1. Introduction

Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) is known as a crucial part of embryogenesis for nearly half a century, but its critical role in cancer metastasis was revealed only recently in the early 2000’s [

1,

2]. Since then, a continuous increase in the interest on understanding the role of EMT in cancer metastasis has been reflected in about 6000 publications in 2019 [

3]. While it is controversially discussed how to understand EMT and its relevance during and for metastasis [

4], three key features are commonly attributed to EMT or EMT-like changes.

First, the loss of proteins characterizing an epithelial phenotype and the acquisition of mesenchymal proteins is considered the basis of EMT (EMT-hallmarks) [

5]. Driven by signals received from the tumor microenvironment (TME) [

6], EMT-relevant transcription factors (e.g. SNAIL, SLUG, TWIST) downregulate epithelial and/or upregulate mesenchymal genes that cause the re-organization of the cell cytoskeleton [

1]. The resultant phenotype is giving up its cobblestone-like epithelial morphology as the cell-cell junctions are abrogated and cells adopt a more spindle-like, elongated shape with a front-back polarity (Morphology). Third, as a consequence of epithelial depletions and mesenchymal fortifications, cellular motility is highly increased (Motility). An additional feature is the enhanced secretion of extracellular matrix (ECM)-degrading enzymes, promoting motility and helping cells to better cope with migration and invasion that accompanies metastasis [

7].

Importantly, EMT has to be understood as a concept of cellular plasticity (Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Plasticity (EMP)) and adaptability. It is a reversible and non-binary transition that is not necessarily completed but rather partially fulfilled (partial EMT) [

3,

8]. Intermediate hybrid states (E/M-states) possess both, epithelial and mesenchymal features and the degree of transition is governed by the contextuality of signaling within the tumor microenvironment, the developmental lineage of the distinct cancer types and (epi-) genetic alterations and regulations [

3,

9,

10,

11]. This trans-differentiation between epithelial and mesenchymal phenotypes has been described for all kinds of carcinoma [

12]. Aside from lung cancer, colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma and prostate cancer it is breast cancer that has been tremendously studied and proven clinically relevant in the context of EMT [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Based on gene expression profiling and clinical outcome, breast cancer can be classified into four intrinsic subtypes with specific molecular marker expression and increasing malignancies [

17]. Luminal A and Luminal B subtypes express the estrogen receptor (ER) and the progesterone receptor (PR) (Luminal A > Luminal B) and both subtypes are fairly sensitive to endocrine therapies. HER2 subtype lacks the latter sensitivity (as being ER/PR negative) but displays an overexpression of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) [

18,

19]. Absence of ER and HER2 is descriptive for the basal-like subtype, which is considered a phenotype with high mutation load and poor prognosis [

20,

21]. Triple negative breast cancer (TNBC), a subgroup, representing 70 - 80% of basal-like breast cancers, is characterized negative for ER, PR and HER2 [

19,

22]. It is the most aggressive form of breast cancer due to a synergism of poor treatment options and a high metastatic potential, which presumably relies on EMT-like changes enabling DCIS-to-IBC progression [

23,

24,

25].

The transmembrane protein E-cadherin can be considered as “the guardian” of an epithelial phenotype. The extracellular domains of E-cadherin of each cell entangle with the extracellular domains on neighboring cells, leading to the establishment of adherens junctions [

26]. Once downregulated, it is not only the physical/mechanical rupture that dissolves the epithelial phenotype. Intracellularly bound β-catenin (within the cytoplasmic cell adhesion complex) can translocate into the nucleus once E-cadherin is internalized, and act as a transcription factor towards EMT [

27,

28].

It is well accepted, that a switch in cellular intermediate filament (IF) usage from cytokeratin to vimentin occurs during EMT [

3,

29]. Vimentin is a network-forming type III intermediate filament and may be considered as the counterpart to E-cadherin, also because its expression is mainly restricted to mesenchymal cells [

30,

31]. By maintaining cytoskeletal integrity and mechanical strength, vimentin cushions traction stress during single-cell migration [

32]. Apart from this load-bearing function, vimentin promotes microtubule polarity which is a prerequisite for directed cell migration [

30,

33]. Vimentin IF (VIF) maturation depends on microtubular transport. Whilst providing the infrastructure for VIF network assembly, a long-lasting template of microtubule’s architecture is simultaneously formed. Considering the fast turnover of microtubules (10 times faster than VIF), it appears, that vimentin’s “memory” function eventually guides and enables persistent microtubules-mediated cell polarization and consequently directional migration [

34].

The EMT machinery can be induced by extracellular stimuli in multiple ways, mainly by soluble factors like TGF-β, EGF or HGF [

5,

35]. However, it was shown that solid components of the ECM trigger EMT in lung cancer. Cells, cultured on a type I collagen gel activated autocrine TGF-β3 signaling, that in turn induced EMT, which is based on collagen I fiber recognition via integrins [

35]. Likewise, Shawn P. Carey

et al. created a 3-D collagen I matrix with defined mechanical properties, mimicking the stroma of the mammary gland. Incorporation of non-malignant breast epithelial cells into this scaffold upregulated mesenchymal genes, which was attributed to both, biochemical and mechanical stimuli of the matrix. Interestingly, insertion of the same cell line into a basement membrane - mimicking Matrigel (containing mainly collagen IV and laminin) could not provoke EMT-like changes. The authors concluded, that the distinct ECM composition of epithelial (Matrigel) and stromal tissue (collagen I) differentiated between EMT or not [

36]. Furthermore, using a xenograft breast cancer mouse model, M. Vidal

et al. reported that only cancer cells at the interface of the tumor and its stroma, i.e. cells that are directly exposed to the ECM of the stromal compartment express vimentin whereas cells in the core region of the tumor maintain cytokeratin expression [

37]. Taken together, it appears that signals cancer cells receive from the distinct ECM comprised within the epithelial (DCIS) and stromal (IBC) compartment ultimately dictate the present phenotype and phenotypic changes. It remains elusive to what extent the combinatorial action of solid and soluble factors in each compartment participate during initial as well as sustained EMT induction.

In this study, we used two common collagen coatings (Globular type IV collagen and fibrillar type I collagen) as provisional matrices to depict the two opposing ECM components in the mammary gland (

Figure 1). Globular type IV collagen is used as a part of the basement membrane (BM), the physiological substrate of the (myo-) epithelial layer. As described above, type I collagen is the main extracellular compound within the stromal fraction. In a healthy tissue, it is well-separated from the epithelium via the BM (

Figure 1), but leakage during tumor progression causes cell exposure to it.

To stress and assess the concept of “contextuality of signaling” within the TME and its importance for EMT [

4,

10], breast cancer cells of distinct intrinsic subtypes were subjected to a combinatorial treatment with the different collagens and the prominent EMT-inducers, TGF-β1 or EGF. Single treatment with either soluble or solid ECM components served as reference. Initially, we defined the EMT-status of the four breast cancer cell lines based on morphological aspects, EMT-marker (

E-cadherin, CDH1 and Vimentin, VIM) expression and migratory behavior. MCF7 (Luminal A) and HCC1954 (HER2) cells were found to hold strong epithelial characteristics, whereas the MDA-MB-231 cell line (TNBC) was clearly attributed a mesenchymal phenotype. The second TNBC cell line MDA-MB-468 featured both, epithelial and mesenchymal characteristics (epithelial > mesenchymal), and therefore was considered an E/M-hybrid. We then monitored the three mentioned EMT features under exposure to a simplified model, taking MDA-MB-231 attributes as a positive control/reference. Cellular shape factor image analysis served as a powerful tool to predict EMT-like changes. Together with the input from protein and migration analysis, we were able to build up a computational EMT-model that hopefully helps to further understand the complexity of EMT. Besides using the model to predict EMT-phenotype and phenotypic changes that arise during cellular stimulations we exemplified its possible relevance in a miR200c inducible cell line for the facile evaluation of therapeutic efficacy of new drug candidates targeting EMT. Furthermore, our findings highlight that cellular responses are affected by combinatorial action of growth factors and ECM components requiring future 2D EMT-research to consider this context-dependency by applying similar experimental set-ups.

3. Discussion

Here, we established a simplified, EMT-relevant breast cancer model comprising 4 breast cancer cell lines. The triad of EMT-marker expression, morphology and migration was found to allow for a reasonable approximation of the present cellular EMT-status merging their input into a computational model phenotyping EMT in breast cancer, which we believe can serve as new platform to support EMT-related research. Moreover, biomimetic collagen coatings were shown to partially (cell line dependent) but not necessarily influence cellular EMT-phenotype upon growth factor stimulation. Surprisingly, other than reported elsewhere [

36], the distinct collagen types chosen to represent the compartmentalization of the mammary gland (DCIS vs. IBC) did not differentially affect the phenotype and phenotypic transitions. Presumably, including

in vivo-like cues such as 3-dimensionality and stiffness of the ECM would help to draw a final conclusion.

Underlining the current understanding of EMT in cancer research [

4,

5,

7,

8,

14,

27,

62,

63], (high) vimentin expression and absence of E-cadherin determined a fairly migratory phenotype with an elongated shape as was shown for the MDA-MB-231 cell line. Expression of the epithelial protein marker E-cadherin appeared to have a strong impact on morphological features as the three E-cadherin

+ cell lines studied here exhibited rounded shapes with A

R and C

N values close to a value of 1. Further, its expression was correlating with an immotile phenotype as long as vimentin was not co-expressed. Indeed, even low levels of vimentin protein could be correlated with increased cellular motility over vimentin

- cells as was demonstrated for MDA-MB-468 cell line. In parallel to the classification of the intrinsic subtype nomenclature, epithelial characteristics vanished towards more malignant phenotypes whereas mesenchymal features concentrated in both TNBC cell lines (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

In a recent study it was reported that Slug-mediated downregulation of E-cadherin, together with upregulation of vimentin impaired cellular morphology and increased cellular motility of the non-malignant breast epithelial cell line MCF10A [

64]. Cellular circularity, which is interchangeable with the aspect ratio, was strongly decreased. Subsequent RNA interference with vimentin-targeting siRNA not only restored the circular cellular shape but also decelerated cellular motility. The authors attributed vimentin a crucial role in influencing cellular morphology and motility, also because it may directly inhibit E-cadherin expression. In another study on breast cancer E-cadherin expression was proposed to be obligatory for a round polygon shape [

38]. However, the findings of our EMT induction study suggest that an upregulation of vimentin and a concomitant downregulation of E-cadherin protein levels drive important morphological changes and strengthen migratory behavior, whereas merely downregulation of E-cadherin, concluded from the MCF7 cell line, was insufficient to significantly alter either of the latter two. As seen for MDA-MB-468, EGF stimulation significantly elongated cellular and nuclear morphology as part of a pronounced EMT-induction (↓ E-cadherin, ↑↑ vimentin). The

AR and

CN values of MDA-MB-231

blank (

AR = 0.240 ± 0.157;

CN = 0.735 ± 0.101) and MDA-MB-468

+EGF (

AR = 0.358 ± 0.129;

CN = 0.825 ± 0.102) essentially converged in a concentration-dependent manner (

Figure S2) implying a shift from an E/M-hybrid with mostly epithelial characteristics towards a phenotype endowed with dominant mesenchymal functionalities (

Figure 5c and

Figure 7a). Interestingly, upon EGF stimulation in MDA-MB-468, cellular migration was superior or at least the same to what has been observed for untreated MDA-MB-231. It took 24-28 h to close the gap in comparison to 30-35h for the already mesenchymal cell line. Moreover, we successfully transformed HCC1954 cells into a hybrid E/M phenotype entailing alterations of both shape factors and an acceleration of cellular motility. The wound healing migration assay revealed similar migratory properties under combinatorial treatment of TGF-β1 with collagen I, as was detected for MDA-MB-468

blank cells (56h vs. 50h). It appears that the strongly elevated vimentin protein level is the main driver for increased cellular motility, as E-cadherin level remained unaffected. Contradictory to these findings, combinatorial treatment of TGF-β1 with type IV collagen also shown to upregulate vimentin expression did not result in increased motility.

We can only speculate about the mechanistic causality explaining how a combinatorial treatment can provoke EMT-like changes while the single components fail to do so. In accordance to our data, Stephen T. Buckley

et al. examined TGF-β1-induced EMT in human alveolar epithelial cells (AEC) and found that following TGF-β1 stimulation EMT induction was enhanced when cells were grown on a collagen I matrix as compared to growth on a glass surface [

43]. They based their findings on changes in cellular shape factor and cellular stiffness to be superior to the simple growth factor treatment and emphasized the role of integrins (“ECM-receptors”) for EMT induction as was reported elsewhere [

65]. In this work on EMT in fibrosis, the authors elegantly ruled out the possibility that growth of AECs on the ECM would lead to increased secretion of TGF-β1 which in turn drives EMT. Instead, they provided strong evidence that the αvβ6 integrin, a receptor that binds fibronectin, activates latent TGF-β1 signaling that causes cells to undergo EMT. Still, this cannot be the explanation in our case. Firstly, αvβ6 integrin is not known for binding any collagen type and secondly, their observation was independent of TGF-β1 supply. Nevertheless, literature offers two other explanations for how integrin-growth factor receptor (GFR) interplay may modulate cellular phenotypes [

66]. GFR-ligand interactions can lead to cytosolic inside-out integrin receptor activation or changes in expression pattern of integrin subunits [

67]. Referring to our data, TGF-β1 signaling may have caused enhanced integrin activation/expression that would have resulted in intensified integrin signaling (through collagen-integrin interaction), finally leading to EMT-like changes. On the other hand, integrins may co-opt in GFR signaling cascades. Signals emitting from integrin activation participate in downstream processes of GFR stimulation. Consequently, those kinds of interactions may not be the driving force for EMT, but rather scale up its dimension. Hence, we have to consider, that the 48 h to 72 h time scope of our EMT induction study was insufficiently long to detect TGF-β1-mediated EMT in HCC1954. However, our findings, together with the cited literature highlight the evident role of both contextuality of signaling and the tumor microenvironment for EMT induction

in vitro. Such combinatorial actions might induce EMT in DCISs helping to overcome the physiological barrier,

i.e. the basement membrane, whilst sustaining a (more) mesenchymal phenotype during stromal invasion.

Confocal imaging combined with image data analysis has been proven to be a powerful tool for addressing many kinds of biological questions. In the recent years, imaging has become increasingly relevant for studies on “phenomics”, the quantification of the plurality of phenotypes that fully characterizes an organism [

68]. Collective cellular properties such as cellular and subcellular morphologies are the result of genotypic expression pattern, whose quantification is readily susceptible via image data analysis [

69]. In the context of EMT, a thoroughly planed study by Weikang Wang

et al. stunningly demonstrated how live-cell imaging with subsequent deep image analysis disclosed heterogeneous transition dynamics upon TGF-β stimulation within one cell line [

70]. They described a cell state in a 309-dimensional composite feature space of cell morphology and vimentin texture features and further revealed that spatiotemporal vimentin distribution allows for recording phenotypic alteration. The EMT-phenotyping model presented in our work is rather a snapshot approach as comparison of shape factors (

CN,

AR) was conducted at a specific time-point. As indicated in Figure 9

, the morphological features coincided with EMT-marker expression and cellular motility. It is noteworthy that this computational model not only ranges EMT-phenotype and phenotypic changes, but presumably permits to differentiate between cell line specific transition-dynamics as indicated by the elliptic, colored areas in

Figure 7a. To exemplify how this model can be used, we applied it to a miR200c inducible MDA-MB-231 cell line (

Figure 7c,

Figure S4). miR200c expression, which is absent in untreated MDA-MB-231 cells, correlated with an epithelial phenotype (

Figure 7b). The height of miR200c expression levels further discriminated between fully epithelial and partial epithelial characteristics. Induction of miR200c in the MDA-MB-231 cell line resulted in MET, resembling a potential therapeutic intervention targeting EMT. The success of miRNA induction after 48 h and 72 h resulting in increased nuclear circularity, and cellular aspect ratios closer to 1.0 can be appreciated as the shift from the left to the right alongside the regression diagonal. Simultaneously, the increasing E/M-ratio (= reciprocal M/E-ratio) and the decrease in

νa are testifying to MET. Therefore, it may be sufficient to analyze one of the aforementioned shape factors in order to predict the cellular E/M character as well as cellular motility. Thus, our model can estimate the impact of therapeutic approaches that target EMT-relevant factors on the EMT phenotype and may serve as an indicator to decide over new drug candidates during screening processes.

4. Materials and Methods

Materials and cell culture: Formaldehyde solution (≥ 36%), 4′,6–diamidino–2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI), FluorSave reagent, DNase I (recombinant, RNase-free), cOmplete™, EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail, Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail 2, RIPA buffer, Tris buffered saline powder, Ponceau S Stain, Tween 20, Amersham™ Protran® Western-Blotting-Membrane (nitrocellulose) and for cell culture Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM), RPMI-1640 Medium, Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), Penicillin-Streptomycin (Pen/Strep) solution, Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), trypsin-EDTA solution 0.05 and 0.25%, 200 mM of L-glutamine solution and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Taufkirchen, Germany). GAPDH Monoclonal Antibody (ZG003), Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit, Novex™ 10% Tris-Glycine Mini Gels (WedgeWell™ format, 15-well), Novex™ Value™ 4-20% Tris-Glycine Mini Gels (1.0 mm, 10-well), Page Ruler™ Plus Prestained Protein Ladder 10 to 250 kDa, Tris Glycin transfer buffer, SuperSignal™ West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate, Rhodamine Phalloidin, High capacity cDNA synthesis kit, Power SYBR™ Green PCR Master Mix, PureLink™ RNA Mini Kit and for cell culture Leibovitz's L-15 Medium and MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids Solution (100X) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Hs_CDH1_Primer Assay (QT00080143), Hs_VIM_Primer Assay (QT00095795) and Hs_GAPDH_1_SG QuantiTect Primer Assay (QT00079247) were purchased from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany). Collagen I (sc-136154), Collagen IV (sc-29010), m-IgGκ BP-HRP (sc-516102), E-cadherin Antibody (G-10) and Vimentin Antibody (V9) were ordered from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, Texas, USA). Rotiphorese 10x SDS Page, Rotilabo®-Blotting Papers and Methanol (blotting grade) were purchased from Carl Roth (Karlsruhe, Germany). rh-TGF-β 1 (Transforming Growth Factor beta 1) and rh-EGF (Epidermal Growth Factor) were purchased from ImmunoTools (Friesoythe, Germany). HyClone trypan blue solution 0.4% in phosphate-buffered saline was obtained from FisherScientific (Hampton, NH, USA). Culture-Insert 2 Well in µ-Dish 35 mm was purchased from Ibidi (Gräfelfing, Germany). Laemmli loading buffer (4x) was purchased from VWR (Allison Park, PA, USA).

MCF7 (and MCF7 miR200c_KO) cells, a Luminal A breast cancer cell line, were cultured in EMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1x Pen/Strep, 1x MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids Solution and 2 mM glutamine. The HER2-positive breast cancer cell line HCC1954 was grown in RPMI-1640 Medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1x Pen/Strep. MDA-MB-231 (and MDA-MB-231 i-miR200c) cells, a triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) cell line, were cultured in high glucose (4500 mg/L) DMEM. 10% FBS, 1x Pen/Strep and 2 mM glutamine were added to the medium. For miRNA induction medium is equipped with 5 µg/ml doxycycline hydrochloride as was described elsewhere.[

38] The latter three cell lines were cultured in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO

2 at 37°C. The second TNBC cell line MDA-MB-468 was grown in L-15 Medium supplemented with 20% FBS and 1x Pen/Strep. Those cells were held in a humidified incubator with 0% CO

2 at 37°C.

EMT marker – gene expression analysis: To compare EMT-marker RNA expression among the four cell lines, RT-qPCR was performed. Of each cell line 200.000 cells were seeded in a 6-well plate and cultured for 24 h. After the incubation, cells were harvested, and total RNA was isolated using the PureLink RNA mini kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol with additional DNAse I digestion. Subsequently, 1000 ng of RNA was used to synthesize cDNA using the High capacity cDNA synthesis kit. In the following, E-cadherin- and vimentin-specific primers were used to amplify and quantify RNA using Power SYBR™ Green PCR Master Mix and the qTOWER real-time PCR thermal cycler (Analytik Jena, Jena, Germany). Ct values were normalized to GAPDH RNA expression ,and delta Ct values were calculated for the comparison.

In order to quantify the miR200c expression levels, RNA was isolated using the peqGOLD Micro RNA kit (Peqlab Biotechnology GmbH, Erlangen, Germany), according to the manufacturer protocol. cDNA was synthesized with the qScript microRNA cDNA synthesis kit (Quantabio, Beverly, MA, USA). Since microRNAs are not polyadenylated, the polyA tailing reaction was performed by mixing 1 µg of RNA, 2 µL of Poly(A) Tailing Buffer, 1 µL Poly(A) polymerase, nuclease-free water up to 10 µL and incubated 60 minutes at 37°C followed by 5 minutes at 70°C. Subsequently, 9 µL of microRNA cDNA reaction mix was mixed with 1 µL reverse transcriptase and incubated 20 minutes at 42°C, plus 5 minutes at 85°C. RT-qPCR was performed in triplicates. The microRNA-191 was used as a housekeeper and each sample was analyzed in triplicates.

EMT marker – protein level analysis: To define the EMT status, protein levels of CDH1 and VIM of the 4 cell lines were analyzed via Western blotting. Of each cell line 300.000 cells were seeded in a 6-well plate and cultured for 24h. Total protein extract was isolated after incubation. Briefly, cells were washed 3 times with PBS prior to cell lyses. To each well, 70 µl of proteinase- and phosphatase-inhibitor containing RIPA buffer was added, and cells were kept on ice for 30 minutes. Hereinafter, wells were thoroughly scraped, and the extracts were transferred into 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes. After a 10 min centrifugation step at 4°C, total protein concentration was assessed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit). Gels were loaded with 30 µg protein per sample and electrophoresis was run for 90 min at 120 mV. Subsequent to 1 h of protein transfer at 100 mV, blots were washed, blocked and incubated overnight using E-cadherin-, vimentin- and GAPDH-specific antibodies. HRP-bound secondary antibody was added for 1 h under exclusion of light before blots were developed.

As part of the EMT induction study, we first optimized the timepoints when to extract protein data. It should be noted that cell lines do not facultatively perform EMT and may exhibit different “transition dynamics” (fast vs. slow) upon GF treatment. Therefore we chose an optimized time point (72 h) and GF concentrations that allowed to detect EMT-like changes on the protein level in the cell lines used.

To do so, 300.000 cells were seeded to attach for 4 h. Samples included untreated cells, cells stimulated with growth factors and cells grown in collagen-coated wells (+/- growth factors). Afterwards control cells and cells growing only on collagen were washed with PBS, and pre-warmed medium was refilled. At this step, growth factors were included. Samples were either supplied with 10 ng/ml of TGF-β1 or 25 ng/ml EGF or both. Collagen I and IV coatings (2 µg collagen/cm2) of the respective wells were prepared following the manufacturer’s protocol in advance to the seeding. After 72 h incubation, samples were subjected to the aforementioned Western blotting protocol, and E-cadherin and vimentin protein levels were normalized to GAPDH-housekeeping protein level using the Image Lab™ software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

Confocal scanning microscopy – Morphological analysis: Confocal image analysis was used to assess and quantify morphological differences between cell lines and treatments. Experimental set-up was performed as described above. Briefly, sterile glass coverslips were distributed in a 24-well plate. Collagen coatings were conducted for the respective wells. Thereafter, 40.000 cells were seeded and attached for 4 h. After the growth factor treatment, cells were incubated for 72 h. Hereinafter, wells were washed 3 times with PBS before cells were fixed for 15 min with a 4% formaldehyde solution. To stain the actin cytoskeleton, cells were incubated with 8.25 µM rhodamine phalloidin solution for 40 min. Hereinafter, cells were washed another 3 times with PBS. Nuclei staining was achieved by 10 min incubation with a 0.5 µg/ml DAPI solution. Finally, after an additional washing step, samples were mounted on glass slides using FluorSave and stored at 4°C until the next day. Fluorescence images were acquired using a laser scanning microscope (Leica SP8 inverted, Software: LAS X, Leica microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a HC PL APO CS2 40x/1.30 and 63x/1.40 oil immersion objective. Diode lasers (405 nm) and a semiconductor laser OPSL (552 nm) were chosen for excitation, emission was detected in blue (PMT1: 410–520 nm) and yellow (PMT2: 560nm – 760nm), respectively. Images were further processed with Fiji image analysis software [

39]. Nuclear circularity was calculated as

, and the cellular aspect ratio as

. The axis (d

min and d

max) were drawn manually.

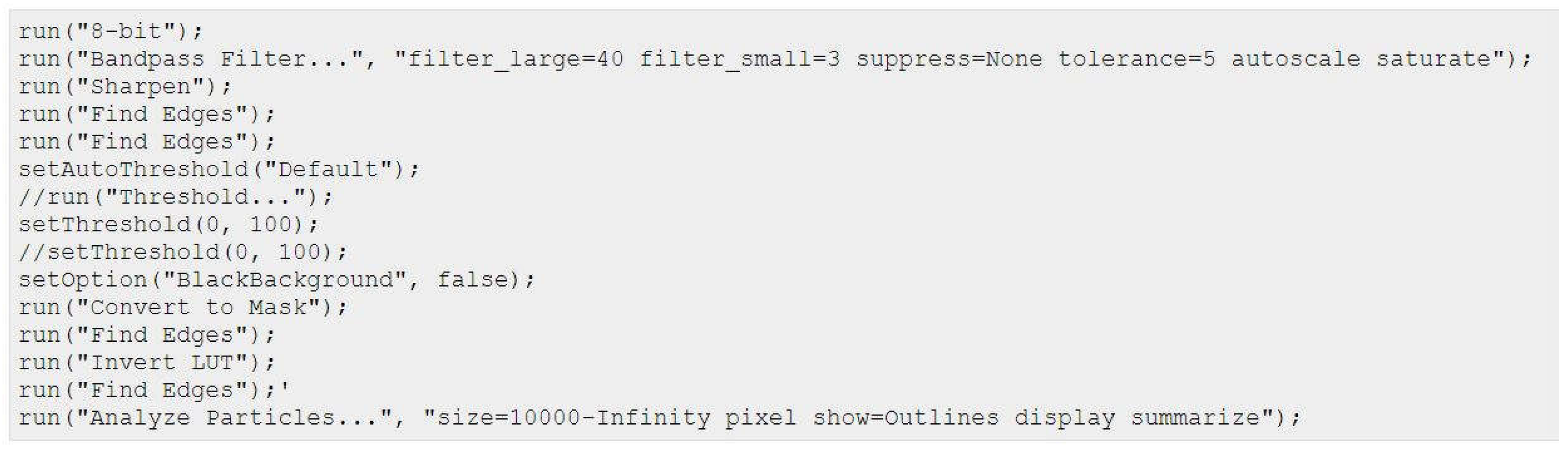

Ibidi® migration assay: Migratory properties were analyzed as follows: To define the cellular EMT-status, 25.000 cells of each cell line were seeded in both wells of the Ibidi culture-insert. After 24h the inserts were carefully removed and the time until gap closure in between the two wells was monitored for up to 120 h using the Keyence BZ81000 Fluorescence microscope (Keyence, Osaka, Japan). Three to four pictures of different parts of the gaps were taken for each time point. The cell free area was analyzed based on a custom-made macro within the Fiji imaging software:

Percentage gap closure was calculated according to the following equation:

As part of the EMT induction study, cells were seeded at a density of 15.000 cells per well. Collagen coatings were prepared in advance. Similar to what has been described for the protein analysis growth factors were supplemented after cell-attachment. Samples were incubated for 48 h before the culture-inserts were removed and migration was analyzed.