1. Introduction

Fibrosis is a pathological condition characterized by an expansion of connective tissue that compromises the integrity of the affected organ [

1,

2]. The cause of cutaneous fibrosis can be trauma. It may appear at the site of burn or frostbite due to the developing inflammatory response. Scarring is one of the complications associated with skin fibrosis [

3,

4]. To date, several animal models of fibrosis are available to explore the histological features of the scarred tissue and the associated changes in gene expression. Obtaining the experimental model of bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis requires several consequent injections of mice skin with bleomycin [

5,

6]. In this case, the injections continue regularly until the desired pathological changes become evident. Then, there is a need to wait until the inflammatory process subsides and fibrosis occurs to perform the necessary experimental procedures. Upon completion of the experimental protocol, the researchers evaluate the expected therapeutic effects and clarify the role of selected genes in the pathological process using histological methods and the data on gene expression in the collected samples.

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are directly involved in the pathogenesis of fibrosis. They contribute to the tissue remodeling. MMPs are also responsible for changes in the composition of the extracellular matrix. In addition, MMPs secreted by immune cells facilitates their migration to sites of damage to degrade damaged cells and biomolecules. The recovery of scarred tissue also accompanies by significant changes in the activity of proteolytic enzymes, including MMPs [

7,

8]. These make MMPs valuable disease biomarkers and prove their relevance for experimental studies. This paper aimed to evaluate changes in the expression of MMP genes:

Mmp2,

Mmp3, and

Mmp9 caused by laser therapy in the experimental model of bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Lab animals

The study involved 21 female Balb/c mice (7-8 w.o.) with a weight ranging from 20 to 30 g. Mice were housed at 21–23°C on 14-hour light cycles since day 1. The air humidity was between 50 and 65%. Mice received a balanced diet. They also had unlimited access to drinking water. The quarantine lasted for two weeks. Before the experiment, the mice were anesthetized. Before sampling the skin, the animals received a lethal dose of anesthetic.

For the experiment, the animals were divided into three groups (7 mice per group). The first group of animals received injections of 100 µl of saline (0.9% sodium chloride) intradermally. The second and third groups received injections of 0.1 U bleomycin in 100 µl of saline. The injections continued every odd day for 19 days in the interscapular region of the back. On the 30th day of the experiment, animals of the third group were irradiated with a SmartXide DOT® CO2 laser (DEKA, Italy). The dose of irradiation was 18.2 J/cm2. The laser was preset to discrete mode. Skin samples were collected 48 hours after the last injection or irradiation. Samples designated to real-time PCR were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C. Samples designated for histology were fixed in 10% formalin and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H+E) following a standard protocol. The thickness of the skin and the epidermis were measured using ImageJ freeware (NIH, USA).

2.2. Purification of total RNA

Total RNA was isolated using the TRIZOL reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer. The quality of the preparations was verified by electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose gel in non-denaturing conditions. The RNA concentration was assessed by a fluorometric method using the commercial Qubit RNA BR Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer.

2.3. Real-time PCR

Before the experiment, total RNA was converted to complementary DNA (cDNA) using the MMLV RT reagent kit (Evrogen, Russia). DNA amplification was performed on Real-time DT prime 5M1 instrument (DNA-Technology, Russia) with primers taken from the NCBI Probe database (NCBI Probe, 2015) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturers. The raw data were normalized to the expression level of the housekeeping gene (18S RNA) and processed using a built-in computer program distributed by the manufacturers. Each sample served as input to prepare three sets of three probes that would be enough to repeat the experiment three times.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The results were presented as mean value ± standard error (m ± SE). The comparison of two independent means was performed using a one-way ANOVA. The differences between the means were considered significant if the probability of accepting the null hypothesis did not exceed 0.05.

4. Discussion

In this study, we examined the skin samples of animals treated with the SmartXide DOT® (DEKA) CO2 laser (group 3) and animals of two control groups. Animals of group 1 received neither injections of bleomycin nor the following treatment with laser therapy. Animals of group 2 received injections of bleomycin but did not receive laser therapy. We also analyzed changes in the expression of MMPs, namely Mmp2, Mmp3, and Mmp9, in all three groups of mice.

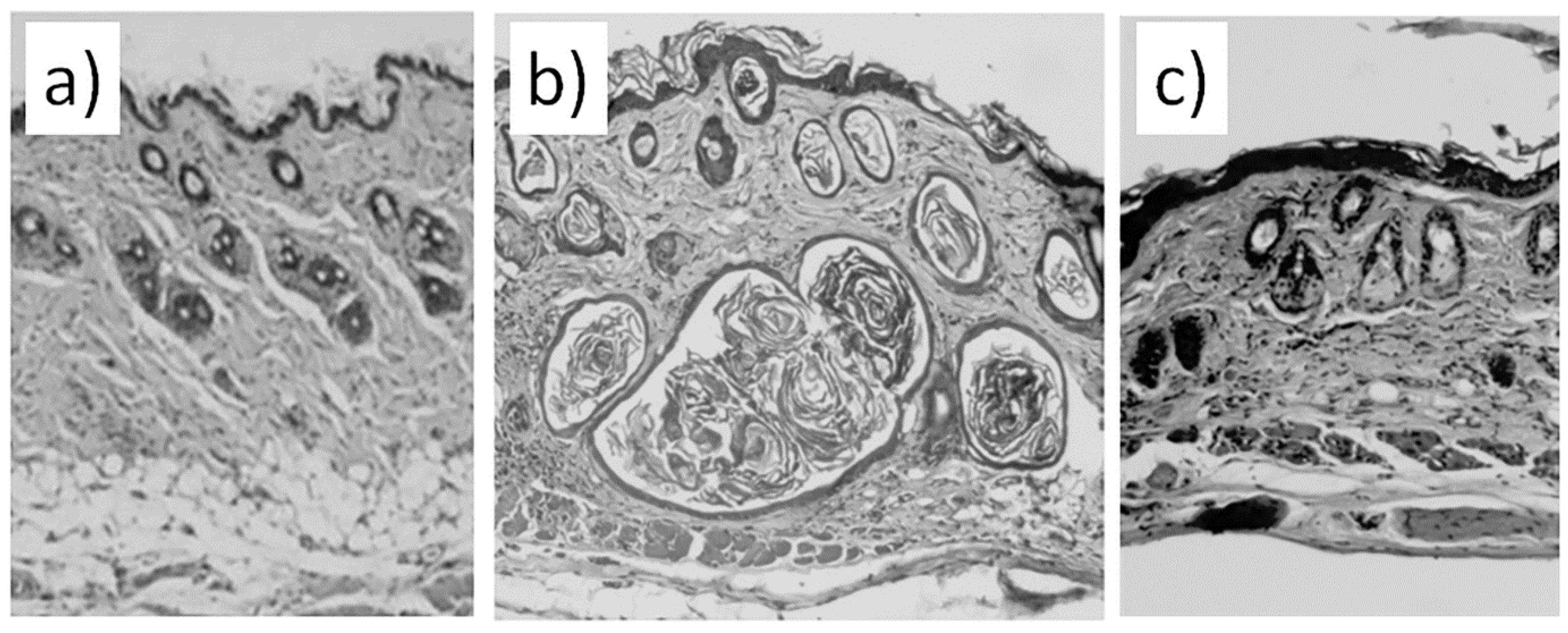

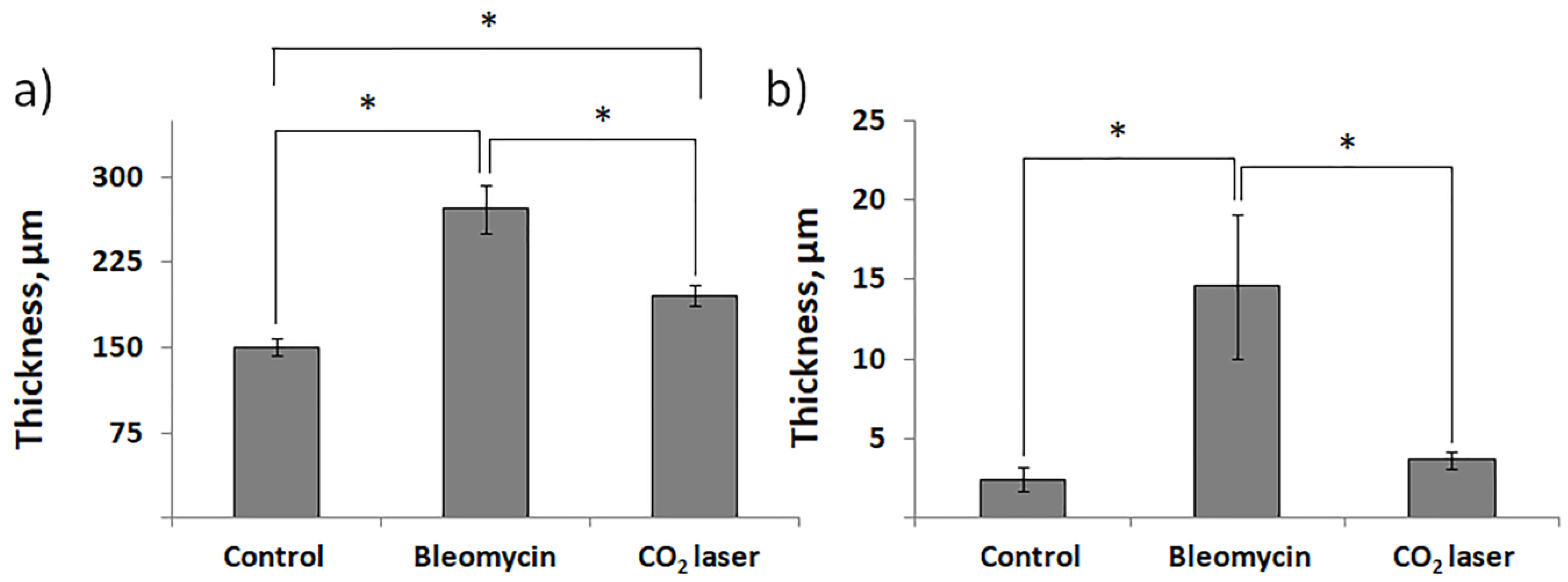

The results of the histological analysis revealed that we successfully established the experimental model of bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis. We report that the skin of animals injected with bleomycin is significantly thicker than the skin of sham control animals (comp. groups 2 and 1) and exhibits evident signs of epidermal hyperplasia (

Figure 2a and b). The dermis contains multiple bundles of misarranged collagen fibers (

Figure 1b). Subcutaneous fat partially replaced the connective tissue. In addition, the skin lost most of the appendages.

We also show the efficiency of laser therapy in the treatment of scars. We report that the thickness of the skin after laser therapy becomes comparable to sham control (

Figure 2a). Comparable thicknesses of the epidermis between group 3 and group 2 indicate on cessation of hyperplasia (

Figure 2b). The irradiated dermis (group 3) also contains less fibrotic foci than dermis of non-irradiated bleomycin-treated mice (group 2).

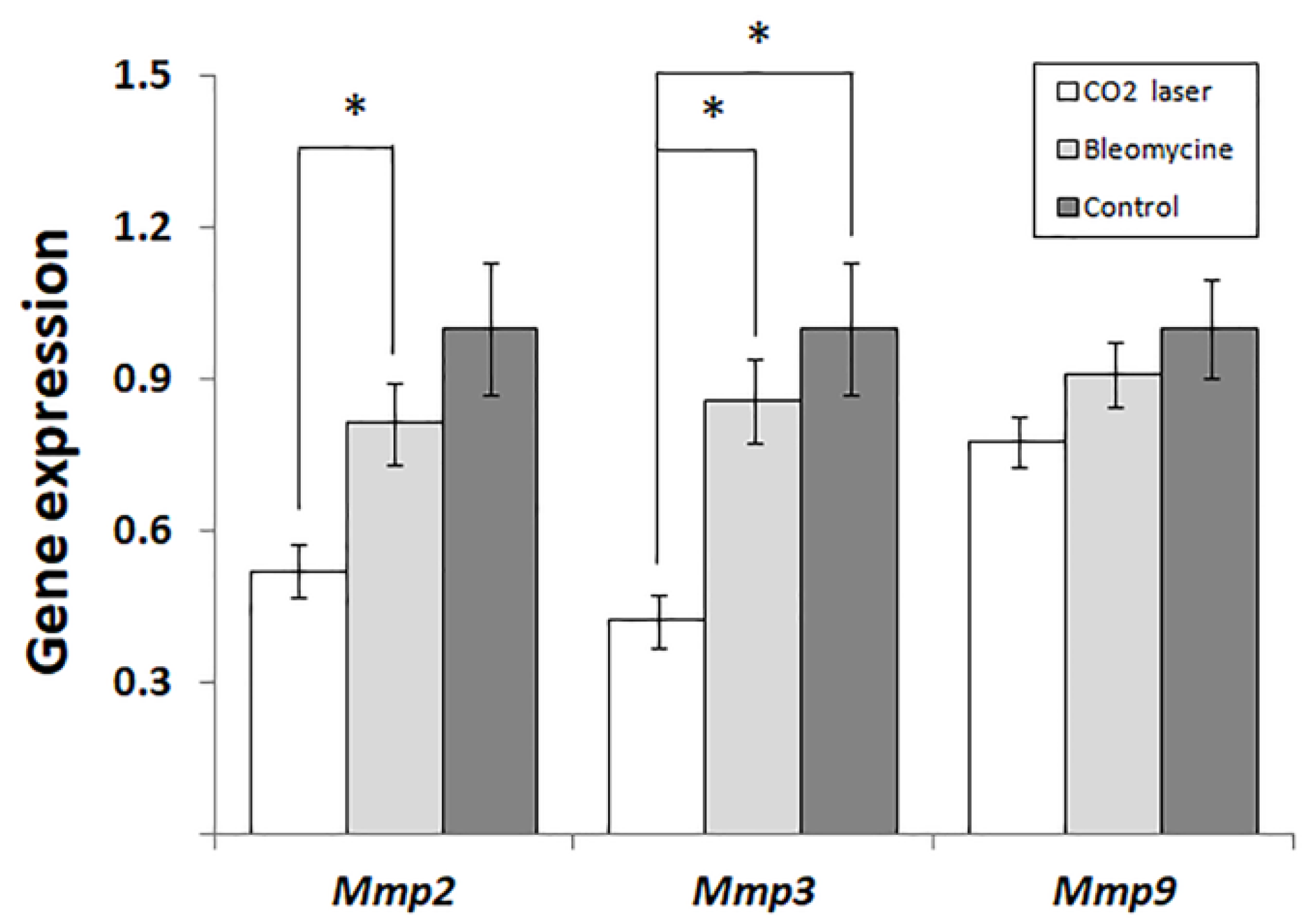

The analysis of gene expression (

Figure 3) indicates that laser therapy of bleomycin-injected mice (group 3) significantly reduces the expression of

Mmp2 and -

3 compared to the other groups of mice. Earlier, Matuszczak et al. [

9] reported that the therapy with an ablative fractional CO

2 laser decreased the plasma level of MMP2 in human patients with hypertrophic burn scars. At the same time, the therapy improved texture, color, and function and alleviate pruritus in the affected areas. Furthermore, in vitro experiments performed by Lee et al. [

10] discovered that wound healing in the presence of adipocyte-derived stem cell-containing medium supplemented with niacinamide suppressed the expression of

MMP although significantly improved skin texture and pigmentation.

Chung et al. [

11] reported that the treatment of pigs with ablative and non-ablative fractional lasers (AFL and NAFL, respectively) significantly changed the expression of Mmp2 and Mmp9. In ELISA experiments, the authors showed that the level of Mmp2 significantly increased after low- and high-energy NAFL compared to sham control and AFL. In turn, the differences between the sham control and AFL, according to the authors, were insignificant. In qPCR experiments, Chung et al. [

11] did not see significant differences between groups treated with AFL and any group treated with NAFL. Contrarily, the expression of

Mmp2 in ALF-treated animals significantly exceeded one in sham control. In this regard, we hypothesize that the observed changes between the two groups of animals treated with NAFL likely reflected a progressive increase in

Mmp2 expression. In our study (

Figure 3), we show significant suppression of

Mmp2 at the early stages of post-therapeutic recovery. Respectively, the following increase in the expression of

Mmp2 would explain the absence of statistical differences in Chung’s qPCR experiments [

11] and the accumulation of secreted

Mmp2 detectable by ELISA. The same hypothesis can explain higher levels of

Mmp2 in animals treated with low and high-energy NAFL.

In 48h after the therapy, the expression of

Mmp3 significantly decreases, similar to

Mmp2 (

Figure 3). As found earlier, stromelysin 1, encoded by

Mmp3, contributes to the degradation of collagens, elastin, laminins, and other extracellular proteins [

12]. In addition, stromelysin 1 activates several matrix metalloproteinases: namely interstitial collagenase/ MMP1, matrilysin/ MMP7, and gelatinase B/ MMP9, which are necessary for the degradation of proteins located in the dermal extracellular matrix [

13]. Our data are along with similar results obtained by others. For instance, Amann et al. reported that treatment of human three-dimensional (3D) organotypic skin models with fractional erbium glass laser decreased the expression of MMP3 for five days after the therapy [

14].

In our experiments, the expression of Mmp9 follows the same trend as two other MMPs (

Figure 3). However, the changes between groups 2 and 3 are not statistically significant (

p = 0.065). The data from other authors [

7] suggest that the expression of Mmp9 after laser therapy normalizes faster than the expression of Mmp3. For instance, the expression of MMP9 increased on day 5 in Amman’s qPCR experiments, although it was insignificantly different from the control on day 3 [

14].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.V.V. and K.I.M., methodology: S.V.V., software: M.A.V., validation: K.I.M., formal analysis: S.A.G., M.J.A., and M.A.V., investigation: K.M.M., resources: R.O.I., data curation: D.E.D. and Z.O.V., writing—original draft preparation: M.A.V. writing—review and editing: M.A.V. and K.I.M., visualization: M.J.A. Supervision: S.V.V. and K.I.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.