Submitted:

28 February 2023

Posted:

28 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

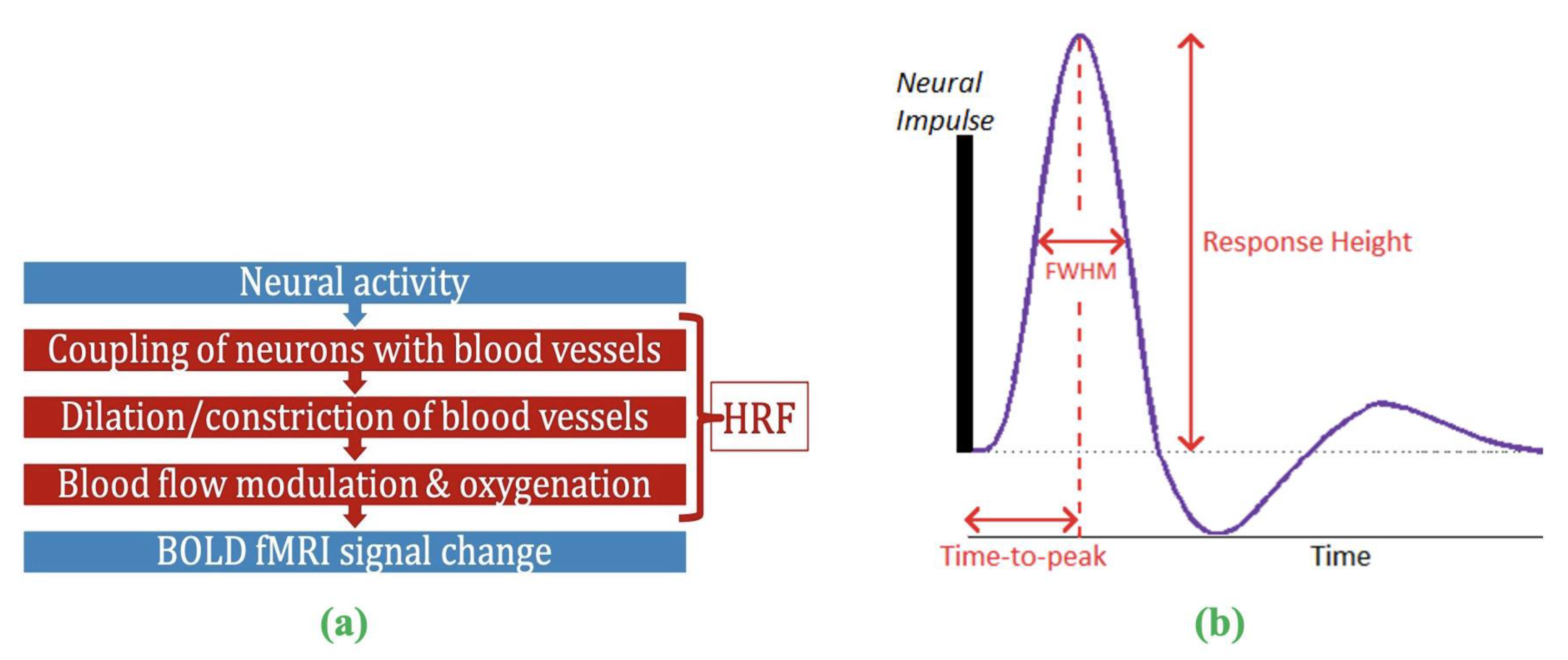

2. The problem of HRF variability

3. HRF estimation from resting-state fMRI data

4. The confound of HRF variability on connectivity estimates

5. The importance of studying HRF variability

6. Clinical research and HRF variability

7. Demographic variables and HRF variability

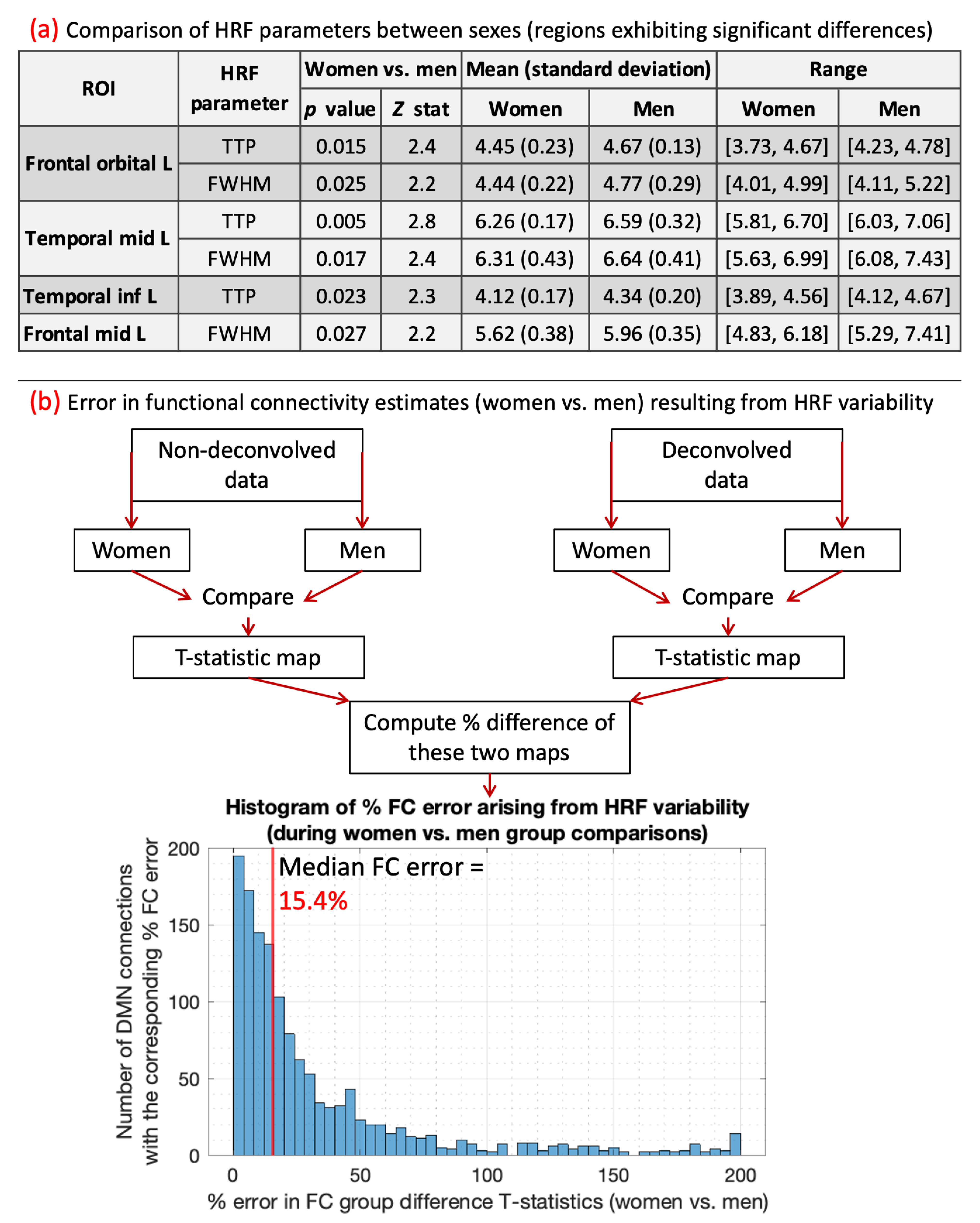

8. Results on HRF differences between sexes and their impact on connectivity

9. The HRF in the spinal cord

10. Discussion and conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Power, J.D.; Cohen, A.L.; Nelson, S.M.; Wig, G.S.; Barnes, K.A.; Church, J.A.; Vogel, A.C.; Laumann, T.O.; Miezin, F.M.; Schlaggar, B.L.; et al. Functional network organization of the human brain. Neuron 2011, 72, 665–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathan, P.J.; Phan, K.L.; Harmer, C.J.; Mehta, M.A.; Bullmore, E.T. Increasing pharmacological knowledge about human neurological and psychiatric disorders through functional neuroimaging and its application in drug discovery. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2014, 14, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosazza, C.; Minati, L. Resting-state brain networks: Literature review and clinical applications. Neurol. Sci. 2011, 32, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logothetis, N.K.; Pauls, J.; Augath, M.; Trinath, T.; Oeltermann, A. Neurophysiological investigation of the basis of the fMRI signal. Nature 2001, 412, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biessmann, F.; Murayama, Y.; Logothetis, N.; Müller, K.; Meinecke, F. Improved decoding of neural activity from fMRI signals using non-separable spatiotemporal deconvolutions. Neuroimage 2012, 61, 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Ress, D. Arterial impulse model for the BOLD response to brief neural activation. Neuroimage 2016, 124, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, J.V.; Pereira, J.M.; Quendera, B.; Raimundo, M.; Moreno, C.; Gomes, L.; Carrilho, F.; Castelo-Branco, M. Early disrupted neurovascular coupling and changed event level hemodynamic response function in type 2 diabetes: An fMRI study. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2015, 35, 1671–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.S.; Liang, Z.; Yao, J.F.; Shen, X.; Frederick, B.D.; Tong, Y. Vascular effects of caffeine found in BOLD fMRI. J. Neurosci. Res. 2019, 97, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handwerker, D.A.; Ollinger, J.M.; M. D'Esposito Variation of BOLD hemodynamic responses across subjects and brain regions and their effects on statistical analyses. Neuroimage 2004, 21, 1639–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, G.K.; Zarahn, E.; D'esposito, M. "The variability of human, BOLD hemodynamic responses. Neuroimage 1998, 8, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxton, R. Introduction to Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Principles and Techniques. Energy 2002, 24, 523. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, J.; Ross, M.; Mendelson, J.; Kaufman, M.; Lange, N.; Maas, L.; Mello, N.; Cohen, B. ; Renshaw, Reduction in BOLD fMRI response to primary visual stimulation following alcohol ingestion. Psychiatry Res. 1998, 82, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noseworthy, M.D.; Alfonsi, J.; Bells, S. Attenuation of brain BOLD response following lipid ingestion. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2003, 20, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Frederick, B.D. Tracking cerebral blood flow in BOLD fMRI using recursively generated regressors. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2014, 35, 5471–5485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernier, M.; Cunnane, S.C.; Whittingstall, K. The morphology of the human cerebrovascular system. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2018, 39, 4962–4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, L.D.; Setsompop, K.; Rosen, B.R.; Polimeni, J.R. Stimulus-dependent hemodynamic response timing across the human subcortical-cortical visual pathway identified through high spatiotemporal resolution 7T fMRI. Neuroimage 2018, 181, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miezin, F.M.; Maccotta, L.; Ollinger, J.M.; Petersen, S.E.; Buckner, R.L. Characterizing the hemodynamic response: Effects of presentation rate, sampling procedure, and the possibility of ordering brain activity based on relative timing. Neuroimage 2000, 11, 735–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Zwart, J.A.; Silva, A.C.; van Gelderen, P.; Kellman, P.; Fukunaga, M.; Chu, R.; Koretsky, A.P.; Frank, J.A.; Duyn, J.H. Temporal dynamics of the BOLD fMRI impulse response. Neuroimage 2005, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badillo, S.; Vincent, T. ; Ciuciu, Group-level impacts of within- and between-subject hemodynamic variability in fMRI. Neuroimage 2013, 82, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliazucchi, E.; Balenzuela, P.; Fraiman, D.; Chialvo, D.R. Criticality in large-scale brain fMRI dynamics unveiled by a novel point process analysis. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, J.D.; Schlaggar, B.L.; Petersen, S.E. Recent progress and outstanding issues in motion correction in resting state fMRI. Neuroimage 2015, 105, 536–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.R.; Liao, W.; Stramaglia, S.; Ding, J.R.; Chen, H.; Marinazzo, D. A blind deconvolution approach to recover effective connectivity brain networks from resting state fMRI data. Med. Image Anal. 2013, 17, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havlicek, M.; Friston, K.J.; Jan, J.; Brazdil, M.; Calhoun, V.D. Dynamic modeling of neuronal responses in fMRI using cubature Kalman filtering. Neuroimage 2011, 56, 2109–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havlicek, M.; Roebroeck, A.; Friston, K.; Gardumi, A.; Ivanov, D.; Uludag, K. Physiologically informed dynamic causal modeling of fMRI data. Neuroimage 2015, 122, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karahanoğlu, F.I.; Caballero-Gaudes, C.; Lazeyras, F.; Van de Ville, D. Total activation: fMRI deconvolution through spatio-temporal regularization. Neuroimage 2013, 73, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, O.; Guillemain, I.; Saillet, S.; Reyt, S.; Deransart, S.; Segebarth, C.; Depaulis, A. Identifying neural drivers with functional MRI: An electrophysiological validation. PLoS Biol. 2008, 23, 2683–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Katwal, S.; Rogers, B.; Gore, J.; Deshpande, G. Experimental Validation of Dynamic Granger Causality for Inferring Stimulus-evoked Sub-100ms Timing Differences from fMRI. IEEE Trans. Neural. Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2017, 25, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feige, B.; Spiegelhalder, K.; Kiemen, A.; Bosch, O.G.; van Elst, L.T.; Hennig, J.; Seifritz, E.; Riemann, D. Distinctive time-lagged resting-state networks revealed by simultaneous EEG-fMRI. Neuroimage 2017, 145, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.N.; Howarth, C.; Kurth-Nelson, Z.; Mishra, A. Interpreting BOLD: Towards a dialogue between cognitive and cellular neuroscience. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B 2016, 371, 20150348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomason, M.E.; Foland, L.C.; Glover, G.H. Calibration of BOLD fMRI using breath holding reduces group variance during a cognitive task. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2007, 28, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, I.M.; Bender, A.; Patihis, L.; Stinson, E.A.; Letang, S.K.; Miller, W.S. The Trouble Interpreting fMRI Studies in Populations with Cerebrovascular Risk: The Use of a Subject-Specific Hemodynamic Response Function in a Study of Age, Vascular Risk, and Memory. bioRxiv 2019, 512343. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.; Thomason, M.E.; Glover, G.H. Mapping and correction of vascular hemodynamic latency in the BOLD signal. Neuroimage 2008, 43, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spano, V.R.; Mandell, D.M.; Poublanc, J.; Sam, K.; Battisti-Charbonney, A.; Pucci, O.; Han, J.S.; Crawley, A.P.; Fisher, J.A.; Mikulis, D.J. CO2 blood oxygen level-dependent MR mapping of cerebrovascular reserve in a clinical population: Safety, tolerability, and technical feasibility. Radiology 2013, 266, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urback, A.L.; MacIntosh, B.J.; Goldstein, B.I. Cerebrovascular reactivity measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging during breath-hold challenge: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 79, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelman, D.R.; Penny, W.D.; Ashburner, J.; Friston, K.J. Modeling regional and psychophysiologic interactions in fMRI: The importance of hemodynamic deconvolution. Neuroimage 2003, 19, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudes, C.C.; Petridou, N.; Francis, S.T.; Dryden, I.L.; Gowland, P.A. Paradigm free mapping with sparse regression automatically detects single-trial functional magnetic resonance imaging blood oxygenation level dependent responses. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2013, 34, 501–518. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudes, C.C.; Petridou, N.; Dryden, I.L.; Bai, L.; Francis, S.T.; Gowland, P.A. Detection and characterization of single-trial fMRI bold responses: Paradigm free mapping. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2011, 32, 1400–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Garcia, L.; Ulfarsson, M.O. Neuronal event detection in fMRI time series using iterative deconvolution techniques. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2011, 29, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, K.; Cisler, J. Decoding neural events from fMRI BOLD signal: A comparison of existing approaches and development of a new algorithm. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2013, 31, 976–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, K.; Cisler, J.; Bian, J.; Hazaroglu, G.; Hazaroglu, O.; Kilts, C. Improving the precision of fMRI BOLD signal deconvolution with implications for connectivity analysis. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2015, 33, 1314–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalidov, I.; Fadili, J.; Lazeyras, F.; Van De Ville, D.; Unser, M. Activelets: Wavelets for sparse representation of hemodynamic responses. Signal Process. 2011, 91, 2810–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, R.; Lina, J.M.; Fahoum, F.; Gotman, J. Detection of epileptic activity in fMRI without recording the EEG. Neuroimage 2012, 60, 1867–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, A.J.; Kim, J.H.; Ress, D. Characterization of the hemodynamic response function across the majority of human cerebral cortex. Neuroimage 2018, 173, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Castillo, J.; Saad, Z.; Handwerker, D.; Inati, S.; Brenowitz, N. ; Bandettini, Whole-brain, time-locked activation with simple tasks revealed using massive averaging and model-free analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 5487–5492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasan, K.R.; Havlicek, M.; Deshpande, G. Non-parametric hemodynamic deconvolution of fMRI using homomorphic filtering. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2015, 34, 1155–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkaoui, H.; Moreau, T.; Halimi, A. ; Ciuciu, Sparsity-based Blind Deconvolution of Neural Activation Signal in FMRI. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Brighton, UK; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, G.; Colenbier, N.; Van Den Bossche, S.; Clauw, K.; Johri, A.; Tandon, M.; Marinazzo, D. rsHRF: A toolbox for resting-state HRF estimation and deconvolution. Neuroimage 2021, 244, 118591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.J.; Harrison, L.; Penny, W. Dynamic causal modelling. Neuroimage 2013, 19, 1273–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.J.; Kahan, J.; Biswal, B.; Razi, A. A DCM for resting state fMRI. Neuroimage 2014, 94, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahanoğlu, F.I.; Van De Ville, D. Transient brain activity disentangles fMRI resting-state dynamics in terms of spatially and temporally overlapping networks. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zöller, D.; Sandini, C.; Schaer, M.; Eliez, S.; Bassett, D.S.; Van De Ville, D. Structural control energy of resting-state functional brain states reveals less cost-effective brain dynamics in psychosis vulnerability. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2021, 42, 2181–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinany, N.; Pirondini, E.; Micera, S.; Van De Ville, D. Dynamic Functional Connectivity of Resting-State Spinal Cord fMRI Reveals Fine-Grained Intrinsic Architecture. Neuron 2020, 108, 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, Z.S.; Gotts, S.J.; Murphy, K.; Chen, G.; Jo, H.J.; Martin, A.; Cox, R.W. Trouble at rest: How correlation patterns and group differences become distorted after global signal regression. Brain Connect. 2012, 2, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, G. Deconvolution of impulse response in event-related BOLD fMRI. Neuroimage 1999, 9, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangaprakash, D.; Wu, G.-R.; Marinazzo, D.; Hu, X.; Deshpande, G. Hemodynamic response function (HRF) variability confounds resting-state fMRI functional connectivity. Magn. Reson. Med. 2018, 80, 1697–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangaprakash, D.; Deshpande, G.; Daniel, T.; Goodman, A.; Robinson, J.; Salibi, N.; Katz, J.; Denney, T.; Dretsch, M. Compromised Hippocampus-Striatum Pathway as a Potential Imaging Biomarker of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2017, 38, 2843–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangaprakash, D.; Dretsch, M.N.; Yan, W.; Katz, J.S.; Denney, T.S.; Deshpande, G. Hemodynamic variability in soldiers with trauma: Implications for functional MRI connectivity studies. NeuroImage Clin. 2017, 16, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boly, M.; Sasai, S.; Gosseries, O.; Oizumi, M.; Casali, A.; Massimini, M.; Tononi, G. Stimulus set meaningfulness and neurophysiological differentiation: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangaprakash, D.; Dretsch, M.N.; Yan, W.; Katz, J.S.; Denney, T.S.; Deshpande, G. Hemodynamic response function parameters obtained from resting-state functional MRI data in soldiers with trauma. Data Brief 2017, 14, 558–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amico, E.; Gomez, F.; Di Perri, C.; Vanhaudenhuyse, A.; Lesenfants, D.; Boveroux, P.; Bonhomme, V.; Brichant, J.F.; Marinazzo, D.; Laureys, S. Posterior cingulate cortex-related co-activation patterns: A resting state FMRI study in propofol-induced loss of consciousness. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamichhane, B.; Adhikari, B.M.; Brosnan, S.F.; Dhamala, M. The neural basis of perceived unfairness in economic exchanges. Brain Connect. 2014, 4, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangaprakash, D.; Dretsch, M.N.; Venkatraman, A.; Katz, J.S.; Denney, T.S.; Deshpande, G. Identifying Disease Foci from Static and Dynamic Effective Connectivity Networks: Illustration in Soldiers with Trauma. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2018, 39, 264–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangaprakash, D.; Tadayonnejad, R.; Deshpande, G. ; J. O'Neill; Feusner, J. FMRI hemodynamic response function (HRF) as a novel marker of brain function: Applications for understanding obsessive-compulsive disorder pathology and treatment response. Brain Imaging Behav. [CrossRef]

- Noble, S.; Scheinost, D.; Constable, R. A decade of test-retest reliability of functional connectivity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroimage 2019, 203, 116157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, J.; Cohen, A.; Nelson, S.; Wig, G.; Barnes, K.; Church, J.; Vogel, A.; Laumann, T.; Miezin, F.; Schlaggar, B.; et al. Functional network organization of the human brain. Neuron 2011, 72, 665–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshpande, G.; Sathian, K.; Hu, X. Effect of hemodynamic variability on Granger causality analysis of fMRI. Neuroimage 2010, 52, 884–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacey, S.; Stilla, R.; Sreenivasan, K.; Deshpande, G.; Sathian, K. Spatial imagery in haptic shape perception. Neuropsychologia 2014, 60, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Deshpande, G.; Liu, C.; Gu, R.; Luo, Y.-J.; Krueger, F. Diffusion of responsibility attenuates altruistic punishment: A functional magnetic resonance imaging effective connectivity study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2015, 37, 663–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampstead, B.M.; Khoshnoodi, M.; Yan, W.; Deshpande, G.; Sathian, K. Patterns of effective connectivity between memory encoding and retrieval differ between patients with mild cognitive impairment and healthy older adults. Neuroimage 2016, 124, 997–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryali, S.; Supekar, K.; Chen, T.; Menon, V. Multivariate dynamical systems models for estimating causal interactions in fMRI. Neuroimage 2011, 54, 807–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryali, S.; Chen, T.; Supekar, K.; Tu, T.; Kochalka, J.; Cai, W.; Menon, V. Multivariate dynamical systems-based estimation of causal brain interactions in fMRI: Group-level validation using benchmark data, neurophysiological models and human connectome project data. J. Neurosci. Methods 2016, 268, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryali, S.; Shih, Y.Y.; Chen, T.; Kochalka, J.; Albaugh, D.; Fang, Z.; Supekar, K.; Lee, J.H.; Menon, V. Combining optogenetic stimulation and fMRI to validate a multivariate dynamical systems model for estimating causal brain interactions. Neuroimage 2016, 132, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handwerker, D.A.; Gonzalez-Castillo, J.; M. D'Esposito; Bandettini, P.A. The continuing challenge of understanding and modeling hemodynamic variation in fMRI. Neuroimage 2012, 62, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlicek, M.; Jan, J.; Brazdil, M.; Calhoun, V. Dynamic Granger causality based on Kalman filter for evaluation of functional network connectivity in fMRI data. Neuroimage 2010, 53, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; David, O.; Hu, X.; Deshpande, G. Can Patel's τ accurately estimate directionality of connections in brain networks from fMRI? Magn. Reson. Med. 2017, 78, 2003–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, S.; Polimeni, J.R.; Wang, D.J.; Yan, L.; Chen, J.J. Associations of resting-state fMRI functional connectivity with flow-BOLD coupling and regional vasculature. Brain Connect. 2015, 5, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, M.G.; Whittaker, J.R.; Driver, I.D.; Murphy, K. Vascular physiology drives functional brain networks. Neuroimage 2020, 217, 116907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Rangaprakash, D.; Deshpande, G. Aberrant hemodynamic responses in Autism: Implications for resting state fMRI functional connectivity studies. NeuroImage Clin. 2018, 19, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Rangaprakash, D.; Deshpande, G. Hemodynamic response function parameters obtained from resting state BOLD fMRI data in subjects with Autism Spectrum Disorder and matched healthy controls. Data Brief 2017, 14, 558–562. [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande, G.; Rangaprakash, D.; Yan, W.; Liddle, P.; Palaniyappan, L. Characterization of Hemodynamic Alterations in Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder and their Effect on Resting-state Functional Connectivity. In Proceedings of the Schizophrenia International Research Society Conference (SIRS), Florence, Italy, April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Archila-Meléndez, M.E.; Sorg, C.; Preibisch, C. Modeling the impact of neurovascular coupling impairments on BOLD-based functional connectivity at rest. Neuroimage 2020, 218, 116871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.L.; Chen, C.M.; Huang, C.Y.; Shih, C.T.; Huang, C.W.; Chiu, S.C.; Shen, W.C. Effects of Hemodynamic Response Function Selection on Rat fMRI Statistical Analyses. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, K.A.; Fisher, Z.F.; Arizmendi, C.A.M.P.; Hopfinger, J.; Cohen, J.R.; Beltz, A.M.; Lindquist, M.A.; Hallquist, M.N.; Gates, K.M. Detecting Task-Dependent Functional Connectivity in Group Iterative Multiple Model Estimation with Person-Specific Hemodynamic Response Functions. Brain Connect. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, R.L.; Vannesjo, S.J.; By, S.; Gore, J.C.; Smith, S.A. Spinal cord MRI at 7T. Neuroimage 2018, 168, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, H.; Law, C.; Weber, K.A.; Mackey, S.C.; Glover, G.H. Dynamic per slice shimming for simultaneous brain and spinal cord fMRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 2019, 81, 825–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barth, M.; Breuer, F.; Koopmans, P.; Norris, D.; Poser, B. Simultaneous multislice (SMS) imaging techniques. Magn. Reson. Med. 2016, 75, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, G.H.; Li, T.Q.; Ress, D. Image-based method for retrospective correction of physiological motion effects in fMRI: RETROICOR. Magn. Reson. Med. 2000, 44, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorgolewski, K.J.; Poldrack, R.A. A Practical Guide for Improving Transparency and Reproducibility in Neuroimaging Research. PLoS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poldrack, R.A.; Baker, C.I.; Durnez, J.; Gorgolewski, K.J.; Matthews, P.M.; Munafò, M.R.; Nichols, T.E.; Poline, J.B.; Vul, E.; Yarkoni, T. Scanning the horizon: Towards transparent and reproducible neuroimaging research. Nature reviews. Neuroscience 2017, 18, 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Osmanlıoğlu, Y.; Alappatt, J.A.; Parker, D.; Verma, R. Analysis of Consistency in Structural and Functional Connectivity of Human Brain. in Proceedings. IEEE Int. Symp. Biomed. Imaging 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrom, A.D. Regional variation in neurovascular coupling and why we still lack a Rosetta Stone. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2021, 376, 20190634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Murphy, K.; Drew, P.J. Rude mechanicals in brain haemodynamics: Non-neural actors that influence blood flow. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2021, 376, 20190635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Hall, C.N.; Howarth, C.; Freeman, R.D. Key relationships between non-invasive functional neuroimaging and the underlying neuronal activity. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2021, 376, 20190622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, K.L.; Zuppichini, M.D.; Turner, M.P.; Sivakolundu, D.K.; Zhao, Y.; Abdelkarim, D.; Spence, J.S.; Rypma, B. BOLD hemodynamic response function changes significantly with healthy aging. Neuroimage 2019, 188, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Z.Y.; Vinkhuyzen, A.; Thompson, P.M.; McMahon, K.L.; Blokland, G.; de Zubicaray, G.I.; Calhoun, V.; Martin, N.G.; Visscher, P.M.; Wright, M.J.; et al. Genes influence the amplitude and timing of brain hemodynamic responses. Neuroimage 2016, 124, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.E.; Diaz-Santos, M.; Frei, S.; Dang, B.H.; Kaur, P.; Lyden, P.; Buxton, R.; Douglas, P.K.; Bilder, R.M.; Esfandiari, M.; et al. Hemodynamic latency is associated with reduced intelligence across the lifespan: An fMRI DCM study of aging, cerebrovascular integrity, and cognitive ability. Brain Struct. Funct. 2020, 225, 1705–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbau, I.G.; Brücklmeier, B.; Uhr, M.; Arloth, J.; Czamara, D.; Spoormaker, V.I.; Czisch, M.; Stephan, K.E.; Binder, E.B.; Sämann, P.G. The brain's hemodynamic response function rapidly changes under acute psychosocial stress in association with genetic and endocrine stress response markers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E10206–E10215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, A.R.; Toulouse, T.; Klimaj, S.; Ling, J.M.; Pena, A.; Bellgowan, P.S. Investigating the properties of the hemodynamic response function after mild traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2014, 31, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetanov, K.A.; Henson, R.; Rowe, J.B. Separating vascular and neuronal effects of age on fMRI BOLD signals. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2021, 376, 20190631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabluchanskiy, A.; Nyul-Toth, A.; Csiszar, A.; Gulej, R.; Saunders, D.; Towner, R.; Turner, M.; Zhao, Y.; Abdelkari, D.; Rypma, B.; et al. Age-related alterations in the cerebrovasculature affect neurovascular coupling and BOLD fMRI responses: Insights from animal models of aging. Psychophysiology 2020, e13718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, B.D.; Groth, C.L.S.E.; Sillau, S.H.; Sutton, B.; Legget, K.T.; Tregellas, J.R. Hemodynamic responses are abnormal in isolated cervical dystonia. J. Neurosci. Res. 2020, 98, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.R.; Di Perri, C.; Charland-Verville, V.; Martial, C.; Carrière, M.; Vanhaudenhuyse, A.; Laureys, S.; Marinazzo, D. Modulation of the spontaneous hemodynamic response function across levels of consciousness. Neuroimage 2019, 200, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemma, M.; de Vitis, A.; Baldoli, C.; Calvi, M.R.; Blasi, V.; Scola, E.; Nobile, L.; Iadanza, A.; Scotti, G.; Beretta, L. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in children sedated with propofol or midazolam. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 2009, 21, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibaraki, M.; Shinohara, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Miura, S.; Kinoshita, F.; Kinoshita, T. Interindividual variations of cerebral blood flow, oxygen delivery, and metabolism in relation to hemoglobin concentration measured by positron emission tomography in humans. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2010, 30, 1296–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aanerud, J.; Borghammer, P.; Rodell, A.; Jónsdottir, K.Y.; Gjedde, A. Sex differences of human cortical blood flow and energy metabolism. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2017, 37, 2433–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golestani, A.M.; Wei, L.L.; Chen, J.J. Quantitative mapping of cerebrovascular reactivity using resting-state BOLD fMRI: Validation in healthy adults. Neuroimage 2016, 138, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boese, A.C.; Kim, S.C.; Yin, K.J.; Lee, J.P.; Hamblin, M.H. Sex differences in vascular physiology and pathophysiology: Estrogen and androgen signaling in health and disease. American journal of physiology. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2017, 313, H524–H545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huxley, V.H.; Kemp, S.S. Sex-Specific Characteristics of the Microcirculation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1065, 307–328. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, J.N. Sex-specific factors regulating pressure and flow. Exp. Physiol. 2017, 102, 1385–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangaprakash, D.; Wu, G.-R.; Marinazzo, D.; Hu, X.; Deshpande, G. Parameterized hemodynamic response function data of healthy individuals obtained from resting-state functional MRI in a 7T MRI scanner. Data Brief 2018, 17, 1175–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia, A.F.; Nebel, M.B.; Barber, A.D.; Choe, A.S.; Pekar, J.J.; Caffo, B.S.; Lindquist, M.A. Improved estimation of subject-level functional connectivity using full and partial correlation with empirical Bayes shrinkage. Neuroimage 2018, 172, 478–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, B.N.; Barry, R.L.; Rogers, B.P.; Maki, S.; Mishra, A.; Thukral, S.; Sriram, S.; Bhatia, A.; Pawate, S.; Gore, J.C.; et al. Multiple sclerosis lesions affect intrinsic functional connectivity of the spinal cord. Brain 2018, 141, 1650–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckziegel, D.; Vachon-Presseau, E.; Petre, B.; Schnitzer, T.; Baliki, M.; Apkarian, A. Deconstructing biomarkers for chronic pain: Context- and hypothesis-dependent biomarker types in relation to chronic pain. Pain 2019, 160, S37–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Albuquerque, M.; Branco, L.M.; Rezende, T.J.; de Andrade, H.M.; Nucci, A.; França, M.C. Longitudinal evaluation of cerebral and spinal cord damage in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Neuroimage Clin. 2017, 14, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciaguerra, L.; Meani, A.; Mesaros, S.; et al. Brain and cord imaging features in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Ann. Neurol. 2019, 85, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, J.; Schaprian, T.; Berkan, K.; Reetz, K.; França, M.C.; de Rezende, T.; Hong, J.; Liao, W.; van de Warrenburg, B.; et al. Regional Brain and Spinal Cord Volume Loss in Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 3. Mov. Disord. 2021, in press. [CrossRef]

- Freund, P.; Seif, M.; Weiskopf, N.; et al. MRI in traumatic spinal cord injury: From clinical assessment to neuroimaging biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 1123–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzi, R.M.; Palesi, F.; Castellazzi, G.; Vitali, P.; Anzalone, N.; Bernini, S.; Ramusino, M.C.; Sinforiani, E.; Micieli, G.; Costa, A.; et al. Unsuspected Involvement of Spinal Cord in Alzheimer Disease. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevarrow, M.P.; Baker, S.E.; Wilson, T.W.; Kurz, M.J. Microstructural changes in the spinal cord of adults with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2021, in press. [CrossRef]

- Preti, M.; Bolton, T.; Van De Ville, D. The dynamic functional connectome: State-of-the-art and perspectives. Neuroimage 2016, 160, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jollans, L.; Boyle, R.; Artiges, E.; Banaschewski, T.; Desrivières, S.; Grigis, A.; Martinot, J.L.; Paus, T.; Smolka, M.N.; Walter, H.; et al. Quantifying performance of machine learning methods for neuroimaging data. Neuroimage 2019, 199, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, E.S.; Huber, L.; Bandettini, P.A. Higher and deeper: Bringing layer fMRI to association cortex. Prog. Neurobiol. 2020, 101930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, E.S.; Shen, X.; Scheinost, D.; Rosenberg, M.D.; Huang, J.; Chun, M.M.; Papademetris, X.; Constable, R.T. Functional connectome fingerprinting: Identifying individuals using patterns of brain connectivity. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 1664–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preibisch, C.; Castrillón, J.; Bührer, M.; Riedl, V. Evaluation of Multiband EPI Acquisitions for Resting State fMRI. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).