Submitted:

03 March 2023

Posted:

03 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy

2.2. Eligibility criteria

2.3. Data extraction

3. Results

3.1. Dietary intake, nutritional status and OSA

3.2. Serum nutritional biomarkers and OSA/OSO

3.3. Physical Activity and OSA

4. Discussion

4.1. Dietary intake, nutritional status and OSA

4.2. Serum nutritional biomarkers and OSA/OSO

4.3. Physical Activity and OSA

5. Summary and Conclusions

6. Existing Problems and Recommendations for Future Studies

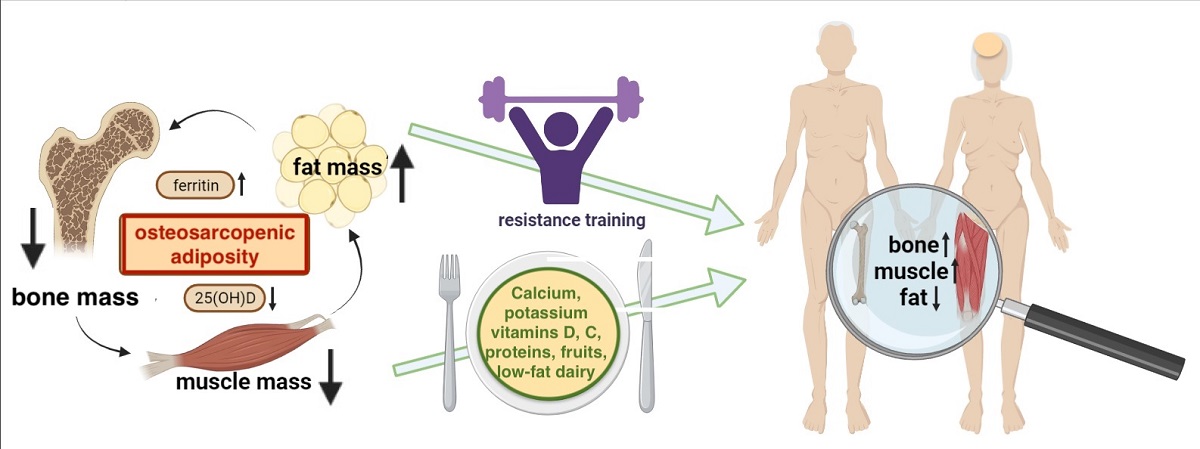

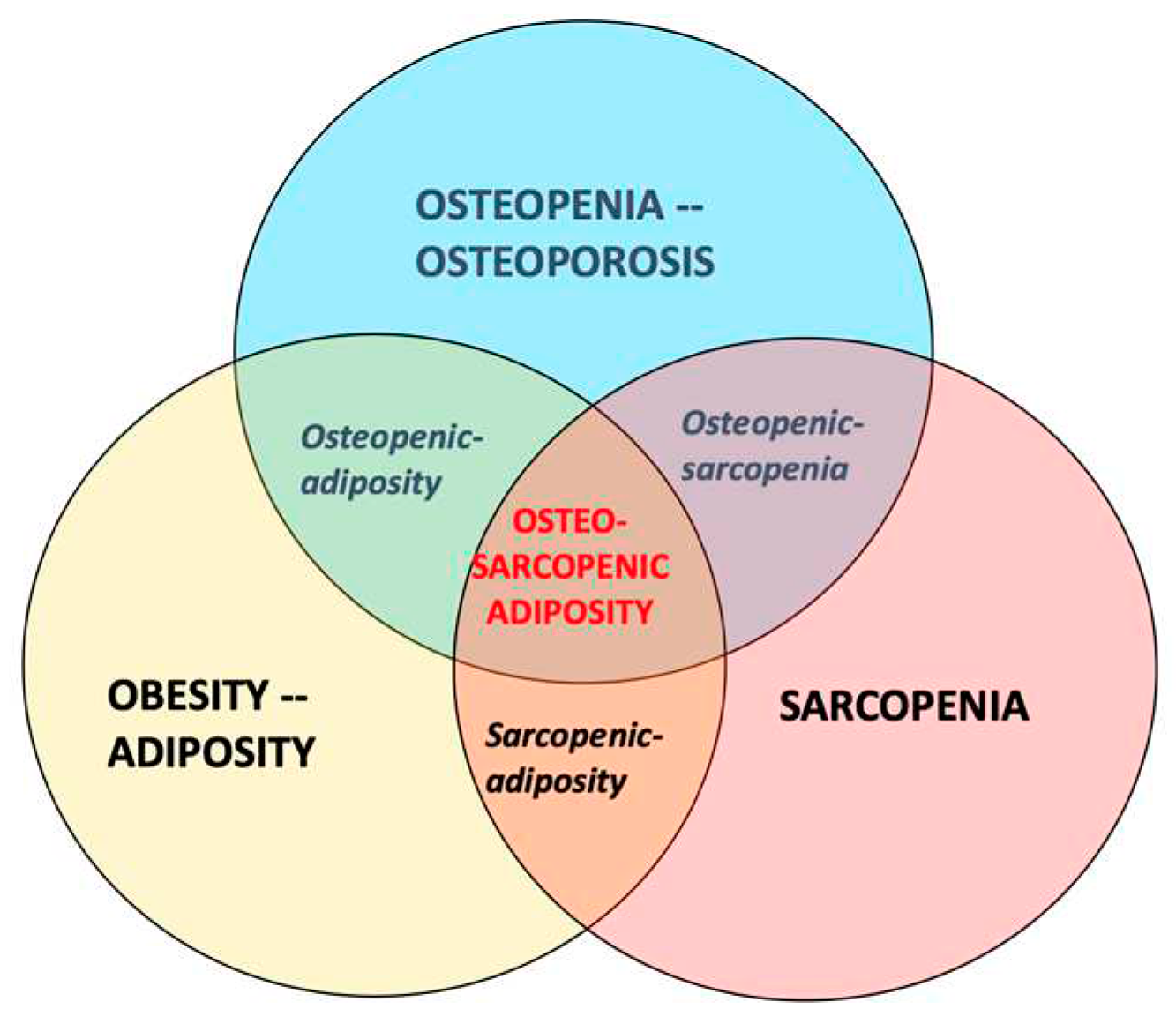

- The participants with OSA should be compared with those having osteopenia/osteoporosis, osteopenic adiposity, sarcopenia, sarcopenic adiposity, osteopenic sarcopenia, adiposity-alone or normal-body composition parameters (see Figure 1 for the combination of conditions). This will provide a clearer picture about OSA itself and all the differences between other body composition impairments.

- Individuals of different sex (as of now, women are studied more frequently than men), age, and race/ethnicities (e.g., there are no studies in African Americans), as well as critical populations (like nursing home residents), are needed to better define the diagnostic criteria, and to elucidate OSA. While majority of the studies have been done in older population, equally important would be the studies in younger individuals, as the earlier work identified prevalent OSA phenotype in healthy, young, obese individuals [62].

- The potential breakthrough could be the development of biomarkers for each tissue which in combination may indicate the existing impairments and presence of OSA. A pilot study showed increased levels of serum sclerostin (bone resorption marker), skeletal muscle troponin (muscle breakdown marker), and inferior lipid profile and increased leptin in women with OSA compared to their counterparts with only one or two impaired body composition components [63]. However, more refinement is necessary, and the series of omics will need to be determined to serve as potential biomarkers.

- Likewise, in view of the swift technological advances, such as genomic sequencing and molecular targeted drug exploitation, the concept of precision medicine can be used to demarcate OSA using multiple data sources from genomics to digital health metrics, to artificial intelligence in order to facilitate an individualized yet “evidence-based” decisions regarding diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. In this way, therapeutics can be centered toward patients based on their molecular presentation rather than grouping them into broad categories with a “one size fits all” approach.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ilich, J.Z.; Kelly, O.J.; Inglis, J.E.; Panton, L.B.; Duque, G.; Ormsbee, M.J. Interrelationship among muscle, fat, and bone: connecting the dots on cellular, hormonal, and whole body levels. Ageing Res. Rev. 2014, 15, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilich, J.Z.; Gilman, J.C.; Cvijetic, S.; Boschiero, D. Chronic Stress Contributes to Osteosarcopenic Adiposity via Inflammation and Immune Modulation: The Case for More Precise Nutritional Investigation. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donini, L.M.; Pinto, A.; Giusti, A.M.; Lenzi, A.; Poggiogalle, E. Obesity or BMI Paradox? Beneath the Tip of the Iceberg. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Johansson, J.; Ebeling, P.R.; Nordstrom, P.; Nordstrom, A. Adiposity Without Obesity: Associations with Osteoporosis, Sarcopenia, and Falls in the Healthy Ageing Initiative Cohort Study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2020, 28, 2232–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsic, A.; Takic, M.; Kojadinovic, M.; Petrovic, S.; Paunovic, M.; Vucic, V.; Ristic Medic, D. Metabolically healthy obesity: is there a link with polyunsaturated fatty acid intake and status? Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2021, 99, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilich, J.Z.; Kelly, O.J.; Inglis, J.E. Osteosarcopenic Obesity Syndrome: What Is It and How Can It Be Identified and Diagnosed? Curr. Gerontol. Geriatr. Res. 2016, 2016, 7325973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, O.J.; Gilman, J.C.; Boschiero, D.; Ilich, J.Z. Osteosarcopenic Obesity: Current Knowledge, Revised Identification Criteria and Treatment Principles. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilich, J.Z. Nutritional and Behavioral Approaches to Body Composition and Low-Grade Chronic Inflammation Management for Older Adults in the Ordinary and COVID-19 Times. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JafariNasabian, P.; Inglis, J.E.; Reilly, W.; Kelly, O.J.; Ilich, J.Z. Aging human body: changes in bone, muscle and body fat with consequent changes in nutrient intake. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 234, R37–R51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilich, J.Z. Osteosarcopenic adiposity syndrome update and the role of associated minerals and vitamins. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2021, 80, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, O.J.; Gilman, J.C. Can Unconventional Exercise be Helpful in the Treatment, Management and Prevention of Osteosarcopenic Obesity? Curr. Aging Sci. 2017, 10, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-M.; Ye, H.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, J.-H.; Liu, Q.-Q.; Xie, H.-Y.; Long, Y.; Huang, H.; Niu, Y.-L.; Luo, Y.; et al. Effects of resistance training on body composition and physical function in elderly patients with osteosarcopenic obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Osteoporos. 2022, 17, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Lee, Y.; Kye, S.; Chung, Y.-S.; Kim, J.-H.; Chon, D.; Lee, K.E. Diet quality and osteosarcopenic obesity in community-dwelling adults 50 years and older. Maturitas 2017, 104, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvijetić, S.; Keser, I.; Boschiero, D.; Ilich, J.Z. Osteosarcopenic Adiposity and Nutritional Status in Older Nursing Home Residents during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keser, I.; Cvijetić, S.; Ilić, A.; Colić Barić, I.; Boschiero, D.; Ilich, J.Z. Assessment of Body Composition and Dietary Intake in Nursing-Home Residents: Could Lessons Learned from the COVID-19 Pandemic Be Used to Prevent Future Casualties in Older Individuals? Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, M.-K.; Bae, Y.-J. Dietary calcium, phosphorus, and osteosarcopenic adiposity in Korean adults aged 50 years and older. Arch. Osteoporos. 2021, 16, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi MK, Bae YJ. Protein intake and osteosarcopenic adiposity in Korean adults aged 50 years and older. Osteoporos Int. 2020, 31, 2363–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Y.-J. Fruit intake and osteosarcopenic obesity in Korean postmenopausal women aged 50-64 years. Maturitas 2020, 134, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de França, N.A.G.; Peters, B.S.E.; dos Santos, E.A.; Lima, M.M.S.; Fisberg, R.M.; Martini, L.A. Obesity Associated with Low Lean Mass and Low Bone Density Has Higher Impact on General Health in Middle-Aged and Older Adults. J. Obes. 2020, 2020, 8359616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Na, W.; Sohn, C. Relationship between osteosarcopenic obesity and dietary inflammatory index in postmenopausal Korean women: 2009 to 2011 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2018, 63, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilich, J.Z.; Kelly, O.J.; Liu, P.-Y.; Shin, H.; Kim, Y.; Chi, Y.; Wickrama, K.K.A.S.; Colic-Baric, I. Role of Calcium and Low-Fat Dairy Foods in Weight-Loss Outcomes Revisited: Results from the Randomized Trial of Effects on Bone and Body Composition in Overweight/Obese Postmenopausal Women. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilich, J.Z.; Liu, P.-Y.; Shin, H.; Kim, Y.; Chi, Y. Cardiometabolic Indices after Weight Loss with Calcium or Dairy Foods: Secondary Analyses from a Randomized Trial with Overweight/Obese Postmenopausal Women. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervo, M.M.; Shivappa, N.; Hebert, J.R.; Oddy, W.H.; Winzenberg, T.; Balogun, S.; Wu, F.; Ebeling, P.; Aitken, D.; Jones, G.; et al. Longitudinal associations between dietary inflammatory index and musculoskeletal health in community-dwelling older adults. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority. Nutrient Recommendations: Dietary Reference Values (DRV). Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/interactive-pages/drvs.

- Nutrient Recommendations: Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI). Available online: https://ods.od.nih.gov/HealthInformation/Dietary_Reference_Intakes.aspx.

- Chung, S.-J.; Lim, H.S.; Lee, M.-Y.; Lee, Y.-T.; Yoon, K.J.; Park, C.-H. Sex-Specific Associations between Serum Ferritin and Osteosarcopenic Obesity in Adults Aged over 50 Years. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yuyan, L.; Shen, Z.; Lu, C.; Yu, He.; Shuai, X.; Hong, L.; Feng, Chen.; Jie Gao, D.W. Association of Serum 25-(OH)-D3 with Osteosarcopenic Obesity: A Cross-Sectional Study of Older Chinese. Res. Sq. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.M.; Kim, S.; Won, Y.J.; Kim, S.H. Clinical Manifestations and Factors Associated with Osteosarcopenic Obesity yndrome: A Cross-Sectional Study in Koreans with Obesity. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2019, 105, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, Y.; Kye, S.; Chung, Y.-S.; Lee, O. Association of serum vitamin D with osteosarcopenic obesity: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2008-2010. J. Cachexia. Sarcopenia Muscle 2017, 8, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.-H.; Lee, P.-H.; Lin, L.-F.; Liao, C.-D.; Liou, T.-H.; Huang, S.-W. Effects of progressive elastic band resistance exercise for aged osteosarcopenic adiposity women. Exp. Gerontol. 2021, 147, 111272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, P.M.; Ribeiro, A.S.; Tomeleri, C.M.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Silva, A.M.; Souza, M.F.; Nascimento, M.A.; Sardinha, L.B.; Cyrino, E.S. The effects of resistance training volume on osteosarcopenic obesity in older women. J. Sports Sci. 2018, 36, 1564–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banitalebi, E.; Ghahfarrokhi, M.M.; Dehghan, M. Effect of 12-weeks elastic band resistance training on MyomiRs and osteoporosis markers in elderly women with Osteosarcopenic obesity: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banitalebi, E.; Banitalebi, E.; Ghahfarokhi, M.M.; Rahimi, M.; Laher, I.; Davison, K. Resistance Band Exercise: An Effective Strategy to Reverse Cardiometabolic Disorders in Women With Osteosarcopenic Obesity. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2023, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banitalebi, E.; Faramarzi, M.; Ghahfarokhi, M.M.; SavariNikoo, F.; Soltani, N.; Bahramzadeh, A. Osteosarcopenic obesity markers following elastic band resistance training: A randomized controlled trial. Exp. Gerontol. 2020, 135, 110884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Huang, L.; Wang, L.; Chen, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, L.; Cao, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, J.; Y. S. Effects of 12 weeks aerobic exercise combined with high speed strength training on old adults with osteosarcopenic obesity syndrome. Chinese J. Rehabil. Med. 2020, 35, 420–426. [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi, A.; Soori, R.; Banitalebi, E.; Choobineh, S. The Effect of Elastic Resistance Bands Training on Vascular Aging Related Serum microRNA-146 Expression and Atherosclerosis Risk Factors in Elderly Women with Osteosarcopenic Obesity: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Iran. J. Diabetes Obes. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemipour, N.; Faramarzi, Mohammad Banitalebi, E. The Effect of 12 Weeks of Theraband Resistance Training on IGF-1 and FGF-2 Levels and Their Relationships with Myokines on Bone Mineral Density of Osteosarcopenic Obese Women. Jentashapir J. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2022, 13, e130641. [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 2013, 153, 1194–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmauck-Medina, T.; Molière, A.; Lautrup, S.; Zhang, J.; Chlopicki, S.; Madsen, H.B.; Cao, S.; Soendenbroe, C.; Mansell, E.; Vestergaard, M.B.; et al. New hallmarks of ageing: a 2022 Copenhagen ageing meeting summary. Aging (Albany. NY). 2022, 14, 6829–6839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health.

- Kanis, J.A. Diagnosis of osteoporosis and assessment of fracture risk. Lancet (London, England) 2002, 359, 1929–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper. C.; Landi, F.; Rolland. Y.; Sayer, A.A.; Schneider, S.M.; Sieber, C.C.; Topinkova, E., Vandewoude, M.; Visser, M.; Zamboni, M. Writing Group for the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2), and the Extended Group for EWGSOP2. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019 48, 601. Erratum for: Age Ageing. 2019 48, 16-31. PMID: 31081853; PMCID: PMC6593317. [CrossRef]

- Donini, L.M.; Busetto, L.; Bischoff, S.C.; Cederholm, T.; Ballesteros-Pomar, M.D.; Batsis, J.A.; Bauer, J.M.; Boirie, Y.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Dicker, D.; et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria for sarcopenic obesity: ESPEN and EASO consensus statement. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 990–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madeira, T.; Peixoto-Plácido, C.; Sousa-Santos, N.; Santos, O.; Alarcão, V.; Goulão, B.; Mendonça, N.; Nicola, P.J.; Yngve, A.; Bye, A.; et al. Malnutrition among older adults living in Portuguese nursing homes: the PEN-3S study. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauly, L.; Stehle, P.; Volkert, D. Nutritional situation of elderly nursing home residents. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2007, 40, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courtois-Amiot, P.; Allart, H.; de Cathelineau, C.; Legué, C.; Eischen, P.; Chetaille, F.; Lepineux, D.; Raynaud-Simon, A.; Sanchez, M. Covid-19 as an Independent Risk Factor for Weight Loss in Older Adults living in Nursing Homes. Gerontology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorning, T.K.; Raben, A.; Tholstrup, T.; Soedamah-Muthu, S.S.; Givens, I.; Astrup, A. Milk and dairy products: good or bad for human health? An assessment of the totality of scientific evidence. Food Nutr. Res. 2016, 60, 32527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veronese, N.; Stubbs, B.; Koyanagi, A.; Hébert, J.R.; Cooper, C.; Caruso, M.G.; Guglielmi, G.; Reginster, J.Y.; Rizzoli, R.; Maggi, S.; et al. Pro-inflammatory dietary pattern is associated with fractures in women: an eight-year longitudinal cohort study. Osteoporos Int. 2018, 1:143-151. [CrossRef]

- Deurenberg, P.; Deurenberg-Yap, M.; Guricci, S. Asians are different from Caucasians and from each other in their body mass index/body fat per cent relationship. Obes. Rev. 2002, 3, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Western Pacific. (2000). The Asia-Pacific perspective: redefining obesity and its treatment. Sydney: Health Communications Australia. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/206936.

- Arosio, P.; Levi, S. Ferritin, iron homeostasis, and oxidative damage. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002, 33, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hämäläinen, P.; Saltevo, J.; Kautiainen, H.; Mäntyselkä, P.; Vanhala, M. Serum ferritin levels and the development of metabolic syndrome and its components: a 6.5-year follow-up study. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2014, 6, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, L.J.; Berti, C.; Casgrain, A.; Cetin, I.; Collings, R.; Gurinovic, M.; Hermoso, M.; Hooper, L.; Hurst, R.; Koletzko, B.; et al. EURRECA-Estimating iron requirements for deriving dietary reference values. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 1064–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberg, E.D. Iron toxicity: new conditions continue to emerge. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2009, 2, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Filippo, L.; De Lorenzo, R.; Giustina, A.; Rovere-Querini, P.; Conte, C. Vitamin D in Osteosarcopenic Obesity. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewiecki, E.M. Osteoporosis: Clinical Evaluation. 2021. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, Hofland J, Kalra S, Kaltsas G, Kapoor N, Koch C, Kopp P, Korbonits M, Kovacs CS, Kuohung W, Laferrère B, Levy M, McGee EA, McLachlan R, New M, Purnell J, Sahay R, Singer F, Sperling MA, Stratakis CA, Trence DL, Wilson DP, editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000–. PMID: 25905277.

- Weilner, S.; Skalicky, S.; Salzer, B.; Keider, V.; Wagner, M.; Hildner, F.; Gabriel, C.; Dovjak, P.; Pietschmann, P.; Grillari-Voglauer, R.; et al. Differentially circulating miRNAs after recent osteoporotic fractures can influence osteogenic differentiation. Bone 2015, 79, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, J.; Dong, R. MicroRNA-146a and -21 cooperate to regulate vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation via modulation of the Notch signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 11, 2889–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JafariNasabian, P.; Inglis, J.E.; Kelly, O.J.; Ilich, J.Z. Osteosarcopenic obesity in women: impact, prevalence, and management challenges. Int. J. Womens. Health 2017, 9, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milošević, M.; Arsić, A.; Cvetković, Z.; Vučić, V. Memorable Food: Fighting Age-Related Neurodegeneration by Precision Nutrition. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 688086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ristic-Medic, D.; Kovacic, M.; Takic, M.; Arsic, A.; Petrovic, S.; Paunovic, M.; Jovicic, M.; Vucic, V. Calorie-Restricted Mediterranean and Low-Fat Diets Affect Fatty Acid Status in Individuals with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Nutrients 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanaki, C.; Peppa, M.; Boschiero, D.; Chrousos, G.P. Healthy overweight/obese youth: early osteosarcopenic obesity features. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2016, 46, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JafariNasabian., P.; Inglis, JE.; Ave, M.P.; Hall, K.J.; Nieto, S.E.; Kelly, O.J.; Ilich, J.Z. Metabolic Profile of Osteosarcopenic Obesity Syndrome: Identifying Biomarkers for Diagnostic Criteria. FASEB J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference, Studied topic |

Country Setting |

Study Design |

Diagnostic criteria & Instruments Bone Lean/Muscle Adipose |

Sample size, n (%) Intervention |

Age (years) | OSA/OSO Prevalence2 n (%) |

Assessment Tools |

Compared to3 | Outcomes in OSA/OSO group (or others if indicated) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cvijetic, S, 2023 [14], Nutritional status in nursing homes residents during COVID | Croatia, Six Nursing Homes |

C-S Inclus/Exclusion criteria applied |

T-score ≤-1 for total bone mass With BIA-ACC |

S-score ≤-1 With BIA- ACC |

BF%: F ≥32; M ≥25 With BIA- ACC |

Total, n=365; F, n=296 (81); M, n=69 (18.9) |

Mean, 83.7 F, 84.3 M, 83.1 |

Total, n=242 (66.3); F, n=209 (70.8); M, n=33 (47.8) |

BIA-ACC BioTekna® Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA); Other questionnaires |

Normal; Others, combination of: osteoporosis and/or sarcopenia and/or obesity alone |

-32.4% and 31.3% of F and M were at risk for malnutrition and 5.8% and 6.2% of F and M, respectively were malnourished; -No difference in malnourishment or risk of it in those with or without OSA; -No difference in OSA prevalence or nutritional status in those with or without COVID; -Lower phase angle (indicating lower cell integrity and muscle quality); -Lower total bone mass; -Higher intramuscular adipose tissue |

| Keser, I, 2021 [15] Several nutrients; Body water distribution in nursing home residents | Croatia, Nursing Home |

C-S Inclus/Exclusion criteria applied |

T-score ≤-1 for total bone mass With BIA-ACC |

S-score ≤-1 With BIA- ACC |

BF%: F ≥32; M ≥25 With BIA- ACC |

Total, n=84; F, n=69 (82); M, n=15 (18) |

Mean 83.5 Range 65.3-95.2 |

Total, n=45 (53.6); F, n=37 (53.6); M, n=8 (53.3) |

BIA-ACC BioTekna® 24-h recall; Other questionnaires |

Osteopenic adiposity, adiposity alone | -Lower trend for protein, omega-3, fiber, Ca, Mg, K, vitamins D and K intake; -All participants consumed nutrients below recommendations; -Signif. higher extracellular water, indicating higher inflammation |

| NoPIlich, JZ,* 2019 [21] Weight loss with low fat dairy foods and calcium/ vitamin D supplements effects on bone and body composition | United States, Community dwelling Caucasian, overweight/obese postmeno-pausal women | Inclus/Exclusion Criteria applied; 6-month intervention with 3 randomized groups (dairy, suppl., placebo); All samples blinded for analysis |

T-score ≤-1 for hip and/or spine for osteopenia (no osteoporosis) With iDXA |

Total lean mass (kg); Android lean (kg) Gynoid lean (kg) With iDXA |

BF%: Average at baseline 45.9 With iDXA |

At baseline with complete data, n=135 (dairy, n=64, Ca/vitD suppl., n=62, placebo, n=62); At 6-month, n=97 (dairy, n=32, Ca/vitD suppl., n=37, placebo, n=30); Moderate energy restriction (85% of total energy needs) to all participants Dropout: 28.2%; Imputed analyses for missing data |

Mean 55.8 at base-line; 6.6 years since meno-pause |

Not reported; All three body composition components were measured and evaluated at baseline and after 6 months of intervention |

iDXA; Routine lab equipment and ELISA (for blood and urine samples; 3-day dietary records; Activity records |

Baseline values; Groups after 6 months of intervention |

-All participants lost ~4%, ~3%, and ~2% body weight, fat, and lean mass, respectively; -Dairy group: signif. higher loss in waist, hip, and abdominal circumferences and body fat (total, android); signif. lower loss in lean mass (total, android); -Supplement group: signif. lower decrease in total body, spine, radius BMD; signif. increase in femoral neck and total femur BMD |

|

NoPIlich, JZ,* 2022 [22]; Secondary analysis to Ilich, JZ 2019 [21] Weight loss with low-fat dairy foods and calcium/ vitamin D supplements effects on cardio-metabolic risk |

-All participants improved in (due to weight loss): cardiometabolic indices (BP, TC, triglycerides, insulin, leptin, adiponectin, ApoA1, ApoB) -Dairy group: Signif. decrease in BP, TC, LDL-C, TC/HDL-C, ApoB, leptin; signif. increase in adiponectin, ApoA1 -Supplement group: Signif. decrease in BP, triglycerides, LDL-C, ApoB, leptin; signif. increase in HDL-C, adiponectin, ApoA1 |

||||||||||

|

AChoi, M, 2021 [16] Dietary Calcium and phosphorus intake |

S. Korea, KNHANES 2008-2011 |

C-S Retro- spective Inclus/Exclusion criteria applied |

T-score ≤-1 for hip and/or spine to include osteopenia & osteoporosis With DXA |

SMI F ≤5.4 kg/m2; M ≤7.0 kg/m2 With DXA |

BF%: F ≥32; M ≥25 With DXA BMI: kg/m2 overweight ≥23<25, obese ≥25 |

Total, n=7007; F, n=3864 (55.1); M, n=3143 (44.9) |

Mean, 62.3 OSA-65.5; More women (68.4%) |

Total, n=763 (10.9) F and M combined |

DXA 24-h recall |

Total of 8 groups: Normal and combinations: osteoporosis, and/or sarcopenia and/or obesity alone |

-Lower calcium intake signif. associated with osteosarcopenia and OSA; -Lower phosphorus intake signif. associated with sarcopenic adiposity; - Ca/P ratio (below median) signif. associated with osteopenic adiposity -Signif. lower activity in OSA compared to normal group |

|

AChoi, M, 2020 [17] Protein intake: total and plant-based |

S. Korea, KNHANES 2008-2009 |

C-S Retro- spective Inclus/Exclusion criteria applied |

T-score ≤-1 for hip and/or spine to include osteopenia & osteoporosis With DXA |

ALM/Weight <1SD of Korean reference population (20-39 y old) With DXA |

BF%: F ≥32; M ≥25 With DXA BMI: kg/m2 overweight ≥23<25, obese ≥25 |

Total, n=1351; F, n=706; M, n=645 |

Mean 60.5; F-OSA 65.5 M-OSA 63.8 |

Total, n=865 (64.0); F, n=649 (91.9); M, n=216 (33.4) |

DXA 24-h recall |

Normal, only; No other groups were considered |

-M >65 y consuming <0.91 g/kg of protein (Korean recommend.) had 5.8 higher odds of developing OSO; -Plant-based protein intake in M-OSO was higher than in M-normal. -Energy consumption in M-OSA higher than in M-normal. -Signif. lower intense physical activity in M-OSO |

|

Bae, Y-J, 2020 [18] Fruit intake, vitamin C, potassium |

S. Korea KNHANES 2008- 2010 |

C-S Retro-spective Inclus/Exclusion criteria applied |

T-score ≤-1 for hip and/or spine to include osteopenia & osteoporosis With DXA |

ALM/weight <1SD of reference population |

Waist circumference ≥85 cm | Total, n=1420 F only |

Range 50-64; OSO 58 |

n=194 (13.7) | DXA, 24-h recall |

Normal; osteopenia/ osteoporosi; sarcopenia; and/or obesity | -Signif. lower intake of potassium and vitamin C; - Signif. lower intake of fruits rich in vitamin C and potassium |

|

Ade Franca, NAG, 2020 [19] Dietary intake, muscle strength, sedentary lifestyle |

Brazil; Community dwelling; Health Survey of the City of São Paulo. (ISA-Capital 2015) (2015 ISA-Nutrition) |

C-S Inclus/Exclusion criteria applied |

T-score ≤-1 for hip and/or spine to include osteopenia and osteoporosis With DXA |

ALM/BMI F <0.512 M <0.789 With DXA |

FMI M>9 kg/m2; F>13 kg/m2 with DXA |

Total, n=218; F, n=113 (52); M, n=105 (48); older adults, n=161 (74) |

Mean 63; Range 59–69 |

Total, n=14 (6.4) F and M combined |

DXA 24-h recall; Handgrip with Jamar® dynamometer; Gait speed usual pace, 4 m/min |

Normal + 6 groups: osteopenia/osteoporosis; sarcopenia; obesity; osteopenic sarcopenia; osteopenic obesity; sarcopenic obesity | - Signif. lower protein intake (g/kg/Wt) but not as % of energy; -None of other nutrients were signif. different among groups; - Signif. lower grip strength and more time spent sitting |

|

NoPCervo, MM, 2020 [23] Energy- adjusted Dietary inflammatory index (E-DII) |

Australia: Population-based community dwelling; Southern Tasmania, TASOAC 2002-2004 |

Prospective; with follow-up at 5 and 10 years; Inclus/Exclusion criteria applied |

Changes in T-score ≤-1 for hip and/or spine to include osteopenia & osteoporosis; With DXA |

Changes in ALM whole-body DXA; Hand grip strength; Knee extension; fall risks | Baseline BF%: F ~40 M ~28 With whole-body DXA BMI kg/m2: F ~28 M ~ 27.7 |

Total at baseline, n=1098: F, n=562 (51); M, n=536 (49); At 5 years, n=768; At 10 years, n=566 |

Mean at baseline: 63; Range 51-79 |

Not reported; For every unit increase in E-DII score, Incidence fracture increased 9% in M but decreased 12% in F |

DXA, FFQ to calculate E-DII scores; Dynamometers for changes in grip strength and knee extension; PPA for changes in fall risk; Self -assessment questionnaires for fractures |

With baseline values and changes at five and 10 years of follow-up |

-Consumption of pro-inflammatory diet (higher E-DII scores), increased incidence of fractures over 10 years in M, but not in F, despite being associated with reductions in lumbar spine and total hip BMD in both sexes; -E-DII scores signif. associated with higher fall risk scores and lower ALM in M but not in F. |

|

Park S, 2018 [20] Dietary inflammatory index (DII); Higher scores denote higher proinflamma-tory diet |

S. Korea, KNHANES, 2009-2011 |

C-S Retro- spective Inclus/Exclusion criteria applied |

T-score ≤-1 for hip and/or spine to include osteopenia & osteoporosis; With DXA |

ALM/weight <1SD of reference population; with DXA |

BMI: kg/m2 based on Asian-Pacific guidelines overweight ≥23<25, obese ≥25 | Total, n=1344 F only |

Mean 62.3; OSO 64 |

Total, n=455 (31.8) | DXA, 24-h recall, DII score |

Normal, osteosarco-penia, osteopenic obesity, sarcopenic obesity | -DII scores signif. associated with higher risk for OSO; -Groups with osteosarcopenia, osteopenic obesity, sarcopenic obesity had signif. lower intake of vitamins C and E compared to the normal group |

| Kim J, 2017 [13] Diet Quality-Index-International (DQI-I); higher scores denote better food quality intake | S. Korea KNHANES 2008-2010 |

C-S Retro- spective Inclus/Exclusion criteria applied |

T-score ≤-1 (for Asian reference population) With DXA |

ALM/Weight <1SD of Korean reference population (20-39 y old) With DXA |

BF% ≥40 of body fat by gender With DXA |

Total, n=6129; F, n=3550; M, n=2579 |

F 61.9; M 60.8; OSO F 64.3; OSO M 64.2 |

F 25%; M 13.5% |

DXA, 24-h recall, |

Healthy Korean adults aged 20–39 years |

-In F: Higher scores on the DQI-I associated with better body composition phenotypes; -Signif. less intake of fish, mushrooms, milk, energy, protein -Tendency of less frequent consumption of meat, eggs; -In M: DQI-I scores were not associated with body composition abnormalities. |

| Reference, Studied topic |

Country Setting |

Study Design |

Diagnostic criteria & Instruments Bone Lean/Muscle Adipose |

Sample size n (%) | Age (years) | OSA/OSO Prevalence2 (%) | Assessment Tools |

Compared to3 | Outcomes in OSA/OSO group (or others if indicated) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chung, S-J, 2022 [26] Serum ferritin; Subjects stratified by serum ferritin tertiles | S. Korea, Medical health screening and check-up | C-S Two-center; Inclus/Exclusion criteria applied |

T-score ≤-1 for hip and/or spine to include osteopenia & osteoporosis; With DXA | SMI <1SD of reference population; With BIA |

BF%: F ≥35; M ≥25 With DXA |

Total, n=25,546; F, n=16,912; M, n=8634 |

Mean 58.7; F, 58.3; M, 59.6; F-OSO 66.3; M-OSO 67.7 |

Total, 7.9%; F, 6.4%; M, 9.4% |

DXA; InBody-720; Cobas 8000 (for ferritin), Roche Diagnostics | Normal; combinations: osteoporosis, and/or sarcopenia and/or obesity | -Higher serum ferritin signif. associated with combined adverse body composition in F, but not in M; -F in the highest ferritin tertiles had the highest OSO prevalence |

|

NoPMa, Y, 2020 [27] 25(OHD); Subjects stratified by 25(OH)D tertiles |

China Nine provinces,(commu- nities) |

C-S Inclus/Exclusion criteria applied |

T-score ≤-1 for hip and/or spine to include osteopenia & osteoporosis With DXA |

ALM; <1SD than mean; F 13.9 kg M 20.2 With DXA |

BF%: F 36 M 27.5 With whole-body DXA |

Total, n=4506; F, n=2905 (64.5); M, n=1601 (33.5) |

Mean: 68.1; F, 67.6 M, 68.6 |

Not reported | DXA; Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (for 25(OH)D) |

Osteopenic obesity, Sarcopenic obesity, Obesity-only |

-25(OHD) deficiency associated with greater likelihood of OSO; -Independent negative dose-response associations of 25(OHD) with OSO and other impaired body composition components |

| AKim, YM, 2019 [28] Serum 25(OH)D | S. Korea KNHANES V, 2008-2011 |

Retro- spective; Inclus/Exclusion criteria applied |

T-score ≤-1 for hip and/or spine to include osteopenia & osteoporosis With DXA |

ALM/Weight <1SD of reference population With DXA |

BF%: F ≥35; M ≥ 25 |

Total, n=3267; F, n=2187; M, n=1080 |

Mean 64.2; F 63.8; M 64.6; F-OSO 66.3; M-OSO 67.7 |

Total 36.1%; F, 40.1%; M, 28.1% |

DXA; Radioimmuno assay(DiaSorin) with 1470 Wizard γ-counter |

Osteopenic obesity, Sarcopenic obesity, Obesity-only |

-Both F-OSO and M-OSO had signifi. lower serum 25(OH)D (<20 ng/mL); -Both F and M engaged in the lowest physical activity; -F-OSO had the highest prevalence of hypertension, diabetes and metabolic syndrome |

| Kim, J, 2017 [29] Serum 25(OHD) | S. Korea KNHANES IV, 2008-2010 |

C-S Retro- Spective; Inclus/Exclusion criteria applied |

T-score ≤-1 (for Asian reference population) With DXA |

ALM <1SD of ref. population With DXA |

BF% ≥ 40 of body fat by gender With DXA |

Total, n=5908; F, n=3423; M, n=2485 |

Mean 61.2; F 61.7; M 60.7; F-OSO 64.2; M-OSO 63.9 |

Total, 19.3%; F, 25%; M, 13.5% |

DXA; DiaSorin (for 25(OH)D); 24-h recall |

Osteopenic obesity, Sarcopenic obesity, Obesity -only |

-Signif. higher prevalence of 25(OH)D (<20 ng/mL) in both F and M; -Higher 25(OH)D in mid- and later life signif. associated with reduced odds of adverse body composition, leading to OSA (stronger in M) |

| Reference, Studied topic |

Country Setting |

Study Design |

Diagnostic criteria & Instruments Bone Lean/Muscle Adipose |

Sample size (n) AND Intervention | Age (years) | Prevalence2 n (%) |

Assessment Tools |

Compared to3 | Outcomes in OSA/OSO group (or others if indicated) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lee, Y-H, 2021 [30] Progressive resistance training (peRET) effects on functional performance and body composition |

Taiwan, Community dwelling women |

Inclus/Exclusion Criteria applied; 12-week intervention with 2 randomized groups; Blinded randomization into groups |

T-score ≤-1 for spine to include osteopenia & osteoporosis; With DXA | SMI <5.67 kg/m2; AND grip strength <20 kg; OR gait speed <0.8 m/s | BF%: ≥35 | Total, n=27; peRET, n=15; 40 min, three times/w; OR Control, n=12; No dropouts; >85% exercise compliance; Follow-up at 6 months |

Mean 70.9; No diff. among groups |

All participants, as per inclusion criteria | DXA; BIA Dynamometer, Thera-Band® |

Baseline values; Control group of OSO women (attended group lectures with educational material) |

-Signif. increase in BMD and T-score for spine -Signif. improvement in Functional Forward Reach; Timed up-and-go test; Timed chair-rise test; Gait speed; -No change in BF%, and some lean tissue parameters; -No sustainable benefits after 6 months follow-up |

|

Shen, LI, 2020 [35] Aerobic exercise and resistance training combined effects on body composition |

China, Community dwelling, women and men |

Inclus/Exclusion Criteria applied; 12-week intervention with 2 randomized groups; No mention on assessor blinding |

T-score ≤-1 to include osteopenia & osteoporosis; With DXA | SMI F ≤5.4 kg/m2; M ≤7.0 kg/m2 |

BF%: F ≥35; M ≥25 |

Total, n=30; Exercise, n=15; 45-60 min/day, 3 times/w; OR Control, n=15; |

>60 No diff. between groups |

All participants, as per inclusion criteria | DXA; BIA Dynamometer, Elastic band |

Control group of OSO women and men |

-Signif. increase in BMD and decrease in BF%; - No change in SMI |

|

NoPCunha, PM, 2018 [31] Resistance training volume (1 & 3 sets) effects on bone, muscle and body fat |

Brazil, Community dwelling, women |

Inclus/Exclusion Criteria applied; 12-week intervention with 3 randomized groups; Blinded randomization into groups |

No specific identification for bone, muscle and body fat status. Composite OSO Z-score derived from average of the muscular strength, SMM, % body fat, and BMDcomponents was calculated by formula: (muscularstrength Z-score)+(SMM Z-score)+(−1xbody fat Z-score)+(BMD Z-score)/4 |

Total, n=62; Intervention groups: 1-set training (n=21, for 15 min); OR 3-sets (n=20, for 50 min) 3-times/w; OR Control (n=21); ≥85% exercise compliance |

Mean 67.4; No diff. among groups |

Not reported | DXA; Repetition Maximum (RM) by chest press, knee extension, preacher curl exercise |

Baseline values; Also, 1 set vs. 3 sets of training; Control group |

-Signif, increase in total strength; SMM; -Signif improvement in OSO Composite Z-score from baseline to-post test -Signif, decrease in body fat; -No change in BMD -Dose response to higher activity (3 sets induced higher improvement than 1 set); -Both sets induced higher improvement compared to control |

||

|

Banitalebi, E,* 2020 [34] Elastic band resistance training effects on body composition, functionality, various OSO biomarkers |

Iran, Community dwelling women |

Inclus/Exclusion Criteria applied; 12-week intervention with 2 randomized groups; Concealed randomization (based on age and OSO composite Z-scores) into groups; Blood samples blinded for analysis |

T-score ≤-1 for hip and/or spine to include osteopenia & osteoporosis; With DXA |

10 m walk test ≤ 1 (m/s); SMI ≤ 28% OR ≤ 7.76 kg/m2 |

BF%: ≥32 BMI: >30 kg/m2 |

Total, n=63; Progressive Elastic Band resistance training up to 60 min. (3 times/week), n=32; OR Control, n=31; Intention to treat analysis; 85% exercise compliance; 19% & 29% dropout in exp. and control groups, respectively; 25% participants reported side effects in first 3 sessions Total, n=48; Training, n=26 OR Control, n=22; Intention to treat analysis; 85% exercise compliance |

Range 60-80; Mean 64.1 No difference between groups |

All participants, as per inclusion criteria | DXA; Dynamometer Thera-Band® ELISA for blood tests |

Control group of OSO women |

-Signif. increase in handgrip strength, timed chair-rise test, muscle quality; -Signif. increase in estradiol and decrease in leptin; -Slight improvement in OSO composite Z-score; -No difference in BMD; BF; SMI; gait speed and timed-up-and-go test |

|

Banitalebi, E,* 2021 [32] Elastic band resistance training effects on OSO markers, serum microRNAs |

-Slight but insignificant improvement in OSO serum and other markers; -Serum microRNAs (miR-133 & miR-206) changes correlated with changes in FRAX scores, serum 25(OH)D and alkaline phosphatase |

||||||||||

|

Banitalebi, E,* 2023 [33] Elastic band resistance training effects on cardiometabolic risk factors |

-Signif. decrease in ipid-accumulation product; Triglyceride-glucose-BMI index; Visceral adiposity index; Atherogenic index of plasma; Framingham risk score; -NO change in Triglycerides; Triglyceride-glucose index; triglyceride-glucose-waist circumference index; C-reactive protein; Metabolic syndrome severity score |

||||||||||

|

Hashemi, A,* 2020 [36] Elastic band resistance training effects on vascular aging, serum microRNA-146 |

-Signif. decrease in serum miR-146; total cholesterol, LDL -Signif. increse in HDL; -NO difference in body weight, BMI, BMD, C-reactive protein |

||||||||||

|

Kazemipour, N* 2022 [37] Elastic band resistance training effects on insulin growth factor (IGF-1), fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2) |

-Signif. increase in IGF-1 and FGF-2 NOT significant: Relationship of IGF-1 and FGF-2 with BMD -NO change in BMD |

||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).