Submitted:

01 March 2023

Posted:

09 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Conceptual Motivations

Historical developments

Guerrilla Marketing: Concept

Goals of Guerrilla Marketing:

Representative examples

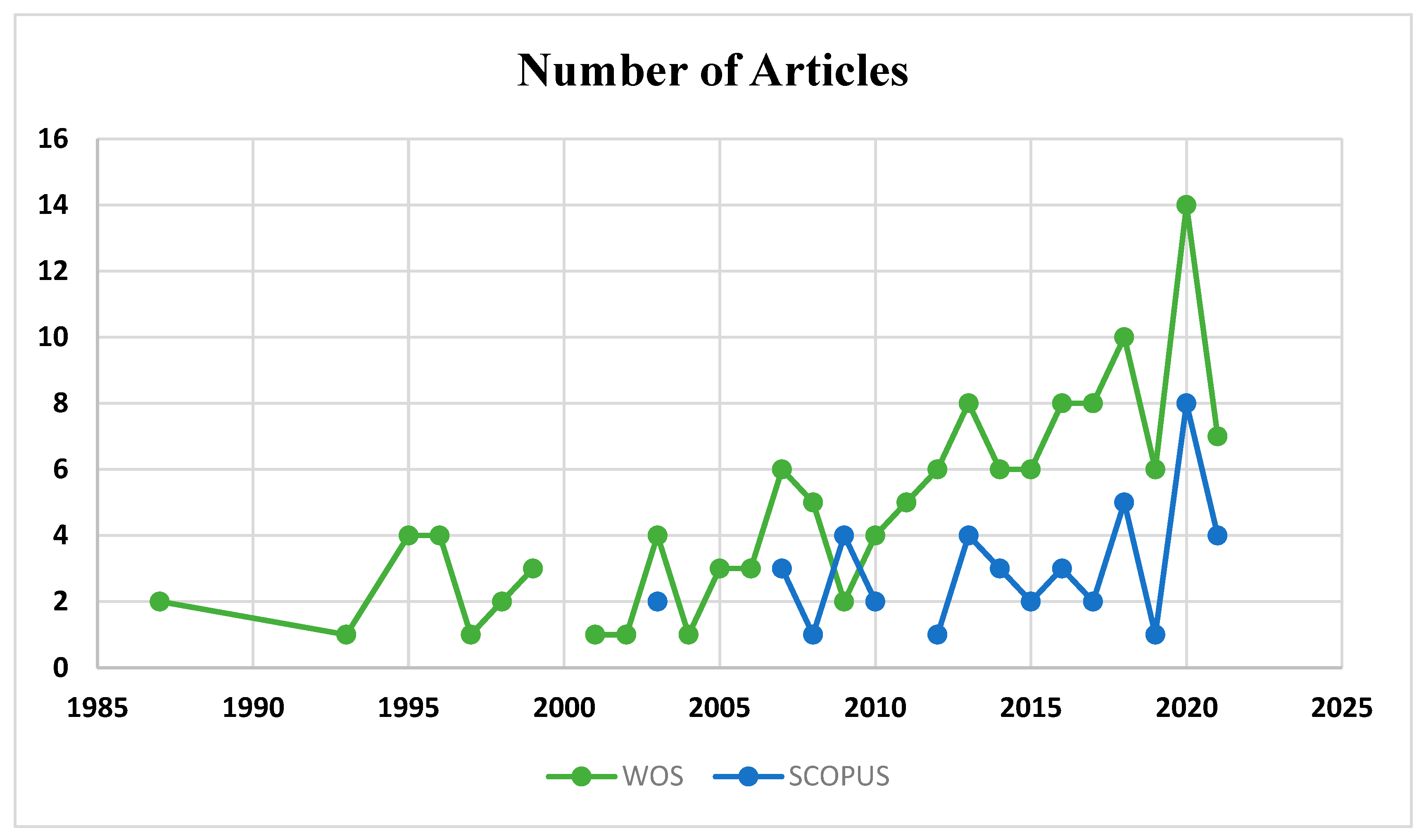

Methodology

| Types of Marketing Guerilla | Authors/Articles | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Viral Marketing | Hoyer and Brown (1990); Domingos (2005); Lindgreen and Vanhamme, (2005); Kraus et al., (2010); Hutter and Hoffmann (2011); Sajoy, (2013); Fong and Yazdanifard (2014); Kadyan and Aswal (2014); Sharma and Sharma (2015); Katke (2016); Gupta and Singh (2017); Ahmed et al. (2020); Khosravi and Ranjbar (2020); Soommro et al. (2021); Farooqui, (2021). | 15 |

| Ambient Marketing | Holt (2002); Hutter and Hoffmann (2011); Hutter and Hoffmann (2014); Sajoy, (2013); Sharma and Sharma (2015); Farooqui, R. (2021); Shelton and Warner (2016); Semenescu and Martinsson, (2012); Turk et al. (2016); | 9 |

| Stealth Marketing | Kaikati and Kaikati (2004); Rotfeld (2008); Swanepoel et al. (2009); Roy and Chattopadhyay (2010); Sharma and Sharma (2015); Walia and Singla (2017); Farooqui, R. (2021). | 7 |

| Street Marketing | Levinson (1984); Donthu et al. (1993); Bhargava and Donthu (1999); Shankar and Horton (1999); Donthu et al. (2003); Moor (2003); Veloutsou and O’Donnell (2005); Taylor et al. (2006); Krautsack (2007); Levinson (2007); Gambetti (2010); Hutter and Hoffmann (2011); Wilson and Till (2011); Roux et al. (2013); Grant (2014); Saucet and Cova (2015); Dinh and Mai (2015); Iqbal and Lohdi (2015); Rauwers and van Noort, (2016); Ahmed et al. (2020); Roux and Saucet (2020); Farooqui, R. (2021). | 22 |

| Ambush Marketing | Sandler and Shani (1989,1993); IOC (1993); Meenaghan (1994); Payne (1998); Meenaghan (1998); Shani and Sandler (1998); Lyberger and McCarthy (2001); Crow and Hoek (2003); Crompton (2004); Hartland and Skinner (2005); Séguin et al. (2005); Bhattacharjee and Rao (2006); McKelvey and Grady (2008); Séguin and O’Reilly (2008); Ellis et al. (2011); Gombeski et al. (2011); Chadwick and Burton’s (2011); Ujwala (2012); Hartland and Williams-Burnett (2012); Sajoy, (2013); Dickson et al., 2015); Sharma and Sharma (2015); Nufer (2016); Khosravi and Ranjbar (2020); Soomro et al. (2021); Farooqui, R. (2021). | 27 |

- Data retrieval: documents were exported from the Web of Science

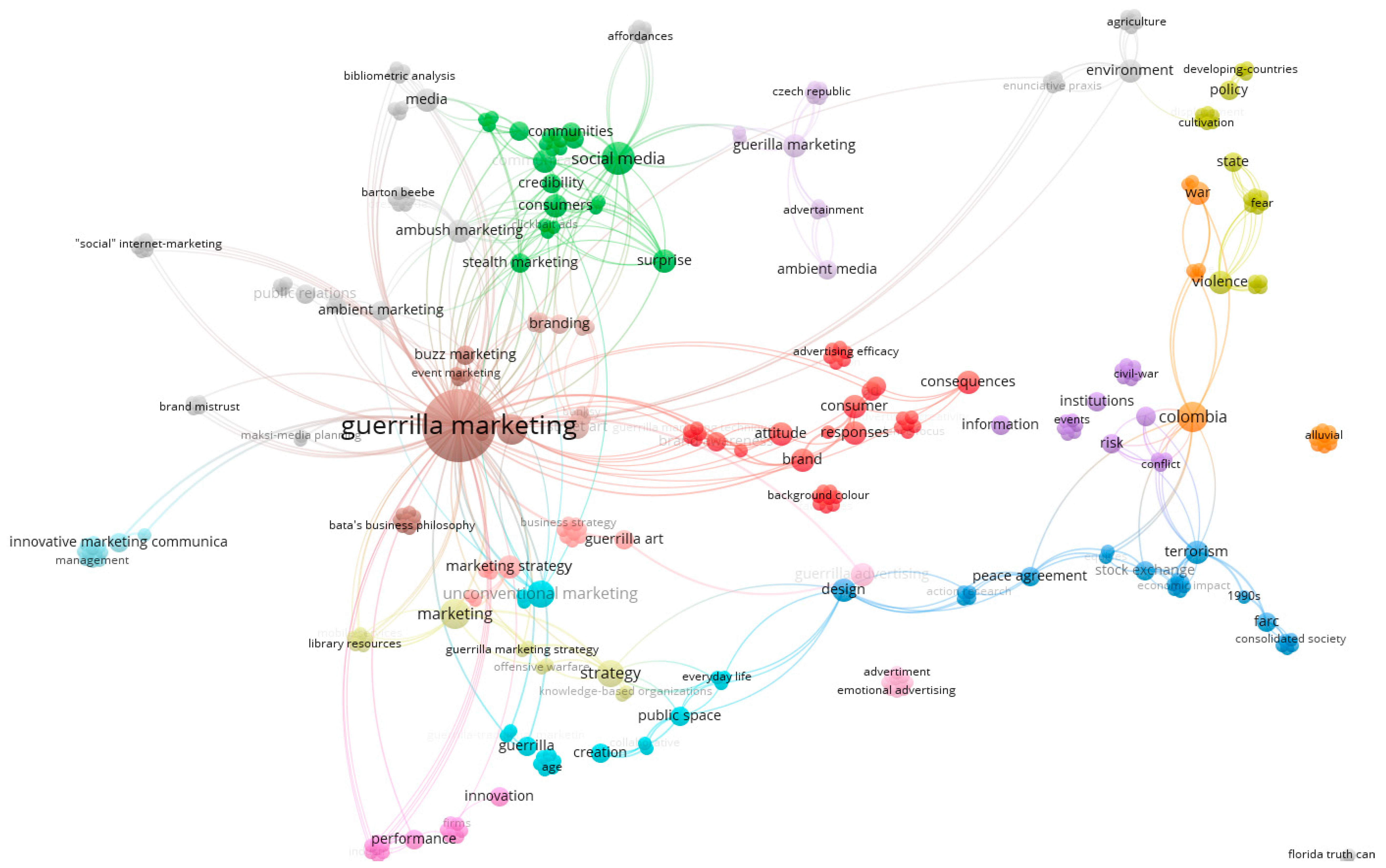

- Prepressing: data reduction and keyword grouping.

- Network extraction: co-occurrence of keywords.

- Normalization: equivalence index and association strength.

- Mapping: clustering

- Analysis and Visualization: keyword projection.

- Interpretation: Discussion and interpretation of the generated data.

- Stealth is the essence of market entry;

- What’s up-front is free: payment comes later;

- Let the behaviors of the target community carry the message;

- Look like a host, not a virus;

- Exploit the strength of weak ties;

- Invest to reach the tipping point.

Ambient Marketing

Stealth Marketing

Street Marketing

Ambush Marketing

Variables of interest in Guerrilla Marketing

Surprise effect

Emotional Arousal

Humor

Information Content/ Clarity

Guerrilla Mobile

Brand Awareness

Creativity/ Credibility

WOM/E-WOM

Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Agreement

References

- Adeleye, A., & Fagboun, L. (2014). Guerrilla marketing: A sustainable tool for entrepreneurs and marketing practitioners. Ondo Journal of Science and Science Education, Ondo, 4 (1), 44, 54.

- Ahmad, N., Ahmed, R., Jahangir, M., Moghani, G., Shamim, H., & Baig, R. (2014, August). Impacts of Guerrilla advertising on consumer buying behavior. In Information and Knowledge Management (Vol. 4, No. 8).

- Ahmed, R. R., Qureshi, J. A., Štreimikienė, D., Vveinhardt, J., & Soomro, R. H. (2020). Guerrilla marketing trends for sustainable solutions: Evidence from SEM-based multivariate and conditional process approaches. Journal of business economics and management, 21(3), 851-871. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R. R., Vveinhardt, J., & Streimikiene, D. (2017). Interactive digital media and impact of customer attitude and technology on brand awareness: evidence from the South Asian countries. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 18(6), 1115-1134. [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, R. D., Michels, T. A., Walker, M. M., & Weissbuch, M. (2007). Teen perceptions of disclosure in buzz marketing. Journal of Consumer Marketing. [CrossRef]

- Al Halbusi, H., & Tehseen, S. (2018). The effect of electronic wordof-mouth (EWOM) on brand image and purchase intention: A conceptual paper. Socioeconomic Challenges, 2(3), 83-94. https://doi.org/10.21272/sec.3 (2).83-94.2018. [CrossRef]

- Al Mana, A. M., & Mirza, A. A. (2013). The impact of electronic word of mouth on consumers’ purchasing decisions. International Journal of Computer Applications, 82(9).

- Ang, S. H., Leong, S. M., Lee, Y. H., & Lou, S. L. (2014). Necessary but not sufficient: Beyond novelty in advertising creativity. Journal of Marketing Communications, 20(3), 214-230. [CrossRef]

- Aprilia, F., & Kusumawati, A. (2021). Influence of Electronic Word of Mouth on Visitor’s Interest to Tourism Destinations. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics, and Business, 8(2), 993-1003.

- Armstrong, G., & Kotler, P. (2005). Marketing: an introduction (7th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Arndt, J. (1967). Role of product-related conversations in the diffusion of a new product. Journal of marketing Research, 4(3), 291-295. [CrossRef]

- Awad, N. F., & Ragowsky, A. (2008). Establishing trust in electronic commerce through online word of mouth: An examination across genders. Journal of management information systems, 24(4), 101-121. [CrossRef]

- Ay, C., Aytekin, P., & Nardali, S. (2010). Guerrilla marketing communication tools and ethical problems in guerilla advertising. American Journal of Economics and Business Administration, 2(3), 280-286. [CrossRef]

- Ay, C., & Unal, A. (2002). New marketing approach for SMEs: Guerilla marketing. Journal of Management and Economics, 9, 75-85.

- Baltes, G., & Leibing, I. (2008). Guerrilla marketing for information services? New Library World, 16. 109(1/2), 46-55. [CrossRef]

- Berlyne, D.E. (1960), Conflict, Arousal and Curiosity, MacGraw-Hill, New York, NY. [CrossRef]

- Besemer, S., & O’Quin, K. (1986). Analyzing Creative Products: Refinement and test of a judging instrument. Journal of Creative Behavior, 20(2), 115-26. [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, M., & Donthu, N. (1999). Sales response to outdoor advertising. Journal of Advertising Research, 39(4), 7-7.

- Bhattacharjee, S., & Rao, G. (2006). Tackling ambush marketing: The need for regulation and analysing the present legislative and contractual efforts. Sport in Society, 9(1), 128-149. [CrossRef]

- Bigat, E. C. (2012). Guerrilla advertisement and marketing. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 51, 1022-1029. [CrossRef]

- Burke, R. R., & Srull, T. K. (1988). Competitive interference and consumer memory for advertising. Journal of consumer research, 15(1), 55-68. [CrossRef]

- Callon, M., Courtial, J. P., & Laville, F. (1991). Co-word analysis as a tool for describing the network of interactions between basic and technological research: The case of polymer chemistry. Scientometrics, 22(1), 155-205. [CrossRef]

- Caudron, S. (2001), “Guerrilla tactics”, Industry Week, Vol. 250 No. 10, pp. 52-6.

- Castillo, C., Mendoza, M., & Poblete, B. (2013). Predicting information credibility in time-sensitive social media. Internet Research. [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, S., & Burton, N. (2011). The evolving sophistication of ambush marketing: A typology of strategies. Thunderbird International Business Review, 53(6), 709-719. [CrossRef]

- Cheema, A., & Kaikati, A. M. (2010). The effect of need for uniqueness on word of mouth. Journal of Marketing Research, 47(3), 553-563. [CrossRef]

- Chan, F. F. Y. (2011). The use of humor in television advertising in Hong Kong.

- Chen, C. F., & Chang, Y. Y. (2008). Airline brand equity, brand preference, and purchase intentions—The moderating effects of switching costs. Journal of Air Transport Management, 14(1), 40-42. [CrossRef]

- Chi, H. K.; Yeh, H. R. and Yang, Y. T. (2009), “The Impact of Brand Awareness on Consumer Purchase Intention: The Mediating Effect of Perceived Quality and Brand Loyalty”, The Journal of International Management Studies, 4(1), 135-144. [CrossRef]

- Chung, C. M., & Tsai, Q. (2009). The effects of regulatory focus and tie strength on word-of-mouth behavior. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics. [CrossRef]

- Chung, N., Han, H., & Koo, C. (2015). Adoption of travel information in user-generated content on social media: the moderating effect of social presence. Behavior & Information Technology, 34(9), 902-919. [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M. J., López-Herrera, A. G., Herrera-Viedma, E., & Herrera, F. (2011). An approach for detecting, quantifying, and visualizing the evolution of a research field: A practical application to the fuzzy sets theory field. Journal of informetrics, 5(1), 146-166. [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M.J., López-Herrera, A.G., Herrera-Viedma, E. and Herrera, F. (2012), “SciMAT: a new science mapping analysis software tool”, Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, Vol. 63 No. 8, pp. 1609-1630, doi: 10.1002/asi.22688. [CrossRef]

- Coulter, N., Monarch, I., & Konda, S. (1998). Software engineering as seen through its research literature: A study in co-word analysis. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 49(13), 1206-1223. [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J. L. (2004). Sponsorship ambushing in sport. Managing Leisure, 9(1), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Cronkhite, G., & Liska, J. (1976). A critique of factor analytic approaches to the study of credibility. Communications Monographs, 43(2), 91-107. [CrossRef]

- Crow, D., & Hoek, J. (2003). Ambush marketing: A critical review and some practical advice. Marketing Bulletin, 14(1), 1-14.

- Dahlén, M. (2005). The medium as a contextual cue: Effects of creative media choice. Journal of advertising, 34(3), 89-98. [CrossRef]

- Dahlén, M., Rosengren, S., & Törn, F. (2008). Advertising creativity matters. Journal of Advertising Research, 48(3), 392–403. doi:10.2501/s002184990808046x. [CrossRef]

- Davis, S., & Davis, F. (2021). The Effect of Guerrilla Marketing On Company Share Prices: An Event Study Analysis. Journal of Advertising Research, 61(3), 346-361. [CrossRef]

- Derbaix, C., & Pham, M. T. (1991). Affective reactions to consumption situations: A pilot investigation. Journal of economic Psychology, 12(2), 325-355. [CrossRef]

- De Matos, C. A., & Rossi, C. A. V. (2008). Word-of-mouth communications in marketing: a meta-analytic review of the antecedents and moderators. Journal of the Academy of marketing science, 36(4), 578-596. [CrossRef]

- Dholakia, R. R., & Dholakia, N. (2004). Mobility and markets: emerging outlines of m-commerce. Journal of Business research, 57(12), 1391-1396. [CrossRef]

- Dickson, G., Naylor, M., & Phelps, S. (2015). Consumer attitudes towards ambush marketing. Sport Management Review, 18(2), 280-290. [CrossRef]

- Dinh, T. D., & Mai, K. N. (2015). Guerrilla marketing’s effects on Gen Y’s word-of-mouth intention–a mediation of credibility. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics. [CrossRef]

- Domingos, P. (2005). Mining social networks for viral marketing. IEEE Intelligent Systems, 20(1), 80-82.

- Donthu, N., Cherian, J., & Bhargava, M. (1993). Factors influencing recall of outdoor advertising. Journal of advertising research, 33(3), 64-73.

- Drüing, A., & Fahrenholz, K. (2008). How and by whom are the evolved success factors of the Guerilla Marketing philosophy from the 1980’s used today and do they stand a chance in the business future? Bachelor thesis, Dept. Business Administration, Saxion Uni., Enschede, The Netherlands.

- Edge, C. (2018). Engage in free and Guerrilla marketing. In Build, run, and sell your apple consulting practice (pp. 199–227). Charles Edge.

- Eisend, M. (2011). How humor in advertising works: A meta-analytic test of alternative models. Marketing letters, 22(2), 115-132. [CrossRef]

- Eisend, M., Plagemann, J., & Sollwedel, J. (2014). Gender roles and humor in advertising: The occurrence of stereotyping in humorous and nonhumorous advertising and its consequences for advertising effectiveness. Journal of advertising, 43(3), 256-273. [CrossRef]

- Elliott, M. (2003). Playing by Mogadishu rules. Time, 161(14), 63-63.

- Ellis, D., Scassa, T., & Séguin, B. (2011). Framing ambush marketing as a legal issue: An Olympic perspective. Sport Management Review, 14(3), 297-308. [CrossRef]

- Erkan, I., & Evans, C. (2016). The influence of eWOM in social media on consumers’ purchase intentions: An extended approach to information adoption. Computers in human behavior, 61, 47-55. [CrossRef]

- Farooqui, R. (2021). The Role of Guerilla Marketing for Consumer Buying Behavior in Clothing Industry of Pakistan using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). South Asian Journal of Management, 15(1), 52-68. [CrossRef]

- Fattal, A. L. (2018). Guerrilla marketing: counterinsurgency and capitalism in Colombia. University of Chicago Press.

- Feldman, L. A. (1995). Valence focus and arousal focus: individual differences in the structure of affective experience. Journal of personality and social psychology, 69(1), 153. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, R. (2008). Word of mouth and viral marketing: taking the temperature of the hottest trends in marketing. Journal of consumer marketing. 25(3):179-182. [CrossRef]

- Fong, K., & Yazdanifard, R. (2014). The review of the two latest marketing techniques; viral marketing and guerrilla marketing which influence online consumer behavior. Global Journal of Management and Business Research. 14 (2-E).

- Furrer, O., Kerguignas, J. Y., Delcourt, C., & Gremler, D. D. (2020). Twenty-seven years of service research: a literature review and research agenda. Journal of Services Marketing, available online ahead of print: Doi: 10.1108/JSM-02-2019-0078. [CrossRef]

- Gambetti, R. C. (2010). Ambient communication: How to engage consumers in urban touch-points. California Management Review, 52(3), 34-51. [CrossRef]

- Gilitwala, B., & Nag, A. K. (2021). Factors influencing youngsters’ consumption behavior on high-end cosmetics in China. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics, and Business, 8(1), 443-450.

- Gokerik, M., Gurbuz, A., Erkan, I., Mogaji, E., & Sap, S. (2018). Surprise me with your ads! The impacts of guerrilla marketing in social media on brand image. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 30(5), 1222-1238. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-10-2017-0257. [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, J., Libai, B., & Muller, E. (2001). Talk of the network: A complex systems look at the underlying process of word-of-mouth. Marketing letters, 12(3), 211-223. [CrossRef]

- Gombeski Jr, W., Wray, T., & Blair, G. (2011). Prepare for the ambush! Marketing health services, 31(2), 24-28.

- Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R. (2019) Exploring the Relationship between Ambient Marketing Practices and Behavioural Intentions.

- Gupta, H., & Singh, S. (2017). Sustainable practices through green guerrilla marketing–an innovative approach. Journal on Innovation and Sustainability RISUS, 8(2), 61-78. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, J. S., Díaz, R. V., & Gutiérrez-Salcedo, M. (2019). The effect of guerrilla marketing strategies on competitiveness: restaurants in Guadalajara, Mexico. Journal of Competitiveness Studies, 27(1), 3-18.

- Grant, P. S. (2016). Understanding branded flash mobs: The nature of the concept, stakeholder motivations, and avenues for future research. Journal of Marketing Communications, 22(4), 349-366. [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D., Gotlieb, J., & Marmorstein, H. (1994). The moderating effects of message framing and source credibility on the price-perceived risk relationship. Journal of consumer research, 21(1), 145-153. [CrossRef]

- Gruber, M. (2004). Marketing in new ventures: theory and empirical evidence. Schmalenbach business review, 56(2), 164-199. [CrossRef]

- Haberland, G. S., & Dacin, P. A. (1992). The development of a measure to assess viewers’ judgments of the creativity of an advertisement: A preliminary study. ACR North American Advances.

- Hafer, C. L., Reynolds, K. L., & Obertynski, M. A. (1996). Message comprehensibility and persuasion: Effects of complex language in counterattitudinal appeals to laypeople. Social Cognition, 14(4), 317-337. [CrossRef]

- Halkias, G., & Kokkinaki, F. (2014). The degree of ad–brand incongruity and the distinction between schema-driven and stimulus-driven attitudes. Journal of Advertising, 43(4), 397-409. [CrossRef]

- Hallisy, B. H. (2006). Taking it to the streets: Steps to an effective and ethical guerilla marketing campaign. Public Relation Tactics, 13(3), 13.

- Hartland, T., & Skinner, H. (2005). What is being done to deter ambush marketing? Are these attempts working? International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship.

- Hartland, T., & Williams-Burnett, N. (2012). Protecting the Olympic brand: Winners and losers. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 20(1), 69-82. [CrossRef]

- Heath, R. (2007). Emotional Persuasion in advertising: A hierarchy-of-processing model. Bath, VB: University of Bath.

- Heper, C. O. (2008). Gerilla Tasarım Bağlamında Gerilla Tasarımın Analizi. Yayınlanmamış Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Eskişehir: Anadolu Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Grafik Ana Bilim Dalı.

- Herbig, P., & Milewicz, J. (1995). To be or not to be... credible that is:: a model of reputation and credibility among competing firms. Marketing Intelligence & Planning.

- Helm, S. (2000). Viral marketing-establishing customer relationships by’word-of-mouse’. Electronic markets, 10(3), 158-161. [CrossRef]

- Henkel. (2006), Fussball-Weltmeisterschaft – Sil unterstützt brasilianische Elf, available at: www.henkel.de/cps/rde/xchg/SID-0AC8330A-0253EF13/henkel_de/hs.xsl/5566_DED_HTML.htm and www.bra-sil.de.

- Herr, P. M., Kardes, F. R., & Kim, J. (1991). Effects of word-of-mouth and product-attribute information on persuasion: An accessibility-diagnosticity perspective. Journal of consumer research, 17(4), 454-462. [CrossRef]

- Holland, D. (2016 April 26). Word of mouth marketing association. https://womma.org/social-media-marketing-word-mouthmarketing/.

- Housholder, E. E., & LaMarre, H. L. (2014). Facebook politics: Toward a process model for achieving political source credibility through social media. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 11(4), 368-382. [CrossRef]

- Hoyer, W. D., & Brown, S. P. (1990). Effects of brand awareness on choice for a common, repeat-purchase product. Journal of consumer research, 17(2), 141-148. [CrossRef]

- Hutter, K., & Hoffmann, S. (2011). Guerrilla marketing: The nature of the concept and propositions for further research. Asian Journal of Marketing, 5(2), 39–54. [CrossRef]

- Hutter, K., & Hoffmann, S. (2014). Surprise, surprise. Ambient media as promotion tool for retailers. Journal of Retailing, 90(1), 93-110. [CrossRef]

- IOC International Olympic Committee (1993) ‘Ambush marketing’, Marketing Matters, Vol. 3, pp.1–8.

- Iqbal, S., & Lohdi, S. (2015). The impacts of guerrilla marketing on consumers’ buying behavior: a case of beverage industry of Karachi. The International Journal of Business & Management, 3(11), 120.

- Isen, A. M., & Shalker, T. E. (1982). The effect of feeling state on evaluation of positive, neutral, and negative stimuli: When you “accentuate the positive,” do you “eliminate the negative”? Social Psychology Quarterly, 45(1), 58–63. https://doi.org/10.2307/3033676. [CrossRef]

- Itti, L., & Baldi, P. (2009). Bayesian surprise attracts human attention. Vision research, 49(10), 1295-1306. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, P.W. & Messick, S. (1967), “The person, the product, and the response: conceptual problems in the assessment of creativity”, in Kagan, J. (Ed.), Creativity and Learning, Beacon Press, Boston, MA, pp. 1-9.

- Jalilvand, M. R., Samiei, N., & Mahdavinia, S. H. (2011). The effect of brand equity components on purchase intention: An application of Aaker’s model in the automobile industry. International business and management, 2(2), 149-158.

- Jin, X. L., Cheung, C. M., Lee, M. K., & Chen, H. P. (2009). How to keep members using the information in a computer-supported social network. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(5), 1172-1181. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, J. K. (2004). In your face: How American marketing excess fuels anti-Americanism. Financial Times/Prentice Hall.

- K. Zerr. (June 2018). Guerilla Marketing in der Kommunikation: Kennzeichen, Mechanismen und Gefahren. [Online]. Available: http://www.guerilla-marketing-portal.de/doks/pdf/Guerilla-Zerr.pdf.

- Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2011). Two hearts in three-quarter time: How to waltz the social media/viral marketing dance. Business horizons, 54(3), 253-263. [CrossRef]

- Kadyan, A., & Aswal, C. (2014). New buzz in marketing: go viral. International Journal of Innovative research & Development, 2(1), 294-297.

- Kaikati, A. M., & Kaikati, J. G. (2004). Stealth marketing: How to reach consumers surreptitiously. California management review, 46(4), 6-22. [CrossRef]

- Kamau, S. M., & Bwisa, H. M. (2013). Effects of guerilla marketing in growth of beauty shops: Case study of Matuu Town, Machakos County, Kenya. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 3(2), 279.

- Katke, K. (2016). Effective marketing communication: a special reference to social media marketing. Asia Pacific Journal of Research, I (XLI), 151-157.

- Keller, K. L., Parameswaran, M. G., & Jacob, I. (2011). Strategic brand management: Building, measuring, and managing brand equity. Pearson Education India.

- Kepes, S., Banks, G. C., McDaniel, M., & Whetzel, D. L. (2012). Publication bias in the organizational sciences. Organizational Research Methods, 15(4), 624–662. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. J., Chung, N., Lee, C. K., & Preis, M. W. (2016). Dual-route of persuasive communications in mobile tourism shopping. Telematics and Informatics, 33(2), 293-308. [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, A., & Ranjbar, A. (2020). The Role of Guerrilla Marketing in Consumer Purchase Behavior of Electronic Products. (Case: Gen Y’s Customers in Tehran). Brand Management, 7(2), 151-182.

- Koeck, R., & Warnaby, G. (2014). Outdoor advertising in urban context: spatiality, temporality and individuality. Journal of Marketing Management, 30(13-14), 1402-1422. [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P., & Keller, K.L. (2016). Marketing Managemet. Edisi 15 Global Edition. Pearson.

- Kozinets, R. V., De Valck, K., Wojnicki, A. C., & Wilner, S. J. (2010). Networked narratives: Understanding word-of-mouth marketing in online communities. Journal of marketing, 74(2), 71-89. [CrossRef]

- Kuttelwascher, F. (2006). Mao für Kapitalisten. Zeitschrift für Marketing, 49(7), 30-34.

- Kraus, S., Harms, R., & Fink, M. (2010). Entrepreneurial marketing: moving beyond marketing in new ventures. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 11(1), 19-34. [CrossRef]

- Krautsack, D. (2007). Ambient media-how the world is changing. Admap, 488, 24.

- Langer, R. (2006). Stealth marketing communications: is it ethical? In Strategic CSR communication (pp. 107-134). Djøf Forlag.

- Levinson, J. C. (2007). Guerrilla Marketing: Easy and Inexpensive Strategies for Making Big Profits from Your Small Business, pp 6-10.

- Levinson, J.C., Adkins, F. and Forbes, C. (2010), Guerrilla Marketing for Nonprofits, Entrepreneurs Media, Irvine, CA.

- Levinson, C. J. (1984). Guerrilla marketing: secrets of making big profit from your small business(3rd ed.). Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Lindgreen, A., & Vanhamme, J. (2005). Viral marketing: The use of surprise. Advances in electronic marketing, 122-138.

- Ling, K. C., Piew, T. H., & Chai, L. T. (2010). The determinants of consumers’ attitude towards advertising. Canadian social science, 6(4), 114-126.

- Liu, B. (2020). Sentiment analysis: Mining opinions, sentiments, and emotions. Cambridge University Press.

- López-Duarte, C., González-Loureiro, M., Vidal-Suárez, M. M., & González-Díaz, B. (2016). International strategic alliances and national culture: Mapping the field and developing a research agenda. Journal of World Business, 51(4), 511–524. [CrossRef]

- Luxton, S., & Drummond, L. (2000). What is this thing called ‘Ambient Advertising’. Visionary Marketing for the 21st Century: Facing the Challenge, ANZMAC, 735.

- Lyberger, M. R., & McCarthy, L. (2001). An assessment of consumer knowledge of, interest in, and perceptions of ambush marketing strategies. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 10(3), 130-137.

- Ma, T. J., & Atkin, D. (2017). User generated content and credibility evaluation of online health information: a meta analytic study. Telematics and Informatics, 34(5), 472-486. [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S. B., & Lutz, R. J. (1989). An empirical examination of the structural antecedents of attitude toward the ad in an advertising pretesting context. Journal of marketing, 53(2), 48-65. [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, L., & Amulya, M. (2013). Impact of brand awareness on purchase intention: A study on mobile phone users in Mysore. EXCEL International Journal of Multidisciplinary Management Studies, 3(4), 106-116.

- Malik, M. E., Ghafoor, M. M., Hafiz, K. I., Riaz, U., Hassan, N. U., Mustafa, M., & Shahbaz, S. (2013). Importance of brand awareness and brand loyalty in assessing purchase intentions of consumer. International Journal of business and social science, 4(5).

- Mandler, G. (1995), “Origins and consequences of novelty”, in Smith, S.M. , Ward, T.B. and Finkle, R.A. (Eds), The Creative Cognitive Approach , MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp. 9-25.

- Martin, K. D., & Smith, N. C. (2008). Commercializing social interaction: The ethics of stealth marketing. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 27(1), 45-56. [CrossRef]

- Maru File, K., Cermak, D. S., & Alan Prince, R. (1994). Word-of-mouth effects in professional services buyer behaviour. Service Industries Journal, 14(3), 301-314. [CrossRef]

- Marsden, P. (2006), “Introduction and summary”, in Kirby, J. and Marsden, P. (Eds), Connected Marketing: The Viral, Buzz, and Word of Mouth Revolution, Elsevier, Oxford, pp. 16-37.

- McKelvey, S., & Grady, J. (2008). Sponsorship program protection strategies for special sport events: Are event organizers outmaneuvering ambush marketers? Journal of Sport Management, 22(5), 550-586. [CrossRef]

- McKnight, H., & Kacmar, C. (2006, January). Factors of information credibility for an internet advice site. In Proceedings of the 39th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS’06) (Vol. 6, pp. 113b-113b). IEEE.

- McQuarrie, E. F., & Mick, D. G. (1992). On resonance: A critical pluralistic inquiry into advertising rhetoric. Journal of consumer research, 19(2), 180-197. [CrossRef]

- Meenaghan, T. (1998). Ambush marketing: Corporate strategy and consumer reaction. Psychology & Marketing, 15(4), 305-322. [CrossRef]

- Meenaghan, T. (1994). Point of view: ambush marketing: immoral or imaginative practice? Journal of Advertising Research, 34(5), 77-89.

- Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). An Approach to Environmental Psychology. (MIT Press: Cambridge, MA.).

- Mercanti-Guérin, M. (2008). Consumers’ perception of the creativity of advertisements: development of a valid measurement scale. Recherche et Applications en Marketing (English Edition), 23(4), 97-118. [CrossRef]

- Moor, E. (2003). Branded spaces: the scope of ‘new marketing’. Journal of Consumer Culture, 3(1), 39-60. [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, M. A. (2011). Analysis of Brand Awareness and Guerrilla Marketing In Iranian SME.

- Muehling, D. D., & Laczniak, R. N. (1988). Advertising’s immediate and delayed influence on brand attitudes: Considerations across message-involvement levels. Journal of advertising, 17(4), 23-34. [CrossRef]

- Naeini, A., Azali, P. R., & Tamaddoni, K. S. (2015). Impact of brand equity on purchase intention and development, brand preference and customer willingness to pay higher prices. Management and Administrative Sciences Review, 4(3), 616-626.

- Nagar, K. (2015). Consumers’ evaluation of ad-brand congruity in comparative advertising. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 27(3), 253-276. [CrossRef]

- Navrátilová, L., & Milichovský, F. (2015). Ways of using guerrilla marketing in SMEs. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 175, 268-274. [CrossRef]

- Niazi, M. A. K., Ghani, U., & Aziz, S. (2012). The emotionally charged advertisement and their influence on consumers’attitudes. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(1).

- Noorlitaria, G., Pangestu, F. R., Fitriansyah, U. S., & Mahsyar, S. (2020). How does brand awareness affect purchase intention in mediation by perceived quality and brand loyalty? Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(2), 103-109.

- Nufer, G. (2016). Ambush marketing in sports: an attack on sponsorship or innovative marketing? Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal.

- Nufer, G. (2013). Guerrilla marketing—Innovative or parasitic marketing. Modern Economy, 4(9), 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Nunthiphatprueksa, A. (2017). Is guerilla marketing worth investing? The impacts of guerilla marketing on purchase intention. The determinants of career growth: The case study of spa businesses, 39.

- Ozer, S., Oyman, M., & Ugurhan, Y. Z. C. (2020). The surprise effect of ambient ad on the path leading to purchase: Testing the role of attitude toward the brand. Journal of Marketing Communications, 26(6), 615-635. [CrossRef]

- Parida, P. (2011). Understanding Word-of-Mouth in Online Communities a Tool for Brand Building through Social Marketing. Kushagra International Management Review, 1(1), 37.

- Patalas, T. (2006). Guerilla-Marketing-Ideen schlagen Budget: Auf vertrautem Terrain Wettbewerbsvorteile sichern. Cornelsen.

- Patriotta, G. (2020). Writing impactful review articles. Journal of Management Studies, available online ahead of print: Doi: 10.1111/joms.12608. [CrossRef]

- Paul, J., & Rialp-Criado, A. (2020). The Art of Writing Literature review: What do we know and What do we need to know? International Business Review, available online ahead of print: Doi: 10.1016/j.ibusrev.2020.101717. [CrossRef]

- Payne, M. (1998). Ambush marketing: The undeserved advantage. Psychology & Marketing, 15(4), 323-331. [CrossRef]

- Petahiang, I. L. (2015). The Influence of Brand Awareness and Perceived Risk Toward Consumer Purchase Intention On Online Store (Case Study Of The Customer At Feb Unsrat Manado). Jurnal Berkala Ilmiah Efisiensi, 15(4).

- Pieters, R., Warlop, L., & Wedel, M. (2002). Breaking through the clutter: Benefits of advertisement originality and familiarity for brand attention and memory. Management science, 48(6), 765-781. [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P., Mackenzie, S., Bachrach, D., & Podsakoff, N. (2005). The influence of management journals in the 1980s and 1990s. Strategic Management Journal, 26(5), 473–488. [CrossRef]

- Powrani, K., & Kennedy, F. B. (2018). The effects of Guerrilla marketing on generation y consumer’s purchase intention. Asian Journal of Economics, Business and Accounting, 1-12.

- Prendergast, G., Ko, D., & Siu Yin, V. Y. (2010). Online word of mouth and consumer purchase intentions. International journal of advertising, 29(5), 687-708. [CrossRef]

- Prévot, A. (2009). Effects of Guerrilla Marketing on brand equity. Available at SSRN 1989990. [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, J. A., Qureshi, M. S., & Qureshi, M. A. (2018). Mitigating risk of failure by expanding family entrepreneurship and learning from international franchising experiences of Johnny Rockets: a case study in Pakistan. International Journal of Experiential Learning & Case Studies, 3(1), 110-127. [CrossRef]

- Rauwers, F., & van Noort, G. (2016). The underlying processes of creative media advertising. In Advances in Advertising Research (Vol. VI) (pp. 309-323). Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden.

- Rayport, J. (1996). The virus of marketing. Fast Company, 31.

- Ries, A., & Trout, J. (1986). Marketing warfare. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 3(4), 77-82. [CrossRef]

- Rossiter, J.R., and Percy, L. (1987). Advertising and Promotion Management. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Rotfeld, H. J. (2008). The stealth influence of covert marketing and much ado about what may be nothing. Journal of public policy & marketing, 27(1), 63-68. [CrossRef]

- Roozy, E., Arastoo, M. A., & Vazifehdust, H. (2014). Effect of brand equity on consumer purchase intention. Indian J. Sci. Res, 6(1), 212-217.

- Roux, T., van der Waldt, D. L. R., & Ehlers, L. (2013). A classification framework for out-of-home advertising media in South Africa. Communicatio, 39(3), 383-401. [CrossRef]

- Roy, A., & Chattopadhyay, S. P. (2010). Stealth marketing as a strategy. Business Horizons, 53(1), 69-79. [CrossRef]

- Roux, T., & Saucet, M. (2020). From dancing on the street to dating online: Evaluating the effects and outcomes of guerrilla street marketing. Available at SSRN 3592374. [CrossRef]

- Rushkoff, D. (1996). Media virus! Hidden agendas in popular culture. Random House Digital, Inc.

- Sandler, D. M., & Shani, D. (1993). Sponsorship and the Olympic Games: The consumer perspective. Sport marketing quarterly, 2(3), 38-43.

- Sandler, D.M. and Shani. D. (1989) ‘Olympic sponsorship vs ambush marketing: who gets the gold?’ Journal of Advertising Research, August/September, pp.9–14.

- Sass, E. (2013). Social media affects purchase decisions, ARF finds. http://www.mediapost.com/publications/article/191791/social-media-affects-purchase-decisions-arf-finds.html#axzz2JmP0ED3r.

- Saucet, M., & Cova, B. (2015). The secret lives of unconventional campaigns: Street marketing on the fringe. Journal of Marketing Communications, 21(1), 65-77. [CrossRef]

- Séguin, B., Lyberger, M., O’Reilly, N., & McCarthy, L. (2005). Internationalizing ambush marketing: The Olympic brand and country of origin. International Journal of Sport Marketing and Sponsorship, 6(4), 216-230.

- Séguin, B., & O’Reilly, N. J. (2008). The Olympic brand, ambush marketing and clutter. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, 4(1), 62-84. [CrossRef]

- Sajoy, P. B. (2013). Guerrilla marketing: A theoretical review. Indian Journal of Marketing, 43(4), 42-47.

- Selan, C. V., Lapian, S. L. J., & Gunawan, E. M. (2021). The effects of guerilla marketing on consumer purchase intention with brand awareness as a mediating variable in pt. solusi transportasi Indonesia (GRAB). Jurnal EMBA: Jurnal Riset Ekonomi, Manajemen, Bisnis dan Akuntansi, 9(4), 385-396.

- Shah, S. S. H., Aziz, J., Jaffari, A. R., Waris, S., Ejaz, W., Fatima, M., & Sherazi, S. K. (2012). The impact of brands on consumer purchase intentions. Asian Journal of Business Management, 4(2), 105-110.

- Shang, R. A., Chen, Y. C., & Liao, H. J. (2006). The value of participation in virtual consumer communities on brand loyalty. Internet research. [CrossRef]

- Shani, D., & Sandler, D. M. (1998). Ambush marketing: is confusion to blame for the flickering of the flame? Psychology & Marketing, 15(4), 367-383. [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A., & Horton, B. (1999). Ambient media: advertising’s new media opportunity? International Journal of Advertising, 18(3), 305-321. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R., & Sharma, S. K. (2015). Influence of guerrilla marketing on cell phone buying decisions in urban market of Chhattisgarh-A study. International Journal in Management & Social Science, 3(11), 417-427.

- Shenk, D. (1998). Data smog: Surviving the information glut: Harper San Francisco.

- Shu, W. (2014). Continual use of microblogs. Behaviour & Information Technology, 33(7), 666-677. [CrossRef]

- Skiba, J., Petty, R. D., & Carlson, L. (2019). Beyond deception: Potential unfair consumer injury from various types of covert marketing. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 53(4), 1573-1601. [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. E., MacKenzie, S. B., Yang, X., Buchholz, L. M., & Darley, W. K. (2007). Modeling the determinants and effects of creativity in advertising. Marketing science, 26(6), 819-833. [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. L., Spence, R., & Rashid, A. T. (2011). Mobile phones and expanding human capabilities. Information Technologies & International Development, 7(3), pp-77.

- Soomro, Y. A., Baeshen, Y., Alfarshouty, F., Kaimkhani, S. A., & Bhutto, M. Y. (2021). The Impact of Guerrilla Marketing on Brand Image: Evidence from Millennial Consumers in Pakistan. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 8(4), 917-928.

- Sørensen, J. (2008). Measuring emotions in a consumer decision-making context approaching or avoiding. Aalborg University, Denmark.

- Sussman, S. W., & Siegal, W. S. (2003). Informational influence in organizations: An integrated approach to knowledge adoption. Information systems research, 14(1), 47-65. [CrossRef]

- Sternthal, B. and Craig, C.S. (1973), Humour in advertising. Journal of Marketing, Vol. 37 No. 4, pp. 12-18. [CrossRef]

- Stoltman, J.J. (1991), Advertising effectiveness: the role of advertising schemas. In Childers, T.L. et al. (Eds), Marketing Theory and Applications, 2, 317-318. American Marketing Association, Chicago, IL.

- Spahic, D., & Parilti, N. The impact of guerilla marketing practices on consumer attitudes and comparison with traditional marketing communication: a practice. Journal of Banking and Financial Research, 6(1), 1-24.

- Swanepoel, C., Lye, A., & Rugimbana, R. (2009). Virally inspired: A review of the theory of viral stealth marketing. Australasian Marketing Journal, 17(1), 9-15. [CrossRef]

- Tam, D. D., & Khuong, M. N. (2015). The Effects of Guerilla Marketing on Gen Y’s Purchase Intention--A Study in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. International Journal of Trade, Economics and Finance, 6(4), 191. [CrossRef]

- Tam, D. D & Khuong, M.N. (2016), ―Guerrilla marketing’s effects on Gen Y’s word-of-mouth intention – a mediation of credibility, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 28 (1), 4-22.

- Taylor, C. R., Franke, G. R., & Bang, H. K. (2006). Use and effectiveness of billboards: Perspectives from selective-perception theory and retail-gravity models. Journal of advertising, 35(4), 21-34. [CrossRef]

- Thomas Jr, G. M. (2004). Building the buzz in the hive mind. Journal of Consumer Behaviour: An International Research Review, 4(1), 64-72. [CrossRef]

- Till, B. D., & Baack, D. W. (2005). Recall and persuasion: does creative advertising matter? Journal of advertising, 34(3), 47-57. [CrossRef]

- Tompson, S. (2003). Guerrilla marketing: Agile advertising of information services. Information outlook, 7(2).

- Torlak, O., Ozkara, B. Y., Tiltay, M. A., Cengiz, H., & Dulger, M. F. (2014). The effect of electronic word of mouth on brand image and purchase intention: An application concerning cell phone brands for youth consumers in Turkey. Journal of Marketing Development and Competitiveness, 8(2), 61.

- Trusov, M., Bucklin, R. E., & Pauwels, K. (2009). Effects of word-of-mouth versus traditional marketing: findings from an internet social networking site. Journal of marketing, 73(5), 90-102. [CrossRef]

- Tsang, M. M., Ho, S. C., & Liang, T. P. (2004). Consumer attitudes toward mobile advertising: An empirical study. International journal of electronic commerce, 8(3), 65-78. [CrossRef]

- Ujwala, B. (2012). Insights of guerrilla marketing in business scenario. International Journal of Marketing, Financial Services & Management Research, 1(10), 120-128.

- Veloutsou, C., & O’Donnell, C. (2005). Exploring the effectiveness of taxis as an advertising medium. International Journal of Advertising, 24(2), 217-239. [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, J., Yoo, S. & Hanssens, D.M. (2008). The impact of marketing induced vs word-of-mouth customer acquisition on customer equity, Journal of Marketing Science, 45 (1), 48-59.

- Vlačić, B., Corbo, L., e Silva, S. C., & Dabić, M. (2021). The evolving role of artificial intelligence in marketing: A review and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 128, 187-203. [CrossRef]

- Walia, P., & Singla, L. (2017). An analytical study on impact of guerrilla marketing among middle aged smart-phone users. International Journal of Advanced Scientific Research and Management, 2(4).

- Waltman, L., & Van Eck, N. J. (2012). A new methodology for constructing a publication-level classification system of science. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63(12), 2378-2392. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., & Yang, Z. (2010). The effect of brand credibility on consumers’ brand purchase intention in emerging economies: The moderating role of brand awareness and brand image. Journal of global marketing, 23(3), 177-188. [CrossRef]

- Wanner, M. (2011). More than the consumer eye can see: Guerrilla advertising from an agency standpoint. The Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications, 2(1), 103-109.

- Wathen, C. N., & Burkell, J. (2002). Believe it or not: Factors influencing credibility on the Web. Journal of the American society for information science and technology, 53(2), 134-144. [CrossRef]

- Wernick, A., & Akınhay, O. (1996). Promosyon kültürü: reklam, ideoloji ve sembolik anlatım. Bilim ve Sanat.

- West, D. C., Kover, A. J., & Caruana, A. (2008). Practitioner and customer views of advertising creativity: same concept, different meaning? Journal of Advertising, 37(4), 35-46. [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, J. (1989). Creativity and conformity in science: Titles, keywords and co-word analysis. Social Studies of Science, 19(3), 473-496. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R. T., & Till, B. D. (2011). Effects of outdoor advertising: Does location matter? Psychology & Marketing, 28(9), 909-933. [CrossRef]

- Wiryawan, G. N. D., & Wardana, I. M. (2020). The Influence of Guerrilla Marketing on Word of Mouth Activities Mediated By Adverstising Credibility–Study on Generation Z in Denpasar. American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research, 4(11), 49-60.

- Yaseen, N.; Tahira, M.; Gulzar, A. and Anwar, A. (2011), “Impact of Brand Awareness, Perceived Quality and Customer Loyalty on Brand Profitability and Purchase Intention: A Resellers’ View”, Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, 3(8), 833-839.

- Yildiz, S. (2017). Effects of guerrilla marketing on brand awareness and consumers’purchase intention. Global Journal of Economics and Business Studies, 6(12), 177-185.

- Yüksel, A. (2010) Dystopia Created by Guerrilla Art and Guerrilla Advertising as a Utopia, Master thesis, Institute of Fine Arts, Marmara University, Istanbul.

- Zerr K (2003) Guerilla-Marketing in der Kommunikation – Kennzeichen, Mechanismen und Gefahren. In: Kamenz U (Hrsg) Applied Marketing. Springer, Berlin, S 583-590.

- Zhang, H., Zhou, S., & Shen, B. (2014). Public trust: A comprehensive investigation on perceived media credibility in China. Asian Journal of Communication, 24(2), 158-172. [CrossRef]

| Variables of Marketing Guerilla | Authors/Articles | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Surprise Effect | Itti and Baldi (2008); Ay et al. (2010); Dinh and Mai (2015); Katke (2016); Yildiz (2017); Spahic and Parilti (2019); Nagar, (2015); Nunthiphatprueksa, (2017); Nufer (2013); Druing and Fahrenholz, (2008); Halkias and Kokkinaki (2014). | 10 |

| Emotional Arousal | Isen and Shalker, (1982); Muehling and Laczniak (1988); Niazi et al. (2012); Tam and Khuong (2015); Dinh and Mai (2015); Heath, (2007); Sorensen, (2008). | 7 |

| Humor | West et al. (2008); Chan (2011); Eisend (2011); Eisend et al. (2014); Dinh and Mai (2015); Nunthiphatprueksa (2017); Pieters et al. (2002). | 7 |

| Information’s Content/ Clarity | Hafer et al. (1996); Dinh and Mai (2015); Dinh et al. (2015); Nunthiphatprueksa, (2017); Wiryawan and Wardana (2020); Tam and Khuong (2015); Tam and Khuong (2016). | 7 |

| Guerrilla Mobile | Ujwala (2012); Katke (2016); Spahic and Parilti (2019); Smith et al. (2011); Grewal et al. (2016) | 3 |

| Brand Awareness | Rossister and Percy (1987); Chen and Chang (2008); Chi et al. (2009), Prevot (2009); Wang and Yang (2010); Ling et al. (2010); Jalilvand et al. (2011); Mokhtari (2011); Shah et al. (2012); Malik et al. (2013); Navrátilová and Milichovský (2015); Kotler and Keller (2016); Ahmed et al. (2017); Yildiz (2017); Fattal (2018); Ahmed et al. (2020); Noorlitaria et al. (2020). | 17 |

| Creativity/ Credibility | Jackson and Messick (1967); MacKenzie and Lutz (1989); Wathen and Burkell (2002): Tsang et al. (2004); McKnight and Kacmar (2006); Smith et al. (2007); Dahlén et al. (2008); Mercanti-Guerin (2008); Prendergast et al. (2010); Zhang et al. (2014); Tam and Khuong (2015); Dinh and Mai (2015); Kim et al. (2016); Ma and Atkin (2017); Gökerik (2018). | 15 |

| WOM | Herr et al. (1991); Helm (2000); Gruber (2004); Ahuja et al. (2007); Villanueva et al. (2008); Baltes and Leibing (2008); Cheema and Kaikati (2010); Kamau and Bwisa (2013); Dinh and Mai (2015); Helm (2000); Ferguson (2008); Trusov et al. (2009); Gruber, (2004); Aprilia and Kusumawati, (2021); Al Mana and Mirza (2013); Torlak et al. (2014); Chung and Tsai (2009); Walia and Singla (2017). | 18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).