Submitted:

23 January 2023

Posted:

27 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results.

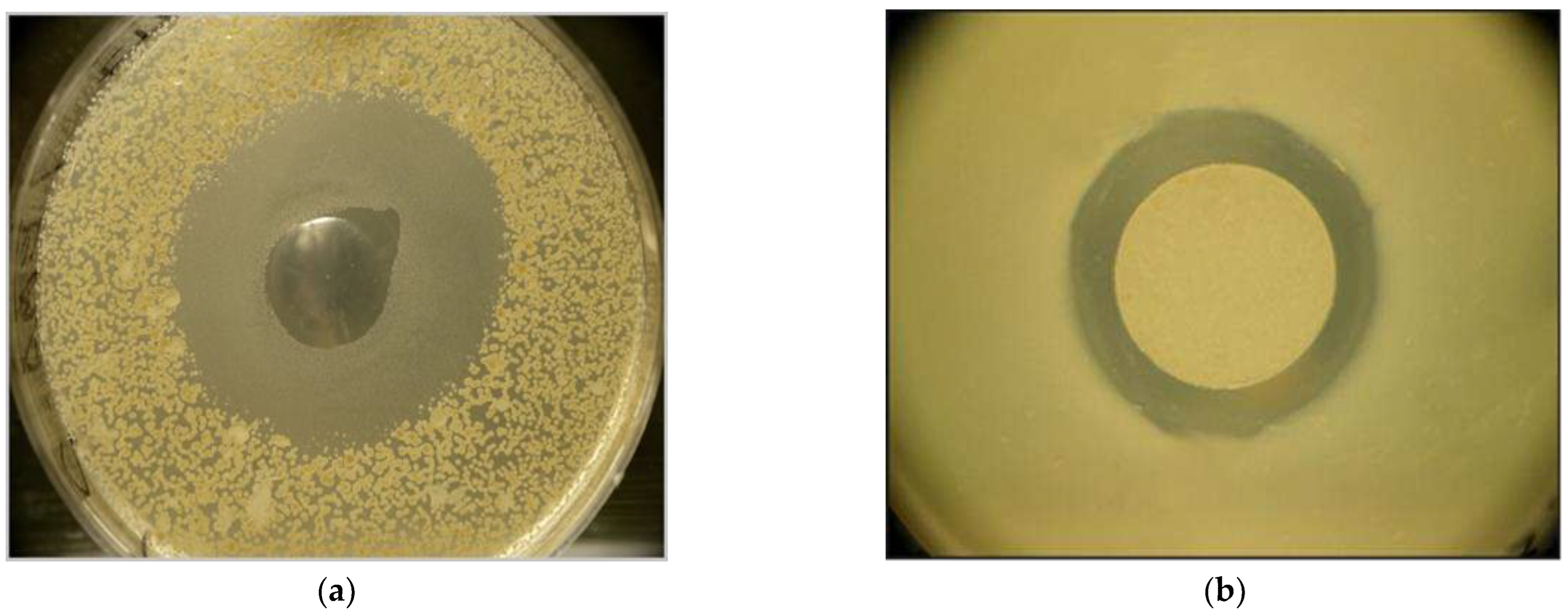

2.1. ANticlostridial Activity Of Ema And Emc In VitrO

2.2. In Vitro Bioassays: Cytopathogenic Effects Of Cell-Free Condition Media (Cfcm) Of 3 Epb Species On Lmh Chicken Cell Monolayer

2.2.1. Experiment-1 aimed at comparing the cytopathogenic effects of 4 different undiluted CFCMs obtained from cultures of EMA, EMC, and TT01 yellow, and TT01 red colony color variants, respectively, (see Materials and Methods).

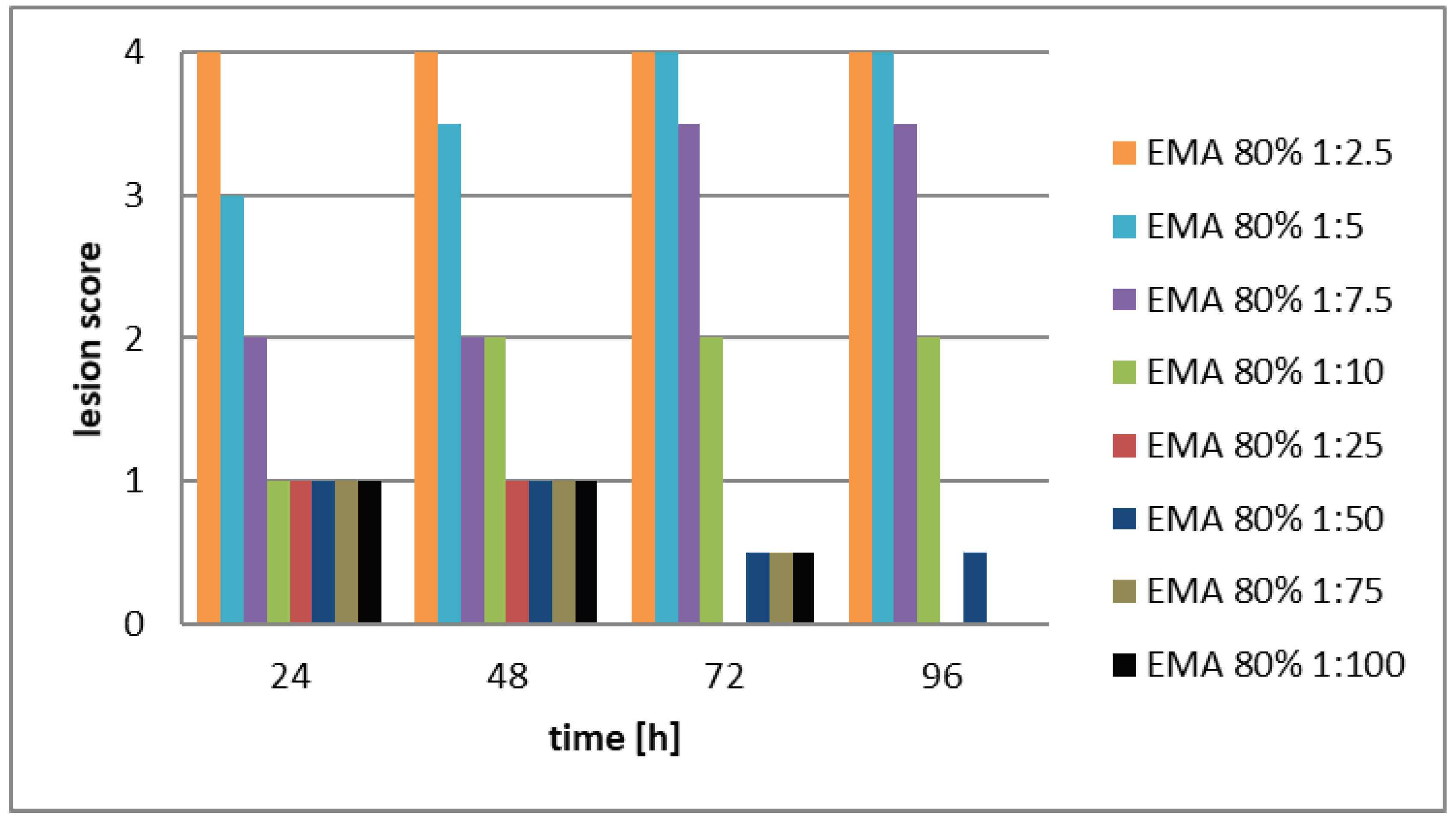

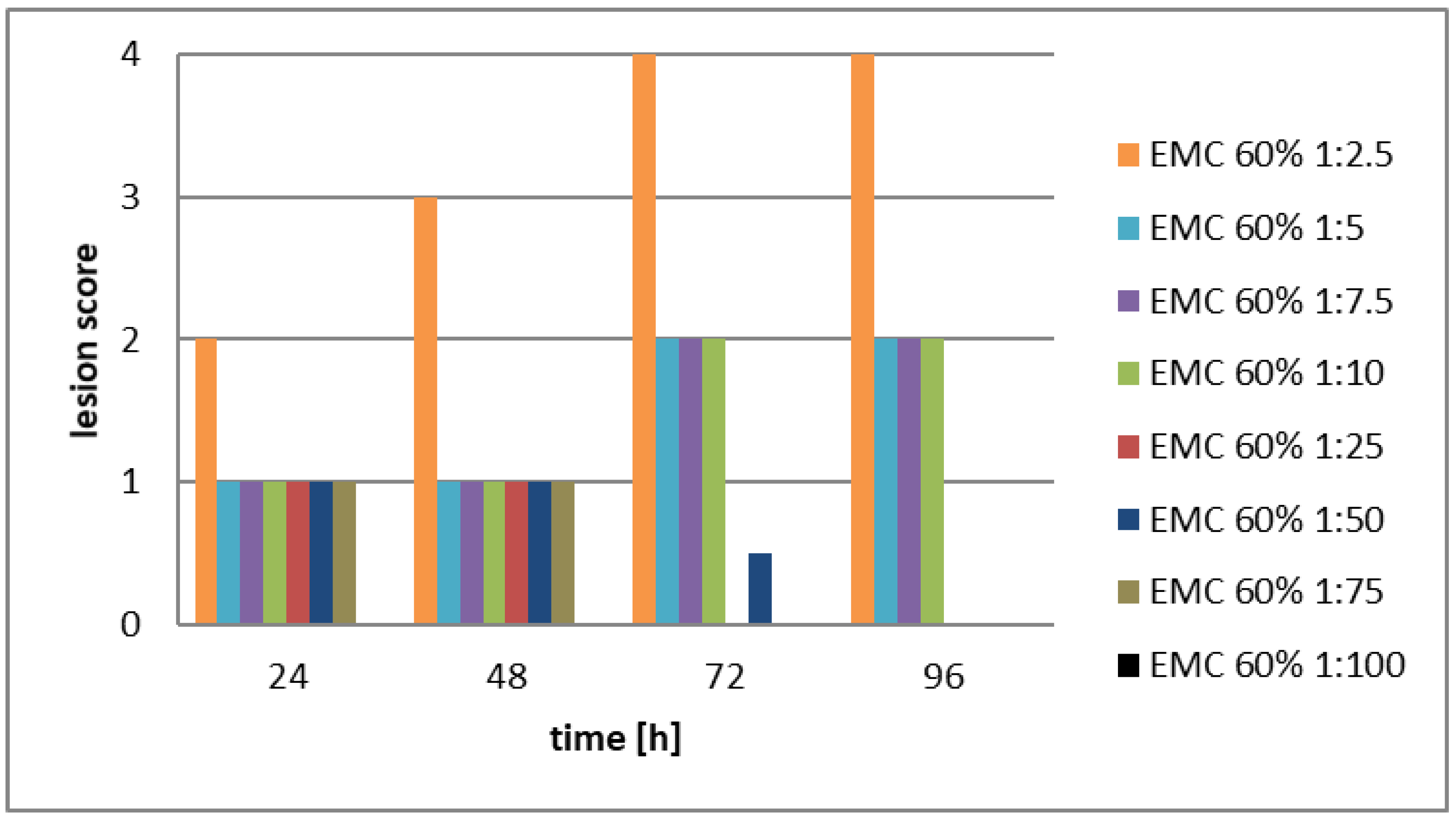

2.2.2. Experiment-2 aimed at comparing the cytopathogenic effects of serial dilutions of the CFCM filtrates of EMA, and EMC cultures, considering that both the both EMA and EMC CFCMs showed much stronger antimicrobial activity than the two TT01 CFCM. The stock solutions, (and serial dilutions of them) used in this experiment were: EMA 60%, and EMC 80%, respectively. Confluent monolayer from LMH cells was developed again in Medium RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin G (200 IU/ml), and streptomycin (200 µg/ml) for 72 hours in a controlled atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C and around 85-90% humidity in 25 cm2 Falcon flasks with filtered caps (see also in Materials, and Methods). The same score system [44] (Amin, 2012, see Table S1) was used for evaluating the results.

2.3. Results Of The In Vivo Xenofood-Feeding Experiment

2.3.1 Gastrointestinal activity of XENOFOOD

2.3.2. Growth rate, feed consumption and the post-mortal data

3. Discussion.

4. Material, and Method

- Anti-clostridial potential of EPB CFCM: The respective methods have been published in [39]. Briefly, Clostridium perfringens NCAIM 1417 strain was obtained from the National Collection of Agricultural and Industrial Microorganisms – WIPO (of Hungary, Faculty of Food Sciences, Szent István University Somlói út 14-16 1118 Budapest, Hungary). Clostridium perfringens LH1-LH8; LH11-LH16; LH19, and LH20 are of chicken origin, and LH24 came from a pig; each has been deposited in the (frozen) stock collection of the Department of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, University of Veterinary Medicine Budapest, Hungary. Xenorhabdus strains, X. budapestensis DSM 16342(T) (Lengyel) (EMA), and X. szentirmaii DSM 16338 (T) (Lengyel)(EMC) [34,35]. of EMA and EMC CFCM bioassays were tested on different Gram-positive strains including Clostridium perfringens strains were carried out as described before, [35,36,37,38,39].

- .In vitro experiments: Cell-free conditioned culture media (CFCM), of antibiotic-producing bacteria, were tested, and LHM (tissue culture) cells were in two different experiments.

- Experiment 1: Testing cytotoxicity of different EPB CFCM on confluent LMH (leghorn male hepatoma, LMH) cell line [42]: Developing Confluent layers of LMH (leghorn male hepatoma, LMH) cell line [42]: (LMH; ATCC Number: CRL-2117™) were developed culture Falcon flasks in Medium RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen/GIBCO), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum FBS (Invitrogen/GIBCO), penicillin G (200 IU/ml) and streptomycin (200 µg/ml), respectively.

- In detail, cells were inoculated into 25 cm (2) flasks with filtered caps (Sarstedt) containing an end volume of 7 ml culture and incubated in a controlled atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C and around 85-90% humidity. After 72 hours of incubation, a confluent monolayer of LMH cells was obtained per flask.

- Altogether 18 Falcon tubes, - each containing 9 ml Medium 199 with Earle’s Salts, L-glutamine, 25 mM HEPES and L-amino acids (Invitrogen/GIBCO) and supplemented with 15% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum FBS (Invitrogen/GIBCO) and 0.22% rice starch were used, 2x3 controls and 4X3 experimental tubes.

- Preparation of CFCMs: Tubes with thw same media (except fo for streptomicine, were inoculated with 4 different bacterial strains, EMA, EMC, TT01 yellow or TT01 red, representing 2 Xenorhabdus, (X. budapestensis nov. DSM16342(T), Lengyel) (EMA), [34,35], and X. szentirmaii nov. DSM16338 (T) (Lengyel) (EMC, [34,35], and 1 Photorhabdus (P. luminescens ssp. akhurstii TT01, [71] species. The latter is obtained from the Boemare laboratory (Montpellier, France). TT01 yellow and TT01 red names were used for two colony-color variants segregating spontaneously in McConkey agar plates, (P. Ganas, unpublished). (Xenorabdus, and Photorhabdus are penicillin resistant species).

- These antibiotic-producing bacteria were freshly taken from frozen cultures and grown on the bacterial species grown on MacConkey agar plates before they were transferred to the liquid medium as described before, [35,36,37,38,39,40]. The bacterial species were grown on MacConkey agar plates before they were transferred to the liquid medium, and unexpectedly two different types of colonies for TT01 were observed on the agar plates: red-brown colored colonies which adsorbed the neutral red from the MacConkey agar and yellow-colored colonies which did not so. Both types of colonies were tested for the effect of cell-free filtrates on LMH monolayers. In this particular experiment, the antibiotic-producing bacteria were cultured at 28 oC. The bacteria were incubated for 65 hours at 30 °C in a shaker (225 rpm. Bacterial cultures were then centrifuged at 3,300xg for 5 min and then the supernatants from the cultures were filtered through 0.22 µm cellulose acetate filters (Millipore).

- Experimental design: From all but 3 of the Falcon flasks (with the 72-hrs old LMH-layers), the culture medium of the LMH monolayers was removed from the flasks and replaced by the 4 CFCMs. Each of the CFCMs was tested in triplicates. There were two sets of controls. There were also 3 flasks with fresh medium (fresh Medium 199 supplemented with 15% FBS) without CFCM, and another 3 with the original, ("unchanged", that is 72h-old) culture media. All these 4X3 experimental and 2X3 control flasks were incubated for another 72hrs. The cultures were incubated in a controlled atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C and around 85-90% humidity.

- In vitro Experiment 2: permanent chicken liver cells (LMH; ATCC Number: CRL-2117™) [42] were grown in Medium RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen/GIBCO) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum FBS (Invitrogen/GIBCO), penicillin G (200 IU/ml) and streptomycin (200 µg/ml).

- Cells were inoculated into 25 cm2 flasks with filtered caps (Sarstedt) containing an end volume of 7 ml culture and incubated in a controlled atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C and around 85-90% humidity.

- After 72 hours of incubation, a confluent monolayer of LMH cells was obtained per flask.

- All but the so-called “Unchanged culture flasks” LMH monolayers, the culture medium of the LMH monolayers was removed from the flasks and replaced by something.

- The control flasks were refilled with fresh media (Medium RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen/GIBCO) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum FBS (Invitrogen/GIBCO), penicillin G (200 IU/ml) and streptomycin (200 µg/ml).

- The experimental flasks were refilled with cell-free (centrifuged and filtered serially diluted stock solutions (EMA: stock solution: 60V/V; EMC stock solution 80V/V%). The dilutions were 1:2.5; 1:5; 1:10 1:.25; 1:.50; 1:75, and 1:100, respectively.

- The EPB cells had been also cultured in Medium RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin G, without streptomycin, (Xenorhabdus are pecicillin resistant).

- Each of the different filtrate analyses and the controls was performed in duplicate.

- The cultures were incubated in a controlled atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C and around 85-90% humidity.

- Each monolayer was investigated visually by an inverted light microscope to detect the effect of the cell-free filtrates on LMH monolayers. According to the degree of monolayer destruction, the following scoring system was established and also published, [44], (See Supplementary Material, Table S1).

- XENOFOOD preparation: XENOFOOD contained 5% soy-meal, which had been suspended with an equal amount (w/w) of EMA and another 5% suspended in an equal amount (w/w) of EMC cells obtained from 5 days-old shaken (2000 rpm) liquid cultures by high-speed (Sorwall; for 30 minutes) centrifugation.

- The liquid cultures were in 2XLB; (DIFCO); supplemented with meat extract equivalent amount to the yeast extract. The 5 days had been proven optimal for antimicrobial substance production at 25 oC in these conditions).

- It had previously been discovered that both EMA and EMC grow and produce antimicrobial substances in autoclaved soy meal containing some water and yeast extract or autoclaved yeast, (in 0.5 w/w %).

- Therefore, the original chicken food served as a semi-solid culture media of Xenorhabdus cells. Both EMA and EMC culturing semi-solid chicken food, which was prepared daily, and have been incubated in sterile conditions for another five days; then the EMA and EMC culturing media were united; autoclaved (20 min, 121 oC), and then dried by heat overnight. The Xenorhabdus cells were killed in such a way, while the heat stabile [36] antimicrobial compounds remained active

- XENOFOOD in vivo feeding experiment:Experimental animals: One-day-old male broiler chickens (N=2x34 = 68) were equally distributed into two groups: Control (C) and Treated (T) groups. The latter was fed with XENOFOOD. The C group was kept on a normal starter (1-10-d) and grower (11-42d) diet according to the standard international protocol.

- Food, feeding, evaluations: The T Group T was kept on “starter (1-10-d) XENOFOOD”, and “grower XENOFOOD” (11-42d). Body weights were measured daily between 1-42 days. Growth and FCR were monitored for 24-d. In the in vivo feeding experiment, we fed 39 birds with XENOFOOD, and there were 39 control birds.

- Body weights were measured daily between 1-42 days. Growth, - and food-conversion rates (GR and FCR respectively, were monitored for every 24-d.

- Dissection, Post mortam data: Not all but a sample (N=2x10=20) of 42-day-old birds were dissected on the 42nd day are presented here. We dissected a sample of 10 birds from the XENOFOOD-fed and a sample of 10 birds from the Control groups. [HM1] [u2] That is, not all but samples (N=2x10) of the 2x34) from 42-day-old birds were dissected to get post-mortam data about a few body organs as well as about the number of Clostridium germs in their ilea. The body weights of these selected animals did not differ from the average of their respective (C, or T) experimental groups. After dissection, the weights of the different organs were measured. The absolute and relative weights of the spleens and the bursae of Fabricii are presented in the Results section.

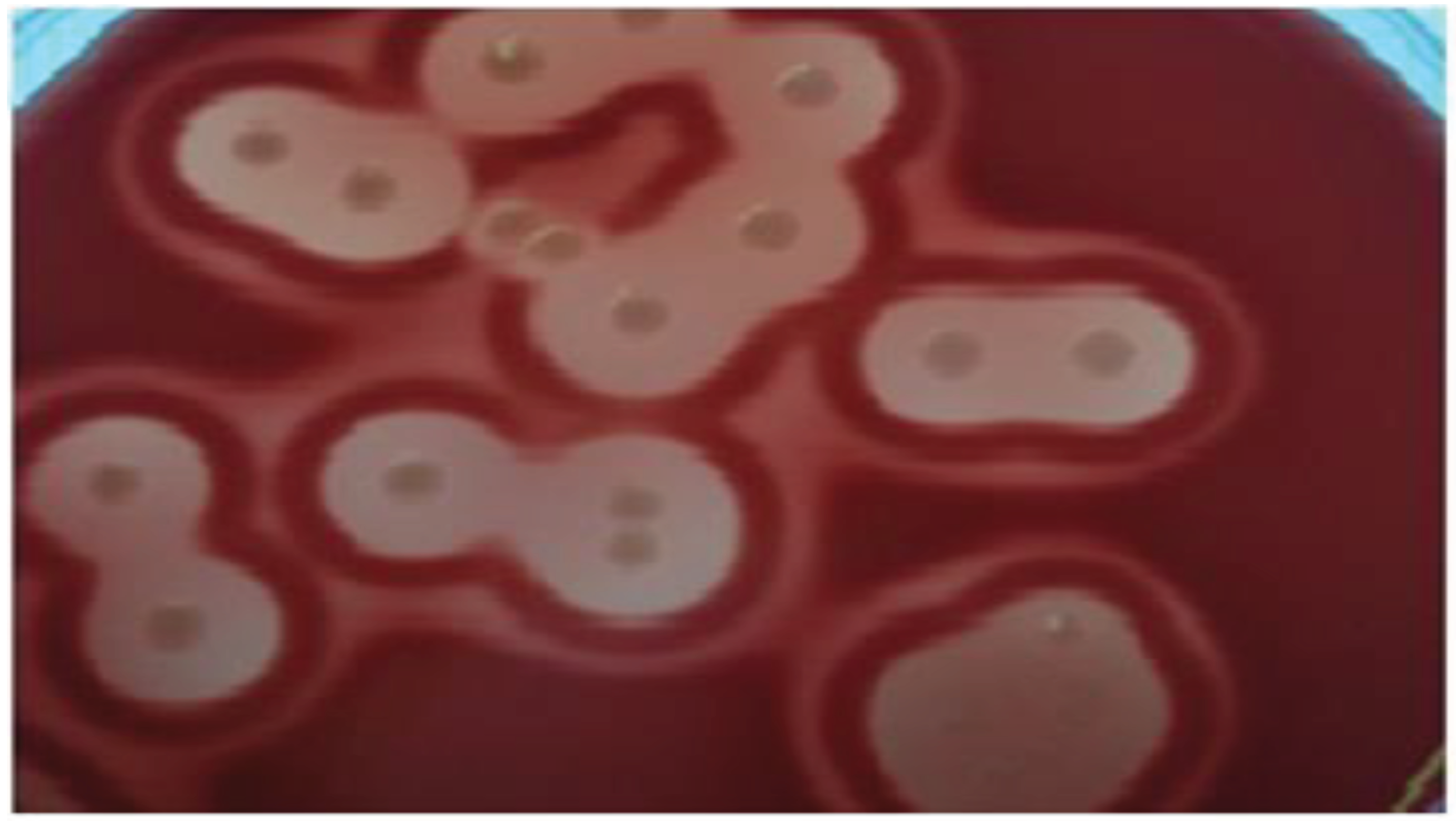

- CFU determination:The content of the lower ileum was washed taken out, diluted, and equilibrated and the colony-forming units were determined on BAM Media M75: Lactose-Gelatin Medium.

- Statistical AnalysisANOVA procedure was carried out by using the respective propositions of the SAS 9.4, see Acknowledgment section Software mostly due to an unbalanced data set. The significant differences (α = 0.05) between treatment means were assessed using the Least Significant Difference (LSD).

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

References

- Huang W, Reyes-Caldas P, Mann M, Seifbarghi S, Kahn A, Almeida RPP, Béven L, Heck M, Hogenhout SA, Coaker G. Bacterial Vector-Borne Plant Diseases: Unanswered Questions and Future Directions. Mol Plant. 2020, 13, 1379–1393. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Białas A, Zess EK, De la Concepcion JC, Franceschetti M, Pennington HG, Yoshida K, Upson JL, Chanclud E, Wu CH, Langner T, Maqbool A, Varden FA, Derevnina L, Belhaj K, Fujisaki K, Saitoh H, Terauchi R, Banfield MJ, Kamoun S. Lessons in Effector and NLR Biology of Plant-Microbe Systems. Mol Plant Microbe 3.Interact. 2018, 31, 34–45. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro Monzon F, Rödel MO, Jeschke JM. Tracking Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis Infection Across the Globe. Ecohealth. 2020, 17, 270–279. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolářová I, Valigurová A. Hide-and-Seek: A Game Played between Parasitic Protists and Their Hosts. Microorganisms. 2021, 9, 2434. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoïz S, Metz S, Derelle E, Reñé A, Garcés E, Bass D, Soudant P, Chambouvet A. Emerging Parasitic Protists: The Case of Perkinsea. Front Microbiol. 2022, 12, 735815. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Preston S, Jabbar A, Gasser RB. A perspective on genomic-guided anthelmintic discovery and repurposing using Haemonchus contortus. Infect Genet Evol. 2016, 40, 368–373. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo Y, Shi Y, Zhang F, Guan F, Zhang J, Feyereisen R, Fabrick JA, Yang Y, Wu Y. Genome mapping coupled with CRISPR gene editing reveals a P450 gene confers avermectin resistance in the beet armyworm. PLoS Genet. 2021, 17, e1009680. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sokól R, Galecki R. The resistance of Eimeria spp. to toltrazuril in black grouse (Lyrurus tetrix) kept in an aviary. Poult Sci. 2018, 97, 4193–4199. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhter MJ, Aziz FB, Hasan MM, Islam R, Parvez MMM, Sarkar S, Meher MM. Comparative effect of papaya (Carica papaya) leaves' extract and Toltrazuril on growth performance, hematological parameter, and protozoal load in Sonali chickens infected by mixed Eimeria spp. J Adv Vet Anim Res. 2021, 8, 91–100. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hawkins NJ, Fraaije BA. Contrasting levels of genetic predictability in the evolution of resistance to major classes of fungicides. Mol Ecol. 2021, 30, 5318–5327. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knutie SA, Wilkinson CL, Kohl KD, Rohr JR. Early-life disruption of amphibian microbiota decreases later-life resistance to parasites. Nat Commun. 2017, 8, 86. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Uddin, T.M.; Chakraborty, A.J.; Khusro, A.; Zidan, B.R.M.; Mitra, S.; Emran, T.B.; Dhama, K.; Ripon, M.K.H.; Gajdács, M.; Sahibzada, M.U.K.; et al. Antibiotic resistance in microbes: History, mechanisms, therapeutic strategies and future prospects. J. Infect. Public Health 2021, 14, 1750–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fodor A, Abate BA, Deák P, Fodor L, Gyenge E, Klein MG, Koncz Z, Muvevi J, Ötvös L, Székely G, Vozik D, Makrai L. Multidrug Resistance (MDR) and Collateral Sensitivity in Bacteria, with Special Attention to Genetic and Evolutionary Aspects and to the Perspectives of Antimicrobial Peptides-A Review. Pathogens. 2020, 9, 522. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ötvös L Jr, Wade JD. Current challenges in peptide-based drug discovery . Front Chem. 2014, 2, 62. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carton J. M., Strohl W. R. (2013). Protein therapeutics (Introduction to biopharmaceuticals), in Biological and Small Molecule Drug Research and Development, eds Ganelin R., Jefferts R., Roberts S. (Waltham, MA: Academic Press; ), 127–159.

- Lázár V, Martins A, Spohn R, Daruka L, Grézal G, Fekete G, Számel M, Jangir PK, Kintses B, Csörgő B, Nyerges Á, Györkei Á, Kincses A, Dér A, Walter FR, Deli MA, Urbán E, Hegedűs Z, Olajos G, Méhi O, Bálint B, Nagy I, Martinek TA, Papp B, Pál C. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria show widespread collateral sensitivity to antimicrobial peptides. Nat Microbiol. 2018, 3, 718–731. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kintses B, Jangir PK, Fekete G, Számel M, Méhi O, Spohn R, Daruka L, Martins A, Hosseinnia A, Gagarinova A, Kim S, Phanse S, Csörgő B, Györkei Á, Ari E, Lázár V, Nagy I, Babu M, Pál C, Papp B. Chemical-genetic profiling reveals limited cross-resistance between antimicrobial peptides with different modes of action. Nat Commun. 2019, 10, 5731. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mojsoska B, Jenssen H Peptides and Peptidomimetics for Antimicrobial Drug Design . Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2015, 8, 366–415. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jenssen H, Hamill P, Hancock RE. Peptide antimicrobial agents. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006, 19, 491–511. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ostorházi E, Hoffmann R, Herth N, Wade JD, Kraus CN, Otvos L Jr. Advantage of a Narrow Spectrum Host Defense (Antimicrobial) Peptide Over a Broad Spectrum Analog in Preclinical Drug Development. Front Chem. 2018, 6, 359. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ostorházi E, Holub MC, Rozgonyi F, Harmos F, Cassone M, Wade JD, Otvos L Jr. Broad-spectrum antimicrobial efficacy of peptide A3-APO in mouse models of multidrug-resistant wound and lung infections cannot be explained by in vitro activity against the pathogens involved. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011, 37, 480–4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ötvös L., Jr. Immunomodulatory effects of anti-microbial peptides. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2016, 63, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petkovic M, Mouritzen MV, Mojsoska B, Jenssen H. Immunomodulatory Properties of Host Defence Peptides in Skin Wound Healing. Biomolecules. 2021, 11, 952. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jenssen, H, Fjell, C. D.; Cherkasov, A.; Hancock, R.E. QSAR modeling and computer-aided design of antimicrobial peptides. J. Pept. Sci. 2008, 14, 110–114.

- Mojsoska B, Zuckermann RN, Jenssen H. Structure-activity relationship study of novel peptoids that mimic the structure of antimicrobial peptides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 4112–20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsakou F, Jersie-Christensen R, Jenssen H, Mojsoska B. The Role of Proteomics in Bacterial Response to Antibiotics. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2020, 13, 214. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ötvös, L., Jr. The short proline-rich antibacterial peptide family. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2002, 59, 1138–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang KP, Reed SG, McGwire BS, Soong L. Leishmania model for microbial virulence: the relevance of parasite multiplication and pathoantigenicity. Acta Trop. 2003, 85, 375–90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGwire BS, Kulkarni MM Interactions of antimicrobial peptides with Leishmania and trypanosomes and their functional role in host parasitism . Exp Parasitol. 2010, 126, 397–405. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni MM, McMaster WR, Kamysz W, McGwire BS. Antimicrobial peptide-induced apoptotic death of leishmania results from calcium-de pendent, caspase-independent mitochondrial toxicity. J Biol Chem. 2009, 284, 15496–504. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhurst, R.J. Antibiotic activity of Xenorhabdus spp. , bac 190 teria symbiotically associated with insect pathogenic nematodes of the families Heterorhabditidae and Steinernematidae. J. Gen.Microbiol. 1982, 128, 3061. [Google Scholar]

- Ogier, J.C. , Pagès, S. ; Frayssinet, M.; Gaudriault, S. Entomopathogenic nematode-associated microbiota: From monoxenic paradigm to pathobiome. Microbiome 2020, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGwire BS, Olson CL, Tack BF, Engman DM. Killing of African trypanosomes byantimicrobial peptides. J Infect Dis. 2003, 188, 146–52. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lengyel, K. , Lang, E. , Fodor, A.; Szállás, E, Schumann, P, Stackebrandt, E. Description of four novel species of Xenorhabdus, family Enterobacteriaceae: Xenorhabdus budapestensis sp. nov., Xenorhabdus ehlersii sp. nov., Xenorhabdus innexi sp. nov., and Xenorhabdus szentirmaii sp. nov. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 28, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fodor A, Gualtieri M, Zeller M, Tarasco E, Klein MG, Fodor AM, Haynes L, Lengyel K, Forst SA, Furgani GM, Karaffa L, Vellai T. Type Strains of Entomopathogenic Nematode-Symbiotic Bacterium Species, Xenorhabdus szentirmaii (EMC) and X. budapestensis (EMA), Are Exceptional Sources of Non-Ribosomal Templated, Large-Target-Spectral, Thermotolerant-Antimicrobial Peptides (by Both), and Iodinin (by EMC). Pathogens. 2022, 11, 342. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Furgani, G, Böszörményi, E. , Fodor, A, Máthé-Fodor, A. Forst, S, Hogan, J.S., Katona, Z, Klein, M.G.; Stackebrandt, E.; Szentirmai, A. et al. Xenorhabdus antibiotics: A comparative analysis and potential utility for controlling mastitis caused by bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 104, 745–758. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böszörményi E, Érsek T, Fodor A, Fodor AM, Földes LS, Hevesi M, Hogan JS, Katona Z, Klein MG, Kormány A, Pekár S, Szentirmai A, Sztaricskai F, Taylor RA. Isolation and activity of Xenorhabdus antimicrobial compounds against the plant pathogens Erwinia amylovora and Phytophthora nicotianae. J Appl Microbiol. 2009, 107, 746–59. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vozik, D, Bélafi-Bakó, K, Hevesi, M, Böszöményi, E. , Fodor, A. Effectiveness of a peptide-rich fraction from Xenorhabdus budapestensis culture against fire blight disease on apple blossoms. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobo 2015, 43, 547–553. [CrossRef]

- Fodor, A, Makrai L, Fodor L, Venekei, I, Pál, L, Husvéth, F, Molnár, A, Dublecz, K, Pintér, Cs, Józsa, S, Klein, MG. Anti-Coccidiosis Potential of Autoclaveable Antimicrobial Peptides from Xenorhabdus budapestensis Resistant to Proteolytic (Pepsin, Trypsin) Digestion Based on In vitro Studies. Microbiology Research Journal International, Page 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Fodor, A; Varga, I. ; Hevesi, M; Máthé-Fodor, A, Racsko, J, Eds.; Hogan, J.A. Novel anti-microbial peptides of Xenorhabdus origin against multidrug resistant plant pathogens. In: V. Bobbarala (Ed.) A Search for Antibacterial Agents. London, United Kingdom, IntechOpen, 2012 [Online]. pp. 3–32. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/books/2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, E, Heinrich, AK, Hirschmann, M, Abebew, D, Shi, YN Vo, T. D.; Wesche, F.; Shi, Y.M.; Grün, P.; Simonyi, S.; et al. Promoter activation in Δhfq mutants as an efficient tool for specialized metabolite production enabling direct bioactivity testing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2019, 58, 18957–18963. [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi T, Nomura K, Hirayama Y, Kitagawa T. Establishment and characterization of a chicken hepatocellular carcinoma cell line, LMH. Cancer Res. 1987, 47, 4460–4. [PubMed]

- Böszörményi E. Barcs, I., Domján, Gy., Bakó, K., Fodor, A., Makrai, L., Vozik, D. [Xenorhabdus budapestensis entomopathogenic bacteria cell free conditioned medium and purified peptide fraction effect on some zoonotic bacteria]. Orvosi Hetilap, Volume/Issue: Volume 156: Issue 44. https://doi.org/. 2018. In Hungarian. Brachmann AO, Forst S, Furgani GM, Fodor A, Bode HB. Xenofuranones A and B: phenylpyruvate dimers from Xenorhabdus szentirmaii. J Nat Prod. 2006, 69, 1830–2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin A, Bilic I, Berger E, Hess M. Trichomonas gallinae, in comparison to Tetratrichomonas gallinarum, induces distinctive cytopathogenic effects in tissue cultures. Vet Parasitol. 2012, 186, 196–206. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brachmann AO, Forst S, Furgani GM, Fodor A, Bode HB. Xenofuranones A and B: phenylpyruvate dimers from Xenorhabdus szentirmaii. J Nat Prod. 2006, 69, 1830–2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualtieri M, Banéres-Roquet F, Villain-Guillot P, Pugnière M, Leonetti JP. The antibiotics in the chemical space. Curr Med Chem. 2009, 3, 390–393. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualtieri, M, Villain-Guillot, P, Givaudan, A,Pages, S. Nemaucin, an Antibiotic Produced by Entomopathogenic Xenorhabdus cabanillasii. A Patent WO2012085177A1, 28 June 2012, France.

- Fuchs SW, Sachs CC, Kegler C, Nollmann FI, Karas M, Bode HB. Neutral loss fragmentation pattern-based screening for arginine-rich natural products in Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus. Anal Chem. 2012, 84, 6948–55. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs SW, Grundmann F, Kurz M, Kaiser M, Bode HB. Fabclavines: bioactive peptide-polyketide-polyamine hybrids from Xenorhabdus. Chembiochem. 2014, 15, 512–6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenski SL, Kolbert D, Grammbitter GLC, Bode HB. Fabclavine biosynthesis in X. szentirmaii: shortened derivatives and characterization of the thioester reductase FclG and the condensation domain-like protein FclL. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019, 46, 565–572. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenski SL, Cimen H, Berghaus N, Fuchs SW, Hazir S, Bode HB. Fabclavine diversity in Xenorhabdus bacteria. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2020, 16, 956–965. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Houard J, Aumelas A, Noël T, Pages S, Givaudan A, Fitton-Ouhabi V, Villain-Guillot P, Gualtieri M. Cabanillasin, a new antifungal metabolite, produced by entomopathogenic Xenorhabdus cabanillasii JM26. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 2013, 66, 617–20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreyer J, Rautenbach M, Booysen E, van Staden AD, Deane SM, Dicks LMT. Xenorhabdus khoisanae SB10 produces Lys-rich PAX lipopeptides and a Xenocoumacin in its antimicrobial complex. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 132. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gualtieri M, Aumelas A, Thaler JO. Identification of a new antimicrobial lysine-rich cyclolipopeptide family from Xenorhabdus nematophila. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 2009, 62, 295–302. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs SW, Proschak A, Jaskolla TW, Karas M, Bode HB. Structure elucidation and biosynthesis of lysine-rich cyclic peptides in Xenorhabdus nematophila. Org Biomol Chem. 2011, 9, 3130–2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaacson PJ, Webster JM Antimicrobial activity of Xenorhabdus sp. RIO (Enterobacteriaceae), symbiont of the entomopathogenic nematode, Steinernema riobrave (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae) . J Invertebr Pathol. 2002, 79, 146–53. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantel L, Florin T, Dobosz-Bartoszek M, Racine E, Sarciaux M, Serri M, Houard J, Campagne JM, de Figureueiredo RM, Midrier C, Gaudriault S, Givaudan A, Lanois A, Forst S, Aumelas A, Cotteaux-Lautard C, Bolla JM, Vingsbo Lundberg C, Huseby DL, Hughes D, Villain-Guillot P, Mankin AS, Polikanov YS, Gualtieri M. Odilorhabdins, Antibacterial Agents that Cause Miscoding by Binding at a New Ribosomal Site. Mol Cell. 2018, 70, 83–94. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarciaux M, Pantel L, Midrier C, Serri M, Gerber C, Marcia de Figureueiredo R, Campagne JM, Villain-Guillot P, Gualtieri M, Racine E. Total Synthesis and Structure-Activity Relationships Study of Odilorhabdins, a New Class of Peptides Showing Potent Antibacterial Activity. J Med Chem. 2018, 61, 7814–7826. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racine E, Gualtieri M. From Worms to Drug Candidate: The Story of Odilorhabdins, a New Class of Antimicrobial Agents. Front Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2893. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lanois-Nouri A, Pantel L, Fu J, Houard J, Ogier JC, Polikanov YS, Racine E, Wang H, Gaudriault S, Givaudan A, Gualtieri M. The Odilorhabdin Antibiotic Biosynthetic Cluster and Acetyltransferase Self-Resistance Locus Are Niche and Species Specific. mBio. 2022, 13, e0282621. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Meng, F.; Qiu, D.; Yang, X. Two novel antimicrobial peptides purified from the symbiotic bacteria Xenorhabdus budapestensis NMC-10. Peptides 2012, 35, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reimer D, Nollmann FI, Schultz K, Kaiser M, Bode HB. Xenortide Biosynthesis by Entomopathogenic Xenorhabdus nematophila. J Nat Prod. 2014, 77, 1976–80. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmati N, Maddirala AR, Hussein N, Amawi H, Tiwari AK, Andreana PR. Efficient syntheses and anti-cancer activity of xenortides A-D including ent/epi-stereoisomers. Org Biomol Chem. 2018, 16, 5332–5342. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reimer D, Cowles KN, Proschak A, Nollmann FI, Dowling AJ, Kaiser M, ffrench-Constant R, Goodrich-Blair H, Bode HB. Rhabdopeptides as insect-specific virulence factors from entomopathogenic bacteria. Chembiochem. 2013, 14, 1991–7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi Y, Gao C, Yu Z. Rhabdopeptides from Xenorhabdus budapestensis SN84 and Their Nematicidal Activities against Meloidogyne incognita. J Agric Food Chem. 2018, 66, 3833–3839. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi X, Lu X, Zhang X, Bi Y, Li X, Yu Z. Two novel cyclic depsipeptides Xenematides F and G from the entomopathogenic bacterium Xenorhabdus budapestensis. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 2019, 72, 736–743. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Kaiser, M.; Bode, H.B. Rhabdopeptide/Xenortide-like peptides from Xenorhabdus innexi with terminal amines showing potent antiprotozoal activity. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 5116–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohlendorf B, Simon S, Wiese J, Imhoff JF. Szentiamide, an N-formylated cyclic depsipeptide from Xenorhabdus szentirmaii DSM 16338T. Nat Prod Commun. 2011, 6, 1247–50. [PubMed]

- Nollmann FI, Dowling A, Kaiser M, Deckmann K, Grösch S, ffrench-Constant R, Bode HB. Synthesis of szentiamide, a depsipeptide from entomopathogenic Xenorhabdus szentirmaii with activity against Plasmodium falciparum. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2012, 8, 528–33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualtieri M, Ogier JC, Pagès S, Givaudan A, Gaudriault S. Draft Genome Sequence and Annotation of the Entomopathogenic Bacterium Xenorhabdus szentirmaii Strain DSM16338. Genome Announc. 2014, 2, e00190–14. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Duchaud E, Rusniok C, Frangeul L, Buchrieser C, Givaudan A, Taourit S, Bocs S, Boursaux-Eude C, Chandler M, Charles JF, Dassa E, Derose R, Derzelle S, Freyssinet G, Gaudriault S, Médigue C, Lanois A, Powell K, Siguier P, Vincent R, Wingate V, Zouine M, Glaser P, Boemare N, Danchin A, Kunst F. The genome sequence of the entomopathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens. Nat Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 1307–13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Samples | Replicates | 24h | 48h |

|---|---|---|---|

|

M199 the original (unchanged) culture Media, in which LMH layer had been developed |

A | 0 | 0 |

| B | 0 | 0 | |

| C | 0 | 0 | |

| Fresh (199 + 15% + PKS) culture media added | A | 0 | 0 |

| A | |||

| B | 0 | 0 | |

| C | 0 | 0 | |

|

EMA CFCM (EMA had been cultured inM199) |

A | 3 | 4 |

| B | 3 | 4 | |

| C | 3 | 4 | |

|

EMC CFCM (EMC had been cultured inM199) |

A | 4 | 4 |

| B | 4 | 4 | |

| C | 4 | 4 | |

|

TT01 YELLOW CFCM (TT01 had been cultured inM199) |

A | 4 | 4 |

| B | 4 | 4 | |

| C | 4 | 4 | |

|

TT01 RED CFCM TT01 had been cultured inM199) |

A | 4 | 4 |

| B | 4 | 4 | |

| C | 4 | 4 |

| TREATMENTS | SPLEEN | bursa of Fabricius | CLOSTRIDIUM CFU | |||||

| weight | weight | size | individual bursa/spleen | (lower ileum) | ||||

| N | mg | mg | mm | ratio | ||||

| C (Control) | 10 | 2266.6 | 2761.0 | 25.2 | 1.39 | 149.9 | ||

| T (Xenofood-fed) | 10 | 1618.0 | 3618.2 | 26.9 | 2.38 | 48.1 | ||

| t | +2.09 | +3.16 | 3.02 | 3.7 | -2.128733 | |||

| P | 0.056 | 0.006 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.028 | |||

| Significance | NS | ** | ** | * | * | |||

| TREATMENTS | N | DAYS OF THE EXPERIMENT | ||

| 10 | 14 | 42 | ||

| C (Control) | 34 | 252.9 +/- 33.4 | 1196.8 +/- 123 | 2842.5 +/- 184 |

| T (XENOFOOD-fed) | 34 | 271.3 +/- 39.4 | 1132.7+/- 162 | 2984.2+/- 207 |

| T-value | -177 | 187 | - 1.02 | |

| P-value | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.32 | |

| Significance | ns | ns | ns | |

| TREATMENTS | N | GROWTH PERIODS (DAYS) | ||

| 1-10 | 11-24 | 1-24 | ||

| C (Control) | 34 | 1.06 | 1.68 | 1.53 |

| T (XENOFOOD-fed) | 34 | 0.97 | 1.71 | 1.52 |

| Significance | ns | ns | ns | |

| Natural NR-AMPs | Xenorhabus specoes | refeence |

|---|---|---|

| Xenofuranone A and B | X. szetirmaii (EMC) DSM(16338)T | [45] Brachmann, et al., 2006 |

| Nemaucin | X. cabanillasii | [46] Gualtieri, et al., 2009)a,[47] Gualtieri, et al., 2012 |

| Fabclavine | X. budapestensis DSM16342)T (EMA) | [48] (Fuchs et al., 2012 |

| Fabclavine, A, B | X. szentirmaii DSM(16338)T (EMC) | [49] (Fuchs et al., 2014) |

| Fabclavine, biosynthetic intermediers, derivatives, and analogs |

X. szentirmaii DSM(16338)T (EMC) All but e few Xenorhabdus |

[50] Wenski et al., 2019. [51] Wenski et al., 2020 |

|

Cabanillasin |

X. cabanillasii, X. khoisanae, SB10 |

[52] Houard et al., 2013, |

| PAX peptides | X. nematophila | [54] Gualtieri et al, 2009b |

| [55] Fuchs et al, 2011), | ||

| X. khoisanae, SB10 | [53] Dreyer, et al., 2019 | |

| Odilorhabdins | X. riobrave | [56] Isaacson and Webster, 2013 |

| [57] Pantel, et al, 2018 | ||

| [58] Sarciaux et al., 2018 | ||

| [69] Racine, and Gualtieri 2019 | ||

| [60] Lanois-Nouri, et al., 2022. | ||

| Anti-oomycete peptides |

X. budapestensis NMC-10 |

[61] (Xiao et al., 2012) |

|

Xenortide |

X. nematophila |

[62] (Reimer, 2014 |

|

Xenortide A-D |

X. nematophila |

[63] Esmati, et al., 2018 |

| Rhabdopeptide | X. nematophila | [64] Reimer at al., 2013 |

| Rhabdopeptide (with nematicide activity) | X. budapestensis SN84 | [65] (Bi et l., 2018) |

| Rhabdoopeptide/xenortide-like peptides | Xenorhabdus innexi | [66] Zhao, 2018 |

| New cyclic depsipeptide xenematide F, and G, (anti-oomycete activity) | X. budapestensis SN84 | [67] (Xi et al, 2019 |

| Szentiamide |

X. szentirmaii DSM16338T (EMC) |

[68] Ohlendorf, et al., 2011) |

| [69] (Nollmann, et al, 2012) | ||

| Genomic information: 71 NR-AMP operons in. | X. szetirmaii (EMC)T DSM16338 | [70] Gualtieri et al.,2014 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).