Submitted:

01 February 2023

Posted:

03 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

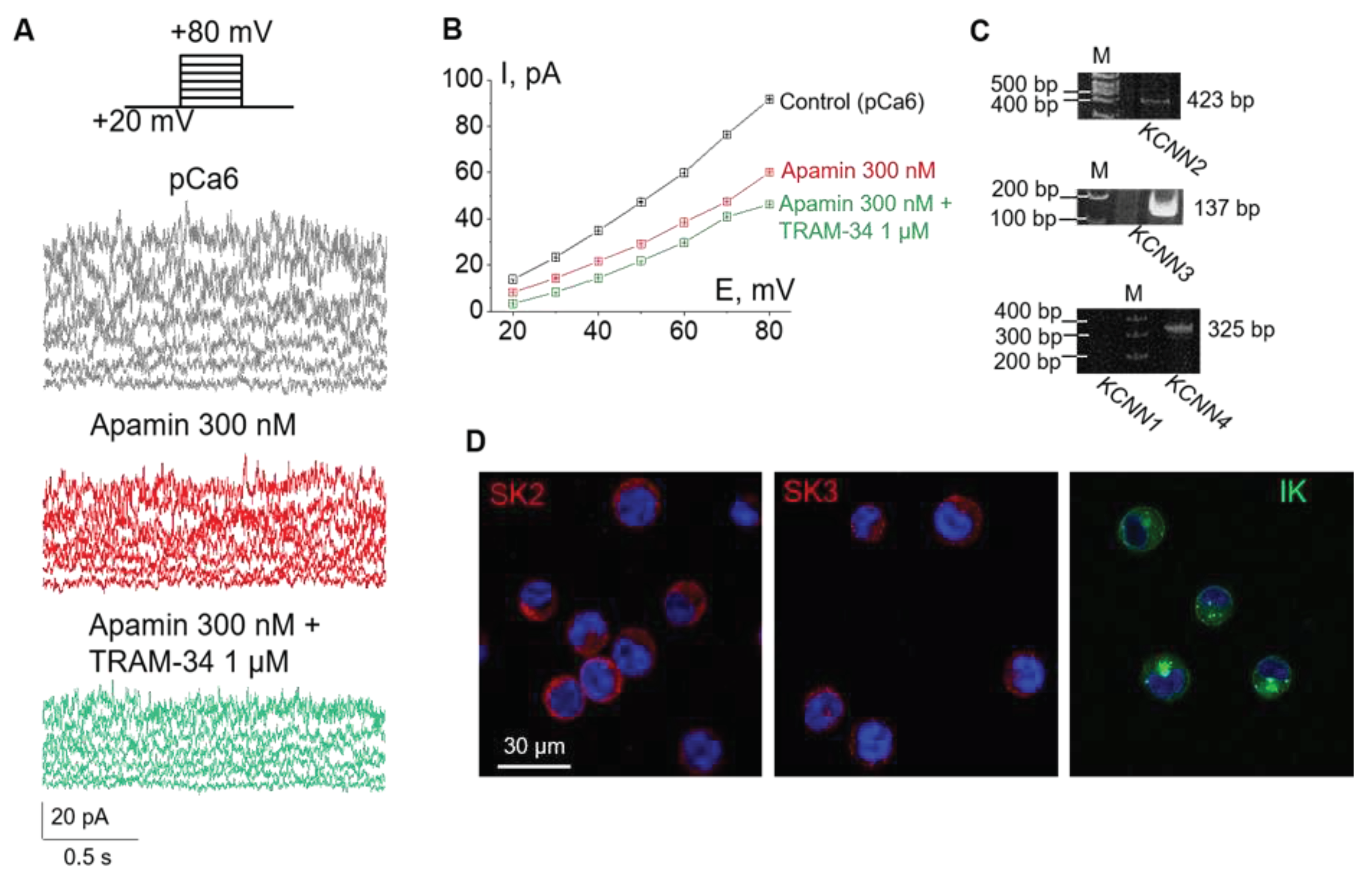

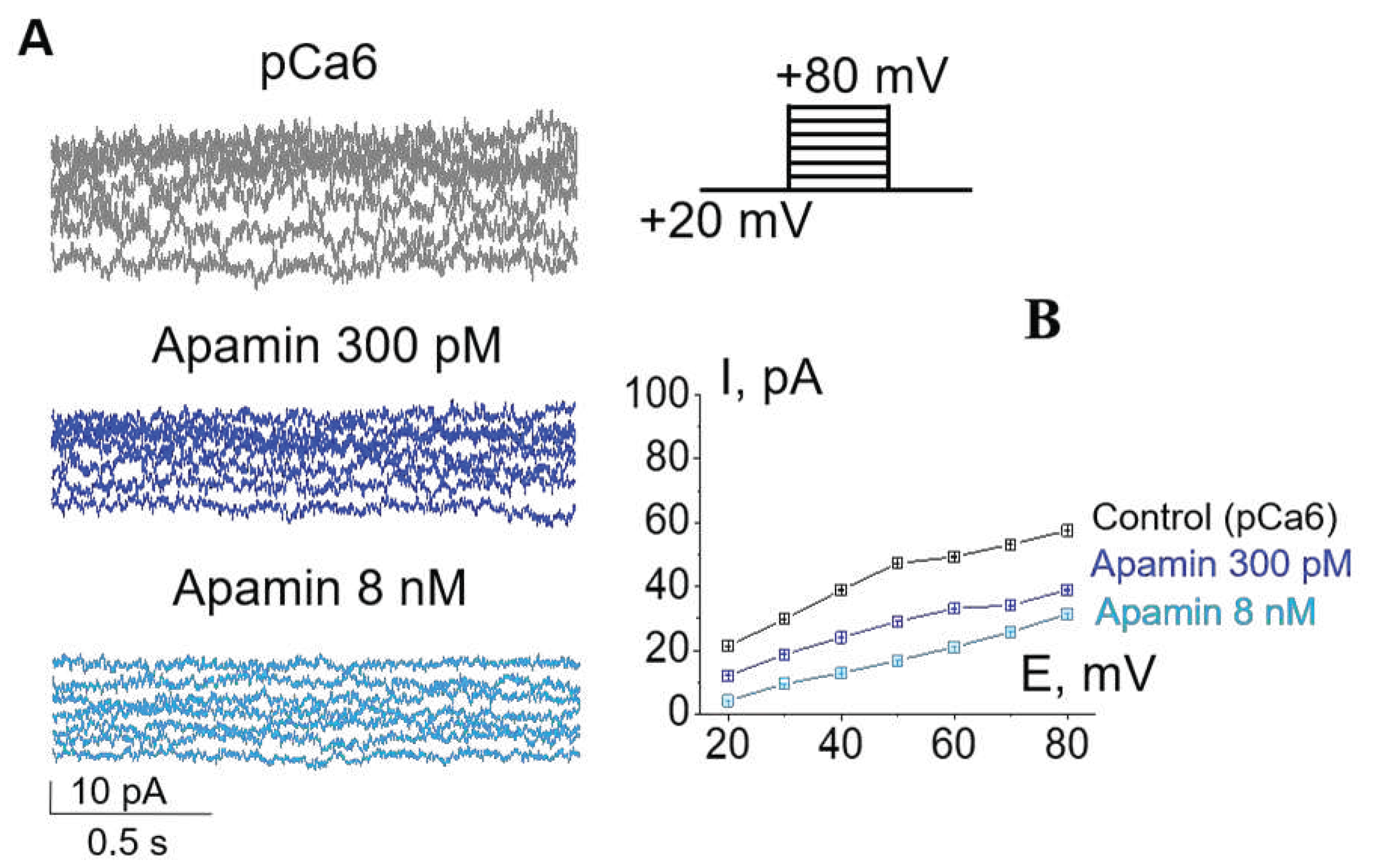

2.1. Selective SK and IK channel blockers inhibit whole-cell currents in the plasma membrane of human myeloid leukemia cells

2.2. Functional expression of SK2, SK3 and IK channels in K562 cells

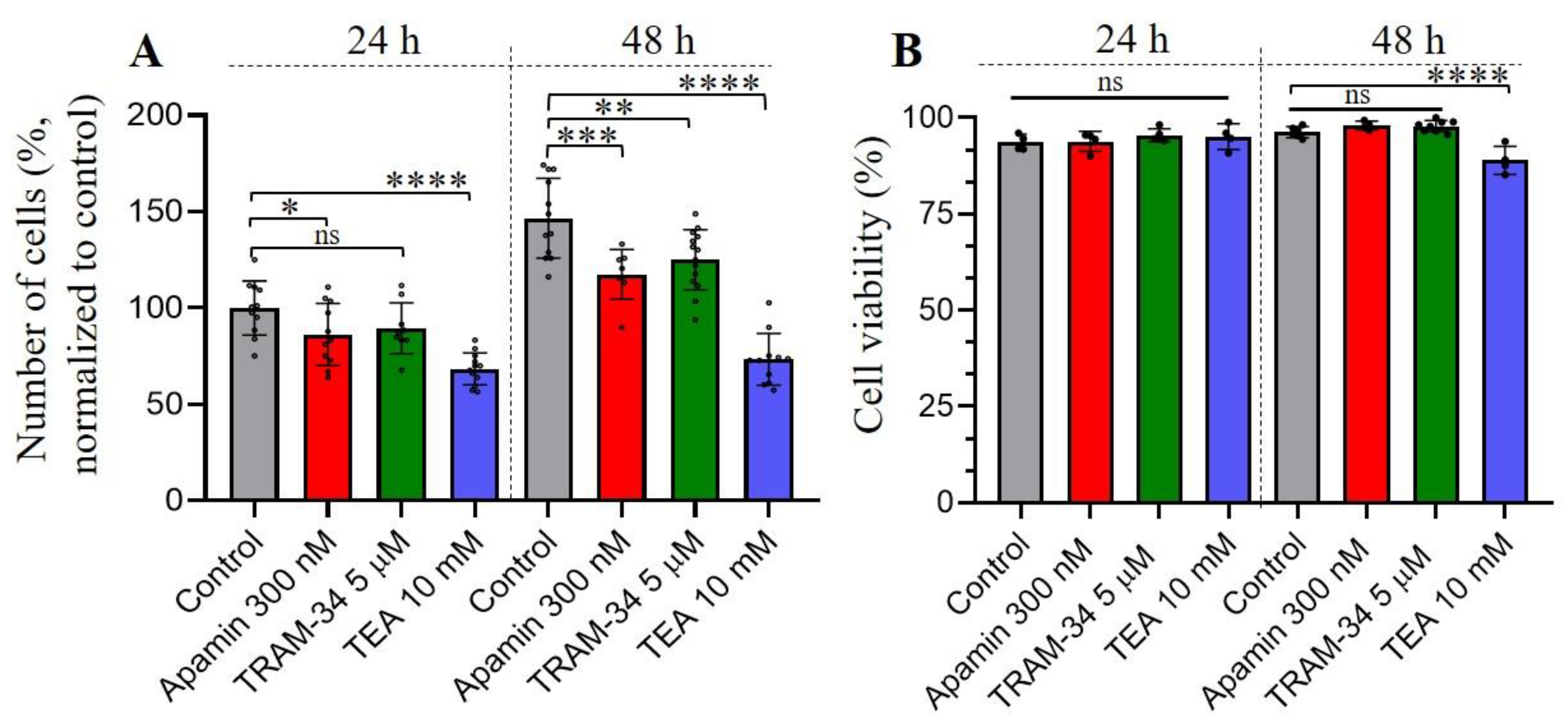

2.3. The effects of selective SK and IK channel inhibitors on cell proliferation and viability

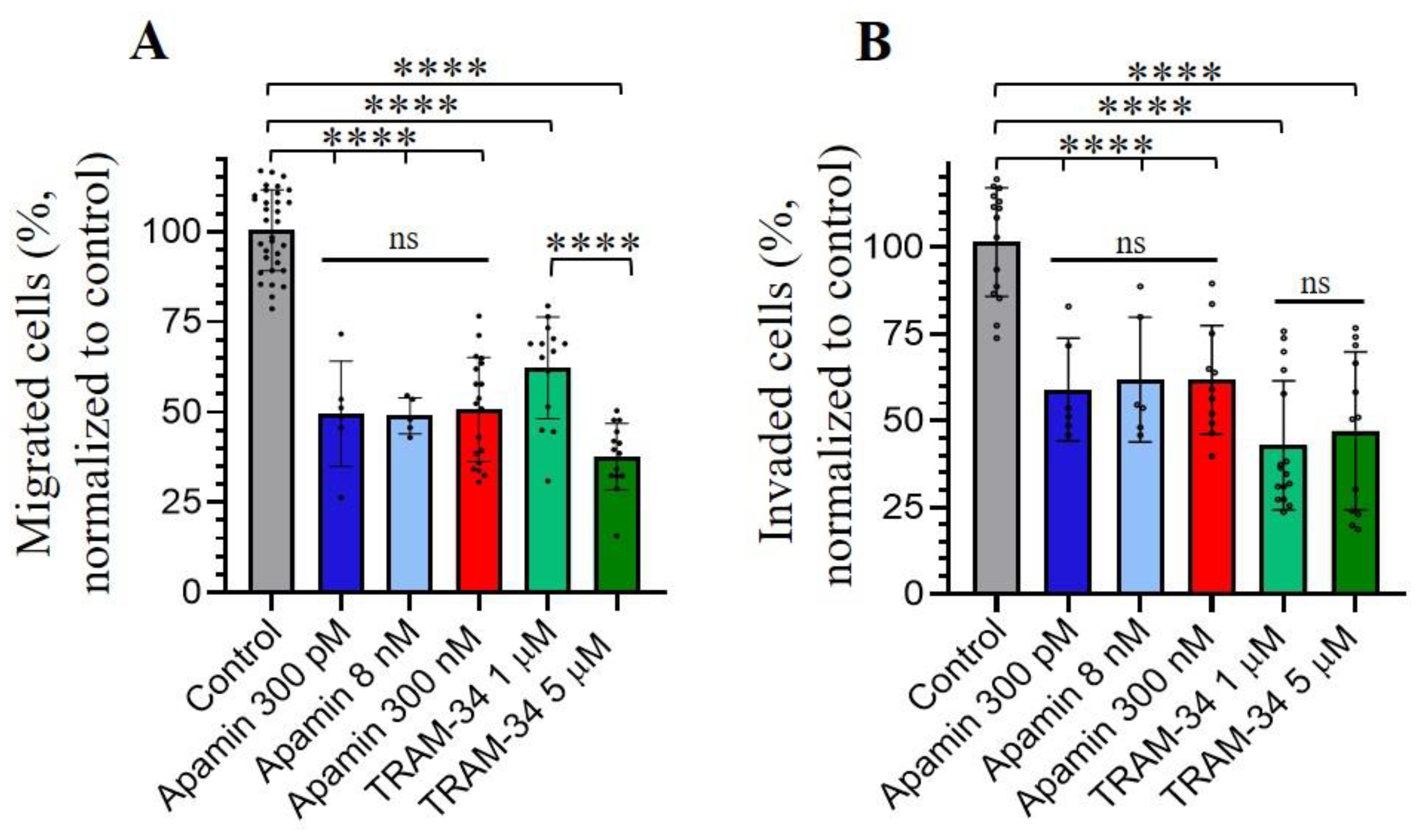

2.4. Role of SK and IK channels in migration and invasion of leukemia cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture and Reagents

4.2. Electrophysiology

4.3. Solutions

4.4. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

4.5. Immunofluorescence

4.6. Cell proliferation and viability assays

4.7. Transwell migration and invasion assays

4.8. Statistics

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arcangeli, A.; Becchetti, A. Novel perspectives in cancer therapy: Targeting ion channels. Drug Resist Updat 2015, 21-22, 11-9. [CrossRef]

- Rafieemehr, H.; Samimi, A.; Maleki Behzad, M.; Ghanavat, M.; Shahrabi, S. Altered expression and functional role of ion channels in leukemia: bench to bedside. Clin Transl Oncol 2020, 22(3), 283-293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, M.; Hirschberg, B.; Bond, C.T.; Kinzie, J.M.; Marrion, N.V.; Maylie, J.; Adelman, J.P. Small-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channels from mammalian brain. Science 1996, 273(5282), 1709-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedarzani, P.; Stocker., M. Molecular and cellular basis of small- and intermediate-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channel function in the brain. Cell Mol Life Sci 2008, 65, 3196-3217. [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.M.; Shim, H.; Christophersen, P.; Wulff, H. Pharmacology of Small- and Intermediate-Conductance Calcium-Activated Potassium Channels. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2020, 60, 219-240. [CrossRef]

- Kuzmenkov, A.I.; Peigneur, S.; Nasburg, J.A.; Mineev, K.S.; Nikolaev, M.V.; Pinheiro-Junior, E.L.; Arseniev, A.S.; Wulff, H.; Tytgat, J.; Vassilevski, A.A. Apamin structure and pharmacology revisited. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 977440. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, J.J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Mongin, A.A.; Hough, L.B. TRAM-34, a putatively selective blocker of intermediate-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channels, inhibits cytochrome P450 activity. PLoS One 2013, 8(5), e63028. [CrossRef]

- Wulff, H.; Kolski-Andreaco, A.; Sankaranarayanan, A.; Sabatier, J.M.; Shakkottai, V. Modulators of small- and intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels and their therapeutic indications. Curr Med Chem 2007, 14(13), 1437-57. [CrossRef]

- Gardos, G. The function of calcium in the potassium permeability of human erythrocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1958, 30(3), 653-4. [CrossRef]

- Fanger, C.M.; Rauer, H.; Neben, A.L.; Miller, M.J.; Rauer, H.; Wulff, H.; Rosa, J.C.; Ganellin, C.R.; Chandy, K.G.; Cahalan, M.D. Calcium-activated potassium channels sustain calcium signaling in T lymphocytes. Selective blockers and manipulated channel expression levels. J Biol Chem 2001, 276(15), 12249-56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feske, S.; Skolnik, E.Y.; Prakriya, M. Ion channels and transporters in lymphocyte function and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2012, 12(7), 532-47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle-Reyes, S.; Valencia-Cruz, G.; Liñan-Rico, L.; Pottosin, I.; Dobrovinskaya, O. Differential Activity of Voltage- and Ca2+-Dependent Potassium Channels in Leukemic T Cell Lines: Jurkat Cells Represent an Exceptional Case. Front Physiol 2018, 9, 499. [CrossRef]

- Kaestner, L.; Bogdanova, A.; Egee, S. Calcium Channels and Calcium-Regulated Channels in Human Red Blood Cells. Adv Exp Med Biol 2020, 1131, 625-648. [CrossRef]

- Fermo, E.; Bogdanova, A.; Petkova-Kirova, P.; Zaninoni, A.; Marcello, A.P.; Makhro, A.; Hänggi, P.; Hertz, L.; Danielczok, J.; Vercellati, C.; Mirra, N.; Zanella, A.; Cortelezzi, A.; Barcellini, W.; Kaestner, L.; Bianchi, P. 'Gardos Channelopathy': a variant of hereditary Stomatocytosis with complex molecular regulation. Sci Rep 2017, 7(1), 1744. [CrossRef]

- Dyrda, A.; Cytlak, U.; Ciuraszkiewicz, A.; Lipinska, A.; Cueff, A.; Bouyer, G.; Egée, S.; Bennekou, P.; Lew, V.L.; Thomas, S.L. Local membrane deformations activate Ca2+-dependent K+ and anionic currents in intact human red blood cells. PLoS One 2010, 5(2), e9447. [CrossRef]

- Cahalan, S.M.; Lukacs, V.; Ranade, S.S.; Chien, S.; Bandell, M.; Patapoutian, A. Piezo1 links mechanical forces to red blood cell volume. Elife 2015, 4, e07370. [CrossRef]

- Staruschenko, A.V.; Vedernikova, E.A. Mechanosensitive cation channels in human leukaemia cells: calcium permeation and blocking effect. J Physiol 2002, 541(Pt 1), 81-90. [CrossRef]

- Staruschenko, A.; Negulyaev, Y.A.; Morachevskaya, E.A. Actin cytoskeleton disassembly affects conductive properties of stretch-activated cation channels in leukaemia cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 2005, 1669(1), 53-60. [CrossRef]

- Chubinskiy-Nadezhdin, V.I.; Negulyaev, Y.A.; Morachevskaya, E.A. Cholesterol depletion-induced inhibition of stretch-activated channels is mediated via actin rearrangement. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2011, 412(1), 80-5. [CrossRef]

- Chubinskiy-Nadezhdin, V.I.; Negulyaev, Y.A.; Morachevskaya, E.A. Functional Coupling of Ion Channels in the Process of Mechano-Dependent Activation in the Membrane of K562 Cells. Cell Tiss. Biol 2019, 13, 470–477. [CrossRef]

- Guéguinou, M.; Chantôme, A.; Fromont, G.; Bougnoux, P.; Vandier, C.; Potier-Cartereau, M. KCa and Ca(2+) channels: the complex thought. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014, 1843(10), 2322-33. [CrossRef]

- Weatherall, K.L.; Seutin, V.; Liégeois, J.F.; Marrion, N.V. Crucial role of a shared extracellular loop in apamin sensitivity and maintenance of pore shape of small-conductance calcium-activated potassium (SK) channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108(45), 18494-9. [CrossRef]

- Lamy, C.; Goodchild, S.J.; Weatherall, K.L.; Jane, D.E.; Liégeois, J.F.; Seutin, V.; Marrion, N.V. Allosteric block of KCa2 channels by apamin. J Biol Chem 2010, 285(35), 27067-27077. [CrossRef]

- Wulff, H.; Gutman, G.A.; Cahalan, M.D.; Chandy, K.G. Delineation of the clotrimazole/TRAM-34 binding site on the intermediate conductance calcium-activated potassium channel, IKCa1. J Biol Chem 2001, 276(34), 32040-5. [CrossRef]

- Maylie, J.; Bond, C.T.; Herson, P.S.; Lee, W.S.; Adelman, J.P. Small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels and calmodulin. J Physiol 2004, 554(Pt 2), 255-61. [CrossRef]

- Qi, M.M.; Qian, L.L.; Wang, R.X. Modulation of SK Channels: Insight Into Therapeutics of Atrial Fibrillation. Heart Lung Circ 2021, 30(8),1130-1139. [CrossRef]

- Bong, A.H.L.; Monteith, G.R. Calcium signaling and the therapeutic targeting of cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2018, 1865(11 Pt B), 1786-1794. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Lian, W.; Zhao, L. Calcium signaling in cancer progression and therapy. FEBS J 2021, 288(21), 6187-6205. [CrossRef]

- Khodakhah, K.; Melishchuk, A.; Armstrong, C.M. Killing K channels with TEA+. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997, 94(24), 13335-8. [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.M.; Fakler, B.; Rivard, A.; Wayman, G.; Johnson-Pais, T.; Keen, J.E.; Ishii, T.; Hirschberg, B.; Bond, C.T.; Lutsenko, S.; Maylie, J.; Adelman, J.P. Mechanism of calcium gating in small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Nature 1998, 395(6701), 503-7. [CrossRef]

- Joiner, W.J.; Wang, L.Y.; Tang, M.D.; Kaczmarek, L.K. hSK4, a member of a novel subfamily of calcium-activated potassium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997, 94(20), 11013-8. [CrossRef]

- Strassmaier, T.; Bond, C.T.; Sailer, C.A.; Knaus, H.G.; Maylie, J.; Adelman, J.P. A novel isoform of SK2 assembles with other SK subunits in mouse brain. J Biol Chem 2005, 280(22), 21231-6. [CrossRef]

- Girault, A.; Haelters, J.P.; Potier-Cartereau, M.; Chantôme, A.; Jaffrés, P.A.; Bougnoux, P.; Joulin, V.; Vandier, C. Targeting SKCa channels in cancer: potential new therapeutic approaches. Curr Med Chem 2012, 19(5),697-713. [CrossRef]

- Weaver, A.K.; Bomben, V.C.; Sontheimer, H. Expression and function of calcium-activated potassium channels in human glioma cells. Glia 2006, 54(3), 223-33. [CrossRef]

- Checchetto, V.; Teardo, E.; Carraretto, L.; Leanza, L.; Szabo, I. Physiology of intracellular potassium channels: A unifying role as mediators of counterion fluxes? Biochimica et biophysica acta 2016, 1857(8), 1258–1266. [CrossRef]

- Capera, J.; Serrano-Novillo, C.; Navarro-Pérez, M.; Cassinelli, S.; Felipe, A. The Potassium Channel Odyssey: Mechanisms of Traffic and Membrane Arrangement. International journal of molecular sciences 2019, 20(3), 734. [CrossRef]

- Lallet-Daher, H.; Roudbaraki, M.; Bavencoffe, A.; Mariot, P.; Gackière, F.; Bidaux, G.; Urbain, R.; Gosset, P.; Delcourt, P.; Fleurisse, L.; Slomianny, C.; Dewailly, E.; Mauroy, B.; Bonnal, J.L.; Skryma, R.; Prevarskaya, N. Intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels (IKCa1) regulate human prostate cancer cell proliferation through a close control of calcium entry. Oncogene 2009, 28(15), 1792-806. [CrossRef]

- Bonito, B.; Sauter, D.R.; Schwab, A.; Djamgoz, M.B.; Novak, I. KCa3.1 (IK) modulates pancreatic cancer cell migration, invasion and proliferation: anomalous effects on TRAM-34. Pflugers Arch 2016, 468(11-12), 1865-1875. [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.; Chen, S.; Wu, H.; Guan, Y.; Liu, L.; Zeng, Y.; Zhao, H.; Jiang, J.; Chu, Z. PRL-3 promotes the proliferation of LoVo cells via the upregulation of KCNN4 channels. Oncol Rep 2011, 26(4), 909-17. [CrossRef]

- Bulk, E.; Ay, A.S.; Hammadi, M.; Ouadid-Ahidouch, H.; Schelhaas, S.; Hascher, A.; Rohde, C.; Thoennissen, N.H.; Wiewrodt, R.; Schmidt, E.; Marra, A.; Hillejan, L.; Jacobs, A.H.; Klein, H.U.; Dugas, M.; Berdel, W.E.; Müller-Tidow, C.; Schwab, A. Epigenetic dysregulation of KCa 3.1 channels induces poor prognosis in lung cancer. Int J Cancer 2015, 137(6), 1306-17. [CrossRef]

- Mohr, C.J.; Steudel, F.A.; Gross, D.; Ruth, P.; Lo, W.Y.; Hoppe, R.; Schroth, W.; Brauch, H.; Huber, S.M.; Lukowski, R. Cancer-Associated Intermediate Conductance Ca2+-Activated K⁺ Channel KCa3.1. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11(1), 109. [CrossRef]

- Millership, J.E.; Devor, D.C.; Hamilton, K.L.; Balut, C.M.; Bruce, J.I.; Fearon, I.M. Calcium-activated K+ channels increase cell proliferation independent of K+ conductance. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2011, 300(4), C792-802. [CrossRef]

- Potier, M.; Joulin, V.; Roger, S.; Besson, P.; Jourdan, M.L.; Leguennec, J.Y.; Bougnoux, P.; Vandier, C. Identification of SK3 channel as a new mediator of breast cancer cell migration. Mol Cancer Ther 2006, 5(11), 2946-53. [CrossRef]

- Steinestel, K.; Eder, S.; Ehinger, K.; Schneider, J.; Genze, F.; Winkler, E.; Wardelmann, E.; Schrader, A.J.; Steinestel, J. The small conductance calcium-activated potassium channel 3 (SK3) is a molecular target for Edelfosine to reduce the invasive potential of urothelial carcinoma cells. Tumour Biol 2016, 37(5), 6275-83. Erratum in: Tumour Biol 2016, 37(2), 2773. [CrossRef]

- Tajima, N.; Schönherr, K.; Niedling, S.; Kaatz, M.; Kanno, H.; Schönherr, R.; Heinemann, S.H. Ca2+-activated K+ channels in human melanoma cells are up-regulated by hypoxia involving hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and the von Hippel-Lindau protein. J Physiol 2006, 571(Pt 2), 349-59. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Huang, Q.Y.; Huang, H.Q. The evidence of HeLa cell apoptosis induced with tetraethylammonium using proteomics and various analytical methods. J Biol Chem 2014, 289(4), 2217-29. [CrossRef]

- Erdem Kış, E.; Tiftik, R.N.; Al Hennawi, K.; Ün, İ. The role of potassium channels in the proliferation and migration of endometrial adenocarcinoma HEC1-A cells. Mol Biol Rep 2022, 49(8), 7447-7454. [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.B.; Zhao, S.G.; Liu, Y.H.; Hu, E.X.; Liu, B.X. Tetraethylammonium inhibits glioma cells via increasing production of intracellular reactive oxygen species. Chemotherapy 2009, 55(5), 372-80. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.B.; Wang, F.; Yao, W.X.; Liu, Y.Q.; Wang, G.; Ma, D. Inhibitory effects of tetraethylammonium on proliferation and voltage-gated potassium channels in human cervical carcinoma cell line SiHa. Ai Zheng 2006, 25(4), 451-5. Chinese.

- Roach, K. M.; Bradding, P. Ca2+ signalling in fibroblasts and the therapeutic potential of KCa3.1 channel blockers in fibrotic diseases. British journal of pharmacology 2020,177(5), 1003–1024. [CrossRef]

- Wojtulewski, J. A.; Gow, P. J.; Walter, J.; Grahame, R.; Gibson, T.; Panayi, G. S.; Mason, J. Clotrimazole in rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases 1980, 39(5), 469–472. [CrossRef]

- Brugnara, C.; Gee, B.; Armsby, C. C.; Kurth, S.; Sakamoto, M.; Rifai, N.; Alper, S. L.; Platt, O. S. Therapy with oral clotrimazole induces inhibition of the Gardos channel and reduction of erythrocyte dehydration in patients with sickle cell disease. The Journal of clinical investigation 1996, 97(5), 1227–1234. [CrossRef]

- Ataga, K. I.; Smith, W. R.; De Castro, L. M.; Swerdlow, P.; Saunthararajah, Y.; Castro, O.; Vichinsky, E.; Kutlar, A.; Orringer, E. P.; Rigdon, G. C.; Stocker, J. W. ICA-17043-05 Investigators. Efficacy and safety of the Gardos channel blocker, senicapoc (ICA-17043), in patients with sickle cell anemia. Blood 2008,111(8), 3991–3997. [CrossRef]

- Wulff, H.; Miller, M. J.; Hansel, W.; Grissmer, S.; Cahalan, M. D.; Chandy, K. G. Design of a potent and selective inhibitor of the intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel, IKCa1: a potential immunosuppressant. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2000, 97(14), 8151–8156. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zhang, L.; Shi, Y.; Yi, H.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, J.; Pollock, C. A.; Chen, X. M. The KCa3.1 blocker TRAM34 reverses renal damage in a mouse model of established diabetic nephropathy. PloS one 2018, 13(2), e0192800. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. J.; Raman, G.; Bodendiek, S.; O'Donnell, M. E.; Wulff, H. The KCa3.1 blocker TRAM-34 reduces infarction and neurological deficit in a rat model of ischemia/reperfusion stroke. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 2011, 31(12), 2363–2374. [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Han, S. M.; Park, K. K. Therapeutic Effects of Apamin as a Bee Venom Component for Non-Neoplastic Disease. Toxins 2020, 12(3), 195. [CrossRef]

| Gene (KCa type) |

Forward primer Reverse primer |

Predicted product size, bp |

|---|---|---|

|

hKCNN1 (KCa2.1, SK1) |

3’-AGA ACA GCA AGA CAT ATC CG-5’ 5’-ATT GTA GCT GTG GCT GTT CA-3’ |

282 |

|

hKCNN2 (KCa2.2, SK2) |

3’-CTT ATC AGT CTC TCC ACG ATC-5’ 5’-TAC AGT TCC TGG GCA TAT AG-3’ |

423 |

|

hKCNN3 (KCa2.3, SK3) |

3’-CGA CTG AGT GAC TAT GCT C-5’ 5’-GTG GAC AGA CTG ATA AGG C-3’ |

137 |

|

hKCNN4 (KCa3.1, IK) |

5’-ATC ATG AAG TTG TGC ACG TG-3’ 5’-ATC ATG AAG TTG TGC ACG TG-3’ |

325 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).