Introduction

In both Arab and non-Arab states, radicalism, violent extremism, and terrorism are central to current policy concerns. The terror these events have caused, their ties to larger tensions between and within faiths, and how they have shown a lack of social cohesion have all greatly impacted communities. Youth involvement is a trait of violent extremists nowadays. Even though this is common in violent extremist groups, it is strange that the group is mostly made up of young people and spread out geographically. Off the battlefield, young people acting as soldiers, executioners, and suicide bombers engage in even more unusual practices. Children and young people in fragile, conflict-torn, and developing countries face many risks, and these trends affect them differently. Due to the variety of roles they play, including actors in the fight, spectators, supporters, activists, or observers, people may also be exposed to extremists recruitment. Youth may also be subjected to unfair treatment by the legal system and national security threats. (Harper, 2018).

The 22 Arab League members have many linguistic, cultural, religious, and geographical connections. In addition, they have some demographic characteristics like population growth, age distribution, and marriage patterns. Around 300 million people live in Arab countries, and unlike other parts of the world, the population’s age distribution is still "young." More than half (54%) are still under 25 versus an estimated 48 percent for developing and 29 percent for developed countries. (UNPY, cited in Makhlouf, 2015), although ongoing population growth has resulted in several young individuals previously unheard of (Makhlouf, 2015). In the Arab world, 27% of its population are adolescents and young adults (10 to 24 years old). Realizing this potential will require urgent and significant investments because there are now few opportunities for meaningful education, social interaction, and work. This is particularly true for adolescents and young people, including women, refugees, and persons with special needs. There are still several issues, even at the base level of adolescent well-being. Children are the victims of violence in this area, which starts early and lasts forever. Bullying affects about 12 million children, or more than half of all 13 to 15-year-old students; in Egypt, Palestine, and Algeria, bullying is above 50%. Political unrest and conflicts have made adolescents and young people even more vulnerable, increasing their exposure to abuse, exploitation, and violence (World Bank, 2017; No Lost Generation Initiative, 2017; Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat, 2020).

Notwithstanding youth engagement in violent extremism, it is widely recognized that youngsters may play an equal role in preventing it. Youth should be seen as a nation’s asset since they represent its future and potential for leadership. On the other hand, It is problematic. It may threaten prosperity and peace since there is a growing "youth bulge" of unemployed young people striving to survive who are also susceptible to recruitment by violent extremist groups. (Mlambo, Nontobeko (2020).Young people must be protected since they are especially susceptible to various risks and dangers, such as alcohol abuse, violence, sexual exploitation, and harmful ideas. Young people should be seen as part of the solution and as the present, not simply the future. They also have the agency and capacity to act. Due to their ability to produce, contribute, and affect change, they are also co-creators. The Erasmus+ program, which is the European Union’s program for education, training, youth, and sport, supports the European Union through SALTO centers [Cultural Diversity (SALTO CD) is one of eight resource centers in the SALTO-Youth network (Support Advanced Learning and Training Opportunities for Youth)]. This youth program aims to modernize education, training, and work across Europe by developing knowledge and skills (SALTO Cultural Diversity Resource Centre, 2017). At the dawn of the twenty-first century, global patterns show extremist groups’ growth and rise. The study of these tensions has consequently brought attention to public unrest, human rights abuses, and societal instability (Dicko, A., Mousa, I., Oumaro, I., & Issaka, M., 2018). Researchers, politicians, and the local, national, and international communities are concerned about young people’s violent extremism in social, educational, and security contexts.

Young people are particularly susceptible to violent extremism. They represent a vulnerable and marginalized group in society who experience exclusion, disenfranchisement, resentment, and alienation from the broader group. The academic setting is perfect for religious radicals’ recruitment efforts for political parties and terrorist activities. Schools thus serve as a breeding ground for radicals (Al-Badayneh, 2012). Youth are the target of recruitment due to their environments that support extremism, such as identity crises among young people and other social crises like poverty, unemployment, inequality, and unjust treatment, as well as their marginalization and exclusion from the majority of significant aspects of life. Exclusion from political involvement, decision-making, and creating policies that serve their interests are only a few examples (Al-badayneh, Khalifa & Alhasan, 2016).

Many declarations focusing on youth and development have been made. These include the Amman Youth Declaration from August 2015, the UN Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 2250 on Youth, Peace, and Security from December 2015, and UNSC Resolution 2282 on the Review of the UN Peacebuilding Architecture from June 2016. These resolutions highlight young people’s crucial role in preventing conflict and upholding peace and security despite violent extremism (Ajodo-Adebanjoko, 2022). Research measurement has significantly impacted youth involvement in extremist organizations (Weslatin; Ben Salah, Al Nighaoui, & Russo; 2018). Most Arab states have adopted an anti-terrorism bill. Most Arab laws emphasize preventing youth from joining extremist groups and international efforts to counter terrorism and money laundering.

This research intends to construct a cross-cultural youth violent extremism scale that is valid, reliable, exhaustive and, takes into account cultural differences within and across Arab countries. A scale that can be applied and tested within one country or between more countries and cultures. Furthermore, conceptual construction of violent extremism can be identified utilizing scales at the abstract level. It also offers a knowledge base for formulating policies and applications for combating violent extremism among young people as well as ramifications for law and security.

The purpose of the study

This study aims to develop a valid, reliable, comprehensive cross-cultural youth violent extremism scale that takes into account within and between cultural differences and that can be applied and tested in a single or group of countries and cultures. Therefore, on the operational and methodological levels, the goal is to concisely develop an innovative, valid, reliable research tool to measure violent extremism. Furthermore, using scale on the abstract level can identify conceptual constructs of violent extremism. In addition, it provides a knowledge base for policy formation and legal and security implications and applications for preventing violent extremism among youths.

Rationale of the study

Extremism, in particular, needs strong theoretical and conceptual frameworks and strict methods from the research and expert communities. In addition, researchers must develop reliable and valid measurements to study a complex construct of violent extremism. Public policies must be based on relevant, easy-to-find information and a national and international goal. Therefore, researchers examined the motivations of the many players and the decision-making process to understand how young people in different cultures became extremists. However, as a complex construct, violent extremism lacks a general definition. Children’s right to fair treatment and a secure, nurturing environment that fosters their growth as vital members of society is threatened by violent extremism (Zogg, Kurki, Tuomala, & Haavisto, 2021).

The goal of the scale construction is to create an accurate and valid measure of a construct to evaluate a particular attribute. Scale development is challenging and time-consuming (Schmitt & Klimoski, 1991). This poses particular difficulties since it is almost impossible to observe. The non-observable constructs, such as self-report, must be indirectly evaluated as they cannot be measured directly. Furthermore, these constructs are often abstract. Finally, rather than being a single, standalone concept, these constructs are complex and may include many different components. Because of this complexity, it makes creating a measurement is a challenging task, and validation is crucial for creating scales (Tay & Jebb, 2017). Cronbach and Meehl described the complexity and difficulty of proving construct validity for such a measure. To avoid producing unclear data, researchers may develop standardized measures based on large heterogeneous samples as one of their goals. Using standardized measures would improve theory construction and testing and make it simpler to compare results (Price & Mueller, 1986). Future joint research in particular areas may succeed in the establishment of measurements.

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

According to various estimates, between 2011 and 2017, more than 30,000 foreign fighters from 81 different nations (15) joined violent extremist groups in Iraq and Syria. Even though most of the money came from the Middle East, about 20% came from Western states. This sparked interest in work causes and conditions. Indeed, how extremist groups, and Daesh in particular, attract participants in high numbers and from such diverse demographic groups baffles scholars and experts alike. (Harper 2018). In Neumann’s study of European foreign fighters, most believed they were "fighting against an existential threat." It accessed online content that showed Sunnis being slain, tortured, and raped. He concluded that their choice to fight was "more an emotional reaction to injustices perpetrated by an outside group, and less about a particular interpretation of one’s religious commitments." (Zachary, and Masters, 2014, Harper 2018).

Moreover, financial incentives play a role in Jordan. This disproved early theories that need drove extremist group membership. Each subject in the WANA Institute’s work with ex-combatants pointed to challenging living circumstances, financial limitations, unemployment and poor earnings, and irregular employment as the causes of their dejection. In addition, Atran, up to 75% of Daesh fighters were recruited through friendship networks; similar patterns were also noticed by Hegghammer, who looked at Afghan jihadists, and Roy, who looked at European Al-Queda recruits, both studying their subjects (Harper, 2018). The Australian Security Policy Institute noted that a small number of Australian youth, including those below the age of18, were radicalized and mobilized to travel to join jihadist groups in the Middle East (Barracosa and March, 2021).

According to research done on Muslim teenagers in the UK, where participants reported feeling in a "state of war" with the media, the government, and a broader security system, recruitment groups utilize such sentiments in both situations. In their recruitment videos, Al Shabaab and Daesh feature police brutality against Kenyan Muslims and (unverified) images of arbitrary arrests, detentions, and extrajudicial killings. Meanwhile, Al Shabaab has used footage of police harassing Kenyan Muslims, and Daesh has used images of widely publicized racial discrimination. (Harper 2018)

Jihadism’s appeal is connected to anger over injustice, poor leadership, and corruption. Restrictions on civic freedoms, widespread repression, and state-perpetrated (or sanctioned) rights abuses are the most significant factors that might lead a person to identify the state itself as an enemy. Rather than being a problem unique to a particular region, minorities in Western states today perceive new security measures like "stop and search" protocols and migrant vetting as a form of deliberate marginalization. (Bondokji, Agrabi, & Wilkinson, 2016).

According to research on Muslim teenagers in the UK, where participants reported feeling in a "state of war" with the media, the government, and a broader security system, recruitment groups utilize such sentiments in both situations. In their recruitment videos, Al Shabaab and Daesh feature police brutality against Kenyan Muslims and (unverified) images of arbitrary arrests, detentions, and extrajudicial killings. Meanwhile, Al Shabaab has used footage of police harassing Kenyan Muslims, and Daesh has used images of widely publicized racial discrimination. (Harper 2018).

Definitions of the construct of violent extremism

In practice, extremism manifests itself as broad categorizations, definite lines between groups, and a sense of "we" versus "them." Extreme minds don’t care about how complicated the social world is. Instead, they focus on strict categorizations and what seems true. Violent extremism is the use of violence, threats, and incitement to violence for ideological ends. The radical worldview and ideals justify the use of violence.

Theoretical Framework

Early studies tried out the idea of a terrorist persona: that people who did terrorist acts had mental weakness or other social instability. They did this by using both radicalization models and a terrorist typology. Evidence from the latest wave of violent extremists shows that fighter profiles are very different, even though most are young men. Researchers rejected the idea that neither ethnicity, social class, religious ideology, family background, nor socioeconomic status could explain participation in an extremist group. Instead, they turned to the idea that violent extremist action was the end stage of a process that started with radicalization. When used to explain the growth of Daesh and other extremist groups, none of the several explanation models are scientifically sound or accurate. A new perspective on the connection between radicalization and extreme activity has emerged. The decision to join a violent extremist group was still the result of the radicalization process. This was still influenced by particular "push" and "pull" elements. Pull factors are the positive qualities or advantages a group provides in exchange for membership. In contrast, human factors that influence decision-making are the detrimental social, political, economic, and cultural drivers. While hypotheses connecting radicalization to violent extremist conduct or group membership came under closer examination as the Daesh issue approached its fifth year. One claim was that the often cited push-pull and drivers were too general to consistently or effectively account for particular radicalization cases. Although individual cases may have been influenced by unemployment, political marginalization, or religious belief, these events are widespread, leaving models (Harper, 2018).

People are drawn into radical and violent movements through deliberate manipulation and accompaniment (socialization) processes, which are frequently aided by psychological, emotional, or personal factors like alienation, the search for identity and dignity, vengeance for past mistreatment, the breakdown of authority figures’ relationships with young people, as well as through online communities. So, a deeper examination and consideration of the pillars of the social structure of nations in danger of violent extremism is necessary. This is to prevent individuals from joining violent extremist groups. (United Nations Development Program, 2016).

A current UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR) report examined current State practices on policies and measures governing "violent extremism" (General Assembly Human Rights Council report A/HRC/33/29, 2016). The report also examined effective practices and lessons learned about how protecting and promoting human rights contributes to preventing and countering violent extremism. The phenomenon of violence is considered more widespread than terrorism, regardless of the definition. There are many different governmental and intergovernmental definitional approaches to violent extremism. Extremism is imposing beliefs, values, and ideologies on others by force to curtail civil and human rights (Schmidt, 2014). Extremism may include the following two essential characteristics (Borum, 2011). Firstly, the imposition of someone’s own beliefs, values, and ideologies on other human beings by force, and secondly, religious, gender, and race-based discrimination and violence to defraud the civil and human rights of minorities and others (Hassan, Khattak, Qureshi, & Iqbal, 2021, p.53).

Methodology

Scale development is challenging and time-consuming (Schmitt & Klimoski, 1991). Scale construction provides an accurate and valid measure of a construct. This is so that it can be used to evaluate the trait that is usually difficult to measure because it can’t be seen. Since you can’t directly measure things you can’t see, like how you feel about yourself, you have to evaluate them indirectly. Furthermore, these constructs are often abstract. Lastly, rather than being a single idea that stands alone, these "constructs" are often complicated and may have more than one part. Due to this complexity, it isn’t easy to create a measurement instrument, and validation is essential when making scales (Tay & Jebb, 2017).

Identification of the Initials Conceptual Dimensions

The following are identified dimensions; 1. Cult of power; 2. Admissibility of aggression; 3. Forcing consensus; 4. Intolerance; 5. Social pessimism; 6. Mysticism; 7. Destructiveness; 8. Passion for movement; 9. Normativism; 10. Ant introspection; 11. Conformity; 12. Religious centrism; 13. Grievance; 14. Jihadi groups; 15 Dogmatism; 16. Creed; 17. Ideological centrism; 18. Exclusion of others; 19. Group centrism; 20. Fascism; 21. Authoritarianism; 22. Closure and 23. Anti-Women.

Participants

Regarding the sample size for examining the psychometric properties of items, it has been recommended to be 100–200, with a confirmatory sample size of 300. Six thousand seven hundred twenty-six young students were drawn from 15 Arab countries’ public schools. The sample demographics included 47.9% males and 52.1% females; 79.4% identified themselves as citizens, and (20.6%) as Arab expatriates. The sample was distributed according to the region as follows: Gulf countries (36.1%), the Levant (25.4%), Maghrabi Arabi (16%), Egypt (7.5%), the West Bank (15%), and Gaza (15%).

Table 2 shows the participating countries.

Item Generation (Question Development)

The following methods were used to identify appropriate questions about the scale. The deductive method: This is based on the description of the relevant domain and item identification. This is done through a literature review and assessment of existing scales and indicators in that domain. The inductive method involves generating items from individuals’ responses. Qualitative data is obtained through direct observations and exploratory research methodologies, such as focus groups and individual interviews. Qualitative techniques were used to move the domain from an abstract point to its manifest forms. It is considered best practice to combine both deductive and inductive methods to define the domain and identify questions to assess it.

Content validity was estimated by evaluation by experts and judges. Content validity is assessed through evaluation by experts and target population judges. As judges, ten experts evaluated the first pool of questions and their relevance to Arab youth violent extremism. Expert judges are highly knowledgeable about the domain of interest and/or scale development; target population judges are potential users of the scale (DeVellis, 2012). Based on sample 1 (N=1401), 55 questions were generated that met the inclusion criteria. Items identified using deductive and inductive approaches were more comprehensive.

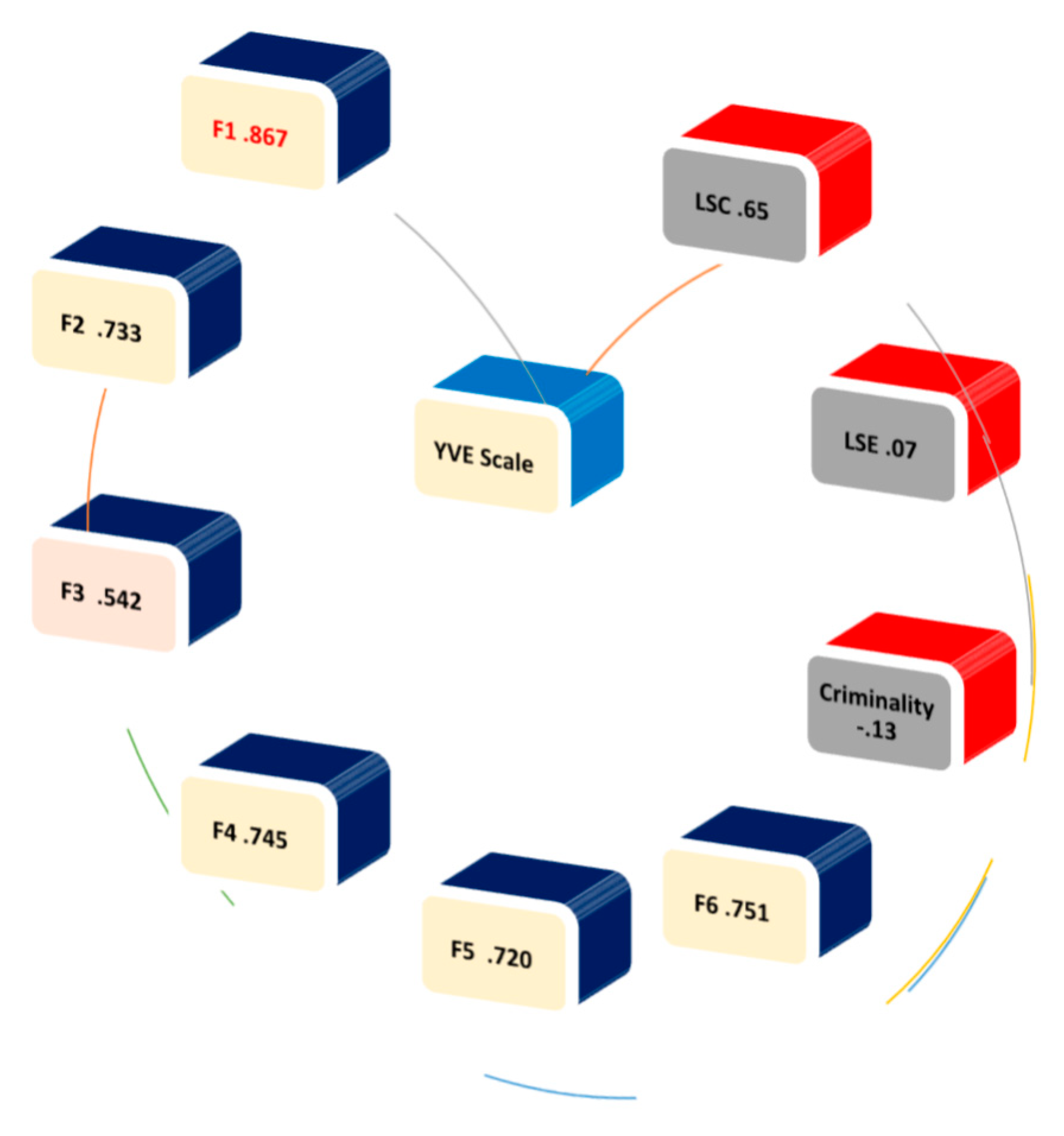

Nomological Network: Utilizing the multidimensional construct definition of violent extremism by outlining the nomological network to present how the violent extremism construct is related to its dimensions (factors) and to other constructs (

Figure 1). The principal component factor analysis revealed six factors. The F1 factor labeled "Exclusion of others & intolerance" (9 items), the F2 factor (4 items) "Rigidity & social pessimism," and the F3 factor (5 items) "Dogmatism & forcing consensus," the F4 factor (4 items) "Violence & Jihadi Groups," the F5 factor (3 items) "Cult of power, "and the F6 factor (4 items) "Grievances & mysticism."Since a scale empirically correlates with other recognized measures predicted by violent extremism theories and the literature review exhibits significant validity evidence, the nomological network will be crucial to the validation process (convergent and divergent validity) (Tay & Jebb, 2017).

Scale Refinement

Results of the Principle Factor Analysis

Dimensionality

Method: The violent extremism scale developed for the present study was derived from available literature on violent extremism and other relevant theories and scales, like the Aspar Extremism Scale (KSA). The scale has been constructed based on several studies and tests. In Study 1, a panel of 10 experts judged the first set of survey items from 1,401 students. A questionnaire was made based on research on the ASBAR Extremism Scale (KSA) (ASBAR, 2010, Al-Badayneh, & El-Hasan, 2017). The questionnaire asked about the person’s family, how they felt about justice and equality, and how proud they were of their country. Also, it are variables related to religiosity, force, criminality, violence, life stress events, and low self-control. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) found 23 domains and 55 items that make up the factors structure. Study 2 had a representative sample of (1116) university students with five domains representing 51 items (Al-Badayneh, Khalifa & Alhasan, 2016). Study 3 used EFA and identified 16 of 44 domains (i.e., women, education, media, jihadism, others, faith, jihadi groups, takfir, use of violence, power, others, fascism, dogmatism, rigidity, and grievances). Study 4 revealed six factors and 29 items. A replication of the factor structure proposed by Study 3 via confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) examined the validity of a related construct, violent extremist intentions (n = 4816). Items are selected with the following principles: simplicity, straightforwardness, and the avoidance of slang, jargon language, double negativity, ambiguity, or overly abstract or leading questions. The final scale questionnaire was written in Arabic. The Violent Extremism Scale (VES) consists of 29 items with six theoretical dimensions.

Findings

Instruments of Data Collection

Correlation coefficients were calculated and found to be statistically significant when the correlation matrix and sampling size were tested. However, the determinant (t = 4.85) and the correlation matrix are not singular and statistically significant using Bartlett’s test of sphericity (c = 69790.431, α = 0.000), which indicates that the correlation matrix is not an identity matrix.

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test was used to examine sample adequacy (homogeneity of the sample), and the KMO value in this study was 0.936. A value greater than zero (Kaiser, 1974) recommends that values greater than (0.5) are acceptable, values between (0.7-0.8) are acceptable, values between (0.8-0.9) are great, and values above (0.90) are superb. As can be seen, Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity presents six factors

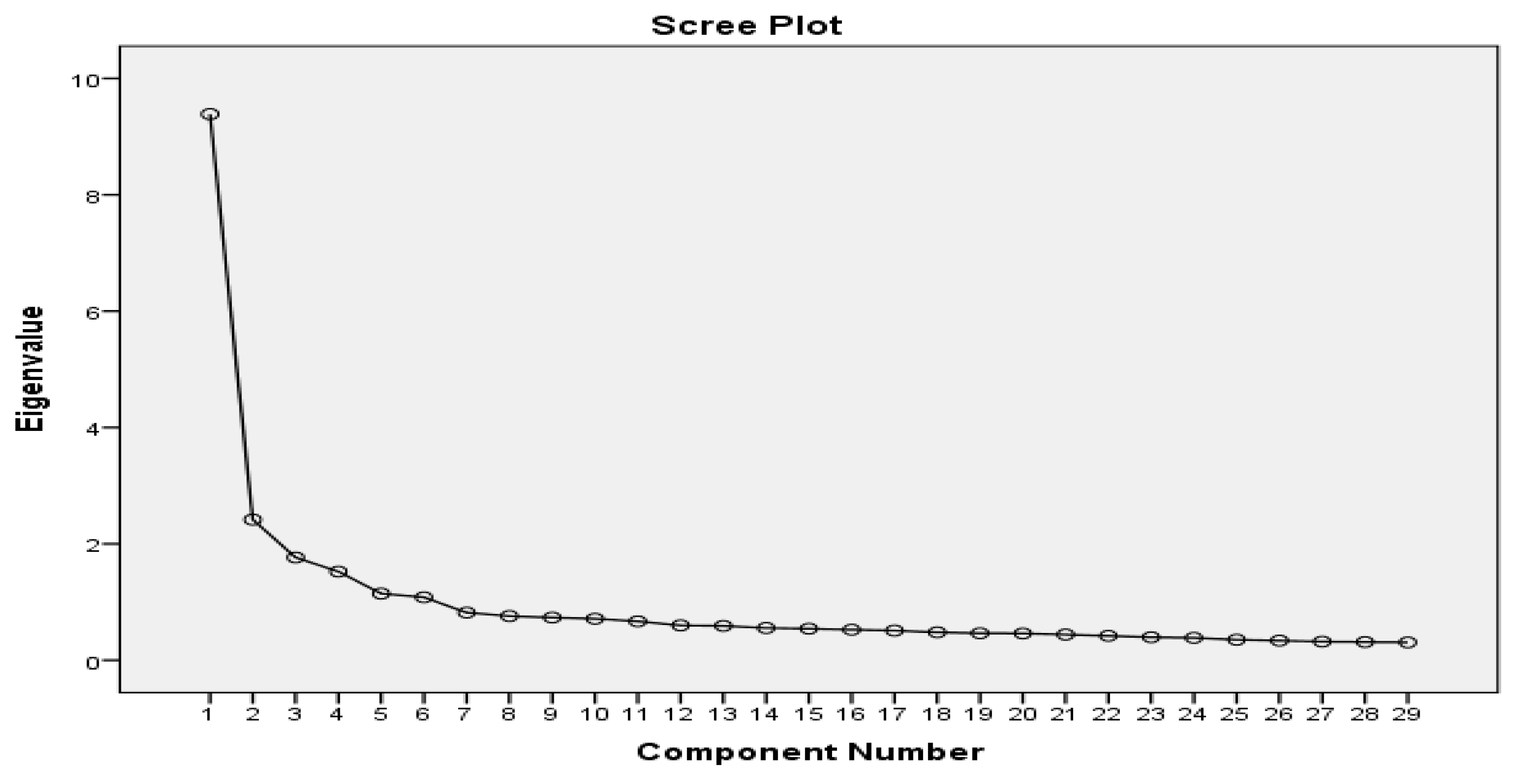

As can be seen from the screen plot, the suggested number of dimensions is 6. Also, factor loading analysis revealed six factors (components).

Item Reduction

The 29-item Violent Extremism Scale is distributed around the following factors:

Exclusion of others & intolerance

Rigidity & social pessimism

Dogmatism & forcing consensus

Violence & Jihadi Groups

Cult of power

Grievances & mysticism

A principal component factor analysis with varimax with Kaiser normalization rotation through SPSS (version 22) was used to empirically estimate the number of factors to determine which questions are to be retained. Applying the graphical method called the Scree test, first proposed by Cattell (1966), a scree plot was examined, and eigenvalue analysis (i.e., eigenvalue ≥ 1) suggested a 6-factor solution was appropriate for the data (see

Figure 2). The factor analysis used Varimax with Maximum Likelihood Rotation with the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy Stopping Rule. A factor solution was identified as a resolution of the factor analysis. The scatter plot analysis revealed that the six factors accounted for (59.724%) of the variance on the scale. A principal component factor analysis with variance correction and Kaiser normalization produced six factors (29 items) accounting for 59.7% of the total variance of youth violent extremism. The first factor, labeled "Exclusion of others & intolerance" (9 items), accounted for 15.3% of the variance, the second factor (4 items), "Rigidity & social pessimism," was responsible for 10.2%, and the third factor (5 items) "Dogmatism & forcing consensus" contributed 9.3% of the variance. The fourth factor (4 items), "Violence & Jihadi Groups," explained 9.2% of the variance. The fifth factor (3 items), "cult of power," explained 8 % of the variance, and the sixth factor (4 items), "Grievances & mysticism," explained 7.4% of the variance.

Reliability Analysis

Internal Reliability

The Cronbach Alpha for the 29-item Violent Extremism Scale was high (0.98), which means that the scale was very consistent within itself. Concurrent validity focuses on the accuracy of criteria for predicting a specific outcome. The scale’s validity was estimated by calculating the correlation between the Youth Violent Extremism Scale (YVES) and the Low Self-Control Scale. Results showed a significant positive relationship of 0.651, α = 0.000, indicating that the scale is valid (

Table 5).

Table 4 shows the correlation coefficients between the Youth Violent Extremism Scale and constructs, a proof of internal reliability.

Validity

In order to have good construct validity, one must have a strong relationship with convergent construct validity and no relationship with discriminant construct validity. In the table, the grand correlation is greater than.05, as shown, indicating good convergent validity. Moreover, all Cronbach alpha coefficients are higher than 0.70, considered acceptable for validity.

As can be seen from the following Table, all correlation coefficient means for each item is greater than .05 and this indicates a good convergent validity.

Table 7.

Youth violent extremism scale correlation coefficients.

Table 7.

Youth violent extremism scale correlation coefficients.

| Youth violent extremism scale correlation coefficients |

r |

| Exclusion of others & intolerance |

Mean= .5983 |

| 1. Q13. Non-Muslims in my country have no right to practice their religion, even in their homes. |

.614** |

| 2. Q14. All non-Muslims should be expelled from Muslim countries. |

.690** |

| 3. Q15. I believe anyone who is not a Muslim is an enemy of Islam. |

.552** |

| 4. Q2. In my country, the woman whose honor (rapped) is assaulted must be killed. |

.567** |

| 5. Q5. I believe, the school curriculum should include hatred of non-Muslims. |

.594** |

| 6. Q4. I believe in the exclusion of non-religious teachers from our schools. |

.627** |

| 7. Q9. I believe that tourism activities and events are corrupt. |

.601** |

| 8. Q29. I believe It’s okay to use violence to suppress opposition. |

.587** |

| 9. Q20. I believe those involved in terrorism incidents must be released from Arab prisons. |

.553 |

| Rigidity & social pessimism |

.5465 |

| 10. Q7. I believe the media intends to immoral our society. |

.501** |

| 11. Q8. I believe it is unfair the media describes the Arab Mujahideen as terrorists. |

.587** |

| 12. Q3. I believe in my country; women do not have equal rights with men in everything. |

.448** |

| 13. Q6. I believe young people should be encouraged to read books that encourage jihad. |

.650** |

| Dogmatism & forcing consensus |

.3762 |

| 14. Q33. I adhere to the customs and traditions and the consensus of my relatives on all issues. |

.378** |

| 15. Q.34 I consider offending a man of my religion an insult to my father. |

.372** |

| 16. Q38. Obedience to all kinds of authority is the most important thing a student must learn. |

.417** |

| 17. Q16. I believe My religious sect should be the state’s religion. |

.437** |

| 18. Q36. I consider raping a girl from my relatives is like raping my sister. |

.277** |

| Violence & Jihadi Groups |

.5578 |

| 19. Q21 I believe Jihadi groups must be supported with money and fighters. |

.626** |

| 20. Q22. I consider the ruler who rules other than what God has revealed an infidel. |

.533** |

| 21. Q19. I believe the jihadist groups will restore the glories of the nation. |

.640** |

| 22. Q23. I believe our society does not follow the correct faith. |

.432** |

| Cult of power |

.5880 |

| 23. Q11. I believe that jihad is the only way to preserve the doctrine. |

.602** |

| 24. Q10. I believe that martyrdom for the sake of God revives doctrine. |

.543** |

| 25. Q12. I see that jihad is the duty of every individual, even if the government does not agree. |

.619** |

| Grievances & mysticism |

.5500 |

| 26. Q44. I believe Muslims are oppressed in this world. |

.488** |

| 27. Q35. I consider the trial of a young man of my religion to be of my brother. |

.519** |

| 28. Q37. I consider a girl who evaluates an affair with a young man should be killed. |

.598** |

| 29. Q43. I believe injustice against Muslims must be lifted by jihad everywhere. |

.595** |

Table 8.

Convergent and Discriminant Validity of Scale (≥.03).

Table 8.

Convergent and Discriminant Validity of Scale (≥.03).

| |

Q13 |

Q14 |

Q15 |

Q2 |

Q5 |

Q4 |

Q9 |

Q29 |

Q20 |

| Q13 |

1 |

.577 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Q14 |

.577 |

1 |

.537 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Q15 |

.485 |

.537 |

1 |

.361 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Q2 |

.462 |

.446 |

.361 |

1 |

.414 |

|

|

|

|

| Q5 |

.445 |

.468 |

.364 |

.414 |

1 |

.473 |

|

|

|

| Q4 |

.414 |

.462 |

.342 |

.414 |

.473 |

1 |

.463 |

|

|

| Q9 |

.447 |

.446 |

.397 |

.392 |

.403 |

.463 |

1 |

.396 |

|

| Q29 |

.406 |

.451 |

.378 |

.378 |

.358 |

.425 |

.396 |

1 |

.329 |

| Q20 |

.418 |

.449 |

.347 |

.389 |

.409 |

.351 |

.368 |

.329 |

1 |

| |

Q7 |

Q8 |

Q3 |

Q6 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Q7 |

1 |

.492 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Q8 |

.492 |

1 |

.418 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Q3 |

.331 |

.418 |

1 |

.341 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Q6 |

.451 |

.517 |

.341 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Q23 |

Q34 |

Q38 |

Q16 |

Q36 |

|

|

|

|

| Q33 |

1 |

.452 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Q34 |

.452 |

1 |

.393 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Q38 |

.433 |

.393 |

1 |

.401 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Q16 |

.380 |

.324 |

.218 |

1 |

.218 |

|

|

|

|

| Q36 |

.301 |

.496 |

.174 |

.012 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

| |

Q21 |

Q22 |

Q19 |

Q23 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Q21 |

1 |

.418 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Q22 |

.418 |

1 |

.366 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Q19 |

.653 |

.366 |

1 |

.366 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Q23 |

.389 |

.357 |

.366 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Q11 |

Q10 |

Q112 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Q11 |

1 |

.490 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Q10 |

.490 |

1 |

.461 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Q12 |

.586 |

.461 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Q44 |

Q35 |

Q37 |

Q43 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Q44 |

1 |

.367 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Q35 |

.367 |

1 |

.404 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Q37 |

.358 |

.404 |

1 |

.411 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Q43 |

.469 |

.334 |

.411 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

Scale Validation

Conformity Factor Analysis

Table 9.

Total variance explained for the Final Violent Extremism Youth Scale’s items.

Table 9.

Total variance explained for the Final Violent Extremism Youth Scale’s items.

| Item |

Loading |

| Exclusion of others & intolerance |

15.380 |

| Q13. I believe Non-Muslims in my country have no right to practice their religion, even in their homes. |

.721 |

| Q14. All non-Muslims should be expelled from Muslim countries. |

.709 |

| Q15. I believe anyone who is not a Muslim is an enemy of Islam. |

.677 |

| Q2. I believe in my country, the woman whose honor is assaulted must be killed. |

.613 |

| Q5. I believe the school curriculum should include hatred of non-Muslims. |

.607 |

| Q4. I believe in the exclusion of non-religious teachers from our schools. |

.576 |

| Q9. I believe that tourism activities and events are corrupt. |

.568 |

| Q29. I believe It’s okay to use violence to suppress opposition. |

.567 |

| Q20. I believe those involved in terrorism incidents must be released from Arab prisons. |

.564 |

| Rigidity & social pessimism |

15.380 |

| Q7. I believe the media intents to corrupt our society. |

.723 |

| Q8. I believe it is unfair the media describes the Arab Mujahideen as terrorists. |

.662 |

| Q3. I believe in my country; women do not have equal rights with men in everything. |

.629 |

| Q6. I believe young people should be encouraged to read books that encourage jihad. |

.612 |

| Dogmatism & forcing consensus |

9.310 |

| Q33. I adhere to the customs and traditions and the consensus of my relatives on all issues. |

.735 |

| Q.34 I consider offending a man of my religion insulting my father. |

.733 |

| Q38. Obedience to all kinds of authority is the most important thing a student must learn. |

.716 |

| Q16. I believe My religious sect should be the state’s religion. |

.658 |

| Q36. I consider raping a girl from my relatives is like raping my sister. |

.646 |

| Violence & Jihadi Groups |

9.310 |

| Q21 I believe Jihadi groups must be supported with money and fighters. |

.635 |

| Q22. I consider the ruler who rules other than what God has revealed an infidel. |

.635 |

| Q19. I believe the jihadist groups will restore the glories of the nation. |

.581 |

| Q23. I believe our society does not follow the correct faith. |

.541 |

| Cult of power |

9.310 |

| Q11. I believe that jihad is the only way to preserve the doctrine. |

.699 |

| Q10. I believe that martyrdom for the sake of God revives doctrine. |

.697 |

| Q12. I see that jihad is the duty of every individual, even if the government does not agree. |

.662 |

| Grievances & mysticism |

7.457 |

| Q44. I believe Muslims are oppressed in this world. |

.697 |

| Q35. I consider the trial of a young man of my religion to be my brother. |

.617 |

| Q37. I consider a girl who evaluates an affair with a young man should be killed. |

.563 |

| Q43I believe injustice against Muslims must be lifted by jihad everywhere. |

.539 |

Gender Differences

Findings showed significant differences between males and females in violent extremism (F = 13.678, 0.000).

Table 10 shows the ANOVA analysis for the differences between males and females in youth extremism (see

Table 4). Descriptive results revealed, however, that females had a slightly higher mean of violent extremism than males (M =85.2 vs. 87.6), with a close variation (26 vs. 27) for males and females, respectively.

Table 10.

ANOVA Analysis for the Gender Differences in Violent Extremism.

Table 10.

ANOVA Analysis for the Gender Differences in Violent Extremism.

| |

Sum of Squares |

Mean Square |

df |

F |

Sig. |

| Between Groups |

9902.426 |

1 |

9902.426 |

13.678 |

.000 |

| Within Groups |

4806313.796 |

6639 |

723.951 |

|

|

| Total |

4816216.223 |

6640 |

|

|

|

Discussion

The literature on youth development underlines the importance for young people to transition into adulthood by having a diversity of experiences, abilities, and assets, which is a key lesson to be learnt. Despite young people’s involvement in violent extremism, it is commonly acknowledged that they can also prevent it. The issue is problematic, though. Since there is a growing "youth bulge" of unemployed young people trying to live who are also prone to be targeted and recruited by violent extremist groups, it might pose a threat to prosperity and peace. (Mlambo (2020). In order to comprehend what drives young people to become violent extremists and what effects it has, A need to a valid and reliable tool for measuring violent extremism. Understanding what can be done to help young people, shield them from violent extremism, and discourage them from acting violently in the future is equally crucial. Youth policies and strategies need to be updated and approved in accordance with universal human values in order to fully compensate for the lack of policies in education and development that are based on research.

This research aims to construct a cross-cultural youth violent extremism scale that is valid, reliable, extensive, and takes into account cultural differences across Arab countries. A scale that can be applied and tested within one country or between more countries and cultures. Furthermore, scales at the abstract level can be used to identify conceptual constructions of violent extremism. It provides a knowledge base for formulating policies and applications for combating violent extremism among young people.

Findings showed, the 29 items of the scale were dispersed across a scale made up of six factors, which together accounted for 59.7% of the variance in youth violent extremism. The first category, "exclusion of others & intolerance," which had nine items, accounted for 15.3% of the difference. The second component, "rigidity & social pessimism," was made up of four items and accounted for 10.2% of the variation. The third component, "dogmatism & forcing consensus," which contained five items, accounted for 9.3% of the variance. The fourth factor, (violence & jihadi groups), which had four items and accounted for 9.2% of the variance. The fifth factor (cult of power), which consisted of three items and explained 8% of the variance. The sixth factor (grievances and mysticism), which composed for four items and explained 7.4% of the variation. Results indicated that there were significant differences in youth violent extremism between males and females. In tight variation, females had a little greater mean of violent extremism than males. It appears that women internalize extremists beliefs as zero-order beliefs that females take unquestionable. Moreover, Women are victims of the culture of the shame and subject to stigmatized if deviant from these beliefs.

The key trait of an extremist dogmatic personality is highlighted by the results. Young extremists with a violent past are intolerant of difference and do not accept other people. Furthermore, this shows that violent extremist youth want to establish a homogeneous society. It is dangerous to only rely on counterterrorism tactics to stop violent extremism. The problems in people’s lives that have made recruiting and violent extremism easier need to be addressed. When one adopts a "social determinism" approach, it becomes evident that interconnected political, economic, and cultural variables dominate personal ones. Given the connections between these elements, it is understandable why some young Arabs would be drawn to extreme ideologies and violent extremist groups and organizations. According to Buchanan-Clarke’s (2016) research, certain extremist organizations and organizations in Nigeria had their roots in racial monoliths. Kelly-Clark & Kelly-Clark’s study from 2022, which found that Muslim clerics and Boko Haram restrict western education even if some of its members profit from it and think it corrupts, provided additional evidence for their argument. In Nigeria, they plan to create an Islamic empire. Extremists who restrict their interactions with the "other" generate societal rifts that are more prone to violence. This is particularly evident in Arab culture, where the political doctrine of Islam places a higher value on justice than on peace. Victoroff’s research backs up the assertion that the long-standing cultural custom of seeking vengeance against an oppressor is directly tied to the continuous violence in the Middle East. (Harper 2018). According to additional study, extremist organizations then profit from these conflicts by disseminating false information that justifies the marginalization of Muslims and offers them a reason to call for change. Examples include pictures of deceased people from US drone attacks and detainee abuse under the extraordinary rendition regime. (Harper 2018). The narrative of willful exclusion and the idea that elite interests have been fostered at the expense of "the rest" are highlighted. A gulf between the government and its citizens has been exacerbated by how unevenly these effects are distributed, more so than by poverty, socioeconomics, or a lack of possibilities. (Bondokji, Wilkinson, Agrabi, 2016).The findings showed that there were substantial disparities between males and girls in terms of youth violent extremism. In a narrow range, women showed a slightly higher mean of violent extremism than men Women are frequently stereotyped in violent and conflict situations as being passive, helpless, subordinate, and maternal. These presumptions promote gender biases. Women are consequently not viewed as prospective terrorists or as dangerous as their male counterparts if they were to engage in terrorism. However, it is incorrect to believe that women are more or less hazardous than men or more likely to engage in peaceful conversation, refrain from violence, and cooperate. In fact, terrorist organizations have highlighted the presence of women in their organizations to attract new members and to project an image of an innocent, nonviolent persona. (OSCE, 2013).

Legal, conceptual, and cultural understandings of how Arab adolescents engaged in violent extreme behaviors must be adopted by Arab countries. Additionally, Arab nations must understand how to use a knowledge-based approach to stop young people from becoming violent extremists. This necessitates that Arab nations have a broad perspective on violent extremism as a social, legal, political, educational, and ideological issue. a critical necessity for cooperation with Arab states to avoid and resist violent extremism within a state party. Youth can work with adults to stop extremism. In order to socialize children toward embracing others and a tolerant and peaceful education, women can be an effective agent. empowering via sport and education preventing youth from living in poverty and marginalization

Young people support or join such violent groups and organizations in opposition to or in revolt against a particular social and political setting. They also do it because they stand to gain considerably from it. This study offered an assessment tool that can act as a knowledge base for security measures. The policies and expressions of violent extremism in the legal, social, and educational realms can be identified using the current scale. Future research is necessary to test the scale in a variety of professions, including parenting, law enforcement, and teaching. The scale also needs to be evaluated across a range of cultures, settings, and age groups. A need for a to develop a theoretical and empirical paradigm for comprehending and countering teenage violent extremism.

The study offers a reliable scale for measuring youth violent extremism. This group is particularly susceptible to adopting ideas and attitudes that could one day inspire terrorism in the majority of nations. The scale has shown to be dependable and easy to use across numerous countries and cultures. This measure’s application might enable cross-cultural comparisons. Additional empirical validation is required before the measure may be used in a population segment other than university students. They might have special qualities that younger or older subgroups do not. The need to include all Arab states with various occupations and age groups was one of the study’s limitations.

References

- Ajodo-Adebanjoko, A., (2022). The Role of Youths in Countering Violent Extremism in Northeast Nigeria. Conflict & Resilience Monitor. https://www.accord.org.za/conflict-trends/the-role-of-youths-in-countering-violent-extremism-in-northeast-nigeria%EF%BF%BC/.

- Alava, S., Frau-Meigs, D., & Hassan, G. (2017). Youth and violent extremism on social media: Mapping the research. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Paris 07 SP, France. ISBN: 978-92-3-100245-8. Retrieved from file:///C:/Users/HP/Downloads/260382e%20(1).pdf.

- Al-Badayneh, D. & Al Hassan, K. (2017). Determinant factors of radicalization among Arab University students. Journal of Security Studies. 19 (2) 89-113. Retrieved from https://guvenlikcalismalari.pa.edu.tr/Upload/DergiDosya/arap-universite-ogrencileri-arasinda-radikallesmeye-yol-acan-faktorler-dergidosya5e46be25-2ea2-47a5-94d4-1f46da628d74.pdf.

- Al-Badayneh, D. (2012). Radicalization incubators and terrorism recruitment in the Arab world, pp 1-44 in The use of the Internet in terrorism finance and terrorists recruitment. NAUSS, KSA. Retrieved from http://www.nauss.edu.sa/Ar/DigitalLibrary/Books/Pages/Books.aspx?BookId=833.

- Al-Badayneh, D., Khelifa M. & Al Hassan, K. (2016). Radicalizing Arab University students: An emerging global threat. Journalism and Mass Communication, 6(2), 67-78. [CrossRef]

- ASBAR center. (2010). ASBAR scale for radicalization levels in KSA. Retrieved from https://asbar.com/site/?lang=en.

- Australian Government measures (2017). Update on Australian government measures to counter violent extremism: a quick guide. Research paper series, 2017–18 Retrieved from https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2017-08/apo-nid103081.pdf.

- Barracosa, S., & March, J. (2021). Dealing With Radicalized Youth Offenders: The Development and Implementation of a Youth-Specific Framework. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12. [CrossRef]

- Boateng G., Neilands T. B, Frongillo E. A., Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R. & Young, S. L. (2018). Best Practices for Developing and Validating Scales for Health, Social, and Behavioral Research: A Primer Front. Public Health, 6(149). [CrossRef]

- Bondokji, N., Agrabi, L. and Wilkinson, K., (2016). Understanding Radicalization: A Literature Review of Models and Drivers’ WANA Institute.

- Borum, R. (2011). Radicalization into Violent Extremism II: A review of conceptual models and empirical research. Journal of Strategic Security, 4(1), 37-62.

- Buchanan-Clarke, Stephen and Lekalake, Rorisang (2016) ‘Let the People Have a Say’, Afrobarometer Policy Paper No. 32.

- Cattell, R. B. (1966). The Scree Plot Test for the Number of Factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 1, pp. 140-161. Retrieved from. [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L. J., & Meehl, P. E. (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin, 52(4), pp. 281–302.

- DeVellis R. F. (2012). Scale development: Theory and application. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

- Dicko, A., Mousa, I., Oumaro, I., & Issaka, M., (2018). International Organization for Migration, p. 1. Retrieved from https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/youth_violence_en.pdf.

- Dokubo, Charles (2018) ‘Youth Empowerment and National Development in Nigeria: Niger Delta Amnesty Program in Perspective’, Paper presented at a National Defense College seminar on Enhancing National Development through Youth Empowerment, 3 October, Abuja.

- Glazzard A., & Martine Zeuthen, M. (2016). "Violent extremism," Retrieved from http://www.gsdrc.org/professional-dev/violent-extremism/.

- Government Offices of Sweden (2011). Sweden’s action plan to safeguard democracy against violence promoting extremism. Government Communication. /12:44, Point 3.2. Retrieved from https://www.government.se/49b75d/contentassets/b94f163a3c5941 aebaeb78174ea27a29/action-plan-to-safeguard-democracy-against-violence-promoting-extremism-skr.-20111244.

- H.M. Government (UK). (2015). Counter-Extremism Strategy. London, Counter-Extremism Directorate, Home Office. Para. [See to HM Government (2011). Prevent Strategy. The Stationery Office, Norwich. Annex A. Note that the 2013 UK Task Force on Tackling Radicalization and Extremism defined "Islamist extremism".] Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/97976/prevent-strategy-review.pdf.

- Harper, E. (2018) Reconceptualizing the drivers of violent extremism: an agenda for child & youth resilience. https://www.tdh.ch/sites/default/files/tdh_wana_pve_en_light.pdf.

- Kaiser, H.F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, 39, pp. 31-36.

- Makhlouf O. C. (2015). Adolescents in Arab countries: Health statistics and social context, DIFI Family Research and Proceedings:1 Retrieved from. [CrossRef]

- Mlambo, N. (2020) ‘Africa: Triple Threat – Conflict, Gender-Based Violence and COVID-19,’ All Africa, 26 April, Available at:https://allafrica.com/stories/202004240366.html.

- No Lost Generation Initiative. (2017). Translating research into scaled-up action: Evidence symposium on adolescents and youth in MENA (summary report). Retrieved from https://www.nolostgeneration.org/sites/default/files/eman/ Highlights/SUMMARY%20REPORT_ESAY2017.compressed.pdf https://www.nolostgeneration.org/.

- Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security. (2014). Action plan against radicalization and violent extremism. p.7 Retrieved from https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/Action-plan-against-Radicalisation-and-Violent-Extremism/id762413/.

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Development Assistance Committee (2016). DAC High-Level Meeting, Communiqué of 19 February 2016.

- OSCE (2013). OSCE ODIHR Expert Roundtables Preventing Women Terrorist Radicalization Vienna. The Role and Empowerment of Women in Countering Violent Extremism and Radicalization that Lead to Terrorism Vienna.

- Pickering, T. (2019). Developments in violent extremism in the Middle East and beyond: Proceedings of a workshop in brief. Retrieved from http://nap.naptionalacademies.org/25518.

- Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat. (2020). World Population Prospects 2019 revision. Retrieved from https://population.un.org/wpp/.

- Price, JL & Mueller, C.W. (1986). Absenteeism and Turnover of Hospital Employees, JAI, Greenwich, CT.

- Public Safety Canada, (2009). Report on plans and priorities. Retrieved from https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/lbrr/archives/hj%2013.a12%20t7%202008-09%20pt.3-p-eng.pdf.

- SALTO Cultural Diversity Resource Centre (2017). Young people and extremism: a resource for youth workers. SALTO Cultural Diversity Resource Centre. The European Commission and the British Council & Erasmus. Retrieved from Young People & Extremism: A Resource Pack for Youth Workers | Educational Tools Portal.

- Schmid, A. P. (2014). Violent and non-violent extremism: Two sides of the same coin. Research Paper. The Hague: ICCT.

- Schmitt; N.W., & Khmoski, R.J. (1991). Research methods s human resources management. Cincinnati: South-Western Publishing.

- Tay, L.,& Jebb, A. (2017). Scale development. In S. Rogelberg (Ed), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- UN (2015) ‘Amman Youth Declaration Adopted at Global Forum on Youth, Peace and Security’, Available at: https://www.un.org/youthenvoy/2015/08/amman-youth-declaration-adopted-global-forum-youth-peace-security> [Accessed 18 March 2020].

- UNESCO. (2017). Preventing violent extremism through education sustainable development goals. Guide for policy-makers. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Paris France ISBN 978-92-3-100215-1, Retrieved from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247764_eng.

- United Nations Office On Drugs And Crime UNODC (2020). Preventing Violent Extremism through Sport. Technical Guided https://www.unodc.org/documents/dohadeclaration/Sports/PVE/PVE_TechnicalGuide_EN.pdf.

- United Nations Office On Drugs And Crime UNODC. (2018). Radicalization’ and ’violent extremism. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/e4j/zh/terrorism/module-2/key-issues/ radicalization-violent-extremism.html.

- UNODC. (2018). Radicalization’ and ’violent extremism. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/e4j/zh/terrorism/module-2/key-issues/ radicalization-violent-extremism.html.

- USAID. (2011). "The development response to violent extremism and insurgency: Putting principles into practice." USAID Policy, September 2011. p. 2. Retrieved from https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1870/VEI_Policy_Final.pdf.

- Weslatin; O., Ben Salah,N., Al Nighaoui, I., Russo; F., (2018). Policy Brief The Legal And Judicial Framework Of Preventing Youth Radicalization. MEF. https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/bitstream/handle/10625/57738/57640.pdf.

- World Bank. (2017). Harmonized list of fragile situations. Retrieved from http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/ fragilityconflictviolence/brief/harmonized-list-of-fragile-situations.

- Zachary, L., and Masters, J., (2014). "The Islamic State in Iraq and Syria." Backgrounders. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/181537/Islamic%20State%20in%20Iraq%20and%20Greater%20Syria%20(Al-Qaeda%20in%20Iraq)%20-%20Council%20on%20Foreign%20Relations.pdf.

- Zogg, F., Kurki, A., Tuomala, V., & Haavisto, R. (2021). Save the Children, youth as a target for extremist recruitment, Retrieved from https://pelastakaalapset.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/main/2022/02/17133213/youth-as-a-target-for-extremist-recruitment_stc_en.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).