sporadic cases. PLoS Med 2017, 14, e1002270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryman, D.C.; Acosta-Baena, N.; Aisen, P.S.; Bird, T.; Danek, A.; Fox, N.C.; Goate, A.; Frommelt, P.; Ghetti, B.; Langbaum, J.B.; et al. Symptom onset in autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology 2014, 83, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonghe, C.; Cruts, M.; Rogaeva, E.A.; Tysoe, C.; Singleton, A.; Vanderstichele, H.; Meschino, W.; Dermaut, B.; Vanderhoeven, I.; Backhovens, H.; et al. Aberrant splicing in the presenilin-1 intron 4 mutation causes presenile Alzheimer's disease by increased Abeta42 secretion. Human molecular genetics 1999, 8, 1529–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, Q.; Qin, W.; Li, Y.; Wei, Y.; Jia, L. A Rare Variation in the 3' Untranslated Region of the Presenilin 2 Gene Is Linked to Alzheimer's Disease. Molecular neurobiology 2021, 58, 4337–4347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenowitz, W.D.; Fornage, M.; Launer, L.J.; Habes, M.; Davatzikos, C.; Yaffe, K. Alzheimer's Disease Genetic Risk, Cognition, and Brain Aging in Midlife. Annals of neurology, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yan, Y.; Wang, B. gamma-Secretase Genetics of Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Systematic Literature Review. Dermatology 2021, 237, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duchatelet, S.; Miskinyte, S.; Delage, M.; Ungeheuer, M.N.; Lam, T.; Benhadou, F.; Del Marmol, V.; Vossen, A.; Prens, E.P.; Cogrel, O.; et al. Low Prevalence of GSC Gene Mutations in a Large Cohort of Predominantly Caucasian Patients with Hidradenitis Suppurativa. J Invest Dermatol 2020, 140, 2085–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Yang, W.; Wen, W.; Sun, J.; Su, B.; Liu, B.; Ma, D.; Lv, D.; Wen, Y.; Qu, T.; et al. Gamma-secretase gene mutations in familial acne inversa. Science 2010, 330, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duering, M.; Grimm, M.O.; Grimm, H.S.; Schroder, J.; Hartmann, T. Mean age of onset in familial Alzheimer's disease is determined by amyloid beta 42. Neurobiology of aging 2005, 26, 785–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar-Singh, S.; Theuns, J.; Van Broeck, B.; Pirici, D.; Vennekens, K.; Corsmit, E.; Cruts, M.; Dermaut, B.; Wang, R.; Van Broeckhoven, C. Mean age-of-onset of familial alzheimer disease caused by presenilin mutations correlates with both increased Abeta42 and decreased Abeta40. Hum Mutat 2006, 27, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhou, R.; Yang, G.; Shi, Y. Analysis of 138 pathogenic mutations in presenilin-1 on the in vitro production of Abeta42 and Abeta40 peptides by gamma-secretase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2017, 114, E476–E485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.; Yang, G.; Shi, Y. Dominant negative effect of the loss-of-function gamma-secretase mutants on the wild-type enzyme through heterooligomerization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2017, 114, 12731–12736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szaruga, M.; Munteanu, B.; Lismont, S.; Veugelen, S.; Horre, K.; Mercken, M.; Saido, T.C.; Ryan, N.S.; De Vos, T.; Savvides, S.N.; et al. Alzheimer's-causing mutations shift Abeta length by destabilizing gamma-secretase-Abetan interactions. Cell 2021, 184, 2257–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Lauro, B.M.; He, A.; Lee, H.; Bhattarai, S.; Wolfe, M.S.; Bennett, D.A.; Karch, C.M.; Young-Pearse, T.; Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer, N.; et al. Identification of the Abeta37/42 peptide ratio in CSF as an improved Abeta biomarker for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association 2023, 19, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumori, A.; Fluhrer, R.; Steiner, H.; Haass, C. Three-amino acid spacing of presenilin endoproteolysis suggests a general stepwise cleavage of gamma-secretase-mediated intramembrane proteolysis. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2010, 30, 7853–7862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, H.; Romig, H.; Grim, M.G.; Philipp, U.; Pesold, B.; Citron, M.; Baumeister, R.; Haass, C. The biological and pathological function of the presenilin-1 Deltaexon 9 mutation is independent of its defect to undergo proteolytic processing. The Journal of biological chemistry 1999, 274, 7615–7618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, D.; Watanabe, H.; Wu, B.; Lee, S.H.; Li, Y.; Tsvetkov, E.; Bolshakov, V.Y.; Shen, J.; Kelleher, R.J. , 3rd. Presenilin-1 knockin mice reveal loss-of-function mechanism for familial Alzheimer's disease. Neuron 2015, 85, 967–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heilig, E.A.; Gutti, U.; Tai, T.; Shen, J.; Kelleher, R.J. , 3rd. Trans-dominant negative effects of pathogenic PSEN1 mutations on gamma-secretase activity and Abeta production. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2013, 33, 11606–11617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.; Qin, W.; Wu, L.; Zhou, A.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Jia, L.; Jia, J. Two novel presenilin-1 mutations (I249L and P433S) in early onset Chinese Alzheimer's pedigrees and their functional characterization. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2019, 516, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kretner, B.; Trambauer, J.; Fukumori, A.; Mielke, J.; Kuhn, P.H.; Kremmer, E.; Giese, A.; Lichtenthaler, S.F.; Haass, C.; Arzberger, T.; et al. Generation and deposition of Abeta43 by the virtually inactive presenilin-1 L435F mutant contradicts the presenilin loss-of-function hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease. EMBO Mol Med 2016, 8, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, H.; Capell, A.; Pesold, B.; Citron, M.; Kloetzel, P.M.; Selkoe, D.J.; Romig, H.; Mendla, K.; Haass, C. Expression of Alzheimer's disease-associated presenilin-1 is controlled by proteolytic degradation and complex formation. The Journal of biological chemistry 1998, 273, 32322–32331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewji, N.N.; Do, C.; Singer, S.J. On the spurious endoproteolytic processing of the presenilin proteins in cultured cells and tissues. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1997, 94, 14031–14036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raut, S.; Patel, R.; Al-Ahmad, A.J. Presence of a mutation in PSEN1 or PSEN2 gene is associated with an impaired brain endothelial cell phenotype in vitro. Fluids Barriers CNS 2021, 18, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidoni, C.; Follo, C.; Savino, M.; Melone, M.A.B.; Isidoro, C. The Role of Cathepsin D in the Pathogenesis of Human Neurodegenerative Disorders. Medicinal Research Reviews 2016, 36, 845–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Yang, D.S.; Goulbourne, C.N.; Im, E.; Stavrides, P.; Pensalfini, A.; Chan, H.; Bouchet-Marquis, C.; Bleiwas, C.; Berg, M.J.; et al. Faulty autolysosome acidification in Alzheimer's disease mouse models induces autophagic build-up of Abeta in neurons, yielding senile plaques. Nature neuroscience 2022, 25, 688–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Cho, Y.S.; Kim, Y.; Park, J.; Yoo, S.M.; Gwak, J.; Kim, Y.; Gwon, Y.; Kam, T.I.; Jung, Y.K. Endolysosomal impairment by binding of amyloid beta or MAPT/Tau to V-ATPase and rescue via the HYAL-CD44 axis in Alzheimer disease. Autophagy, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustaly-Kalimi, S.; Gallegos, W.; Marr, R.A.; Gilman-Sachs, A.; Peterson, D.A.; Sekler, I.; Stutzmann, G.E. Protein mishandling and impaired lysosomal proteolysis generated through calcium dysregulation in Alzheimer's disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2022, 119, e2211999119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; McBrayer, M.K.; Wolfe, D.M.; Haslett, L.J.; Kumar, A.; Sato, Y.; Lie, P.P.; Mohan, P.; Coffey, E.E.; Kompella, U.; et al. Presenilin 1 Maintains Lysosomal Ca(2+) Homeostasis via TRPML1 by Regulating vATPase-Mediated Lysosome Acidification. Cell reports 2015, 12, 1430–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeter, E.H.; Ilagan, M.X.; Brunkan, A.L.; Hecimovic, S.; Li, Y.M.; Xu, M.; Lewis, H.D.; Saxena, M.T.; De Strooper, B.; Coonrod, A.; et al. A presenilin dimer at the core of the gamma-secretase enzyme: insights from parallel analysis of Notch 1 and APP proteolysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2003, 100, 13075–13080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brautigam, H.; Moreno, C.L.; Steele, J.W.; Bogush, A.; Dickstein, D.L.; Kwok, J.B.; Schofield, P.R.; Thinakaran, G.; Mathews, P.M.; Hof, P.R.; et al. Physiologically generated presenilin 1 lacking exon 8 fails to rescue brain PS1-/- phenotype and forms complexes with wildtype PS1 and nicastrin. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 17042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla-Ayala, A.A.; Sannerud, R.; Mondin, M.; Poersch, K.; Vermeire, W.; Paparelli, L.; Berlage, C.; Koenig, M.; Chavez-Gutierrez, L.; Ulbrich, M.H.; et al. Super-resolution microscopy reveals majorly mono- and dimeric presenilin1/gamma-secretase at the cell surface. Elife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valapala, M.; Hose, S.; Gongora, C.; Dong, L.; Wawrousek, E.F.; Samuel Zigler, J., Jr.; Sinha, D. Impaired endolysosomal function disrupts Notch signalling in optic nerve astrocytes. Nature communications 2013, 4, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccari, T.; Duchi, S.; Cortese, K.; Tacchetti, C.; Bilder, D. The vacuolar ATPase is required for physiological as well as pathological activation of the Notch receptor. Development 2010, 137, 1825–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Denef, N.; Schupbach, T. The vacuolar proton pump, V-ATPase, is required for notch signaling and endosomal trafficking in Drosophila. Developmental cell 2009, 17, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maesako, M.; Houser, M.C.Q.; Turchyna, Y.; Wolfe, M.S.; Berezovska, O. Presenilin/gamma-Secretase Activity Is Located in Acidic Compartments of Live Neurons. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2022, 42, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Moan, N.; Houslay, D.M.; Christian, F.; Houslay, M.D.; Akassoglou, K. Oxygen-dependent cleavage of the p75 neurotrophin receptor triggers stabilization of HIF-1alpha. Mol Cell 2011, 44, 476–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, J.C.; Chiu, D.; Brandes, A.H.; Escorcia, F.E.; Villa, C.H.; Maguire, W.F.; Hu, C.J.; de Stanchina, E.; Simon, M.C.; Sisodia, S.S.; et al. Nontranscriptional role of Hif-1alpha in activation of gamma-secretase and notch signaling in breast cancer. Cell reports 2014, 8, 1077–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Gasperi, R.; Sosa, M.A.; Dracheva, S.; Elder, G.A. Presenilin-1 regulates induction of hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha: altered activation by a mutation associated with familial Alzheimer's disease. Molecular neurodegeneration 2010, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, M.; Nik, H.M.; Sutherland, G.T.; Hin, N.; Kim, W.S.; Halliday, G.M.; Jayadev, S.; Smith, C.; Laird, A.S.; Lucas, C.W.; et al. Accelerated loss of hypoxia response in zebrafish with familial Alzheimer's disease-like mutation of presenilin 1. Human molecular genetics 2020, 29, 2379–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barthelson, K.; Dong, Y.; Newman, M.; Lardelli, M. PRESENILIN 1 mutations causing early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease or familial acne inversa differ in their effects on genes facilitating energy metabolism and signal transduction. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 2021, 82, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervantes, S.; Gonzalez-Duarte, R.; Marfany, G. Homodimerization of presenilin N-terminal fragments is affected by mutations linked to Alzheimer's disease. FEBS Lett 2001, 505, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebert, S.S.; Godin, C.; Tomiyama, T.; Mori, H.; Levesque, G. Dimerization of presenilin-1 in vivo: suggestion of novel regulatory mechanisms leading to higher order complexes. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2003, 301, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manabe, T.; Katayama, T.; Sato, N.; Gomi, F.; Hitomi, J.; Yanagita, T.; Kudo, T.; Honda, A.; Mori, Y.; Matsuzaki, S.; et al. Induced HMGA1a expression causes aberrant splicing of Presenilin-2 pre-mRNA in sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Cell Death and Differentiation 2003, 10, 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manabe, T.; Ohe, K.; Katayama, T.; Matsuzaki, S.; Yanagita, T.; Okuda, H.; Bando, Y.; Imaizumi, K.; Reeves, R.; Tohyama, M.; et al. HMGA1a: sequence-specific RNA-binding factor causing sporadic Alzheimer's disease-linked exon skipping of presenilin-2 pre-mRNA. Genes to Cells 2007, 12, 1179–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharman, M.J.; Moussavi Nik, S.H.; Chen, M.M.; Ong, D.; Wijaya, L.; Laws, S.M.; Taddei, K.; Newman, M.; Lardelli, M.; Martins, R.N.; et al. The Guinea Pig as a Model for Sporadic Alzheimer's Disease (AD): The Impact of Cholesterol Intake on Expression of AD-Related Genes. PloS one 2013, 8, e66235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, N.; Imaizumi, K.; Manabe, T.; Taniguchi, M.; Hitomi, J.; Katayama, T.; Yoneda, T.; Morihara, T.; Yasuda, Y.; Takagi, T.; et al. Increased production of beta-amyloid and vulnerability to endoplasmic reticulum stress by an aberrant spliced form of presenilin 2. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 2108–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, T.; Imaizumi, K.; Sato, N.; Miyoshi, K.; Kudo, T.; Hitomi, J.; Morihara, T.; Yoneda, T.; Gomi, F.; Mori, Y.; et al. Presenilin-1 mutations downregulate the signalling pathway of the unfolded-protein response. Nature cell biology 1999, 1, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katayama, T.; Imaizumi, K.; Manabe, T.; Hitomi, J.; Kudo, T.; Tohyama, M. Induction of neuronal death by ER stress in Alzheimer's disease. Journal of chemical neuroanatomy 2004, 28, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braggin, J.E.; Bucks, S.A.; Course, M.M.; Smith, C.L.; Sopher, B.; Osnis, L.; Shuey, K.D.; Domoto-Reilly, K.; Caso, C.; Kinoshita, C.; et al. Alternative splicing in a presenilin 2 variant associated with Alzheimer disease. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2019, 6, 762–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastrangelo, P.; Mathews, P.M.; Chishti, M.A.; Schmidt, S.D.; Gu, Y.; Yang, J.; Mazzella, M.J.; Coomaraswamy, J.; Horne, P.; Strome, B.; et al. Dissociated phenotypes in presenilin transgenic mice define functionally distinct gamma-secretases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2005, 102, 8972–8977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sannerud, R.; Esselens, C.; Ejsmont, P.; Mattera, R.; Rochin, L.; Tharkeshwar, A.K.; De Baets, G.; De Wever, V.; Habets, R.; Baert, V.; et al. Restricted Location of PSEN2/gamma-Secretase Determines Substrate Specificity and Generates an Intracellular Abeta Pool. Cell 2016, 166, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filadi, R.; Greotti, E.; Turacchio, G.; Luini, A.; Pozzan, T.; Pizzo, P. Presenilin 2 Modulates Endoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondria Coupling by Tuning the Antagonistic Effect of Mitofusin 2. Cell reports 2016, 15, 2226–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yambire, K.F.; Rostosky, C.; Watanabe, T.; Pacheu-Grau, D.; Torres-Odio, S.; Sanchez-Guerrero, A.; Senderovich, O.; Meyron-Holtz, E.G.; Milosevic, I.; Frahm, J.; et al. Impaired lysosomal acidification triggers iron deficiency and inflammation in vivo. Elife 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.A.; Harris, P.L.; Sayre, L.M.; Perry, G. Iron accumulation in Alzheimer disease is a source of redox-generated free radicals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1997, 94, 9866–9868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Malinovska, L.; Saha, S.; Wang, J.; Alberti, S.; Krishnan, Y.; Hyman, A.A. ATP as a biological hydrotrope. Science 2017, 356, 753–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, D.C.; Ollikainen, N.; Trinidad, J.C.; Cary, M.P.; Burlingame, A.L.; Kenyon, C. Widespread protein aggregation as an inherent part of aging in C. elegans. PLoS Biol 2010, 8, e1000450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.Z.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Z.B. Mitochondrial electron transport chain, ROS generation and uncoupling (Review). Int J Mol Med 2019, 44, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, D.J.; Merlot, A.M.; Huang, M.L.; Bae, D.H.; Jansson, P.J.; Sahni, S.; Kalinowski, D.S.; Richardson, D.R. Cellular iron uptake, trafficking and metabolism: Key molecules and mechanisms and their roles in disease. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2015, 1853, 1130–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, S.C.; Moreira, P.I. Oxygen Sensing and Signaling in Alzheimer's Disease: A Breathtaking Story! Cell Mol Neurobiol 2022, 42, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oresic, M.; Hyotylainen, T.; Herukka, S.K.; Sysi-Aho, M.; Mattila, I.; Seppanan-Laakso, T.; Julkunen, V.; Gopalacharyulu, P.V.; Hallikainen, M.; Koikkalainen, J.; et al. Metabolome in progression to Alzheimer's disease. Translational psychiatry 2011, 1, e57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guglielmotto, M.; Tamagno, E.; Danni, O. Oxidative stress and hypoxia contribute to Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis: two sides of the same coin. ScientificWorldJournal 2009, 9, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guglielmotto, M.; Aragno, M.; Autelli, R.; Giliberto, L.; Novo, E.; Colombatto, S.; Danni, O.; Parola, M.; Smith, M.A.; Perry, G.; et al. The up-regulation of BACE1 mediated by hypoxia and ischemic injury: role of oxidative stress and HIF1alpha. Journal of neurochemistry 2009, 108, 1045–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamagno, E.; Guglielmotto, M.; Aragno, M.; Borghi, R.; Autelli, R.; Giliberto, L.; Muraca, G.; Danni, O.; Zhu, X.; Smith, M.A.; et al. Oxidative stress activates a positive feedback between the gamma- and beta-secretase cleavages of the beta-amyloid precursor protein. Journal of neurochemistry 2008, 104, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontush, A.; Donarski, N.; Beisiegel, U. Resistance of human cerebrospinal fluid to in vitro oxidation is directly related to its amyloid-beta content. Free Radic Res 2001, 35, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontush, A. Amyloid-beta: an antioxidant that becomes a pro-oxidant and critically contributes to Alzheimer's disease. Free Radic Biol Med 2001, 31, 1120–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.A.; Casadesus, G.; Joseph, J.A.; Perry, G. Amyloid-beta and tau serve antioxidant functions in the aging and Alzheimer brain. Free Radic Biol Med 2002, 33, 1194–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadal, R.C.; Rigby, S.E.; Viles, J.H. Amyloid beta-Cu2+ complexes in both monomeric and fibrillar forms do not generate H2O2 catalytically but quench hydroxyl radicals. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 11653–11664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baruch-Suchodolsky, R.; Fischer, B. Abeta40, either soluble or aggregated, is a remarkably potent antioxidant in cell-free oxidative systems. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 4354–4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T.; Pan, Y.; Kao, S.Y.; Li, C.; Kohane, I.; Chan, J.; Yankner, B.A. Gene regulation and DNA damage in the ageing human brain. Nature 2004, 429, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iturria-Medina, Y.; Sotero, R.C.; Toussaint, P.J.; Mateos-Perez, J.M.; Evans, A.C.; Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging, I. Early role of vascular dysregulation on late-onset Alzheimer's disease based on multifactorial data-driven analysis. Nature communications 2016, 7, 11934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leenders, K.L.; Perani, D.; Lammertsma, A.A.; Heather, J.D.; Buckingham, P.; Healy, M.J.; Gibbs, J.M.; Wise, R.J.; Hatazawa, J.; Herold, S.; et al. Cerebral blood flow, blood volume and oxygen utilization. Normal values and effect of age. Brain : a journal of neurology. [CrossRef]

- Braz, I.D.; Fisher, J.P. The impact of age on cerebral perfusion, oxygenation and metabolism during exercise in humans. J Physiol 2016, 594, 4471–4483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solleiro-Villavicencio, H.; Rivas-Arancibia, S. Effect of Chronic Oxidative Stress on Neuroinflammatory Response Mediated by CD4(+)T Cells in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front Cell Neurosci 2018, 12, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guay-Gagnon, M.; Vat, S.; Forget, M.F.; Tremblay-Gravel, M.; Ducharme, S.; Nguyen, Q.D.; Desmarais, P. Sleep apnea and the risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sleep Res 2022, 31, e13589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinford, C.G.; Risacher, S.L.; Wu, Y.C.; Apostolova, L.G.; Gao, S.; Bice, P.J.; Saykin, A.J. Altered cerebral blood flow in older adults with Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review. Brain Imaging Behav, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, F.; Iqbal, K.; Grundke-Iqbal, I.; Gong, C.X. Decreased glucose transporters correlate to abnormal hyperphosphorylation of tau in Alzheimer disease. FEBS Lett 2008, 582, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Rawashdeh, O.; Kasas, L.; Milne, M.R.; Garner, N.; Sankorrakul, K.; Marks, N.; Dean, M.W.; Kim, P.R.; Sharma, A.; et al. Cholinergic basal forebrain degeneration due to sleep-disordered breathing exacerbates pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature communications 2022, 13, 6543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, T.T.; Chua-Couzens, J.; Butcher, L.L.; Bredesen, D.E.; Cooper, J.D.; Valletta, J.S.; Mobley, W.C.; Longo, F.M. Absence of p75NTR causes increased basal forebrain cholinergic neuron size, choline acetyltransferase activity, and target innervation. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 1997, 17, 7594–7605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehouse, P.J.; Price, D.L.; Struble, R.G.; Clark, A.W.; Coyle, J.T.; Delon, M.R. Alzheimer's disease and senile dementia: loss of neurons in the basal forebrain. Science 1982, 215, 1237–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Lee, H.G.; Perry, G.; Smith, M.A. Alzheimer disease, the two-hit hypothesis: an update. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2007, 1772, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, K.A.; Ayoub, A.E.; Breunig, J.J.; Adhami, F.; Weng, W.L.; Colbert, M.C.; Rakic, P.; Kuan, C.Y. Nestin-CreER mice reveal DNA synthesis by nonapoptotic neurons following cerebral ischemia hypoxia. Cerebral cortex 2007, 17, 2585–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goda, N.; Ryan, H.E.; Khadivi, B.; McNulty, W.; Rickert, R.C.; Johnson, R.S. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha is essential for cell cycle arrest during hypoxia. Molecular and cellular biology 2003, 23, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.D.; Tan, E.K. Iron regulatory protein (IRP)-iron responsive element (IRE) signaling pathway in human neurodegenerative diseases. Molecular neurodegeneration 2017, 12, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hin, N.; Newman, M.; Pederson, S.; Lardelli, M. Iron Responsive Element-Mediated Responses to Iron Dyshomeostasis in Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 2021, 84, 1597–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsatsanis, A.; Wong, B.X.; Gunn, A.P.; Ayton, S.; Bush, A.I.; Devos, D.; Duce, J.A. Amyloidogenic processing of Alzheimer's disease beta-amyloid precursor protein induces cellular iron retention. Molecular psychiatry 2020, 25, 1958–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigoni, M.; Wanngren, J.; Kuhn, P.H.; Munro, K.M.; Gunnersen, J.M.; Takeshima, H.; Feederle, R.; Voytyuk, I.; De Strooper, B.; Levasseur, M.D.; et al. Seizure protein 6 and its homolog seizure 6-like protein are physiological substrates of BACE1 in neurons. Molecular neurodegeneration 2016, 11, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.A.; Perry, G. Free radical damage, iron, and Alzheimer's disease. Journal of the neurological sciences 1995, 134 Suppl, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, D.; Chevion, M. The role of iron in beta amyloid toxicity. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 1995, 216, 702–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullner, E.W.; Kuhn, L.C. A stem-loop in the 3' untranslated region mediates iron-dependent regulation of transferrin receptor mRNA stability in the cytoplasm. Cell 1988, 53, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, J.L.; Hentze, M.W.; Koeller, D.M.; Caughman, S.W.; Rouault, T.A.; Klausner, R.D.; Harford, J.B. Iron-responsive elements: regulatory RNA sequences that control mRNA levels and translation. Science 1988, 240, 924–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).