1. Introduction

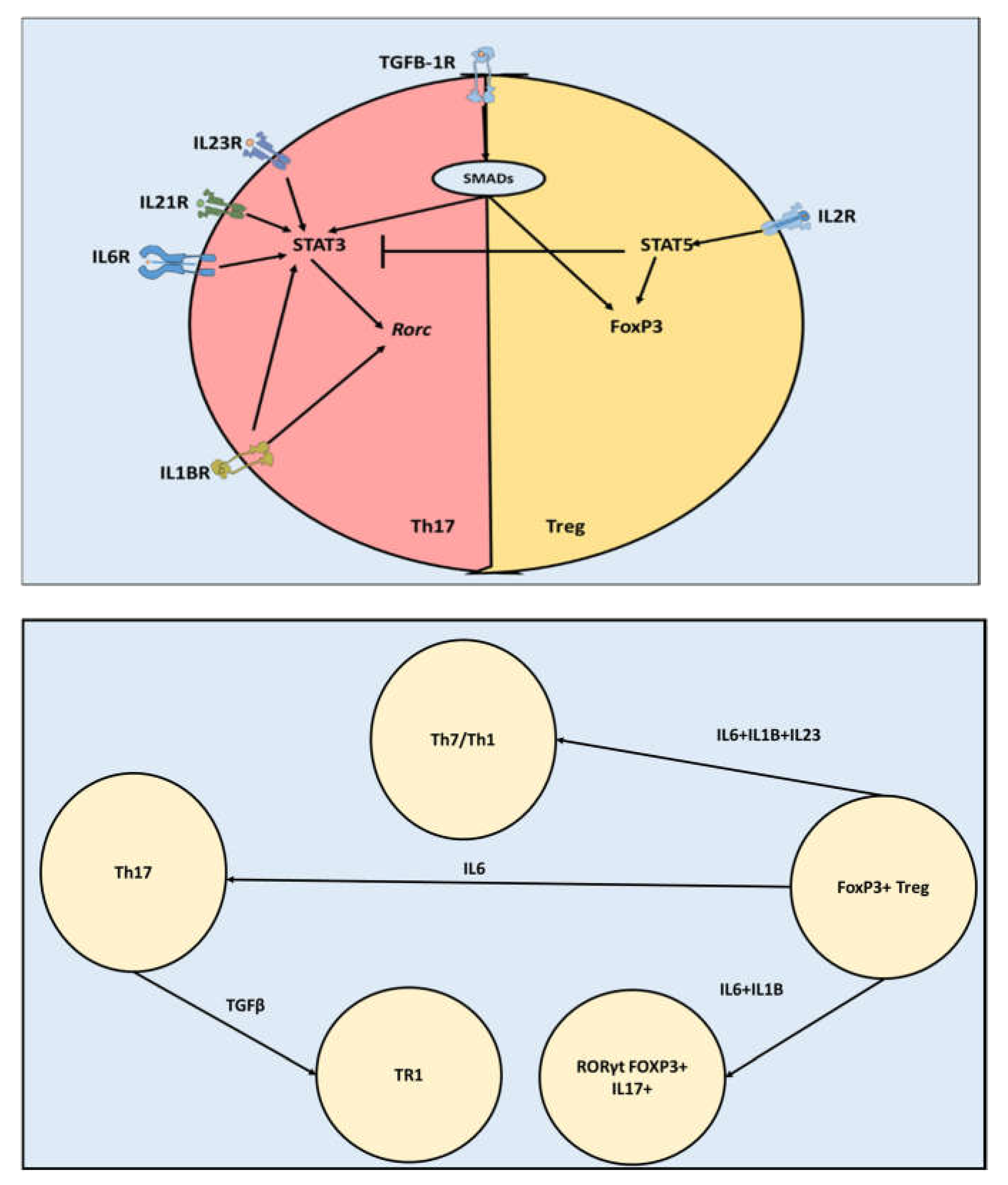

Although Th17 and Tregs perform opposite functions, they have comparable transcriptomic profiles. Both Th17 and Tregs belong to the CD4+ T cells family of cells (1). This family shares the ability of differentiation and activation under the influence of antigen recognition and co-stimulation, and environmental cytokines (2). In addition to Th17 and Tregs, the CD4+ T cells family also include other cells such as Th1, Th2, Th9, and Th22 (3). Various members of CD4+ T cells such as Th17 and Th1 can be pathogenic (1)(4). In several neuropathological conditions such as multiple sclerosis and depression, CD4+ Th17 cells have been shown to accumulate in the brain and play a role in exacerbating demyelination and lesion formation (5)(2). This function is played through the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL17A, IL17F, TNFα, IL6 (6). Tregs, on the other side, have a regulatory function. Tregs are capable of inhibiting Th17 and Th1 pathogenic function through various pathways, including the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL10 and IL4 (7). The master transcription factor controlling Th17 function is RORγt (

Rorc), while Treg is controlled by FoxP3 (4). Th17 can differentiate under several combinations of cytokines present in its microenvironment such as (TGFB3,IL23), (TGFB1,IL6,IL23), (TGFB3,IL6),(TGFB1,IL6), (IL1B,IL6,IL23) and (IL1B,IL6) (4,8,9). Most of these pathways involve TGFβ and SMAD interaction to cause phosphorylation of STAT3 which in turn activates

Rorc. Interestingly, Th17 and Tregs share the SMAD- TGFβ pathway (

Figure 1) (10). Where, in the case of Tregs, TGFβ through a SMAD-mediated pathway causes activation of FoxP3. (11). Furthermore, Th17 and Treg axis is highly reprogrammable. FoxP3+ Tregs could be reprogrammed into Th17 under the influence of IL6. Under the influence of IL6, IL123, and IL1B, Tregs could be converted into pathogenic Th17. Tregs could also be reprogramed into RORγt+ FOXP3+ IL17+ cells known as Tr17. Furthermore, Th17 could be reprogrammed toward anti-inflammatory Treg-like cells (Tr1), which can reduce inflammation in the CNS(12). Moreover, intermediate stable cell types exist such as RORγt+ FoxP3+ IL17- exists (13). Taken together, current knowledge indicates that Th17 and Tregs are highly related although they have different functions and different phenotypes.

The reasons behind the differences in the abilities of Th17 and Treg cells to infiltrate the BBB are not fully understood. Th17 infiltration of the brain in neurodegenerative diseases and psychological diseases is higher than that of Tregs (2)(14)(15). Treg isolated from healthy individuals or homeostatic mouse models present higher migration abilities to non CD4+ T cells. However, this transmigratory ability is diminished in neuropathological conditions such as multiple sclerosis (15). Our own investigation shows a clear difference between Th17 and Tregs migration from the periphery to the brain across the blood brain barrier in a model of depression caused by gut inflammation(16). Thus it seems unlikely that the difference in numbers is caused by, polarization of Tregs is reversed towards Th17 within the CNS at least in our model.

However, the reasons behind this observation are not yet known. In the next section/we discuss four mechanisms that could be contributing to this difference.

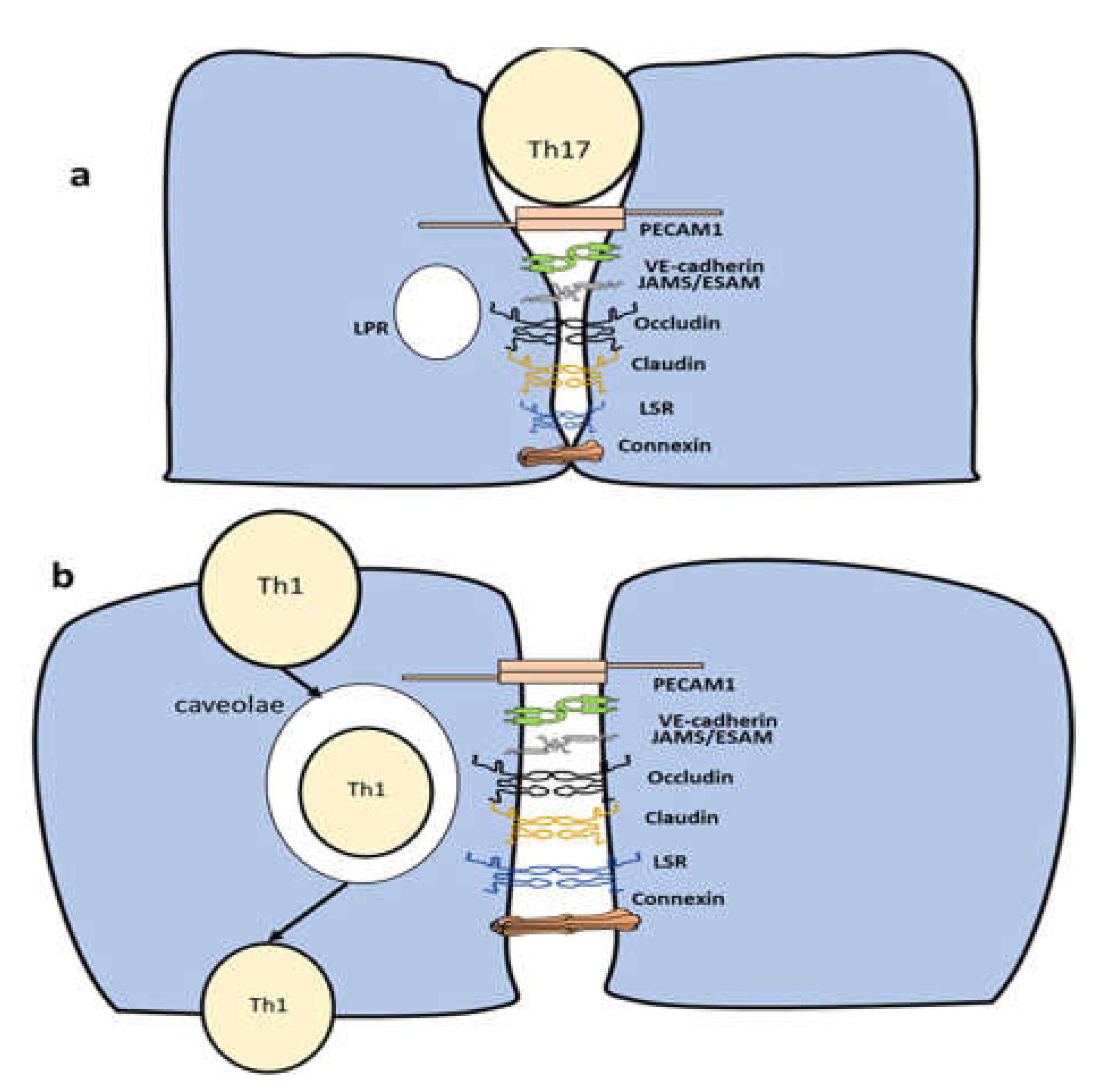

2. Difference in the diapedesis route

There is large difference between diapedesis under homeostasis compared to pathological conditions. During homeostasis the brain is almost isolated with very limited number of CD4+ T cells gaining access to the brain. During pathological conditions, CD4+ T cells infiltrate the brain through four stages (8)(17). In the first stage, CD4+ T cells are captured from the bloodstream through the interaction between VCAM1 expressed on the endothelial cells and a4b1 expressed on CD4+T cells (17). In the second stage, the process of infiltration is activated through the interaction between CCR7 expressed on T cells and CCL21 produced by the endothelial cells of the BBB (8). In the third stage, adhesion of CD4+ T cells to the BBB is initiated through the interaction between LFA1 expressed on CD4+ T cells and ICAM1. In the final stage, diapedesis starts with one of two pathways (i) paracellular transmigration (ii) transcellular transmigration. The clustering of ICAM1-VCAM1 with their respective ligands could take the form of transmigratory cups. Transmigratory cups surround the lower area of the lymphocytes in both paracellular and transcellular migration (17). However, their role is still controversial, and it is not known whether they affect the Th17/ Treg axis. Additionally, ICAM1/VCAM1 interaction with their respective ligands leads to a rise in calcium. Free calcium activates myosin light-chain kinase and initiates actin-myosin contraction (18). ICAM1 also activates the RhoA pathway, which activates MLCK and hence actin contraction. Disassembling the adherens junctions starts with the phosphorylation of VE-Cadherin by Src and PyK2 through an ICAM1-mediated pathway. This process leads to unbinding β-catenin to VE-cadherin. Additionally, RAC1 is activated through a VCAM1 pathway leading to VE-cadherin phsopherylation (19). Several components known to play a role in increasing BBB adhesion (e.g., CD99 and JAM-A but not VE-cadherin) are transferred to a vesicle-like structure called Lateral Border Recycling Compartment. Following that, PECAM1 facilities, the motion of CD4+ T cells (20). Conversely, in transcellular migration, CAV1, CAV2, and caveolin interact together to form an area that allows the CD4+ T cells to pass through the cell membrane (21). It has been shown that autoreactive Th17 cells produce IL-17 and IL-22, which disrupt tight junction proteins in the central nervous system (CNS) endothelial cells in multiple sclerosis (22). Interestingly, Th17 has been shown to infiltrate endothelial cells through a paracellular pathway (

Figure 2) (20). Tregs have been demonstrated to prefer the transcellular route, in analogous systems such as human hepatic sinusoidal endothelium (

Figure 2) (23). However, if Tregs follow a transcellular route to infiltrate the BBB is not yet known. Also, it is important to note that when PECAM1 was knocked out, Th17 followed a transcellular pathway (20). Whether PECAM1expression can influence Treg diapedesis is not yet known. Taken together, current reports suggest that there could be a difference in the favored migration route between Th17 and Tregs.

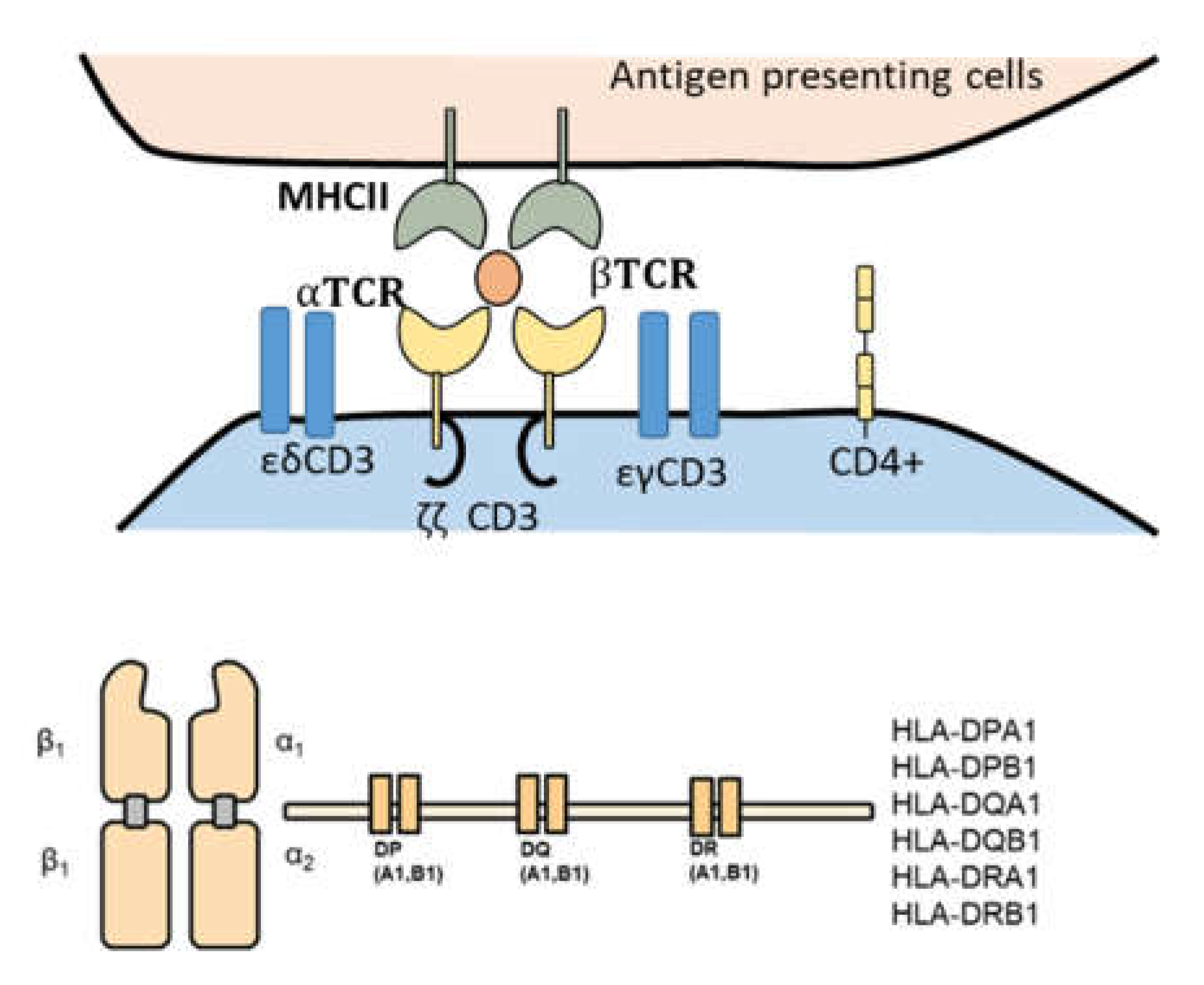

3. Difference in TCR repertoire components.

Methodically investigating T-cell receptor (TCR) repertoires of Th17 and Treg cells could shed light on the factors leading to Th17 infiltrative abilities as opposed to Tregs. TCR-CD3 complex is the main component responsible for antigen recognition on CD4+ T cells (24). The complex is built of two variable chains (e.g., α and β) forming the TCR domain connected with three CD3 transduction molecules (e.g., CD3δ/ε, CD3γ/ε, and CD3ζ/ζ). The variable regions in α and β chains are controlled by the expression of CDR3. MHCII is expressed by endothelial cells of the brain (25). This complex is composed of an α and a β chain (

Figure 3), which are built by the DP, DQ, and DR genes collaboratively. The differences in the sequences of CDR3 (TCR complex) and the genes DP, DQ, and DR (MHCII) between Th17 and Tregs could be one of the leading factors supporting Th17 infiltrative capacity of the brain. In rheumatoid arthritis, where an unbalance between Th17 and Treg has been shown to influence the disease outcome, it has been revealed that the diversity of the Th17 was less in RA than in healthy controls (26). Conversely, the case was reversed among Tregs repertoire, indicating higher clonality among Th17 but not within Tregs. In the context of multiple sclerosis, the TCR repertoire has been recently investigated. A high correlation between TCR repertoire and viruses antigen was reported (27). However, the difference between Th17 and Treg repertoire was not yet investigated. Innovative techniques such as Single-cell RNA-sequencing could shed more light on this intriguing question (5).

4. Difference in Chemokine receptors expression

Data have shown that CD4+ T cells migrating to the brain utilize CCR6 and CCR7 chemokine receptors to seek their ligands produced by endothelial cells (e.g., CCL21 and CCL20)(8)(28). However, the differences in the chemokines receptors expression between Th7 and Tregs have not been yet investigated. It has been shown that CCR9 drives the differentiation and migration of Th17. Conversely, CCR9 has been shown to inhibit Treg function (29)(30). CCR9 was shown to be expressed in the hippocampus, particularly on neurons and astrocytes (31). However, endothelial cells expression of CCR9, has not been evaluated. Furthermore, its role in the context of regulating Th17 and Treg infiltration of the brain is yet to be found.

5. Difference in physical structure

The difference in the physical structure between Th17 and Tregs could be contributing to the difference in their brain-infiltration capacity. Cells investigate their microenvironment and direct their movement based on the lowest possible strain energy needed (32)(33). CD4+ T cells determine their lowest strain energy state using their filopodia and lamellipodia. In an interesting study (34), , the authors compared the motility of Th17 and Th1 in multiple sclerosis using a two-photon laser microscope, in the subarachnoid space of the spinal cords of mice treated with the myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein peptide. Interestingly, Th1 cells were shown to move in a straight line, while Th17 presented limited motility (34). Intriguingly, when the authors blocked LFA1 integrin, the dynamics of both Th1 and Th17 cells were affected. However, only the deformability and biomechanics of Th1 were changed, manifested by alterations in the filopodia and lamellipodia of Th1, but not Th17 (34). These results point toward a role for LFA1 in Th1 cell deformation and cytoskeletal rearrangements as opposed to Th17. Intriguingly, these findings raise unanswered questions about the genes controlling Th17 motility in comparison to Tregs and whether physical structure contributes to increasing the frequency of Th17 infiltration of the brain in multiple sclerosis.

6. Conclusion

Th17 and Treg cells infiltration of the BBB constitute an unsolved riddle. First, these two cell types share important developmental pathways. They are also reprogrammable into various intermediate stable cells along the Th17/ Treg axis. However, various differences seem to control their ability to infiltrate the brain. These differences include but are not limited to; their favored diapedesis mechanism, their expression of chemokine receptors, their TCR repertoire, and their biomechanical properties. Investigating these differences is critical in designing therapeutics that aim to inhibit Th17 proinflammatory effects while enhancing Treg anti-inflammatory function.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the fruitful discussions and guidance of Prof. Macrious Abraham and Prof. Mariam Joachim.

References

- Basu R, Hatton RD, Weaver CT. The Th17 family: Flexibility follows function. Immunol Rev. 2013; [CrossRef]

- Beurel E, Lowell JA. Th17 cells in depression. Brain Behav Immun. 2018 Mar;69:28-34. [CrossRef]

- Basu R, O'Quinn DB, Silberger DJ, Schoeb TR, Fouser L, Ouyang W, et al. Th22 Cells Are an Important Source of IL-22 for Host Protection against Enteropathogenic Bacteria. Immunity. 2012 Dec;37(6):1061-75. [CrossRef]

- Mickael M-E, Basu R, Bhaumik S. Retinoid-related orphan receptor RORγt in CD4+T cell mediated intestinal homeostasis and inflammation. Am J Pathol. 2020;02(1). [CrossRef]

- Kubick N, Henckell Flournoy PC, Klimovich P, Manda G, Mickael M-E. What has single-cell RNA sequencing revealed about microglial neuroimmunology? Immunity, Inflamm Dis. 2020; [CrossRef]

- Moser T, Akgün K, Proschmann U, Sellner J, Ziemssen T. The role of TH17 cells in multiple sclerosis: Therapeutic implications. Autoimmunity Reviews. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Crome SQ, Clive B, Wang AY, Kang CY, Chow V, Yu J, et al. Inflammatory Effects of Ex Vivo Human Th17 Cells Are Suppressed by Regulatory T Cells. J Immunol. 2010 Sep 15;185(6):3199-208. [CrossRef]

- Kubick N, Flournoy PCH, Enciu A-M, Manda G, Mickael M-E. Drugs Modulating CD4+ T Cells Blood-Brain Barrier Interaction in Alzheimer's Disease. Pharmaceutics. 2020 Sep 16;12(9):880. [CrossRef]

- Bhaumik S, Basu R. Cellular and molecular dynamics of Th17 differentiation and its developmental plasticity in the intestinal immune response. Frontiers in Immunology. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S. The role of transforming growth factor β in T helper 17 differentiation [Internet]. Vol. 155, Immunology. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2018 [cited 2021 Jan 28]. p. 24-35. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6099164/?report=abstract . [CrossRef]

- Muranski P, Restifo NP. Essentials of Th17 cell commitment and plasticity. Vol. 121, Blood. American Society of Hematology; 2013. p. 2402-14. [CrossRef]

- Jankovic D, Kugler DG, Sher A. IL-10 production by CD4+ effector T cells: a mechanism for self-regulation. Mucosal Immunol. 2010 May 3;3(3):239-46. [CrossRef]

- Kim BS, Lu H, Ichiyama K, Chen X, Zhang YB, Mistry NA, et al. Generation of RORγt + Antigen-Specific T Regulatory 17 Cells from Foxp3 + Precursors in Autoimmunity. Cell Rep. 2017 Oct 3;21(1):195-207. [CrossRef]

- Passos GR Dos, Sato DK, Becker J, Fujihara K. Th17 Cells Pathways in Multiple Sclerosis and Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorders: Pathophysiological and Therapeutic Implications. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:1-11. [CrossRef]

- Schneider-Hohendorf T, Stenner MP, Weidenfeller C, Zozulya AL, Simon OJ, Schwab N, et al. Regulatory T cells exhibit enhanced migratory characteristics, a feature impaired in patients with multiple sclerosis. Eur J Immunol. 2010; [CrossRef]

- Mickael ME, Bhaumik S, Chakraborti A, Umfress A, Groen T van, Macaluso M, et al. RORγt-Expressing Pathogenic CD4+T Cells Cause Brain Inflammation During Chronic Colitis. bioRxiv [Internet]. 2021 Sep 3 [cited 2021 Sep 9];2021.09.01.458634. Available from: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.09.01.458634v1 . [CrossRef]

- Muller WA. Mechanisms of leukocyte transendothelial migration. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis. 2011; [CrossRef]

- Winger RC, Koblinski JE, Kanda T, Ransohoff RM, Muller WA. Rapid Remodeling of Tight Junctions during Paracellular Diapedesis in a Human Model of the Blood-Brain Barrier. J Immunol [Internet]. 2014 Sep 1 [cited 2019 Feb 6];193(5):2427-37. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25063869 . [CrossRef]

- Muller WA. Transendothelial migration: unifying principles from the endothelial perspective. Immunol Rev. 2016 Sep;273(1):61-75. [CrossRef]

- Wimmer I, Tietz S, Nishihara H, Deutsch U, Sallusto F, Gosselet F, et al. PECAM-1 Stabilizes Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity and Favors Paracellular T-Cell Diapedesis Across the Blood-Brain Barrier During Neuroinflammation. Front Immunol. 2019 Apr 5;10. [CrossRef]

- Kubick N, Klimovich P, Henckel P, Mickael M-E. Para-cellular and transcellular diapedesis are divergent but inter-connected evolutionary events. bioRxiv [Internet]. 2020 Sep 22 [cited 2021 Jan 30];2020.09.21.307066. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Jadidi-Niaragh F, Mirshafiey A. Th17 Cell, the New Player of Neuroinflammatory Process in Multiple Sclerosis. Scand J Immunol. 2011 Jul;74(1):1-13. [CrossRef]

- Shetty S, Weston CJ, Oo YH, Westerlund N, Stamataki Z, Youster J, et al. Common Lymphatic Endothelial and Vascular Endothelial Receptor-1 Mediates the Transmigration of Regulatory T Cells across Human Hepatic Sinusoidal Endothelium. J Immunol. 2011 Apr 1;186(7):4147-55. [CrossRef]

- Abul K. Abbas, Andrew H. Lichtman SP. Cellular & Molecular Immunology, 7th Edit. ELSEVIER. 2011.

- Lopes Pinheiro MA, Kamermans A, Garcia-Vallejo JJ, van het Hof B, Wierts L, O'Toole T, et al. Internalization and presentation of myelin antigens by the brain endothelium guides antigen-specific T cell migration. Elife. 2016 Jun 23;5. [CrossRef]

- Jiang X, Wang S yu, Zhou C, Wu J hua, Jiao Y hao, Lin L ya, et al. TCR repertoire analysis reveals effector memory T cells differentiation into Th17 cells in rheumatoid arthritis. bioRxiv. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Amoriello R, Greiff V, Aldinucci A, Bonechi E, Carnasciali A, Peruzzi B, et al. The TCR Repertoire Reconstitution in Multiple Sclerosis: Comparing One-Shot and Continuous Immunosuppressive Therapies. Front Immunol. 2020; [CrossRef]

- Li Q, Laumonnier Y, Syrovets T, Simmet T. Recruitment of CCR6-expressing Th17 cells by CCL20 secreted from plasmin-stimulated macrophages. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 2013 Jul;45(7):593-600. [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Kang SG, HogenEsch H, Love PE, Kim CH. Retinoic Acid Determines the Precise Tissue Tropism of Inflammatory Th17 Cells in the Intestine. J Immunol. 2010 May 15;184(10):5519-26. [CrossRef]

- Evans-Marin HL, Cao AT, Yao S, Chen F, He C, Liu H, et al. Unexpected Regulatory Role of CCR9 in Regulatory T Cell Development. Sun J, editor. PLoS One. 2015 Jul 31;10(7):e0134100. [CrossRef]

- Liu JX, Cao X, Tang YC, Liu Y, Tang FR. CCR7, CCR8, CCR9 and CCR10 in the mouse hippocampal CA1 area and the dentate gyrus during and after pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus. J Neurochem. 2007; [CrossRef]

- Voloshin A. Migration of the 3T3 Cell with a Lamellipodium on Various Stiffness Substrates-Tensegrity Model. Appl Sci. 2020 Sep 23;10(19):6644. [CrossRef]

- MICKAEL M. Modelling Baroreceptors Function. 2012;

- Dusi S, Angiari S, Pietronigro EC, Lopez N, Angelini G, Zenaro E, et al. LFA-1 Controls Th1 and Th17 Motility Behavior in the Inflamed Central Nervous System. Front Immunol. 2019; [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).