1. Introduction

At 662 billion tonnes of carbon, marine dissolved

organic matter (DOM) holds > 200 times as much organic matter (OM) as the

living marine biomass and around 100 times more than the dead particulate

organic carbon (1) (Hansell et al., 2009). Marine (DOM) contains as much carbon

as the Earth’s atmosphere, and represents a critical component of the global

carbon cycle (2) (McCarren et al. 2010). In the ocean, this DOM is primarily

produced by eukaryotic and prokaryotic phytoplankton, with some macroalgae,

that reduce CO2 to OM, using sunlight as energy source. The molecular

characteristics of the proteins produced are controlled by the organisms'

genes. Further proteins, and other OM, are then manufactured using enzymes,

which also are proteins. This OM consists of particulate matter (POM), mainly

the solid parts plankton organisms, and DOM that is secreted by phytoplankton

and lost from cells during lysis. This paper is not concerned with the POM,

treating only the DOM as well as mucus consisting of exopolymeric substances

(EPS). Ocean DOM can be usefully characterized in two ways.

The first way to categorize DOM is by chemical

composition. The most abundant primary component of DOM is sugars, followed in

decreasing order by amino acids, fatty acids and nucleic acid bases, which

correspond for EPS to polysaccharides, proteins, lipids and nucleic acids (DNA

and RNA). Much of the EPS consists of polymer molecules bearing a variety of

functional groups, which determine their physicochemical properties and roles

in the ecosystem.

The first way to categorize DOM is by age. The

largest fraction of DOM is weeks to hundreds or thousands of years old and has

the highest proportion of DOM recalcitrant to biological breakdown (1) (3)

(Hansell et al., 2009; Jiao et al., 2010), as well as showing little surfactant

or rheological activity (4) (Jenkinson et al., 2015, JPR). The second, smaller,

fraction of DOM is seconds to days or weeks old. It is thus biologically and

chemically labile. Some of it is highly surface-active (hydrophilic,

amphiphilic or hydrophobic) and some of it adds viscoelastic properties to the

water, thus thickening it (4) (Jenkinson et al., 2015 JPR). This category of

DOM is relatively the most abundant in the photic zone, particularly in certain

harmful algae blooms and mucus events (4) (Jenkinson, 2015 JPR). It also

includes most of the signalling, pheromone and toxin molecules (5) (Brown et

al., 2019), that may modulate ecosystem structure (6) (Yamasaki et al., 2009)

and bidirectional vertical fluxes, of OM within the water column (7) (Mari et

al., 2017) and of matter and energy across the ocean-atmosphere interface (8)

(9) (Wurl et al., 2017; Jenkinson et al., 2021).

Given that the allochthonous ocean OM is produced

by marine organisms' genes, and that some of this OM changes the physical

properties of bulk ocean water, as well as its interfaces and fluxes across

them, it follows that these properties and fluxes are partly under genetic

control, and thus subject to natural selection and evolution (10) (11) (Darwin,

2003; Dawkins, 2016).

Rapid progress is being made cataloguing the genes

of the pelagic ecosystem, as well as discovering both their roles in producing

proteins, and ultimately, via enzymes, of polysaccharides and lipids. Progress

is also being made in categorizing the rheological properties of ocean waters

and soft polymeric structures, as well as how these properties and structures

modulate processes and fluxes. The terrestrial/atmospheric and submarine

climates are currently changing (12) (IPCC, 2021), which is stressing and

altering the biota, including humans. The first aim of this paper, therefore,

is to suggest some of the possible roles of genomes in promoting biorheological

changes that influence biogeochemical processes. The second aim is to promote

bridging of the gap between ocean science and rheology, and to suggest how

collaborative research programmes including genomics, ocean rheology, ocean

ecology and flux studies can be set up to understand how genes control internal

ocean processes, and their interaction with the atmosphere. As an added bonus

such studies are likely to throw up commercially exploitable new natural

bioactive products.

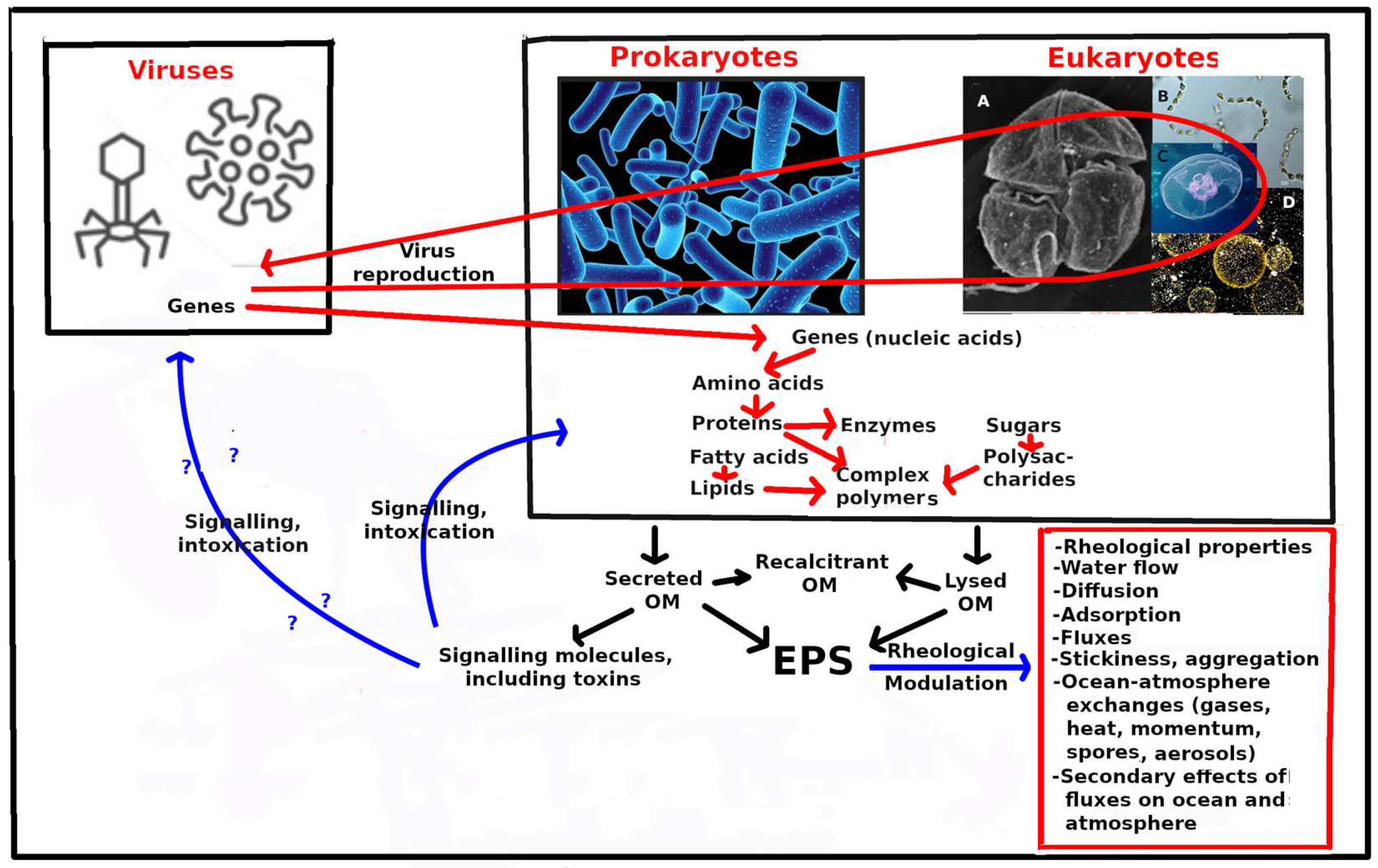

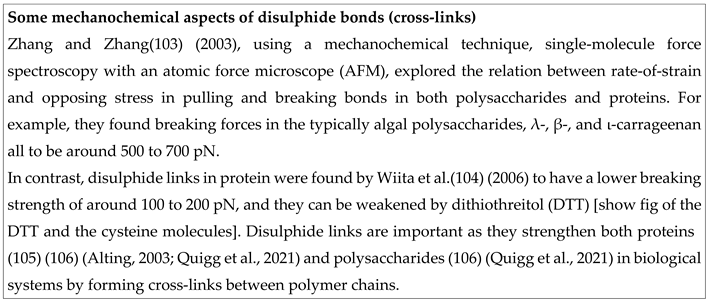

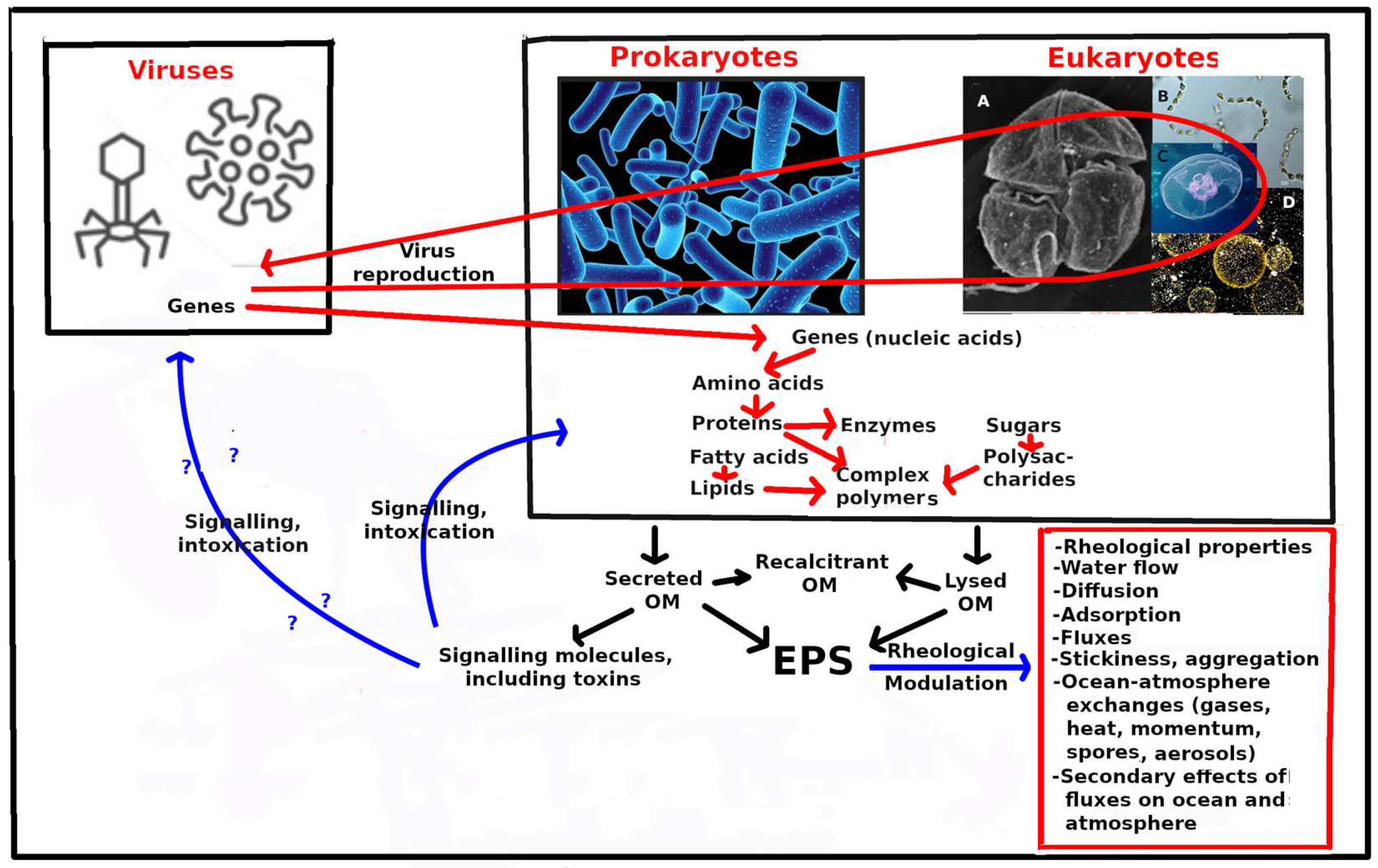

A sketch of these ideas is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Three categories of gene-bearing ("living") organisms are presented, viruses, prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Prokaryotes and eukaryotes are shown in the same compartment, as generally they both have an independent machinery to form amino acids and proteins (including enzymes) from "instructions" in their genes. Enzymes modulate (catalyse) intracellular molecular transformations (modulation pathways not shown). Viruses are placed in a separate box as they need to introduce their genes into prokaryotic or eukaryotic cells, taking some control of these cells in order to reproduce their genes and outer casing. Red arrows represent the pathways of viral reproduction, and transfer of viral genes to replace or modulate prokaryotic or eukaryotic genes (13) (Rosenwasser et al., 2016). Red arrows are used also to represent transfers between the major types of organic molecules inside cells. Black arrows represent transformations between the major suggested extracellular pools of organic matter (OM). Blue arrows represent modulation by extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) on physical and physicochemical processes in the ocean and at the ocean-atmosphere interface, as well as secondary effects in the ocean and the atmosphere (inside red box). Blue arrows also represent signalling and intoxication pathways by signalling molecules and toxins, respectively. Eukaryotic plankton is represented by: A - a dinoflagellate; B - a diatom; C - a jellyfish medusa; D - a raphidophyte. This is not a sketch of trophic or energy pathways.

Figure 1.

Three categories of gene-bearing ("living") organisms are presented, viruses, prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Prokaryotes and eukaryotes are shown in the same compartment, as generally they both have an independent machinery to form amino acids and proteins (including enzymes) from "instructions" in their genes. Enzymes modulate (catalyse) intracellular molecular transformations (modulation pathways not shown). Viruses are placed in a separate box as they need to introduce their genes into prokaryotic or eukaryotic cells, taking some control of these cells in order to reproduce their genes and outer casing. Red arrows represent the pathways of viral reproduction, and transfer of viral genes to replace or modulate prokaryotic or eukaryotic genes (13) (Rosenwasser et al., 2016). Red arrows are used also to represent transfers between the major types of organic molecules inside cells. Black arrows represent transformations between the major suggested extracellular pools of organic matter (OM). Blue arrows represent modulation by extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) on physical and physicochemical processes in the ocean and at the ocean-atmosphere interface, as well as secondary effects in the ocean and the atmosphere (inside red box). Blue arrows also represent signalling and intoxication pathways by signalling molecules and toxins, respectively. Eukaryotic plankton is represented by: A - a dinoflagellate; B - a diatom; C - a jellyfish medusa; D - a raphidophyte. This is not a sketch of trophic or energy pathways.

2. Inorganic matter (IM) and organic matter (OM) in the oceans

2.1. Sources of available N and Fe

Estimated annual sources and sinks of organic

nitrogen (ON), fixed inorganic nitrogen (IN) and Fe for the global coastal

ocean (depth ≤200 m) the offshore ocean (>200 m) and the whole ocean (14)

(Liu et al., 2021) are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Global coastal ocean nitrogen, N, and iron, Fe, budget terms (Tg y-1) (estimated annual means).

Table 1.

Global coastal ocean nitrogen, N, and iron, Fe, budget terms (Tg y-1) (estimated annual means).

| |

Coastal Ocean (1) (14) |

Whole ocean (15) (16) (2,3) |

Open ocean (16) (3) |

| Inorganic N (IN) |

|

|

|

| Atmospheric deposition (DIN) |

+ 4.5 |

|

|

| River input (DIN) |

+20.4 |

+23 (16) (3) |

+17(a)(16) (3) |

| Denitrification (water + sediments) (DIN) |

-51.9 |

|

|

| Coastward net influx from offshore (DIN) |

+47.4 |

|

|

| Total Δ TIN |

+20.4 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Organic N (ON) |

|

|

|

| Sedimentary burial (TON) |

-12.3 |

|

|

| River input (TON) |

+ 27.1 |

|

|

| River input (DON) |

|

+11(a) (16) (3) |

>0 to <11(a) (16) (3) |

| N2 fixation (TON) |

+15.4 |

164 (16) (3) |

0 (16) (3) |

| Oceanward net outflux to offshore (TON)

|

-50.2 |

|

|

| Total Δ TON |

-20.0 |

|

|

| Discrepancy (ΔTIN – ΔTON) |

+0.4 |

|

|

|

Net community production (DIN+TON)

|

35.5 |

|

|

| Atmospheric N deposition |

|

39(b) (16) (3) |

>30(b) (16) (3) |

| Atmosphere-ocean Fe budget |

|

|

|

| Fe emissions from fires (<20 µm) |

|

1.1 (15) (2) |

|

| Soluble Fe flux to the ocean (from dust) |

|

0.19 to 0.28 (15) (2) |

|

| Soluble Fe flux to the ocean (from fires) |

|

0.035 to 0.063 (15) (2) |

|

| Soluble Fe flux to the ocean (anthropogenic) |

|

0.016 to 0.034 (15) (2) |

|

| Soluble Fe flux to the ocean (Total) |

|

0.24 to 0.38 (15) (2) |

|

| Soluble P flux to the ocean (from dust) |

|

0.031 to 0.094 (15) (2) |

|

| Soluble P flux to the ocean (from fires) |

|

0.005 (15) (2) |

|

| Soluble P flux to the ocean (anthropogenic) |

|

0.0094 to 0.11(15) (2) |

|

| Soluble P flux to the ocean (Total) |

|

0.045 to 0.21 (15) (2) |

|

1 – Ref. (14) Liu et al. (2021); 2 – Ref. (15) Hamilton et al. (2022); 3 - Ref. (16) Jickells et al. (2017).

a – 75% of riverine input escapes beyond the shelf break; b – 75% of atmospheric input deposited outside the shelf break. |

2.2. Origins and classes of allochthonous IM and OM

The main origins of dissolved IM (DIM) are soluble

salts associated with: riverine and terrestrial diffuse sources. They include

nutrient salts, notably nitrate, nitrite, ammonia and urea, dissolved inorganic

phosphate and dissolved silicate. Anthropogenic sources have increased, not

only of nitrogenous nutrients and phosphate, but also of silicate due to

disruption of soils and coastal development. The current estimated annual

global budget in for coastal waters (depth ≤200 m) (14) (Liu et al., 2021) is shown

in Table 1 for marine reactive N.

Important sources and sinks of OC and reactive N in

the ocean are atmospheric deposition, sedimentary burial (15) (Hamilton et al.,

2022).

2.3. Origins and classes of autochthonous OM

Most OM in the ocean is produced autochthonously.

Ocean Phytoplankton and bacteria sensu lato produce a wide variety of

organic molecules. They result from direct extracellular secretion by living

cells, as well as leakage from lysed and predated cells as dissolved OM (DOM),

normally defined as that passing through a 0.2-µm filter, as well as

particulate OM (POM), which is retained by a 0.5µm filter (17) (Shen and

Benner, 2019). Between these extremes lies colloidal OM (COM). In order of

abundance the DOM and COM comprise sugars, amino-acids, fatty acids and nucleic

acid bases, polymerized to varying degrees into carbohydrates, proteins, lipids

and nucleic acids, respectively, along with complex molecules bearing different

radical groups.

2.4. Autochthonous particulate organic matter (POM)

POM produced within the pelagic ocean ecosystem

consists principally of living cells and dead remains of cells. These particles

act as mechanically solid surfaces allowing colonization by bacteria and

protists such as ciliates. These particles also become included in marine

aggregates, together with living bacteria and protists, within the more-or-less

gluey polymeric matrix of COM. POM is believed to be negatively buoyant in

general, and to act, together with autochthonous and allochthonous PIM to

ballast marine organic aggregates, thus increasing downward organic flux (7)

(Mari et al., 2017). More work is required on the functional density and

sinking behaviour of marine POM.

The relationships between composition, measured

density and sinking/rising rates of both non-living and living POM has subject

to much research (18) (19) (20) (7) (Bienfang et al., 1977; Bienfang, 1980;

Wakeham et al., 1984; Mari et al., 2017), this has given rise to varied and

confusing results. Largely this may arise from the Derjaguin-Landau-Verwey-Overbeek

assumption (DLVO), taught almost universally in engineering textbooks during

the 20th century, of the quasi-universal non-stick non-slip interface between

water and solid surfaces. Recent research on fluid dynamics at sub-mm and particularly

sub-µm length scales, has shown very considerable departure from DLVO between

even Newtonian liquids, such as water, and solid surfaces of different

qualities, such as rough, smooth, hydrophobic or hydrophilic (21) (22) (23)

(Rothstein, 2010; Conlisk, 2013; Jenkinson, 2014). Moreover, the surfaces of

POM and even PIM adsorb a covering of OM, which may show varied and complex

surface properties. Furthermore, living cells, including those in aggregates

and biofilms, manage their surface properties through electric fields, partly

by means of glycocalyxes.

2.5. Autochthonous dissolved organic matter (DOM)

Old DOM is mostly refractory (rDOM), while DOM

newly produced by phytoplankton (pDOM) tends to be highly reactive and labile

Most DOM in surface, mesopelagic and deep waters is

old rDOM. In laboratory studies, Shen and Benner(17) (2019) found that, over a

time scale of 180 days, about 6-7% of DOM in surface water (50 and 100 m), 1-3%

in mesopelagic water (300 m and 750 m) and 0% in deep pelagic water (1500 m)

was removed by microbial degradation. The authors found that the amount of

degradation depended on the depth origin of the OM, not on that of the

microbial community.

pDOM was sampled by filtering (0.7 µm) an in-situ

bloom was found to be utilized 50-75% within 7 d, and 76-94% within 180 d. By

contrast, microbial utilization of DOM from 1500 m was not measurable even

after 180 d: it consisted all of rDOM. Spectrophotometry at wavelengths from

250 to 750 nm of both pDOM and rDOM revealed that pDOM showed two absorbance

shoulders, at 250-265 nm and at 300-350 nm due to chromophore molecules or

groups, but rDOM did not. These two wavelength ranges correspond to labile

compounds, including amino-acids and mycosporine-like amino-acids, respectively.

Furthermore, elemental analysis revealed that while pDOM had a C/N value, 6.2,

similar to the Redfield ration, the corresponding value for rDOM was 36.2,

confirming that microbes utilized N-rich DOM referentially, and thus caused the

remaining DOM to become depleted in N (17) (Shen and Benner, 2019), and thus

probably in protein.

3. DOM with signalling and allelopathic functions

Many algal and protist species produce allelopathic

compounds. The raphidophyte, Heterosigma akashiwo, produces high-molecular mass

(>1 MDa) allelopathic polysaccharide-protein complexes that inhibit its

competitor, the diatom Skeletonema costatum (now S. marinoi), by binding to the

latter's cell surface. The authors suggested that viscoelastic, colloidal

and/or selectively adhesive of these and other allelopathic

polysaccharide-protein complexes (APPCs). The Skeletonema in turn were found to

produce several fractions (separated by solid phase extraction) that

allelopathically inhibited the Heterosigma in a dose-related manner (6)

(Yamasaki et al., 2009).

At bloom concentrations the diatoms, Skeletonema

costatum, Chaetoceros danicus and Thalassiosira decipiens, all slowed the

swimming of the dinoflagellate, Cochlodinium (now Margalefidinium) polykrikoides(24)

(Lim, A.S. et al., 2014), and the authors suggested that this might have

impaired vertical migration of the latter and hence its ability to form blooms.

The nature of the allelopathic agent(s), however, was not determined.

Axenically cultured Margalefidinium polykrikoides

was found to produce copious mucus, giving average yields of crude

polysaccharide of 26 mg/L of culture medium., which on hydrolysis yielded

mannose, galactose, glucose and uronic acid together with sulphate groups (7-8%

w/w S). The purified polysaccharide inhibited 11 virus strains out of 15 tested

at concentrations of 0.8 to 25 mg/L. This abundant occurrence of sulphur-rich

molecules is compatible with mucous gel formation by inter-group disulphide

links (25) (Hasui et al., 1995).

The first diatom pheromone was identified by

Gillard et al. (26) (2012), Pheromones are defined as molecules involved in

intraspecific signalling, notably facilitating sexual encounter, while those

used for interspecific communication are allelochemicals(27) (Frenket al.2014).

Many algal pheromones are organic acids or

alcohols, while some are also proteins or glycoproteins (27) (Frenket al.,

2014). For example, in the freshwater colonial heterothallic alga, Volvox

carteri f. nagariensis, that survives drying out as dormant zygotes, the end of

drought induces male colonies to secrete a pheromone inducer that is a

large-molecular-mass glycoprotein, and that affects both male and female

colonies. This pheromone inducer acts at a concentration of only10-16

M. It is produced by somatic cells, but initiates gametogenesis by male and

female cells. The gene that encodes the pheromone has been discovered (28)

(Tschochner et al., 1987) and the corresponding protein contains 208 amino

acids with a molecular mass of 22 kDa (29) (27) (Mages et al., 1988; Frenkel et

al., 2014).

Much laboratory work has been carried out on the

influence of bacteria on phytoplankton biosynthesis of natural products (5)

(Brown et al., 2019). The results obtained may give general clues to the

production and effects of signalling compounds in the ocean, as well as the

roles of these compounds in structuring ecosystems.

Particularly since the 2010s, the emphasis of work

has evolved from allelopathic interactions to intraspecific signalling (30)

(Schwartz et al., 2016). Recent work has also targeted phytoplankton chemical

defences, particularly where the molecules involved, e.g. paralytic shellfish

toxins (PSTs) or amnesiac shellfish toxins (ASTs), can impact human health (17)

(Shen and Benner , 2019). The use of –omics (metabolomics, proteomics and transcriptomics)

are revealing mechanisms of biological response to many chemical signals and

cues. Outside the area of compounds showing potential for medical or commercial

innovation, characterization of the multitude of often unstable and very dilute

compounds responsible for chemical mediation of pelagic interactions may remain

impracticable (5) (Brown et al., 2019). Studies of molecules that modify

turbulence, diffusion and binding processes, notably those produced in harmful

algal blooms (31) (32) (Jenkinson and Sun, 2010; Gobler et al, 2017), in

organic aggregates (33) (Karlusich et al., 2022), in biofilms and interaction

of such molecules with pollutants (34) (Santschi et al., 2021) may also benefit

from investigation using–omics. (See section 17.)

A study by Poulson-Ellestad et al. (35) (2014a-JPR)

of the allelopathic effects of the toxic dinoflagellate, Karenia breve, on 9

species of planktonic diatoms typically present in the areas where K. breve

blooms in the Gulf of Mexico, showed only weak stimulatory or inhibitory

effects on the diatoms, leading the authors to suggest that allelopathic

effects could not have been useful to K. breve at the start of the bloom, but

could be useful in maintaining blooms once they were established. A second

study by Poulson-Ellestad et al. (36) (2014b-PNAS) on the allelopathic effects

of K. breve on two different diatoms, one of the species, Thalassiosira

pseudonana, turned out to be the more susceptible. That K. breve affected

nutrient limitation of T. pseudonana was considered unlikely as concentrations

were non-limiting. Metabolomic and proteomic investigation using gene ontology

categories for a long suite of proteins associated with metabolic pathways and

functions in T. pseudonana revealed that many processes, including those

involved in cellular carbohydrate metabolism, were strongly stimulated when

exposed to K. breve, while others, including photosynthesis and chromatin

assembly, were strongly inhibited. That T. pseudonana was susceptible to K.

breve may be associated with the finding that the two species do not co-occur

in nature. Although K. breve produces the toxin, brevetoxin, it is not known if

this was an allelopathic agent acting against T. pseudonana.

In a study from the Baltic, Hakenen et al. (37)

(2014) tested 10-µm filtrate of cultures of 10 local strains of a recurring

dinoflagellate, Alexandrium ostenfeldii on different flagellates. At

characteristic bloom concentrations, all the strains caused allelopathic

effects on the cryptophyte, Rhodomonas salina and the dinoflagellates,

Kryptoperidinium foliaceum, Levanderina fissa and Heterocapsa triquetra. All

the strains of A. ostenfeldii showed allelopathic effects on all the target

species. K. foliaceum reacted by encysting, but excysted again within 24 h, a proportion

of the L. fissa cells lysed, and H. triquetra shed their thecae and became

immotile, but within 24 hours they had mostly recovered. The chemical nature of

the allelopathic agent was not investigated.

4. Molecules in intraspecific and interspecific signalling

Pheromones, secreted by copepods such as Temora

longicornis and Eurytemora affinis, change the swimming behaviour of

conspecifics of the opposite sex (both males and females). This is consistent

with evolved use of pheromones to optimize encounters which may lead to mating

(38) (Seuront and Stanley, 2014).

Another use of intraspecific signalling is for

communication in biofilms. Bacteria, Vibrio cholerae, cooperate to protect

themselves and each other against predatory amoebae, Acanthamoeba casalanii,

using vibriopolysaccharide, an extracellular matrix of proteins, nucleic acids,

and sugars (39) (Yildiz et al., 2014), which are in part controlled by the

quorum sensing (QS) regulator, HapR (40) (Sun et al., 2013). The genes, vpsR

and vpsT, were shown to confer enhanced resistance to amoeboid grazing, since

grazing was enhanced in knockdown mutants. Further reduction in grazing

resistance occurred when QS was interrupted by knocking out the hapR

regulator(40) (Sun et al., 2013).

As well as signalling by DMS (See section 5),

selection of bacterial prey by the ascidian tunicate, Microcosmus exasperatus,

may depend on surface molecules of the bacteria more than on their shape or

size. Marine picocyanobacteria, notably Synecococcus and Prochorococcus, have

sticky, hydrophobic coatings, and are retained with relatively high efficiency

by the feeding nets of the ascidian. In contrast, Pelagibacter ubique, and

other species of the SAR11 guild have a non-sticky, non-hydrophobic coatings,

which allows them to slip through the mucous feeding nets and thus show low

retention by this tunicate. While such a coating may reduce adhesion to

nutrient-rich organic particles, it may confer resistance to grazing by

mucous-net suspension feeders(41) (Dadon-Pilosof et al., 2017).

Rosa et al.(42) (2017) carried out a study on

feeding selection by two lamellibranch molluscs, Mytilus edulis and Crassostrea

virginica, of 10 species of nanoflagellates. The selection and sorting

structures in these molluscs are complex and dynamic, but like in ascidians,

mucus is heavily involved. Amongst the nanoflagellates studied, only Pavlova

lutheri had a wettable, hydrophilic surface, and its retention by the molluscs

was also the least. The wettability (hydrophilicity) and surface charge of

surface of many cells is largely modulated by lectins in the glycolcalyx.

Lectins are widely distributed glycoproteins, with important functions in

molecular recognition.

5. Dimethylsulphide (DMS) in signalling and structuring consortia

DMS is responsible for the characteristic smell of

algae culture rooms. It is secreted by most dinoflagellates, including the

hosts of the parasitic dinoflagellate, Parvilucifera sinerae. Garcés et al.

(43) (2013) found that concentrations of 270-300 nM DMS end dormancy in P.

sinerae. Correspondingly, all dinoflagellate species that produce DMS in

sufficient concentration cause P. sinerae to wake up, but only some of these

species get parasitized. Garcés et al. (43) (2013) suggested that this was a

rare demonstrated example of the now classical idea of “watery arms race[s]” in

the ocean(44) (Smetacek, 2001). Are watery arms races so rare, however?

Schwartz et al. (30) (2016) review many examples of models as well as

laboratory and field studies supporting complex dynamics between competing

species, where one or more species deploys allelopathic compounds to inhibit or

even lethally poison competitors. (See Sections

3, 4 and 7.) Outcomes can be the elimination of one competitor or else

co-existence, depending on environmental conditions such as nutrient

concentrations or even allelopathically influenced nutrient uptake dynamics.

Signalling molecules are not all aggressive, but

may be mutually helpful. Studies of mutualism in the sea have long been

concentrated on bitrophic interactions and it was widely assumed that more

complex mutualistic systems in the ocean were rare (30) (Schwartz et al.,

2016). Recently, however, Savoca and Nevitt (45) (2014) produced evidence for

tritrophic mutualism in the Southern Ocean, where phytoplankton are grazed by

crustaceans. This phytoplankton releases copious DMS, which in turn attracts

procelliiform seabirds that feed on these primary consumers, thereby reducing

grazing pressure on the phytoplankton. In a similar vein, Amo et al. (46) (2013)

found experimentally that the nestlings of the krill-eating chinstrap penguin,

Pygoscelis antarctica, are attracted to the scent of DMS. Thus it is likely

that DMS released by zooplankton grazing acts as a signalling molecule via the

penguins within a consortium at length scales at least up to 100s of m. In this

consortium cohesion was achieved by the penguins’ behavioural attraction to

DMS.

6. Consortia structured by rheological properties, including stickiness, of polymers

In many other consortia, such as biofilms (47) (48)

(49) (Kerfahi et al., 2022; Imai et al., 2021; Karn et al., 2020), lake and

marine organic aggregates(50) (51) (Qin et al., 2021; McManus et al., 2021),

however, cohesion is achieved by physical processes such as stickiness (52) (Santschi

et al., 2020), gelling (53) (Duan et al., 2022) or increased viscosity (54)

(Guadayol et al., 2020) mediated by exopolymeric substances (EPS). Schwartz et

al. (30) (2016) suggested that consortia with more elements than 3 are likely

to exist, but that the number of degrees of freedom would make their existence

difficult to prove.

Aron et al. (55) (2020) have introduced Global

Natural Product Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) as a tool for analysing the

infrastructure of molecular datasets. and curating the data in a public

database in the style of GenBase. GNPS may have the potential for

investigating diverse marine consortia and other biotopes, and ultimately the

whole ocean. It may desirable to accompany such a molecular database with

another on associated measured rheological properties in the ocean environment

at different scales.

7. Prey-capture and predator-avoidance

Chemical cues exuded by prey or occurring on their

surface can be used by predators to locate and choose their prey. The copepod, Temora

longicornis, feeds on sinking marine snow (MDS) particles, which leave a

chemical trail behind them (56) (Lombard et al., 2012). The detection of

tunicate exoskeletons (as an experimental proxy for MS) produced doubling of

swimming velocity towards the falling particle; the authors suggested that

detection must have been chemical, as distances were too great for

hydromechanical methods. They also drew parallels with how pheromones secreted

by the copepods, T. longicornis and Eurytemora affinis, change the swimming

behaviour of the opposite sex (38) (Seuront & Stanley, 2014). (See Section 4.)

8. Predator-prey interactions

Schwartz et al. (30) (2016) reviewed the effects of

chemical signalling in protist-protist and copepod-protist pairs. Many different

reactions have been reported, both on predator-prey reactions and on the

swimming behaviour of both prey and predators. Brown et al. (5) (2019) also

reviewed the effects of signalling molecules on predator-prey pairs,

particularly invoking the effects of phytoplankton toxins, acting either to

harm potential predators or as aids in capturing prey.

Ianora and Miralto(57) (2009) review the

short-chain polyunsaturated aldehydes (PUAs), secreted when copepods such as

Calanus finmarchicus, or Temora longicornis graze on diatoms such as

Thalassiosira rotula, T. pseudonana, Phaeodactylum tricornutum, Skeletonema

marinoi, Chaetoceros affinis, C. decipiens or C. socialis, and as a result

produce deformed and thus unviable larvae. Some species of the planktonic diatom

genus, Pseudo-nitzschia, such as P. seriata, internally produce and partially

release a nerve toxin that produce Amnesic Shellfish Poisoning (ASP) in humans,

as well as behavioural changes in marine vertebrates and some invertebrates.

Tammilehto et al. (58) (2015) found that P. seriata releases the secondary

metabolite, domoic acid (DA), when damaged through grazing by copepods, such as

C. hyperboreus and C. finmarchicus. The same copepods, however, were highly

resistant to the DA (59) (Harðardóttir et al., 2015), which suggested to Brown

et al. (5) (2019) that some populations of copepods may have evolved resistance

to DA.

Prince et al. (60) (2013) showed that, as well as

acting as a neurotoxin, DA, produced by Pseudo-nitzschia delicatissima,

inhibits growth of another diatom, S. marinoi, only slightly under low (perhaps

limiting) concentrations of Fe, (0.18 µmol L-1), but much more

strongly when Fe was replete (~18 µmol L-1) for diatom growth. DA

also inhibited growth of S. marinoi, while slightly stimulating growth by P.

delicatissima. In the experimental work of Prince et al. (60) (2013), it was

not clear whether P. delicatissima actually produced DA, like its congener, P.

seriata. If it does, the DA might then play two roles: firstly, favouring diatoms

that produce it; secondly, inhibiting competing phytoplankton possibly by

scavenging Fe, and by poisoning potential predatory zooplankton.

9. Mucus trophic structures ("mucus traps").

Rather like terrestrial web-weaving spiders, many

marine organisms feed using structures of polymeric mucus that entrap passing

prey by more or less sticky polymers that in some cases are toxic as well,

killing, or just immobilizing the prey.

Some multi-cellular zooplankters release mucus to

the environment, and appear to provide manure and "garden" their prey

before eating it. The harpacticoid copepod, Diarthrodes nobilis,

secretes mucus fibres through vents in its carapace. It then weaves these

fibres to produce an enmeshing capsule, to which adds its own faeces. This allows

prokaryotes to multiply on the capsules, which are then ingested by the copepod

(61) (Hicks & Grahame, 1979). While it is unclear how much of the mucus

remains in the environment, the authors suggest this "gardening", on

"mucus-traps" is analogous to procedures previously described in

marine nematodes (62) (Riemann & Schrage, 1978).

Mucus traps produced by protists are structured in

different ways. For example, the dinoflagellate genus, Dinophysis,

produces various toxins, including okadaic acid, pectenotoxin (PTX2) and

dinophysistoxin 1b (DTX1b) but from calculations of amount secreted

extracellularly, Nielsen et al. (63) (2013) calculated that field

concentrations would have been too low to support the idea that these toxins

act as allelopathic agents. Instead, the dinoflagellate, Dinophysis

acuminata, uses "mucus threads" to trap its prey, the ciliate, Mesodinium

rubrum, which is an obligate part of its mixotrophic life cycle (64) (65)

(Ojamäe et al., 2016; Jiang et al., 2018).

Ostreopsis cf. ovata cells produce

collective benthic webs of sticky mucous fibrils associated with the toxins,

ovatoxin-a, -b, -c, -d/e and putative palytoxin(66) (Honsell et al., 2013).

Organisms that get stuck or entangled on the webs are then attacked, often by

several cells collectively, and devoured.

The planktonic dinoflagellate, Alexandrium

pseudogonyaulax, secretes transparent spheroidal mucous traps, which are

sticky and entrap small flagellates. The trap often remains attached to the

dinoflagellate by its trailing flagellum, then the dinoflagellate engulfs these

prey individually, finally abandoning the spent mucus trap (67) (Blossom et

al., 2012).

In gradients of viscosity significant at the length

scale of cell size, motile cells are expected to be slowed more on their side

in the more viscous water, thus being turned to swim into the more viscous region.

Zones of high viscosity may this act as traps for swimming cells. Such

"viscous traps" are sometimes used by heterotrophic and mixotrophic

protists to catch prey, and in some cases the protists even lace the

high-viscosity zones with lytic toxins (68) (Blossom & Hansen, 2020). Stehnach

et al. (69) (2021), however, observed that in gradients of viscosity the

chlorophyte, Chlamydomonas, uses viscophobic turning to actually steer

their swimming away from zones of higher viscosity. This behaviour would allow

these flagellates to avoid such viscous traps. It also implies that they are

able to sense viscosity and the direction of viscosity gradients, a capability

reminiscent of that of diatoms that detect and react to turbulence fields (70)

(Falciatore et al., 2000). (See section 13.)

10. Mucus as a retention tool

At the ecosystem scale, endosymbiotic algae in the

coral polyps, the zooxanthellae, account for most of the reef's primary

production (PP). In the Great Barrier Reef, for example, half of this PP is

exuded by the polyps as mucus. This mucus traps organic matter from the water

column, settles and carries energy and organic matter to the reef sediments.

Dissolved mucus (~50-80% of the total mucus) is filtered through the lagoon

sands, where it is quickly (~7%/h) degraded. Undissolved mucus aggregates trap

particles, increasing their organic C and organic N by 2 orders of magnitude

within 2 h. Currents concentrate these aggregates into the lagoon. Coral mucus

thus provides light energy, harvested by the zooxanthellae and trapped

particles to the heterotrophic benthic community of the reef (71) (Wild et al.,

2004). Filtration of DOM and POM by reef sponges may significantly add to the

reef-scale trapping of OM (72) (de Goeij et al., 2013). This constitutes a

recycling loop that retains energy and nutrients within reef ecosystems, known

for their outstandingly high biodiversity and productivity. Evolutionary

processes and structures within the community-scale genome of coral reefs

deserve investigation.

11. The roles of cross-linked gels, rheological changes and reactive oxygen species in toxicity to fish

The sulphated amino acid, cysteine and its

derivative acetyl-N-L-cysteine (NAC) are mucolytic and antioxidant. In

human medicine, the mucolytic effect of NAC is based on the presence of the

free sulphydryl group (—SH), that opens up disulphide bonds (S—S) of the

high-molecular-weight glycoproteins of human mucus, thus reducing the viscosity

and elasticity of the mucus. NAC can also lyse DNA in sputum. NAC is also a

direct and indirect antioxidant. The direct effect is produced by the free

sulphydryl group, which is a source of electron donors that inactivate (i.e.

scavenge) reactive oxygen species (ROS). NAC scavenges •NO2,

CO3•-, and thiol radicals quickly, but O2•-,

H2O2 and peroxynitrite only slowly and O2 or

NO not at all (73) (74) (Samuni et al., 2013; Calzetta et al., 2018).

Yang and Albright (75) (1994) sought treatment for

coho salmon, Oncorhynchus kisutch, killed by blooms of the diatom, Chaetoceros

concavicornis. This species bears sharp, pointed spines that are believed

to irritate the gills and induce them to produce excess mucus. This mucus is a

proteinaceous material which consists mainly of mucopolysaccharides, with the

long, interconnected, fibrous molecules occurring within a gel. The physical

properties of mucous secretions are largely determined by the high molecular

weight glycoproteins which consist of a protein backbone with many

oligosaccharide side chains, often called mucin. The peptide chain of mucin

contains some non-glycosylated regions, which contain many cysteine residues.

Many mucous glycoproteins are composed of polymerized glycoprotein subunits

through the formation of disulphide bonds in the non-glycosylated region of

each protein core, probably involving interaction between adjacent cysteine

residues which results in a network of matted molecules. Yang and Albright

found that salmon administered L-cysteine ethyl ester (LCEE) in their feed

showed increased survival. Since cysteine and its derivatives, NAC and cysteine

L-cysteine ethyl ester (LCEE) can break S=S bonds and thus fluidify mucus,

including mucus secreted by gills (76) (Powell et al., 2007), Yang and Albright

concluded that this effect was responsible for reducing mortality. NAC, also

included in feed, was additionally found to reduce the toxic effect to fish of

cylindrospermopsin, a toxin produced by several harmful cyanobacteria (77)

(Gutiérrez-Praena et al., 2014).

After finding that gas bubbles were preventing from

rising in a bloom of the fish- and invertebrate-killing dinoflagellate, Karenia

mikimotoi (also then known as "Gyrodinium aureolum" or

Gymnodinium nagasakiense) (78) (Jenkinson & Connors,1980), and

measuring the viscoelasticity of cultures of the different species of

phytoplankton (79) (Jenkinson, 1986), Jenkinson(80) (81) (1989) modelled that K.

mikimotoi could slow flow and thus reduce O2 supply, thereby

suffocating the fish when present in sufficient concentration. Jenkinson &

Arzul (82) (80) (1998, 2002)) found that found that cultures of K. mikimotoi,

and the fish-killing raphidophyte, Heterosigma akashiwo, flowed

through fish gills more slowly than culture of the harmless haptophyte, Pavlova

lutheri, which itself did not slow flow relative to that of pure culture

medium. H. akashiwo showed more variable results than either K.

mikimotoi or P. lutheri, suggesting that the EPS it produced was

more heterogeneous. The relationship between flow rate and hydrostatic pressure

difference over the gills suggested that K. mikimotoi and H. akashiwo

added significant amounts of gel-like EPS to their ambient milieu, but that

P. lutheri did not. In addition, however, K. mikimotoi was found to

produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) (82) (80) that contribute haemolytic

toxicity(83) (Gentien et al., 2007), that is assayed by measuring the toxin's

lysis of red blood cells. K. mikimotoi isolated from European waters

(France and Ireland) may be more active rheologically than that from East Asian

waters. The term, "rheotoxity" was used by Jenkinson & Arzul (82)

(2002) to mean "toxicity" (i.e. harm) done to organisms by increased

viscoelasticity. An allied meaning is local increase the concentration of

chemical toxins again by increases in viscoelasticity thus reducing dispersal

(79).

Harmful algae other than Karenia mikimotoi

that produce conspicuous amounts of observed mucus, measured increases in

viscosity and/or foam include blooms of Karenia species, mainly K.

selliformis (84) (Orlova et al., 2022), the dinoflagellates, Margalefidinium

(= Cochlodinium) polykrikoides (85) (Kim & Oda, 2010) Ostreopsis

cf. ovata (86) (Berdalet et al., 2017) and the haptophytes, Phaeocystis

globosa (87) (88) (Seuront & Vincent, 2008; Kang et al., 2020), P.

pouchetii (89) (Balkis-Özdelice et al., 2021) and P. antarctica

(90) (Seuront et al., 2010).

In July 1985, at Caño Island, close to the Pacific

coast of Costa Rica, massive mortality of corals occurred, along with that of many

species of fish (including scarids, acanthurids, pomacentrids, tetradontids and

balistids), crabs and gastropods (91) (Guzman et al., 1990). The plankton

contained 8.3 × 105 live cells and >3 × 106 cells in

total. The dinoflagellates, Margalefidinium catenatum comprised

97% and Gonyaulax monilata (=Alexandrium monilatum) 1%. In

October and November 1985 at Uva Island, close to the Pacific coast of Panama,

about 300 km SE of Caño Island, a red-brown bloom of dinoflagellates lasted

several days. Dinoflagellates and viscous foam co-occurred, suggesting to the

authors that the former had produced the latter. Pocilliporid corals were found

bleached. The authors concluded that the mortality of the reef organisms at

Caño and Uva Islands was most likely caused by adhering of the mucus and, in

the case of polyps, interference with their expansion, although chemical

toxicity and oxygen depletion may also have contributed (91) (Guzman et al.,

1990).

Kim et al. (92) (2002) investigated toxicity in M.

polykrikoides and in the raphidophyte, Chattonella marina, using

human epithelial carcinoma (HeLa) cells as target. In culture, growth of both

species was at first exponential, reaching a plateau phase. After 12 days,

cultures of M. polykrikoides and C. marina the polysaccharide

contents increased to reach respective concentrations of 47 and only 4 µg/ml

glucose equivalent. The M. polykrikoides cultures became noticeably more

viscous, but the C. marina cultures did not. Nevertheless, as antiviral

activity had been previously reported in M. polykrikoides mucus (25)

(Hasui et al., 1995). Kim t al. (92) ((2002) proposed that cytotoxic agents may

have contributed to ichthyotoxicity by M. polykrikoides.

During extensive blooms of M. polykrikoides

around Oman and Muscat, associated with the deaths of hundreds of tons of fish

and shellfish, Al Gheilani et al. (93) (2012) reported that while strong odours

occurred, thought to be caused by methyl sulphide, no toxicity was detected in

mouse tests. Scanning electron microscopy, however, showed mucus proliferation,

which might have clogged gills, and fish gills also appeared damaged.

Working on M. polykrikoides from South

Korea, Lee et al.(94) (1996) conversely showed haemolytic activity in both the

water-soluble and chloroform-soluble fractions isolated from methanol extracts

of M. polykrikoides. Yet C.S. Kim et al.(95) (1999) found that M.

polykrikoides, also isolated from South Korea, produced high quantities of

reactive oxygen species (ROS), which they suggested was the primary cause of

fish mortality, through damage to gills. Kim and Oda (85) (2010) investigated

the fish-killing mechanisms of Chattonella marina and M.

polykrikoides from the Yatsusiro Sea, Japan. Their results suggested that C.

marina has an NADPH-dependent superoxide generation system in its

glycocalyx. Their results also suggested that C. marina continuously

releases H2O2 into the medium during culture, whereas M.

polykrikoides may not release H2O2, at least under

normal physiological conditions. Their results suggest that continuous

accumulation of discharged glycocalyx on the gill surface occurs during C.

marina exposure, which may be responsible for the ROS-mediated severe gill

tissue damage leading to fish death. Compared to C. marina, the levels

of O2– and H2O2 detected in Margalefidinium

polykrikoides were only trace amounts. Both lectins and mucus prepared from

fish skin and gills of yellowtail from C. marina, but not from M.

polykrikoides, when administered separately, produced markedly

increased levels of O2- in C. marina, but

not in M. polykrikoides. Further results suggested that the O2-

generation system of C. marina is located on the cell surface, whereas

only slight evidence of cell-surface generation was shown in M.

polykrikoides. Evidence was shown, however, for the production of H2O2

in both species. Cell-free aqueous solutions prepared from both C. marina

and M. polykrikoides were tested on HeLa cells as target. After 24h

treatment with 10% final concentration of each extract in α-minimal essential

medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, cytological changes took place on the

HeLa cells and colony formation was reduced, whereas corresponding extract from

C. marina produced almost no effect. Kim & Oda (85) (2010) suggested

that the difference between Lee et al.’s (94) (1996) findings and their own

could have reflected differences in strain characteristics.

Flores-Leñero et al. (96) (2022), studying

ichthyotoxicity induced by the raphidophyte, Heterosigma akashiwo, in

Patagonian fords, found that ROS and polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) was too

weak to explain the fish kills that occurred, and the authors suggested that

further studies should explore other fish-killing mechanisms, such as the

production o mucus or extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). These results

may reflect the conclusions of Yamasaki et al. (97) (2010) that the role of

PUFAs and ROS in H. akashiwo blooms may be rather part of a suite of

non-lethal signalling molecules controlling marine microbial community

structure and function. (See sections 1 and 3).

Blooms with the presence of either of the

dinoflagellates, Gonyaulax fragilis or G. hyalina, have been

associated with viscous/slimy water and foam, frequently associated with mass

mortality of marine organisms. Such phenomena have been recorded from: Sea of

Marmara, Turkey (G. fragilis - foamy mucilage) (89) (Balkis-Özdelice, et

al., 2021); Tasman Bay, New Zealand (98) (MacKenzie et al., 2002); Northern

Adriatic (G. fragilis - mucilaginous masses) (99) (100) (Honsell et al.,

1992; Pompei et al., 2003). G. fragilis and G. hyalina may have

been confused by some authors, as they are similar, but separate species (101)

(Carbonell-Moore & Mertens, 2019). Both produce copious mucus from their

apical pore, resulting in noticeable mucilage in the field even at cell

concentrations as low as several thousand cells per litre.

Riccardi et al. (102) (2010) studied the role of G.

fragilis in producing mucilage events in the N. Adriatic, as well as

sterols as potential lipid biomarkers associated with this mucus. They also

extracted DNA from G. fragilis, and using PCR to characterize it,

successfully developed a species-specific DNA probe. In culture,

moreover, G. fragilis was associated with the 4α-methylsterols. That

association between G. fragilis and specific sterols was found not to be

clear in N. Adriatic mucilage-rich field samples was ascribed to rapid decay or

transformation of the dinoflagellate cells and of the sterols. However, the

authors suggested that in future, rapid genomic detection coupled with

identification of phytoplankton cells in the field could be used to investigate

their association with lipid biomarkers, such as sterols.

The dinoflagellate, Karlodinium arminger produces

karlotoxins 1, 2, 8 and 9, that have all been implicated in fish kills (5)

(Brown et al., 2019). This toxin lysed trout gill cells with a LC50

of 125 nM, and it showed a somewhat higher LC50 of 400 nM for the

copepod Acartia tonsa, a potential predator. Huge numbers of algal toxins,

particularly those harmful to humans, have been revealed in the last 20-30

years (reviewed by (30) (5) Schwartz et al., 2016; Brown et al., 2019). While

further details are outside the present paper’s scope, evaluating the genes

associated with these toxins is should be given priority.

Species of the dinoflagellate genus, Dinophysis,

produce various toxins, including pectenotoxin 2 (PTX2) and dinophysistoxin 1b

(DTX1b) (63) (Nielsen et al., 2013). According to Schwartz (30) (2016),

however, calculated field concentrations would have been too low to allow to

support the idea these toxins act as allelopathic agents.

12. Mechanisms of killing microbes

Direct killing may be the strongest signal. Some

bacteria produce toxins that are lethally toxic to microalgae. Hu et al. (107)

(2019) found that algicidal bacterium, CZBC1, is lethal to the cyanobacteria, Oscillatoria

chlorina, O. tenuis and O. planctonica, to the extent that the authors have

patented culturing these bacteria to control cyanobacteria in aquaculture

facilities. Hu et al. (107) (2019) also reviewed the effects of other algicidal

bacteria on microalgae, including cyanobacteria. Bacteria of the genera, Cytophaga

and Saprospura, contact and lyse dinoflagellates and diatoms. A strain of Pseudomonas

putida kills the diatom, Stephanopyxis, by direct alginolysis, but most

algicidal bacteria act indirectly by secreting algicidal compounds. Bacillus strain

LZH-5 from Lake Taihu, China, acts strongly on Microcystis aeruginosa.

Concerning the size of the signalling (toxic)

molecules, the marine bacterium, Bacillus cereus Strain CZBC1, produces

an alginolytic compound retained by a 10 kDa filter (107) (Hu et al., 2019). On

the other hand, Lee et al. (108) (2000) found that Pseudoalteromonas Strain

A28 produces a serine protease activity responsible for algal lysis, but

they also had DNase activity; the supernatant from Strain A28, which passed

through a 10-kDa filter could kill the diatom, Skeletonema costatum. In

addition, Hu et al. (107) (2019) showed that that Strain CZBC1 lysed O.

chlorina and O. tenuis by direct alginolysis, while its extracellular products

lysed O. planctonica. Various authors cited by Hu et al.(107) (2019) showed

that algolytic effects of bacteria are concentration-dependent.

13. Quorum sensing

Quorum sensing (QS) is a density-dependent communicating

mechanism that allows organisms to regulate a wide range of important processes

and can be inhibited by quorum quenching (QQ), for example in marine organic

aggregates (MOAs) (109) (Su et al., 2021) and probably also at larger scales.

Falciatore et al. (70) (2000) may have weakened Svedrup et al.’s (110) (1942)

old paradigm that plankton are passive and incapable of resisting physical

forces at any scale. Reviewing post-Sverdrup findings that "[some]

plankton control buoyancy, local fluid viscosity and life cycles",

Falciatore et al. (70) (2006) showed experimentally that diatoms detect and

respond to physicochemical changes in their environment using sophisticated

perception systems based on changes in cytoplasm concentrations of Ca2+

as a second messenger (111) (Endo, 2006).

Microbes communicate with each other using

diffusable molecules such s N-acetylhomosereine lactones (AHL). Communication

of the information in a signal requires sensing of the signal and it is not

clear whether the different types of sensing use secondary messengers sensu

Endo (111) (2006). Nevertheless, these different signals are likely

physiological and behavioural cell-density-dependent gene regulators (112)

(Ianora et al., 2006), involving quorum sensing and controlling microbial

processes.

Whether in bacteria, algae or metazoans, tighter

spatial association will increase intensity of interactions, as well as

reducing the distances and, mostly, the times of signal transmission (113)

(Jenkinson and Wyatt, 1992), whether by diffusion or by radiation, of

information agents such as pheromones, light, sound or other electrical or

mechanical signals. Association may be effected by attractive behaviour or by

rheological means, such as increasing the viscosity or the yield stress of the

ambient medium. When yield stress is larger than the shear stresses tending to

deform the ambient medium, the spatial distribution of particles, such as

organisms, in the medium is gelled. Even when the yield stress is less than the

ambient mechanical stresses, the increases viscosity will slow the medium's

deformation and hence dispersion of the particles and molecules.

Modification of the mechanical (rheological)

properties, such as viscosity (31) (54) (114) (88) (Jenkinson & Sun, 2010;

Guadayol et al., 2020; Seuront et al., 2007; Kang at al., 2020), of the

transmitting medium will also tend to reduce the intensity of signal

transmission. Such modification is largely carried out by secreted EPS,

particularly that bearing saccharide groups. Such rheological modification by

EPS will therefore also modify the signals that signalling molecules, including

toxins, transmit. Such EPS may thus be considered to include "auxiliary

signalling molecules", which participate in niche engineering(115) (116)

(117) (109) (110) (Hastings, 2007; Reddington et al., 2020), formerly called

"physical environmental management"(118) (Jenkinson and Wyatt).

MOAs may be considered as 3D equivalents of marine

biofilms (MBs) (119) (120) (8) (Camacho-Chab et al., 2016; Sretenovic et al.,

2017; Wurl et al., 2017). In MOA- and BF-associated prokaryotes, including the

Gram-negative alphabacterium, Paracoccus carotinifaciens, and the

gammaproteobacterium, Pantoea ananatis, resistance to viral infection and to

protozoan predation is achieved by secretion of various homosereine lactones

and ammonium, respectively(121) (122) (109) (Jatt et al., 2014; Decho &

Guttieriez, 2017; Su et al., 2021). In the bacterium, Vibrio cholerae, living

in biofilms, resistance to protozoan grazing is effected by secretion of the

metabolite at concentrations of up to 3.5 mM, which was found to reduce

concentrations of the protistan grazer, Rhynchomonas nasuta, by >80% (123)

(Sun et al., 2015).

By contrast, other bacteria, including the fish

pathogen, Vibrio anguillarum, defend against viral (phage) infection by

increasing expression of the ompK gene, which correlates with the degree of

cell aggregation, being low in free-living variants (124) (Tan et al.,

2015).The gene, ompK, produces N-acylhomoserine lactone (AHL) a molecule with

QS signalling and many metabolic functions, and there may thus be a link among ompK,

AHL and aggregation. So far, however, no causal mechanism among ompK, AHL and

aggregation has been demonstrated. . Indeed, investigation of which genes are

involved in producing enzymes involved in producing sugars and assembling them

into polysaccharides such as EPS, as well as in EPS destruction, either in pro-

or eukaryotic aquatic, single-celled organisms, appears to have started only

recently (109) (Su et al., 2021).

AHLs are probably the most intensively studied

class of mediators in cell-density-dependent gene regulation (112) (125)

(Ianora et al., 2006; Pappas et al., 2004), and have been found in bacterial

biofilms and marine snow, in which it is believed that bacteria, interacting

with ambient pressures and constraints, control its form and phenotypic traits

(126) (127) (Gram et al., 2002; Parsek & Fuqua, 2004). In biofouling,

surface sensing via AHLs of bacterial biofilms is the initial step in the

settling of the macroalga, Ulva (128) (129) (Tait et al., 2005; Wheeler et al.,

2006).

Outside of biofilms and MOAs, microalgae, too, may

alter behaviour in multi-celled organisms. Increases in water viscosity due to

secretion of polymers by the haptophyte, Phaeocystis globosa, were observed to

make swimming patterns in the copepod, Temora longicornis, more compact (87)

(Seuront & Vincent, 2008), while the same species reduced measured feeding

rates and filtering rates in Temora stylifera (130) (Li et al., 2021).

In bacterially-dominated biofilms, reviewed by Karn

et al. (49) (2020) for their role in promotion or inhibition of corrosion,

carbohydrates are generally the most abundant constituents, accounting for

40-95% by mass, while proteins typically contribute 1-60%, lipids 1-40%and

nucleic acids 1-10%. The biofilm matrix acts as a recycling centre, by

preventing the molecular products of live cells from dispersing and becoming

lost to the consortium (131) (122) (Flemming and Wingender, 2010). These

products include DNA, which could represent a reservoir of genes for horizontal

gene transfer over small distances. Proteins, along with humic substances,

might play a role as electron donors or acceptors by forming bacterial pili and

nanowires. Modulation of rheological properties in biofilms, such as binding

and stabilization, which affect retention of enzymes, may take place mainly by

interactions with polysaccharides and proteins in the biofilm in reaction to

mechanical forces, including those caused by deformation in the surrounding

milieu (132) (131) (Hohne et al., 2009; Flemming and Wingender, 2010).

In a study related to photo-aggregation related to

reactive oxygen species (ROS), Sun et al.(133) (2019) found that MOA size was

positively related to protein/carbohydrate (P/C) ratio. The authors measured

MOA size after ultrafiltration through 0.2-µm polycarbonate filters, which are

hydrophilic, and allowing the polymer particles to re-form spontaneously in the

filtrate, indicating that the inter-protein bonds were stronger than

inter-polysaccharide bonds. In this respect, microrheological measurement

carried out near phytoplankton cells (54) (Guadayol et al., 2020) found that

viscosity increased by up to a factor of 2 to 5 at distances of 2 to 5 µm from

the cell, typically declining to a factor of 1.2 at 10 £m from the cell.

Furthermore, Stehnach et al. (69) (2021) report viscophobic turning in the

flagellate, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Such behaviour might be critical

to avoid being slowed down or trapped in mucus-reinforced zones of high

viscosity, such as mucous traps (67) (96) (Blossom et al., 2012).

Like marine organic aggregates (MOAs), sewage

sludge organic aggregates (SOAs) consist mainly of bacteria and diverse debris

held together with loosely-bound EPS, in a slimy matrix of closely-bound or

unbound EPS. The more concentrated nature of SOAs sewage sludge compared with

the ocean, together the need to dewater it for economical transport and

disposal, drives lively research activity on the rheology and surface science

of SOAs (134) (Zhang et al., 2018), as well as on ecological chemistry of SOAs

and biofilms (135) (49) (Lear, 2016; Karn et al., 2020). This activity provides

results and expertise with a strong potential to inspire and guide research on

MOAs.

14. Scales (granulometry) of toxicity

The term, toxicity, is usually used in the sense of

causing harm by toxic molecules to living organisms. This implies one length

scale of the chemical action (nm) and another at that of a cell (1-100 µm) or

even of multicellular organisms. Toxic effects of molecules produced genomes

may act at an environmental scale of km to 1000s of km and be more difficult to

identify. In both spontaneously aggregated OM (136) (137) (Verdugo, 2012,

2021), or in biologically produced mucus, fluid flow and often molecular

diffusion are reduced, while physical density may be increased or decreased

(138) (139) (Drost-Hansen, 2006; Mari et al., 2008).

Much research is currently under way on the

allelopathic effects of polyunsaturated aldehydes (PUAs), which act as

signalling compounds (5) (Brown et al., 2019), which some diatoms release

amongst the copious DOM, particularly towards the end of their blooms. Bartual

et al. (140) (2017), working with laboratory blooms of the diatom, Thalassiosira

rotula, studied the effect of adding PUA (2.5 µM mixture of three PUAs, 2E,

4E-heptadienal; 2E,4E-octadienal; 2E,4E-decadienal) on the aggregation of

diatom-secreted TEP into OAs. They found that when the presence of PUA resulted

in larger OAs and they suggested that PUA acts as glue, consolidating the OAs.

Since larger OAs sinks faster as marine snow, the diatom-produced PUA might be

contributing to increased vertical organic flux. The physico-chemical

mechanisms of how these PUAs stick within TEP, as well as the genes responsible

for PUA production require investigation.

15. Hydrophobicity, organic aggregate size and rheology

The polymeric secretions of algae and bacteria

include polysaccharides, proteins, lipids and nucleic acids. Proteins are

amphiphilic: they bear both hydrophilic (polar, wettable) and hydrophobic

(non-polar) domains and they are considered to contribute most of the

hydrophobicity of EPS. In contrast, polysaccharides are mostly hydrophilic

through their polar oxygen groups. An increase in the degree of internal

hydrogen bonding, however, can increase their relative hydrophobicity (52)

(Santschi et al., 2020). Klun et al. (141) (2022) investigated colloidal OM

(COM) secreted in culture by a chlorophyte nanoflagellate,

Tetraselmis

sp., a diatom,

Chaetoceros socialis and a dinoflagellate,

Prorocentrum minimum, all isolated from the Gulf of Trieste. Table 2 summarizes their results. The OM had

been 0.45 µm e-filtered. It was then ultrafiltered through membranes with

nominal molecular-weight cut-off of 5 kDa. The polysaccharide fraction was the

highest in the retentate of

Tetraselmis sp. (61%), while lipids and

proteins each accounted for 19%. In the permeate, protein represented the

highest portion (41%). The

C. socialis retentate and permeate contained

the highest polysaccharide levels (63% and 46%, respectively), followed by proteins

(22% and 36%) and lipids (14% and 16%).

P. minimum retentate and

permeate showed very different compositions of secreted OM, with polysaccharide

proportions of only 32 % and 25%, respectively, compared with high proportions

of proteins (46% and 57%, respectively) and with intermediate proportions of

lipids (22% and 17%, respectively). For all three taxa, the proportion of

polysaccharides was thus higher in the retentate than in the permeate, while

the proportion of proteins was higher in the permeate, while for lipids the

corresponding situation varied. The overall proportion of lipids found in both

the retentates and the permeates was surprisingly high, from 14% to 36%.

Table 2.

Distribution of the integrated main groups of proton resonances (lipids, proteins and carboxyl-rich alicyclic molecules (CRAM), polysaccharides and formate) in 1H MNR spectra (6/ppm), concentrations of Corg. (µmol L-1) in retentates and permeates and % COC from exudates of cultured phytoplankters. Protons that resonated in certain chemical shift range of integrated main groups are in bold (second row). Summarized from ref (141) (Klun et al., 2022).

Table 2.

Distribution of the integrated main groups of proton resonances (lipids, proteins and carboxyl-rich alicyclic molecules (CRAM), polysaccharides and formate) in 1H MNR spectra (6/ppm), concentrations of Corg. (µmol L-1) in retentates and permeates and % COC from exudates of cultured phytoplankters. Protons that resonated in certain chemical shift range of integrated main groups are in bold (second row). Summarized from ref (141) (Klun et al., 2022).

| |

Lipids |

Proteins and CRAM |

Polysaccharides |

Formate |

Corg.

|

% COC * |

| |

HCH2-CH2- |

HC-HCOR |

HC-OH HC-O-C |

HCOO |

|

|

| 6 **/ppm |

0-1.8 |

1.8-3.0 |

3.0-4.6 |

8.0-9.0 |

µmol L-1 |

% |

| |

|

|

Tetraselmis sp. |

|

|

|

| 0.2 µm filtrate |

|

|

|

|

915.1 |

|

| Retentate |

19.4 |

18.8 |

61.4 |

0.4 |

364 |

39.8 |

| Permeate |

35.7 |

40.9 |

20.8 |

2.6 |

507 |

|

| |

|

|

Chaetoceros socialis |

|

|

|

| 0.2 µm filtrate |

|

|

|

|

2285 |

|

| Retentate |

14.4 |

21.9 |

62.9 |

1.1 |

526 |

23.0 |

| Permeate |

16.4 |

36.4 |

45.5 |

1.7 |

1765 |

|

| |

|

Prorocentrum minimum |

|

|

|

| 0.2 µm filtrate |

|

|

|

|

439.3 |

|

| Retentate |

21.8 |

45.6 |

31.9 |

0.8 |

154 |

35.1 |

| Permeate |

17.4 |

56.7 |

24.6 |

1.2 |

418 |

|

16. Molecules, produced by other organisms and associated bacteria, that are toxic and allelopathic to phytoplankton

Vidal-Melgosa et al.(142) (2021) reported a polysaccharide of still unknown structure, called fucose-containing sulphated polysaccharide (FCSP) that appears to be directly secreted by diatoms. Detected by monoclonal antibody technique, it was found abundantly distributed on cell surfaces and spines of the diatom, Chaetoceros socialis, in spring blooms in the Helgoland Bight. It appears to have a complicated structure, and unlike other polysaccharides present, it lasted »10 days in laboratory culture. This suggests that, over a certain concentration, it might be very important in aggregating to particulate organic matter (POM), and thus mediating vertical flux (143) (Denis et al., 2022). This FCSP is strongly negatively charged, and thus form part of the complex of acid polysaccharides secreted by phytoplankton as diverse as dinoflagellates(66) (Honsell et al., 2013) and cyanobacteria(144) (Liu et al., 2015).

Some seaweeds and seagrasses also exert allelopathic action on harmful algae. Laabir et al. (145) (2013) showed that the methanolic and aqueous extracts of the seagrasses, Zostera marina and Z. noltii, inhibited the harmful dinoflagellate, Alexandrium catenella. These extracts contained flavinoids and phenolic acids, which were themselves toxic to A. catenella, The authors suggested that phenolic acids were the likely candidates for allelopathic action, and that increases in A. catenella blooms in lagoons and other French waters may have been partly caused by declines in seagrass beds.

Subsequently, Onishi et al. (146) (2014) showed that only whole-plant extracts of seagrasses, and not exudates, were algicidal. Two strains of Flavobacteriaceae isolated from biofilms on the seagrass leaves show algicidal activity on Alexandrium tamarense. This suggests that the above mentioned findings of Laabir et al.(145) (2013) might have been due to bacteria epiphytic on seagrass, leaves rather than to the seagrasses themselves, particularly as Flavobacteriaceae have been shown be algicidal towards several fish-killing rhaphidophytes, dinoflagellates and diatoms. Similarly in the freshwater Lake Biwa, Japan, the bacterium, Agrobacterium vitis, which colonises surfaces of leaves of the water plant, Egeria densa, is strongly allelopathic to the harmful cyanobacterium, Microcystis aeruginosa, and an increase over several years of E. densa has coincided with a reduction in blooms of M. aeruginosa (147) (Imai et al., 2013).

Bacteria in the mucus phycosphere of the diatom, Skeletonema costatum, and of the dinoflagellate, Scrippsiella trochoidea, were found by Yang et al.(148) (2013) to be able to lyse their host cells, leading to mass deaths of the hosts. The mechanisms for this lysis were not elucidated.

Research on metabolomics in consortia (see section 6), particularly in biofilms, is intense in the fields of biocorrosion (49) (Karn et al., 2020), medicine (149) Qian et al., (2020) and sewage sludge (150) (Kotay & Das, 2010). It appears, however, still too rare in aquatic plankton ecosystem (116) (117) (Reddington et al., 2020). In such biofilm consortia, progress is being made in semi-automated data mining of intra- and extra- cellular DNA to identify gene sets involved in microbial metabolism and production of different molecules. The software is inspired by homologous data mining of texts on the internet. Thakur et al. (151) (2023) have made a promising start on bacterial consortia in biofilms associated with biocorrosion. The technique may be capable of development to mine pro- and eu-karyotic gene sets from ecosystems such as the world ocean, stored in GenBase. Singh(152) (2021) pointed out that in human bodies, as in the ocean, glycoproteins play crucial roles in biological processes like cell signalling, host-pathogen interaction and disease. Glycoproteomics aims to determine the positions and identities of the complete repertoire of glycans and glycosylated proteins in a given cell or tissue. The roles of glycoproteomics in ocean consortia may be analogous, and the links with genes, as least for key processes, should be established. While the main drivers of Thakur et al.'s (151) study may have been the need to understand and control biocorrosion of steel by sulphur-reducing bacteria, and those of the studies cited in Singh’s mini-review are improvement in human health, the purposes of mining ocean-derived data on gene sets might be to understand and control bio-geo-physico-chemical fluxes of matter and energy in the oceans, as well as cell-cell signalling and other interactions and their roles in ecological control (6) Yamasaki et al. 2009).

17. Organic polymers and Gaia

Some molecules polymerize, and the resultant biopolymers strengthen organic aggregates, biofilms and volumes of water with increased viscosity (135) (153) (4) (Lear, 2016; Alldredge et al., 1993; Jenkinson et al., 2015). Biopolymers tend to concentrate at surfaces, particularly in the surface microlayer (SML). Here they will thus tend to change properties including surface tension and 2D viscoelasticity (154) (Williams et al., 1986), as well as 3D viscosity(155) (156) (Carlson, 1987; Zhang, et al., 2003), thus modulating ocean-atmosphere fluxes of various types of matter and energy (157) (Jenkinson et al., 2018). Since organisms are genetically controlled and they participate in the production, metamorphoses and breakdown of these biomolecules, their genomes thus influence oceanic and atmospheric physico-chemical conditions. Where they are harmful, this may be considered toxicity at the scale of the Planetary ecosystem, consistent with evolution of Gaia (158) (159) (Lovelock, 198(158)8; Lenton, 1998) by natural selection of its genes (11) (Dawkins, 2016). An example of such Planetary scale toxicity, at least from an anthropic point of view, is the current increase in atmospheric and oceanic CO2.

18. Polymer modulation of fluxes: discovering the genomes involved.

Fluxes of matter and energy between the ocean and the atmosphere are functions of physical, chemical and biological parameters. In particular, viruses, bacteria sensu lato and eukaryotic protists are expelled towards the atmosphere by bursting bubbles, and may then be carried by updrafts and winds from a few metres(160) (Thornton, 1999) to thousands of km (161) (Hamilton & Lenton 1998). The surface charge and hydrophobicity of cells and non-living matter strongly influences tendency to be expelled(9) (Jenkinson et al., 2021). For species in which such expulsion leads to dispersion and greater Darwinian fitness, it is may represent a pre-adaptation leading to further evolution of hydrophobic/hydrophilic control of ocean-atmosphere flux. Irrespective of the length, time or hyperspace scales at which such natural selection is driven, it will have effects also over other biological and chemical species (collateral effects) in driving ocean-atmosphere fluxes, which are important for climate control (157) (9) (12) (Jenkinson et al., 2018; 2021; IPCC, 2021).

Notably in the SML and biofoam, both important to modulating ocean-atmosphere fluxes of matter and energy, the EPS present is shows different characteristics. The different species and their expressed genes that produce the EPS thus determine the different ways in which EPS modulates these fluxes.

19. Vertical organic flux of OM.

The use of metabolomics and proteomics has already illuminated the mechanisms of biological response to many chemical cues and may be helpful in determining their molecular targets. Overall, the ocean represents a vast source of novel interactions and well as new molecules (30) (Schwartz, 2016). As Schwartz (30) (2016) pointed out, both models and laboratory experiments are needed to evaluate the roles of toxic, allelopathic and signalling interactions in the pelagic. To these interactions might be added those involving modulation of fluxes, diffusion and fluid deformation.

Vidal-Melgosa et al.(142) (2021) showed the importance of fucose-containing sulphated polysaccharide (FCSP), which is secreted by diatoms, particularly Chaetoceros socialis, which produces mucilaginous colonies and which dominated the North Sea blooms they worked on. FCSP was far more resistant than the non-sulphated polysaccharide, laminarin, to degradation by Bacteroidea and Gammaproteobacteria. These organisms encode enzymes for laminarin degradation, and they are key degraders of laminarin in the field (162) (Teeling et al., 2012). Because FCSP is degraded far more slowly than laminarin, Vidal-Melgosa et al. (142) (2021) suggested that C. socialis and other diatoms that secrete large amounts of FCSP, are likely among the key species that modulate vertical carbon flux in aggregates, thus contributing to the sequester of CO2 from the atmosphere.

20. Ocean foam