Submitted:

10 March 2023

Posted:

13 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

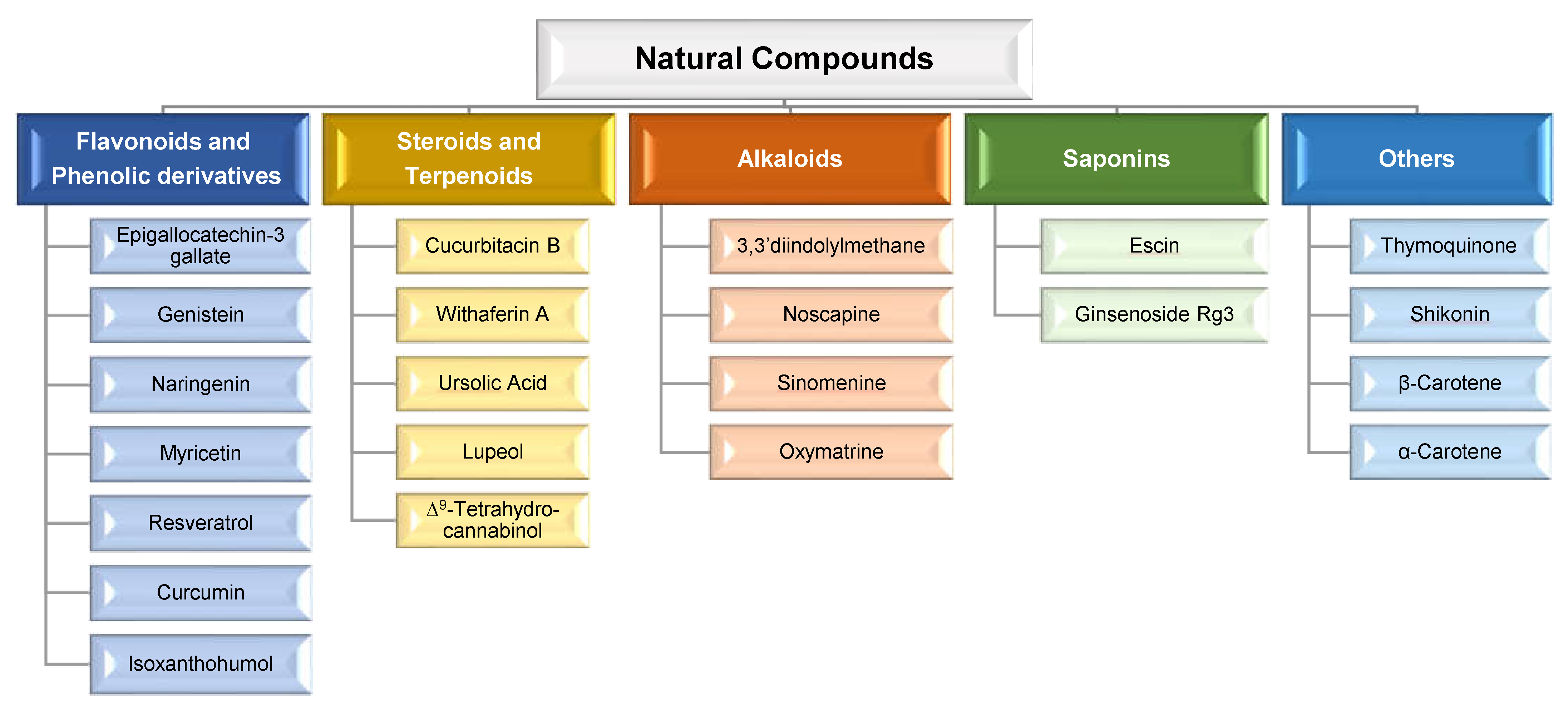

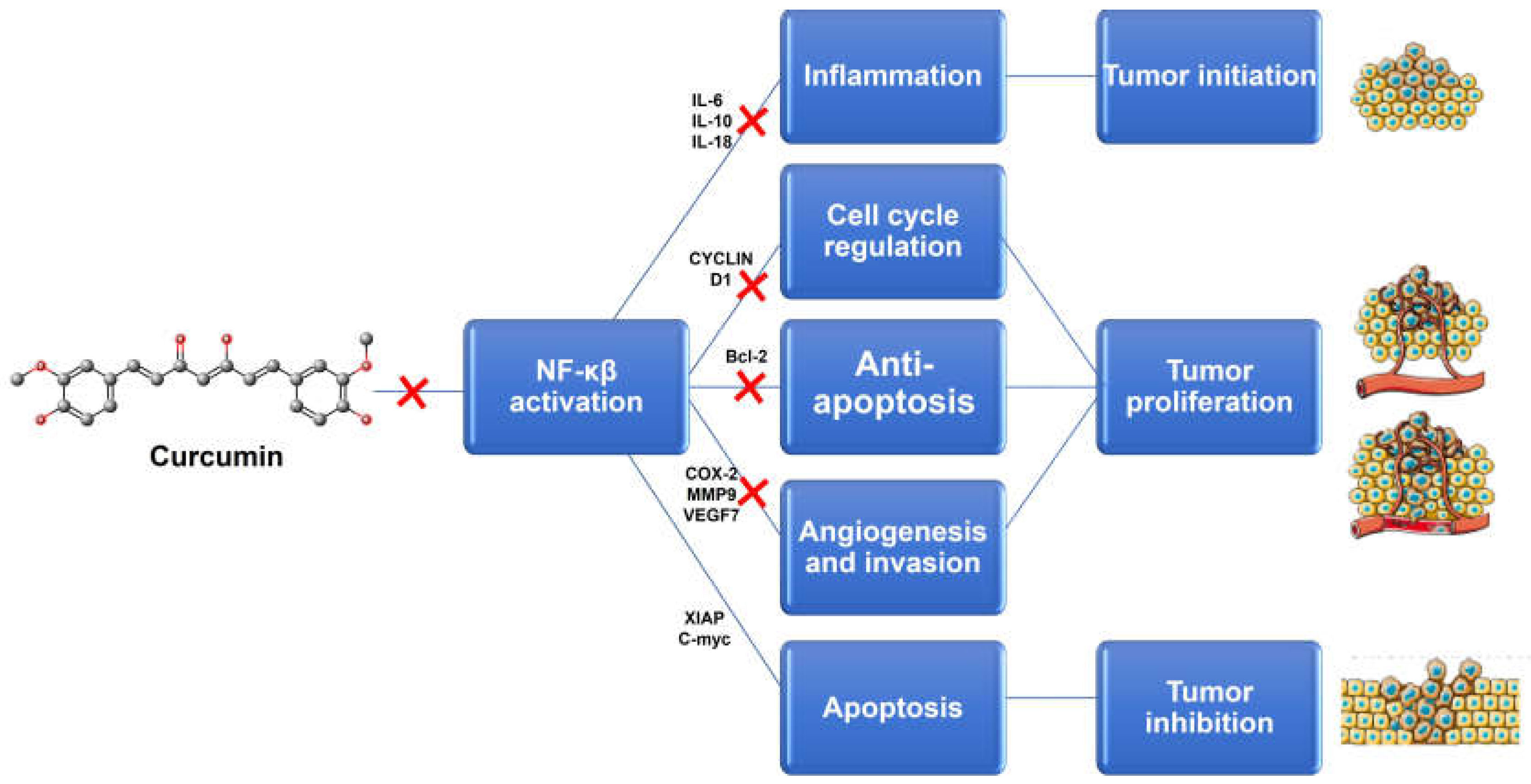

2. Natural Compounds: Advantages of Combination Therapy in Cancer

2.1. Overcoming Multidrug Resistance

2.2. Synergistic, Additive and Potentiation Effects

2.3. Reducing the Side Effects

2.4. Decreasing the Effective Chemotherapy Dose

3. Lipid-based Nanocarriers for the Co-delivery of Natural Compounds and other Therapeutic agents

3.1. Co-delivery of natural compounds and chemotherapeutics

3.2. Co-delivery of natural compounds and nucleic acids

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sanchez-Moreno, P.; Ortega-Vinuesa, J.L.; Peula-Garcia, J.M.; Marchal, J.A.; Boulaiz, H. Smart Drug-Delivery Systems for Cancer Nanotherapy. Curr Drug Targets 2018, 19, 339-359. [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Guo, F.; Xu, H.; Liang, W.; Wang, C.; Yang, X.D. Combination Therapy using Co-encapsulated Resveratrol and Paclitaxel in Liposomes for Drug Resistance Reversal in Breast Cancer Cells in vivo. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 22390. [CrossRef]

- Mozafari, M.R.; Pardakhty, A.; Azarmi, S.; Jazayeri, J.A.; Nokhodchi, A.; Omri, A. Role of nanocarrier systems in cancer nanotherapy. J Liposome Res 2009, 19, 310-321. [CrossRef]

- Boyle, P.; Levin, B. World cancer report 2008; IARC Press, International Agency for Research on Cancer: 2008.

- Qi, S.S.; Sun, J.H.; Yu, H.H.; Yu, S.Q. Co-delivery nanoparticles of anti-cancer drugs for improving chemotherapy efficacy. Drug Deliv 2017, 24, 1909-1926. [CrossRef]

- Leng, F.; Liu, F.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Tian, W. Strategies on Nanodiagnostics and Nanotherapies of the Three Common Cancers. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2018, 8, 202. [CrossRef]

- Senapati, S.; Mahanta, A.K.; Kumar, S.; Maiti, P. Controlled drug delivery vehicles for cancer treatment and their performance. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2018, 3, 7. [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, M.; Guschel, M.; Bernd, A.; Bereiter-Hahn, J.; Kaufmann, R.; Tandi, C.; Wiig, H.; Kippenberger, S. Lowering of tumor interstitial fluid pressure reduces tumor cell proliferation in a xenograft tumor model. Neoplasia 2006, 8, 89-95. [CrossRef]

- Tefas, L.R.; Sylvester, B.; Tomuta, I.; Sesarman, A.; Licarete, E.; Banciu, M.; Porfire, A. Development of antiproliferative long-circulating liposomes co-encapsulating doxorubicin and curcumin, through the use of a quality-by-design approach. Drug Des Devel Ther 2017, 11, 1605-1621. [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Wang, X.; Nie, S.; Chen, Z.G.; Shin, D.M. Therapeutic nanoparticles for drug delivery in cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2008, 14, 1310-1316. [CrossRef]

- Jain, T.K.; Morales, M.A.; Sahoo, S.K.; Leslie-Pelecky, D.L.; Labhasetwar, V. Iron oxide nanoparticles for sustained delivery of anticancer agents. Mol Pharm 2005, 2, 194-205. [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, M.M. Mechanisms of Cancer Drug Resistance. Annual Review of Medicine 2002, 53, 615-627. [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, K.; Katayama, K.; Mitsuhashi, J.; Sugimoto, Y. Functions of the breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) in chemotherapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2009, 61, 26-33. [CrossRef]

- Al-Lazikani, B.; Banerji, U.; Workman, P. Combinatorial drug therapy for cancer in the post-genomic era. Nat Biotechnol 2012, 30, 679-692. [CrossRef]

- Bahadur, K.C.R.; Xu, P. Multicompartment intracellular self-expanding nanogel for targeted delivery of drug cocktail. Adv Mater 2012, 24, 6479-6483. [CrossRef]

- DeVita, V.T., Jr.; Young, R.C.; Canellos, G.P. Combination versus single agent chemotherapy: a review of the basis for selection of drug treatment of cancer. Cancer 1975, 35, 98-110. [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.M.; Zhang, L. Nanoparticle-based combination therapy toward overcoming drug resistance in cancer. Biochem Pharmacol 2012, 83, 1104-1111. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Waxman, D.J. Combination of antiangiogenesis with chemotherapy for more effective cancer treatment. Mol Cancer Ther 2008, 7, 3670-3684. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, M.; Chen, C.; Fan, A.; Kong, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y. On-demand combinational delivery of curcumin and doxorubicin via a pH-labile micellar nanocarrier. Int J Pharm 2015, 495, 572-578. [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Zhuang, J.; Lu, Y.; Dong, X.; Zhao, W.; Wu, W. In vivo fate of lipid-based nanoparticles. Drug Discov Today 2017, 22, 166-172. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-P.; Ohnuma, S.; Ambudkar, S.V. Discovering natural product modulators to overcome multidrug resistance in cancer chemotherapy. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 2011, 12, 609-620. [CrossRef]

- Kallifatidis, G.; Hoy, J.J.; Lokeshwar, B.L. Bioactive natural products for chemoprevention and treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Semin Cancer Biol 2016, 40-41, 160-169. [CrossRef]

- Kapse-Mistry, S.; Govender, T.; Srivastava, R.; Yergeri, M. Nanodrug delivery in reversing multidrug resistance in cancer cells. Front Pharmacol 2014, 5, 159-159. [CrossRef]

- Creixell, M.; Peppas, N.A. Co-delivery of siRNA and therapeutic agents using nanocarriers to overcome cancer resistance. Nano Today 2012, 7, 367-379. [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Mai, W.X.; Zhang, H.; Xue, M.; Xia, T.; Lin, S.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Ji, Z.; Zink, J.I.; et al. Codelivery of an optimal drug/siRNA combination using mesoporous silica nanoparticles to overcome drug resistance in breast cancer in vitro and in vivo. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 994-1005. [CrossRef]

- Amani, A.; Alizadeh, M.R.; Yaghoubi, H.; Nohtani, M. Novel multi-targeted nanoparticles for targeted co-delivery of nucleic acid and chemotherapeutic agents to breast cancer tissues. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2021, 118, 111494. [CrossRef]

- Ali Abdalla, Y.O.; Subramaniam, B.; Nyamathulla, S.; Shamsuddin, N.; Arshad, N.M.; Mun, K.S.; Awang, K.; Nagoor, N.H. Natural Products for Cancer Therapy: A Review of Their Mechanism of Actions and Toxicity in the Past Decade. Journal of Tropical Medicine 2022, 2022, 5794350. [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-R.; Chang, C.-H.; Hsu, C.-F.; Tsai, M.-J.; Cheng, H.; Leong, M.K.; Sung, P.-J.; Chen, J.-C.; Weng, C.-F. Natural compounds as potential adjuvants to cancer therapy: Preclinical evidence. British Journal of Pharmacology 2020, 177, 1409-1423. [CrossRef]

- Hashem, S.; Ali, T.A.; Akhtar, S.; Nisar, S.; Sageena, G.; Ali, S.; Al-Mannai, S.; Therachiyil, L.; Mir, R.; Elfaki, I.; et al. Targeting cancer signaling pathways by natural products: Exploring promising anti-cancer agents. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2022, 150, 113054. [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Park, M.N.; Noh, S.; Kang, S.Y.; Kim, B. Review of Natural Compounds for the Management and Prevention of Lymphoma. Processes 2020, 8, 1164.

- Sauter, E.R. Cancer prevention and treatment using combination therapy with natural compounds. Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology 2020, 13, 265-285. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Feng, J.; Liu, W.; Wen, C.; Wu, Y.; Liao, Q.; Zou, L.; Sui, X.; Xie, T.; Zhang, J.; et al. Opportunities and challenges for co-delivery nanomedicines based on combination of phytochemicals with chemotherapeutic drugs in cancer treatment. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2022, 188, 114445. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Sun, W.; Wang, C.; Gu, Z. Recent advances of cocktail chemotherapy by combination drug delivery systems. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2016, 98, 19-34. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Seebacher, N.; Shi, H.; Kan, Q.; Duan, Z. Novel strategies to prevent the development of multidrug resistance (MDR) in cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 84559-84571. [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, M.M.; Fojo, T.; Bates, S.E. Multidrug resistance in cancer: role of ATP-dependent transporters. Nat Rev Cancer 2002, 2, 48-58. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Chen, W.; Yang, T.; Wen, B.; Ding, D.; Keidar, M.; Tang, J.; Zhang, W. Paclitaxel and quercetin nanoparticles co-loaded in microspheres to prolong retention time for pulmonary drug delivery. Int J Nanomedicine 2017, 12, 8239-8255. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, X.; Li, K.; Chen, D.; Qiao, M.; Hu, H.; Zhao, X. Co-delivery of doxorubicin and the traditional Chinese medicine quercetin using biotin–PEG2000–DSPE modified liposomes for the treatment of multidrug resistant breast cancer. RSC Advances 2016, 6, 113173-113184. [CrossRef]

- Israel, B.B.; Tilghman, S.L.; Parker-Lemieux, K.; Payton-Stewart, F. Phytochemicals: Current strategies for treating breast cancer. Oncol Lett 2018, 15, 7471-7478. [CrossRef]

- Gameiro, M.; Silva, R.; Rocha-Pereira, C.; Carmo, H.; Carvalho, F.; Bastos, M.L.; Remião, F. Cellular Models and In Vitro Assays for the Screening of modulators of P-gp, MRP1 and BCRP. Molecules 2017, 22. [CrossRef]

- Aung, T.N.; Qu, Z.; Kortschak, R.D.; Adelson, D.L. Understanding the Effectiveness of Natural Compound Mixtures in Cancer through Their Molecular Mode of Action. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Júnior, R.G.; Christiane Adrielly, A.F.; da Silva Almeida, J.R.G.; Grougnet, R.; Thiéry, V.; Picot, L. Sensitization of tumor cells to chemotherapy by natural products: A systematic review of preclinical data and molecular mechanisms. Fitoterapia 2018, 129, 383-400. [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.S.; Cho, C.W. A multifunctional lipid nanoparticle for co-delivery of paclitaxel and curcumin for targeted delivery and enhanced cytotoxicity in multidrug resistant breast cancer cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 30369-30382. [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Zhu, F.; Ma, X.; Cao, Z.; Cao, Z.W.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.X.; Chen, Y.Z. Mechanisms of drug combinations: interaction and network perspectives. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2009, 8, 111-128. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Li, G.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Yao, Q.; Xie, M. Sequential delivery of dual drugs with nanostructured lipid carriers for improving synergistic tumor treatment effect. Drug Deliv 2020, 27, 983-995. [CrossRef]

- Pardeike, J.; Hommoss, A.; Müller, R.H. Lipid nanoparticles (SLN, NLC) in cosmetic and pharmaceutical dermal products. Int J Pharm 2009, 366, 170-184. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, H.S.; Rasedee, A.; How, C.W.; Abdul, A.B.; Zeenathul, N.A.; Othman, H.H.; Saeed, M.I.; Yeap, S.K. Zerumbone-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers: preparation, characterization, and antileukemic effect. Int J Nanomedicine 2013, 8, 2769-2781. [CrossRef]

- Cosco, D.; Paolino, D.; Maiuolo, J.; Marzio, L.D.; Carafa, M.; Ventura, C.A.; Fresta, M. Ultradeformable liposomes as multidrug carrier of resveratrol and 5-fluorouracil for their topical delivery. Int J Pharm 2015, 489, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Mohan, A.; Narayanan, S.; Sethuraman, S.; Krishnan, U.M. Novel resveratrol and 5-fluorouracil coencapsulated in PEGylated nanoliposomes improve chemotherapeutic efficacy of combination against head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Biomed Res Int 2014, 2014, 424239. [CrossRef]

- Pawar, H.; Surapaneni, S.K.; Tikoo, K.; Singh, C.; Burman, R.; Gill, M.S.; Suresh, S. Folic acid functionalized long-circulating co-encapsulated docetaxel and curcumin solid lipid nanoparticles: In vitro evaluation, pharmacokinetic and biodistribution in rats. Drug Deliv 2016, 23, 1453-1468. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, J.; Pu, G.; Zhang, F.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y. Co-delivery of baicalein and doxorubicin by hyaluronic acid decorated nanostructured lipid carriers for breast cancer therapy. Drug Deliv 2016, 23, 1364-1368. [CrossRef]

- Barui, S.; Saha, S.; Mondal, G.; Haseena, S.; Chaudhuri, A. Simultaneous delivery of doxorubicin and curcumin encapsulated in liposomes of pegylated RGDK-lipopeptide to tumor vasculature. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 1643-1656. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, Q.; Li, Y.; Tang, H.; Liu, W.; Yang, X. Doxorubicin and curcumin co-delivery by lipid nanoparticles for enhanced treatment of diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2015, 93, 27-36. [CrossRef]

- Mussi, S.V.; Sawant, R.; Perche, F.; Oliveira, M.C.; Azevedo, R.B.; Ferreira, L.A.; Torchilin, V.P. Novel nanostructured lipid carrier co-loaded with doxorubicin and docosahexaenoic acid demonstrates enhanced in vitro activity and overcomes drug resistance in MCF-7/Adr cells. Pharm Res 2014, 31, 1882-1892. [CrossRef]

- Sarfraz, M.; Afzal, A.; Raza, S.M.; Bashir, S.; Madni, A.; Khan, M.W.; Ma, X.; Xiang, G. Liposomal co-delivered oleanolic acid attenuates doxorubicin-induced multi-organ toxicity in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 47136-47153. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lu, X.; Liu, Q.; Dai, Y.; Zhu, X.; Wen, Y.; Xu, J.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, D.; Chen, X.; et al. Palmitoyl ascorbate and doxorubicin co-encapsulated liposome for synergistic anticancer therapy. Eur J Pharm Sci 2017, 105, 219-229. [CrossRef]

- Minaei, A.; Sabzichi, M.; Ramezani, F.; Hamishehkar, H.; Samadi, N. Co-delivery with nano-quercetin enhances doxorubicin-mediated cytotoxicity against MCF-7 cells. Mol Biol Rep 2016, 43, 99-105. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.S.; Aryasomayajula, B.; Pattni, B.; Mussi, S.V.; Ferreira, L.A.M.; Torchilin, V.P. Solid lipid nanoparticles co-loaded with doxorubicin and alpha-tocopherol succinate are effective against drug-resistant cancer cells in monolayer and 3-D spheroid cancer cell models. Int J Pharm 2016, 512, 292-300. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Angelova, A.; Hu, F.; Garamus, V.M.; Peng, C.; Li, N.; Liu, J.; Liu, D.; Zou, A. pH Responsiveness of Hexosomes and Cubosomes for Combined Delivery of Brucea javanica Oil and Doxorubicin. Langmuir 2019, 35, 14532-14542. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Geng, D.; Liu, H.; Li, Z.; Cao, J. Co-delivery of etoposide and curcumin by lipid nanoparticulate drug delivery system for the treatment of gastric tumors. Drug Delivery 2016, 23, 3665-3673. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.; Mathur, V.; Kumar, A.; Khedgikar, V.; Teja, V.B.; Chaudhary, D.; Kushwaha, P.; Bora, H.K.; Konwar, R.; Trivedi, R.; et al. Nanoemulsion based concomitant delivery of curcumin and etoposide: impact on cross talk between prostate cancer cells and osteoblast during metastasis. J Biomed Nanotechnol 2014, 10, 3381-3391. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Su, J.; Li, Z.; Zhan, Y.; Ye, D. Hyaluronic acid-coated, prodrug-based nanostructured lipid carriers for enhanced pancreatic cancer therapy. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 2017, 43, 160-170. [CrossRef]

- Soe, Z.C.; Thapa, R.K.; Ou, W.; Gautam, M.; Nguyen, H.T.; Jin, S.G.; Ku, S.K.; Oh, K.T.; Choi, H.G.; Yong, C.S.; et al. Folate receptor-mediated celastrol and irinotecan combination delivery using liposomes for effective chemotherapy. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2018, 170, 718-728. [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Sharma, G.; Kushwah, V.; Garg, N.K.; Kesharwani, P.; Ghoshal, G.; Singh, B.; Shivhare, U.S.; Jain, S.; Katare, O.P. Methotrexate and beta-carotene loaded-lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles: a preclinical study for breast cancer. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2017, 12, 1851-1872. [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Xia, X.; Yang, Y.; Ye, J.; Dong, W.; Ma, P.; Jin, Y.; Liu, Y. Co-encapsulation of paclitaxel and baicalein in nanoemulsions to overcome multidrug resistance via oxidative stress augmentation and P-glycoprotein inhibition. Int J Pharm 2016, 513, 8-16. [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Fang, G.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zou, M.; Wang, L.; Cheng, G. Lipid-albumin nanoassemblies co-loaded with borneol and paclitaxel for intracellular drug delivery to C6 glioma cells with P-gp inhibition and its tumor targeting. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2015, 10, 363-371. [CrossRef]

- Abouzeid, A.H.; Patel, N.R.; Torchilin, V.P. Polyethylene glycol-phosphatidylethanolamine (PEG-PE)/vitamin E micelles for co-delivery of paclitaxel and curcumin to overcome multi-drug resistance in ovarian cancer. Int J Pharm 2014, 464, 178-184. [CrossRef]

- Ganta, S.; Amiji, M. Coadministration of Paclitaxel and curcumin in nanoemulsion formulations to overcome multidrug resistance in tumor cells. Mol Pharm 2009, 6, 928-939. [CrossRef]

- Sarisozen, C.; Vural, I.; Levchenko, T.; Hincal, A.A.; Torchilin, V.P. PEG-PE-based micelles co-loaded with paclitaxel and cyclosporine A or loaded with paclitaxel and targeted by anticancer antibody overcome drug resistance in cancer cells. Drug Deliv 2012, 19, 169-176. [CrossRef]

- Sawant, R.R.; Vaze, O.S.; Rockwell, K.; Torchilin, V.P. Palmitoyl ascorbate-modified liposomes as nanoparticle platform for ascorbate-mediated cytotoxicity and paclitaxel co-delivery. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2010, 75, 321-326. [CrossRef]

- Gill, K.K.; Kaddoumi, A.; Nazzal, S. Mixed micelles of PEG(2000)-DSPE and vitamin-E TPGS for concurrent delivery of paclitaxel and parthenolide: enhanced chemosenstization and antitumor efficacy against non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines. European journal of pharmaceutical sciences : official journal of the European Federation for Pharmaceutical Sciences 2012, 46 1-2, 64-71.

- Kabary, D.M.; Helmy, M.W.; Elkhodairy, K.A.; Fang, J.Y.; Elzoghby, A.O. Hyaluronate/lactoferrin layer-by-layer-coated lipid nanocarriers for targeted co-delivery of rapamycin and berberine to lung carcinoma. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2018, 169, 183-194. [CrossRef]

- Webb, M.S.; Johnstone, S.; Morris, T.J.; Kennedy, A.; Gallagher, R.; Harasym, N.; Harasym, T.; Shew, C.R.; Tardi, P.; Dragowska, W.H.; et al. In vitro and in vivo characterization of a combination chemotherapy formulation consisting of vinorelbine and phosphatidylserine. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2007, 65, 289-299. [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, H.M.; Elzoghby, A.O.; Helmy, M.W.; Samaha, M.W.; Fang, J.Y.; Freag, M.S. Liquid crystalline assembly for potential combinatorial chemo-herbal drug delivery to lung cancer cells. Int J Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 499-517. [CrossRef]

- Lúcio, M.; Lopes, C.M.; Oliveira, M.E.C.R. Functional Lipid Nanosystems in Cancer; CRC Press: 2021.

- Mohan, P.; Rapoport, N. Doxorubicin as a molecular nanotheranostic agent: effect of doxorubicin encapsulation in micelles or nanoemulsions on the ultrasound-mediated intracellular delivery and nuclear trafficking. Mol Pharm 2010, 7, 1959-1973. [CrossRef]

- Sriraman, S.K.; Salzano, G.; Sarisozen, C.; Torchilin, V. Anti-cancer activity of doxorubicin-loaded liposomes co-modified with transferrin and folic acid. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2016, 105, 40-49. [CrossRef]

- Štěrba, M.; Popelová, O.; Vávrová, A.; Jirkovský, E.; Kovaříková, P.; Geršl, V.; Šimůnek, T. Oxidative Stress, Redox Signaling, and Metal Chelation in Anthracycline Cardiotoxicity and Pharmacological Cardioprotection. Antioxid Redox Signal 2012, 18, 899-929. [CrossRef]

- Nitiss, J.L. Targeting DNA topoisomerase II in cancer chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2009, 9, 338. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Song, Y.; Lu, M.; Lin, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Su, Y.; Deng, Y. Evaluation of the antitumor effect of dexamethasone palmitate and doxorubicin co-loaded liposomes modified with a sialic acid-octadecylamine conjugate. Eur J Pharm Sci 2016, 93, 177-183. [CrossRef]

- Elbialy, N.S.; Mady, M.M. Ehrlich tumor inhibition using doxorubicin containing liposomes. Saudi Pharm J 2015, 23, 182-187. [CrossRef]

- Misra, R.; Sahoo, S.K. Intracellular trafficking of nuclear localization signal conjugated nanoparticles for cancer therapy. Eur J Pharm Sci 2010, 39, 152-163. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Qiao, M.; Chen, Q.; Tian, C.; Long, M.; Wang, M.; Li, Z.; Hu, W.; Li, G.; Cheng, L.; et al. Enhanced effect of pH-sensitive mixed copolymer micelles for overcoming multidrug resistance of doxorubicin. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 9877-9887. [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, G.; Mathur, A.; Mallade, P.; Gerlach, S.; Willis, J.; Datta, A.; Srivastav, S.; Abdel-Mageed, A.B.; Mondal, D. Nelfinavir targets multiple drug resistance mechanisms to increase the efficacy of doxorubicin in MCF-7/Dox breast cancer cells. Biochimie 2016, 124, 53-64. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Sun, C.; Wu, J.; Tang, J. Reversing of multidrug resistance breast cancer by co-delivery of P-gp siRNA and doxorubicin via folic acid-modified core-shell nanomicelles. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2016, 138, 60-69. [CrossRef]

- Shimpo, K.; Nagatsu, T.; Yamada, K.; Sato, T.; Niimi, H.; Shamoto, M.; Takeuchi, T.; Umezawa, H.; Fujita, K. Ascorbic acid and adriamycin toxicity. Am J Clin Nutr 1991, 54, 1298s-1301s. [CrossRef]

- Borska, S.; Chmielewska, M.; Wysocka, T.; Drag-Zalesinska, M.; Zabel, M.; Dziegiel, P. In vitro effect of quercetin on human gastric carcinoma: targeting cancer cells death and MDR. Food Chem Toxicol 2012, 50, 3375-3383. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Park, K.S.; Choo, H.; Chong, Y. Quercetin-POM (pivaloxymethyl) conjugates: Modulatory activity for P-glycoprotein-based multidrug resistance. Phytomedicine 2015, 22, 778-785. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Li, Y.; Kim, M.S.; Kang, S.W.; Jeong, J.H.; Lee, D.S. Synthesis and evaluation of biotin-conjugated pH-responsive polymeric micelles as drug carriers. Int J Pharm 2012, 427, 435-442. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.S.; Mussi, S.V.; Gomes, D.A.; Yoshida, M.I.; Frezard, F.; Carregal, V.M.; Ferreira, L.A.M. α-Tocopherol succinate improves encapsulation and anticancer activity of doxorubicin loaded in solid lipid nanoparticles. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2016, 140, 246-253. [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Xu, Y.; Qiu, L. Enhanced combination therapy effect on paclitaxel-resistant carcinoma by chloroquine co-delivery via liposomes. Int J Nanomedicine 2015, 10, 6615-6632. [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.H.; Wientjes, M.G.; Au, J.L. Kinetics of P-glycoprotein-mediated efflux of paclitaxel. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2001, 298, 1236-1242.

- Quan, F.; Pan, C.; Ma, Q.; Zhang, S.; Yan, L. Reversal effect of resveratrol on multidrug resistance in KBv200 cell line. Biomed Pharmacother 2008, 62, 622-629. [CrossRef]

- Longley, D.B.; Harkin, D.P.; Johnston, P.G. 5-fluorouracil: mechanisms of action and clinical strategies. Nat Rev Cancer 2003, 3, 330-338. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Gao, D.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, D.; Liu, J.; Shuai, X. Drug and gene co-delivery systems for cancer treatment. Biomaterials Science 2015, 3, 1035-1049. [CrossRef]

- Saraswathy, M.; Gong, S. Recent developments in the co-delivery of siRNA and small molecule anticancer drugs for cancer treatment. Materials Today 2014, 17, 298-306. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.J.; Billingsley, M.M.; Haley, R.M.; Wechsler, M.E.; Peppas, N.A.; Langer, R. Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2021, 20, 101-124. [CrossRef]

- Fenton, O.S.; Olafson, K.N.; Pillai, P.S.; Mitchell, M.J.; Langer, R. Advances in Biomaterials for Drug Delivery. Advanced Materials 2018, 30, 1705328. [CrossRef]

- Jogdeo, C.M.; Panja, S.; Kanvinde, S.; Kapoor, E.; Siddhanta, K.; Oupický, D. Advances in Lipid-Based Codelivery Systems for Cancer and Inflammatory Diseases. Advanced Healthcare Materials n/a, 2202400. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, Y.; Ge, Q.; Chang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, K.; Peng, D.; Chen, W. Co-delivery of gambogenic acid and VEGF-siRNA with anionic liposome and polyethylenimine complexes to HepG2 cells. J Liposome Res 2019, 29, 322-331. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, A.; Bai, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Cui, S.; Piao, Y.; Zhang, S. Co-delivery of resveratrol and p53 gene via peptide cationic liposomal nanocarrier for the synergistic treatment of cervical cancer and breast cancer cells. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2019, 51, 746-753. [CrossRef]

- Jose, A.; Labala, S.; Venuganti, V.V.K. Co-delivery of curcumin and STAT3 siRNA using deformable cationic liposomes to treat skin cancer. Journal of Drug Targeting 2017, 25, 330-341. [CrossRef]

- Jose, A.; Labala, S.; Ninave, K.M.; Gade, S.K.; Venuganti, V.V.K. Effective Skin Cancer Treatment by Topical Co-delivery of Curcumin and STAT3 siRNA Using Cationic Liposomes. AAPS PharmSciTech 2018, 19, 166-175. [CrossRef]

- Muddineti, O.S.; Shah, A.; Rompicharla, S.V.K.; Ghosh, B.; Biswas, S. Cholesterol-grafted chitosan micelles as a nanocarrier system for drug-siRNA co-delivery to the lung cancer cells. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2018, 118, 857-863. [CrossRef]

- Abtahi, N.A.; Naghib, S.M.; Ghalekohneh, S.J.; Mohammadpour, Z.; Nazari, H.; Mosavi, S.M.; Gheibihayat, S.M.; Haghiralsadat, F.; Reza, J.Z.; Doulabi, B.Z. Multifunctional stimuli-responsive niosomal nanoparticles for co-delivery and co-administration of gene and bioactive compound: In vitro and in vivo studies. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 429, 132090. [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Li, Y.; Deng, X.; Wang, X.; Cui, X.; Lu, J.; Pan, Z.; Wu, Y. Self-assembled fluorescent hybrid nanoparticles-mediated collaborative lncRNA CCAT1 silencing and curcumin delivery for synchronous colorectal cancer theranostics. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19, 238. [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.S.; Ediriweera, M.K.; Rajagopalan, U.; Karunaratne, D.N.; Tennekoon, K.H.; Samarakoon, S.R. A new liposomal nanocarrier for co-delivery of gedunin and p-glycoprotein siRNA to target breast cancer stem cells. Natural Product Research 2022, 36, 6389-6392. [CrossRef]

- Hientz, K.; Mohr, A.; Bhakta-Guha, D.; Efferth, T. The role of p53 in cancer drug resistance and targeted chemotherapy. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 8921-8946. [CrossRef]

- Eftekhari, R.B.; Maghsoudnia, N.; Samimi, S.; Zamzami, A.; Dorkoosh, F.A. Co-Delivery Nanosystems for Cancer Treatment: A Review. Pharmaceutical Nanotechnology 2019, 7, 90-112. [CrossRef]

- Oliveto, S.; Mancino, M.; Manfrini, N.; Biffo, S. Role of microRNAs in translation regulation and cancer. World J Biol Chem 2017, 8, 45-56. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.J.; Han, Q.B.; Wen, Z.S.; Ma, L.; Gao, J.; Zhou, G.B. Gambogenic acid induces G1 arrest via GSK3β-dependent cyclin D1 degradation and triggers autophagy in lung cancer cells. Cancer Lett 2012, 322, 185-194. [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, D.; Wang, M.; Xie, C.; Hu, Y.; Chang, H.C.; Li, Q. Synergistic effects of 5-fluorouracil and gambogenic acid on A549 cells: activation of cell death caused by apoptotic and necroptotic mechanisms via the ROS-mitochondria pathway. Biol Pharm Bull 2014, 37, 1259-1268. [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Sun, J.; Ge, T.; Zhang, K.; Gui, Q.; Zhang, S.; Chen, W. PEGylated liposomes as delivery systems for Gambogenic acid: Characterization and in vitro/in vivo evaluation. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2018, 172, 26-36. [CrossRef]

- Patwardhan, C.A.; Fauq, A.; Peterson, L.B.; Miller, C.; Blagg, B.S.J.; Chadli, A. Gedunin inactivates the co-chaperone p23 protein causing cancer cell death by apoptosis. J Biol Chem 2013, 288, 7313-7325. [CrossRef]

- Nwokwu, C.D.U.; Samarakoon, S.R.; Karunaratne, D.N.; Katuvawila, N.P.; Pamunuwa, G.K.; Ediriweera, M.K.; Tennekoon, K.H. Induction of apoptosis in response to improved gedunin by liposomal nano-encapsulation in human non-small-cell lung cancer (NCI-H292) cell line. Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research 2017, 16, 2079-2087.

| Chemotherapeutic agent | Natural compound |

Lipid-based nanocarrier | Composition | Strategy | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-FU | RSV | Ultradeformable liposomes |

PL90G:SC | Synergistic effect | [47] |

| PEGylated liposomes | EPC:DSPE-PEG2000 | Synergistic effect | [48] | ||

| DTX | CUR | SLNs | Compritol® 888 ATO, GMS, Poloxamer 188Functionalization: Folic acid | Synergistic effect | [49] |

| DOX | BCL | NLCs | SA, SPC, Precirol® ATO5, Cremophor® ELP, DDAB | Synergistic effect | [50] |

| CUR | Liposomes | PEG-RGDK-lipopeptide | Synergistic effect | [51] | |

| Oil-in-water emulsion | Precirol® ATO 5, LabrafacTM lipophile WL 1349, Lipoid S75, Cremophor® RH 40, Glycerin | Synergistic effect | [52] | ||

| Liposomes | DPPC:DSPE:CHOL:PEG2000 | Synergistic effect | [9] | ||

| DHA | NLCs | Tween® 80, Oleic acid, Triethanolamine, Compritol® 888 ATO, EDTA | Overcome MDR | [53] | |

| OA | Liposomes | HSPC:CHOL:DSPE:PEG2000 | Synergistic effect | [54] | |

| PA | Liposomes | PC:CHOL | Synergistic effect | [55] | |

| QUER | Liposomes | BIO:DSPE:PEG2000 | Overcome MDR | [37] | |

| Phytosomes | Lecithin | Synergistic effect | [56] | ||

| TS | SLNs | Compritol® 888 ATO, TPGS, Triethanolamine | Synergistic effect | [57] | |

| BJO | LLCNs | GMO:P407 Hexagonal phase inducer: Oleic acid |

Overcome MDR | [58] | |

| ETP | CUR | NLCs | GMS, SPC, Oleic acid, DDAB | Decreasing the effective chemotherapy dose | [59] |

| Nanoemulsion | SPC, Tween® 80 | Additive effect | [60] | ||

| GEM | BCL | NLCs | SPC, Precirol® ATO-5, Olive oil, Tween® 80, DDAB | Synergistic effect | [61] |

| ITC | CTL | Liposomes | DPPC:CHOL:DSPE-PEG2000-FA | Synergistic effect | [62] |

| MTX | BCN | Lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticle |

DSPE-PEG2000:SA:Gelucire® 50/13:PLA | Synergistic effect | [63] |

| PTX | BCL | Nanoemulsion | MCT, Soybean oil, Soybean lecithin, Kolliphor® P188, Glycerol |

Overcome MDR | [64] |

| BOR | Lipid-albumin nanoassemblies |

Egg yolk lecithin PL 100 M:BSA | Potentiation effect | [65] | |

| CUR | SLNs | GMS; TPGS, Tween® 80 Functionalization: Conjugated stearic acid and folate |

Overcome MDR | [42] | |

| Micelles | PEG2000-DSPE/Vit E | Synergistic effect | [66] | ||

| Nanoemulsion | Flaxseed oil, Egg lecithin | Overcome MDR | [67] | ||

| CycA | Micelles | PEG2000-PE | Overcome MDR | [68] | |

| PA | Liposomes | EPC:CHOL | Potentiation effect | [69] | |

| PTN | Micelles | PEG2000-DSPE/Vit E | Synergistic effect | [70] | |

| RSV | Liposomes | PC:DSPE-PEG2000 | Synergistic effect | [2] | |

| RAP | BER | Layer by layer lipid nanoparticles |

GMS, Tween® 80 | Synergistic effect | [71] |

| VNB | Phosphatidylserine | Liposomes | SM:CHOL:DPPS:PEG2000-DSPE | Synergistic effect | [72] |

| PMX | RSV | LLCNs | GMO:P407 Ion-pairing: CTAB |

Reducing side effects | [73] |

| Nanocarrier | Composition | Nucleic acid | Natural compound | Physical-chemical characterization | Cancer cell lines | Remarks | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (nm) and PDI | ζ-potential (mV) | EE (%) and DL (%) | |||||||

| Lipoplexes | CHEMS, CHOL, PE, PEI |

VEGF siRNA | GNA | Size: 200 PDI: < 0.3 |

-30 | EE: 81.8±2.04% | HepG2 cells | Downregulation of VEGF expression. GNA loaded Lipoplexes have stronger pro-apoptotic effects. |

[99] |

| Lipoplexes | CD014, DOPE | p53 pDNA | RSV | Size: 65.9 to 220.7 | +81.4 to +109.8 | EE: >90% | MCF-7 and HeLa cells | RSV and p53 pDNA showed synergistic effect on cells growth inhibition. | [100] |

| Lipoplexes | DOTAP, DOPE, Sodium cholate, C6 ceramide |

STAT3 siRNA | CUR | Size: 157.0±11.0 PDI: 0.46±0.003 |

+70.5±7.0 | EE: 87.5±4.0% (10:1 lipid:CUR ratio) | A431 cells | Downregulation of STAT3 expression. CUR and STAT3 siRNA demonstrated synergistic effect in cancer cell inhibition. |

[101] |

| Lipoplexes | DOTAP, DOPE, Sodium cholate, C6 ceramide | STAT3 siRNA | CUR | Size: 192.6±9.0 PDI: 0.326±0.004 |

+56.4 ± 8.0 | EE: 86.8±6.0% | B16F10 cells | CUR and STAT3 siRNA had a synergistic effect on cancer cell inhibition. The lipoplexes enabled a non-invasive topical iontophoretic application. |

[102] |

| Micelleplexes | Chitosan, Cholesterol chloroformate | siRNA | CUR | Size: 165±2.6 PDI: 0.16±0.02 |

+24.8±2.2 | - | A549 cells | CUR and siRNA were delivered in time dependent manner via clathrin dependent endocytosis mechanism. | [103] |

| Nioplexes | CHOL, Tween 80, Tween 60, DOTAP | miR-34a | CUR | Size: 60±0.05 PDI: 0.15±0.74 |

+27±0.30 | EE: 100% | A270cp-1, PC3, MCF-7 cells |

Co-delivery induced higher cytotoxicity than co-administration. | [104] |

| Lipopolyplexes | DSPE-mPEG, PEI-PDLLA | CCAT1 siRNA | CUR | Size: 151 | +12.37 to -10.48 (depending on CNP:siCCAT1 ratios) | EE: 85.85±3.37% DL: 14.36±1.28% |

HT-29 cells | Co-delivery of CUR and siCCAT1 increases HT-29 cell sensitivity to anti-cancer efficiency of CUR and the silencing effect of CCAT1. | [105] |

| Lipoplexes | Stearylamine, CHOL, Phosphatidylcholine | P-gp siRNA | GED | Size: 236.01 ±44.80 PDI: 0.35±0.15 |

+41.30 ±4.48 | - | MDA-MB 231 cells | Lipoplexes were able to inhibit cell proliferation. Downregulation of P-gp, Cyclin D1, p53, Bax, and Survivin expression. |

[106] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).