Submitted:

14 March 2023

Posted:

15 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell carrier synthesis

2.2. Strain and cultivation conditions

2.3. Assay of chlorophyll and extimation of the condition of photosynthetic apparatus

2.4. Analysis of cell lipid fatty acid composition

2.5. Scanning electron microscopy

2.6. Statistical treatment

3. Results

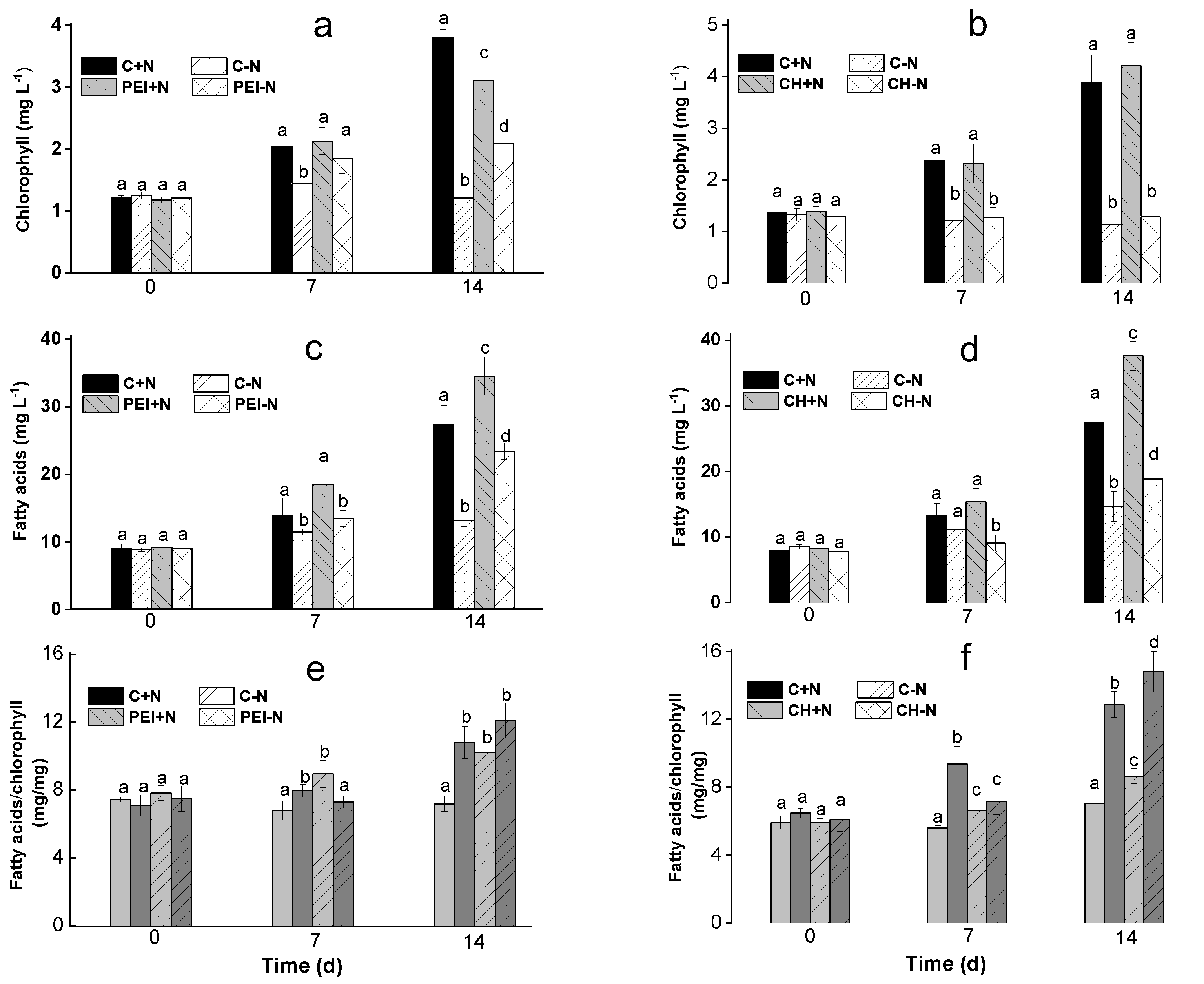

3.1. Changes in the chlorophyll content of the culture

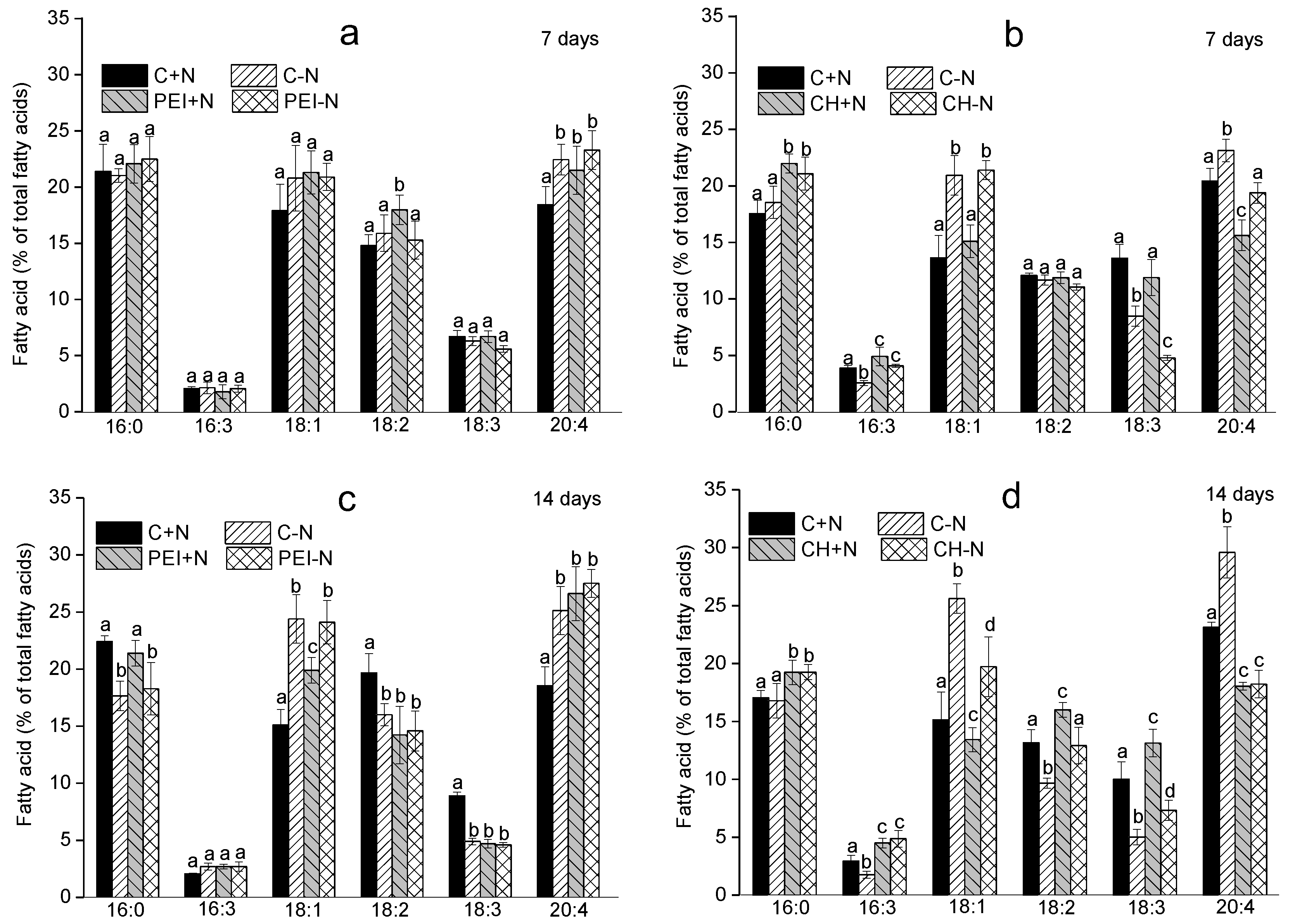

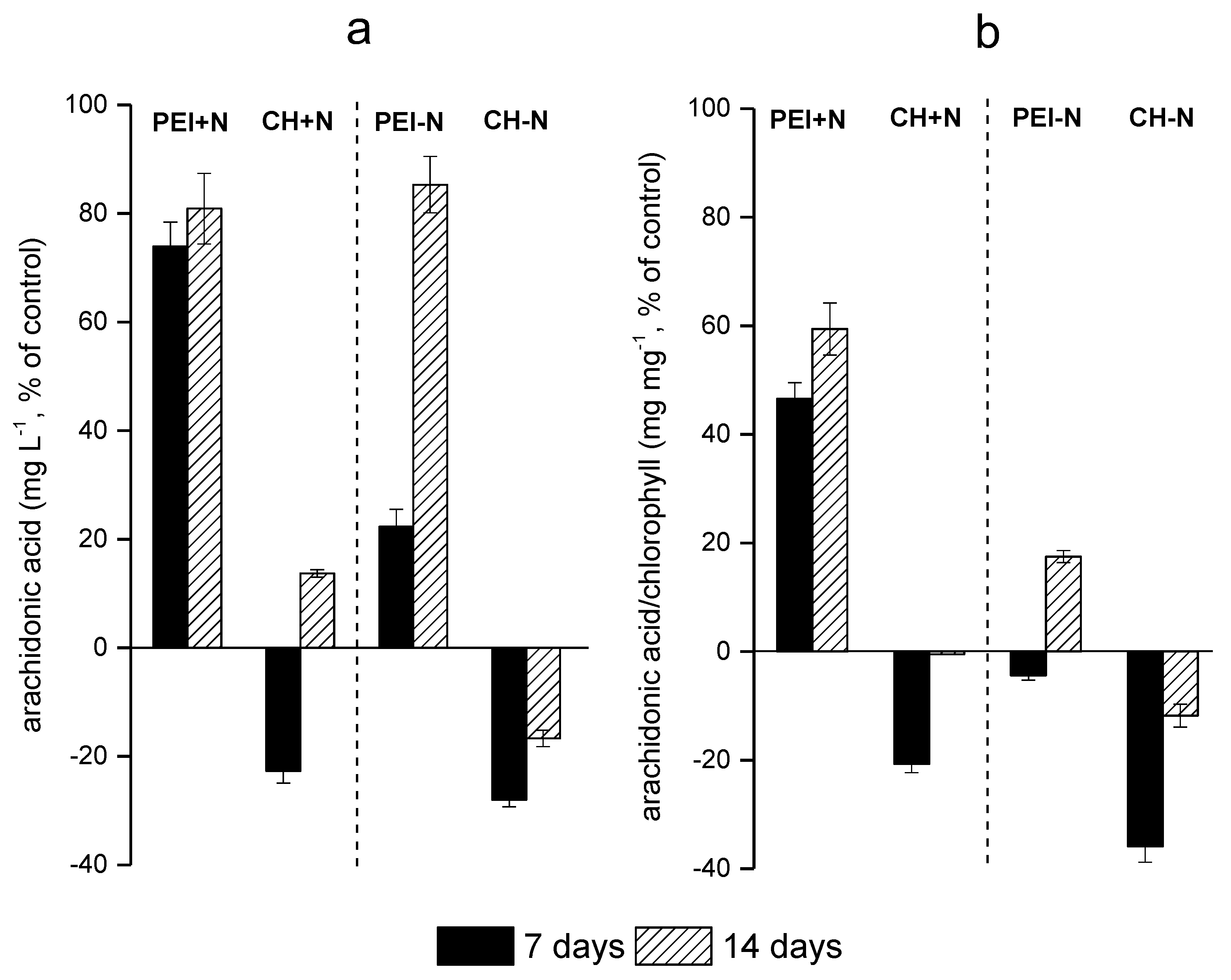

3.2. Effects of immobilization on FA profile of the cells

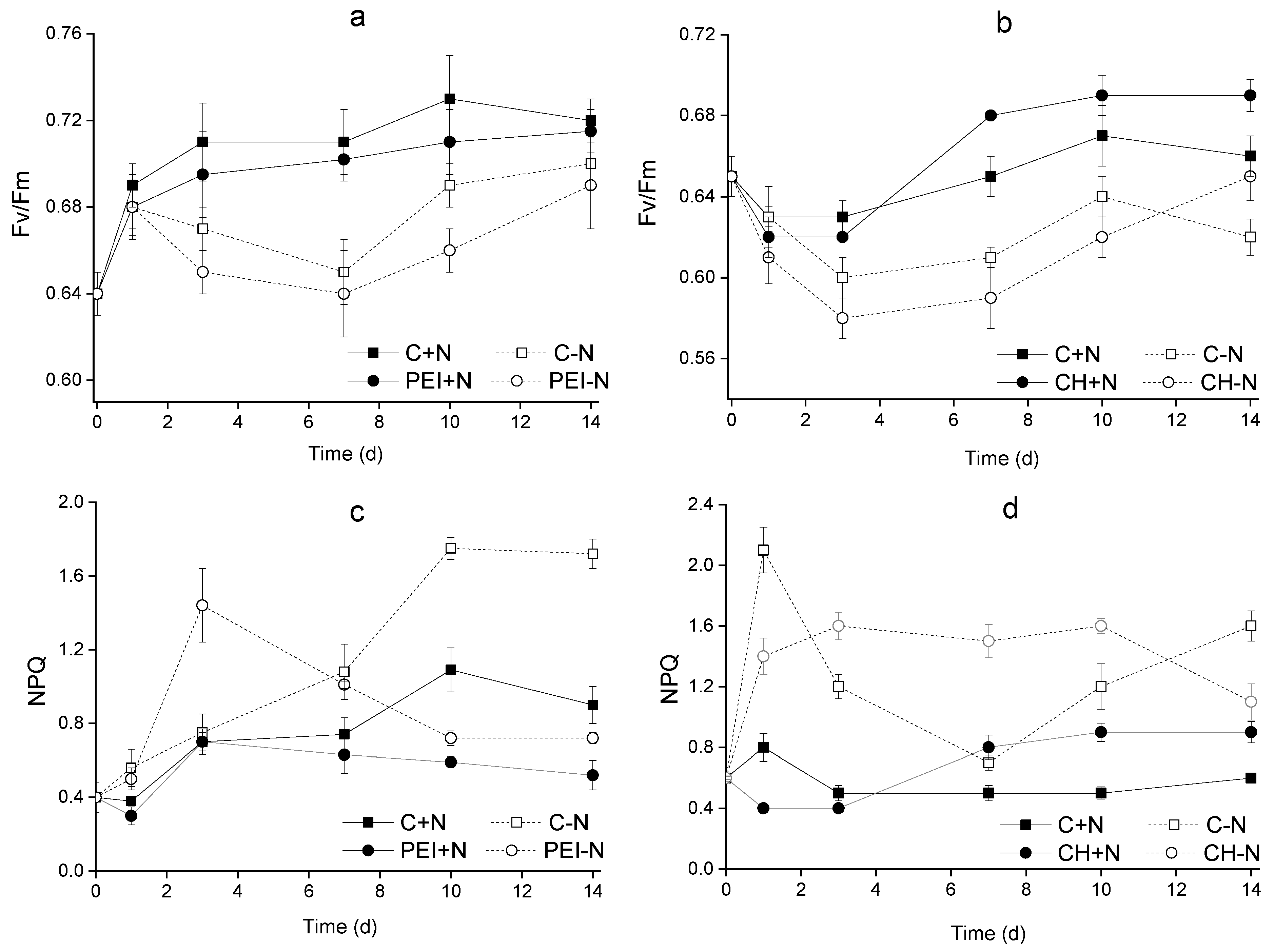

3.3. The Condition of photosynthetic apparatus

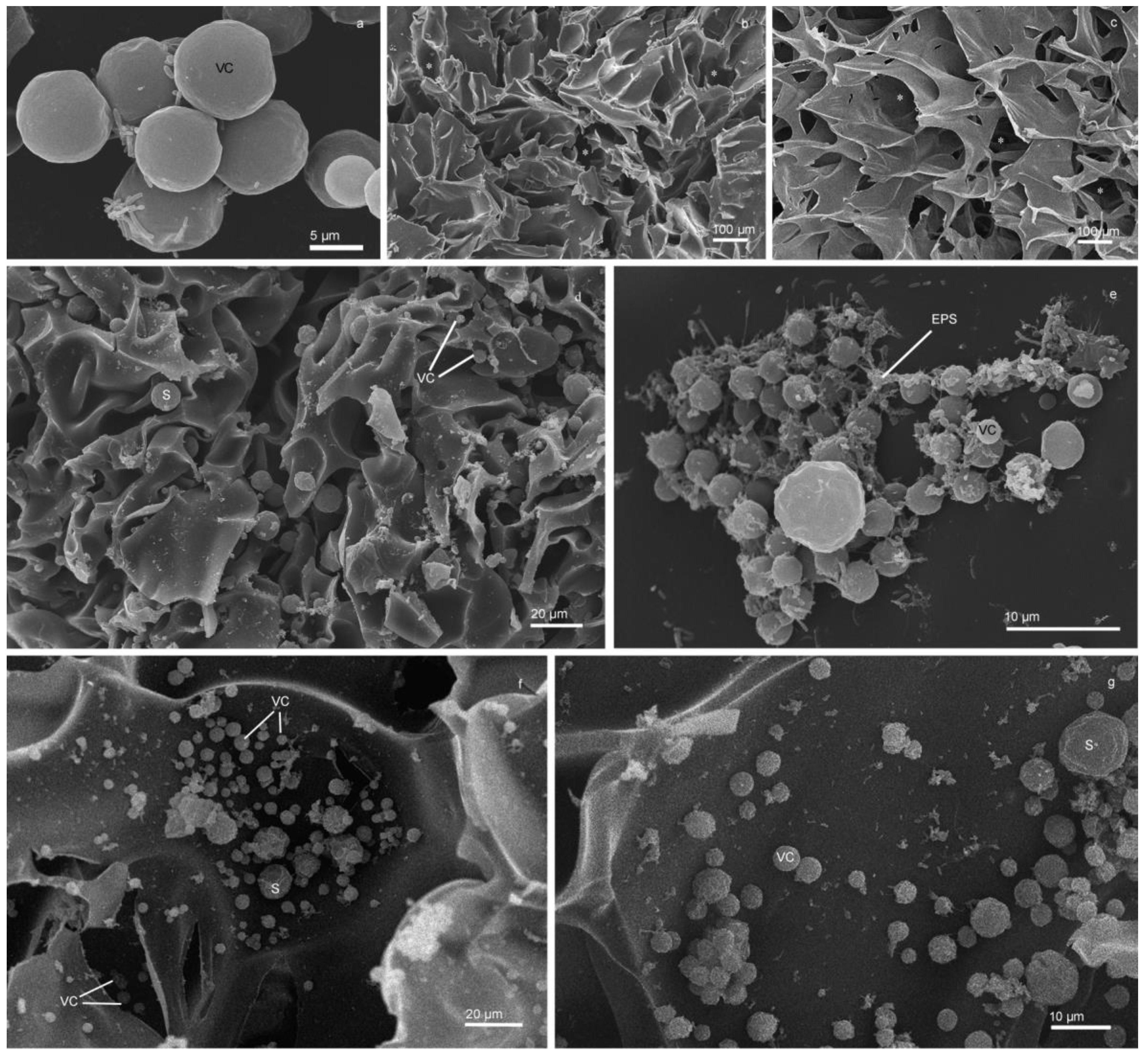

3.4. Changes in the morphology of the cells as elucidated by SEM

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barbosa, M.J.; Janssen, M.; Sudfeld, C.; D'Adamo, S.; Wijffels, R.H. Hypes, hopes, and the way forward for microalgal biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol 2023. [CrossRef]

- Shahi Khalaf Ansar, B.; Kavusi, E.; Dehghanian, Z.; Pandey, J.; Asgari Lajayer, B.; Price, G.W.; Astatkie, T. Removal of organic and inorganic contaminants from the air, soil, and water by algae. Environmental science and pollution research international 2022. [CrossRef]

- Brodie, J.; Chan, C.X.; De Clerck, O.; Cock, J.M.; Coelho, S.M.; Gachon, C.; Grossman, A.R.; Mock, T.; Raven, J.A.; Smith, A.G., et al. The Algal Revolution. Trends Plant Sci 2017. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Z.; Khozin-Goldberg, I. Searching for PUFA-rich microalgae. In Single Cell Oils, 2 ed.; Cohen, Z., Ratledge, C., Eds. American Oil Chemists’ Society: Champaign IL, 2010; pp. 201-224.

- Bigogno, C.; Khozin-Goldberg, I.; Boussiba, S.; Vonshak, A.; Cohen, Z. Lipid and fatty acid composition of the green oleaginous alga Parietochloris incisa, the richest plant source of arachidonic acid. Phytochemistry 2002, 60, 497-503. [CrossRef]

- Khozin-Goldberg, I.; Iskandarov, U.; Cohen, Z. LC-PUFA from photosynthetic microalgae: occurrence, biosynthesis, and prospects in biotechnology. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 2011, 10.1007/s00253-011-3441-x, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Dumancas, G.G. Arachidonic Acid: Dietary Sources and General Functions; nova science publishers, incorporated: 2012.

- Dragos, A.; Kiesewalter, H.; Martin, M.; Hsu, C.Y.; Hartmann, R.; Wechsler, T.; Eriksen, C.; Brix, S.; Drescher, K.; Stanley-Wall, N., et al. Division of Labor during Biofilm Matrix Production. Curr Biol 2018, 28, 1903-1913 e1905. [CrossRef]

- Branda, S.S.; Vik, Å.; Friedman, L.; Kolter, R. Biofilms: the matrix revisited. Trends in microbiology 2005, 13, 20-26. [CrossRef]

- Nozhevnikova, A.; Botchkova, E.; Plakunov, V. Multi-species biofilms in ecology, medicine, and biotechnology. Microbiology 2015, 84, 731-750. [CrossRef]

- Roeselers, G.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.; Muyzer, G. Heterotrophic pioneers facilitate phototrophic biofilm development. Microbial Ecology 2007, 54, 578-585. [CrossRef]

- Costerton, J.W. Overview of microbial biofilms. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology 1995, 15, 137-140. [CrossRef]

- Danaee, S.; Heydarian, S.M.; Ofoghi, H.; Varzaghani, N.B. Optimization, upscaling and kinetic study of famine technique in a microalgal biofilm-based photobioreactor for nutrient removal. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2021. [CrossRef]

- Orfanos, A.G.; Manariotis, I.D. Algal biofilm ponds for polishing secondary effluent and resource recovery. Journal of Applied Phycology 2019. [CrossRef]

- Kesaano, M.; Sims, R.C. Algal biofilm based technology for wastewater treatment. Algal Research 2014, 5, 231-240. [CrossRef]

- Vasilieva, S.; Lobakova, E.; Solovchenko, A. Biotechnological Applications of Immobilized Microalgae. Environmental Biotechnology Vol. 3 2021, 193-220. [CrossRef]

- de-Bashan, L.E.; Bashan, Y. Immobilized microalgae for removing pollutants: review of practical aspects. Bioresource Technology 2010, 101, 1611-1627. [CrossRef]

- Eroglu, E.; Smith, S.M.; Raston, C.L. Application of Various Immobilization Techniques for Algal Bioprocesses. In Biomass and Biofuels from Microalgae, Springer: 2015; pp. 19-44.

- Moreno-Garrido, I. Microalgae immobilization: current techniques and uses. Bioresource technology 2008, 99, 3949-3964. [CrossRef]

- Vasilieva, S.; Shibzukhova, K.; Morozov, A.; Solovchenko, A.; Bessonov, I.; Kopitsyna, M.; Lukyanov, A.; Chekanov, K.; Lobakova, E. Immobilization of microalgae on the surface of new cross-linked polyethylenimine-based sorbents. Journal of biotechnology 2018, 281, 31-38. [CrossRef]

- Romanova, O.; Grigor’ev, T.; Goncharov, M.; Rudyak, S.; Solov’yova, E.; Krasheninnikov, S.; Saprykin, V.; Sytina, E.; Chvalun, S.; Pal’tsev, M. Chitosan as a modifying component of artificial scaffold for human skin tissue engineering. Bulletin of experimental biology and medicine 2015, 159, 557-566. [CrossRef]

- Nuzhdina, A.V.; Morozov, A.S.; Kopitsyna, M.N.; Strukova, E.N.; Shlykova, D.S.; Bessonov, I.V.; Lobakova, E.S. Simple and versatile method for creation of non-leaching antimicrobial surfaces based on cross-linked alkylated polyethyleneimine derivatives. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2017, 70, 788-795. [CrossRef]

- Stanier, R.; Kunisawa, R.; Mandel, M.; Cohen-Bazire, G. Purification and properties of unicellular blue-green algae (order Chroococcales). Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 1971, 35, 171-205. [CrossRef]

- Solovchenko, A.; Merzlyak, M.; Khozin-Goldberg, I.; Cohen, Z.; Boussiba, S. Coordinated carotenoid and lipid syntheses induced in Parietochloris incisa (Chlorophyta, Trebouxiophyceae) mutant deficient in Δ5 desaturase by nitrogen starvation and high light. Journal of Phycology 2010, 46, 763-772. [CrossRef]

- Wellburn, A. The spectral determination of chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. Journal of Plant Physiology 1994, 144, 307-313. [CrossRef]

- Strasser, R.; Tsimilli-Michael, M.; Srivastava, A. Analysis of the chlorophyll a fluorescence transient. In Chlorophyll a fluorescence: a signature of photosynthesis, Papageorgiou, G., Govindjee, Eds. Springer: 2004; pp. 321–362.

- Maxwell, K.; Johnson, G. Chlorophyll fluorescence-a practical guide. Journal of Experimental Botany 2000, 51, 659-668. [CrossRef]

- Folch, J.; Lees, M.; Sloane-Stanley, G. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J Biol Chem 1957, 226, 497–509. [CrossRef]

- Solovchenko, A.; Gorelova, O.; Selyakh, I.; Pogosyan, S.; Baulina, O.; Semenova, L.; Chivkunova, O.; Voronova, E.; Konyukhov, I.; Scherbakov, P. A novel CO2-tolerant symbiotic Desmodesmus (Chlorophyceae, Desmodesmaceae): Acclimation to and performance at a high carbon dioxide level. Algal Research 2015, 399–410. [CrossRef]

- Solovchenko, A.; Khozin-Goldberg, I.; Cohen, Z.; Merzlyak, M. Carotenoid-to-chlorophyll ratio as a proxy for assay of total fatty acids and arachidonic acid content in the green microalga Parietochloris incisa. Journal of Applied Phycology 2009, 21, 361-366. [CrossRef]

- Khozin-Goldberg, I.; Bigogno, C.; Shrestha, P.; Cohen, Z. Nitrogen starvation induces the accumulation of arachidonic acid in the freshwater green alga Parietochloris incisa (Trebuxiophyceae). Journal of Phycology 2002, 38, 991-994. [CrossRef]

- Bigogno, C.; Khozin-Goldberg, I.; Cohen, Z. Accumulation of arachidonic acid-rich triacylglycerols in the microalga Parietochloris incisa (Trebuxiophyceae, Chlorophyta). Phytochemistry 2002, 60, 135-143. [CrossRef]

- Solovchenko, A.; Khozin-Goldberg, I.; Didi-Cohen, S.; Cohen, Z.; Merzlyak, M. Effects of light intensity and nitrogen starvation on growth, total fatty acids and arachidonic acid in the green microalga Parietochloris incisa. Journal of Applied Phycology 2008, 20, 245-251. [CrossRef]

- Solovchenko, A. Physiological role of neutral lipid accumulation in eukaryotic microalgae under stresses. Russian Journal of Plant Physiology 2012, 59, 167-176. [CrossRef]

- Solovchenko, A.E.; Merzlyak, M.N.; Chivkunova, O.B.; Reshetnikova, I.V.; Khozin-Goldberg, I.; Didi-Cohen, S.; Cohen, Z. Effects of light irradiance and nitrogen starvation on theaccumulation of arachidonic acid by the microalga Parietochloris incisa. Vestnik Moskovskogo Universiteta Seriya 16 Biologiya 2008, 49-49.

- Li-Beisson, Y.; Thelen, J.J.; Fedosejevs, E.; Harwood, J.L. The lipid biochemistry of eukaryotic algae. Prog Lipid Res 2019, 74, 31-68. [CrossRef]

- Wacker, A.; Piepho, M.; Harwood, J.L.; Guschina, I.A.; Arts, M.T. Light-induced changes in fatty acid profiles of specific lipid classes in several freshwater phytoplankton species. Frontiers in Plant Science 2016, 7. [CrossRef]

- Guschina, I.A.; Harwood, J.L. Algal Lipids and Their Metabolism. In Algae for Biofuels and Energy, Borowitzka, M.A., Moheimani, N.R., Eds. Springer: Dordrecht, Heidelberg, New York, London, 2013; pp. 17-36.

- Kokabi, K.; Gorelova, O.; Zorin, B.; Didi-Cohen, S.; Itkin, M.; Malitsky, S.; Solovchenko, A.; Boussiba, S.; Khozin-Goldberg, I. Lipidome Remodeling and Autophagic Respose in the Arachidonic-Acid-Rich Microalga Lobosphaera incisa Under Nitrogen and Phosphorous Deprivation. Frontiers in plant science 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Kugler, A.; Zorin, B.; Didi-Cohen, S.; Sibiryak, M.; Gorelova, O.; Ismagulova, T.; Kokabi, K.; Kumari, P.; Lukyanov, A.; Boussiba, S. Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in the green microalga Lobosphaera incisa contribute to tolerance to abiotic stresses. Plant and Cell Physiology 2019, 60, 1205-1223. [CrossRef]

- Klyachko-Gurvich, G.; Tsoglin, L.; Doucha, J.; Kopetskii, J.; Shebalina, I.; Semenenko, V. Desaturation of fatty acids as an adaptive response to shifts in light intensity 1. Plant Physiol 1999, 107, 240-249. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.B.; Park, Y.H.; Jeon, M.S.; Kim, S.; Choi, Y.-E. Polyethylenimine linked with chitosan improves astaxanthin production in Haematococcus pluvialis. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2022, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Yoshitomi, T.; Shimada, N.; Iijima, K.; Hashizume, M.; Yoshimoto, K. Polyethyleneimine-induced astaxanthin accumulation in the green alga Haematococcus pluvialis by increased oxidative stress. Journal of bioscience and bioengineering 2019, 128, 751-754. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).