1. MOTIVATION

In recent years, various additive manufacturing (AM) processes have emerged in the construction sector [1]. The main advantages of AM processes are the high freedom of form and the ability to apply material only where it is required (e.g., for load bearing). Hence, AM processes have the potential to create both, cost- and material-efficient structures. AM processes in the construction sector can be divided into two main groups, namely extrusion processes and selective binding methods [

2,

3].

The selective binding methods include the AM process Selective Paste Intrusion (SPI). With SPI, it is possible to additively produce concrete components by depositing a layer of aggregates and selectively binding them with cement paste. These steps are repeated until the component is finished. Afterwards, the part hardens in the particle bed. The finished component can then be excavated from the particle bed [4 – 7].

Despite the high geometric freedom and the generally high component strength of SPI-produced structures, a strategy to implement reinforcement needs to be developed to produce structural concrete elements [7]. Furthermore, SPI can be fully enhanced by an approach that can produce reinforcement without restrictions in terms of complex geometries. This means that the achievable freedom of form needs to be equal. Consequently, SPI is merged with Wire and Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM) to establish a hybrid AM process for steel-reinforced concrete [8].

WAAM is an AM process in which components are produced layer-wise using arc welding. Moreover, WAAM can provide the geometric freedom required by SPI with comparatively high build rates and a diverse range of functional materials, such as steel or titanium [9].

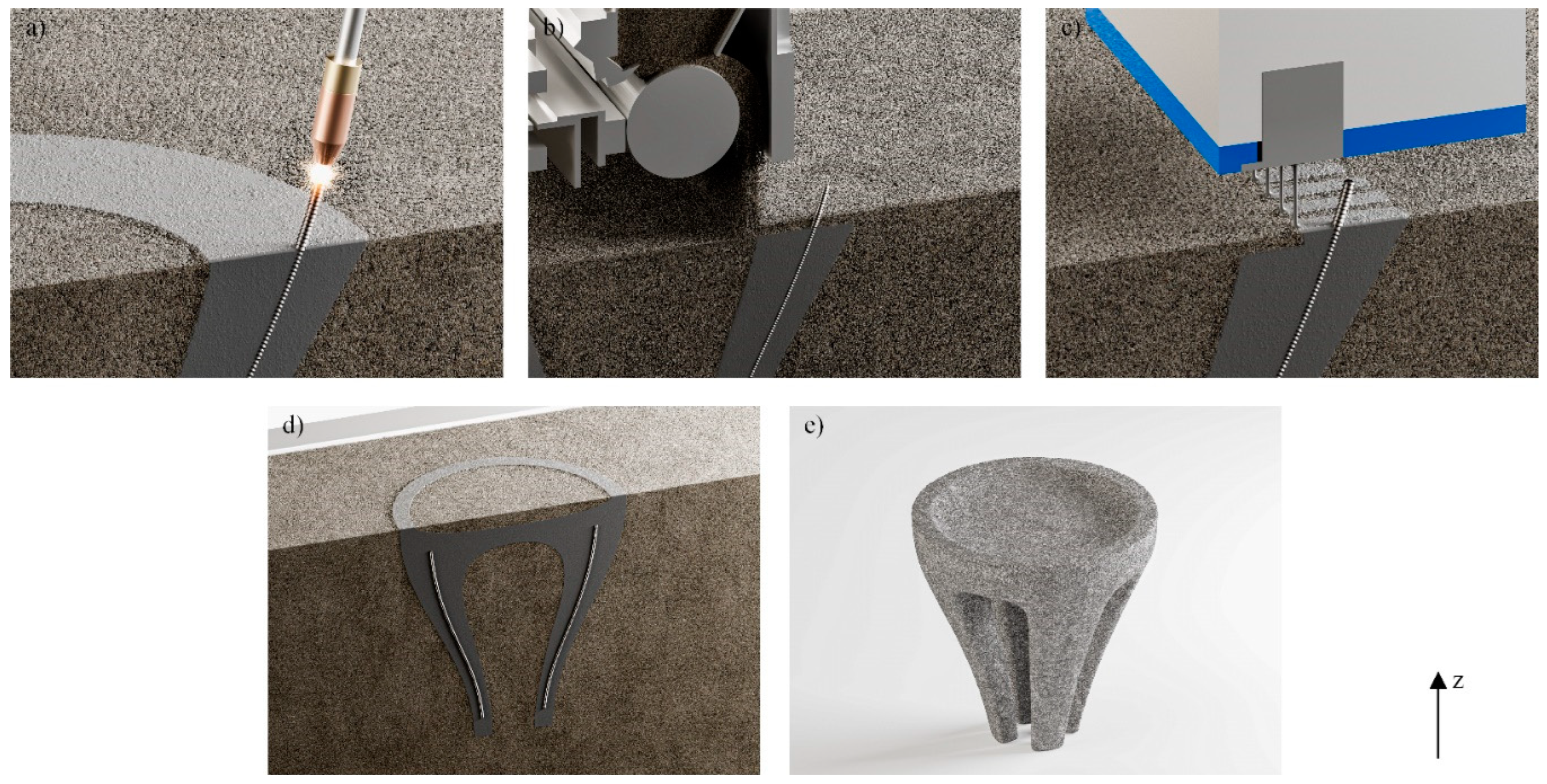

The hybrid process (see

Figure 1) operates by firstly printing a protruding rebar on a surface or previous layer via WAAM (

Figure 1 a)). Subsequently, a layer of aggregate particles is spread upon the surface (

Figure 1 b)) and the cement paste is deposited on the designated areas (

Figure 1 c)). The cement paste then covers the aggregate particles, penetrates the particle bed, and gets in contact with the rebar in the particle bed. The aforementioned procedures are repeated until the structural concrete component is finished (

Figure 1 d)) and can be excavated after hardening (

Figure 1 e)) [8].

However, there are still certain obstacles to overcome for the hybrid process with respect to fresh and hardened concrete properties. WAAM generates high temperatures, resulting in high heat conduction into the particle bed and the cement paste [8]. Consequently, water evaporates from the cement paste, adversely affecting its rheological performance, its penetration behavior into the particle bed, and finally the cement hydration reaction. In addition, the aforementioned comparatively high build rates of the WAAM process are still lower than the SPI capabilities. Therefore, investigations are necessary to determine whether a combination of SPI and WAAM is reasonable [

8,

10].

This paper aims at demonstrating different approaches to reduce the heat propagation into previously printed layers. The authors consider a) increasing the distance between the printing nozzles and the particle bed, b) the active cooling of WAAM, and c) the passive cooling by functionally coated particles. The effect of the particles on the mechanical properties of concrete was tested. Hence, the compressive and flexural strengths of specimens consisting of standard and functionalized aggregates were compared.

2. CURRENT STATE of RESEARCH

The concept of reinforcement integration into SPI using WAAM was first introduced by Weger et al. [8] and is part of the collaborative research center TRR 277. Weger et al. presented preliminary investigations with a special focus on the temperature increase and the cooling rates during the process of WAAM. In addition, the robustness of the rheological properties of cement pastes to elevated temperatures was analyzed by random sampling. More in-depth studies regarding the temperature effect on the paste rheology and the reinforced concrete were performed to verify the pre-test data. These data create the foundation for further research (e.g., bond strength tests with temperature loads) [10].

A key factor in combining SPI and WAAM is minimizing the heat propagation into the freshly printed concrete. The heat is generated by the WAAM process and affects the properties of SPI components. In [

8,

10], it was stated that the rheological behavior of the cement paste and, thus, its penetration depth into the particle bed decreases significantly at cement paste temperatures above 60 °C. A complete penetration of the cement paste into the particle bed is no longer ensured at higher temperatures.

WAAM

Recently, the production of bar structures with WAAM has attracted more interest. Bar structures are manufactured with two different strategies today [11]. These are the continuous and the discrete technique. The discrete strategy can be used to manufacture diameters from 3 to 10 mm. The continuous strategy can be utilized to produce bars with bigger diameters [11]. Most of the applications use a discrete strategy. Concrete reinforcements were printed with a discrete strategy [12]. Also, for the application as reinforcements, discrete manufactured bars were analyzed regarding the effect of welding parameters on the surface topology by Müller et al. [13].

Dörrie et al. [14] produced a reinforcement structure with WAAM technology and encased it with concrete by shotcrete 3D printing. Thereby, they proved the feasibility of WAAM to reinforce additively manufactured concrete. They concluded that further improvements in the WAAM process are required to achieve higher material deposition and cooling rates. However, WAAM offers the possibility to manufacture topology-optimized structures and rebars with high bonding strengths compared to conventional rebars.

Weger et al. [8] manufactured bars with a diameter of 12 mm by using continuous circular welding trajectories. They produced three cycles each with two layers on top of a bar to measure the temperature development in a rebar manufactured with WAAM. By doing so, Weger et al. [8] determined the necessary distance between the welding zone and the particle bed in the SPI process. The process was stopped between the cycles until the rebar had cooled down to room temperature (23 °C). However, this was not representative as heat accumulation occurs during the WAAM process with a rising number of layers.

In addition to the distance between the welding zone and the particle bed, further possibilities to influence the amount of heat transferred into the concrete can be identified. For the WAAM process mainly three strategies are feasible: a) Gas-shielded arc welding processes with a low energy input, such as the Cold Metal Transfer (CMT) process, can be used, b) the distance between the WAAM process zone and the particle bed can be increased, and c) the reinforcements manufactured with WAAM can be actively cooled.

CMT has the advantages of a reduced required welding current and the absence of spattering while welding. The lower current results in a decreased energy and consequently a lower heat input than other welding techniques [15]. Different CMT process variants exist, such as the CMT cycle step mode. With this mode, the exact number of metal deposition cycles can be controlled for each welding phase. In addition, interval breaks up to 2 s can be defined between the welding phases. By controlling the number of deposition cycles, the geometry of the weld beads can be adapted and reproduced precisely. Müller et al. [13] used WAAM to produce bars with constant interlayer temperatures of 200 °C. They compared the CMT standard with the CMT cycle step mode. Bars manufactured with the CMT cycle step mode showed a more even strain distribution than bars produced with the CMT standard mode during longitudinal strain measurements. This indicates that the CMT cycle step mode is suitable for manufacturing bar structures (e.g., reinforcing bars).

The distance between the process zone and the particle bed is also the distance by which the rebars protrude over the particle bed and is therefore referred to as the protrusion distance. The protrusion distance affects the heat that is transferred into the concrete. A larger distance leads to a larger surface area of the bar being in contact with the atmosphere and, thus, cooled down by convection. Active cooling is coupled to the free reinforcement length over the surface area, which can be in contact with the coolant. Different approaches exist for active cooling. Reisgen et al. [16] compared sprayed water with compressed air cooling at a wall geometry, and Cunningham et al. [17] utilized liquid nitrogen to cool down a wall geometry. The cooling of parts manufactured by WAAM affects their mechanical properties. For this reason, active cooling can lead to increased yield and tensile strength [9].

Particle Coating with Dry Water

Studies have been carried out in the area of particle functionalization and particle coating. The main goal of particle functionalization in the context described here is to incorporate water into the aggregate particle bed, thereby compensating for water loss in the cement paste caused by elevated temperatures originating from WAAM. In addition, evaporation of supplementary water within the aggregate bulk material has a passive cooling effect and promotes cement hydration. Previous studies showed that the thermal conductivity of granular materials increases with their degree of saturation. Therefore, dry sand has a lower thermal conductivity than a mixture of sand and water, meaning it has a lower cooling capacity [

18,

19].

However, exclusively adding water to a bulk material severely affects the flow properties, which presumably do not cohere with the requirements for SPI. Generally, aggregates applied in SPI are free-flowing, cohesionless particles, which contribute to an even layer distribution and homogeneous porous networks. Water in the aggregate bulk material fundamentally results in liquid capillary bridges between single particles, reducing the initial bulk flowability and thereby increasing cohesion [20].

One possible solution arose with so called dry water, a form of encapsulated water, as an additive or coating material. Dry water is a dry dispersion that consists of water droplets with an outer shell composed of hydrophobic silica nanoparticles. The hydrophobic fumed silica adheres due to van der Waals interactions and prevents coalescence. Therefore, it appears as a powdery substance but can contain up to 98 wt.% of water [21]. Furthermore, the driving factors for an effective water encapsulation during the production process are the specific energy input, sufficient shear force, and the interfacial energy between the solid particles and the liquid material [22]. Several patents report dry water as a suitable rapid cooling method for fire extinguishment or a retardant for certain reactions due to the release of the adsorbed water [23 – 25]. By mixing dry water with aggregate particles, large amounts of water can be stored in the particle bed whilst maintaining its initial flow properties [26]. Consequently, suitable bulk properties can be ensured for a water-storing bulk material applied in SPI.

3. MATERIALS AND METHODS

3.1. Approach

Various cooling concepts are conceivable to ensure that the maximum temperatures encountered in the particle bed are within acceptable levels for SPI-manufactured concrete. The first step in this process is to determine the actual temperatures and their distribution present in the reinforcements produced by WAAM. These data are necessary to develop suitable active cooling systems. A second concept for cooling the combined SPI and WAAM process is to utilize passive cooling by coating the aggregates with dry water which are used for the particle bed. To evaluate the potential of using dry water in SPI printing, the absorbed heat of dry water was measured, and specimens were printed with a particle bed containing dry water. These specimens were tested for their compressive strength to unveil the effect of dry water on the mechanical properties of SPI-printed concrete.

3.2. Active Cooling of the WAAM Process

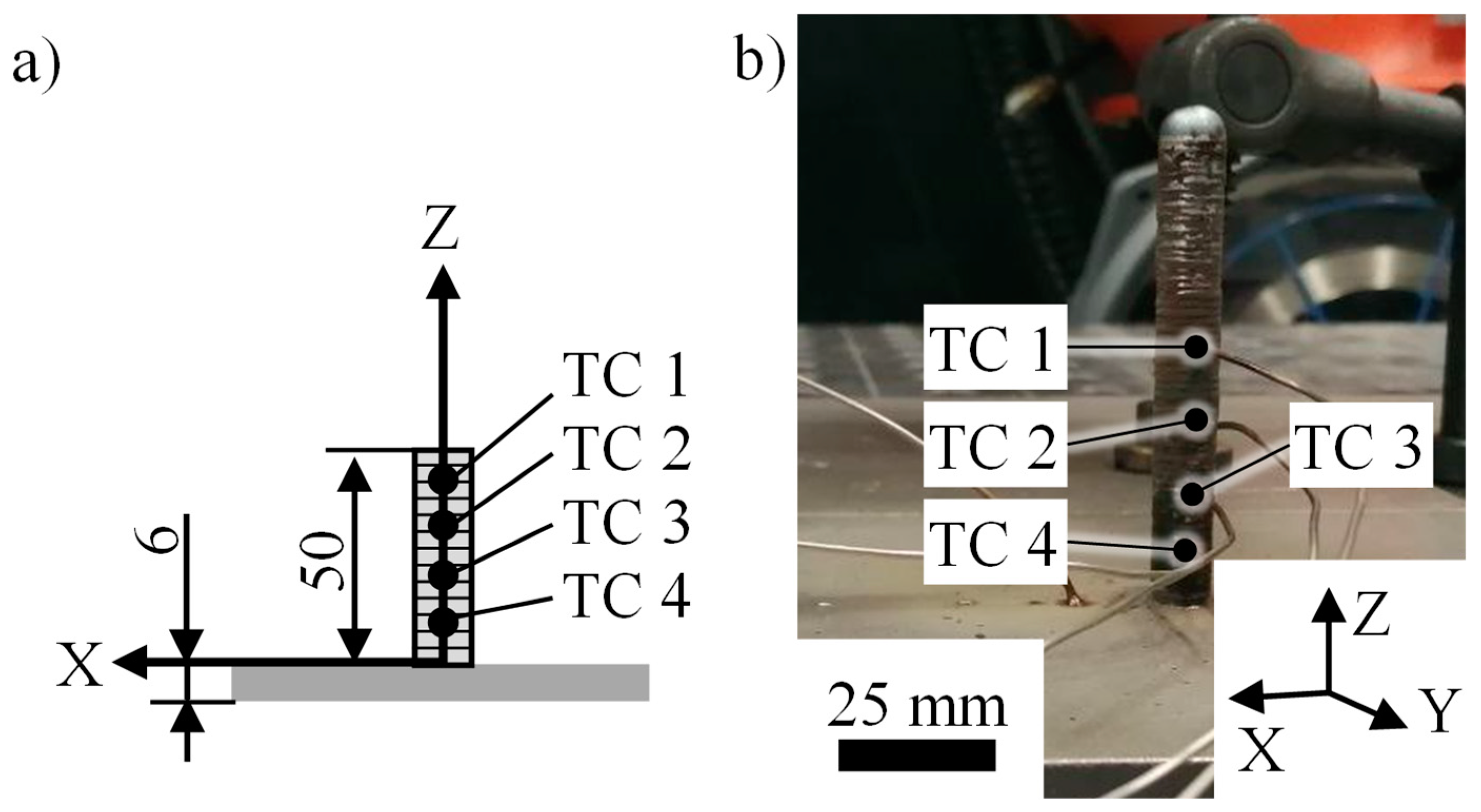

The temperature was measured during the deposition of 20 layers with a mean layer height of 1.25 mm on top of a 50 mm high prefabricated bar to gain better insight into the temperature development and its distribution. The setup is shown in

Figure 2. For the acquisition of thermal data within the experiment, a data logger cDAQ-9178 (National Instruments, USA) was deployed in combination with thermocouples of type N. The thermocouples (TC) are capable of operating at temperatures ranging from 0 °C to 1150 °C.

The TC were placed in drill holes. These were located at a height of 10 mm, 20 mm, 30 mm, and 40 mm.

In the experiment, a bar with a diameter of 8 mm was produced with a wire feed rate of 6 m/min and an interlayer cooling time of 60 s. A discrete welding strategy with 100 welding cycles per deposited layer was realized with the CMT cycle step mode developed by Fronius. A welding power source of the type Fronius TPS400i (Fronius, Austria) was utilized. The welding torch was mounted to an industrial robot of the type Motoman MH24 (Yaskawa, Japan). A 6 mm thick plate of S235JR was used as substrate material. The prefabricated bar and the additional layers were produced with a solid wire electrode made of G4Si1 according to DIN EN ISO 14341 [27].

3.3. Passive Cooling by Coated Particles

Dry water was processed in the high-shear blender MX 1250 (Rommelsbacher, Germany) equipped with a blade rotor and six blades. Mixing was conducted at a rotational speed of 22,000 rpm for one minute. Aerosil R812S (Evonik, Germany), with a specific surface area of 220 m2/g and a primary particle size of 7 nm, was used as hydrophobic fumed silica for encapsulation. Produced variants were differentiated by their mass fraction of water at wH2O: 80%, 87%, 90%, and 95%. The mass fractions were chosen in accordance with [26].

The thermogravimetric analyzer TGA/DSC 1 (Mettler-Toledo, Germany) was applied to characterize the potential cooling properties of dry water alone. The device measures both the deviations in mass as well as the differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) heat flow for the simultaneous detection of thermal events. Furthermore, samples were heated from 30 °C to 250 °C at 10 °C/min.

3.4. SPI Composition and Strength Testing

Five test specimens with dimensions of 60 mm x 60 mm x 200 mm (width x depth x height) were produced using the SPI process. The used SPI concrete consisted of quartz sand (1.0 – 2.2 mm) as aggregates in the particle bed and ordinary Portland cement with a water-cement ratio of 0.35 for the paste. The proportions of the cement paste and the aggregates were 42% and 58%, respectively. The flowability of the paste was adjusted by adding a superplasticizer to achieve a mini-slump flow of 400 mm to 410 mm, which ensures sufficient paste penetration at a reference paste temperature of 20 °C. The test specimens were removed from the printer one day after the production and were afterwards stored in a climate chamber at 20 °C and 65% rH until post-processing. One week before testing, the samples were cut and ground to conform to the dimensions of 40 mm x 40 mm x 160 mm (width x depth x height) as per DIN EN 196-1 [28]. This step is necessary as the surface of the SPI test specimens is uneven and the parallelism required by DIN EN 196-1 can only be achieved through an appropriate post-processing. After post-processing, the specimens were stored in the climate chamber until they were tested. Compressive and flexural strength tests were carried out according to DIN EN 196-1 after 28 days. This procedure (production, post-processing, and testing) was repeated to investigate the effect of particle functionalization on the strength properties. Therefore, the aggregates that were used to produce the test specimens were functionalized with dry water beforehand. The quartz sand was mixed with the additive in a conventional concrete drum mixer for 10 minutes. In this way, the additive was homogeneously distributed and adhered evenly to the particle surface. The functionalized aggregates were placed into the SPI printer so that the test specimens (15 specimens) could be produced, post-processed, and tested according to the previously described procedure. After testing, the results were compared and discussed to determine and evaluate the effects of the particle functionalization on the strength properties.

4. RESULTS And DISCUSSION

4.1. Active Cooling of the WAAM Process

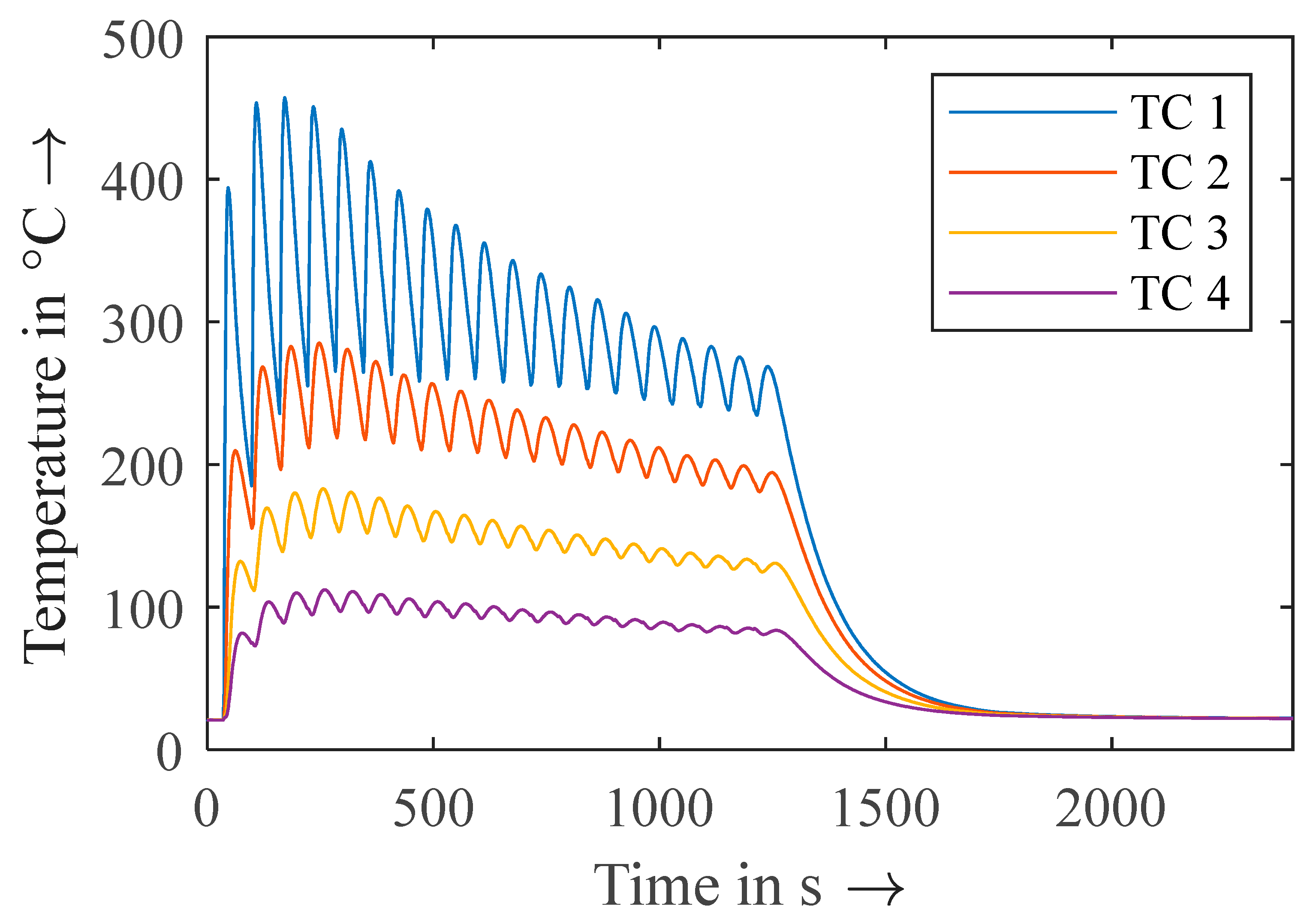

The WAAM experiment aimed to determine the required protrusion distance for WAAM-produced bars. This means the smallest possible protrusion distance while not exceeding the maximum permissible temperature. Therefore, the maximum occurring temperatures depending on the protrusion distance were determined from the measured data shown in

Figure 3. The local maxima of the measured thermal data were identified. Each of these maxima results from the heat input due to manufacturing an additional layer. With the knowledge about the layer height, the time-dependent temperature maxima can be assigned to distances between the measurement point and the process zone.

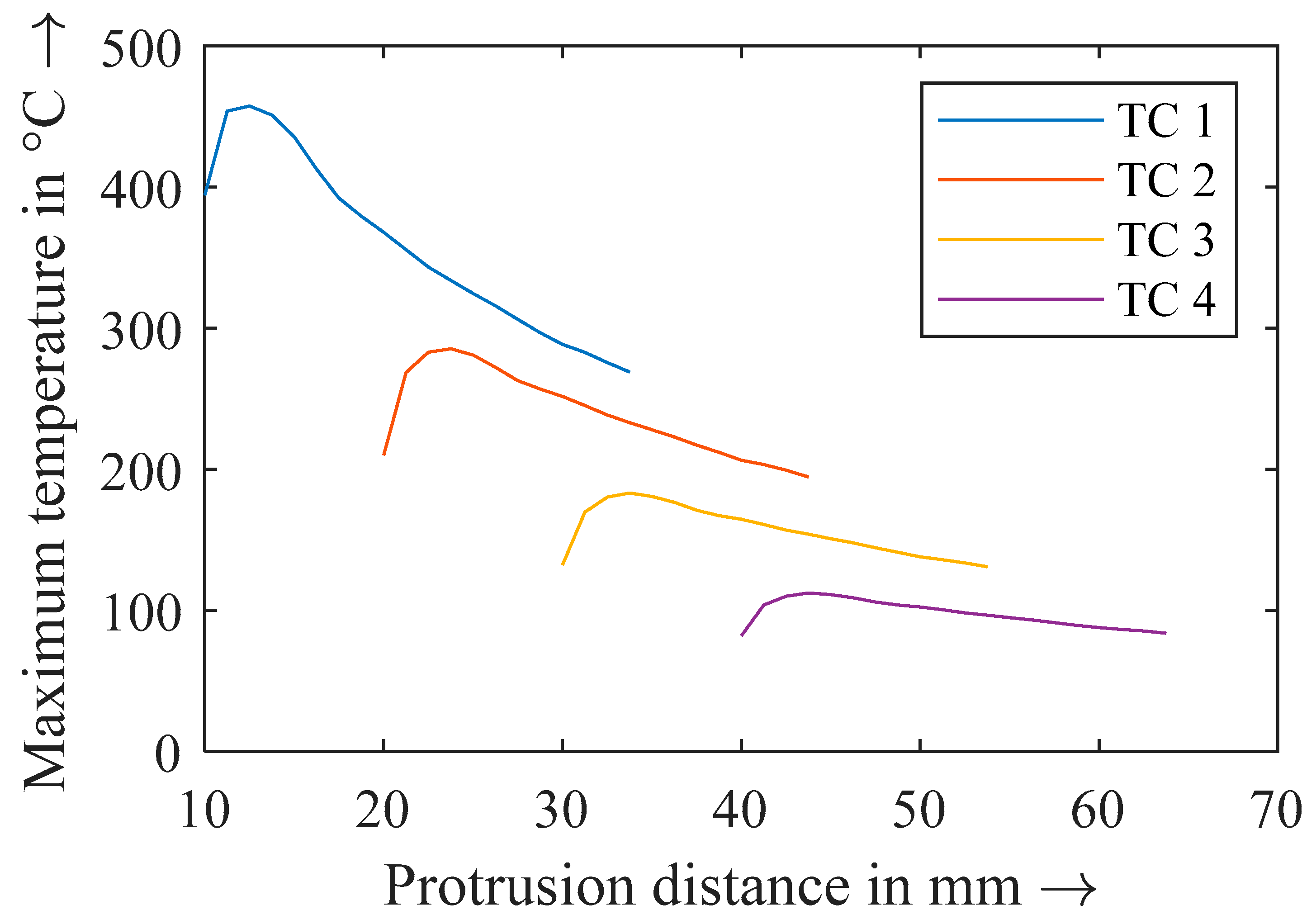

With this transformation from time to distance, temperature curves depending on the protrusion distance were derived, as depicted in

Figure 4. According to the thermal data at a distance of 40 mm, a temperature of 206 °C at TC 2 and 164 °C at TC 3 was reached. The deposition height affected the heat dissipation (i.e., the temperature development), as reported by [29]. As a result, in this use case, points closer to the substrate plate cooled down faster, as the thermal resistance is lower for them than for points with a higher distance to the substrate plate. A stable temperature state will be reached for geometries with a constant cross-section over the height.

The measured maximum temperatures of 206 °C and 164 °C were higher than the cement paste temperature limit of 60 °C determined by [

8,

10].

Nevertheless, it remains to be investigated whether the threshold temperature at which the rheological properties of the cement paste change can be assumed to be a boundary temperature for the whole SPI system. It is conceivable that temperatures below 60 °C in the particle bed already negatively affect the bond between concrete and steel, consequently decreasing the concrete strength. This would mean that the maximum temperature in the particle bed needs to be already lower than the limit of 60 °C imposed because of the rheological properties.

It is also conceivable that the strengths are only negatively affected at temperatures well above 60 °C. It needs thus to be investigated whether the change in the rheology of the cement paste is useful as a criterion for the maximum process temperature. The penetration depth can no longer be guaranteed at a cement paste temperature above 60 °C. However, it is still possible that the cement paste does not reach this temperature during penetration (the paste is applied to the particle bed with an initial temperature of about 20 °C). Temperatures higher than 60 °C are presumptively only achievable if the surrounding particle bed has significantly higher temperatures since the penetration period of the cement paste into the particle bed is relatively short. Accordingly, the cement paste may fully penetrate the aggregate layer before the additively manufactured rebar induces temperatures above 60 °C.

In addition, increasing the distance between the particle bed and the nozzle and thus the protrusion distance would facilitate both passive and active cooling strategies. An increased distance would allow the steel to protrude further over the particle bed, thereby increasing its ability to dissipate heat through its length (passive cooling). Furthermore, the increased exposed surface area of the steel bar would allow for stronger active cooling (e.g., using water fog or compressed air). Conversely, it is expected that the print quality will decrease as the distance increases (since an increasing distance may complicate the uniform application of the cement paste). Therefore, a suitable distance between the printing nozzle and the particle bed needs to be determined to maximize the protrusion distance.

4.2. Passive Cooling by Particle Coated Water Droplets

To consider dry water as an effective additive for cooling the particle bed by particle coating, the cooling potential of created formulations needs to be examined first.

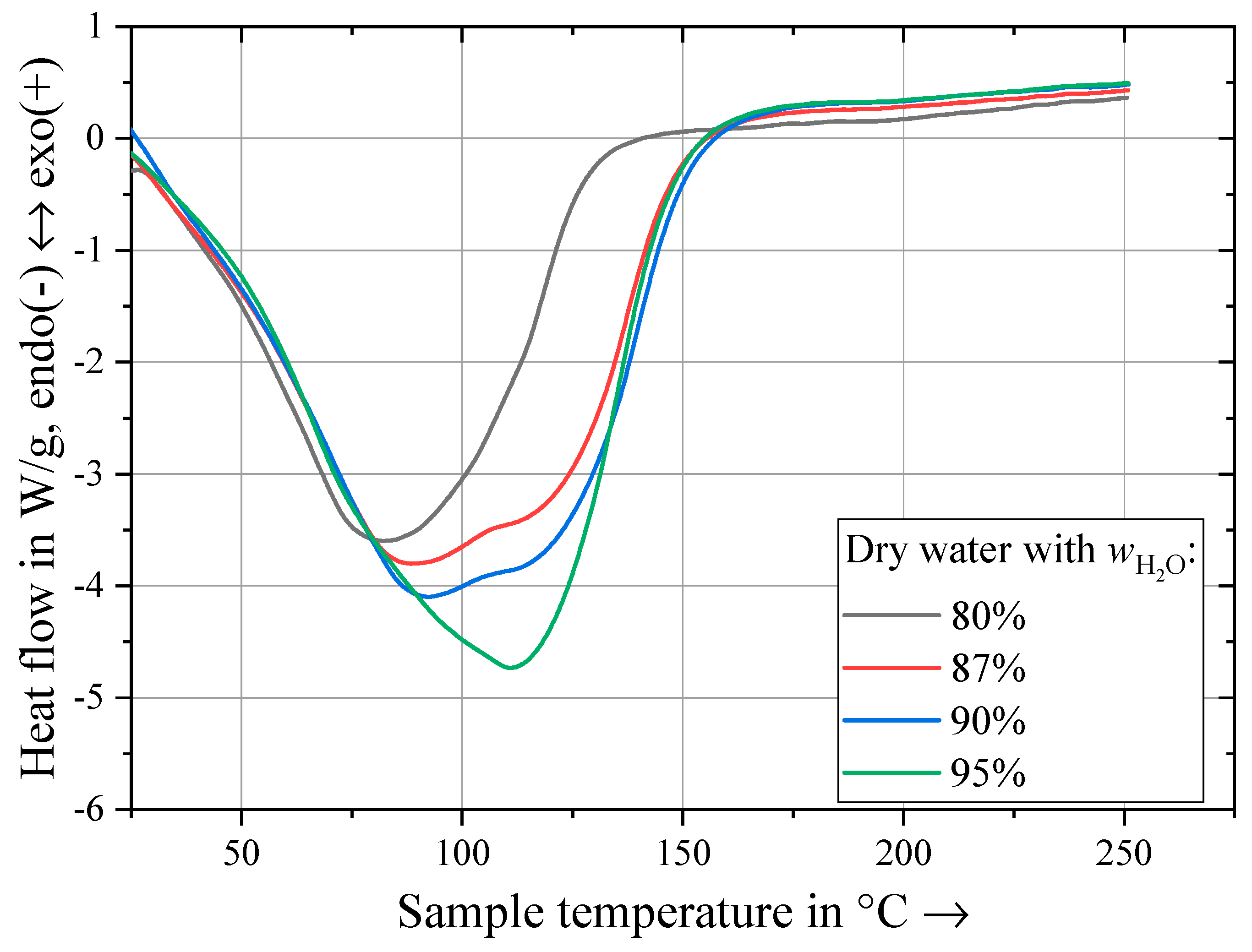

Figure 5 demonstrates the DSC curves of the created dry water variants denoted by the mass fraction of water

wH2O (80%, 87%, 90%, and 95%).

Positive values denote an exothermic material behavior, whereas negative heat flows indicate an endothermic behavior. The negative values in the results show that endothermic events occur during the thermal analysis, meaning dry water has cooling properties mainly due to water evaporation. The maximum endothermic heat flow increases for the dry water variants with higher fractions of water. Interestingly, the peaks shift towards higher temperatures for the dry water variants with higher proportions of water. This may be caused by the increased thermal inertia of the samples containing higher masses of water. However, the heat flow curves do predominantly align before the maximum endothermic value is reached. Another explanation for the shift in peaks can presumptively be derived from the available specific surface area due to the dry water capsule size. The dry water variant with the lowest water content (wH2O = 80%) and, thereby, the highest fumed silica content generally had the lowest particle size and the lowest bulk density. As a result, the encapsulated water has a higher surface area available for imminent heat exchange.

Higher specific areas and increased porous volumes in the bulk material result in maximum endothermic heat flows at lower temperatures. However, cooling effects are higher with lower proportions of hydrophobic fumed silica within created formulations as the maximum heat flow increases. Although higher mass fractions of water lead to better cooling, special attention needs to be paid to the effect of the silica content within dry water variants. Dry water with insufficient quantities of hydrophobic fumed silica creates aggregate mixtures with inadequate bulk properties for SPI (i.e, diminished bulk flow properties and irregular aggregate particle bed structure). Additional information about dry water and its properties is available in [26].

4.3. Strength Validation of Passive Cooling with Dry Water

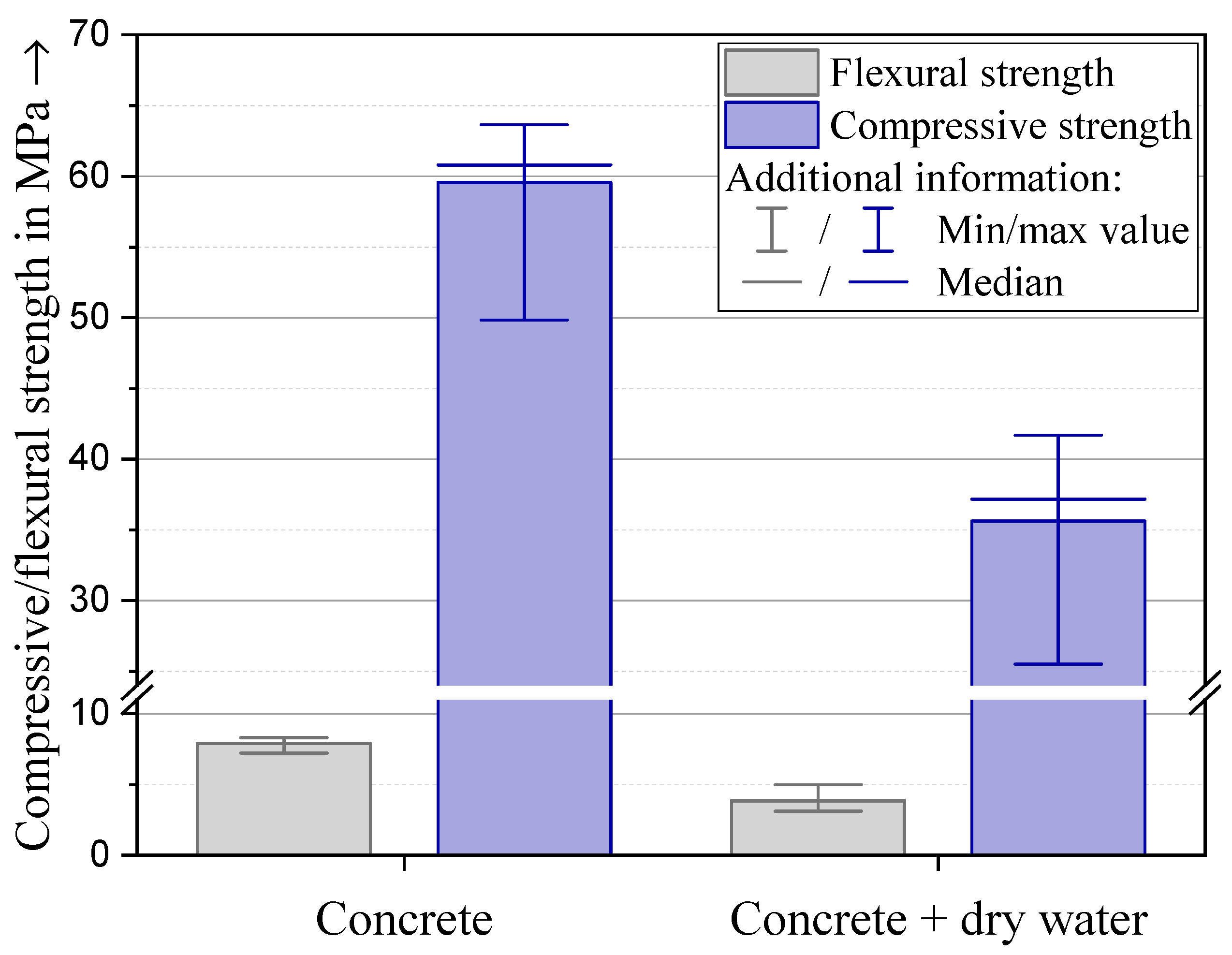

Figure 6 shows that an average compressive strength (five specimens) of 60 MPa was achieved for the SPI concrete without functionalized particles as reference. However, the SPI concrete containing functionalized particles resulted in an average compressive strength (15 specimens) of only 36 MPa. The flexural strength was also found to be lower for the samples with functionalized aggregates (3.9 MPa) compared to the reference (7.9 MPa).

It can be observed that especially for the compressive strength values, high deviations for the individual specimens occur, see

Figure 6. A possible reason for this variability in the results are presumptively unavoidable inaccuracies in the post-processing of the specimens. Non-parallel surfaces of the specimens can lead to stress concentrations and thus failure at lower loads. The examination of the specimens after testing showed that the specimens with the highest deviation in parallelism failed at lower loads as expected. The lower deviations in the flexural strength measurements could be explained by the used test equipment, which compensated for slight misalignments or uneven surfaces with a self-adjusting fixture and load application.

However, regarding the strength values, the functionalized aggregates may have altered the properties of the interfacial transition zone (ITZ), which decrease the compressive and flexural strength of the concrete. The hydrophobic nature of the fumed silica presumptively prevents the cement paste from fully penetrating and evenly distributing in each layer.

The effect of the hydrophobicity on the wettability of functionalized aggregates was already visible during the SPI process (see

Figure 7). The printed particle bed surface showed that the cement paste fully penetrated and surfaces were fully wetted without functionalized particles (see

Figure 7 a)). This resulted in a saturated, uniformly dark grey colored print. In contrast, the printed particle bed surface with functionalized particles appeared in lighter grey color with visible inhomogeneities (see

Figure 7 b)). The cement paste tended to lie on the surface instead of penetrating due to the reduced wettability of the aggregates.

Overall, the functionalized particles may have negatively affected the ITZ and the bond strength between the aggregates and the cement paste, leading to a significant decrease in the mechanical properties of the concrete. A mixture of aggregate quartz and dry water in its current form is thereby inadequate for current materials and processes in SPI. Hence, suitable material-based solutions must be additionally customized in accordance with SPI requirements (e.g., hydrophilization of the dry water for avoiding wettability problems).

5. SUMMARY And OUTLOOK

Within this study, concepts were addressed to facilitate a novel hybrid AM process for structural concrete. The hybrid process consists of SPI and WAAM. As the main obstacle in combining both techniques, the heat propagation from the WAAM welding process into the concrete materials was identified. Hence, three methods were considered to counteract the enhanced heat conduction into the particle bed and to increase the compatibility between the two processes. These methods were: Increasing the distance between the printing nozzles and the particle bed, actively cooling the WAAM rebar, and passive cooling by coated aggregate particles. An analysis of the distance-dependent temperatures was achieved with a self-constructed setup of a prefabricated bar and surrounding thermocouples. A further investigation of the passive cooling properties of dry water as an additive for coated aggregate particles was performed by means of thermogravimetric analyses. As a last step, concrete components consisting of standard aggregates and aggregates coated with dry water were printed with SPI. Their flexural and compressive strengths were subsequently compared.

In summary, the following conclusions could be drawn:

The maximum measured temperatures at a distance of 40 mm to the welding zone were ranging from 164 °C to 206 °C. Thus, active cooling is indispensable.

Dry water has adequate cooling properties and can be deployed to create a free-flowing, water-storing bulk material.

The amount of fumed silica in the dry water affects the maximum heat flow in terms of its extent and temperature of occurrence.

Compressive strength values of up to 60 MPa and 36 MPa were achieved without functionalized particles and with dry-water-coated particles, respectively.

The flexural strength was found to be lower for samples with dry-water-coated aggregates, with an average of 3.9 MPa compared to 7.9 MPa for samples without functionalization.

The functionalized particles may negatively affect the ITZ and the bond strength between the aggregate and the cement paste and, thus, may lead to decreased overall concrete strength.

Further research is needed to understand the specific mechanisms in detail, how functionalized particles affect the ITZ and the bond strength. Surfactants can also be implemented to counteract the effects of hydrophobicity and ensure sufficient wettability of the functionalized aggregates. In doing so, the cement paste could wet the functionalized aggregate particles in a uniform manner (i.e., increase the applicability in SPI). This has to be proven by tests on concrete samples produced with SPI, which have to be analyzed with regard to their mechanical properties. Furthermore, the results of the printed samples should be compared with samples that were conventionally cast.

To initially limit sources of error, such as an inadequate post-processing, further investigations need to be conducted using cast prisms in accordance with DIN EN 196-1. This series of tests aims to examine the results presented in this work. An extension of this test series on cast prisms would involve investigating the impact of temperature loads on the fresh concrete and theireffect on the hardened concrete properties, such as compressive and flexural strength, both with and without functionalized particles.

Within WAAM, it needs to be investigated whether the temperatures can be limited to the maximum tolerable process temperature for SPI with the help of an active cooling system. The material properties of the reinforcements or their modification by the cooling system should also be investigated since increased cooling can embrittle the steel.

Further research is required to determine the suitable distance between the printing nozzle and the particle bed to maximize the protrusion distance. A trade-off between increased cooling effects and the SPI print quality is to be made.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S., F.R., L.H.; methodology, A.S., F.R., L.H.; validation, A.S., F.R., L.H.; formal analysis, A.S., F.R., L.H.; investigation, A.S., F.R., L.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S., F.R., L.H.; writing—review and editing, T.K., C.G., M.F.Z., A.K.; visualization – figures A.S., F.R., L.H.; supervision, T.K., C.G., M.F.Z., A.K.; project administration, C.G., M.F.Z., A.K.; funding acquisition, C.G., M.F.Z., A.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research project was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – project number 414265976 – TRR 277.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Philip Schneider, Chair of Materials Science and Testing, Technical University of Munich, for the support with the renderings of Fig. 1.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- R.A. Buswell, W.L. da Silva, F.P. Bos, H.R. Schipper, D. Lowke, N. Hack, H. Kloft, V. Mechtcherine, T. Wangler, N. Roussel, A process classification framework for defining and describing Digital Fabrication with Concrete, Cement and Concrete Research 134 (2020). [CrossRef]

- A. Pierre, D. Weger, A. Perrot, D. Lowke, Penetration of cement pastes into sand packings during 3D printing: analytical and experimental study, Mater Struct 51 (2018) 1221. [CrossRef]

- D. Lowke, E. Dini, A. Perrot, D. Weger, C. Gehlen, B. Dillenburger, Particle-bed 3D printing in concrete construction – Possibilities and challenges, Cement and Concrete Research 112 (2018) 50–65. [CrossRef]

- D. Weger, Additive Fertigung von Betonstrukturen mit der Selective Paste Intrusion - SPI. Additive manufacturing of concrete structures by Selective Paste Intrusion - SPI, Universitätsbibliothek der TU München, 2020.

- D. Weger, C. Gehlen, Particle-Bed Binding by Selective Paste Intrusion-Strength and Durability of Printed Fine-Grain Concrete Members, Materials (Basel, Switzerland) 14 (2021). [CrossRef]

- D. Weger, A. Pierre, A. Perrot, T. Kränkel, D. Lowke, C. Gehlen, Penetration of Cement Pastes into Particle-Beds: A Comparison of Penetration Models, Materials (Basel, Switzerland) 14 (2021). [CrossRef]

- A. Pierre, D. Weger, A. Perrot, D. Lowke, Additive Manufacturing of Cementitious Materials by Selective Paste Intrusion: Numerical Modeling of the Flow Using a 2D Axisymmetric Phase Field Method, Materials (Basel, Switzerland) 13 (2020). [CrossRef]

- D. Weger, D. Baier, A. Straßer, S. Prottung, T. Kränkel, A. Bachmann, C. Gehlen, M. Zäh, Reinforced Particle-Bed Printing by Combination of the Selective Paste Intrusion Method with Wire and Arc Additive Manufacturing – A First Feasibility Study, in: F.P. Bos, S.S. Lucas, R.J.M. Wolfs, T.A.M. Salet (Eds.), RILEM Bookseries, Second RILEM International Conference on Concrete and Digital Fabrication, Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2020, pp. 978–987.

- J. Müller, J. Hensel, K. Dilger, Mechanical properties of wire and arc additively manufactured high-strength steel structures, Weld World 66 (2022) 395–407. [CrossRef]

- A. Straßer, D. Weger, C. Matthäus, T. Kränkel, C. Gehlen, Combining Wire and Arc Additive Manufacturing and Selective Paste Intrusion for Additively Manufactured Structural Concrete, Open Conf Proc 1 (2022) 61–72. [CrossRef]

- F. Riegger, M.F. Zäh, Additive Fertigung von Stahlbewehrungen, Zeitschrift für wirtschaftlichen Fabrikbetrieb 117 (2022) 448–451. [CrossRef]

- V. Mechtcherine, J. Grafe, V.N. Nerella, E. Spaniol, M. Hertel, U. Füssel, 3D-printed steel reinforcement for digital concrete construction – Manufacture, mechanical properties and bond behaviour, Construction and Building Materials 179 (2018) 125–137. [CrossRef]

- J. Müller, M. Grabowski, C. Müller, J. Hensel, J. Unglaub, K. Thiele, H. Kloft, K. Dilger, Design and Parameter Identification of Wire and Arc Additively Manufactured (WAAM) Steel Bars for Use in Construction, Metals 9 (2019) 725. [CrossRef]

- R. Dörrie, V. Laghi, L. Arrè, G. Kienbaum, N. Babovic, N. Hack, H. Kloft, Combined Additive Manufacturing Techniques for Adaptive Coastline Protection Structures, Buildings 12 (2022) 1806. [CrossRef]

- G. Lorenzin, G. Rutili, The innovative use of low heat input in welding: experiences on ‘cladding’ and brazing using the CMT processPaper presented at the 4th National Welding Day, Workshop: “Brazing”, Genoa, 25–26 October 2007, Welding International 23 (2009) 622–632. [CrossRef]

- U. Reisgen, R. Sharma, S. Mann, L. Oster, Increasing the manufacturing efficiency of WAAM by advanced cooling strategies, Weld World 64 (2020) 1409–1416. [CrossRef]

- C.R. Cunningham, V. Dhokia, A. Shokrani, S.T. Newman, Effects of in-process LN2 cooling on the microstructure and mechanical properties of type 316L stainless steel produced by wire arc directed energy deposition, Materials Letters 282 (2021) 128707. [CrossRef]

- V.R. Tarnawski, T. Momose, W.H. Leong, Thermal Conductivity of Standard Sands II. Saturated Conditions, Int J Thermophys 32 (2011) 984–1005. [CrossRef]

- S.X. Chen, Thermal conductivity of sands, Heat Mass Transfer 44 (2008) 1241–1246. [CrossRef]

- A. Kudrolli, Granular matter: sticky sand, Nature materials 7 (2008) 174–175. [CrossRef]

- L. Forny, K. Saleh, I. Pezron, L. Komunjer, P. Guigon, Influence of mixing characteristics for water encapsulation by self-assembling hydrophobic silica nanoparticles, Powder Technology 189 (2009) 263–269. [CrossRef]

- L. Forny, I. Pezron, K. Saleh, P. Guigon, L. Komunjer, Storing water in powder form by self-assembling hydrophobic silica nanoparticles, Powder Technology 171 (2007) 15–24. [CrossRef]

- B.D. Allan, Dry water. US19750636328 C04B40/06;C09K5/06;C09K3/00, 1975.

- W.D. Stephens, C.L. Salter, G.K. Hodges, T.E. Hice, J.S. Prickett, Cool insulator. US19970885703 C09K5/00;H01B3/28;H01B3/28;C09K5/00, 1997.

- J.A. Senecal, Deflagration suppression agent and method for its use. US19930100395 A62D1/00;A62D1/00, 1994.

- L.D. Hamilton, H. Zetzener, A. Kwade, The Effect of Water, Nanoparticulate Silica and Dry Water on the Flow Properties of Cohesionless Sand, Processes 10 (2022) 2438. [CrossRef]

- DIN EN ISO 14341:2020-12, Schweißzusätze_- Drahtelektroden und Schweißgut zum Metall-Schutzgasschweißen von unlegierten Stählen und Feinkornstählen_- Einteilung (ISO_14341:2020); Deutsche Fassung EN_ISO_14341:2020, Beuth Verlag GmbH, Berlin. [CrossRef]

- DIN EN 196-1:2016-11, Prüfverfahren für Zement_- Teil_1: Bestimmung der Festigkeit; Deutsche Fassung EN_196-1:2016, Beuth Verlag GmbH, Berlin.

- X. Bai, P. Colegrove, J. Ding, X. Zhou, C. Diao, P. Bridgeman, J. roman Hönnige, H. Zhang, S. Williams, Numerical analysis of heat transfer and fluid flow in multilayer deposition of PAW-based wire and arc additive manufacturing, International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 124 (2018) 504–516. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).