1. Introduction

One in three people globally suffer from at least one form of poor nutrition. As an example, micronutrient deficiencies affect two out of three women and overweight/obesity affect at least one in ten people globally [

1,

2]. It is estimated that diet related diseases result in 11 million deaths annually and 255 million disability adjusted life years worldwide from poor health outcomes including anemia, hypertension, heart disease and diabetes [

2]. Consequently, malnutrition of all forms also brings significant losses in productivity and potential, posing challenges to employers in both high- and low- and middle-income countries (HICs and LMICs) [

3]. Given that about 60% of the global population will spend one third of their time at work during their adult life and employers have an incentive to maximise performance, the workplace offers an important, relatively unexploited opportunity to address malnutrition in all its forms [

3,

4,

5].

Workers commonly consume at least one meal during their working hours, whether operating from a field, a machine, or a desk. The environment in which people work can influence their access to and choice of foods, making worksites important avenues to promote adequate nutrition and healthy eating. Workforce nutrition programmes are interventions offered to workers through workplace delivery structures that intend to contribute to the nutritional needs of the worker population, which can encompass direct employees, indirect workers (in supply chains) and workers’ households’ members. Workforce nutrition interventions apply to any worksite setting, and can focus on addressing a wide range of nutritional challenges, from healthy eating broadly, to consequences of poor nutrition including overweight/obesity, non-communicable diseases (NCDs), anemia (and/or other micronutrient deficiencies), and/or underweight. Furthermore, workforce nutrition interventions are often integrated into wider employee health and wellbeing programmes, aimed at improving the physical, mental and social health of workers [

3,

4].

Workforce nutrition programmes have been characterized using a ‘four-pillar’ framework, which includes the following areas [

6]:

Access to healthy food interventions, which consist of the employer increasing access to nutritious foods for free or at subsidised costs, and/or making changes to the workplace food environment (e.g., healthier canteen menus, healthier snacks and beverages in vending machines, more balanced portion sizes and meal composition).

Nutrition education programmes, that aim to change employees’ dietary and/or lifestyle behaviours by increasing their nutritional knowledge and health literacy. Examples of interventions are cooperative menu planning, cooking demonstrations, dissemination of educational materials, interactive information sessions/workshops and interpersonal communication.

Nutrition-focused health checks (and counselling), which are periodic one-to-one consultations with a health or nutrition professional to assess and discuss the employee’s nutritional and health status. Health checks help employees get a better understanding of their nutritional and health risk factors, for example through cholesterol and blood-pressure screenings, or weight monitoring and classification (Body Mass Index, BMI). Follow-up counselling can be provided in addition to health checks, to advise employees on potential dietary and lifestyle changes.

Breastfeeding support interventions, which include programmes and/or policies aiming to enable working mothers to breastfeed their child exclusively for 6 months (i.e., providing only breastmilk to a child as per World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations) and continually up to 2 years [

7]. Examples of policies and interventions are respecting or exceeding national laws on duration of paid maternity leave, providing breastfeeding rooms and onsite childcare (where relevant), breastfeeding or breastmilk expression breaks, and flexible work schedules for mothers. In addition, breastfeeding support programmes can include awareness-raising or nutrition education campaigns for mothers and co-workers on the importance and benefits of breastfeeding.

This framework has been adopted and/or recognized by the Workforce Nutrition Alliance, the Access to Nutrition Index and the World Benchmarking Alliance, as well as numerous commitment makers in the Nutrition for Growth Summit in December 2021.

This literature review aims to investigate the potential for impact of workforce nutrition programmes on nutrition, health, and business outcomes, using the four-pillar framework. Specific objectives include: 1) to examine the extent, nature, and distribution of available high-strength-of-evidence literature; 2) to summarize and disseminate research findings, to inform policy and programmes; and 3) to identify potential gaps in the existing literature, to recommend a future research agenda. In addition, by categorizing and assessing the available evidence using this framework, this literature review will contribute to improving comparability of reporting on nutrition, health, and business outcomes of workforce nutrition interventions, enhancing standardization of methods and indicators for future programme evaluations and evidence reviews. To our knowledge this is the first time that a review assesses the existing high-strength-of-evidence literature on workforce nutrition interventions using the ‘four-pillar’ framework.

2. Methods

The primary data source used was PubMed. Language and time search limits were set to English language and January 2010-October 2021. Moreover, filters were applied for the following publication types: systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Two key concepts were identified: 1) the workplace setting, and 2) nutrition, based on which a series of relevant search terms were chosen. Search terms related to the first key concept included: "workplace" OR "workforce" OR "worksite". Search terms related to the second key concept included: "nutrition" OR "nutrition policy" OR "nutrition program(me)" OR "nutrition intervention".

The following search strategy was developed: at least one search term related to the first key concept AND one search term related to the second key concept had to be included in the title and/or abstract of articles, resulting in a total of 36 identified studies. The full search string used (including language, time and publication type filters) is reported below:

((("workplace"[Title/Abstract] AND "nutrition"[Title/Abstract]) OR ("workplace"[Title/Abstract] AND "nutrition"[Title/Abstract] AND "program"[Title/Abstract]) OR ("workplace"[Title/Abstract] AND "nutrition"[Title/Abstract] AND "policy"[Title/Abstract]) OR ("workplace"[Title/Abstract] AND "nutrition"[Title/Abstract] AND "intervention"[Title/Abstract]) OR ("workforce"[Title/Abstract] AND "nutrition"[Title/Abstract]) OR ("workforce"[Title/Abstract] AND "nutrition"[Title/Abstract] AND "program"[Title/Abstract]) OR ("workforce"[Title/Abstract] AND "nutrition"[Title/Abstract] AND "policy"[Title/Abstract]) OR ("workforce"[Title/Abstract] AND "nutrition"[Title/Abstract] AND "intervention"[Title/Abstract]) OR ("worksite"[Title/Abstract] AND "nutrition"[Title/Abstract]) OR ("worksite"[Title/Abstract] AND "nutrition"[Title/Abstract] AND "program"[Title/Abstract]) OR ("worksite"[Title/Abstract] AND "nutrition"[Title/Abstract] AND "policy"[Title/Abstract]) OR ("worksite"[Title/Abstract] AND "nutrition"[Title/Abstract] AND "intervention"[Title/Abstract])) AND ("systematic review"[Filter] AND 2010/01/01:2021/10/31[Date - Publication]) AND ("meta analysis"[Publication Type] OR "randomized controlled trial"[Publication Type] OR "systematic review"[Filter]) AND 2010/01/01:2021/10/31[Date - Publication]) AND ((meta-analysis[Filter] OR randomizedcontrolledtrial[Filter] OR systematicreview[Filter]) AND (2010/1/1:2021/10/31[pdat]))

In addition to the electronic database search, a rapid hand-search was conducted on Google Scholar, which yielded 16 additional studies.

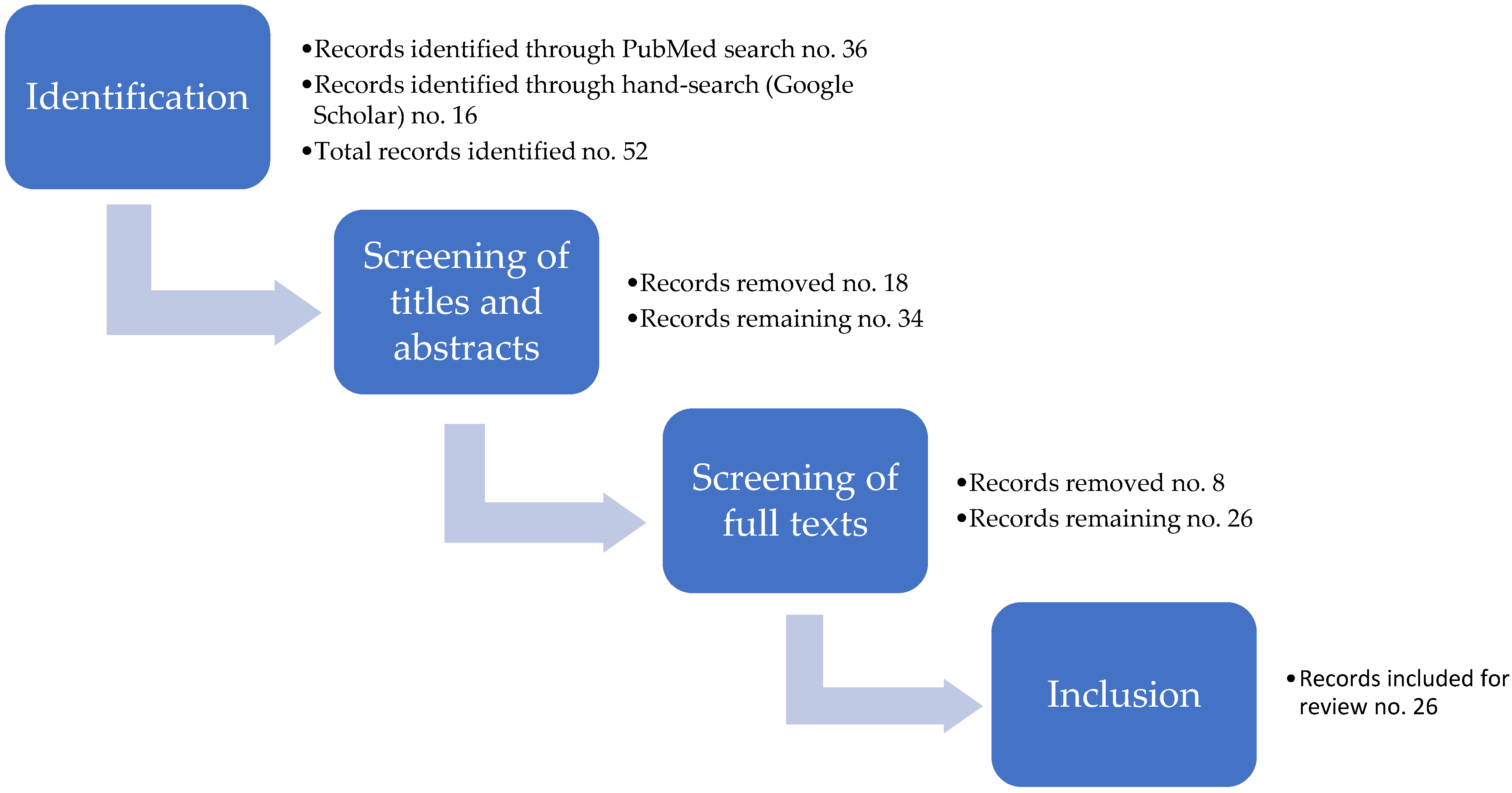

The study selection process consisted of two subsequent stages: 1) initial screening of articles’ titles and abstracts for potential inclusion; and 2) screening of articles’ full texts to confirm their eligibility for review, based on the following criteria:

Having a clear focus on workforce nutrition, either as a stand-alone subject or as a principal component of broader workforce health and wellness (i.e., studies focusing solely on workplace physical activity interventions were excluded, while articles focusing both on worksite nutrition and physical activity programmes were included).

Peer-reviewed articles with high strength of evidence (i.e., systematic reviews, meta-analyses and RCTs) (

Figure 1). The main rationale for this choice is that the body of literature on workforce nutrition is increasing rapidly, however, only a small subset of it presents high strength of evidence.

Touching on one or more of the four pillars of workforce nutrition policies and programmes described in the Introduction.

Discussing the effects of workforce nutrition policies and programmes on nutrition, health and/or business (financial) outcomes.

After completion of the study selection process, a total of 26 records were identified as meeting the above criteria and were included in the review. The different stages of the study selection process are summarised in a flow diagram, which is presented in

Figure 2.

Relevant data from included studies were extracted and organised by using a Data Charting Form to report on the following: 1) article details and general information, including title, author(s) and year, type of publication, primary aim(s), country(ies) and income level(s), workforce nutrition pillar(s) addressed; and 2) key aspects of interest to this review, including outcome measures used, programme/intervention duration, results obtained, conclusions, lessons learned and recommendations. The same extraction framework was applied systematically to all articles reviewed, aiming for a uniform, standardized approach.

A narrative review of the included studies was conducted, aiming to provide both descriptive and analytical insights, and to draw lessons and recommendations for future workforce nutrition policies, programmes and related research.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive (numerical) analysis of included records

As mentioned above, at the end of the study selection process a total of 26 records were included for review. Most of them (21 records) were systematic reviews (six of which included a meta-analysis), and the remaining (five records) were RCTs.

More than two-thirds of all reviewed publications (18 records, or 69%) focused on high-income countries (HICs), five included both HICs and upper-middle-income countries (UMICs), two included both HICs and lower-middle-income countries (LMICs), and only one record focused solely on LMICs.

In terms of workforce nutrition pillars addressed, most publications reported on interventions including health checks and counselling and nutrition education components (eight records, or 31%), and on studies focusing on comprehensive programmes comprising access to healthy food, health checks and counselling, and nutrition education combined (eight records, or 31%). As for the other records, four discussed workforce breastfeeding support programmes; two reported on access to healthy food interventions alone; two focused on nutrition education programmes alone; and two discussed access to healthy food and nutrition education interventions combined. No publications focusing on health checks and counselling programmes alone were found.

Regarding the types of outcomes measured, the vast majority of included studies (20 records, or 77%) assessed a variety of nutrition and/or health outcomes, while less than half (12 records) evaluated business outcomes, and only four measured breastfeeding-specific outcomes.

Table 1 summarizes key findings from the descriptive analysis above.

3.2. Content (thematic) analysis of included records

The results from the content analysis have been organised against the four workforce nutrition pillars presented in the Introduction, either as stand-alone interventions or as comprehensive programmes including multiple pillars. For additional details on each included record, please refer to the Data Charting Form available in the

Supplementary Material document.

3.2.1. Records only including access to healthy food interventions

The two records discussing access to healthy food interventions alone focused on HICs only. One of them is an RCT targeting urban, low-wage workers [

9], and the other is a systematic review of three RCTs targeting overweight/obese office workers [

10]. All interventions offered free, discounted or otherwise-incentivized nutritious foods and found positive effects on dietary outcomes but not on body weight [

9,

10]. Specifically, both reported increased fruit intake, and one of them also reported higher vegetable intake [

9,

10]. Interestingly, the RCT conducted among low-wage workers showed impact through employer-provided take-home food rations, rather than food provided at the worksite [

9]. This approach, which also applied behavioral economics, resulted in greater consumption of home cooked meals [

9], thus, potentially benefiting not only workers themselves, but also their families, although outcomes on family members were not assessed.

3.2.2. Records only including nutrition education interventions

Only two records – two RCTs covering both a LMIC and a HIC – focused on nutrition education interventions alone [

11,

12]. Overall, the evidence is mixed and inconclusive for the effects of stand-alone nutrition education programmes on health, nutrition and business outcomes. In particular, one RCT targeting factory workers in Iran found positive initial results on knowledge and awareness levels, body weight, BMI, and biological indicators for diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD), but did not assess longer-term impact beyond three months [

9]. The second RCT, which evaluated the effects of calorie labelling in six worksite cafeterias in the UK on workers’ caloric intake, found inconclusive results [

11,

12].

3.2.3. Records only including health checks and counselling interventions

No records were found as part of this review which focused on health checks and counselling alone. All records including this component are assessed below under combined interventions.

3.2.4. Records only including breastfeeding support interventions

Four records – all systematic reviews – focused on workforce breastfeeding support programmes, two of which included some studies conducted in LMICs [

13,

14], while the other two only included studies in HICs [

15,

16]. Common across all breastfeeding support programmes were lactation rooms, breastfeeding breaks and some support services, and all interventions were implemented as part of worksite policies [

13,

14,

15,

16], in some cases as a result of national labor laws [

15,

16]. Consistently positive impact was found across all records on breastfeeding duration and/or exclusive breastfeeding, and – where business outcomes were assessed – job satisfaction [

13,

15], and maternal absenteeism from child illlness (due to the health benefits conferred by breastmilk) [

14].

In one record, a dose-dependent association was found between the number of services provided and the rates of exclusive breastfeeding [

16]. Interestingly, another record found that despite existing policies and programmes for breastfeeding support, depending on socio-economic status and workplace settings women were more or less aware of the programmes and subjectively perceived different levels of support [

15]. For instance, women within the service industry in the United States reported lower levels of perceived breastfeeding support from their employer [

15]. Finally, one record also reported decreased premature breastfeeding cessation upon returning to work as a result of breastfeeding support initiatives [

13].

3.2.5. Records including health checks and counselling combined with nutrition education interventions

Eight records assessed workforce nutrition programmes that included health checks and counselling and nutrition education in combination [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24], and sometimes as part of broader employee health programmes comprising other components (e.g., physical activity, smoking cessation, alcohol consumption). All seven records which assessed nutrition and/or health outcomes (e.g., dietary behaviors, weight loss, BMI, blood pressure, cholesterol, A1C) included studies conducted in HICs [

17,

18,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24], while only one record assessing business outcomes (absenteeism, productivity and work ability) included both studies in HICs and UMICs [

19]. Two records focused on interventions aimed at preventing and managing diabetes among (pre-)diabetic workers [

17,

21]; while all other records assessed non-targeted programmes (i.e., directed at the general worker population) mostly focused on overweight/obesity, weight management, and/or body composition.

Overall, the evidence shows mixed results with four records finding mostly positive outcomes [

17,

21,

22,

23], and four finding inconclusive results or no effect [

18,

19,

20,

24]. Of note, both records focusing on diabetes prevention and management reported positive results [

17,

21]. The mixed findings might be partially attributed to the wide variation in programme duration (from 1 day up to 8 years), methodology, and outcome measurements across studies. Shorter programmes seemed more effective than longer ones [

19,

20,

22]; and personalized, targeted interventions comprising a counselling component also showed higher effectiveness [

19,

22,

23]. Additional elements contributing to greater effectiveness were healthy food environments, which enabled longer-term weight loss [

22]; self-efficacy, which improved participation levels [

21]; direct interaction with health or nutrition professionals [

23]; the use of motivational theory [

23]; and the creation of content relevant to workers’ needs [

23].

In terms of business outcomes, results were inconclusive as only about a quarter of analyzed studies found positive effects on absenteeism, productivity, and work ability. Among the few interventions which reported positive outcomes, about half were targeted

1 at overweight/obese employees and those exhibiting high rates of sickness absences [

19].

3.2.6. Records including access to healthy food combined with nutrition education interventions

Two systematic reviews analyzed studies comprising both access to healthy food and nutrition education interventions. One record covered multiple HICs and an UMIC [

25], while the other only included HICs [

26]. Both records included studies of moderate to low quality, showing positive results on intake of fruits and vegetables, although of a small magnitude and with limited evidence of sustained impact over the longer-term [

25,

26]. The authors of the two systematic reviews conclude that the effects of workforce nutrition interventions would be more evident if programmes adhered to higher quality standards and studies used more rigorous methodologies [

25,

26].

3.2.7. Records including access to healthy food, health checks and counselling, and nutrition education interventions combined

Eight records assessed workforce nutrition programmes that included access to healthy food, health checks and counselling, and nutrition education in combination [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. In three of these records the nutrition component was embedded in comprehensive employee health programmes including other elements such as physical activity, smoking cessation, and alcohol consumption [

25,

31,

32]; while in the other five records, the employee programmes focused solely on nutrition and physical activity [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32].

Of the eight records, only two included studies conducted in LMICs or UMICs [

33,

34]. Four records assessed both nutrition and/or health and business outcomes [

28,

31,

33,

34]; two assessed only business outcomes [

29,

32]; and two only nutrition and/or health outcomes [

27,

30]. Nutrition and health outcomes measured included: dietary behaviors (e.g., intakes of fat, fruits and vegetables, sweetened beverages, water), body weight, BMI, body composition, cholesterol, blood pressure, triglycerides, CVD risk, nutrition and health knowledge. Business outcomes comprised: absenteeism, presenteeism, productivity, compensation claims, cumulated days with fever, medical costs, and health expenses.

Most records showed positive effects on at least one nutrition and/or health outcome [

28,

30,

31,

34], especially on dietary behaviors. In addition, most records reported at least some positive business outcomes [

28,

29,

31,

34], with one systematic review mentioning that all included studies found positive results [

31]. However, two records found inconclusive or mixed results [

32], [

33]. Overall, individualized counselling, environmental modifications (e.g., menu changes, larger offering and/or strategic positioning of healthier alternatives, calorie labelling, price discounts on healthy foods, portion size control), and targeted interventions were often mentioned as elements leading to increased effectiveness of workplace nutrition programmes [

27,

29,

34]. Interestingly, regarding programme duration, one record concluded that continuous programming is important to ensure sustained results, as positive outcomes were lost over the longer-term [

31]. Finally, two records mentioned that available evidence is limited and of low quality [

32,

33]. For instance, one systematic review assessing business outcomes, found positive financial returns in non-randomized studies only, whereas studies using stronger analytical methods (randomized controlled trials) reported negative financial returns [

32].

4. Discussion

This review assessed the impact of workplace nutrition programmes on nutrition, health and business outcomes based on existing high-strength-of-evidence literature. Two-thirds of identified records included experiences exclusively from high-income countries, and most of them evaluated nutrition and/or health outcomes, while only about half assessed business outcomes.

One of the key findings of this review is that workforce nutrition programmes which were comprehensive and/or targeted specific categories of workers were more likely to be effective on nutrition and/or health outcomes. Indeed, the majority of records which reviewed comprehensive workforce nutrition programmes (including access to healthy food, health checks and counselling, and nutrition education) – sometimes embedded in broader employee wellbeing programmes – showed positive results [

28,

29,

30,

31,

34], which was not the case for programmes based on one pillar only (except breastfeeding support interventions). Targeted interventions for high-risk groups (e.g., overweight/obese, or (pre-)diabetic employees) also generally led to positive nutrition, health, and business outcomes [

17,

19,

21,

27,

29,

34]. Within targeted programmes, individualized counselling and environmental modifications were often mentioned as the most effective components driving nutrition and health outcomes [

27,

29,

34].

When looking at business outcomes the evidence suggests that breastfeeding support programmes, and health checks and counselling interventions showed the most conclusive positive results [

13,

14,

15,

29,

34]. Overall, there is a lack of evidence on the business case for access to healthy food and nutrition education, although when included in comprehensive programmes they contribute to positive business outcomes [

28,

29,

31,

34]. This does not necessarily imply the ineffectiveness of stand-alone access to healthy food or nutrition education interventions on business outcomes, as it might be (at least partially) due to a variety of factors related to insufficient research, study quality, including methodological rigor, choice of outcomes, and time at which they were assessed.

Most studies assessed outcomes only in the short- to medium-term (up to 6 months), while less is known about longer-term effects. In general, shorter programmes seemed more effective than longer ones lasting at least one year [

19,

20,

23]. Although this finding is counterintuitive, we hypothesize that there may be two possible explanations for this: (i) the effects of social and behavior change programmes tend to wane over time as participants lose their initial excitement over the novelty of the intervention and become less engaged; and (ii) there is likely a bias in favour of shorter interventions, as the evidence on longer-term programmes is limited. For the reasons above we suggest that longer-term programmes are needed to maintain impact over time, however, better strategies to ensure continued participation and active engagement are needed, as well as more and higher quality evidence on their effectiveness..

Within the individual pillars themselves, specific elements seemed to be most effective and emerged across multiple studies. First, for access to healthy food, free, discounted or otherwise subsidized provision was particularly effective. Environmental modifications towards healthier food environments also had high impact. Moreover, access to healthy food interventions always resulted in positive outcomes when health checks and counselling components were added [

28,

30,

31,

34].

For nutrition education, overall evidence is scarce, and showing mixed and inconclusive results for stand-alone nutrition education interventions [

11,

12]. Most programmes include elements of nutrition education but usually not as a stand-alone component; and within comprehensive programmes, studies did not highlight nutrition education as one of the most effective components. However, methodologies, outcome measurements, and programme duration for nutrition education varied greatly, which might have contributed to inconclusive results. Most studies stress the importance of individualized counselling and not necessarily mass campaigns or similar educational approaches. Nutrition education as an accompanying component to access to healthy food or health checks and counselling interventions may be useful to reinforce and inform workers on relevant nutrition messages.

For health checks (and counselling), no records analyzed this pillar alone, as almost always some form of information is exchanged following health checks and this is often characterized as nutrition education. When in combination with nutrition education, results were mixed overall, with the exception of targeted interventions for diabetes prevention and management, where mostly positive results were found [

17,

21].

For breastfeeding support, the evidence for effectiveness is positive and consistent. All records found positive impacts on breastfeeding exclusivity and/or duration and – where business outcomes were assessed – job satisfaction and maternal absenteeism [

13,

14,

15,

16]. In addition, the more support services provided (e.g., breastfeeding rooms, breaks, pumps, counselling), the better the outcomes [

13,

16]. Of note, breastfeeding support programmes assessed were never seen as part of broader workplace wellness programmes, but rather often implemented to comply with national labour policy regulations. This is a missed opportunity by employers to communicate the benefits of breastfeeding for working mothers and their children, to the advantage of both workers and employers themselves.

4.1. Identified literature gaps and recommendations for programmes and research

We identified several gaps in the existing high-strength-of-evidence literature. First, there was a great deal of heterogeneity in the nutrition, health, and business outcome measures, as well as the ways in which programmes were designed, implemented, and evaluated. This heterogeneity made it difficult to draw conclusions on impact of workforce nutrition programmes. Workforce nutrition is a fairly nascent theme in the literature, therefore, further research is needed with consistent delineation of intervention types (e.g., based on the four pillar or other existing framework), comparable methods and outcome measures. Furthermore, increasingly standardized packages of evidence-based programme elements, linked to positive outcomes, will be helpful in generalizing findings on impact.

There was also very limited evidence on business outcomes generated from workforce nutrition programmes, which was consistent across all pillars. This finding is aligned with the broader literature [

3,

35,

36]. Therefore, further investments on studies that assess return on investment or productivity outcomes would be helpful to inform employers as they prioritize worker benefits. In particular, future research could investigate the most effective workforce nutrition programme components for positive business outcomes, if any.

In addition, few of the included records provided evidence on workforce nutrition programmes implemented in LMICs, or among low-wage workers (even in HICs), which is consistent with other findings [

37]. Such evidence would also serve to inform larger companies when considering extending programmes into their supply chains. Thus, there is a need for more rigorous studies to be conducted in LMICs and low-wage worker settings.

Moreover, most of the records reviewed only assessed programmes of short-term duration (from 1 day up to 3 months), with variable – if any – follow-up. Llonger-term studies are needed to evaluate sustainability of obtained results over time.

Finally, there were no studies including all four pillars, but given the benefits of comprehensive programmes, it is likely further synergies may be found. Company strategies that aim to improve broader worker health should consider comprehensive programmes comprising all four nutrition pillars, as well as more holistic well-being interventions (e.g., physical activity, mental health, smoking cessation).

4.2. Study limitations

This literature review has some limitations, which are summarized below:

It does not include worksite physical activity interventions, as they are not part of the selected framework for workforce nutrition programmes. In addition, physical activity (unlike nutrition) may not be relevant to all workplace contexts, but rather to work settings where overweight/obesity and NCD prevalence are high. However, since nutrition and physical activity are correlated and often share the same outcome measures (e.g., body weight, BMI, body composition, biomedical indicators for NCD risk), future research could consider the contribution of physical activity interventions to nutrition, health, and business outcomes resulting from workforce nutrition programmes (where relevant). Similarly, in workplace contexts where underweight and micronutrient deficiencies (e.g., iron deficiency anemia) are the most common forms of malnutrition, research could consider complementary interventions to improve food safety and water, sanitation, and hygiene conditions (WASH).

The search strategy did not surface any literature related to more informal work sectors (e.g., agriculture), which are more likely to be covered under evidence from community nutrition and development programmes. Future research could expand on this literature review to include less formal work settings, so as to provide useful insights to employers and other actors engaged in supply chains.

Most of the evidence on the impact of access to healthy food, nutrition education, and health checks and counselling interventions came from comprehensive employee health programmes. Therefore, it was difficult to assess the contribution of each individual pillar independently (except for breastfeeding support interventions). However, in many of the studies on comprehensive programmes, the authors highlighted the most effective components, and, overall, there was consensus across studies.

The choice to only include high-strength-of-evidence literature allowed to draw more reliable conclusions to inform research, policy and programmes; however, it led to omitting a large volume of literature from LMICs and low-wage worker settings, which – although less reliable – may provide useful insights for programmes and policy in those contexts.

5. Conclusions

Workforce nutrition programmes can contribute to addressing poor nutrition and reducing the prevalence of diet-related NCDs [

38]. This is even more true when nutrition programmes are part and parcel of broader employee health and well-being interventions. Workforce nutrition programmes should be viewed as an important tool to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – not just SDG2 (“zero hunger”), but more broadly all SDGs related to global health and economic and social development [

39]. They can also represent an important contribution of the private sector as the dominant employer of global workforces. Therefore, policymakers should consider incentives for employers to include workforce nutrition programmes as part of labor benefits.

The recent development of the Workforce Nutrition Alliance and the commitments made by many large employers under the Nutrition for Growth Summit in 2021, suggest an increasing interest in nutrition programming for employees. As programs expand, better quality evidence – on both nutrition and health, and business outcomes – will be necessary. More rigorous studies and more homogenous approaches and measures will help assess the real impact of workforce nutrition programmes and strengthen the case for investments from both public and private sectors.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. Data Charting Form 1: Article details and general information; Data Charting Form 2: Key aspects of interest to this review.

Author Contributions

C.N.D and F.O. equally contributed to conceptualization, methodology, analysis, and writing of the original draft.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Geneviève Stone and Mduduzi Mbuya for reviewing and providing valuable feedback on previous versions of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- G. A. Stevens et al., ‘Micronutrient deficiencies among preschool-aged children and women of reproductive age worldwide: a pooled analysis of individual-level data from population-representative surveys’, The Lancet Global Health, vol. 10, no. 11, pp. e1590–e1599, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Afshin et al., ‘Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017’, The Lancet, vol. 0, no. 0, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Chatham house, ‘The Business case for investment in nutrition’. 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/07-08-business-case-investment-nutrition-wellesley-et-al.pdf.

- C. Wanjek, Food at work: Workplace solutions for malnutrition, obesity and chronic diseases. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Office, 2005.

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO, The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022. Repurposing food and agricultural policies to make healthy diets more affordable. Rome, Italy: FAO, 2022. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- Workforce Nutrition Alliance, ‘Our pillars: Four themes for enhancing workforce nutrition’. http://www.wnatest.lucidleaps.com/about/ (accessed Dec. 14, 2022).

- World Health Organization (WHO), ‘Health Topics: Breastfeeding’. https://www.who.int/health-topics/breastfeeding (accessed Dec. 14, 2022).

- Cochrane, ‘Cochrane. Trusted evidence. Informed decisions. Better health.’ https://www.cochrane.org/welcome (accessed Dec. 14, 2022).

- R. Feuerstein-Simon, R. Dupuis, R. Schumacher, and C. C. Cannuscio, ‘A Randomized Trial to Encourage Healthy Eating Through Workplace Delivery of Fresh Food’, Am J Health Promot, vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 269–276, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Sawada, K. Wada, S. Shahrook, E. Ota, Y. Takemi, and R. Mori, ‘Social marketing including financial incentive programs at worksite cafeterias for preventing obesity: a systematic review’, Syst Rev, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 66, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. Hassani, R. Amani, M. H. Haghighizadeh, and M. Araban, ‘A priority oriented nutrition education program to improve nutritional and cardiometabolic status in the workplace: a randomized field trial’, Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 2, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Vasiljevic et al., ‘Impact of calorie labelling in worksite cafeterias: a stepped wedge randomised controlled pilot trial’, Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 41, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Dinour and J. M. Szaro, ‘Employer-Based Programs to Support Breastfeeding Among Working Mothers: A Systematic Review’, Breastfeed Med, vol. 12, pp. 131–141, 2017. [CrossRef]

- X. Tang et al., ‘Workplace programmes for supporting breast-feeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, Public Health Nutr, vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 1501–1513, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. J. Taylor, V. C. Scott, and C. Danielle Connor, ‘Perceptions, Experiences, and Outcomes of Lactation Support in the Workplace: A Systematic Literature Review’, J Hum Lact, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 657–672, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Kim, J. C. Shin, and S. M. Donovan, ‘Effectiveness of Workplace Lactation Interventions on Breastfeeding Outcomes in the United States: An Updated Systematic Review’, J Hum Lact, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 100–113, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. K. Miller, K. R. Weinhold, and H. N. Nagaraja, ‘Impact of a Worksite Diabetes Prevention Intervention on Diet Quality and Social Cognitive Influences of Health Behavior: A Randomized Controlled Trial’, J Nutr Educ Behav, vol. 48, no. 3, pp. 160-169.e1, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Z. Song and K. Baicker, ‘Effect of a Workplace Wellness Program on Employee Health and Economic Outcomes: A Randomized Clinical Trial’, JAMA, vol. 321, no. 15, pp. 1491–1501, 16 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Tarro, E. Llauradó, G. Ulldemolins, P. Hermoso, and R. Solà, ‘Effectiveness of Workplace Interventions for Improving Absenteeism, Productivity, and Work Ability of Employees: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials’, Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 17, no. 6, 14 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. K. Weerasekara, S. B. Roberts, M. A. Kahn, A. E. LaVertu, B. Hoffman, and S. K. Das, ‘Effectiveness of Workplace Weight Management Interventions: a Systematic Review’, Curr Obes Rep, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 298–306, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Brown, A. A. García, J. A. Zuñiga, and K. A. Lewis, ‘Effectiveness of workplace diabetes prevention programs: A systematic review of the evidence’, Patient Educ Couns, vol. 101, no. 6, pp. 1036–1050, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S.-H. Park and S.-Y. Kim, ‘Effectiveness of worksite-based dietary interventions on employees’ obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, Nutr Res Pract, vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 399–409, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- V. Sandercock and J. Andrade, ‘Evaluation of Worksite Wellness Nutrition and Physical Activity Programs and Their Subsequent Impact on Participants’ Body Composition’, Journal of Obesity, vol. 2018, p. e1035871, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Torquati, T. Pavey, T. Kolbe-Alexander, and M. Leveritt, ‘Promoting Diet and Physical Activity in Nurses: A Systematic Review’, Am J Health Promot, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 19–27, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. Geaney, C. Kelly, B. A. Greiner, J. M. Harrington, I. J. Perry, and P. Beirne, ‘The effectiveness of workplace dietary modification interventions: a systematic review’, Prev Med, vol. 57, no. 5, pp. 438–447, Nov. 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. Maes et al., ‘Effectiveness of workplace interventions in Europe promoting healthy eating: a systematic review’, Eur J Public Health, vol. 22, no. 5, pp. 677–683, Oct. 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. J. W. Robroek et al., ‘Socio-economic inequalities in the effectiveness of workplace health promotion programmes on body mass index: An individual participant data meta-analysis’, Obes Rev, vol. 21, no. 11, p. e13101, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. M. van Dongen et al., ‘A systematic review of the cost-effectiveness of worksite physical activity and/or nutrition programs’, Scand J Work Environ Health, vol. 38, no. 5, pp. 393–408, Sep. 2012. [CrossRef]

- A. Grimani, E. Aboagye, and L. Kwak, ‘The effectiveness of workplace nutrition and physical activity interventions in improving productivity, work performance and workability: a systematic review’, BMC Public Health, vol. 19, no. 1, p. 1676, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Plotnikoff, C. E. Collins, R. Williams, J. Germov, and R. Callister, ‘Effectiveness of interventions targeting health behaviors in university and college staff: a systematic review’, Am J Health Promot, vol. 29, no. 5, pp. e169-187, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. D. Lassen et al., ‘The impact of worksite interventions promoting healthier food and/or physical activity habits among employees working “around the clock” hours: a systematic review’, Food Nutr Res, vol. 62, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. M. van Dongen et al., ‘Systematic review on the financial return of worksite health promotion programmes aimed at improving nutrition and/or increasing physical activity’, Obes Rev, vol. 12, no. 12, pp. 1031–1049, Dec. 2011. [CrossRef]

- L. Wolfenden et al., ‘Strategies to improve the implementation of workplace-based policies or practices targeting tobacco, alcohol, diet, physical activity and obesity’, Cochrane Database Syst Rev, vol. 11, p. CD012439, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Vargas-Martínez, M. Romero-Saldaña, and R. De Diego-Cordero, ‘Economic evaluation of workplace health promotion interventions focused on Lifestyle: Systematic review and meta-analysis’, J Adv Nurs, vol. 77, no. 9, pp. 3657–3691, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, ‘Impact of nutrition interventions and dietary nutrient density on productivity in the workplace’, Nutrition Reviews, vol. 0, no. 0, pp. 1–10, 2019.

- L. L. Berry, A. M. Mirabito, and W. B. Baun, ‘What’s the hard return on employee wellness programs?’, Harv Bus Rev, vol. 88, no. 12, pp. 104–112, 142, Dec. 2010.

- The Global Wellness Institute, ‘The Future of Wellness at Work’, 2016.

- NCD Alliance, ‘Realising the potential of workplaces to prevent and control NCDs: How public policy can encourage businesses and governments to work together to address NCDs through the workplace’. 2016. [Online]. Available: https://ncdalliance.org/sites/default/files/NCDs_%26_WorkplaceWellness_web.pdf.

- ‘UN General Assembly Resolution 70/1 (2015) - Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’. 2015. Accessed: May 25, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf.

| 1 |

We use the term “targeted” to refer to progammes which aim to reach specific groups/individuals who are affected by specific health issues (e.g., diabetes, overweight/obesity, hypertension). |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).