Submitted:

11 February 2023

Posted:

14 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

- 1)

- Preconditioning with cytokines:

- 2)

- Hypoxia preconditioning:

- 3)

- Immune receptor agonist:

- 4)

- 3-dimensional (3D)-culture:

- 5)

- Genetic manipulations:

- 6)

- Autophagy alteration:

- 7)

- Other agents:

Acknowledgments

References

- Matheakakis, A.; Batsali, A.; Papadaki, H.A.; Pontikoglou, C.G. Therapeutic Implications of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells and Their Extracellular Vesicles in Autoimmune Diseases: From Biology to Clinical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontikoglou, C.; Deschaseaux, F.; Sensebé, L.; Papadaki, H.A. Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Biological Properties and Their Role in Hematopoiesis and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2011, 7, 569–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedenstein, A.J.; Petrakova, K.V.; Kurolesova, A.I.; Frolova, G.P. HETEROTOPIC TRANSPLANTS OF BONE MARROW. Transplantation 1968, 6, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedenstein, A.J.; Chailakhjan, R.K.; Lalykina, K.S. The Development of Fibroblast Colonies in Monolayer Cultures of Guinea-Pig Bone Marrow and Spleen Cells. Cell Prolif. 1970, 3, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aj, F. Osteogenic stem cells in bone marrow. Bone Miner Res. 1990;243–72.

- Dominici, M.; Le Blanc, K.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.C.; Krause, D.S.; Deans, R.J.; Keating, A.; Prockop, D.J.; Horwitz, E.M. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squillaro, T.; Peluso, G.; Galderisi, U. Clinical Trials with Mesenchymal Stem Cells: An Update. Cell Transplant. 2016, 25, 829–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, S.; Shi, Y.; Galipeau, J.; Krampera, M.; Leblanc, K.; Martin, I.; Nolta, J.; Phinney, D.G.; Sensebe, L. Mesenchymal stem versus stromal cells: International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT®) Mesenchymal Stromal Cell committee position statement on nomenclature. Cytotherapy 2019, 21, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagg, J.; Pommey, S.; Eliopoulos, N.; Galipeau, J. Interferon-γ-stimulated marrow stromal cells: a new type of nonhematopoietic antigen-presenting cell. Blood 2006, 107, 2570–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romieu-Mourez R, François M, Boivin MN, Stagg J, Galipeau J. Regulation of MHC Class II Expression and Antigen Processing in Murine and Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells by IFN-γ, TGF-β, and Cell Density1. J Immunol. 2007 Aug 1;179(3):1549–58.

- Miclau, K.; Hambright, W.S.; Huard, J.; Stoddart, M.J.; Bahney, C.S. Cellular expansion of MSCs: Shifting the regenerative potential. Aging Cell 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galipeau, J.; Krampera, M.; Barrett, J.; Dazzi, F.; Deans, R.J.; DeBruijn, J.; Dominici, M.; Fibbe, W.E.; Gee, A.P.; Gimble, J.M.; et al. International Society for Cellular Therapy perspective on immune functional assays for mesenchymal stromal cells as potency release criterion for advanced phase clinical trials. Cytotherapy 2015, 18, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merimi, M.; El-Majzoub, R.; Lagneaux, L.; Agha, D.M.; Bouhtit, F.; Meuleman, N.; Fahmi, H.; Lewalle, P.; Fayyad-Kazan, M.; Najar, M. The Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for Regenerative Medicine: Current Knowledge and Future Understandings. [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 Jan 11];9. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caplan, AI. Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Time to Change the Name! STEM CELLS Transl Med. 2017;6(6):1445–51.

- Hmadcha, A.; Martin-Montalvo, A.; Gauthier, B.R.; Soria, B.; Capilla-Gonzalez, V. Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Cancer Therapy. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgado AJBOG, Reis RLG, Sousa NJC, Gimble JM, Salgado AJ, Reis RL, et al. Adipose Tissue Derived Stem Cells Secretome: Soluble Factors and Their Roles in Regenerative Medicine. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 5(2):103–10.

- Fan, X.-L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Fu, Q.-L. Mechanisms underlying the protective effects of mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 2771–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markov A, Thangavelu L, Aravindhan S, Zekiy AO, Jarahian M, Chartrand MS, et al. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells as a valuable source for the treatment of immune-mediated disorders. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021 Mar 18;12(1):192.

- Dunavin N, Dias A, Li M, McGuirk J. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: What Is the Mechanism in Acute Graft-Versus-Host Disease? Biomedicines [Internet]. 2017 Jul 1 [cited 2020 Jul 8];5(3). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. 5618.

- Garcia-Olmo D, Herreros D, Pascual I, Pascual JA, Del-Valle E, Zorrilla J, et al. Expanded Adipose-Derived Stem Cells for the Treatment of Complex Perianal Fistula: a Phase II Clinical Trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009 Jan;52(1):79.

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Zhu, C. Mesenchymal stem cells: potential application for the treatment of hepatic cirrhosis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-H.; Wu, D.-B.; Chen, B.; Chen, E.-Q.; Tang, H. Progress in mesenchymal stem cell–based therapy for acute liver failure. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattizzo, B.; Giannotta, J.A.; Barcellini, W. Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Aplastic Anemia and Myelodysplastic Syndromes: The “Seed and Soil” Crosstalk. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansboro, S.; Roelofs, A.J.; De Bari, C. Mesenchymal stem cells for the management of rheumatoid arthritis: immune modulation, repair or both? Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2017, 29, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uccelli, A.; Laroni, A.; Brundin, L.; Clanet, M.; Fernandez, O.; Nabavi, S.M.; Muraro, P.A.; Oliveri, R.S.; Radue, E.W.; Sellner, J.; et al. MEsenchymal StEm cells for Multiple Sclerosis (MESEMS): a randomized, double blind, cross-over phase I/II clinical trial with autologous mesenchymal stem cells for the therapy of multiple sclerosis. Trials 2019, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkman, R.; Offen, D. Concise Review: Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Stem Cells 2017, 35, 1867–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Furno, D.; Mannino, G.; Giuffrida, R. Functional role of mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of chronic neurodegenerative diseases. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 3982–3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasari, V.R.; Veeravalli, K.K.; Dinh, D.H. Mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of spinal cord injuries: A review. World J. Stem Cells 2014, 6, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu R, Feng Z, Wang FS. Mesenchymal stem cell treatment for COVID-19. eBioMedicine [Internet]. 2022 Mar 1 [cited 2023 Jan 22];77. Available from: https://www.thelancet. 2352.

- Kelly, K.; Rasko, J.E.J. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for the Treatment of Graft Versus Host Disease. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

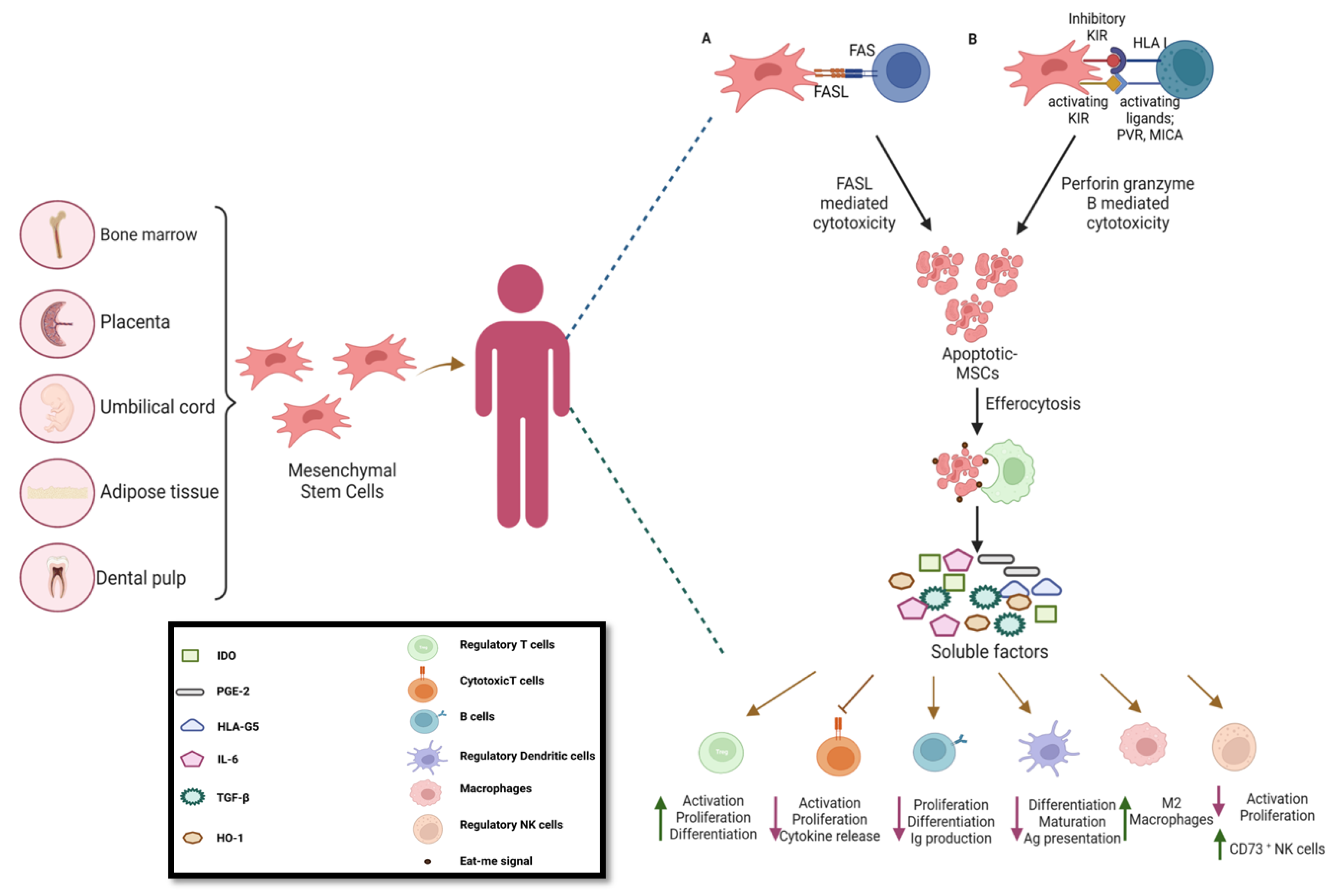

- Liu, S.; Liu, F.; Zhou, Y.; Jin, B.; Sun, Q.; Guo, S. Immunosuppressive Property of MSCs Mediated by Cell Surface Receptors. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matula, Z.; Németh, A.; Lőrincz, P.; Szepesi, A.; Brózik, A.; Buzás, E.I.; Lőw, P.; Német, K.; Uher, F.; Urbán, V.S. The Role of Extracellular Vesicle and Tunneling Nanotube-Mediated Intercellular Cross-Talk Between Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Human Peripheral T Cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2016, 25, 1818–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Wang, C.; He, T.; Zhao, T.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Shen, Y.-L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.-L. Mitochondrial Transfer from Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells to Motor Neurons in Spinal Cord Injury Rats via Gap Junction. Theranostics 2018, 9, 2017–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, M.E.; Fibbe, W.E. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: Sensors and Switchers of Inflammation. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 13, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eljarrah A, Gergues M, Pobiarzyn PW, Sandiford OA, Rameshwar P. Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Immune-Mediated Diseases. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1201:93–108.

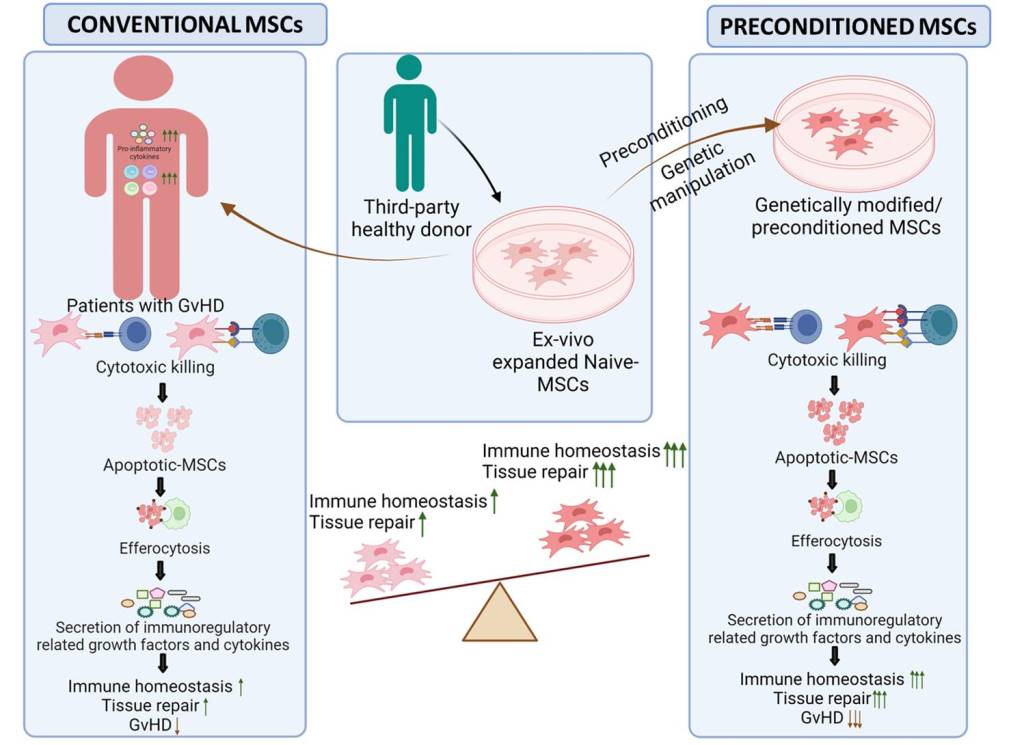

- Galleu, A.; Riffo-Vasquez, Y.; Trento, C.; Lomas, C.; Dolcetti, L.; Cheung, T.S.; von Bonin, M.; Barbieri, L.; Halai, K.; Ward, S.; et al. Apoptosis in mesenchymal stromal cells induces in vivo recipient-mediated immunomodulation. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, T.S.; Bertolino, G.M.; Giacomini, C.; Bornhaeuser, M.; Dazzi, F.; Galleu, A. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for Graft Versus Host Disease: Mechanism-Based Biomarkers. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, T.S.; Galleu, A.; von Bonin, M.; Bornhäuser, M.; Dazzi, F. Apoptotic mesenchymal stromal cells induce prostaglandin E2 in monocytes: implications for the monitoring of mesenchymal stromal cell activity. Haematologica 2019, 104, e438–e441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Tam, P.K.H. Immunomodulatory Mechanisms of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Their Potential Clinical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyurkchiev D, Bochev I, Ivanova-Todorova E, Mourdjeva M, Oreshkova T, Belemezova K, et al. Secretion of immunoregulatory cytokines by mesenchymal stem cells. World J Stem Cells. 2014 Nov 26;6(5):552–70.

- Jiang, W.; Xu, J. Immune modulation by mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Prolif. 2019, 53, e12712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, V.; Pavelić, E.; Vrdoljak, K.; Čemerin, M.; Klarić, E.; Matišić, V.; Bjelica, R.; Brlek, P.; Kovačić, I.; Tremolada, C.; et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Mechanisms of Action and Clinical Effects in Osteoarthritis: A Narrative Review. Genes 2022, 13, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galipeau, J.; Sensébé, L. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: Clinical Challenges and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 22, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Liu, G.; Halim, A.; Ju, Y.; Luo, Q.; Song, G. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Migration and Tissue Repair. Cells 2019, 8, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisbrich, M.; Becker, N.; Benner, A.; Radujkovic, A.; Schmitt, K.; Beimler, J.; Ho, A.D.; Zeier, M.; Dreger, P.; Luft, T. Transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy is an endothelial complication associated with refractoriness of acute GvHD. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017, 52, 1399–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luft, T.; Dietrich, S.; Falk, C.; Conzelmann, M.; Hess, M.; Benner, A.; Neumann, F.; Isermann, B.; Hegenbart, U.; Ho, A.D.; et al. Steroid-refractory GVHD: T-cell attack within a vulnerable endothelial system. Blood 2011, 118, 1685–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.N.; Li, X.; McMinn, J.R.; Terrell, D.R.; Vesely, S.K.; Selby, G.B. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura-hemolytic uremic syndrome following allogeneic HPC transplantation: a diagnostic dilemma. Transfusion 2004, 44, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, S.A.; Zhao, Q.; Yearsley, M.; Blower, L.; Agyeman, A.; Ranganathan, P.; Yang, S.; Wu, H.; Bostic, M.; Jaglowski, S.; et al. Complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathy as a link between endothelial damage and steroid-refractory GVHD. Blood Adv. 2018, 2, 2619–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.A.; Pallas, C.R.; Knovich, M.A. Transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy: theoretical considerations and a practical approach to an unrefined diagnosis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2021, 56, 1805–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Lin F. Decoy nanoparticles bearing native C5a receptors as a new approach to inhibit complement-mediated neutrophil activation. Acta Biomater. 2019 Nov;99:330–8.

- Moll G, Rasmusson-Duprez I, von Bahr L, Connolly-Andersen AM, Elgue G, Funke L, et al. Are Therapeutic Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Compatible with Human Blood? Stem Cells. 2012 Jul 1;30(7):1565–74.

- Moll, G.; Ankrum, J.A.; Kamhieh-Milz, J.; Bieback, K.; Ringdén, O.; Volk, H.-D.; Geissler, S.; Reinke, P. Intravascular Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem Cell Therapy Product Diversification: Time for New Clinical Guidelines. Trends Mol. Med. 2019, 25, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lin, F. Mesenchymal stem cells are injured by complement after their contact with serum. Blood 2012, 120, 3436–3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qiu, W.; Zhang, L.; Fung, J.; Lin, F. Painting factor H onto mesenchymal stem cells protects the cells from complement- and neutrophil-mediated damage. Biomaterials 2016, 102, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soland MA, Bego M, Colletti E, Zanjani ED, Jeor SS, Porada CD, et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Engineered to Inhibit Complement-Mediated Damage. PLOS ONE. 2013 Mar 26;8(3):e60461.

- Moll, G.; Jitschin, R.; Von Bahr, L.; Rasmusson-Duprez, I.; Sundberg, B.; Lönnies, L.; Elgue, G.; Nilsson-Ekdahl, K.; Mougiakakos, D.; Lambris, J.D.; et al. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Engage Complement and Complement Receptor Bearing Innate Effector Cells to Modulate Immune Responses. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e21703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Z.; Li, Q.; Bu, H.; Lin, F. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Inhibit Complement Activation by Secreting Factor H. Stem Cells Dev. 2010, 19, 1803–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatius, A.; Schoengraf, P.; Kreja, L.; Liedert, A.; Recknagel, S.; Kandert, S.; Brenner, R.E.; Schneider, M.; Lambris, J.D.; Huber-Lang, M. Complement C3a and C5a modulate osteoclast formation and inflammatory response of osteoblasts in synergism with IL-1β. J. Cell. Biochem. 2011, 112, 2594–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fung, J.; Lin, F. Local Inhibition of Complement Improves Mesenchymal Stem Cell Viability and Function After Administration. Mol. Ther. 2016, 24, 1665–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiser, R.; von Bubnoff, N.; Butler, J.; Mohty, M.; Niederwieser, D.; Or, R.; Szer, J.; Wagner, E.M.; Zuckerman, T.; Mahuzier, B.; et al. Ruxolitinib for Glucocorticoid-Refractory Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease. New Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1800–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriarca, F.; Sperotto, A.; Damiani, D.; Morreale, G.; Bonifazi, F.; Olivieri, A.; Ciceri, F.; Milone, G.; Cesaro, S.; Bandini, G.; et al. Infliximab treatment for steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease. . 2004, 89, 1352–9. [Google Scholar]

- Yalniz, F.F.; Hefazi, M.; McCullough, K.; Litzow, M.R.; Hogan, W.J.; Wolf, R.; Alkhateeb, H.; Kansagra, A.; Damlaj, M.; Patnaik, M.M. Safety and Efficacy of Infliximab Therapy in the Setting of Steroid-Refractory Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017, 23, 1478–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Blanc, K.; Rasmusson, I.; Sundberg, B.; Götherström, C.; Hassan, M.; Uzunel, M.; Ringdén, O. Treatment of severe acute graft-versus-host disease with third party haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells. Lancet 2004, 363, 1439–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Chen, S.; Yang, P.; Cao, H.; Li, L. The role of mesenchymal stem cells in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: prevention and treatment of graft-versus-host disease. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebriaei, P.; Hayes, J.; Daly, A.; Uberti, J.; Marks, D.I.; Soiffer, R.; Waller, E.K.; Burke, E.; Skerrett, D.; Shpall, E.; et al. A Phase 3 Randomized Study of Remestemcel-L versus Placebo Added to Second-Line Therapy in Patients with Steroid-Refractory Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2020, 26, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, M.; Terakura, S.; Wake, A.; Miyao, K.; Ikegame, K.; Uchida, N.; Kataoka, K.; Miyamoto, T.; Onizuka, M.; Eto, T.; et al. Off-the-shelf bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell treatment for acute graft-versus-host disease: real-world evidence. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2021, 56, 2355–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Fisher, S.; Cutler, A.; Doree, C.; Brunskill, S.J.; Stanworth, S.J.; Navarrete, C.; Girdlestone, J. Mesenchymal stromal cells as treatment or prophylaxis for acute or chronic graft-versus-host disease in haematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) recipients with a haematological condition. Emergencias 2019, 2019, CD009768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, M.; Terakura, S.; Wake, A.; Miyao, K.; Ikegame, K.; Uchida, N.; Kataoka, K.; Miyamoto, T.; Onizuka, M.; Eto, T.; et al. Off-the-shelf bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell treatment for acute graft-versus-host disease: real-world evidence. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2021, 56, 2355–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachmias B, Zimran E, Avni B. Mesenchymal stroma/stem cells: Haematologists’ friend or foe? Br J Haematol. 2022;199(2):175–89.

- Zhang, J.; Chen, M.; Liao, J.; Chang, C.; Liu, Y.; Padhiar, A.A.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, G. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Hold Lower Heterogeneity and Great Promise in Biological Research and Clinical Applications. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 716907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hao, J.; Hu, Z.; Yang, Y.-G.; Zhou, Q.; Sun, L.; Wu, J. Current status of clinical trials assessing mesenchymal stem cell therapy for graft versus host disease: a systematic review. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebriaei, P.; Isola, L.; Bahceci, E.; Holland, K.; Rowley, S.; McGuirk, J.; Devetten, M.; Jansen, J.; Herzig, R.; Schuster, M.; et al. Adult Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Added to Corticosteroid Therapy for the Treatment of Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009, 15, 804–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, M.; De La Mata, C.; Ruiz-García, A.; López-Fernández, E.; Espinosa, O.; Remigia, M.J.; Moratalla, L.; Goterris, R.; García-Martín, P.; Ruiz-Cabello, F.; et al. Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stromal cells as part of therapy for chronic graft-versus-host disease: A phase I/II study. Cytotherapy 2017, 19, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloor AJC, Patel A, Griffin JE, Gilleece MH, Radia R, Yeung DT, et al. Production, safety and efficacy of iPSC-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in acute steroid-resistant graft versus host disease: a phase I, multicenter, open-label, dose-escalation study. Nat Med. 2020 Nov;26(11):1720–5.

- Galderisi U, Peluso G, Di Bernardo G. Clinical Trials Based on Mesenchymal Stromal Cells are Exponentially Increasing: Where are We in Recent Years? Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2022;18(1):23–36.

- Kurtzberg, J.; Abdel-Azim, H.; Carpenter, P.; Chaudhury, S.; Horn, B.; Mahadeo, K.; Nemecek, E.; Neudorf, S.; Prasad, V.; Prockop, S.; et al. A Phase 3, Single-Arm, Prospective Study of Remestemcel-L, Ex Vivo Culture-Expanded Adult Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for the Treatment of Pediatric Patients Who Failed to Respond to Steroid Treatment for Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2020, 26, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Introna, M.; Lucchini, G.; Dander, E.; Galimberti, S.; Rovelli, A.; Balduzzi, A.; Longoni, D.; Pavan, F.; Masciocchi, F.; Algarotti, A.; et al. Treatment of Graft versus Host Disease with Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: A Phase I Study on 40 Adult and Pediatric Patients. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013, 20, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boome, L.C.J.T.; Mansilla, C.; E Van Der Wagen, L.; A Lindemans, C.; Petersen, E.J.; Spierings, E.; A Thus, K.; Westinga, K.; Plantinga, M.; Bierings, M.; et al. Biomarker profiling of steroid-resistant acute GVHD in patients after infusion of mesenchymal stromal cells. Leukemia 2015, 29, 1839–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Simon, J.A.; López-Villar, O.; Andreu, E.J.; Rifón, J.; Muntion, S.; Campelo, M.D.; Sánchez-Guijo, F.M.; Martinez, C.; Valcarcel, D.; Canizo, C.D. Mesenchymal stem cells expanded in vitro with human serum for the treatment of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease: results of a phase I/II clinical trial. Haematologica 2011, 96, 1072–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servais, S.; Baron, F.; Lechanteur, C.; Seidel, L.; Selleslag, D.; Maertens, J.; Baudoux, E.; Zachee, P.; Van Gelder, M.; Noens, L.; et al. Infusion of bone marrow derived multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells for the treatment of steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease: a multicenter prospective study. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 20590–20604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boberg, E.; Bahr, L.; Afram, G.; Lindström, C.; Ljungman, P.; Heldring, N.; Petzelbauer, P.; Legert, K.G.; Kadri, N.; Le Blanc, K. Treatment of chronic GvHD with mesenchymal stromal cells induces durable responses: A phase II study. STEM CELLS Transl. Med. 2020, 9, 1190–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.; Uberti, J.; Soiffer, R.; Klingemann, H.; Waller, E.; Daly, A.; Herrmann, R.; Kebriaei, P. Prochymal Improves Response Rates In Patients With Steroid-Refractory Acute Graft Versus Host Disease (SR-GVHD) Involving The Liver And Gut: Results Of A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Multicenter Phase III Trial In GVHD. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010, 16, S169–S170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soder, R.P.; Dawn, B.; Weiss, M.L.; Dunavin, N.; Weir, S.; Mitchell, J.; Li, M.; Shune, L.; Singh, A.K.; Ganguly, S.; et al. A Phase I Study to Evaluate Two Doses of Wharton's Jelly-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for the Treatment of De Novo High-Risk or Steroid-Refractory Acute Graft Versus Host Disease. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2020, 16, 979–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.G.; Yahng, S.-A.; Kim, I.; Lee, J.-H.; Min, C.-K.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, C.S.; Song, S.U. Allogeneic clonal mesenchymal stem cell therapy for refractory graft-versus-host disease to standard treatment: a phase I study. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2016, 20, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtzberg, J.; Prockop, S.; Teira, P.; Bittencourt, H.; Lewis, V.; Chan, K.W.; Horn, B.; Yu, L.; Talano, J.-A.; Nemecek, E.; et al. Allogeneic Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy (Remestemcel-L, Prochymal) as a Rescue Agent for Severe Refractory Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease in Pediatric Patients. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013, 20, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringden, O.; Baygan, A.; Remberger, M.; Gustafsson, B.; Winiarski, J.; Khoein, B.; Moll, G.; Klingspor, L.; Westgren, M.; Sadeghi, B. Placenta-Derived Decidua Stromal Cells for Treatment of Severe Acute Graft-Versus-Host Disease. STEM CELLS Transl. Med. 2018, 7, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi B, Remberger M, Gustafsson B, Winiarski J, Moretti G, Khoein B, et al. Long-Term Follow-Up of a Pilot Study Using Placenta-Derived Decidua Stromal Cells for Severe Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019 Oct 1;25(10):1965–9.

- Muroi, K.; Miyamura, K.; Ohashi, K.; Murata, M.; Eto, T.; Kobayashi, N.; Taniguchi, S.; Imamura, M.; Ando, K.; Kato, S.; et al. Unrelated allogeneic bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells for steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease: a phase I/II study. Int. J. Hematol. 2013, 98, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muroi, K.; Miyamura, K.; Okada, M.; Yamashita, T.; Murata, M.; Ishikawa, T.; Uike, N.; Hidaka, M.; Kobayashi, R.; Imamura, M.; et al. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (JR-031) for steroid-refractory grade III or IV acute graft-versus-host disease: a phase II/III study. Int. J. Hematol. 2015, 103, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrmann, R.; Sturm, M.; Shaw, K.; Purtill, D.; Cooney, J.; Wright, M.; Phillips, M.; Cannell, P. Mesenchymal stromal cell therapy for steroid-refractory acute and chronic graft versus host disease: a phase 1 study. Int. J. Hematol. 2011, 95, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen MZ, Liu XX, Qiu ZY, Xu LP, Zhang XH, Wang Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of mesenchymal stem cells treatment for multidrug-resistant graft-versus-host disease after haploidentical allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Ther Adv Hematol. 2022;13:20406207211072840.

- Kale, V.P. Application of “Primed” Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: Current Status and Future Prospects. Stem Cells Dev. 2019, 28, 1473–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.S.; Jang, I.K.; Lee, M.W.; Ko, Y.J.; Lee, D.-H.; Lee, J.W.; Sung, K.W.; Koo, H.H.; Yoo, K.H. Enhanced Immunosuppressive Properties of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Primed by Interferon-γ. EBioMedicine 2018, 28, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarsenova, M.; Kim, Y.; Raziyeva, K.; Kazybay, B.; Ogay, V.; Saparov, A. Recent advances to enhance the immunomodulatory potential of mesenchymal stem cells. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1010399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigo, T.; Procaccini, C.; Ferrara, G.; Baranzini, S.; Oksenberg, J.R.; Matarese, G.; Diaspro, A.; de Rosbo, N.K.; Uccelli, A. IFN-γ orchestrates mesenchymal stem cell plasticity through the signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 and 3 and mammalian target of rapamycin pathways. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 139, 1667–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Witte, S.F.H.; Franquesa, M.; Baan, C.C.; Hoogduijn, M.J. Toward Development of iMesenchymal Stem Cells for Immunomodulatory Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2016, 6, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noronha, N.D.C., Mizukami, A., Caliári-Oliveira, C., Cominal, J.G., Rocha, J.L.M., Covas, D.T., Swiech, K. and Malmegrim, K.C. Priming approaches to improve the efficacy of mesenchymal stromal cell-based therapies. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):131. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Tong, H.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Y.; Shan, F.; Meng, Y.; Yuan, Z. Comparative analysis of human mesenchymal stem cells from fetal-bone marrow, adipose tissue, and Warton's jelly as sources of cell immunomodulatory therapy. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2015, 12, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai, R.; Nakashima, A.; Doi, S.; Kimura, T.; Yoshida, K.; Maeda, S.; Ishiuchi, N.; Yamada, Y.; Ike, T.; Doi, T.; et al. Interferon-γ enhances the therapeutic effect of mesenchymal stem cells on experimental renal fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Jiang, Y.; Hou, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Zhong, L.; Fu, X. Potential pre-activation strategies for improving therapeutic efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells: current status and future prospects. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croitoru-Lamoury J, Lamoury FMJ, Caristo M, Suzuki K, Walker D, Takikawa O, et al. Interferon-γ Regulates the Proliferation and Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells via Activation of Indoleamine 2,3 Dioxygenase (IDO). PLOS ONE. 2011 Feb 16;6(2):e14698.

- Noone, C.; Kihm, A.; English, K.; O'Dea, S.; Mahon, B.P. IFN-γ Stimulated Human Umbilical-Tissue-Derived Cells Potently Suppress NK Activation and Resist NK-Mediated Cytotoxicity In Vitro. Stem Cells Dev. 2013, 22, 3003–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, J.M.; Barry, F.; Murphy, J.M.; Mahon, B.P. Interferon-γ does not break, but promotes the immunosuppressive capacity of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2007, 149, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potapova, I.A.; Gaudette, G.R.; Brink, P.R.; Robinson, R.B.; Rosen, M.R.; Cohen, I.S.; Doronin, S.V. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Support Migration, Extracellular Matrix Invasion, Proliferation, and Survival of Endothelial Cells In Vitro. STEM CELLS 2007, 25, 1761–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhang, S.H.; Lee, S.; Shin, J.-Y.; Lee, T.-J.; Kim, B.-S. Transplantation of Cord Blood Mesenchymal Stem Cells as Spheroids Enhances Vascularization. Tissue Eng. Part A 2012, 18, 2138–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouroupis, D.; Correa, D. Increased Mesenchymal Stem Cell Functionalization in Three-Dimensional Manufacturing Settings for Enhanced Therapeutic Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, B.; Enhejirigala; Li, Z. ; Song, W.; Wang, Y.; Duan, X.; Yuan, X.; et al. Biophysical and Biochemical Cues of Biomaterials Guide Mesenchymal Stem Cell Behaviors. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; He, Y.R.; Liu, S.J.; Hu, L.; Liang, L.C.; Liu, D.L.; Liu, L.; Zhu, Z.Q. Enhanced Effect of IL-1β-Activated Adipose-Derived MSCs (ADMSCs) on Repair of Intestinal Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury via COX-2-PGE2 Signaling. Stem Cells Int. 2020, 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhu, X.; Cao, X.; Chi, A.; Dai, J.; Wang, Z.; Deng, C.; Zhang, M. IL-1β-primed mesenchymal stromal cells exert enhanced therapeutic effects to alleviate Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome through systemic immunity. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Cui, B.; Zhang, W.; Ma, W.; Zhao, G.; Xing, L. Exosomal miR-21 secreted by IL-1β-primed-mesenchymal stem cells induces macrophage M2 polarization and ameliorates sepsis. Life Sci. 2020, 264, 118658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGeachy, M.J.; Cua, D.J.; Gaffen, S.L. The IL-17 Family of Cytokines in Health and Disease. Immunity 2019, 50, 892–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivanathan, K.N.; Rojas-Canales, D.; Grey, S.T.; Gronthos, S.; Coates, P.T. Transcriptome Profiling of IL-17A Preactivated Mesenchymal Stem Cells: A Comparative Study to Unmodified and IFN-γModified Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cells Int. 2017, 2017, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du-Rocher B, Binato R, de-Freitas-Junior JCM, Corrêa S, Mencalha AL, Morgado-Díaz JA, et al. IL-17 Triggers Invasive and Migratory Properties in Human MSCs, while IFNy Favors their Immunosuppressive Capabilities: Implications for the “Licensing” Process. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2020 Dec 1;16(6):1266–79.

- Sivanathan, K.N.; Rojas-Canales, D.M.; Hope, C.M.; Krishnan, R.; Carroll, R.P.; Gronthos, S.; Grey, S.T.; Coates, P.T. Interleukin-17A-Induced Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Are Superior Modulators of Immunological Function. STEM CELLS 2015, 33, 2850–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Su, J.; Hu, Y.; Huang, Q.; Shi, H.; Wang, L.; Ren, J. Interleukin-25 primed mesenchymal stem cells achieve better therapeutic effects on dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis via inhibiting Th17 immune response and inducing T regulatory cell phenotype. . 2017, 9, 4149–4160. [Google Scholar]

- Kook, Y.J.; Lee, D.H.; Song, J.E.; Tripathy, N.; Jeon, Y.S.; Jeon, H.Y.; Oliveira, J.M.; Reis, R.L.; Khang, G. Osteogenesis evaluation of duck’s feet-derived collagen/hydroxyapatite sponges immersed in dexamethasone. Biomater. Res. 2017, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares, G.R.; Chiu, C.-T.; Scheuing, L.; Leng, Y.; Liao, H.-M.; Maric, D.; Chuang, D.-M. Preconditioning mesenchymal stem cells with the mood stabilizers lithium and valproic acid enhances therapeutic efficacy in a mouse model of Huntington's disease. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 281, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisel, S.; Khan, M.; Kuppusamy, M.L.; Mohan, I.K.; Chacko, S.M.; Rivera, B.K.; Sun, B.C.; Hideg, K.; Kuppusamy, P. Pharmacological Preconditioning of Mesenchymal Stem Cells with Trimetazidine (1-[2,3,4-Trimethoxybenzyl]piperazine) Protects Hypoxic Cells against Oxidative Stress and Enhances Recovery of Myocardial Function in Infarcted Heart through Bcl-2 Expression. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009, 329, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackel A, Aksamit A, Bruderek K, Lang S, Brandau S. TNF-α and IL-1β sensitize human MSC for IFN-γ signaling and enhance neutrophil recruitment. Eur J Immunol. 2021;51(2):319–30.

- Philipp, D.; Suhr, L.; Wahlers, T.; Choi, Y.-H.; Paunel-Görgülü, A. Preconditioning of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells highly strengthens their potential to promote IL-6-dependent M2b polarization. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Jin, H.J.; Heo, J.; Ju, H.; Lee, H.-Y.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Lim, J.; Jeong, S.Y.; Kwon, J.; et al. Small hypoxia-primed mesenchymal stem cells attenuate graft-versus-host disease. Leukemia 2018, 32, 2672–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, J.R.K.; Rangasami, V.K.; Samanta, S.; Varghese, O.P.; Oommen, O.P. Discrepancies on the Role of Oxygen Gradient and Culture Condition on Mesenchymal Stem Cell Fate. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 10, 2002058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, R.S.; Tomchuck, S.L.; Henkle, S.L.; Betancourt, A.M. A New Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC) Paradigm: Polarization into a Pro-Inflammatory MSC1 or an Immunosuppressive MSC2 Phenotype. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e10088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, S.; Mantovani, A. Diversity and plasticity of mononuclear phagocytes. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011, 41, 2470–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Y.; Guo, J.; Mao, R.; Chao, K.; Chen, B.-L.; He, Y.; Zeng, Z.-R.; Zhang, S.-H.; Chen, M.-H. TLR3 preconditioning enhances the therapeutic efficacy of umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells in TNBS-induced colitis via the TLR3-Jagged-1-Notch-1 pathway. Mucosal Immunol. 2017, 10, 727–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He X, Wang H, Jin T, Xu Y, Mei L, Yang J. TLR4 Activation Promotes Bone Marrow MSC Proliferation and Osteogenic Differentiation via Wnt3a and Wnt5a Signaling. PLOS ONE. 2016 Mar 1;11(3):e0149876.

- Rashedi, I.; Gómez-Aristizábal, A.; Wang, X.-H.; Viswanathan, S.; Keating, A. TLR3 or TLR4 Activation Enhances Mesenchymal Stromal Cell-Mediated Treg Induction via Notch Signaling. STEM CELLS 2016, 35, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linard, C.; Strup-Perrot, C.; Lacave-Lapalun, J.-V.; Benderitter, M. Flagellin preconditioning enhances the efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells in an irradiation-induced proctitis model. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2016, 100, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, A.; Rumbo, M.; Carnoy, C.; Sirard, J.-C. Compartmentalized Antimicrobial Defenses in Response to Flagellin. Trends Microbiol. 2018, 26, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangiorgi, B.B.; Leão, V.; Schiavinato, J.L.d.S.; Orellana, M.D.; Zago, M.A.; Covas, D.T.; Panepucci, R.A.; Rego, E.M. TLR9 Priming Promotes Proliferation Of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Restores The Immunosuppressive Activity Impaired By TLR4 Priming: Potential Involvement Of Non-Canonical NF-Kb Signaling. Blood 2013, 122, 2458–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvites, R.; Branquinho, M.; Sousa, A.C.; Lopes, B.; Sousa, P.; Maurício, A.C. Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells and Their Paracrine Activity—Immunomodulation Mechanisms and How to Influence the Therapeutic Potential. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.-C.; Kang, K.-S. Functional enhancement strategies for immunomodulation of mesenchymal stem cells and their therapeutic application. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.K.; Sarsenova, M.; Kim, D.-H.; Kim, M.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Sung, E.-A.; Kook, M.G.; Kim, N.G.; Choi, S.W.; Ogay, V.; et al. Establishing a 3D In Vitro Hepatic Model Mimicking Physiologically Relevant to In Vivo State. Cells 2021, 10, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sart, S.; Ma, T.; Li, Y. Preconditioning Stem Cells for In Vivo Delivery. BioResearch Open Access 2014, 3, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrenko, Y.; Syková, E.; Kubinová, Š. The therapeutic potential of three-dimensional multipotent mesenchymal stromal cell spheroids. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017, 8, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, S.; Reis, R.L.; Oliveira, J.M. Recent advances using gold nanoparticles as a promising multimodal tool for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2016, 21, 92–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, H.-S.; Kung, M.-L.; Chen, F.-C.; Ke, Y.-C.; Shen, C.-C.; Yang, Y.-C.; Tang, C.-M.; Yeh, C.-A.; Hsieh, H.-H.; Hsu, S.-H. Nanogold-Carried Graphene Oxide: Anti-Inflammation and Increased Differentiation Capacity of Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathi-Achachelouei, M.; Knopf-Marques, H.; da Silva, C.E.R.; Barthes, J.; Bat, E.; Tezcaner, A.; Vrana, N.E. Use of Nanoparticles in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, R.G.; Muthoosamy, K.; Manickam, S.; Hilal-Alnaqbi, A. Graphene-based 3D scaffolds in tissue engineering: fabrication, applications, and future scope in liver tissue engineering. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, ume 14, 5753–5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hnatiuk AP, Ong S, Olea FD, Locatelli P, Riegler J, Lee WH, et al. Allogeneic Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Overexpressing Mutant Human Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1-α (HIF1-α) in an Ovine Model of Acute Myocardial Infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 5(7):e003714.

- Yang, J.-X.; Zhang, N.; Wang, H.-W.; Gao, P.; Yang, Q.-P.; Wen, Q.-P. CXCR4 Receptor Overexpression in Mesenchymal Stem Cells Facilitates Treatment of Acute Lung Injury in Rats. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 1994–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, W.-B.; Zhang, D.; Wang, L.-S. Growth Factor Gene-Modified Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Tissue Regeneration. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2020, 14, 1241–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, H.-S.; Roh, K.-H.; Lee, B.-C.; Shin, T.-H.; Yoo, J.-M.; Kim, Y.-L.; Yu, K.-R.; Kang, K.-S.; Seo, K.-W. DNA methyltransferase inhibition accelerates the immunomodulation and migration of human mesenchymal stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, srep08020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Carvalho, A.E.; Rodrigues, L.P.; Schiavinato, J.L.; Alborghetti, M.R.; Bettarello, G.; Simoes, B.P.; Neves, F.d.A.R.; Panepucci, R.A.; de Carvalho, J.L.; Saldanha-Araujo, F. GVHD-derived plasma as a priming strategy of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oses, C.; Olivares, B.; Ezquer, M.; Acosta, C.; Bosch, P.; Donoso, M.; Léniz, P.; Ezquer, F. Preconditioning of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells with deferoxamine increases the production of pro-angiogenic, neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory factors: Potential application in the treatment of diabetic neuropathy. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0178011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, M.; Huang, L.; Rossi, E.; Blandinières, A.; Israel-Biet, D.; Gaussem, P.; Bischoff, J.; Smadja, D.M. Treprostinil indirectly regulates endothelial colony forming cell angiogenic properties by increasing VEGF-A produced by mesenchymal stem cells. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2015, 114, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourjafar M, Saidijam M, Mansouri K, Ghasemibasir H, Karimi dermani F, Najafi R. All-trans retinoic acid preconditioning enhances proliferation, angiogenesis and migration of mesenchymal stem cell in vitro and enhances wound repair in vivo. Cell Prolif. 2017;50(1):e12315.

- Zhang, R.; Yin, L.; Zhang, B.; Shi, H.; Sun, Y.; Ji, C.; Chen, J.; Wu, P.; Zhang, L.; Xu, W.; et al. Resveratrol improves human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells repair for cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Concannon, J.; Ng, K.S.; Seyb, K.; Mortensen, L.J.; Ranganath, S.; Gu, F.; Levy, O.; Tong, Z.; Martyn, K.; et al. Tetrandrine identified in a small molecule screen to activate mesenchymal stem cells for enhanced immunomodulation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiselevskii MV, Vlasenko RYa, Stepanyan NG, Shubina IZh, Sitdikova SM, Kirgizov KI, et al. Secretome of Mesenchymal Bone Marrow Stem Cells: Is It Immunosuppressive or Proinflammatory? Bull Exp Biol Med. 2021 Dec 1;172(2):250–3.

- Munoz-Perez, E.; Gonzalez-Pujana, A.; Igartua, M.; Santos-Vizcaino, E.; Hernandez, R.M. Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Secretome for the Treatment of Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases: Latest Trends in Isolation, Content Optimization and Delivery Avenues. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, P.; Chen, X.; Guo, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, T.; Huang, T.; Geng, S.; Luo, C.; et al. A potent immunomodulatory role of exosomes derived from mesenchymal stromal cells in preventing cGVHD. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 11, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collo, G.D.; Adamo, A.; Gatti, A.; Tamellini, E.; Bazzoni, R.; Kamga, P.T.; Tecchio, C.; Quaglia, F.M.; Krampera, M. Functional dosing of mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles for the prevention of acute graft-versus-host-disease. STEM CELLS 2020, 38, 698–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Gu, Z.; Zhao, X.; Yang, N.; Wang, F.; Deng, A.; Zhao, S.; Luo, L.; Wei, H.; Guan, L.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles Released from Human Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Prevent Life-Threatening Acute Graft-Versus-Host Disease in a Mouse Model of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Stem Cells Dev. 2016, 25, 1874–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Yeo, R.W.Y.; Lai, R.C.; Sim, E.W.K.; Chin, K.C.; Lim, S.K. Mesenchymal stromal cell exosome–enhanced regulatory T-cell production through an antigen-presenting cell–mediated pathway. Cytotherapy 2018, 20, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, S.; Miura, Y.; Fujishiro, A.; Shindo, T.; Shimazu, Y.; Hirai, H.; Tahara, H.; Takaori-Kondo, A.; Ichinohe, T.; Maekawa, T. Graft-Versus-Host Disease Amelioration by Human Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Is Associated with Peripheral Preservation of Naive T Cell Populations. STEM CELLS 2018, 36, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).