Submitted:

10 March 2023

Posted:

13 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

Epidemiology

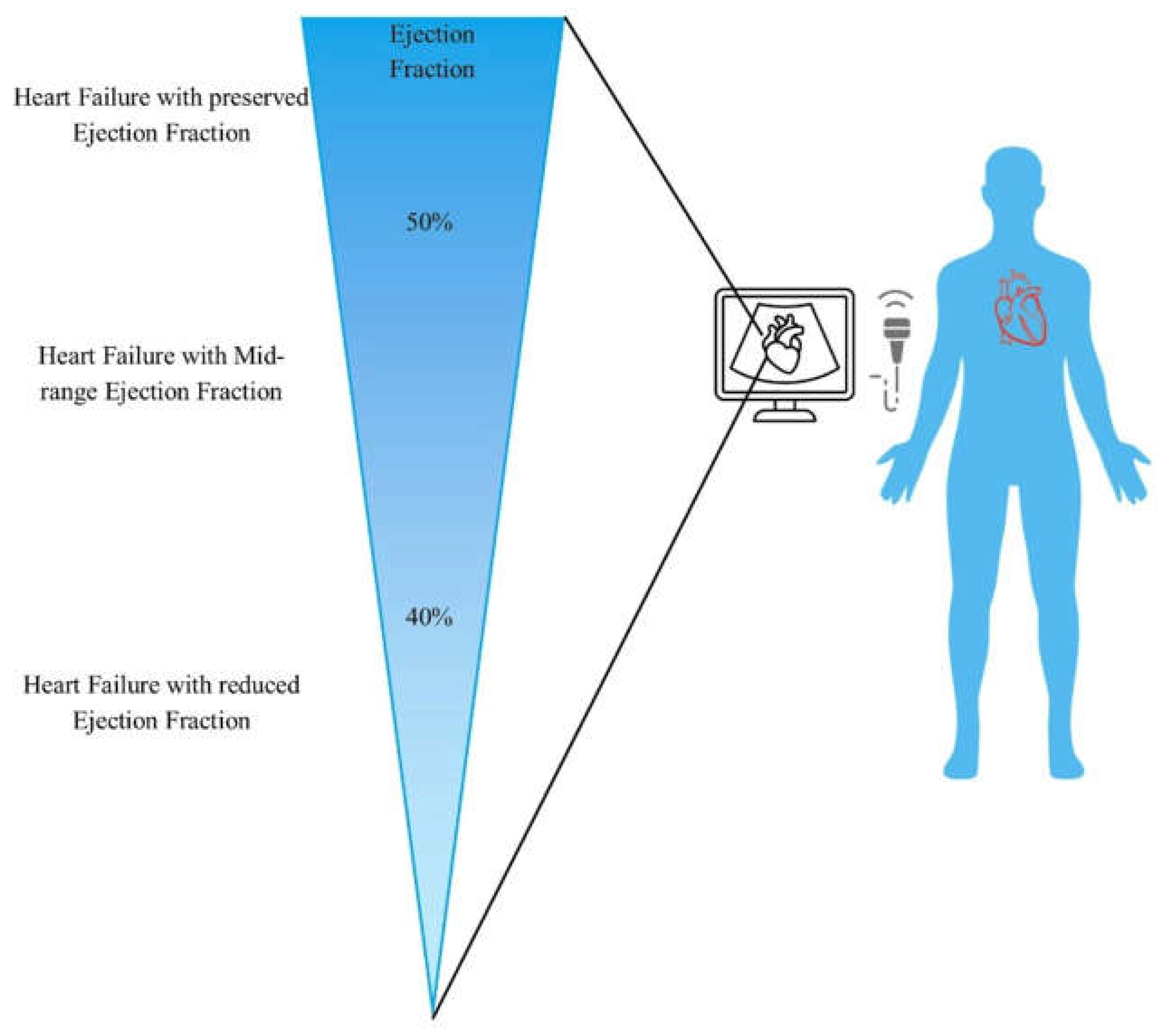

Clinical Characteristics of HFmrEF

Ischemia and Heart Failure

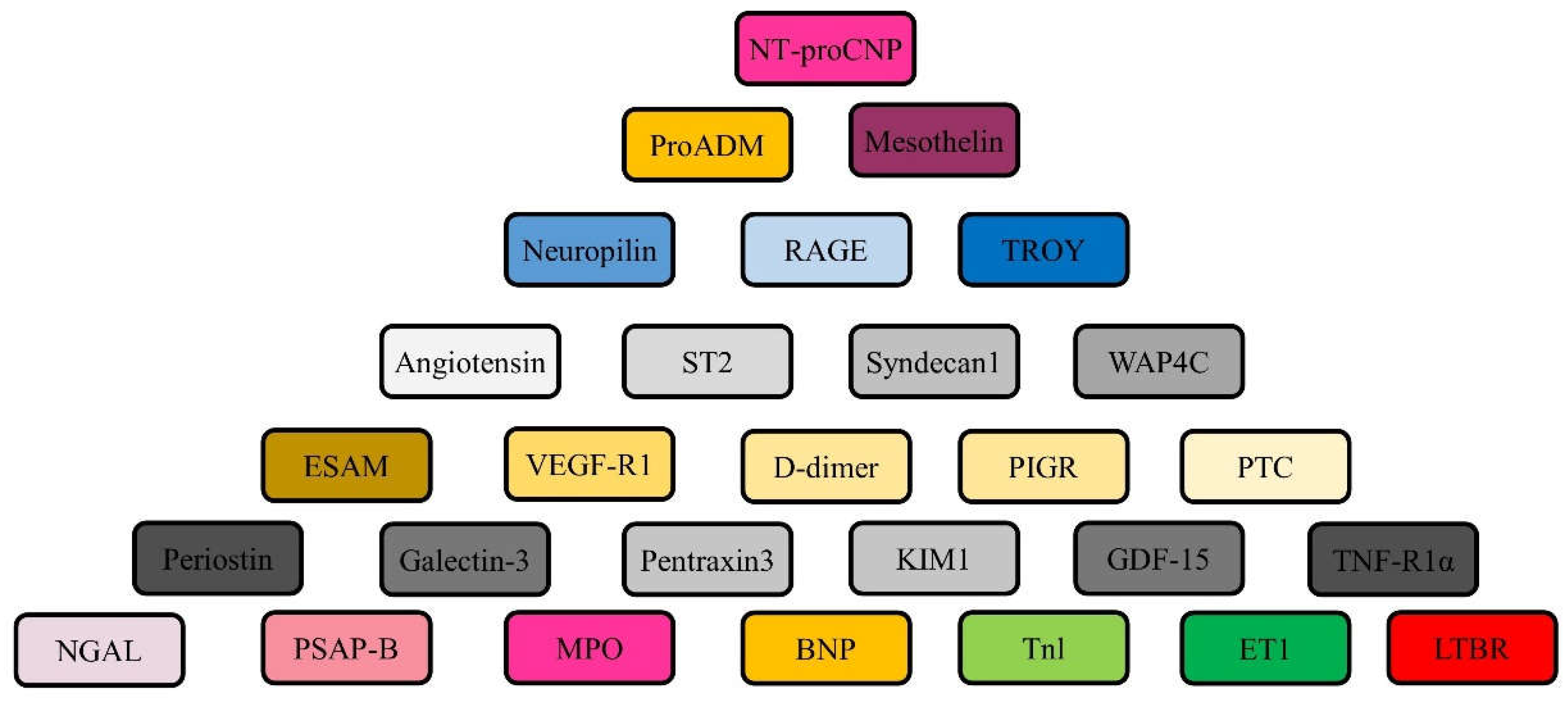

Pathophysiology of HFmrEF

Conclusive Statement

Author Contributions

Funding

Consent for publication

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Ethics approval

Consent to participate

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Conrad, N. et al. (2018) Temporal trends and patterns in heart failure incidence: a population-based study of 4 million individuals. Lancet 391, 572–580. [CrossRef]

- Jernberg, T. et al. (2011) Association between adoption of evidence-based treatment and survival for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA 305, 1677–1684. [CrossRef]

- van Riet, E. E. et al. (2016) Epidemiology of heart failure: the prevalence of heart failure and ventricular dysfunction in older adults over time. A systematic review. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 18, 242–252. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C. J. et al. (2019) Trends in survival after a diagnosis of heart failure in the United Kingdom 2000–2017: population based cohort study. BMJ 364, l223. [CrossRef]

- Yancy, C. W. et al. (2017) 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation 136, e137–e161. [CrossRef]

- Ponikowski, P. et al. (2016) 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 37, 2129–2200. [CrossRef]

- Virani, S. S. et al. (2021) Heart disease and stroke statistics — 2021 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 143, e254–e743. [CrossRef]

- Thorvaldsen, T. et al. (2016) Use of evidence-based therapy and survival in heart failure in Sweden 2003–2012. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 18, 503–511. [CrossRef]

- Ambrosy, A. P. et al. (2014) The global health and economic burden of hospitalizations for heart failure: lessons learned from hospitalized heart failure registries. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 63, 1123–1133. [CrossRef]

- Lund, L. H., et al. (2012) Association between use of renin–angiotensin system antagonists and mortality in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. JAMA 308, 2108–2117. [CrossRef]

- Lund, L. H. et al. (2017) Association between enrolment in a heart failure quality registry and subsequent mortality — a nationwide cohort study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 19,1107–1116. [CrossRef]

- Crespo-Leiro, M. G. et al. (2018) Advanced heart failure: a position statement of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 20, 1505–1535. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T. et al. (2018) Machine learning methods improve prognostication, identify clinically distinct phenotypes, and detect heterogeneity in response to therapy in a large cohort of heart failure patients. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7, e008081. [CrossRef]

- Lund, L. H. (2016) Heart failure with “mid-range” ejection fraction — new opportunities. J. Card. Fail. 22, 769–771. [CrossRef]

- Lund, L. H., et al. (2018) Is ejection fraction in heart failure a limitation or an opportunity? Eur. J. Heart Fail. 20, 431–432. [CrossRef]

- Marwick, T. H. (2018) Ejection fraction pros and cons: JACC state-of-the-art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 72, 2360–2379. [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, D. L. et al. (2020) Sotagliflozin in patients with diabetes and recent worsening heart Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 117–128. [CrossRef]

- Kapoor JR, et al. (2016) Precipitating Clinical Factors, Heart Failure Characterization, and Outcomes in Patients Hospitalized With Heart Failure With Reduced, Borderline, and Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail 4, 464–72. [CrossRef]

- Tsuji K, et al. (2017) Characterization of heart failure patients with mid-range left ventricular ejection fraction-a report from the CHART-2 Study. Eur J Heart Fail 19, 1258–69. [CrossRef]

- Chioncel O, et al. (2017) Epidemiology and one-year outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved, mid-range and reduced ejection fraction: an analysis of the ESC Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Eur J Heart Fail 19, 1574–85. [CrossRef]

- Koh AS, et al. (2017) A comprehensive population-based characterization of heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 19, 1624–34. [CrossRef]

- Bhambhani V, et al. (2018) Predictors and outcomes of heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 20, 651–9. [CrossRef]

- Lam CSP, et al. (2018) Mortality associated with heart failure with preserved vs. reduced ejection fraction in a prospective international multi-ethnic cohort study. Eur Heart J 39, 1770–80. [CrossRef]

- Rickenbacher P, et al. (2017) Heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction: a distinct clinical entity? Insights from the Trial of Intensified versus standard Medical therapy in Elderly patients with Congestive Heart Failure (TIME-CHF). Eur J Heart Fail 19, 1586–96. [CrossRef]

- Lund LH, et al. (2018) Heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction in CHARM: characteristics, outcomes and effect of candesartan across the entire ejection fraction spectrum. Eur J Heart Fail 20, 1230–9. [CrossRef]

- Lund LH. (2018) Heart Failure with Mid-range Ejection Fraction: Lessons from CHARM. Card Fail Rev 4, 70–2. [CrossRef]

- Fonarow GC, et al. (2007) Characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of patients with preserved systolic function hospitalized for heart failure: a report from the OPTIMIZE-HF Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 50, 768–77. [CrossRef]

- Sweitzer NK, et al. (2008) Comparison of clinical features and outcomes of patients hospitalized with heart failure and normal ejection fraction (>or =55%) versus those with mildly reduced (40% to 55%) and moderately to severely reduced (<40%) fractions. Am J Cardiol 101, 1151–6. [CrossRef]

- Shah KS, et al. (2017) Heart Failure With Preserved, Borderline, and Reduced Ejection Fraction: 5-Year Outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol 70, 2476–86. [CrossRef]

- Kalogeropoulos AP, et al. (2016) Characteristics and Outcomes of Adult Outpatients With Heart Failure and Improved or Recovered Ejection Fraction. JAMA Cardiol 1, 510–8. [CrossRef]

- Stolfo D, et al. (2019) Sex-Based Differences in Heart Failure Across the Ejection Fraction Spectrum: Phenotyping, and Prognostic and Therapeutic Implications. JACC Heart Fail 7, 505–15. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim NE, et al. (2019) Heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction: characterization of patients from the PINNACLE Registry(R). ESC Heart Fail 6, 784–92. [CrossRef]

- Vedin O, et al. (2017) Significance of Ischemic Heart Disease in Patients With Heart Failure and Preserved, Midrange, and Reduced Ejection Fraction: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Circ Heart Fail 10. [CrossRef]

- Lee DS, et al. (2009) Relation of disease pathogenesis and risk factors to heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction: insights from the Framingham Heart Study of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation 119, 3070–7. [CrossRef]

- Borlaug BA,et al. (2011) Diastolic and systolic heart failure are distinct phenotypes within the heart failure spectrum. Circulation 123, 2006–13. [CrossRef]

- Dunlay et al. (2012) Longitudinal changes in ejection fraction in heart failure patients with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. Circ. Heart Fail. 5, 720–726. [CrossRef]

- MERIT-HF Study Group. (1999) Effect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic heart failure: Metoprolol CR/XL randomised intervention trial in congestive heart failure (MERIT-HF). Lancet. 353, 2001–7.

- Poole-Wilson PA, et al. (2003) Comparison of carvedilol and metoprolol on clinical outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure in the Carvedilol or Metoprolol European trial (COMET): randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 362, 7–13. [CrossRef]

- Investigators S, et al. (1991) Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 325, 293–302. [CrossRef]

- Consensus Trial Study Group. (1987) Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure. Results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS). N Engl J Med. 316, 1429–35. [CrossRef]

- Granger CB, et al. (2003) Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function intolerant to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARMalternative trial. Lancet. 362, 772–6. [CrossRef]

- Zannad F, et al. (2011) Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N Engl J Med. 364, 11–21. [CrossRef]

- McMurray JJ, et al. (2014) Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 371, 993–1004. [CrossRef]

- Swedberg K, et al. (2010) Ivabradine and outcomes in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): a randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 376, 875–85. [CrossRef]

- Tromp J, et al. (2017) Biomarker profiles of acute heart failure patients with a mid-range ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 5, 507–17. [CrossRef]

- Gohar A, et al. (2017) The prognostic value of highly sensitive cardiac troponin assays for adverse events in men and women with stable heart failure and a preserved vs. reduced ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 19, 1638–47. [CrossRef]

- Vergaro G, et al. (2019) Sympathetic and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activation in heart failure with preserved, mid-range and reduced ejection fraction. Int J Cardiol. 296, 91–7. [CrossRef]

- Pugliese NR, et al. (2019) Value of combined cardiopulmonary and echocardiography stress test to characterize the haemodynamic and metabolic responses of patients with heart failure and mid-range ejection fraction. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 20, 828–36. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).