Submitted:

09 March 2023

Posted:

10 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

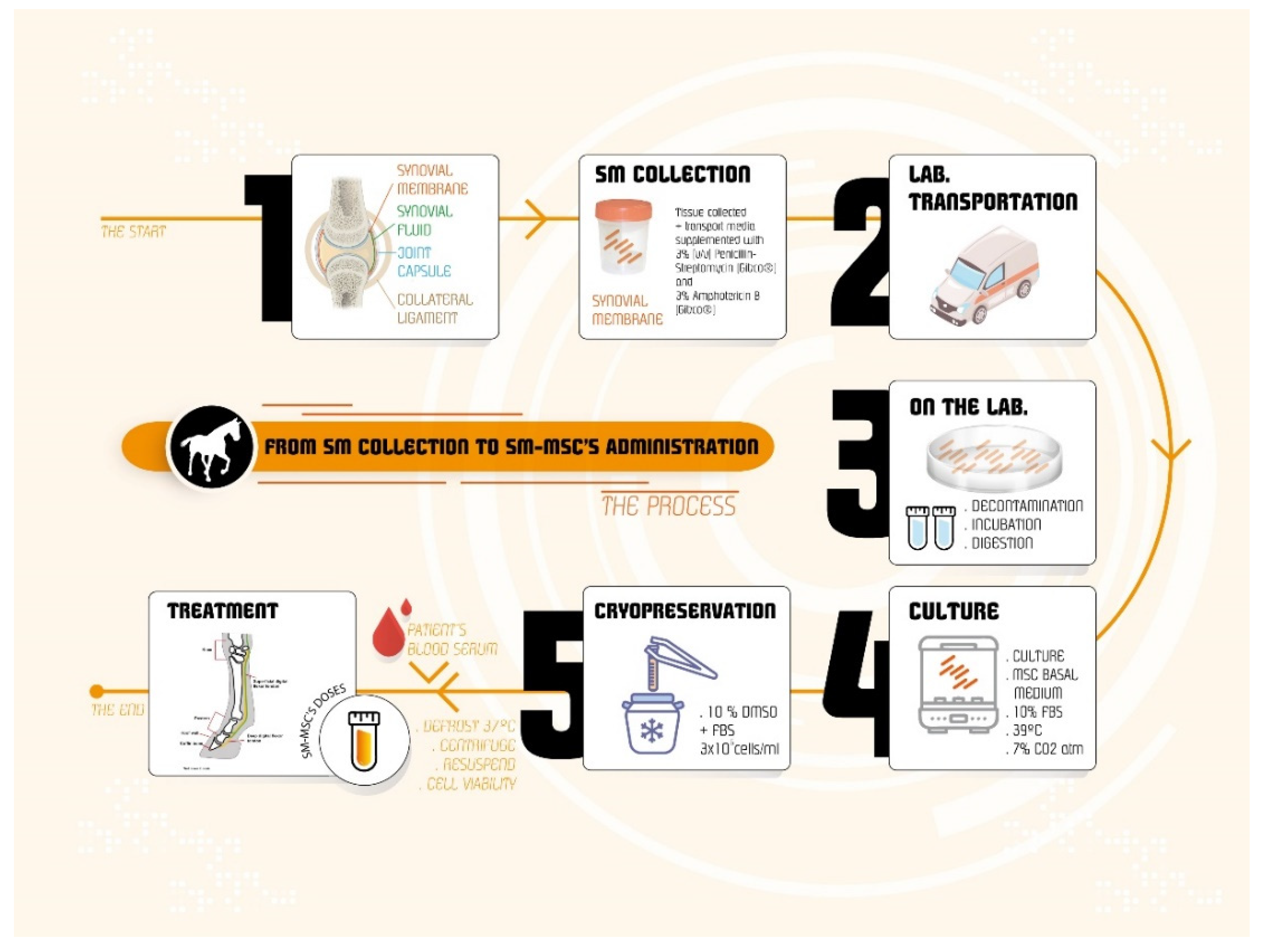

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Horses Selection

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Ethics and Regulation

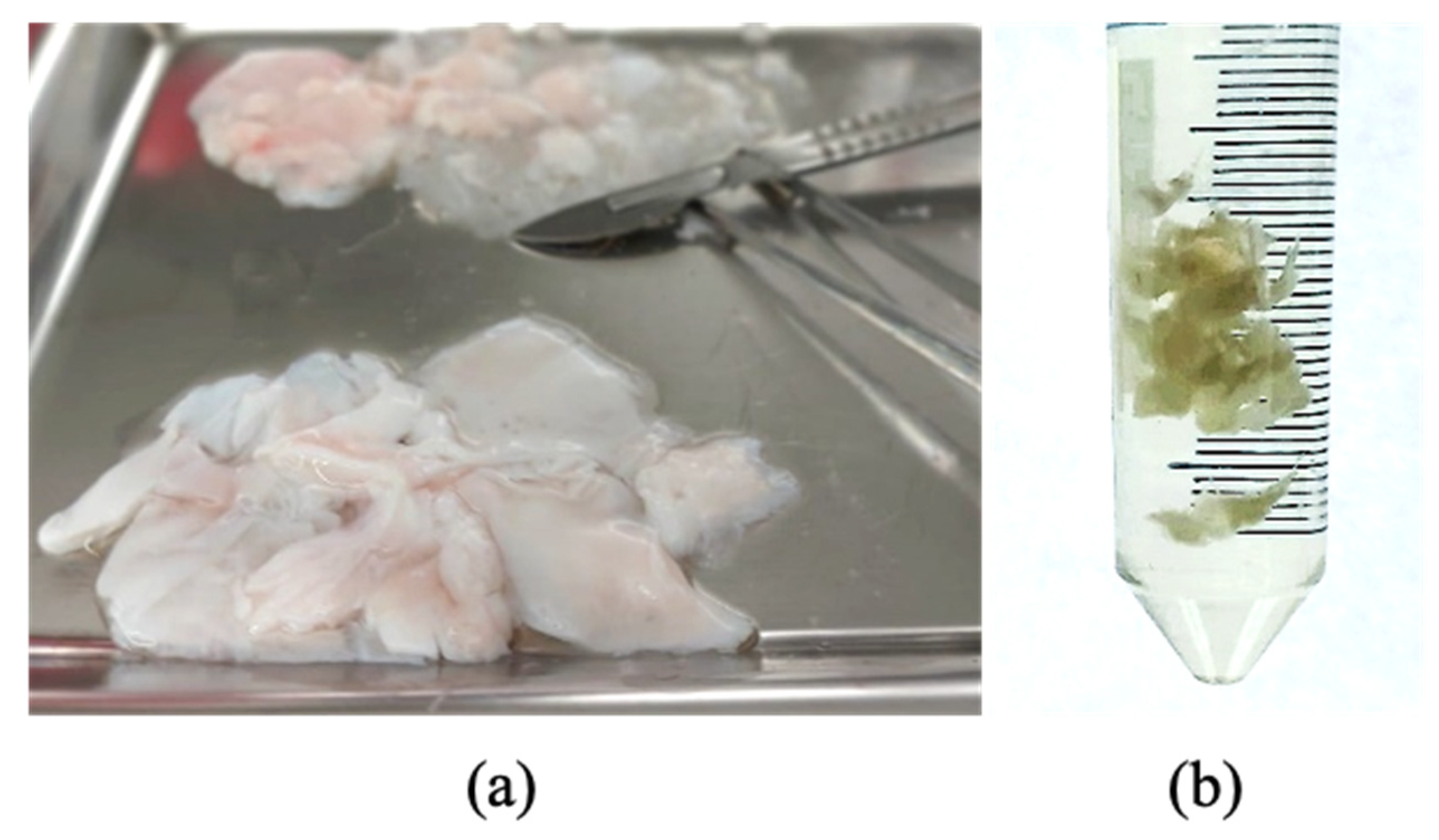

2.4. Donor selection and SM collection

2.5. eSM-MSCs isolation

2.6. SM-MSCs characterization

2.6.1. Tri-lineage differentiation protocols

Adipogenic Differentiation and Oil Red O Staining

Chondrogenic Differentiation and Alcian Blue Staining

Osteogenic Differentiation and Alizarin Red S Staining

2.6.2. Karyotype analysis

2.6.3. Secretome- Cells Conditioned Medium (CM) Analysis

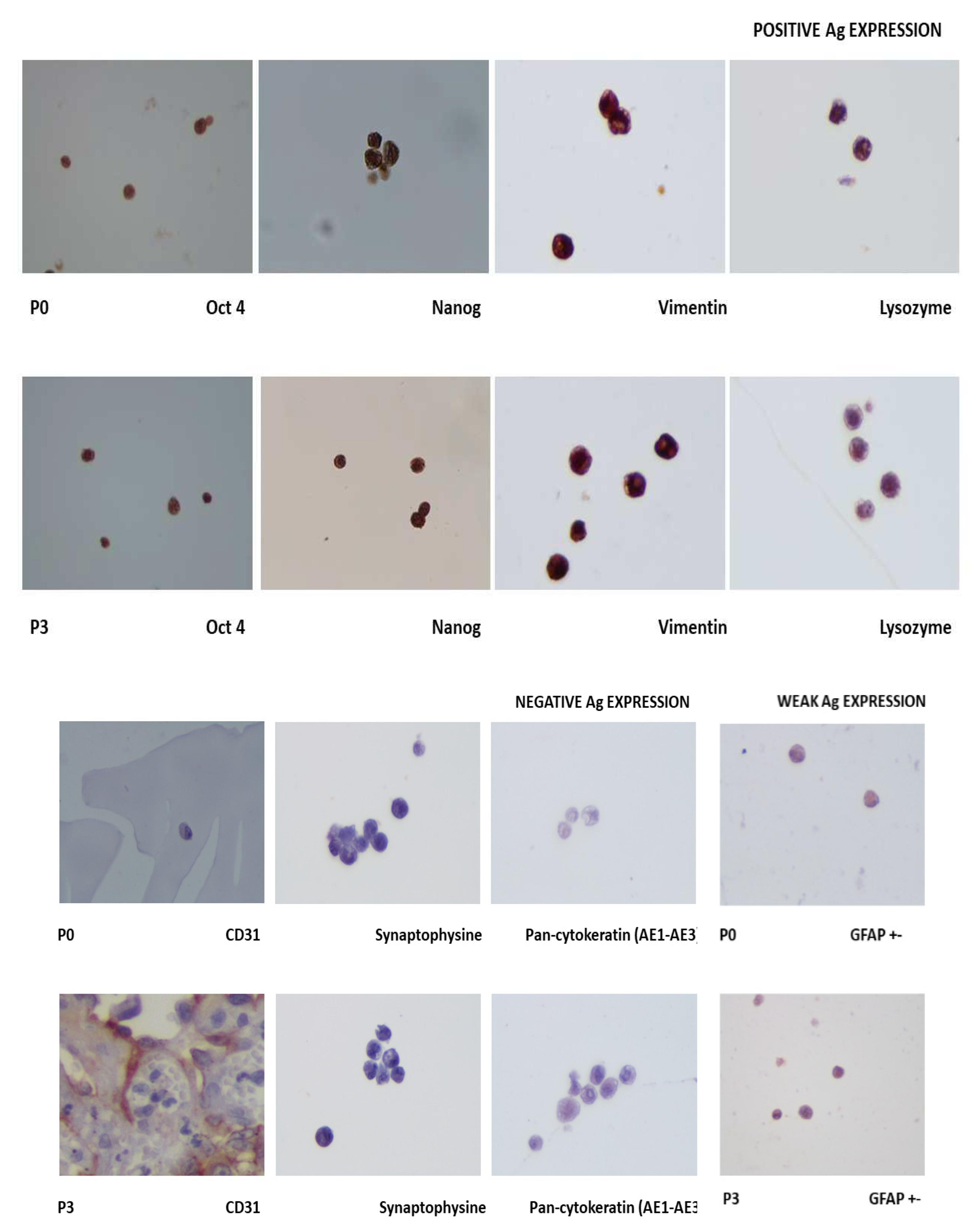

2.6.4. Immunohistochemistry

2.7. eSM-MSCs solution preparation

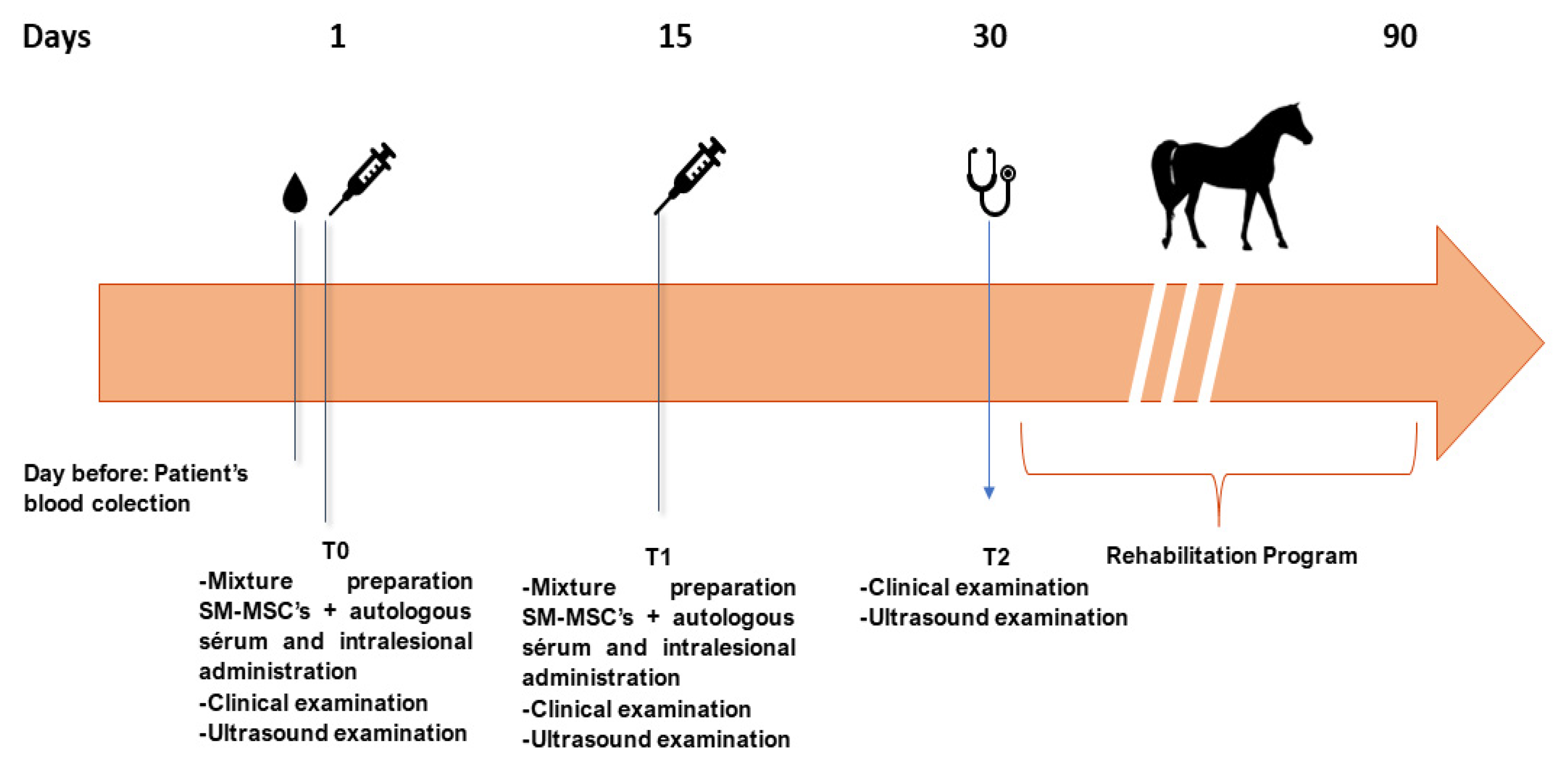

2.8. Treatment Protocol

2.8.1. Intralesional eSM-MSCs injection

2.8.2. Clinical evaluation – Serial evaluations

3. Results

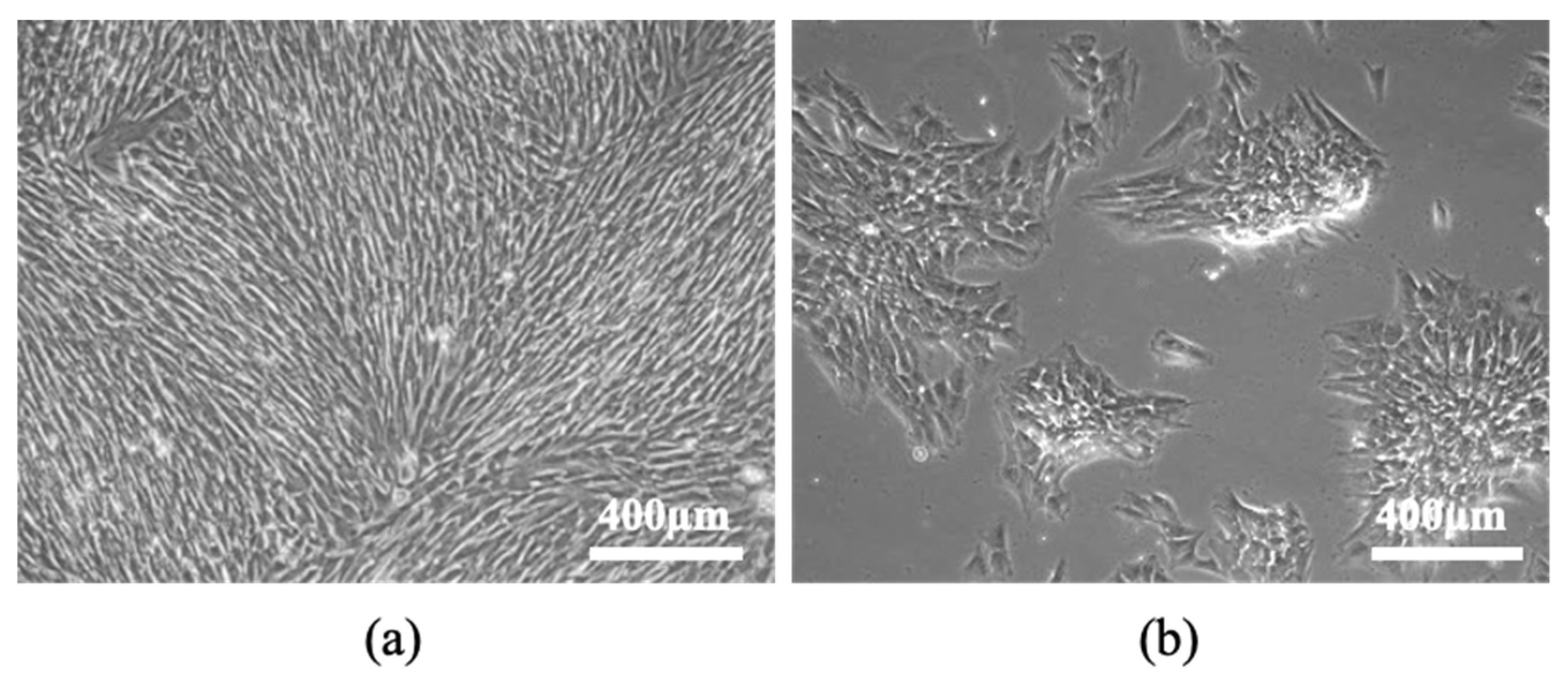

3.1. eSM-MSCs isolation

3.2. eSM-MSCs characterization

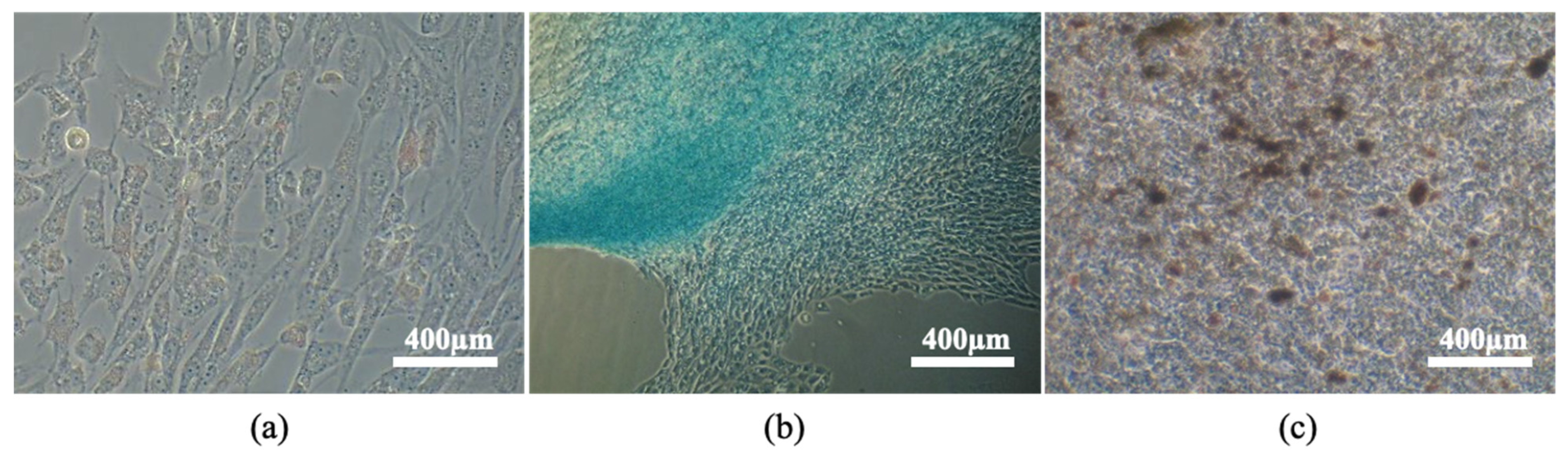

3.2.1. Tri-lineage differentiation

Adipogenic differentiation – Oil Red O Staining

Chondrogenic differentiation – Alcian Blue Staining

Osteogenic differentiation – Alizarin Red Staining

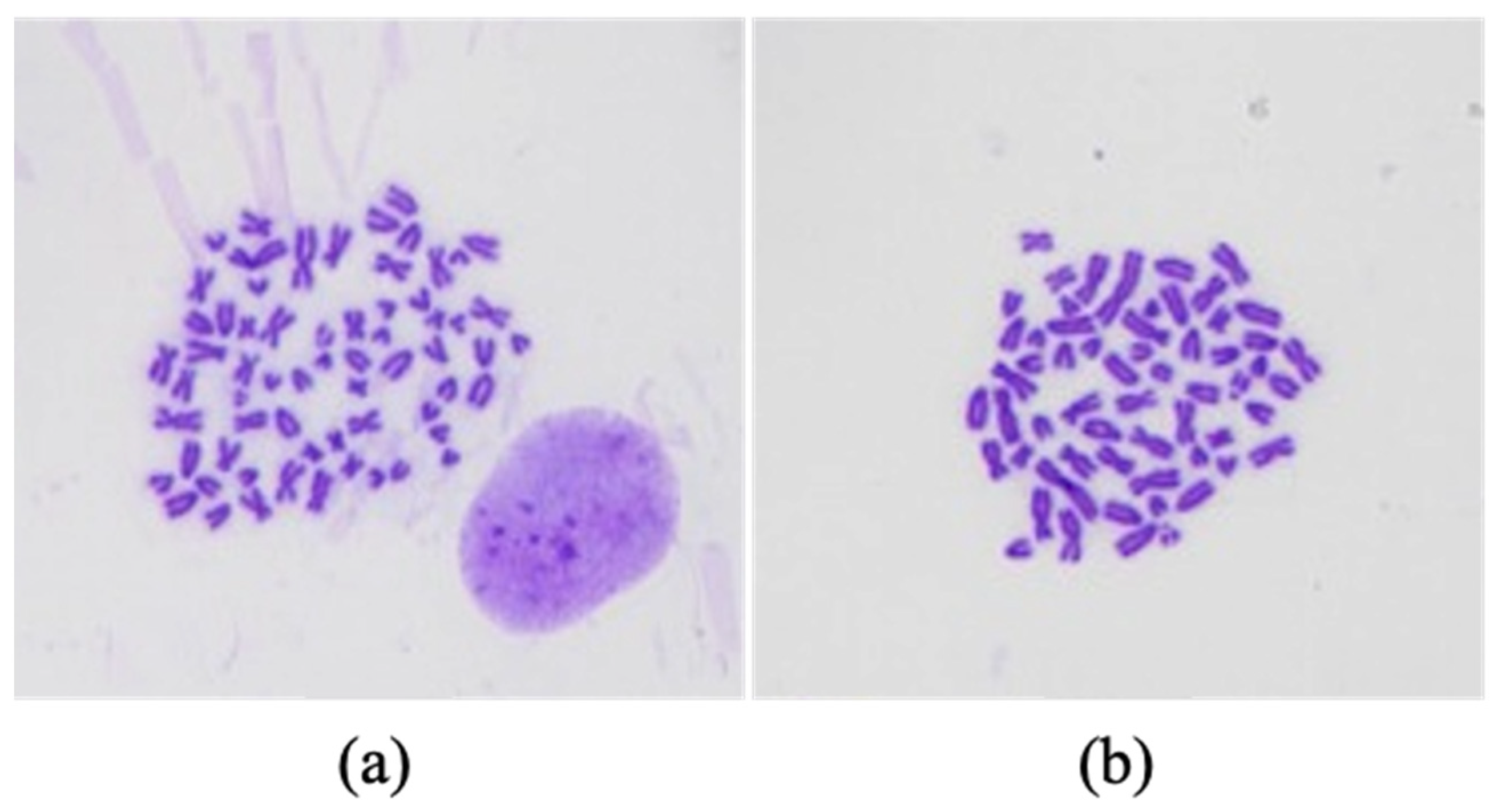

3.2.2. Karyotype analysis

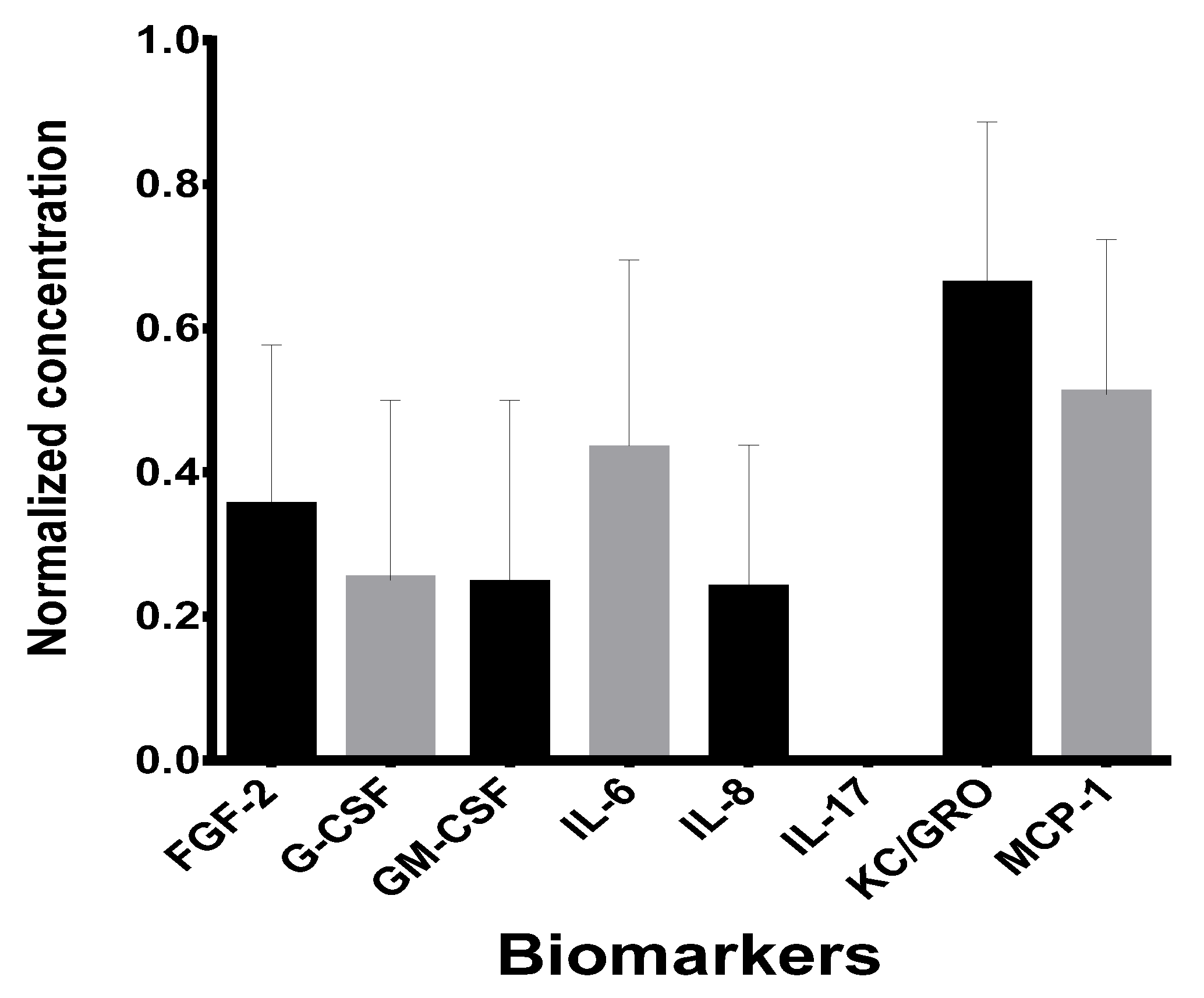

3.2.3. Secretome analysis

3.2.4. Immunohistochemistry

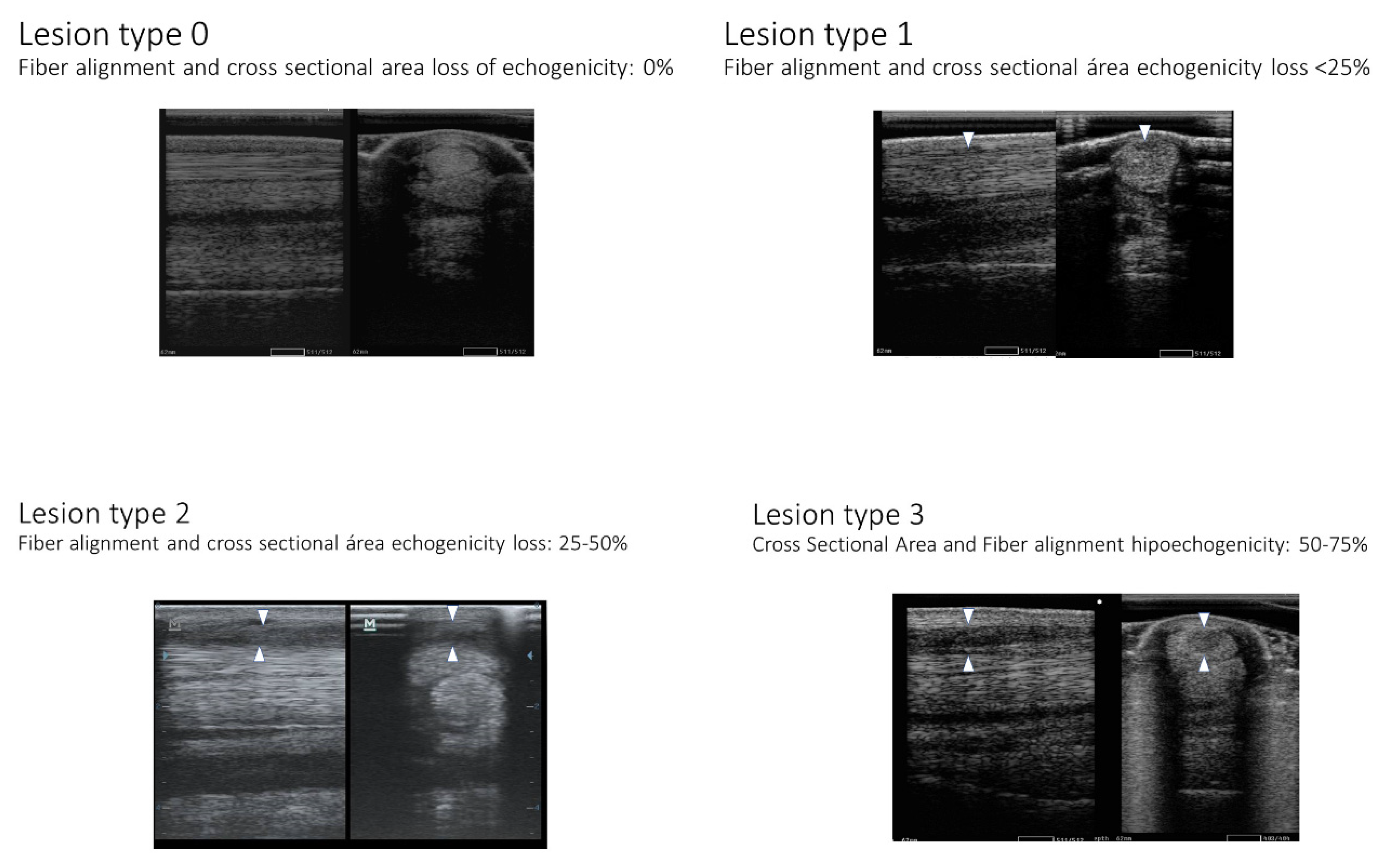

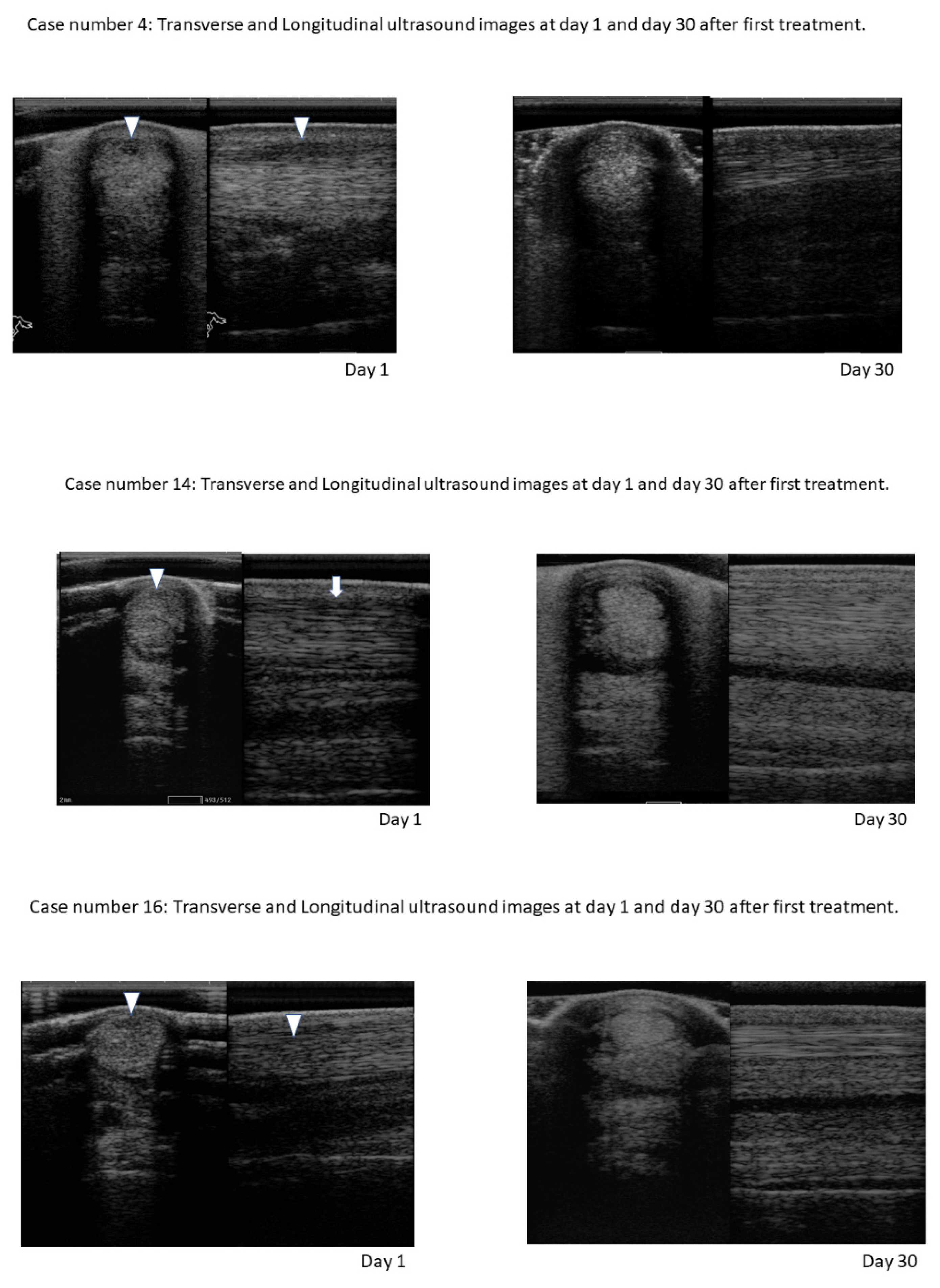

3.2. Treatment Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAEP | American Association of Equine Practitioners |

| AE1/AE3 | Pan-Cytokeratin |

| BM-MSC | Bone Marrow mesenchymal stem cell |

| CD | Cluster differentiation |

| c-Kit | Proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase or stem cell factor receptor |

| CM | Conditioned Medium |

| cm2 | Square centimetre |

| Coll-II | Collagen type II |

| COMP | Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein |

| CPD | Cumulative population doublings |

| DMSO | Dimethylsulphoxide |

| DPBS | Dulbecco′s Phosphate Buffered Saline |

| eSM-MSC | Equine synovial membrane mesenchymal stem cell |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| FGF-2 | Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor |

| G-CSF | Granulocyte Colony Stimulating Factor |

| GFAP | Glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte-macrophage Colony Stimulating Factor |

| GRO/KC | Human Growth-regulated oncogene/Keratinocyte Chemoattractant |

| ICBAS-UP | Instituto de Ciências Biomédicas Abel Salazar – Universidade do Porto |

| IL | Interleukins |

| ISCT | International Society for Cellular Therapy |

| IV | Endovenous |

| kg | Kilogram |

| MCB | Master Cell Banks |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 |

| mg | milligram |

| MHC-II | Major Histocompatibility Complex |

| MHz | Megahertz |

| min | minutes |

| mL | millilitre |

| MSCs | Mesenchymal Stem Cell |

| NSAIDs | Non-steroidal anti-inflamatory drugs |

| OA | Osteoarthritis |

| OCT-4 | Octamer-binding transcription factor 4 |

| ORBEA | Organismo Responsável pelo Bem-estar Animal |

| P | Passage |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PRP | Platelet-rich plasma |

| RT-PCR | Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| SID | Once a day |

| SM-MSC | Synovial Membrane Mesenchymal Stem Cell |

| UDP | Uridine Diphosphate |

| UDPGD | Uridine Diphosphate Glucose Dehydrogenase UDPGD |

| VEGF-R1 | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| WCB | Working cell banks |

References

- Ribitsch, I.; Oreff, G.L.; Jenner, F. Regenerative medicine for equine musculoskeletal diseases. Animals 2021, 11, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shojaee, A.; Parham, A. Strategies of tenogenic differentiation of equine stem cells for tendon repair: Current status and challenges. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuemmers, C.; Rebolledo, N.; Aguilera, R. Effect of the application of stem cells for tendon injuries in sporting horses. Arch. De Med. Vet. 2012, 44, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platonova, S.; Korovina, D.; Viktorova, E.; Savchenkova, I. Equine Tendinopathy Therapy Using Mesenchymal Stem Cells. KnE Life Sci. 2021, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, V.; Mankuzhy, P.; Sharma G, T. Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Veterinary Regenerative Therapy: Basic Physiology and Clinical Applications. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 17, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depuydt, E.; Broeckx, S.Y.; Van Hecke, L.; Chiers, K.; Van Brantegem, L.; Van Schie, H.; Beerts, C.; Spaas, J.H.; Pille, F.; Martens, A. The evaluation of equine allogeneic tenogenic primed mesenchymal stem cells in a surgically induced superficial digital flexor tendon lesion model. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 641441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berebichez-Fridman, R.; Montero-Olvera, P.R. Sources and clinical applications of mesenchymal stem cells: State-of-the-art review. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2018, 18, e264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Schauwer, C.; Meyer, E.; Van de Walle, G.R.; Van Soom, A. Markers of stemness in equine mesenchymal stem cells: A plea for uniformity. Theriogenology 2011, 75, 1431–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bari, C.; Dell’Accio, F.; Tylzanowski, P.; Luyten, F.P. Multipotent mesenchymal stem cells from adult human synovial membrane. Arthritis Rheum. 2001, 44, 1928–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvanová, D.; Tóthová, T.; Sarissky, M.; Amrichová, J.; Rosocha, J. Isolation and characterization of synovial mesenchymal stem cells. Folia Biol. (Praha) 2011, 57, 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi, Y.; Sekiya, I.; Yagishita, K.; Muneta, T. Comparison of human stem cells derived from various mesenchymal tissues: Superiority of synovium as a cell source. Arthritis Rheum. Off. J. Am. Coll. Rheumatol. 2005, 52, 2521–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirasawa, S.; Sekiya, I.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Yagishita, K.; Ichinose, S.; Muneta, T. In vitro chondrogenesis of human synovium-derived mesenchymal stem cells: Optimal condition and comparison with bone marrow-derived cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2006, 97, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koga, H.; Muneta, T.; Ju, Y.J.; Nagase, T.; Nimura, A.; Mochizuki, T.; Ichinose, S.; Von der Mark, K.; Sekiya, I. Synovial stem cells are regionally specified according to local microenvironments after implantation for cartilage regeneration. Stem Cells 2007, 25, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bami, M.; Sarlikiotis, T.; Milonaki, M.; Vikentiou, M.; Konsta, E.; Kapsimali, V.; Pappa, V.; Koulalis, D.; Johnson, E.O.; Soucacos, P.N. Superiority of synovial membrane mesenchymal stem cells in chondrogenesis, osteogenesis, myogenesis and tenogenesis in a rabbit model. Injury 2020, 51, 2855–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayed, M.; Newby, S.; Misk, N.; Donnell, R.; Dhar, M. Xenogenic implantation of equine synovial fluid-derived mesenchymal stem cells leads to articular cartilage regeneration. Stem Cells Int. 2018, 2018, 1073705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermida-Gómez, T.; Fuentes-Boquete, I.; Gimeno-Longas, M.J.; Muiños-López, E.; Díaz-Prado, S.; Blanco, F.J. Quantification of cells expressing mesenchymal stem cell markers in healthy and osteoarthritic synovial membranes. J. Rheumatol. 2011, 38, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, T.; Muneta, T.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Nimura, A.; Yokoyama, A.; Koga, H.; Sekiya, I. Higher chondrogenic potential of fibrous synovium–and adipose synovium–derived cells compared with subcutaneous fat–derived cells: Distinguishing properties of mesenchymal stem cells in humans. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fickert, S.; Fiedler, J.; Brenner, R. Identification, quantification and isolation of mesenchymal progenitor cells from osteoarthritic synovium by fluorescence automated cell sorting. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2003, 11, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, A.A.F.; Favaron, P.O.; da Silva, L.C.L.C.; Baccarin, R.Y.A.; Miglino, M.A.; Maria, D.A. Characterization of mesenchymal stem cells derived from the equine synovial fluid and membrane. BMC Vet. Res. 2015, 11, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-W. Chondrogenic Capacities of Equine Synovial Progenitor Populations. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Colbath, A.C.; Frisbie, D.D.; Dow, S.W.; Kisiday, J.D.; McIlwraith, C.W.; Goodrich, L.R. Equine models for the investigation of mesenchymal stem cell therapies in orthopaedic disease. Oper. Tech. Sport. Med. 2017, 25, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Cheng, J.; Shi, W.; Ren, B.; Zhao, F.; Shi, Y.; Yang, P.; Duan, X.; Zhang, J.; Fu, X. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes promote tendon regeneration by facilitating the proliferation and migration of endogenous tendon stem/progenitor cells. Acta Biomater. 2020, 106, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-González, A.; García-Sánchez, D.; Dotta, M.; Rodríguez-Rey, J.C.; Pérez-Campo, F.M. Mesenchymal stem cells secretome: The cornerstone of cell-free regenerative medicine. World J. Stem Cells 2020, 12, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, E.J. Lameness evaluation of the athletic horse. Vet. Clin. Equine Pract. 2018, 34, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AAEP Horse Show Committee. Guide to Veterinary Services for Horse Shows; American Association of Equine Practitioners: Lexington, KY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Broeckx, S.Y.; Seys, B.; Suls, M.; Vandenberghe, A.; Mariën, T.; Adriaensen, E.; Declercq, J.; Van Hecke, L.; Braun, G.; Hellmann, K. Equine allogeneic chondrogenic induced mesenchymal stem cells are an effective treatment for degenerative joint disease in horses. Stem Cells Dev. 2019, 28, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzola Domingo, R.; Riggs, C.M.; Gardner, D.S.; Freeman, S.L. Ultrasonographic scoring system for superficial digital flexor tendon injuries in horses: Intra-and inter-rater variability. Vet. Rec. 2017, 181, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melotti, L.; Carolo, A.; Elshazly, N.; Boesso, F.; Da Dalt, L.; Gabai, G.; Perazzi, A.; Iacopetti, I.; Patruno, M. Case Report: Repeated Intralesional Injections of Autologous Mesenchymal Stem Cells Combined With Platelet-Rich Plasma for Superficial Digital Flexor Tendon Healing in a Show Jumping Horse. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 843131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.A.; Donnell, J.R.; Donnell, A.D.; Frisbie, D.D. Retrospective analysis of lameness localisation in Western Performance Horses: A ten-year review. Equine Vet. J. 2021, 53, 1150–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrle, A.; Lilge, S.; Clegg, P.D.; Maddox, T.W. Equine flexor tendon imaging part 1: Recent developments in ultrasonography, with focus on the superficial digital flexor tendon. Vet. J. 2021, 278, 105764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iimori, M.; Tamura, N.; Seki, K.; Kasashima, Y. Relationship between the ultrasonographic findings of suspected superficial digital flexor tendon injury and the prevalence of subsequent severe superficial digital flexor tendon injuries in Thoroughbred horses: A retrospective study. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2022, 84, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.; DaSilva, D.; Rosenbaum, C.; Blikslager, A.; Edwards, R.B., III. Ultrasound findings in tendons and ligaments of lame sport horses competing or training in South Florida venues during the winter seasons of 2007 through 2016. Equine Vet. Educ. 2021, 33, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D.J.; Dudhia, J.; Smith, R.K.W.; Roberts, S.J.; Conzemius, M.; Innes, J.F.; Fortier, L.A.; Meeson, R.L. Position Statement: Minimal criteria for reporting veterinary and animal medicine research for mesenchymal stromal/stem cells in orthopaedic applications. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomopoulos, S.; Parks, W.C.; Rifkin, D.B.; Derwin, K.A. Mechanisms of tendon injury and repair. J. Orthop. Res. 2015, 33, 832–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schils, S.; Turner, T. Review of Early Mobilization of Muscle, Tendon, and Ligament after Injury in Equine Rehabilitation. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Convention of the American Association of Equine Practitioners, Baltimore, MD, USA, 4–8 December 2010; pp. 374–380. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneps, A.J. Practical rehabilitation and physical therapy for the general equine practitioner. Vet. Clin. Equine Pract. 2016, 32, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, E.J. Controlled exercise in equine rehabilitation. Vet. Clin. Equine Pract. 2016, 32, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortved, K.F. Regenerative medicine and rehabilitation for tendinous and ligamentous injuries in sport horses. Vet. Clin. Equine Pract. 2018, 34, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godwin, E.; Young, N.; Dudhia, J.; Beamish, I.; Smith, R. Implantation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells demonstrates improved outcome in horses with overstrain injury of the superficial digital flexor tendon. Equine Vet. J. 2012, 44, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, A.L.; Linardi, R.L.; McClung, G.; Mammone, R.M.; Ortved, K.F. Comparison of the chondrogenic differentiation potential of equine synovial membrane-derived and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayed, M.; Adair, S.; Dhar, M. Effects of Normal Synovial Fluid and Interferon Gamma on Chondrogenic Capability and Immunomodulatory Potential Respectively on Equine Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, D.; Ishikawa, S.; Sunaga, T.; Saito, Y.; Sogawa, T.; Nakayama, K.; Hobo, S.; Hatazoe, T. Osteochondral regeneration of the femoral medial condyle by using a scaffold-free 3D construct of synovial membrane-derived mesenchymal stem cells in horses. BMC Vet. Res. 2022, 18, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fülber, J.; Maria, D.A.; Silva, L.C.L.C.d.; Massoco, C.O.; Agreste, F.; Baccarin, R.Y.A. Comparative study of equine mesenchymal stem cells from healthy and injured synovial tissues: An in vitro assessment. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2016, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, S.E.; Loring, J.F. Genomic instability in pluripotent stem cells: Implications for clinical applications. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 4578–4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupski, J.R. Genome mosaicism—One human, multiple genomes. Science 2013, 341, 358–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohrback, S.; Siddoway, B.; Liu, C.S.; Chun, J. Genomic mosaicism in the developing and adult brain. Dev. Neurobiol. 2018, 78, 1026–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, J.; Osei-Owusu, I.A.; Avigdor, B.E.; Tupler, R.; Pevsner, J. Mosaicism in human health and disease. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2020, 54, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vattathil, S.; Scheet, P. Extensive hidden genomic mosaicism revealed in normal tissue. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 98, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petropoulos, M.; Tsaniras, S.C.; Taraviras, S.; Lygerou, Z. Replication licensing aberrations, replication stress, and genomic instability. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2019, 44, 752–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieto González, E.; Haider, K.H. Genomic Instability in Stem Cells: The Basic Issues. In Stem Cells: From Potential to Promise; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 107–150. [Google Scholar]

- Neri, S. Genetic stability of mesenchymal stromal cells for regenerative medicine applications: A fundamental biosafety aspect. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocchi, M.; Dotti, S.; Del Bue, M.; Villa, R.; Bari, E.; Perteghella, S.; Torre, M.L.; Grolli, S. Veterinary regenerative medicine for musculoskeletal disorders: Can mesenchymal stem/stromal cells and their secretome be the new frontier? Cells 2020, 9, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrigal, M.; Rao, K.S.; Riordan, N.H. A review of therapeutic effects of mesenchymal stem cell secretions and induction of secretory modification by different culture methods. J. Transl. Med. 2014, 12, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Naem, M.; Bourebaba, L.; Kucharczyk, K.; Röcken, M.; Marycz, K. Therapeutic mesenchymal stromal stem cells: Isolation, characterization and role in equine regenerative medicine and metabolic disorders. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2020, 16, 301–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shireman, P.K.; Contreras-Shannon, V.; Ochoa, O.; Karia, B.P.; Michalek, J.E.; McManus, L.M. MCP-1 deficiency causes altered inflammation with impaired skeletal muscle regeneration. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2007, 81, 775–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marine, T.; Marielle, S.; Graziella, M.; Fabio, R. Macrophages in skeletal muscle dystrophies, an entangled partner. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2021, 9, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, P.; Wen, H.; Ou, S.; Cui, J.; Fan, D. IL-6 promotes regeneration and functional recovery after cortical spinal tract injury by reactivating intrinsic growth program of neurons and enhancing synapse formation. Exp. Neurol. 2012, 236, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friese, N.; Gierschner, M.B.; Schadzek, P.; Roger, Y.; Hoffmann, A. Regeneration of damaged tendon-bone junctions (entheses)—TAK1 as a potential node factor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brent, A.E.; Tabin, C.J. FGF acts directly on the somitic tendon progenitors through the Ets transcription factors Pea3 and Erm to regulate scleraxis expression. Development 2004, 131, 3885–3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.-J.; Chen, X.; Li, G.; Chan, K.-M.; Heng, B.C.; Yin, Z.; Ouyang, H.-W. Concise review: Stem cell fate guided by bioactive molecules for tendon regeneration. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2018, 7, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Kida, Y.; Kabuto, Y.; Morihara, T.; Sukenari, T.; Nakagawa, H.; Onishi, O.; Oda, R.; Kida, N.; Tanida, T. Healing Effect of Subcutaneous Administration of Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor on Acute Rotator Cuff Injury in a Rat Model. Tissue Eng. Part A 2021, 27, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.R.; Ward, A.C.; Russell, A.P. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and its potential application for skeletal muscle repair and regeneration. Mediat. Inflamm. 2017, 2017, 7517350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuma, T.; Yamazaki, M.; Okawa, A.; Takahashi, H.; Kato, K.; Hashimoto, M.; Hayashi, K.; Furuya, T.; Fujiyoshi, T.; Kawabe, J. Neuroprotective therapy using granulocyte colony–stimulating factor for patients with worsening symptoms of thoracic myelopathy: A multicenter prospective controlled trial. Spine 2012, 37, 1475–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, M.; Sakuma, T.; Kato, K.; Furuya, T.; Koda, M. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor reduced neuropathic pain associated with thoracic compression myelopathy: Report of two cases. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2013, 36, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, K.; Koda, M.; Takahashi, H.; Sakuma, T.; Inada, T.; Kamiya, K.; Ota, M.; Maki, S.; Okawa, A.; Takahashi, K. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor attenuates spinal cord injury-induced mechanical allodynia in adult rats. J. Neurol. Sci. 2015, 355, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamiya, K.; Koda, M.; Furuya, T.; Kato, K.; Takahashi, H.; Sakuma, T.; Inada, T.; Ota, M.; Maki, S.; Okawa, A. Neuroprotective therapy with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in acute spinal cord injury: A comparison with high-dose methylprednisolone as a historical control. Eur. Spine J. 2015, 24, 963–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, K.; Yamazaki, M.; Okawa, A.; Furuya, T.; Sakuma, T.; Takahashi, H.; Kamiya, K.; Inada, T.; Takahashi, K.; Koda, M. Intravenous administration of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor for treating neuropathic pain associated with compression myelopathy: A phase I and IIa clinical trial. Eur. Spine J. 2013, 22, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okurowska-Zawada, B.; Kułak, W.; Sienkiewicz, D.; Paszko-Patej, G.; Dmitruk, E.; Kalinowska, A.; Wojtkowski, J.; Korzeniecka–Kozerska, A. Safety and efficacy of granulocyte colony stimulating factor in a patient with tetraplegia caused by cervical hyperextension injury: A case report. Prog. Health Sci. 2014, 4, 181–184. [Google Scholar]

- Shiomi, A.; Usui, T.; Mimori, T. GM-CSF as a therapeutic target in autoimmune diseases. Inflamm. Regen. 2016, 36, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiomi, A.; Usui, T. Pivotal roles of GM-CSF in autoimmunity and inflammation. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 568543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, J.; Marvin, J.C.; Vaughn, B.; Andarawis-Puri, N. Innate tissue properties drive improved tendon healing in MRL/MpJ and harness cues that enhance behavior of canonical healing cells. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 8341–8356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sadi, O.; Schulze-Tanzil, G.; Kohl, B.; Lohan, A.; Lemke, M.; Ertel, W.; John, T. Tenocytes, pro-inflammatory cytokines and leukocytes: A relationship? Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2011, 1, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Ohls, R.K.; Maheshwari, A. Hematology, Immunology and Infectious Disease: Neonatology Questions and Controversies: Expert Consult-Online and Print; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, F.; Wang, J.; Tang, H.; Huang, P.; Liu, J.; He, G.; Zhou, M.; Tao, X.; Tang, K. VEGF promotes tendon regeneration of aged rats by inhibiting adipogenic differentiation of tendon stem/progenitor cells and promoting vascularization. FASEB J. 2022, 36, e22433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussche, L.; Van de Walle, G.R. Peripheral Blood-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Promote Angiogenesis via Paracrine Stimulation of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Secretion in the Equine Model. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2014, 3, 1514–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganath, S.H.; Levy, O.; Inamdar, M.S.; Karp, J.M. Harnessing the mesenchymal stem cell secretome for the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 10, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shokry, M.; Mostafo, A.; Tohamy, A.; El-Sharkawi, M. Autologous mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of acute superficial digital flexor tendonitis in athletic horses-A clinical study of 1 5 cases. Pferdeheilkunde 2020, 36, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.K.; Cauvin, E.R. Ultrasonography of the Metacarpus and Metatarsus. In Atlas of Equine Ultrasonography; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 73–105. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, J.L.; Evans, R.; Conzemius, M.G.; Lascelles, B.D.X.; McIlwraith, C.W.; Pozzi, A.; Clegg, P.; Innes, J.; Schulz, K.; Houlton, J. Proposed definitions and criteria for reporting time frame, outcome, and complications for clinical orthopedic studies in veterinary medicine. Vet. Surg. 2010, 39, 905–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatab, S.; van Osch, G.; Kops, N.; Bastiaansen-Jenniskens, Y.; Bos, K.; Verhaar, J.; Bernsen, M.; Buul, G. Mesenchymal stem cell secretome reduces pain and prevents cartilage damage in a murine osteoarthritis model. Eur. Cells Mater. 2018, 36, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.-N.; Rong, X.; Yang, L.-M.; Hua, W.-Z.; Ni, G.-X. Advances in Stem Cell Therapies for Rotator Cuff Injuries. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 866195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltrami, A.P.; Cesselli, D.; Bergamin, N.; Marcon, P.; Rigo, S.; Puppato, E.; D’Aurizio, F.; Verardo, R.; Piazza, S.; Pignatelli, A. Multipotent cells can be generated in vitro from several adult human organs (heart, liver, and bone marrow). Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 2007, 110, 3438–3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riekstina, U.; Cakstina, I.; Parfejevs, V.; Hoogduijn, M.; Jankovskis, G.; Muiznieks, I.; Muceniece, R.; Ancans, J. Embryonic stem cell marker expression pattern in human mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow, adipose tissue, heart and dermis. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2009, 5, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, S.J.; Liu, K.; Rameshwar, P. Functional similarities among genes regulated by OCT4 in human mesenchymal and embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 2007, 25, 3143–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Muneta, T.; Morito, T.; Mochizuki, T.; Sekiya, I. Autologous synovial fluid enhances migration of mesenchymal stem cells from synovium of osteoarthritis patients in tissue culture system. J. Orthop. Res. 2008, 26, 1413–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamm, J.L.; Riley, C.B.; Parlane, N.; Gee, E.K.; McIlwraith, C.W. Interactions between allogeneic mesenchymal stromal cells and the recipient immune system: A comparative review with relevance to equine outcomes. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 7, 617647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbath, A.C.; Dow, S.W.; McIlwraith, C.W.; Goodrich, L.R. Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of musculoskeletal disease in horses: Relative merits of allogeneic versus autologous stem cells. Equine Vet. J. 2020, 52, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zhao, H.; Cheng, L.; Wang, B. Allogeneic vs. autologous mesenchymal stem/stromal cells in their medication practice. Cell Biosci. 2021, 11, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galipeau, J.; Krampera, M.; Barrett, J.; Dazzi, F.; Deans, R.J.; DeBruijn, J.; Dominici, M.; Fibbe, W.E.; Gee, A.P.; Gimble, J.M. International Society for Cellular Therapy perspective on immune functional assays for mesenchymal stromal cells as potency release criterion for advanced phase clinical trials. Cytotherapy 2016, 18, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, P.; Maffulli, N.; Rolf, C.; Smith, R. What are the validated animal models for tendinopathy? Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sport. 2011, 21, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Score | Clinical implication |

|---|---|---|

| AAEP Grading | 0 | No Lameness |

| 1 | Lameness not consistent | |

| 2 | Lameness consistent under certain circumstances | |

| 3 | Lameness consistently observable on a straight line. | |

| 4 | Obvious lameness at walk: marked nodding or shortened stride | |

| 5 | Minimal weight bearing lameness in motion or at rest | |

| Flexion Test | 0 | No flexion response |

| 1 | Mild flexion response | |

| 2 | Moderate flexion response | |

| 3 | Severe flexion response | |

| Pain to pressure | 0 | No pain to pressure |

| 1 | Mild pain to pressure | |

| 2 | Moderate pain to pressure | |

| 3 | Severe pain to pressure |

| Marker | Type/Clone | Supplier | Dilution / Incubation period | Antigen unmasking | Positive control | Cells of interest | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oct-4 | Polyclonal | Abcam | 1/100 ON |

RS/WB | Canine mast cell tumour | Stem cells | Ab18976 |

| Nanog | Clone Mab | ABGENT | 1/10 ON |

RS/WB | Canine testicular carcinoma | Stem cells | AM1486b |

| c-Kit (CD117) | Polyclonal | Dako Denmark | 1/450 ON |

RS/WB | Canine mast cell tumour | Stem cells | A4502 |

| Lysozyme | Polyclonal | Dako Denmark | 1/400 ON |

RS/WB | Canine synovial membrane | Synovial cells | A0099 |

| Vimentin | Clone V9 | Dako Denmark | 1/500 ON |

RS/WB | Canine mammary gland | Non-epithelial cells | M0725 |

| Pan-cytokeratin | Cocktail AE1/AE3 | Thermo Scientific | 1/300 ON |

RS/WB | Canine mammary gland | Epithelial cells | M3-343-P1 |

| GFAP | Polyclonal | Merck Millipore | 1/2000 ON |

RS/WB | Mouse brain tissue | Neuronal cells | AB5804 |

| Sinaptophysine | Clone SP11 | Thermo Scientific | 1/150 ON |

RS/WB | Mouse brain tissue | Neuronal cells | RM-9111-S |

| CD31 | Clone JC70A | Dako Denmark | 1/50 ON |

Pepsine | Canine spleen | Platelet endothelial cells | M0823 |

| Lesion type | Nº clinical cases | Total number (2019) |

| Tendonitis | 16 |

20 |

| Desmitis | 4 |

| Week | Exercise |

|---|---|

| 0-2 | 2 days: stall confinement Handwalk: 10 min Day 15: new treatment |

| 3-4 | 2 days: stall confinement Handwalk: 10 min VET-CHECK – day 30 |

| 5 | Handwalk: 15 min |

| 6 | Handwalk: 20 min VET-CHECK – day 45 |

| 7 | Handwalk: 25 min |

| 8 | Handwalk: 30 min VET-CHECK – day 60 |

| 9-10 | Handwalk: 30 min + 5min trot |

| 11-12 | Handwalk: 30 min + 10 min trot VET-CHECK - day 90 |

| P4 | Cytogenetic analysis | P7 |

| 36% | Normal cells 64, XY |

32% |

| 4% | Tetraploid cells 128 XXYY |

8% |

| 60% | Aneuploid cells: Hipoploidy 54-63 Hiperploidy 71 |

60% |

|

56% 4% |

56% 4% |

| Equine Patient | Lesion: Tendonitis / Desmitis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | Sex | Age (yo) |

SM | Structure | Type | Limb | Evolution |

| 1 | M | 22 | SJ | SDFT DDFT |

Acute | LF | Favorable in 30 days |

| 2 | F | 5 | SJ | SDFT | Acute | RH | Favorable in 30 days |

| 3 | F | 14 | SJ | SDFT | Chronic | RF | Favorable in 30 days |

| 4 | M | 8 | SJ | SDFT | Acute | RF | Favorable in 30 days |

| 5 | M | 7 | SJ | LB SL | Acute | LF | Favorable in 30 days |

| 6 | M | 13 | Lsr | SDFT DDFT SL |

Chronic | RH | Tendons: favorable evolution in 30 days; SL in 90 days. |

| 7 | M | 15 | SJ | SFDT | Acute | RF | Favorable in 90 days |

| 8 | M | 11 | SJ | SDFT | Acute | RF | Favorable in 30 days |

| 9 | F | 10 | SJ | SDFT SL |

Acute | RF | Favorable in 30 days |

| 10 | M | 9 | SJ | SDFT | Acute | LF | Favorable in 30 days |

| 11 | F | 10 | SJ | SDFT | Acute | RF | Favorable in 30 days |

| 12 | M | 12 | Dre | SDFT | Acute | LF | Favorable in 30 days |

| 13 | M | 14 | SJ | SL | Acute | LF | Favorable in 30 days |

| 14 | M | 7 | SJ | SDFT | Acute | RF | Favorable in 30 days |

| 15 | M | 12 | SJ | SFDT | Acute | LF | Favorable in 30 days |

| 16 | F | 6 | SJ | SFDT | Acute | RF | Favorable in 30 days |

| Patient ID |

Day | Structure | Location | Cross Sectional Area | Longitudinal Fiber Pattern (%) |

Assessment Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | SDFT DDFT |

1A-1B 1A-1B |

1 1 |

1 1 |

|

| 15 | SDFT DDFT |

1A-1B 1A-1B |

1 1 |

1 1 |

||

| 30 | SDFT DDFT |

1A-1B 1A-1B |

0 0 |

0 0 |

Full function | |

| 2 | 1 | SDFT | 1A-1B | 1 | 1 | |

| 15 | SDFT | 1A-1B | 1 | 1 | ||

| 30 | SDFT | 1A-1B | 0 | 0 | Full function | |

| 3 | 1 | SDFT | 1A-1B | 1 | 1 | |

| 15 | SDFT | 1A-1B | 1 | 1 | ||

| 30 | SDFT | 1A-1B | 0 | 0 | Full function | |

| 4 | 1 | SDFT | 1A-1B | 2 | 2 | |

| 15 | SDFT | 1A-1B | 2 | 2 | ||

| 30 | SDFT | 1A-1B | 0 | 0 | Full function | |

| 5 | 1 | LB SL | 3A-3B | 2 | 2 | |

| 15 | LB SL | 3A-3B | 2 | 2 | ||

| 30 | LB SL | 3A-3B | 0 | 0 | Full function | |

| 6 | 1 | SDFT DDFT SL |

2A-2B 2A-2B 2A-2B |

2 2 2 |

2 2 2 |

|

| 15 | SDFT DDFT SL |

2A-2B 2A-2B 2A-2B |

1 1 2 |

1 1 2 |

||

| 30 | SDFT DDFT LS |

2A-2B 2A-2B 2A-2B |

1 1 1 |

1 1 1 |

Unacceptable function. Only at day 90. |

|

| 7 | 1 | SDFT | 2A-2B | 3 | 3 | |

| 15 | SDFT | 2A-2B | 3 | 3 | ||

| 30 | SDFT | 2A-2B | 2 | 2 | Unacceptable function. | |

| 8 | 1 | SDFT | 2A-2B | 2 | 3 | |

| 15 | SDFT | 2A-2B | 2 | 2 | ||

| 30 | SDFT | 2A-2B | 0 | 0 | Full function | |

| 9 | 1 | SDFT | 2A-2B | 2 | 1 | |

| 15 | SDFT | 2A-2B | 1 | 1 | ||

| 30 | SDFT | 2A-2B | 0 | 0 | Full function | |

| 10 | 1 | SDFT | 1A-1B | 3 | 3 | |

| 15 | SDFT | 1A-1B | 2 | 2 | ||

| 30 | SDFT | 1A-1B | 0 | 0 | Full Function | |

| 11 | 1 | SDFT | 1A-1B | 2 | 2 | |

| 15 | SDFT | 1A-1B | 2 | 2 | ||

| 30 | SDFT | 1A-1B | 0 | 0 | Full function | |

| 12 | 1 | SDFT | 2A-2B | 1 | 1 | |

| 15 | SDFT | 2A-2B | 1 | 1 | ||

| 30 | SDFT | 2A-2B | 0 | 0 | Full function | |

| 13 | 1 | SL | 1A-1B | 2 | 2 | |

| 15 | SL | 1A-1B | 1 | 1 | ||

| 30 | SL | 1A-1B | 0 | 0 | Full function | |

| 14 | 1 | SDFT | 2A-2B | 1 | 1 | |

| 15 | SDFT | 2A-2B | 1 | 1 | ||

| 30 | SDFT | 2A-2B | 0 | 0 | Full function | |

| 15 | 1 | SDFT | 2A-2B | 2 | 2 | |

| 15 | SDFT | 2A-2B | 2 | 2 | ||

| 30 | SDFT | 2A-2B | 0 | 0 | Full function | |

| 16 | 1 | SDFT | 2A-2B | 2 | 2 | |

| 15 | SDFT | 2A-2B | 2 | 2 | ||

| 30 | SDFT | 2A-2B | 0 | 0 | Full function |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).