Submitted:

05 March 2023

Posted:

06 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Study Population

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.5. Sample Collection, Transport, Preparation & Storage

2.6. Serological Analysis

2.7. Data analysis

3. Results And discussion

3.1. Patients Characteristics

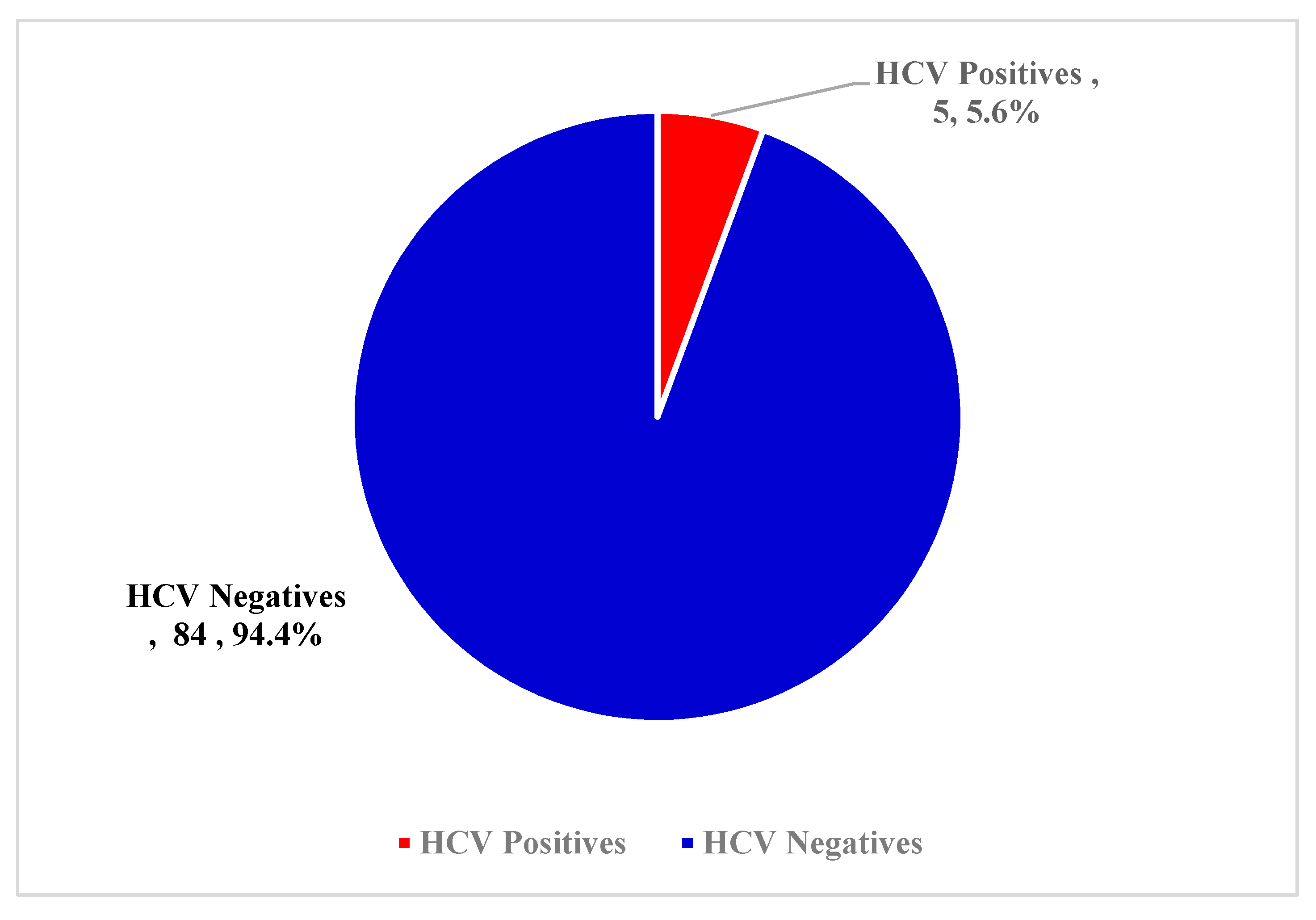

3.2. Overall Prevalence of HCV Antibody

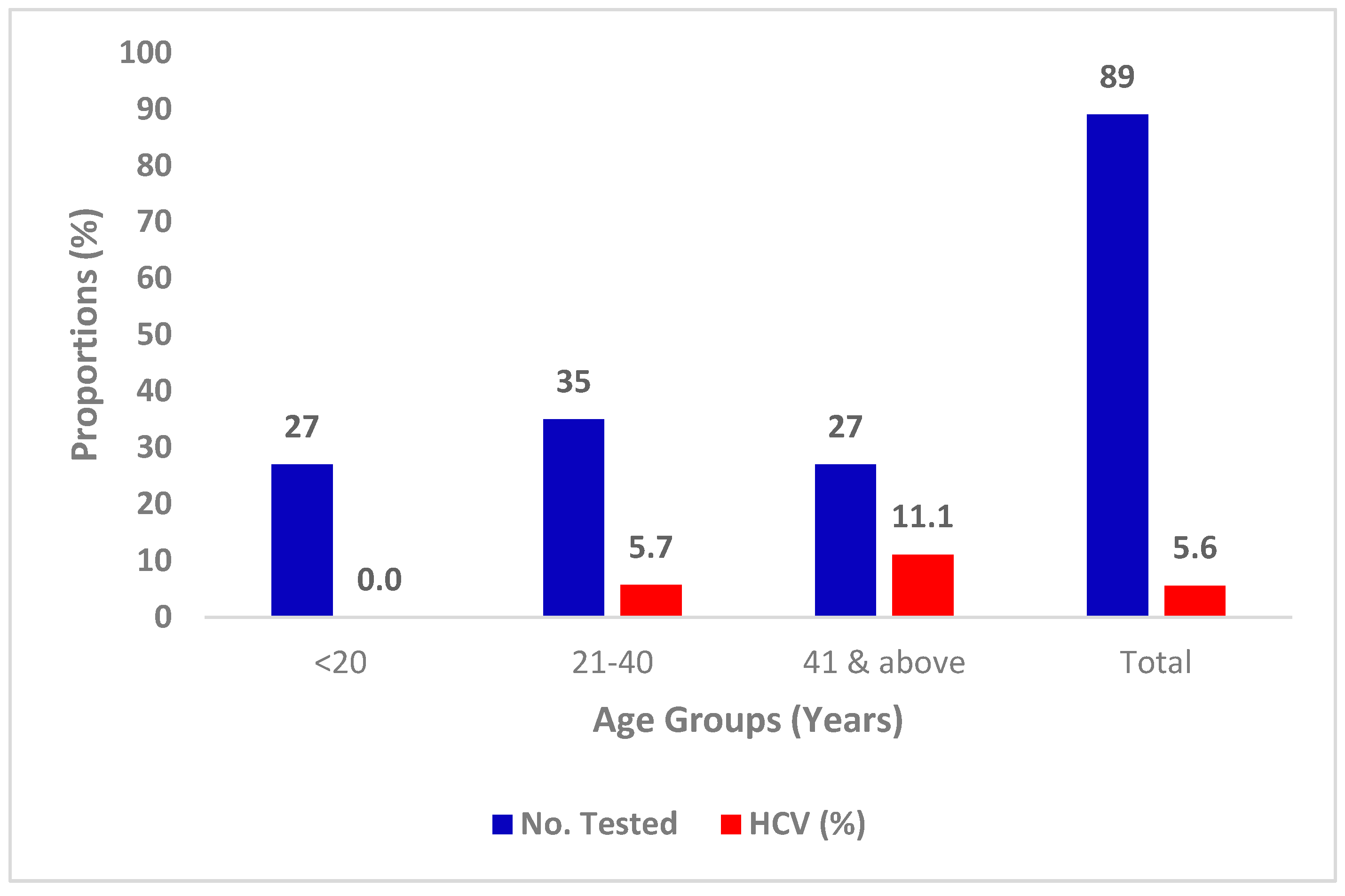

3.3. Prevalence of HCV with Age

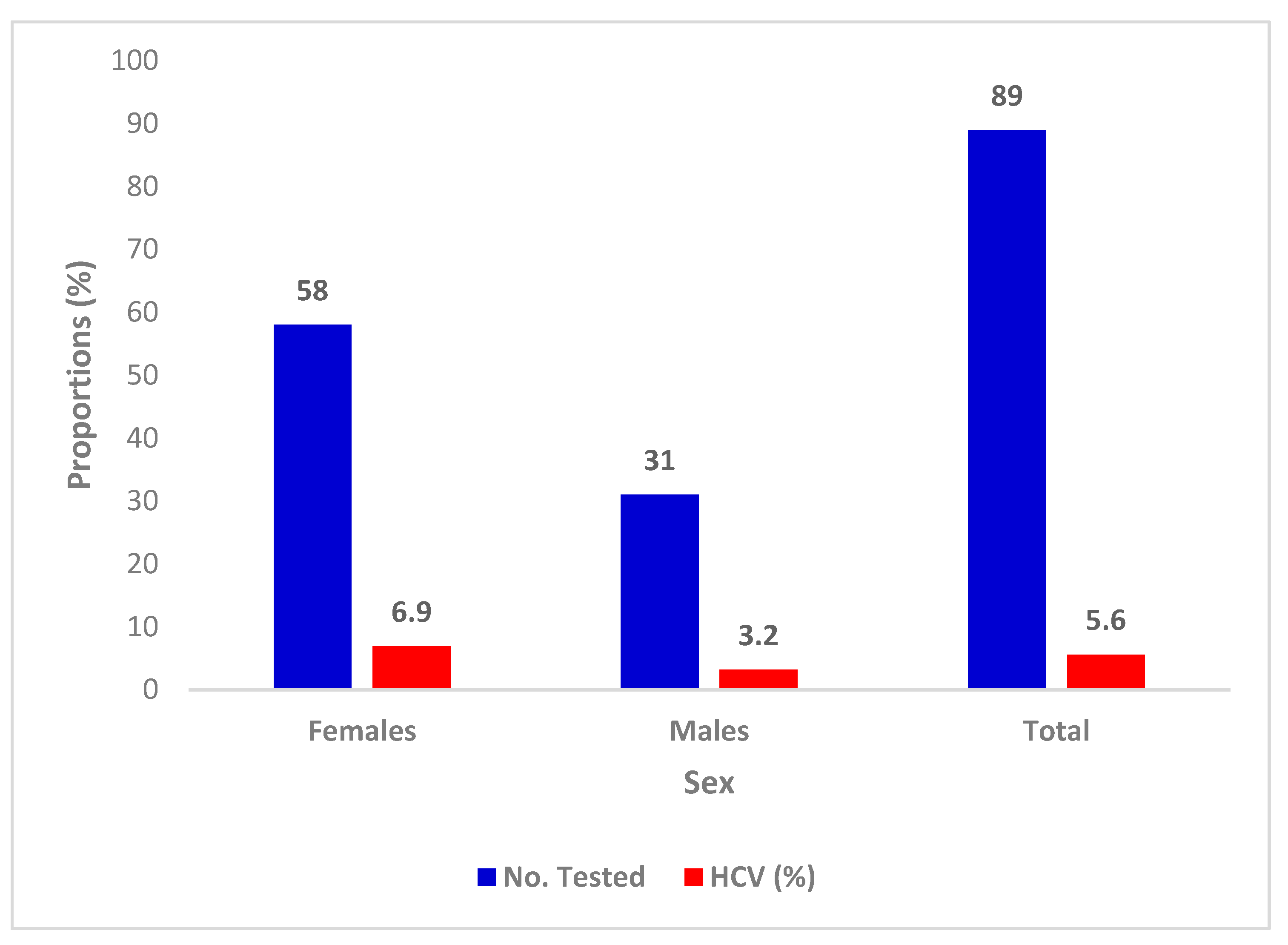

3.4. Prevalence of HCV with Sex

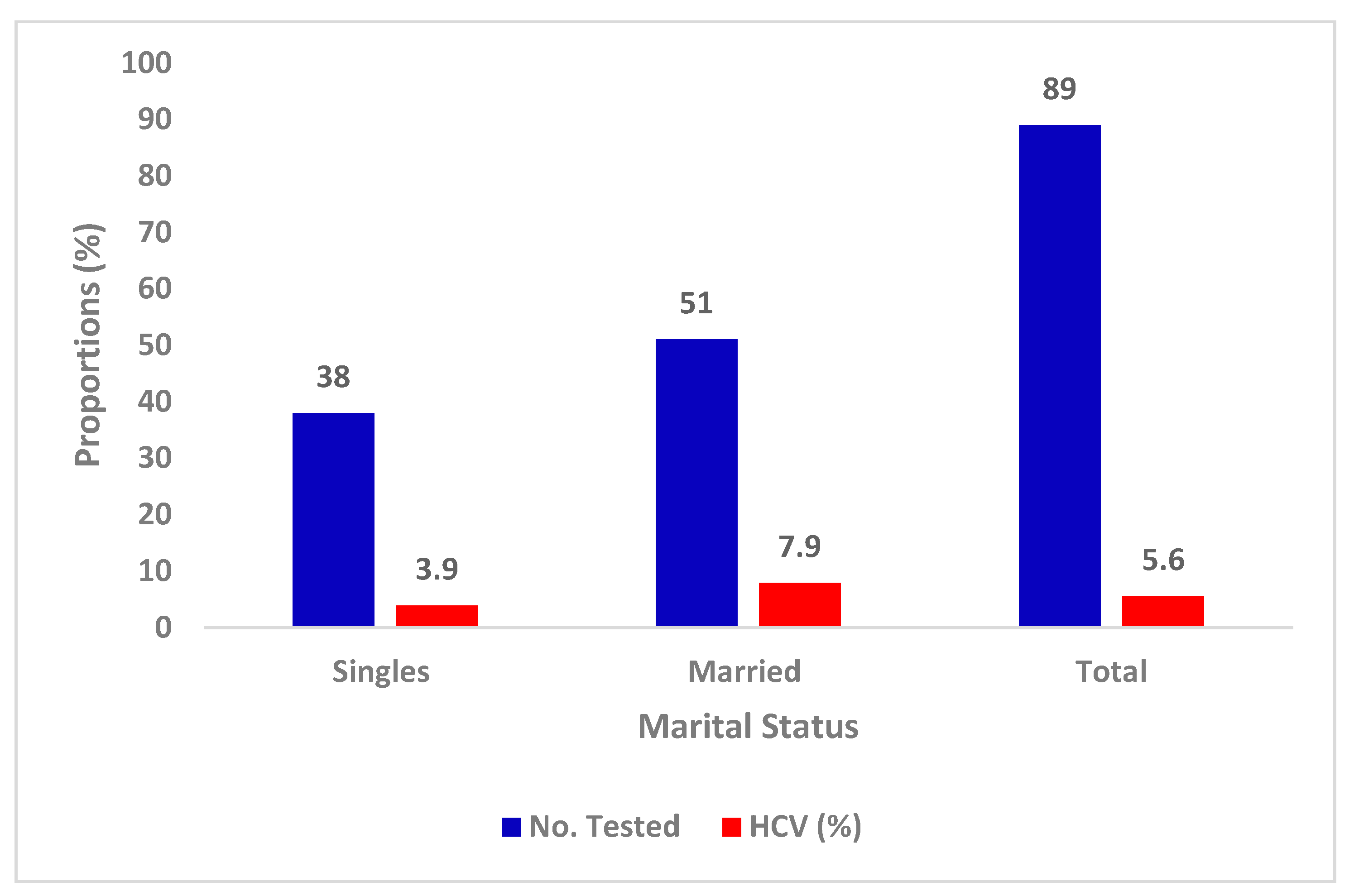

3.5. Prevalence of HCV with Marital Status

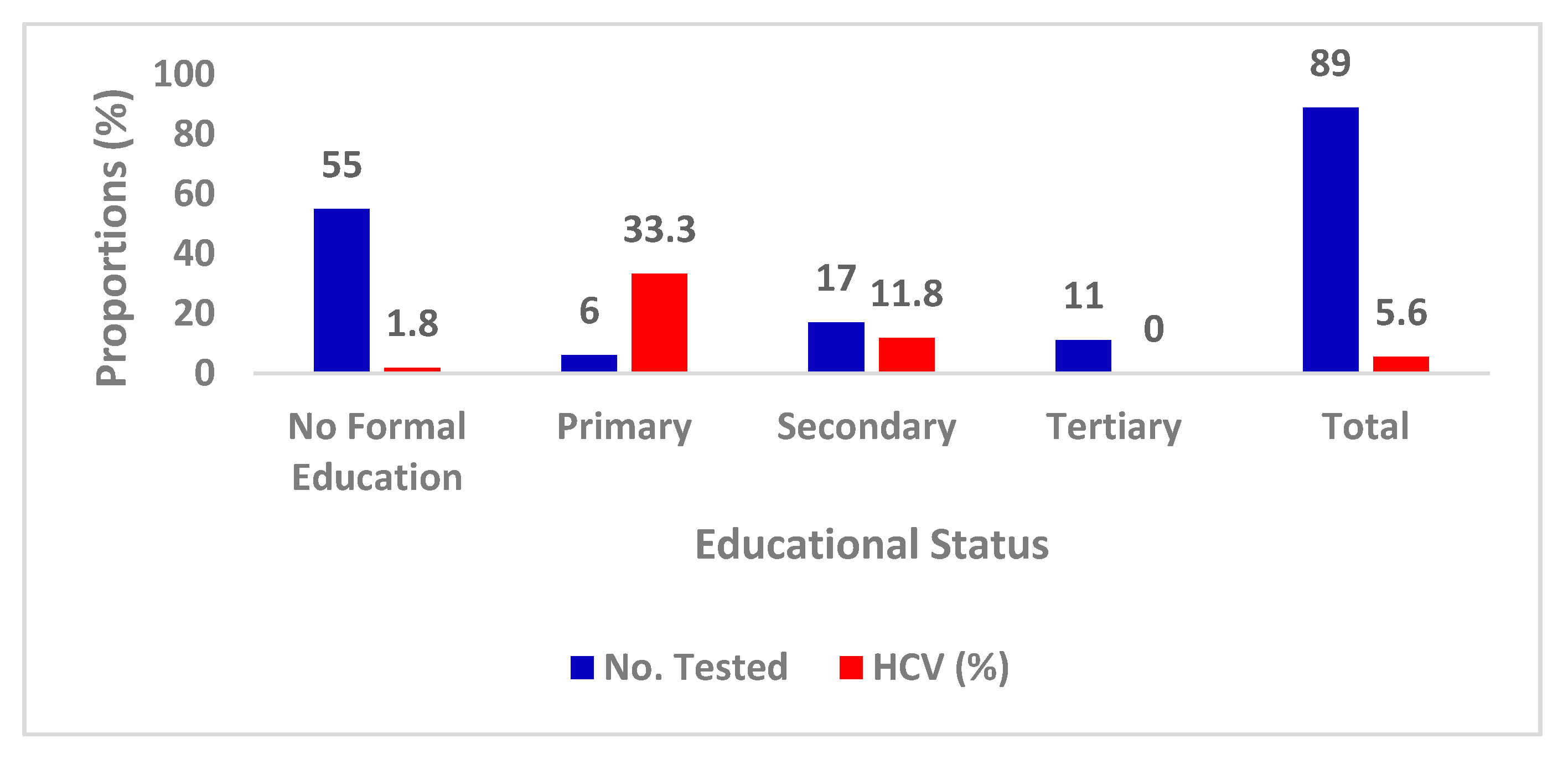

3.6. Prevalence of HCV with Educational Status

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Compliance with ethical standards

Acknowledgements

Disclosure of conflict of interest

Statement of ethical approval

Statement of informed consent

References

- Aaron, U. U., Okonko, I. O. & Frank-Peterside, N. (2021). The Prevalence of Hepatitis E, Hepatitis C and Hepatitis B Surface Antigenemia in HAART Experienced People Living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) in Rivers State, Nigeria. Journal of Biomedical Sciences 10(S4):001.

- Abeni, B.A., Frank-Peterside, N., Agbagwa, O.E., Adewuyi, S.A., Cookey, T.I. & Okonko, I.O. (2020). Seropositivity of Hepatitis C Virus Among Intending Blood Donors in Rivers State, Nigeria. Asian Journal of Research and Reports in Gastroenterology 3(3): 24-31.

- Acquaye, J. K. & Tettey-Donkor, D. (2000). frequency of hepatitis C virus antibodies and elevated serum alanine transaminase levels in Ghanaian blood donors. West Africa Journal Medical, 19 (4), 239–241.

- Adesina OA, Akinyemi JO, Ogunbosi BO, Michael OS, Awolude OA, & Adewole IF (2016). Seroprevalence and factors associated with hepatitis C coinfection among HIV-positive pregnant women at the University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria. Tropical Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 33, 153-158. [CrossRef]

- Afolabi AY, Abraham A, Oladipo EK, Adefolarin AO, Fagbami AH. Transfusion transmissible viral infections among potential blood donors in Ibadan, Nigeria. African Journal of Clinical and Experimental Microbiology. 2013;14(2):84-87. [CrossRef]

- Agboghoroma CO, Ukaire BC. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Hepatitis C Virus Infection among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Care at a Tertiary Hospital in Abuja, Nigeria. Nigerian Medical Journal. 2020;61(5):245-251. [CrossRef]

- Akinbami AA, Oshinaike OO, Adeyemo TA, Adediran A, Oshikomaiya BI, Ismail KA. Seroprevalence of hepatitis C infection in HIV patients using a rapid one-step test strip kit. Nigerian Quarterly Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2010;20(3):144-146.

- Alli JA, Okonko IO, Abraham OA, Kolade AF, Ogunjobi PI, Tonade OO, et al. A serosurvey of blood parasites (Plasmodium, Microfilaria, HIV, HBsAg, HCV antibodies) in prospective Nigerian blood donors. Research Journal in Medical Sciences. 2010;4(4):255-275. [CrossRef]

- Anyanwu CJN, Sunmonu PT, Mathew MH. Viral hepatitis B and C coinfection with Human Immunodeficiency Virus among adult patients attending selected highly active anti-retroviral therapy clinics in Nigeria's capital. Journal of Immunoassay and Immunochemistry. 2020;41(2):171-183. [CrossRef]

- Ayele, W., D. J. Nokes, A. Abebe, T. Messele, A. Dejene, F. Enquselassie, T. F. Rinke de Wit, and A. L. Fontanet. Higher prevalence of anti-HCV antibodies among HIV-positive compared to HIV-negative inhabitants of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. J. Med. Virol., 2002; 68: 12-17. [CrossRef]

- Ayolabi CL, Taiwo MA, Omilabu SA, Abebisi AO, Fatoba OM. Sero-prevalence of hepatitis C virus among donors in Lagos, Nigeria. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2006;5:1944-6.

- Bala JA, Kawo AH, Muktar MD, Sarki A, Magaji N, Aliyu IA. Prevalence of hepatitis C infection among blood donors in some selected hospitals in Kano, Nigeria. International Resource Journal of Microbiology. 2012;3:21722.

- Balogun, T. M., S. Emmanuel, and E. F. Ojerinde. HIV, Hepatitis B and C viruses’ coinfection among patients in a Nigerian tertiary hospital. Pan Afr. Med. J., 2012; 12.

- Buseri FI, Muhibi MA, Jeremiah JA. Seroepidemiology of transfusion-transmissible infectious diseases among blood donors in Osogbo, South-West Nigeria. Blood Transfusion. 2009;7(4):293-299. [CrossRef]

- Center for Disease Control & Prevention. (CDC, 2019). Viral hepatitis surveillance report—United States, 2017. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Service. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2017surveillance/index.htm. Published November 2019. Accessed 03 March 2023.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019 Viral Hepatitis Surveillance Report.

- https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/SurveillanceRpts.htm. Published July 2021. Accessed 03 March 2023.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral Hepatitis Surveillance Report – United States, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2020surveillance/index.htm. Published September 2022. Accessed 03 March 2023.

- Center for Disease Control & Prevention. (CDC, 1998). Recommendations for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Infection and HCV-Related Chronic Disease. Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Reports, Recommendations and Reports, 47(RR19): 1-39.

- Cookey, T. I., Okonko, I. O. & Frank-Peterside, N. (2021). Zero Prevalence of HIV and HCV Coinfection in the Highly HIV-infected Population of Rivers State, Nigeria. Asian Journal of Research in Medical and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 10(3): 9-16. [CrossRef]

- Dammulak OD, Pina TO, Joseph DE, Ogbenna AA, Kut SD, Godit P. Hepatitis C virus antibody among blood donors: the experience in a Nigerian blood transfusion centre. Global Advance Resource Journal of Medical Science. 2013;2:108–13.

- Diop-Ndiaye, H., C. Toure-Kane, J. F. Etard, G. Lo, P. Diaw, N. F. Ngom-Gueye, P. M. Gueye, K. Ba-Fall, I. Ndiaye, P. S. Sow, E. Delaporte, and S. Mboup. Hepatitis B, C seroprevalence and delta viruses in HIV-1 Senegalese patients at HAART initiation (retrospective study). J. Med. Virol., 2008; 80: 1332-1336. [CrossRef]

- Diwe CK, Okwara EC, Enwere OO, Azike JE, Nwaimo NC. Sero-prevalence of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus among HIV patients in a suburban University Teaching Hospital in South-East Nigeria. Pan African Medical Journal. 2013;16:7. [CrossRef]

- Ebie JC, Pela OA. Some sociocultural aspects of the problem of drug abuse in Nigeria. Drug and Alc. Dep. 2006;8:301-306. [CrossRef]

- Egah DZ, Mandong BM, Iya D, Gomwalk NE, Audu ES, Banwat EB, Onile BA. Hepatitis C virus antibodies among blood donors in Jos, Nigeria. Annals of African Medicine. 2004;3(1):35-37.

- Ejele OA, Erhabor O, Nwanche CA. The risk of acquired hepatitis C virus infection among blood donors in Port Harcourt: The question of blood safety in Nigeria. Nigeria Journal of Clinical Practices. 2006;9:18–21.

- Ejele, O. A., Nwauche, C. A., & Erhabor, O. (2006). Seroprevalence of hepatitis C virus in the Niger Delta of Nigeria. The Nigerian postgraduate medical journal, 13(2), 103-106. [CrossRef]

- Ernest Nwagwu, H. C. (2021). Prevalence of Hepatitis C Virus among Febrile Patients Attending a General Hospital in Emohua LGA, Rivers State, Nigeria. A Postgraduate Diploma Project in the Department of Microbiology, University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Nigeria.

- Frank J, Hassan Y, Grassucci RA. Hepatitis C virus-like internal ribosome entry site displaces elf 3 to gain access to the 40S subunit. Nature. 2013;503(7477): 539-543. [CrossRef]

- Halim NKD, Ajayi OI. Risk factors and seroprevalence of Hepatitis C antibody in blood donors in Nigeria. East Africa Medical Journal. 2000;77(8):410-412.

- Hamza M, Samaila AA, Yakasai AM, Babashani M, Borodo MM, Habib AG. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C virus infections among HIV-infected patients in a tertiary hospital in North-Western Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Basic and Clinical Sciences. 2013;10:76-81. [CrossRef]

- Ikeako LC, Ezegwui HU, Ajah LO, Dim CC, Okeke TC. Seroprevalence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus, Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, syphilis, and coinfections among antenatal women in a tertiary institution in the south-east, Nigeria. Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research. 2014;4(6). [CrossRef]

- Imoru, M., Eke, C., & Adegoke, A. (2003). Prevalence of Hepatitis-B Surface Antigen (HbsAg), Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) among Blood Donors in Kano State, Nigeria. Journal of Medical Laboratory Science, 12(1), 59-63. [CrossRef]

- Inyama P U, Uneke C J, Anyanwu G I, Njoku O M, Idoko J H, Idoko J A. Prevalence of antibodies to Hepatitis C virus among Nigerian patients with HIV infection. Online J Hlth Allied Scs. 2005;2:2. [CrossRef]

- Jemilohun, A. C., Oyelade, B. O., & Oiwoh, S. O. (2014). Prevalence of Hepatitis C virus antibody among undergraduates in Ogbomoso, Southwestern Nigeria. African Journal of infectious Diseases, 8(2), 40-43. [CrossRef]

- Jeremiah, Z. A., Koate, B., Buseri, F., & Emelike, F. (2008). Prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis C virus in apparently healthy Port Harcourt blood donors and association with blood groups and other risk indicators. Blood Transfusion, 6(3), 150. [CrossRef]

- Kamande MW, Kibebe H, Mokua J. Prevalence of transfusion transmissible infections among blood donated at Nyeri satellite transfusion Centre in Kenya. IOSR Journal of Pharmacists. 2016;6:20–30.

- Karoney, M. J., & Siika, A. M. (2013). Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in Africa: a review. Pan African medical journal, 14(1). [CrossRef]

- Kassim OD, Oyekale TO, Aneke JC, Durosinmi MA. Prevalence of seropositive blood donors for hepatitis B, C and HIV viruses at the Federal Medical Centre, Ado-Ekiti Nigeria. Ann Trop Pathol. 2012; 3:47–55.

- Kesson AM (2002).Diagnosis and Management of paediatric hepatitis C infection. Journal Paediatr child health; 38: 213–218. [CrossRef]

- Klevens, R. M., Miller, J., Vonderwahl, C., Speers, S., Alelis, K., Sweet, K., & Gallagher, K. (2009). Population-based surveillance for hepatitis C virus, United States, 2006–2007. Emerging infectious diseases, 15(9), 1499. [CrossRef]

- Koate BBD, Buseri FI, Jeremiah ZA. Seroprevalence of hepatitis C virus among blood donors in Rivers State, Nigeria. Transfusion Medicine. 2005;15:449-451. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. R., Kardos, K. W., Schiff, E., Berne, C. A., Mounzer, K., Banks, A. T., ... & Roehler, M. (2011). Evaluation of a new, rapid test for detecting HCV infection, suitable for use with blood or oral fluid. Journal of virological methods, 172(1-2), 27-31. [CrossRef]

- Lesi, O. A., M. O. Kehinde, D. N. Oguh, and C. O. Amira. Hepatitis B and C virus infection in Nigerian patients with HIV/AIDS. Niger. Postgrad. Med. J., 2007; 14: 129–133. [CrossRef]

- Muriuki, B. M., M. M. Gicheru, D. Wachira, A. K. Nyamache, and S. A. Khamadi. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C viral coinfections among HIV-1 infected individuals in Nairobi, Kenya. BMC Research Notes, 2013; 6: 363. [CrossRef]

- Nagu, T. J., M. Bakari, and M. Matee. Hepatitis A, B and C viral coinfections among HIV-infected adults presenting for care and treatment at Muhimbili National Hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Public Health, 2008; 8: 416. [CrossRef]

- Nwannadi IA, Alao O, Shoaga L. Hepatitis C among blood donors in teaching hospital in North Central Nigeria. IOSR Journal of Dental Medical Science. 2014;13:20–3.

- Nwannadi, I. A., Alao, O. O., Bazuaye, G. N., Omoti, C. E., & Halim, N. K. (2012). Seroprevalence of hepatitis C virus antibodies in sickle cell anaemia patients in Benin City, Nigeria. Gomal Journal of Medical Sciences, 10(1).

- Obienu, O., Nwokediuko, S., Malu, A., & Lesi, O. A. (2011). Risk factors for Hepatitis C virus transmission obscure in Nigerian patients. Gastroenterology research and practice, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Ogbodo, E. N., Otue A. & Okonko, I. O. (2015). Anti-HCV antibody among newly diagnosed HIV patients in Ughelli, a suburban area of Delta State Nigeria. African Health Sciences 15(3):728-736. [CrossRef]

- Ogwu-Richard SO, Ojo DA, Akingbade OA, Okonko IO. Triple positivity of HBsAg, anti-HCV antibody, and HIV and their influence on CD4+ lymphocyte levels in the highly HIV infected population of Abeokuta, Nigeria. African Health Sciences. 2015;15(3):719-727. [CrossRef]

- Ojide CK, Kalu EI, Ogbaini-Emevon E, Nwadike VU. Coinfections of hepatitis B and C with human immunodeficiency virus among adult patients attending human immunodeficiency virus outpatients clinic in Benin City, Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice. 2015;18(4):516-521. [CrossRef]

- Okocha EC, Aneke JC, Ezeh TU, Ibeh NC, Nwosu GA, Okorie IO. The epidemiology of transfusion-transmissible infections among blood donors in Nnewi, South-East Nigeria. African Journal of Medical Health Science. 2015;14:125–9. [CrossRef]

- Okonko, I. O., Ikunga, C. V., Anugweje, K. C. & Okerentugba, P. O. (2014). Anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibody detection among fresh undergraduate students in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Basic Sciences of Medicine, 3(2): 26–29.

- Okonko IO, Cookey TI & Innocent-Adiele HC. (2022). Dual positivity of HIV and anti-HCV in the highly infected population of Rivers State, Nigeria. International Journal of Scientific Research Updates, 04(02), 039–048. [CrossRef]

- Okonko IO, Oyediji TO, Anugweje KC, Adeniji FO, Alli JA, Abraham OA. Detection of HCV antibody among intending blood donors. Nature and Science. 2012;10(1): 53-58.

- Okoroiwu HU, Okafor IM, Asemota EA, Okpokam DC. Seroprevalence of transfusion-transmissible infections (HBV, HCV, syphilis and HIV) among prospective blood donors in a tertiary health care facility in Calabar, Nigeria; An eleven years evaluation. BMC Public Health. 2018;18: 645. [CrossRef]

- Oluremi AS, Opaleye OO, Ogbolu DO, Alli OAT, Ashiru FT, Alaka OO, et al. Serological evidence of HIV, Hepatitis B, C, and E viruses among liver disease patients attending tertiary hospitals in Osun State, Nigeria. Journal of Immunoassay and Immunochemistry. 2021;42(1): 69-81. [CrossRef]

- Omatola CA, Lawal C, Omosayin DO, Okolo MO, Adaji DM, Mofolorunsho CK, Bello KE. Seroprevalence of HBV, HCV, and HIV and Associated Risk Factors Among Apparently Healthy Pregnant Women in Anyigba, Nigeria. Viral immunology. 2019;32(4):186-191. [CrossRef]

- Omolade O, Adeyemi A. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus antibody among university students in Nigeria. Journal of Virus Eradication. 2018;4(4):228–229. [CrossRef]

- Onyekwere CA, Hameed L. Hepatitis B and C virus prevalence and association with demographics: report of population screening in Nigeria. Tropical Doctor. 2015;45(4):231-235. [CrossRef]

- Onyekwere, C. A., Ogbera, A. O., Dada, A. O., Adeleye, O. O., Dosunmu, A. O., Akinbami, A. A., ... & Hameed, O. (2016). Hepatitis C virus (HCV) prevalence in special populations and associated risk factors: A report from a tertiary hospital. Hepatitis monthly, 16(5). [CrossRef]

- Opaleye OO, Igboama MC, Ojo JA, Odewale G. Seroprevalence of HIV, HBV, HCV, and HTLV among Pregnant Women in Southwestern Nigeria. Journal of Immunoassay and Immunochemistry. 2016;37(1):29-42. [CrossRef]

- Parboosing, R., I. Paruk, and U. G. Lalloo. Hepatitis C virus seropositivity in a South African Cohort of HIV co-infected, ARV naive patients is associated with renal insufficiency and increased mortality. J. Med. Virol., 2008; 80: 1530-1536. [CrossRef]

- Patrick, S. W., Bauer, A. M., Warren, M. D., Jones, T. F., & Wester, C. (2017). Hepatitis C virus infection among women giving birth—Tennessee and United States, 2009–2014. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 66(18), 470. [CrossRef]

- Riou J, Aït Ahmed M., Blake A, Vozlinsky S, Brichler S, Eholié S, Boëlle PY, Fontanet A. HCV epidemiology in Africa group hepatitis C virus seroprevalence in adults in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Viral Hepatitis. 2016;23:244–255. [CrossRef]

- Schillie SF, Canary L, Koneru A, et al. Hepatitis C virus in women of childbearing age, pregnant women, and children. Am J Prev Med 2018;55:633–41. [CrossRef]

- Schillie, S., Wester, C., Osborne, M., Wesolowski, L., & Ryerson, A. B. (2020). CDC recommendations for hepatitis C screening among adults—United States, 2020. MMWR Recommendations and Reports, 69(2), 1. [CrossRef]

- Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, et al. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945-1965. MMWR Recomm Rep 2012;61(RR-4):1–32.

- Spradling, P. R., J. T. Richardson, K. Buchacz, A. C. Moorman, L. Finelli, B. P. Bell, and J. T. Brooks. Trends in hepatitis C virus infection among patients in the HIV Outpatient Study, 1996-2007. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr., 2010; 53: 388-396. [CrossRef]

- Strickland GT. HCV in developing Countries. Postgrad. Doc. (Africa). 2002; 24:18-20.

- Syed-Mohammed J, Stuart CG (2018). Epidemiology of Hepatitis C. Clinical Liver Disease; 12(5):140–142.

- Te HS, Jensen DM (2001). Epidemiology of hepatitis B and C viruses: A global overview. Clin Liver Dis; 14(1):1-21. [CrossRef]

- Tessema, B., Yismaw, G., Kassu, A., Amsalu, A., Mulu, A., Emmrich, F., & Sack, U. (2010). Seroprevalence of HIV, HBV, HCV and syphilis infections among blood donors at Gondar University Teaching Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: declining trends over a period of five years. BMC Infectious diseases, 10(1), 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Tohme, R. A. A. H., S. D. Is sexual contact a major mode of hepatitis C virus transmission? Hepatology, 2010; 1497–1505. [CrossRef]

- Tremeau-Bravard A, Ogbukagu IC, Ticao CJ, Abubakar JJ. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C infection among the HIV-positive population in Abuja, Nigeria. African Health Sciences. 2012;12(3):312-317. [CrossRef]

- Tsai HC, Chou PY, Wann SR, Lee SSJ, Chen YS. (2015). Chemokine co-receptor usage in HIV-1-infected treatment-naïve voluntary counselling and testing clients in Southern Taiwan. BMJ Open. 2015;5(4):e007334. [CrossRef]

- Udeze, A. O., Bamidele, R. A., Okonko, I. O., and Sule, W. F. (2011). Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Antibody Detection Among First Year Students of University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria. World J of Med Sci. 6.162-167.

- Udeze, A. O., Okonko, I. O., Donbraye, E., Sule, W. F., Fadeyi, A. and Uche, L. N. (2009). Seroprevalence of Hepatitis C Virus Antibodies Amongst Blood Donors in Ibadan, Southwestern Nigeria. World ApplSci J., 7: 1023-1028.

- Walana W, Ahiaba S, Hokey P, Vicar EK, Acquah SEK, Der EM. Seroprevalence of HIV, HBV and HCV among blood donors in Kintampo municipal hospitals, Ghana. Br Microbiology Resource Journal. 2014;12: 1491–9.

- World Health Organization (WHO, 1999). Global surveillance and control of hepatitis C. Report of a WHO Consultation organized in collaboration with the Viral Hepatitis Prevention Board, Antwerp, Belgium. J Viral Hepatitis, 6.35-47.

| Characteristics | Categories | No. Tested | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | 2-20 | 27 | 30.3 |

| 21-40 | 35 | 39.3 | |

| 41 & above | 27 | 30.3 | |

| Gender | Females | 58 | 65.1 |

| Males | 31 | 34.8 | |

| Marital status | Married | 51 | 57.3 |

| Single | 38 | 42.7 | |

| Educational | No formal | 55 | 61.7 |

| Primary | 6 | 6.7 | |

| Secondary | 17 | 19.2 | |

| University | 11 | 12.4 | |

| Total | 89 | 100.0 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).