Submitted:

24 January 2023

Posted:

26 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Oscillating Bearings in Wind Turbines

Wear in oscillating bearings

2. Materials and Methods

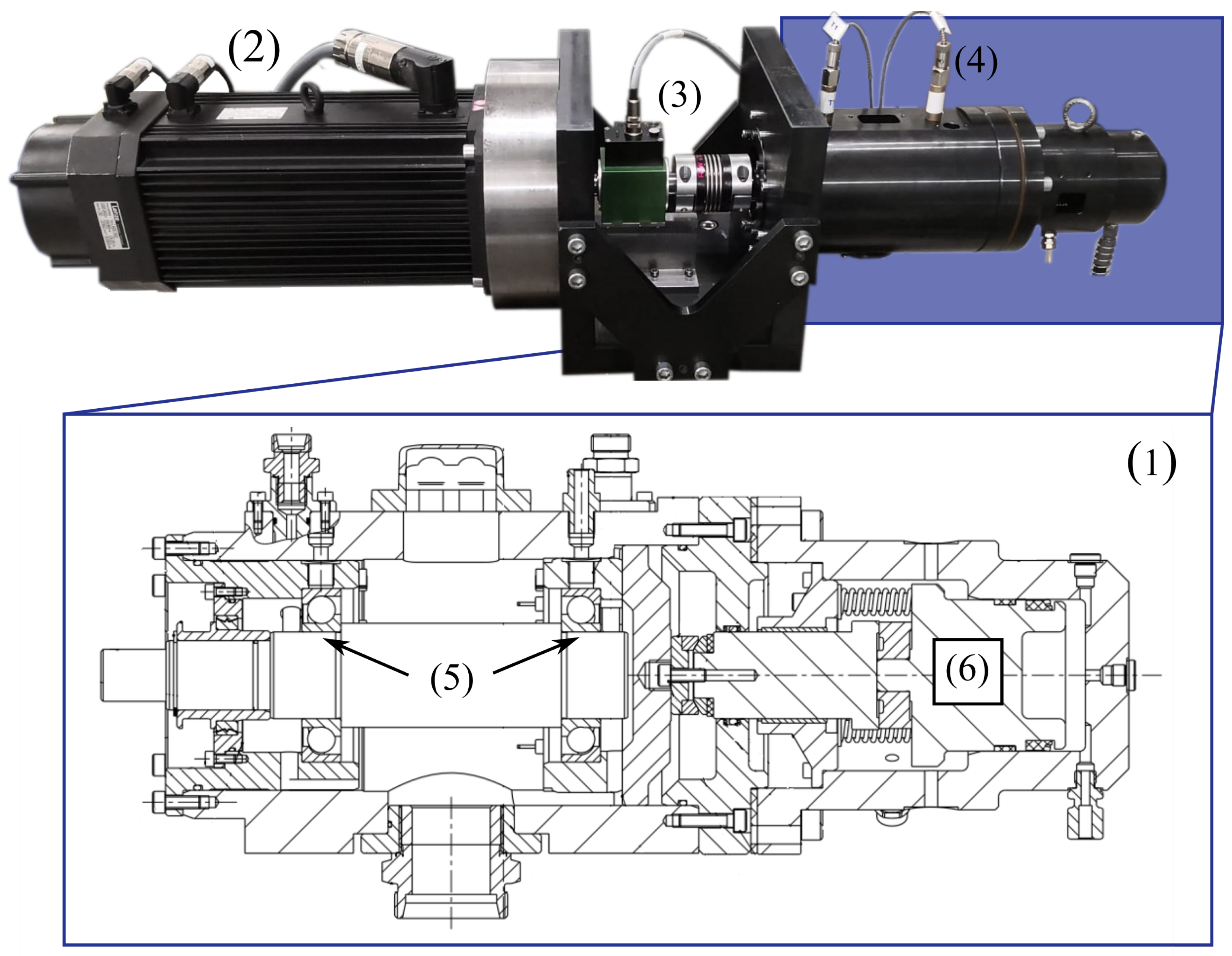

2.1. Experimental Setup

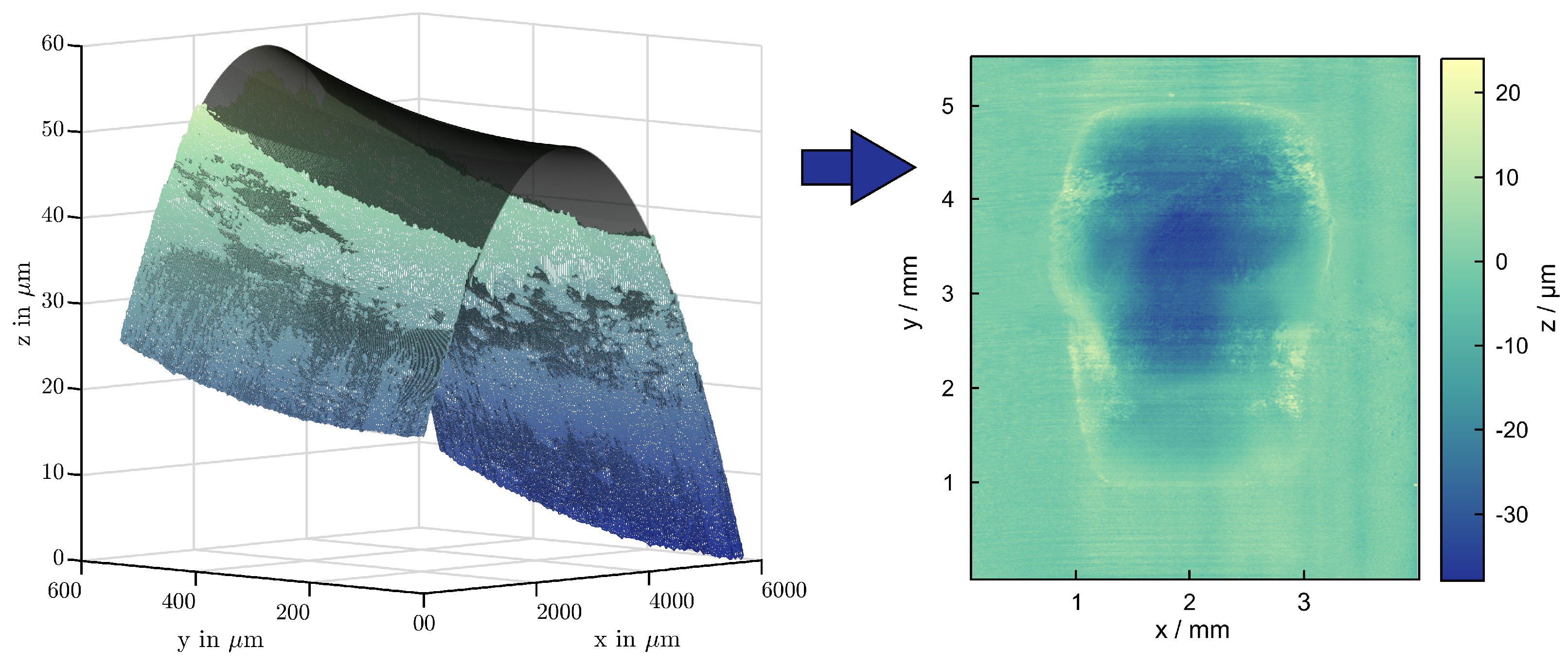

2.2. Methods of Analysis

2.3. Experimental Conditions

2.3.1. Experimental Conditions 7208 bearings

2.3.2. Experimental Conditions on 7220 Bearings

3. Results

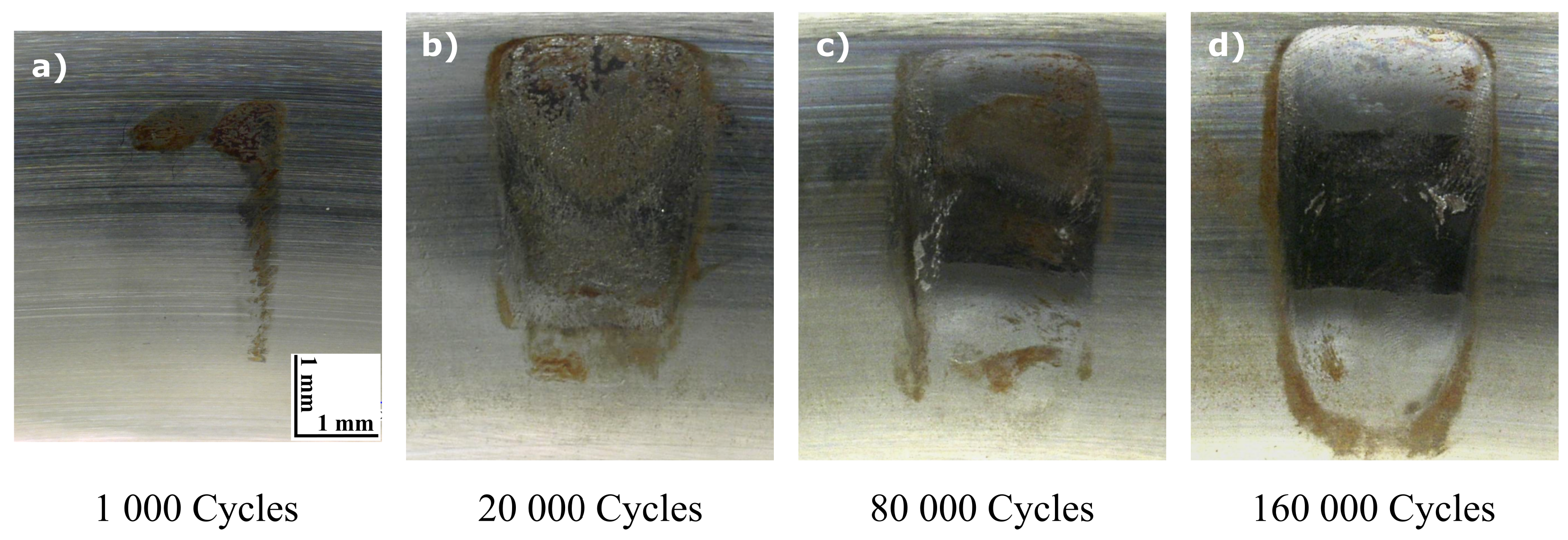

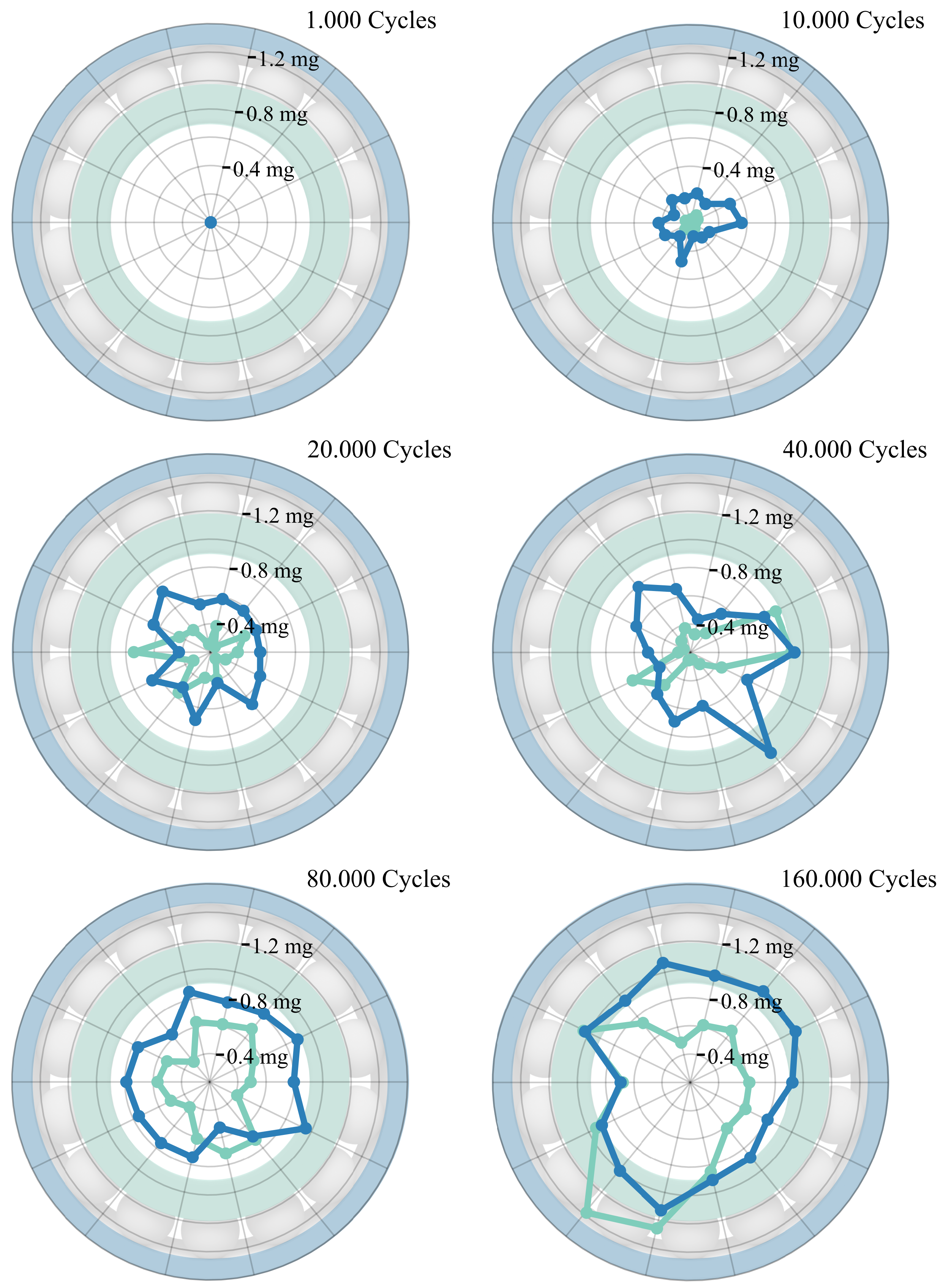

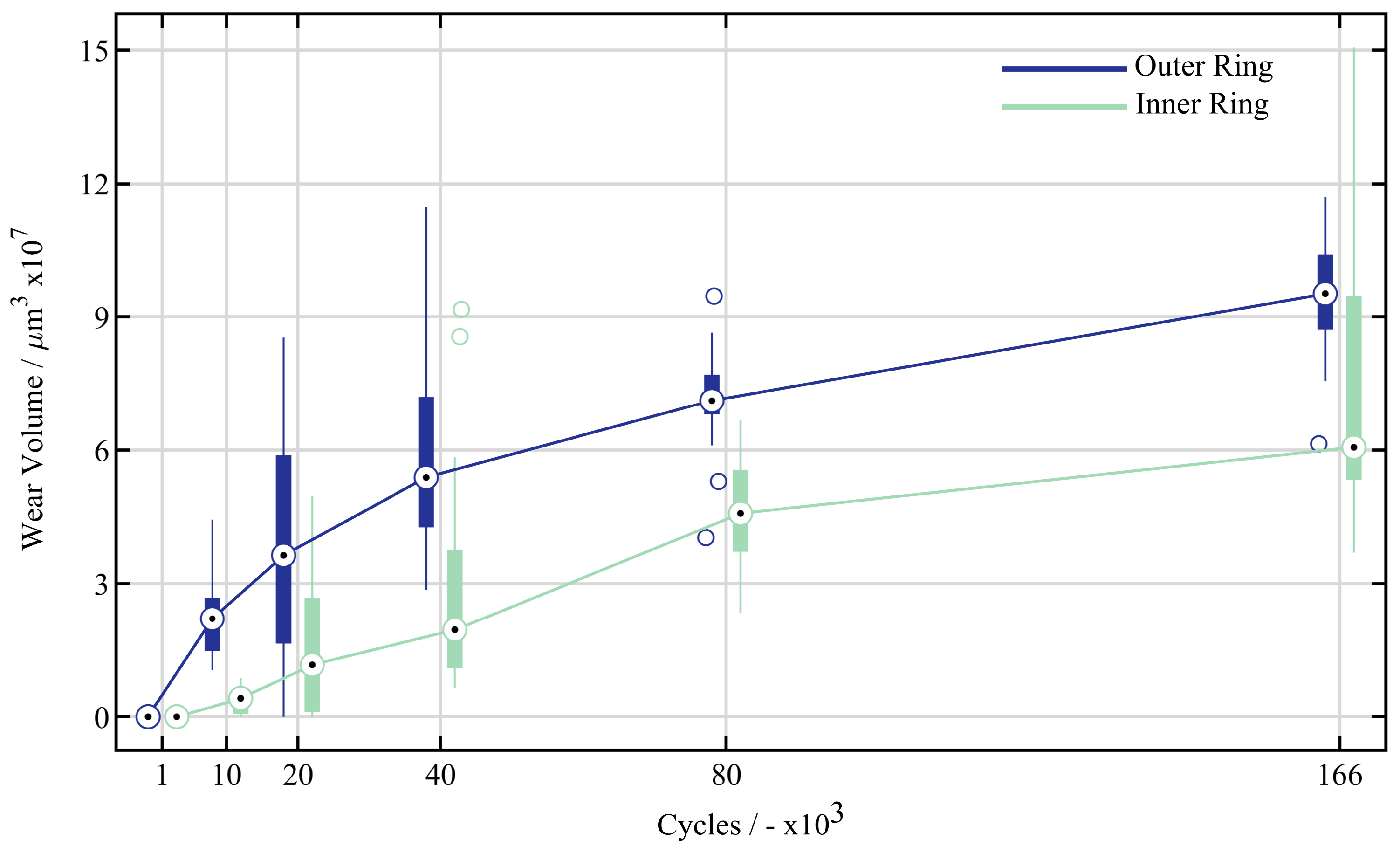

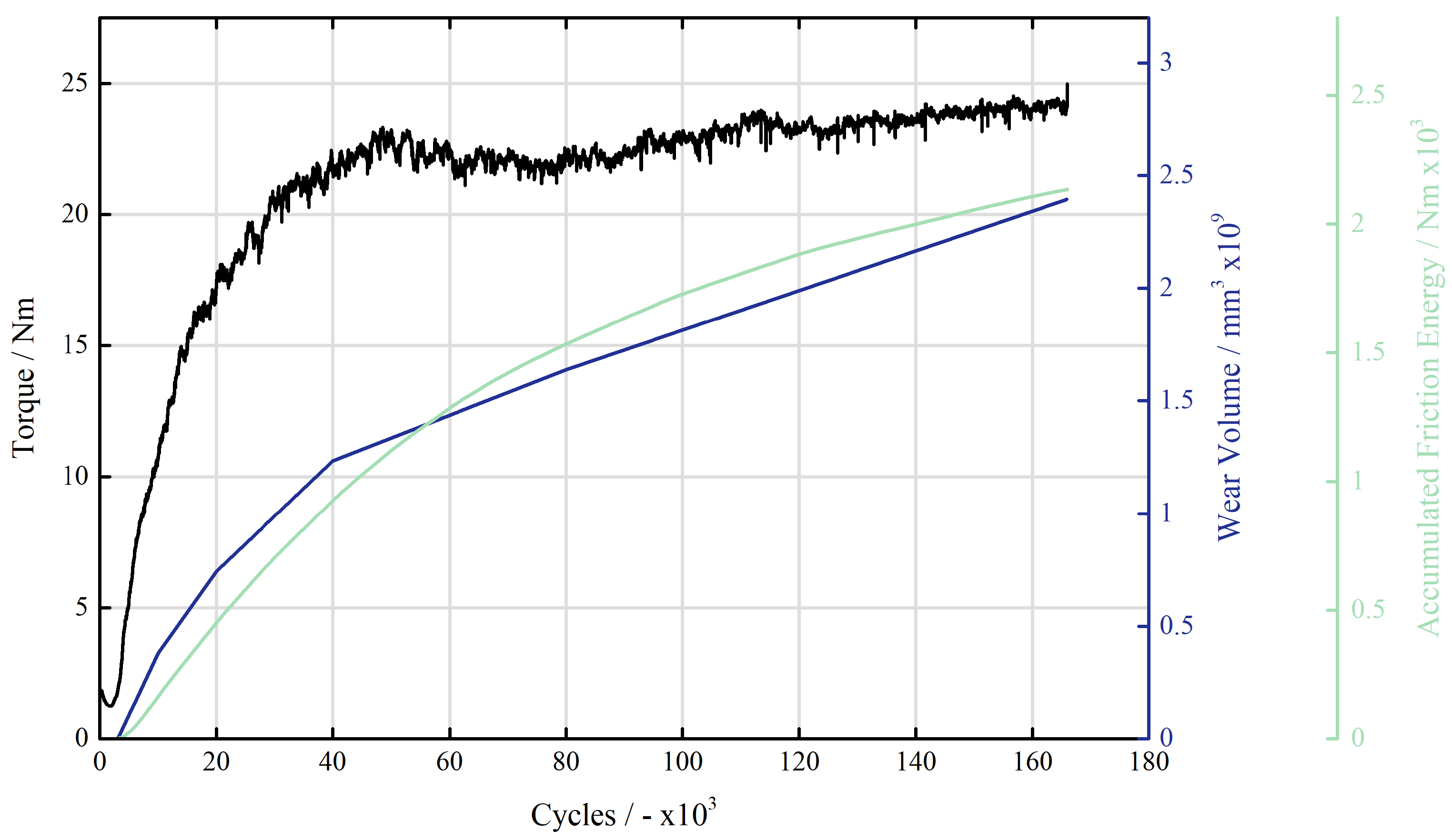

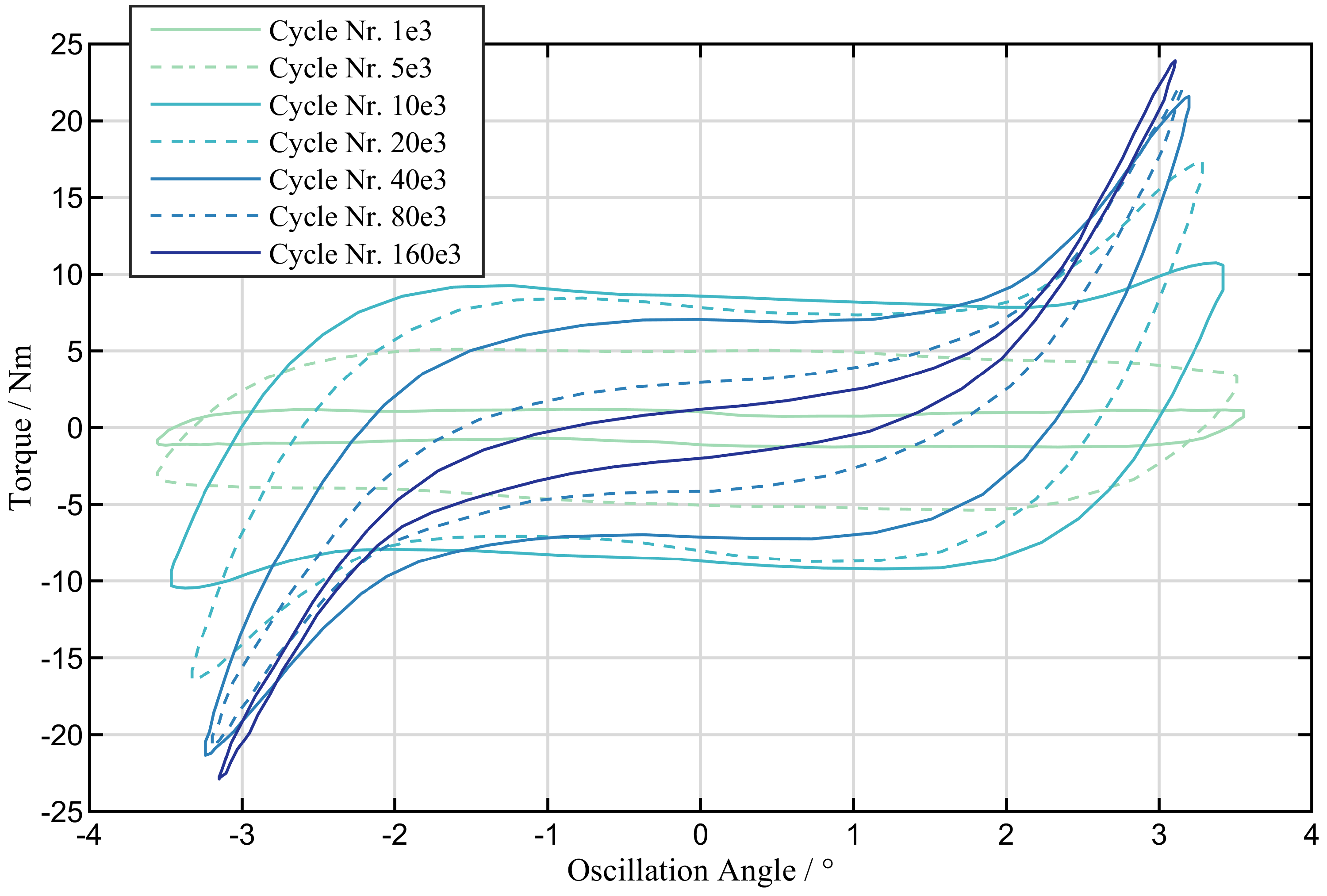

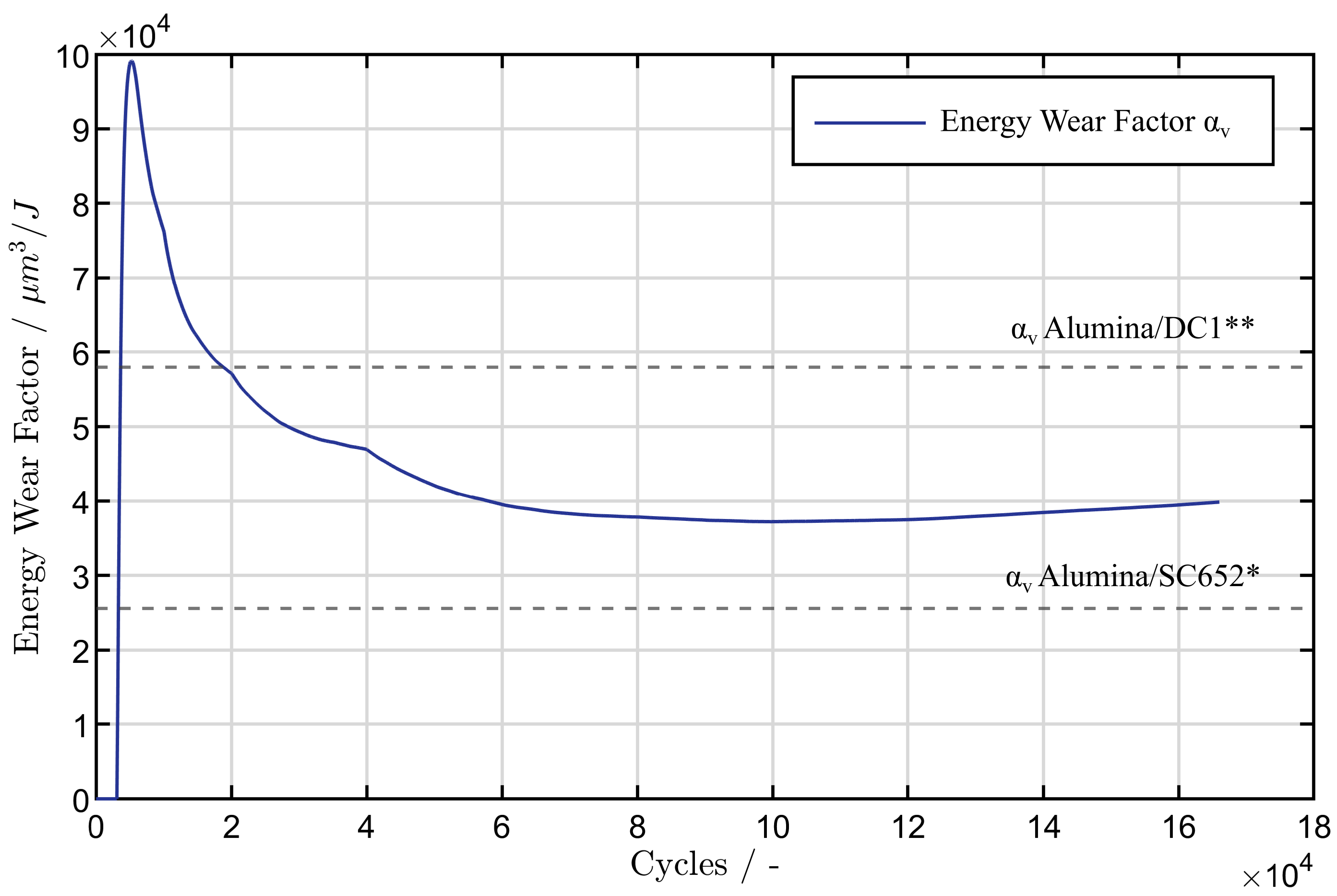

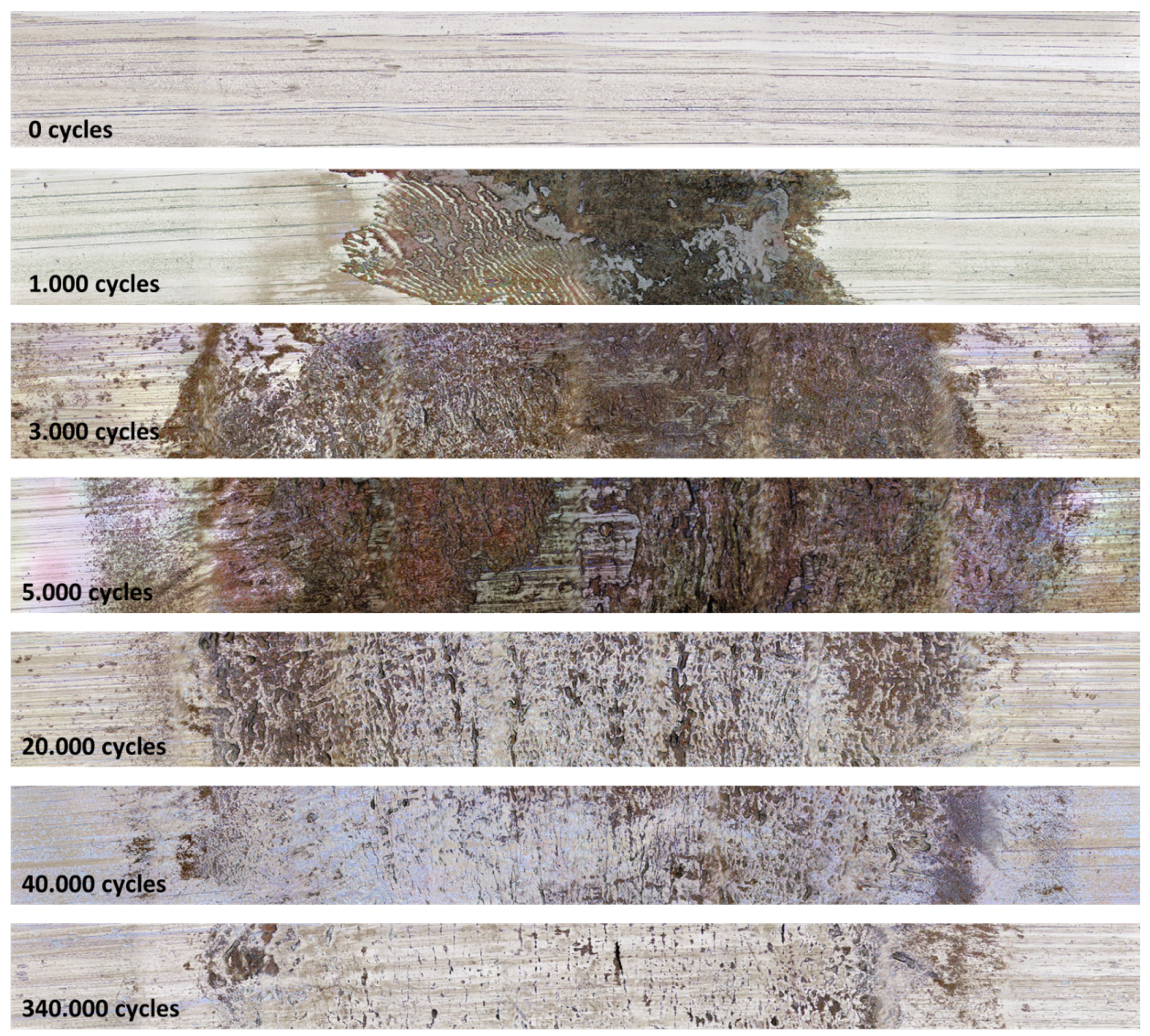

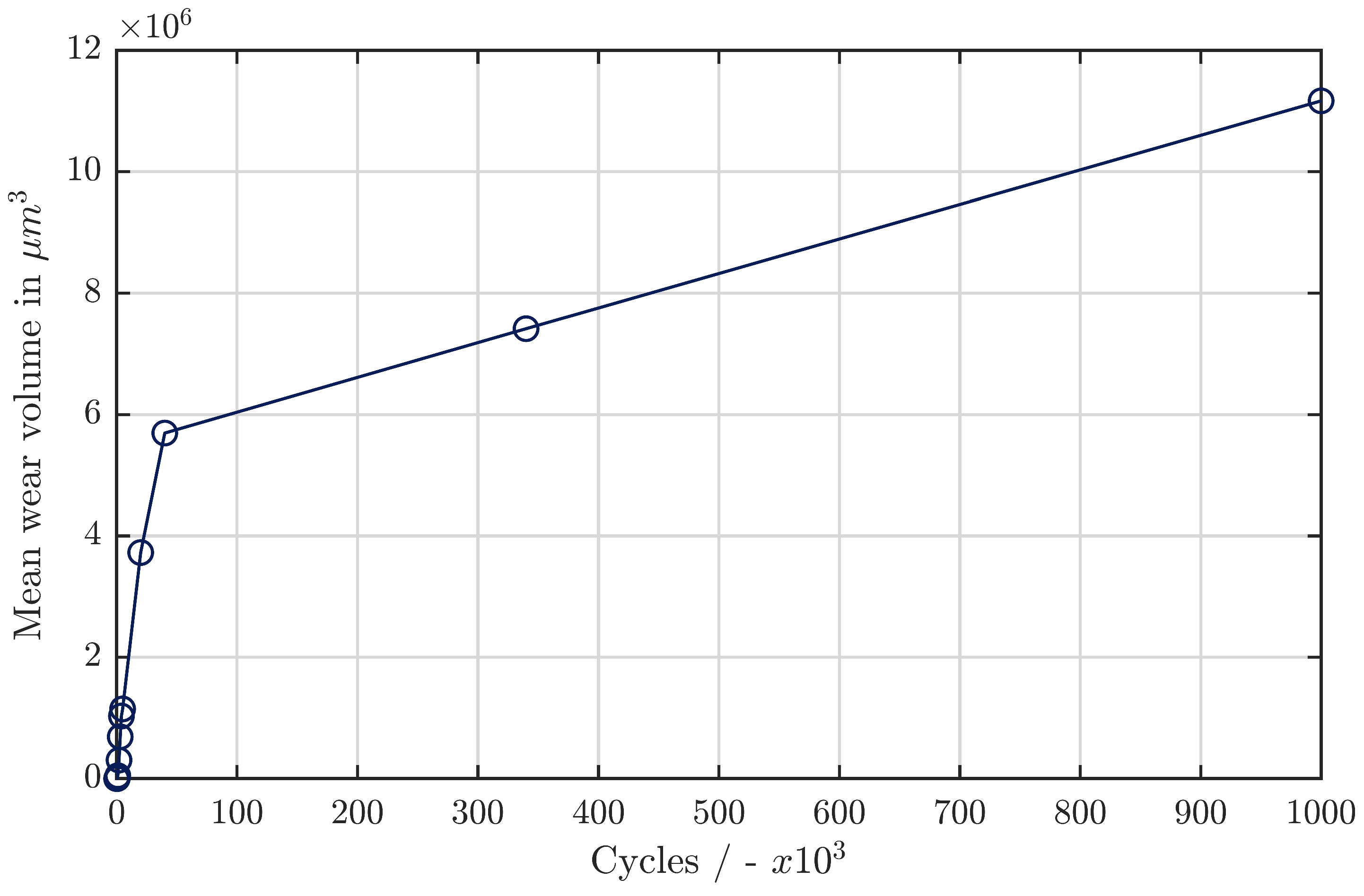

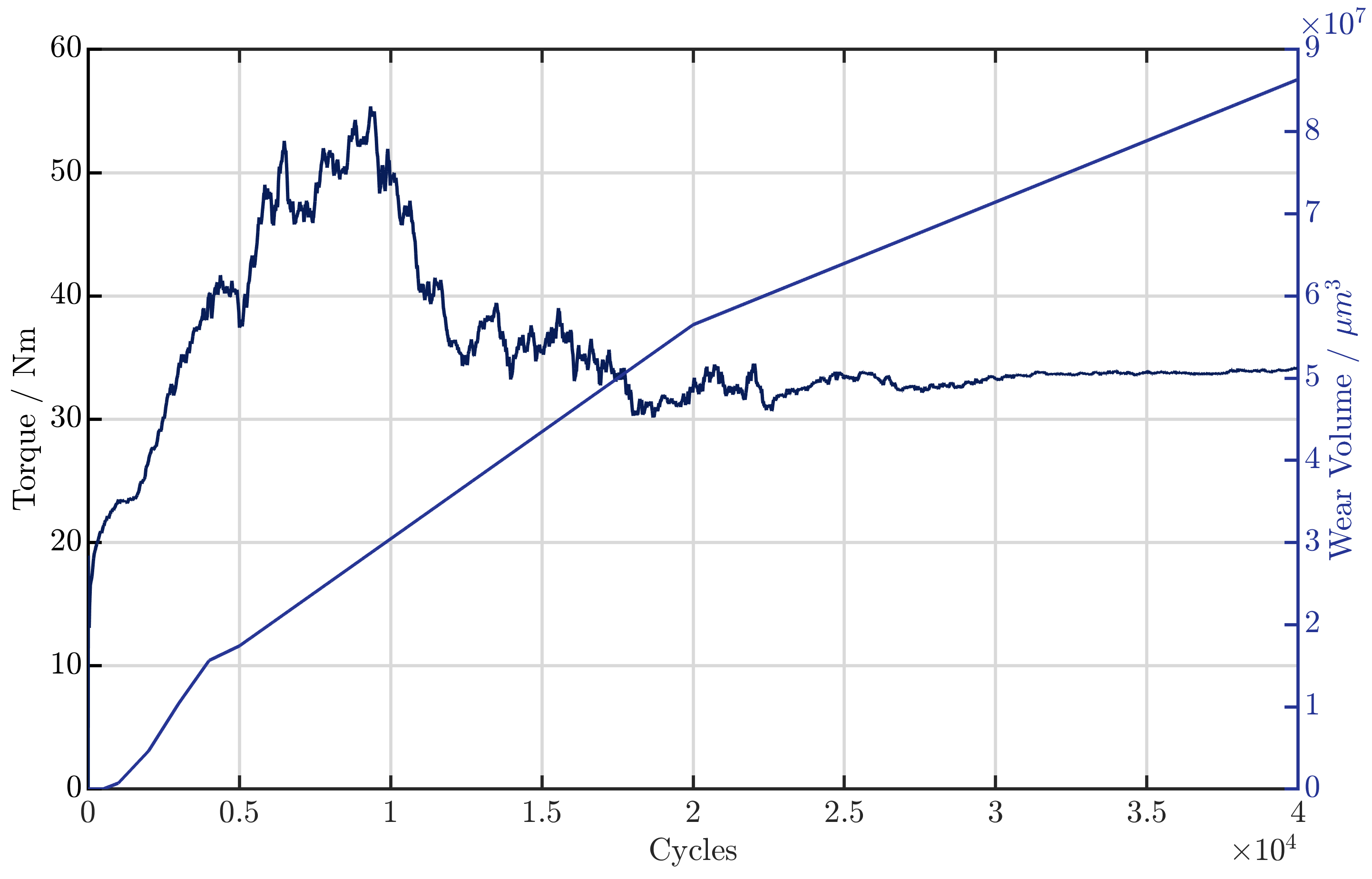

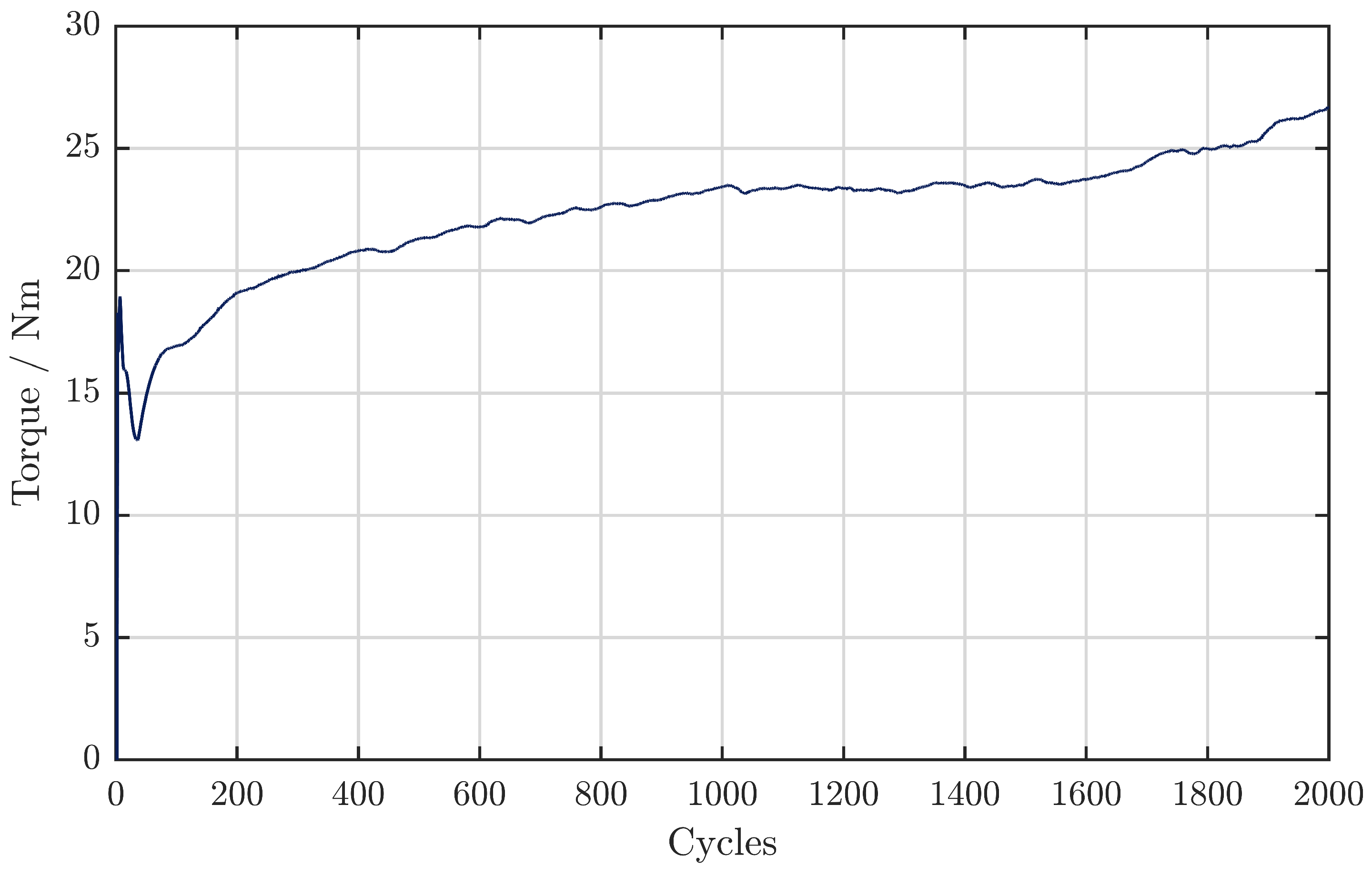

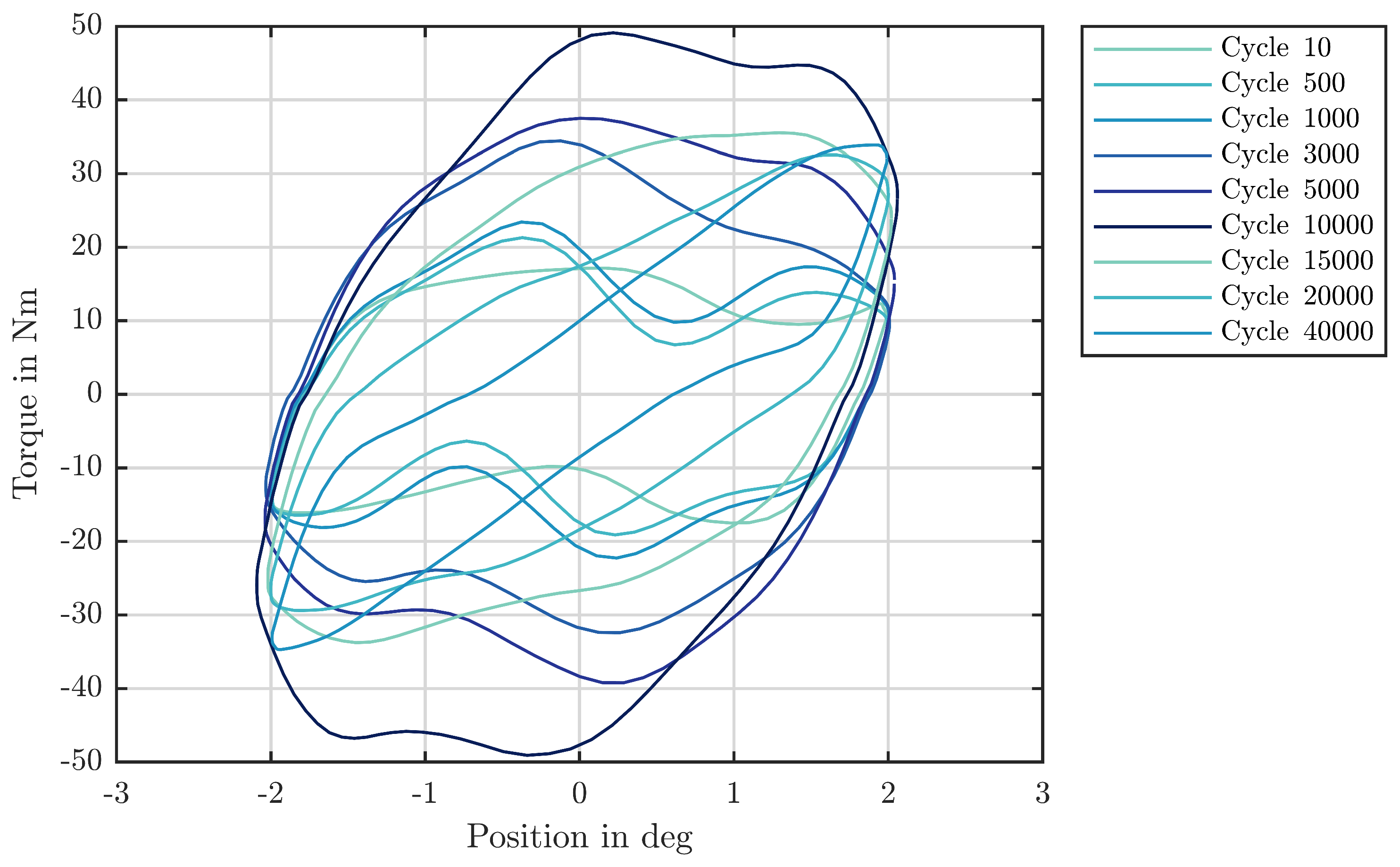

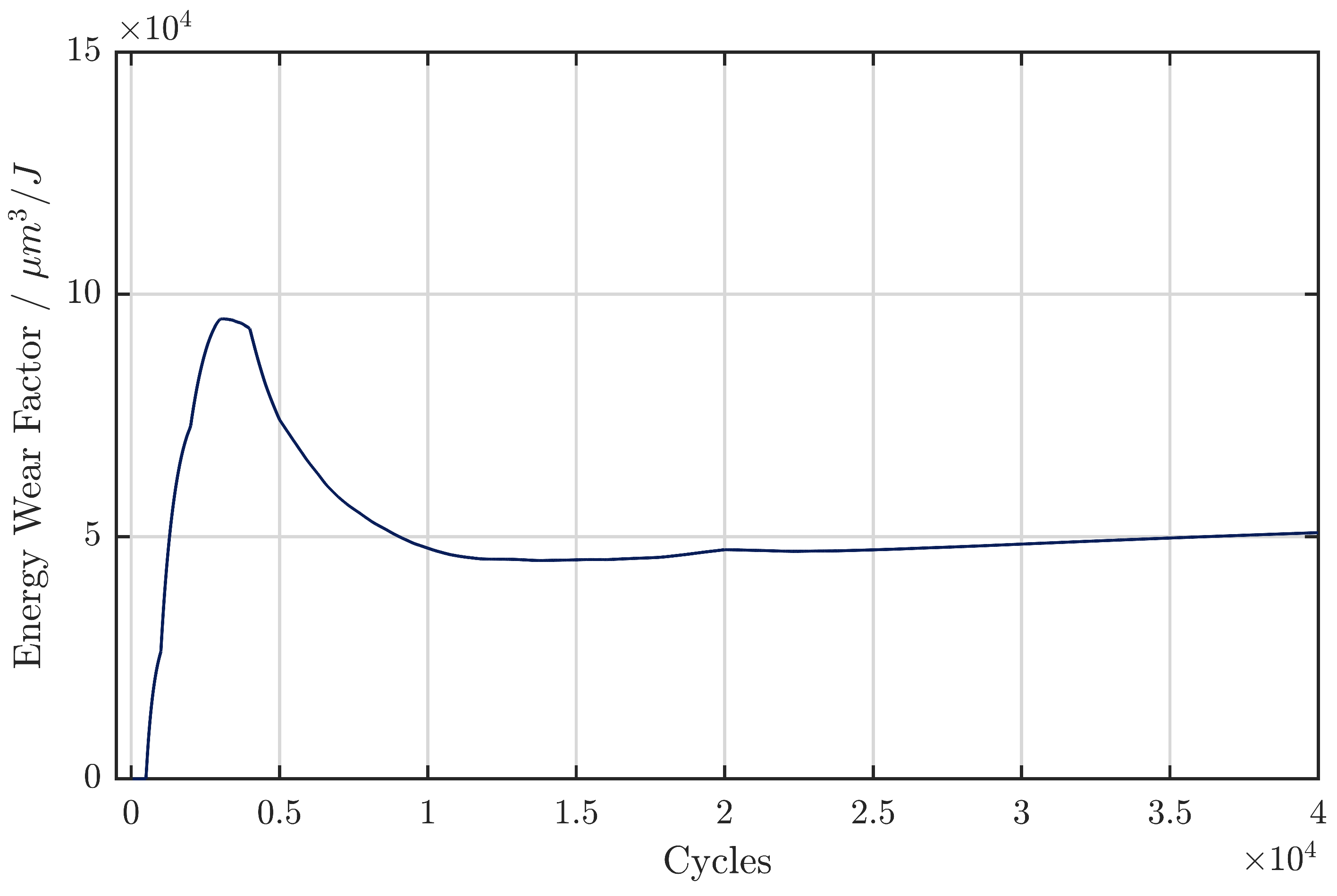

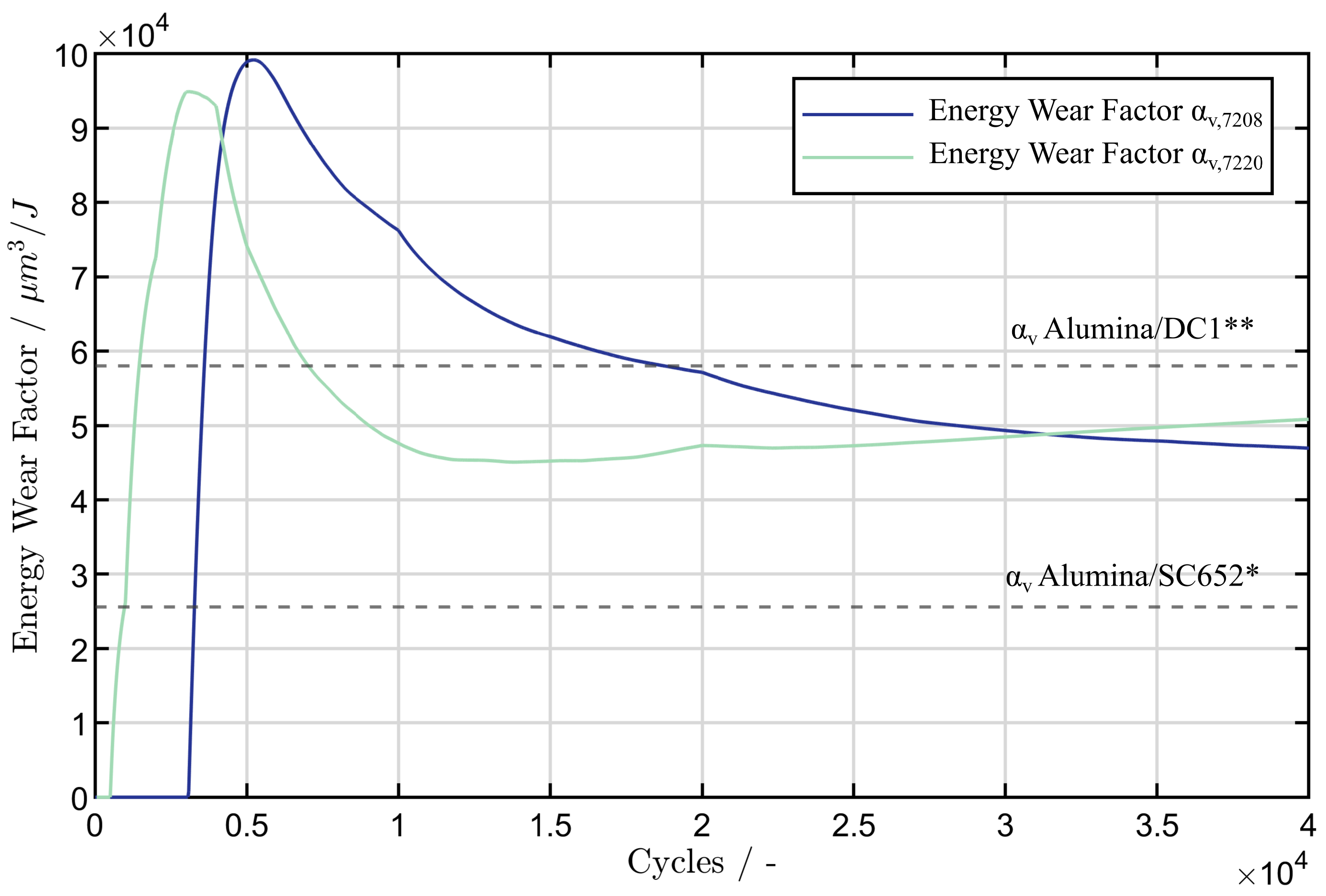

3.1. Wear Development 7208

3.2. Wear Development 7220

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACBB | Angular Contact Ball Bearing |

| HSS | High Speed Steel |

| IPC | Individual Pitch Control |

| CPC | Collective Pitch Control |

| f | Oscillation Frequency |

| Oscillation Angle | |

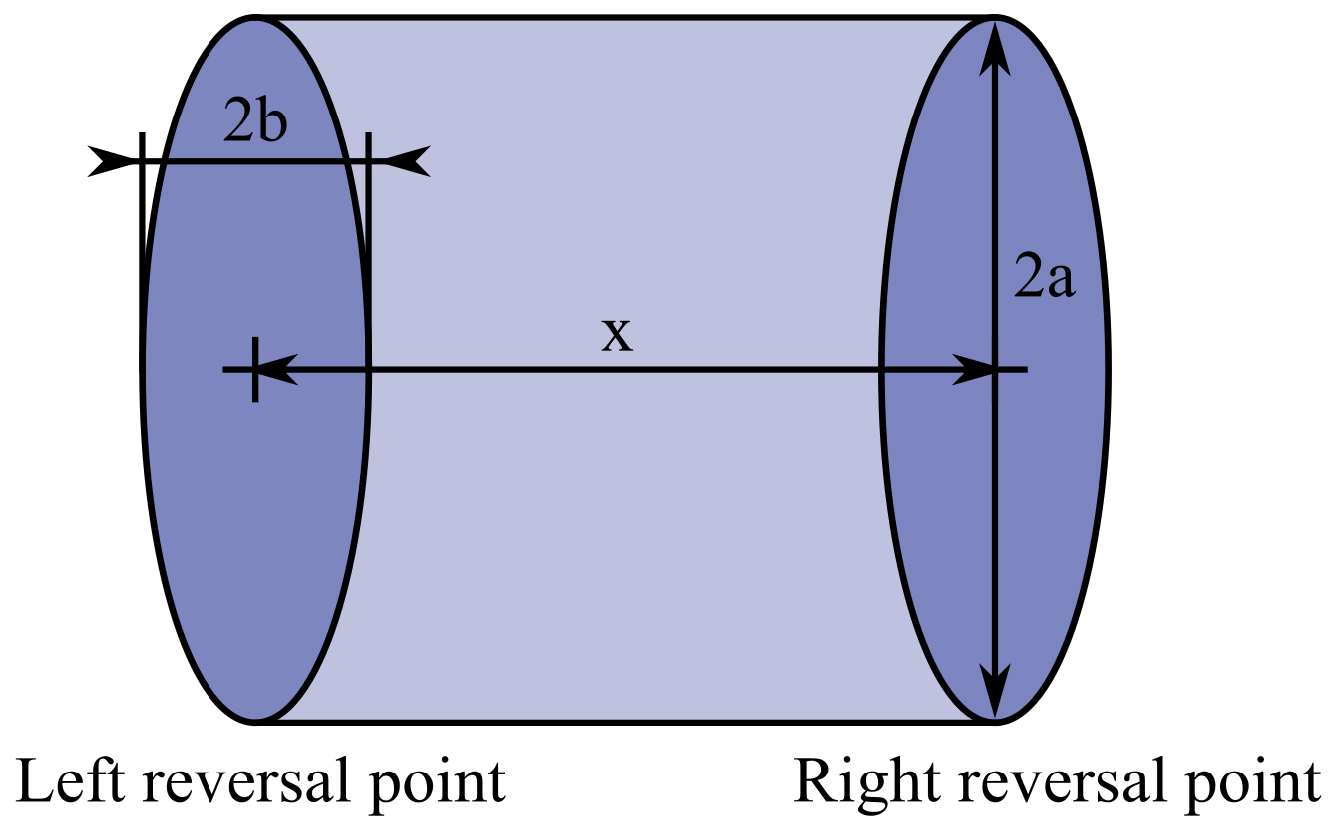

| Amplitude ratio. Ratio of moved distance x | |

| to double half-width of the contact ellipse b | |

| Maximum Contact Pressure | |

| Outer Diameter | |

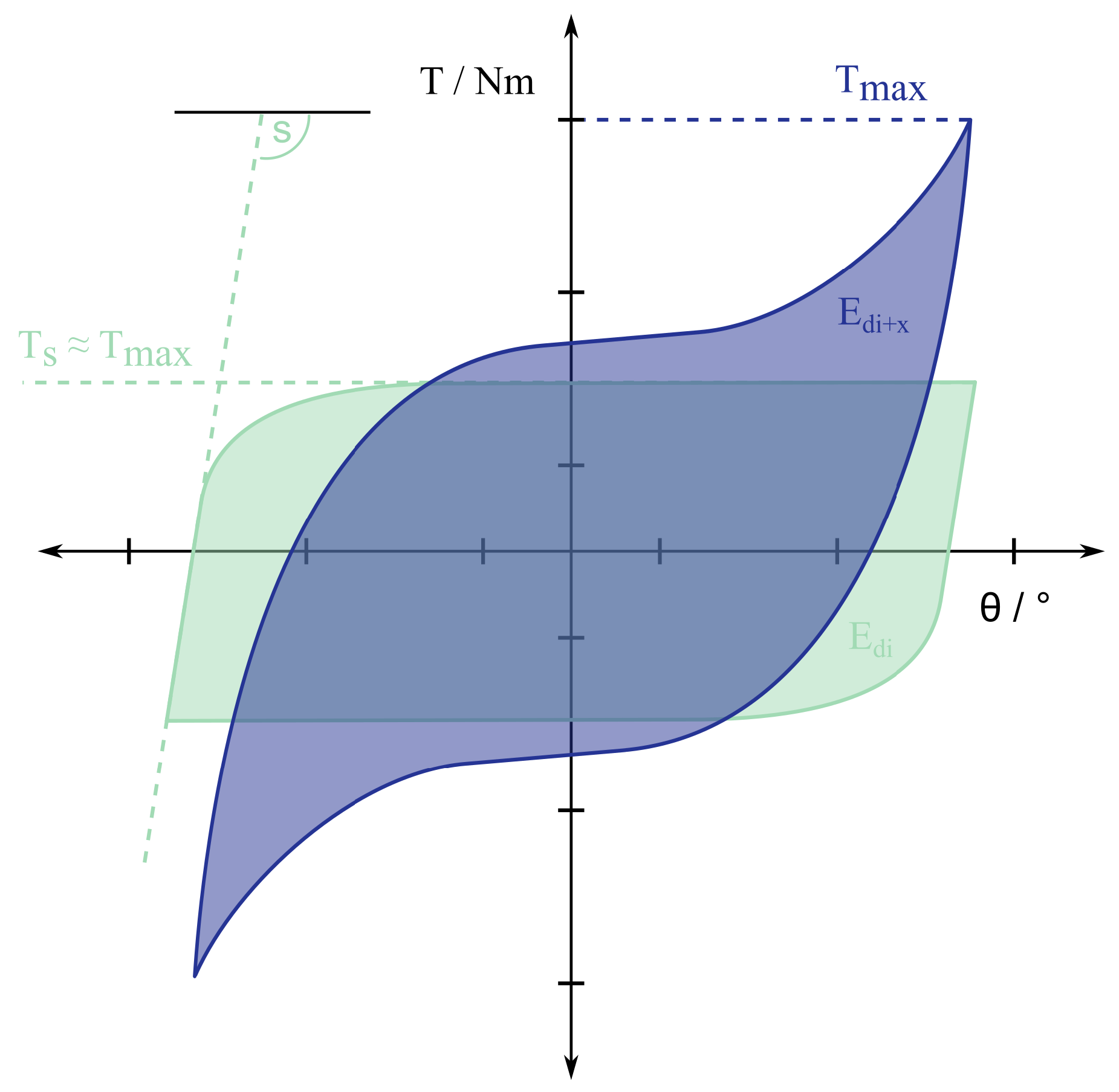

| Steady State Torque | |

| Maximum Torque | |

| Dissipated Friction Energy | |

| Energy Wear Factor |

References

- Burton, T. Wind Energy Handbook,2nd ed., 2011.

- Bossanyi, E.A. Individual blade pitch control for load reduction. Wind Energy: An International Journal for Progress and Applications in Wind Power Conversion Technology 2003, 6, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlas T.K., v. K.G. Review of state of the art in smart rotor control research for wind turbines. Progress in Aerospace Sciences 2010, 46, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stammler, M.; Thomas, P.; Reuter, A.; Schwack, F.; Poll, G. Effect of load reduction mechanisms on loads and blade bearing movements of wind turbines. Wind Energy 2020, 23, 274–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnke, K.; Schleich, F. Exploring Limiting Factors of Wear in Pitch Bearings of Wind Turbines with Real Scale Tests. Wind Energy Science Discussions 2022, 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandel, S.; Bader, N.; Schwack, F.; Glodowski, J.; Lehnhardt, B.; Poll, G. Starvation and relubrication mechanisms in grease lubricated oscillating bearings. Tribology International 2022, 165, 107276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwack, F.; Halmos, F.; Stammler, M.; Poll, G.; Glavatskih, S. Wear in wind turbine pitch bearings—A comparative design study. Wind Energy 2022, 25, 700–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almen, J.O. Lubricants and False Brinelling of Ball and Roller Bearing. Journal of Mechanical Engineering 1937, 59, 415–422. [Google Scholar]

- Vingsbo, O.; Söderberg, S. On Fretting Maps. Wear 1988, 1988, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebe, M.; Molter, J.; Schwack, F.; Poll, G. Damage mechanisms in pivoting rolling bearings and their differentiation and simulation. Bearing World Journal 2018, 3, 72–85. [Google Scholar]

- Grebe, M. False Brinelling - Standstill marks at roller bearings. PhD thesis, Slovak University of Technology, Bratislava, 2012.

- Schwack, F. Untersuchungen zum Betriebsverhalten oszillierender Wälzlager am Beispiel von Rotorblattlagern in Windenergieanlagen. PhD thesis, Leibniz Universität Hannover, Hannover, 2020.

- Schadow, C. Stillstehende fettgeschmierte Wälzlager unter dynamischer Beanspruchung. PhD thesis, Otto-von-Guericke-Universität, Magdeburg, 2016.

- Kita, T.; Yamamoto, Y. Fretting wear performance of lithium 12-hydroxystearate greases for thrust ball bearing in reciprocation motion. Japanese Journal of Tribology 1997, 42, 782–783. [Google Scholar]

- Shima, M.; Jibiki, T. Fretting wear. Journal of Japanese Society of Tribologists 2008, 53, 462–468. [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama, T.; Saitou, T.; Yokouchi, A. Differences in Mechanisms for Fretting Wear Reduction between Oil and Grease Lubrication. Tribology Transactions 2016, 60, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saatchi, A. The Effect of Grease Composition on Fretting Wear. PhD thesis, University of Akron, 2019.

- Wandel, S.; Bader, N.; Glodowski, J.; Lehnhardt, B.; Leckner, J.; Schwack, F.; Poll, G. Starvation and Re-lubrication in Oscillating Bearings: Influence of Grease Parameters. Tribology Letters 2022, 70, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society for Testing and Materials. ASTM D4170 : 2016 - Standard Test Method for Fretting Wear Protection by Lubricating Greases, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Francaise, N. NFT 60-199 - Aptitude à résister au faux effet Brinell, 1995.

- Stammler, M.; Poll, G.; Reuter, A. The influence of oscillation sequences on rolling bearing wear. Bearing World Journal 2019, 4, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Fouvry, S.; Liskiewicz, T.; Kapsa, P.; Hannel, S.; Sauger, E. An energy description of wear mechanisms and its applications to oscillating sliding contacts. Wear 2003, 255, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, P. A solid friction model. Technical report, Aerospace Corp El Segundo Ca, 1968.

- Todd, M.; Johnson, K. A model for coulomb torque hysteresis in ball bearings. International journal of mechanical sciences 1987, 29, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, H.; Lugt, P.M. Replenishment of the EHL contacts in a grease lubricated ball bearing. Tribology international 2020, 146, 106064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Grease 1 | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Thickener Type | Lithium | - |

| Base Oil Type | synthetic (PAO) | - |

| Base Oil Viscosity | 50 | cSt at 40 C |

| Oil Separation Rate (IP 121) | 4 | % |

| Dropping Point | >180 | C |

| Additives | fully additivated + solid lubricants | - |

| Parameter | 7208 | 7220 | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Axial Load | 12.4 | 90 | kN |

| Oscillation Frequency f | 5 | 0.5 | Hz |

| Oscillation Angle | 7 | 4 | |

| Amplitude Ratio x/2b | 4 | 2.6 | - |

| Cycles | 1, 5, 10, 20, 40, 80, 160 | 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 20, 40, 340, 1000 | x10 |

| Young’s modulus, E (GPa) | Poisson coefficient, | Hardness, H (HV) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100Cr6 | 210 | 0.3 | 800 |

| Alumina (counterbody) | 370 | 0.27 | 2300 |

| HSS (SC652) | 230 | 0.28 | 800 |

| DC1 (sintered steel) | 200 | 0.3 | 370 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).