Introduction

Perinatal asphyxia increases the risk for neonatal mortality and chronic neurological disability in survivors and involves 2 to 4 newborns every 1,000 full-term newborns. Of these, 15-20%, who present with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), die during the neonatal period (1). Although whole body therapeutic hypothermia (TH) has improved outcomes (2,3), up to 40% of neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) have serious neurological disability at 18–24 months of age, including cerebral palsy in nearly 1 of every 4 to 5 cooled neonates, seizures, visual defects, mental retardation, cognitive impairment and epilepsy (4–6).

Currently, the diagnosis of neonatal HIE depends on clinical symptoms and instrumental data, collected through computer tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), brain ultrasound and electroencephalogram (EEG) (5,6). None of these factors alone seems to allow for an early detection of HIE subsequent to perinatal asphyxia. Therefore, in the clinical practice, a combination of these parameters is used for the diagnosis and prognostication of such severe complication.

According to the most recent literature, cytokines/chemokines may act as a final common pathway for central nervous system (CNS) injury initiated by a variety of insults, asphyxia included. It has been reported that elevated plasmatic cytokine and chemokine levels in the first 24 hours of life are associated with worse MRI-detected brain injury in asphyxiated neonates (7,8). TH seems to influence positively the long-term neurological outcomes of neonates with HIE, by counteracting the increase of at least some inflammatory biomarkers (9,10), during the acute phase of the hypoxic-ischemic insult. If inflammatory molecules play a role in the genesis of HIE (7,10,11), their evaluation as biomarkers of brain damage in clinical practice could allow more timely diagnoses to be made than it is currently the case, and may implement early interventions to reduce neonatal mortality, morbidity and degree of disability. The early assessment of such biomarkers could be useful to use adjunct therapies associated with TH.

This preliminary case-control pilot study describes plasma profiles of some molecules involved in neuronal inflammation, secondary to perinatal asphyxia, in a group of 10 neonates treated with therapeutic hypothermia. The aim of the study was to explore possible relationships between such inflammatory biomarkers and the findings of brain MRI, performed between 7 and 10 days of life.

Matherials and Methods

Study approvals

At admission of the newborn to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), parents signed the informed consent for the TH protocol, treatment and use of patient’s data for non-profit and anonymous scientific researches. The study was notified and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital (Protocol number: 1381 OPBG 2017- N°1381, 2017).

Inclusion criteria

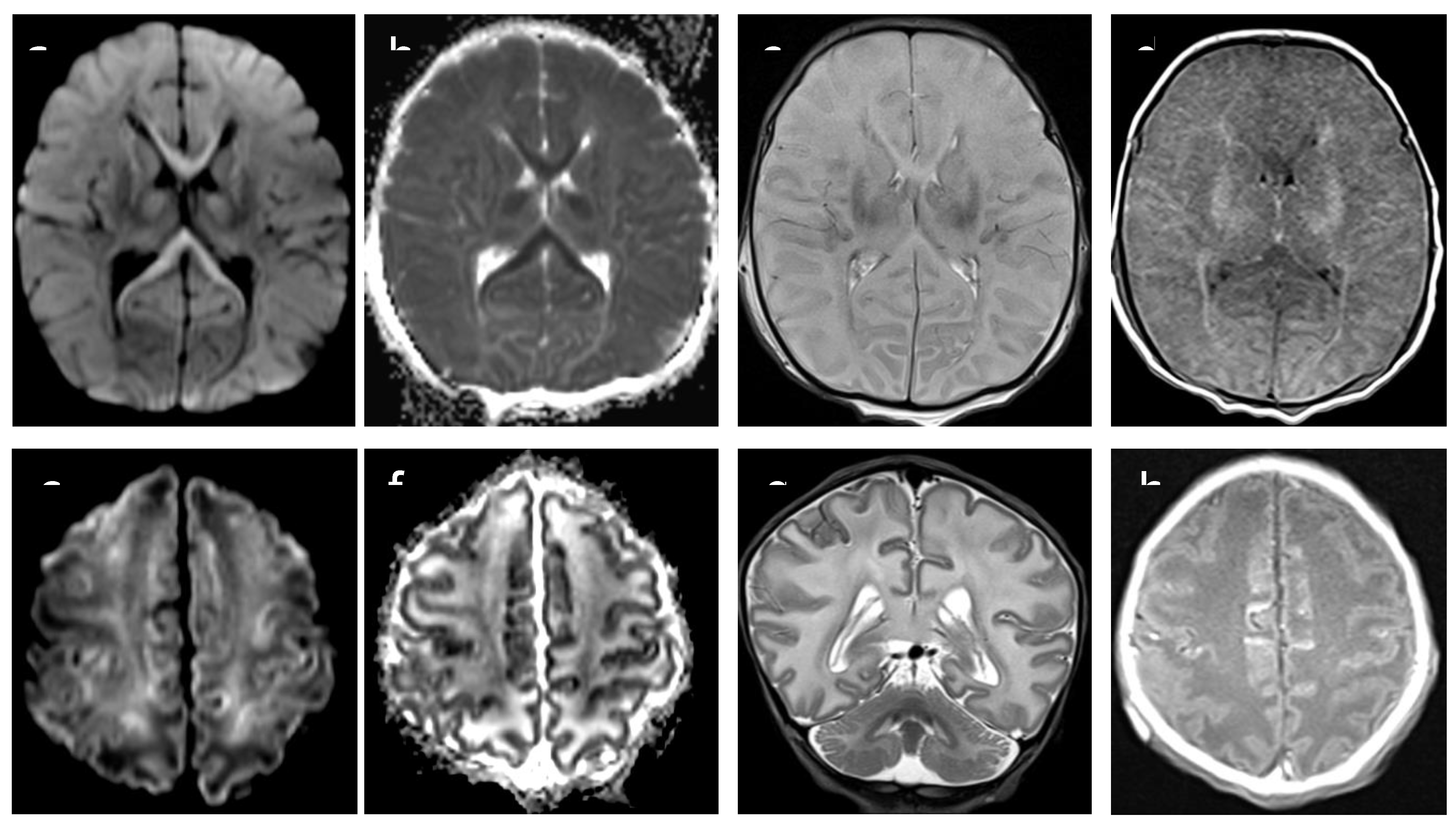

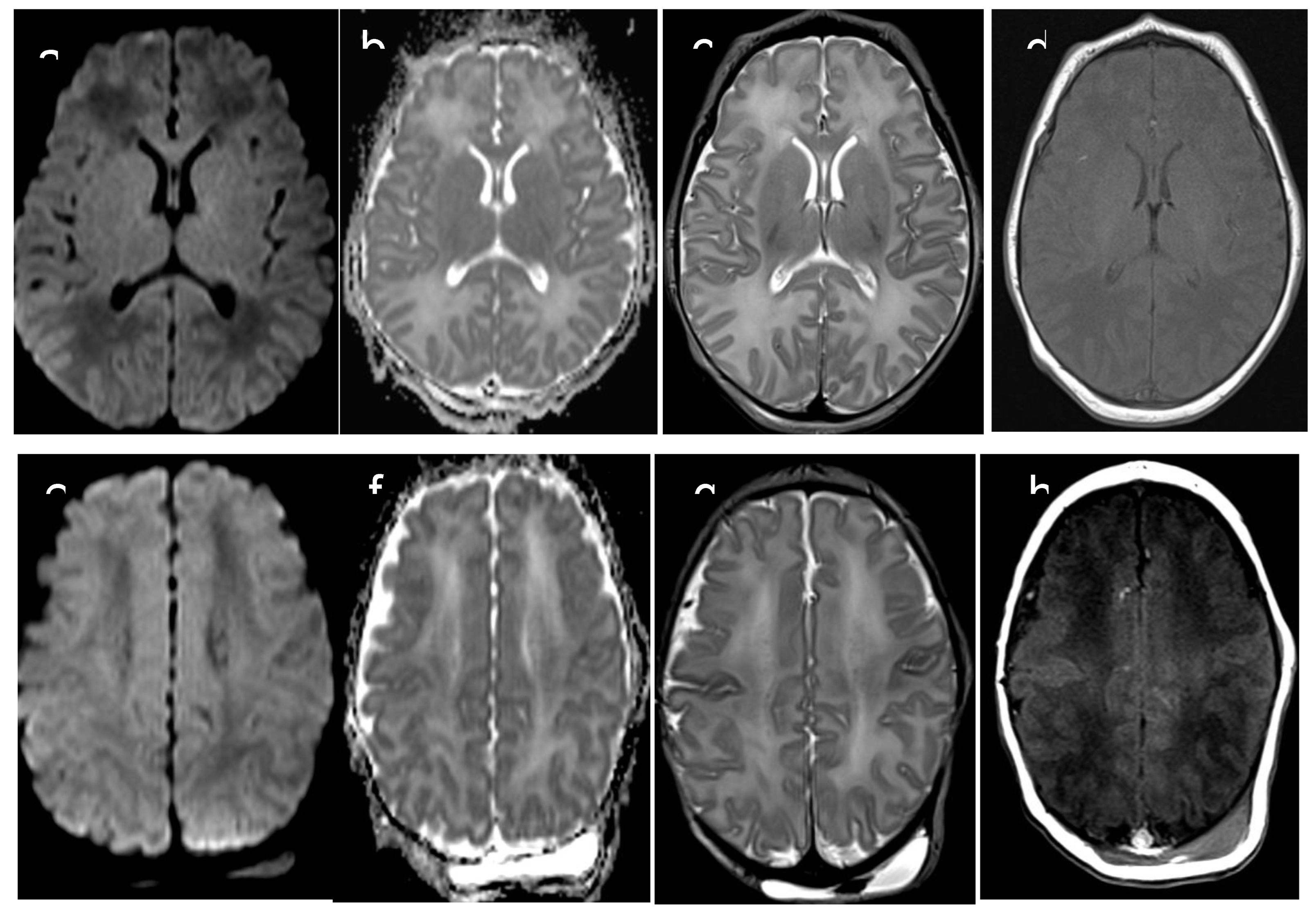

Based on brain MRI performed between 7 and 10 days of life, we selected 10 neonates who had been admitted to our NICU to undergo TH because of moderate to severe perinatal asphyxia. Five of those neonates had severe MRI examination, with abnormal signal in entire cortex and basal nuclei (“cases”) and five had completely normal MRI examination (“controls”) (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). During TH, infants were cooled to maintain a core temperature at 33.5°C (with accepted variation between 33°C and 34 °C) for 72 hours, followed by rewarming by 0.5°C/hour over 6 hours. Brain MRI was performed at 7-10 days of life, after the rewarming phase. MRI protocol (3-T Skyra, Siemens, Erlagen, Germany) included: axial T1 SE, sagittal T1 TIRM, axial and coronal T2 TSE and DWI with a single-shot echo-planar sequence. Additional sequences were axial T2 GRE and axial T2 FLAIR. Brain MRI pathological lesions were classified according to the Barkovich score (12).

Sample collection and cytokine/chemokines measurements

For each neonate treated with TH, we routinely collected blood samples for hematological examination and chemistry at four different time points during TH (24 hours, 25-48 hours, 49-72 hours), and after the rewarming (7-10 days from birth), according to the NICU protocol for the management of neonates undergoing TH. Residual plasma samples were immediately stored at -80°C, until processed. We assessed plasmatic cytokines/chemokines and other inflammatory molecules levels: monocytic chemotactic-protein-1 (CCL2/MCP-1), Interleukin 8 (CXCL8), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), Interferon gamma (IFN y), Interleukin 10 (IL-10), Interleukin 18 (IL-18), Interleukin 6 (IL-6), macrophage inflammatory protein 1-alpha (MIP-1-alpha or CCL3), ENOLASE2, Colony Stimulating Factor (GM-CSF), Interleukin 1-b (IL-1b), Interleukin 12p70 (IL-12p70), Interleukin 33 (IL-33), Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha (TNFα)], by magnetic luminex screening assay, using Human Premixed Multi-Analyte Kit (R&D Systems, Inc. Minneapolis, MN, USA). The assay was carried out according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistics

Data analysis was performed by Stata version 13 for Windows (Stata Corp. College Station, TX). Mean values and standard deviation were used to compare the general data of the two groups (compared by t-test student). Mean values and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) of the cytokines at different time-points were estimated using mixed linear regression models. In particular, these models included, as fixed covariates, time points and evaluation of brain damage. Data were clustered by patient and a random intercept was considered. The parameters were analyzed log-transforming the raw values because using the untransformed values the model at some time points estimated negative lower 95%CI. P ≤ 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Clinical characteristics of patients, stratified by MRI results, were similar, without statistically significant differences regarding gestational age, birth weight, APGAR score at 1 and 5 minutes, lower pH and EB in the first hour of life (

Table 1).

Cytokines and inflammatory molecules

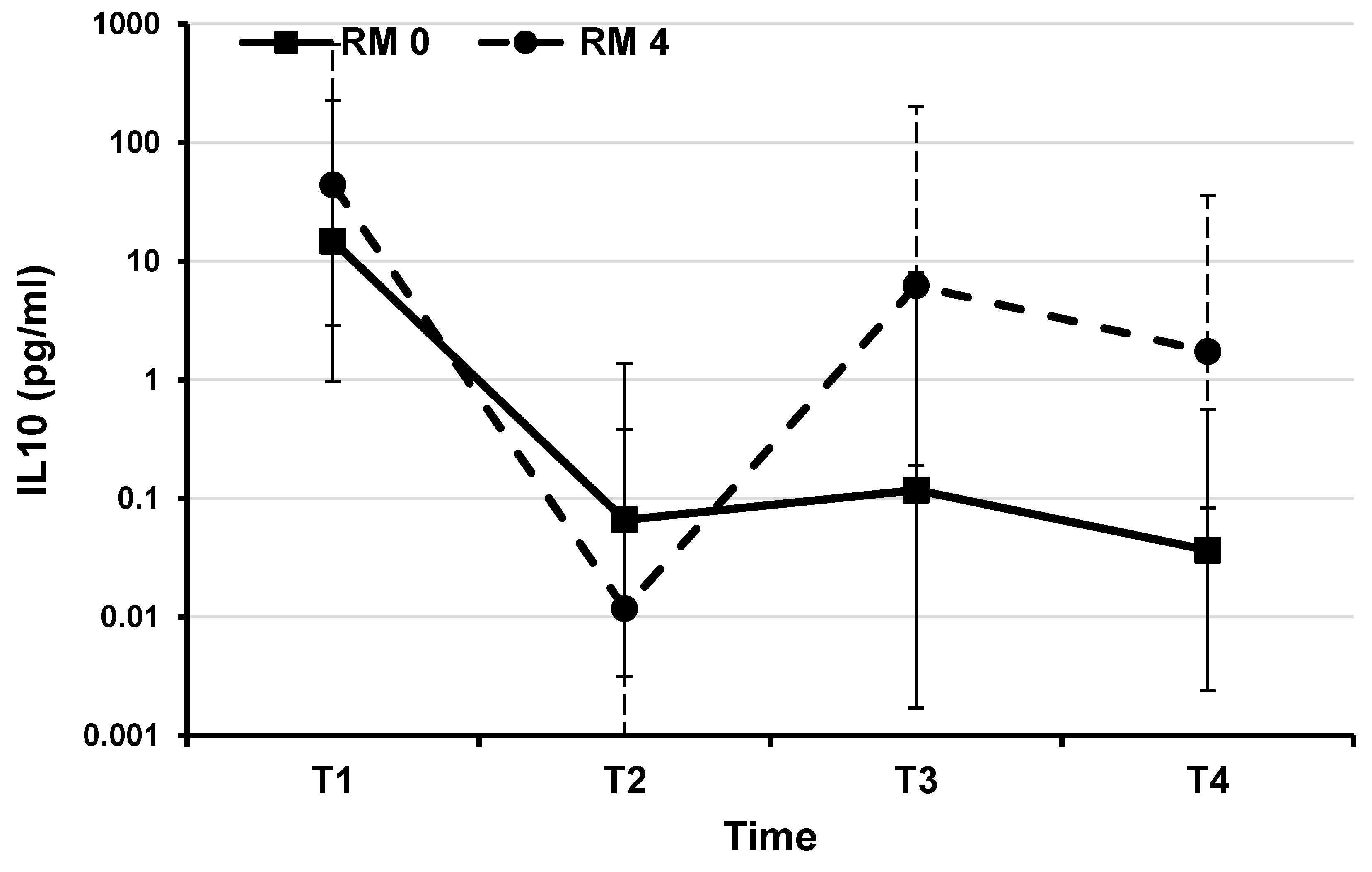

Mean levels of all molecules measured at the time point T1 were not significantly different in the two groups of patients (Supplemental Table S1). Comparing samples, paired between cases and controls by day of collection, we found the greatest differences during TH, at time points T2 and T3, while after the rewarming, at the time point T4, levels of cytokines (with the exception of IL-6, IL-10 and IL-18) tended to be close again. With the rewarming some molecules showed an upward trend in both the groups of patients (Graphics in the Supplemental Files S1–S9). Mean values of IL-6 and IL-10 were similar in the two groups of infants until the time point T2. Then the pathologic MRI 4 group showed an increasing trend, with a difference reaching almost the statistical significance for IL-10 (Supplemental File S7,

Table 2 and

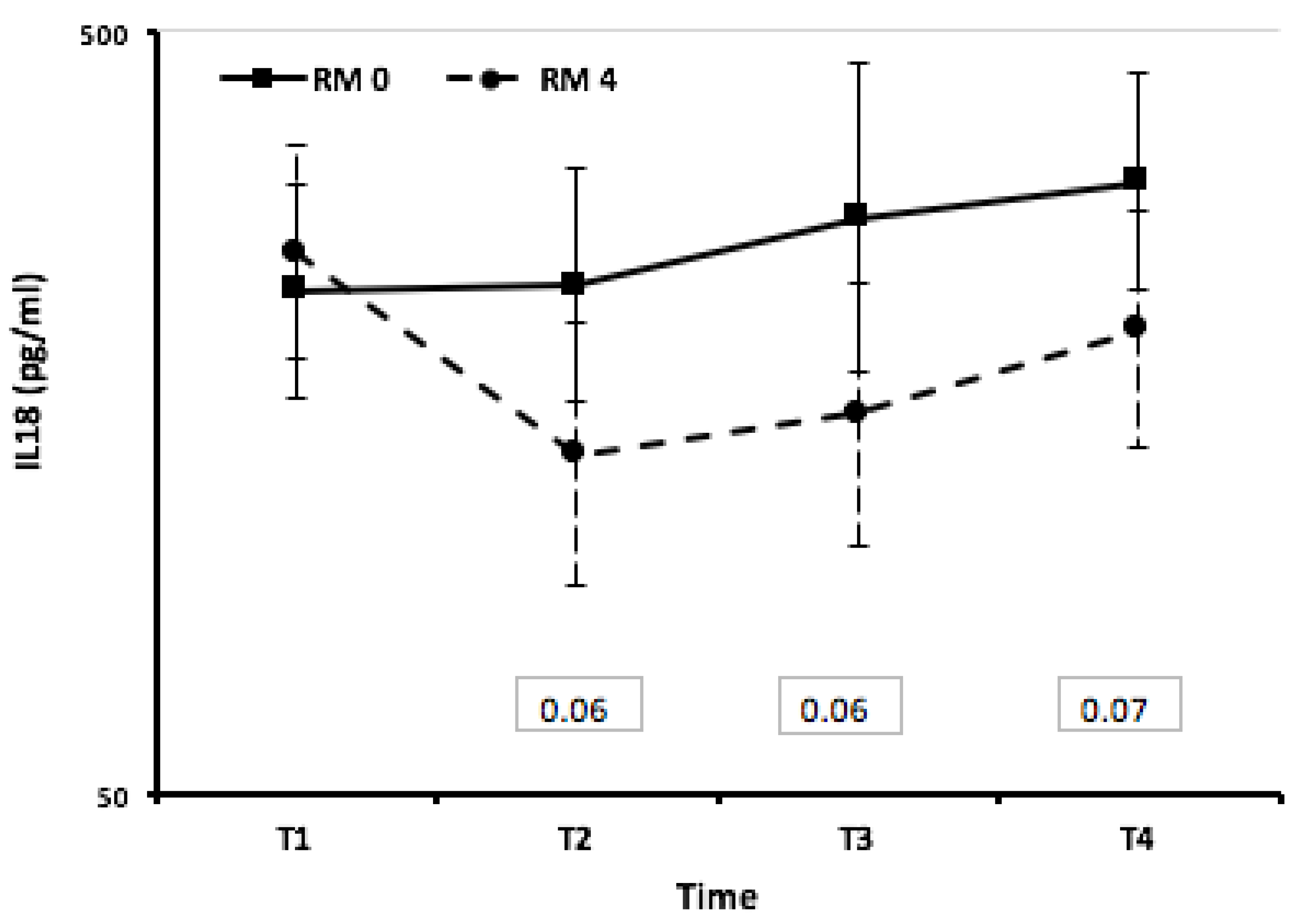

Figure 3). Infants with worse MRI 4 showed IL-18 level lower than those with normal MRI 0. Concentrations of IL-18 were similar in both groups at the start of TH and at 24 hours of life (T1). Subsequently, neonates with a brain damage detected by MRI showed a sharp decrease from the baseline and their mean values were almost significantly different from those estimated in neonates without brain damage (

Table 2,

Figure 4). Levels of INFγ showed a similar trend: at time points T2 and T3 they were lower in neonates with MRI 4 than in others, without reaching statistical significance (Supplemental File S1). Mean levels of CCL3MIP1alpha, GMCSF, IL1BETA overlapped, throughout the observation period, in both the groups of neonates (Supplemental Files S2,S5,S6). Mean levels of CCL2/MCP-1, at time point T1, were similar in the two group. Later, the group with normal MRI 0 had significantly higher CCL2/MCP-1 value than the other (p=0.01 and P=0.05, at T2 and T3, respectively) (Supplemental File S10). IL-33 values were higher in infants with normal MRI 0 than in those with abnormal MRI 4 in the first 48 hours of hypothermia, up to time point T2, without statistical significance. Then the IL-33 plasma values overlapped with those in the group of abnormal infants. (Supplemental File S4).

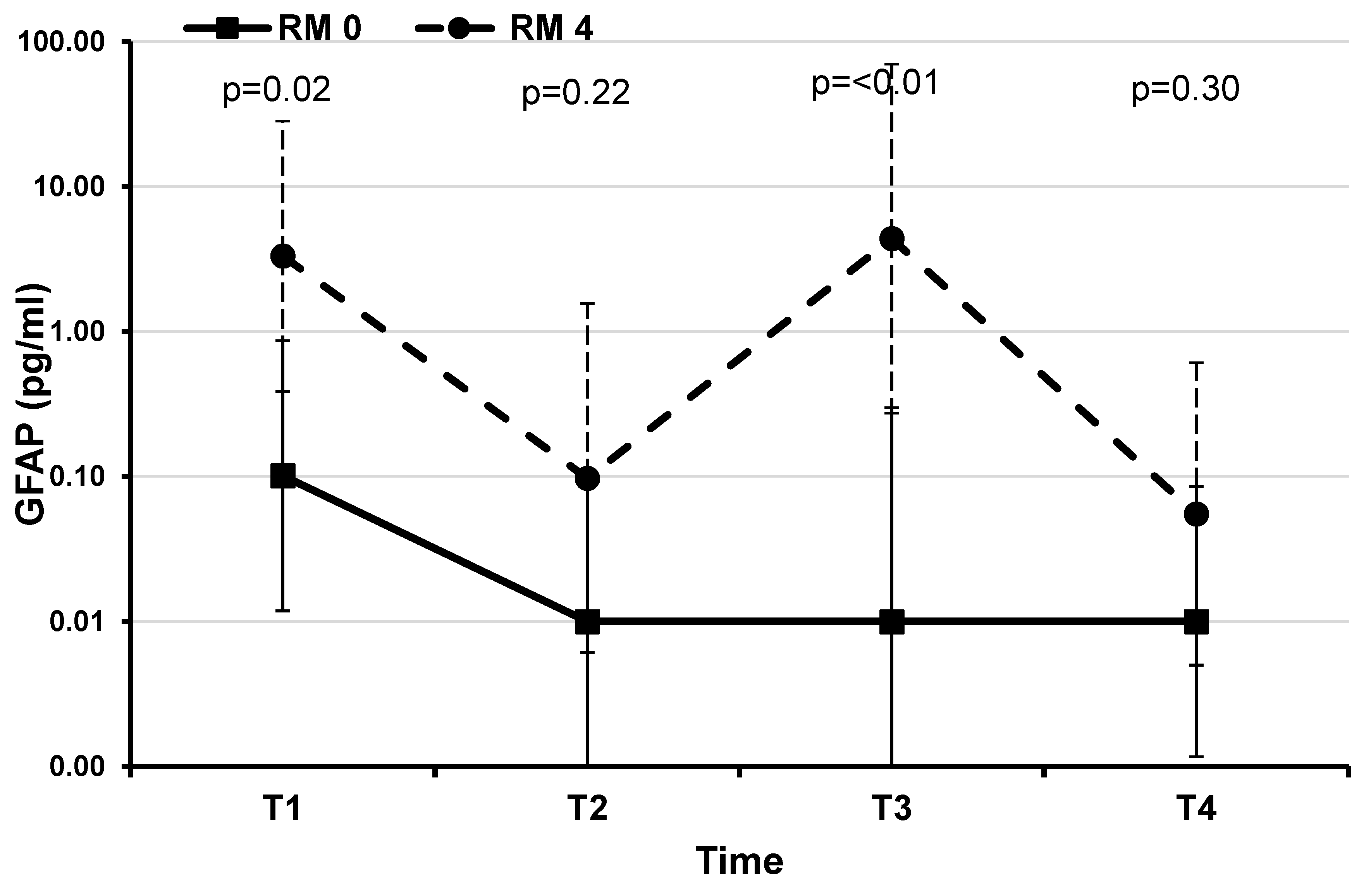

Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)

At T1 and T3 time points GFAP values were significantly higher in the patient with pathological MRI 4, compared to the patients with normal MRI 0 (

Table 2,

Figure 5).

No significant differences between the two groups of patients were found by comparing the values of all the other investigated molecules.

Discussion

In this preliminary study on neonates with moderate to severe asphyxia, treated with TH, we found that plasmatic levels of IL 10 were higher at T3 and T4 time points, IL-18 and IFNy were lower at T2 and T3 time points, and levels of CCL2/MCP-1were significantly lower in the group of neonates with pathological MRI 4 than in the other infants at T2 and T3. Moreover, according to the literature, GFAP was significantly higher in those patients with severe brain damage than in neonates with normal neuroimaging, through the entire observation period. We found the greatest, although not significant, differences between other molecules levels in cases and controls at time points T2 and T3, during TH. With the rewarming some molecules showed an upward trend or their values overlapped.

The role of neuroinflammation in neonatal central nervous system (CNS) lesions secondary to perinatal asphyxia as well as the role of cytokines as mediators of lesions have long been identified (13,14). Many of these cytokines such as IL-1𝛽, IL6, IL8, IL10 and IL12 seem to increase during inflammatory responses and can cause brain damage, through direct injury to the white matter, weakening the germinal matrix endothelium, cerebral hemorrhages and inflammatory reactions caused by microglia and astrocyte (15–17). The reduction in cerebral blood flow and oxygen delivery during asphyxia initiates a cascade of deleterious biochemical events, leading to the acute neuroinflammation. Such “biochemical storm” of various cytokines and chemokines acts at various levels of biochemical pathways, lasting for days, until several weeks after the initial insult. The proinflammatory response is followed by an anti-inflammatory and reparative phase. These events result either in resolution or in chronic inflammation. Hence a number of molecules have been suggested to be possible early sentinel biomarkers of HIE (17–19). Although pro-inflammatory cytokines, as in particular IL-6 and macrophage inflammatory protein 1a (CCL3/MIP-1a), have traditionally been thought to promote tissue damage, animal and human model studies describe a dual role of many of these mediators in the genesis of post asphyxiated repair (18,20–22). This duality may increase their potential utility as biomarkers, if different peaks could identify different stages of recovery. The exact mechanism of action of therapeutic hypothermia in the prevention of the brain damage in this setting has to be established, although some authors have recently reported a marked and significant decrease in cytokine levels, in infants treated with therapeutic hypothermia (15,16).

IL-10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine, with a role in the modulation of long-term brain damage, reducing the secondary inflammatory response of hypoxic cerebral ischemia. High IL-10 levels have been considered promising as a biomarker for identifying children at increased risk for adverse outcomes. Pang et al. in a recent research have demonstrated in a cohort of 316 Ugandan neonates, with and without HIE, that infants with moderate to severe brain damage had higher IL-10 levels (p < 0.001) than other patients. In addition, in infants with brain damage, IL-10 predicted neonatal mortality (p = 0.01) and adverse early childhood outcomes (adjusted OR 2.28, 95% CI 1.35–3.86, p = 0.002) (23,24). We also observed from time T2 (25-48 hours) a progressive increase of IL-10 levels in the group of infants with pathological MRI (Barkovich group 4), which almost reaches statistical significance at time T4 (7-10 days after the hypoxic insult).

In the group of patients with pathological MRI, we observed a decreasing IL-18 trend during hypothermia, while plasma levels were higher in infants without brain damage. IL-18 is a proinflammatory cytokine from the IL-1 family, produced preferentially by activated microglia and astrocytes and induces inflammation by IFNy production. Its expression is increased after neonatal HIE. It appears to be involved, as related to the inflammatory response, in many chronic brain pathologies. Although it may be a potential therapeutic target for some inflammation-mediated diseases, the role of IL-18 in intracerebral inflammatory damage still remains unclear. Recent studies in animal models have shown that IL-18 can regulate the inflammatory response following intracerebral hemorrhage (25). Therefore, IL-18 seems to play an important role in the development of white matter injury. In neonates treated with TH, IL-18 decreases during the first 24 hours and serum levels seem to be significantly lower in treated than in untreated neonates (25,26). Moreover, IL-18 serum levels seem to correlate with the severity of outcomes (27). Despite the available promising data regarding the role of IL-18 as possible precocious marker of brain injury, no conclusive correlation with patients’ brain MRI has been shown yet, and the involvement of IL-18 in brain susceptibility to perinatal asphyxia still remains an unsolved issue (28). In our patients, we observed a decreasing IL-18 trend during hypothermia, but plasma levels were higher in infants who did not show brain damage. What appears clearly is the IL-18 rising trend after cessation of the cooling, over 7 days from the hypoxic event, in both the groups of patients. Plasma levels of IFNy have a similar trend, showing an upward trend in case of brain damage at MRI starting from the end of TH (time point T3), without reaching a difference statistically significant between the two groups of neonates. Only limited data are available on the role of IFN-γ during TH. According to the existing knowledge, IFN-γ origins from activated macrophages/microglia and reactive astrocytes may coordinate the cellular immune and inflammatory responses in the central nervous system through the induction and interaction with other cytokines. Therefore, it seems logical to anticipate its dual role (protective as well as destructive), both of which are closely associated with the level and timing of its expression (29). In a recent study, IFN-γ levels were associated with increased severity of hypoxic-ischemic insult, as detectable by brain MRI (7). The level of this cytokine was found to be increased 6 to 72 hours after birth in cases of white matter damage in human perinatal brain injury. As presented in those studies, data reported still now regarding the role of IFN-γ are controversial and require further detailed researches.

IL -33 is a recently recognized cytokine, expressed and co-localized in particular in neurons and glial cells. Its specific receptor is the orphan IL-1 receptor ST2, in the two different forms: ST2 transmembrane and ST2 soluble. IL-33 appears to play a crucial effect on pathological changes and on the pathogenesis of diseases and injuries of the central nervous system, however, the specific role of IL-33 still remains confused. IL-33 is released by apoptotic and necrotic cells as a signaling molecule and its synthesis is closely linked to a dualistic function: linked to the transmembrane receptor ST2L it transmits a positive stimulatory signal, while linked to the soluble receptor sST2 it is deceptive and would play a negative role (30,31) IL-33 / ST2 has been reported to represent a potential immune regulatory mechanism to promote beneficial microglial responses and mitigate ischemic brain damage after stroke (32).

In neonatal HIE, glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP) is one of the most studied markers of brain damage, with respect to both the Sarnat score and tissue damage detectable by brain MRI. Patients with the worst Sarnat score show the highest GFAP and IL 10 levels in the first 24 hours after the hypoxic insult. Infants with better Sarnat scores show this increase later. At the end of hypothermia, the GFAP levels in the two groups of newborns become similar to each other, as if therapeutic hypothermia succeeded in postponing the increase in GFAP in the less compromised newborns (9). During asphyxia reactive astrocytes are characterized by hypertrophy of their cellular processes and show altered expression of many genes including the up-regulation of GFAP (11). GFAP is a skeletal intermediate filament protein in astrocytes, found in the white and gray matter of the CNS. GFAP is considered brain-specific, it is released rapidly out of damaged brain cells and is up-regulated through astrogliosis (33-34). Recent studies showed that GFAP is an ideal marker for the detection of ischemic brain damage and astrocyte activity in neonates with hypoxic ischemic brain damage (35,36). A study of hypoxia ischemia in newborn piglets showed that periventricular white matter astrocytes were reduced in number, with a smaller cell size, and decreased GFAP content (37), suggesting that the hypoxic ischemia may cause astrocyte damage and increased cell death. GFAP has been measured also on the Cerebral Spinal Fluid (CSF) (14,38,39) and its concentrations increases and correlates significantly with indicators of long-term prognosis and with neurological outcome. In our patients, divided into normal and severe, according to MRI examination at 7-10 day of life, we observed high plasma levels of GFAP within the first 24 hours in both the two groups of infants and then its decline. Infants with pathological neuroimaging showed a subsequent plasma GFAP increase and then, after the hypothermia cessation, levels tended to be more similar to those of the normal group. Chalak et al. demonstrated that GFAP serum concentrations >0.08 pg/ml had a positive predictive value 100% for predicting infants with abnormal outcomes (40). Reports also showed that at a cut-off value of 0.07 ng/ml, the sensitivity and specificity of GFAP for the diagnosis of neonatal HIE was 77% and 78%, respectively (41). Consistent with these evidences, in our study the patient with worst MRI had GFAP concentration > 0,08 pg/ml in the first 24 hours of life and between 48 and 72 hours of life. Moreover, comparing neonates treated and not treated with TH, Ennen et al. (42) showed that in the first group there was an increase in GFAP concentrations in the first 6 hours of life, then a decrease and finally a new increase at 72 hours of life. This is comparable with the GFAP level tendency detected in our group of neonates with pathological MRI. Furthermore, that study confirms that patients with pathological MRI have higher GFAP concentration. In our cohort, GFAP was high already from T1 up to T3, and it only decreased at T4, after one week from the hypoxic event. Understanding the relationships between cytokines and biomarkers of seriousness and how TH exposure may modulate them could provide new information on the type and severity of tissue injury, to guide treatment and refine predictive models.

In summary, although failing to reach statistical significance, given the low number of patients, what seems to emerge from the plasma profiles of the molecules examined is a general decrease in the plasma levels of the molecules studied during the hypothermic treatment phase (T2 and T3 time points) and an apparent upward trend of the plasma profiles of some of them (GMCSF, IFN-γ, TNF α, IL-10, IL-18, IL-1 beta) during the rewarming and later.

In particular IL-10 and GFAP could help to evaluate the outcome and to benchmark evolving HIE therapies, while IL-18, IFγ, TNF α, IL-1 cannot currently be used for prognostic purposes because of not linear data in different studies. Findings in neonates with HIE support the search for biomarkers in addition to the neurological examination to better stratify subgroups that might benefit from additional neuroprotective therapies. Due to the small study sample included in the present plot study, it is not possible to correlate the degree of brain injury to the levels of GFAP or the sensitivity of circulating GFAP for detecting injury in specific brain segments.

Conclusions

At specific time points after hypoxic insult, in asphyxiated neonates with serious brain damage we found higher levels of GFAP and of IL-10, than in babies without pathological MRI. According to the literature they could be early biomarkers of brain damage and adverse neurological outcome respectively. We observed a not significant trend in decreasing of plasma levels of some molecules during the 72 hours of therapeutic hypothermia. With the rewarming some molecules showed an up-ward trend. However, it cannot be excluded that the small sample size may both prevent significance in the differences from being achieved. These questions need to be addressed with larger and more diverse groups of brain-injured neonates, in order to identify an ideal marker for the detection of ischemic brain damage and astrocyte activity in neonates with hypoxic ischemic brain injury.

Author Contributions

CA, GP, FP and IB designed the research project. CA, IB, FP and DL recruited patients. DL and GL interpreted and reported the neuroimages, LT did the statistical analysis of the data, VM, FP, IB managed the database, GP and TDP performed the dosages of the biomarkers. CA, VM and FP wrote the first draft of the manuscript. GP revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was financed by the Bambino Gesù Hospital with research funds code 201703P004152.

Acknowledgments

In this section you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare relevant to this article.

References

- Vanucci, R.C.; Perlman, J.M. Intervention for perinatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, Pediatrics 1997,100: 1004–1014. [CrossRef]

- Shankaran, S.; Laptook, A.R.; Ehrenkranz, R.A.; Tyson, J.E.; McDonald, S.A.; Donovan, E.F.; et al. Whole- body hypothermia for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005, 353:1574–1584. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, R.D.; Raju, T.N.K.; Edwards, A.D.; Azzopardi, D.V.; Bose, C.L.; Clark, R.H.; et al. Hypothermia and other treatment options for neonatal encephalopathy: an executive summary of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Workshop. J Pediatr. 2011; 159:851.e1–858.e1. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Xue, X.D.; Fu, J.H. Research status and progress of neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, Chin. J. Pract. Pediatr. 2009,24: 968–971.

- Pappas, A.; Korzeniewski, S.J. Long-Term Cognitive Outcomes of Birth Asphyxia and the Contribution of Identified Perinatal Asphyxia to Cerebral Palsy. Clin Perinatol. 2016, 43:559-72. [CrossRef]

- Ahearne, C.E.; Boylan, G.B.; Murray, D.M. Short and long term prognosis in perinatal asphyxia: An update. World J Clin Pediatr. 2016; 5:67-74. [CrossRef]

- Massaro, A.N.; Wu, Y.W.; Bammler, T.K.; Comstock, B.; Mathur, A.; McKinstry, R.C.; Chang, T.; Mayock, D.E.; Mulkey, S.B.; Van Meurs, K.; Juul, S. Plasma Biomarkers of Brain Injury in Neonatal Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy. J Pediatr. 2018; 194:67-75. [CrossRef]

- Carreras, N.; Arnaez, J.; Valls, A.; Agut, T.; Sierra, C.; Garcia-Alix, A. CSF neopterin and beta-2-microglobulin as inflammation biomarkers in newborns with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatr Res. 2022; Apr 6. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Lv, H.; Wu, S.; Song, J.; Li, J.; Huo, H.; Ren, P.; Li, L. Effect of Hypothermia on Serum Myelin Basic Protein and Tumor Necrosis Factor-α in Neonatal Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy. Am J Perinatol. 2022; 39:1367-1374. [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Valdez, R.; Miller, S.; Spahic, H.; Vaidya, D.; Parkinson, C.; Dietrick, B.; Brooks, S.; Gerner, G.J.; Tekes, A.; Graham, E.M.; Northington, F.J.; Everett, A.D. Therapeutic Hypothermia Modulates the Relationships Between Indicators of Severity of Neonatal Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy and Serum Biomarkers. Front Neurol. 2021;12: 748150. [CrossRef]

- Bernis E.M.; , Schleehuber Y.; Zweyer M.; Elke Maes E.; Ursula Felderhoff-Müser U.; Picard D.; and Sabir H. Temporal Characterization of Microglia-Associated Pro- and Anti-Inflammatory Genes in a Neonatal Inflammation-Sensitized Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Injury Model Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity Volume 2022; Article ID 2479626, 16 pages . [CrossRef]

- Barkovich, A.J.; Hajnal, B.L.; Vigneron, D.; et al. Prediction of neuromotor outcome in perinatal asphyxia: evolution of MR scoring system. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1998; 19: 143-150.

- Hagberg, H. ; C. Mallard C.; Ferriero D.M.; Vannucci S.J.; Levison S.W.; VexlerZ.S.; et al. The role of inflammation in perinatal brain injury, Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2015;11: 192–208. [CrossRef]

- Savman, K.; Blennow, M.; Gustafson, K.; Tarkowski, E. ; H. Hagberg H.; Cytokine response in cerebrospinal fluid after birth asphyxia, Pediatr. Res. 1998;43: 746–751. [CrossRef]

- Orrock, J.E.; Panchapakesan, K.; Vezina, G.; Chang, T.; Harris, K.; Wang, Y.; et al. Association of brain injury and neonatal cytokine response during therapeutic hypothermia in newborns with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, Pediatr.Res.2016; 79: 742–747. [CrossRef]

- Perrone, S.; Weiss, M.D.; Proietti, F.; Rossignol, C.; Cornacchione, S.; Bazzini, F.; Calderisi, M.; Buonocore, G.; Longini, M. Identification of a panel of cytokines in neonates with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy treated with hypothermia. Cytokine. 2018;111:119-124. Epub 2018 Aug 22. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; McCullough, L. Inflammatory responses in hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2013; 34:1121–30. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hallenbeck, J.; Ruetzler, C.; Bol, D.; Thomas, K.; Berman, N.; Vogel, S. Overexpression of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 in the brain exacerbates ischemic brain injury and is associated with recruitment of inflammatory cells. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003; 23:748–55. [CrossRef]

- Cowell, R.M.; Xu, H.; Galasso, J.M.; Silverstein, F.S. Hypoxic-ischemic injury induces macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha expression in immature rat brain. Stroke 2002; 33:795e801. [CrossRef]

- Matsuda S, Wen TC, Morita F, Otsuka H, Igase K, Yoshimura H, Sakanaka M (1996) Interleukin-6 prevents ischemia-induced learning disability and neuronal and synaptic loss in gerbils. Neurosci Lett 204:109–12. [CrossRef]

- Loddick, S.A.; Turnbull, A.V.; Rothwell, N.J. Cerebral interleukin-6 is neuroprotective during permanent focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1998; 18:176–9. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Tanaka, K.; Suzuki, N. Ambivalent aspects of IL-6 in cerebral ischemia: inflammatory versus neurotrophic aspects. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2009; 29: 464–79.

- Pang, R. ; Mujuni BM, Martinello KA, Webb EL, Nalwoga A, Ssekyewa J, Musoke M, Kurinczuk JJ, Sewegaba M.; Cowan F.M.; Cose S.; Nakakeeto M.; Elliott A.M.; Sebire N.J.; Klein N.; Robertson N.J.; Tann C.J. Elevated serum IL-10 is associated with severity of neonatal encephalopathy and adverse early childhood outcomes. Pediatr Res. 2022;92:180-189. Epub 2021 Mar 5. [CrossRef]

- Winerdal, M.; et al. Long lasting local and systemic inflammation after cerebral hypoxic ischemia in newborn mice. PLoS ONE. 2012; 7: e36422. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Tian, J.; Yin, Y. , Diao S.; Zhang, X.; Zuo, T.; Miao, Z. & Yang, Y. Interleukin-18 mediated inflammatory brain injury after intracerebral hemorrhage in male mice. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 2022;100, 1359– 1369. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Liu, G.; Yang, X.; Liu, Q.; Li, Z. Effect of mild hypothermia on the expression of IL-10 and IL-18 in neonates with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Exp Ther Med. 2019;18: 2194–2198. [CrossRef]

- Douglas-Escobar, M.; Weiss, M.D. Biomarkers of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in newborns. Front Neurol 2012; 3: 144-148. [CrossRef]

- Ciaramella, A.; Della Vedova, C.; Salani, F.; Viganotti, M.; D'Ippolito, M.; Caltagirone, C.; Formisano, R.; Sabatini, U.; Bossù, P. Increased levels of serum IL-18 are associated with the long-term outcome of severe traumatic brain injury. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2014; 21:8-12. [CrossRef]

- Hansen-Pupp, I.; Harling, S.; Berg, A.C.; Cilio, C.; Hellström-Westas, L.; Ley, D. Circulating interferon-gamma and white matter brain damage in preterm infants. Pediatr Res. 2005; 58 :946-52. Erratum in: Pediatr Res. 2006 May;59(5):735. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Ma, L.; Luo, C.L. , Wang T.; Zhang M.Y.; Shen X.; Meng H.H.; Ji M.M.; Wang Z.F.; Chen X.P.; Tao L.Y. IL-33 Exerts Neuroprotective Effect in Mice Intracerebral Hemorrhage Model Through Suppressing Inflammation/Apoptotic/Autophagic Pathway. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54:3879-3892. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Luo, C.; Yao, Y.; Huang, J.; Fu, H.; Xia, C.; Ye, G.; Yu, L. ; Han J, Fan Y.; and Tao L. IL-33 Alleviated Brain Damage via Anti-apoptosis, Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress, and Inflammation After Epilepsy. Front. Neurosci. 2020;14:898. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H.; Ye, Q.; Wang, J.; Yang, B.; Mao, L.; Zhu, W.; Leak, R.K.; Xiao, B.; Lu, B.; Chen, J.; Hu, X. ST2/IL-33-Dependent Microglial Response Limits Acute Ischemic Brain Injury. J Neurosci. 2017; 37:4692-4704. Epub 2017 Apr 7. [CrossRef]

- Missler, U.; Wiesmann, M. ; WittmannG.; Magerkurth O.; H. Hagenström H. Measurement of glial fibrillary acidic protein in human blood: analytical method and preliminary clinical results. Clin Chem 1999; 45:138-141. [CrossRef]

- Pelinka, LE.; Kroepfl, A.; Leixnering, M. ; BuchingerW.; Raabe A.; H. Redl H. GFAP versus S100B in serum after traumatic brain injury: relationship to brain damage and outcome. J Neurotrauma 2004; 21:1553-1561.

- Herrmann, M.; Vos, P.; Wunderlich, M.T.; de Bruijn C. H. M., M. ; K. J. B. Lamers K.G.B. Release of glial tissue-specific proteins after acute stroke: A comparative analysis of serum concentrations of protein S-100B and glial fibrillary acidic protein. Stroke 2000; 31:2670-2677.

- Yasuda, Y. ; TateishiN.; Shimoda T.; Satoh S.; Ogitani E.; Fujita S. Relationship between S100beta and GFAP expression in astrocytes during infarction and glial scar formation after mild transient ischemia. Brain Res 2004; 1021:20-31.

- Sulliva, S.M.; Bjǒrkman, S.T.; Miller, S.M. et al., Morphological changes in white mat- ter astrocytes in response to hypoxia/ischemia in the neonatal pig, Brain Res.2010; 1319: 164–174.

- Blennow, M. ; H. Hagberg.; L. Rosengren. Glial fibrillary acidic protein in the cerebrospinal fluid: a possible indicator of prognosis in full-term asphyxiated newborn infants? Pediatr Res 1995; 37:260-264.

- Sävman, K.; Blennow, M.; Gustafson, K.; Tarkowski, E.; Hagberg, H. Cytokine response in cerebrospinal fluid after birth asphyxia. Pediatr Res. 7: 1998; 43, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chalak, L.K.; Sánchez, P.J.; Adams-Huet, B. et al., Biomarkers for severity of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy and outcomes in newborns receiving hypothermia therapy, J. Pediatr. 2014;164: 468–474. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.H.; Wang, J.X.; Zhang, Y.M. et al. Effect of hypothermia therapy on serum GFAP and UCH-L1 levels in neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, Chin. J. Contemp. Pediatr.2014; 16: 1193–1196.

- Ennen, C.S.; Huisman, T.A.; Savage, W.J. et al. Glial fibrillary acidic protein as a biomarker for neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy treated with whole-body cooling. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011; 205: 251.e1–251.e2517. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

MRI axial DWI/ADC images (a,b,e,f) show restricted diffusion in basal ganglia, cortex and corpus callosum in asphyxiated neonate. T2 axial and coronal images (c,g) show cortical edema, resulting in marked loss of normal cortical/white matter contrast ; hyperintensity in T1 axial image (d,h) indicate bilateral injury of basal ganglia and cortical precentral gyrus Acute and severe hypoxia in term infants results in damage to the gray matter, especially the basal ganglia with Barckovich score 4 (BG/W).

Figure 1.

MRI axial DWI/ADC images (a,b,e,f) show restricted diffusion in basal ganglia, cortex and corpus callosum in asphyxiated neonate. T2 axial and coronal images (c,g) show cortical edema, resulting in marked loss of normal cortical/white matter contrast ; hyperintensity in T1 axial image (d,h) indicate bilateral injury of basal ganglia and cortical precentral gyrus Acute and severe hypoxia in term infants results in damage to the gray matter, especially the basal ganglia with Barckovich score 4 (BG/W).

Figure 2.

Normal signal in axial DWI/ADC images (a,b,e,f) ,T2 axial and coronal images and T1 axial image (d,h) in patient with Barkovich score 0 , and moderate brain injury.

Figure 2.

Normal signal in axial DWI/ADC images (a,b,e,f) ,T2 axial and coronal images and T1 axial image (d,h) in patient with Barkovich score 0 , and moderate brain injury.

Figure 3.

IL10: estimated mean plasma values during therapeutic hypothermia and after rewarming in 10 infants with perinatal asphyxia stratified by MRI results (mixed linear regression model). In our two groups of patients, mean values of IL-10 showed the same trend until the time point T2, when the pathologic MRI 4 group showed a level increase, that reaches almost the statistical significance.

Figure 3.

IL10: estimated mean plasma values during therapeutic hypothermia and after rewarming in 10 infants with perinatal asphyxia stratified by MRI results (mixed linear regression model). In our two groups of patients, mean values of IL-10 showed the same trend until the time point T2, when the pathologic MRI 4 group showed a level increase, that reaches almost the statistical significance.

Figure 4.

IL18: estimated mean plasma values during therapeutic hypothermia and after rewarming in 10 infants with perinatal asphyxia stratified by MRI results (mixed linear regression model). Both groups have similar mean values at the first evaluation within 24 hours. Subsequently, children with a brain damage showed a sharp decrease from the baseline and their mean values were quite statistically significant different from those estimated in children with no-brain damage.

Figure 4.

IL18: estimated mean plasma values during therapeutic hypothermia and after rewarming in 10 infants with perinatal asphyxia stratified by MRI results (mixed linear regression model). Both groups have similar mean values at the first evaluation within 24 hours. Subsequently, children with a brain damage showed a sharp decrease from the baseline and their mean values were quite statistically significant different from those estimated in children with no-brain damage.

Figure 5.

GFAP: estimated mean plasma values during therapeutic hypothermia and after rewarming in 10 infants with perinatal asphyxia divided by MRI results. Graph made with logarithmic scale). Children with no brain damage had at each evaluation lower mean values compared to those with brain damage. At T1 and T3 we found a statistically significant difference.

Figure 5.

GFAP: estimated mean plasma values during therapeutic hypothermia and after rewarming in 10 infants with perinatal asphyxia divided by MRI results. Graph made with logarithmic scale). Children with no brain damage had at each evaluation lower mean values compared to those with brain damage. At T1 and T3 we found a statistically significant difference.

Table 1.

General characteristics of 10 newborns with birth asphyxia, stratified by MRI results. Mean ± deviation standard. Compared by T-test student.

Table 1.

General characteristics of 10 newborns with birth asphyxia, stratified by MRI results. Mean ± deviation standard. Compared by T-test student.

| |

Normal MRI |

Pathological MRI |

p |

| Birth weight (g) |

3540 ± 869 |

2708 ± 519 |

0,111 |

| Gestational age (ws+ds) |

39+1 ± 1+5

|

38+4 ± 1+6

|

0,64 |

| Apgar 1 min |

3,8 ± 0,8 |

4,2 ± 1,7 |

0,66 |

| Apgar 5 min |

5,2 ± 0,8 |

6,2 ± 0,8 |

0,095 |

| pH |

6,97 ± 0,16 |

7,03 ± 0,34 |

0,72 |

| BE |

18,6 ± 5,2 |

17,9 ± 8,3 |

0,97 |

Table 2.

IL-10, IL-18 and GFAP estimated plasma mean concentration at different time points, during therapeutic hypothermia and after rewarming, in 10 newborns with birth asphyxia, stratified by MRI results .

Table 2.

IL-10, IL-18 and GFAP estimated plasma mean concentration at different time points, during therapeutic hypothermia and after rewarming, in 10 newborns with birth asphyxia, stratified by MRI results .

| |

Normal MRI |

Pathological MRI |

|

| |

mean |

95% CI |

mean |

95% CI |

p-value |

| IL-10 (pg/ml) |

| T1 |

14,69 |

0,96-225,23 |

43,96 |

2,87-674,21 |

0,56 |

| T2 |

0,07 |

0,00-1,36 |

0,01 |

0,00-0,38 |

0,47 |

| T3 |

0,12 |

0,00-8,03 |

6,17 |

0,19-200,90 |

0,16 |

| T4 |

0,04 |

0,00-0,56 |

1,72 |

0,08-35,78 |

0,06 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| IL-18 (pg/ml) |

| T1 |

228,23 |

164,8-316,06 |

256,62 |

185,30-355,37 |

0,50 |

| T2 |

231,78 |

162,89-329,80 |

139,16 |

93,75-206,57 |

0,06 |

| T3 |

284,57 |

178,72-453,10 |

157,37 |

105,94-233,79 |

0,06 |

| T4 |

317,39 |

229,18-439,53 |

203,07 |

142,52-289,35 |

0,07 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| GFAP (pg/ml) |

| T1 |

0,101 |

0,012-0,867 |

3,317 |

0,388-28,387 |

0,02 |

| T2 |

0,010 |

0,001-0,110 |

0,097 |

0,006-1,556 |

0,22 |

| T3 |

0,010 |

0,000-0,298 |

4,377 |

0,274-69,962 |

<0,01 |

| T4 |

0,010 |

0,001-0,086 |

0,055 |

0,005-0,608 |

0,30 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).